Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

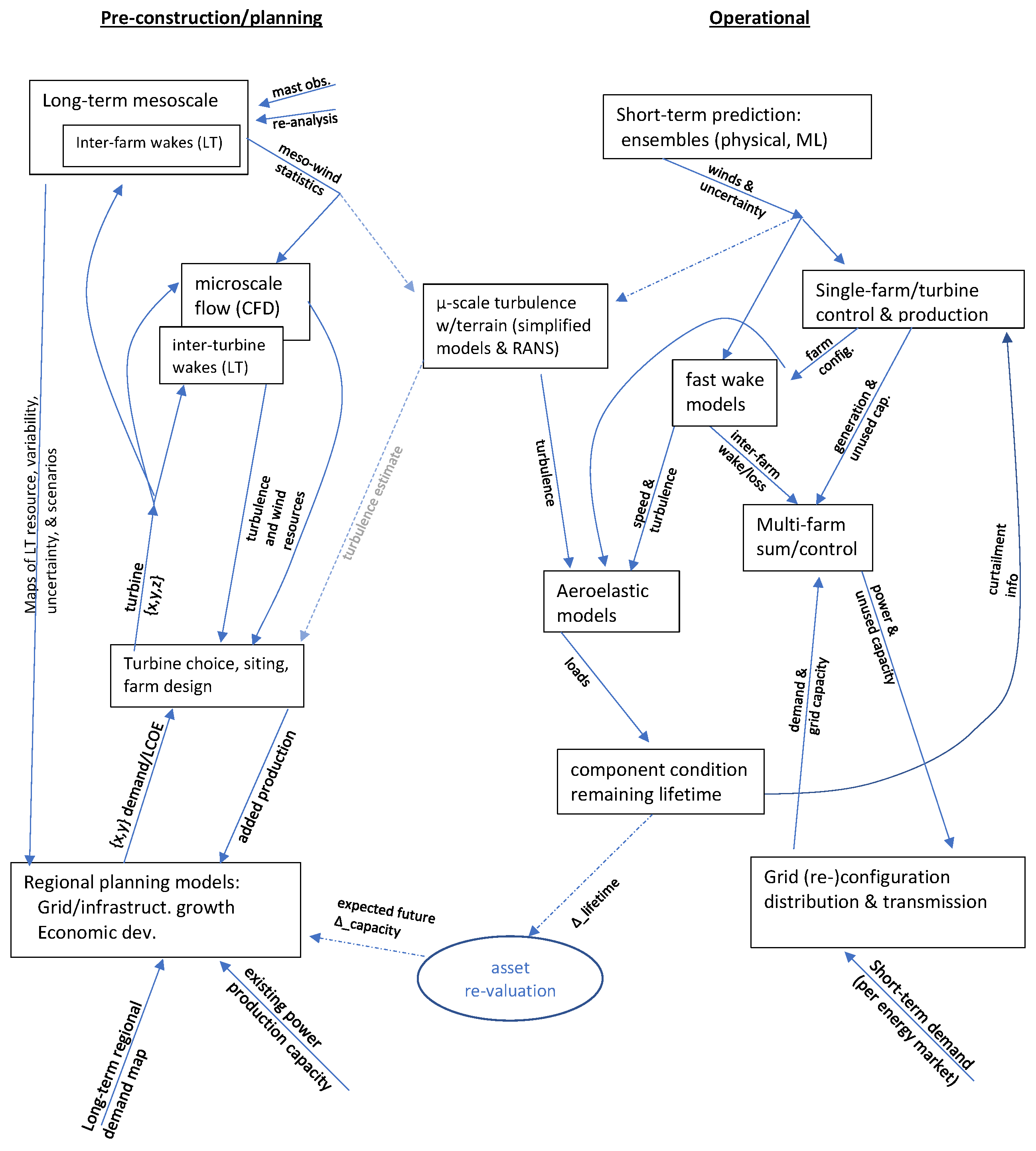

1.1. An Exceptional Multi-Disciplinary Problem

2. Some Wind Energy Meteorology

2.1. Describing the Parameter Space for Wind

- ABL Rossby number [20];

2.2. First Applications of Meteorology in Wind Energy

2.3. Meteorology Beyond the Surface-Layer

2.4. More Advanced Modelling...

2.4.1. RANS Modelling

2.4.2. Mesoscale Modelling

3. Appropriate Statistical Characterization, from Theory to Practice

3.1. Rational Averaging Implicit in Classic WRA

3.2. Refined Modelling and Consequent Sampling Issues

3.3. Averaging Issues Arising with Timeseries Use or Comparisons

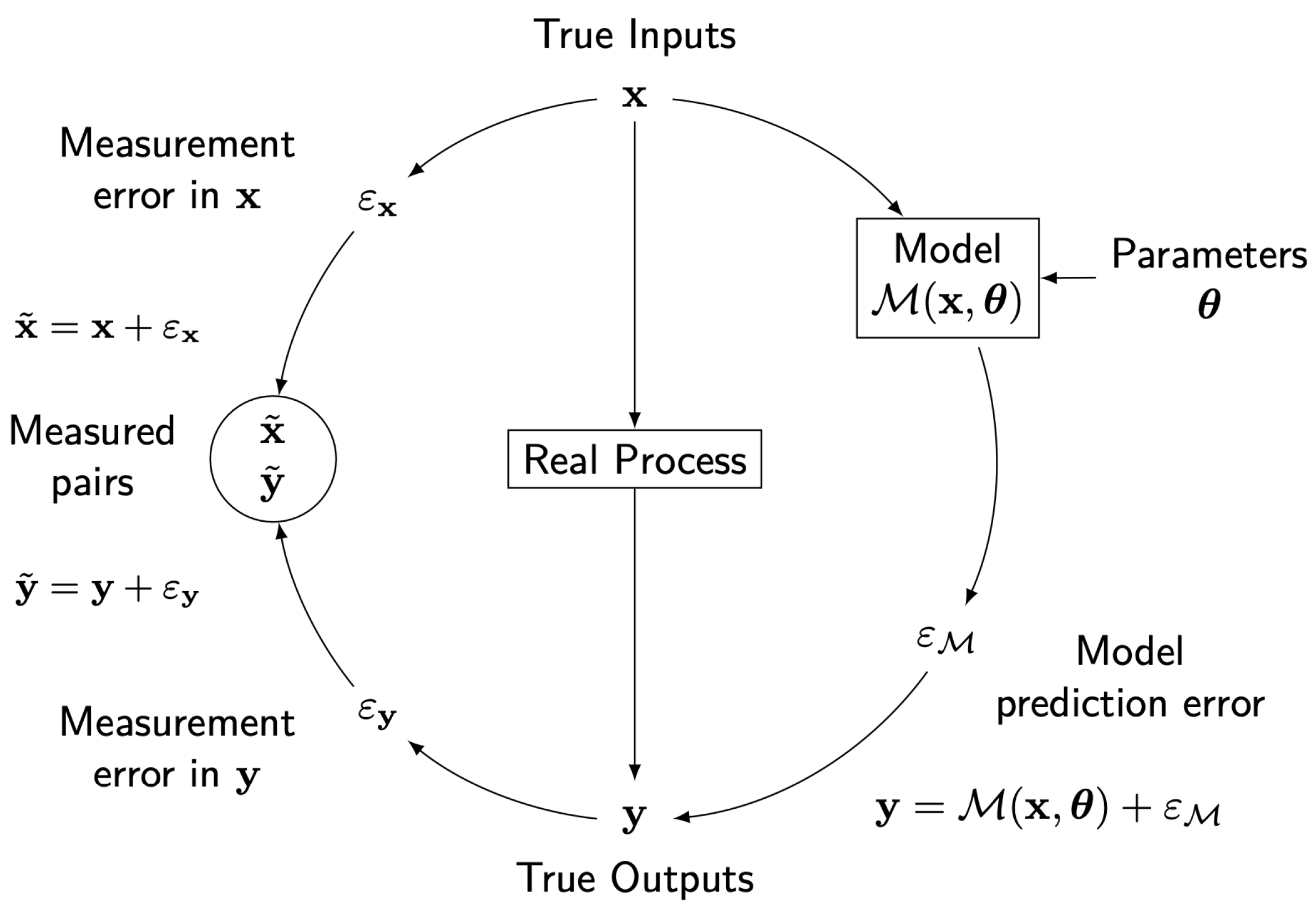

4. Uncertainty Quantification

4.1. Uncertainty in the Complex ABL System

5. Industrial Application

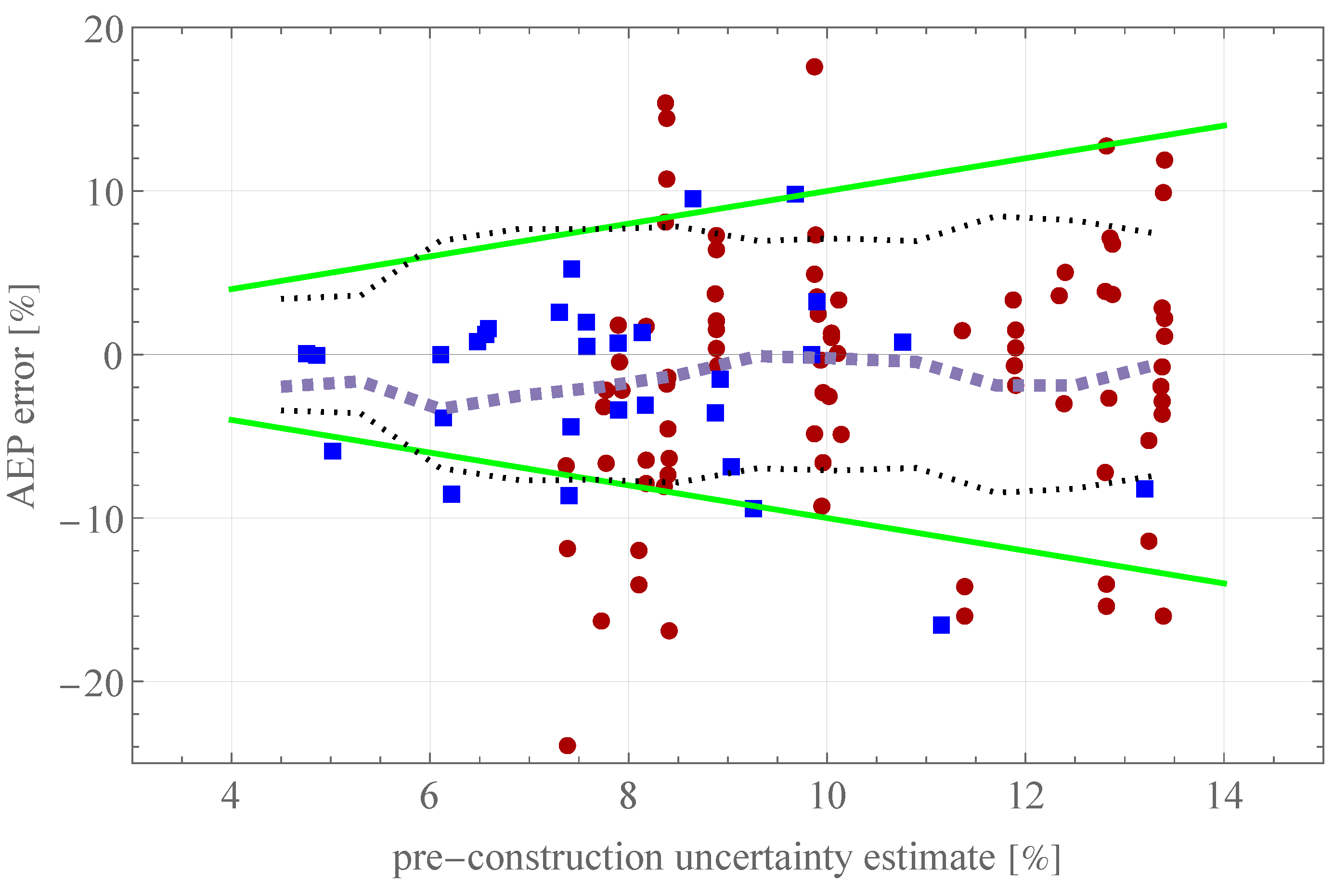

5.1. Wind Resources

5.1.1. Wind Uncertainty Components

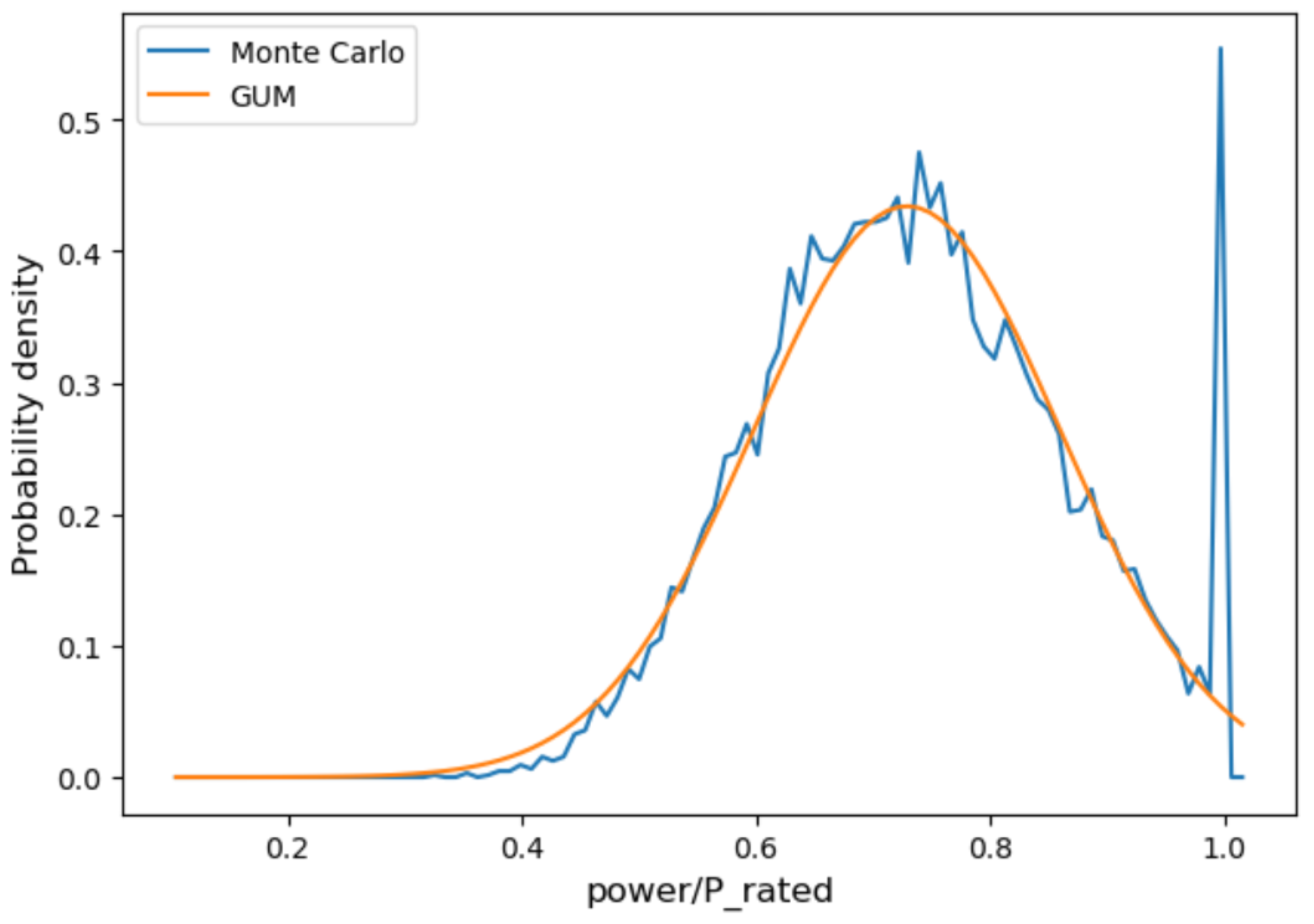

5.1.2. Combination of Uncertainty Componennts

5.1.3. From Wind to Energy

5.2. Forecasting

5.3. Wind Atlases and Assessments Without Measurements

5.4. Siting, Design, and Standards

5.5. Distinction from Risk

6. Summary

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABL | Atmospheric Boundary Layer |

| ASL | Atmospheric Surface Layer |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| EWA | European Wind Atlas (method) |

| EYA | Energy Yield Assessment |

| GDL | Geostrophic Drag Law |

| GWA | Global Wind Atlas |

| HE | Horizontal Extrapolation |

| LES | Large-Eddy Simulation |

| LT | Long-Term |

| LTC | Long-Term Correction |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NWP | Numerical Weather Prediction |

| Probability Density Function | |

| PIRT | Phenomenon Identification and Ranking Table |

| RANS | Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes |

| UQ | Uncertainty Quantification |

| VE | Vertical Extrapolation |

| V&V | Validation and Verification |

| WRA | Wind Resource Assessment |

| WRF | Weather Research and Forecasting model |

References

- Emeis, S. Wind energy meteorology—Atmospheric Physics for wind power generation; Springer: Dordrecht, 2013; p. 150.

- Landberg, L. Meteorology for wind energy : an introduction; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom, 2016; p. 210.

- Watson, S. Handbook of Wind Resource Assessment; Wiley, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wyngaard, J.C. Turbulence in the Atmosphere; Cambridge University Press, 2010; p. 393.

- Zilitinkevich, S.S.; Tyuryakov, S.A.; Troitskaya, Y.I.; Mareev, E.A. Theoretical models of the height of the atmospheric boundary layer and turbulent entrainment at its upper boundary. Izvestiya, Atmospheric and Oceanic Physics 2012, 48, 133–142. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, N.; Kelly, M.; Vignaroli, A.; Berg, J. From wind to loads: wind turbine site-specific load estimation using databases with high-fidelity load simulations. Wind Energy Science Discussions 2018, 2018, in review. [CrossRef]

- Bohren, C.F.; Albrecht, B.A. Atmospheric Thermodynamics; Oxford University Press: New York, 1998; p. 402.

- Zilitinkevich, S.; Baklanov, A. Calculation Of The Height Of The Stable Boundary Layer In Practical Applications. Boundary-Layer Meteorology 2002, 105, 389–409. [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.H. Dimensional Analysis and the Buckingham Pi Theorem. American Journal of Physics 1972, 40, 1815–1822. [CrossRef]

- Barenblatt, G.I. Scaling, Self-similarity, and Intermediate Asymptotics; Cambridge University Press, 1996. [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer, M.W.; Doman, D.B.; Merrick, J.D. Multi-scale physics-informed machine learning using the Buckingham Pi theorem. Journal of Computational Physics 2023, 474, 111810. [CrossRef]

- Sathe, A.S.; Giometto, M.G. Impact of the numerical domain on turbulent flow statistics: scalings and considerations for canopy flows. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2024, 979. [CrossRef]

- Csanady, G.T. On the “Resistance Law” of a Turbulent Ekman Layer. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 1967, 24, 467–471. [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, F.; Panofsky, H.A. The geostrophic drag coefficient and the `effective’ roughness length. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 1972, 98, 213–220. [CrossRef]

- Troen, I.; Petersen, E.L. European Wind Atlas; Risø National Laboratory: Roskilde, Denmark, 1989; p. 656.

- Rossby, C.G.; Montgomery, R.B. The Layer of Frictional Influence in Wind and Ocean Currents. Pap. Physical Oceanography and Meteorology 1935, 3, 1–101.

- Obukhov, A.M. Turbulence in an atmosphere with a non-uniform temperature. Boundary-Layer Meteorology 1971, 2, 7–29. [CrossRef]

- Foken, T. 50 Years of the Monin–Obukhov Similarity Theory. Boundary-Layer Meteorology 2006, 119, 431–447. [CrossRef]

- Yano, J.; Wacławczyk, M. Nondimensionalization of the Atmospheric Boundary-Layer System: Obukhov Length and Monin–Obukhov Similarity Theory. Boundary-Layer Meteorology 2022, 182, 417–439. [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, M.P.; Kelly, M.; Floors, R.; Peña, A. Rossby number similarity of an atmospheric RANS model using limited-length-scale turbulence closures extended to unstable stratification. Wind Energy Science 2020, 5, 355–374. [CrossRef]

- Kazanskii, A.; Monin, A. Dynamic interaction between atmosphere and surface of earth. Akademiya Nauk SSSR Izvestiya Seriya Geofizicheskaya 1961, 24, 786–788.

- Smith, F.B. The relation between Pasquill stability p and Kazanski-Monin stability μ (In neutral and unstable conditions). Atmospheric Environment (1967) 1979, 13, 879–881. [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.P.S. Geostrophic drag and heat transfer relations for the atmospheric boundary layer. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 1975, 101, 147–161.

- Shen, Z.; Liu, L.; Lu, X.; Stevens, R.J.A.M. The global properties of nocturnal stable atmospheric boundary layers. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2024, 999. [CrossRef]

- Zilitinkevich, S.; Johansson, P.E.; Mironov, D.V.; Baklanov, A. A similarity-theory model for wind profile and resistance law in stably stratified planetary boundary layers. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 1998, 74-76, 209–218. [CrossRef]

- Zilitinkevich, S.S.; Esau, I.N. On integral measures of the neutral barotrophic planetary boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteor. 2002, 104, 371–379.

- Narasimhan, G.; Gayme, D.F.; Meneveau, C. Analytical Model Coupling Ekman and Surface Layer Structure in Atmospheric Boundary Layer Flows. Boundary-Layer Meteorology 2024, 190. [CrossRef]

- Goger, B.; Rotach, M.W.; Gohm, A.; Stiperski, I.; Fuhrer, O.; de Morsier, G. A New Horizontal Length Scale for a Three-Dimensional Turbulence Parameterization in Mesoscale Atmospheric Modeling over Highly Complex Terrain. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 2019, 58, 2087–2102. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.; Cavar, D. Effective roughness and `displaced’ mean flow over complex terrain. Boundary-Layer Meteor. 2023, 186, 93–123. [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.P.S.; Wyngaard, J.C. Effect of Baroclinicity on Wind Profiles and the Geostrophic Drag Law for the Convective Planetary Boundary Layer. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 1975, 32, 767–778. [CrossRef]

- Floors, R.R.; Kelly, M.; Troen, I.; Pena Diaz, A.; Gryning, S.E. Wind profile modelling using WAsP and “tall” wind measurements. In Proceedings of the Abstracts of the 15th EMS Annual Meeting; 12th European Conference on Applications of Meteorology (ECAM) 2015. European Meteorological Society, 2015.

- Larsen, G.C.; Madsen, H.A.; Thomsen, K.; Larsen, T.J. Wake meandering: a pragmatic approach. Wind Energy 2008, 11, 377–395. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, G.C.; Machefaux, E.; Chougule, A. Wake meandering under non-neutral atmospheric stability conditions - theory and facts. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2015, 625, 012036. [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, E.L.; Madsen, M.H.A.; Andersen, S.J. Effects of turbulent inflow time scales on wind turbine wake behavior and recovery. Physics of Fluids 2023, 35. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.J.; Sørensen, J.N.; Mikkelsen, R.F. Turbulence and entrainment length scales in large wind farms. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2017, 375, 20160107. [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.H.; Mann, J.; Platis, A.; Bange, J. Turbulence structures and entrainment length scales in large offshore wind farms. Wind Energy Science 2023, 8, 125–139. [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, E.L.; Troldborg, N.; Andersen, S.J. Impact of freestream turbulence integral length scale on wind farm flows and power generation. Renewable Energy 2025, 238, 121804. [CrossRef]

- Strickland, J.M.I.; Gadde, S.N.; Stevens, R.J.A.M. Wind farm blockage in a stable atmospheric boundary layer. Renewable Energy 2022, 197, 50–58. [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M.S.; Lundquist, J.K.; Mirocha, J.D.; Arthur, R.S. Investigating the physical mechanisms that modify wind plant blockage in stable boundary layers. Wind Energy Science 2023, 8, 1049–1069. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liang, X.Z. Observed Diurnal Cycle Climatology of Planetary Boundary Layer Height. Journal of Climate 2010, 23, 5790–5809.

- Regner, P.; Gruber, K.; Wehrle, S.; Schmidt, J. Explaining the decline of US wind output power density. Environmental Research Communications 2023, 5, 075016. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.S.; Hunt, J.C. Turbulent Wind Flow over a Low Hill. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 1975, 101, 929–955.

- Troen, I. A HIGH-RESOLUTION SPECTRAL MODEL FOR FLOW IN COMPLEX TERRAIN. In Proceedings of the Ninth symposium on Turbulence and Diffusion; Jensen, N.O.; Kristensen, L.; Larsen, S., Eds. American Meteorological Society, 1990, pp. 417–420.

- Sempreviva, A.M.; Larsen, S.E.; Mortensen, N.G.; Troen, I. Response of neutral boundary layers to changes in roughness. Boundary-Layer Meteor. 1990, 50, 205–225.

- Kelly, M.; Troen, I. Probabilistic stability and “tall” wind profiles: theory and method for use in wind resource assessment. Wind Energy 2016, 19, 227–241.

- Kelly, M.; Troen, I.; Jørgensen, H.E. Weibull-k revisited: `tall” profiles and height variation of wind statistics. Boundary-Layer Meteor. 2014, 152, 107–124. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.; Larsen, G.; Dimitrov, N.K.; Natarajan, A. Probabilistic Meteorological Characterization for Turbine Loads. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2014, 524, 012076. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.; van der Laan, M.P. From Shear to Veer: Theory, Statistics, and Practical Application. Wind Energy Science 2023, 8, 975–998. [CrossRef]

- Carl, D.M.; Tarbell, T.C.; Panofsky, H.A. Profiles of Wind and Temperature from Towers over Homogeneous Terrain. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 1973, 30, 788–794.

- Kelly, M.; Gryning, S.E. Long-Term Mean Wind Profiles Based on Similarity Theory. Boundary-Layer Meteor. 2010, 136, 377–390.

- Gryning, S.E.; Batchvarova, E.; Brümmer, B.; Jørgensen, H.; Larsen, S. On the extension of the wind profile over homogeneous terrain beyond the surface boundary layer. Boundary-Layer Meteor. 2007, 124, 371–379.

- Kelly, M.; Cersosimo, R.A.; Berg, J. A universal wind profile for the inversion-capped neutral atmospheric boundary layer. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2019, 145, 982–992. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Gadde, S.N.; Stevens, R.J. Universal Wind Profile for Conventionally Neutral Atmospheric Boundary Layers. Physical Review Letters 2021, 126, 104502. [CrossRef]

- Floors, R.; Peña, A.; Troen, I. Using observed and modelled heat fluxes for improved extrapolation of wind distributions. Boundary-Layer Meteorology 2023, 188, 75–101. [CrossRef]

- Ghannam, K.; Bou-Zeid, E. Baroclinicity and directional shear explain departures from the logarithmic wind profile. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2021, 147, 443–464. [CrossRef]

- Floors, R.; Pena, A.; Gryning, S.E. The effect of baroclinity on the wind in the Planetary boundary layer. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 2015, 141, 619–30.

- Narasimhan, G.; Gayme, D.F.; Meneveau, C. Analytical Wake Modeling in Atmospheric Boundary Layers: Accounting for Wind Veer and Thermal Stratification. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2024, 2767, 092018. [CrossRef]

- Lanzilao, L.; Meyers, J. A parametric large-eddy simulation study of wind-farm blockage and gravity waves in conventionally neutral boundary layers. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2024, 979. [CrossRef]

- Ott, S.; Nielsen, M. Developments of the offshore wind turbine wake model Fuga. Technical Report E-0046, Danish Technical University, 2014.

- Pedersen, M.M.; Forsting, A.M.; van der Laan, P.; Riva, R.; Alcayaga Romàn, L.A.; Criado Risco, J.; Friis-Møller, M.; Quick, J.; Schøler Christiansen, J.P.; Valotta Rodrigues, R.; et al. PyWake 2.5.0: An open-source wind farm simulation tool, 2023.

- Çengel, Y.A.; Cimbala, J.M. Fluid Mechanics: Fundamentals and Applications, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, 2018.

- Bou-Zeid, E.; Gao, X.; Ansorge, C.; Katul, G.G. On the role of return to isotropy in wall-bounded turbulent flows with buoyancy. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2018, 856, 61–78. [CrossRef]

- Lazeroms, W.M.J.; Svensson, G.; Bazile, E.; Brethouwer, G.; Wallin, S.; Johansson, A.V. Study of Transitions in the Atmospheric Boundary Layer Using Explicit Algebraic Turbulence Models. Boundary-Layer Meteorology 2016, 161, 19–47. [CrossRef]

- Baungaard, M.; Wallin, S.; van der Laan, M.P.; Kelly, M. Wind turbine wake simulation with explicit algebraic Reynolds stress modeling. Wind Energy Science 2022, 7, 1975–2002. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.; Barlas, E.; Sogachev, A. Statistical prediction of far-field wind-turbine noise, with probabilistic characterization of atmospheric stability. Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Pielke, R.A. Mesoscale meteorological modeling; Elsevier/Acad. Press, 2013; p. 726.

- Jiménez, P.A.; Dudhia, J. Improving the Representation of Resolved and Unresolved Topographic Effects on Surface Wind in the WRF Model. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 2012, 51, 300–316. [CrossRef]

- Pronk, V.; Bodini, N.; Optis, M.; Lundquist, J.K.; Moriarty, P.; Draxl, C.; Purkayastha, A.; Young, E. Can reanalysis products outperform mesoscale numerical weather prediction models in modeling the wind resource in simple terrain? Wind Energy Science 2022, 7, 487–504. [CrossRef]

- Vincent, C.L.; Badger, J.; Hahmann, A.N.; Kelly, M. The response of mesoscale models to changes in surface roughness. In Proceedings of the Geophysical Research Abstracts. European Geophysical Union (EGU) General Assembly, 2013, Vol. 15, p. 8548.

- Kelly, M.; Volker, P. WRF idealized-roughness response: PBL scheme and resolution dependence. In Proceedings of the Abstracts of the 16th EMS Annual Meeting; 11th European Conference on Applied Climatology (ECAC). European Meteorological Society, 12–16 Sep 2016, number EMS2016-389 in EMS Annual Meetings.

- Draxl, C.; Hahmann, A.N.; Peña, A.; Giebel, G. Evaluating winds and vertical wind shear from Weather Research and Forecasting model forecasts using seven planetary boundary layer schemes. Wind Energy 2014, 17, 39–55. [CrossRef]

- Haupt, S.E.; Jiménez, P.A.; Lee, J.A.; Kosović, B., Principles of meteorology and numerical weather prediction. In Renewable Energy Forecasting: From Models to Applications; Kariniotakis, G., Ed.; Woodhead / Elsevier, 2017; chapter 1, pp. 3–28. [CrossRef]

- Badger, J.; Frank, H.; Hahmann, A.N.; Giebel, G. Wind-Climate Estimation Based on Mesoscale and Microscale Modeling: Statistical-Dynamical Downscaling for Wind Energy Applications. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 2014, 53, 1901–1919. [CrossRef]

- Hahmann, A.N.; Vincent, C.L.; Peña, A.; Lange, J.; Hasager, C.B. Wind climate estimation using WRF model output: method and model sensitivities over the sea. International Journal of Climatology 2015, 35, 3422–3439. [CrossRef]

- Dörenkämper, M.; Olsen, B.T.; Witha, B.; Hahmann, A.N.; Davis, N.N.; Barcons, J.; Ezber, Y.; García-Bustamante, E.; González-Rouco, J.F.; Navarro, J.; et al. The Making of the New European Wind Atlas – Part 2: Production and evaluation. Geoscientific Model Development 2020, 13, 5079–5102. [CrossRef]

- Davis, N.N.; Badger, J.; Hahmann, A.N.; Hansen, B.O.; Mortensen, N.G.; Kelly, M.; Larsén, X.G.; Olsen, B.T.; Floors, R.; Lizcano, G.; et al. The Global Wind Atlas: A High-Resolution Dataset of Climatologies and Associated Web-Based Application. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2023, 104, E1507–E1525. [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, N.G.; Landberg, L.; Rathmann, O.; Frank, H.P.; Troen, I.; Petersen, E.L. Wind atlas analysis and application program (WAsP). Report, Risø National Laboratory, Roskilde, Denmark, 2001.

- Hahmann, A.N.; Lennard, C.; Badger, J.; Vincent, C.L.; Kelly, M.; Volker, P.J.; Argent, B.; Refslund, J. Mesoscale modeling for the Wind Atlas of South Africa (WASA) project. Technical Report DTU Wind Energy E-0050(EN), Wind Energy Dept., Risø Lab/Campus, Danish Tech. Univ. (DTU), Roskilde, Denmark, 2015.

- Gaumond, M.; Réthoré, P.; Ott, S.; Peña, A.; Bechmann, A.; Hansen, K.S. Evaluation of the wind direction uncertainty and its impact on wake modeling at the Horns Rev offshore wind farm. Wind Energy 2014, 17, 1169–1178. [CrossRef]

- BIPM.; IEC.; IFCC.; ILAC.; ISO.; IUPAC.; IUPAP.; OIML. Evaluation of measurement data — Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement, 2008. [CrossRef]

- BIPM.; IEC.; IFCC.; ILAC.; ISO.; IUPAC.; IUPAP.; OIML. Evaluation of measurement data — Supplement 1 to the “Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement” — Propagation of distributions using a Monte Carlo method, 2008. [CrossRef]

- BIPM.; IEC.; IFCC.; ILAC.; ISO.; IUPAC.; IUPAP.; OIML. Evaluation of measurement data — Supplement 2 to the “Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement” — Extension to any number of output quantities, 2011. [CrossRef]

- BIPM.; IEC.; IFCC.; ILAC.; ISO.; IUPAC.; IUPAP.; OIML. Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement — Part 1: Introduction. Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology, JCGM GUM-1:2023, 2023. [CrossRef]

- BIPM.; IEC.; IFCC.; ILAC.; ISO.; IUPAC.; IUPAP.; OIML. Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement — Part 6: Developing and using measurement models. Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology, JCGM GUM-6:2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, H.W.; Steele, W.G. Experimentation, Validation, and Uncertainty Analysis for Engineers; Wiley, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Huard, D.; Mailhot, A. A Bayesian perspective on input uncertainty in model calibration: Application to hydrological model “abc”. Water Resources Research 2006, 42. [CrossRef]

- Murcia Leon, J.P. Uncertainty quantification in wind farm flow models. Phd dissertation, Danish Technical University, Risø Campus, Roskilde, Denmark, 2017.

- Forbes, A.B. Approaches to evaluating measurement uncertainty. International Journal of Metrology and Quality Engineering 2012, 3, 71–77. [CrossRef]

- Bich, W. Revision of the ‘Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement’: Why and how. Metrologia 2014, 51, S155–S158. [CrossRef]

- Efremova, N.Y.; Chunovkina, A.G. Development of the Concept of Uncertainty in Measurement and Revision of Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement. Part 1. Reasons and Probability-Theoretical Bases of the Revision. Measurement Techniques 2017, 60, 317–324. [CrossRef]

- Efremova, N.Y.; Chunovkina, A.G. Development of the Concept of Uncertainty in Measurement and Revision of the Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement. Part 2. Comparative Analysis of Basic Provisions of the Guide and Their Planned Changes. Measurement Techniques 2017, 60, 418–424. [CrossRef]

- Hills, R.G.; Maniaci, D.C.; Naughton, J.W. V & V framework. Technical Report SAND2015-7455, Sandia National Laboratories, Albequerque & Livermore, USA, 2015. [CrossRef]

- ASME. Standard for Verification and Validation in Computational Fluid Dynamics andHeat Transfer; The American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, 2009.

- Mortensen, N.G.; Jørgensen, H.E.; Anderson, M.; Hutton, K. Comparison of resource and energy yield assessment procedures. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of EWEA 2012 - European Wind Energy Conference & Exhibition, EWEA, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012.

- Mortensen, N.G.; Jørgensen, H.E. Comparison of resource and energy yield assessment procedures (CREYAP), Part II. In Proceedings of the EWEA Technology Workshop: Resource Assessment, EWEA, Dublin, Ireland, 2013. Powerpoint.

- Mortensen, N.G.; Nielsen, M.; Jørgensen, H.E. Comparison of resource and energy yield assessment procedures 2011-2015: What have we learned and what needs to be done? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the EWEA Annual Event and Exhibition 2015, European Wind Energy Association (EWEA), Paris, France, 2015. 10 pp.

- Fischereit, J.; Hansen, K.S.; Larsén, X.G.; van der Laan, M.P.; Réthoré, P.E.; Leon, J.P.M. Comparing and validating intra-farm and farm-to-farm wakes across different mesoscale and high-resolution wake models. Wind Energy Science 2022, 7, 1069–1091. [CrossRef]

- van der Laan, M.P.; García-Santiago, O.; Kelly, M.; Forsting, A.M.; Dubreuil-Boisclair, C.; Seim, K.S.; Imberger, M.; Peña, A.; Sørensen, N.N.; Réthoré, P.E. A new RANS-based wind farm parameterization and inflow model for wind farm cluster modeling. Wind Energy Science 2023, 8, 819–848. [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, N.G.; Nielsen, M.; Jørgensen, H.E. First Offshore Comparative Resource and Energy Yield Assessment Procedures (CREYAP). In Proceedings of the EWEA Offshore, EWEA, Frankfurt, Germany, 2013.

- Mortensen, N.G.; Nielsen, M.; Jørgensen, H. Offshore CREYAP Part 2 – final results. In Proceedings of the EWEA Technology Workshop: Resource Assessment, European Wind Energy Association, Helsinki, Finland, 2015.

- Badger, J.; Cavar, D.; Nielsen, M.; Mortensen, N.G.; Hansen, B.O. CREYAP 2021. In Proceedings of the WindEurope Technology Workshop 2021: Resource Assessment & Analysis of Operating Wind Farms, EWEA, online (pandemic-accomodation), 2021.

- Maniaci, D.; Naughton, J.; Haupt, S.; Jonkman, J.; Robertson, A.; Churchfield, M.; Johnson, N.; Hsieh, A.; Cheung, L.; Herges, T.; et al. Offshore Wind Energy Validation Experiment Hierarchy. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 2024, Vol. 2767, Offshore Wind, p. 062039. [CrossRef]

- Stadtmann, F.; Rasheed, A.; Kvamsdal, T.; Johannessen, K.A.; San, O.; Kölle, K.; Tande, J.O.; Barstad, I.; Benhamou, A.; Brathaug, T.; et al. Digital Twins in Wind Energy: Emerging Technologies and Industry-Informed Future Directions. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 110762–110795. [CrossRef]

- IEC. Wind turbine generator systems – Part 50: Wind measurement – Overview; International Electrotechnical Comission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- IEC. Wind turbine generator systems – Part 50-1: Wind measurement – Application of meteorological mast, nacelle and spinner mounted instruments; International Electrotechnical Comission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- IEC. Wind turbine generator systems – Part 50-2: Wind measurement – Application of ground-mounted remote sensing technology; International Electrotechnical Comission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- IEC. Wind turbine generator systems – Part 50-3: Use of Nacelle-Mounted Lidars for Wind Measurements; International Electrotechnical Comission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- IEC. Wind turbine generator systems – Part 12: Power Performance Measurements of Electricity Producing Wind Turbines – Overview; International Electrotechnical Comission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- IEC. Wind turbine generator systems – Part 12-1: Power Performance Measurements of Electricity Producing Wind Turbines; International Electrotechnical Comission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- IEC. Wind turbine generator systems – Part 12-2: Power Performance Measurements of Electricity Producing Wind Turbines Based on Nacelle Anemometry; International Electrotechnical Comission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- IEC. Wind turbine generator systems – Part 12-3: Power Performance – Measurement Based Site Calibration; International Electrotechnical Comission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- IEC. Wind turbine generator systems – Part 12-6: Measurement Based Nacelle Transfer Function of Electricity Producing Wind Turbines; International Electrotechnical Comission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- MEASNET. Anemometer Calibration Procedure. Technical Report v3, Measuring-Network of Wind Energy Institutes, 2020.

- Clerc, A.; Anderson, M.; Stuart, P.; Habenicht, G. A systematic method for quantifying wind flow modelling uncertainty in wind resource assessment. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 2012, 111, 85–94. [CrossRef]

- Troen, I.; Bechmann, A.; Kelly, M.; Sørensen, N.N.; Réthoré, P.E.; Cavar, D.; Ejsing Jørgensen, H. Complex terrain wind resource estimation with the wind-atlas method: Prediction errors using linearized and nonlinear CFD micro-scale models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2014 EWEA conference, Barcelona, 2014.

- Kelly, M.; Kersting, G.; Mazoyer, P.; Yang, C.; Fillols, F.H.; Clark, S.; Matos, J.C. Uncertainty in vertical extrapolation of measured wind speed via shear. Technical Report DTU Wind Energy E-0195(EN), Wind Energy Dept., Risø Lab/Campus, Danish Tech. Univ. (DTU), Roskilde, Denmark, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Triviño, C.; Leask, P.; Ostridge, C. Validation of Vertical Wind Shear Methods. Journal of Physics: Conference Series–WindEurope Conference, Session 2 2017, 926. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M. Uncertainty in vertical extrapolation of wind statistics: shear-exponent and WAsP/EWA methods. Technical Report DTU Wind Energy E-0121(EN), Wind Energy Dept., Risø Lab/Campus, Danish Tech. Univ. (DTU), Roskilde, Denmark, 2016.

- Yan, J.; Möhrlen, C.; Göçmen, T.; Kelly, M.; Wessel, A.; Giebel, G. Uncovering wind power forecasting uncertainty sources and their propagation through the whole modelling chain. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 165, 112519. [CrossRef]

- Möhrlen, C.; Bessa, R.J.; Fleischhut, N. A decision-making experiment under wind power forecast uncertainty. Meteorological Applications 2022, 29. [CrossRef]

- Hahmann, A.N.; Sīle, T.; Witha, B.; Davis, N.N.; Dörenkämper, M.; Ezber, Y.; García-Bustamante, E.; González-Rouco, J.F.; Navarro, J.; Olsen, B.T.; et al. The making of the New European Wind Atlas – Part 1: Model sensitivity. Geoscientific Model Development 2020, 13, 5053–5078. [CrossRef]

- Lenschow, D.H.; Mann, J.; Kristensen, L. How long is long enough when measuring fluxes and other turbulence statistics? J. Atmos. Ocean Technol. 1994, 11, 661–673.

- MEASNET. Evaluation of Site-specific Wind Conditions. Technical Report v3, Measuring-Network of Wind Energy Institutes, 2022.

- IEC. Standard 61400–15-1. Wind energy generation systems – Part 15-1: Design requirements for floating offshore wind turbines; International Electrotechnical Comission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- der Kiureghian, A.; Ditlevsen, O. Aleatory or epistemic? Does it matter? Structural Safety 2009, 31, 105–112. Risk Acceptance and Risk Communication.

- Kelly, M.; Jørgensen, H.E. Statistical characterization of roughness uncertainty and impact on wind resource estimation. Wind Energy Science 2017, 2, 189–209. [CrossRef]

- Hale, E. The Uncertainty of Uncertainty. In Proceedings of the NREL 3rd Wind Energy Systems Engineering Workshop, Boulder, Colorado, USA, January 2015; [https://www.nrel.gov/wind/systems-engineering-workshop-2015.html].

- Lee, J.C.; Jason Fields, M. An overview of wind-energy-production prediction bias, losses, and uncertainties. Wind Energy Science 2021, 6, 311–365. [CrossRef]

| 1 | The potential temperature is the buoyancy variable or `meteorologist’s entropy’ [7]; it accounts for the change in temperature due to decreasing static pressure with height, and the virtual aspect (subscript v) accounts for the effect of humidity. It is defined as approximately where J kg−1K−1 is the specific gas constant for dry air and is the temperature-dependent specific heat capacity for constant pressure, such that is unitless and constant in ABL application. |

| Component (bold) or sub-component (italic) |

|---|

| Measurement Uncertainty |

| wind speed measurement |

| wind direction measurement / rose |

| other atmospheric parameters |

| data integrity and documentation |

| Historical Wind Resource (LTC) |

| representativeness of long-term reference period |

| reference data consistency |

| long-term correction method |

| on-site gap-filling/synthesis |

| representativeness of measured data |

| wind distribution fit |

| Horizontal Extrapolation and flow modelling |

| model inputs |

| model `stress’ (deviation from operational envelope) |

| model appropriateness |

| Vertical (power-law) Extrapolation |

| model representativeness† |

| excess uncertainty propagated by VE-model |

| Project Evaluation Period Variability |

| interannual variability (IAV) of wind speed |

| climate change |

| (IAV of plant performance)‡ |

| Plant Performance |

| Turbine interaction/wake and blockage effects |

| (non-wind elements)‡ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).