1. Introduction

The physiologic consequences of inflammation involve numerous alterations of the proteome1,2 and of the lipid metabolism,3 the formation of reactive oxygen species,4 and lipid peroxidation products.5 While cytokines such as interleukin 1-beta are considered to represent potent promotors of inflammation, the pharmacological inhibition of the formation of oxylipins represents the mode of action of the most widely used antiphlogistic drugs,6,7 pointing to the clinical relevance of oxylipins as modulators of inflammatory processes. Furthermore, lipids are considered to represent critical factors managing the resolution of inflammation,8 the failure of which may characterize chronic inflammation.9

It is thus evident that inflammatory processes may be initiated, regulated, and modulated via both proteins and lipid mediators. Cytokines belong to the main transcriptional targets of inflammatory signaling via NF-kappaB, STATs family members, MAP kinases, and other.10,11 In vivo, cytokines act in a systemic fashion and may cause an escalation, called “cytokine storm”, characteristic for some acute disease states.12-14 In contrast, lipid mediators are primarily considered to represent modulators acting mainly locally due to their limited half-life. However, the abundance levels and physiologic effects of lipid mediators may also escalate during acute infection.15

The most important marker molecules used for diagnostic purposes are acute phase proteins such as CRP (C-reactive protein) and SAA1, produced by the liver, and calprotectin produced by innate immune cells.16-18 In contrast, the detection of cytokines and oxylipins requires dedicated assays and specialized laboratory equipment hardly used for routine diagnostics. Systemic effects of inflammation on proteins, lipids and nucleic acids and the consequences thereof have already been inestigated.19-21 However, only few studies investigated oxylipin alterations in blood plasma.22 The understanding of molecular mechanisms linking proteins and lipids in various innate and adaptive immune cell activities, as described in case of long COVID23 and ulcerative colitis,24 may help to improve therapeutic strategies.

Indeed, the therapeutic modulation of immune functions by antioxidants has been considered and evidenced for many years, 25-27 and promoted a profound discussion regarding the use of nutritional supplementation.28 Whether and how inflammatory processes might be modulated via nutritional supplementation with antioxidants including polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) is still not fully understood in humans. Apparently, several organ systems and enzymatic activities may be involved in such modulatory events.

To address these questions in humans, we are employing prospective clinical trials. Previously, we have presented a clinically standardized experimental systemic inflammation model based on the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge of healthy human individuals.29-31 The inflammation-induced hyperoxia was successfully quantified by retinal blood flow measurements. Notably, a reduced response of retinal vascular reactivity to systemic hyperoxia was effectively restored by a 2-week antioxidant supplementation.32 A modulation of systemic inflammatory processes through this intervention was already successfully demonstrated via studies on retinal blood flow parameters. In the present study, we have analyzed the molecular alterations in blood plasma including proteins and oxylipins accompanying these effects. We preferred the use of blood plasma to serum in order to avoid confounding effects as described earlier. 33 Thus, the presently described effects of the antioxidative supplementation on inflammation-related proteome and oxylipin alterations are based on a randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled parallel group study design.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Study Design

Subjects were recruited by the Department of Clinical Pharmacology at the Medical University of Vienna. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EC No.: 64/2009) and conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration. For this randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled parallel group study, 30 healthy male human individuals were included upon passing a screening examination and signed written informed consent prior to study entry. Participants with any clinically relevant illness, intake of medication, including vitamin or mineral supplements, or blood donation within three weeks prior to the study were excluded. Individuals who did not complete the study were replaced. In addition, participants had to abstain from alcohol- or caffeine-containing beverages within 12 hours prior to each study day of the dual stage interventional trial, which was randomized and placebo-controlled during the second stage.

To induce systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, an intravenous infusion of a bolus containing 2 ng/kg bodyweight

Escherichia coli endotoxin known as lipopolysaccharide (LPS; NIH-CC, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used. Whole blood was collected using EDTA-anticoagulated collection tubes at baseline (BL), 60 min, 120 min, 240 min and 480 min after LPS infusion. Plasma was obtained immediately by centrifugation at 4 °C at 2000 g for 10 min. After centrifugation, all samples were immediately frozen in pre-labelled Eppendorf safe-lock tubes at -80 °C until analysis. After this first stage, participants were randomly assigned to take either the omega-3 fatty acid containing food supplement Vitamac (n = 17; Croma Pharma GmbH, Korneuburg, Austria) or matching lactose and wheat starch containing placebo capsules (n = 13) for 14 days. The ingredients of the food supplement are specified in

Supplementary Table S1. After the 14-day intervention, all participants were challenged again with LPS in the second stage and plasma was collected at baseline (BL), 60 min, 120 min, 240 min and 480 min after LPS infusion applying the same protocol described for the first stage.

2.2. Plasma Proteomics

For the untargeted plasma proteomics analysis, plasma samples were thawed on ice and diluted 1:20 in lysis buffer (8 M urea, 50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB), 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)). After heating at 95 °C for 5 min, the protein concentration was determined using a BCA assay, and 20 µg of protein was digested applying the ProtiFi S-trap technology.33 Here, a reduction and carbamidomethylation of solubilized proteins was performed using dithiothreitol (DTT) and iodoacetamide (IAA). Samples were then loaded onto S-trap mini cartridges, washed, and digested using a Trypsin/Lys-C Mix (1:40 enzyme to substrate ratio) at 37 °C for 2 hours. Upon digestion, the resulting peptides were eluted, dried, and stored at -20 °C until liquid chromatography - tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis.

For the LC-MS/MS analysis, samples were reconstituted in 5 µL 30% formic acid (FA) containing synthetic standard peptides and diluted with 40 µL loading solvent (97.9% H2O, 2% acetonitrile (ACN), 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid). Separation of peptides was achieved using a Dionex Ultimate3000 nanoLC-system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with an analytical column (25 cm x 75 µm, 1.6 µm C18 Aurora Series emitter column (Ionopticks)). The injection volume was 1 µL, the flow rate was 300 nL/min, and the total run time was 85 min including column washing and equilibration. The gradient flow profile started at 7% and increased to 40% mobile phase B (79.9% ACN, 20% H2O, 0.1% FA) over 43 min. The nanoLC-system was coupled to the timsTOF Pro mass spectrometer (Bruker) equipped with a captive spray ion source operating in Parallel Accumulation-Serial Fragmentation mode as previously described.23

Data analysis including protein identification and label-free quantification (LFQ), was performed using the MaxQuant software package version 1.6.17.0 running the Andromeda search engine.34 Raw data were searched against the SwissProt database “homo sapiens” (version 141219 with 20380 entries) allowing a maximum of two missed cleavages, a peptide tolerance of 20 ppm, carbamidomethylation on cysteines as fixed modification as well as methionine oxidation and N-terminal protein acetylation as variable modification. A minimum of one unique peptide per protein was required for positive identification, the “match between runs” option and a false discovery rate (FDR) ≤ 0.01 was applied. Identified proteins were filtered for common contaminants and reversed sequences using the Perseus software package version 1.6.14.0.35 LFQ intensities were log2-transformed, filtered for their number of independent identifications in a minimum of 70% of samples in at least one group and missing values were replaced from a normal distribution. Volcano plots were generated using the Perseus software package version 1.6.14.0, and the time course profile of proteins was plotted using GraphPad Prism version 6.07 (2015).

2.3. Plasma Lipidomics

LC-MS/MS analysis of lipid mediators was performed as described previously.

23 Briefly, plasma samples were thawed on ice, and 400 µL of plasma was then mixed with cold ethanol (EtOH; 1.6 mL, abs. 99%, -20 °C; AustrAlco) including an internal oxylipin standard mixture (Cayman Chemical, Tallinn, Estonia). The exact concentrations of each internal standard can be found in

Supplementary Table S2. Samples were stored at -20 °C overnight for protein precipitation. Solid phase extraction (SPE) was performed using StrataX SPE columns (30 mg mL

−1; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The eluted samples were dried, reconstituted in 150 µL reconstitution solvent (H

2O:ACN:methanol (MeOH) + 0.2% FA–vol% 65:31.5:3.5), subsequently transferred into an autosampler held at 4 °C and measured

via LC-MS/MS.

For the untargeted LC-MS/MS analysis, lipid mediators were separated using a Thermo Scientific

TM Vanquish

TM (UHPLC) system equipped with a Kinetex® XB-C18-column (2.6 μm XB-C18 100 Å, LC Column 150 × 2.1 mm; Phenomenex®). A gradient flow profile was applied starting at 35% mobile phase B (mobile phase A: H

2O + 0.2% FA, mobile phase B: ACN:MeOH (vol% 90:10) + 0.2% FA), increasing to 90% B (1–10 min), further increasing to 99% B within 0.5 min and held for 5 min. Solvent B was then decreased to the initial level of 35% within 0.5 min, and the column was equilibrated for 4 min, resulting in a total run time of 20 min. The flow rate was 0.2 mL/min, the injection volume was 20 µL, and the column temperature was 40 °C. All samples were measured in technical duplicates in negative ionization mode, whereas one injection was performed in positive ionization mode. For the mass spectrometric analysis, the Vanquish

TM (UHPLC) system was coupled to a Q Exactive

TM HF Quadrupole-Orbitrap

TM high-resolution mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific

TM, Austria), equipped with a HESI source operating in negative and positive ionization mode. The MS scan range was set to 250-700

m/z with a resolution of 60,000 (at

m/z 200) on the MS1 level and 15,000 (at

m/z 200) on the MS2 level. For the fragmentation, a Top 2 method (HCD 24 normalized collision energy) with an inclusion list was applied (

Supplementary Table S3). The spray voltage was set to 3.5 kV in negative and positive ionization mode, and the capillary temperature to 253°C. Sheath gas was set to 46 and auxiliary gas to 10 arbitrary units.

For the data analysis, analytes were compared to an in-house established compound database based on the exact mass and retention time on the MS1 level using the TraceFinder

TM software package version 4.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific

TM). In addition, MS/MS fragmentation spectra were compared to reference spectra of in-house measured, commercially available standards or to reference spectra from the LIPID MAPS depository library from March 2023.

36 The degree of identification of all analytes is shown in

Supplementary Table S4. Subsequently, relative quantification of the identified analytes was performed on the MS1 level using the TraceFinder

TM software package version 4.1. The resulting peak areas were loaded into the R software package environment version 4.2.0,

37 log2-transformed and normalized to the internal standards. Therefore, the mean log2-transformed peak area of the internal standards was subtracted from the log2-transformed analyte peak area. To enable missing value imputation using the minProb function of the imputeLCMD package version 2.1, the log2-transformed normalized peak areas were increased by 20.

38 Significant differences between the study cohorts were determined using a linear model and the empirical Bayes method implemented in the limma R package and the resulting p-values were adjusted for multiple testing according to the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure

39,40. Data visualization was performed using the ggplot2 R package.

41

2.4. Data Sharing Statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE42 partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD051013.

Data derived from the lipid mediator analysis are available at the NIH Common Fund's National Metabolomics Data Repository (NMDR) website, the Metabolomics Workbench,

https://www.metabolomicsworkbench.org43 where they have been assigned to the following studies: Study ID ST003137 and ST003138. The DOI for this project (PR001950) is:

http://dx.doi.org/10.21228/M8NX50.

3. Results

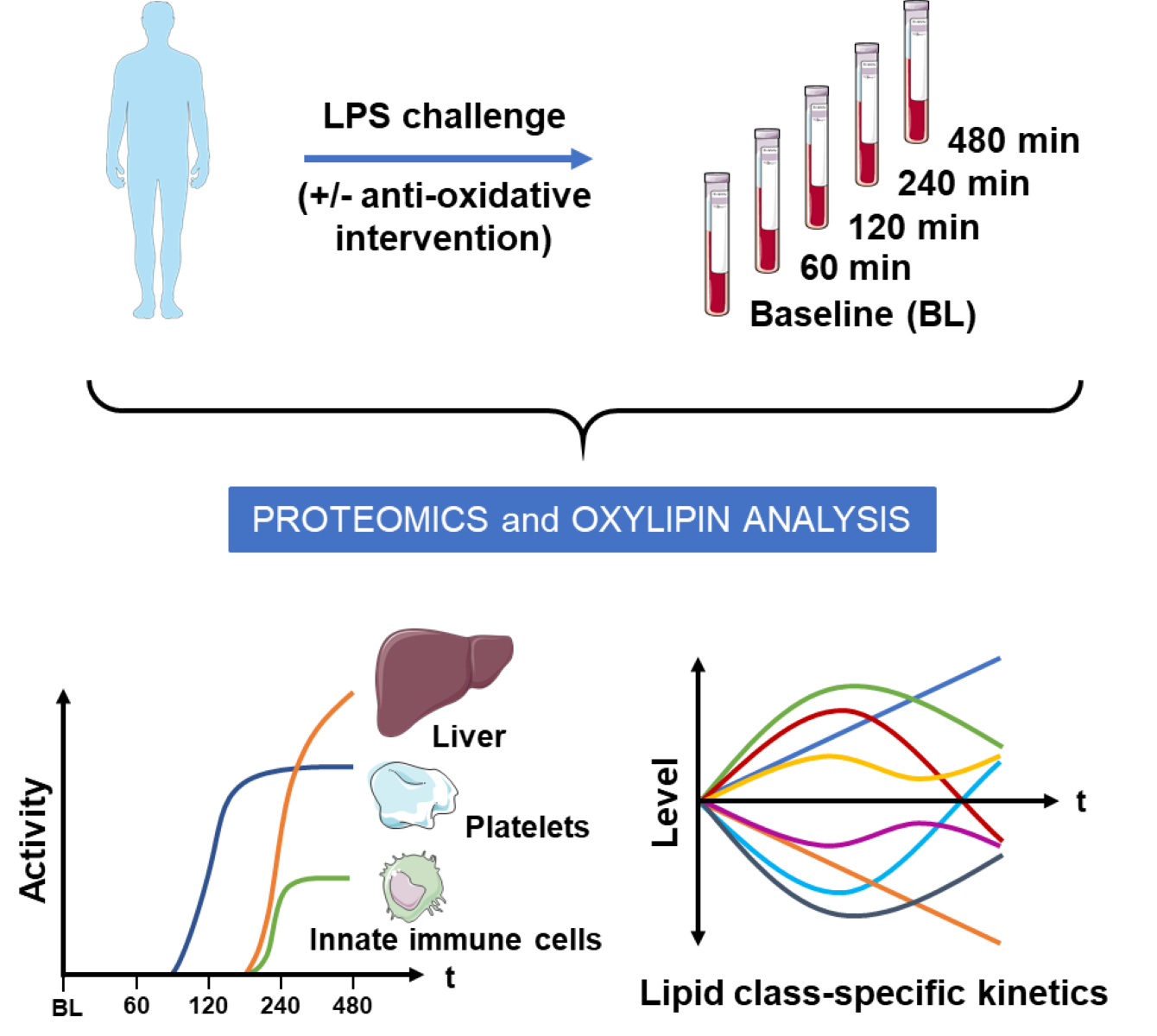

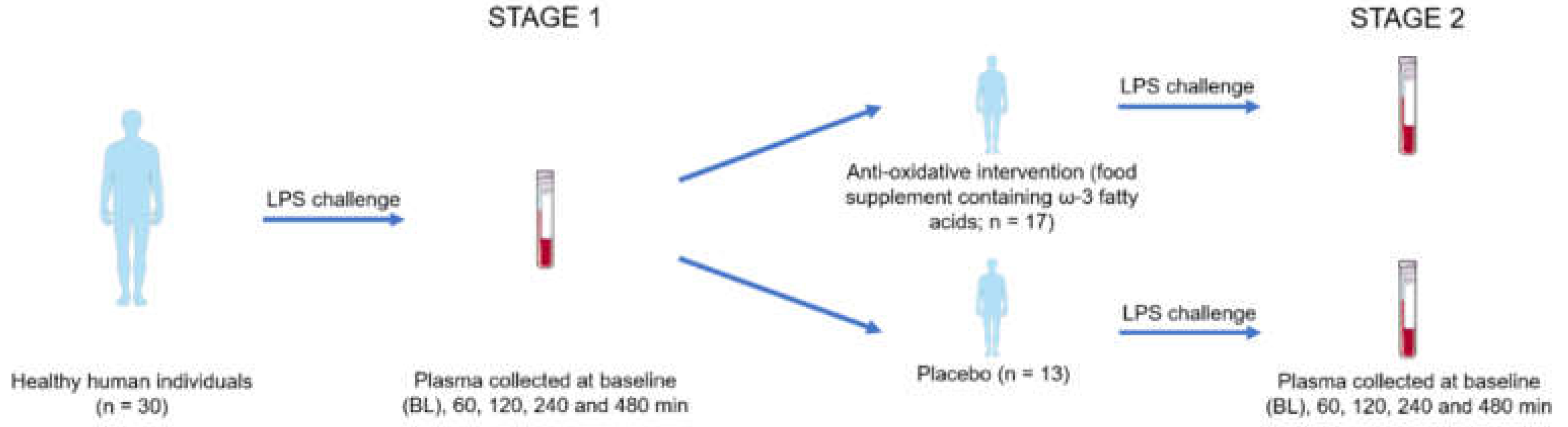

This clinical intervention study consisted of two stages. At stage 1, the inflammatory responses to an LPS intervention were investigated using proteome profiling and oxylipin analysis. The hypothesis, that an antioxidative intervention may affect inflammatory responses was investigated at stage 2 employing a placebo-controlled study design (

Figure 1).

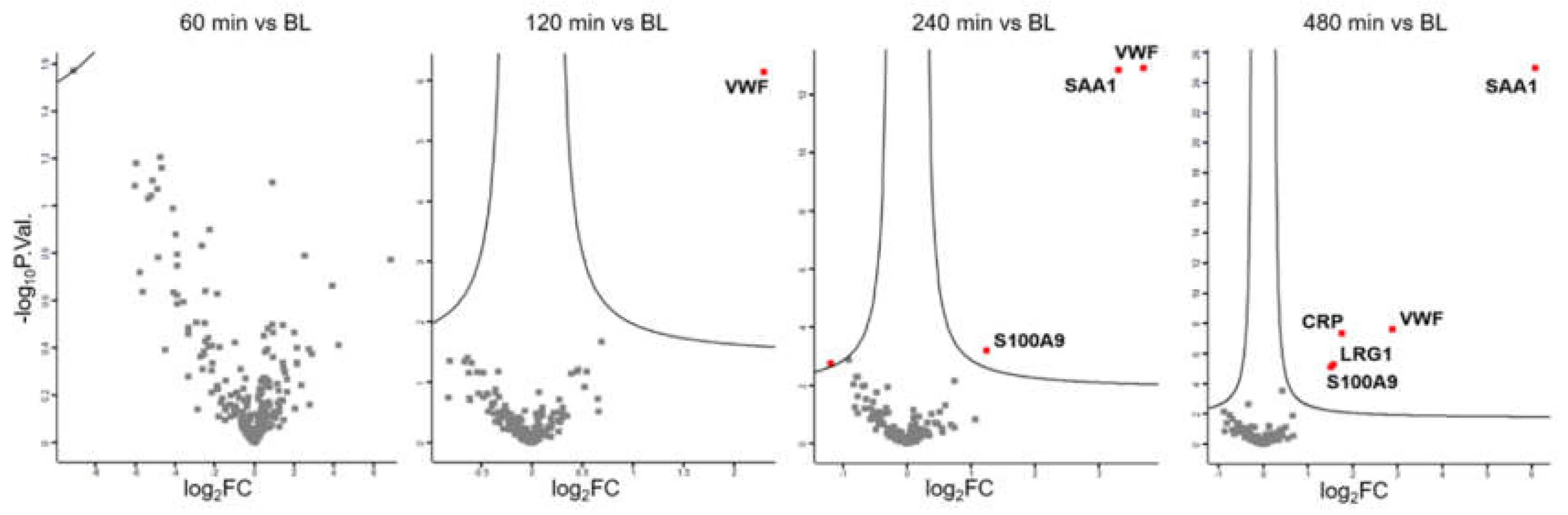

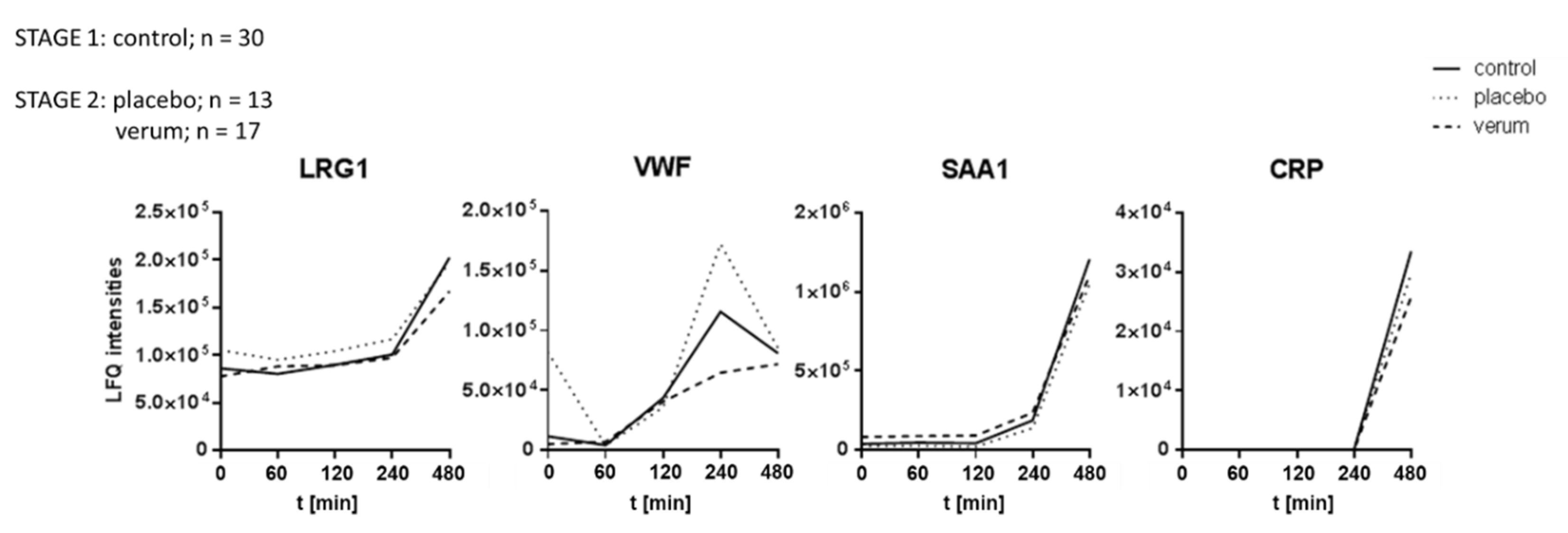

3.1. Plasma Proteome Profiling Indicates the Involvement of Endothelial Cells, Platelets, Innate Immune Cells, and the Liver During LPS-Induced Inflammation

Plasma was collected from 30 individuals at baseline (BL) and 60 minutes, 120 minutes, 240 minutes and 480 minutes after LPS challenge (

Figure 1, stage 1). Label-free shotgun analysis identified a total of 226 proteins after filtering for high confidence (FDR<0.01 at protein and peptide level, two peptide identifications per protein) and robustness (independent identification of each protein in at least 21 out of 30 samples (70%) per time point). Paired t-tests identified no significant event 60 minutes after LPS challenge, whereas the platelet- and endothelium-derived protein VWF

44,45 was found increased two hours after challenge. After another two hours, the liver-derived biomarker for inflammation, SAA1, and the innate immune cell-derived alarmin, S100A9, were found to be upregulated. Only 8 hours after the challenge, the acute phase protein CRP was found to be upregulated, in addition to LRG1 (

Figure 2).

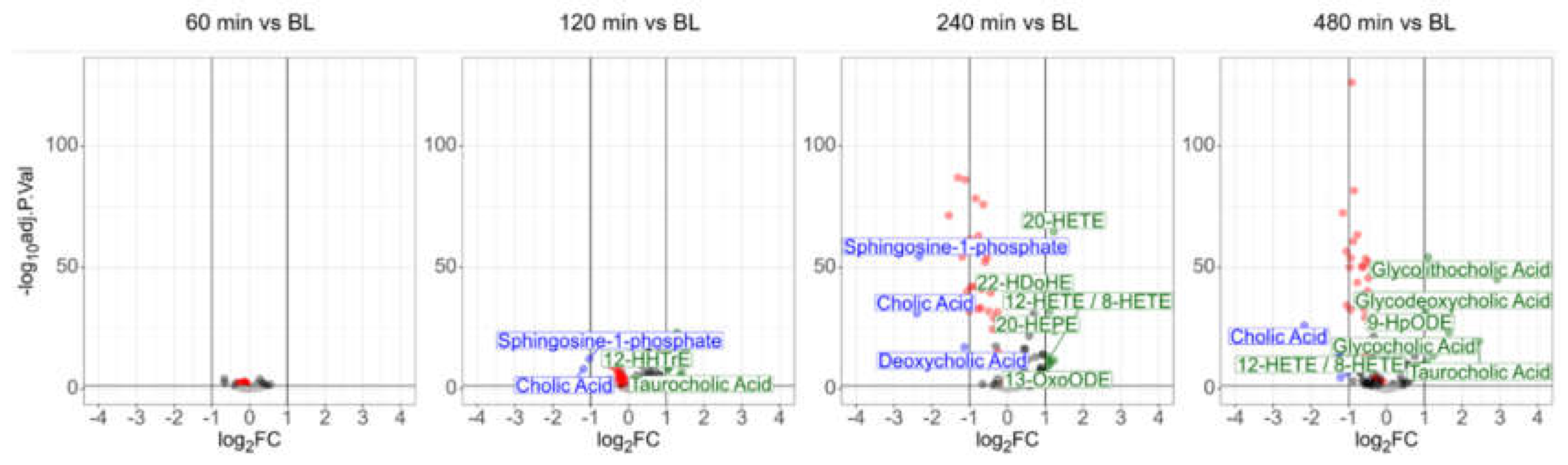

3.2. Plasma Lipidomics Demonstrates Immediate Adaptive Response Involving Oxylipins, Bile Acids, and the Lands Cycle in Response to LPS Challenge

The oxylipin assay based on the MS analysis of small lipids identified 25 fatty acids, 53 oxylipins, 28 lysolipids, six bile acids, four endocannabinoids, cortisol, and sphingosine-1-phosphate in the human plasma samples. All molecules were identified reproducibly (independent identification in >60% of the members of at least one group),

via exact mass (deviation < 2ppm), the isotopic patterns and the molecular fragment ions (MS2 spectra). Seventy-one identifications were verified using analytical standards (

Supplementary Table S4). Another 18 molecules were identified as oxylipins based on the sum formula and fragment spectra. However, due to structural ambiguity of oxylipin isobars it was not yet possible to assign unambiguous structures to these features. These oxylipins have been designated here as “molecular mass_chromatographic retention time” (

Supplementary Table S4).

Paired t-tests again identified no significant event 60 minutes after LPS challenge, whereas ten different molecules were found to be significantly deregulated (adjusted p-value<0.01, more than 2-fold regulated) after 120 min. Beside the polyunsaturated fatty acids stearidonic acid, alpha- and gamma-linolenic acid and

trans-isoforms thereof, also a

trans-isoform of DHA was found to be upregulated (

Supplementary Table S6). The upregulation of the platelet-derived oxylipins TxB2 (significant but less than two-fold), 12-HHTrE, and 12-HETE as described previously

45 indicated an early involvement of platelets. The upregulation of taurocholic acid and a downregulation of cholic acid indicated an early involvement of the liver. After another two hours, the uniform downregulation of various lysophospholipids was striking. The lysophospholipid LPC (0:0/18:2) exhibited a downregulation to approximately 53% of its initial value after 8 hours (remaining below a 2-fold change), with an adjusted p-value better than 1E-126. Plasma lysophospholipid levels correspond to the Lands cycle, responsible for the remodeling of phospholipids upon oxidative stress.

46 The present data thus demonstrated a direct involvement of the Lands cycle in the systemic response to LPS. In addition, one of the best-characterized sphingolipids, sphingosine-1-phosphate, was significantly downregulated as well upon LPS challenge. This sphingolipid is a specific product of erythrocyte and platelet metabolism and an essential regulator of inflammatory signaling.

47,48

On the other hand, the anti-inflammatory PUFA-derived oxylipins 13-OxoODE, 20-HETE, 22-HDoHE, 20-HEPE were upregulated. Eight hours after LPS challenge, most of these alterations remained detectable. Remarkably, the polyunsaturated fatty acids stearidonic acid, alpha- and gamma-linolenic acid, and

trans-isoforms thereof were found downregulated at that time, demonstrating complex dynamics. This observation may indicate some rapid adaptive responses of the human organism, as the anti-inflammatory bile acids glycolithocholic acid, glycodeoxycholic acid and glycocholic acid were found to be upregulated at this time point (

Figure 3).

3.3. Dietary Antioxidant Supplementation Does Not Affect the Kinetics of Inflammatory Marker Proteins Within Eight Hours After LPS Challenge

After stage 1 of the analysis, the donors were divided into two groups, and treated for 14 consecutive days either with placebo (n=13) or an antioxidative treatment scheme (verum, n=17), as depicted in

Figure 1. All participants were then again treated with LPS as described above to obtain a similar time series of plasma samples. All LPS-induced proteome alterations observed during the first part of the study were reproduced. However, no significant event was detected when comparing the antioxidant treatment group to the placebo group at any time. Depicting time courses of average values of selected proteins demonstrates the uniformity of the three groups (

Figure 4). These observations suggested that the antioxidant intervention had no detectable effect on the expression of inflammatory marker proteins.

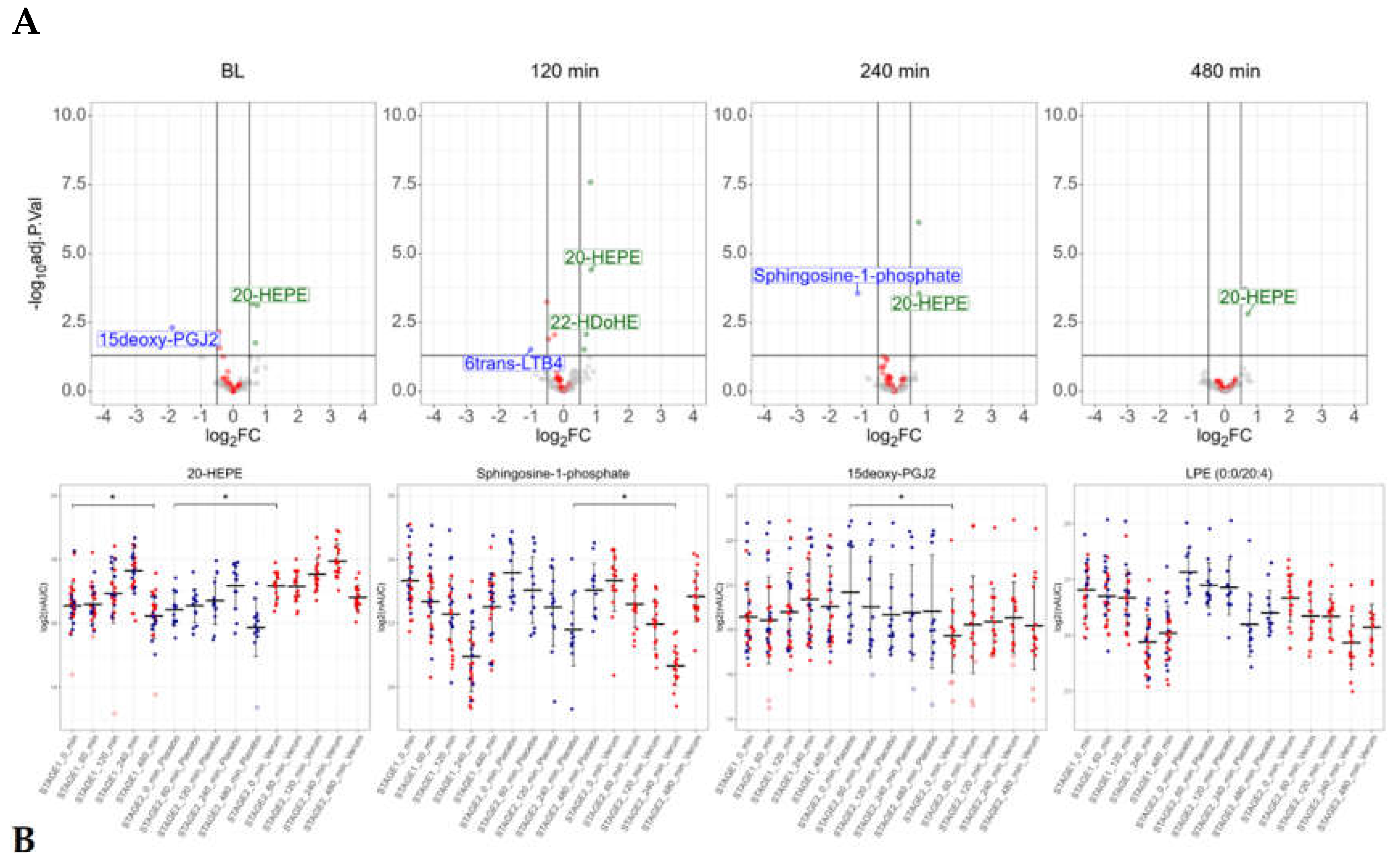

3.4. Dietary Antioxidant Supplementation Increases Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators and Downregulates Sphingosine-1-Phosphate After the LPS Challenge

The antioxidative intervention, lasting for 14 days, resulted in significant alterations of the plasma oxylipin composition: the PPAR-gamma agonist 15-deoxy-PGJ2 was found downregulated, whereas the anti-inflammatory 20-HEPE was found upregulated (

Figure 5A, baseline). This may be remarkable, as 20-HEPE was found at stage 1 to be upregulated during the LPS-intervention.

Almost all LPS-induced alterations of oxylipins observed at stage 1 were reproduced at stage 2, with only minor differences between the two groups. Only in the antioxidant group, two hours after LPS, the anti-inflammatory DHA-derived oxylipin 22-HDoHE was found upregulated, whereas the neutrophil-derived catabolic product of the pro-inflammatory leukotriene LTB4, 6trans-LTB4, was found downregulated (

Figure 5A). Sphingosine-1-phosphate, a specific product of erythrocyte and platelet metabolism, was consistently downregulated in the antioxidant treatment group, with a significant difference 4 hours after LPS challenge (

Figure 5B).

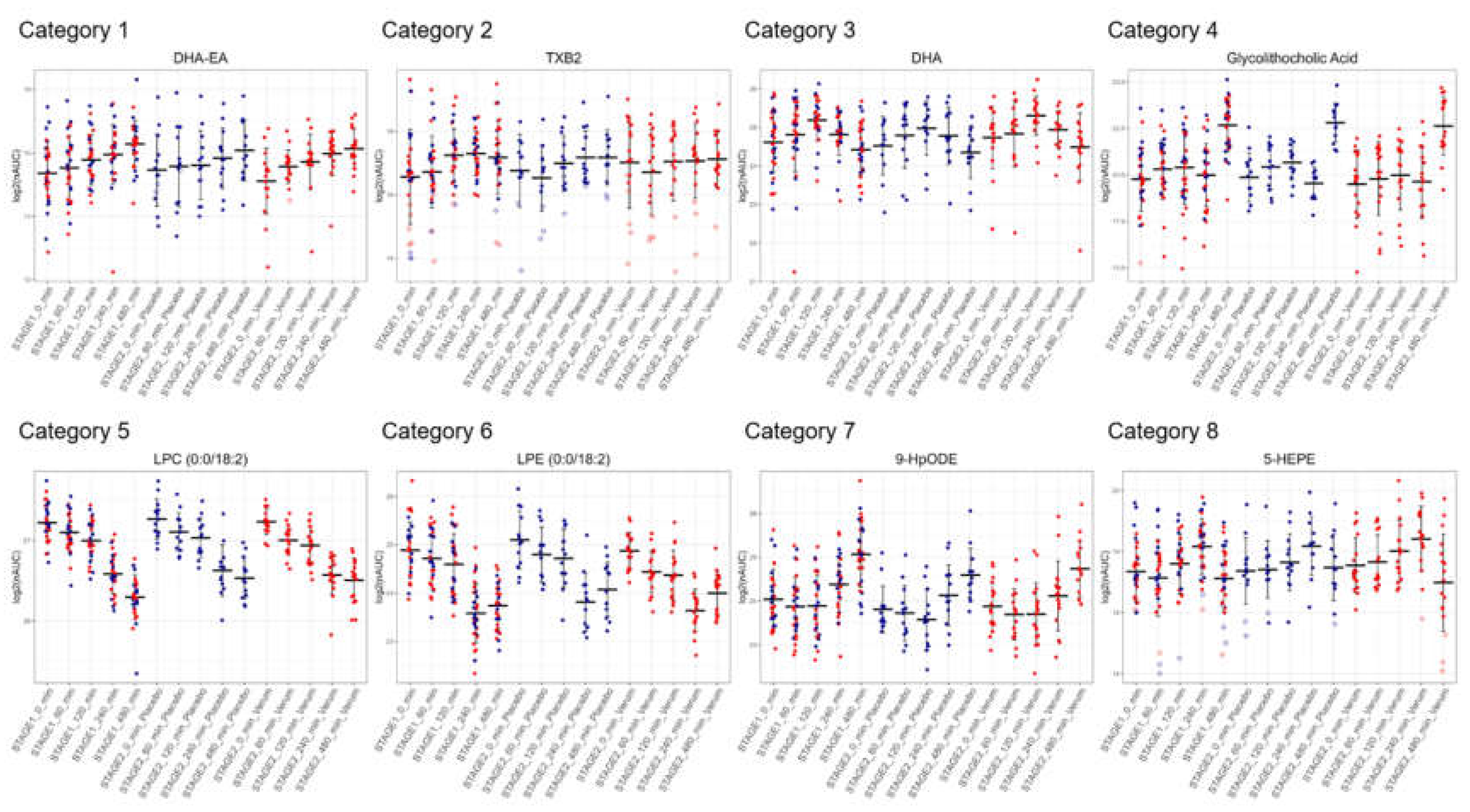

Figure 5.

The antioxidant intervention affected the levels of several lipid mediators. A, volcano plots depicting differences between the verum group and the placebo group. Lysolipids are marked in red. B, detailed depiction of the individual measurement results of selected lipid mediators at stage 1 and stage 2, analyte levels of the verum group marked in red, analyte levels of the placebo group marked in blue.

Figure 5.

The antioxidant intervention affected the levels of several lipid mediators. A, volcano plots depicting differences between the verum group and the placebo group. Lysolipids are marked in red. B, detailed depiction of the individual measurement results of selected lipid mediators at stage 1 and stage 2, analyte levels of the verum group marked in red, analyte levels of the placebo group marked in blue.

3.5. Similar Kinetics After LPS Challenge Suggests Common Biosynthetic Pathways

The stable time-courses observed for most oxylipins allowed us to define eight distinct groups displaying specific kinetic features upon LPS challenge: 1) continuously upregulated (n=3); 2) continuously upregulated, then partially down (n=18); 3) first upregulated, then down below baseline levels (n=23); 4) upregulated, down and up again (n=1); 5) continuously downregulated (n=10); 6) continuously downregulated then partially up (n=24); 7) first downregulated, then up above baseline levels (n= 9); 8) downregulated, up and down again (n=35).

Figure 6 displays representative examples of each category. These groups were found to be populated by molecules sharing a common precursor or a common enzyme responsible for their synthesis (

Supplementary Table S9), thus potentially representing functional categories. Category 1 contained the endocannabinoid docosahexaenoyl ethanolamide (DHA-EA) and other ethanolamides. Category 2 contained mainly oxylipins described to be formed by platelets. Mainly polyunsaturated fatty acids were found in category 3. Category 5 contained many lysophosphatidylcholines, whereas category 6 mainly contained lysophosphatidylethanolamines. Some lipoxygenase products from linoleic acid are found in group 7, other lipoxygenase products, several bile acids, and cortisol were found in category 8.

4. Discussion

The presently employed analysis strategy combining proteomics with lipidomics revealed novel and previously unrecognized regulatory events of oxylipins upon LPS challenge. For the initiation of inflammation, we used a unique

in vivo human model, challenging healthy individuals with the PAMP and thus allowing for recording exact time courses.

29 The specificity of proteins with regard to cell types as sources indicated a temporal sequence of cell types as inflammatory players involved: initially, the endothelial and platelet-derived protein von Willebrand factor (VWF) is involved,

49 followed by the predominantly liver-derived acute phase protein SAA1 and the innate immune cell-derived protein S100A9. Subsequently the liver-derived inflammation marker CRP becomes prominent. Lipidomics revealed more significant events upon administration of LPS than proteomics, but corroborated the interpretation with regard to the involved cell types. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, significantly induced two hours after LPS challenge (

Supplementary Table S6), may be released due to phospholipase A

2 activity previously described to be activated in innate immune cells upon inflammatory activation

via sepsis.

50 Trans-fatty acids such as

trans-DHA may indicate the chemical effects of typically endothelium-derived nitrogen oxide.

51,52

Plasma levels of the lysophospholipid sphingosine-1-phosphate are mainly regulated by erythrocytes and platelets.53 Similar to the PUFAs, the downregulation of plasma sphingosine-1-phosphate observed in response to LPS challenge closely mirrors previous findings reported in the context of sepsis.54 The immediate contribution of blood components to the systemic oxylipin response to LPS is also indicated by the upregulation of TxB2, 12-HHTrE and 12-HETE, as these molecules were found previously to be released from activated platelets.45 The deregulated bile acids, inhibitors of the NLRP3 inflammasome,55 observed 4 hours after the challenge, strongly suggested the involvement of the liver in the modulation of inflammatory processes.56

A striking observation was the uniform downregulation of numerous lysophospholipids, most prominently LPE (0:0/18:1), LPE (0:0/18:2), LPC (0:0/18:1) and LPC (0:0/18:2) upon LPS challenge (

Supplementary Table S6). Lysophospholipids are known to be abundant in plasma as a result of the Lands cycle

57, maintaining the generally high turnover of PUFAs within phospholipids.

58-60 Phospholipids with unsaturated fatty acids are essential for the function of endoplasmic reticulum

61 and mitochondria,

62 but vulnerable with regard to inflammation-associated oxidation.

63 The present data thus indicate that inflammation-induced oxidation of phospholipids is almost immediately managed and corrected via the Lands cycle, apparently resulting in the systemic consumption of PUFA-containing plasma lysophospholipids. Remarkably, beside the liver, erythrocytes have also been described to play an active role in the Lands cycle,

64 suggesting that erythrocyte metabolism may be involved in the early response to inflammatory activation in humans. This may also relate to sphingosine-1-phosphate, an important modulator of inflammation

48,59,65 specifically released by platelets and erythrocytes.

66,67 Sphingosine-1-phosphate was demonstrated to be released by erythrocytes upon hypoxia eventually regulating the oxygen supply.

68 Therefore, our results support an early adaptive response by erythrocytes to mitigate tissue hypoxia caused by the inflammation-induced increase in oxygen expenditure.

69

Considering the known functions of the presently observed systemic modulators of inflammation, it is striking that most of them seem to contribute to the resolution of inflammation. While CRP is regarded as pro-inflammatory, it mediates the opsonization of bacteria, immune complexes, and damaged cells, thereby mediating their elimination.70 Similarly, SAA1 may stimulate pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, but also facilitates removal of membrane debris and toxic lipids formed during inflammation.71 Antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties have been attributed to polyunsaturated fatty acids.72 The role of endocannabinoids regulating immune functions has been recognized rather recently.73 To understand the pro- and anti-inflammatory properties and physiological roles of lysophospholipids, their fatty acyl composition, production, transport, and utilization mechanisms must be considered in detail.59 Furthermore, taurocholic acid and glycocholic acid have been described to inhibit inflammation.74

It is important to note that the most potent inflammation-promoting factors, such as cytokines and prostaglandins, were not detected in the present study. This may be not surprising as these pro-inflammatory factors are not formed by innate immune cells such as neutrophils in blood, but rather in the interstitium,75 they act rather locally there,76 they are short-lived77 and are detectable only at very low concentration levels.78 In contrast, the modulation and resolution of potentially damaging inflammatory responses may be mediated by more long-lived molecules accumulating to higher concentration levels, increasing their chance of being positively detected. The present data suggested that the kinetics of formation and degradation of these molecules differ remarkably, making it potentially difficult to obtain significant results in diseased patients with unknown onset of the inflammatory responses. This may also apply to the immune-modulatory effect of the presently applied intervention, which resulted in significant alterations of different molecules at different time points when compared to the placebo group. Without matching the time points presently obtained due to the artificially induced onset of inflammation, no significant effects would have been observed.

This may also explain why only few studies exist regarding the deregulation of plasma levels of oxylipins and other inflammatory modulators in humans. Many researchers may have observed that the measurements would not be sufficiently robust and precise to support meaningful conclusions. This study demonstrated the successful measurement of these molecules in plasma from human individuals, revealing complex regulatory patterns and time courses after a defined challenge. This may indeed have resulted from the exact initiation of inflammatory signaling, a specific feature of this study. The kinetics observed after LPS challenge were highly reproducible and characteristic for each molecule (

Figure 6). As groups of molecules with common precursors or synthesizing enzymes showed rather similar kinetics, they will serve to learn more about inflammatory regulatory mechanisms and the responsible physiological processes. The combination of proteomics and lipidomics allowed us to match the kinetics of formation and mutually confirm the specific sources of proteins and lipids.

A modulation of marker proteins for inflammatory processes by antioxidant supplementation was actually not observed. This is in line with previous investigations

79 and may suggest that the initiation of the corresponding inflammatory processes was not significantly affected by antioxidants. However, we have observed some oxylipins specifically affected by such intervention (

Figure 5). The increase of 20-HEPE and 22-HDoHE in plasma upon supplementation with -3 fatty acids has already been observed previously and confirm the present data.

80 However, at that time, no inflammatory challenge had been investigated. Here, we also described the downregulation of sphingosine-1-phosphate, a potent pro-inflammatory mediator, by the antioxidative intervention. It is plausible to assume that the metabolism of inflammatory mediators may be affected by antioxidants and may thus account for the clinical observations.

15,32,81 Thus, sphingosine-1-phosphate and the anti-inflammatory oxylipins presently affected by antioxidative supplementation represent plausible candidates potentially mediating such effects. However, the present data do not yet prove such a hypothesis. Future studies will be required to deconvolute all the synthesis, uptake, degradation, and transport processes accounting for the extraordinarily complex regulatory system of inflammation involving proteins and lipids.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1: Composition of the Food Supplement Vitamac; Supplementary Table S2: List and concentrations of internal oxylipin standards; Supplementary Table S3: Inclusion list covering 33 m/z values specific for well-known oxylipins and precursor molecules; Supplementary Table S4: Degree of identification of oxylipins identified in plasma samples; Supplementary Table S5: Comparison of the time points 60 min, 120 min, 240 min and 480 min upon LPS challenge vs. baseline (BL) regarding proteins at stage 1. The log2-transformed label-free quantification (LFQ) intensities are listed for each sample of stage 1 and stage 2.; Supplementary Table S6: Log2-transformed normalized area under the curve (nAUC) lipid values of each sample of stage 1 and stage 2.; Supplementary Table S7: Comparison of the time points 60 min, 120 min, 240 min and 480 min upon LPS challenge vs. baseline (BL) regarding lipids at stage 1.; Supplementary Table S8: Comparison of the time points 60 min, 120 min, 240 min and 480 min upon LPS challenge vs. baseline (BL) regarding lipids at stage 2.; Supplementary Table S9: Lipid members of the eight observed kinetic categories.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Core Facility of Mass Spectrometry at the Faculty of Chemistry and the Joint Metabolome Facility, both members of the Vienna Life-Science Instruments (VLSI).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Slany, A., Bileck, A., Kreutz, D., Mayer, R.L., Muqaku, B., and Gerner, C. (2016). Contribution of Human Fibroblasts and Endothelial Cells to the Hallmarks of Inflammation as Determined by Proteome Profiling. Mol Cell Proteomics 15, 1982-1997. [CrossRef]

- Bennike, T.B. (2023). Advances in proteomics: characterization of the innate immune system after birth and during inflammation. Front Immunol 14, 1254948. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C. , Wang, K., Yang, L., Liu, R., Chu, Y., Qin, X., Yang, P., and Yu, H. (2018). Lipid metabolism in inflammation-related diseases. Analyst 143, 4526-4536. [CrossRef]

- Rimessi, A. , Previati, M., Nigro, F., Wieckowski, M.R., and Pinton, P. (2016). Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and inflammation: Molecular mechanisms, diseases and promising therapies. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 81, 281-293. [CrossRef]

- Ito, F. , Sono, Y., and Ito, T. (2019). Measurement and Clinical Significance of Lipid Peroxidation as a Biomarker of Oxidative Stress: Oxidative Stress in Diabetes, Atherosclerosis, and Chronic Inflammation. Antioxidants (Basel) 8. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.M. (1989). Biochemistry and pharmacology of cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Bull N Y Acad Med 65, 5-15.

- Pergola, C., and Werz, O. (2010). 5-Lipoxygenase inhibitors: a review of recent developments and patents. Expert Opin Ther Pat 20, 355-375. [CrossRef]

- Back, M. , Yurdagul, A., Jr., Tabas, I., Oorni, K., and Kovanen, P.T. (2019). Inflammation and its resolution in atherosclerosis: mediators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cardiol 16, 389-406. [CrossRef]

- Chiurchiu, V. , Leuti, A., and Maccarrone, M. (2018). Bioactive Lipids and Chronic Inflammation: Managing the Fire Within. Front Immunol 9, 38. [CrossRef]

- Yeung, Y.T. , Aziz, F., Guerrero-Castilla, A., and Arguelles, S. (2018). Signaling Pathways in Inflammation and Anti-inflammatory Therapies. Curr Pharm Des 24, 1449-1484. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.P. , and Carmody, R.J. (2018). NF-kappaB and the Transcriptional Control of Inflammation. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 335, 41-84. [CrossRef]

- Gadina, M. , Hilton, D., Johnston, J.A., Morinobu, A., Lighvani, A., Zhou, Y.J., Visconti, R., and O'Shea, J.J. (2001). Signaling by type I and II cytokine receptors: ten years after. Curr Opin Immunol 13, 363-373. [CrossRef]

- DiDonato, J.A. , Mercurio, F., and Karin, M. (2012). NF-kappaB and the link between inflammation and cancer. Immunol Rev 246, 379-400. [CrossRef]

- Jarczak, D. , and Nierhaus, A. (2022). Cytokine Storm-Definition, Causes, and Implications. Int J Mol Sci 23. [CrossRef]

- Dennis, E.A., and Norris, P.C. (2015). Eicosanoid storm in infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 15, 511-523. [CrossRef]

- Calabro, P., Golia, E., and Yeh, E.T. (2009). CRP and the risk of atherosclerotic events. Semin Immunopathol 31, 79-94. [CrossRef]

- Maile, R. , Willis, M.L., Herring, L.E., Prevatte, A., Mahung, C., Cairns, B., Wallet, S., and Coleman, L.G., Jr. (2021). Burn Injury Induces Proinflammatory Plasma Extracellular Vesicles That Associate with Length of Hospital Stay in Women: CRP and SAA1 as Potential Prognostic Indicators. Int J Mol Sci 22. [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, M., Van Hoovels, L., Benucci, M., De Luca, R., Coccia, C., Bernardini, P., Russo, E., Amedei, A., Guiducci, S., Grossi, V., et al. (2023). Circulating Calprotectin (cCLP) in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev 22, 103295. [CrossRef]

- Trinder, M., Boyd, J.H., and Brunham, L.R. (2019). Molecular regulation of plasma lipid levels during systemic inflammation and sepsis. Curr Opin Lipidol 30, 108-116. [CrossRef]

- Menzel, A. , Samouda, H., Dohet, F., Loap, S., Ellulu, M.S., and Bohn, T. (2021). Common and Novel Markers for Measuring Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Ex Vivo in Research and Clinical Practice-Which to Use Regarding Disease Outcomes? Antioxidants (Basel) 10. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J. , Kell, D.B., and Pretorius, E. (2022). The Role of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Cell Signalling in Chronic Inflammation. Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks) 6, 24705470221076390. [CrossRef]

- Misheva, M. , Johnson, J., and McCullagh, J. (2022). Role of Oxylipins in the Inflammatory-Related Diseases NAFLD, Obesity, and Type 2 Diabetes. Metabolites 12. [CrossRef]

- Kovarik, J.J. , Bileck, A., Hagn, G., Meier-Menches, S.M., Frey, T., Kaempf, A., Hollenstein, M., Shoumariyeh, T., Skos, L., Reiter, B., et al. (2023). A multi-omics based anti-inflammatory immune signature characterizes long COVID-19 syndrome. iScience 26, 105717. [CrossRef]

- Janker, L. , Schuster, D., Bortel, P., Hagn, G., Meier-Menches, S.M., Mohr, T., Mader, J.C., Slany, A., Bileck, A., Brunmair, J., et al. (2023). Multiomics-empowered Deep Phenotyping of Ulcerative Colitis Identifies Biomarker Signatures Reporting Functional Remission States. J Crohns Colitis 17, 1514-1527. [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. (2002). Omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation and autoimmune diseases. J Am Coll Nutr 21, 495-505. [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente, M. , and Victor, V.M. (2000). Anti-oxidants as modulators of immune function. Immunol Cell Biol 78, 49-54. [CrossRef]

- Arulselvan, P., Fard, M.T., Tan, W.S., Gothai, S., Fakurazi, S., Norhaizan, M.E., and Kumar, S.S. (2016). Role of Antioxidants and Natural Products in Inflammation. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 5276130. [CrossRef]

- American Dietetic, A. (2005). Position of the American Dietetic Association: fortification and nutritional supplements. J Am Diet Assoc 105, 1300-1311. [CrossRef]

- Told, R. , Palkovits, S., Schmidl, D., Boltz, A., Gouya, G., Wolzt, M., Napora, K.J., Werkmeister, R.M., Popa-Cherecheanu, A., Garhofer, G., and Schmetterer, L. (2014). Retinal hemodynamic effects of antioxidant supplementation in an endotoxin-induced model of oxidative stress in humans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55, 2220-2227. [CrossRef]

- Jilma-Stohlawetz, P. , Kliegel, T., Kantner-Schlifke, I., Strasser-Marsik, C., Mayr, F.B., and Jilma, B. (2017). Upregulation of cytokine mRNA in circulating leukocytes during human endotoxemia. Eur Cytokine Netw 28, 19-26. [CrossRef]

- Schoergenhofer, C. , Schwameis, M., Gelbenegger, G., Buchtele, N., Thaler, B., Mussbacher, M., Schabbauer, G., Wojta, J., Jilma-Stohlawetz, P., and Jilma, B. (2018). Inhibition of Protease-Activated Receptor (PAR1) Reduces Activation of the Endothelium, Coagulation, Fibrinolysis and Inflammation during Human Endotoxemia. Thromb Haemost 118, 1176-1184. [CrossRef]

- Told, R. , Schmidl, D., Palkovits, S., Boltz, A., Gouya, G., Wolzt, M., Witkowska, K.J., Popa-Cherecheanu, A., Werkmeister, R.M., Garhofer, G., and Schmetterer, L. (2014). Antioxidative capacity of a dietary supplement on retinal hemodynamic function in a human lipopolysaccharide (LPS) model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 56, 403-411. [CrossRef]

- Zougman, A. , Selby, P.J., and Banks, R.E. (2014). Suspension trapping (STrap) sample preparation method for bottom-up proteomics analysis. Proteomics 14, 1006-1000. [CrossRef]

- Cox, J. , and Mann, M. (2008). MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol 26, 1367-1372. [CrossRef]

- Cox, J. , and Mann, M. (2012). 1D and 2D annotation enrichment: a statistical method integrating quantitative proteomics with complementary high-throughput data. BMC Bioinformatics 13 Suppl 16, S12. [CrossRef]

- Fahy, E., Sud, M., Cotter, D., and Subramaniam, S. (2007). LIPID MAPS online tools for lipid research. Nucleic Acids Res 35, W606-612. [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. (2014). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

- Lazar, C. , Burger, T., and Wieczorek, S. (2022). imputeLCMD: A collection of methods for left-censored missing data imputation.

- Ritchie, M.E. , Phipson, B., Wu, D., Hu, Y., Law, C.W., Shi, W., and Smyth, G.K. (2015). limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43, e47. [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, Y., and Benjamini, Y. (1990). More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat Med 9, 811-818. [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. (2016). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag).

- Perez-Riverol, Y. , Csordas, A., Bai, J., Bernal-Llinares, M., Hewapathirana, S., Kundu, D.J., Inuganti, A., Griss, J., Mayer, G., Eisenacher, M., et al. (2019). The PRIDE database and related tools and resources in 2019: improving support for quantification data. Nucleic Acids Res 47, D442-D450. [CrossRef]

- Sud, M. , Fahy, E., Cotter, D., Azam, K., Vadivelu, I., Burant, C., Edison, A., Fiehn, O., Higashi, R., Nair, K.S., et al. (2016). Metabolomics Workbench: An international repository for metabolomics data and metadata, metabolite standards, protocols, tutorials and training, and analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res 44, D463-470. [CrossRef]

- Horvath, B., Hegedus, D., Szapary, L., Marton, Z., Alexy, T., Koltai, K., Czopf, L., Wittmann, I., Juricskay, I., Toth, K., and Kesmarky, G. (2004). Measurement of von Willebrand factor as the marker of endothelial dysfunction in vascular diseases. Exp Clin Cardiol 9, 31-34.

- Hagn, G. , Meier-Menches, S.M., Plessl-Walder, G., Mitra, G., Mohr, T., Preindl, K., Schlatter, A., Schmidl, D., Gerner, C., Garhofer, G., and Bileck, A. (2024). Plasma Instead of Serum Avoids Critical Confounding of Clinical Metabolomics Studies by Platelets. J Proteome Res. [CrossRef]

- Astudillo, A.M. , Balboa, M.A., and Balsinde, J. (2023). Compartmentalized regulation of lipid signaling in oxidative stress and inflammation: Plasmalogens, oxidized lipids and ferroptosis as new paradigms of bioactive lipid research. Prog Lipid Res 89, 101207. [CrossRef]

- Hou, L. , Yang, L., Chang, N., Zhao, X., Zhou, X., Dong, C., Liu, F., Yang, L., and Li, L. (2020). Macrophage Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor 2 Blockade Attenuates Liver Inflammation and Fibrogenesis Triggered by NLRP3 Inflammasome. Front Immunol 11, 1149. [CrossRef]

- Cartier, A. , and Hla, T. (2019). Sphingosine 1-phosphate: Lipid signaling in pathology and therapy. Science 366. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Li, L., Dong, F., Guo, L., Hou, Y., Hu, H., Yan, S., Zhou, X., Liao, L., Allen, T.D., and Liu, J.U. (2015). Plasma von Willebrand factor level is transiently elevated in a rat model of acute myocardial infarction. Exp Ther Med 10, 1743-1749. [CrossRef]

- Levy, R., Dana, R., Hazan, I., Levy, I., Weber, G., Smoliakov, R., Pesach, I., Riesenberg, K., and Schlaeffer, F. (2000). Elevated cytosolic phospholipase A(2) expression and activity in human neutrophils during sepsis. Blood 95, 660-665.

- Leitner, G.C. , Hagn, G., Niederstaetter, L., Bileck, A., Plessl-Walder, K., Horvath, M., Kolovratova, V., Tanzmann, A., Tolios, A., Rabitsch, W., et al. (2022). INTERCEPT Pathogen Reduction in Platelet Concentrates, in Contrast to Gamma Irradiation, Induces the Formation of trans-Arachidonic Acids and Affects Eicosanoid Release during Storage. Biomolecules 12. [CrossRef]

- Tousoulis, D. , Kampoli, A.M., Tentolouris, C., Papageorgiou, N., and Stefanadis, C. (2012). The role of nitric oxide on endothelial function. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 10, 4-18. [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.M. , Ishizu, A.N., Foo, J.C., Toh, X.R., Zhang, F., Whee, D.M., Torta, F., Cazenave-Gassiot, A., Matsumura, T., Kim, S., et al. (2017). Mfsd2b is essential for the sphingosine-1-phosphate export in erythrocytes and platelets. Nature 550, 524-528. [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.S. , Nierhaus, A., Holzmann, M., Mudersbach, E., Bauer, A., Robbe, L., Zahrte, C., Geffken, M., Peine, S., Schwedhelm, E., et al. (2015). Decreased serum concentrations of sphingosine-1-phosphate in sepsis. Crit Care 19, 372. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C., Xie, S., Chi, Z., Zhang, J., Liu, Y., Zhang, L., Zheng, M., Zhang, X., Xia, D., Ke, Y., et al. (2016). Bile Acids Control Inflammation and Metabolic Disorder through Inhibition of NLRP3 Inflammasome. Immunity 45, 802-816. [CrossRef]

- Calzadilla, N., Comiskey, S.M., Dudeja, P.K., Saksena, S., Gill, R.K., and Alrefai, W.A. (2022). Bile acids as inflammatory mediators and modulators of intestinal permeability. Front Immunol 13, 1021924. [CrossRef]

- O'Donnell, V.B. (2022). New appreciation for an old pathway: the Lands Cycle moves into new arenas in health and disease. Biochem Soc Trans 50, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Niederstaetter, L. , Neuditschko, B., Brunmair, J., Janker, L., Bileck, A., Del Favero, G., and Gerner, C. (2021). Eicosanoid Content in Fetal Calf Serum Accounts for Reproducibility Challenges in Cell Culture. Biomolecules 11. [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.T., Ramesh, T., Toh, X.R., and Nguyen, L.N. (2020). Emerging roles of lysophospholipids in health and disease. Prog Lipid Res 80, 101068. [CrossRef]

- Block, R.C., Duff, R., Lawrence, P., Kakinami, L., Brenna, J.T., Shearer, G.C., Meednu, N., Mousa, S., Friedman, A., Harris, W.S., et al. (2010). The effects of EPA, DHA, and aspirin ingestion on plasma lysophospholipids and autotaxin. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 82, 87-95. [CrossRef]

- Lagace, T.A., and Ridgway, N.D. (2013). The role of phospholipids in the biological activity and structure of the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833, 2499-2510. [CrossRef]

- Vouilloz, A. , Bourgeois, T., Diedisheim, M., Pilot, T., Jalil, A., Le Guern, N., Bergas, V., Rohmer, N., Castelli, F., Leleu, D., et al. (2025). Impaired unsaturated fatty acid elongation alters mitochondrial function and accelerates metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis progression. Metabolism 162, 156051. [CrossRef]

- Muniz-Santos, R. , Lucieri-Costa, G., de Almeida, M.A.P., Moraes-de-Souza, I., Brito, M., Silva, A.R., and Goncalves-de-Albuquerque, C.F. (2023). Lipid oxidation dysregulation: an emerging player in the pathophysiology of sepsis. Front Immunol 14, 1224335. [CrossRef]

- Chatzinikolaou, P.N. , Margaritelis, N.V., Paschalis, V., Theodorou, A.A., Vrabas, I.S., Kyparos, A., D'Alessandro, A., and Nikolaidis, M.G. (2024). Erythrocyte metabolism. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 240, e14081. [CrossRef]

- Yaginuma, S. , Omi, J., Kano, K., and Aoki, J. (2023). Lysophospholipids and their producing enzymes: Their pathological roles and potential as pathological biomarkers. Pharmacol Ther 246, 108415. [CrossRef]

- Koenen, R.R. (2016). The prowess of platelets in immunity and inflammation. Thromb Haemost 116, 605-612. [CrossRef]

- Tukijan, F. , Chandrakanthan, M., and Nguyen, L.N. (2018). The signalling roles of sphingosine-1-phosphate derived from red blood cells and platelets. Br J Pharmacol 175, 3741-3746. [CrossRef]

- Xie, T. , Chen, C., Peng, Z., Brown, B.C., Reisz, J.A., Xu, P., Zhou, Z., Song, A., Zhang, Y., Bogdanov, M.V., et al. (2020). Erythrocyte Metabolic Reprogramming by Sphingosine 1-Phosphate in Chronic Kidney Disease and Therapies. Circ Res 127, 360-375. [CrossRef]

- Sun, K. , Zhang, Y., D'Alessandro, A., Nemkov, T., Song, A., Wu, H., Liu, H., Adebiyi, M., Huang, A., Wen, Y.E., et al. (2016). Sphingosine-1-phosphate promotes erythrocyte glycolysis and oxygen release for adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia. Nat Commun 7, 12086. [CrossRef]

- Richter, K. , Amati, A.L., Padberg, W., and Grau, V. (2022). Negative regulation of ATP-induced inflammasome activation and cytokine secretion by acute-phase proteins: A mini review. Front Pharmacol 13, 981276. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. , Chen, Q., Zheng, J., Zeng, Z., Chen, M., Li, L., and Zhang, S. (2023). Serum amyloid protein A in inflammatory bowel disease: from bench to bedside. Cell Death Discov 9, 154. [CrossRef]

- Oppedisano, F. , Macri, R., Gliozzi, M., Musolino, V., Carresi, C., Maiuolo, J., Bosco, F., Nucera, S., Caterina Zito, M., Guarnieri, L., et al. (2020). The Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of n-3 PUFAs: Their Role in Cardiovascular Protection. Biomedicines 8. [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, O., and Ganguly, D. (2021). Endocannabinoids in immune regulation and immunopathologies. Immunology 164, 242-252. [CrossRef]

- Ge, X. , Huang, S., Ren, C., and Zhao, L. (2023). Taurocholic Acid and Glycocholic Acid Inhibit Inflammation and Activate Farnesoid X Receptor Expression in LPS-Stimulated Zebrafish and Macrophages. Molecules 28. [CrossRef]

- Mihlan, M. , Glaser, K.M., Epple, M.W., and Lammermann, T. (2022). Neutrophils: Amoeboid Migration and Swarming Dynamics in Tissues. Front Cell Dev Biol 10, 871789. [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.A. , Peskar, B.A., and Sinzinger, H. (2004). Defects in the prostaglandin system--what is known? Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 71, 347-350. [CrossRef]

- Biringer, R.G. (2020). The enzymology of human eicosanoid pathways: the lipoxygenase branches. Mol Biol Rep 47, 7189-7207. [CrossRef]

- Sorgi, C.A. , Peti, A.P.F., Petta, T., Meirelles, A.F.G., Fontanari, C., Moraes, L.A.B., and Faccioli, L.H. (2018). Comprehensive high-resolution multiple-reaction monitoring mass spectrometry for targeted eicosanoid assays. Sci Data 5, 180167. [CrossRef]

- Taherkhani, S. , Suzuki, K., and Castell, L. (2020). A Short Overview of Changes in Inflammatory Cytokines and Oxidative Stress in Response to Physical Activity and Antioxidant Supplementation. Antioxidants (Basel) 9. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, R. , Konkel, A., Mehling, H., Blossey, K., Gapelyuk, A., Wessel, N., von Schacky, C., Dechend, R., Muller, D.N., Rothe, M., et al. (2014). Dietary omega-3 fatty acids modulate the eicosanoid profile in man primarily via the CYP-epoxygenase pathway. J Lipid Res 55, 1150-1164. [CrossRef]

- Sheppe, A.E.F., and Edelmann, M.J. (2021). Roles of Eicosanoids in Regulating Inflammation and Neutrophil Migration as an Innate Host Response to Bacterial Infections. Infect Immun 89, e0009521. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).