Submitted:

17 October 2023

Posted:

18 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

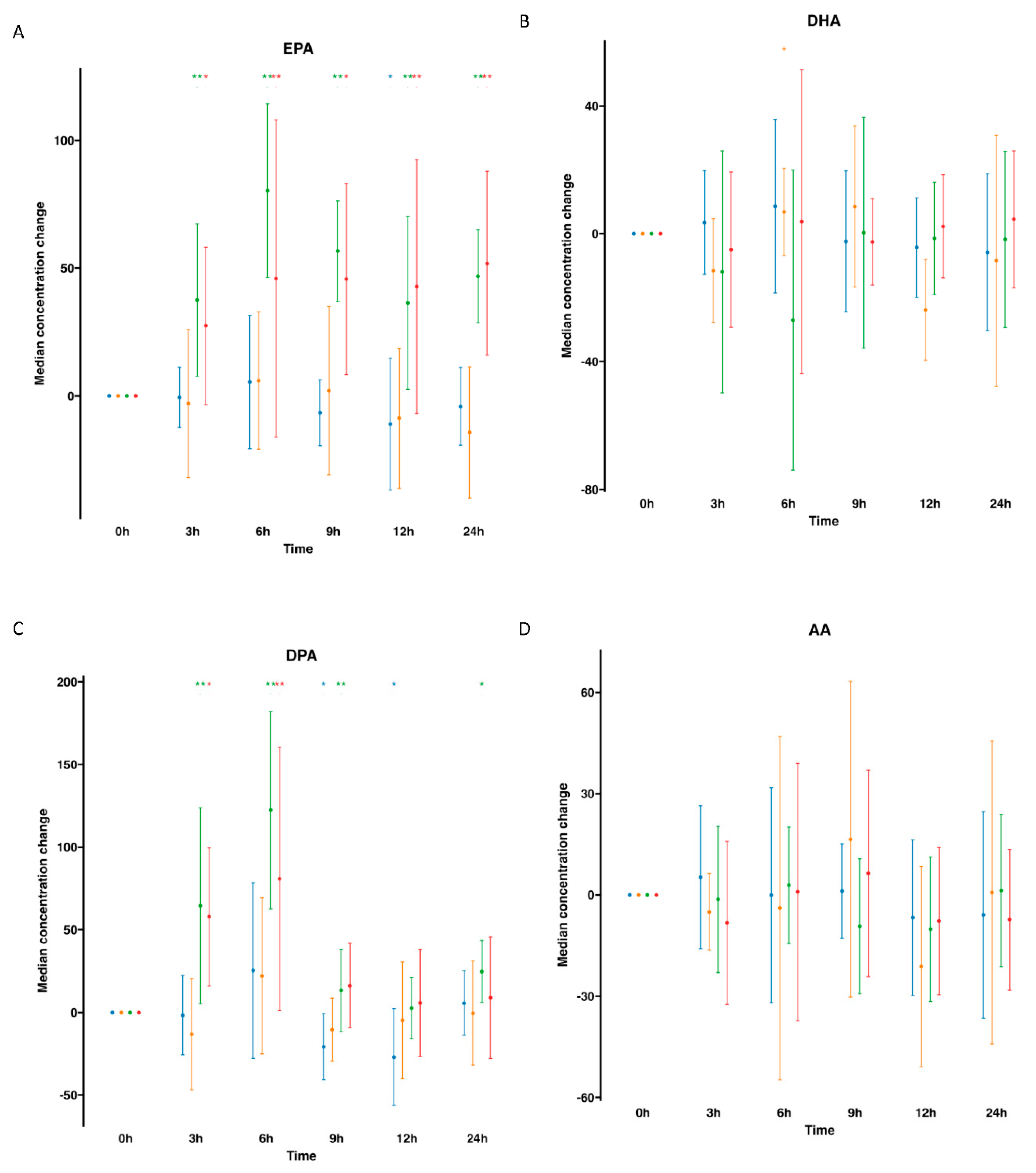

), supplemented plasma (

), supplemented plasma ( ), control serum (

), control serum ( ) and supplemented serum (

) and supplemented serum ( ). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

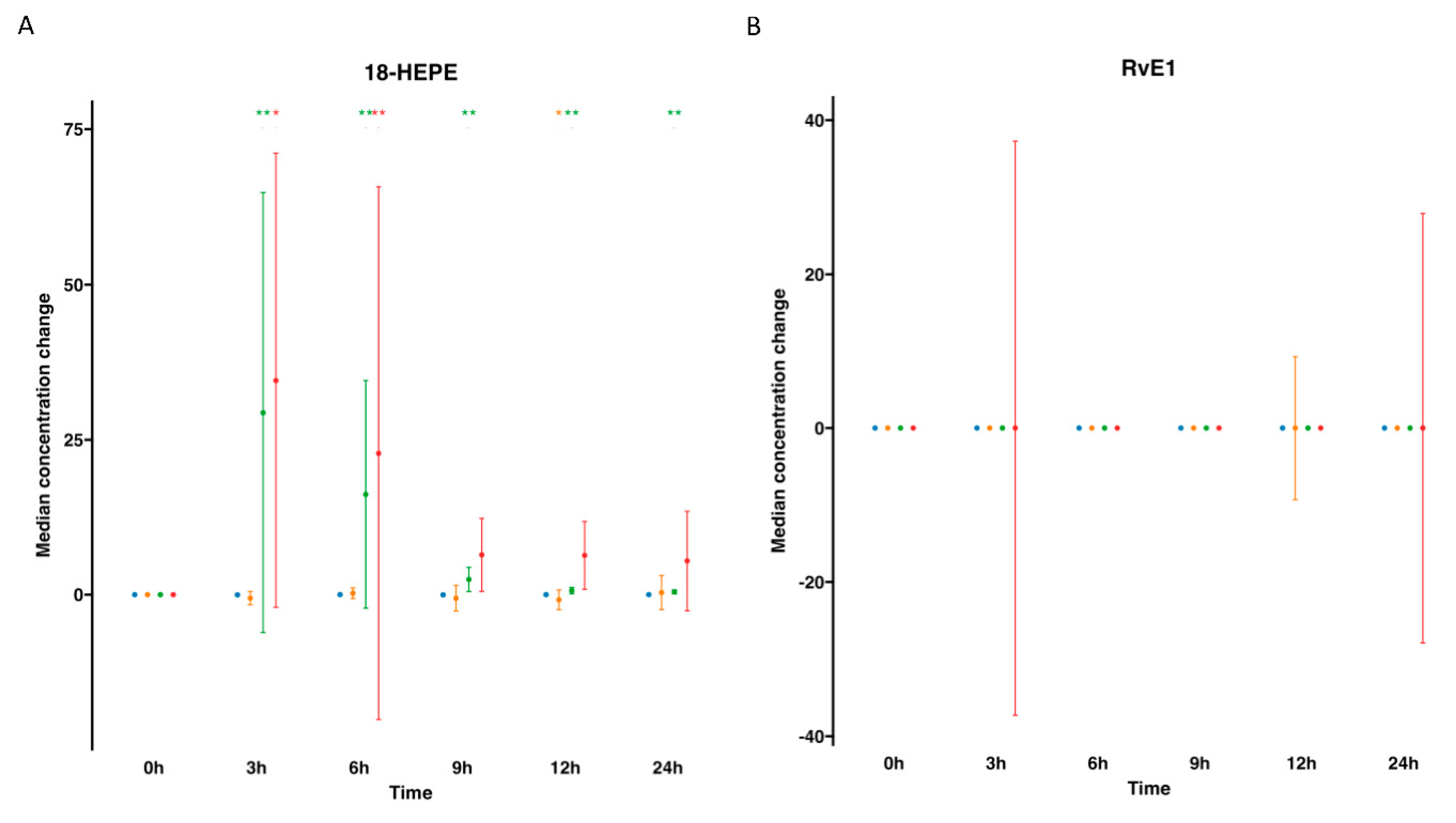

), supplemented plasma (

), supplemented plasma ( ), control serum (

), control serum ( ) and supplemented serum (

) and supplemented serum ( ). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

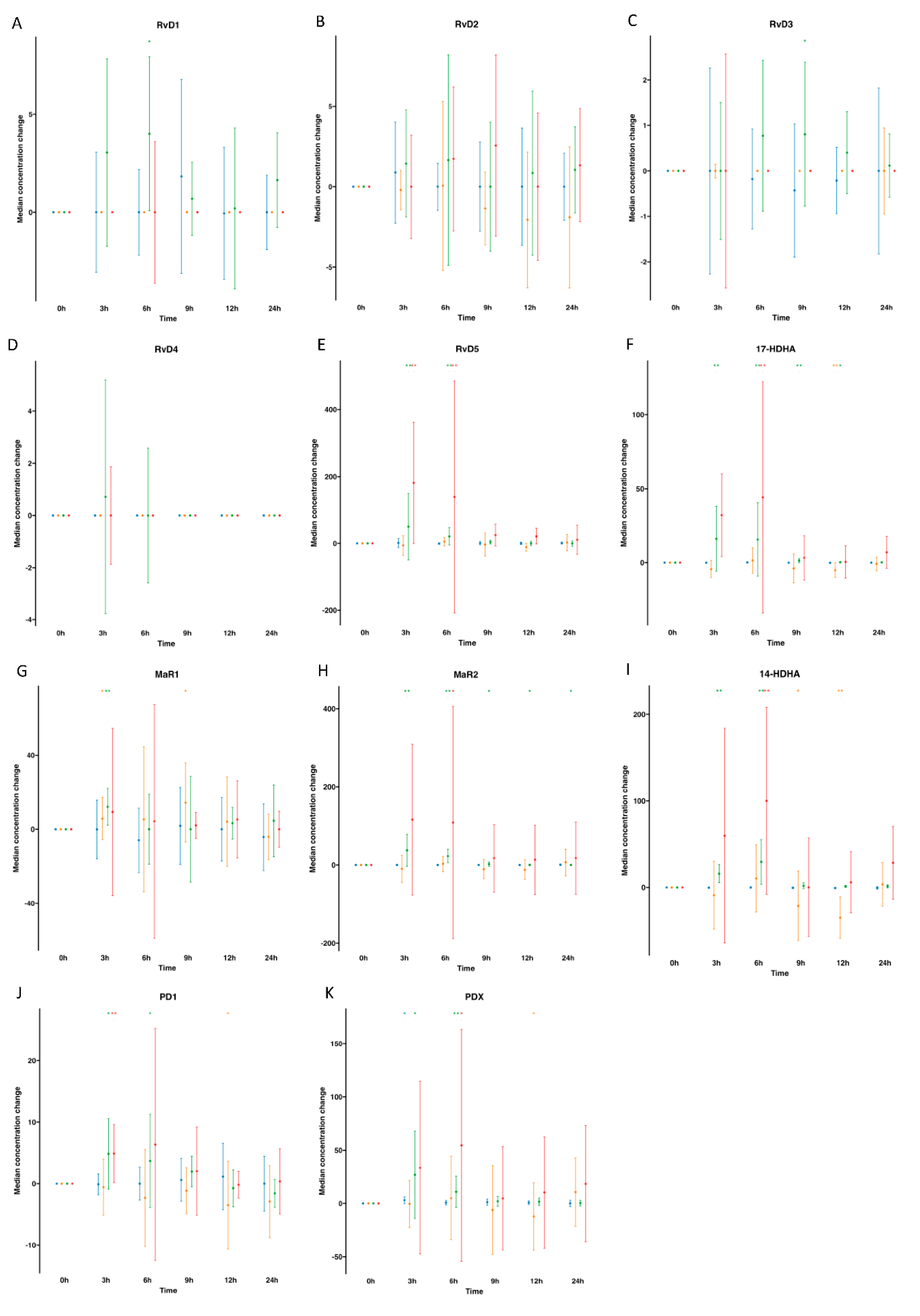

), supplemented plasma (

), supplemented plasma ( ), control serum (

), control serum ( ) and supplemented serum (

) and supplemented serum ( ). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

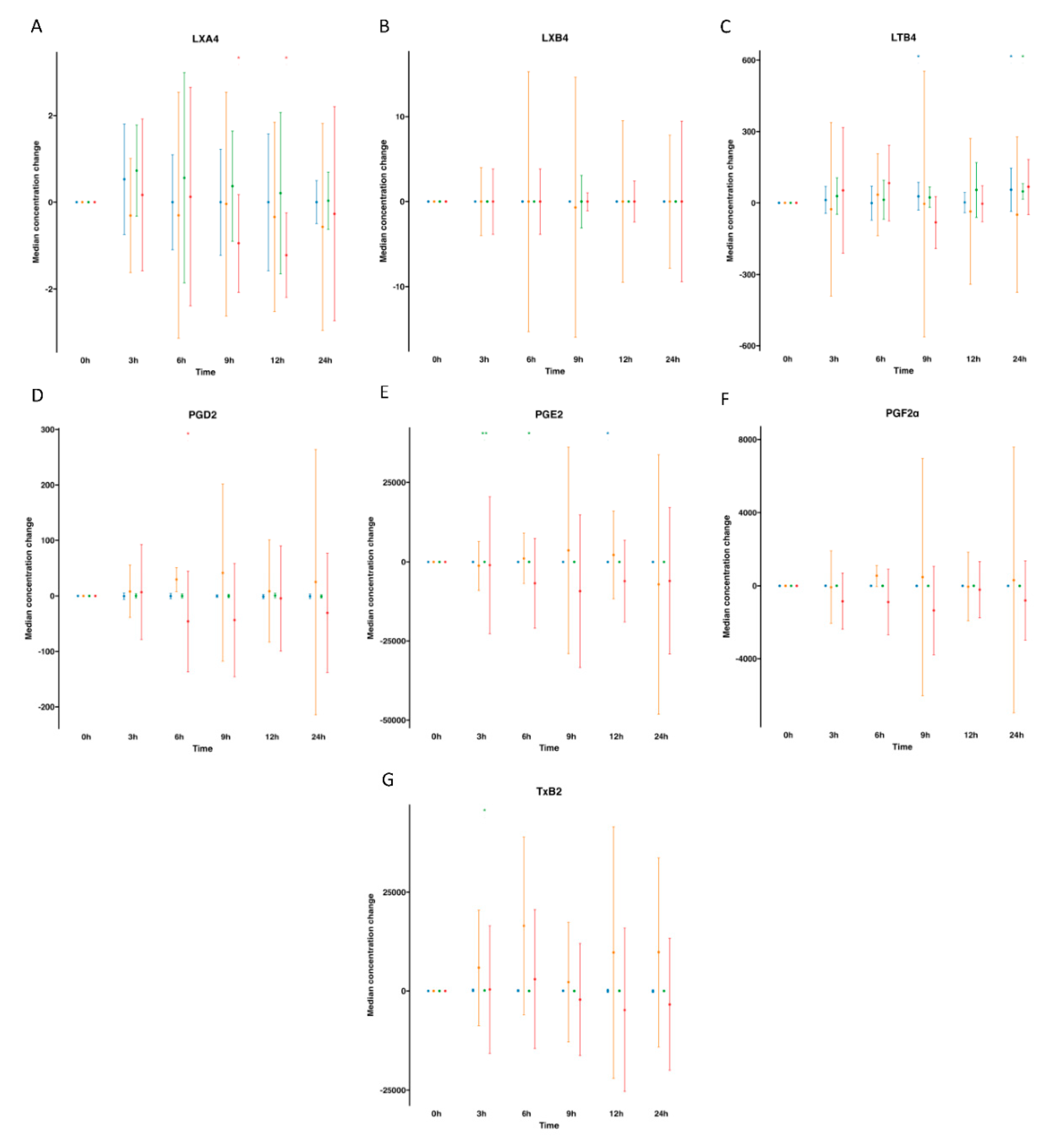

), supplemented plasma (

), supplemented plasma ( ), control serum (

), control serum ( ) and supplemented serum (

) and supplemented serum ( ). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

), supplemented plasma (

), supplemented plasma ( ), control serum (

), control serum ( ) and supplemented serum (

) and supplemented serum ( ). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

), supplemented plasma (

), supplemented plasma ( ), control serum (

), control serum ( ) and supplemented serum (

) and supplemented serum ( ). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

), supplemented plasma (

), supplemented plasma ( ), control serum (

), control serum ( ) and supplemented serum (

) and supplemented serum ( ). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

), supplemented plasma (

), supplemented plasma ( ), control serum (

), control serum ( ) and supplemented serum (

) and supplemented serum ( ). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

). Statistical significance for the time effect was determined by Wilcoxon Signed Rank test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01).

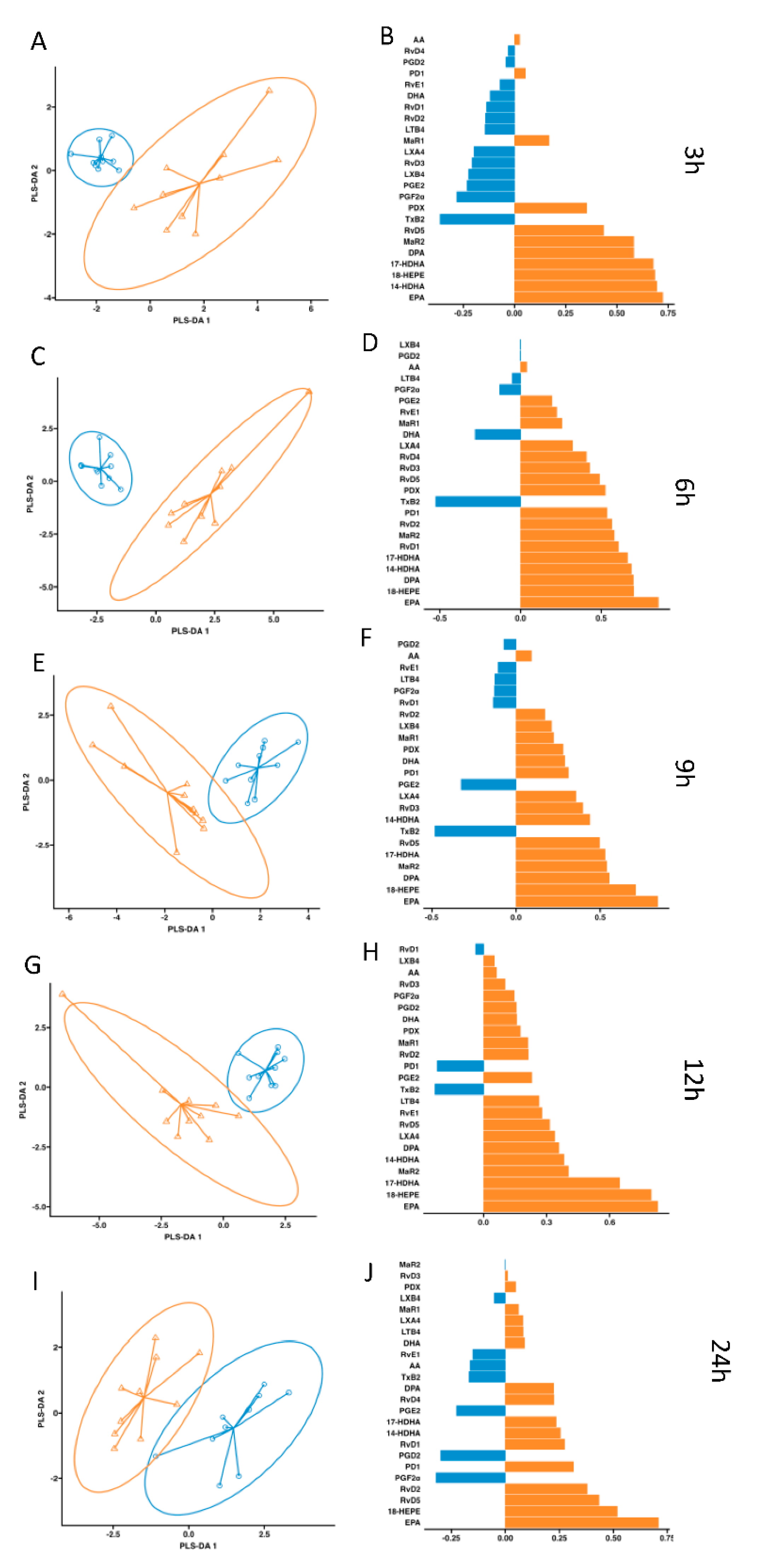

, control;

, control;  , supplemented). Right panel plots display the lipid mediator variable importance from component 1, colours indicate the group in which the median is maximum for each analyte (

, supplemented). Right panel plots display the lipid mediator variable importance from component 1, colours indicate the group in which the median is maximum for each analyte ( , control;

, control;  , supplemented).

, supplemented).

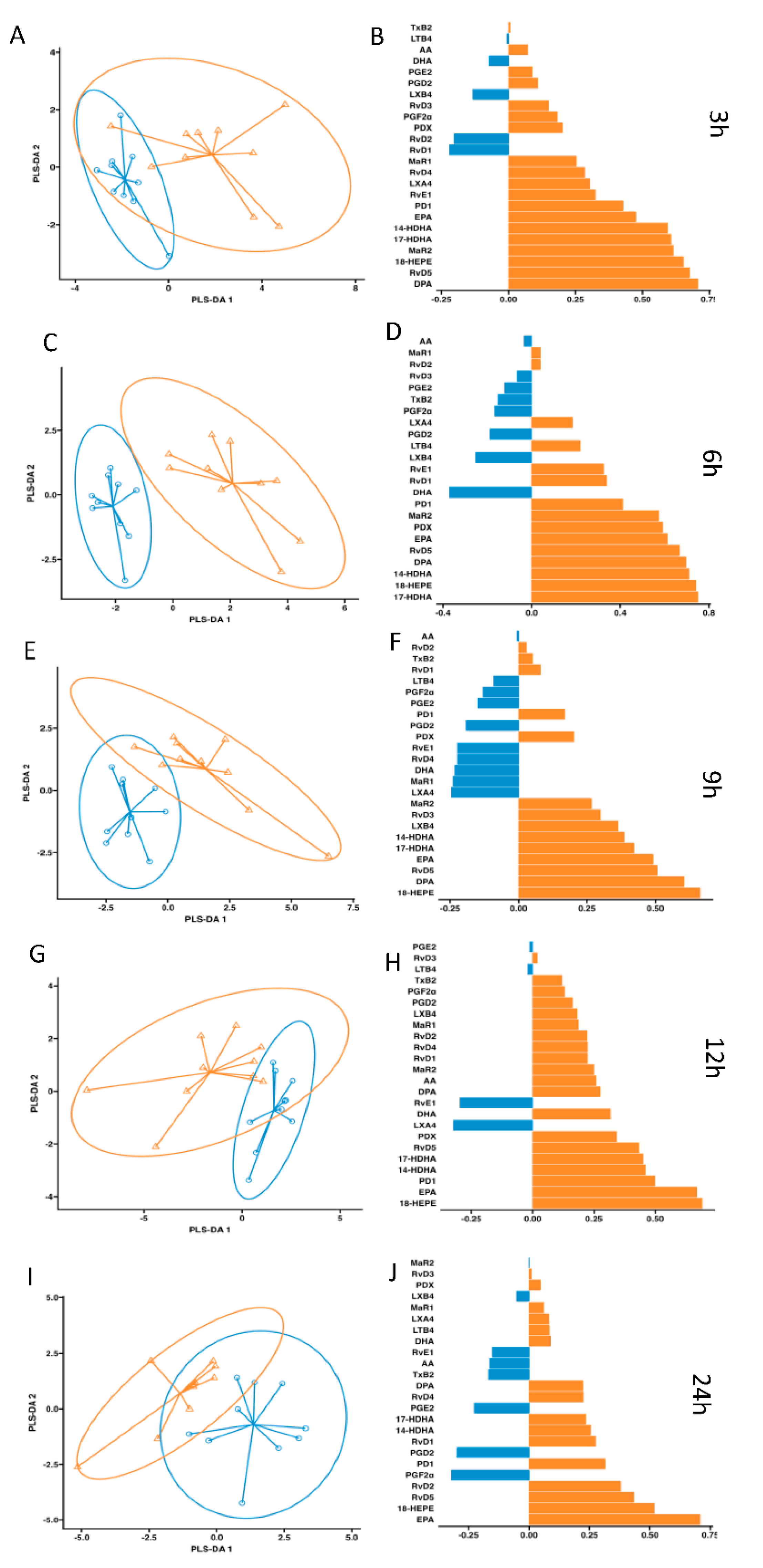

, control;

, control;  , supplemented). Right panel plots display the lipid mediator variable importance from component 1, colours indicate the group in which the median is maximum for each analyte (

, supplemented). Right panel plots display the lipid mediator variable importance from component 1, colours indicate the group in which the median is maximum for each analyte ( , control;

, control;  , supplemented).

, supplemented).

, control;

, control;  , supplemented). Right panel plots display the lipid mediator variable importance from component 1 (right panel).

, supplemented). Right panel plots display the lipid mediator variable importance from component 1 (right panel).

, control;

, control;  , supplemented). Right panel plots display the lipid mediator variable importance from component 1 (right panel).

, supplemented). Right panel plots display the lipid mediator variable importance from component 1 (right panel).

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Study participants

Study Design

Safety analysis.

Biological samples processing.

Lipid mediator extraction and profiling (LC-MS/MS)

Targeted LC-MS/MS Acquisition Parameters

Pharmacokinetic and statistical analyses

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bang, H.O.; Dyerberg, J.; Nielsen, A.B. o. ndu. PLASMA LIPID AND LIPOPROTEIN PATTERN IN GREENLANDIC WEST-COAST ESKIMOS. Lancet 1971, 1, 1143–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppedisano, F.; Mollace, R.; Tavernese, A.; Gliozzi, M.; Musolino, V.; Macrì, R.; Carresi, C.; Maiuolo, J.; Serra, M.; Cardamone, A.; et al. PUFA Supplementation and Heart Failure: Effects on Fibrosis and Cardiac Remodeling. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Tokgozoglu, L.; Parhofer, K.G.; Handelsman, Y.; Leiter, L.A.; Landmesser, U.; Brinton, E.A.; Catapano, A.L. Icosapent Ethyl for Reduction of Persistent Cardiovascular Risk: A Critical Review of Major Medical Society Guidelines and Statements. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2022, 20, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N. Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators Are Leads for Resolution Physiology. Nature 2014, 510, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Clish, C.B.; Brannon, J.; Colgan, S.P.; Chiang, N.; Gronert, K. Novel Functional Sets of Lipid-Derived Mediators with Antiinflammatory Actions Generated from Omega-3 Fatty Acids via Cyclooxygenase 2–Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs and Transcellular Processing. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Hong, S.; Gronert, K.; Colgan, S.P.; Devchand, P.R.; Mirick, G.; Moussignac, R.-L. Resolvins: A Family of Bioactive Products of Omega-3 Fatty Acid Transformation Circuits Initiated by Aspirin Treatment That Counter Proinflammation Signals. J. Exp. Med. 2002, 196, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Gronert, K.; Devchand, P.R.; Moussignac, R.L.; Serhan, C.N. Novel Docosatrienes and 17S-Resolvins Generated from Docosahexaenoic Acid in Murine Brain, Human Blood, and Glial Cells: Autacoids in Anti-Inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 14677–14687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannenberg GL, Chiang N, Ariel A, Arita M, Tjonahen E, Gotlinger KH, Hong S, S. C. Molecular Circuits of Resolution: Formation and Actions of Resolvins and Protectins. J Immunol 2005, 174, 4345–4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, N.; Serhan, C.N. Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediator Network: An Update on Production and Actions. Essays Biochem. 2020, 64, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arita, M.; Bianchini, F.; Aliberti, J.; Sher, A.; Chiang, N.; Hong, S.; Yang, R.; Petasis, N.A.; Serhan, C.N. Stereochemical Assignment, Antiinflammatory Properties, and Receptor for the Omega-3 Lipid Mediator Resolvin E1. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 201, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; Gotlinger, K.; Hong, S.; Lu, Y.; Siegelman, J.; Baer, T.; Yang, R.; Colgan, S.P.; Petasis, N.A. Anti-Inflammatory Actions of Neuroprotectin D1/Protectin D1 and Its Natural Stereoisomers: Assignments of Dihydroxy-Containing Docosatrienes 1. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 1848–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.-P.; Oh, S.F.; Uddin, J.; Yang, R.; Gotlinger, K.; Campbell, E.; Colgan, S.P.; Petasis, N.A.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvin D1 and Its Aspirin-Triggered 17R Epimer. Stereochemical Assignments, Anti-Inflammatory Properties, and Enzymatic Inactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 9323–9334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, N.; Dalli, J.; Colas, R.A.; Serhan, C.N. Identification of Resolvin D2 Receptor Mediating Resolution of Infections and Organ Protection. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, N.; de la Rosa, X.; Libreros, S.; Serhan, C.N. Novel Resolvin D2 Receptor Axis in Infectious Inflammation. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, N.; Libreros, S.; Norris, P.C.; De La Rosa, X.; Serhan, C.N. Maresin 1 Activates LGR6 Receptor Promoting Phagocyte Immunoresolvent Functions. J. Clin. Invest. 2019, 129, 5294–5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norling, L. V.; Headland, S.E.; Dalli, J.; Arnardottir, H.H.; Haworth, O.; Jones, H.R.; Irimia, D.; Serhan, C.N.; Perretti, M. Proresolving and Cartilage-Protective Actions of Resolvin D1 in Inflammatory Arthritis. JCI insight 2016, 1, e85922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredman, G.; Spite, M. Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators in Cardiovascular Diseases. Mol. Aspects Med. 2017, 58, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredman, G. Resolving Atherosclerosis and Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019 165 2019, 16, 259–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Chiang, N.; Dalli, J. New Pro-Resolving n-3 Mediators Bridge Resolution of Infectious Inflammation to Tissue Regeneration. Mol. Aspects Med. 2018, 64, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rosa, X.; Norris, P.C.; Chiang, N.; Rodriguez, A.R.; Spur, B.W.; Serhan, C.N. Identification and Complete Stereochemical Assignments of the New Resolvin Conjugates in Tissue Regeneration in Human Tissues That Stimulate Proresolving Phagocyte Functions and Tissue Regeneration. Am. J. Pathol. 2018, 188, 950–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, M.; Hjorth, E.; Cortés-Toro, V.; Eyjolfsdottir, H.; Graff, C.; Nennesmo, I.; Palmblad, J.; Eriksdotter, M.; Sambamurti, K.; et al. Resolution of Inflammation Is Altered in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015, 11, e1–e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Wang, X.; Hjorth, E.; Colas, R.A.; Schroeder, L.; Granholm, A.C.; Serhan, C.N.; Schultzberg, M. Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators Improve Neuronal Survival and Increase Aβ42 Phagocytosis. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 2733–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serhan, C.N.; de la Rosa, X.; Jouvene, C.C. Cutting Edge: Human Vagus Produces Specialized Proresolving Mediators of Inflammation with Electrical Stimulation Reducing Proinflammatory Eicosanoids. J. Immunol. 2018, 201, 3161–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colas, R.A.; Shinohara, M.; Dalli, J.; Chiang, N.; Serhan, C.N. Identification and Signature Profiles for Pro-Resolving and Inflammatory Lipid Mediators in Human Tissue. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2014, 307, C39–C54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, B.; Xu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Yang, S.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, D. Characterization of Goose SPMS: Molecular Characterization and Expression Profiling of SPMS in the Goose Ovary. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 18, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clària, J.; Dalli, J.; Yacoubian, S.; Gao, F.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvin D1 and Resolvin D2 Govern Local Inflammatory Tone in Obese Fat. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 2597–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keelan, J.A.; Mas, E.; D’Vaz, N.; Dunstan, J.A.; Li, S.; Barden, A.E.; Mark, P.J.; Waddell, B.J.; Prescott, S.L.; Mori, T.A. Effects of Maternal N-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation on Placental Cytokines, pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators and Their Precursors. Reproduction 2015, 149, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P.C.; Libreros, S.; Serhan, C.N. Resolution Metabolomes Activated by Hypoxic Environment. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax4895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prüss, H.; Rosche, B.; Sullivan, A.B.; Brommer, B.; Wengert, O.; Gronert, K.; Schwab, J.M. Proresolution Lipid Mediators in Multiple Sclerosis — Differential, Disease Severity-Dependent Synthesis — A Clinical Pilot Trial. PLoS One 2013, 8, e55859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giera, M.; Ioan-Facsinay, A.; Toes, R.; Gao, F.; Dalli, J.; Deelder, A.M.; Serhan, C.N.; Mayboroda, O.A. Lipid and Lipid Mediator Profiling of Human Synovial Fluid in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients by Means of LC-MS/MS. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnardottir, H.; Orr, S.K.; Dalli, J.; Serhan, C.N. Human Milk Proresolving Mediators Stimulate Resolution of Acute Inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2016, 9, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, A.; Fukuda, H.; Shiida, N.; Tanaka, N.; Furugen, A.; Ogura, J.; Shuto, S.; Mano, N.; Yamaguchi, H. Determination of ω-6 and ω-3 PUFA Metabolites in Human Urine Samples Using UPLC/MS/MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 1625–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mas, E.; Croft, K.D.; Zahra, P.; Barden, A.; Mori, T.A. Resolvins D1, D2, and Other Mediators of Self-Limited Resolution of Inflammation in Human Blood Following n-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation. Clin. Chem. 2012, 58, 1476–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, P.R.; Marques, R.M.; Gomez, E.A.; Colas, R.A.; De Matteis, R.; Zak, A.; Patel, M.; Collier, D.J.; Dalli, J. Enriched Marine Oil Supplements Increase Peripheral Blood Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators Concentrations and Reprogram Host Immune Responses: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, J.W.; Libreros, S.; De La Rosa, X.; Sansbury, B.E.; Norris, P.C.; Chiang, N.; Fichtner, D.; Keyes, G.S.; Wourms, N.; Spite, M.; et al. Structural Insights into Resolvin D4 Actions and Further Metabolites via a New Total Organic Synthesis and Validation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2018, 103, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Vicario, C.; Titos, E.; Walker, M.E.; Alcaraz-Quiles, J.; Casulleras, M.; Durán-Güell, M.; Flores-Costa, R.; Pérez-Romero, N.; Forné, M.; Dalli, J.; et al. Leukocytes from Obese Individuals Exhibit an Impaired SPM Signature. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 7072–7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halade, G. V.; Norris, P.C.; Kain, V.; Serhan, C.N.; Ingle, K.A. Splenic Leukocytes Define the Resolution of Inflammation in Heart Failure. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11, eaao1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, J.W.; Orr, S.K.; Dalli, J.; Cheng, C.Y.C.; Sanger, J.M.; Chiang, N.; Petasis, N.A.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvin D4 Stereoassignment and Its Novel Actions in Host Protection and Bacterial Clearance. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, P.C.; Libreros, S.; Chiang, N.; Serhan, C.N. A Cluster of Immunoresolvents Links Coagulation to Innate Host Defense in Human Blood. Sci. Signal. 2017, 10, eaan1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudert, C.A.; Weylandt, K.H.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J.; Hong, S.; Dignass, A.; Serhan, C.N.; Kang, J.X. Transgenic Mice Rich in Endogenous Omega-3 Fatty Acids Are Protected from Colitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 11276–11281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, N.; Shinohara, M.; Dalli, J.; Mirakaj, V.; Kibi, M.; Choi, A.M.K.; Serhan, C.N. Inhaled Carbon Monoxide Accelerates Resolution of Inflammation via Unique Proresolving Mediator-Heme Oxygenase-1 Circuits. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 6378–6388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul-Clark, M.J.; Van Cao, T.; Moradi-Bidhendi, N.; Cooper, D.; Gilroy, D.W. 15-Epi-Lipoxin A4-Mediated Induction of Nitric Oxide Explains How Aspirin Inhibits Acute Inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 200, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claria, J.; Serhan, C.N. Aspirin Triggers Previously Undescribed Bioactive Eicosanoids by Human Endothelial Cell-Leukocyte Interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995, 92, 9475–9479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spite, M.; Norling, L. V.; Summers, L.; Yang, R.; Cooper, D.; Petasis, N.A.; Flower, R.J.; Perretti, M.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvin D2 Is a Potent Regulator of Leukocytes and Controls Microbial Sepsis. Nature 2009, 461, 1287–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Han, S.H.; Park, M.H.; Baek, B.; Song, I.S.; Choi, M.K.; Takuwa, Y.; Ryu, H.; Kim, S.H.; He, X.; et al. Neuronal SphK1 Acetylates COX2 and Contributes to Pathogenesis in a Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birnbaum, Y.; Ye, Y.; Lin, Y.; Freeberg, S.Y.; Huang, M.H.; Perez-Polo, J.R.; Uretsky, B.F. Aspirin Augments 15-Epi-Lipoxin A4 Production by Lipopolysaccharide, but Blocks the Pioglitazone and Atorvastatin Induction of 15-Epi-Lipoxin A4 in the Rat Heart. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007, 83, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalli, J.; Chiang, N.; Serhan, C.N. Elucidation of Novel 13-Series Resolvins That Increase with Atorvastatin and Clear Infections. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1071–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barden, A.; Phillips, M.; Mas, E.; Hill, L.M.; Mowat, I.; Loh, P.S.; Corcoran, T.; Mori, T.A. Effects of Antiemetic Doses of Dexamethasone on Plasma Mediators of Inflammation Resolution and Pain after Surgery in Women. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2020, 149, 106427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozurkewich, E.L.; Greenwood, M.; Clinton, C.; Berman, D.; Romero, V.; Djuric, Z.; Qualls, C.; Gronert, K. Pathway Markers for Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators in Maternal and Umbilical Cord Blood: A Secondary Analysis of the Mothers, Omega-3, and Mental Health Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markworth, J.F.; Vella, L.; Lingard, B.S.; Tull, D.L.; Rupasinghe, T.W.; Sinclair, A.J.; Maddipati, K.R.; Cameron-Smith, D. Human Inflammatory and Resolving Lipid Mediator Responses to Resistance Exercise and Ibuprofen Treatment. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2013, 305, R1281–R1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsden, C.E.; Faurot, K.R.; Zamora, D.; Suchindran, C.M.; Macintosh, B.A.; Gaylord, S.; Ringel, A.; Hibbeln, J.R.; Feldstein, A.E.; Mori, T.A.; et al. Targeted Alteration of Dietary N-3 and n-6 Fatty Acids for the Treatment of Chronic Headaches: A Randomized Trial. Pain 2013, 154, 2441–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalli, J.; Colas, R.A.; Quintana, C.; Barragan-Bradford, D.; Hurwitz, S.; Levy, B.D.; Choi, A.M.; Serhan, C.N.; Baron, R.M. Human Sepsis Eicosanoid and Proresolving Lipid Mediator Temporal Profiles: Correlations With Survival and Clinical Outcomes. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnardottir, H.H.; Dalli, J.; Norling, L. V.; Colas, R.A.; Perretti, M.; Serhan, C.N. Resolvin D3 Is Dysregulated in Arthritis and Reduces Arthritic Inflammation. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 2362–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredman, G.; Hellmann, J.; Proto, J.D.; Kuriakose, G.; Colas, R.A.; Dorweiler, B.; Connolly, E.S.; Solomon, R.; Jones, D.M.; Heyer, E.J.; et al. An Imbalance between Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators and pro-Inflammatory Leukotrienes Promotes Instability of Atherosclerotic Plaques. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titos, E.; Rius, B.; López-Vicario, C.; Alcaraz-Quiles, J.; García-Alonso, V.; Lopategi, A.; Dalli, J.; Lozano, J.J.; Arroyo, V.; Delgado, S.; et al. Signaling and Immunoresolving Actions of Resolvin D1 in Inflamed Human Visceral Adipose Tissue. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 3360–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontoria-Oviedo, I.; Amaro-Prellezo, E.; Castellano, D.; Venegas-Venegas, E.; González-Santos, F.; Ruiz-Saurí, A.; Pelacho, B.; Prósper, F.; Pérez del Caz, M.D.; Sepúlveda, P. Topical Administration of a Marine Oil Rich in Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators Accelerates Wound Healing in Diabetic Db/Db Mice through Angiogenesis and Macrophage Polarization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, N.; Hanes, D.; Bradley, R. Early Evidence of Efficacy for Orally Administered SPM-Enriched Marine Lipid Fraction on Quality of Life and Pain in a Sample of Adults with Chronic Pain. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, M.S.; Chen, M.; Colas, R.A.; Sorrentino, T.A.; Lazar, A.A.; Grenon, S.M.; Dalli, J.; Conte, M.S. Treatment With a Marine Oil Supplement Alters Lipid Mediators and Leukocyte Phenotype in Healthy Patients and Those With Peripheral Artery Disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shaer, A.E.; Regan, J.; Buddenbaum, N.; Tharwani, S.; Drawdy, C.; Behee, M.; Sergin, S.; Fenton, J.I.; Maddipati, K.R.; Kane, S.; et al. Enriched Marine Oil Supplement Increases Specific Plasma Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators in Adults with Obesity. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 1783–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regidor, P.A.; de la Rosa, X.; Müller, A.; Mayr, M.; Santos, F.G.; Banzo, R.G.; Rizo, J.M. PCOS: A Chronic Disease That Fails to Produce Adequately Specialized Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators (SPMs). Biomedicines 2022, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irún, P.; Gracia, R.; Piazuelo, E.; Pardo, J.; Morte, E.; Paño, J.R.; Boza, J.; Carrera-Lasfuentes, P.; Higuera, G.A.; Lanas, A. Serum Lipid Mediator Profiles in COVID-19 Patients and Lung Disease Severity: A Pilot Study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA; CDER Bioanalytical Method Validation. Guidance for Industry. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2018.

| Parameter | Values | Normal values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | 10 | |||

| Gender (male/female) | 5/5 | |||

| Age (years) | 31.81 ± 5.95 | |||

| IMC (kg/m2) | 23.94 ± 3.41 | |||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 89.60 ± 5.42 | 74-106 | ||

| BUN (g/l) | 0.33 ± 0.04 | Male: 0.19-0.44 Female: 0.15-0.40 |

||

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.83 ± 0.11 | Male: 0.7-1.2 Female: 0.5-0.9 |

||

| Albumin (g/dl) | 4.19 ± 0.30 | 3.5-5.2 | ||

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 188.50 ± 23.70 | National Education Cholesterol Program Adult treatment Panel III No risk < 200 Moderate risk 200-239 High risk > 240 |

||

| c-HDL (mg/dl) | 60.4 ± 17.00 | National Education Cholesterol Program Adult treatment Panel III At risk < 40 Negative risk > 60 |

||

| Non-HDL(mg/dl) | 128.1 ± 26.8 | |||

| c-LDL (mg/dl) | 109.78 ± 22.99 | 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias (cardiovaslular risk) | ||

| Risk level | c-LDL | Non c-HDL | ||

| Very high | < 55 | < 85 | ||

| High | < 70 | < 100 | ||

| Low | < 116 | not apply | ||

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 91.60 ± 46.56 | National Education Cholesterol Program Adult treatment Panel III Normal < 150 Borderline 150-199 High 200-499 Very high > 500 |

||

| AST (U/l) | 21.50 ± 4.09 | Male: 0-37 Female: 0-31 |

||

| ALT (U/l) | 16.20 ± 4.69 | Male: 0-41 Female: 0-33 |

||

| GammaGT (U/l) | 16.20 ± 5.41 | Male: 0-60 Female: 0-40 |

||

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/l) | 57.20 ± 11.33 | Male: 40-130 Female: 35-104 |

||

| Leukocyte count (mil/mm3) | 6.56 ± 1.84 | 4-11 | ||

| Neutrophil count (mil/mm3) | 3.22 ± 0.72 | 1.6-7.0 | ||

| Lymphocyte count (mil/mm3) | 2.54 ± 1.37 | 1.2-1.4 | ||

| Monocyte count (mil/mm3) | 0.47 ± 0.14 | 0.1-0.8 | ||

| Eosinophils count (mil/mm3) | 0.21 ± 0.07 | 0.0-0.4 | ||

| Basophils count (mil/mm3) | 0.04 ± 0.05 | 0.0-0.2 | ||

| Erythrocytes count (mill/mm3) | 4.98 ± 0.32 | Male: 4.5-5.9 Female: 3.5-5.1 |

||

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 17.77 ± 1.18 | Male: 13.0-17.4 Female: 12.0-15.3 |

||

| Hematocrit (%) | 43.33 ±3.37 | Male: 41.5-50.4 Female: 36.0-45.0 |

||

| MCV (fl) | 86.91 ± 3.88 | 82-98 | ||

| MCH (pg) | 29.63 ± 1.43 | Male: 27-32 Female: 27-31 |

||

| Sedimentation rate-1 hour (mm) | 7.10 ± 5.13 | 0-15 | ||

| Platelets count (mil/mm3) | 244.30 ± 49.18 | 150-400 | ||

| Prothrombin time (sec) | 12.79 ± 0.60 | 9.8-14.6 | ||

| Prothrombin activity (%) | 93.00 ± 7.18 | 80-120 | ||

| INR | 1.05 ± 0.05 | 0.8-1.2 | ||

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | 337.20 ± 47.82 | 200-400 | ||

| Control (water dosing) | Enriched-SPM marine oil supplementation | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 hours | 3 hours | 6 hours | 9 hours | 12 hours | 24 hours | 0 hours | 3 hours | 6 hours | 9 hours | 12 hours | 24 hours | |||||||||||||

| DHA metabolome | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DHA | 51.7(45.6-67.0) | 62.4(50.0-68.8) | 60.0(53.0-68.7) | 57.8(44.0-65.8) | 55.2(47.5-61.7) | 57.7(43.6-65.1) | 67.7(56.2-83.0) | 51.7(37.6-69.7) | 54.4(39.8-62.9) | 65.8(55.7-74.5) | 57.5(55.7-64.4) | 65.9(61.1-71.1) | ||||||||||||

| 14-HDHA | 1.4(1.1-3.0) | 1.2(0.7-2.6) | 1.4(1.1-2.0) | 0.9(0.6-1.8) | 0.8(0.5-1.8) | 1.1(0.6-3.3) | 0.7(0.6-4.2) | 17.4(13.9-32.3)** | 32.1(13.9-39.8)** | 3.9(2.2-6.2) | 2.1(1.7-6.1) | 2.7(1.6-4.8) | ||||||||||||

| 17-HDHA | 0.4(0.3-0.6) | 0.4(0.3-0.5) | 0.5(0.5-0.6) | 0.4(0.3-0.6) | 0.3(0.2-0.4) | 0.4(0.3-0.6) | 0.4(0.4-0.5) | 16.5(8.0-29.9)** | 16.2(11.1-36.0)** | 1.9(1.1-2.6)** | 0.7(0.6-1.0)* | 0.6(0.5-0.7) | ||||||||||||

| RvD1 | 2.6(0.0-4.0) | 4.0(0.0-5.1) | 3.1(0.6-3.9) | 3.3(0.6-5.0) | 1.8(0.0-4.1) | 3.2(0.7-3.9) | 1.3(0.0-4.1) | 4.5(1.0-7.4) | 4.9(4.1-7.7)* | 1.5(0.3-4.6) | 2.0(0.3-2.6) | 2.7(0.4-5.1) | ||||||||||||

| RvD2 | 0.0(0.0-3.6) | 1.4(0.0-5.9) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.9(0.0-2.5) | 2.5(0.5-3.0) | 0.0(0.0-2.9) | 2.5(0.0-4.3) | 4.2(0.8-5.3) | 5.7(2.7-6.9) | 2.1(0.0-3.4) | 3.3(0.4-4.3) | 2.7(0.2-4.5) | ||||||||||||

| RvD3 | 1.0(0.0-1.8) | 0.7(0.0-1.7) | 0.0(0.0-1.2) | 0.4(0.0-1.3) | 0.8(0.0-1.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.8) | 0.7(0.0-0.9) | 0.6(0.0-2.0) | 1.6(0.3-2.1) | 1.5(0.8-2.3)* | 1.1(0.3-1.3) | 0.6(0.1-1.0) | ||||||||||||

| RvD4 | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.7(0.0-4.5) | 0.0(0.0-2.6) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | ||||||||||||

| RvD5 | 3.1(2.2-4.6) | 4.8(3.3-17.0) | 3.3(0.3-4.2) | 3.6(0.6-5.8) | 2.6(1.8-4.8) | 3.9(2.7-4.7) | 4.9(1.1-6.2) | 58.3(16.6-121.1)** | 23.6(15.6-43.3)** | 7.9(4.7-11.6) | 5.3(3.0-7.4) | 5.2(2.8-7.7) | ||||||||||||

| PDX | 1.8(1.5-2.0) | 4.6(2.2-6.6)* | 2.9(0.8-3.8) | 2.5(0.5-3.5) | 2.2(1.7-3.7) | 1.9(0.0-2.9) | 1.9(1.5-3.0) | 31.2(6.3-49.2)* | 12.6(7.0-21.2)** | 3.9(0.5-6.5) | 2.9(2.2-3.7) | 2.0(1.1-3.8) | ||||||||||||

| PD1 | 1.6(0.2-3.2) | 0.0(0.0-3.3) | 2.3(0.0-3.6) | 2.3(0.4-3.0) | 3.3(0.4-4.0) | 1.6(0.0-3.3) | 2.3(1.7-4.1) | 8.5(5.8-10.3)* | 5.9(3.7-10.0)* | 3.5(2.1-5.5) | 1.4(0.3-3.0) | 0.0(0.0-2.1) | ||||||||||||

| MaR1 | 7.6(0.0-16.5) | 9.0(7.4-24.1) | 0.0(0.0-10.1) | 8.8(0.0-13.1) | 11.4(0.0-14.6) | 2.4(0.0-19.1) | 8.4(0.0-10.2) | 17.1(16.0-24.2)** | 3.5(0.0-19.8) | 7.2(0.0-26.7) | 11.8(10.1-13.4) | 8.8(0.0-10.5) | ||||||||||||

| MaR2 | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.4(0.0-1.6) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-1.1) | 0.0(0.0-1.1) | 1.1(0.0-1.9) | 0.0(0.0-2.0) | 39.3(23.0-62.9)** | 23.1(14.7-33.1)** | 3.2(1.5-6.7)* | 1.8(0.4-3.4)* | 1.7(0.4-3.3)* | ||||||||||||

| EPA metabolome | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| EPA | 47.0(33.8-53.4) | 42.9(25.2-62.9) | 53.9(37.7-66.3) | 44.5(27.1-51.0) | 28.5(19.5-45.3)* | 45.6(22.1-57.1) | 37.1(25.8-55.2) | 88.0(74.0-120.3)** | 120.7(106.3-126.0)** | 94.9(87.2-111.7)** | 87.9(84.7-99.4)** | 88.9(80.4-100.1)** | ||||||||||||

| 18-HEPE | 0.2(0.2-0.3) | 0.2(0.2-0.3) | 0.2(0.2-0.3) | 0.2(0.1-0.3) | 0.2(0.2-0.3) | 0.2(0.2-0.3) | 0.2(0.2-0.3) | 29.6(14.9-50.2)** | 16.4(12.6-30.9)** | 2.6(1.5-3.4)** | 0.9(0.7-1.1)** | 0.7(0.5-0.7)** | ||||||||||||

| RvE1 | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | ||||||||||||

| AA metabolome | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AA | 66.9(57.2-78.1) | 67.8(61.4-84.1) | 72.0(63.3-79.1) | 68.9(62.9-76.6) | 60.3(55.5-70.9) | 70.7(59.0-81.9) | 76.2(69.3-89.2) | 73.2(65.1-75.2) | 76.4(68.9-89.0) | 70.3(66.9-78.0) | 67.2(62.1-80.1) | 76.7(70.8-84.7) | ||||||||||||

| LXA4 | 0.6(0.0-1.3) | 1.7(0.0-2.3) | 0.8(0.2-1.3) | 0.8(0.1-1.3) | 0.4(0.0-0.9) | 0.3(0.0-1.2) | 0.6(0.0-1.7) | 1.7(0.2-2.8) | 1.7(0.3-2.1) | 1.8(0.2-2.5) | 0.8(0.1-1.6) | 0.8(0.0-1.4) | ||||||||||||

| LXB4 | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-4.7) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | ||||||||||||

| LTB4 | 77.0(45.6-109.6) | 98.5(72.0-141.3) | 90.9(38.1-141.5) | 120.7(66.4-156.1)* | 94.9(47.8-120.0) | 142.3(75.5-185.1)* | 84.9(30.8-97.0) | 111.7(49.4-123.4) | 88.9(43.4-125.6) | 69.7(52.1-118.6) | 106.7(89.4-155.1) | 75.8(65.2-151.3)* | ||||||||||||

| PGD2 | 4.2(3.0-8.1) | 6.3(2.8-9.6) | 4.6(3.3-4.9) | 3.9(3.2-11.1) | 4.5(3.1-5.2) | 4.8(3.2-6.5) | 3.5(3.3-6.0) | 3.7(2.3-6.2) | 4.2(2.8-6.7) | 3.1(2.4-4.4) | 3.8(2.7-5.3) | 3.3(2.6-4.9) | ||||||||||||

| PGE2 | 29.9(22.8-36.9) | 34.1(20.2-56.1) | 27.2(21.0-33.3) | 28.8(22.2-39.9) | 20.7(16.7-23.3)* | 25.1(22.1-35.7) | 14.6(11.9-15.3) | 27.9(20.3-36.8)** | 30.0(24.9-44.0)* | 24.2(17.0-25.2) | 18.6(12.5-38.6) | 19.7(15.7-24.2) | ||||||||||||

| PGF2α | 15.3(13.9-17.9) | 22.0(17.7-35.9) | 18.4(14.3-20.1) | 20.1(13.4-23.9) | 16.7(14.9-22.1) | 14.9(13.5-17.0) | 16.5(13.7-22.2) | 19.9(14.0-22.9) | 16.8(12.3-18.0) | 15.3(14.3-17.5) | 17.4(15.0-25.0) | 15.4(11.2-18.6) | ||||||||||||

| TxB2 | 362.0(212.6-482.6) | 422.8(190.0-831.3) | 299.8(220.8-417.5) | 349.0(166.0-664.6) | 272.3(164.5-387.8) | 234.7(139.5-270.9) | 158.1(74.3-247.6) | 297.2(207.6-388.4)* | 177.6(100.6-232.3) | 125.4(63.6-228.3) | 163.0(122.9-288.8) | 154.3(78.2-177.4) | ||||||||||||

| DPA metabolome | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DPA | 50.1(42.5-62.8) | 39.4(25.5-48.8) | 64.0(42.4-95.7) | 34.4(26.1-45.3)* | 22.5(16.7-30.2)* | 59.7(34.5-65.8) | 42.9(36.1-51.7) | 98.2(68.5-167.3)** | 180.2(124.7-205.4)** | 59.7(41.1-82.9)* | 41.1(27.1-68.0) | 58.3(45.0-82.4)* | ||||||||||||

| Control (water dosing) | Enriched-SPM marine oil supplementation | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 hours | 3 hours | 6 hours | 9 hours | 12 hours | 24 hours | 0 hours | 3 hours | 6 hours | 9 hours | 12 hours | 24 hours | |

| DHA metabolome | ||||||||||||

| DHA | 76.0(58.3-87.7) | 59.7(55.6-64.4) | 82.0(71.8-104.9) | 70.2(61.3-93.9) | 56.7(43.5-63.1) | 69.0(43.9-83.2) | 68.5(55.9-72.7) | 55.0(52.0-61.5) | 65.0(40.3-86.8) | 59.7(47.5-77.2) | 64.3(55.4-72.2) | 64.6(57.7-82.1) |

| 14-HDHA | 109.3(76.4-134.1) | 82.4(69.5-102.2) | 118.9(80.3-156.0) | 72.8(68.0-99.2) | 56.2(51.3-82.5)* | 109.4(81.4-126.6) | 102.1(72.8-137.1) | 175.2(123.2-209.1) | 219.7(180.7-268.7)** | 103.1(83.5-120.0) | 102.6(81.2-126.1) | 126.0(90.3-150.9) |

| 17-HDHA | 16.4(9.9-21.2) | 10.4(9.2-16.6) | 17.9(10.1-22.0) | 11.9(8.0-14.8) | 8.3(7.2-11.0)** | 16.4(13.5-18.9) | 13.3(10.4-27.0) | 44.7(26.3-58.3) | 60.5(46.4-112.6)** | 16.5(11.9-20.0) | 17.0(9.7-23.9) | 20.2(13.7-24.0) |

| RvD1 | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-3.6) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-2.5) |

| RvD2 | 3.4(0.5-4.4) | 2.9(1.8-3.9) | 2.0(0.0-4.2) | 0.0(0.0-2.2) | 0.8(0.0-2.6) | 0.0(0.0-0.9) | 0.0(0.0-2.9) | 0.0(0.0-1.0) | 3.2(0.0-4.3) | 3.5(1.9-4.6) | 1.8(0.0-3.1) | 2.6(0.5-3.7) |

| RvD3 | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-2.3) | 0.0(0.0-1.6) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-1.5) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-3.7) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-1.4) | 0.0(0.0-1.4) |

| RvD4 | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-1.9) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) |

| RvD5 | 48.2(27.3-77.0) | 39.4(30.5-50.3) | 48.2(33.0-71.9) | 38.8(35.4-43.0) | 33.3(26.9-61.5) | 53.8(35.6-72.5) | 64.5(32.3-90.7) | 234.3(130.7-312.4)* | 240.0(130.0-488.5)** | 72.3(48.8-112.6) | 60.9(47.2-111.9) | 79.5(70.6-88.2) |

| PDX | 56.9(49.1-87.1) | 52.7(48.3-82.4) | 58.3(47.0-122.5) | 52.9(37.3-94.1) | 41.9(31.9-75.0)* | 79.9(39.4-104.5) | 65.4(43.2-92.7) | 122.2(81.4-155.3) | 188.9(96.3-210.9)* | 63.3(49.6-106.4) | 61.7(49.2-131.6) | 79.2(62.3-130.7) |

| PD1 | 7.5(5.9-11.2) | 7.8(5.1-11.8) | 5.1(2.4-9.8) | 5.8(2.5-8.9) | 3.7(2.2-6.3)* | 5.6(0.7-7.9) | 8.3(6.2-10.3) | 13.3(9.3-19.7)** | 12.8(5.9-24.3) | 9.0(7.3-11.6) | 6.1(4.9-12.5) | 6.4(5.6-10.7) |

| MaR1 | 7.9(0.0-12.5) | 18.4(11.9-20.7)* | 11.7(0.0-38.1) | 18.9(8.4-31.1)* | 12.9(3.1-17.4) | 2.9(0.0-13.7) | 13.8(3.1-16.3) | 22.7(9.2-65.1) | 12.5(0.0-53.4) | 17.8(0.0-21.8) | 19.4(10.6-33.3) | 10.9(0.0-20.6) |

| MaR2 | 52.1(33.9-71.8) | 36.1(34.3-70.2) | 55.2(33.9-87.9) | 37.1(29.3-48.5) | 30.2(16.4-58.4) | 55.4(33.3-79.8) | 47.8(23.6-125.5) | 166.9(137.8-235.1) | 226.3(137.9-390.5)* | 47.7(40.2-76.3) | 54.9(38.0-127.2) | 68.3(49.2-84.0) |

| EPA metabolome | ||||||||||||

| EPA | 78.6 (62.7-87.9) | 82.0(67.1-87.0) | 80.6(71.4-99.4) | 84.0(55.5-95.1) | 64.3(54.8-79.1) | 61.6(45.8-84.1) | 69.3(61.0-78.1) | 99.1(86.1-115.9)* | 134.7(99.4-155.7)** | 109.2(97.0-139.2)* | 116.0(103.0-123.7)* | 116.2(112.0-121.2)** |

| 18-HEPE | 3.4(2.6-6.3) | 2.6(2.1-5.9) | 3.8(2.6-5.3) | 3.2(1.7-5.4) | 2.2(1.9-4.1)* | 3.4(2.6-5.0) | 3.4(2.3-6.4) | 37.7(20.7-58.3)* | 31.6(24.9-60.5)** | 9.6(8.2-13.8) | 10.4(6.5-14.3) | 10.1(5.7-17.5) |

| RvE1 | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-9.3) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-37.3) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-27.9) |

| AA metabolome | ||||||||||||

| AA | 101.8(88.6-125.4) | 89.2(83.9-115.7) | 126.6(81.4-140.6) | 102.4(83.3-134.4) | 87.7(81.0-105.9) | 101.0(70.9-130.4) | 105.1(96.5-116.2) | 100.7(83.5-118.3) | 105.4(85.0-128.9) | 109.1(79.7-127.7) | 94.9(87.1-103.4) | 99.2(88.2-108.2) |

| LXA4 | 1.3(1.0-3.3) | 0.8(0.0-2.1) | 1.3(0.0-1.7) | 0.4(0.0-1.4) | 1.7(0.9-2.2) | 1.3(0.2-2.6) | 1.8(1.1-3.1) | 2.2(0.4-2.7) | 1.9(0.4-3.1) | 0.0(0.0-1.6)* | 0.5(0.0-1.2)* | 2.0(0.0-2.8) |

| LXB4 | 4.3(0.0-15.3) | 0.0(0.08.2) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-3.3) | 0.0(0.0-3.9) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-0.0) | 0.0(0.0-26.2) | 0.0(0.0-6.0) | 2.0(0.0-7.5) |

| LTB4 | 526.7(211.3-680.6) | 379.8(326.3-575.2) | 391.5(268.6-598.6) | 267.1(217.6-360.6) | 311.2(190.2-572.1) | 330.0(239.0-493.7) | 406.0(245.8-471.8) | 428.9(267.3-574.5) | 507.8(297.9-719.2) | 285.6(177.9-414.9) | 401.3(226.9-541.1) | 474.1(289.1-591.9) |

| PGD2 | 101.4(67.8-160.3) | 109.4(67.9-172.1) | 137.4(101.4-183.8) | 125.0(85.8-205.5) | 120.7(88.8-159.4) | 118.9(79.6-413.2) | 146.2(82.5-178.1) | 122.5(86.5-183.5) | 90.5(62.7-139.8)* | 70.5(44.8-184.4) | 124.9(66.1-231.2) | 86.6(71.1-145.2) |

| PGE2 | 17108.2 (14972.2-33569.9) |

23277.6 (4963.2-34259.5) |

23348.0 (20979.7-31014.1) |

20607.8 (6011.2-43767.4) |

19912.2 (14690.2-31520.3) |

16471.9 (7613.6-51855.3) |

27618.9 (8779.9-37633.9) |

24636.2 (8194.4-40735.9) |

18231.1 (5721.1-25935.5) |

15037.9 (2624.0-37589.6) |

19513.7 (3637.4-35650.0) |

19594.4 (2631.4-26698.8) |

| PGF2α | 3827.7 (2754.4-4001.4) |

3249.5 (1963.8-4360.4) |

4545.5 (3588.5-4806.8) |

4199.8 (2933.9-6610.5) |

4000.6 (2765.7-5034.1) |

3740.5 (2234.1-8736.8) |

4377.2 (3210.0-5496.6) |

3732.9 (2716.5-4897.4) |

3274.1 (2613.5-4359.4) |

2979.8 (2162.5-5065.5) |

4011.4 (2316.6-4445.1) |

3315.2 (2874.6-3957.2) |

| TxB2 | 19806.9 (14400.2-27760.3) |

27790.8 (15922.1-31180.3) |

38756.6 (27045.2-47334.9) |

24570.9 (19173.9-32018.1) |

29234.7 (19041.8-42877.4) |

32345.3 (20572.8-46941.2) |

27305.0 (22935.3-40094.5) |

29370.3 (21000.7-32753.6) |

28810.5 (22468.0-43069.4) |

26064.5 (20533.9-36773.9) |

24540.2 (12355.5-30008.4) |

29810.3 (19209.5-36860.6) |

| DPA metabolome | ||||||||||||

| DPA | 59.0(38.4-70.1) | 40.0(35.3-49.6) | 72.5(55.5-78.2) | 38.6(34.3-49.5) | 49.4(39.7-62.8) | 51.8(42.9-71.3) | 51.9(47.9-61.5) | 125.8(82.0-147.5)* | 132.2(124.7-199.3)** | 64.4(57.4-80.6) | 61.3(55.7-68.3) | 65.9(55.7-81.8) |

| Cmax | Tmax | AUC | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Enriched-SPM marine oil | Control | Enriched-SPM marine oil | Control | Enriched-SPM marine oil | ||||||||||||||||

| AM | GM | SE | AM | GM | SE | p value | AM | GM | SE | AM | GM | SE | p value | AM | GM | SE | AM | GM | SE | p value | |

| DHA metabolome | |||||||||||||||||||||

| DHA | 17.29 | 0.00 | 5.07 | 17.21 | 0.00 | 5.53 | 1.000 | 9.43 | 7.75 | 2.65 | 9.75 | 8.31 | 2.25 | 0.766 | 227.08 | 0.00 | 79.71 | 158.70 | 0.00 | 57.58 | 0.571 |

| 14-HDHA | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.87 | 31.51 | 27.53 | 5.02 | 0.000 | 13.00 | 10.69 | 3.61 | 5.40 | 5.22 | 0.40 | 0.021 | 10.67 | 0.00 | 6.47 | 181.70 | 153.53 | 33.73 | 0.000 |

| 17-HDHA | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 31.59 | 26.01 | 5.82 | 0.000 | 6.00 | 5.31 | 1.13 | 5.10 | 4.87 | 0.46 | 0.727 | 1.56 | 0.00 | 0.49 | 125.38 | 106.76 | 21.44 | 0.000 |

| RvD1 | 6.75 | 0.00 | 4.54 | 5.08 | 4.61 | 0.75 | 0.038 | 7.50 | 5.58 | 2.54 | 7.20 | 5.83 | 1.96 | 0.888 | 37.61 | 0.000 | 14.53 | 62.89 | 44.94 | 16.43 | 0.602 |

| RvD2 | 5.38 | 0.00 | 2.97 | 5.42 | 0.00 | 1.47 | 0.307 | 9.38 | 7.14 | 2.57 | 6.67 | 6.08 | 0.97 | 0.619 | 40.72 | 0.00 | 13.35 | 48.521 | 0.00 | 14.25 | 0.347 |

| RvD3 | 5.69 | 0.00 | 4.94 | 1.83 | 1.69 | 0.24 | 0.064 | 10.71 | 7.44 | 3.58 | 9.00 | 7.56 | 1.90 | 0.960 | 20.68 | 0.00 | 14.60 | 15.47 | 12.80 | 2.763 | 0.667 |

| RvD4 | 2.51 | 0.00 | 2.51 | 2.44 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.113 | 3.00 | 3.00 | NA | 3.60 | 3.45 | 0.60 | 1.000 | 7.52 | 0.00 | 7.52 | 9.80 | 0.00 | 3.73 | 0.779 |

| RvD5 | 13.45 | 0.00 | 8.04 | 95.24 | 0.00 | 35.81 | 0.013 | 6.00 | 5.28 | 1.00 | 4.33 | 4.08 | 0.53 | 0.249 | 65.16 | 0.00 | 21.97 | 407.95 | 0.00 | 129.36 | 0.007 |

| PDX | 11.58 | 4.44 | 7.87 | 36.68 | 0.00 | 11.36 | 0.052 | 11.10 | 7.69 | 2.97 | 4.67 | 4.41 | 0.53 | 0.226 | 56.60 | 32.22 | 23.82 | 172.44 | 0.00 | 46.80 | 0.011 |

| PD1 | 8.23 | 0.00 | 5.51 | 7.09 | 0.00 | 1.35 | 0.112 | 12.33 | 8.82 | 3.14 | 3.67 | 3.50 | 0.44 | 0.028 | 50.63 | 0.00 | 22.45 | 52.04 | 0.00 | 12.71 | 0.832 |

| Mar-1 | 18.23 | 0.00 | 6.46 | 41.78 | 0.00 | 16.37 | 0.121 | 8.25 | 6.31 | 2.52 | 7.67 | 6.08 | 2.19 | 0.960 | 142.42 | 0.00 | 44.72 | 403.09 | 0.00 | 195.59 | 0.102 |

| Mar-2 | 7.50 | 0.00 | 5.49 | 62.05 | 47.34 | 14.77 | 0.001 | 10.88 | 7.90 | 3.10 | 4.20 | 3.96 | 0.49 | 0.077 | 59.60 | 0.00 | 40.16 | 261.43 | 211.55 | 56.24 | 0.000 |

| EPA metabolome | |||||||||||||||||||||

| EPA | 12.24 | 0.00 | 4.30 | 81.21 | 76.96 | 8.34 | 0.000 | 5.57 | 5.22 | 0.78 | 6.30 | 5.83 | 0.83 | 0.659 | 106.07 | 0.00 | 42.34 | 1182.33 | 1098.88 | 142.98 | 0.000 |

| 18-HEPE | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 41.33 | 33.53 | 8.66 | 0.000 | 8.67 | 6.78 | 2.26 | 4.20 | 3.96 | 0.49 | 0.087 | 0.93 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 178.36 | 151.26 | 34.06 | 0.000 |

| RvE1 | 31.66 | 0.00 | 22.02 | 39.44 | 0.00 | 25.17 | 0.485 | 6.00 | 5.20 | 3.00 | 12.75 | 11.17 | 3.95 | 0.348 | 187.84 | 0.00 | 153.12 | 350.11 | 0.00 | 295.95 | 0.409 |

| AA metabolome | |||||||||||||||||||||

| AA | 20.15 | 0.00 | 5.62 | 10.38 | 0.00 | 3.84 | 0.197 | 6.67 | 5.89 | 1.09 | 13.71 | 10.87 | 3.64 | 0.228 | 214.24 | 0.00 | 74.16 | 115.69 | 0.00 | 50.26 | 0.109 |

| LXA4 | 6.48 | 0.00 | 5.41 | 2.03 | 1.71 | 0.40 | 0.241 | 9.38 | 6.00 | 3.38 | 6.00 | 5.08 | 1.18 | 0.922 | 25.12 | 0.00 | 15.76 | 18.42 | 14.24 | 3.76 | 0.619 |

| LXB4 | 8.00 | 0.00 | 5.91 | 3.53 | 0.00 | 1.52 | 1.000 | 10.50 | 7.90 | 4.66 | 6.75 | 6.18 | 1.44 | 0.881 | 34.32 | 0.00 | 19.98 | 25.06 | 0.00 | 12.92 | 0.531 |

| LTB4 | 109.08 | 97.76 | 17.84 | 95.62 | 78.64 | 19.65 | 0.631 | 14.10 | 11.01 | 2.83 | 13.20 | 10.88 | 2.54 | 0.969 | 1083.07 | 986.61 | 155.18 | 1147.52 | 812.18 | 271.20 | 0.511 |

| PGD2 | 11.53 | 0.00 | 7.12 | 10.32 | 0.00 | 7.03 | 0.622 | 7.88 | 6.09 | 2.47 | 9.00 | 6.00 | 3.31 | 0.781 | 45.29 | 0.00 | 19.23 | 56.17 | 0.00 | 28.24 | 0.590 |

| PGE2 | 31.52 | 15.69 | 8.97 | 32.03 | 21.30 | 11.91 | 0.912 | 9.60 | 7.26 | 2.52 | 6.00 | 5.29 | 1.00 | 0.410 | 135.04 | 77.29 | 30.82 | 302.23 | 183.77 | 93.72 | 0.101 |

| PGF2α | 17.35 | 0.00 | 7.86 | 12.43 | 0.00 | 5.94 | 0.791 | 5.63 | 4.70 | 1.32 | 8.25 | 6.00 | 2.65 | 0.523 | 108.11 | 0.00 | 41.47 | 114.30 | 0.00 | 57.91 | 0.980 |

| TXB2 | 384.95 | 280.81 | 107.40 | 166.63 | 132.30 | 27.13 | 0.315 | 6.90 | 5.90 | 1.19 | 8.70 | 6.43 | 2.21 | 0.658 | 2913.55 | 1824.43 | 1031.20 | 1628.87 | 1209.08 | 323.46 | 0.196 |

| DPA metabolome | |||||||||||||||||||||

| DPA | 27.96 | 0.00 | 7.99 | 131.44 | 124.19 | 12.46 | 0.000 | 6.86 | 6.63 | 0.86 | 5.40 | 5.22 | 0.40 | 0.123 | 283.94 | 0.00 | 85.06 | 885.68 | 834.56 | 109.40 | 0.000 |

| Cmax | Tmax | AUC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Enriched-SPM marine oil | Control | Enriched-SPM marine oil | Control | Enriched-SPM marine oil | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AM | GM | SE | AM | GM | SE | p value | AM | GM | SE | AM | GM | SE | p value | AM | GM | SE | AM | GM | SE | p value | |||||||||||||||||||||

| DHA metabolome | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DHA | 26.41 | 11.39 | 9.83 | 25.29 | 0.00 | 6.23 | 0.631 | 10.20 | 8.34 | 2.38 | 11.00 | 8.94 | 2.60 | 0.799 | 192.35 | 64.20 | 77.99 | 181.63 | 0.00 | 43.62 | 0.742 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 14-HDHA | 27.33 | 0.00 | 10.01 | 142.20 | 123.93 | 24.68 | 0.000 | 9.67 | 7.56 | 2.73 | 6.90 | 5.60 | 1.95 | 0.295 | 229.37 | 0.00 | 100.79 | 1019.52 | 800.94 | 196.99 | 0.000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 17-HDHA | 4.31 | 0.00 | 1.73 | 63.80 | 0.00 | 13.35 | 0.002 | 10.50 | 8.19 | 3.00 | 5.33 | 5.14 | 0.44 | 0.127 | 36.33 | 0.00 | 17.10 | 328.22 | 0.00 | 65.23 | 0.000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| RvD1 | 1.72 | 0.00 | 0.79 | 2.11 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.765 | 9.00 | 6.00 | 5.05 | 6.75 | 6.00 | 1.89 | 0.879 | 6.15 | 0.00 | 2.78 | 27.96 | 0.00 | 13.54 | 0.147 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| RvD2 | 3.82 | 0.00 | 2.02 | 4.76 | 0.00 | 1.12 | 0.184 | 9.00 | 7.51 | 2.34 | 9.38 | 7.62 | 2.37 | 0.829 | 27.30 | 0.00 | 10.63 | 48.91 | 0.00 | 12.94 | 0.049 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| RvD3 | 1.38 | 0.00 | 0.56 | 1.45 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.781 | 12.00 | 8.49 | 4.03 | 5.40 | 4.55 | 1.75 | 0.289 | 15.67 | 0.00 | 8.58 | 17.28 | 0.00 | 9.49 | 0.572 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| RvD4 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 4.96 | 0.00 | 2.76 | 0.121 | 6.00 | 5.20 | 3.00 | 4.80 | 3.96 | 1.80 | 0.809 | 0.88 | 0.00 | 0.64 | 17.95 | 0.00 | 9.79 | 0.131 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| RvD5 | 24.33 | 0.00 | 7.32 | 273.67 | 132.61 | 58.45 | 0.001 | 11.67 | 8.54 | 3.14 | 5.10 | 4.87 | 0.46 | 0.129 | 197.61 | 0.00 | 72.63 | 1524.07 | 665.60 | 332.83 | 0.000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| PDX | 37.18 | 0.00 | 15.43 | 98.85 | 85.28 | 16.49 | 0.009 | 15.38 | 12.62 | 3.28 | 7.20 | 6.00 | 1.91 | 0.023 | 519.84 | 0.00 | 327.01 | 797.49 | 610.21 | 169.81 | 0.007 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| PD1 | 4.64 | 0.00 | 2.16 | 11.68 | 8.64 | 2.74 | 0.031 | 7.50 | 5.31 | 2.66 | 6.60 | 5.22 | 1.99 | 0.848 | 27.62 | 0.00 | 12.42 | 78.03 | 53.33 | 19.43 | 0.015 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Mar-1 | 59.75 | 28.18 | 32.54 | 66.62 | 0.00 | 35.58 | 0.579 | 7.20 | 6.51 | 1.02 | 6.00 | 5.38 | 1.00 | 0.414 | 501.50 | 203.70 | 320.76 | 754.21 | 0.00 | 506.62 | 0.546 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Mar-2 | 38.14 | 0.00 | 13.20 | 249.45 | 0.00 | 77.37 | 0.016 | 10.00 | 7.56 | 2.78 | 5.67 | 5.56 | 0.33 | 0.460 | 380.39 | 0.00 | 155.03 | 1187.84 | 0.00 | 343.44 | 0.001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| EPA metabolome | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| EPA | 17.88 | 0.00 | 4.64 | 93.60 | 59.28 | 23.43 | 0.002 | 9.86 | 8.21 | 2.60 | 8.40 | 7.26 | 1.83 | 0.572 | 143.12 | 0.00 | 40.38 | 1078.94 | 635.09 | 248.02 | 0.000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 18-HEPE | 1.41 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 48.23 | 0.00 | 10.85 | 0.002 | 13.71 | 10.43 | 3.70 | 4.33 | 4.08 | 0.53 | 0.022 | 15.92 | 0.00 | 5.47 | 326.87 | 0.00 | 56.79 | 0.000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| RvE1 | 103.61 | 0.00 | 66.11 | 40.76 | 0.00 | 14.82 | 0.532 | 12.60 | 10.45 | 3.34 | 9.43 | 6.00 | 3.79 | 0.393 | 708.14 | 0.00 | 422.16 | 365.62 | 0.00 | 170.34 | 0.296 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| AA metabolome | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| AA | 34.00 | 0.00 | 10.87 | 26.18 | 0.00 | 9.51 | 0.545 | 13.67 | 11.78 | 2.65 | 10.00 | 8.94 | 1.94 | 0.336 | 284.67 | 0.00 | 95.71 | 172.00 | 0.00 | 39.99 | 0.306 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| LXA4 | 2.55 | 0.00 | 1.08 | 1.48 | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.702 | 12.00 | 9.07 | 3.34 | 12.86 | 8.92 | 3.97 | 1.000 | 18.48 | 0.00 | 7.07 | 15.12 | 0.00 | 5.31 | 0.157 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| LXB4 | 6.39 | 0.00 | 4.11 | 10.88 | 0.00 | 5.43 | 0.482 | 11.25 | 8.49 | 4.64 | 13.80 | 10.70 | 4.31 | 0.802 | 41.09 | 0.00 | 27.45 | 70.86 | 0.00 | 30.28 | 0.509 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| LTB4 | 219.86 | 0.00 | 91.14 | 224.27 | 0.00 | 66.01 | 0.448 | 9.00 | 7.02 | 2.78 | 11.33 | 8.17 | 3.19 | 0.868 | 2271.84 | 0.00 | 1062.66 | 1962.96 | 0.00 | 643.55 | 0.676 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| PGD2 | 166.23 | 102.59 | 50.86 | 50.67 | 0.00 | 34.54 | 0.014 | 14.70 | 12.65 | 2.59 | 8.57 | 6.36 | 2.89 | 0.099 | 1449.61 | 772.28 | 478.45 | 523.32 | 0.00 | 336.81 | 0.018 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| PGE2 | 21848.97 | 0.00 | 6352.51 | 9748.40 | 0.00 | 6561.40 | 0.072 | 13.88 | 11.17 | 3.10 | 7.00 | 4.76 | 3.44 | 0.071 | 237403.15 | 0.00 | 85313.21 | 78700.96 | 0.00 | 63805.26 | 0.072 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| PGF2α | 3559.09 | 0.00 | 1187.05 | 965.85 | 0.00 | 555.45 | 0.052 | 15.33 | 13.13 | 2.80 | 6.50 | 5.72 | 1.43 | 0.040 | 36333.89 | 0.00 | 13191.80 | 10065.52 | 0.00 | 7378.03 | 0.021 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| TXB2 | 24746.36 | 0.00 | 5917.52 | 29064.68 | 0.00 | 16808.12 | 0.307 | 12.67 | 9.96 | 2.95 | 13.50 | 10.24 | 3.26 | 0.882 | 321567.88 | 0.00 | 97455.88 | 250355.73 | 0.00 | 133126.57 | 0.577 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| DPA metabolome | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DPA | 28.80 | 0.00 | 7.54 | 111.40 | 0.00 | 22.95 | 0.003 | 9.00 | 7.31 | 2.70 | 5.00 | 4.76 | 0.50 | 0.158 | 233.06 | 0.00 | 78.44 | 724.19 | 0.00 | 165.43 | 0.000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| kcal | Fat (g) | Protein (g) | Carbohydrates (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breakfast | ||||

| Skim milk, 1 cup | 70.0 | 0.6 | 6.4 | 9.6 |

| Bread, 2 slices with tomatoe | 158.0 | 0.8 | 3.9 | 13.3 |

| Apple, 1 medium | 108.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 22.8 |

| Lunch | ||||

| Lentils with vegetables | 365.0 | 8.3 | 21.0 | 43.8 |

| Grilled chicken | 217.5 | 9.3 | 33.3 | 0.0 |

| Pear, 1 medium | 84.0 | 0.2 | 0.73 | 3.7 |

| Snack | ||||

| Skim milk, 1 cup | 70.0 | 0.6 | 6.4 | 9.6 |

| Biscuits, 8 units | 248.0 | 10.4 | 3.2 | 35.2 |

| Apple, 1 medium | 108.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 22.8 |

| Dinner | ||||

| Salad | 131.7 | 10.8 | 2.3 | 4.9 |

| Grilled pork loin | 466.5 | 39.9 | 24.4 | 1.5 |

| Roasted green pepper | 35.4 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 2.9 |

| Low-fat yoghurt | 50.0 | 0.5 | 4.8 | 5.6 |

| Analyte | LLOQ (pg/ml) |

|---|---|

| Docosahexaenoic acid, DHA | 0.02 |

| Docosapentaenoic acid, DPA | 0.15 |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid, EPA | 0.01 |

| Arachidonic acid, AA | 0.02 |

| 14-hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid, 14-HDHA | 0.08 |

| 17-hydroxydocosahexaenoic acid, 17-HDHA | 0.33 |

| 18-hydroxyeicosapentaenoic acid, 18-HEPE | 0.24 |

| Leucotriene B4, LTB4 | 0.25 |

| Lipoxin A4, LXA4 | 0.28 |

| Lipoxin B4, LXB4 | 0.25 |

| Maresin 1, MaR-1 | 0.74 |

| Maresin 2, MaR-2 | 0.18 |

| Prostaglandin D2, PGD2 | 0.17 |

| Prostaglandin E2, PGE2 | 0.30 |

| Prostaglandin F2α, PGF2α | 0.43 |

| Protectin D1, PD1 | 0.15 |

| Protectin DX, PDX | 0.30 |

| Resolvin E1, RvE1 | 0.21 |

| Resolvin D1, RvD1 | 0.64 |

| Resolvin D2, RvD2 | 0.97 |

| Resolvin D3, RvD3 | 0.30 |

| Resolvin D4, RvD4 | 0.42 |

| Resolvin D5, RvD5 | 0.25 |

| Tromboxane B2, TXB2 | 0.29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).