1. Introduction

The neuromuscular system is a large component of the human body, accounting for roughly 40% of an adult human’s mass [

1], and is required for many recreational activities i.e. sports, as well as daily activities of living such as stair climbing, breathing, digestion, and getting into and out of automobiles [

2]. Unfortunately, the skeletal muscles and the motor neurons that innervate them are too often targeted by diseases such as the muscular dystrophies, or are the recipients of accidental injury [

3]. The expense for treating and managing these afflictions is exorbitant as collectively, costs of treating diseases and injuries to the neuromuscular system, annually, amounts to approximately

$2,258 million [

4]. Accordingly, it is crucial that mechanisms underlying neuromuscular damage and recovery from such challenges are well understood. One of the most effective models the scientific community has in studying injury and repair of the neuromuscular system is the application of cardiotoxins including BaCL

2 onto skeletal muscle to cause injury in order to then treat that injury with various recuperative agents or procedures such as mitochondrial transplant therapy (MTT). While this intervention has proved to be effective in generating damage to skeletal muscle, it is not yet clearly known if it is equally effective in treating the damaged synapses, or neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) that play such an essential and central role in neuromuscular function. In view of the paucity of such information, the current project was conducted in order to determine whether MTT was effective in regenerating not only skeletal muscle tissue, but also healthy NMJs in toxin damaged skeletal muscle tissue2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Subjects and Tissue

This investigation utilized male C57BL\6 mice (Jackson Laboratories, MA) at 8-12 weeks of age to study the identified research questions driving this investigation. Widespread muscle necrosis was caused by injecting 50 μL of 1.2% BaCl2 into the EDL muscle of one limb in male C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Labs, MA, USA) that were 8–12 weeks of age (n = 6–8). The right or left gastrocnemius was randomly injured with BaCl2, and the opposite muscle served as the non-injured (50 μL PBS-injected) control muscle.

Muscle necrosis was caused by injecting BaCl

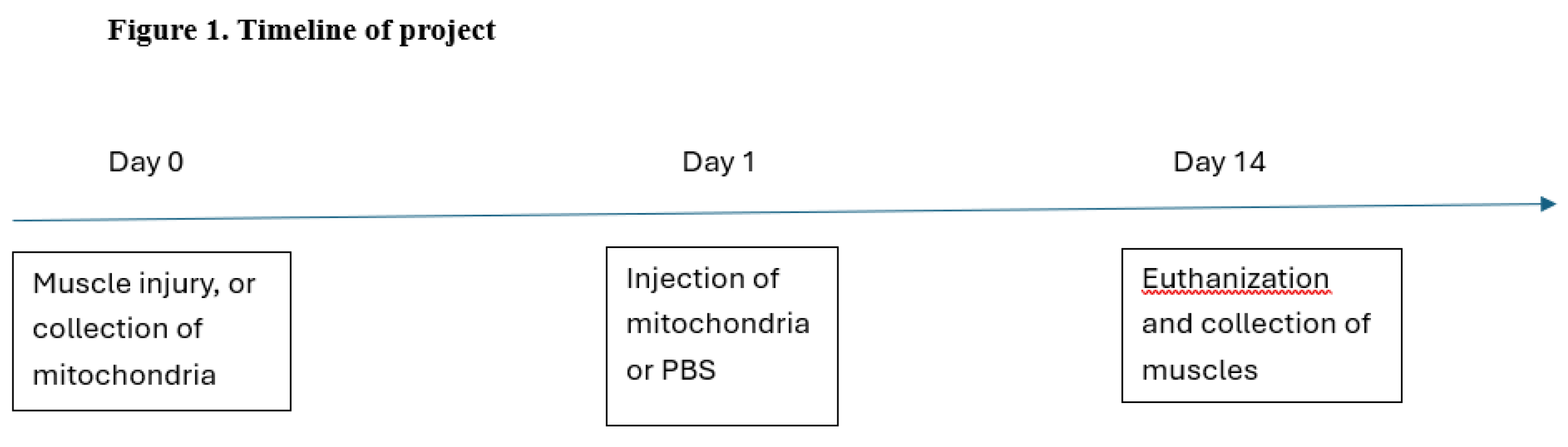

2 (a known muscle toxin) in one limb muscle of the mice, while the opposite leg was injected with harmless phosphate buffered saline solution (PBS) so that legs of the same animal acted as contralateral controls. Twenty-four hours after the muscle damaging event, mice received either an injection of previously isolated mitochondria diluted in PBS forming the MTT condition, or the same volume of PBS alone to create a sham treatment group of injured control muscle tissue. After an adequate recovery period of 7-14 days, respiratory function of the transplanted mitochondria was assessed by adding cytochrome C, which did not stimulate respiration by more than 15% indicating that mitochondria had been successfully transplanted and were promoting normal respiration. Another procedure used to confirm the successful transfer of mitochondrial material into damaged leg muscles featured injecting 50 ug of fluorescently labelled mitochondria diluted in 50 uL of PBS solution into the tail vein of host mice which were then euthanized 24 hours after the MTT procedure was completed. A schedule of this treatment program can be found in

Figure 1. Tissue sections were then examined for mitochondria labelled with Mito Tracker after incubation with anti-dystrophin antibody to identify myofiber sarcolemma and whether labelled mitochondria had been included into myofibers. This array of treatments provided a total of four experimental groups: 1) Control, i.e. receiving no toxin, and no treatment, 2) Damaged and treated, i.e. receiving toxin plus mitochondrial treatment, 3) Positive control; receiving no toxin but subjected to mitochondrial treatment, and 4) Damaged without treatment, i.e., receiving toxin without mitochondrial treatment.

All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the host research university.

2.2. Cytofluorescent Staining of NMJs

For the present study the EDL muscle was utilized for staining and imaging of NMJs. The EDL is a rather slender muscle mainly comprised (≥90%) of fast-twitch myofibers [

5]. The procedure begins with obtaining 40 µm thick longitudinal sections at -20°C from the middle third of the muscle’s belly which is then placed on a microscope slide pretreated with EDTA solution to prevent muscle contraction. Sections were then washed 4 times for 15 minutes each in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) to minimize non-specific antibody binding. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C in supernatant of the primary antibody RT97 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa) diluted 1:20 in PBS with 1% BSA. RT97 reacts with non-myelinated sections of the pre-synaptic nerve terminal allowing for identification of pre-synaptic terminal branching. The following day, muscle sections were again washed 4 x 15 min in PBS with 1% BSA prior to being incubated for two hours at room temperature in Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated secondary antibody (ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) diluted 1:200 in PBS with 1% BSA. Sections were then washed 4 x 15 minutes in PBS with 1% BSA, and then incubated overnight in a humidified chamber at 4°C in solution containing rhodamine conjugated α-bungarotoxin (BTX; catalog number T1175, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) diluted 1:600 in PBS along with anti-synaptophysin (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) at a dilution of 1:50. BTX is a neurotoxin that binds with high affinity and specificity to post-synaptic acetylcholine (ACh) receptors. In turn, anti-synaptophysin reacts with ACh containing pre-synaptic vesicles of the NMJ. The following day, sections were again washed 4 x 15 minutes in PBS before incubation for two hours in a humidified chamber at room temperature in AlexaFluor 647 (Molecular Probes, LeLand, NC) conjugated secondary antibody diluted 1:200 in PBS to detect anti-synaptophysin on the membranes of the pre-synaptic vesicles. After washing muscle sections for 4 x 15 minutes in PBS they were lightly coated with Prolong (Molecular Probes) and sections were stabilized by placing cover slips atop the muscle sections. Slides were then coded with respect to treatment group to allow for blinded evaluation of NMJ morphology before being stored in the dark at -20°C until analysis. An example of the effects of this staining procedure can be seen in

Figure 2. .

2.3. Microscopy

An Olympus Fluoview FV 3000 confocal system featuring three lasers and an Olympus BX60 fluorescent microscope (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) was used to collect and store images of NMJs. Using a 100x oil immersion objective, it was initially established that the entire NMJ was within the longitudinal borders of the myofiber and that damage to the structure had not occurred during sectioning. A detailed image of the entire NMJ was constructed from a z-series of scans taken at 0.5 µm thick increments. Digitized, two-dimensional images of NMJs were stored on the system’s hard drive and later quantified with the Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD). In each muscle, 10–12 NMJs were quantified and measurements were averaged to represent NMJ morphology within that muscle.

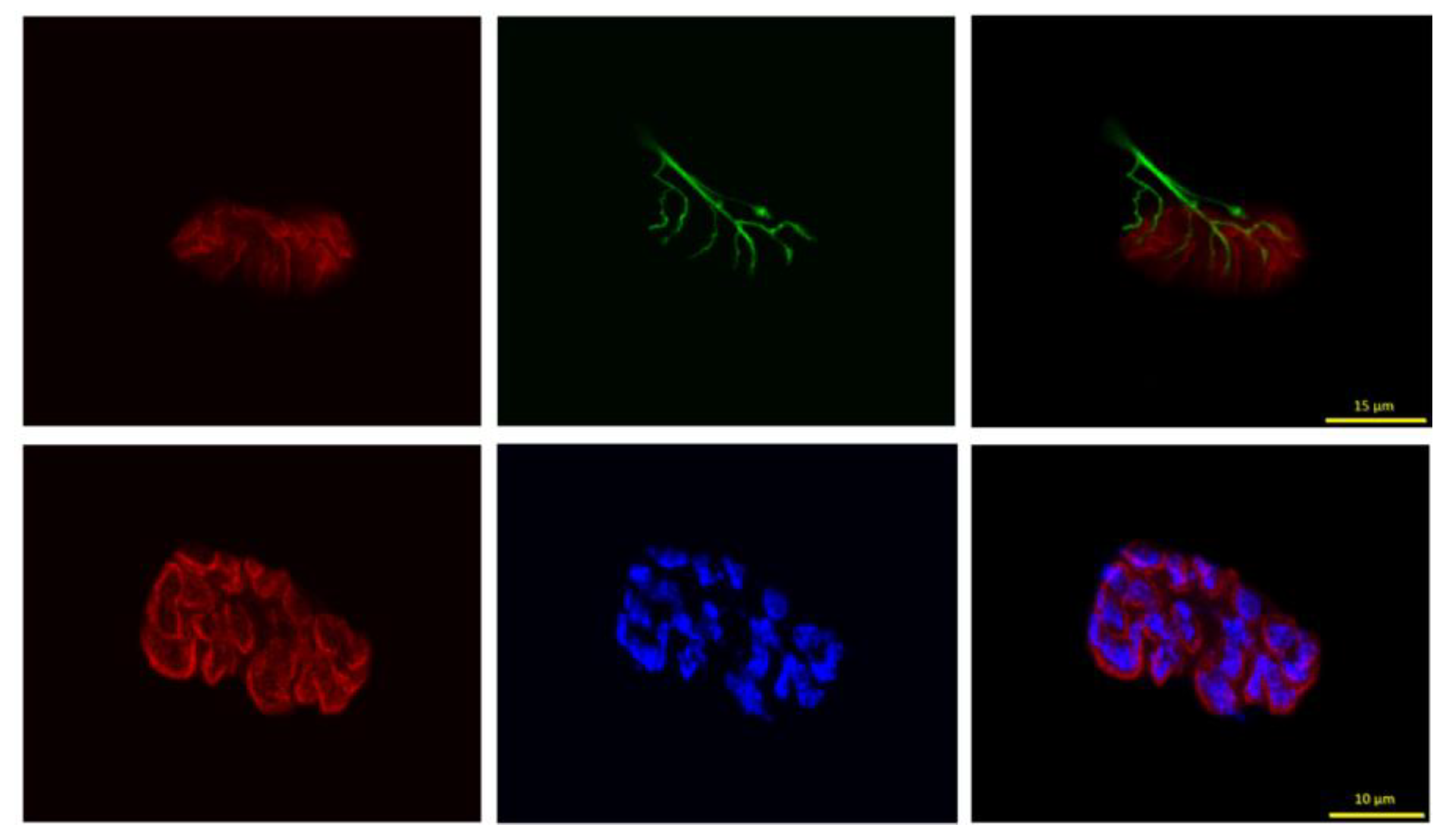

2.4. NMJ Variables Assessed

Pre-synaptic variables of NMJs assessed included: 1) number of branches identified at the nerve terminal; 2) the total length of those branches; 3) average length per branch; and 4) branching complexity, which, as described by Tomas et al. [

6] is derived by multiplying the number of branches by the total length of those branches and dividing that figure by 100. Pre-synaptic vesicular staining was assessed by quantifying: 1) total perimeter, or the length encompassing the entire vesicular region comprised of stained vesicular clusters and non-stained regions interspersed within those clusters; 2) stained perimeter, or the composite length of tracings around individual clusters of vesicles; 3) total area which includes stained vesicles along with non-stained regions interspersed among vesicle clusters; 4) stained area, or the cumulative areas occupied by ACh vesicular clusters; and 5) dispersion of vesicles, which was assessed by dividing the vesicular stained area by its total area and multiplying by 100. Post-synaptic variables of interest included: 1) total perimeter, or the length encompassing the entire endplate comprised of stained receptor clusters and non-stained regions interspersed within those clusters; 2) stained perimeter length, or the composite length of tracings around individual receptor clusters; 3) total area, which includes stained receptors along with non-stained regions interspersed among receptor clusters; 4) stained area, or the cumulative areas occupied by ACh receptor clusters; and 5) dispersion of endplates, which was assessed by dividing the endplate’s stained area by its total area and multiplying by 100. In this study, pre- to post-synaptic coupling was quantified by dividing the NMJ’s post-synaptic stained area by its total length of nerve terminal branching, as well as by quantifying the percentage of the area of post-synaptic staining of receptors that was overlapped with staining of pre-synaptic ACh vesicles. Finally, to approximate the number of ACh containing vesicles supported by a given length of pre-synaptic nerve terminal branch length, the stained area occupied by vesicles was divided by the total length of branching for that NMJ.

Figure 3 demonstrates how these measurements were acquired.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All results are reported as means ± SD. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare means for each of the treatment groups. In the event of a significant F-ratio, Tukey post-hoc analysis was performed to identify significant pair-wise differences. In all cases, significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Synaptic Branching

The results collected here failed to identify any significant differences in branching patterns between the four treatment groups examined. Although not found to be statistically significant, analysis revealed that the group with the greatest number of branches at nerve terminals was exhibited by the group that received muscle damage without any curative supplement, i.e. 4.5 branches per terminal vs. 3.9 branches in Controls. This was not unexpected as it has been previously reported that damaged muscle tissue often undergoes compensatory sprouting of new nerve terminal branches [

7,

8,

9].

Similarly, no significant between group differences in total, or average branch length per NMJ were detected. Interestingly, however, there was evidence that application of damaging agent without accompanying recuperative procedure resulted in the longest average branch length as average branch length in injured muscle was 30 µm compared to average branch length in control muscle which was 20 µm. Results of the examination of branching complexity which factors in both branch number and branch length, also failed to expose statistically significant results although once again, the greatest complexity was noted in damaged muscles without mitochondrial treatment with the lowest amount of complexity identified among Control, uninjured muscles. Results of nerve terminal branching analysis can be found in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Effects of injury with and without mitochondrial supplement on pre-synaptic neuromuscular junction morphology.

Table 1.

Effects of injury with and without mitochondrial supplement on pre-synaptic neuromuscular junction morphology.

| Variable |

|

ControlϦ(N = 10/14) |

|

Uninjured with supplementϦ(N= 10/16) |

|

Injured without supplementϦ(N= 9/15) |

|

Injured with supplementϦ(N= 9/14) |

| Nerve terminal branch number |

|

3.9 ± 1.6 |

|

3.6 ± 1.1 |

|

4.5 ± 1.6 |

|

4.1 ± 1.0 |

| Total branch length (µm) |

|

81.9 ± 22.8 |

|

95.0 ± 30.2 |

|

85.0 ± 40.6 |

|

86.8 ± 20.4 |

| Average branch length (µm) |

|

20.4 ± 9.6 |

|

27.2 ± 9.9 |

|

30.1 ± 26.1 |

|

22.6 ± 6.7 |

| Branching complexity (%) |

|

3.6 ± 1.8 |

|

3.8 ± 1.4 |

|

4.8 ± 3.2 |

|

3.9 ± 1.4 |

| 00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total perimeter length around vesicles (µm) |

|

429.0 ± 230.7 |

|

309.3 ± 218.2 |

|

145.7 ± 90.5* |

|

398.6 ± 209.1 |

| Stained vesicular perimeter length (µm) |

|

159.2 ± 54.6 |

|

196.6 ± 129.0 |

|

217.5 ± 73.2 |

|

150.8 ± 65.8 |

| Total vesicle area (µm2) |

|

97.3 ± 11.5 |

|

89.7 ± 12.0 |

|

92.3 ± 7.8 |

|

95.5 ± 9.8 |

| Stained vesicle area (µm2) |

|

240.6 ± 105.1 |

|

186.0 ± 88.6 |

|

109.4 ± 50.5* |

|

212.4 ± 81.6 |

| Vesicle dispersion (%) |

|

27.8 ± 5.8 |

|

23.3 ± 6.2 |

|

19.7 ± 4.2* |

|

24.4 ± 5.6 |

| Vesicle density |

|

3.4 ± 0.5¶ |

|

2.9 ± 0.3 |

|

3.5 ± 0.5 |

|

3.1 ± 0.4 |

| Pre- to post-synaptic coupling (%) |

|

65.9 ± 4.6 |

|

67.0 ± 10.5 |

|

67.0 ± 5.0 |

|

60.9 ± 9.1* |

| Endplate/branching |

|

1.07 ± 0.2 |

|

0.92 ± 0.2 |

|

0.87 ± 0.1§

|

|

0.89 ± 0.08 |

Table 2.

Effects of injury with and without mitochondrial supplement on post-synaptic neuromuscular junction morphology.

Table 2.

Effects of injury with and without mitochondrial supplement on post-synaptic neuromuscular junction morphology.

| Variable |

|

ControlϦ(N = 10) |

|

Uninjured with supplementϦ(N= 10) |

|

Injured without supplementϦ(N= 9) |

|

Injured with supplementϦ(N= 9) |

| Total perimeter length (µm) |

|

433.5 ± 219.4 |

|

336.2 ± 205.3 |

|

384.0 ± 256.9 |

|

439.4 ± 233.2 |

| Stained perimeter length (µm) |

|

246.9 ± 43.0 |

|

244.6 ± 49.4 |

|

239.4 ± 57.8 |

|

263.0 ± 36.6 |

| Total area (µm2) |

|

219.9 ± 217.4 |

|

314.5 ± 269.0 |

|

227.0 ± 190.7 |

|

239.6 ± 228.1 |

| Stained area (µm2) |

|

239.0 ± 73.1 |

|

216.8 ± 52.0 |

|

235.6 ± 110.9 |

|

244.9 ± 88.5 |

| Receptor dispersion (%) |

|

26.6 ± 6.2 |

|

27.5 ± 2.9 |

|

31.0 ± 4.0 |

|

28.6 ± 4.6 |

In addition to nerve terminal branching, pre-synaptic morphology was assessed by examining ACh containing vesicles, and in doing so, numerous significant and meaningful findings were revealed including total perimeter where ACh vesicles displayed smaller lengths among injured muscles not receiving treatment, than among Control mice and those that were injured but also received mitochondrial treatment. This last discovery is of particular interest in that it points to the effective treatment of damaged muscles and their synapses by adding mitochondria to the site of injury.

When evaluating stained areas comprised solely of pre-synaptic vesicles and not the regions interspersing them, statistically significant differences were detected. As with perimeter length surrounding the entire area of residing vesicles, it was determined that the area occupied by stained ACh receptors was lower in damaged untreated muscles, than in all other treatment groups. When quantifying total area covered by pre-synaptic vesicles i.e. both vesicles and area interspersing them, it was again found to be statistically similar among the four treatment groups. Results presented by the analysis of ACh vesicle dispersion within the pre-synaptic nerve terminal ending are once again, statistically significant. More specifically, vesicle dispersion arrived at by dividing stained area by total area shows that damaged but untreated muscle is far more dispersed than the vesicles of control muscles (recall that a lower number signifies greater dispersion). Finally, the density of vesicle distribution at pre-synaptic nerve terminals showed a significant difference whereby muscles that were damaged but received mitochondrial therapy displayed a greater density of vesicles than uninjured muscles who received mitochondrial therapy. Results concerning pre-synaptic ACh vesicles are presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Post-Synaptic Endplate

ACh receptors are the main component of the post-synaptic endplate and they are typically positioned in direct apposition from pre-synaptic vesicles to maximize successful diffusion of ACh across the synapse from release sites (vesicles) to binding sites, i.e., receptors [

10,

11]. Typically, these receptors are identified by their binding of the snake toxin α-bungarotoxin (BTX) which binds to ACh receptors with high specificity and affinity [

9]. Here, we used BTX conjugated with the fluorochrome rhodamine, which emits a bright red hue that is typically quite easy to identify on tissue exposed to it. (Of course, the toxin can be conjugated with other fluorochromes to emit other colors besides red.) In examining post-synaptic morphology it is important to remember that the endplate features a series of infoldings i.e. junctional folds, that express the majority of ACh receptors [

10]. In this way, there can be a disproportionately high number of binding sites at the endplate, in turn, allowing a small amount of neurotransmitter released by the nerve terminal to provide an exaggerated response relative to the amount of neurotransmitter released. This “safety factor” is designed to ensure that a post-synaptic response will indeed occur following electrical stimulus [

11].

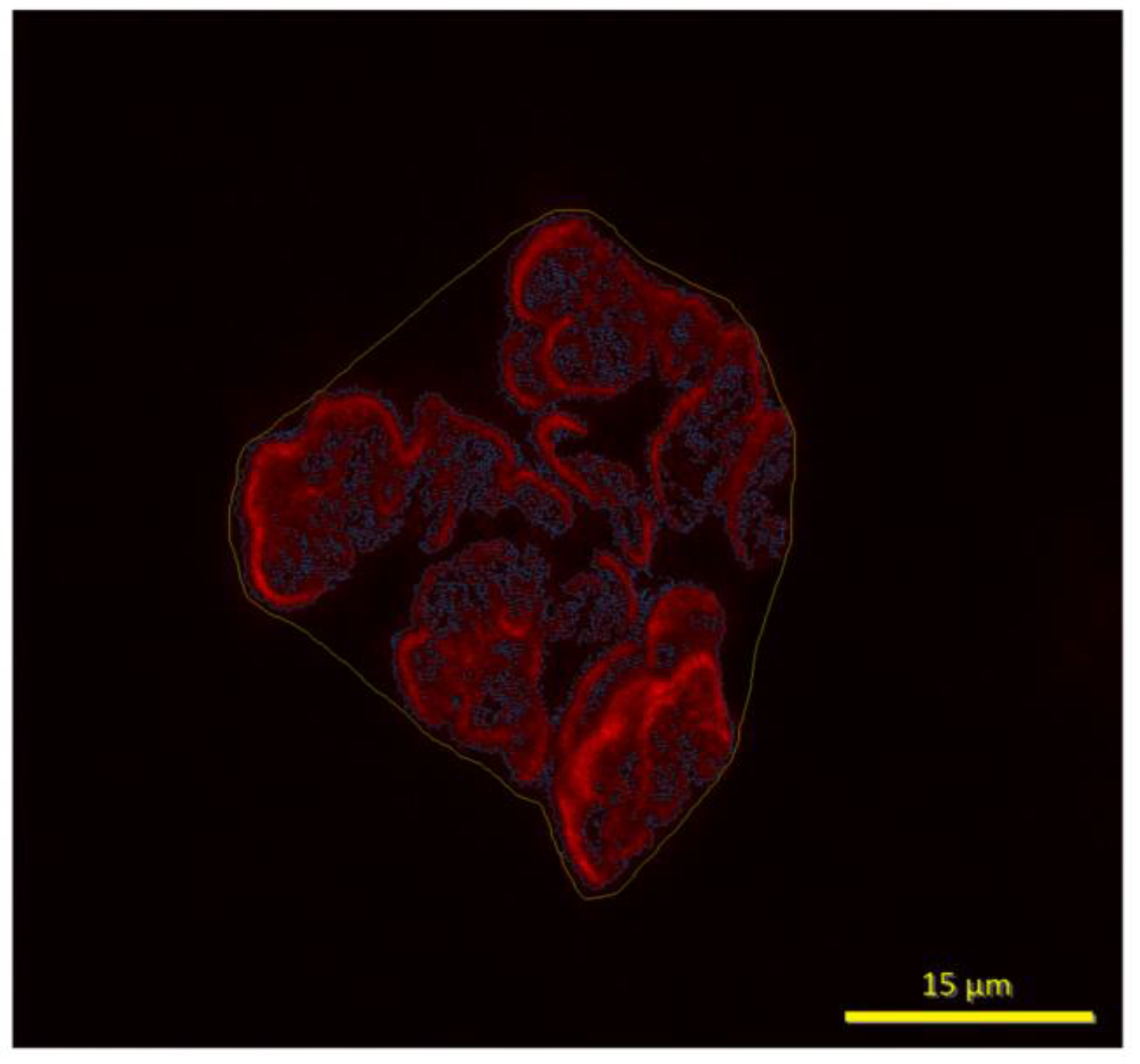

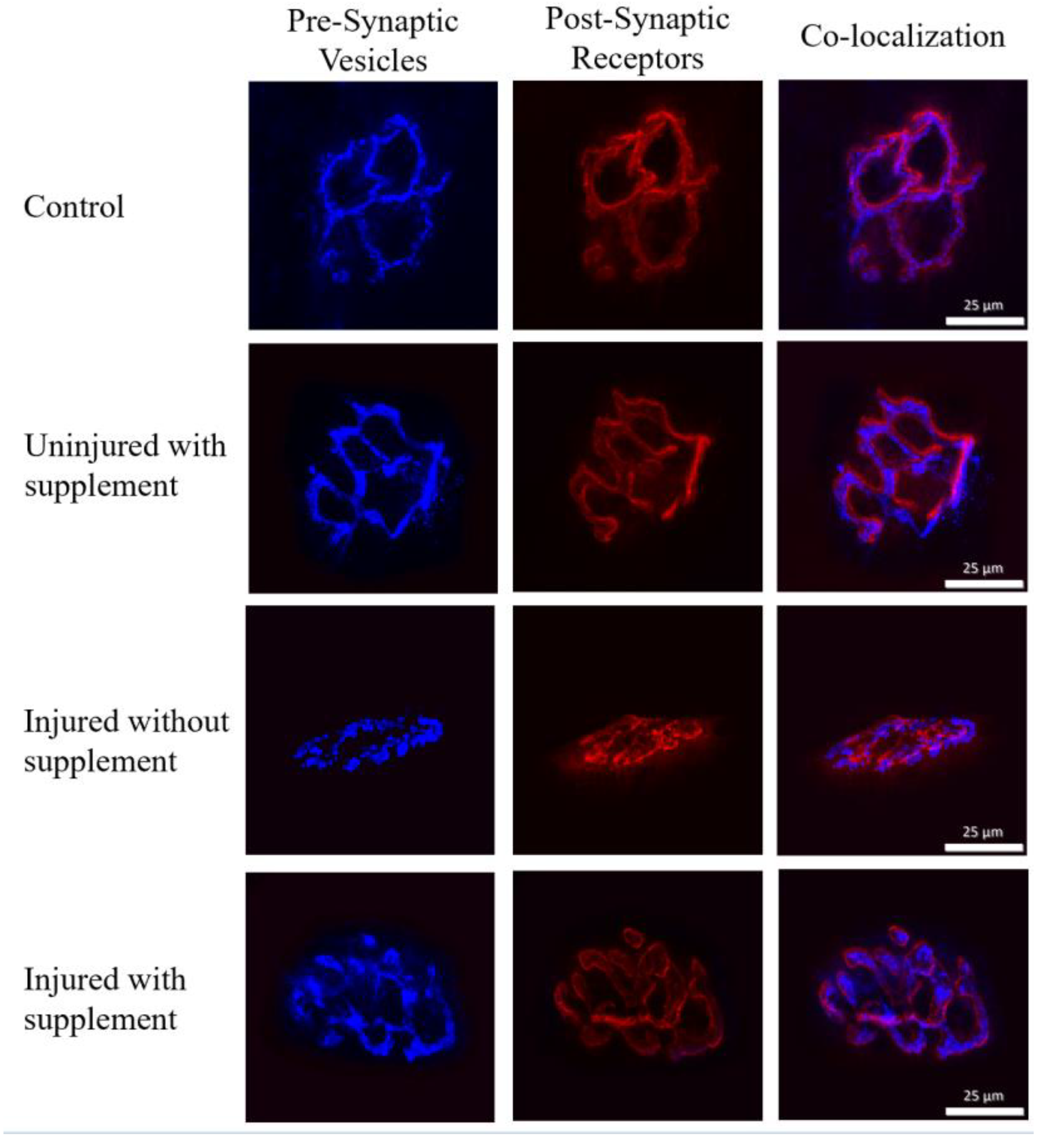

Despite yielding high quality staining resolution (see

Figure 2 ), measurements across the post-synaptic variables assessed here failed to document any statistically significant differences among the various treatment groups featured here. That is, perimeter length of the endplate, whether it be the total length around receptor clusters and the spaces interspersed among receptor clusters, or exclusively the stained receptor clusters, and post-synaptic area – again whether assessed as total area, or only as stained cluster areas were found to be similar (

P>0.05) among the four treatment groups observed here. It is worth pointing out, however, that when examining the dispersion of ACh receptor clusters in the endplate region a trend (

P = 0.06) towards significance was established whereby Control NMJs showed the most severe dispersion. It could be reasonably concluded then that neither the application of cardiotoxin and/or treatment with mitochondrial material presented a powerful enough stimulus to significantly alter the distribution of receptor clusters within the post-synaptic endplate region. In summarizing the overall findings of the current investigation, it should be underscored that it was driven by the following questions: 1) is the cardiotoxin BaCl

2, although powerful enough to bring about skeletal muscle damage [

12] also strong enough to elicit damage to the NMJs located on myofiber surfaces? This is an important question since it is increasingly being recognized that for skeletal muscle to perform optimally, the NMJ must be healthy and able to perform optimally as well [

13]. The data collected here reveal that BaCl

2 is indeed potent enough to cause structural damage to the NMJ, but only at the level of pre-synaptic ACh containing vesicles, resulting in uncoupling of pre-synaptic release sites from their post-synaptic binding sites. It has been suggested that such uncoupling reduces the probability that ACh released into the synaptic cleft will successfully cross the synapse to bind with post-synaptic receptors allowing for proper neurotransmission [

14]. Moreover, does treating toxin injured muscle with transplanted mitochondria, convey restorative effects on damaged NMJs. The data provided here suggest that this is in fact true. Finally, does the application of mitochondria to surfaces of healthy muscle cells provoke morphological restructuring of NMJs and would such changes confer beneficial or negative effects on function?

Figure 4 displays panels of stained NMJs i.e., pre- and post-synaptic components, as well as co-localization of pre-synaptic vesicles with post-synaptic receptors.

4. Discussion

Due to the magnitude and growth of the incidence and cost of treating neuromuscular diseases and injuries [

15], scientists and therapists have made great efforts to identify a suitable model to be used to study mechanisms involved in those afflictions. One of the models currently popular is a therapeutic method of transplanting mitochondria to the site of injury. Much evidence to date has supported the validity of using such a model to gain greater insight into the physiological goings-on during muscle damage and recovery from such insult [

12]. To date the understanding of the mechanisms of muscle damage caused by cardiotoxins such as BaCl

2 is that it weakens intracellular membranes causing rupture of those interior barriers thus releasing reactive oxygen species (ROS) from where they are produced inside the mitochondria into the cell’s cytoplasm causing further damage as a result [

15,

16,

17]). Preliminary studies have indicated that mitochondrial transplant therapy acts to resist intracellular membrane rupture thus holding in check further cellular damage [

16]. However, how such a supplement could enhance recovery from injury is less well understood. Of particular concern is the damage that is incurred by the cell’s NMJ as this synapse is recognized as being integral to the ability of muscle fibers to respond to electrical activation of the arriving neuronal impulse and generating the consequent contractile event of the excitation-coupling process that lies at the core of a functional neuromuscular system [

13]. To date however, it has proved elusive to determine whether the damage related to exposure to cardiotoxins, particularly BaCl

2, extends to the NMJ itself. Presently, we submit convincing evidence that injury caused by BaCl

2 promotes structural damage to the essential synapse connecting the neural impulse generated by the motor nerve system to the contractile function of skeletal muscle fibers of that same neuromuscular functional unit. Using a research design positioned to answer four unique and specific questions, it can be stated with confidence that BaCl

2 is, indeed, capable of promoting damage to the NMJ’s pre-synaptic machinery which generates neurotransmitter, stores it in vesicles at the active zones, and releases it into the synaptic cleft when necessary allowing neuromuscular transmission to occur [

17]. By applying only cardiotoxin and then examining the NMJ it was found that morphological characteristics typical of damaged NMJs such as greater fragmentation, or dispersion, of pre-synaptic vesicles were evident. Thus, exposure to BaCl

2 did, in fact, result in damage to the NMJ supporting the foundation of this project.

The second experiment pursued here examined the capacity of mitochondrial supplementation, or mitochondrial transplant therapy, to prevent damage to the NMJ following exposure to cardiotoxin or, alternatively, promote rapid recovery from the damage. It was found that by following exposure to BaCl2 with application of mitochondrial supplementation, within 1-2 weeks of such recuperative treatment, there were no longer any signs of structural damage to pre-synaptic branching, or post-synaptic endplate morphology. It may be said then that mitochondrial supplementation was effective in promoting repair caused by a toxic agent to skeletal muscle. More to the point, it can be concluded that this prophylactic effect occurred not only at the contractile elements of muscle, but also at the NMJ that is responsible for exciting that tissue causing it to twitch.

The next area of interest investigated by this project was whether, by itself, mitochondrial supplementation had any effect on morphology of healthy, uninjured NMJs. To determine this, mitochondrial supplementation was by itself applied to the sarcolemma of uninjured muscle tissue. When exposing healthy muscle tissue to the same mitochondrial agent used in previous experiments that showed consequent damage, it was revealed that no adaptation occurred. This was true at both of the pre-synaptic sites examined (nerve terminal branching, nerve terminal vesicles), as well as the post-synaptic endplate sites.

It is noteworthy that few structural adaptations were elicited in nerve terminal branching, or post-synaptic end plate regions. However, in unique measures employed to investigate pre- to post-synaptic coupling such as overlay between pre-synaptic vesicles and post-synaptic receptors (referred to as co-localization), and amount of branching per post-synaptic endplate area, both exhibited significant remodeling among treatment groups. In pre-to post-synaptic coupling, it was detected that muscles that were injured but then provided with the mitochondrial recuperative agent showed less coupling than the Control group. This generally suggests interference with synaptic transmission at the NMJ which in turn, would lead to less effective neuromuscular performance [

18]. Yet, the data also suggest that mitochondrial treatment re-established normal coupling upon its use. Similarly, in the coupling parameter assessed as amount of post-synaptic endplate area innervated by length of pre-synaptic nerve terminal branching at the NMJ was reduced among muscles that were damaged, but not treated with restorative agents. Although it is not clear why and how these two variables of coupling showed negative effects of the toxic agents applied, likely it is linked to the fact that the BaCl

2 affected pre- but not post-synaptic morphological features of NMJs thus altering normal pre- to post-synaptic ratios. Whatever the case, these rearrangements can be assumed to disturb neuromuscular transmission as the highly matched apposition between pre-synaptic release sites and post-synaptic receptor sites would have been disrupted from proper alignment, and or the numbers of vesicles relative to receptors may have been altered.

In summarizing the results presented here, it is fair to say that BaCl

2 , indeed did induce muscle damage mainly via disruption of the membrane surrounding the mitochondria thus releasing ROS into the cytoplasm causing DNA mutations and /or pH imbalances [

19]. This would be expected to disturb ATP production via the electron transport chain [

20], as well as interfere with essential metabolic pathways [

21]. There are, however, effective treatments to mitigate this damage. A primary prophylactic agent would be providing extra mitochondrial content to the damaged muscle as was done here. However, this is only a partial answer, further research is required , if additional information regarding the physiological mechanisms involved are to be fully elucidated. Finally, the data presented here demonstrate the impressive capacity of skeletal muscle – both the contractile and excitatory elements – to amply recover from damage it may incur. Again, this underscores the remarkable plasticity of the neuromuscular system and the synapse at its core.

Funding

Funding was provided by the Virginia Space Grant Consortium which had no role in the design of study, or the collection/interpretation of data.

Roles of Authors

Deschenes – conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, project administration, methodology, supervision, writing of original draft. Rackley – funding acquisition, investigation, visualization, data curation, resources. Fernandez – investigation, visualization, data curation, resources. Heidebrecht – data curation, visualization, investigation, methodology. Hamilton – investigation, visualization, resources, software. Paez – investigation. Pitzer – investigation Alway – project administration, conceptualization.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Graphic abstract

Image from confocal microscopy system along with fluorochromes displaying different pre- and post-synaptic components of the neuromuscular junction (i.e., pre-synaptic nerve terminals (green), pre-synaptic acetylcholine vesicles (blue), and post-synaptic receptors (red) that were affected by BaCl2 and remedied by supplementation with mitochondrial matter. The fact that the neuromuscular junction was sensitive to cardiotoxin and recuperative agents indicates that the entire neuromuscular system responds as a unit to those interventions, making it a good model with which to study injury to the myocardium and recovery from such damage.

References

- Janssen, I.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Wang, Z.M.; Ross, R. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18-88 yr. J Appl Physiol Bethesda Md 1985. 2000, 89, 81–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wernig, A.; Salvini, T.F.; Irintchev, A. Axonal sprouting and changes in fibre types after running-induced muscle damage. J Neurocytol. 1991, 20, 903–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Cruz, P.M.; Cossins, J.; Beeson, D.; Vincent, A. The Neuromuscular Junction in Health and Disease: Molecular Mechanisms Governing Synaptic Formation and Homeostasis. Front Mol Neurosci. 2020, 13, 610964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkindale, J.; Yang, W.; Hogan, P.F.; Simon, C.J.; Zhang, Y.; Jain, A.; et al. Cost of illness for neuromuscular diseases in the United States. Muscle Nerve. 2014, 49, 431–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delp, M.D.; Duan, C. Composition and size of type I, IIA, IID/X, and IIB fibers and citrate synthase activity of rat muscle. J Appl Physiol Bethesda Md 1985. 1996, 80, 261–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, J.; Fenoll, R.; Mayayo, E.; Santafé, M. Branching pattern of the motor nerve endings in a skeletal muscle of the adult rat. J Anat. 1990, 168, 123–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fahim, M.A. Rapid neuromuscular remodeling following limb immobilization. Anat Rec. 1989, 224, 102–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanes, J.R.; Lichtman, J.W. Development of the vertebrate neuromuscular junction. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1999, 22, 389–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanes, J.R.; Lichtman, J.W. Induction, assembly, maturation and maintenance of a postsynaptic apparatus. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001, 2, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, C.R. The Structure of Human Neuromuscular Junctions: Some Unanswered Molecular Questions. Int J Mol Sci. 2017, 18, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.J.; Slater, C.R. The contribution of postsynaptic folds to the safety factor for neuromuscular transmission in rat fast- and slow-twitch muscles. J Physiol. 1997, 500 Pt 1, 165–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alway, S.E.; Paez, H.G.; Pitzer, C.R.; Ferrandi, P.J.; Khan, M.M.; Mohamed, J.S.; et al. Mitochondria transplant therapy improves regeneration and restoration of injured skeletal muscle. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2023, 14, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, S.R.; Shah, S.B.; Lovering, R.M. The Neuromuscular Junction: Roles in Aging and Neuromuscular Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 8058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slater, C.R. The functional organization of motor nerve terminals. Prog Neurobiol. 2015, 134, 55–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2021 Nervous System Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 344–81.

- Nicolson, G.L.; Ferreira de Mattos, G. Membrane Lipid Replacement for reconstituting mitochondrial function and moderating cancer-related fatigue, pain and other symptoms while counteracting the adverse effects of cancer cytotoxic therapy. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2024, 41, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, C.R. Structural determinants of the reliability of synaptic transmission at the vertebrate neuromuscular junction. J Neurocytol. 2003, 32, 505–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, S.J.P.; Valencia, A.P.; Le, G.K.; Shah, S.B.; Lovering, R.M. Pre- and postsynaptic changes in the neuromuscular junction in dystrophic mice. Front Physiol. 2015, 6, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.E.; Hohorst, L.; García-Sáez, A.J. Expanding roles of BCL-2 proteins in apoptosis execution and beyond. J Cell Sci. 2023, 136, jcs260790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelen, M.P.; Wirth, B.; Kye, M.J. Mitochondrial defects in the respiratory complex I contribute to impaired translational initiation via ROS and energy homeostasis in SMA motor neurons. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020, 8, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst, R.; Huijbers, M.G.; Oury, J.; Burden, S.J. Building, Breaking, and Repairing Neuromuscular Synapses. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2024, 16, a041490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).