Submitted:

04 April 2025

Posted:

04 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

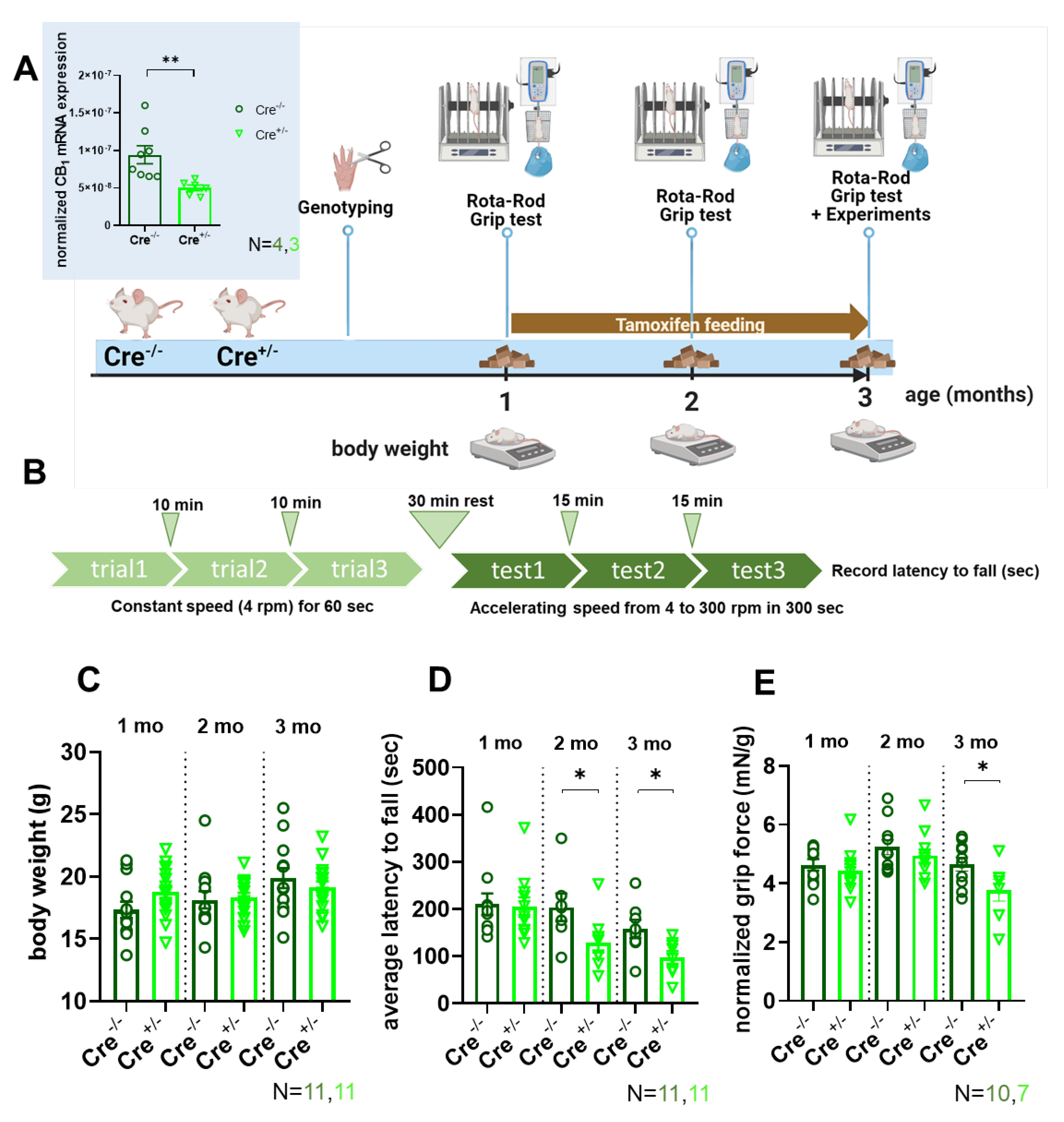

2.1. In Vivo Muscle Force and Motor Coordination are Depressed in skmCB1-KD Mice

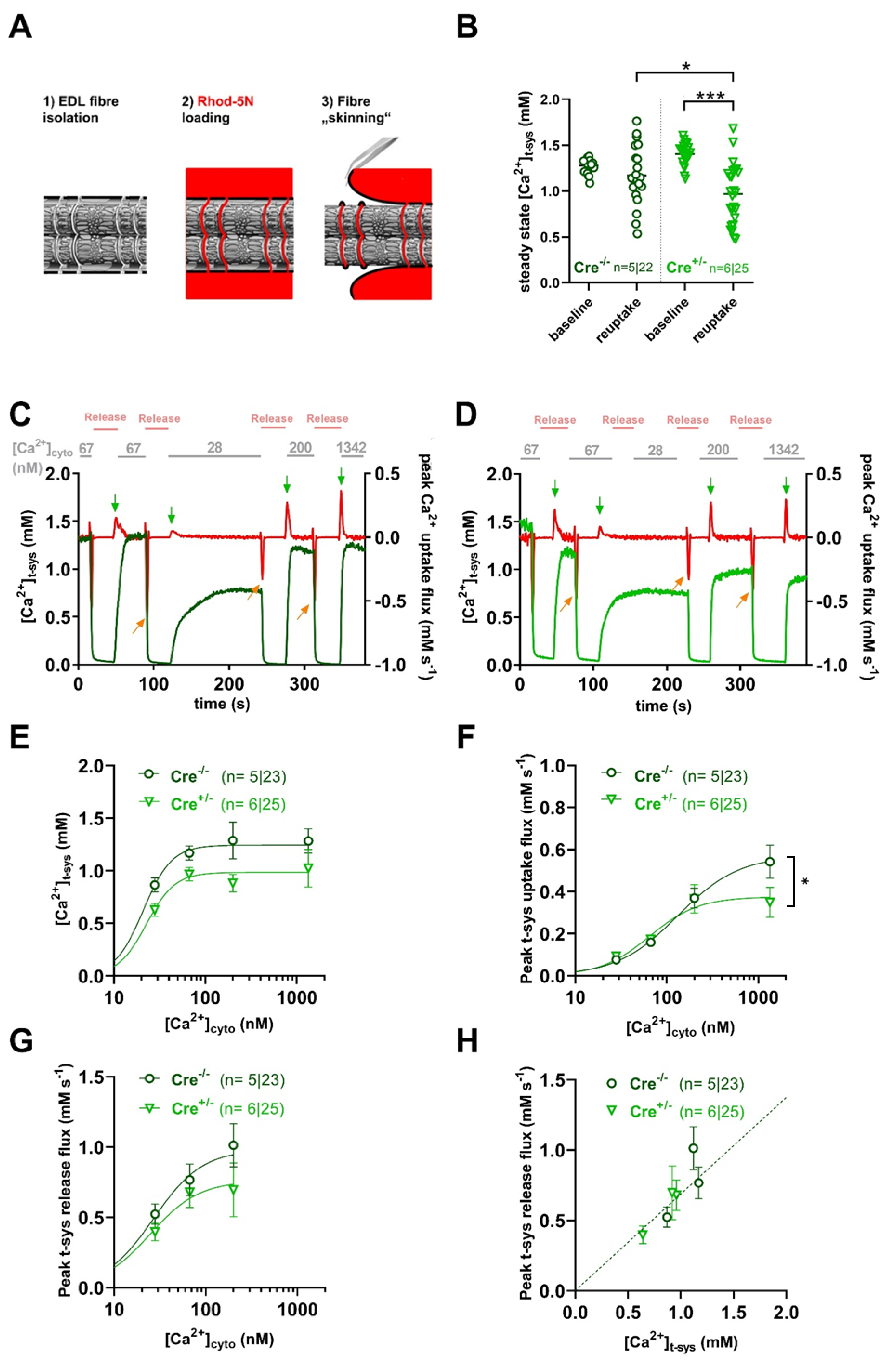

2.2. SOCE Activity is Preserved in skmCB1-KD Mice

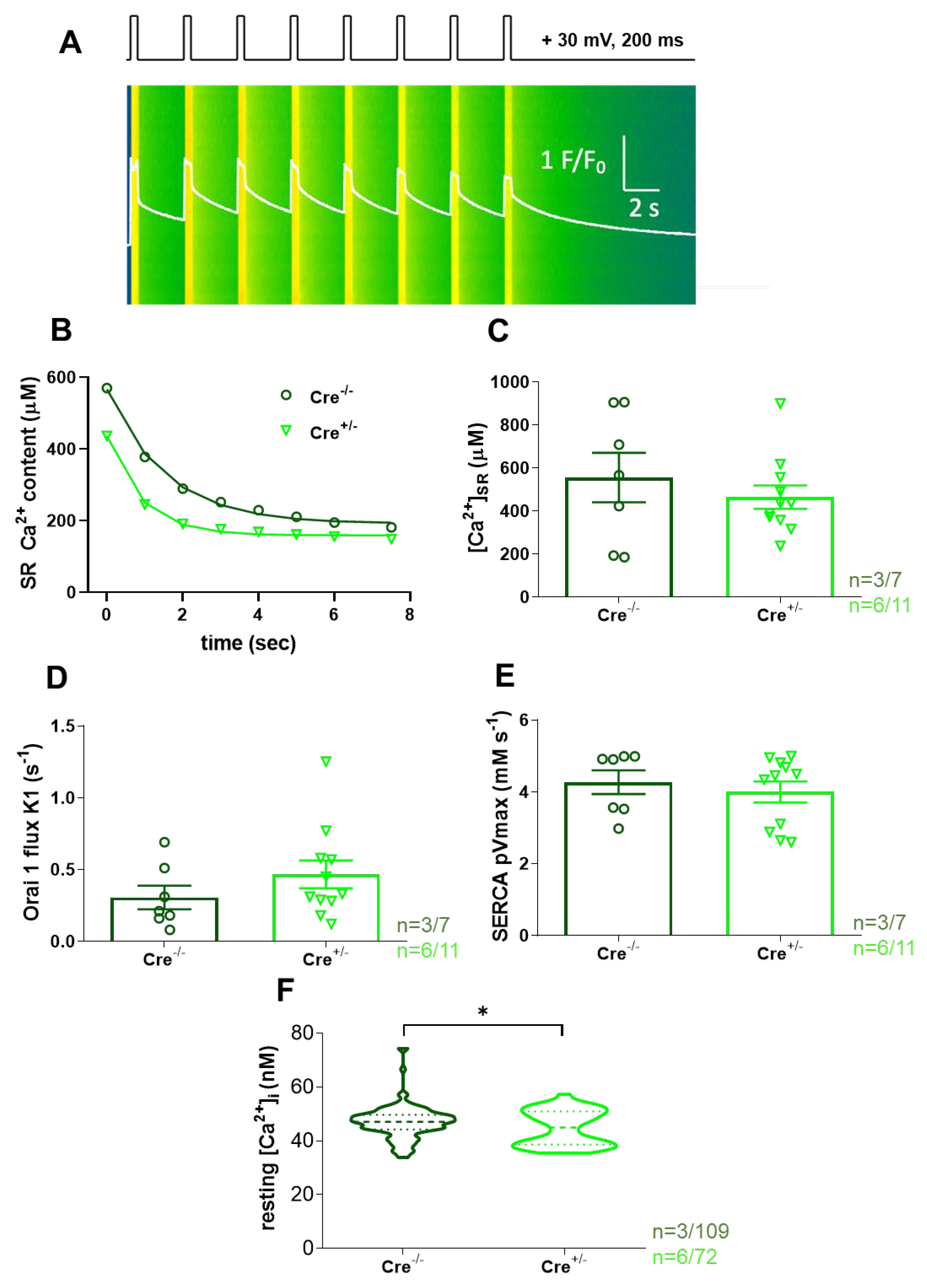

2.3. Calcium homeostasis Is Preserved in skmCB1-KD Mice

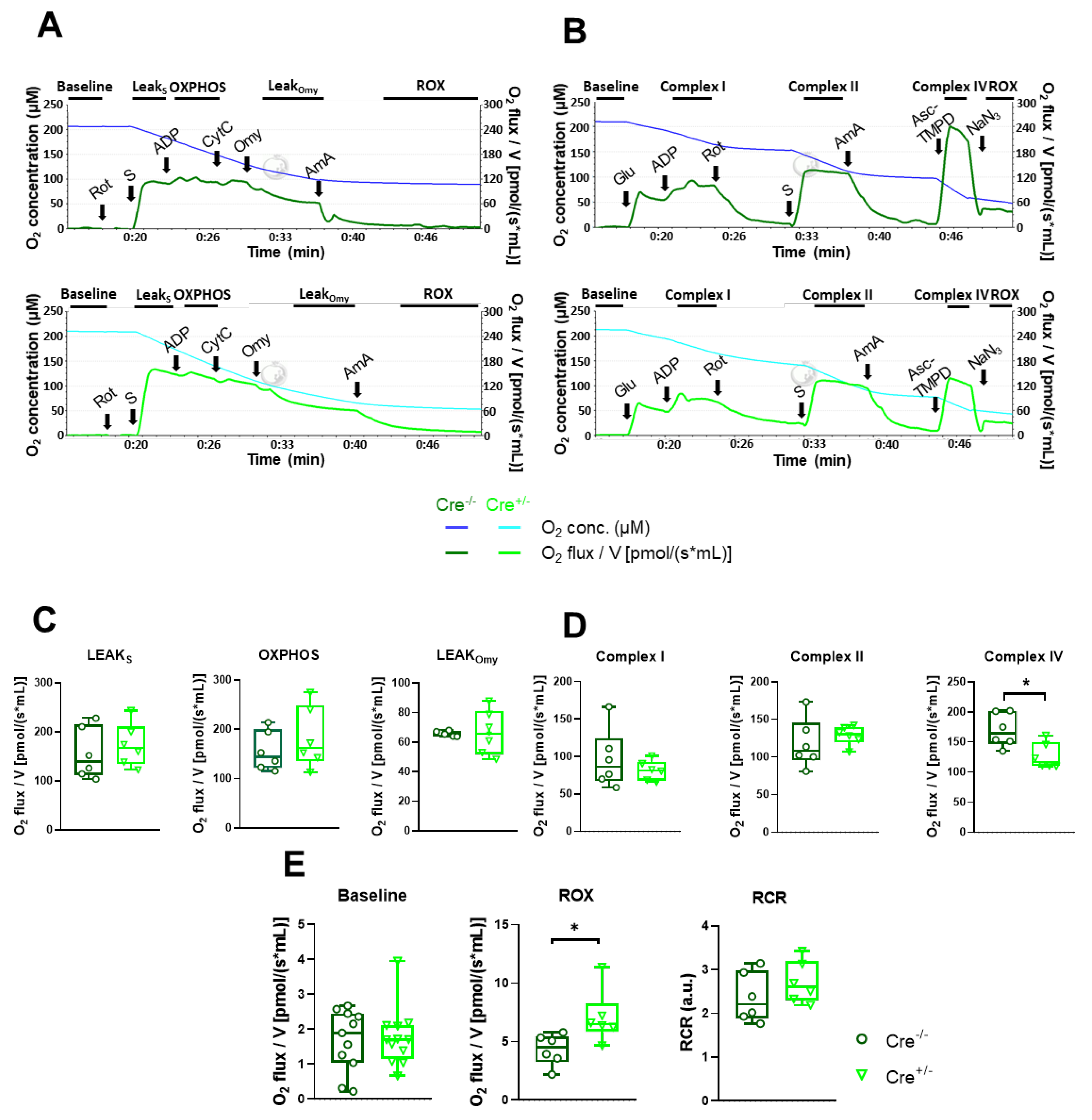

2.4. Mitochondrial Function Undergoes Modest Alterations in skmCB1-KD Mice

2.5. Mitochondrial Dynamics Marker Protein Levels are Preserved in skmCB1-KD Mice

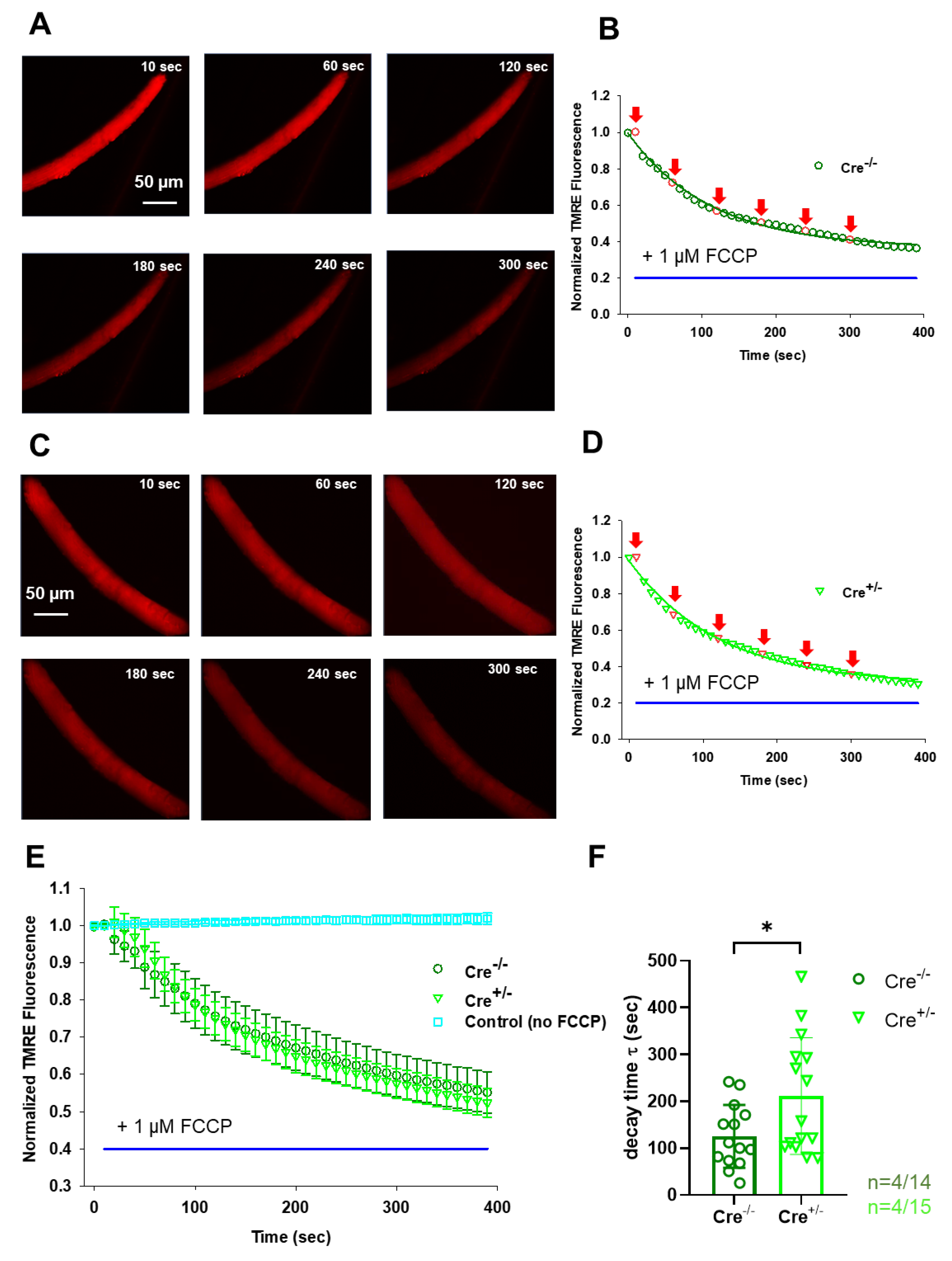

2.6. FCCP-Dependent Dissipation of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential is Delayed in skmCB1-KD Mice

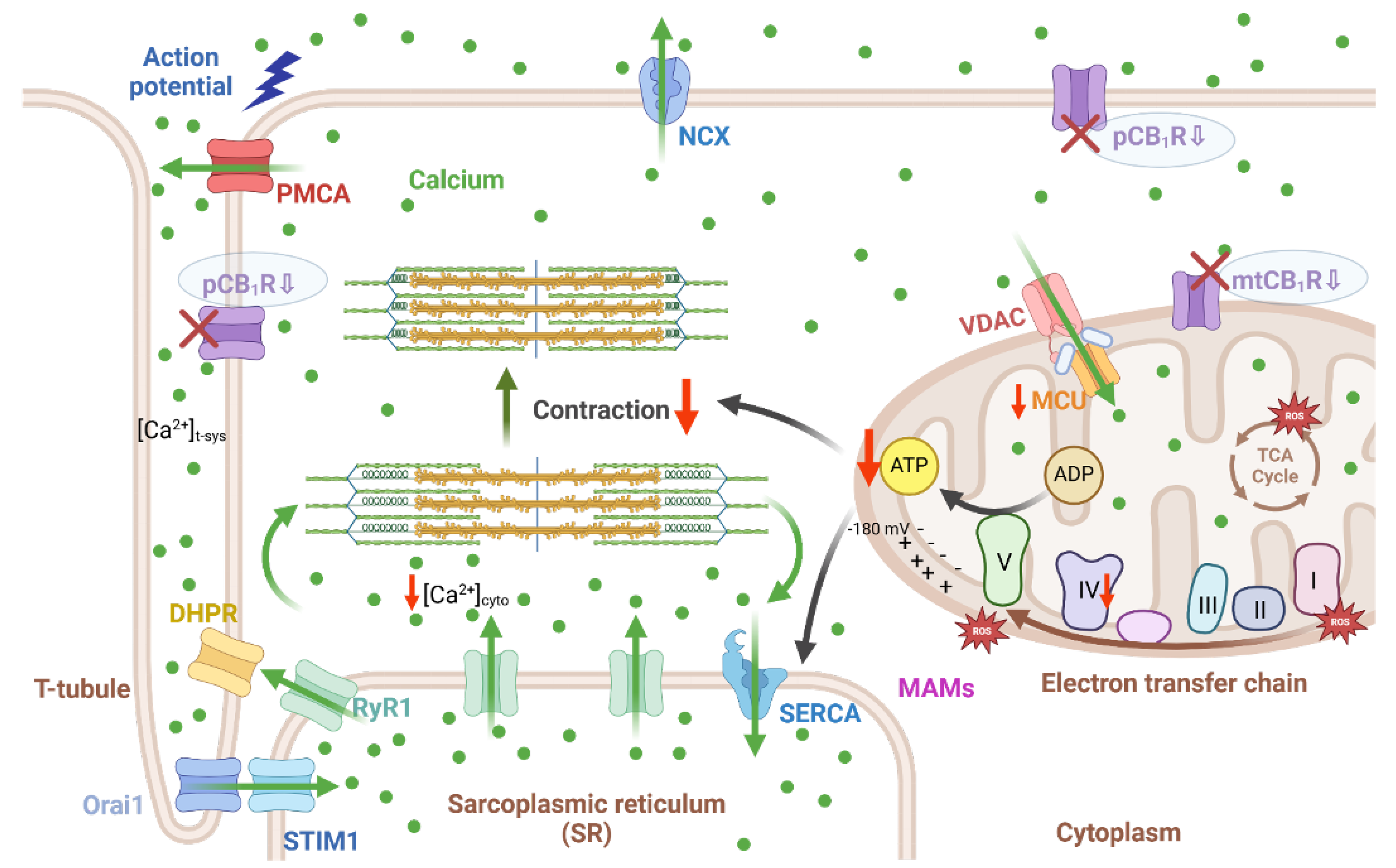

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Care

4.2. Generation of the Muscle-Specific CB1 Knockdown Mouse Strain

4.3. Tamoxifen Diet

4.4. Molecular Biology

4.4.1. Genotyping

4.4.2. Western Blot Analysis

4.5. In Vivo Experiments

4.5.1. Body Weight Measurement

4.5.2. Grip Strength Test

4.5.3. Rota-Rod Test

4.6. In Vitro Experiments

4.6.1. Isolation of Single FDB Fibres

4.6.2. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Measurement, Oxidative Stress Measurement, Confocal Microscopy, and Image Processing

4.6.3. Assessment of Mitochondrial Oxygen Consumption Using High-Resolution Respirometry

4.6.4. T-System Ca2+-Uptake Measurement

4.6.5. Resting Myoplasmic [Ca2+]i Measurement

4.6.6. Whole-Cell Voltage Clamp

4.6.7. External Bath Solution (in mM):

4.6.8. Internal (pipette) Solution (in mM):

4.7. Quantification and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolfe, R.R. The underappreciated role of muscle in health and disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, K.E.; Thurmond, D.C. Role of skeletal muscle in insulin resistance and glucose uptake. Compr. Physiol. 2020, 10, 785–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzini-Armstrong, C.; Jorgensen, A.O. Structure and development of E-C coupling units in skeletal muscle. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1994, 56, 509–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, G.; Lu, X. Dihydropyridine receptor-ryanodine receptor interactions in skeletal muscle excitation-contraction coupling. Biosci. Rep. 1995, 15, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, B.R. Quantitative Ultrastructure of Mammalian Skeletal Muscle. Compr. Physiol. 1983, 73–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcucci, L.; Canato, M.; Protasi, F.; Stienen, G.J.M.; Reggiani, C. A 3D diffusional-compartmental model of the calcium dynamics in cytosol, sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria of murine skeletal muscle fibers. PLoS One 2018, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzuto, R.; De Stefani, D.; Raffaello, A.; Mammucari, C. Mitochondria as sensors and regulators of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcucci, L.; Nogara, L.; Canato, M.; Germinario, E.; Raffaello, A.; Carraro, M.; Bernardi, P.; Pietrangelo, L.; Boncompagni, S.; Protasi, F.; et al. Mitochondria can substitute for parvalbumin to lower cytosolic calcium levels in the murine fast skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol. 2024, 240, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, G.; Vecellio Reane, D.; Canato, M.; Pietrangelo, L.; Boncompagni, S.; Protasi, F.; Rizzuto, R.; Reggiani, C.; Raffaello, A. Parvalbumin affects skeletal muscle trophism through modulation of mitochondrial calcium uptake. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launikonis, B.S.; Ríos, E. Store-operated Ca2+ entry during intracellular Ca2+ release in mammalian skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2007, 583, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feske, S.; Gwack, Y.; Prakriya, M.; Srikanth, S.; Puppel, S.-H.; Tanasa, B.; Hogan, P.G.; Lewis, R.S.; Daly, M.; Rao, A. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature 2006, 441, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liou, J.; Kim, M.L.; Heo, W. Do; Jones, J.T.; Myers, J.W.; Ferrell, J.E.J.; Meyer, T. STIM is a Ca2+ sensor essential for Ca2+-store-depletion-triggered Ca2+ influx. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 1235–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baba, Y.; Hayashi, K.; Fujii, Y.; Mizushima, A.; Watarai, H.; Wakamori, M.; Numaga, T.; Mori, Y.; Iino, M.; Hikida, M.; et al. Coupling of STIM1 to store-operated Ca2+ entry through its constitutive and inducible movement in the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 16704–16709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, X.; Choi, R.H.; Launikonis, B.S. Store-operated Ca2+ entry is activated by every action potential in skeletal muscle. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.L.; Yu, Y.; Roos, J.; Kozak, J.A.; Deerinck, T.J.; Ellisman, M.H.; Stauderman, K.A.; Cahalan, M.D. STIM1 is a Ca2+ sensor that activates CRAC channels and migrates from the Ca2+ store to the plasma membrane. Nature 2005, 437, 902–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onopiuk, M.; Brutkowski, W.; Young, C.; Krasowska, E.; Róg, J.; Ritso, M.; Wojciechowska, S.; Arkle, S.; Zabłocki, K.; Górecki, D.C. Store-operated calcium entry contributes to abnormal Ca2+ signalling in dystrophic mdx mouse myoblasts. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 569, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavuoto, P.; McAinch, A.J.; Hatzinikolas, G.; Janovská, A.; Game, P.; Wittert, G.A. The expression of receptors for endocannabinoids in human and rodent skeletal muscle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 364, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz de Azua, I.; Lutz, B. Multiple endocannabinoid-mediated mechanisms in the regulation of energy homeostasis in brain and peripheral tissues. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 1341–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marzo, V.; Stella, N.; Zimmer, A. Endocannabinoid signalling and the deteriorating brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagotto, U.; Marsicano, G.; Cota, D.; Lutz, B.; Pasquali, R. The emerging role of the endocannabinoid system in endocrine regulation and energy balance. Endocr. Rev. 2006, 27, 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, B.D.; Hébert, T.E.; Kelly, M.E. Physical and functional interaction between CB1 cannabinoid receptors and β2-adrenoceptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 160, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marzo, V.; Piscitelli, F. The Endocannabinoid System and its Modulation by Phytocannabinoids. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliaccio, M.; Ricci, G.; Suglia, A.; Manfrevola, F.; Mackie, K.; Fasano, S.; Pierantoni, R.; Chioccarelli, T.; Cobellis, G. Analysis of endocannabinoid system in rat testis during the first spermatogenetic wave. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, C.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Monsalves-Álvarez, M.; Donoso-Barraza, C.; Pino-de la Fuente, F.; Matías, I.; Leste-Lasserre, T.; Zizzari, P.; Morselli, E.; Cota, D.; et al. The CB1 cannabinoid receptor regulates autophagy in the tibialis anterior skeletal muscle in mice. Biol. Res. 2023, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckardt, K.; Sell, H.; Taube, A.; Koenen, M.; Platzbecker, B.; Cramer, A.; Horrighs, A.; Lehtonen, M.; Tennagels, N.; Eckel, J. Cannabinoid type 1 receptors in human skeletal muscle cells participate in the negative crosstalk between fat and muscle. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalle, S.; Schouten, M.; Deboutte, J.; de Lange, E.; Ramaekers, M.; Koppo, K. The molecular signature of the peripheral cannabinoid receptor 1 antagonist AM6545 in adipose, liver and muscle tissue. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2024, 491, 117081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert-Chatelain, E.; Desprez, T.; Serrat, R.; Bellocchio, L.; Soria-Gomez, E.; Busquets-Garcia, A.; Pagano Zottola, A.C.; Delamarre, A.; Cannich, A.; Vincent, P.; et al. A cannabinoid link between mitochondria and memory. Nature 2016, 539, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, I.; Proto, M.C.; Gazzerro, P.; Laezza, C.; Miele, C.; Alberobello, A.T.; D’Esposito, V.; Beguinot, F.; Formisano, P.; Bifulco, M. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant stimulates 2-deoxyglucose uptake in skeletal muscle cells by regulating the expression of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 74, 1678–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespillo, A.; Suárez, J.; Bermúdez-Silva, F.J.; Rivera, P.; Vida, M.; Alonso, M.; Palomino, A.; Lucena, M.A.; Serrano, A.; Pérez-Martín, M.; et al. Expression of the cannabinoid system in muscle: Effects of a high-fat diet and CB1 receptor blockade. Biochem. J. 2011, 433, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebert-Chatelain, E.; Reguero, L.; Puente, N.; Lutz, B.; Chaouloff, F.; Rossignol, R.; Piazza, P.V.; Benard, G.; Grandes, P.; Marsicano, G. Studying mitochondrial CB1 receptors: Yes we can. Mol. Metab. 2014, 3, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendizabal-Zubiaga, J.; Melser, S.; Bénard, G.; Ramos, A.; Reguero, L.; Arrabal, S.; Elezgarai, I.; Gerrikagoitia, I.; Suarez, J.; De Fonseca, F.R.; et al. Cannabinoid CB1 receptors are localized in striated muscle mitochondria and regulate mitochondrial respiration. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senese, R.; Petito, G.; Silvestri, E.; Ventriglia, M.; Mosca, N.; Potenza, N.; Russo, A.; Manfrevola, F.; Cobellis, G.; Chioccarelli, T.; et al. Effect of CB1 Receptor Deficiency on Mitochondrial Quality Control Pathways in Gastrocnemius Muscle. Biology (Basel). 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singlár, Z.; Ganbat, N.; Szentesi, P.; Osgonsandag, N.; Szabó, L.; Telek, A.; Fodor, J.; Dienes, B.; Gönczi, M.; Csernoch, L.; et al. Genetic Manipulation of CB1 Cannabinoid Receptors Reveals a Role in Maintaining Proper Skeletal Muscle Morphology and Function in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sztretye, M.; Geyer, N.; Vincze, J.; Al-Gaadi, D.; Oláh, T.; Szentesi, P.; Kis, G.; Antal, M.; Balatoni, I.; Csernoch, L.; et al. SOCE Is Important for Maintaining Sarcoplasmic Calcium Content and Release in Skeletal Muscle Fibers. Biophys. J. 2017, 113, 2496–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamboley, C.R.; Pearce, L.; Seng, C.; Meizoso-Huesca, A.; Singh, D.P.; Frankish, B.P.; Kaura, V.; Lo, H.P.; Ferguson, C.; Allen, P.D.; et al. Ryanodine receptor leak triggers fiber Ca(2+) redistribution to preserve force and elevate basal metabolism in skeletal muscle. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabi7166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cully, T.R.; Edwards, J.N.; Murphy, R.M.; Launikonis, B.S. A quantitative description of tubular system Ca2+ handling in fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 2795–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, G.D.; Stephenson, D.G. Measurement of force and calcium release using mechanically skinned fibers from mammalian skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 125, 1105–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cully, T.R.; Choi, R.H.; Bjorksten, A.R.; Stephenson, D.G.; Murphy, R.M.; Launikonis, B.S. Junctional membrane Ca(2+) dynamics in human muscle fibers are altered by malignant hyperthermia causative RyR mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 8215–8220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brini, M.; Carafoli, E. The plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase and the plasma membrane sodium calcium exchanger cooperate in the regulation of cell calcium. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oláh, T.; Bodnár, D.; Tóth, A.; Vincze, J.; Fodor, J.; Reischl, B.; Kovács, A.; Ruzsnavszky, O.; Dienes, B.; Szentesi, P.; et al. Cannabinoid signalling inhibits sarcoplasmic Ca2+ release and regulates excitation–contraction coupling in mammalian skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 7381–7398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mariscal, I.; Montoro, R.A.; O’Connel, J.F.; Kim, Y.; Gonzalez-Freire, M.; Liu, Q.R.; Alfaras, I.; Carlson, O.D.; Lehrmann, E.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Muscle cannabinoid 1 receptor regulates Il-6 and myostatin expression, governing physical performance and whole-body metabolism. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 5850–5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannotti, F.A.; Silvestri, C.; Mazzarella, E.; Martella, A.; Calvigioni, D.; Piscitelli, F.; Ambrosino, P.; Petrosino, S.; Czifra, G.; Bíró, T.; et al. The endocannabinoid 2-AG controls skeletal muscle cell differentiation via CB1 receptor-dependent inhibition of Kv7 channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, E2472–E2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaglianone, R.B.; Santos, A.T.; Bloise, F.F.; Ortiga-Carvalho, T.M.; Costa, M.L.; Quirico-Santos, T.; da Silva, W.S.; Mermelstein, C. Reduced mitochondrial respiration and increased calcium deposits in the EDL muscle, but not in soleus, from 12-week-old dystrophic mdx mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareedu, S.; Million, E.D.; Duan, D.; Babu, G.J. Abnormal Calcium Handling in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Mechanisms and Potential Therapies. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, X.; Choi, R.H.; Schicker, K.; Singh, D.P.; Hilber, K.; Launikonis, B.S. Mechanistic insights into store-operated Ca 2+ entry during excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Res. 2019, 1866, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, L.; Meizoso-Huesca, A.; Seng, C.; Lamboley, C.R.; Singh, D.P.; Launikonis, B.S. Ryanodine receptor activity and store-operated Ca2+ entry: Critical regulators of Ca2+ content and function in skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2023, 601, 4183–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleck, C.K.E.; Kim, Y.; Willingham, T.B.; Glancy, B. Subcellular connectomic analyses of energy networks in striated muscle. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbincius, J.F.; Elrod, J.W. Mitochondrial calcium exchange in physiology and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 893–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, F. MCU-Dependent mROS Generation Regulates Cell Metabolism and Cell Death Modulated by the AMPK/PGC-1α/SIRT3 Signaling Pathway. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 674986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallafacchina, G.; Zanin, S.; Rizzuto, R. Recent advances in the molecular mechanism of mitochondrial calcium uptake. F1000Research 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, G. IP3Rs and nSOCE—Tied Together at Two Ends. Contact 2024, 7, 25152564241231092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammucari, C.; Raffaello, A.; Vecellio Reane, D.; Gherardi, G.; De Mario, A.; Rizzuto, R. Mitochondrial calcium uptake in organ physiology: from molecular mechanism to animal models. Pflugers Arch. 2018, 470, 1165–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCommis, K.S.; Finck, B.N. Mitochondrial pyruvate transport: a historical perspective and future research directions. Biochem. J. 2015, 466, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova, A.; Wevers, A.; Navarro-Ledesma, S.; Pruimboom, L. Mitochondria: It is all about energy. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1114231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailloux, R.J. Teaching the fundamentals of electron transfer reactions in mitochondria and the production and detection of reactive oxygen species. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, L.; Valerio, A.; Cervino, C.; Cardile, A.; Pagano, C.; Vettor, R.; Pasquali, R.; Carruba, M.O.; Marsicano, G.; Lutz, B.; et al. Cannabinoid Type 1 Receptor Blockade Promotes Oxide Synthase Expression in White Adipocytes. Diabetes 2008, 57, 2028–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abán, C.E.; Accialini, P.L.; Etcheverry, T.; Leguizamón, G.F.; Martinez, N.A.; Farina, M.G. Crosstalk Between Nitric Oxide and Endocannabinoid Signaling Pathways in Normal and Pathological Placentation. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filadi, R.; Greotti, E.; Turacchio, G.; Luini, A.; Pozzan, T.; Pizzo, P. Mitofusin 2 ablation increases endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, E2174–E2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casellas-Díaz, S.; Larramona-Arcas, R.; Riqué-Pujol, G.; Tena-Morraja, P.; Müller-Sánchez, C.; Segarra-Mondejar, M.; Gavaldà-Navarro, A.; Villarroya, F.; Reina, M.; Martínez-Estrada, O.M.; et al. Mfn2 localization in the ER is necessary for its bioenergetic function and neuritic development. EMBO Rep. 2021, 22, e51954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.; Steenbergen, C. Regulation of Mitochondrial Ca(2+) Uptake. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2021, 83, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sztretye, M.; Singlár, Z.; Szabó, L.; Angyal, Á.; Balogh, N.; Vakilzadeh, F.; Szentesi, P.; Dienes, B.; Csernoch, L. Improved tetanic force and mitochondrial calcium homeostasis by astaxanthin treatment in mouse skeletal muscle. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cully, T.R.; Edwards, J.N.; Murphy, R.M.; Launikonis, B.S. A quantitative description of tubular system Ca2+ handling in fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 2795–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephenson, D.G.; Williams, D.A. Calcium-activated force responses in fast- and slow-twitch skinned muscle fibres of the rat at different temperatures. J. Physiol. 1981, 317, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grynkiewicz, G.; Poenie, M.; Tsien, R.Y. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 3440–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royer, L.; Pouvreau, S.; Ríos, E. Evolution and modulation of intracellular calcium release during long-lasting, depleting depolarization in mouse muscle. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 4609–4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzer, W.; Rios, E.; Schneider, M.F. A general procedure for determining the rate of calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum in skeletal muscle fibers. Biophys. J. 1987, 51, 849–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Cat. no. | Company | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| anti-Orai1 | MA5-15777 | Invitrogen | 1:500 |

| anti-STIM1 | AB-9870 | Sigma | 1:1000 |

| anti-PMCA | 5F10 | Abcam | 1:1000 |

| anti-VDAC | MA5-35349 | Invitrogen | 1:1000 |

| anti-MICU1 | PA5-77364 | Invitrogen | 1:200 |

| anti-Drp1 | C6C7 | Cell Signaling Technology | 1:1000 |

| anti-Mfn2 | D2D10 | Cell Signaling Technology | 1:1000 |

| anti-Opa1 | MA-16149 | Invitrogen | 1:1000 |

| anti-α-actinin | sc-166524 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | 1:1000 |

| anti-tubulin | T5168 | Sigma | 1:4000 |

| Name | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| MHCI | 5’-GAGTAGCTCTTGTGCTACCCAGC-3’ | 5’-AATTGCTTTATTCTGCTTCCACC-3’ |

| MHCIIA | 5’-GCAAGAAGCAGATCCAGAAAC-3’ | 5’-GGTCTTCTTCTGTCTGGTAAGTAAGC-3’ |

| MHCIIX | 5’-GCAACAGGAGATTTCTGACCTCAC-3’ | 5’-CCAGAGATGCCTCTGCTTC-3’ |

| 18s RNA | 5’-GGGAGCCTGAGAAACGGC-3’ | 5’-GGGTCGGGAGTGGGTAATTTT-3’ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).