Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects and Data Acquisition

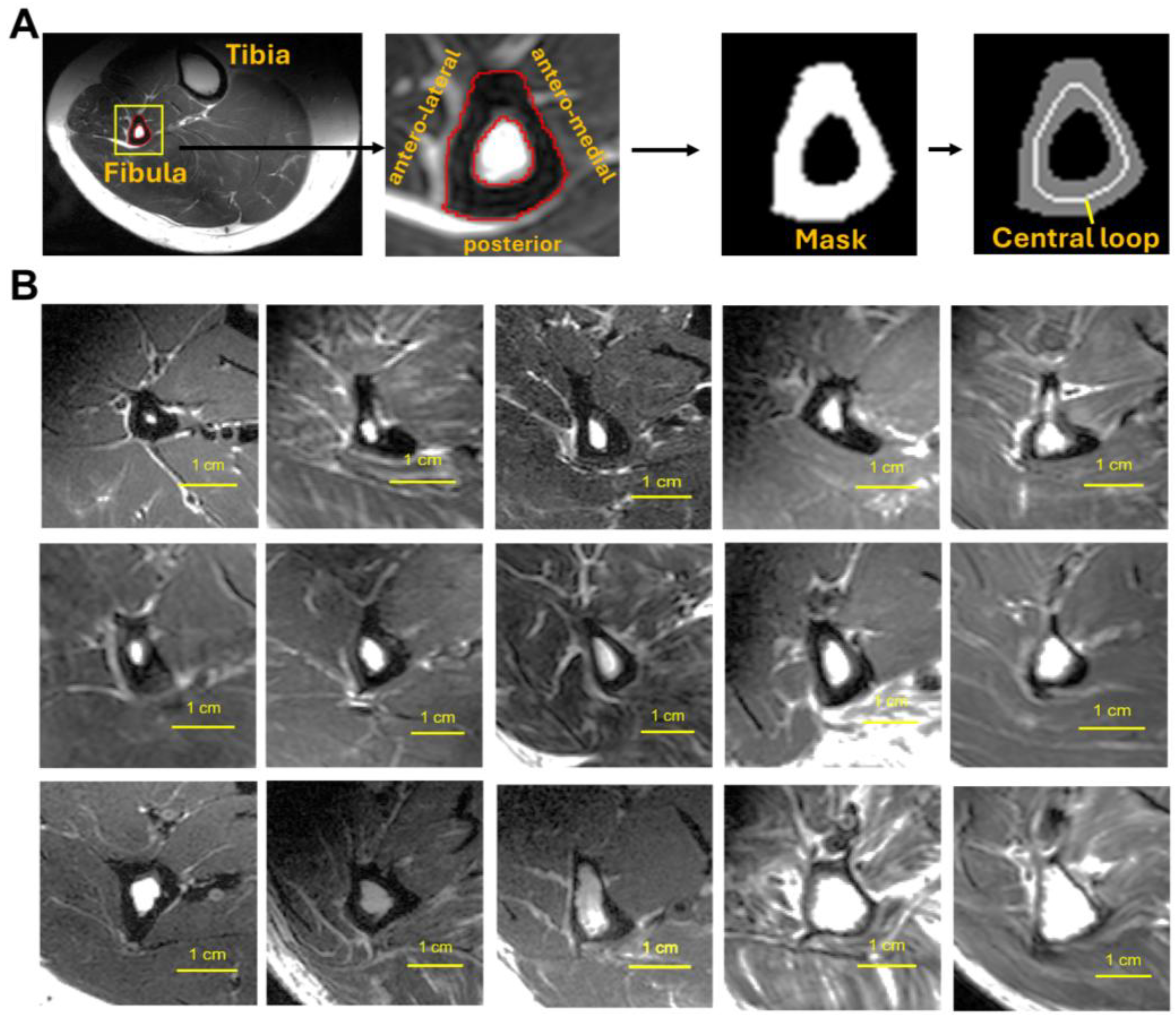

2.2. Data Processing and Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Size and Shape of Fibula Bone

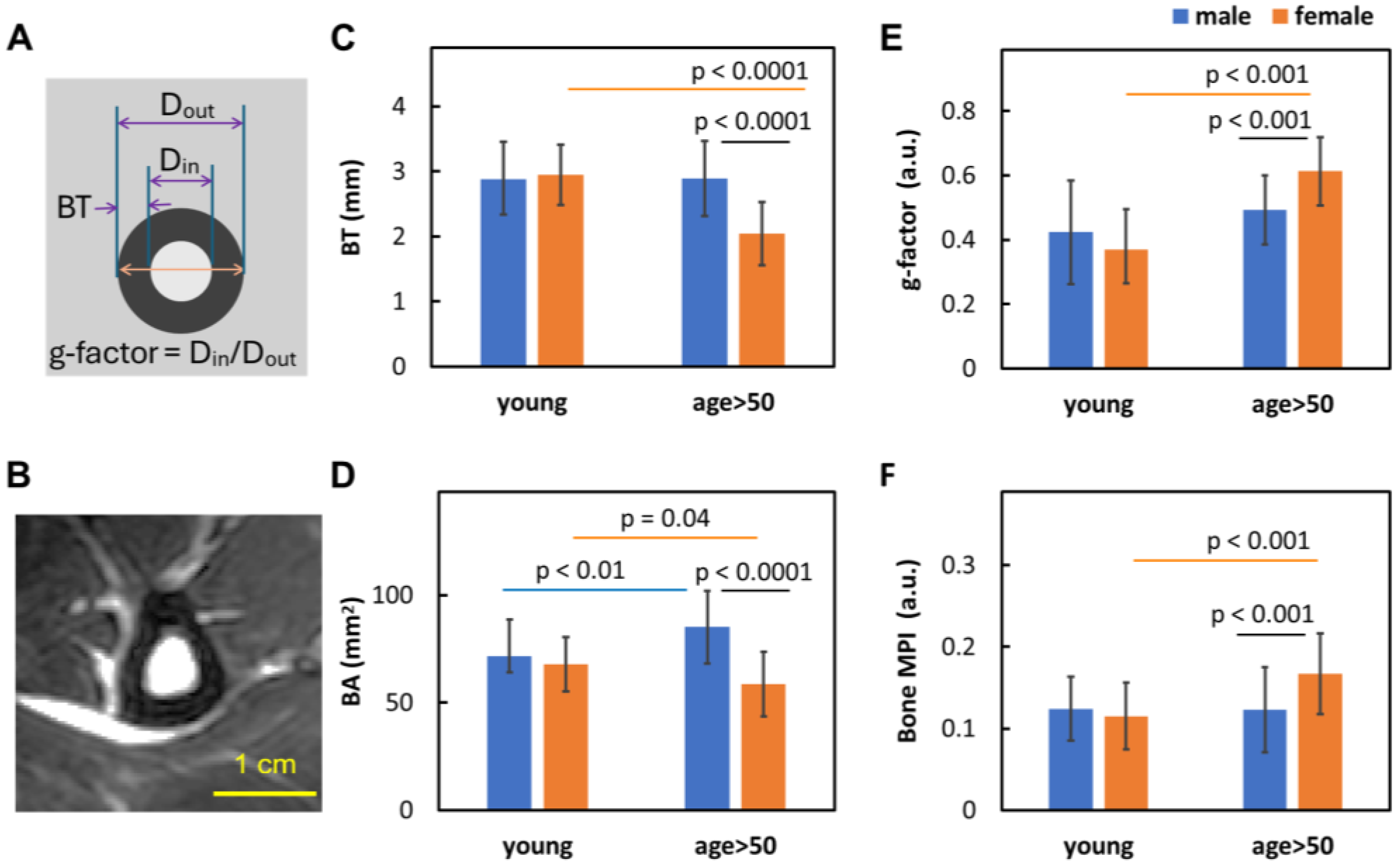

3.2. Sex Dependence of Bone Size and Density

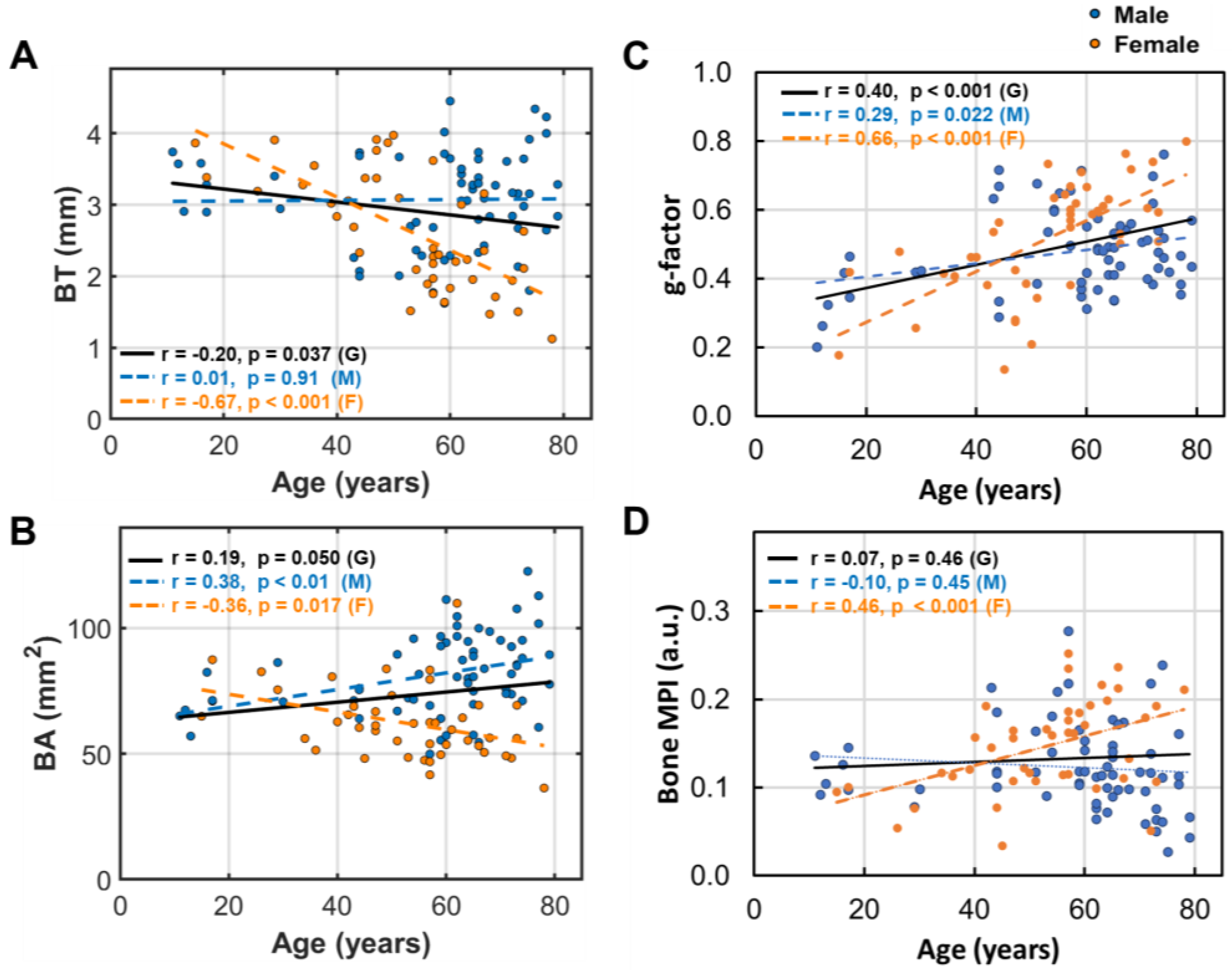

3.3. Age Dependence of Bone Size and Density

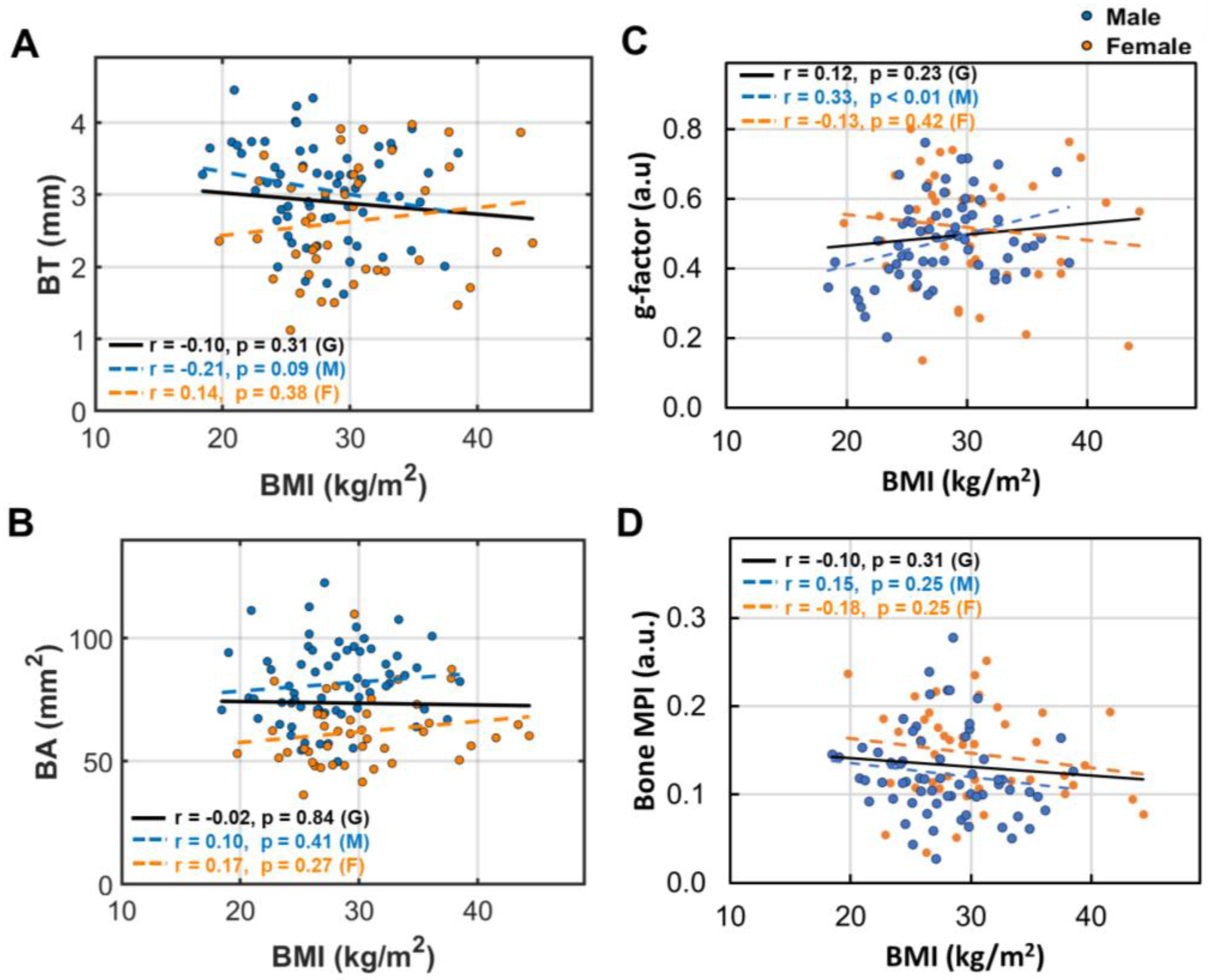

3.4. BMI Dependence of Bone Size and Density

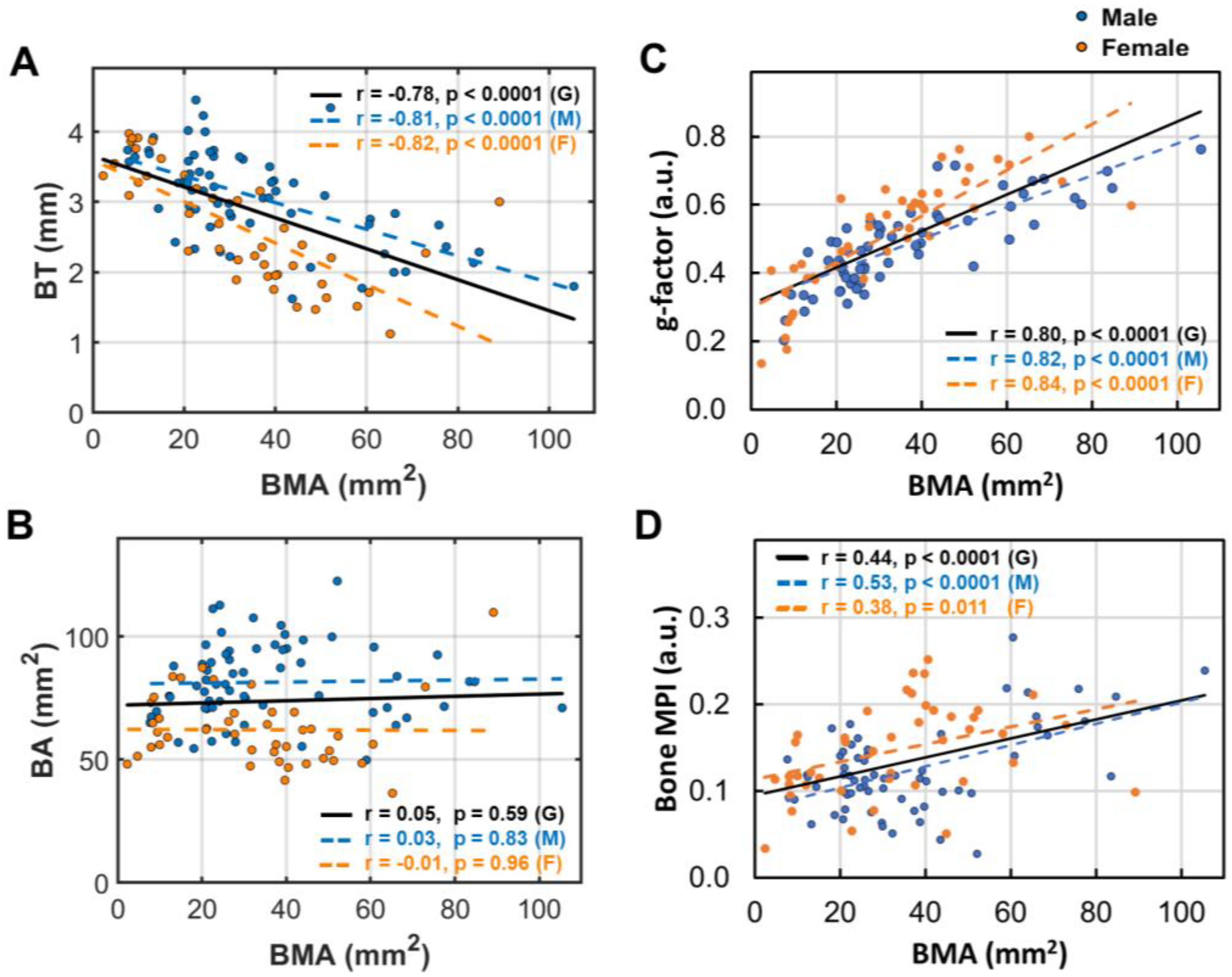

3.5. Bone Marrow’s Correlation with Bone Size and Density

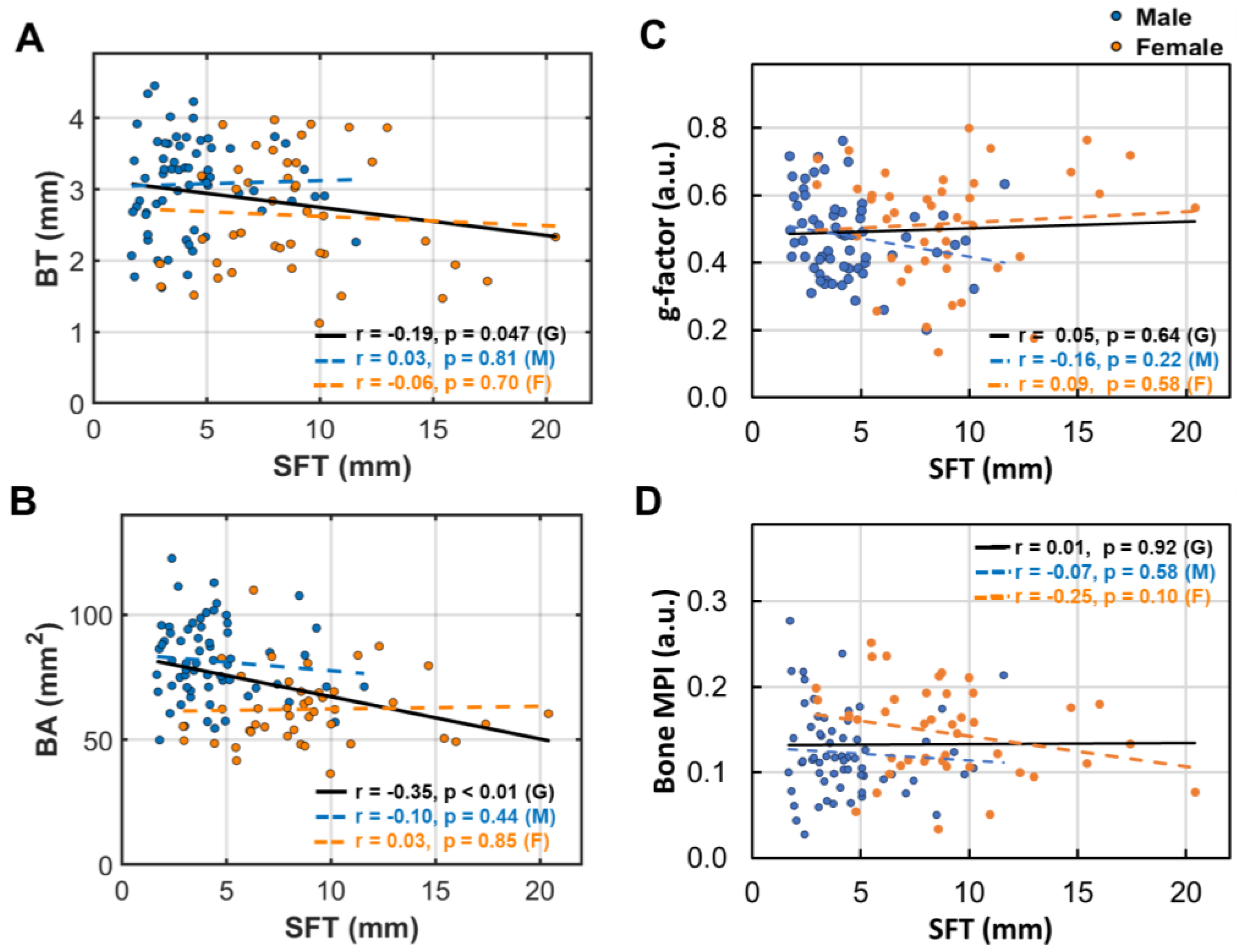

3.6. Subcutaneous Fat’s Correlation with Bone Size and Density

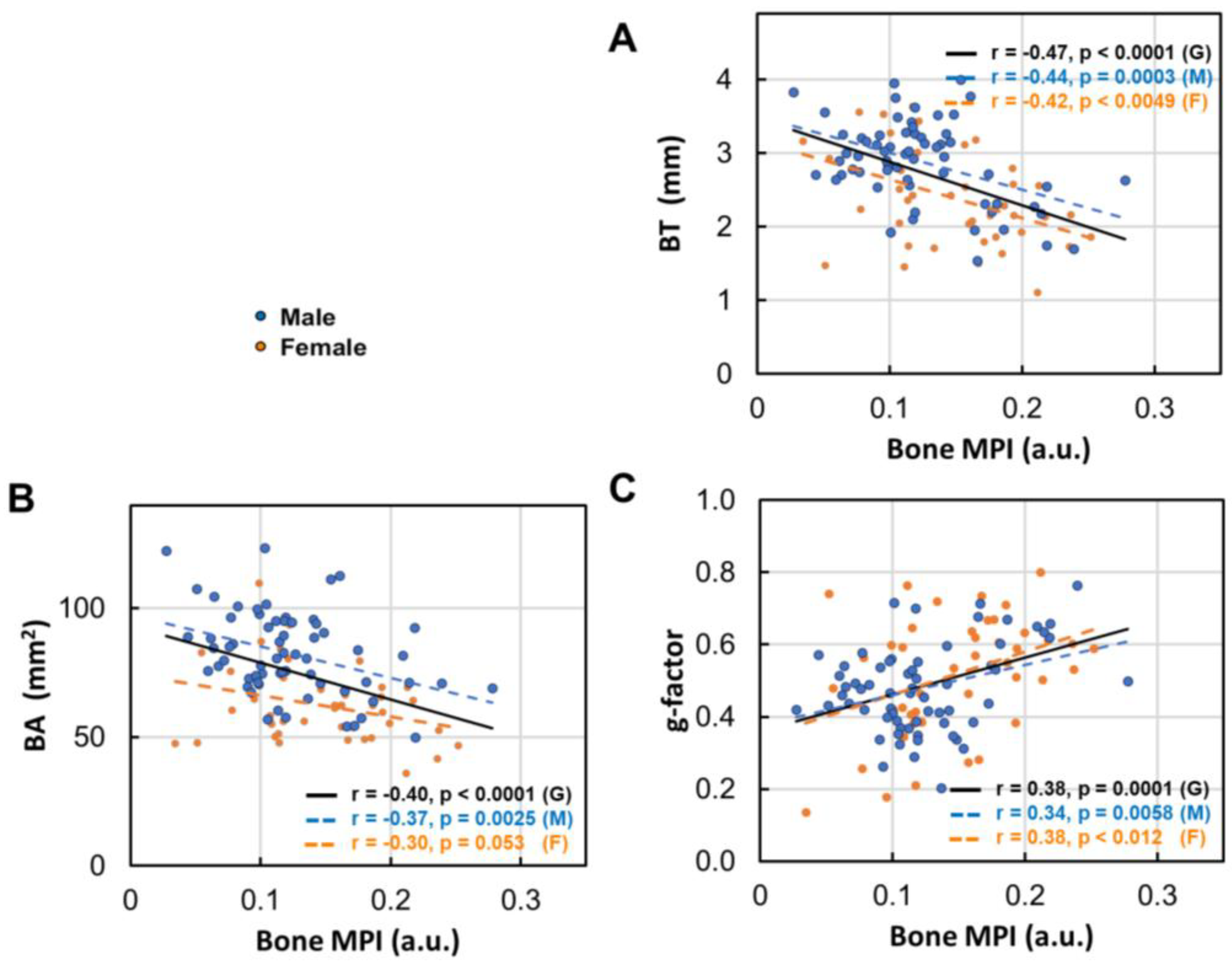

3.7. Bone Density Decrease in Correlation with Bone Size

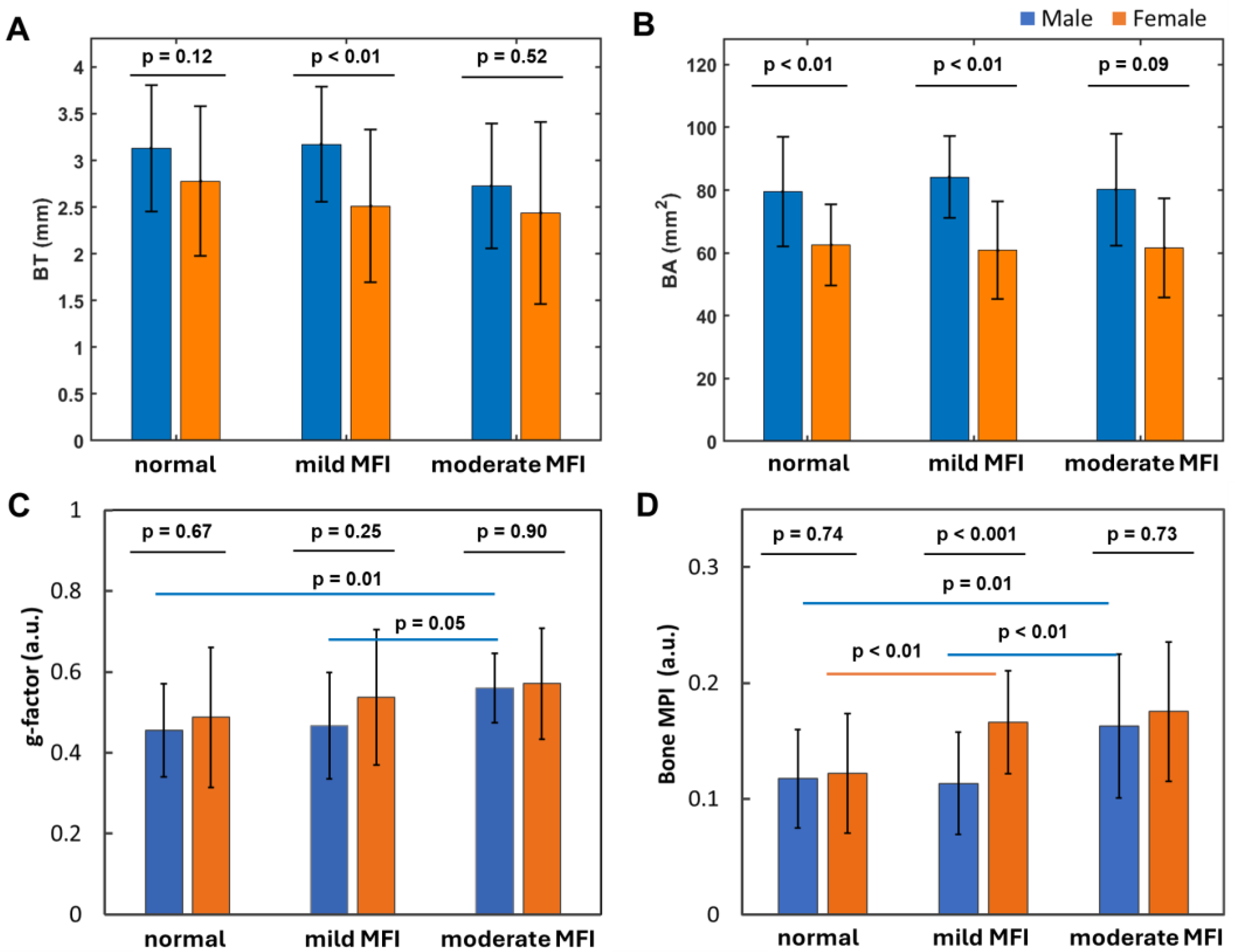

3.8. Muscle Fat Infiltration’s Correlation with Bone Size

3.9. Measurement Variations

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

- 1)

- Bone thinning and bone density loss are intricately linked, with a strong correlation that underscores their combined impact on skeletal health (Figure 7).

- 2)

- Women over 50 experience more pronounced bone thinning and bone density loss than their male counterparts in the same age group, highlighting the heightened vulnerability of women to bone loss with age (Figure 3A–D).

- 3)

- 4)

- Bone loss (BL), marked by decrease in bone thickness and density, is closely linked to bone marrow expansion (BME, Figure 5). Both BL and BME accelerate with age, yet remain largely unaffected by BMI (Figure 4, and ref [14]), suggesting that bone loss is primarily driven by the aging process rather than the direct effect of BMI increase.

- 5)

- Bone thickness and density are largely independent of subcutaneous fat thickness (SFT, Figure 6), although SFT decreases with age in men and increases with BMI in women [14]. Combined with key point #4, this suggests that bone loss is influenced not only by fat accumulation but also by the site of fat deposit with respect to the bone.

- 6)

- Bone loss tends to increase with muscle fat infiltration (MFI) (Figure 8). However, the detailed aspects of this bone-MFI relation are sex dependent, with bone area (BA) being more sensitive to MFI compared to bone thickness (BT). This likely reflects the anatomic relationship between bone and muscle.

4.2. Fat Distribution Matters

4.3. Aging Effects

4.4. Sex Matters

4.5. g-Factor

4.6. Other Remarks

4.7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hadjidakis, D.J.; Androulakis, I.I. Bone remodeling. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006, 1092, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raggatt, L.J.; Partridge, N.C. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of bone remodeling. J Biol Chem. 2010, 285, 25103–25108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefti, T.; Frischherz, M.; Spencer, N.D.; Hall, H.; Schlottig, F. A comparison of osteoclast resorption pits on bone with titanium and zirconia surfaces. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 7321–7331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murshed, M. Mechanism of Bone Mineralization. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018, 8, a031229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaguzel, G.; Holick, M.F. Diagnosis and treatment of osteopenia. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2010, 11, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnell, O.; Kanis, J.A. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006, 17, 1726–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaguzel, G.; Holick, M.F. Diagnosis and treatment of osteopenia. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2010, 11, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibson, C.L.; Tosteson, A.N.; Gabriel, S.E.; Ransom, J.E.; Melton, L.J. Mortality, disability, and nursing home use for persons with and without hip fracture: a population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002, 50, 1644–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Atkinson, E.J.; Jacobsen, S.J.; O’Fallon, W.M.; Melton, L.J., 3rd. Population-based study of survival after osteoporotic fractures. Am J Epidemiol. 1993, 137, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, P.; Su, Y.; Bai, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhao, J. Associations of muscle size and fatty infiltration with bone mineral density of the proximal femur bone. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 990487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.; Tencerova, M.; Figeac, F.; Kassem, M.; Jafari, A. The pathophysiology of osteoporosis in obesity and type 2 diabetes in aging women and men: The mechanisms and roles of increased bone marrow adiposity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 981487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulou, S.K.; Papadimitriou, K.; Voulgaridou, G.; Georgaki, E.; Tsotidou, E.; Zantidou, O.; Papandreou, D. Exercise and Nutrition Impact on Osteoporosis and Sarcopenia-The Incidence of Osteosarcopenia: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polito, A.; Barnaba, L.; Ciarapica, D.; Azzini, E. Osteosarcopenia: A Narrative Review on Clinical Studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 33, 5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.; Su, J.; Andres, J.; Henning, A.; Ren, J. Sex Differences in Fat Distribution and Muscle Fat Infiltration in the Lower Extremity: A Retrospective Diverse-Ethnicity 7T MRI Study in a Research Institute Setting in the USA. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrli, F.W.; Song, H.K.; Saha, P.K.; Wright, A.C. Quantitative MRI for the assessment of bone structure and function. NMR Biomed. 2006, 19, 731–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, G.; Boone, S.; Martel, D.; Rajapakse, C.S.; Hallyburton, R.S.; Valko, M.; Honig, S.; Regatte, R.R. MRI assessment of bone structure and microarchitecture. J Magn Reson Imaging 2017, 46, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.; Lee, S.W.; Suen, C.Y. Thinning methodologies-a comprehensive survey. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 1992, 14, 869–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-C.; Kashyap, R.L.; Chu, C.-N. Building skeleton models via 3-D medial surface/axis thinning algorithms. CVGIP: Graph. Models Image Process. 1994, 56, 462–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, C.R.; Qi, R.; Raghavan, V. A Linear Time Algorithm for Computing Exact Euclidean Distance Transforms of Binary Images in Arbitrary Dimensions. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2003, 25, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Gao, C.; Gao, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, M.; et al. Osteocytes regulate senescence of bone and bone marrow. Elife 2022, 11, e81480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan-Komito, D.; Swann, J.W.; Demetriou, P.; Cohen, E.S.; Horwood, N.J.; Sansom, S.N.; Griseri, T. GM-CSF drives dysregulated hematopoietic stem cell activity and pathogenic extramedullary myelopoiesis in experimental spondyloarthritis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, D.A.; McDonald, D.J.; Rice, N.P.; Haran, P.H.; Dolnikowski, G.G.; Fielding, R.A. Diminished anabolic signaling response to insulin induced by intramuscular lipid accumulation is associated with inflammation in aging but not obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2016, 310, R561–R569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justesen, J.; Stenderup, K.; Ebbesen, E.N.; Mosekilde, L.; Steiniche, T.; Kassem, M. Adipocyte tissue volume in bone marrow is increased with aging and in patients with osteoporosis. Biogerontology 2001, 2, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkastaris, K.; Goulis, D.G.; Potoupnis, M.; Anastasilakis, A.D.; Kapetanos, G.J. Musculoskelet Obesity, osteoporosis and bone metabolism. Neuronal Interact. 2020, 20, 372–381. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, P.; Gao, C.; Gao, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, M.; et al. Osteocytes regulate senescence of bone and bone marrow. Elife 2022, 11, e81480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsukasaki, M.; Takayanagi, H. Osteoimmunology: evolving concepts in bone-immune interactions in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019, 19, 626–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Hu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Ding, Y.; Yang, H.; He, F.; Gu, Q.; Shi, Q. Cellular senescence in skeletal disease: mechanisms and treatment. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2023, 28, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaron, N.; Costa, S.; Rosen, C.J.; Qiang, L. The Implications of Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue on Inflammaging. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 853765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pataky, M.W.; Young, W.F.; Nair, K.S. Hormonal and Metabolic Changes of Aging and the Influence of Lifestyle Modifications. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021, 96, 788–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, M.; Goyal, A.; Pathak, S.; Ganguly, P. Cellular Senescence and Inflammaging in the Bone: Pathways, Genetics, Anti-Aging Strategies and Interventions. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 7411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Zhang, C.; Lu, C.; Mo, C.; Zeng, J.; Yao, M.; Jia, B.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, P.; Xu, S. Age-related bone diseases: Role of inflammaging. J Autoimmun. 2024, 143, 103169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, A.; Bientinesi, E.; Monti, D. Immunosenescence and inflammaging in the aging process: age-related diseases or longevity? Ageing Res Rev. 2021, 71, 101422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldurthy, V.; Wei, R.; Oz, L.; Dhawan, P.; Jeon, Y.H.; Christakos, S. Vitamin D, calcium homeostasis and aging. Bone Res. 2016, 4, 16041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, E.; Litwic, A.; Cooper, C.; Dennison, E. Determinants of Muscle and Bone Aging. J Cell Physiol. 2015, 230, 2618–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geel, T.A.; Geusens, P.P.; Winkens, B.; Sels, J.P.; Dinant, G.J. Measures of bioavailable serum testosterone and estradiol and their relationships with muscle mass, muscle strength and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009, 160, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khosla, S.; Oursler, M.J.; Monroe, D.G. Estrogen and the skeleton. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012, 23, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, S. Update on estrogens and the skeleton. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010, 95, 3569–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamad, N.V.; Soelaiman, I.N.; Chin, K.Y. A concise review of testosterone and bone health. Clin Interv Aging 2016, 11, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looker, A.C.; Melton, L.J.; Harris, T.B.; Borrud, L.G.; Shepherd, J.A. Prevalence and trends in low femur bone density among older US adults: NHANES 2005-2006 compared with NHANES III. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whole-Body Vibration Therapy for Osteoporosis (ahrq.gov). Available online: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/osteoporosis-vibration-therapy_technical-brief.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Albrecht, B.M.; Stalling, I.; Recke, C.; Doerwald, F.; Bammann, K. Associations between older adults’ physical fitness level and their engagement in different types of physical activity: cross-sectional results from the OUTDOOR ACTIVE study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e068105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, D.A.; Williamson, S.; Han, B. Gender Differences in Physical Activity Associated with Urban Neighborhood Parks: Findings from the National Study of Neighborhood Parks. Womens Health Issues 2021, 31, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stikov, N.; Campbell, J.S.; Stroh, T.; Lavelée, M.; Frey, S.; Novek, J.; Nuara, S.; Ho, M.K.; Bedell, B.J.; Dougherty, R.F.; et al. In vivo histology of the myelin g-ratio with magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage 2015, 118, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, Q. Bone marrow brews central nervous system inflammation and autoimmunity. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, K.; Li, H.; Chang, T.; He, W.; Kong, Y.; Qi, C.; Li, R.; Huang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zheng, P.; et al. Bone marrow hematopoiesis drives multiple sclerosis progression. Cell 2022, 185, 2234–2247.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolabas, Z.I.; Kuemmerle, L.B.; Perneczky, R.; Förstera, B.; Ulukaya, S.; Ali, M.; Kapoor, S.; Bartos, L.M.; Büttner, M.; Caliskan, O.S.; et al. Distinct molecular profiles of skull bone marrow in health and neurological disorders. Cell 2023, 186, 3706–3725.e3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzitelli, J.A.; Pulous, F.E.; Smyth, L.C.D.; Kaya, Z.; Rustenhoven, J.; Moskowitz, M.A.; Kipnis, J.; Nahrendorf, M. Skull bone marrow channels as immune gateways to the central nervous system. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 2052–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardy, A.L.; Pouteau, E.; Marquez, D.; Yilmaz, C.; Scholey, A. Vitamins and Minerals for Energy, Fatigue and Cognition: A Narrative Review of the Biochemical and Clinical Evidence. Nutrients 2020, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peter Dornhofer; Jesse Z. Kellar. Intraosseous Vascular Access. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554373/ (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Ren, J.; Yang, B.; Sherry, A.D.; Malloy, C.R. Exchange kinetics by inversion transfer: integrated analysis of the phosphorus metabolite kinetic exchanges in resting human skeletal muscle at 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2015, 73, 1359–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Sherry, A.D. Malloy CR Modular 31 P wideband inversion transfer for integrative analysis of adenosine triphosphate metabolism, T1 relaxation and molecular dynamics in skeletal muscle at 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2019, 81, 3440–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Dimitrov, I.; Sherry, A.D.; Malloy, C.R. Composition of adipose tissue and marrow fat in humans by 1H NMR at 7 Tesla. J Lipid Res. 2008, 49, 2055–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongpatanasin, W.; Giacona, J.M.; Pittman, D.; Murillo, A.; Khan, G.; Wang, J.; Johnson, T.; Ren, J.; Moe, O.W.; Pak, C.C.Y. Potassium Magnesium Citrate Is Superior to Potassium Chloride in Reversing Metabolic Side Effects of Chlorthalidone. Hypertension 2023, 80, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacona, J.M.; Afridi, A.; Bezan Petric, U.; Johnson, T.; Pastor, J.; Ren, J.; Sandon, L.; Malloy, C.; Pandey, A.; Shah, A.; Berry, J.D.; Moe, O.W. Vongpatanasin W. Association between dietary phosphate intake and skeletal muscle energetics in adults without cardiovascular disease. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2024, 136, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Rodriguez, L., 2nd; Johnson, T.; Henning, A.; Dhaher, Y.Y. 17β-Estradiol Effects in Skeletal Muscle: A 31P MR Spectroscopic Imaging (MRSI) Study of Young Females during Early Follicular (EF) and Peri-Ovulation (PO) Phases. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sönmez, T.T.; Prescher, A.; Salama, A.; Kanatas, A.; Zor, F.; Mitchell, D.; Zaker Shahrak, A.; Karaaltin, M.V.; Knobe, M.; Külahci, Y.; et al. Comparative clinicoanatomical study of ilium and fibula as two commonly used bony donor sites for maxillofacial reconstruction. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013, 51, 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).