Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Radiotherapy

2.3. Chemotherapy

2.4. Follow-Up

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

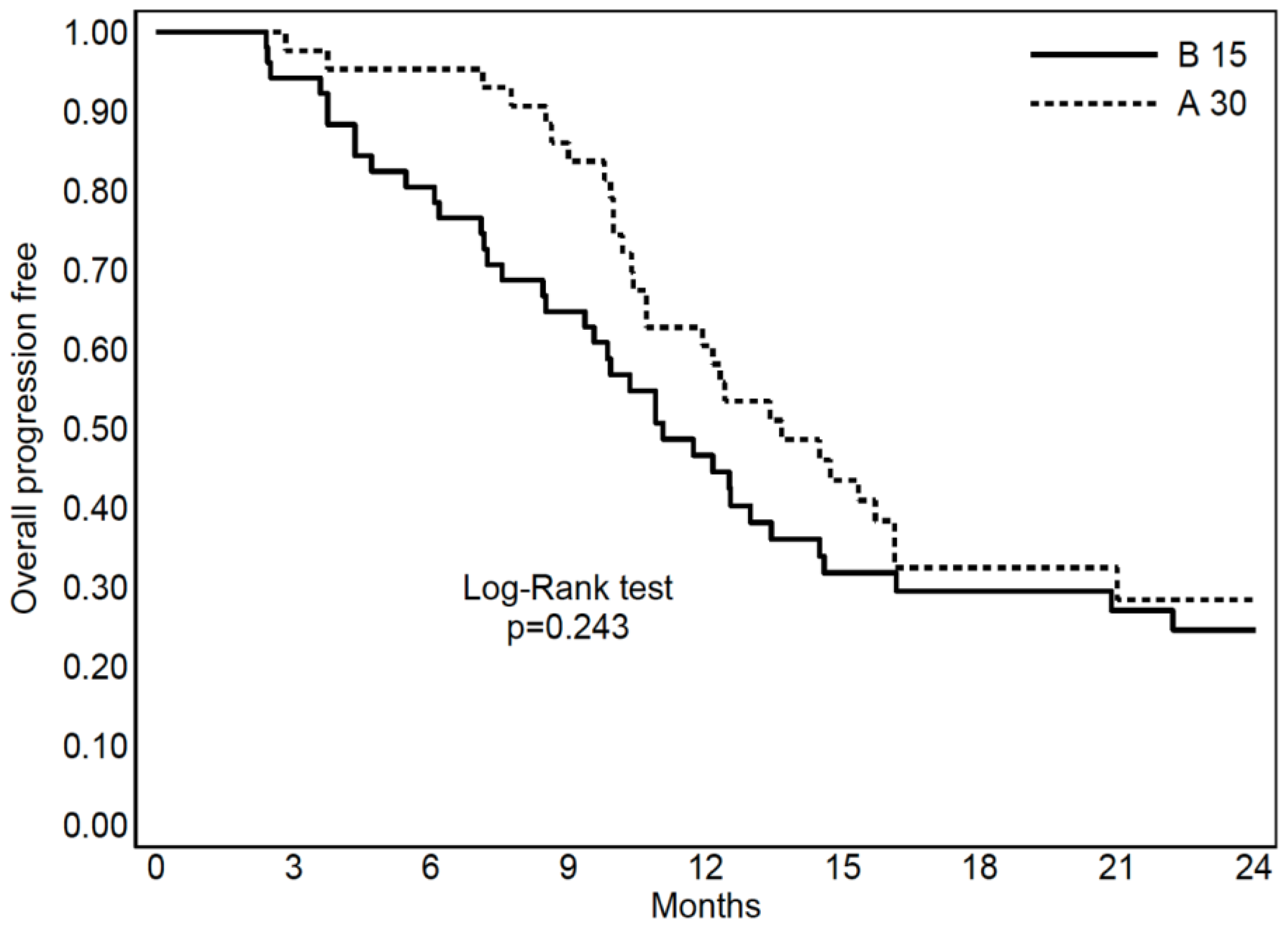

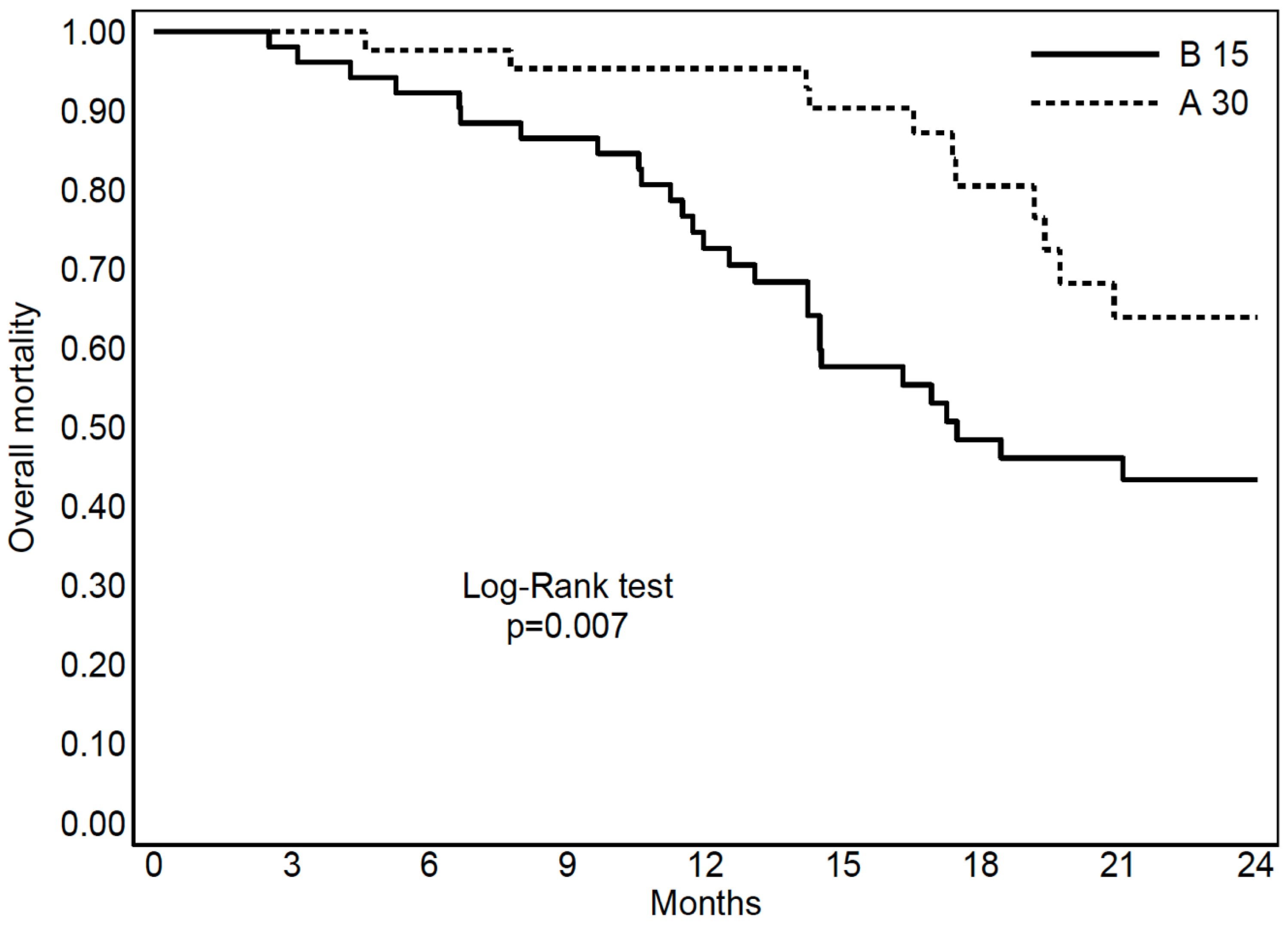

3.2. Prognostic Factors for OS and PFS

3.3. S-RT Versus Hypo-RT

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schaff LR, Mellinghoff IK. Glioblastoma and Other Primary Brain Malignancies in Adults: A Review (2023). JAMA. Feb 21;329(7):574-587.

- Wen PY, Weller M, Lee EQ, Alexander BM, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Barthel FP, Batchelor TT, Bindra RS, Chang SM, Chiocca EA, Cloughesy TF, DeGroot JF, Galanis E, Gilbert MR, Hegi ME, Horbinski C, Huang RY, Lassman AB, Le Rhun E, Lim M, Mehta MP, Mellinghoff IK, Minniti G, Nathanson D, Platten M, Preusser M, Roth P, Sanson M, Schiff D, Short SC, Taphoorn MJB, Tonn JC, Tsang J, Verhaak RGW, von Deimling A, Wick W, Zadeh G, Reardon DA, Aldape KD, van den Bent MJ (2020). Glioblastoma in adults: a Society for Neuro-Oncology (SNO) and European Society of Neuro-Oncology (EANO) consensus review on current management and future directions Neuro-Oncology 22(8), 1073–1113, 1073. [CrossRef]

- Park YW, Vollmuth P, Foltyn-Dumitru M, Sahm F, Choi KS, Park JE, Ahn SS, Chang JH, Kim SH (2023). The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: clinical implications. J Magn Reson Imaging. 58(6):1680-1702.

- Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Allgeier A, Fisher B, Belanger K, Hau P, Brandes AA, Gijtenbeek J, Marosi C, Vecht CJ, Mokhtari K, Wesseling P, Villa S, Eisenhauer E, Gorlia T, Weller M, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Mirimanoff RO (2009). Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomized phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol; 10(5):459–466.

- Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, Ludwin SK, Allgeier A, Fisher B, Belanger K, Hau P, Brandes AA, Gijtenbeek J, Marosi C, Vecht CJ, Mokhtari K, Wesseling P, Villa S, Eisenhauer E, Gorlia T, Weller M, Lacombe D, Cairncross JG, Mirimanoff RO; European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Brain Tumour and Radiation Oncology Groups; National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (2009). Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomized phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial. Lancet Oncol;10(5):459-66. [CrossRef]

- Malmström, A.; Grønberg, B.H.; Marosi, C.; Stupp, R.; Frappaz, D.; Schultz, H.; Abacioglu, U.; Tavelin, B.; Lhermitte, B.; Hegi, M.E.; et al. (2012). Temozolomide versus standard 6-week radiotherapy versus hypofractionated radiotherapy in patients older than 60 years with glioblastoma: The Nordic randomized, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol; 13, 916–926.

- Perry JR, Laperriere N, O’Callaghan CJ, Brandes AA, Menten J, Phillips C, Fay M, Nishikawa R, Cairncross JG, Roa W, Osoba D, Rossiter JP, Sahgal A, Hirte H, Laigle-Donadey F, Franceschi E, Chinot O, Golfinopoulos V, Fariselli L, Wick A, Feuvret L, Back M, Tills M, Winch C, Baumert BG, Wick W, Ding K, Mason WP; Trial Investigators (2017). Short-Course Radiation plus Temozolomide in Elderly Patients with Glioblastoma. N Engl J Med;376(11):1027-1037. [CrossRef]

- Roa, W.; Kepka, L.; Kumar, N.; Sinaika, V.; Matiello, J.; Lomidze, D.; Hentati, D.; Guedes de Castro, D.; Dyttus-Cebulok, K.; Drodge, S.; et al. (2015). International Atomic Energy Agency Randomized Phase III Study of Radiation Therapy in Elderly and/or Frail Patients With Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma Multiforme. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 4145–4150.

- Balducci, M.; Apicella, G.; Manfrida, S.; Mangiola, A.; Fiorentino, A.; Azario, L.; D’Agostino, G.R.; Frascino, V.; Dinapoli, N.; Mantini, G.; et al. (2010). Single- Arm Phase II Study of Conformal Radiation Therapy and Temozolomide plus fractionated Stereotactic Conformal Boost in High grade Gliomas. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie; 186, 558–564.

- Niyazi M, Andratschke N, Bendszus M, Chalmers AJ, Erridge SC, Galldiks N, Lagerwaard FJ, Navarria P, Munck Af Rosenschöld P, Ricardi U, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Belka C, Minniti G (2023). ESTRO-EANO guideline on target delineation and radiotherapy details for glioblastoma Radiother Oncol;184:109663. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Fraass, B.A.; Marsh, L.H.; Herbort, K.; Gebarski, S.S.; Martel, M.K.; Radany, E.H.; Lichter, A.S.; Sandler, H. M (1999). Patterns of failure following high-dose 3-D conformal radiotherapy for high-grade astrocytomas: A quantitative dosimetric study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys, 43, 79–88.

- Scoccianti, S.; Krengli, M.; Marrazzo, L.; Magrini, S.M.; Detti, B.; Fusco, V.; Pirtoli, L.; Doino, D.; Fiorentino, A.; Masini, L.; et al. (2018). Hypofractionated radiotherapy with simultaneous integrated boost (SIB) plus temozolomide in good prognosis patients with glioblastoma: A multicenter phase II study by the Brain Study Group of the Italian Association of Radiation Oncology (AIRO). Radiol. Med; 123, 48–62.

- Jablonska, P.A.; Diez-Valle, R.; Pérez-Larraya, J.G.; Moreno-Jiménez, M.; Idoate, M.Á.; Arbea, L.; Tejada, S.; Garcia de Eulate, M.R.; Ramos, L.; Arbizu, J.; et al. (2019). Hypofractionated radiation therapy and temozolomide in patients with glioblastoma and poor prognostic factors. A prospective, single-institution experience. PLoS ONE;14, e0217881.

- Navarria, P.; Pessina, F.; Cozzi, L.; Tomatis, S.; Reggiori, G.; Simonelli, M.; Santoro, A.; Clerici, E.; Franzese, C.; Carta, G.; et al. (2019). Phase II study of hypofractionated radiation therapy in elderly patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma with poor prognosis. Tumori; 105, 47–54.

- Minniti, G.; Scaringi, C.; Lanzetta, G.; Terrenato, I.; Esposito, V.; Arcella, A.; Pace, A.; Giangaspero, F.; Bozzao, A.; Enrici, R. M (2015). Standard (60 Gy) or short-course (40 Gy) irradiation plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for elderly patients with glioblastoma: A propensity-matched analysis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys; 91, 109–115.

- Pedretti, S.; Masini, L.; Turco, E.; Triggiani, L.; Krengli, M.; Meduri, B.; Pirtoli, L.; Borghetti, P.; Pegurri, L.; Riva, N.; et al. (2019). Hypofractionated radiation therapy versus chemotherapy with temozolomide in patients affected by RPA class V and VI glioblastoma: A randomized phase II trial. J. Neurooncol; 143, 447–455.

- Gregucci F, Surgo A, Bonaparte I, Laera L, Ciliberti MP, Carbonara R, Gentile MA, Giraldi D, Calbi R, Caliandro M, Sasso N, D’Oria S, Somma C, Martinelli G, Surico G, Lombardi G, Fiorentino A (2021). Poor-Prognosis Patients Affected by Glioblastoma: Retrospective Study of Hypofractionated Radiotherapy with Simultaneous Integrated Boost and Concurrent/Adjuvant Temozolomide. J Pers Med; 11(11):1145. [CrossRef]

- Gregucci F, Bonaparte I, Surgo A, Caliandro M, Carbonara R, Ciliberti MP, Aga A, Berloco F, De Masi M, De Pascali C, Fragnoli F, Indellicati C, Parabita R, Sanfrancesco G, Branà L, Ciocia A, Curci D, Guida P, Fiorentino A (2021). Brain Linac-Based Radiation Therapy: “Test Drive” of New Immobilization Solution and Surface Guided Radiation Therapy. J Pers Med;11(12):1351. [CrossRef]

- Therasse, P.; Arbuck, S.G.; Eisenhauer, E.A.; Wanders, J.; Kaplan, R.S.; Rubinstein, L.; Verweij, J.; Van Glabbeke, M.; van Oosterom, A.T.; Christian, M.C.; et al. (2000). New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J. Natl. Cancer Inst, 92, 205–216.

- Gregucci F, Di Guglielmo FC, Surgo A, Carbonara R, Laera L, Ciliberti MP, Gentile MA, Calbi R, Caliandro M, Sasso N, Davi’ V, Bonaparte I, Fanelli V, Giraldi D, Tortora R, Internò V, Giuliani F, Surico G, Signorelli F, Lombardi G, Fiorentino A (2023). Reirradiation with radiosurgery or stereotactic fractionated radiotherapy in association with regorafenib in recurrent glioblastoma Strahlenther Onkol. [CrossRef]

- Gregucci F, Surgo A, Carbonara R, Laera L, Ciliberti MP, Gentile MA, Caliandro M, Sasso N, Bonaparte I, Fanelli V, Tortora R, Paulicelli E, Surico G, Lombardi G, Signorelli F, Fiorentino A (2022). Radiosurgery and Stereotactic Brain Radiotherapy with Systemic Therapy in Recurrent High-Grade Gliomas: Is It Feasible? Therapeutic Strategies in Recurrent High-Grade Gliomas. J Pers Med;12(8):1336. [CrossRef]

- Reddy K, Damek D, Gaspar LE, et al. (2012). Phase II trial of hypofractionated IMRT withtemozolomide for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. IntJ Radiat Oncol Biol Phys;84(3):655–660.17.

- Chen C, Damek D, Gaspar LE, et al. (2011). Phase I trial of hypofractionated intensity-modulated radiotherapy with temozolomide chemotherapy for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys;81(4):1066–1074.18.

- Walker MD, Strike TA, Sheline GE (1979). An analysis of dose-effect relationshipin the radiotherapy of malignant gliomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys;5(10):1725–1731.

- Iuchi T, Hatano K, Kodama T, et al. (2014). Phase 2 trial of hypofractionated high-dose intensity modulated radiation therapy with concurrent and adjuvant temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys;88(4):793–800.21.

- Navarria P, Pessina F, Tomatis S, et al. (2017). Are three weeks hypofractionated radia-tion therapy (HFRT) comparable to six weeks for newly diagnosed glioblastomapatients? Results of a phase II study. Oncotarget;8(40):67696–67708.

- Rayan A, Abdel-Kareem S, Hasan H, Zahran AM, Gamal DA. (2020). Hypofractionated radiation therapy with temozolomide versus standard chemoradiation in patients with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM): A prospective, single institution experience. Reports of Practical Oncology and Radiotherapy 25 (2020) 890– 898. 2020.

- Terasaki M, Eto T, Nakashima S, et al. (2011). A pilot study of hypofractionated radiation therapy with temozolomide for adults with glioblastoma multiforme. JNeurooncol;102(2):247–253.

- Blumenthal DT, Won M, Mehta MP, Curran WJ, Souhami L, Michalski JM, Rogers CL, Corn BW (2009). Short delay in initiation of radiotherapy may not affect outcome of patients with glioblastoma: a secondary analysis from the radiation therapy oncology group database. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 733–9. [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, D. T. , Won, M., Mehta, M. P., Gilbert, M. R. & Corn, B. W (2018). Short delay in initiation of radiotherapy for patients with glioblastoma- effect of concurrent chemotherapy: a secondary analysis from the NRG Oncology/Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) database. Neuro Oncol. 20. [CrossRef]

- Mallick S, Kunhiparambath H, Gupta S, Benson R, Sharma S, Laviraj MA et al. (2018) Hypofractionated accelerated radiotherapy (HART) with concurrent and adjuvant temozolomide in newly diagnosed glioblastoma: a phase II randomized trial (HART-GBM trial). J Neurooncol 140(1) :75–82.

- Louvel G, Metellus P, Noel G, Peeters S, Guyotat J, Duntze J et al. (2016) Delaying standard combined chemoradiotherapy after surgical resection does not impact survival in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients. Radiother Oncol 118(1):9–15.

- Lv L, Eda V, Callegaro-Filho S, Koch Lde D, Pontes Lde O, Weltman B (2016) E et al. Minimizing the uncertainties regarding the effects of delaying radiotherapy for Glioblastoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiother Oncol 118(1):1–8.

- Zur I, Tzuk-Shina T, Guriel M, Eran A, Kaidar-Person O (2020). Survival impact of the time gap between surgery and chemo-radiotherapy in Glioblastoma patients. Sci Rep;10(1):9595. [CrossRef]

| Table 1 | S-RT | Hypo-RT | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | ||||

| 43 | 52 | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 24 (56%) | 35 (67%) | 0.25 | |

| Female | 19 (44%) | 17 (33%) | ||

| Age | ||||

| Median (IQR) [years] | 54 (24-74) | 65 (37-82) | <0.001 | |

| < 60 [years] | 28 (65%) | 13 (25%) | ||

| 60-65 [years] | 9 (21%) | 14 (25%) | ||

| > 65 [years] | 6 (14%) | 25 (50%) | ||

| MGMT methylation | ||||

| Methylated | 12 (28%) | 11 (21%) | 0.37 | |

| Unmethylated | 7 (16%) | 5 (10%) | ||

| Not Available | 24 (56%) | 36 (69%) | ||

| Surgery at diagnosis | ||||

| Complete | 18 (42%) | 10 (19%) | 0.01 | |

| Incomplete | 19 (44%) | 23 (44%) | ||

| Unresectable (Biopsy) | 6 (14%) | 19 (37%) | ||

| Median time between surgery and adjuvant therapy | ||||

| Median (IQR) [days] | 55 (46-75) | 53 (41-64) | 0.192 | |

| Adjuvant RT (total dose) | ||||

| 60 Gy in 30 fractions | 31 (72%) | - | <0.001 | |

| >60 Gy in 30 fractions | 12 (28%) | - | ||

| 40.5 Gy in 15 fractions | - | 17 (33%) | ||

| >40.5 Gy in 15 fractions | - | 35 (67%) | ||

| Adjuvant TMZ (cycles) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (5-17) | 6 (4-14) | 0.108 | |

| Reirradiation | ||||

| Yes | 21 (49%) | 18 (35%) | 0.167 | |

| Not | 22 (51%) | 34 (65%) | ||

| Second line systemic therapy | ||||

| Yes | 24 (56%) | 21 (40%) | 0.312 | |

| Not | 10 (23%) | 15 (29%) | ||

| Not Available | 9 (21%) | 16 (31%) | ||

| Type of second line systemic therapy | ||||

| Regorafenib | 11 (48%) | 10 (48%) | 0.365 | |

| Fotemustine | 3 (12%) | 2 (10%) | ||

| Bevacizumab | 4 (15%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Not Available | 6 (25%) | 8 (37%) | ||

| Follow-up | ||||

| Median (range) [months] | 25 (18-36) | 31 (22-43) | 0.107 | |

| Table 2 Variable |

Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | ||

| Age (≥ 65 years) | |||||||

| 1.48 | 0.79-2.76 | 0.21 | 2.06 | 1.05-4.03 | 0.03 | ||

| MGMT methylation (YES) | |||||||

| 0.40 | 0.17-0.95 | 0.03 | - | - | - | ||

| Surgery type (Incomplete) | |||||||

| 1.17 | 0.60-2.29 | 0.63 | - | - | - | ||

| Surgery-RT time (≥ 55 days) | |||||||

| 0.38 | 0.19-0.73 | 0.003 | 0.27 | 0.13-0.56 | 0.0003 | ||

| Adjuvant RT (30 fx) | |||||||

| 0.55 | 0.29-0.99 | 0.05 | - | - | - | ||

| Adjuvant TMZ (≥ 6 cycles) | |||||||

| 0.42 | 0.23-0.78 | 0.005 | 0.35 | 0.18-0.65 | 0.001 | ||

| Reirradiation (YES) | |||||||

| 1.84 | 1.01-3.37 | 0.04 | - | - | - | ||

| Second line systemic therapy (YES) | |||||||

| 1.27 | 0.69-2.31 | 0.42 | - | - | - | ||

| Table 3: Variable |

Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | |||

| Age | ||||||||

| (≥ 60 years) | S-RT | 0.87 | 0.23-3.25 | 0.84 | - | - | - | |

| (≥ 65 years) | Hypo-RT | 1.62 | 0.78-3.36 | 0.18 | 2.85 | 1.26-6.44 | 0.01 | |

| MGMT methylation | ||||||||

| (YES) | S-RT | 0.49 | 0.11-2.23 | 0.35 | - | - | - | |

| (YES) | Hypo-RT | 0.38 | 0.13-1.1 | 0.07 | - | - | - | |

| Surgery type | ||||||||

| (Incomplete) | S-RT | 1.16 | 0.38-3.47 | 0.78 | - | - | - | |

| (Incomplete) | Hypo-RT | 0.93 | 0.38-2.29 | 0.88 | - | - | - | |

| Surgery-RT time | ||||||||

| (≥ 55 days) | S-RT | 0.64 | 0.21-2.01 | 0.44 | - | - | - | |

| (≥ 55 days) | Hypo-RT | 0.31 | 0.13-0.73 | 0.007 | 0.22 | 0.09-0.54 | 0.0008 | |

| Adjuvant RT | ||||||||

| (≥ 60 Gy) | S-RT | 0.28 | 0.9-1.86 | 0.2 | - | - | - | |

| (≥ 40.5Gy) | Hypo-RT | 1.08 | 0.49-2.39 | 0.84 | - | - | - | |

| Adjuvant TMZ | ||||||||

| (≥ 6 cycles) | S-RT | 0.48 | 0.13-1.69 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.02-0.73 | 0.01 | |

| (≥ 6 cycles) | Hypo-RT | 0.40 | 0.19-0.84 | 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.14-0.66 | 0.002 | |

| Reirradiation | ||||||||

| (YES) | S-RT | 2.79 | 0.77-10.09 | 0.11 | - | - | - | |

| (YES) | Hypo-RT | 1.82 | 0.89-3.73 | 0.10 | - | - | - | |

| Second line systemic therapy | ||||||||

| (YES) | S-RT | 1.91 | 0.59-6.14 | 0.27 | - | - | - | |

| (YES) | Hypo-RT | 1.19 | 0.58-2.45 | 0.61 | - | - | - | |

| Table 4 Variable |

Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | P | HR | 95%CI | P | ||

| Age | |||||||

| (≥ 60 years) | S-RT | 0.834 | 0.39-1.77 | 0.63 | - | - | - |

| (≥ 65 years) | Hypo-RT | 1.44 | 0.76-2.75 | 0.25 | 2.15 | 1.07-4.31 | 0.03 |

| MGMT methylation | |||||||

| (YES) | S-RT | 1.02 | 0.45-2.31 | 0.95 | - | - | - |

| (YES) | Hypo-RT | 0.51 | 0.22-1.17 | 0.11 | - | - | - |

| Surgery type | |||||||

| (Incomplete) | S-RT | 0.75 | 0.37-1.52 | 0.42 | - | - | - |

| (Incomplete) | Hypo-RT | 1.09 | 0.47-2.48 | 0.83 | - | - | - |

| Surgery-RT time | |||||||

| (≥ 55 days) | S-RT | 1.19 | 0.58-2.42 | 0.63 | - | - | - |

| (≥ 55 days) | Hypo-RT | 0.43 | 0.21-0.86 | 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.14-0.63 | 0.001 |

| Adjuvant RT | |||||||

| (≥ 60 Gy) | S-RT | 0.61 | 0.28-1.26 | 0.17 | - | - | - |

| (≥ 40.5Gy) | Hypo-RT | 1.22 | 0.60-2.47 | 0.57 | - | - | - |

| Adjuvant TMZ | |||||||

| (≥ 6 cycles) | S-RT | 0.47 | 0.22-0.98 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.12-0.62 | 0.002 |

| (≥ 6 cycles) | Hypo-RT | 0.38 | 0.20-0.74 | 0.004 | 0.31 | 0.15-0.60 | 0.0006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).