1. Introduction

Radiotherapy (RT) is integral in the therapeutic management of hematologic malignancies (HM), either alone, as part of a combined modality, or as a consolidation following completion of chemotherapy. HM include Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), plasma cell neoplasms and leukemias. The most commonly used RT dose fractionation schemes for the treatment of HM range between 20-50 Gy delivered over 2-5 weeks [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

There has been a paradigm shift in radiation oncology with rapid technological advancements, including the introduction of four-dimensional image acquisition, real-time image guidance, and intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). As such, stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) and hypofractionated RT(HFRT) delivering highly precise and biologically effective radiation doses have been employed in common malignancies, including lung and prostate cancer. The outcome of contemporary interventions has been impressive, with improved local tumor control, increased overall survival, and minimal toxicity [

7]. Further, the reduced number of fractions and an overall shorter treatment time may be cost effective and particularly benefit patients in remote areas away from urban cancer centers [

8,

9]. Therefore, it is intriguing to explore and evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of HFRT in the radiotherapeutic management of HM, assuming no increased toxicity or compromise of local control.

The COVID-19 pandemic created a global healthcare crisis. Human and technical resources were reclassified and redirected to mitigate the challenges of the pandemic. RT departments were forced to rethink and innovate RT delivery models to minimize the risk of COVID-19 infection in cancer patients and healthcare staff. Consequently, several professional groups and organizations suggested alterations to conventional radiation schedules delivered over several weeks. HFRT with a reduced number of fractions, a shorter overall therapy time, and a higher dose per fraction was proposed, with or without clinical evidence, in the radiotherapeutic management of several cancers [

10].The intention was to reduce transmission and the risk of infection among immunocompromised cancer patients and involved healthcare workers, and diminish the consequences of reduced human resources during the pandemic [

11]. The International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group (ILROG) task force provided emergency guidelines with alternative hypofractionated treatment regimens in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The proposed dose/fractionation schemes were based on pre-defined radiobiological parameters (i.e., the

α/β ratio, total dose in 2 Gy fractions (EQD2), and biological equivalent dose (BED)) to maintain the clinical efficacy and toxicity at levels similar to standard dose fractionation [

12]. Currently, these recommendations are included in the guidelines of the Lymphoma Disease Site Group at our institution, to be implemented under extraordinary circumstances such as a pandemic. Here, we retrospectively evaluated clinical outcomes of HM patients treated with HFRT at our centre during the COVID-19 pandemic, and demonstrate that this treatment regimen is as effective in local control as standard dose fractionation.

2. Methods

The current study is a retrospective review of clinical outcomes in patients diagnosed with HM and treated with HFRT regimens at an academic tertiary cancer centre between 2020-2022 during the COVID-19 pandemic. The provincial cancer registry provided the list of patients with HM who had received RT treatment during this period. This study was approved by The Research Ethics Board (REB) of the affiliated university (REB#: HS25664 (H2022:287)).

2.1. Data Collection

Clinical data were extracted from electronic charts using the Varian Medical Oncology (VMO) application, while RT data were collected with Varian Radiation Oncology (VRO) Eclipse 15.6. Pre- and post-treatment imaging data with accompanying text reports were captured through the IMPAX picture archiving and communication system (PACS). Two hundred and thirty-five patients who had received curative or palliative RT for HM between January 2020 and September 2022 were identified. Patients who received RT with conventional fractionation (CF) or palliative intent were excluded. Thirty-six patients with a confirmed pathological diagnosis of HM and subjected to HFRT as primary or consolidative treatment post chemotherapy were included in the analysis. Total dose in 2 Gy fractions (EQD2) for an α/β ratio of 10 and 3 was calculated for each patient [

13].

2.2. Outcome Measures

The primary clinical outcome was

overall response rate (ORR), defined as the proportion of patients with complete response (CR), partial response (PR), and stable disease (SD) within the irradiation field at the 1st follow-up after completion of treatment [

14,

15].

Each patient's metabolic or anatomical response was assessed based on positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). When pre- and/or post- treatment imaging was unavailable, the response was determined clinically. For the metabolic response, CR was defined as a Deauville score of 1, 2, and 3 with or without a residual mass. PR was defined as a Deauville score of 4 or 5 with reduced uptake compared to baseline and a residual mass of any size. SD was defined as no metabolic response with a Deauville score of 4 or 5 and no significant change in F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake from baseline, whereas progressive disease (PD) was defined as a Deauville score of 4 or 5 with an increase in the intensity of FDG uptake from baseline [

14,

15]. The anatomical response as CR, PR, SD or PD was determined by the change in tumor size between pre- and post-treatment CT scans of the involved site, as reported by the radiologist [

15].

Freedom from local progression (FFLP) was calculated from the start date of RT to the date of within-field progression by PET-CT. Patients dead without in-field progression were censored at the date of death or last follow-up [

16].

Overall survival (OS) was indicated by the date of diagnosis to the date of death from any cause.

2.3. Toxicity

Because of the retrospective nature of this study, reliable data collection for RT-related toxicity was not possible. However, an attempt was made to capture descriptive toxicity data from the clinical notes of the treating physicians; these data were graded using the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) toxicity criteria [

17].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics (mean, median, standard deviation) were used to describe cohort and treatment characteristics. In-field progression was calculated by the cumulative incidence function (CIF) accounting for competing risk (i.e., death). OS was assessed with the Kaplan–Meier estimator (KME).

3. Results

The clinical characteristics of the 36 patients included in this study are presented in

Table 1. Thirty-three patients (92%) had NHL or HL; the remaining subjects included patients with peripheral T- cell lymphoma (NOS), T- cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/ lymphoma, or plasmacytoma.

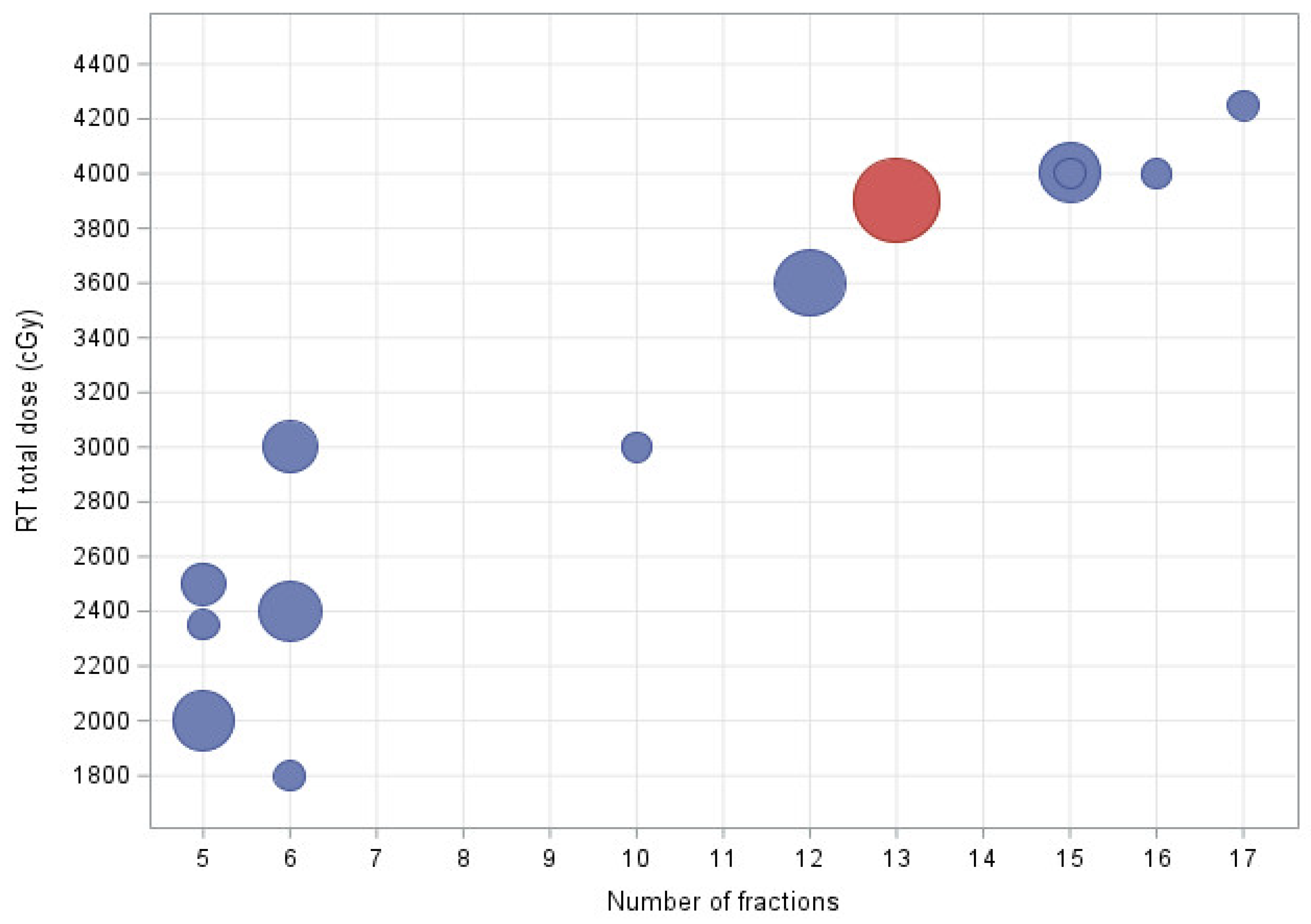

Eighteen patients (50%) had aggressive and nine (25%) indolent NHL. Nineteen patients (53%) presented with stage I/II and 15(42%) with stage III/IV disease. Twenty-five patients (69.4%) were subjected to consolidative and eleven (30%) to definitive RT. Regarding involved sites of treatment, 20 patients (56%) received RT to the neck and/or thorax, and 9 (25%) to the abdomen or pelvis. Thirty-two patients (89%) were treated with volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT); the remaining subjects received treatment with three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) or electrons. Response assessment was evaluated by PET in 26 (72%) and CT/MRI or clinical determination in 10 patients (28%). The mean time from diagnosis to the start of RT treatment was 6.2 months (SD ± 2.9). Total dose ranged from 18 to 42.5 Gy in 6 - 17 fractions with 2.67-5 Gy per fraction. The median EQD2 for an α/β ratio of 10 and 3 amounted to 39 (SD ± 13.86) and 43.60 Gy (SD ± 12), respectively. The most frequently used fractionation scheme was 39 Gy in 13 fractions (

Figure 1). The mean number of days over which treatment was completed was 12.9 days (SD ± 7.3).

Among all patients, only one subject receiving treatment to the axilla, supraclavicular, mediastinum and bilateral hilar regions experienced RTOG grade 2 lung toxicity; however, no intervention was required. There were no reports of radiation-induced toxicity (of any grade) or treatment interruptions for the remaining patients.

The most frequently used chemotherapy regimens were ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) in patients with HL and R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) in those with aggressive NHL; the mean number of chemo cycles received was 5 (SD ± 1.5). Two HL patients had also undergone autologous stem cell transplantation. One patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) had been subjected to an ALL-4 chemotherapy protocol. Patients treated with definitive intent RT did not receive any chemotherapy.

3.1. ORR

Mean time to 1st follow-up after completion of RT treatment was 2.7 months with an interquartile ratio (IQR) of 1.28. The ORR was 94.4% for the entire cohort, and 100, 94.4 and 83.3% for patients with indolent NHL, aggressive NHL, and HL, respectively. CR, PR and SD for the entire study population amounted to 69.4, 19.4 and 5.6 % respectively.

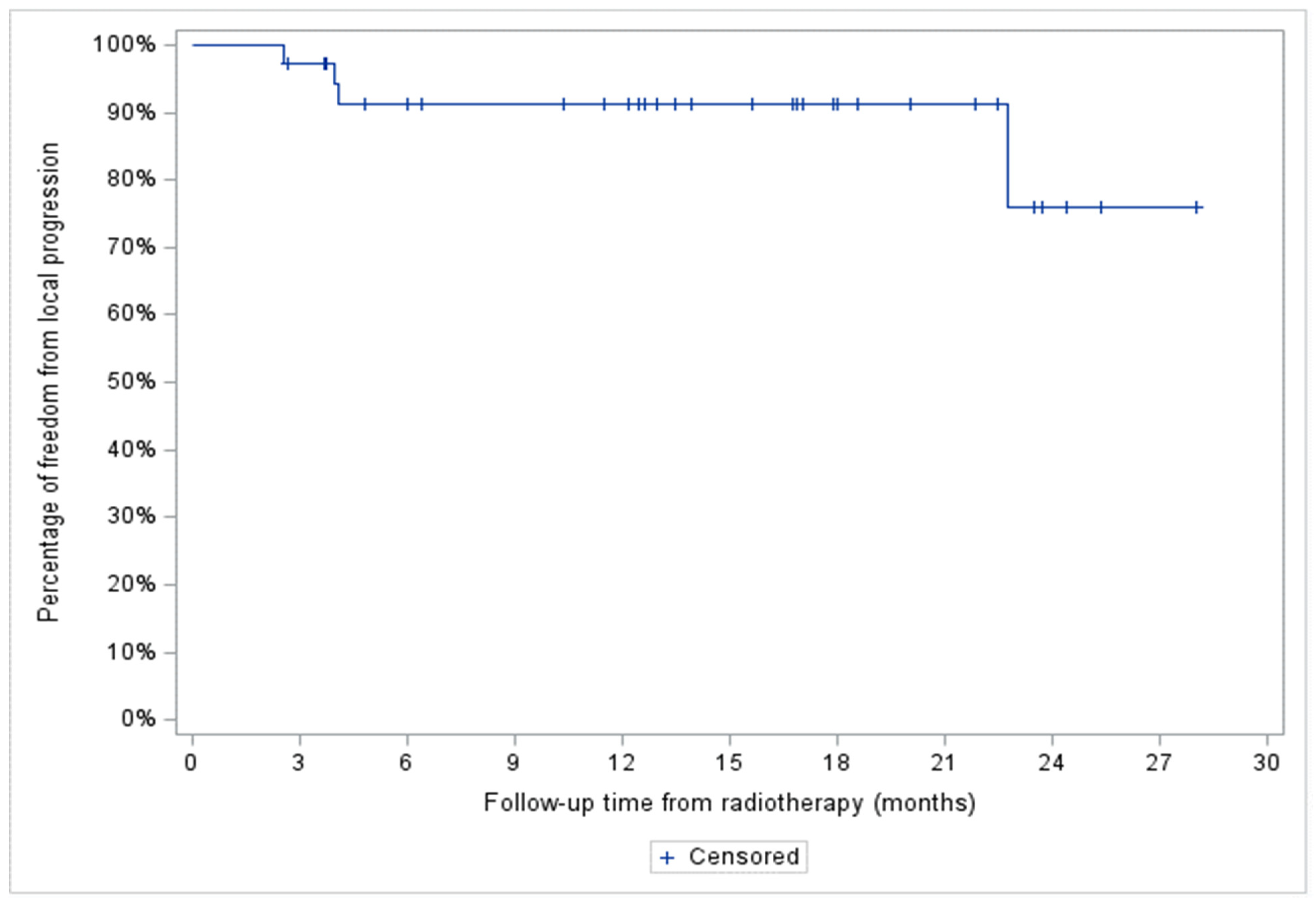

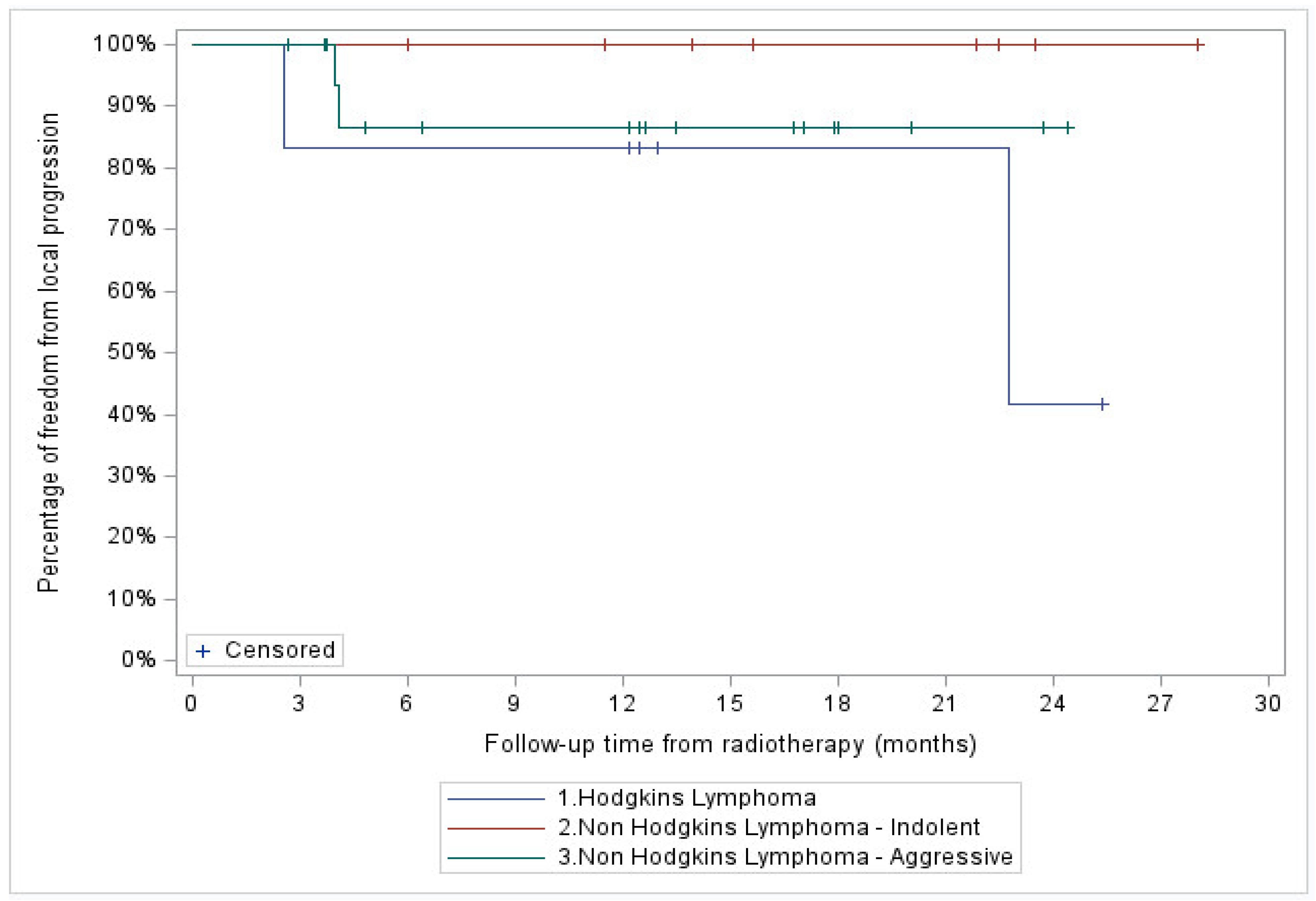

3.2. FFLP

Median follow-up of the entire cohort was 13.2 months. A total of 4 patients (11%), 2 with stage IV HL and 2 with stage III aggressive NHL, showed in-field local progression. In addition, two patients with stage IV aggressive NHL demonstrated systemic progression without local recurrence. At two years, FFLP was 76% (95% CI: 34-93%) for the entire cohort, and 100, 87 (95% CI: 56.4-96.5%) and 42% (95% CI: 1.1-84.3%) for the indolent NHL, aggressive NHL, and HL patient subgroups, respectively (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

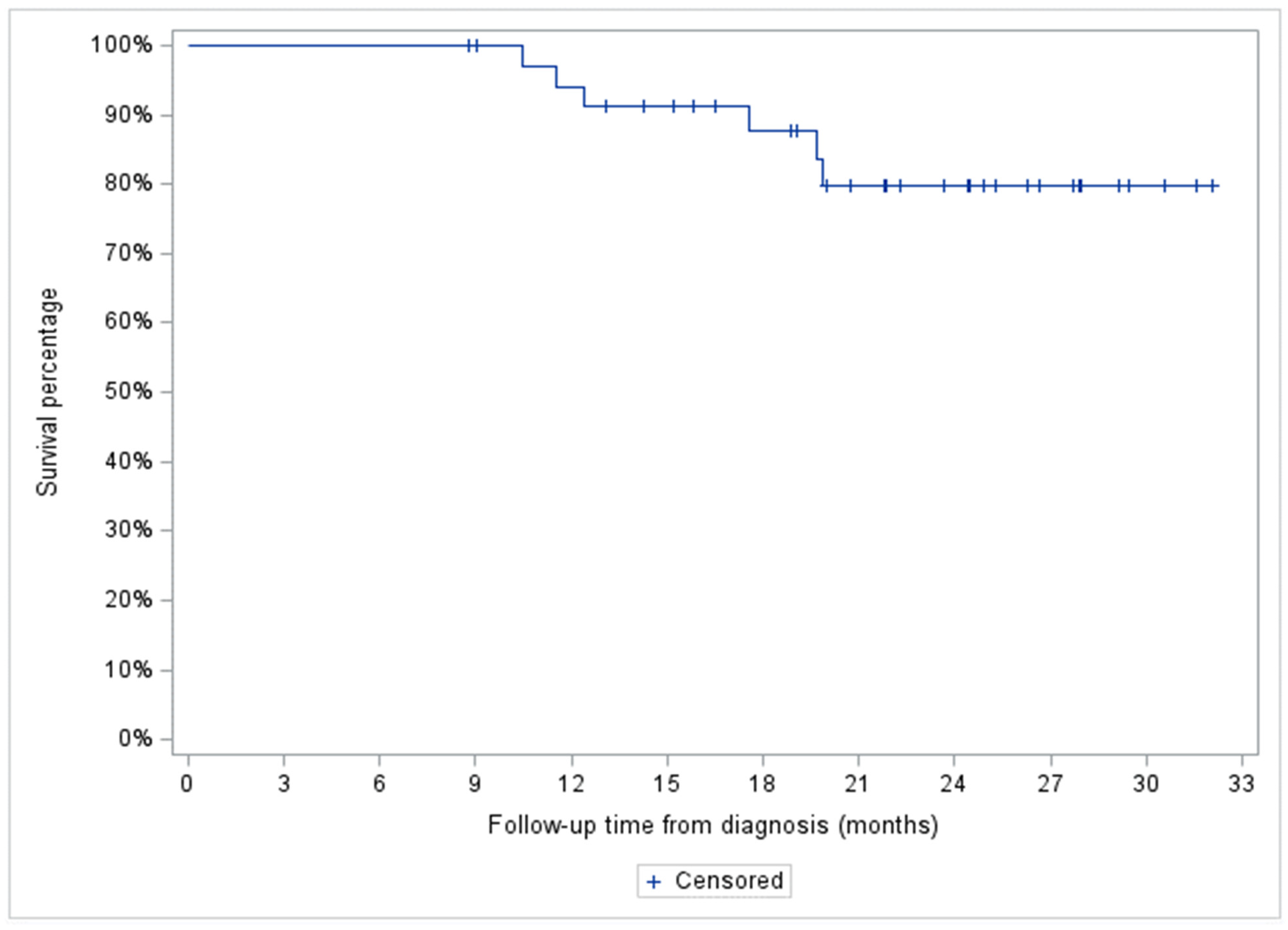

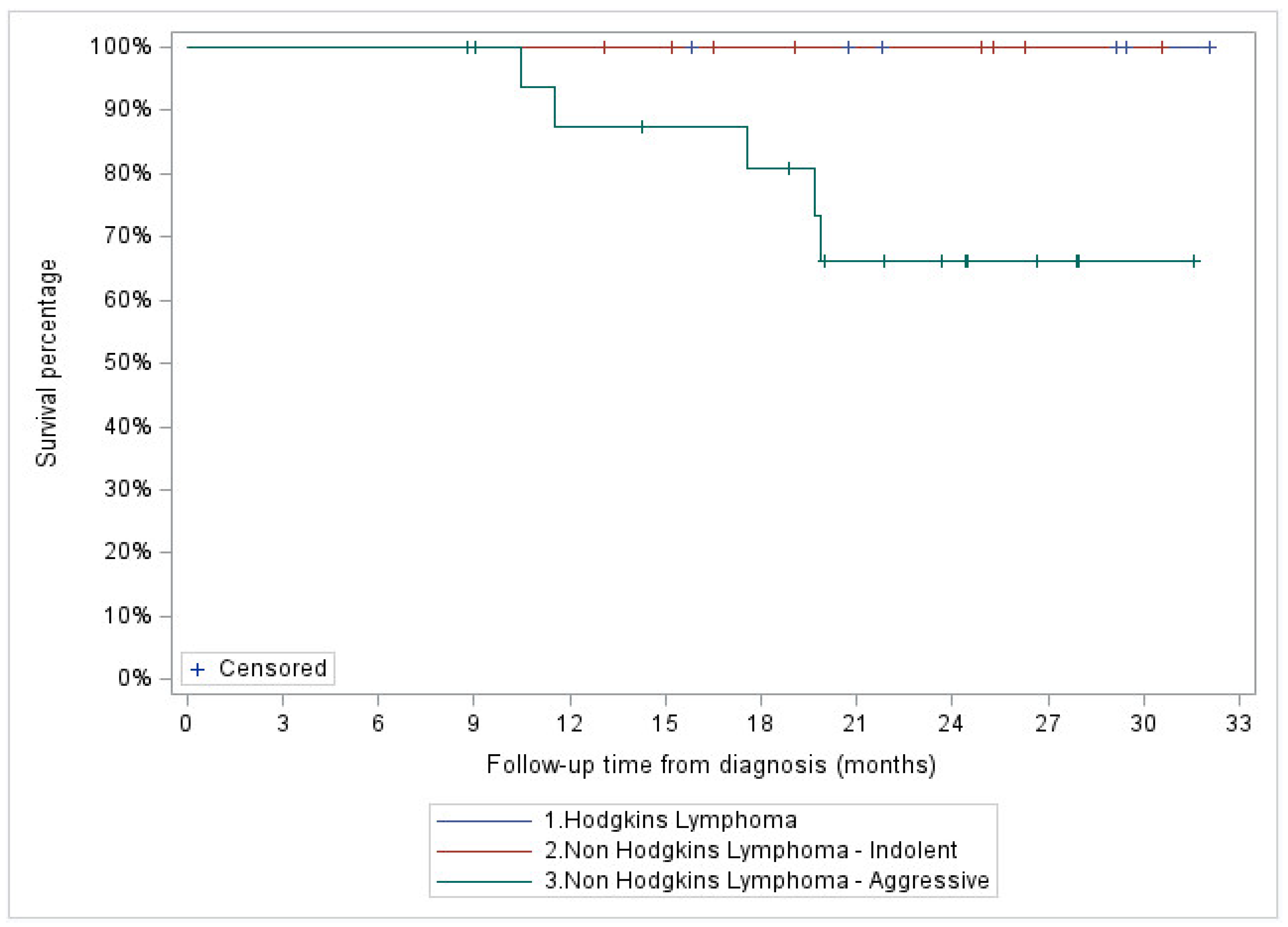

3.3. OS

Two-year OS for the entire cohort was 80% (95% CI: 59.9-90.5%), and 100, 66.1 (95% CI: 36.4-84.4%) and 100% for the indolent NHL, aggressive NHL, and HL patient subgroups, respectively (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

HM are highly radiosensitive compared to solid malignancies, and have a distinct radiobiological response with early interphase, premitotic, and apoptotic cell death. The possible cellular mechanisms underlying the response to RT leading to apoptosis are lipid peroxidation at the cell membrane, modulation of signal transduction, radiation-induced cross-linking of nuclear DNA, and DNA fragmentation [

18]. In clinical practice, low to moderate dose involved site radiotherapy (ISRT) with CF; 20-50 Gy over 2-5 weeks) constitutes the standard radiotherapeutic management for most HM with excellent response and long term outcomes. [

19].

The current study is a review of patients treated with HFRT with an EQD2 similar to the standard dose fractionation. However, interconversion of fractionation schemes comes with uncertainties and has been challenging. The Linear Quadratic (LQ) model is the most widely used radiobiological model to calculate BED and EQD2 for different dose fractionation schedules in clinical practice, incorporates both mitotic and apoptotic cell death, and can predict the radiation effects on tumor control and normal tissue complications as a consequence of altered dose fractionation schedules [

20]. The LQ model assumes two components of cell killing: one proportional to dose (α, linear, and dose rate independent) and the other proportional to the square of the dose (β, quadratic, and dose rate dependent). Thus, the α/β ratio (ABR) incorporated into the LQ equation reflects the numerical expressions of radiosensitivity and provides a tool to determine BED and EQD2 for tumor control and normal tissue toxicity for hypo- or hyperfractionation in comparison to conventional fractionation [

21,

22,

23]. The radiosensitivity of lymphomas is remarkable, with a low surviving fraction at 2 Gy (SF2Gy), a high ABR (8-10 Gy), and little to no shoulder on a cell survival curve. [

24,

25,

26,

27]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the ILROG designed a set of HFRT dose fractionation schedules to treat HM based on EQD2 with an ABR of 10 and 3 for measurable endpoints of tumor control as well as acute and late toxicity [

12].With the provided radiobiological parameters for dose conversion, HFRT is expected to achieve similar tumor control as CFRT, and any potential late toxicity for organs at risk (OAR) within the irradiation field may be mitigated by the modern conformal RT techniques. To date, there is scant literature available on the efficacy of HFRT in HM.

Wright et al. have reported the outcomes of 169 patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with salvage and palliative RT. One hundred RT courses (49%) were delivered with HFRT with a median RT dose of 30 Gy (8-60 Gy). ORR was 60% for the entire cohort. No statistically significant differences were observed in ORR, time to local failure (TTLF), and OS between hypofractionation and conventional fractionation [

28]. Others retrospectively reviewed the outcome of 162 patients with aggressive NHL treated with radical, consolidative, or palliative RT. HFRT (2.4-3 Gy daily fractions; median total dose 30 Gy/ 10 fractions) and CF (1.8-2 Gy daily fractions; median total dose 40 Gy/ 20 fractions) were used in 51 and 111 patients, respectively. No difference in ORR, FFLR, and OS were observed between the two groups [

29]. A very recent publication reported the effects of HFRT in gastric lymphoma. Forty-five patients with localized gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma received 30-36 Gy in 15-18 fractions, 26-28 Gy in 13-14 fractions, or 24-25 Gy in 10 fractions. Results revealed excellent local control and survival with no serious adverse events, regardless of dose fractionation. [

30]. The current retrospective study is unique in several aspects. It was conducted at an academic Centre where patients with HM qualifying as candidates for RT are selected through a weekly multi-disciplinary conference; most RT plans go through a peer-reviewed quality assurance process. The majority of patients included in the study were diagnosed with NHL. Only those patients who received RT with an intention of local control and/or cure were considered. Though most patients received RT to cervical and/or thoracic sites, a small number of patients (17%) were exclusively treated to their abdomen, including retroperitoneum, mesentery, and spleen, without any documented toxicity. Patients who underwent consolidative RT following chemotherapy received standard chemotherapy according to institution guidelines [

31].

Most patients were planned and treated with modern technology using VMAT. PET-CT was used in the majority of patients to assess their response to treatment. The HFRT dose fractionation used in this study is similar or close to the EQD2 for standard CF schedules and ranged between 39-43 Gy, with clinical outcomes similar to previously published data. Indeed, a multicenter, prospective randomized trial comparing CF low dose 24-30 Gy vs. high dose 40-45 Gy in 20-23 fractions in indolent and aggressive NHL demonstrated an ORR > 90% in both treatment arms and subgroups of NHL [

32]. The current study, mainly comprising NHL patients, showed an ORR of 94% at approximately 3 months post-completion of HFRT treatment, demonstrating no compromise in ORR with this approach. We demonstrate excellent in-field local control with HFRT as reflected by FFLP scores of 87 -100% at two years for all NHL patients.

Limitations

The authors acknowledge that the current results are based on a single-institution retrospective study involving a relatively small sample size and short follow-up; we aim to complement our current findings with results from larger patient groups and longer-term follow-ups, once data is available. Due to the small sample size, subset analysis based on histopathology, dose fractionation, disease stage, and treatment intent was impossible. Specifically, the number of patients with HL and non-lymphoma HM was extremely low for any meaningful analysis. A major limitation is the absence of structured criteria to capture and document toxicity, compounded further by the posed logistic challenges to collect toxicity data during COVID-19. Only long-term follow-up will determine the risk of late toxicity in younger patients. Furthermore, we did not directly compare our results with a patient group treated with CF within our study population.

5. Conclusions

HM are highly radiosensitive with excellent response and local control achieved with HFRT. The current study provides robust pilot data for a prospective multicenter trial to confirm and validate the therapeutic effectiveness and lack of toxicity of curative intent HFRT in HM.

Acknowledgments

Oliver Bucher from the department of Epidemiology, CancerCare Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba Canada for his input for the study statistics. Science Impact (Winnipeg, Canada) for post-editing the final manuscript.

References

- Dabaja, B.S.; Ng, A.K.; Terezakis, S.A.; Plastaras, J.P.; Yunes, M.; Wilson, L.D.; Specht, L.; Yahalom, J. Making Every Single Gray Count: Involved Site Radiation Therapy Delineation Guidelines for Hematological Malignancies. Endocrine 2020, 106, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Specht, L.; Yahalom, J.; Illidge, T.; Berthelsen, A.K.; Constine, L.S.; Eich, H.T.; Girinsky, T.; Hoppe, R.T.; Mauch, P.; Mikhaeel, N.G.; et al. Modern Radiation Therapy for Hodgkin Lymphoma: Field and Dose Guidelines From the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group (ILROG). Endocrine 2014, 89, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illidge, T.; Specht, L.; Yahalom, J.; Aleman, B.; Berthelsen, A.K.; Constine, L.; Dabaja, B.; Dharmarajan, K.; Ng, A.; Ricardi, U.; et al. Modern Radiation Therapy for Nodal Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma—Target Definition and Dose Guidelines From the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group. Endocrine 2014, 89, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahalom, J.; Illidge, T.; Specht, L.; Hoppe, R.T.; Li, Y.-X.; Tsang, R.; Wirth, A. Modern Radiation Therapy for Extranodal Lymphomas: Field and Dose Guidelines From the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group. Endocrine 2015, 92, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, R.W.; Campbell, B.A.; Goda, J.S.; Kelsey, C.R.; Kirova, Y.M.; Parikh, R.R.; Ng, A.K.; Ricardi, U.; Suh, C.-O.; Mauch, P.M.; et al. Radiation Therapy for Solitary Plasmacytoma and Multiple Myeloma: Guidelines From the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group. Endocrine 2018, 101, 794–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakst, R.L.; Dabaja, B.S.; Specht, L.K.; Yahalom, J. Use of Radiation in Extramedullary Leukemia/Chloroma: Guidelines From the International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group. Endocrine 2018, 102, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceniceros, L.; Aristu, J.; Castañón, E.; Rolfo, C.; Legaspi, J.; Olarte, A.; Valtueña, G.; Moreno, M.; Gil-Bazo, I. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for the treatment of inoperable stage I non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2015, 18, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.; Stav, I.; Den, R.B.; Gordon, N.; Sarfaty, M.; Neiman, V.; Rosenbaum, E.; Goldstein, D.A. The Financial Impact of Hypofractionated Radiation for Localized Prostate Cancer in the United States. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucca, A.; Boyes, A.; Newling, G.; Hall, A.; Girgis, A. Travelling all over the countryside: Travel-related burden and financial difficulties reported by cancer patients in New South Wales and Victoria. Aust. J. Rural. Heal. 2011, 19, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, D.J.; Yom, S.S.; Saeed, H.; El Naqa, I.; Ballas, L.; Bentzen, S.M.; Chao, S.T.; Choudhury, A.; Coles, C.; Dover, L. Radiation Fractionation Schedules Published During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review of the Quality of Evidence and Recommendations for Future Development. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 108, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcock, R.; Thomas, T.V.; Estes, C.; Filippi, A.R.; Katz, M.S.; Pereira, I.J.; Saeed, H. COVID-19: Global radiation oncology’s targeted response for pandemic preparedness. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 22, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahalom, J.; Dabaja, B.S.; Ricardi, U.; Ng, A.; Mikhaeel, N.G.; Vogelius, I.R.; Illidge, T.M.; Qi, S.; Wirth, A.; Specht, L. ILROG emergency guidelines for radiation therapy of hematological malignancies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Blood 2020, 135, 1829–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Leeuwen CM, Oei AL, Crezee J, Bel A, Franken NAP, Stalpers LJA; et al. The alfa and beta of tumours: A review of parameters of the linear-quadratic model, derived from clinical radiotherapy studies. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 13, 96. [CrossRef]

- Barrington, S.F.; Mikhaeel, N.G.; Kostakoglu, L.; Meignan, M.; Hutchings, M.; Müeller, S.P.; Schwartz, L.H.; Zucca, E.; Fisher, R.I.; Trotman, J.; et al. Role of Imaging in the Staging and Response Assessment of Lymphoma: Consensus of the International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas Imaging Working Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 3048–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheson, B.D.; Fisher, R.I.; Barrington, S.F.; Cavalli, F.; Schwartz, L.H.; Zucca, E.; Lister, T.A. Recommendations for initial evaluation, stag-ing, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: The Lugano classification. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 3059–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, L.; Smith, P.; Qian, W.; Falk, S.; Benstead, K.; Illidge, T.; Linch, D.; Robinson, M.; Jack, A.; Hoskin, P. Reduced dose radiotherapy for local control in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A randomised phase III trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2011, 100, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Group RTO. RTOG toxicity criteria. Philadelphia, American College of Radiology–Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. 2000.

- Kimball AS, Webb TJ. The roles of radiotherapy and immunotherapy for the treatment of lymphoma. Mol. Cell. Pharmacol. 2013, 5, 27.

- Wirth, A.; Mikhaeel, N.G.; Aleman, B.M.; Pinnix, C.C.; Constine, L.S.; Ricardi, U.; Illidge, T.M.; Eich, H.T.; Hoppe, B.S.; Dabaja, B.; et al. Involved Site Radiation Therapy in Adult Lymphomas: An Overview of International Lymphoma Radiation Oncology Group Guidelines. Endocrine 2020, 107, 909–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, J.F. The linear-quadratic formula and progress in fractionated radiotherapy. Br. J. Radiol. 1989, 62, 679–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner DJ, editor The linear-quadratic model is an appropriate methodology for determining isoeffective doses at large doses per fraction. Seminars in radiation oncology; 2008: Elsevier.

- Wlodek, D.; Hittelman, W.N. The Relationship of DNA and Chromosome Damage to Survival of Synchronized X-Irradiated L5178Y Cells: II. Repair. Radiat. Res. 1988, 115, 566–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, J.R. A brief survey of aberration origin theories. Mutat. Res. 1998, 404, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, J.; Peckham, M.; Steel, G. The radioresponsiveness of human tumours and the initial slope ofthe cell survival curve. Radiother. Oncol. 1984, 2, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, L.M.; Leblanc, J.; Wilkins, D.; Raaphorst, G.P. Fitting the linear–quadratic model to detailed data sets for different dose ranges. Phys. Med. Biol. 2006, 51, 2813–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barendsen, G. Dose fractionation, dose rate and iso-effect relationships for normal tissue responses. Endocrine 1982, 8, 1981–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldridge, D.R.; Radford, I.R. Explaining differences in sensitivity to killing by ionizing radiation between human lymphoid cell lines. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 2817–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wright CM, Dreyfuss AD, Baron JA, Maxwell R, Mendes A, Barsky AR; et al. Radiation Therapy for Relapsed or Refractory Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: What Is the Right Regimen for Palliation? Advances in Radiation Oncology. 2022, 7, 101016. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, I.; Kashiwado, K.; Adachi, Y.; Imano, N.; Takeuchi, Y.; Nishibuchi, I.; et al. The Efficacy of Hypofractionated Radiotherapy for Local Control in Aggressive non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Physics 2019, 105, E471. [CrossRef]

- Ochi, M.; Murakami, Y.; Nishibuchi, I.; Imano, N.; Katsuta, T.; Takahashi, I. Outcome of Hypofractionated Radiotherapy for Localized Gastric Mucosa-associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma. Anticancer. Res. 2023, 43, 3673–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCMB practice guide lines. Available online: https://www.cancercare.mb.ca/For-Health-Professionals/treatment-guidelines-regimen-reference-orders.

- Lowry, L.; Smith, P.; Qian, W.; Falk, S.; Benstead, K.; Illidge, T.; Linch, D.; Robinson, M.; Jack, A.; Hoskin, P. Reduced dose radiotherapy for local control in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A randomised phase III trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2011, 100, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).