Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

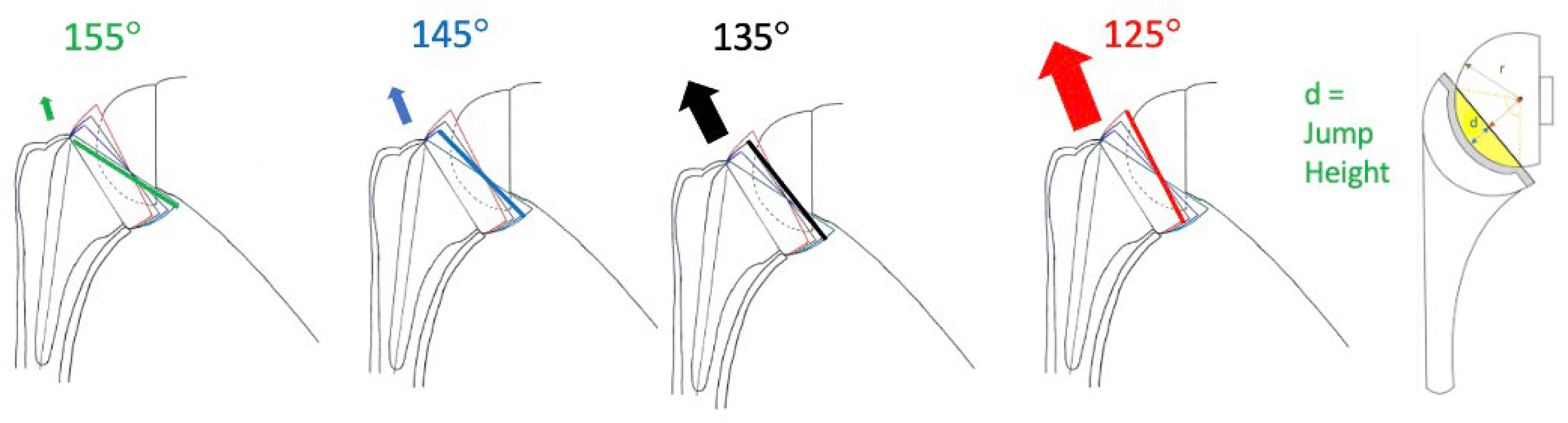

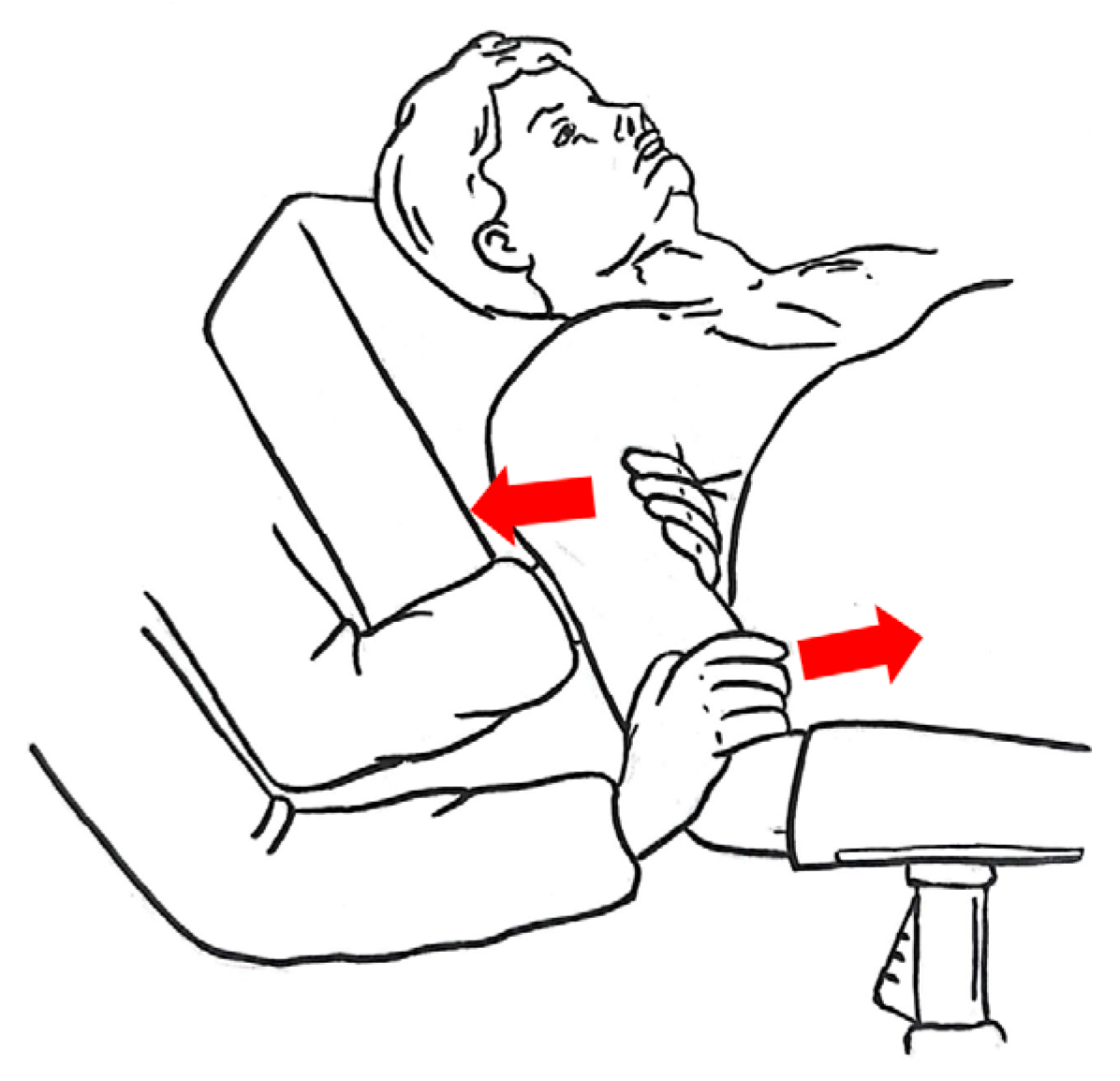

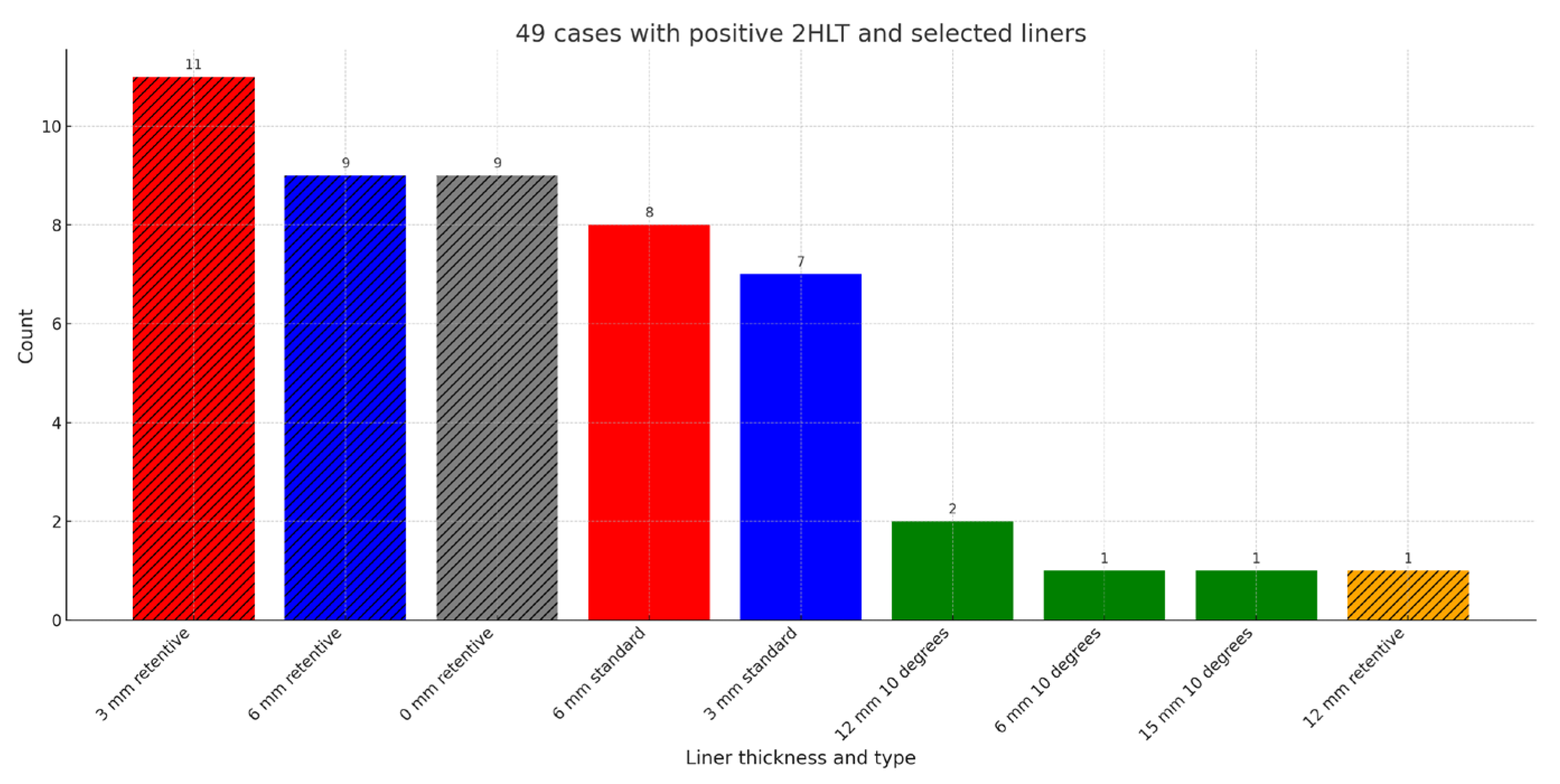

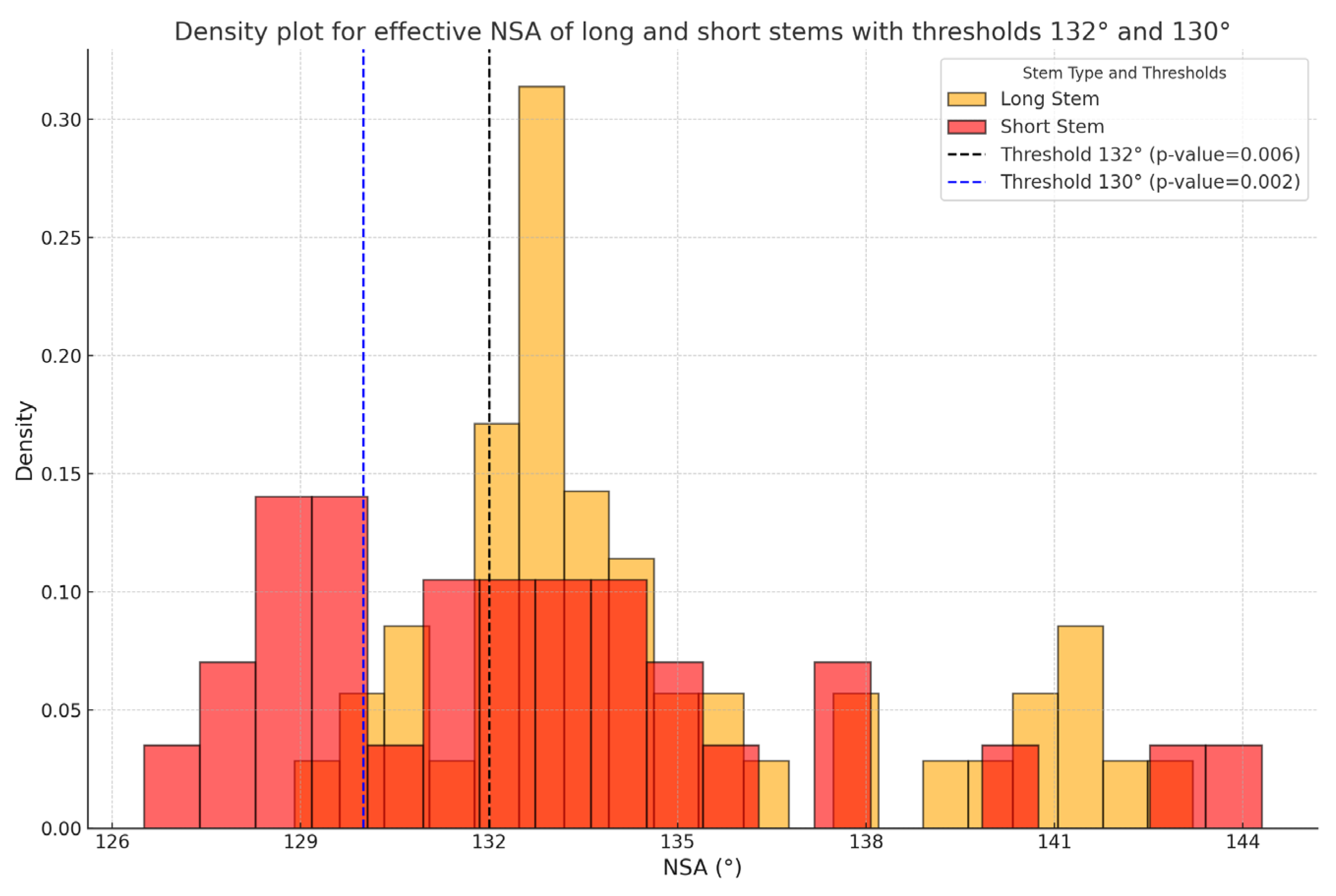

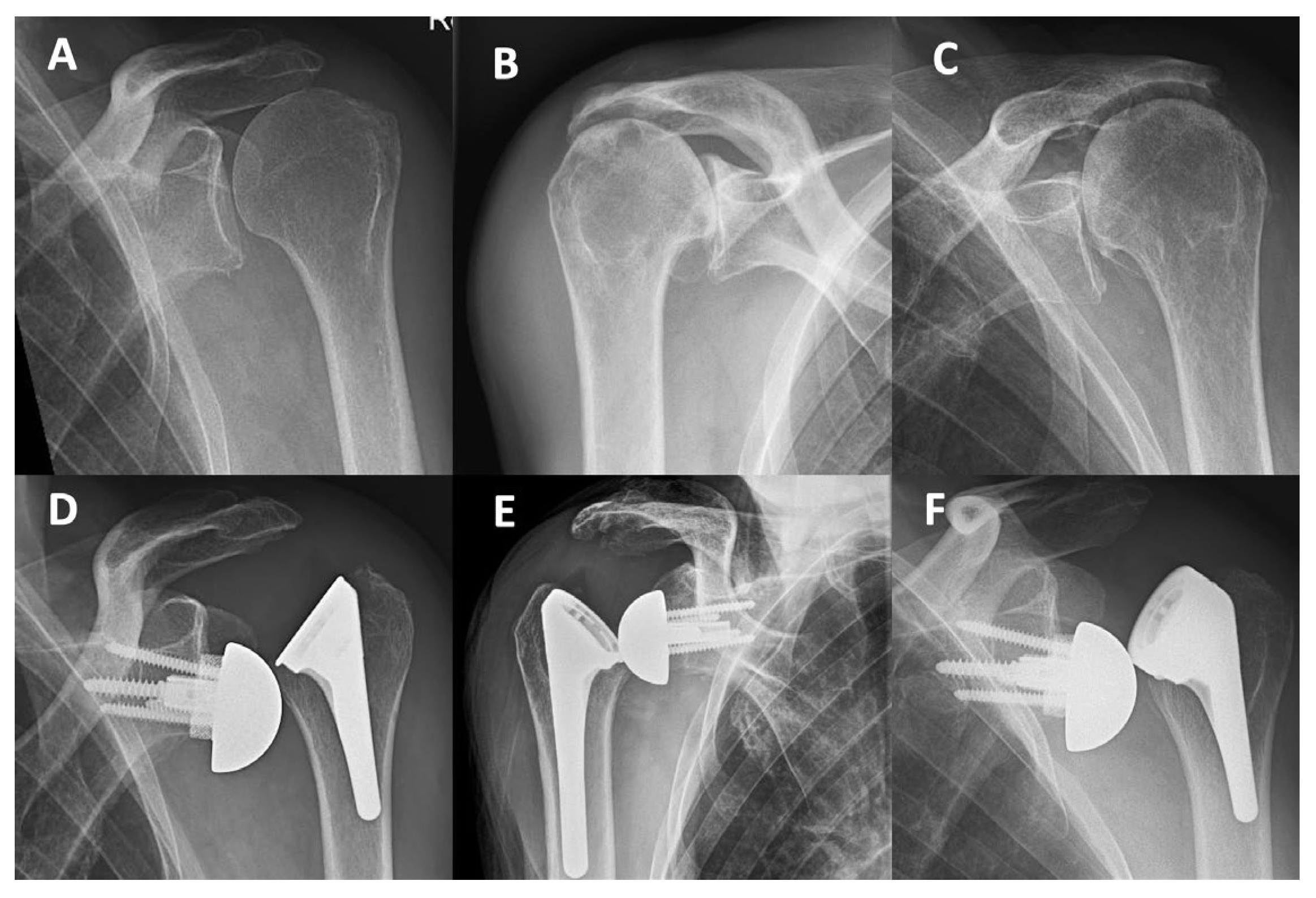

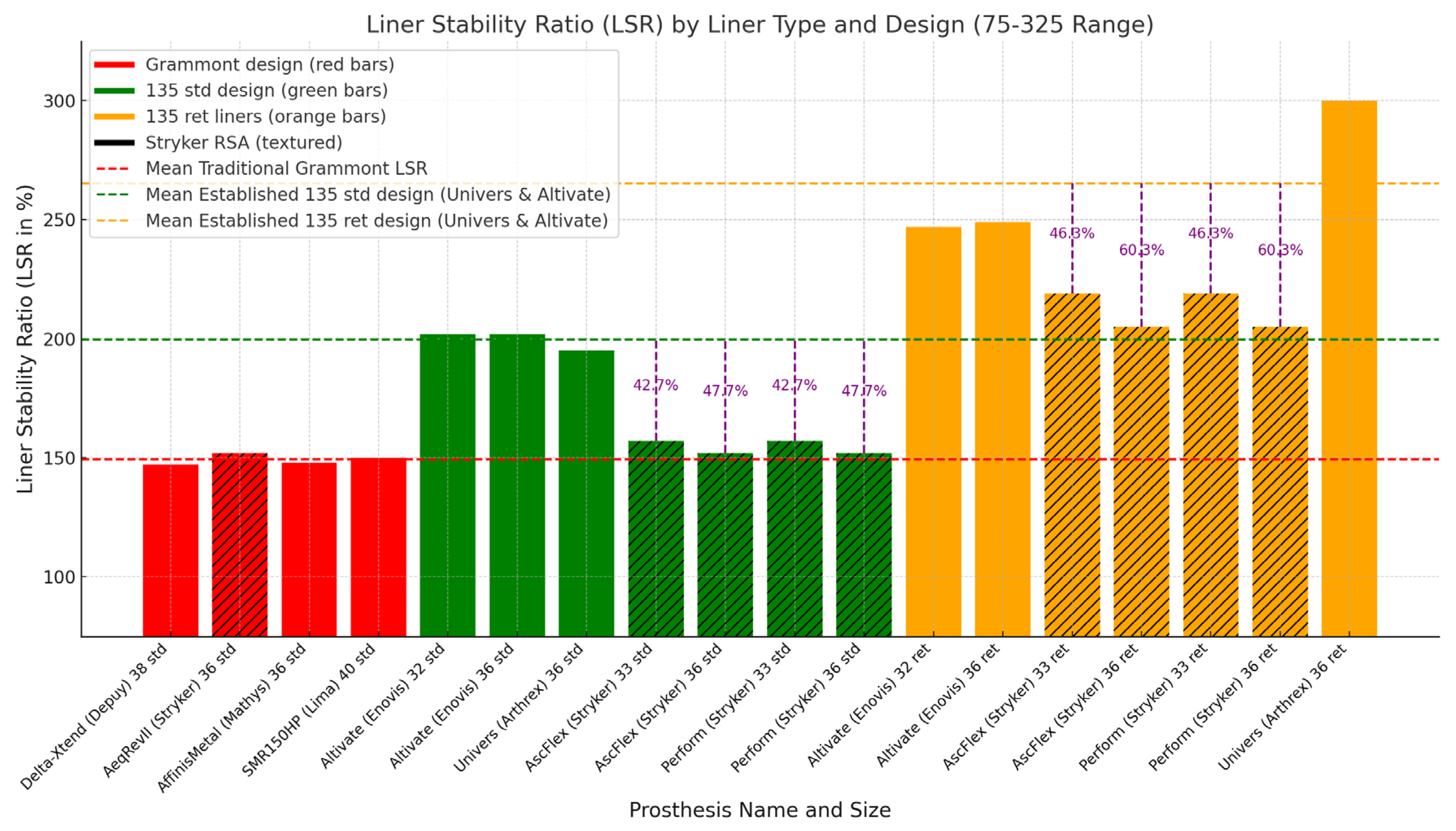

Background: In reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA), the neck-shaft angle (NSA) has trended downward from 155° to 135° to reduce scapular notching, but concerns about instability persist. To assess superior-lateral stability, we developed the intra-operative 2-hand-lever-test (2HLT). This study evaluates the 2HLT's effectiveness, the learning curve with a new implant, and compares liner characteristics of 155° and 135° systems. Methods: In a single-surgeon learning curve study, 81 RSA procedures with the new Perform stem (Stryker) were included. Outcomes included the 2HLT test applied in 65 cases, early dislocations, stem alignment, stem length, liner type/thickness, and complications. The early dislocation rate was compared to 167 prior Ascend Flex RSA procedures (Stryker). Liner characteristics of three 135° systems (Perform/Stryker; Univers/Arthrex; Altivate/Enovis) were compared to traditional 155° Grammont systems (Delta Xtend/DePuy; Affinis Metal/Mathys; SMR 150/Lima, Aequalis Reversed/Stryker), focusing on jump height (JH) and liner stability ratio (LSR). Results: In 75% (49/65) of cases, the 2HLT detected superior-lateral instability, influencing implant selection. The early dislocation rate in the Perform cohort was 4.9% (0% with retentive liners, 8% with standard liners) versus 0% in the Ascend Flex cohort. The mean effective NSA was 133° (127°-144°) for short Perform stems and 135° (129°-143°) for long stems. Long Perform stems significantly reduced varus outlier density below 132° and 130° (p=0.006, p=0.002). The 36mm Perform 135° standard liner has a JH of 8.1mm and LSR of 152%, markedly lower than the Altivate (10.0mm/202%) and Univers (9.7mm/193%) and similar to traditional 155° Grammont liners (8.1-8.9mm/ 147%-152%). Perform retentive liners have LSR values of 185%-219%, comparable to established 135° design standard liners (195%-202%). In the Perform cohort, early complications included 4 superior-lateral dislocations (all standard liners, LSR 147%-152%) requiring 4 revisions. Conclusions: The 2HLT effectively identified superior-lateral instability and guided implant selection. Perform standard liners have a lower LSR and JH than established 135° designs, contributing to superior-lateral instability, particularly with an effective NSA < 135°. Retentive Perform liners with an LSR > 184% have a similar LSR compared to standard liners of established 135° designs and effectively mitigated instability. We recommend discontinuing the use of non-retentive Perform RSA liners (LSR <158%).

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.2. Stem Alignment and Relationship to Stem Length

2.3. Review of Liner Stability

2.4. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Early Superior-Lateral Instability and Complications

3.2. Review of 155° Grammont and 135° Design Liners

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bauer, S.; Blakeney, W.G.; Wang, A.W.; Ernstbrunner, L.; Corbaz, J.; Werthel, J.-D. Challenges for Optimization of Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty Part II: Subacromial Space, Scapular Posture, Moment Arms and Muscle Tensioning. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, B.; Meisterhans, M.; Zindel, C.; Calek, A.-K.; Gerber, C. Computer-Assisted Analysis of Functional Internal Rotation after Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: Implications for Component Choice and Orientation. J. Exp. Orthop. 2023, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, B.S.; Chaoui, J.; Walch, G. The Influence of Humeral Neck Shaft Angle and Glenoid Lateralization on Range of Motion in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017, 26, 1726–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Blakeney, W.G.; Meylan, A.; Mahlouly, J.; Wang, A.W.; Walch, A.; Tolosano, L. Humeral Head Size Predicts Baseplate Lateralization in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Comparative Computer Model Study. JSES Int. 2024, 8, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, S.; Meylan, A.; Mahlouly, J.; Shao, W.; Blakeney, W.G. Dialing the Glenosphere Eccentricity Posteriorly to Optimize Range of Motion in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty. JSES Int. 2024, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collotte, P.; Gauci, M.-O.; Vieira, T.D.; Walch, G. Bony Increased-Offset Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty (BIO-RSA) Associated with an Eccentric Glenosphere and an Onlay 135° Humeral Component: Clinical and Radiological Outcomes at a Minimum 2-Year Follow-Up. JSES Int. 2022, 6, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neyton, L.; Nigues, A.; McBride, A.P.; Giovannetti de Sanctis, E. Neck Shaft Angle in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty: 135 vs. 145 Degrees at Minimum 2-Year Follow-Up. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023, 32, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Blakeney, W.G.; Wang, A.W.; Ernstbrunner, L.; Werthel, J.-D.; Corbaz, J. Challenges for Optimization of Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty Part I: External Rotation, Extension and Internal Rotation. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.S.; Roche, A.M.; Sullivan, S.W.; Gaal, B.T.; Dalton, S.; Sharma, A.; King, J.J.; Grawe, B.M.; Namdari, S.; Lawler, M.; et al. The Modern Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty and an Updated Systematic Review for Each Complication: Part II. JSES Int. 2020, 5, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, P.; Morin-Salvo, N.; Bessière, C.; Chelli, M.; Gauci, M.-O.; Lemmex, D.B. Bony Increased-Offset-Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty: 5 to 10 Years’ Follow-Up. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020, 29, 2111–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, P.; Morin-Salvo, N.; Gauci, M.-O.; Seeto, B.L.; Chalmers, P.N.; Holzer, N.; Walch, G. Angled BIO-RSA (Bony-Increased Offset-Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty): A Solution for the Management of Glenoid Bone Loss and Erosion. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017, 26, 2133–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschetti, E.; Ranieri, R.; Giovanetti de Sanctis, E.; Palumbo, A.; Franceschi, F. Clinical Results of Bony Increased-Offset Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty (BIO-RSA) Associated with an Onlay 145° Curved Stem in Patients with Cuff Tear Arthropathy: A Comparative Study. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020, 29, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, J.; Siljander, M.; Wiater, J.M. Instability in Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2018, 26, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.H.; Shin, S.-J.; McGarry, M.H.; Scott, J.H.; Heckmann, N.; Lee, T.Q. Biomechanical Effects of Humeral Neck-Shaft Angle and Subscapularis Integrity in Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014, 23, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melbourne, C.; Munassi, S.D.; Ayala, G.; Christmas, K.N.; Diaz, M.; Simon, P.; Mighell, M.A.; Frankle, M.A. Revision for Instability Following Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: Outcomes and Risk Factors for Failure. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023, 32, S46–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroder, P.; Herbst, E.; Pawelke, J.; Lappen, S.; Schulz, E. Large Variability in Degree of Constraint of Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty Liners between Different Implant Systems. Bone Jt. Open 2024, 5, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, S.; Imam, M.A.; Monga, P. Intraoperative Stability Assessment in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2019, 10, 617–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werthel, J.-D.; Walch, G.; Vegehan, E.; Deransart, P.; Sanchez-Sotelo, J.; Valenti, P. Lateralization in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Descriptive Analysis of Different Implants in Current Practice. Int. Orthop. 2019, 43, 2349–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Corbaz, J.; Athwal, G.S.; Walch, G.; Blakeney, W.G. Lateralization in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Walch, A.; Kremer, D. Cuff Arthropathy, Scapular Spine Fracture Non-Union, and Instability: Open Reduction, Internal Fixation & Simultaneous Reversed Shoulder Arthroplasty - A Case Report. J. Orthop. Case Rep. 2024, 14, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Traverso, A.; Walch, G. Locked 90°-Double Plating of Scapular Spine Fracture after Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty with Union and Good Outcome despite Plate Adjacent Acromion Fracture. BMJ Case Rep. 2020, 13, e234727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, S.; Keller, T.S.; Levy, J.C.; Lee, W.E.; Luo, Z.-P. Hierarchy of Stability Factors in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. 2008, 466, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Goebel, S.; Wang, K.; Raubenheimer, K.; Greene, A.; Verstraete, M. Intraoperative Joint Load Evaluation of Shoulder Postures after Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Cadaveric Study Using a Humeral Trial Sensor. Semin. Arthroplasty JSES 2022, 32, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.W.; May, A.; Blakeney, W.; Bauer, S.; Ebert, J. Clinical Significance of Intraoperative Glenohumeral Joint Load Evaluation Using a Novel Humeral Sensor in Navigated Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty. Semin. Arthroplasty JSES 2024, 34, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, E.V.; Sarkissian, E.J.; Sox-Harris, A.; Comer, G.C.; Saleh, J.R.; Diaz, R.; Costouros, J.G. Instability after Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018, 27, 1946–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrella, V.; Chelli, M.; Domos, P.; Ascione, F.; Boileau, P.; Walch, G. Risk Factors for Instability after Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty. Shoulder Elb. 2021, 13, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, T.; Bauer, S.; Walch, G.; Al-Karawi, S.; Blakeney, W. An Update on Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: Current Indications, New Designs, Same Old Problems. EFORT Open Rev. 2021, 6, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucas, M.; Borbas, P.; Vetter, M.; Loucas, R.; Ernstbrunner, L.; Wieser, K. Risk Factors for Dislocation After Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Orthopedics 2022, 45, e303–e308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, P.N.; Rahman, Z.; Romeo, A.A.; Nicholson, G.P. Early Dislocation after Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014, 23, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASES Complications of RSA Research Group; Lohre, R. ; Swanson, D.P.; Mahendraraj, K.A.; Elmallah, R.; Glass, E.A.; Dunn, W.R.; Cannon, D.J.; Friedman, L.G.M.; Gaudette, J.A.; et al. Predictors of Dislocations after Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Study by the ASES Complications of RSA Multicenter Research Group. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2024, 33, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, J.; Siljander, M.; Wiater, J.M. Instability in Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2018, 26, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, J.W.; Kim, R.; Ment, A.; Durso, J.; Joslin, P.M.N.; Lemos, J.L.; Novikov, D.; Curry, E.J.; Alley, M.C.; Parada, S.A.; et al. Outcomes and Complications of Primary Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty with Minimum of 2 Years’ Follow-up: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022, 31, e534–e544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, C.; Venishetty, N.; Jones, H.; Mounasamy, V.; Sambandam, S. Factors That Increase the Rate of Periprosthetic Dislocation after Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty. Arthroplasty Lond. Engl. 2023, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, T.; Werthel, J.-D.; Crowe, M.M.; Ortiguera, C.J.; Elhassan, B.; Sperling, J.W.; Sanchez-Sotelo, J.; Schoch, B.S. Shoulder Arthroplasty Is a Viable Option in Patients with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021, 30, 2484–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumstein, M.A.; Pinedo, M.; Old, J.; Boileau, P. Problems, Complications, Reoperations, and Revisions in Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011, 20, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werthel, J.-D.; Walch, G.; Vegehan, E.; Deransart, P.; Sanchez-Sotelo, J.; Valenti, P. Lateralization in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Descriptive Analysis of Different Implants in Current Practice. Int. Orthop. 2019, 43, 2349–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdic, S.; Athwal, G.S.; Wittmann, T.; Walch, G.; Raiss, P. Short Stem Humeral Components in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty: Stem Alignment Influences the Neck-Shaft Angle. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2021, 141, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameziane, Y.; Audigé, L.; Schoch, C.; Flury, M.; Schwyzer, H.-K.; Scaini, A.; Maggini, E.; Moroder, P. Mid-Term Outcomes of a Rectangular Stem Design with Metadiaphyseal Fixation and a 135° Neck-Shaft Angle in Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuff, D.J.; Pupello, D.R.; Santoni, B.G.; Clark, R.E.; Frankle, M.A. Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty for the Treatment of Rotator Cuff Deficiency: A Concise Follow-up, at a Minimum of 10 Years, of Previous Reports. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2017, 99, 1895–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Blakeney, W.G.; Lannes, X.; Wang, A.W.; Shao, W. Optimizing Stability and Motion in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty with a 135° Neck-Shaft-Angle: A Computer Model Study of Standard versus Retentive Humeral Inserts. JSES Int. 2024, 8, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.; Blakeney, W.G.; Goyal, N.; Flayac, H.; Wang, A.; Corbaz, J. Posteroinferior Relevant Scapular Neck Offset (pRSNO) in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty: Key Player for Motion and Friction-Type Impingement in a Computer Model. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 81 Perform stem RSA | 167 Ascend Flex stem RSA | |

| Mean age in years (range) | 74 (54-89) | 75 (57-91) |

| Gender Female Male |

55 (68%) 26 (32%) |

118 (71%) 49 (29%) |

| Diagnosis CTA MRCT OA Others |

35 22 24 0 |

56 31 69 11 |

| Liner Type | Jump Height d (mm) | Liner Stability Ratio (%) | Angle of Coverage (°) |

| Altivate (Enovis) 32 std* | 8.90 | 202 | 127 |

| Altivate (Enovis) 32 ret* | 10.00 | 247 | 138 |

| Altivate (Enovis) 36 std * | 10.00 | 202 | 127 |

| Altivate (Enovis) 36 ret* | 11.30 | 249 | 136 |

| Aequalis Ascend Flex (Stryker/Tornier) 33 std* | 7.65 | 157 | 115 |

| Aequalis Ascend Flex (Stryker/Tornier) 33 ret* | 9.65 | 219 | 131 |

| Aequalis Ascend Flex (Stryker/Tornier) 36 std* | 8.10 | 152 | 113 |

| Aequalis Ascend Flex (Stryker/Tornier) 39 ret* | 10.10 | 205 | 128 |

| Aequalis Ascend Flex (Stryker/Tornier) 39 std* | 8.55 | 147 | 112 |

| Aequalis Ascend Flex (Stryker/Tornier) 39 ret* | 10.55 | 194 | 125 |

| Aequalis Ascend Flex (Stryker/Tornier) 42 std* | 9.00 | 144 | 110 |

| Aequalis Ascend Flex (Stryker/Tornier) 42 ret* | 11.00 | 185 | 123 |

| Perform (Stryker/Tornier) 33 std* | 7.65 | 157 | 115 |

| Perform (Stryker/Tornier) 33 ret* | 9.65 | 219 | 131 |

| Perform (Stryker/Tornier) 36 std* | 8.10 | 152 | 113 |

| Perform (Stryker/Tornier) 36 ret* | 10.10 | 205 | 128 |

| Perform (Stryker/Tornier) 39 std* | 8.55 | 147 | 112 |

| Perform (Stryker/Tornier) 39 ret* | 10.55 | 194 | 125 |

| Perform (Stryker/Tornier) 42 std* | 9.00 | 144 | 110 |

| Perform (Stryker/Tornier) 42 ret* | 11.00 | 185 | 123 |

| Univers (Arthrex) 36 std* | 9.80 | 195 | 126 |

| Univers (Arthrex) 36 ret* | 12.30 | 300 | 143 |

| Univers (Arthrex) 42 std* | 11.40 | 195 | 126 |

| Univers (Arthrex) 42 ret* | 13.90 | 278 | 140 |

| Liner Type | Jump Height (mm) | Liner Stability Ratio (%) | Angle of Coverage (°) |

| Delta-Xtend (Depuy) 38 std** | 8.30 | 147 | 112 |

| Delta-Xtend (Depuy) 42 std** | 9.40 | 151 | 123 |

| Aequalis Reversed II (Stryker/Tornier) 36 std* | 8.10 | 152 | 113 |

| Aequalis Reversed II (Stryker/Tornier) 42 std* | 10.60 | 175 | 121 |

| Affinis Metal 147 (Mathys) 36 std** | 7.90 | 148 | 112 |

| Affinis Metal 147 (Mathys) 42 std** | 10.4 | 171 | 119 |

| SMR 150 (Lima) 40 std** | 8.90 | 150 | 113 |

| SMR 150 (Lima) 44 std** | 8.80 | 133 | 106 |

| No | Age |

Sex |

Diagnosis |

Baseplate size and offset |

Glenosphere size and eccentricity |

Stem size, length |

Liner type and thickness before dislocation |

LSR | Effective NSA |

Frankle Classification [15] 1. Compression 2. Containment 3. Impingement 4. Loosening |

2HLT | Revised to |

| 1 | 79 | M | MRCT | 25mm +8mm |

39mm +3mm |

2+ short |

Standard +3mm | 147% | 129° | 1. Normal/low 2.LSR: 147% 3. None 4. None |

+ | Standard 10° +12mm (spacer) |

| 2 | 79 | M | MRCT | 25mm +8mm |

39mm +3mm |

2+ short |

Standard 10° +12mm (spacer) |

147% | 139° | 1. High 2.LSR: 147% 3. None 4. None |

+ | Standard 10° Effective NSA 145° 42mm +15mm (spacer) |

| 3 | 84 | M | CTA | 25mm +10mm |

36mm +2mm |

3+ long |

Standard +6mm | 152% | 134° | 1. Normal 2.LSR: 152% 3. None 4. None |

+ | Standard +12mm |

| 4 | 77 | F | CTA | 25mm +10mm |

36mm +2mm |

2+ long |

Standard +6mm | 152% | 134° | 1. Normal 2. LSR: 152% 3. None 4. None |

+ | Retentive +12mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).