Level of Evidence: Therapeutic Level III

Introduction

Elective shoulder arthroplasty is an increasingly

common surgical intervention for treatment of degenerative pathologies of the

shoulder joint, since the first shoulder arthroplasty performed by Péan in the

1890s1. Shoulder arthroplasty is a complex procedure, and has

traditionally been performed on an inpatient basis, with patients admitted for

six to seven days post-surgery. One of the primary reasons for this is the high

level of postoperative pain, usually treated with hospital-based opioid therapy2,3.

Evidence suggests that early rehabilitation can improve functional outcomes

after shoulder arthroplasty, adding to the importance of postoperative pain

control4.

Recent developments in surgical and anaesthetic

techniques, however, have raised the possibility of performing ambulatory

shoulder arthroplasty. There is a growing trend in developed nations to perform

more surgeries as outpatient procedures, including many orthopaedic procedures5.

However, to date, this expansion in orthopaedics has largely been limited to

arthroscopic procedures- total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) and Hemi-shoulder

arthroplasty (HSA) are still largely performed in an inpatient setting.

Outpatient surgery is economically advantageous for both hospitals and

individual patients, and may allow for a better distribution of hospital

resources 6,7. On study from the United States has showed that

outpatient total shoulder arthroplasty can save up to USD $747 to $15,507 per

patient compared to inpatient management, and a total annual saving of $4.1M to

$349M 8. The practicality of performing TSA and HAS in an outpatient

setting was established when in 2006 Ilfeld et al. demonstrated the efficacy of

continuous interscalene nerve block (CISB) to control pain in patients discharged

to their homes after shoulder arthroplasty 2, and in 2008 when, in a

retrospective study of 16 patients, Gallay et al. reported the successful

implementation of a regional model of care for performing shoulder arthroplasty

as a day case with adequate postoperative care and analgesia 4. Two

studies demonstrated outpatient TSA to have a similar rate of complications as

inpatient TSA, however these studies only examined patients within a shorter

term 90 day postoperative period, and did not evaluate functional outcomes

between the two groups or in the long term 5,9,10. The aim of this

study, therefore, was to assess the complication rates of performing shoulder

arthroplasty on an outpatient basis through a larger, longer term comparison of

patient outcomes after day surgery vs a traditional inpatient approach, and to

compare shoulder function and pain in these patients. Our hypothesis was that

there would be no significant difference between inpatient and outpatient

arthroplasty with respect to complication rates, postoperative pain, and

functional outcomes.

Materials & Methods:

A retrospective cohort study was conducted to

assess the feasibility of performing shoulder arthroplasty as an outpatient

procedure. The main outcome assessed was the complication rate, widely defined

as any deviation from a standard, uneventful postoperative recovery and were

classified according as major or minor depending on their effect on long term

outcome. Secondary outcomes included physician-determined functional scores

concerning shoulder strength and range of motion, and patient-assessed pain

scores as per the L’Insalata Shoulder questionnaire11. All patients

undergoing primary total or hemiarthroplasty of the shoulder performed by a

single surgeon (G.A.C.M) between January 2004 and July 2012 were included in

the study. Approval was obtained from the appropriate institutional ethics

review board, and informed consent for data collection was obtained at the

first visit. Patients were assessed preoperatively, and followed up

postoperatively face-to-face at one week, six weeks, twelve weeks, and six months.

At two years post surgery, a further follow up was conducted by telephone.

Inclusion criteria included primary shoulder

arthroplasty performed by a single surgeon between 2004 and 2012 for

osteoarthritis and other arthropathies. Revision surgeries were excluded, and

reverse total shoulder arthroplasty procedures were also excluded, as these

have different indications and complication rates compared to primary shoulder

arthroplasty being performed to treat arthritis 12. Patients with

less than the minimum six months’ follow up were also excluded. All subjects

meeting these criteria were divided into two cohorts at the time of

preadmission clinic, an Inpatient group of patients admitted to hospital for a

minimum of one night following surgery, and an Outpatient group of patients

discharged on the day of their surgery. No randomisation was used in this

study. Initially, only a small number of patients were treated on an outpatient

basis. Following the completion in early 2007 of a new facility specialising in

day surgery, a decision was made to perform more surgeries as day cases.

Thereafter, the approach was to perform surgeries as day cases unless this was

contraindicated by patient factors such as patient illness, multiple

comorbidities, patient request, or failure to comply with preoperative

instructions. Intention-to-treat analysis was used.

Pre-operative care

Preoperatively, patients underwent examination by

the principal surgeon. This included clinical history, physical examination,

investigations, and the use of two standardised questionnaires, one

patient-reported, and one examiner-determined. The patient-reported

questionnaire is based on the L’Insalata self-administered shoulder

questionnaire, with proven validity and reliability as a clinical tool for

assessing pain and shoulder function8. In this questionnaire,

patients provide a rating of 1 to 5 for six questions related to pain,

stiffness, level of function, and overall satisfaction. In addition, two

questions on level of activity at work and sport are rated from one to four,

with four being the highest level. Physical examination involved assessment of

passive range of motion (ROM) by visual estimation, and strength testing with

the use of a handheld dynamometer, both assessment techniques which have been

previously validated13–15.

Peri-operative care

All patients were reviewed by the principal surgeon

and anaesthetist prior to surgery. For all patients, the procedure was carried

out under interscalene local anaesthesia, in the form of injected Ropivacaine

or equivalent agent, in conjunction with general sedation. Antibiotic

prophylaxis was administered intravenously on induction of anaesthesia. Surgery

was performed in the beach chair position, with a standard deltopectoral

approach. Tournier-Aqualis prostheses were used in both total and

hemiarthroplasties.

Post-operative care

Postoperatively, patients were observed in the

post-anaesthesia care unit and prescribed oral analgesia in the form of a

Paracetamol (1000mg) and Codeine Phosphate (60mg) combination and/or Tramadol

(50-100mg). Patients in the Inpatient group were discharged to the ward. There

they began early rehabilitation range-of-motion exercises. During this period,

any complications that arose were documented. Patients were discharged to their

homes after a minimum admission of one night. Patients in both groups were

placed in a shoulder immobilizer sling and a CryoCuff cooling device to be worn

for 48 hours after surgery. All patients were encouraged to begin passive range-of-motion

exercises from postoperative day one.

Patients in the Outpatient group were discharged to

their homes from the recovery bay. Patients were instructed not to drive

themselves home, and to stay home with a family member/carer for at least the

first 24 hours. These patients were given standardised written information for

aftercare as well as instructions for returning to hospital if required,

including a contact phone number.

At one week, six weeks, twelve weeks, and six

months patients returned for follow up where both patient-determined and

examiner-determined assessment was utilized as with the preoperative visit. At

a minimum of two year after surgery, patients were contacted by an examiner who

conducted a phone survey utilising questions from the patient-determined

questionnaire, in addition to several further questions on complications after

six months, readmissions to hospital, and any GP visits after six months

(Appendix 1).

Statistical Analysis

Data was analysed in an intention-to-treat fashion,

so all patients were assessed in the groups to which they were assigned. The

Inpatient group was compared to the Outpatient group at each time point.

For non-parametric data such as pain scores and

internal rotation range of motion (vertebral levels) the Mann Whitney Rank Sum

test was used to assess differences between inpatients and outpatients at each

time point.

For parametric data such as shoulder strength and

range-of-motion, the unpaired Student’s t-test was used to assess differences

between the two groups at each time point, with significance level set at 0.05.

The paired Student’s t-test was used to assess differences within each group

between preoperative and six-month postoperative timepoints.

Two-Way ANOVA with Bonferrnoi corrections was used

to assess two factors (the effect of time and the effect of mode of discharge)

between preoperative and follow-up time points.

Chi-square analysis was used to assess dichotomous

data, such as patient demographics and presence or absence of complications. Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaPlot v11 (Systat

Software, Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) with significance level set at 0.05.

Results

Complete data sets were available for 73 patients

who had a shoulder arthroplasty between 2004 and 2012, with a minimum of six

months follow up and of these, 40 patients had a minimum of two years follow-up

(average long term follow-up 5.8 years ± 3.2, range 2-9). There were 36

patients in the Inpatient group and 37 in the Outpatient group. Both groups

were well matched in terms of age, gender, type and duration of surgery (

Table 1). 72% (26/36) of inpatients and 68%

(25/37) of outpatients underwent total shoulder arthroplasty. 28% of inpatients

(10/36) and 32% (12/37) of outpatients underwent hemiarthroplasty. All

procedures were indicated for osteoarthritis. Operation time for inpatients was

93±23 minutes (mean ± standard deviation), and for day cases 92±29 minutes.

Outpatients had a similar duration of symptoms prior to surgery. Of this

starting cohort, 22 patients in the Inpatient group and 18 in the Outpatient

group responded to follow up attempts at a minimum of two years after surgery.

There were showed no significant differences between the Inpatient and

Outpatient groups at long term follow up.

Primary Outcome

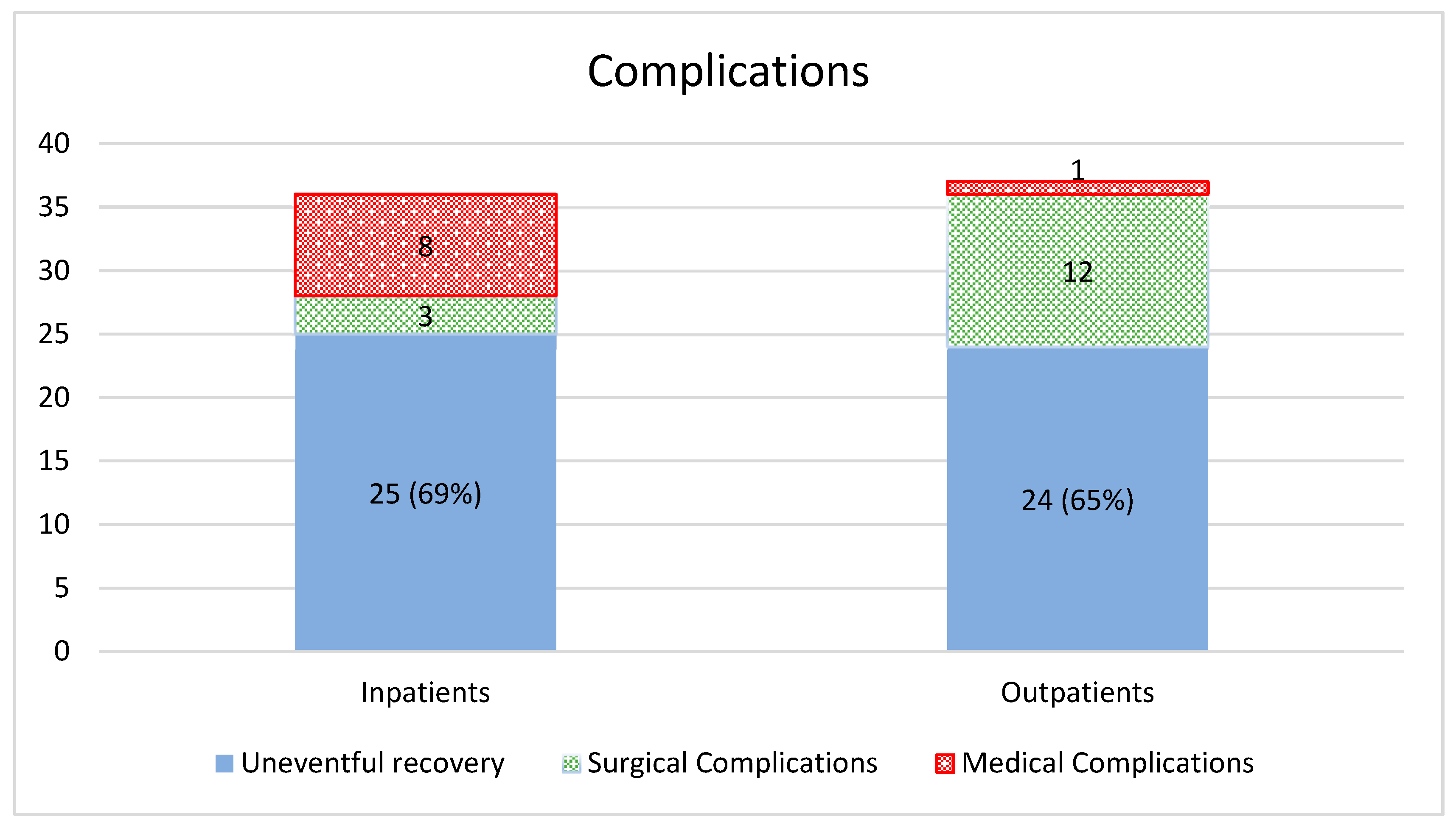

The primary outcome for the study was uneventful

recovery, defined as nil hospitalisations or complications reported within six

months (the duration of standard post-operative follow-up at our institution).

Within this time frame 25/36 inpatients (69%) had uneventful recoveries

compared to 24/37 outpatients (65%) (p = 0.17) (

Figure 1).

Of the 11 inpatients who experienced complications

within six months (

Table 2), there were

three orthopaedic complications (3/11, 27%). One patient had an intraoperative

bleed, and hemiarthroplasty was performed instead of the planned total shoulder

arthroplasty. One patient from the Inpatient group suffered from a ruptured

long head of biceps within a year of the operation. One patient dislocated

their shoulder six weeks after surgery. There were no reoperations.

The remainder of the complications in the inpatient

group were medical complications (8/11, 73%). Two patients had an extended

admission due to fever, and two more for slight nausea in recovery. Other

complications in the Inpatient group included postoperative admission for

dyspnoea, disorientation, supplementary oxygen requirement, and one

precautionary case of dysrhythmia detected during the operation, with

investigations being normal.

Of the 13 day case (ambulatory care) patients who

experienced complications (

Table 3), the

majority were surgical complications (12/13, 92%).

There were two cases of infection, one superficial

skin infection treated with surface debridement, and one staphylococcus

aureus infection which required debridement, a washout of the joint, and

intravenous flucloxacillin treatment. One patient had a haematoma drained within

two months of surgery. One patient suffered weakness and paraesthesia over the

ulnar nerve distribution, presumed to have been caused by damage to the

brachial plexus during placement of the interscalene block. Another suffered a

radial nerve palsy and Dupuytren’s contracture, which resolved within six

months. In one case, hemiarthroplasty was performed instead of total

arthroplasty after a surgical bleed. One patient fell onto the shoulder two

months after surgery, received arthroscopic debridement and gentle manipulation

under anaesthetic a month later, and eventually underwent revision total

shoulder arthroplasty two years after the original operation. Another patient

suffered an episode of dysfunction of wrist extension, elbow flexion

dysfunction, with associated C6/C7 numbness. Other complications in the

Outpatient group included readmission one day after release for hypotension,

one case of bruising and persistent postoperative pain and bruising, one case

of trapezius discomfort, and case of postoperative stiffness. The sole medical

complication (1/13, 8%) was one case of recurrent syncopal episode within a

month of surgery. There were 4 reoperations.

Of patients contacted at two years post-surgery, 5%

(1/22) of inpatients and 11% (2/18) of outpatients reported readmission to

hospital within six months of their operation (p = 0.43), and there was no

statistically significant difference. One outpatient reported admission to

hospital for problems with the treated shoulder after six months post-surgery,

whereas zero inpatients required readmission. One outpatient in the long-term follow-up

cohort underwent revision surgery, whereas nil inpatients had required revision

surgery. At long term follow up, 39% (7/18) of outpatients reported GP visits

concerning their treated shoulders, compared with 9% (2/22) of inpatients (p =

0.02).

Secondary Outcomes

Passive Range of Motion

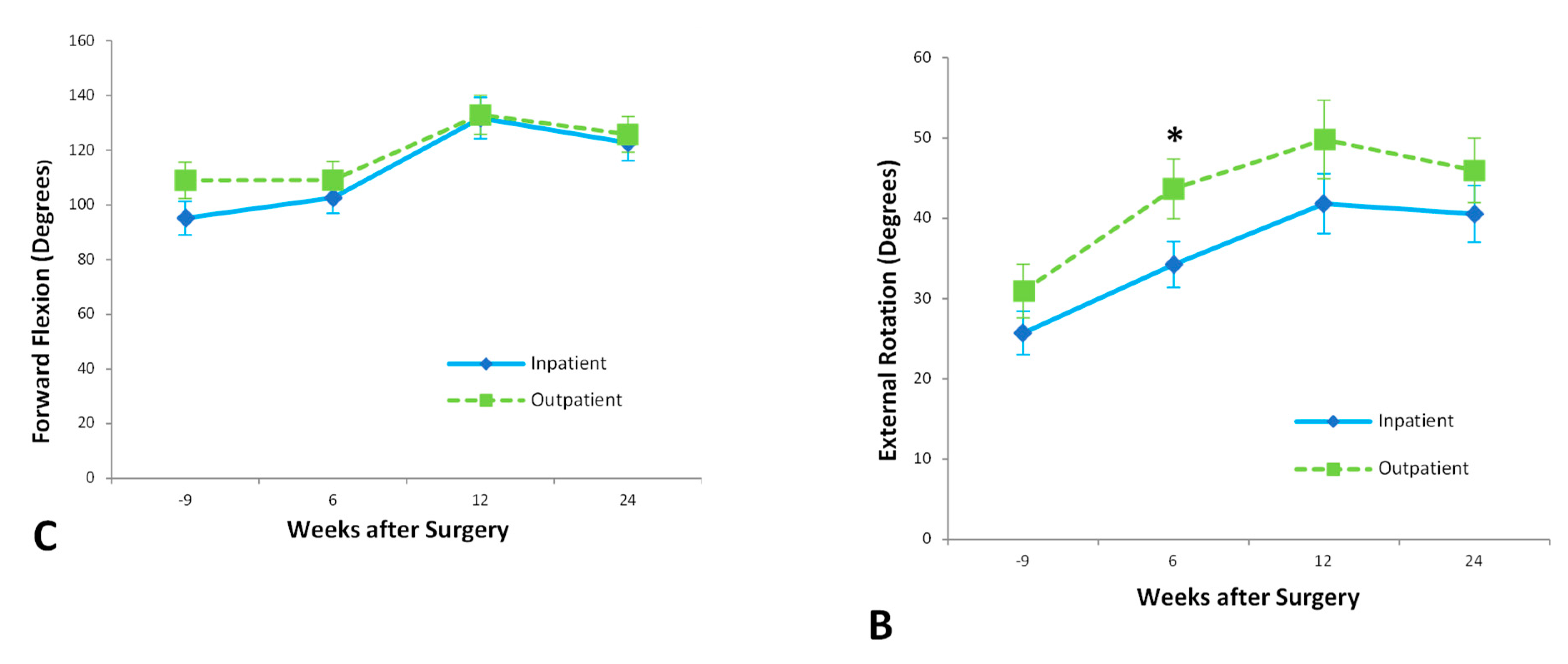

From pre-operative assessment to six month follow

up, patients who underwent shoulder arthroplasty as inpatients improved

significantly in abduction (p=0.005), external rotation (p=0.0002), and

internal rotation (p=0.045) passive range of motion, but showed no

statistically significant improvement in forward flexion. Outpatients showed

statistically significant improvement in all movements of passive range of

motion: abduction (p=0.01), external rotation

(p<0.0001), internal rotation (p=0.001) and forward flexion (p=0.02).

Outpatients achieved 41±4° of external rotation at six weeks after surgery, compared to

31±3° of external rotation achieved by

inpatients at the same time point (p<0.05). Two Way ANOVA analysis, however,

suggested that time was the only significant factor in this difference

(p=0.007).

At six weeks, outpatients had achieved a score of

5±1 on internal rotation (corresponding with vertebral level L5), significantly

better than the inpatient score of 3±1 (S2) (p=0.05) (

Figure 2).

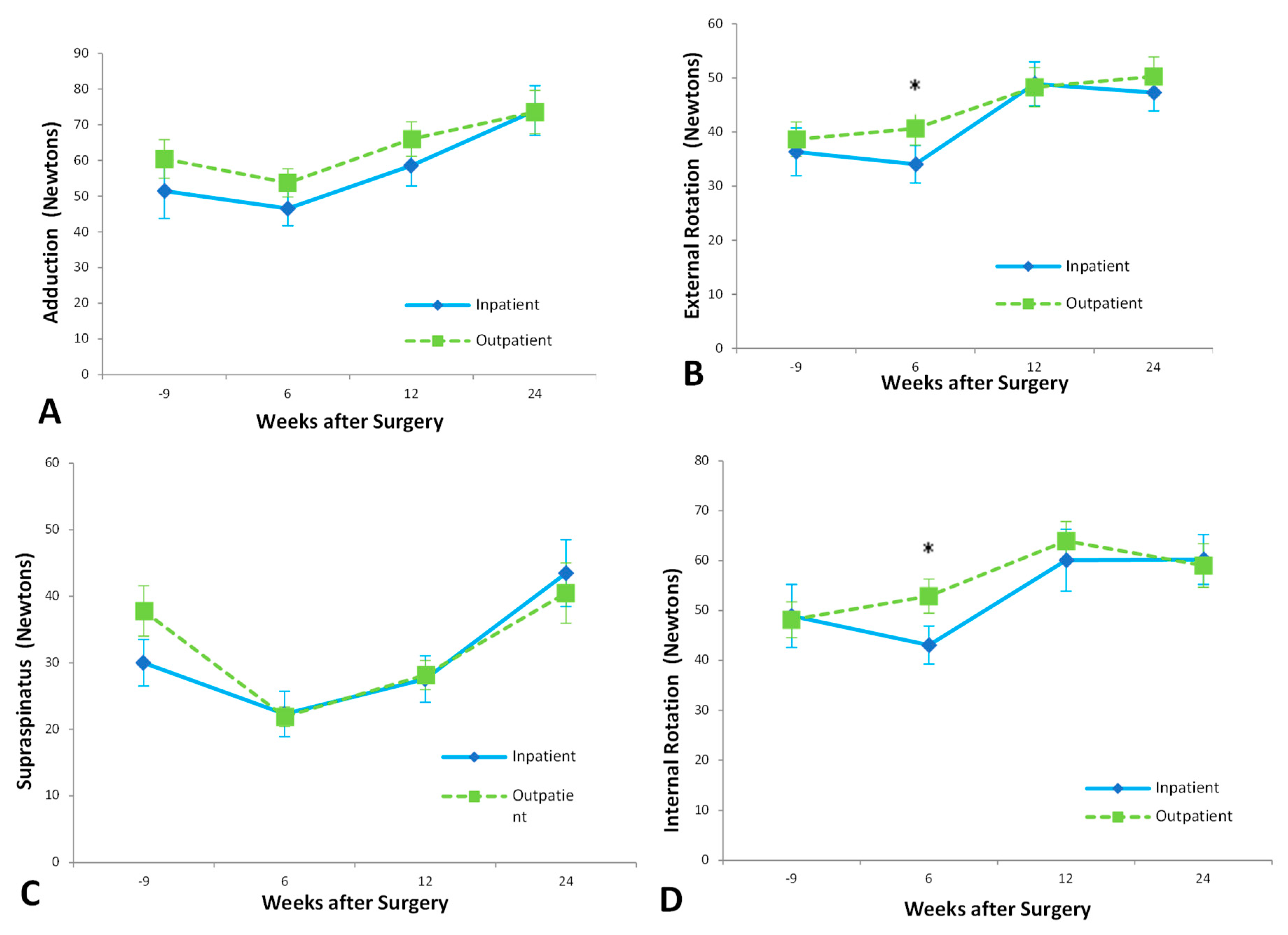

Strength

Patients in the Inpatient group demonstrated a significant improvement in lift-off strength (p=0.03) but did not show any statistically significant improvement over baseline measurements in supraspinatus strength, adduction strength, internal rotation or external rotation strength within six months of surgery. At six months post-surgery, the Outpatient group had improved significantly in internal rotation (p=0.01), external rotation (p<0.001), and adduction strength (p=0.03) compared to preoperative levels. Outpatients showed no significant improvement in supraspinatus or lift-off strength.

At six weeks’ follow up, outpatients were significantly stronger than inpatients. External rotation strength at six weeks for the Outpatient group was 39±4 N, while Inpatient strength was 29±4 N (p=0.05) (

Figure 3). Outpatients were significantly stronger on internal rotation six weeks after surgery, with a mean strength of 52±4 N compared to a mean Inpatient strength of 39±4 N (p=0.03).

At twelve weeks after surgery, outpatients were significantly stronger than inpatients on lift-off testing. Lift-off strength in the Outpatient group was 26±4 N, significantly higher than the Inpatient strength of 14±4 N (p=0.05). Two Way ANOVA analysis indicated patient discharge as the main cause of this difference (p=0.010), with subject matching playing a less important role (p=0.047) and time insignificant.

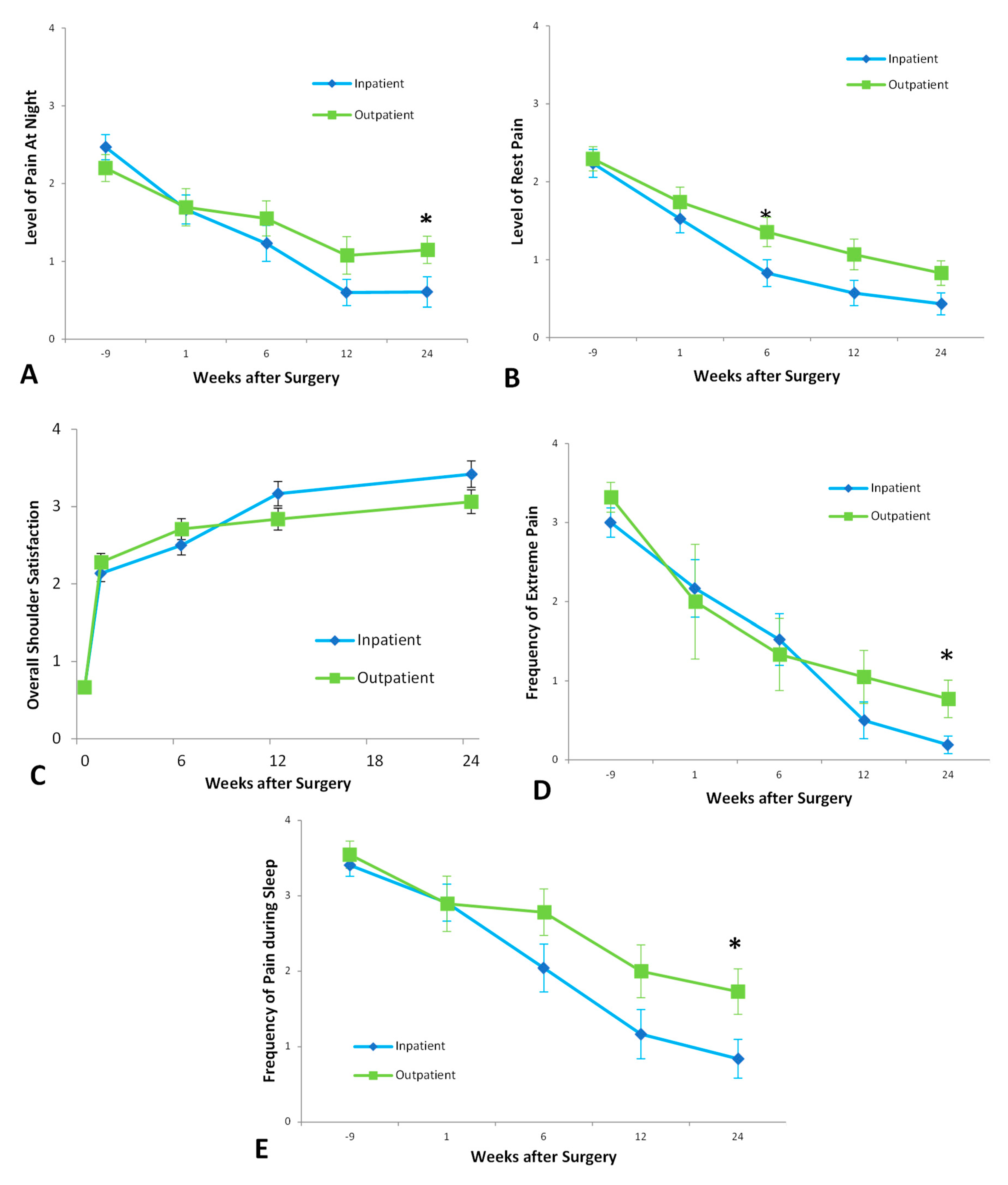

Patient Determined Outcomes

Inpatients showed a significant improvement in frequency of extreme pain, pain at night, and pain with activity; severity of pain at rest, at night, and with overhead activity; difficulty with overhead activity, and activity behind the back; stiffness, and overall shoulder rating. In all of these outcomes, p<0.0001 except for difficulty with overhead activity, where p=0.0002.

Outpatients likewise showed a significant improvement in all the above outcomes, with p<0.0001 for all outcomes except difficulty with overhead activity (p=0.010) and difficulty with activity behind the back (p=0.010).

Six weeks after surgery, the Outpatient group experienced more pain at rest than inpatients, with a mean pain score between ‘Moderate’ and ‘Mild,’ significantly higher than the Inpatient mean score just below ‘Mild,’ (p=0.0346) (

Figure 4).

At six months’ follow up, Outpatients experienced more frequent and more severe pain at night. Outpatients had a mean of ‘Weekly’ night pain, significantly higher than the Inpatient mean of ‘Monthly,’ (p=0.0278). For the Outpatient group, mean pain scores for pain at night were above ‘Mild,’ significantly higher than the Inpatient mean between ‘Mild’ and ‘None,’ (p=0.0093).

Outpatients also experienced extreme pain more frequently at six months post-surgery. The Outpatient group had a mean of ‘Monthly’ extreme pain at six months after surgery, compared to a mean of ‘Never’ for the Inpatient group (p=0.04). Two Way ANOVA analysis suggested that patient discharge was not a significant source of variation (p=0.05), with only time significant (p<0.0001). When asked to rank overall shoulder satisfaction, there was no significant difference between the two groups at any timepoint.

Outpatients had a higher frequency of pain at rest at 6 months compared to inpatients. There was no significant difference with regards to frequency of extreme pain at any timepoints.

Discharge Preference at Minimum Two Years Followup

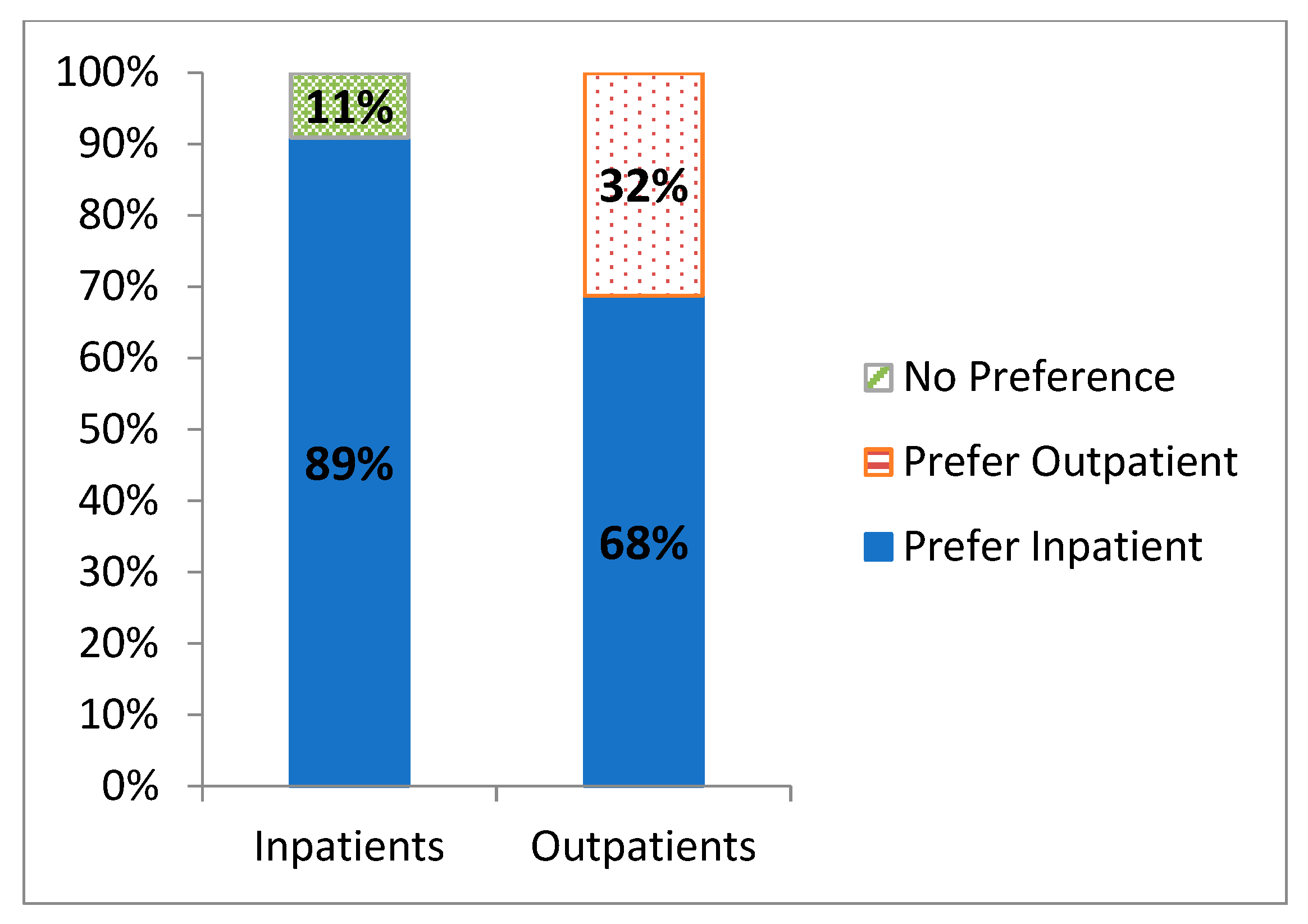

At a minimum of two years followup, the majority of the Inpatient group (16/18, 89%) indicated that they would prefer inpatient admission after any future shoulder arthroplasty (

Figure 5), with the remaining 11% (2/18) having no clear preference. In the Outpatient group, 32% (7/22) indicated a preference for outpatient surgery, but the remaining 68% (15/22) expressed a preference for inpatient admission. Compared to outpatients, inpatients were more comfortable repeating their treatment setting for future arthroplasty (16/18) compared to outpatients (7/22) (p = 0.0002).

Discussion

Performing shoulder arthroplasty as a day case in selected patients resulted in a complication rate equivalent to that of the traditional inpatient approach at 6 months postoperatively. There were no significant differences between Inpatient and Outpatient groups in terms of need for revision surgery, or readmission to hospital, within a minimum of two years post surgery. Outpatients visited a GP with regards to their shoulder more often, had an inferior pain experience, and expressed a preference for inpatient surgery if for future arthroplasty. Nevertheless, our data showed that having shoulder arthroplasty as an inpatient or an outpatient was not associated with significant differences in the long-term complication rates.

Regarding complication rates between the two groups, our findings are consistent with other literature. Cimino et al16 performed a meta-analysis which demonstrated no significant difference between the two groups in complications, readmission, revision, or infection. Leroux et al17 also did not note any statistically significant differences between these groups in terms of 30-day complication rates, and noted high patient satisfaction within their outpatient cohort.

Overall, both groups experienced similar improvements in range of motion and strength, with the outpatient group having greater strength and range of motion at 6 weeks. Both Inpatient and Outpatient groups achieved a significant reduction in pain frequency and severity and continued to improve beyond six months. However, outpatients did experience a higher frequency of extreme pain at 6 months, and pain at night by 6 months. There was also a trend at 6 months post-surgery towards increased pain with overhead movements, increased pain with activity, and a widening difference in overall shoulder satisfaction in outpatients compared to inpatients at this timepoint. Regardless, these disparities between inpatients and outpatients at the 6-month timepoint appear to have largely resolved by one-year post-surgery.

At long term follow up, 39% (7/18) of outpatients reported GP visits concerning their treated shoulders, compared with just 9% (2/22) of inpatients (p = 0.02). Furthermore, most patients expressed preference to have future arthroplasty in an inpatient admission. It is perhaps understandable that patients who experienced perioperative complications would opt for an inpatient route in their next admission in their hindsight as it may be perceived as the “safer option” given the longer period of postoperative monitoring and care. More notable, is that of patients who had their arthroplasty as an outpatient, 68% preferred future arthroplasty to occur in an inpatient. This suggests that while outpatient arthroplasty yields excellent functional outcomes, many patients did not prefer this treatment setting. While our results show that outpatient shoulder arthroplasty is feasible, this finding raises the question of what can be done to improve the patient experience in this group. This difference in patient satisfaction may possibly be attributed to the Outpatient group experiencing worse pain in the early postoperative period, as reflected by these patients requiring additional visits to the GP with concerns of their shoulder. Rauck et al18 performed a retrospective review of satisfaction in patients that underwent reverse shoulder arthroplasty and determined that satisfaction post operation was strongly correlated with improvements in pain and outcomes scores. Menendez et al19 reported that the strongest predictors of severe postoperative pain post shoulder arthroplasty include preoperative chronic opioid use and depression- they concluded that addressing psychological and social determinants of health may make a significant difference in the pain experience post operation. Therefore, frequent outpatient evaluation and management of these patients’ mental health and pain may be useful in ensuring greater pain and patient satisfaction in patients undergoing outpatient shoulder arthroplasty. Additionally, they also noted that patients reporting severe pain stayed longer in hospital (2.9 days vs 2.0 days) compared to those with pain <75th percentile. Therefore, patients who are at risk of severe postoperative pain may not be ideal candidates for day arthroplasty and may require a longer admission than other patients.

Limitations

An important limitation in our study is that as a retrospective cohort study, there was no randomisation or blinding in our trial, which introduces the potential for selection bias. The decision to proceed with day surgery or inpatient admission was made on an individual basis by the principal surgeon. As only one principal surgeon was involved in the decision-making of the decision for day surgery vs inpatient admission, this impacts the external validity of the study results. Patients with health problems contraindicating day surgery were allocated to the inpatient group, which may bias the results. Preoperative narcotic usage and mental health were not consciously considered in the decision-making, which may significantly influence the patients’ pain experience postoperatively. It should be noted however that the two groups were equally matched with regards to many preoperative parameters: there were no preoperative differences between the groups with regards to age, gender, preoperative pain, and preoperative function. Goltz et al.,20 created a predictive patient selection tool for prolonged hospital admission post outpatient shoulder arthroplasty which included factors such as age, sex, cardiac arrhythmia, electrolyte disorder, marital status, ASA, diabetes, and coagulation deficiency – these factors were similar to those used by the senior surgeon when deciding which patients were suitable to be inpatients.

The retrospective design also meant patients’ data were collected at different time points for the most recent follow up. Data for the first six months after surgery were collected prospectively, however all the ‘minimum two year’ follow-up phone calls were conducted in 2013. The time between surgery and this follow-up therefore ranged from two year to nine years. The sample size was therefore decreased roughly by half at the two year follow up.

One of the strengths of our study was the large sample size of 73 patients, which was one of the largest published studies on the outcomes of shoulder arthroplasty performed as a day case. While the study was not randomised, statistical analysis reveals that the two study cohorts were similar, with no significant differences in any major demographic details.

Conclusion

Outpatients were not more likely to experience complications, be readmitted to hospital, or require revision surgery than inpatients. Patients who underwent inpatient shoulder arthroplasty experienced significantly less pain at three to six months after surgery, and these patients were less likely to seek support from their family physician. Functionally, outpatients performed significantly better than inpatients at several time points, and by six months had slightly greater range of motion and strength outcomes than had inpatients. Our outcome findings suggest that there are advantages and disadvantages of performing shoulder arthroplasty as a day case, however patients prefer inpatient arthroplasty overall.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work: Conceptualization, GACM; Methodology, GACM; Software, PL; Validation, PL; Formal Analysis, SR; Investigation, SR and BL; Data Curation, SR and BL; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, SR; Writing – Review & Editing, GACM; Visualization, SR; Supervision, GACM; Project Administration, GACM

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee (12/310, LNR/13/POWH/186).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for data collection was obtained from patients at their first visit.

Data Availability Statement

The Data will be made available in a publicly accessible repository

Conflicts of Interest

Author G.A.C.M declares the following conflicts of interest: Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery: Editorial or governing board Shoulder and Elbow: Editorial or governing board Smith & Nephew: Paid consultant; Research support

References

- Buck, F.M.; Jost, B.; Hodler, J. Shoulder arthroplasty. European radiology 2008, 18, 2937–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilfeld, B.M.; Wright, T.W.; Enneking, F.K.; Mace, J.A.; Shuster, J.J.; Spadoni, E.H.; Chmielewski, T.L.; Vandenborne, K. Total Shoulder Arthroplasty as an Outpatient Procedure Using Ambulatory Perineural Local Anesthetic Infusion: A Pilot Feasibility Study. Obstet. Anesthesia Dig. 2005, 101, 1319–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizvi, S.M.T.; Bishop, M.; Lam, P.H.; Murrell, G.A. Factors Predicting Frequency and Severity of Postoperative Pain After Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair Surgery. Am. J. Sports Med. 2020, 49, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallay, S.H.; Lobo, J.J.A.; Baker, J.; Smith, K.; Patel, K. Development of a regional model of care for ambulatory total shoulder arthroplasty: a pilot study. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 2008, 466, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memtsoudis, S.G.; Kuo, C.; Ma, Y.; Edwards, A.; Mazumdar, M.; Liguori, G. Changes in anesthesia-related factors in ambulatory knee and shoulder surgery: United States 1996-2006. Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine 2011, 36, 327–331. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, J.; Mould, G. Ambulatory Care and Orthopaedic Capacity Planning. Heal. Care Manag. Sci. 2005, 8, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouholamin, E.; Harris, D.; Jamieson, A.M. Day surgery: an economical way to reduce waiting lists. Journal of hand surgery (Edinburgh, Scotland) 1990, 15, 366–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhaus, M.; Shim, S.; Lamba, N.; Makhni, E.; Kadiyala, R. Outpatient total shoulder arthroplasty: A cost-identification analysis. J. Orthop. 2018, 15, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brolin, T.J.; Mulligan, R.P.; Azar, F.M.; Throckmorton, T.W. Neer Award 2016: Outpatient total shoulder arthroplasty in an ambulatory surgery center is a safe alternative to inpatient total shoulder arthroplasty in a hospital: a matched cohort study. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2016, 26, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farng, E.; Zingmond, D.; Krenek, L.; SooHoo, N.F. Factors predicting complication rates after primary shoulder arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2011, 20, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L'Insalata, J.C.; Warren, R.F.; Cohen, S.B.; Altchek, D.W.; Peterson, M.G. A Self-Administered Questionnaire for Assessment of Symptoms and Function of the Shoulder. Minerva Anestesiol. 1997, 79, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, B.; Ahearn, N.; Tasker, A.; Wakeley, C.; Sarangi, P. Shoulder arthroplasty. Part 1: Prosthesis terminology and classification. Clin. Radiol. 2012, 67, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, K.; Walton, J.R.; Szomor, Z.L.; Murrell, G.A. Reliability of 3 methods for assessing shoulder strength. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002, 11, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, K.; Walton, J.R.; Szomor, Z.L.; Murrell, G.A. Reliability of five methods for assessing shoulder range of motion. Aust J Physi-other. 2001, 47, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronquillo, J.C.; Szomor, Z.; Murrell, G.A. Examination of the shoulder. Techniques in Shoulder & Elbow Surgery 2011, 12, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Cimino, A.M.; Hawkins, J.K.; McGwin, G.; Brabston, E.W.; Ponce, B.A.; Momaya, A.M. Is outpatient shoulder arthroplasty safe? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2021, 30, 1968–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroux, T.S.; Zuke, W.A.; Saltzman, B.M.; Go, B.; Verma, N.N.; Romeo, A.A.; Hurst, J.; Forsythe, B. Safety and patient satisfaction of outpatient shoulder arthroplasty. JSES Open Access 2018, 2, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauck, R.C.; Ruzbarsky, J.J.; Swarup, I.; Gruskay, J.; Dines, J.S.; Warren, R.F.; Dines, D.M.; Gulotta, L.V. Predictors of patient satisfaction after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2019, 29, e67–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menendez, M.E.; Lawler, S.M.; Ring, D.; Jawa, A. High pain intensity after total shoulder arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2018, 27, 2113–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goltz, D.E.; Burnett, R.A.; Levin, J.M.; Wickman, J.R.; Belay, E.S.; Howell, C.B.; Risoli, T.J.; Green, C.L.; Simmons, J.A.; Nicholson, G.P.; et al. Appropriate patient selection for outpatient shoulder arthroplasty: a risk prediction tool. J. Shoulder Elb. Surg. 2021, 31, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).