1. Introduction

Anterior shoulder instability refers to a disruption of the soft tissue and/or bony structural integrity that results in the humeral head dislocating from the glenohumeral joint. It is a common condition, particularly affecting young males in their 20s; and the shoulder is the most frequently dislocated joint in the human body. The most common cause is trauma to the capsulolabral structures, although bony damage is also frequently observed. Clinically, the condition ranges from partial subluxation to complete dislocation, often accompanied by injury to surrounding structures. Anterior dislocations account for approximately 95% of all shoulder dislocations [

1,

2,

3].

Shoulder instability is commonly classified based on its cause, chronicity, and the direction of dislocation. Traumatic injuries, often abbreviated as TUBS (Trauma, Unilateral, Bankart lesion, Surgery), are the most prevalent and are typically precipitated by trauma, often resulting in structural damage. In contrast, atraumatic injuries, abbreviated as AMBRI (Atraumatic, Multidirectional, Bilateral, Rehabilitation first, Inferior capsular shift if surgery), generally occur in the absence of a single precipitating event. These injuries involve multiple microtraumas, leading to instability in multiple directions [

3].

Currently, the two main surgical treatments are

Bankart repair and the

Latarjet procedure [

3,

4]. However, certain patient subgroups may benefit from a novel technique that combines elements of both. In this context, dynamic anterior stabilization may offer a promising solution.

A further distinction is made between first-time and recurrent dislocations. The highest risk of shoulder stability is maintained by both static and dynamic stabilizers. Disruption of any of these components can predispose the joint to instability. The static stabilizers include the osseous anatomy, labrum, glenohumeral articulation, joint capsule, and negative intra-articular pressure [

2,

3].

Understanding the mechanisms behind shoulder instability requires a closer look at the anatomy. The shoulder is a complex anatomical unit composed of several joints—most importantly the glenohumeral joint—as well as capsuloligamentous and musculotendinous structures that work together to stabilize the shoulder while allowing movement across multiple planes [

1,

4].

The glenohumeral joint is a ball-and-socket, multiaxial joint formed by the articulation of the large humeral head with the shallow glenoid fossa of the scapula, which is encircled by the labrum. The glenoid fossa contacts only about one-third of the humeral head, enabling a wide range of motion in axial, sagittal, coronal, and scapular planes. These movements are primarily driven by the rotator cuff and deltoid muscles, among others, which explains the shoulder’s inherent susceptibility to dislocation [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

Shoulder instability implies varying degrees of damage to the static and/or dynamic stabilizers. The inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL) is one of the most critical structures in maintaining shoulder stability [

1]. A

Bankart lesion—defined as a detachment of the IGHL along with avulsion of the anteroinferior labrum from the glenoid—is a hallmark injury associated with anterior instability [

5]. This lesion compromises both the labrum’s bumper-like function and the restraining force of the IGHL, particularly when the shoulder is in abduction and external rotation. As a result, the risk of anterior humeral head dislocation is significantly increased.

When the injury involves a fracture of the osseous glenoid rim, it is referred to as a bony Bankart lesion, which also occurs frequently. Additionally, an impaction fracture on the superolateral posterior aspect of the humeral head—caused by contact with the glenoid rim during dislocation—is known as a Hill-Sachs lesion. [

6].

Following a single dislocation event, the osseous, ligamentous, and labral structures may not heal completely, often resulting in residual laxity or deformity. With repeated dislocations, bone damage typically worsens, leading to progressively reduced joint stability. It is now well established that patients with chronic shoulder instability frequently exhibit both soft tissue and osseous defects—referred to as “bipolar” bone loss. This helps explain why soft tissue repair alone may fail in certain cases. [

7]

In current clinical practice, decision-making regarding treatment for shoulder instability places significant emphasis on the evaluation of bone loss. A glenoid rim defect involving more than 20% is generally considered an indication for bony reconstruction. Similarly, a severe Hill-Sachs lesion often necessitates a surgical approach that includes bone augmentation [

3].

Glenohumeral instability is also a recognized risk factor for joint degeneration. Importantly, degenerative changes may occur even after stabilizing procedures, as these interventions can alter normal joint biomechanics and loading patterns [

1].

The bone loss threshold for treating shoulder instability remains debated, but generally it is accepted that glenoid bone loss more than 20-25% should be treated with bone augmentation methods, by

Latarjet procedure [

1]. Complications after surgical treatment reported in 5–15% of cases, can include neurovascular injury—especially to the musculocutaneous and axillary nerves—as well as graft-related issues like nonunion or malposition. Additionally, long-term radiographic osteoarthritis may develop in some patients 10–20 years after surgery [

3,

8].

Patients with anterior shoulder instability and no significant bone loss are typically treated with a Bankart repair. The goal of this procedure is to surgically reattach the detached labrum and associated ligamentous structures to restore the static stabilizing function of the anterior capsule. It is indicated in cases of Bankart lesions with minimal or no osseous involvement. Specifically, the glenoid bone loss should be below the critical threshold of 20%, and the Hill-Sachs lesion must be non-engaging [

1,

2,

3].

Bankart repairs generally yield excellent clinical outcomes; however, the primary concern is the risk of recurrence or redislocation. Known risk factors for recurrence include younger age, male sex, participation in competitive collision sports, and unaddressed bone defects. One of the advantages of the Bankart repair is its low complication rate, as it does not involve osteotomy or hardware placement, unlike the

Latarjet procedure. The main long-term concern is the potential development of glenohumeral osteoarthritic changes [

3,

4].

Dynamic anterior stabilization (DAS) is a novel surgical technique for treating chronic anteroinferior glenohumeral instability. It presents an alternative to the currently used

Bankart and

Latarjet procedures, aiming to reduce associated complications and revision surgeries. DAS combines some advantages of bony transfers and soft-tissue augmentation procedures. DAS utilizes the long head of the biceps (LHB) tendon, transferring it through a subscapularis split to the anterior glenoid margin, creating a "sling effect" while simultaneously repairing the anterior labrum with a simple

Bankart technique [

8,

9,

10]. The method offers a dynamic and static stabilizing effect and can be performed in either an inlay or onlay position, both showing promising results. Onlay positioning may offer an additional labroplasty effect. However, long-term clinical studies are lacking [

10]. While isolated Bankart repair presents a twofold greater risk of redislocation compared to

Latarjet in cases with 10%-20% glenoid bone lesions (GBL), bony transfer procedures for GBL, such as

Latarjet, of 20%-25% carry complication rates ranging from 16% to 30%. DAS may serve as an intermediate approach, avoiding the high recurrence rates of Bankart repair and the complications of Latarjet while addressing concomitant SLAP lesions [

11].

The histopathological changes in capsulabral structures in cases of traumatic injury included the inflammatory changes in tissue as well as degenerative and necrotic changes in soft tissue and bone with hemorrhages in acute stages [

12]. However, the morphological characteristics in bone and soft tissue in case of shoulder instability surgical treatment has been poorly understood. It could be suggested that the bone and soft tissue changes could be the significant factor influencing tissue remodeling and functional results after surgical treatment.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of DAS for anterior shoulder instability by analyzing clinical and histopathological characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

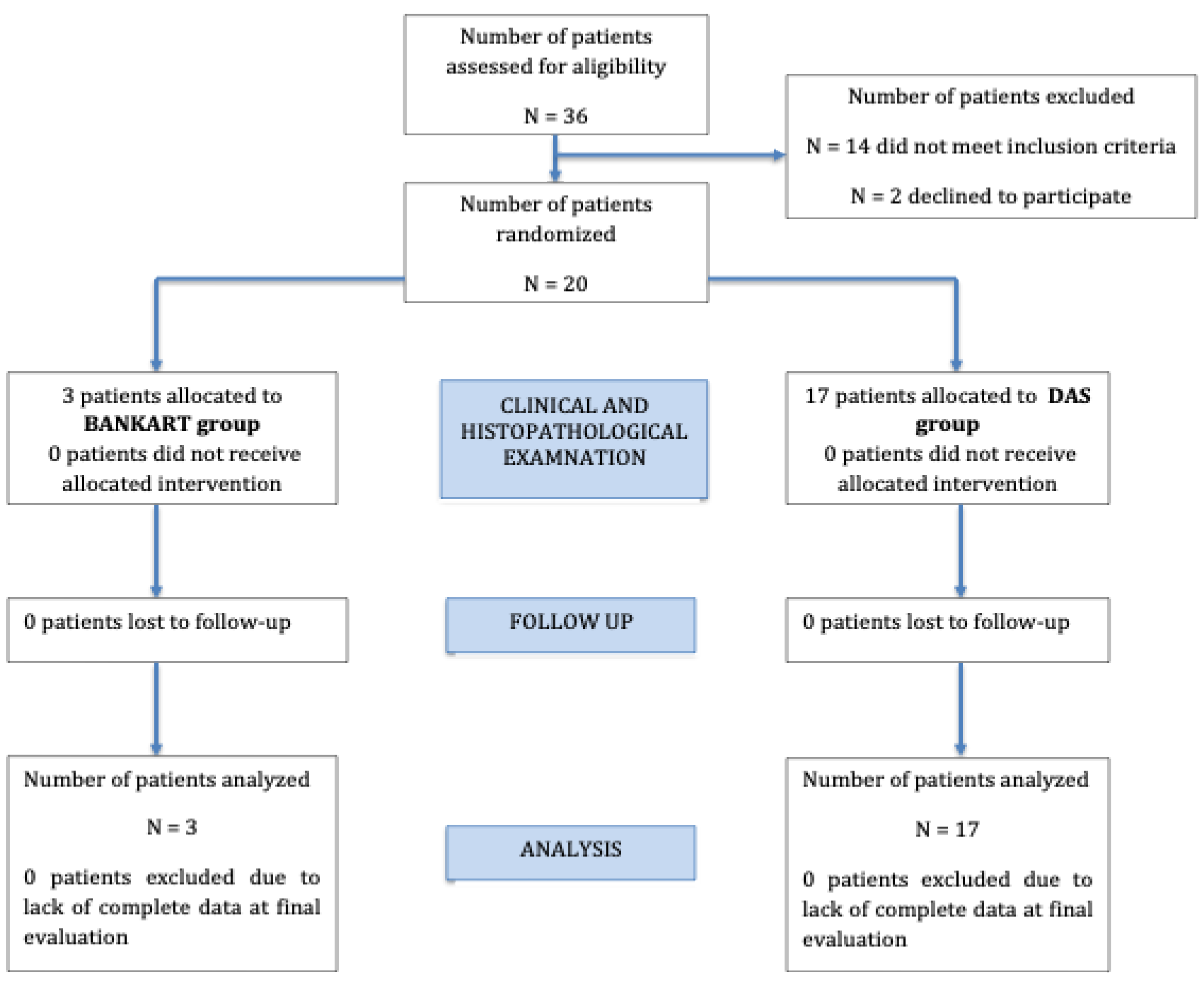

This was a single-center, prospective longitudinal study in which patients were randomly allocated into two treatment groups, operated by two different surgeons.

17 patients were included for DAS group and 3 patients were included for Bankart group.

During surgery, biopsy specimens were collected from each patient for histopathological analysis. Tissue samples were collected using a biopsy needle from the anterior glenoid bone surface, and a segment of the long head of the biceps tendon was also harvested.

All patients were followed up using standardized clinical, imaging and rehabilitation protocols.

Figure 1 Showed the flow-chat of the study.

2.2. Patient Population

A total of 20 patients with anterior shoulder instability were included in the study. All patients corresponded to the inclusions criteria and were treated between October 2023 till October 2025.

The patient population consisted of 16 males and 4 females, with a mean age of 28.5 ± 9.09 [mean ± SD] years at the time of surgery. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were comparable between the two groups.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

Age under 50 years.

History of anterior shoulder luxation or subluxation.

Ongoing anterior shoulder instability.

MRI-confirmed anterior labral lesion and Hill-Sachs lesion.

CT-confirmed glenoid bone loss involving 10-20% of the total articulating surface.

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

Age over 50 years.

Presence of other structural damage within the shoulder joint.

Multidirectional shoulder instability.

Previous surgical intervention on the affected shoulder.

Acute infection.

Blood coagulation disorders.

Systemic illnesses such as type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, or autoimmune diseases.

2.4. Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Oviedo Convention. Ethical approval was obtained from Riga Stradins University (No. 2-PEK – 4/694/2024, 29.11.2024.). The informed consent form was obtained from all participants in accordance with institutional requirements.

2.5. Clinical Evaluation, Follow-Up Schedule and Rehabilitation

Clinical assessments were conducted at 1, 3, and 6 months. During each follow-up visit, patients were evaluated using the following standardized clinical outcome measures:

Constant Shoulder Score (CSS)

American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) Score

Oxford Shoulder Instability Score (OSIS)

Visual Analog Scale (VAS)

In addition, operative time and the need for additional analgesic medication were recorded.

All patients underwent the same rehabilitation protocol.

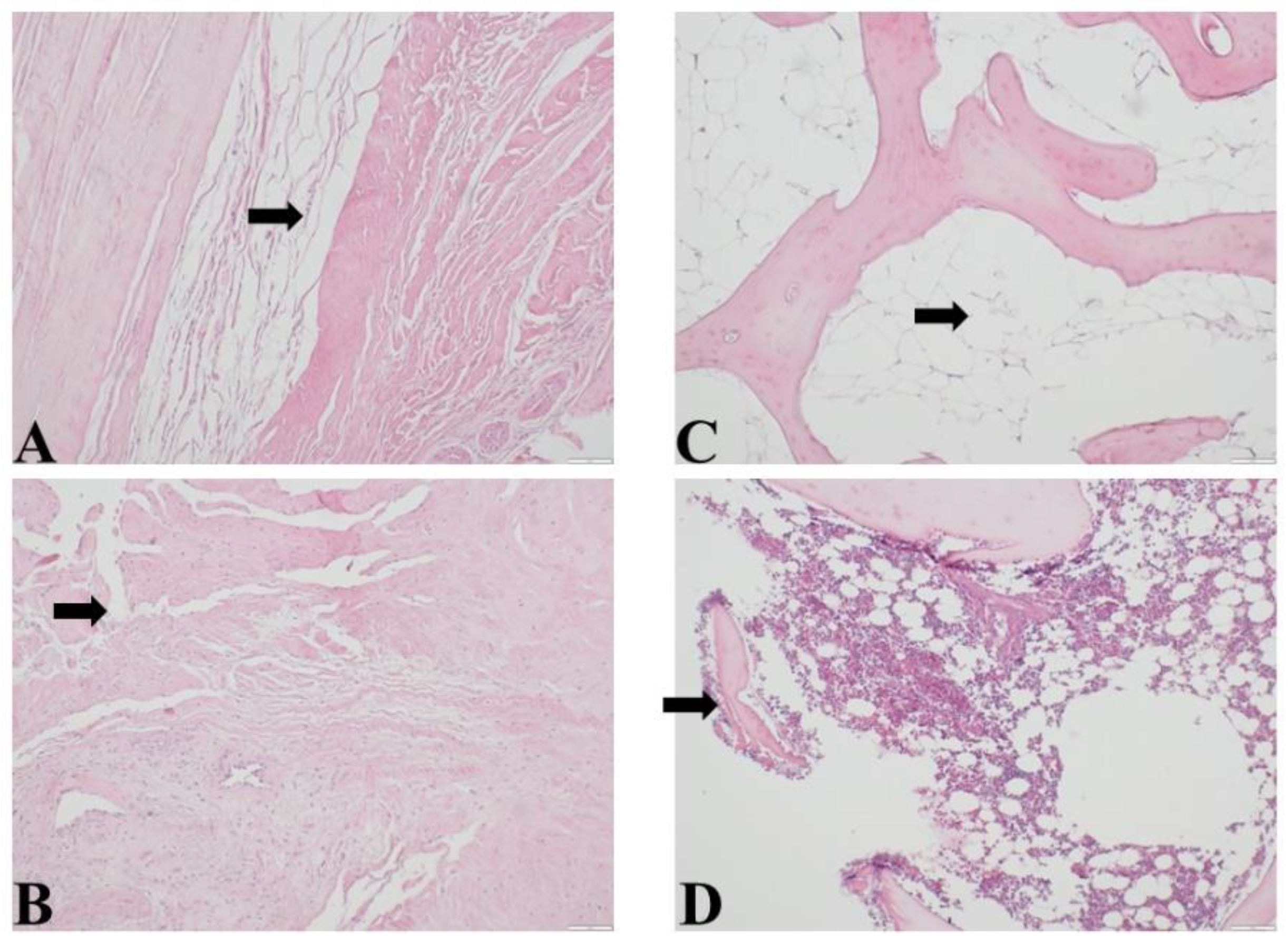

Histopathological examination

The tissue specimens from the anterior glenoid bone surface and a segment of the long head of the biceps tendon were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. The 3 μm thick sections were stained with haemotoxylin-eosin. The histopathological changes in bone and soft tissue were assessed. The number of inflammatory cell (lymphocytes, leukocytes) were assessed in ten high powered field at magnification x 400 and results were expressed as cell per mm/2. The osteonecrosis was assessed in whole bone tissue specimens, and the results were expressed as percentage of necrotic bone trabeculae. The peritrabecular fibrosis and lipomatosis were assessed in in ten high powered field at magnification x400 and results were expressed as cell per mm/2. The peritrabecular fibrosis and lipomatosis was grades as: 0-absent; 1-mild; 2-moderate, 3- prominent.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Categorical and non-parametric data were analysed using the Chi-square test and the Mann–Whitney U test, respectively. The association between surgical technique and clinical outcomes was assessed using the Fisher’s exact test. Correlations between immunohistochemical biomarker expression and clinical or histopathological variables were evaluated using the Pearson Chi-square (χ²) test. The relationship between surgical method, recurrence, and postoperative complications was analysed using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis with the log-rank test. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Graph PadPrism 12. version software was used for the data analysis.

3. Results

20 patients were enrolled in the study.

Table 1 demonstrated the clinical characteristics of the enrolled subjects. The 16 patients were males and 4 patients were females. Male/female ratio was 4/1. The median patient age was 28.5 ± 9.09 years.

5 patients had left shoulder dislocation, whereas 15 patients had right shoulder dislocation.

The time from shoulder dislocation till surgery was 30 months (range, 2-97 months).

3 patients underwent Bankart surgery, whereas 17 patients had DPS surgery. The median numbers of shoulder dislocations in patients were 4 (range, 2-12). The X-ray glenoid median defect was 15.75 ± 3.32%.

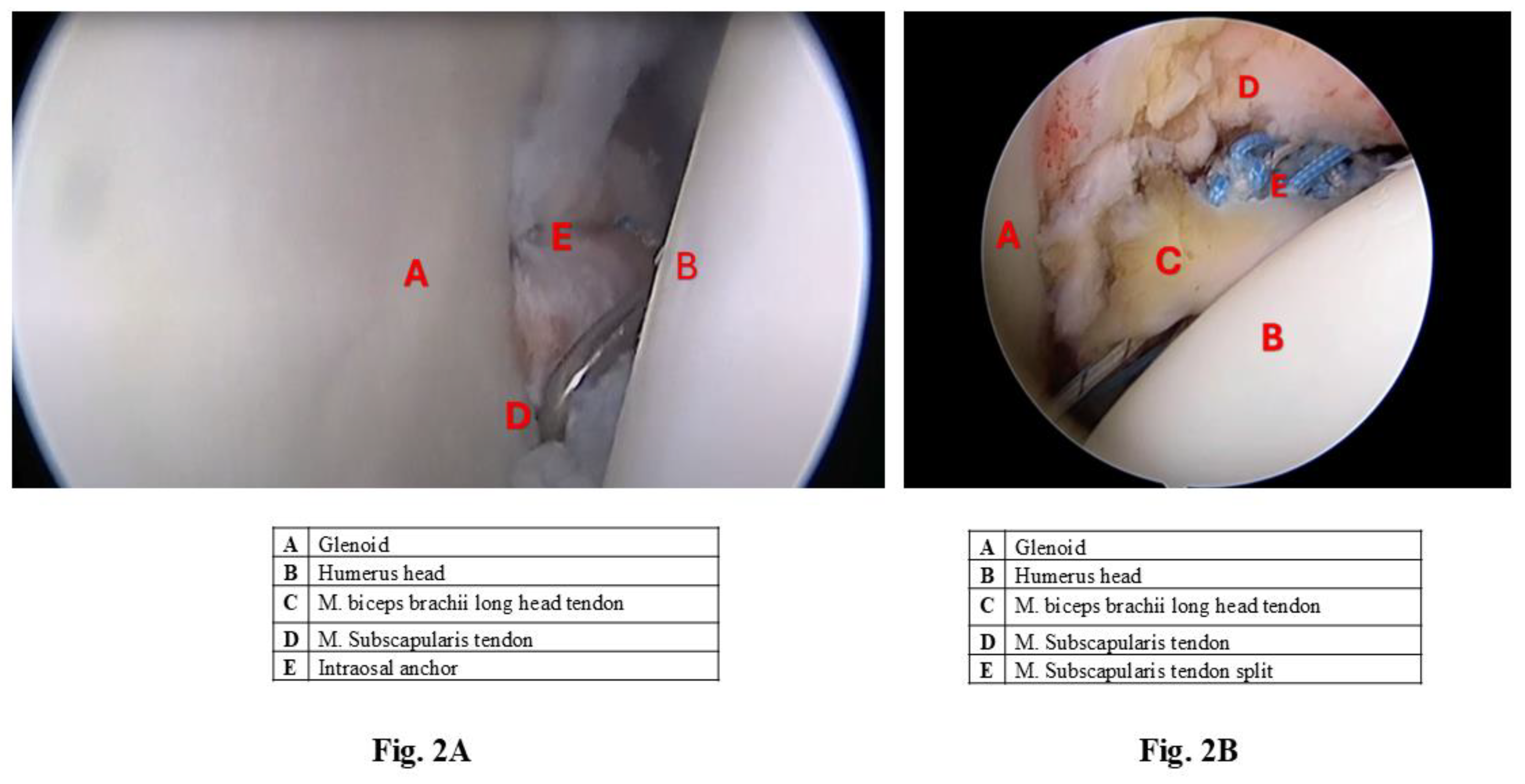

Figure 2 demonstrated representative arthroscopis microphotograph of Bankart (

Figure 2A) and Dynamic Anterior Stabilization (

Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Representative arthroscopis microphotograph of

Bankart (

Figure 2A) and Dynamic Anterior Stabilization surgery (

Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Representative arthroscopis microphotograph of

Bankart (

Figure 2A) and Dynamic Anterior Stabilization surgery (

Figure 2B).

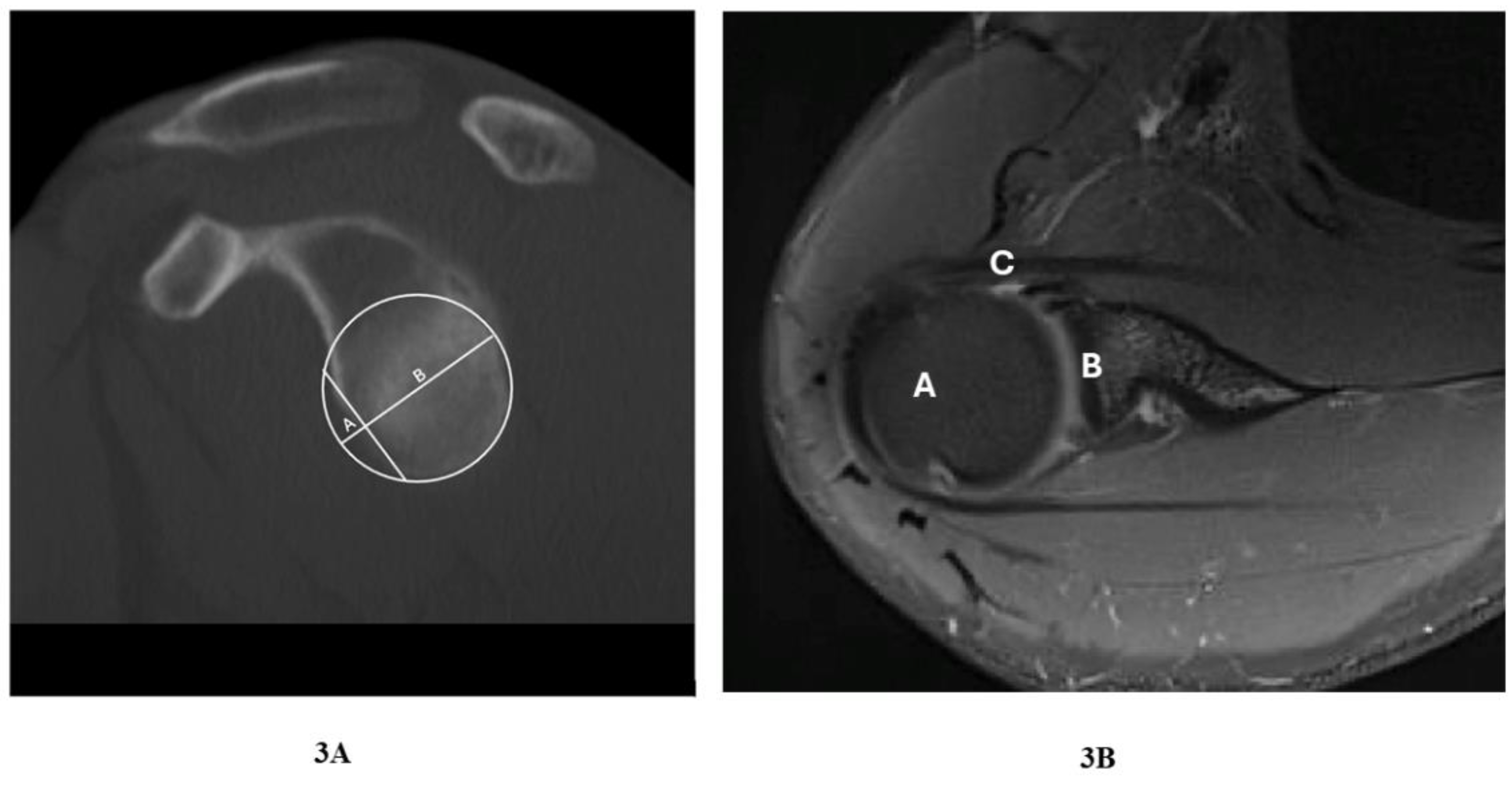

Figure 3.

Representative Shoulder CT image demonstrating glenoid defect (sagital_bone); A – anterior bone defect of glenoid; B – glenoid bone. 3B. Representative shoulder joint MRI image (pd_BLADE_fs_tra_256), A – humeral head, B – glenoid , C – labrum anterior lesion.

Figure 3.

Representative Shoulder CT image demonstrating glenoid defect (sagital_bone); A – anterior bone defect of glenoid; B – glenoid bone. 3B. Representative shoulder joint MRI image (pd_BLADE_fs_tra_256), A – humeral head, B – glenoid , C – labrum anterior lesion.

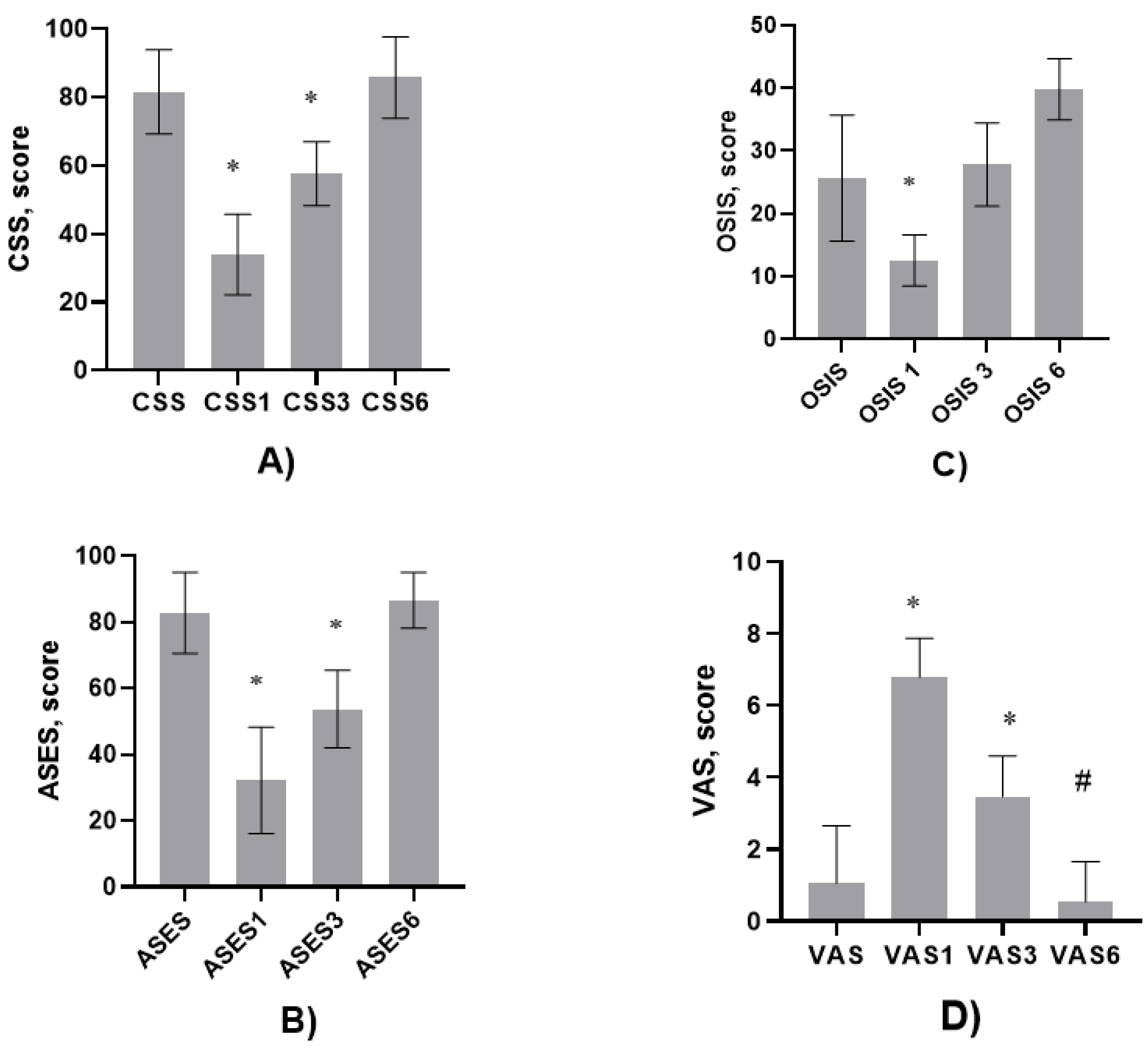

The Constant Shoulder Score (CSS), American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES), Oxford/Shoulder instability score (OSIS) and Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was assessed before the surgery and 1,3 and 6 months after the surgery.

Multivariate analysis showed the tendence of association of dislocation time to surgery with OSIS, P=0.08. The numbers of dislocation were associated with shoulder dislocation (time) / reduction in hospital (P=0.0087).

The time of surgery was associated with ASES (P=0.034). In addition, VAS was associated with CSS (P=0.03; Rho = - 0.53).

Histopathological examination of bone and soft tissue after the surgery demonstrated mild to moderate reactive fibroconnective tissue with reactive myofibroblasts, tissue oedema, hemorrhage, mild to moderate lymphocyte and leukocytes infiltration. Bone changes demonstrated fragmentation of bone trabeculae, hemorrhage, mild leukocyte infiltration. In 6 patients the focal osteonecrosis was observed. 5 patients demonstrated moderate to prominent peritrabecular lipomatosis.

Figure 4. demonstrated histopathological changes in bone and soft tissue.

In addition, VAS score was associated with the lymphocyte infiltration in bone/soft tissue (P=0.027; Rho = -0.567).

The patients were followed up for one, three and six months. The CSS, ASES, OSIS and VAS were assessed in 1, 3 and 6 months.

Obtained results showed that after one and three months after surgery

CSS was significantly decreased compared before the operation, respectively, 34.00 ± 11.79 vs 83.50 ± 12.34, P<0.0001 and 57.00 ± 9.39 vs 83.50 ± 12.34, P<0.0001,

Figure 5 A.

However, after 6 months the CSS did not differ compared to CSS values before the operation.

The similar trend was observed then

ASES was analyzed. One and three months after surgery

ASES was significantly decreased compared before the operation, respectively, 34.00 ± 11.79 vs 83.50 ± 12.34, P<0.0001 and 57.00 ± 9.39 vs 83.50 ± 12.34, P<0.0001,

Figure 5B.

However, after 6 months the ASES did not differ compared to ASES before the operation.

OSIS after one month surgery decreased compared before the surgery, 13.00 ± 4.090 vs 26.00 ± 10.04, P<0.0001. However, it did not differ after 3 months of surgery. At contrast, after 6 months of surgery,

OSIS increased compared to the values before the surgery-39.00 ± 4.84 vs 26.00 ± 10.04, P<0.0001,

Figure 5C.

VAS increased one and three months after the surgery, respectively, 6.79 ± 1.084 vs 1.05 ± 1.605, P<0.0001 and 3.46 ± 1.125 vs 1.05 ± 1.605, P<0.0001. However, the

VAS after 6 months significantly decreased compared to three, one months after and before the surgery (P<0.0001),

Figure 5D.

Obtained results showed that osteonecrosis was associated with ASES score in 6 months, P= 0.044; Rho= - 0.56.

Correlative analysis showed that patient gender and age did not associate with ASES, OSIS and VAS score.

In addition, the number of dislocations was associated with CSS in 3 months after surgery (P=0.0356; Rho= + 0.608). shoulder dislocation (time) / reduction in hospital was associated with CSS and ASES in 3 months after operation, P=0.039.

The X Ray glenoid defect was associated with ASES, P=0.025; Rho= - 0.511.

3. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge our study for the first time addressing the predictive value of histopathological and clinical characteristics after 1, 3 and 6 months of anterior shoulder instability treatment by dynamic anterior stabilization (DAS).

Our results demonstrated that the first three months postoperatively were characterized by worse functional outcomes, reflecting the expected healing and rehabilitation period, however six months after the DAS procedure, patients demonstrated non-inferior outcomes in the Constant-Murley Score (CSS) and the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score, and improved outcomes in the Oxford Shoulder Instability Score (OSIS), compared to their preoperative status

Shoulder pain, as measured by the visual analog scale (VAS), also decreased after six months, both in comparison with preoperative values and with the 1-3-month postoperative period.

Our study showed that glenoid bone preoperative osteonecrosis, glenoid defect, the time between dislocation and surgery, and the number of dislocations were significantly associated with functional outcomes after surgery. These findings highlight the importance of early recognition and timely surgical management of shoulder instability, as well as careful patient selection. In addition, a higher number of lymphocytes in soft tissues was associated with higher VAS pain scores, suggesting that local inflammation may play the role in pain persistence and outcomes. Clinicians should keep these factors in mind, as they can affect functional recovery both in the short and long term.

Previous studies showed that DAS treatment characterized by lower complications rate.

Clara de Campos Azevedo et al. [

4] reported recurrence in only one patient (6.7%), while

Philippe Collin et al. [

5] found three recurrences (13.6%), mainly in earlier cases reflecting the surgeon’s learning curve. Both studies, however, lacked a control group treated with alternative techniques by the same surgeon. Furthermore, previous studies have focused on retrospective and biomechanical analyses after surgical treatment. It has been demonstrated that DAS significantly reduced anterior glenohumeral translation compared to

Bankart repair alone in shoulders with 10–20% GBL [

13,

14]. A potential limitation was association with posterior and inferior humeral head shifts in abduction and external rotation (ABER). While the long-term effects remain unclear, posterior shifts greater than 5 mm have been linked to premature degenerative joint changes in cases with more extensive bone loss [

13]. Our results were consistent with previous findings and extent them by observation of such effect in prospective study after 1-, 3- and 6-month follow-up period.

Previous studies showed that patients age and male gender were associated with higher risk of surgery failure after primary shoulder stabilization [

13]. At contrast our study did not found association between patient age and gender. It could be suggested that young patients’ age (median age 28.5 years) could contribute to it.

Glenoid bone loss is well-known risk factor for failure of primary stabilization surgery [

14,

15,

16]. Previous studies showed that combined glenoid and humeral head defects have an additive and negative effect on glenohumeral stability [

17]. It has been shown that a threshold of 11% posterior glenoid bone loss implicated a 10 times higher surgical failure rate, while a threshold of 15% led to a 25 times higher surgical failure rate [

18]. However, our study demonstrated that following DAS surgical treatment after 6 months of operation the

CSS,

ASES,

OSIS and VAS score significantly improved. This led to the suggestion that DAS surgical treatment seems superior compared to other methods.

Osteonecrosis resulted in fibrous scar formation with impaired clinical outcomes [

16]. Our results were consistent with previous findings and extent these by demonstrating that the X-ray glenoid defect was associated with

ASES score.

The previous findings demonstrated that the changes in anterosuperior glenohumeral capsular ligament correlated with the shoulder trauma outcomes [

19,

20,

21]. Furthermore, both dynamic and static roles contributing to glenohumeral stability and mobility of ligaments [

22]. Our findings support and extent previous observations demonstrated that the extent of lymphocyte infiltration is significantly associated with VAS score contributing to the surgery outcomes.

Previous studies showed that the bone union started from 3 months postoperatively [

23], which was consistent with our findings indicated that

CSS,

ASES,

OSIS,

VAS value improved after 3 months, but more significantly after 6 months.

From a clinical and biomechanical perspective, DAS offers several advantages. It allows simultaneous treatment of SLAP lesions through LHB tenodesis and reproduces the three stabilizing mechanisms of the

Latarjet (bumper effect, ligament reinforcement, and sling effect), while preserving the coracoid process and pectoralis muscle. This reduces neurological risk and scapular dyskinesis and strengthens

Bankart repair in cases of poor-quality capsuloligamentous tissue [

8,

9]. Unlike

Latarjet,

DAS does not require screws or a full arthrotomy and is performed arthroscopically [

9]. However, it is not suitable for GBL >20% or significant

Hill-Sachs lesions unless combined with bone block or remplissage procedures [

8]. Poor LHB tendon quality, previous biceps procedures, or capsular deficiency are additional contraindications, and axillary nerve injury during subscapularis perforation remains a theoretical concern [

8].

DAS is primarily indicated for anterior instability with weakened capsular ligaments and GBL ≤20% [

8]. It is appropriate for SLAP type I–III lesions and positive apprehension tests in 90° abduction/external rotation [

5,

10]. Relative contraindications include GBL of 20-30%, instability in overhead athletes without SLAP lesions, and subscapularis injuries [

9]. Absolute contraindications include GBL >30%, prior LHB procedures, LHB rupture, and glenohumeral arthritis [

5,

9].

Compared to

Bankart repair,

DAS is more effective in cases of subcritical bone loss.

Bankart repair alone remains suitable for minor lesions (<10%) but has higher recurrence rates in GBL of 10–20%. The

Latarjet procedure addresses larger bone defects effectively but is technically complex, requires pectoralis minor release, and carries a higher risk of neurological complications.

DAS therefore offers an intermediate option, balancing efficacy with a lower complication profile [

8,

9,

10,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. In addition,

ASES score and the extent of glenoid defect has been showed as the major predictor outcomes reverse total shoulder arthroplasty [

29]. Furthermore, the ASES score has been found as a major predictor in patients with recurrent anterior shoulder instability [

30].

This study has several important strengths. First, it is prospective clinical study evaluating the DAS procedure, whereas most of the existing literature were retrospective, clinical case description or biomechanical. This prospective design allows for a more reliable assessment of functional outcomes over time.

Second, the study provides comprehensive outcome evaluation, using both clinician-based subjective and objective scores (CSS, ASES, OSIS, VAS). Study allows to evaluate not only clinical objective sides of it but allows to evaluate changes in patient everyday life.

Third, different additional factors—such as glenoid osteonecrosis, defect size, time to surgery, and number of dislocations—can change the prognostic variables. These factors can help surgeons in future patient selection for improving outcomes in clinical practice.

Finally, the associations between clinical and histopathological characteristics shed the light on the personalized treatment and follow-up.

Despite these strengths, some limitations should be addressed. Firstly, the patient number was relatively small (20 patients, with 17 undergoing DAS), which may decrease the statistical power to detect subtle differences between subgroups.

Second, the follow-up duration was limited to six months, which primarily captures short- to mid-term outcomes. Long-term data are required to determine the durability of DAS.

Finally, because DAS is a technically demanding arthroscopic procedure, results can be changed because of surgeon’s experience and learning curve. This factor should be considered when interpreting complication and recurrence rates.