Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Governing Equations of Dynamic Solids

3. Multi-Time Step Integration

3.1. Salient Multi-Time Stepping Features

3.2. Summary of Temporal Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 Summary of Algorithm for Coupling in Time from N to |

|

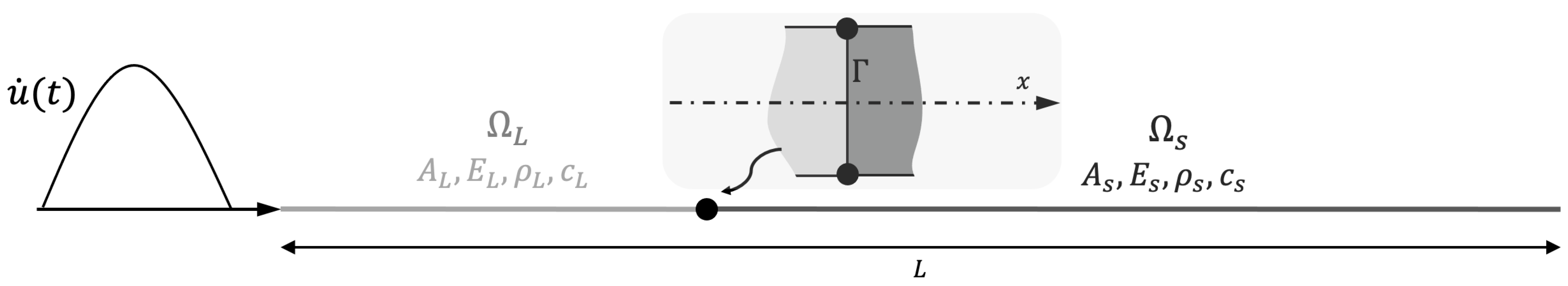

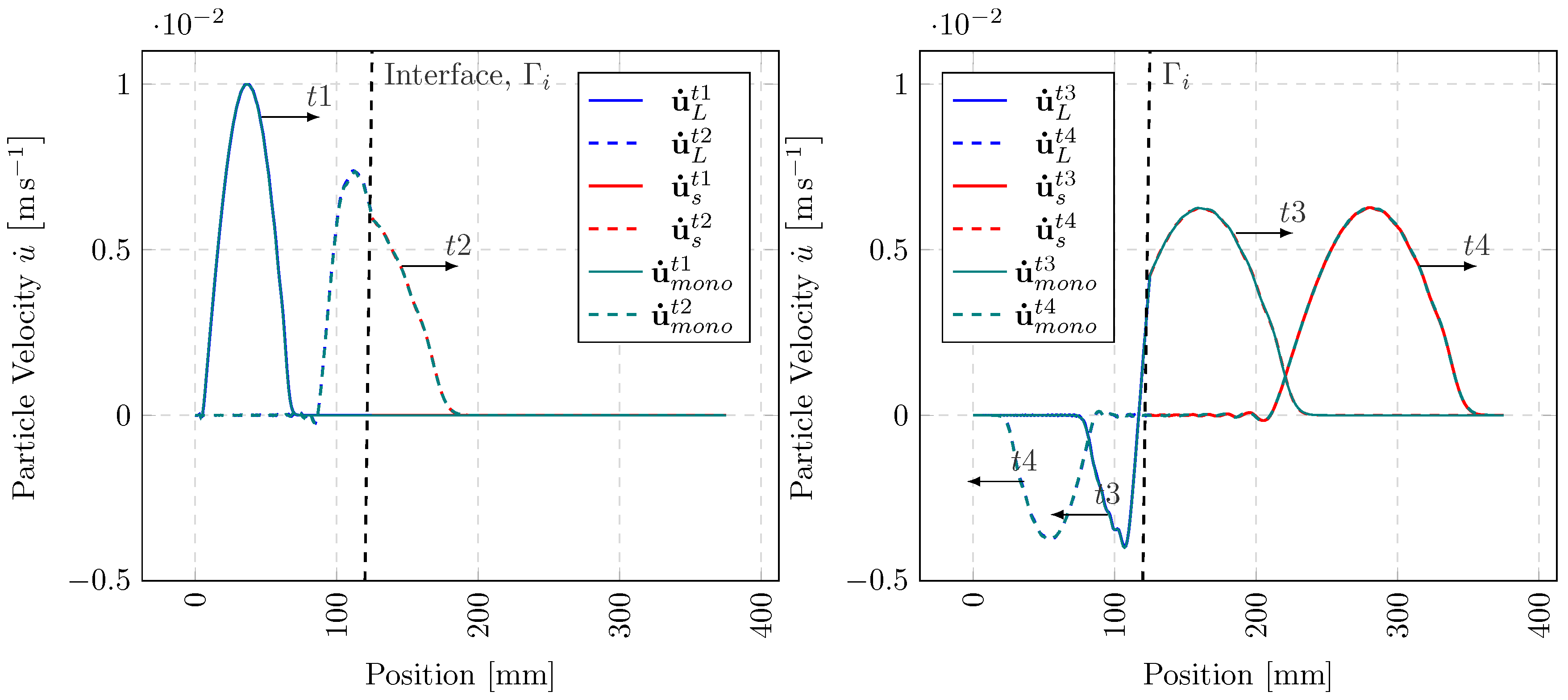

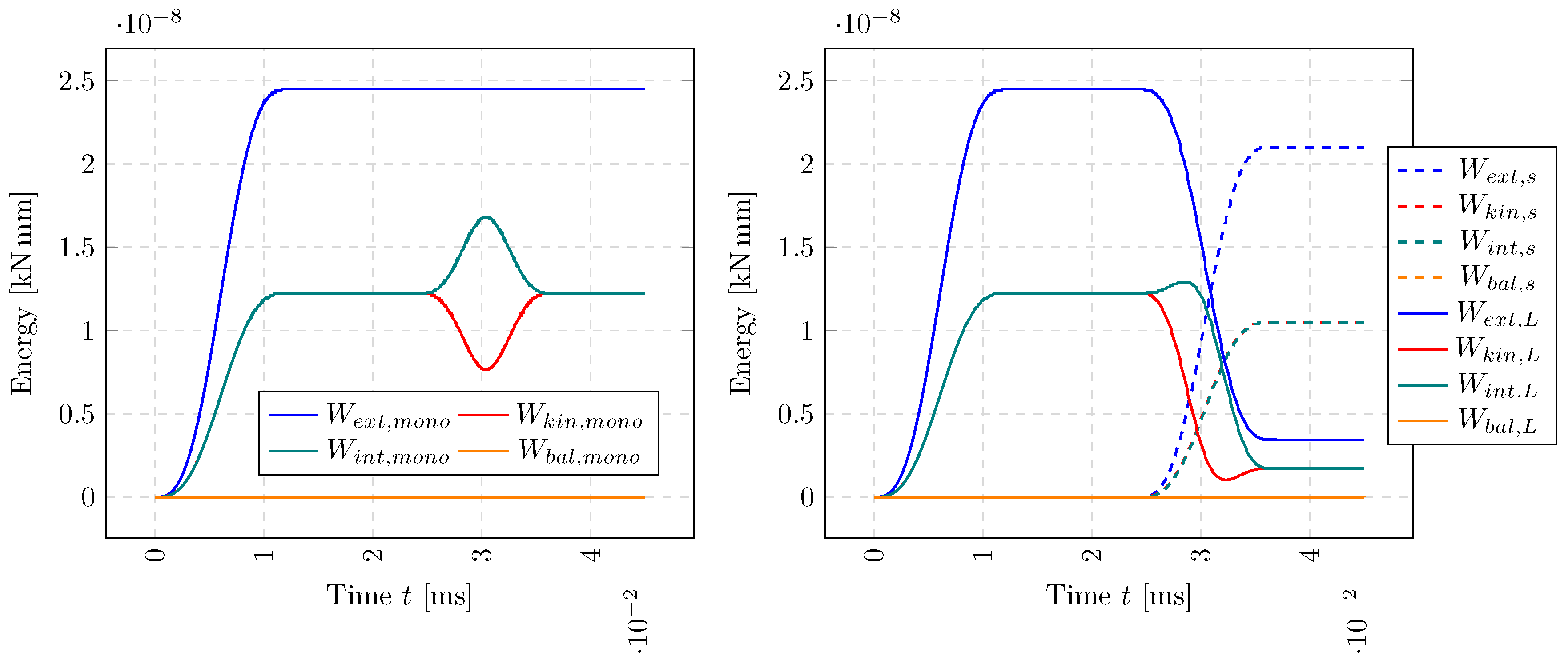

3.3. Numerical Examples in Time

4. Solving Non-Matching Meshes

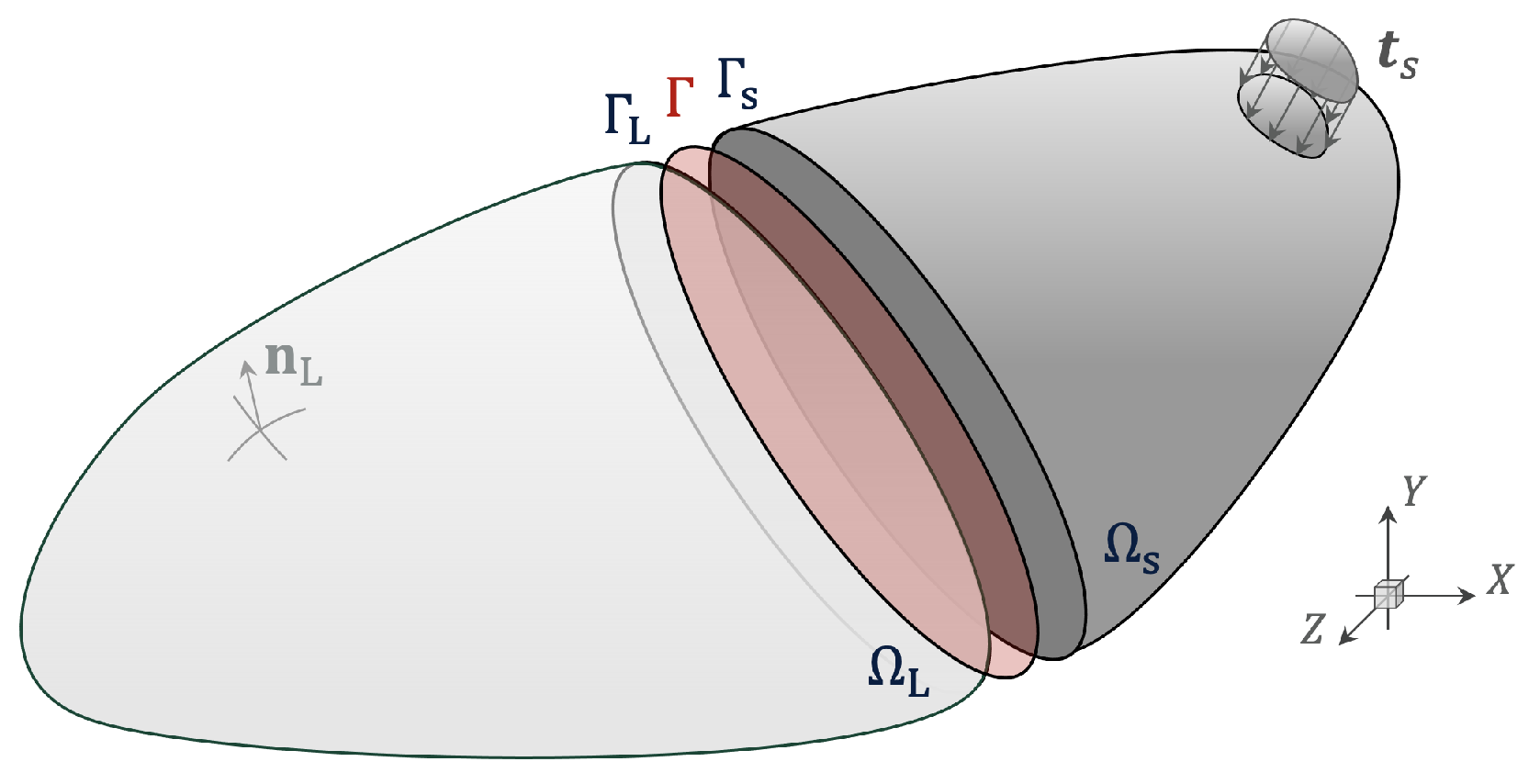

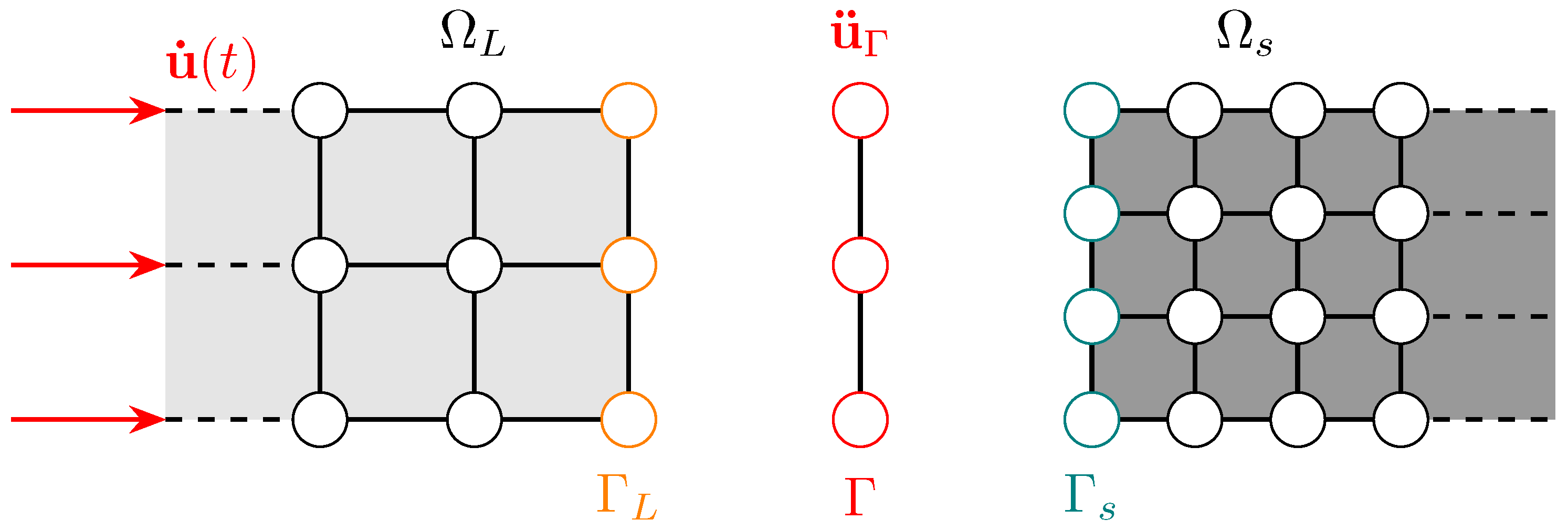

4.1. Combined Spatial and Temporal Coupling

| Algorithm 2 Summary of Non-Matching Mesh Algorithm with Multi-Time Stepping |

|

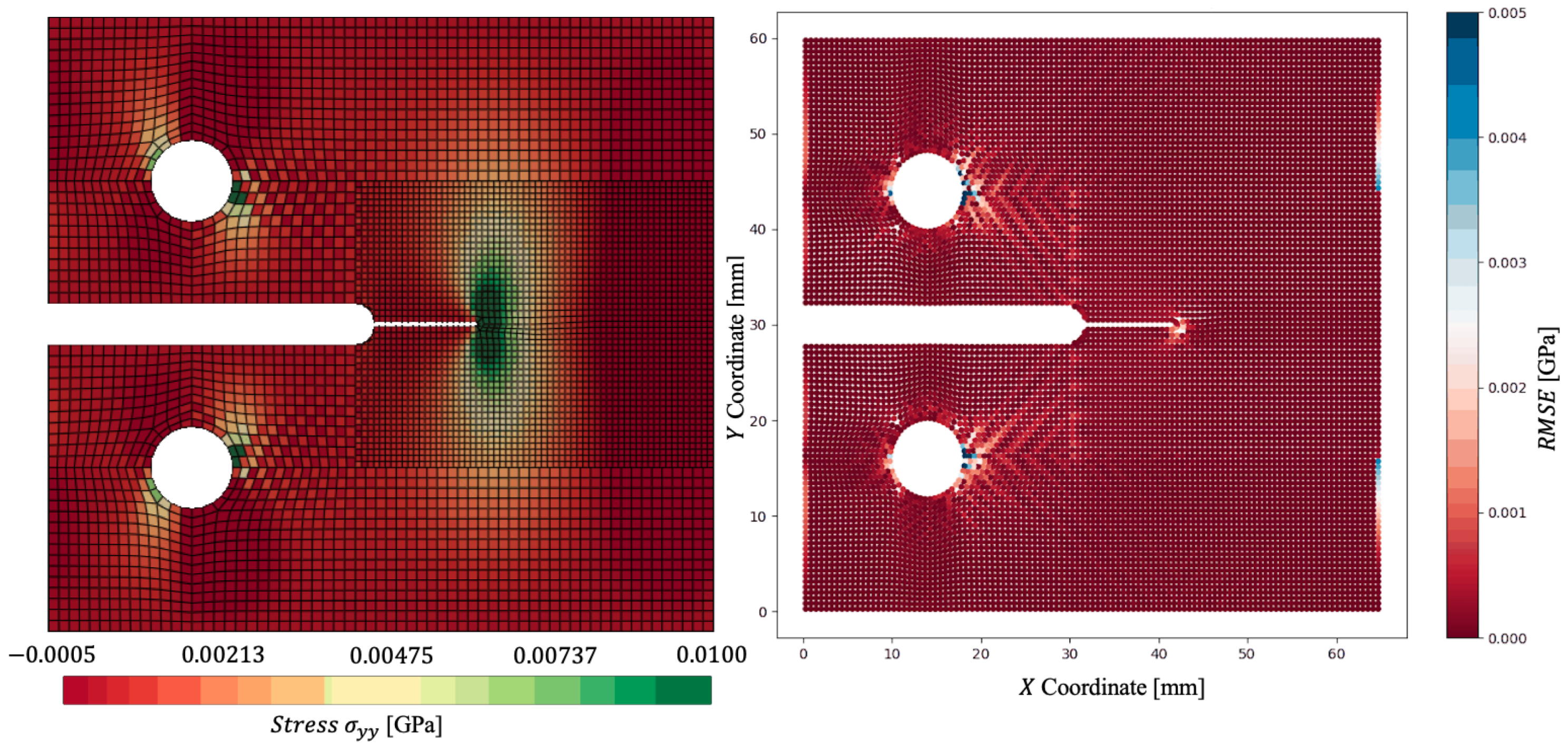

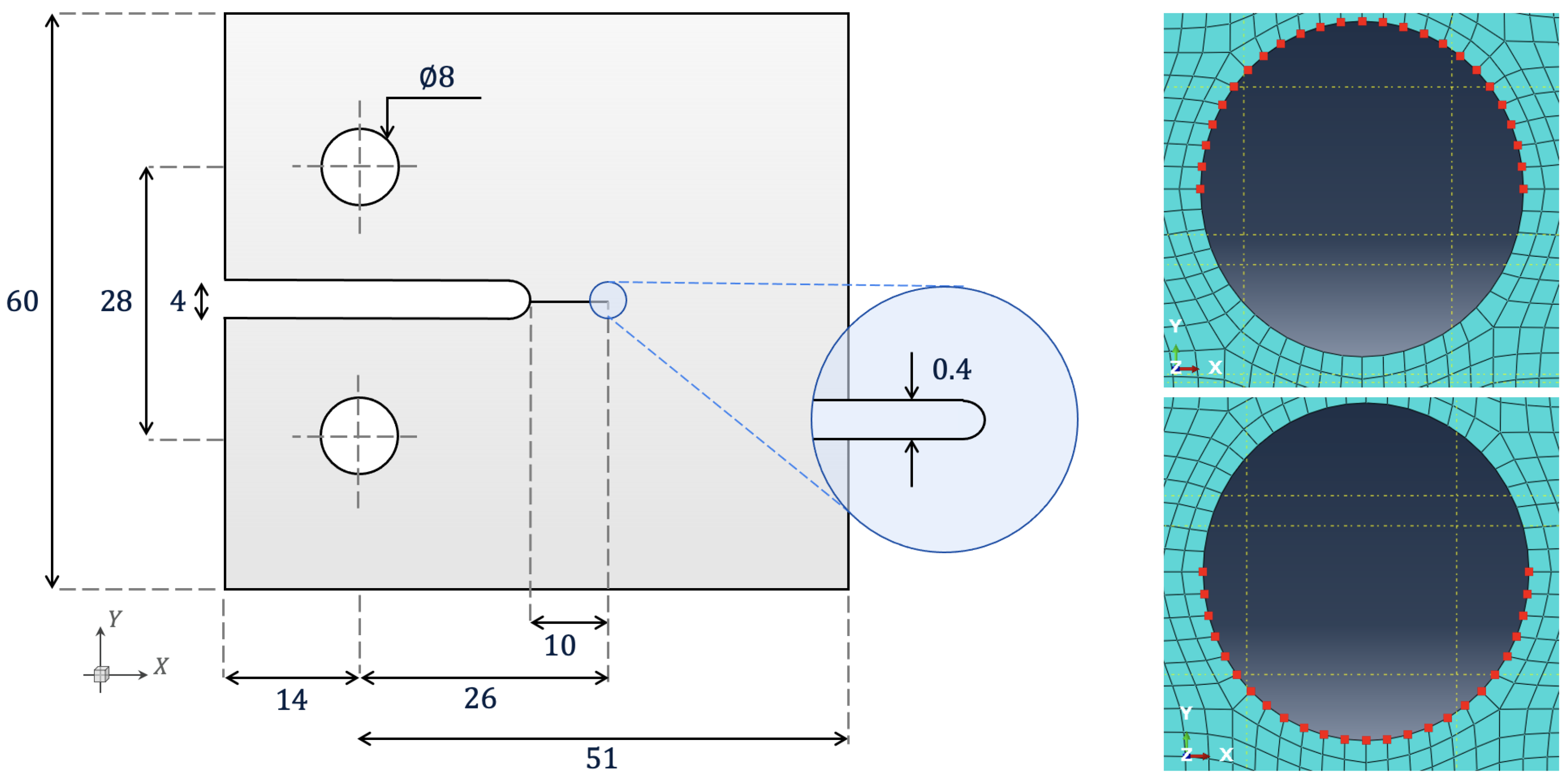

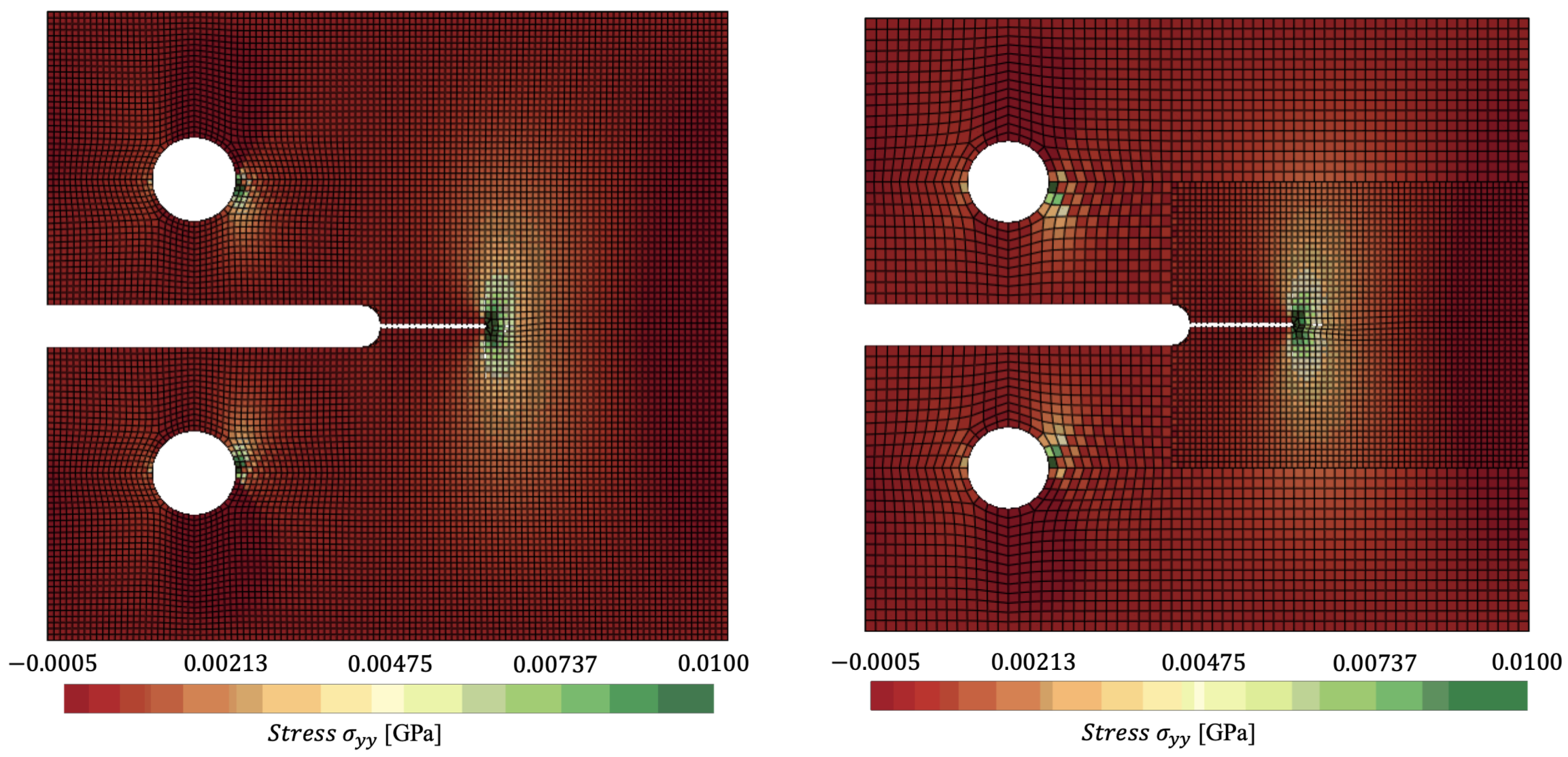

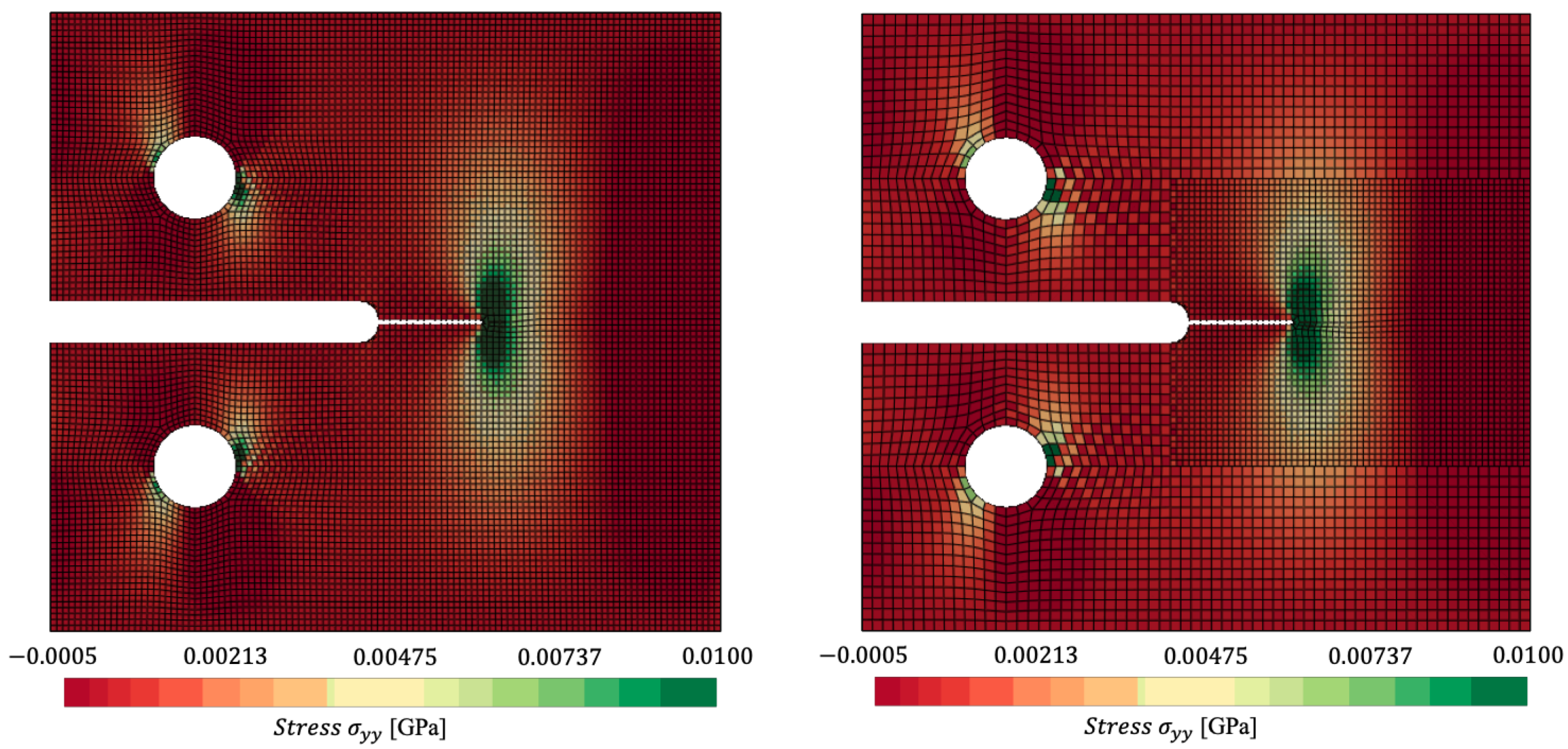

4.2. Numerical Examples in Space and Time

| Simulation | Runtime [s] | Speedup |

|---|---|---|

| Reference (monolithic) | 7428 | - |

| Spatially Coupled | 2267 | 3.27× |

| Spatially and Temporally Coupled | 572 | 12.98× |

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Courant, R., Friedrichs, K. and Lewy, H., On the partial difference equations of mathematical physics. IBM journal of Research and Development 1967, 11(2), 215–234. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.J. and Liu, W.K., Implicit-explicit finite elements in transient analysis: Implementation and numerical examples. Journal of Applied Mechanics, Transactions ASME 1978, 45(2), 375–378. [CrossRef]

- Neal, M.O. and Belytschko, T., Explicit-explicit subcycling with non-integer time step ratios for structural dynamic systems. Computers & Structures 1989, 31(6), 871–880. [CrossRef]

- Daniel, W.J.T., Analysis and implementation of a new constant acceleration subcycling algorithm. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 1997, 40(15), 2841–2855.

- Daniel, W.J.T., A partial velocity approach to subcycling structural dynamics. Computer methods in applied mechanics and engineering 2003, 192(3-4), 375–394. [CrossRef]

- Lew, A., Marsden, J.E., Ortiz, M. and West, M., Variational time integrators. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2004, 60(1), 153–212. [CrossRef]

- Combescure, A. and Gravouil, A., A numerical scheme to couple subdomains with different time-steps for predominantly linear transient analysis. Computer methods in applied mechanics and engineering 2002, 191(11-12), 1129–1157. [CrossRef]

- Gravouil, A., Combescure, A. and Brun, M., Heterogeneous asynchronous time integrators for computational structural dynamics. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2015, 102(3-4), 202–232. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.S., Kolman, R., González, J.A. and Park, K.C., Explicit multistep time integration for discontinuous elastic stress wave propagation in heterogeneous solids. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2019, 118(5), 276–302. [CrossRef]

- Dvořák, R., Kolman, R., Mračko, M., Kopačka, J., Fíla, T., Jiroušek, O., Falta, J., Neuhäuserová, M., Rada, V., Adámek, V. and González, J.A., Energy-conserving interface dynamics with asynchronous direct time integration employing arbitrary time steps. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2023, 413, 116110. [CrossRef]

- de Boer, A., van Zuijlen, A.H. and Bijl, H., Review of coupling methods for non-matching meshes. Computer methods in applied mechanics and engineering 2007, 196(8), 1515–1525. [CrossRef]

- Hansbo, A. and Hansbo, P., An unfitted finite element method, based on Nitsche’s method, for elliptic interface problems. Computer methods in applied mechanics and engineering 2002, 191(47-48), 5537–5552. [CrossRef]

- Hansbo, A. and Hansbo, P., Nitsche’s method for coupling non-matching meshes in fluid-structure vibration problems. Computational Mechanics 2002, 32, 134–139. [CrossRef]

- Wriggers, P. and Zavarise, G., A formulation for frictionless contact problems using a weak form introduced by Nitsche. Computational Mechanics 2017, 41, 407–420. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.D., Laursen, T.A. and Puso, M.A., A Nitsche embedded mesh method. Computational Mechanics 2010, 49, 243–257. [CrossRef]

- Puso, M.A. and Laursen, T.A., A mortar segment-to-segment contact method for large deformation solid mechanics. Computer methods in applied mechanics and engineering 2004, 193(6-8), 601–629. [CrossRef]

- Faucher, V. and Combescure, A., A time and space mortar method for coupling linear modal subdomains and non-linear subdomains in explicit structural dynamics. Computer methods in applied mechanics and engineering 2003, 192(5-6), 509–533. [CrossRef]

- Steinbrecher, I., Mayr, M., Grill, M.J., Kremheller, J., Meier, C. and Popp, A., A mortar-type finite element approach for embedding 1D beams into 3D solid volumes. Computational Mechanics 2020, 66, 1377–1398. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M., Zhang, B., Chen, T., Peng, C. and Fang, H., A three-field dual mortar method for elastic problems with nonconforming mesh. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2020, 362, 112870. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P., Teschemacher, T., Bucher, P. and Wüchner, R., Non-conforming FEM-FEM coupling approaches and their application to dynamic structural analysis. Engineering Structures 2021, 241, 112342. [CrossRef]

- Singer, V., Teschemacher, T., Larese, A., Wüchner, R. and Bletzinger, K.U., Lagrange multiplier imposition of non-conforming essential boundary conditions in implicit material point method. Computational Mechanics 2024, 73(6), 1311–1333. [CrossRef]

- Puso, M.A. and Laursen, T.A., A simple algorithm for localized construction of non-matching structural interfaces. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2002, 53(9), 2117–2142. [CrossRef]

- Herry, B., Di Valentin, L. and Combescure, A., An approach to the connection between subdomains with non-matching meshes for transient mechanical analysis. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2002, 55(8), 973–1003. [CrossRef]

- Subber, W. and Matouš, K., Asynchronous space–time algorithm based on a domain decomposition method for structural dynamics problems on non-matching meshes Computational Mechanics 2016, 57, 211–235. [CrossRef]

- González, J.A., Kolman, R., Cho, S.S., Felippa, C.A. and Park, K.C., Inverse mass matrix via the method of localized Lagrange multipliers. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2018, 113(2), 277–295. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, G.E., Song, Y.U., Youn, S.K. and Park, K.C., A new approach for nonmatching interface construction by the method of localized Lagrange multipliers. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2020, 361, 112728. [CrossRef]

- González, J.A. and Park, K.C., Three-field partitioned analysis of fluid–structure interaction problems with a consistent interface model. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2023, 414, 116134. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.S., Jun, S., Im, S. and Kim, H.G., An improved interface element with variable nodes for non-matching finite element meshes. Computer methods in applied mechanics and engineering 2005, 194(27-29), 3022–3046. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.G., Development of three-dimensional interface elements for coupling of non-matching hexahedral meshes. Computer methods in applied mechanics and engineering 2005, 197(45-48), 3870–3882. [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt Jr, L.A., Manzoli, O.L., Prazeres, P.G., Rodrigues, E.A. and Bittencourt, T.N., A coupling technique for non-matching finite element meshes. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2015, 290, 19–44. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, E.A., Manzoli, O.L., Bitencourt Jr, L.A., Bittencourt, T.N. and Sánchez, M., An adaptive concurrent multiscale model for concrete based on coupling finite elements. Computer methods in applied mechanics and engineering 2018, 328, 26–46. [CrossRef]

- Dunne, F., and Petrinic, N., Introduction to computational plasticity, OUP Oxford, 2005.

- de Souza Neto, E.A., Peric, D. and Owen, D.R., Computational methods for plasticity: theory and applications, John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

- Belytschko, T., Liu, W.K., Moran, B. and Elkhodary, K., Nonlinear finite elements for continua and structures, John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

- Chan, K.F., Bombace, N., Sap, D., Wason, D., Falco, S. and Petrinic, N., A Multi-Time Stepping Algorithm for the Modelling of Heterogeneous Structures With Explicit Time Integration. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2025, 126(1), e7638. [CrossRef]

- Biotteau, E., Gravouil, A., Lubrecht, A.A. and Combescure, A., Multigrid solver with automatic mesh refinement for transient elastoplastic dynamic problems. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2010, 84(8), 947–971. [CrossRef]

- Dvořák, R., Kolman, R. and González, J.A., On the automatic construction of interface coupling operators for non-matching meshes by optimization methods. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2024, 432, 117336. [CrossRef]

- Pinho, S.T., Robinson, P. and Iannucci, L., Fracture toughness of the tensile and compressive fibre failure modes in laminated composites Composites Science and Technology 2006, 66(13), 2069–2079. [CrossRef]

- Sommer, D.E., Thomson, D., Hoffmann, J. and Petrinic, N., Numerical modelling of quasi-static and dynamic compact tension tests for obtaining the translaminar fracture toughness of CFRP. Composites Science and Technology 2023, 237, 109997. [CrossRef]

- Triclot, J., Corre, T., Gravouil, A. and Lazarus, V., Key role of boundary conditions for the 2D modeling of crack propagation in linear elastic Compact Tension tests. Engineering Fracture Mechanics 2023, 277, 109012. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, I., Bilinear-Inverse-Mapper: Analytical Solution and Algorithm for Inverse Mapping of Bilinear Interpolation of Quadrilaterals. 2024, Available at SSRN 4790071.

- Falco, S., Fogell, N., Iannucci, L., Petrinic, N. and Eakins, D., A method for the generation of 3D representative models of granular based materials. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering 2017, 112(4), 338–359. [CrossRef]

- Wason, D., A multi-scale approach to the development of high-rate-based microstructure-aware constitutive models for magnesium alloys. Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford.

- Falco, S., Fogell, N., Iannucci, L., Petrinic, N. and Eakins, D., Raster approach to modelling the failure of arbitrarily inclined interfaces with structured meshes. Computational Mechanics 2024, 74, 805-–818. [CrossRef]

- Bombace, N., Dynamic adaptive concurrent multi-scale simulation of wave propagation in 3D media. Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).