Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Labeling of transferrin with Os(VI)-based electrochemical tag

2.3.2. Immunoextraction using anti-Tf magnetic beads

2.3.3. Electrochemical sensing

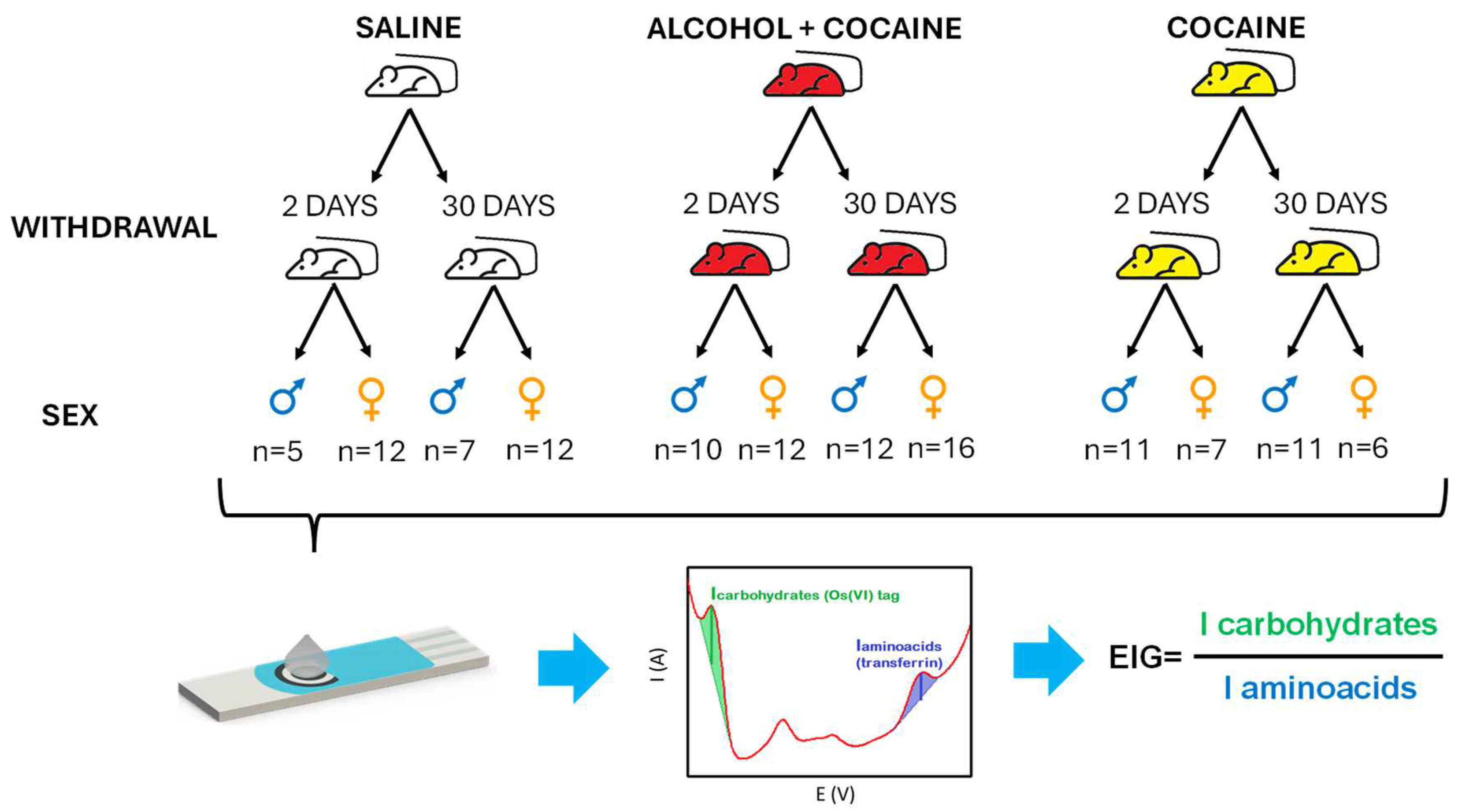

2.3.4. Animals, experimental design, and plasma preparation

Animals

Surgical Procedures

Self-Administration Protocol

Sample Collection and Analysis

2.3.5. Statistical studies

2.3.6. Clinical sensitivity and specificity

3. Results and discussion

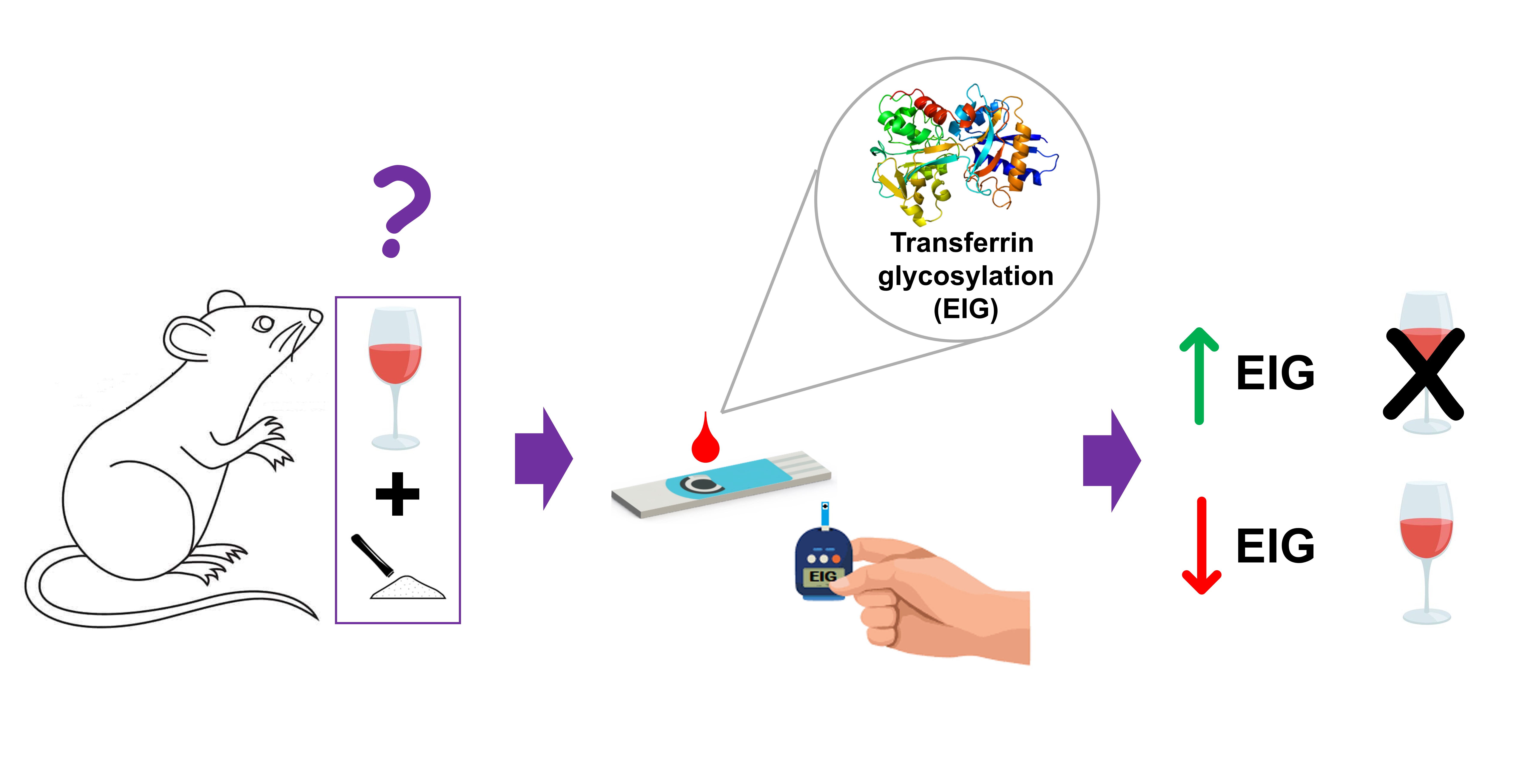

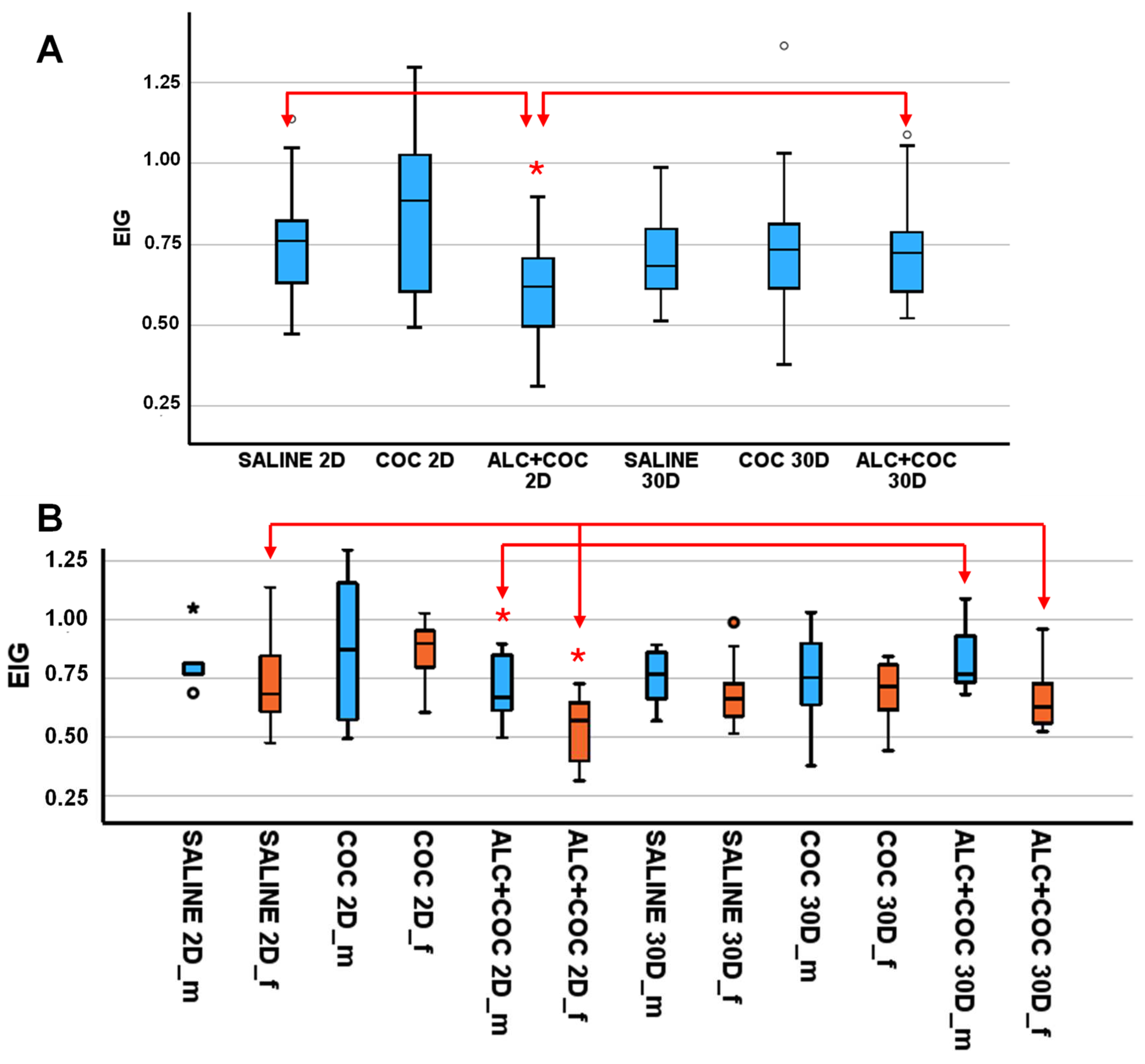

3.1. EIG level in rat plasma from polydrug-consuming rats.

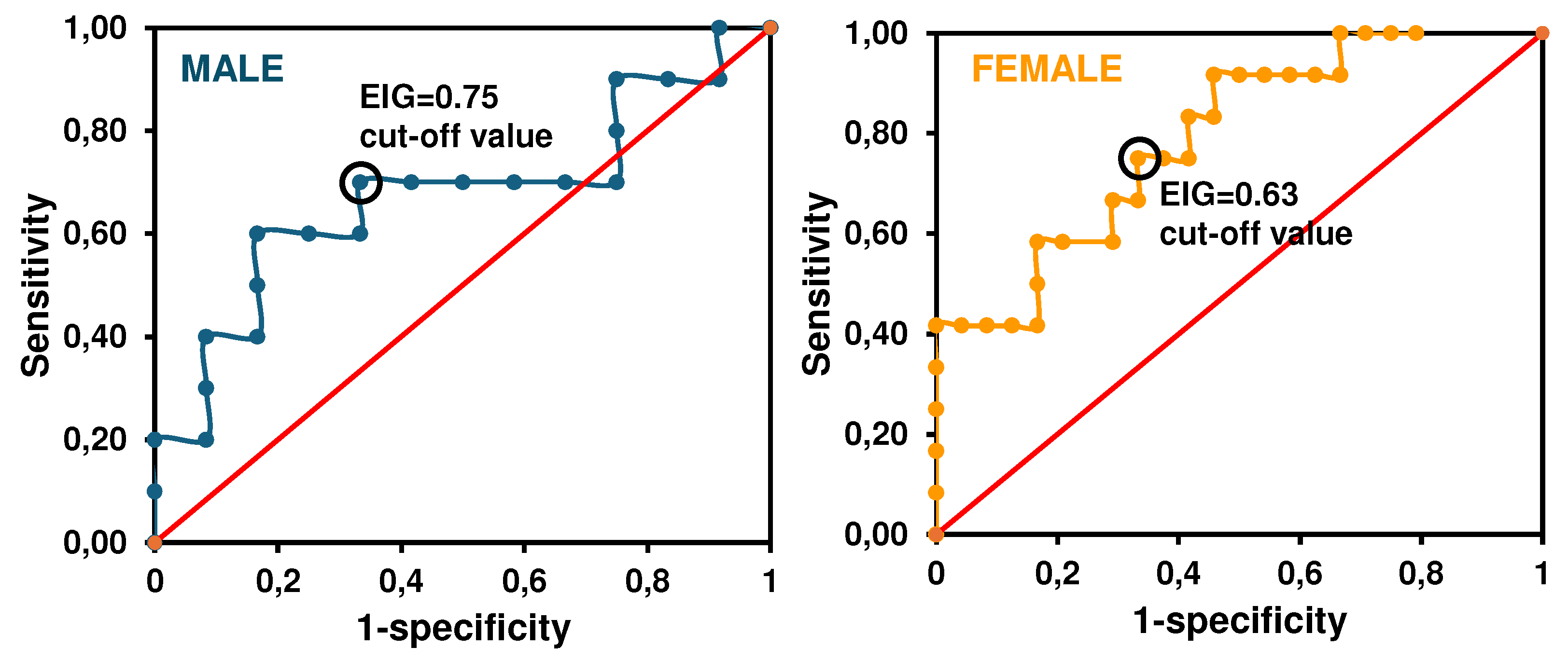

3.2. Preclinical validation of the sensor

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

References

- Liu, Y.; Williamson, V.G.; Setlow, B.; Cottler, L.B.; Knackstedt, L.A. The importance of considering polysubstance use: lessons from cocaine research. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 192, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, O. Biomarkers in alcoholism. Clin. Chim. Acta 2007, 377, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannuksela, M.L.; Liisanantti, M.K.; Nissinen, A.E.; Savolainen, M.J. Biochemical markers of alcoholism. cclm 2007, 45, 953–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Hidalgo, G.; Sierra, T.; Dortez, S.; Marcos, A.; Ambrosio, E.; Crevillen, A.G.; Escarpa, A. Transferrin analysis in wistar rats plasma: Towards an electrochemical point-of-care approach for the screening of alcohol abuse. Microchem. J. 2022, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotti, F.; Sorio, D.; Bertaso, A.; Tagliaro, F. Analytical and diagnostic aspects of carbohydrate deficient transferrin (CDT): A critical review over years 2007–2017. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 147, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caslavska, J.; Thormann, W. Monitoring of alcohol markers by capillary electrophoresis. J. Sep. Sci. 2012, 36, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanghe, J.R.; Helander, A.; Wielders, J.P.; Pekelharing, J.M.; Roth, H.J.; Schellenberg, F.; Born, C.; Yagmur, E.; Gentzer, W.; Althaus, H. Development and Multicenter Evaluation of the N Latex CDT Direct Immunonephelometric Assay for Serum Carbohydrate-Deficient Transferrin. Clin. Chem. 2007, 53, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.; Kang, M.S.; Raja, I.S.; Joung, Y.K.; Han, D.-W. Advancements in nanobiosensor technologies for in-vitro diagnostics to point of care testing. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vashist, S.K.; Luppa, P.B.; Yeo, L.Y.; Ozcan, A.; Luong, J.H.T. Emerging Technologies for Next-Generation Point-of-Care Testing. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 692–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Rodríguez, J.F.; Rojas, D.; Escarpa, A. Electrochemical Sensing Directions for Next-Generation Healthcare: Trends, Challenges, and Frontiers. Anal. Chem. 2020, 93, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Liu, C.C. Recent Advances on Electrochemical Biosensing Strategies toward Universal Point-of-Care Systems. Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 12355–12368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paimard, G.; Ghasali, E.; Baeza, M. Screen-Printed Electrodes: Fabrication, Modification, and Biosensing Applications. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, T.; Crevillen, A.G.; Escarpa, A. Electrochemical sensor for the assessment of carbohydrate deficient transferrin: Application to diagnosis of congenital disorders of glycosilation. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 179, 113098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trefulka, M.; Paleček, E. Direct chemical modification and voltammetric detection of glycans in glycoproteins. Electrochem. Commun. 2014, 48, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trefulka, M.; Černocká, H.; Staroňová, T.; Ostatná, V. Voltammetric analysis of glycoproteins containing sialylated and neutral glycans at pyrolytic graphite electrode. Bioelectrochemistry 2024, 163, 108851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, A.; Moreno, M.; Orihuel, J.; Ucha, M.; de Paz, A.M.; Higuera-Matas, A.; Capellán, R.; Crego, A.L.; Martínez-Larrañaga, M.-R.; Ambrosio, E.; et al. The effects of combined intravenous cocaine and ethanol self-administration on the behavioral and amino acid profile of young adult rats. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0227044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conigrave, K.M.; Degenhardt, L.J.; Whitfield, J.B.; Saunders, J.B.; Helander, A.; Tabakoff, B. ; on behalf of the WHO/ISBRA Study Group CDT, GGT, and AST As Markers of Alcohol Use: The WHO/ISBRA Collaborative Project. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2002, 26, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahm, F.S. Nonparametric statistical tests for the continuous data: the basic concept and the practical use. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2016, 69, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waszkiewicz, N.; Szajda, S.D.; Zalewska, A.; Szulc, A.; Kępka, A.; Minarowska, A.; Wojewódzka-Żelezniakowicz, M.; Konarzewska, B.; Chojnowska, S.; Ładny, J.R.; et al. Alcohol abuse and glycoconjugate metabolism. Folia Histochem. et Cytobiol. 2012, 50, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersche, K.D.; Acosta-Cabronero, J.; Jones, P.S.; Ziauddeen, H.; van Swelm, R.P.L.; Laarakkers, C.M.M.; Raha-Chowdhury, R.; Williams, G.B. Disrupted iron regulation in the brain and periphery in cocaine addiction. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1040–e1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trbojević-Akmačić, I.; Vučković, F.; Pribić, T.; Vilaj, M.; Černigoj, U.; Vidič, J.; Šimunović, J.; Kępka, A.; Kolčić, I.; Klarić, L.; et al. Comparative analysis of transferrin and IgG N-glycosylation in two human populations. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargiulo, T. Understanding the health impact of alcohol dependence. Am. J. Heal. Pharm. 2007, 64 (Suppl. S3), S5–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).