Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

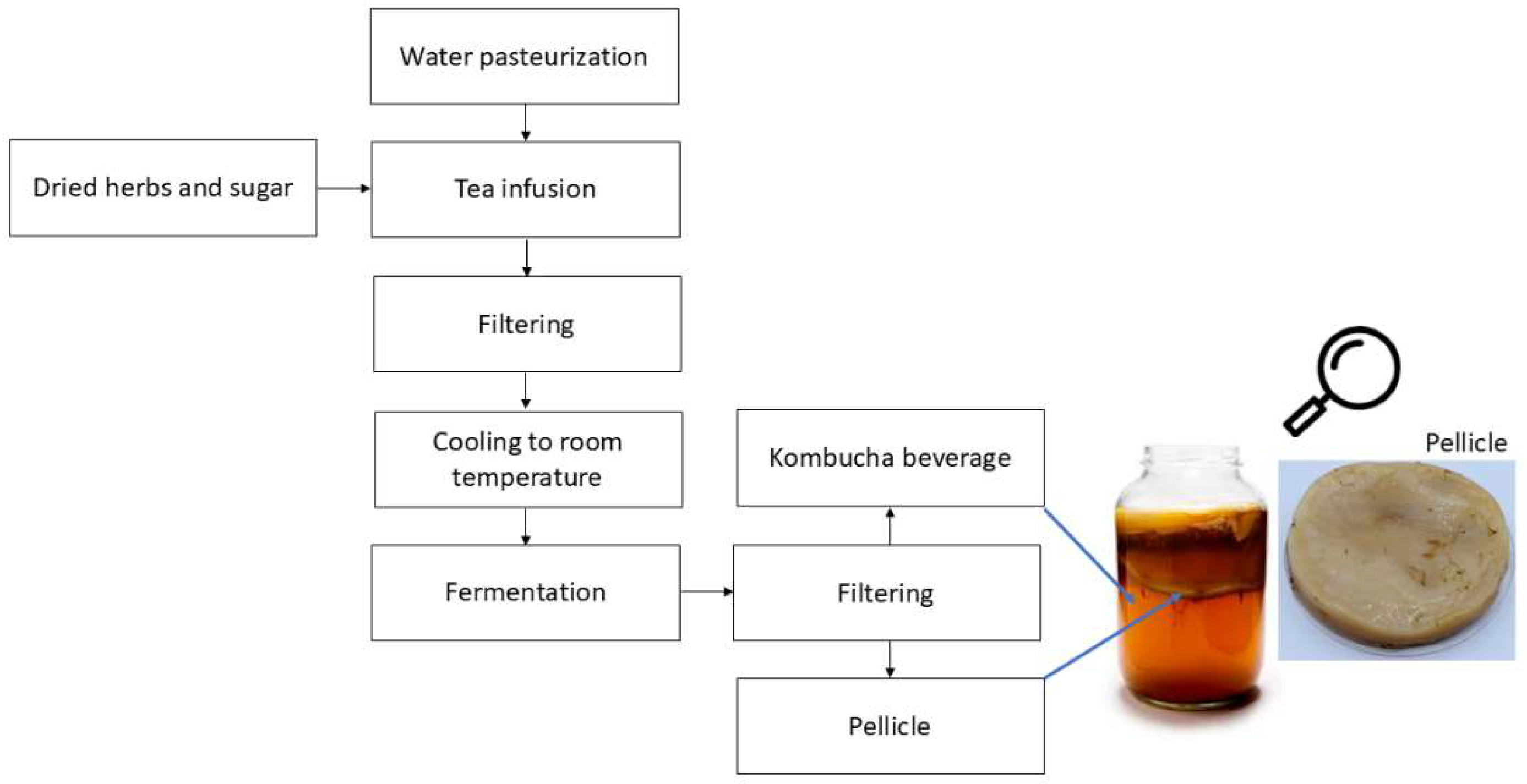

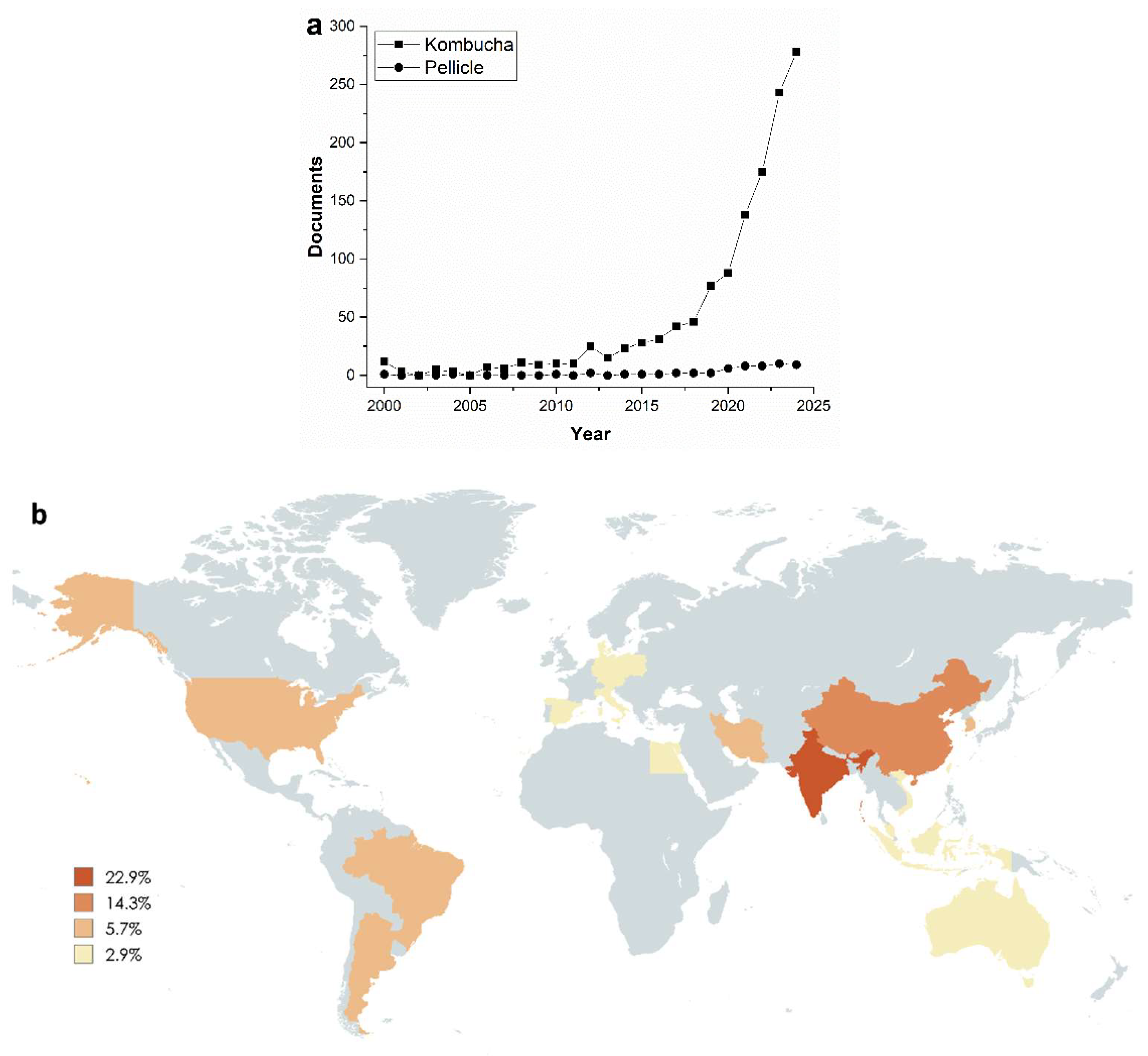

2. Research about kombucha bacterial cellulose

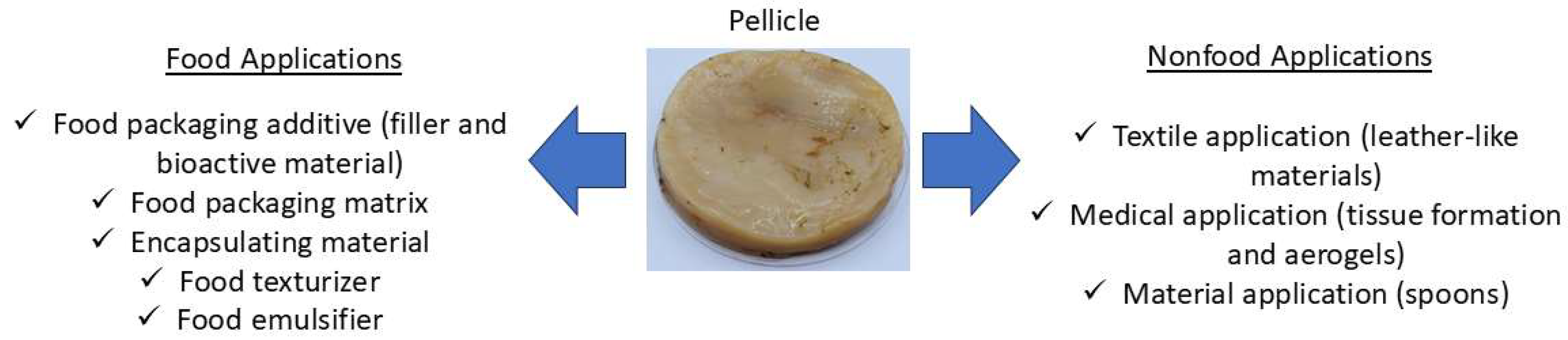

3. Application of kombucha bacterial cellulose

3.1. Food applications

3.2. Other material applications

4. Future trends

4.1. Food and pharmaceutical applications

4.2. Animal feed

4.3. Nonfood applications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AgNPs | Silver nanoparticles |

| AuNPs | Gold nanoparticles |

| CMC | Carboxymethyl cellulose |

| EM | Elastic modulus |

| PLA | Polylactic acid |

| PU | Polyurethane |

| TS | Tensile strength |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| WCA | Water contact angle |

| WVP | Water vapor permeability |

| WVTR | Water vapor transmission rate |

References

- Cavicchia, L.O.A.; Almeida, M.E.F. de Health Benefits of Kombucha: Drink and Its Biocellulose Production. Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolomedi, B.M.; Paglarini, C.S.; Brod, F.C.A. Bioactive Compounds in Kombucha: A Review of Substrate Effect and Fermentation Conditions. Food Chem 2022, 385, 132719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Huang, S.-Y.; Xiong, R.-G.; Wu, S.-X.; Yang, Z.-J.; Zhou, D.-D.; Saimaiti, A.; Zhao, C.-N.; Zhu, H.-L.; Li, H.-B. Vine Tea Kombucha Ameliorates Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in High-Fat Diet Fed Mice via Antioxidation, Anti-Inflammation and Regulation of Gut Microbiota. Food Biosci 2024, 62, 105400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitwetcharoen, H.; Phannarangsee, Y.; Klanrit, P.; Thanonkeo, S.; Tippayawat, P.; Klanrit, P.; Klanrit, P.; Yamada, M.; Thanonkeo, P. Functional Kombucha Production from Fusions of Black Tea and Indian Gooseberry (Phyllanthus Emblica L. ). Heliyon 2024, 10, e40939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laavanya, D.; Shirkole, S.; Balasubramanian, P. Current Challenges, Applications and Future Perspectives of SCOBY Cellulose of Kombucha Fermentation. J Clean Prod 2021, 295, 126454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Chatzinotas, A.; Chakraborty, W.; Bhattacharya, D.; Gachhui, R. Kombucha Tea Fermentation: Microbial and Biochemical Dynamics. Int J Food Microbiol 2016, 220, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuduaibifu, A.; Tamer, C.E. Evaluation of Physicochemical and Bioaccessibility Properties of Goji Berry Kombucha. J Food Process Preserv 2019, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Soto, S.A.; Beaufort, S.; Bouajila, J.; Souchard, J.; Taillandier, P. Understanding Kombucha Tea Fermentation: A Review. J Food Sci 2018, 83, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonarski, E.; Cesca, K.; Zanella, E.; Stambuk, B.U.; de Oliveira, D.; Poletto, P. Production of Kombucha-like Beverage and Bacterial Cellulose by Acerola Byproduct as Raw Material. LWT 2021, 135, 110075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonarski, E.; Cesca, K.; Pinto, C.C.; González, S.Y.G.; de Oliveira, D.; Poletto, P. Bacterial Cellulose Production from Acerola Industrial Waste Using Isolated Kombucha Strain. Cellulose 2022, 29, 7613–7627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shall, F.N.; Al-Shemy, M.T.; Dawwam, G.E. Multifunction Smart Nanocomposite Film for Food Packaging Based on Carboxymethyl Cellulose/Kombucha SCOBY/Pomegranate Anthocyanin Pigment. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 242, 125101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cottet, C.; Salvay, A.G.; Peltzer, M.A.; Fernández-García, M. Incorporation of Poly(Itaconic Acid) with Quaternized Thiazole Groups on Gelatin-Based Films for Antimicrobial-Active Food Packaging. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerrutti, P.; Roldán, P.; García, R.M.; Galvagno, M.A.; Vázquez, A.; Foresti, M.L. Production of Bacterial Nanocellulose from Wine Industry Residues: Importance of Fermentation Time on Pellicle Characteristics. J Appl Polym Sci 2016, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN The 17 Goals. UN 2025.

- Anukiruthika, T.; Sethupathy, P.; Wilson, A.; Kashampur, K.; Moses, J.A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Multilayer Packaging: Advances in Preparation Techniques and Emerging Food Applications. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2020, 19, 1156–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-W.; Ruiz-Garcia, L.; Qian, J.-P.; Yang, X.-T. Food Packaging: A Comprehensive Review and Future Trends. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2018, 17, 860–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, B.; Jayaraman, S.; Balasubramanian, P. Investigating the Effects of Drying on the Physical Properties of Kombucha Bacterial Cellulose: Kinetic Study and Modeling Approach. J Clean Prod 2024, 452, 142204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Tapias, Y.A.; Di Monte, M.V.; Peltzer, M.A.; Salvay, A.G. Bacterial Cellulose Films Production by Kombucha Symbiotic Community Cultured on Different Herbal Infusions. Food Chem 2022, 372, 131346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agüero, A.; Lascano, D.; Ivorra-Martinez, J.; Gómez-Caturla, J.; Arrieta, M.P.; Balart, R. Use of Bacterial Cellulose Obtained from Kombucha Fermentation in Spent Coffee Grounds for Active Composites Based on PLA and Maleinized Linseed Oil. Ind Crops Prod 2023, 202, 116971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasekara, A.S.; Shrestha, A.B.; Wang, D. Chemical Modifications of Kombucha SCOBY Bacterial Cellulose Films by Citrate and Carbamate Cross-Linking. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications 2024, 8, 100595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, A.; Jokar, M.; Mohammadi Nafchi, A. Preparation and Characterization of Biocomposite Film Based on Chitosan and Kombucha Tea as Active Food Packaging. Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 108, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, X.; Gibson, C.T.; Gao, J.; Jellicoe, M.; Wang, H.; Young, D.J.; Raston, C.L. Enhanced Mechanical Strength of Vortex Fluidic Mediated Biomass-Based Biodegradable Films Composed from Agar, Alginate and Kombucha Cellulose Hydrolysates. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 253, 127076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wang, X.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yue, T.; Cai, R.; Muratkhan, M.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Z. A Green Versatile Packaging Based on Alginate and Anthocyanin via Incorporating Bacterial Cellulose Nanocrystal-Stabilized Camellia Oil Pickering Emulsions. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 249, 126134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortazavi Moghadam, F. sadat; Mortazavi Moghadam, F.A. Kombucha Fungus Bio-Coating for Improving Mechanical and Antibacterial Properties of Cellulose Composites. Mater Today Commun 2024, 40, 109609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S. V.; Dulait, K.; Shirkole, S.S.; Thorat, B.N.; Deshmukh, S.P. Dewatering and Drying of Kombucha Bacterial Cellulose for Preparation of Biodegradable Film for Food Packaging. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 280, 136334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Li, B.; Li, L.; Wang, F.; Jia, S.; Xie, Y.; Zhong, C. Cinnamon Essential Oil Pickering Emulsions: Stabilization by Bacterial Cellulose Nanofibrils and Applications for Active Packaging Films. Food Biosci 2023, 56, 103258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koreshkov, M.; Takatsuna, Y.; Bismarck, A.; Fritz, I.; Reimhult, E.; Zirbs, R. Sustainable Food Packaging Using Modified Kombucha-Derived Bacterial Cellulose Nanofillers in Biodegradable Polymers. RSC Sustainability 2024, 2, 2367–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Farias Nascimento, A.; Ramos, S.M.T.; Bergamo, V.N.; dos Santos Araujo, E.; Valencia, G.A. Pickering Emulsions Stabilized Using Bacterial Cellulose From Kombucha. Starch - Stärke 2024. [CrossRef]

- DENG, W.; LI, Y.; WU, L.; CHEN, S. Pickering Emulsions Stabilized by Polysaccharides Particles and Their Applications: A Review. Food Science and Technology 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hu, W.; Dong, J.; Azi, F.; Xu, X.; Tu, C.; Tang, S.; Dong, M. The Use of Bacterial Cellulose from Kombucha to Produce Curcumin Loaded Pickering Emulsion with Improved Stability and Antioxidant Properties. Food Science and Human Wellness 2023, 12, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, A.Q.; Chin, N.L.; Talib, R.A.; Basha, R.K. Application of Scoby Bacterial Cellulose as Hydrocolloids on Physicochemical, Textural and Sensory Characteristics of Mango Jam. J Sci Food Agric 2025, 105, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyappan, V.G.; Vhatkar, S.S.; Bose, S.; Sampath, S.; Das, S.K.; Samanta, D.; Mandal, A.B. Incorporations of Gold, Silver and Carbon Nanomaterials to Kombucha-Derived Bacterial Cellulose: Development of Antibacterial Leather-like Materials. Journal of the Indian Chemical Society 2022, 99, 100278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candra, A.; Ahmed, Y.W.; Kitaw, S.L.; Anley, B.E.; Chen, K.-J.; Tsai, H.-C. A Green Method for Fabrication of a Biocompatible Gold-Decorated-Bacterial Cellulose Nanocomposite in Spent Coffee Grounds Kombucha: A Sustainable Approach for Augmented Wound Healing. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2024, 94, 105477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, V.; Jebathomas, C.R.T.; Sundaramoorthy, S.; Madhan, B.; Palanivel, S. Preparation and Evaluation of Novel Biodegradable Kombucha Cellulose-Based Multi-Layered Composite Tableware. Ind Crops Prod 2024, 215, 118629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Saha, N.; Ngwabebhoh, F.A.; Zandraa, O.; Saha, T.; Saha, P. Silane-Modified Kombucha-Derived Cellulose/Polyurethane/Polylactic Acid Biocomposites for Prospective Application as Leather Alternative. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2023, 36, e00611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzocco, L.; Mikkonen, K.S.; García-González, C.A. Aerogels as Porous Structures for Food Applications: Smart Ingredients and Novel Packaging Materials. Food Structure 2021, 28, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergottini, V.M.; Bernhardt, D. Bacterial Cellulose Aerogel Enriched in Nanofibers Obtained from Kombucha SCOBY Byproduct. Mater Today Commun 2023, 35, 105975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Heo, J.; Priyajanani, J.; Kim, S.H.; Khatun, M.R.; Nagarajan, R.; Noh, I. Simultaneous Processing of Both Handheld Biomixing and Biowriting of Kombucha Cultured Pre-Crosslinked Nanocellulose Bioink for Regeneration of Irregular and Multi-Layered Tissue Defects. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 282, 136966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, N.; Bhuvana, T.; Tiwari, A.; Chandraprakash, C. Aerogel-like Biodegradable Acoustic Foams of Bacterial Cellulose. J Appl Polym Sci 2024, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.A.; Uekane, T.M.; Miranda, J.F. de; Ruiz, L.F.; Motta, J.C.B. da; Silva, C.B.; Pitangui, N. de S.; Gonzalez, A.G.M.; Fernandes, F.F.; Lima, A.R. Kombucha Beverage from Non-Conventional Edible Plant Infusion and Green Tea: Characterization, Toxicity, Antioxidant Activities and Antimicrobial Properties. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2021, 34, 102032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchia, L.O.A.; Almeida, M.E.F. de Health Benefits of Kombucha: Drink and Its Biocellulose Production. Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, K.; Kałduńska, J.; Kochman, J.; Janda, K. Chemical Profile and Antioxidant Activity of the Kombucha Beverage Derived from White, Green, Black and Red Tea. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubczyk, K.; Łopusiewicz, Ł.; Kika, J.; Janda-Milczarek, K.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K. Fermented Tea as a Food with Functional Value—Its Microbiological Profile, Antioxidant Potential and Phytochemical Composition. Foods 2023, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, R.R.; Neto, R.O.; dos Santos D’Almeida, C.T.; do Nascimento, T.P.; Pressete, C.G.; Azevedo, L.; Martino, H.S.D.; Cameron, L.C.; Ferreira, M.S.L.; Barros, F.A.R. de Kombuchas from Green and Black Teas Have Different Phenolic Profile, Which Impacts Their Antioxidant Capacities, Antibacterial and Antiproliferative Activities. Food Research International 2020, 128, 108782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villarreal-Soto, S.A.; Beaufort, S.; Bouajila, J.; Souchard, J.; Taillandier, P. Understanding Kombucha Tea Fermentation: A Review. J Food Sci 2018, 83, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadhan, H.U.; Prayogo; Kenconojati, H.; Rahardja, B.S.; Azhar, M.H.; Budi, D.S. Potential Utilization of Kombucha as a Feed Supplement in Diets on Growth Performance and Feed Efficiency of Catfish (Clarias Sp.). IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2021, 679, 012070. [CrossRef]

- Afsharmanesh, M.; Sadaghi, B. Effects of Dietary Alternatives (Probiotic, Green Tea Powder, and Kombucha Tea) as Antimicrobial Growth Promoters on Growth, Ileal Nutrient Digestibility, Blood Parameters, and Immune Response of Broiler Chickens. Comp Clin Path 2014, 23, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Tank, P.R.; Janbandhu, S.; Motivarash, Y. Ffect of supplementation of white button mushroom, agaricus bisporus (imbach, 1946) on growth performance and survival in white leg shrimp, litopenaeus vannamei (BOONE, 1931). J. Exp. Zool. India 2022, 25, 2521–2528. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, B.E.; Dutton, R.J. Fermented Foods as Experimentally Tractable Microbial Ecosystems. Cell 2015, 161, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanišová, E.; Meňhartová, K.; Terentjeva, M.; Harangozo, Ľ.; Kántor, A.; Kačániová, M. The Evaluation of Chemical, Antioxidant, Antimicrobial and Sensory Properties of Kombucha Tea Beverage. J Food Sci Technol 2020, 57, 1840–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vīna, I.; Semjonovs, P.; Linde, R.; Deniņa, I. Current Evidence on Physiological Activity and Expected Health Effects of Kombucha Fermented Beverage. J Med Food 2014, 17, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polymeric matrix and ingredients | KBC application and treatment | Production method | Major findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMC and anthocyanins extract |

KBC was used as a filler (1 – 15 wt%). KBC was cleaned with deionized water and sodium hydroxide (1 M), and dried at 50 ºC for 20 h | Casting method at 40 ºC for 18 h | The incorporation of KBC increased TS from 1.28 to 18.51 MPa and improved UV-barrier (200 – 400 nm) properties in CMC films containing anthocyanin extract. Films incorporated with KBC increased red grapes and plums' shelf life by up to 25 days | [11] |

| PLA plasticized with maleinized linseed oil |

KBC was used as a filler (3 – 5 wt%). KBC was sterilized, cut into small pieces, and dispersed in deionized water in a 1:2 proportion. Dispersions were homogenized in 4 cycles of 30 s at 30,000 rpm by using an Ultra-turrax. Finally, KBC wad dried at 60 ⁰C for 2 days | Films were produced using a conical twin-screw microextruder. The temperature profile was set up at 195–190–190 ⁰C in the three extrusion areas and screw speed was established at 25 rpm. Formulations were mixed during 3 min. The die temperature was set up at 180 ⁰C and the film drawing speed at 1200 mm/min. Films with a thickness of 100–200 μm were obtained | The incorporation of KBC produced a reduction of film transparency and reduced the transmittance in the UV region of the spectra. Furthermore, EM (1308 → 1639 MPa) and TS (13 → 31 MPa) increased with 5 wt% KBC. Unfortunately, WVTR increased from 82 → 116 g/m2·day with KBC incorporation | [19] |

| KBC | KBC was used as the polymeric matrix. KBC was washed with deionized water (2 ×1.0 L) and pat dried with Kleenex tissues. In sequence, KBC was purified by immersion into a NaOH solution at 90 ºC for 1.0 h. Finally, KBC was dried at 50 ºC for 20 h to obtain films. Finally, films were modified using citric acid and carbamate groups | Films were produced by the casting method at room temperature for 24 h |

Citric acid cross-linking resulted a decrease in TS (25.3 → 7.8 MPa). Whereas carbamate cross-linking with hexamethylene, toluene, methylene di-p-phenyl and 4,4′-methylene-bis(cyclohexyl) linking groups by treatments with corresponding diisocyanates resulted improvements in TS (25.3 → 44.1 ± 7.1 MPa), thermal stability (Tonset 215 → 281.5 ± 33.5 ºC) and reduction in water retention (100 → 60 ± 20 %) properties in KBC films |

[20] |

| Chitosan | KBC was used as a filler (1 – 3 wt%). No kombucha treatment was reported by the authors | Casting method at 50 ºC for 24 h | The incorporation of KBC reduced WVP from 256.7 to 132.1 g·mm/cm2·h·KPa and enhanced the antioxidant activity (59% DPPH), and the protective effect of the film against ultra violet. Furthermore, active films reduced lipid oxidation and microbial growth in minced beef during storage | [21] |

| Agar and alginate | KBC was used as a filler (2.5 wt%). KBC was cleaned by stirring distilled water for 48 h, filtered, and then heated at 50 ºC for 12 h with 1 M NaOH, followed by 1 h treatment with 1 % glacial acetic acid. KBC was washed with distilled water until the pH reached 7. Finally, KBC was freeze-dried. KBC was treated enzymatically with cellulase | Casting method at 45 ºC for 20 h | TS of control films (agar and alginate) decreased from 9.98 MPa to 7.69 MPa with the incorporation of unhydrolyzed KBC, however, TS increased to 18.18 MPa when KBC was incorporated into the polymeric matrix. This result was due to the better uniformity and particle size distribution of KBC | [22] |

| Alginate and anthocyanins | KBC was used as encapsulating material (0.1 – 0.4 wt%). KBC was ground with a crusher for 4 min at 8000 rpm and then centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 10 min. KBC was hydrolyzed using a 50 % (w/v) sulfuric acid solution in a water bath at 45 ºC for 6 h, followed by cleaning with ultra-pure water, centrifugation, and filtering. Hydrolyzed KBC was dialyzed and freeze-dried | Casting method at 45 ºC for 20 h. Oil in water (O/W) Pickering emulsions were produced with camelia oil, water, and KBC as emulsifier, using an ultrasonic dispersion method |

The incorporation of Pickering emulsions containing KBC increased TS from 12 to 33 MPa, reduced transmittance at 280 nm (52 → 3 %) and 660 nm (70 → 5 %), and increased WCA from 31 to 63º. Films containing Pickering emulsions displayed antioxidant activity | [23] |

| KBC | KBC was used as the polymer matrix. KBC was crushed in sterile deionized water and then homogenized at 10,000 rpm by Ultra-Turrax | N.i. | Materials based on KBC had elongation at break of 2 % and antimicrobial activity against S. aureus and E. coli | [24] |

| KBC, KBC and glycerol or KBC with chitosan | KBC was used as the polymer matrix. KBC was cleaned with NaOH (2 M) at 90 ºC for 2 h, and then washed with deionized water 5–6 times. In sequence, KBC was treated with NaClO (2 M) at room temperature for 2 h and finally washed with deionized water for 1 h | Films were produced by drying KBC with hot air (temperature not informed). Furthermore, KBC was immersed in glycerol of chitosan solutions for 10 min at room temperature, followed by drying to obtain KBC plasticized with glycerol and composite KBC/chitosan films | The incorporation of glycerol and chitosan increased film thickness (45 → 130 μm), density (6 → 15 g/m2), and TS (50 → 110 MPa). KBC, KBC with glycerol, and KBC/chitosan films extended the shelf life of tomatoes by 12, 13, and 15 days when compared with uncoated tomatoes (7 days) | [25] |

| Gelatin | KBC was used as the encapsulating material (0.1 – 1 wt%). KBC was cleaned with NaOH (0.1 M) and then washed with distilled water | O/W Pickering emulsions were produced with cinnamon essential oil and KBC. Gelatin films were produced by the casting method with 1 – 12 % of Pickering emulsions. Films were dried at 25 ºC for 48 h | Gelatin films containing 1% of Pickering emulsion had yellow color, homogeneous visual aspect, and antibacterial activities against S. aureus and E. coli | [26] |

| PLA and PHBV | KBC was used as a filler (5 wt%). KBC was homogenized with distilled water at 25000 rpm and treated by adding NaOH to the dispersion. The resulting mixture was centrifuged, washed, and freeze dried | Films were produced by extrusion (twin-screw microextruder) at 180 ºC and 100 rpm for 2 min | Mechanical properties of PLA (EM ≈ 1.7 GPa, TS ≈ 61 MPa, and EB ≈ 4.2 %) and PHBV (EM ≈ 2.2 GPa, TS ≈ 31 MPa, and EB ≈ 9.0 %) were not altered with the incorporation of KB, however, the film biodegradability increased with the incorporation of KBC. Furthermore, KBC incorporation resulted in a ∼23 % and ∼45 % decrease in O2 permeability for PLLA and PHBV, respectively | [27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).