Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: There is controversy if Merkel cell carcinomas (MCCs) spread to lymph nodes or distant metastases (DM) first. Methods: Data from six institutions (March 1982 to Feb 2015) formed an aggregated database of 303 patients. The primary outcome was recurrence patterns. Results: (a) More patients presented with lymph node metastases (LNM) than DM, 19.5% (59/303) versus 2.6% (8/303). (b) 26.1% (79/303) had lifetime DM, of whom 47/79 also developed LNM: 31/47 (66%) prior to DM. (c) A shorter median time interval of 1.5 (range: 0-47.0) months from initial diagnosis to LNM; and 8 (0-107.8) months from diagnosis to DM. Another additional observation was 7/79 patients with initial primaries <1 cm in maximum dimension developed DM in their lifetime, the smallest being 0.2 cm. Conclusions: Three observations favor prior LNM giving rise to subsequent DM as the main pathway of dissemination in MCC. These observations are especially important in developing countries with inadequate staging resources for patient management. Even small MCCs <1 cm in maximum dimension, including a 0.2 cm primary, can metastasize. Therefore, we believe this report might be practice-changing since some thought these small primaries do not require any adjuvant therapy.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADMEC-O | Adjuvant immunotherapy with nivolumab versus observation |

| ADT | Androgen deprivation therapy |

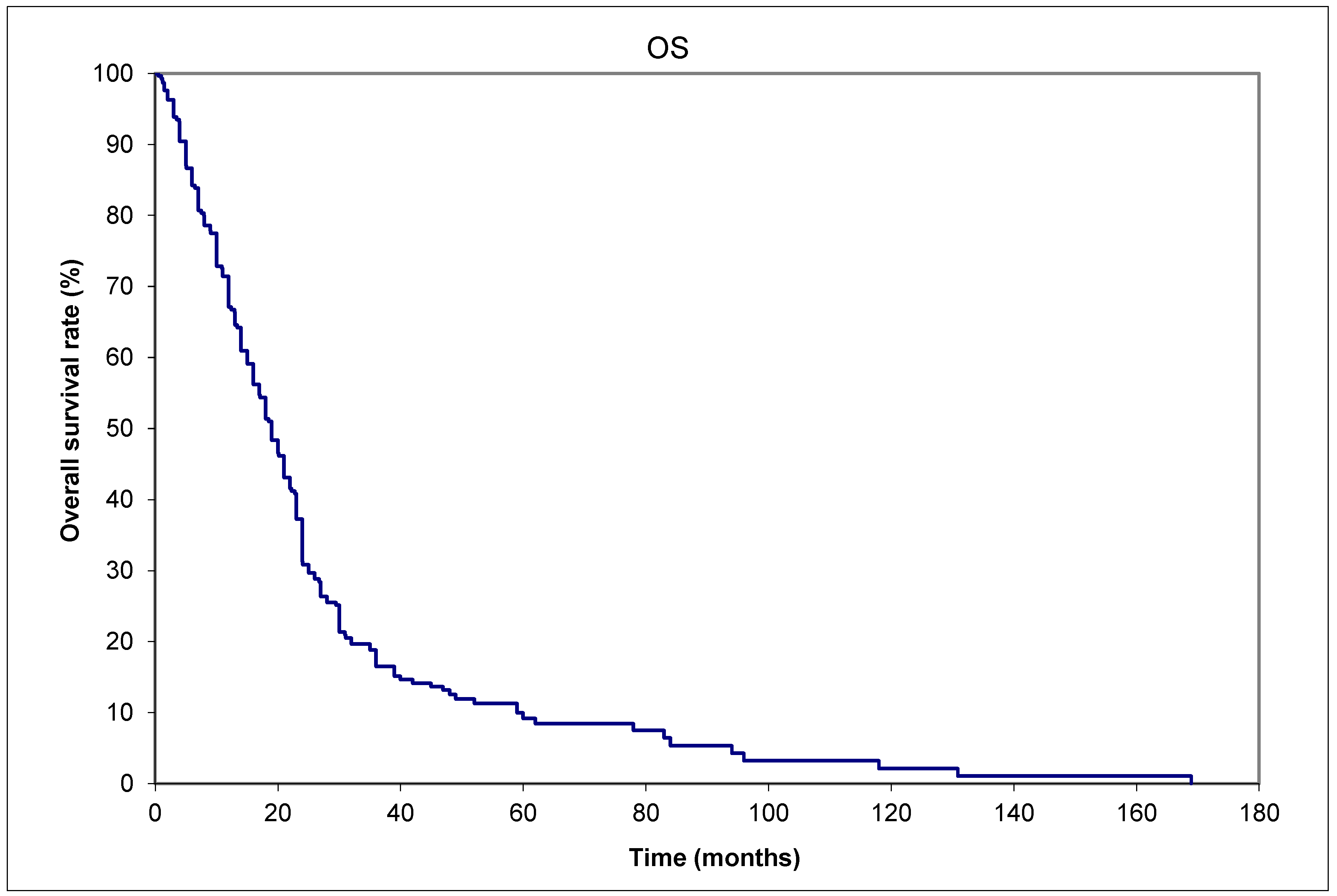

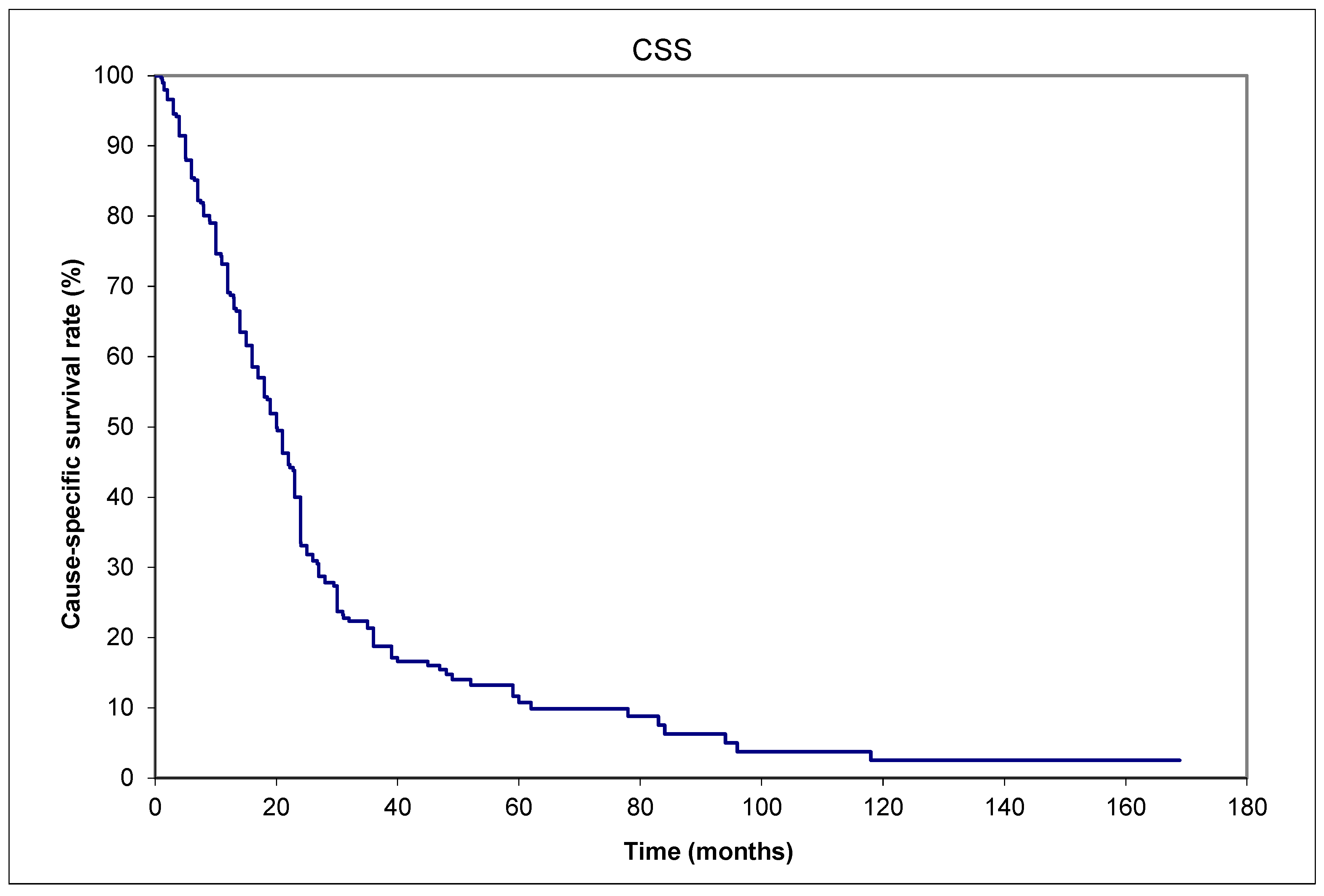

| CSS | Cause-specific survival |

| CT | Computerized tomography |

| DFS | Disease-free survival |

| DM | Distant metastases |

| LNM | Lymph node metastases |

| MCC | Merkel cell carcinoma |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| SLNB | Sentinel lymph node biopsy |

References

- Tai, P.; Park, S.Y.; Nghiem, P.T. Pathogenesis, clinical features, and diagnosis of Merkel cell (neuroendocrine) carcinoma. In: UpToDate, Canellos, GP, Schnipper L (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2024. Accessed: October 14, 2024: www.uptodate.com.

- Tilling, T.; Moll, I. Which are the cells of origin in Merkel cell carcinoma? J Skin Cancer. 2012, 2012, 680410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, P.; Au, J. Skin cancer management—updates on Merkel cell carcinoma. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 282–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillenwater AM, Hessel AC, Morrison WH, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: effect of surgical excision and radiation on recurrence and survival. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001, 127, 149–154. [CrossRef]

- Queirolo, P.; Gipponi, M.; Peressini, A.; Raposio, E.; Vecchio, S.; Guenzi, M.; Sertoli, M.R.; Santi, P.; Cafiero, F. Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. Treatment of primary, recurrent and metastatic disease: review of clinical cases. Anticancer Res. 1997, 17, 2339–2342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gunaratne, D.A.; Howle, J.R.; Veness, M.J. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in Merkel cell carcinoma: a 15-year institutional experience and statistical analysis of 721 reported cases. Br J Dermatol. 2016, 174, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, N.S.; Morton, B.; Smith, J.W. Merkel cell cancer: is prophylactic lymph node dissection indicated? Am Surg. 1996, 62, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Santamaria-Barria, J.A.; Boland, G.M.; Yeap, B.Y.; Nardi, V.; Dias-Santagata, D.; Cusack, J.C. Merkel Cell Carcinoma: 30-Year Experience from a Single Institution. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 20, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.C.; Ugurel, S.; Leiter, U.; Meier, F.; Gutzmer, R.; Haferkamp, S.; Zimmer, L.; Livingstone, E.; Eigentler, T.K.; Hauschild, A.; et al. Adjuvant immunotherapy with nivolumab versus observation in completely resected Merkel cell carcinoma (ADMEC-O): disease-free survival results from a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2023, 402, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, E.L.; Meier, P. Non-parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958, 53, 457–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, DR. Regression Models and Life-Tables. J Royal Statistical Soc. 1972, 34, 187–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coggshall K, Tello TL, North JP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: An update and review: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018, 78, 433–442. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai P, Park SY, Nghiem PT, et al. Staging and treatment, and surveillance of locoregional Merkel cell carcinoma. In: UpToDate, Canellos, GP, Schnipper L (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2024. www.uptodate.com. (last accessed 15 May 2024).

- Park SY, Nghiem PT, Tai P, et al. Treatment of recurrent and metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. In: UpToDate, Canellos, GP, Schnipper L (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2024. www.uptodate.com. (last accessed 15 May 2024).

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline website: www.nccn.org (last accessed 15 May 2024).

- Kaufman HL, Russell JS, Hamid O, et al. Updated efficacy of avelumab in patients with previously treated metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma after ≥1 year of follow-up: JAVELIN Merkel 200, a phase 2 clinical trial. J Immunother Cancer. 2018, 6, 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman HL, Russell J, Hamid O, et al. Avelumab in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: a multi-center, single-group, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 1374–1385. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai PTH, Yu E, Winquist E, et al. Chemotherapy in neuroendocrine / Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin [MCC]: case series and review of 204 cases. J Clin Oncol 2000, 18, 2493–2499. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, N.A.; Schaub, S.K.; Goff, P.H.; Hippe, D.S.; Park, S.Y.; Lachance, K.; Bierma, M.; Liao, J.J.; Apisarnthanarax, S.; Bhatia, S.; et al. Increased risk of recurrence and disease-specific death following delayed postoperative radiation for Merkel cell carcinoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 90, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Aggregated data from | Saskatchewan (Canada) | 13 (16%) | ||||

| Alberta (Canada) | 17 (22%) | |||||

| London, Ontario (Canada) | 5 (19%) | |||||

| Windsor/Ontario,Canada | 5 (6%) | |||||

| Amiens (France) | 9 (11%) | |||||

| Westmead, New South Wales (Australia) | 20 (25%) | |||||

| Baseline characteristics | Age: | median 78 (range:47-95) years | ||||

| Sex: | 29 males & 50 females | |||||

| Size of primary tumor: | median 2.5 (range: 0.2 -17) cm | |||||

| Initial stages | Local | Nodal | Distant metastases | |||

| Unknown | ||||||

| Clinical | 42 (53%) | 28 (35%) | 8 (10%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Pathological | 35 (44%) | 35 (44%) | 8 (10%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| Primary site | Head and neck | 35 (44%) | ||||

| Limb (upper or lower) | 23 (29%) | |||||

| Trunk | 13 (16%) | |||||

| Unknown primary, presented with nodes only | 8 (10%) | |||||

| Timing of nodal metastases (patient number=47) | Before distant metastases diagnosis | 31/47 (66%) | ||||

| Within 1 month of distant metastases diagnosis | 10/47 (21%) | |||||

| After distant metastases diagnosis | 1/47 (2%) | |||||

| Unknown time relative to distant metastases | 5/47 (11%) | |||||

| Treatment of localized disease at presentation (patient number=43) | Surgery | 24/43 (56%) |

| Surgery+Radiotherapy | 11/43 (26%) | |

| Surgery+Chemotherapy | 1/43 (2%) | |

| Radiotherapy alone | 4/43 (9%) | |

| Radiotherapy+Chemotherapy | 1/43 (2%) | |

| None | 2/43 (5%) | |

| Treatment of nodal metastases at presentation (patient number=28) | Surgery | 6/28 (21%) |

| Surgery+Radiotherapy | 7/28 (25%) | |

| Surgery+Radiotherapy+Chemotherapy | 2/28 (7%) | |

| Radiotherapy alone | 13/28 (46%) | |

| Treatment of distant metastases at presentation (patient number=8) |

Radiotherapy+Chemotherapy | 3/8 (38%) |

| Chemotherapy alone | 2/8 (25%) | |

| None | 3/8 (38%) | |

| Final vital status | Alive | 8/79 (10%) |

| Dead | 71/79 (90%) | |

| Cause of death among those expired (patient number=71) | Merkel cell carcinoma |

65/71 (92%) |

| Intercurrent disease | 6/71 (8%) |

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | (95% Confidence interval) | P values | |

| Age: | 60 | Reference variable | ||

| 70 | 0.90 | (0.64-1.26) | 0.50 | |

| 80 | 1.06 | (0.66-1.68) | 0.82 | |

| 90 | 1.75 | (0.89-3.46) | 0.11 | |

| Sex | Male | 0.87 | (0.54-1.42) | 0.59 |

| Female | Reference variable | |||

| Chemotherapy: | Yes | 0.56 | (0.19-1.62) | 0.29 |

| No | Reference variable | |||

| Clinical stage: | Localized disease | 2.53 | (1.21-5.28) | 0.013 |

| Primary <1 cm | Reference variable | |||

| Primary >1 cm | 1.32 | (0.61-2.89) | 0.49 | |

| Nodal metastases | 3.27 | (1.85-5.78) | <0.001 | |

| Distant metastases | 21.42 | (7.15-64.21) | <0.001 | |

| Previous irradiation: | Yes | 2.95 | (0.90-9.61) | 0.073 |

| No | Reference variable | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).