Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

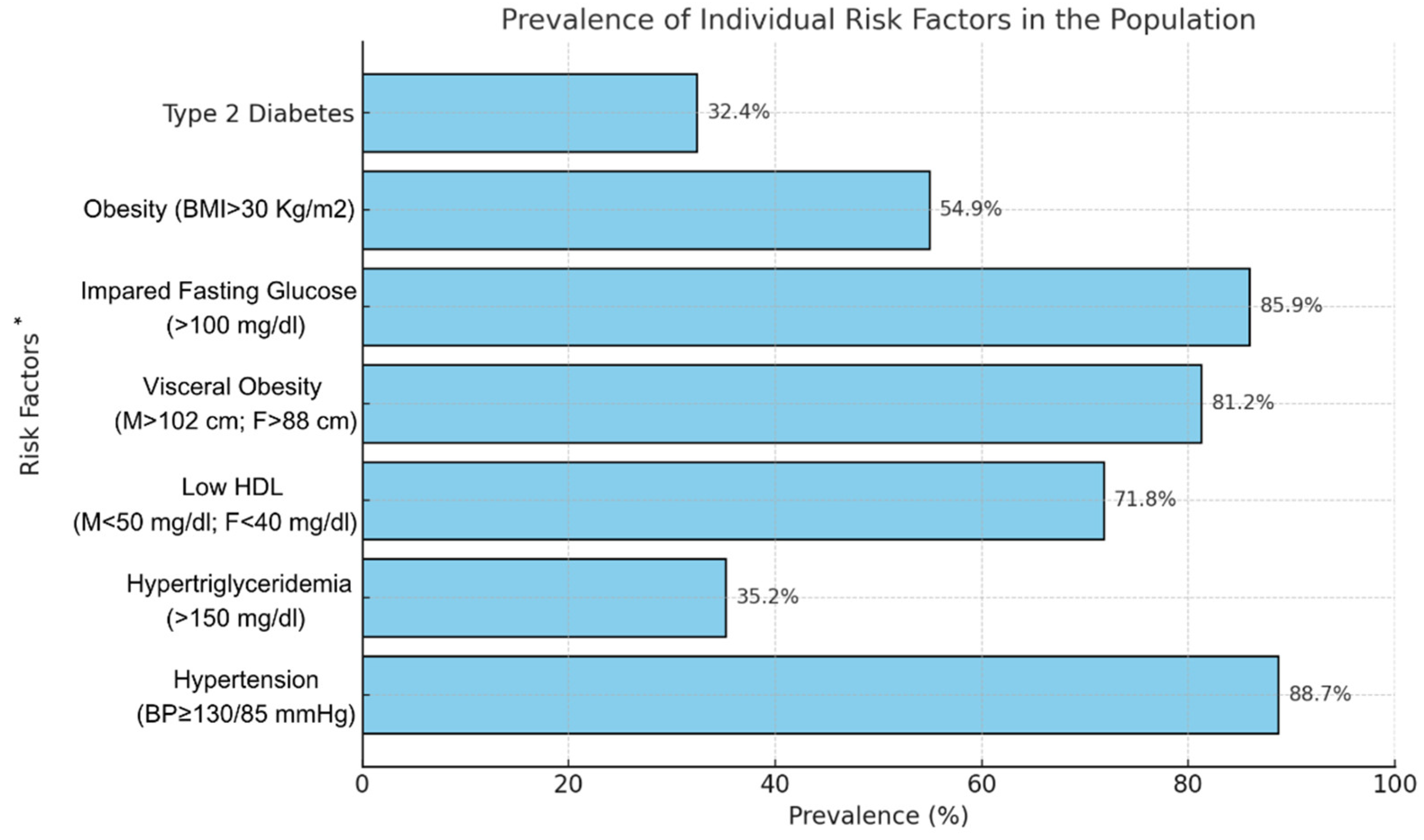

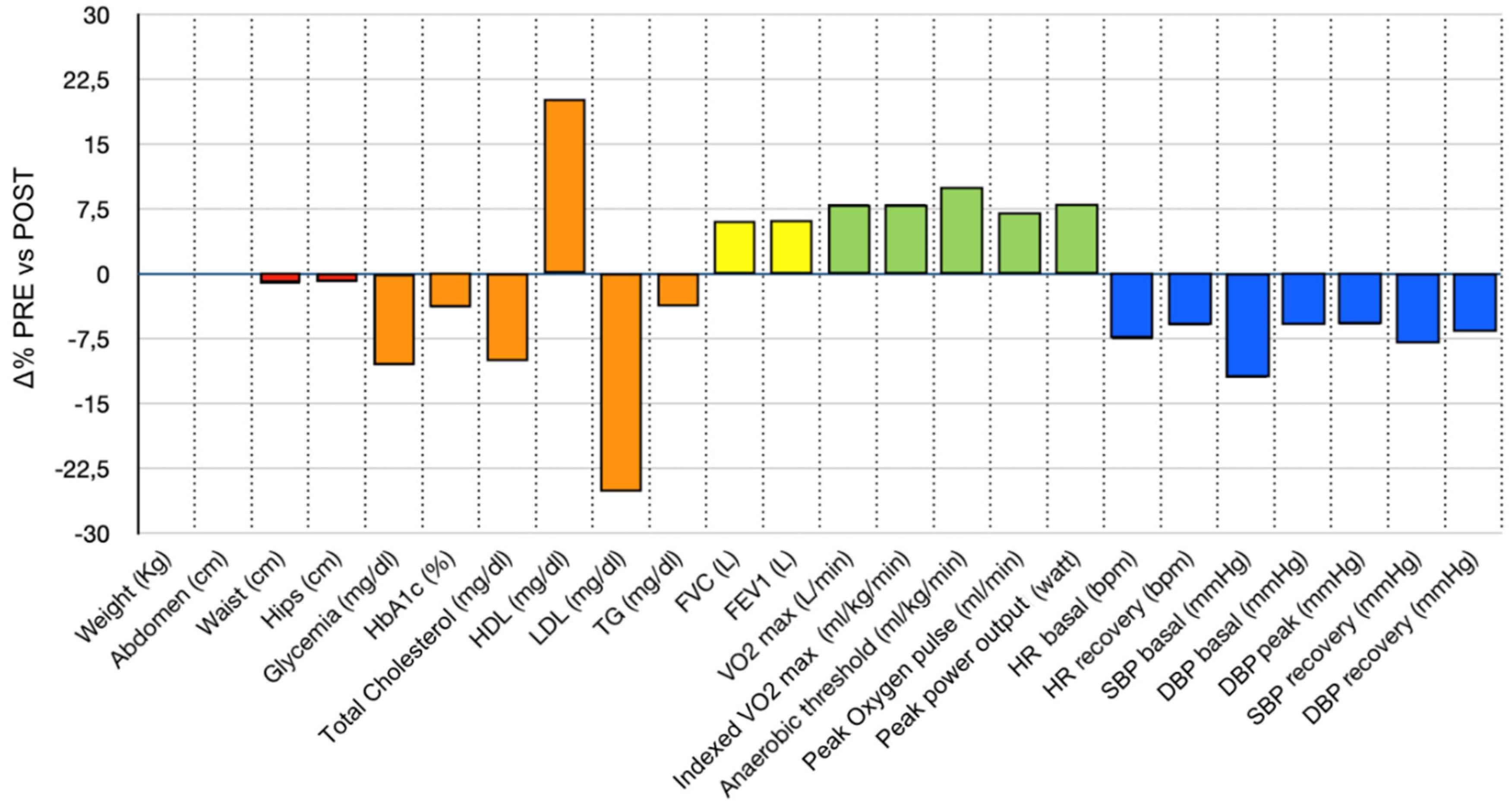

Background: Metabolic syndrome (MS) is a cluster of cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors that increase the likelihood of both acute events and chronic conditions. While exercise has been shown to improve individual risk factors associated with MS, research on its effects on MS as an integrated condition remains limited. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a 6-month Adapted Personalized Motor Activity (AMPA) program in improving health outcomes in individuals with MS. Methods: Seventy-one sedentary participants with MS (mean age: 63 ± 9.4 years; 46.5% female) completed a 6-month intervention incorporating moderate-intensity aerobic and resistance training. Each participant received a personalized exercise plan prescribed by a sports medicine physician. Training was monitored via telemetry to ensure safety. No dietary recommendations were provided during the intervention. Baseline and post-intervention assessments included Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing (CPET), anthropometric measurements, blood pressure, heart rate, lipid profile (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and triglycerides), fasting glucose, and HbA1c. Results: Significant improvements were observed in fasting glucose (-10.6%; p < 0.001), HbA1c (-3.88%; p < 0.001), HDL cholesterol (+20.8%; p < 0.001), LDL cholesterol (-25.1%; p < 0.001), and VO₂ max (+8.6%; p < 0.001). Systolic and diastolic blood pressure also decreased significantly, with reductions of -12% (p < 0.001) and -5.9% (p < 0.001), respectively. Reductions in weight and waist circumference were statistically significant but modest and clinically irrelevant, showing no correlation with improvements in cardio-metabolic parameters. Logistic regression and correlation matrix analyses were performed to identify key predictors of changes in individual risk factors. Conclusions: While personalized exercise alone may not fully control individual risk factors of metabolic syndrome, its overall effect is comparable to low-intensity pharmacological polytherapy with minimal adverse effects. These benefits appear to be independent of dietary habits, gender, and both baseline and post-intervention physical performance and anthropometric measures.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

- Aged between 40 and 75;

- Diagnosis of metabolic syndrome according to the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III [21] criteria;

- No participation in structured physical activity programs within the six months prior to the study.

- History of musculoskeletal, neurological, or orthopedic disorders in the preceding six months that could hinder participation in the experimental protocol;

- Acute cardiovascular conditions contraindicating physical activity;

- Active cancer, infectious diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or active smoking

- Inability to provide informed consent.

2.2. Experimental Design

- Metabolic parameters (fasting glycemia, HbA1c, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and triglycerides)

- Anthropometric measures (wight, BMI, waist and hip circumference)

- Cardiopulmonary performance (HR, blood pressure, FVC, FEV1 and VO2)

2.3. Training Protocol

- Aerobic Training:

- Treadmill walking

- Cycling

- Elliptical training

- Resistance Training:

- 2–3 sets of 8–15 repetitions for each major muscle group, with 1–3 minutes of rest between sets.

- Weight machines were used to ensure correct form and safety during the exercises.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

| Outcome | Baseline Predictors | β | SE | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDL cholesterol (%Δ) | Baseline LDL | −0.377 | 0.110 | 0.001 |

| Triglycerides (%Δ) | Baseline triglycerides | −0.233 | 0.081 | 0.007 |

| Baseline fasting glucose | −0.411 | 0.129 | 0.003 | |

| HDL cholesterol (%Δ) | Age | −0.655 | 0.252 | 0.013 |

| Baseline HDL | −0.847 | 0.279 | 0.004 | |

| Fasting glucose (%Δ) | Baseline fasting glucose | −0.295 | 0.061 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (%Δ) | Baseline LDL | 0.089 | 0.045 | 0.057 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (%Δ) | Baseline triglycerides | 0.037 | 0.020 | 0.077 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MS | Metabolic Syndrome |

| AMPA | Adapted Personalized Motor Activity |

| CPET | Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| HbA1c | Glycated Hemoglobin |

| VO2max | Maximum Oxygen Consumption |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| FVC | Forced Vital Capacity |

| FEV1 | Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 Second |

| HR | Heart Rate |

| SBP | Systolic Blood Pressure |

| DBP | Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| ACSM | American College of Sports Medicine |

| RM | Repetition Maximum |

| IDF | International Diabetes Federation |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Noubiap, J.J.; Nansseu, J.R.; Lontchi-Yimagou, E.; Nkeck, J.R.; Nyaga, U.F.; Ngouo, A.T.; Tounouga, D.N.; Tianyi, F.L.; Foka, A.J.; Ndoadoumgue, A.L.; Bigna, J.J. Geographic distribution of metabolic syndrome and its components in the general adult population: A meta-analysis of global data from 28 million individuals. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirode, G.; Wong, R.J. Trends in the Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in the United States, 2011–2016. JAMA 2020, 323, 2526–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, E.T.-C.; Wongpipit, W.; Li, H.-Y.; Wong, S.H.-S.; Siu, P.M.; Kong, A.P.-S.; Johnson, N.A. High-intensity interval training for cardiometabolic health in adults with metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Sports Med. 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naci, H.; Salcher-Konrad, M.; Dias, S.; Blum, M.R.; Sahoo, S.A.; Nunan, D.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. How does exercise treatment compare with antihypertensive medications? A network meta-analysis of 391 randomised controlled trials assessing exercise and medication effects on systolic blood pressure. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.D.; Arena, R.; Riebe, D.; Pescatello, L.S. ACSM’s new preparticipation health screening recommendations from ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription, ninth edition. Available online: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/pau-uap/paguide/ (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Myers, J.; Prakash, M.; Froelicher, V.; Do, D.; Partington, S.; Atwood, J.E. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.V.; Murthy, V.L.; Abbasi, S.A.; Blankstein, R.; Kwong, R.Y.; Goldfine, A.B.; Jerosch-Herold, M.; Lima, J.A.C.; Ding, J.; Allison, M.A.; Visceral adiposity and the risk of metabolic syndrome across body mass index: The MESA Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. Imaging 2014. Available online: http://imaging.onlinejacc.org (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Colberg, S.R.; Sigal, R.J.; Yardley, J.E.; Riddell, M.C.; Dunstan, D.W.; Dempsey, P.C.; Horton, E.S.; Castorino, K.; Tate, D.F. Physical activity/exercise and diabetes: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, B.J.; Schleh, M.W.; Ahn, C.; Ludzki, A.C.; Gillen, J.B.; Varshney, P.; van Pelt, D.W.; Pitchford, L.M.; Chenevert, T.L.; Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; et al. Moderate-intensity exercise and high-intensity interval training affect insulin sensitivity similarly in obese adults. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, E2941–E2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; Badimon, L.; Chapman, M.J.; De Backer, G.G.; Delgado, V.; Ference, B.A.; Graham, I.M.; Halliday, A.; Landmesser, U.; Mihaylova, B.; Pedersen, T.R.; Riccardi, G.; Richter, D.J.; Sabatine, M.S.; Taskinen, M.-R.; Tokgozoglu, L.; Wiklund, O.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias: Lipid Modification to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk: The Task Force for the Management of Dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 111–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, A.S.; Rice, T.; Mandel, S.; Després, J.P.; Bergeron, J.; Gagnon, J.; Rao, D.C.; Skinner, J.S.; Wilmore, J.H.; Bouchard, C. Blood Lipid Response to 20 Weeks of Supervised Exercise in a Large Biracial Population: The HERITAGE Family Study. Metabolism 2000, 49(4), 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, W.E.; Houmard, J.A.; Duscha, B.D.; Knetzger, K.J.; Wharton, M.B.; McCartney, J.S.; Bales, C.W.; Henes, S.; Samsa, G.P.; Otvos, J.D.; Kulkarni, K.R.; Slentz, C.A. Effects of the Amount and Intensity of Exercise on Plasma Lipoproteins. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347(19), 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, S.; Schaller, G.; Mittermayer, F.; Pleiner, J.; Mihaly, J.; Niessner, A.; Richter, B.; Steiner-Boeker, S.; Penak, M.; Strasser, B.; Wolzt, M. Exercise training improves low-density lipoprotein oxidability in untrained subjects with coronary artery disease. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2006, 87, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelissen, V.A.; Fagard, R.H. Effects of endurance training on blood pressure, blood pressure-regulating mechanisms, and cardiovascular risk factors. Hypertension 2005, 46, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffour-Awuah, B.; Man, M.; Goessler, K.F.; Cornelissen, V.A.; Dieberg, G.; Smart, N.A.; Pearson, M.J. Effect of exercise training on the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system: a meta-analysis. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2024, 38, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberti, V.; Nardini, S.; Romano, P.; Menegon, T. ; Lamberti, Sr, V. Title of the article. Medicina dello Sport, /: 135–146. Available online: https, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lamberti, V.; Palermi, S.; Franceschin, A.; Scapol, G.; Lamberti, V.; Lamberti, C.; Vecchiato, M.; Spera, R.; Sirico, F.; Valle, E.d. The effectiveness of Adapted Personalized Motor Activity (AMPA) to improve health in individuals with mental disorders and physical comorbidities: A randomized controlled trial. Sports 2022, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. The IDF Consensus Worldwide Definition of the Metabolic Syndrome, /: online: https, 2023.

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed. /: online: https, 2021.

- Lipsy, R. J. (2003). The National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy: JMCP. [CrossRef]

- Radtke, T.; Crook, S.; Kaltsakas, G.; Louvaris, Z.; Berton, D.; Urquhart, D. S.; Kampouras, A.; Rabinovich, R. A.; Verges, S.; Kontopidis, D.; Boyd, J.; Tonia, T.; Langer, D.; De Brandt, J.; Goërtz, Y. M. J.; Burtin, C.; Spruit, M. A.; Braeken, D. C. W.; Dacha, S.; Franssen, F. M. E.; Hebestreit, H. (2019). ERS statement on standardisation of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in chronic lung diseases. European Respiratory Review: An Official Journal of the European Respiratory Society, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S. K.; Howley, E. T. Exercise Physiology: Theory and Application to Fitness and Performance, 10th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781259870453. [Google Scholar]

- Rhea, M. R.; Alderman, B. L. A Meta-Analysis of Periodized versus Nonperiodized Strength and Power Training Programs. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2004, 75(4), 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The jamovi project (2022). jamovi. (Version 2.3) [Computer Software]. Retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org.

- R Core Team (2021); R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 4.1) [Computer software]. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org. (R packages retrieved from MRAN snapshot 2022-01-01)46.

- Weatherwax, R. M.; Ramos, J. S.; Harris, N. K.; Kilding, A. E.; Dalleck, L. C. Changes in Metabolic Syndrome Severity Following Individualized Versus Standardized Exercise Prescription: A Feasibility Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2594 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passoni, E.; Lania, A.; Adamo, S.; Grasso, G. S.; Noè, D.; Miserocchi, G.; Beretta, E. Mild Training Program in Metabolic Syndrome Improves the Efficiency of the Oxygen Pathway. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2015, 208, 8–14 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. L. , Slentz, C. E. ( 100(12), 1759–1766. [CrossRef]

- Halle, M.; Papadakis, M. A New Dawn of Managing Cardiovascular Risk in Obesity: The Importance of Combining Lifestyle Intervention and Medication. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45(13), 1143–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, N.A.; Downes, D.; van der Touw, T.; Hada, S.; Dieberg, G.; Pearson, M.J.; Wolden, M.; King, N.; Goodman, S.P.J. The Effect of Exercise Training on Blood Lipids: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2024, Advance online publication. . [CrossRef]

- Pattyn, N. , Cornelissen, V. A., Eshghi, S. R., & Vanhees, L. (2013). The effect of exercise on the cardiovascular risk factors constituting the metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Sports Medicine, 43(2), 121-133. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, D. Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Lipids and Lipoproteins. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 132 . [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.; Ryan, B. J.; Schleh, M. W.; Varshney, P.; Ludzki, A. C.; Gillen, J. B.; Van Pelt, D. W.; Pitchford, L. M.; Howton, S. M.; Rode, T.; Hummel, S. L.; Burant, C. F.; Little, J. P.; Horowitz, J. F. Exercise Training Remodels Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue in Adults with Obesity Even Without Weight Loss. J. Physiol. 2022, 600(9), 2127–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kastorini, C. M.; Milionis, H. J.; Esposito, K.; Giugliano, D.; Goudevenos, J. A.; Panagiotakos, D. B. The effect of Mediterranean diet on metabolic syndrome and its components: A meta-analysis of 50 studies and 534,906 individuals. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 57(11), 1299–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, H.; Vargas, M. A.; Gaio, J.; Cofie, P. L.; Reis, W. P.; Peters, W.; Berk, L. Cardiorespiratory fitness decreases high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and improves parameters of metabolic syndrome. Cureus 2024, 16(6), e63317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, N. A.; Hopkins, M.; Caudwell, P.; Stubbs, R. J.; Blundell, J. E. Beneficial effects of exercise: shifting the focus from body weight to other markers of health. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2009, 43(12), 924–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haapala, E. A. , Tompuri, T., Lintu, N., Viitasalo, A., Savonen, K., Lakka, T. A., & Laukkanen, J. A. (2022). Is low cardiorespiratory fitness a feature of metabolic syndrome in children and adults?. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 25(11), 923–929. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, D. E. , McGuire, M. A. ( 157(5 Pt 1), 1489–1497. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K. and Saltin, B. (2015), Exercise as medicine – evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 25: 1-72. [CrossRef]

- Norha, J. , Sjöros, T., Garthwaite, T., Laine, S., Saarenhovi, M., Kallio, P., Laitinen, K., Houttu, N., Vähä-Ypyä, H., Sievänen, H., Löyttyniemi, E., Vasankari, T., Knuuti, J., Kalliokoski, K. K., & Heinonen, I. H. A. (2023). Effects of reducing sedentary behavior on cardiorespiratory fitness in adults with metabolic syndrome: A 6-month RCT. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 33(8), 1452–1461. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Palomo, F. , Moreno-Cabañas, A., Ramírez-Jiménez, M., Álvarez-Jiménez, L., Valenzuela, P. L., Lucía, A., Ortega, J. F., & Mora-Rodríguez, R. (2021). Exercise reduces medication for metabolic syndrome management: A 5-year follow-up study. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 53(7), 1319–1325. . [CrossRef]

- Nasi, M. , Patrizi, G., Pizzi, C., Landolfo, M., Boriani, G., Dei Cas, A., Cicero, A. F. G., Fogacci, F., Rapezzi, C., Sisca, G., Capucci, A., Vitolo, M., Galiè, N., Borghi, C., Berrettini, U., Piepoli, M., & Mattioli, A. V. (2019). The role of physical activity in individuals with cardiovascular risk factors: an opinion paper from Italian Society of Cardiology-Emilia Romagna-Marche and SIC-Sport. Journal of cardiovascular medicine (Hagerstown, Md.), 20(10), 631–639. . [CrossRef]

- Lal, B. , Iqbal, A., Butt, N. F., Randhawa, F. A., Rathore, R., & Waseem, T. (2018). Efficacy of high dose Allopurinol in reducing left ventricular mass in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy by comparing its efficacy with Febuxostat - a randomized controlled trial. JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 68(10), 1446–1450.

- Cartee, G. D. (2015). Mechanisms for greater insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in normal and insulin-resistant skeletal muscle after acute exercise. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism, 309(12), E949–E959. . [CrossRef]

- Šarabon, N. , Kozinc, Ž., Löfler, S., & Hofer, C. (2020). Resistance Exercise, Electrical Muscle Stimulation, and Whole-Body Vibration in Older Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(9), 2902. [CrossRef]

- Tan, A. , Thomas, R. L., Campbell, M. D., Prior, S. L., Bracken, R. M., & Churm, R. (2023). Effects of exercise training on metabolic syndrome risk factors in post-menopausal women - A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland), 42(3), 337–351. [CrossRef]

- Sparks, L. M. , Johannsen, N. M., Church, T. S., Earnest, C. P., Moonen-Kornips, E., Moro, C., Hesselink, M. K., Smith, S. R., & Schrauwen, P. (2013). Nine months of combined training improves ex vivo skeletal muscle metabolism in individuals with type 2 diabetes. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 98(4), 1694–1702. [CrossRef]

- Pinckard, K. , Baskin, K. I. ( 6, 69. [CrossRef]

- Regensteiner, J. G. , Sippel, J., McFarling, E. T., Wolfel, E. E., & Hiatt, W. R. (1995). Effects of non-insulin-dependent diabetes on oxygen consumption during treadmill exercise. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 27(6), 875–881.

- Faselis, C. , Doumas, M., Kokkinos, J. P., Panagiotakos, D., Kheirbek, R., Sheriff, H. M., Hare, K., Papademetriou, V., Fletcher, R., & Kokkinos, P. (2012). Exercise capacity and progression from prehypertension to hypertension. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex.: 1979), 60(2), 333–338. [CrossRef]

- Herrod, P. J. J. , Doleman, B., Blackwell, J. E. M., O’Boyle, F., Williams, J. P., Lund, J. N., & Phillips, B. E. (2018). Exercise and other nonpharmacological strategies to reduce blood pressure in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension: JASH, 12(4), 248–267. [CrossRef]

- Venturelli, M. , Cè, E., Limonta, E., et al. (2015). Effects of endurance, circuit, and relaxing training on cardiovascular risk factors in hypertensive elderly patients. AGE, 37(101). [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. , Hsu, F. C., Isom, S., Walkup, M. P., Kritchevsky, S. B., Goodpaster, B. H., Church, T. S., Pahor, M., Stafford, R. S., & Nicklas, B. J. (2012). Effects of a 12-month physical activity intervention on prevalence of metabolic syndrome in elderly men and women. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 67(4), 417–424. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M. G. , La Gerche, A. E. ( 50(1), 25–30. [CrossRef]

- Jae, S. Y. , Kurl, S. A. ( 27(19), 2220–2222. [CrossRef]

- Jarrete, A. P. , Novais, I. P., Nunes, H. A., Puga, G. M., Delbin, M. A., & Zanesco, A. (2014). Influence of aerobic exercise training on cardiovascular and endocrine-inflammatory biomarkers in hypertensive postmenopausal women. Journal of Clinical & Translational Endocrinology, 1(3), 108–114. [CrossRef]

- Golbidi, S. , Mesdaghinia, A. ( 2012, 349710. [CrossRef]

| PRE INTERVENTION Mean (± SD) or Median (min-max) |

POST INTERVENTION Mean (± SD) or Median (min-max) |

p | Δpre-post Mean (± SD) or Median (min-max) |

Δ%pre-post Mean (± SD) or Median (min-max) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N° of pills | 3.0 (0–15) | 3.0 (0–15) | 0.025 | 0 (-3–2) | - |

| Weight (Kg) | 84.0 (47–125) | 84.0 (48–125) | 0.03 | 0 (-11–5) | 0 (-15.3–4.8) |

| Waist (cm) | 103.0 (65–131) | 102.0 (68–132) | < .001 | -1 (-12–6) | -1.1 (-13.5–8.5) |

| Hips (cm) | 106.0 (74–142) | 104.0 (85–142) | 0.008 | -1 (-14–11) | -1 (-14.6–12.9) |

| Glycemia (mg/dl) | 120.0 (86–340) | 107.0 (78–246) | < .001 | -11 (-144–65) | -10.6 (-73.5–34.9) |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.6 (2.83–14.6) | 6.4 (4.9–9.7) | < .001 | -0.2 (-6.2–1.8) | -3.88 (-73.8–18.6) |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 205.0 (79–324) | 182.0 (115–278) | < .001 | -19 (-87–98) | -10 (-54–55) |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 41.5 (± 11.3) | 53.9 (± 13.4) | < .001 | 12.47 (±11.64) | 20.8 (±18.6) |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 148.9 (± 34.8) | 121.6 (± 25.8) | < .001 | -27.3 (±33.3) | -25.1 (±30.3) |

| TG (mg/dl) | 152.0 (46–403) | 141.0 (58–459) | 0.18 | -5 (-206–89) | -3.6 (-191.7–52.5) |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 5.9 (± 1.3) | 5.6 (± 1.1) | 0.012 | - | - |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.83 (0.53–1.55) | 0.87 (0.62–1.74) | 0.48 | - | - |

| FVC (L) | 3.27 (2.04–5.95) | 3.51 (1.77–6.07) | <.001 | 0.2 (-1.59–1.73) | 6.6 (-50–39.7) |

| FVC % | 104.5 (56–196) | 111.7 (62–157) | <.001 | - | - |

| FEV1 (L) | 2.50 (1.1–4.4) | 2.68 (1.35–4.66) | < .001 | 0.18 (-1.65–1.87) | 6.6 (-64.7–42.6) |

| FEV1 % | 95.5 (62–205) | 106.5 (62–154) | < .001 | - | - |

| Tiffeneau Index | 0.78 (0.48–0.91) | 0.78 (0.65–0.95) | 0.083 | - | - |

| PEF (L) | 6.32 (2.72–13.54) | 6.42 (3.01–11.17) | 0.74 | - | - |

| PEF% | 93.5 (55–141) | 95.6 (49.2–134) | 0.70 | - | - |

| VO2max (L/min) | 1.42 (0.75–2.76) | 1.51 (0.81–2.90) | < .001 | 0.150 (-0.660–0.790) | 8.6 (-31.4–33.8) |

| iVO2 max (ml/kg/min) | 16.8 (10.8–27.6) | 18.6 (12.3–33.9) | < .001 | 1.7 (-6.6–11.1) | 8.8 (-39.8–32.8) |

| AT (ml/kg/min) | 12.83 (± 2.45) | 14.28 (± 2.75) | < .001 | 1.61 (±1.92) | 10.4 (-47.5–39) |

| Peak O2 pulse (ml/min) | 12.0 (6–22) | 13.0 (7–23) | < .001 | 1 (-8–12.5) | 7.6 (-57.1–54.4) |

| Ventilatory reserve (%) | 52.91 (± 12.70) | 50.86 (± 11.78) | 0.19 | -2.06 (±13.24) | -2.06 (±5.4) |

| Age-adjusted PPO (watt) | 137.0 (63–262) | 134.0 (65–262) | 0.01 | 0 (-48–10) | 0 (-27.1–5.5) |

| PPO (watt) | 110.0 (60–224) | 125.0 (75–250) | < .001 | 12 (-29–56) | 8.3 (-19.3–32.7) |

| Relative PPO (watt/Kg) | 1.46 (± 0.39) | 1.61 (± 0.39) | < .001 | 0.16 (± 0.32–0.61) | 0 (-27.1–5.47) |

| HR basal (bpm) | 68.0 (48–98) | 61.0 (46–83) | <.001 | -5 (-29–15) | -7.6 (-49.2–22.4) |

| HR peak (bpm) | 121.5 (± 17.2) | 122.1 (± 16.5) | 0.7 | - | - |

| HR recovery (bpm) | 89.4 (± 15.9) | 83.8 (± 11.3) | <.001 | -5.6 (± 10.1) | -6 (-40.9–20.3) |

| SBP basal (mmHg) | 140.0 (110–160) | 120.0 (105–160) | <.001 | -15 (-55–30) | -12 (-52.4–20) |

| DBP basal (mmHg) | 80.0 (70–110) | 80.0 (60–95) | <.001 | -5 (-35–15) | -5.9 (-50–17.7) |

| SBP peak (mmHg) | 195.0 (150–250) | 190.0 (155–240) | 0.2 | - | - |

| DBP peak (mmHg) | 85.0 (55–110) | 80.0 (60–110) | 0.004 | -5 (-30–30) | -5.9 (-38.5–27.8) |

| SBP recovery (mmHg) | 139.6 (± 13.8) | 129.3 (± 12.0) | <.001 | -10 (-40–25) | -8 (-30.4–17.2) |

| DBP recovery (mmHg) | 80.0 (55–105) | 75.0 (50–95) | <.001 | -5 (-25–15) | -6.7 (-41.7–17.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).