1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) defined as the ability of organisms to evade the effects of antimicrobial agents, has posed a significant global public health threat to the treatment of common infectious diseases [

1]. The net effect of AMR is increased treatment costs through expensive drugs and prolonged hospital stays in addition to rising morbidity and mortality rates [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Further, the most severe impact of AMR is in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where weak health systems that are already overstretched are facing a double tragedy as once treatable conditions are proving difficult to treat [

7,

8,

9]. The hope for a renaissance is placed on antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) programs as a strategy where collective efforts are geared toward appropriate use of antimicrobial agents [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. This is through addressing prescription patterns, preventing infections, and fostering multidisciplinary collaborations to optimize patient outcomes and reduce AMR [

12,

13].

Execution of the AMS in LMICs is a hurdle to consider owing to unique challenges characterized by resource constraints [

16,

17,

18], sparse and fragmented literature, limited surveillance systems, and human capacity [

19,

20,

21]. Additionally, access to essential medicines is often limited but also compounded by high poverty levels that influence the choice of antimicrobials [

22,

23]. Furthermore, the disease burden in LMICs is also high considering the overcrowding, poor sanitation, lack of access to clean water, low literacy levels, limited access to quality healthcare facilities, inadequate diagnostic capacity as well as a low health provider-to-population ratio [

24,

25]. In such settings, the tendency for self-medication, underdosing, and use of unregulated medicinal and herbal agents are rampant in addition to reliance on cultural and superstitious connotations to health [

26,

27]. Additionally, there is a huge concern among most LMIC on the risk of hospital-acquired infections. Hence, AMS programs in LMICs require an innovative broad-based approach that incorporates appropriate measures to the existing contextual challenges [

27,

28].

A review of AMS interventions applied in LMICs demonstrates multifaceted actions such as education, training, guideline development, multidisciplinary case-based approach, and policy advocacy among others are effective to combat AMR [

29,

30,

31]. The training and education approach aims to improve awareness among the public and healthcare workers on the importance of rational and appropriate antimicrobial use in addition to the simple but impactful actions that can be taken to derail the AMR pandemic [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Public campaigns through seminars, conferences, and media engagements among other advocacy measures are meant to mobilize civil society, policymakers, and health stakeholders for a common resolve to support AMS initiatives [

36]. Healthcare professionals are particularly targeted for in-service training [

30,

37,

38,

39]. The training empowers them with evidence-based patient safety, infection prevention and AMS guidelines to foster a culture of responsible antimicrobial use in the healthcare settings [

40,

41]. For example, the use of WHO Access, Watch, and Reserve (AWaRe) classification of antibiotics is targeted to health providers [

42]. The AWaRe classification of antibiotics was established by the WHO to optimize antibiotic use and monitor the success of implementation of AMS programs to address inappropriate prescribing [

43,

44,

45].

The other approach involves the development and dissemination of AMS policy guidelines where local and external experts combine efforts to provide evidence-based guidelines that suit the local contextual needs, the prevailing epidemiology and antimicrobial agents, resources, and capacity of healthcare systems in LMICs [

36]. The guidelines promote a standardized approach to AMS to leverage consensus implementation and monitoring that matches the resource constraints [

46]. Additionally, another critical strategy to combat AMR is the establishment of multidisciplinary AMS teams at the national, sub-national, and facility levels comprising of infectious disease specialists, microbiologists, nurses, clinical pharmacists, medical officers, healthcare leaders, and other professionals [

29,

47,

48,

49]. The teams have diverse roles depending on their establishment level, but those at the facilities are meant to synthesize national guidelines into simple actionable items for their facilities to monitor disease and AMR trends, share findings. The facility AMS teams also provide support real time interventions to the clinical teams [

31,

50,

51]. Moreover, AMS program at the service point, informs the decision to de-escalate antimicrobials, dose optimization, and duration of antimicrobials to minimize exposure and reduce risk of AMR. Notable AMS comprehensive strategies among LMICs are exemplified by South Africa’s AMR national strategic plan [

52], and in similar documents from other countries [

50,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57].

The impact of AMS interventions in LMICs has been progressive, but the evidence is limited. Process outcomes such as change in knowledge and practices regarding antimicrobial use are notable [

34,

51,

58,

59]. Guidelines restricting prescription or sale of particular antimicrobials are effective in some countries [

60]. Multifaceted interventions improved prescribing patterns and use of antibiotics [

61,

62]. In Kenya, execution of AMS guidelines led to decreased proportion of patients operated without appropriate prophylaxis [

63] while in South Africa and Ghana, introduction of clinical pharmacist experts introduced discipled use of antibiotics [

31,

64]. Consequently, it is not easy to establish reduction of AMR rates due to limited longitudinal studies in LMICs though some reports have indicated a decrease in Surgical Site Infections (SSIs) [

64,

65].

Besides, there is need to improve coordination across facilities as fragmentation of health services across tiers of government and service providers are challenging to the implementation of uniform AMS programs. Other variable lessons gained include the findings that multifaceted approach is critical in LMICs where interventions are not only tailored to suit the needs of specific countries but also broad enough to meet the requirements within the broader integrated healthcare system [

66]. Moreover, interdisciplinary collaborations have fostered shared responsibility but wider stakeholder engagements are crucial to maintaining the moment gained so far [

67]. Further multi-country evaluation strategies would be ideal to compare implementation approaches, process, and outcome measures [

68].

Therefore, in this study, we evaluated the pre- and post-program implementation of AMS Programs across five African countries based on the modified WHO Periodic National and Healthcare Facility Assessment Tool.

2. Results

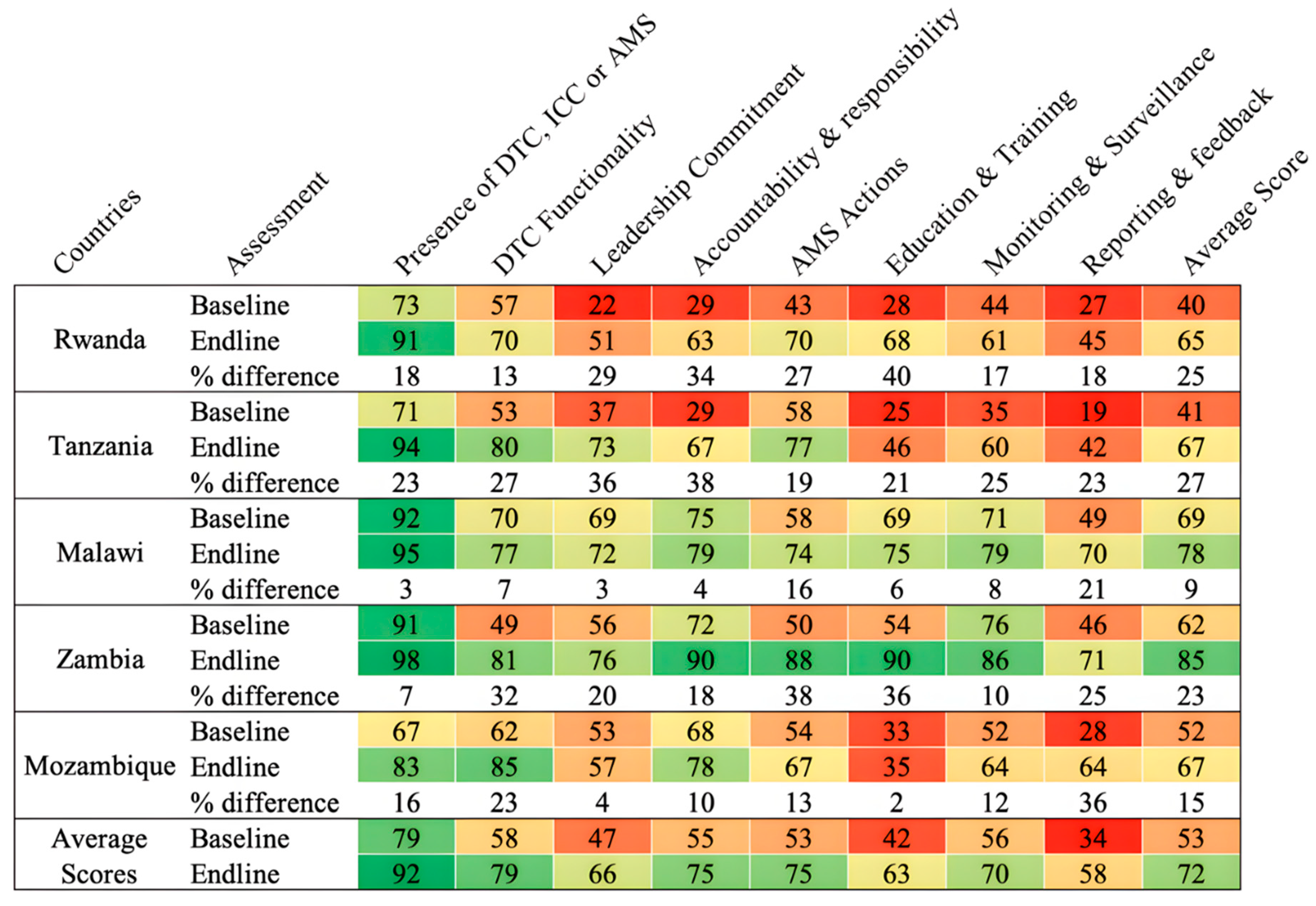

The countries’ readiness to implement AMS programs was assessed based on the modified WHO AMS Periodic assessment tool which included the following AMS core elements: Drugs and Therapeutics Committees (DTC), Infection Control Committees (ICC) or Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS) Committees; leadership commitment; accountability and responsibility; AMS actions; education and training; monitoring and surveillance; reporting and feedback (

Figure 4).

The average scores across the core elements for the assessed hospitals ranged from 34% to 79% and 63% to 92% for baseline and end-line assessments, respectively. The baseline assessment averages showed low performance in leadership and commitment (47%), education and training (42%), reporting and feedback (34%) for all five countries. On average, improvement was notable in DTC functionality (21%), Accountability and responsibility (20%), AMS Actions (22%), Education and training (26%), and Reporting and Feedback (24%). None of the assessed countries reported having a fully functional AMS program when assessed across all the core elements (

Figure 1).

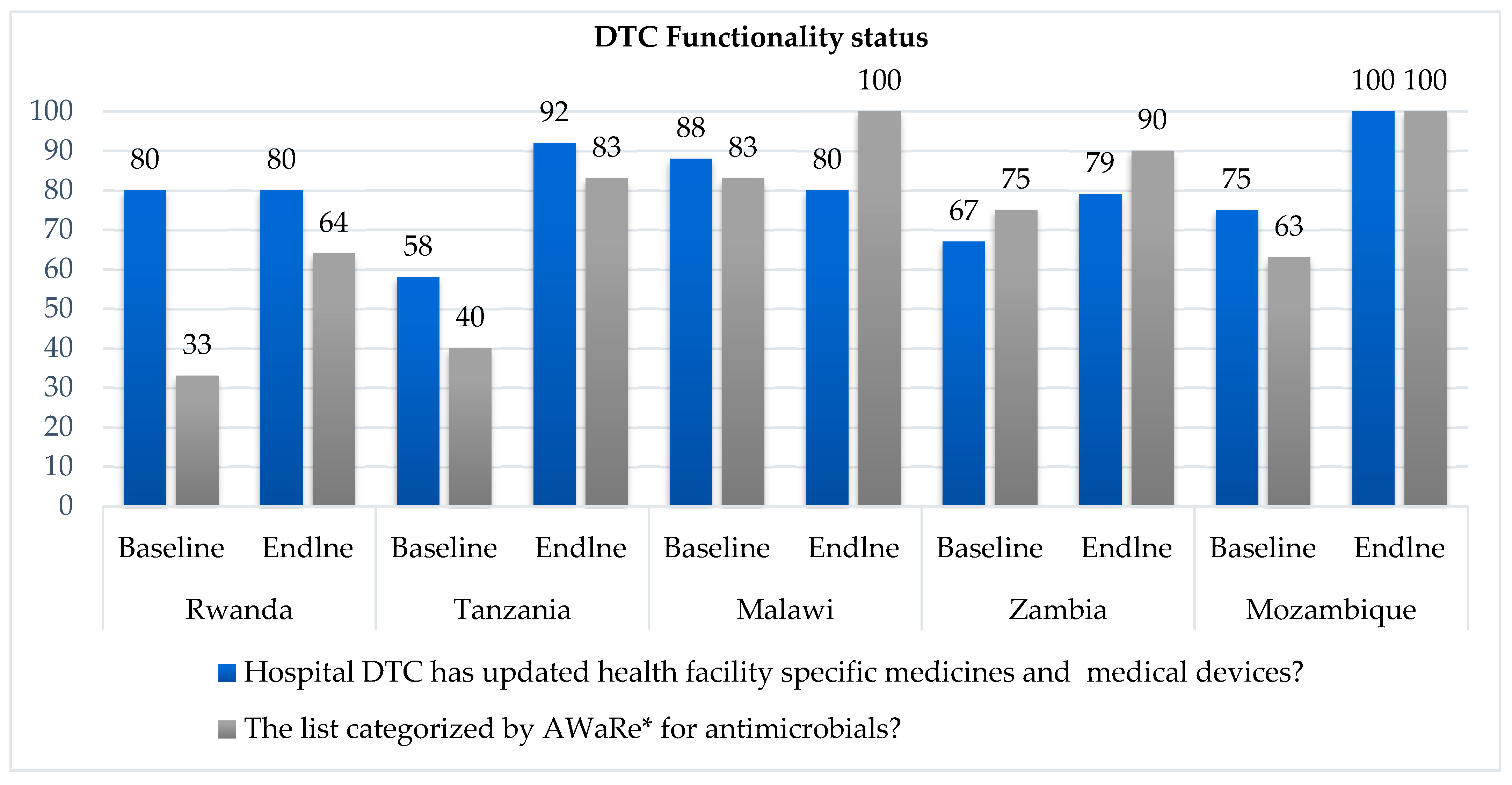

Functionality of the Drugs and Therapeutics Committees in Surveyed Hospitals.

All hospitals across the five countries had DTCs, AMS and ICC committees in place at the end of the implementation period. However, in assessing the functionality of the DTCs, not all hospitals assessed had updated the medicines and medical devices list or classified their antimicrobials by the WHO AWaRe categorization as shown in

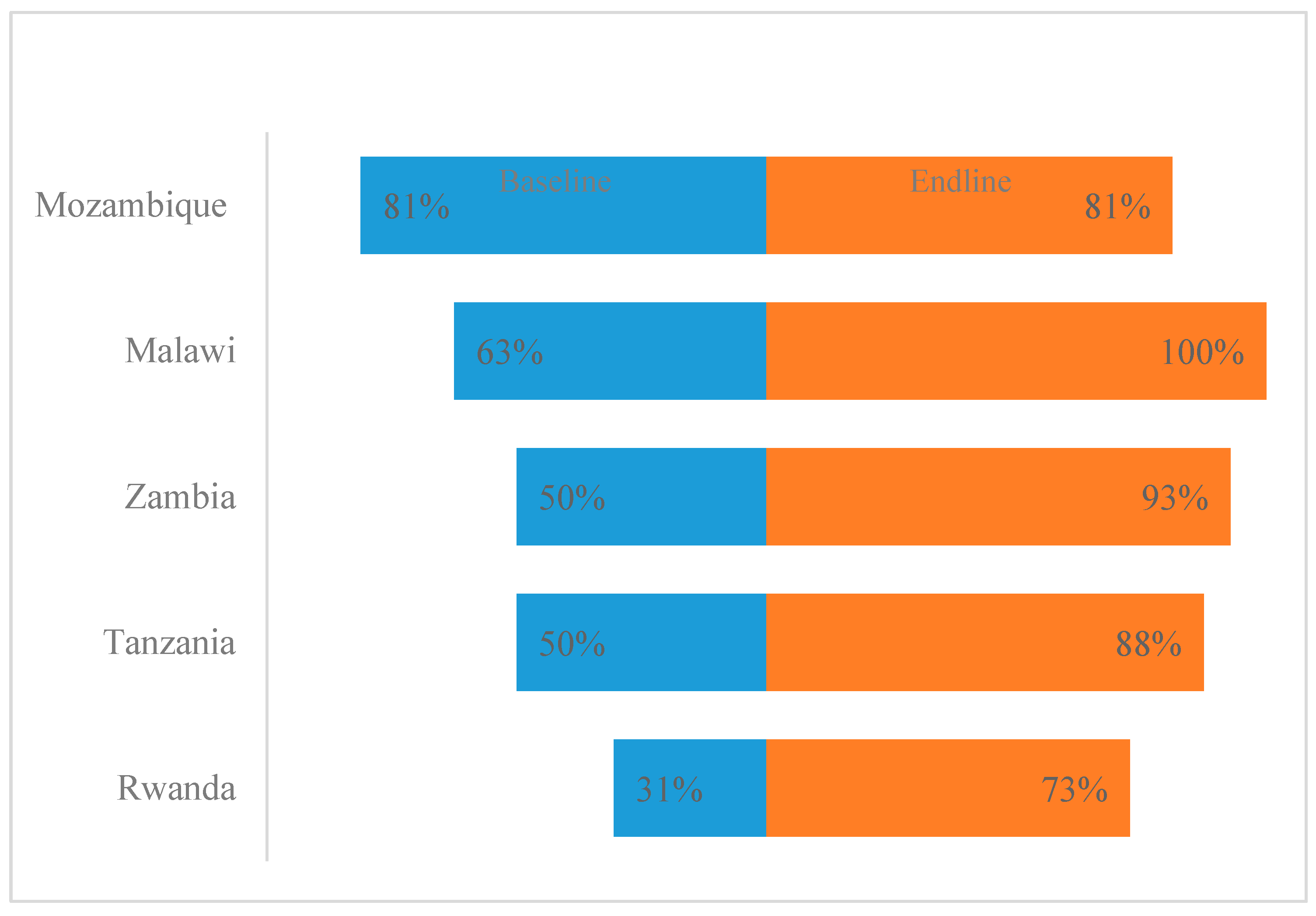

Figure 2. All five countries recorded an improvement in DTC functionality from baseline to endline of the study (

Figure 2).

Leadership commitment to support AMS programs in the surveyed hospitals

AMS was identified as a priority by hospital management/leadership in all countries with an average baseline score of 47% and 66% at end line. The average score for AMS activities being included in the facility annual action plan was 49% at baseline and 68% at end line with scores ranging from 25% to 81% and 55% to 81% at baseline and end line respectively. This study found that the average scores on the presence of a mechanism to regularly monitor and measure the implementation of AMS activities was 57% at baseline and 69% at the end line. An average score of 19% and 43% was recorded at the start and end of the implementation period with regards to dedicated financial support for the AMS action plans. Country scores on financing the plans ranged from 8% to 33% at baseline and 13% to 64% at end line.

Accountability and responsibility in surveyed hospitals

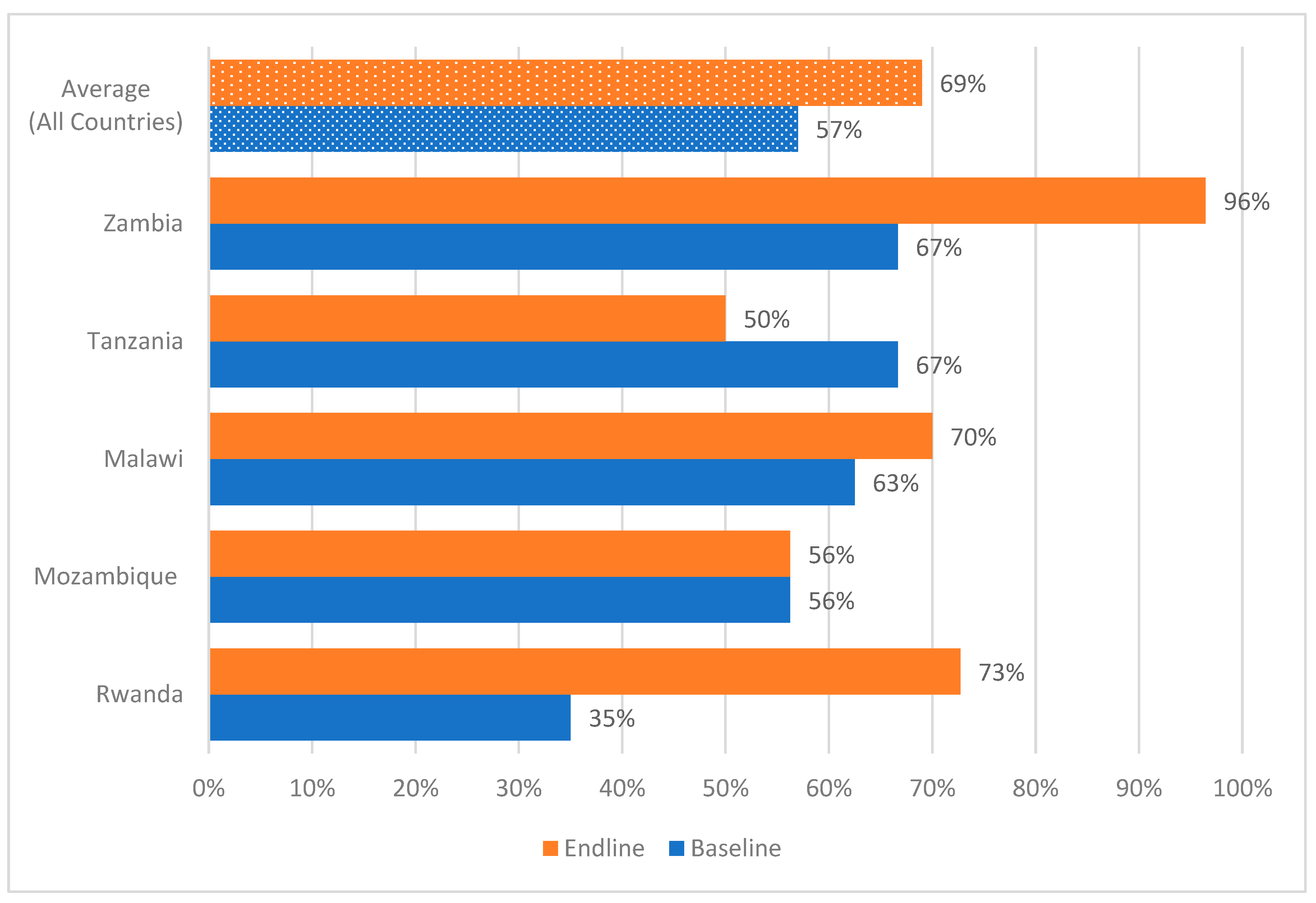

At the end of the implementation period, all the five countries reported having multidisciplinary AMS committees with clear terms of reference (TOR) operating at various levels from partially to fully implemented in all assessed hospitals. Four countries reported an improvedment in the AMS committees except Mozambique (

Figure 3). However, not all AMS committees reported meeting on a regular basis.

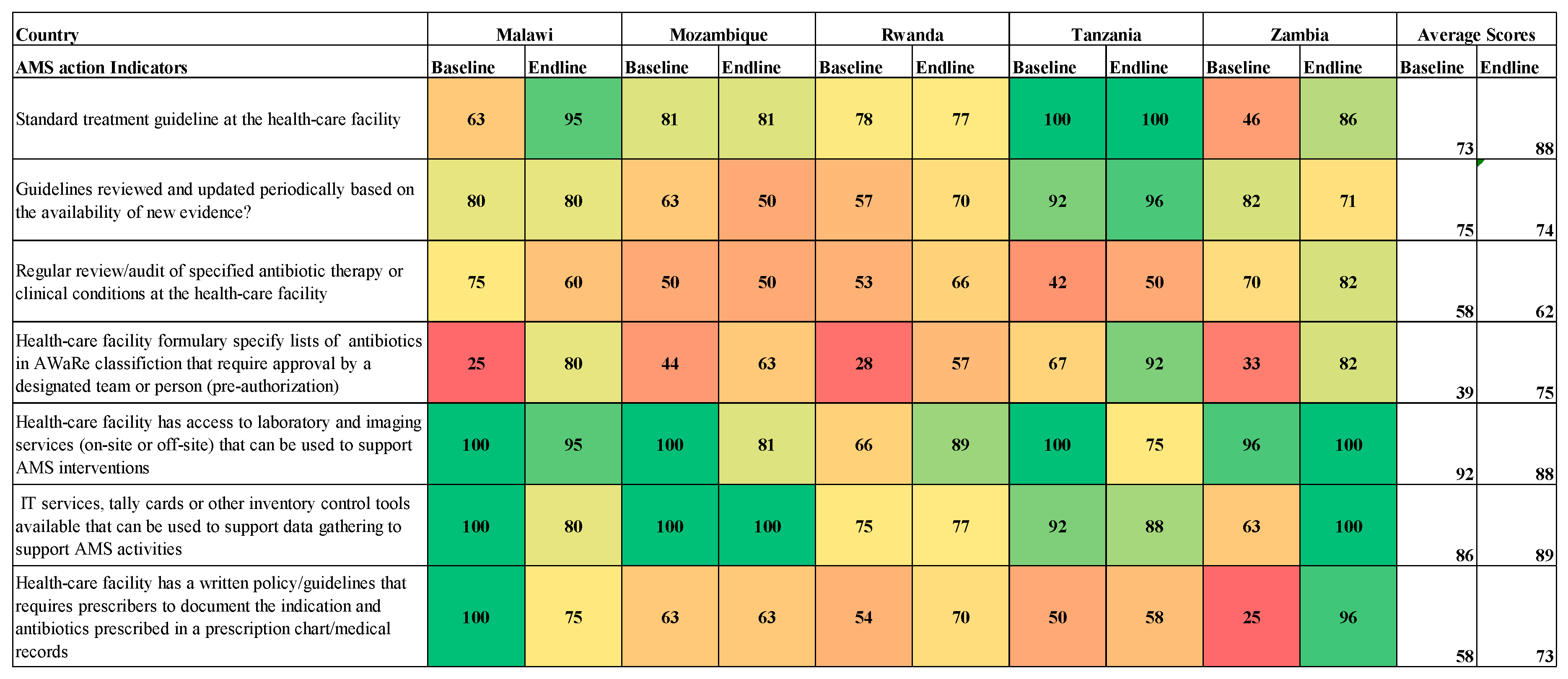

AMS actions in the surveyed hospitals

Eighty percent of the hospitals assessed reported having STGs during the end-line assessment recording a 14% increase from the baseline. However, there was no improvement reported on the review of guidelines based on evidence. On pre-authorization of antibiotics based on the AWaRe classification, baseline scores ranged from 25% to 67%, while end-line scores ranged from 57% to 92% across the countries (

Figure 4). There was a decrease in the percentage of facilities reporting having access to laboratory and imaging services to support AMS interventions. Eighty percent of the hospitals reported having IT services, tally cards, or other inventory control tools available that can be used for data gathering to support AMS activities. At the end of the implementation period, no improvement was noticed in hospitals having a written policy/guidelines that required prescribers to document the indication and antibiotics prescribed when compared to the baseline (

Figure 4).

Figure 4.

AMS actions across the surveyed hospitals.

Figure 4.

AMS actions across the surveyed hospitals.

Education and Training of healthcare workers in the surveyed hospitals

On average, 56% of assessed hospitals had included education programs such as optimizing antibiotic use, prescribing, dispensing, and administration of antibiotics in their staff induction training, and 20% reported offering continuous in-service training, or continuous professional development on AMS, infection prevention, and control (IPC) to hospital staff as at the end of the implementation period (

Figure 5).

Monitoring and Surveillance of antimicrobial use and AMR in surveyed hospitals

The assessment revealed that the hospital capacities for regular prescription audits, and point prevalence surveys to assess the appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing were below 75% at the beginning and end of the implementation period.

At the end of the implementation period, 68% of the health facilities assessed reported regularly monitoring the quantity and types of antibiotics used; 83% regularly monitored shortages/stock-outs of essential antimicrobials; 57% had a mechanism to report substandard and falsified medicines and diagnostics. With respect to regularly monitoring antibiotic susceptibility and resistance rates, only 63% had reported the capacity to perform AST for a range of key indicator bacteria at the end line compared to 52% at the baseline.

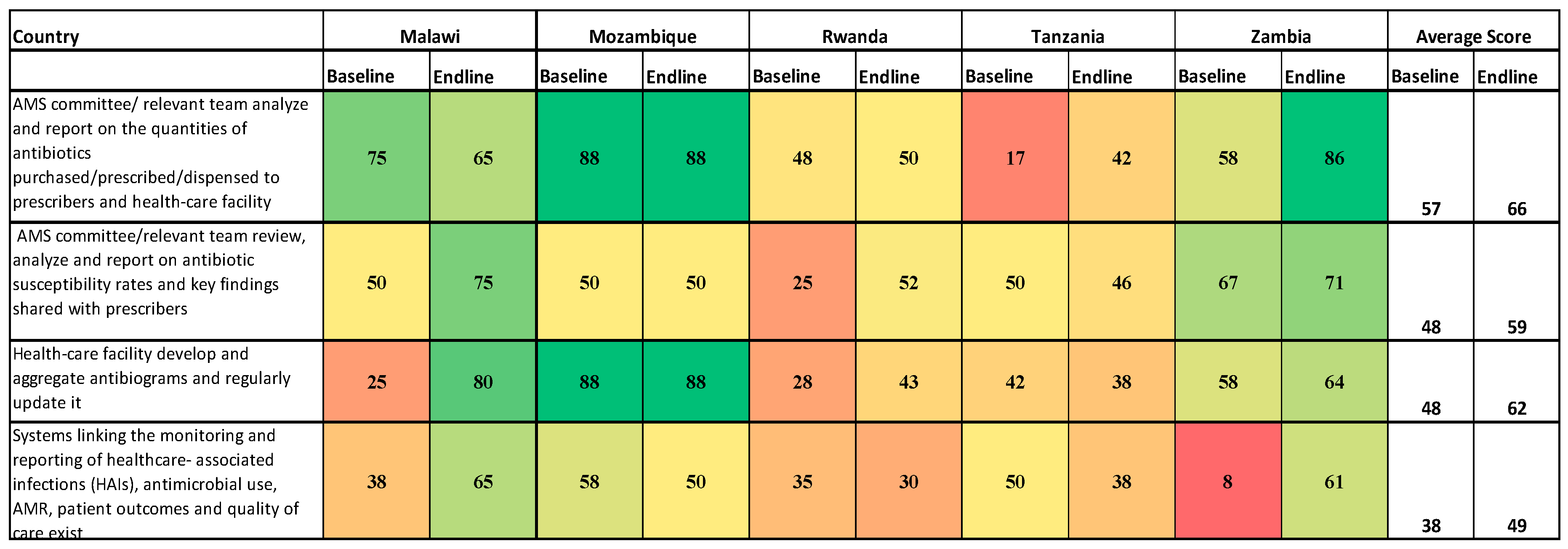

Reporting feedback within the healthcare facility

Concerning AMS committees analyzing and reporting on quantities of antibiotics purchased or prescribed, the scores were 17% to 88% at baseline while end-line scores ranged from 42% to 88% (

Figure 6). At the end of the implementation period, 62% of the assessed hospitals had the capacity to develop, aggregate, and regularly update antibiograms compared to 48% at the baseline. Low scores were recorded with respect to linking the reported healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), antimicrobial use; AMR, patient outcomes, and quality of care (baseline scores of 8% to 58% and end-line of 30% to 65%).

3. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that utilized a regional approach to strengthening the implementation of sustainable AMS programs in five countries in East, Central, and Southern Africa.

In this study, the core elements of AMS had suboptimal scores at baseline but scored high at endline, and this was contrary to suboptimal performance across all the core elements of AMS in hospitals in a study done in Ghana [

69]. Our study further found that all the hospitals had DTCs, but scores were low at baseline and improved at the endline stage after implementation of interventions. The presence of DTCs in studies conducted elsewhere showed remarkable differences across countries, for example, low functionality of DTC was shown in Zambia, whereas lack of AMS programs was reported in some selected facilities in Nigeria [

14,

70]. A study in Nigeria found that hospitals had DTCs but lacked AMS and IPC committees [

70], and it is well known that facilities that lack AMS committees tend to fail to implement AMS programs [

48]. IPC committees are important to establish and implement IPC core elements and measures in hospitals [

71,

72,

73,

74].

Our study found low leadership commitment, accountability, and responsibility at the baseline stage, which also improved at endline stage after interventions. These core elements foster a sense of responsibility among healthcare professionals for ensuring adherence to antimicrobial prescribing guidelines and minimizing the development of AMR. Evidence has shown that leadership is responsible for operating AMS programs by providing and prioritizing resources needed for AMS activities [

75]. Strong leadership engagement is critical to the effective implementation of AMS programs in hospitals [

41].

The present study revealed that AMS actions in the surveyed hospitals improved after interventions with hospitals reporting a 14% increase in having STGs, improvement in implementing the WHO AWaRe classification of antibiotics, and having guidelines that required prescribers to document the indication and antibiotics prescribed in a prescription at health facilities. These reported improvements reveal the significance of implementing AMS programs in hospitals to promote the rational use of antimicrobials, including fostering conformity to the WHO AWaRe classification of antibiotics [

76,

77]. Despite variations in the scores across countries, our findings indicate an improvement in AMS actions from baseline to endline of the survey. This reiterates the need for continuous strengthening of AMS teams beyond their establishment.

In this study, education and training of healthcare workers regarding AMS was low during the baseline survey and improved at endline. Studies have demonstrated that education is an important component of AMS interventions and promotes the rational prescribing and use of antimicrobials [

32,

33,

75,

78,

79]. Education and training using the WHO health workers’ training curriculum and framework is critical in improving awareness and knowledge of AMR leading to the optimization of antimicrobial use [

30,

39]. Further, instigation of training in healthcare facilities is very essential to improve awareness and understanding of AMR among healthcare workers [

80,

81]. Educational programs for new healthcare workers should include optimization of antimicrobial use, prescribing, dispensing, and administration [

30,

39]. Furthermore, hospital staff must enrol in continuing professional development education concerning AMR, AMS, and IPC [

30].

The performance in the two core elements of monitoring and surveillance, accountability, and responsibilities recorded improvement across all five countries at the end of the implementation period. One country reported full implementation for both core elements while the other four countries demonstrated that both core AMS interventions were partially implemented and needed attention for strengthening. The performance on accountability and responsibility could possibly be attributed to the inclusion of AMS activities in hospital plans, the establishment of AMS committees with terms of reference (ToRs), and the existence of dedicated champions for AMS activities in most of the assessed hospitals. Although most of the assessed hospitals in these countries had costed action plans, there was no dedicated financial support for AMS interventions. For sustainable implementation of AMS programs, there is a need to provide financial support for AMS activities in hospitals [

14,

42,

69,

82]. This was in line with other reports which indicated that despite many countries having the NAPs in place, very few succeeded to the implementation stage due to inadequate funding for the activities [

83]. Furthermore, variations can also be associated with the enrolment of hospitals in some countries that had no pre-existing structured AMS programs compared to others which already had pre-existing AMS programs. Lastly, the level of hospitals (secondary versus tertiary) can also account for the variations in the AMS performance obtained across countries.

None of the assessed countries reported full implementation of the reporting and feedback indicator, showing that reporting and feedback is still a challenge that requires prioritization in the implementation of AMS programs. Indeed, reporting and feedback is a pivotal component in the quality improvement cycle as it provides critical strengths and gaps to guide focused/specific AMS interventions within and across hospitals.

The implementation status of AMS programs in five countries varied. While the countries have made progress in establishing and implementing AMS programs, there are significant challenges in fully operationalizing the programs. Lack of human and financial resources, AMS education and training, antibiograms, and inadequate enforcement of regulations to promote rational antibiotic prescriptions remain huge barriers to implementing and achieving AMS activities and goals [

41,

84]. It should be reiterated that antibiograms are useful in fostering appropriate empiric treatment of infections in hospitals [

85]. However, unreliable or a lack of antibiograms is a hindrance to the effective implementation of AMS [

86]. The DTCs provide an opportunity for a strong and sustainable foundation for the implementation of AMS programs within and across countries, by fostering (among other AMS interventions) the generation and utilization of antibiograms to guide rational antimicrobial prescriptions.

Study limitations

Since the study was conducted across five countries, the practices and resources in these hospitals may differ and could affect the findings. Therefore, generalization to all African countries should be made cautiously. Due to funding and time limitations, the potential impact of using this model on patient outcomes, behavior change, and rational use of antimicrobials could not be determined. Additionally, staff attrition in hospitals during the implementation period may have an impact on feedback during the end-line survey. Furthermore, multicounty evaluation strategies and studies would be ideal to compare implementation approaches, processes, and outcome measures. However, the study highlights the importance of instigating AMS programs to combat AMR as evidenced by the improved scores after AMS interventions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study design and site selection

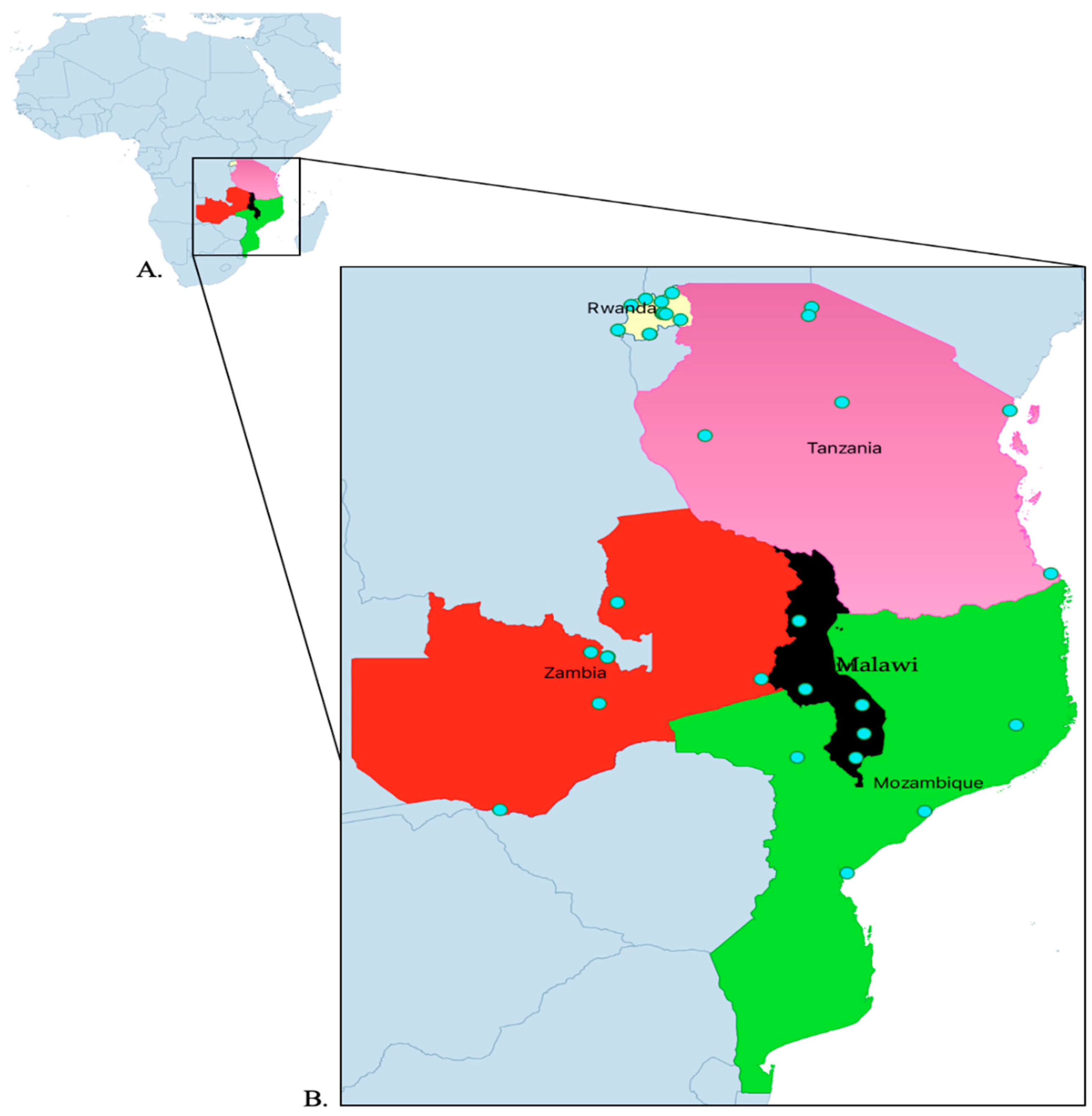

Exploratory cross-sectional studies were done at the beginning and the end of the project in five countries across 32 hospitals. The countries included Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda Tanzania, and Zambia. The included hospitals were five from Malawi, four from Mozambique, eleven from Rwanda, and six from Tanzania, and Zambia (

Table 1 and

Figure 7). The aim of the project was to strengthen AMS programs in the five countries under the World Bank Funded Strengthening Pandemic Preparedness Project. The project ran from February 2022 to December 2023. The WHO, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and ECSA-HC have recommended Core Elements for Antimicrobial Stewardship to support the establishment and implementation of effective AMS programs [

87,

88]. The guidance documents further outline structural and procedural components, competencies, and resources that are associated with successful AMS programs.

The targeted countries were part of the Strengthening Pandemic Preparedness Project. The individual countries through their Antimicrobial Resistance Coordinating Committees (AMRCC) were engaged to select the hospitals that were involved in the project. All the countries purposively considered hospitals that had basic microbiological capacities to support AMR surveillance which included secondary and tertiary-level hospitals.

4.2. The Approach

Countries developed national guidelines adapting from global and regional guidance as well as accompanying training packages on establishing AMS programs in health care settings with subsequent identification of participating hospitals. Selected hospitals were requested to establish AMS committees with clear terms of reference and invited to develop the action plans on how they intended to implement AMS activities . This was to tailor interventions based on country and health care facility contexts. Hence, some of the activities involved the conducting of the baseline and end line surveys. The baseline survey was to assess the initial capacity to better understand the needs and priorities of AMS and guide the development of action plans. While the end line survey was to review the impact of the activities that were implemented on AMS.

4.3. Data collection tool

Though there are several tools in countries to assess AMS activities, the countries agreed and selected the validated adapted Periodic National and Healthcare Facility Assessment Tool in the WHO policy guidance on integrated AMS activities in human health [

14,

37]. The tool was modified to capture the necessary components for AMS implementation.

Using the modified validated Periodic National and Healthcare Facility Assessment Tool in the WHO policy guidance on integrated AMS activities in human health [

37], countries conducted baseline assessments and developed implementation plans based on the findings. They then proceeded with the implementation of the activities and monitored their progress through and at project completion. Six WHO AMS core elements and an additional core element on drugs and therapeutic committees were assessed. Each core element had several components of assessment or indicators. These included General (presence of DTC, IPC, and AMS teams), DTC functionality, Leadership commitment, accountability and responsibility, AMS Actions, Education and Training, Monitoring and surveillance, and Reporting Feedback within the Hospitals. However, under each core element, the countries agreed on selected indicators that they considered to be key for monitoring (Supplementary material 1).

4.4. Baseline Assessment

The face-to-face interviews were conducted by four data collectors per hospital and the information was verified from existing sources and records in the hospitals. The data collectors were trained on how to collect data and enter it into the assessment tool. The data collectors or assessors were members of the AMRCC in their respective countries. During this process, ECSA-HC and other experts from the selected countries provided technical assistance and guidance to the AMRCCs. The data collected was entered into tablets and computers, with access strictly limited to authorized personnel. The data collected during this phase was used as a reference point for comparison with post-intervention data (

Figure 2).

4.5. Implementation of the project

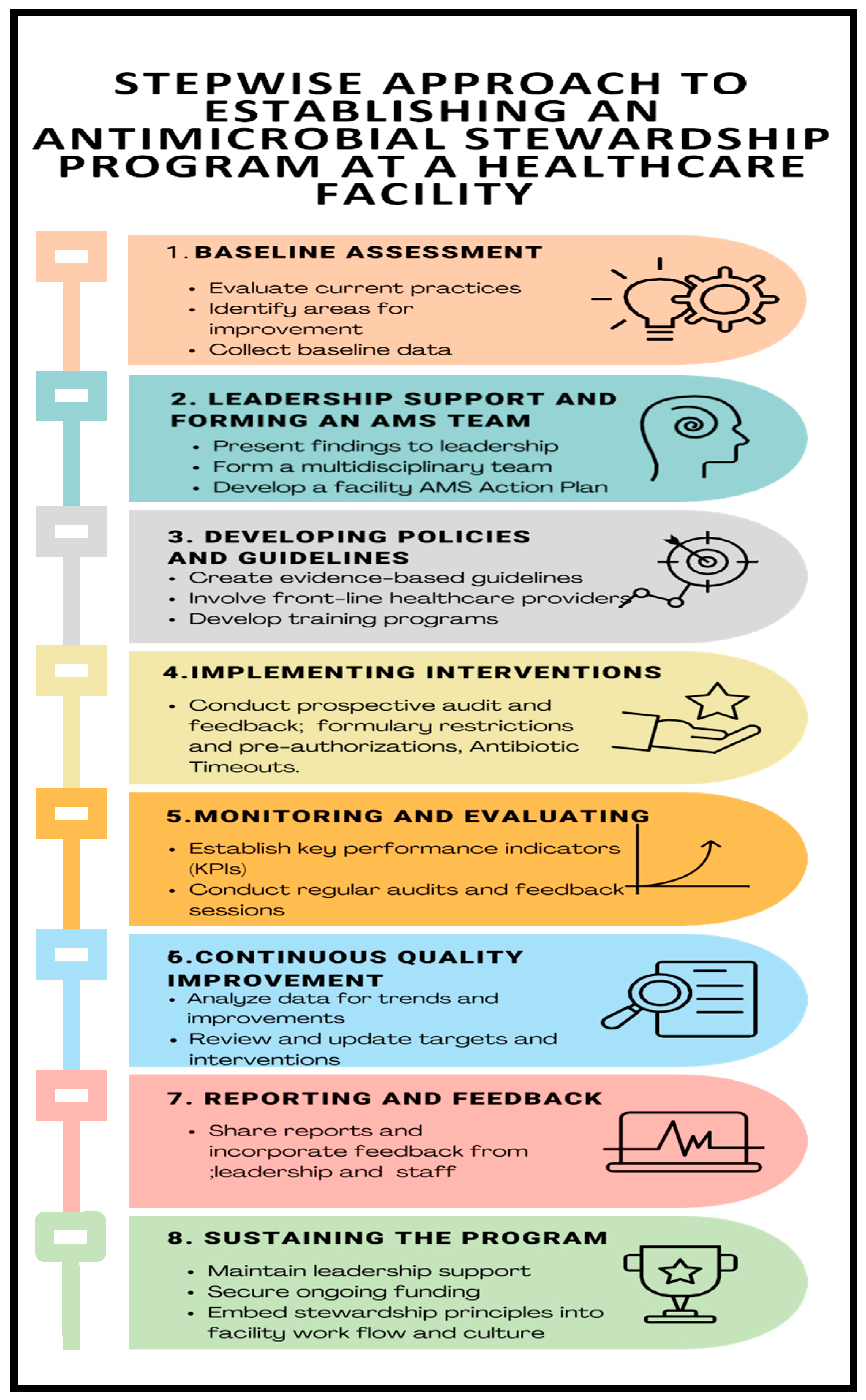

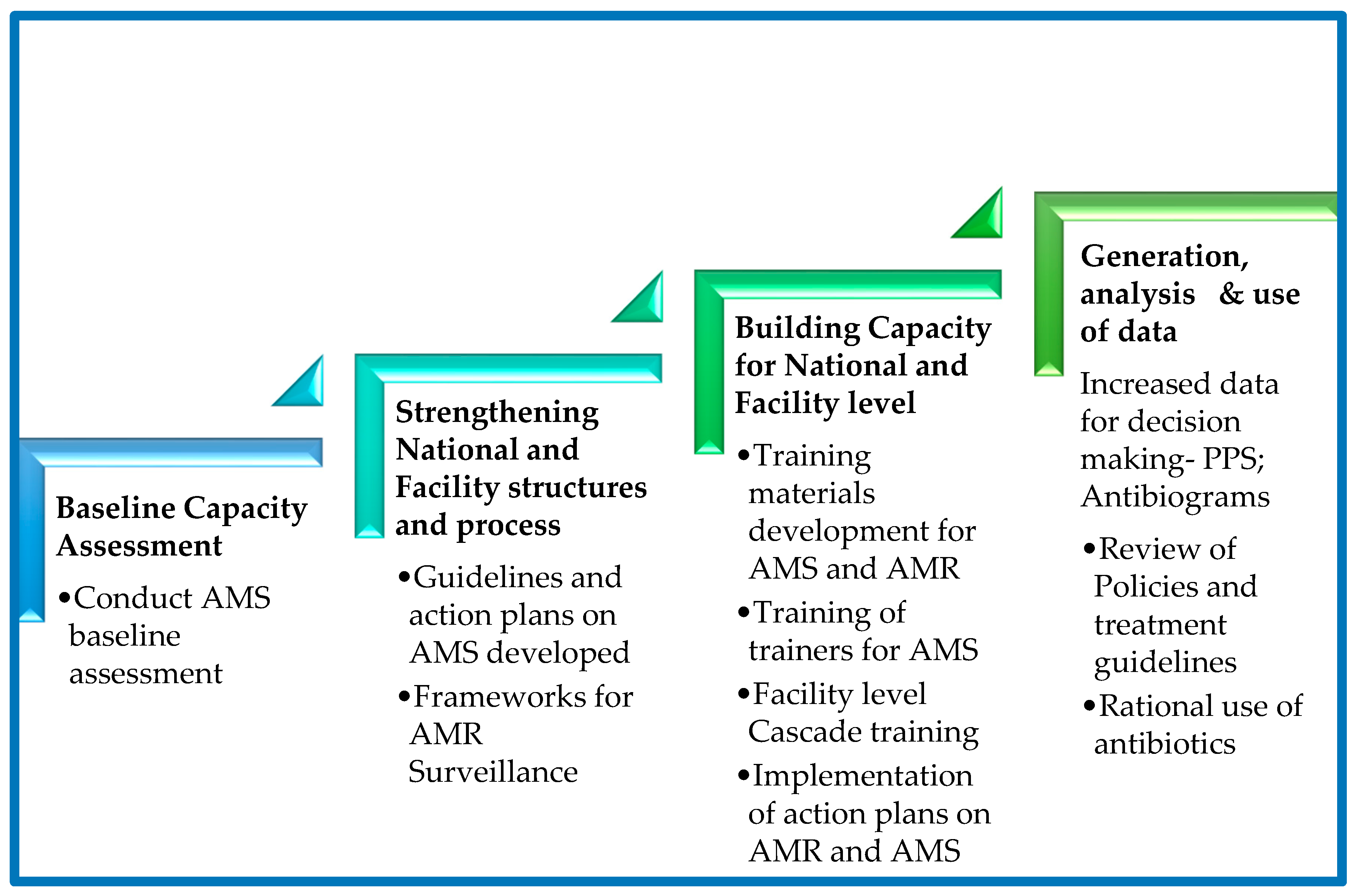

After the gap analysis was conducted at the hospital levels in the project countries, context-specific and tailored action plans were developed to address the gaps. For sustainable capacity building a regional peer-to-peer model was embedded in the capacity building process to facilitate, benchmarking, peer-to-peer (country-to-country/site-to-site) learning based on the level of the existing capacity or capability for the different core elements in AMS. The implementation process adopted a stepwise approach (

Figure 7) to support the five project countries build their capacities for antimicrobial stewardship programs in the selected facilities. The activities involved document development such as AMS guidelines and training manuals, treatment guidelines, local antibiograms, and classification of antibiotics according to WHO AWaRe. Other activities included orientation of the hospital leadership orientation in AMS, training of health workers in AMS/AMR, conducting point prevalence surveys, antibiotic prescription audits, analysis, and use of locally generated data for the review of action plans and decision making. Throughout the implementation phase, a regional approach was followed by the implementing team led by country AMRCC members. The teams monitored the process to ensure interventions were implemented as planned. Peer-to-peer cross-country learning and experience sharing by regional experts for the participating countries was adopted for lesson learning throughout the implementation period. The Stepwise process adopted is summarized in the

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

4.6. Post-Intervention Data Collection (Endline Assessment)

Following the implementation of the interventions identified, post-intervention data was collected using similar methods and tools employed during the baseline data collection phase. The data captured the changes resulting from the interventions and provided a basis for evaluating the effectiveness of the regional approaches employed.

Figure 9.

Stepwise Approach to establishing an Antimicrobial Stewardship Program at a Health Care Facility.

Figure 9.

Stepwise Approach to establishing an Antimicrobial Stewardship Program at a Health Care Facility.

4.7. Data Analysis

The information collected was entered into the Microsoft Excel WHO self-scoring assessment tool. The tool then generated a summarized score based on the eight core elements of the survey. Subsequently, all the responses were grouped into eight themes under each core element. Following this, thematic analysis was conducted to analyze all the responses thoroughly.

The answers were ranked from 0 to 4, where 0 meant "No," 1 meant "No, but a priority," 2 meant "Planned but not started," 3 meant "Partially implemented," and 4 meant "Yes (Fully implemented)." When the total AMS score fell between 0.0 and 49.9%, it meant that the AMS program was either non-functional or operating poorly and that it needed to be given priority care. A score of 50–79.9% meant that the AMS program was only partially operational and required support to be strengthened. Whereas a score between 80 and 100%, meant that the AMS program was fully established and operating as intended, but it still needed ongoing assistance to be sustainable [

14,

37].

5. Conclusion

This study found suboptimal performance of all hospitals in the surveyed countries regarding the core elements of AMS during the baseline phase. However, there was an improvement in the performance of hospitals across all core elements of AMS after interventions were instigated. The selected countries made efforts to establish AMS programs by implementing national AMS programs that included the development of national guidelines, education, and training approaches for healthcare workers through a step-wise approach implementation of AMS programs. These programs required a stepwise approach and flexibility due to the complexity of medical decision-making surrounding antibiotic use, diversity of health care system capacities and the variability in the size and types of care. Overall strengthening of health systems is required for the successful implementation of the AMS programs. Collaboration between countries and international organizations can facilitate the development and implementation of effective AMS programs in sub-Saharan Africa. This is by providing sustainable regional networks, development of context-specific regional and national guidance documents, utilization of regional resources and partnerships to enhance north-to-north lesson learning and sharing platforms for better health outcomes for patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.W. and M.M.; methodology, E.W, J.Y.C, and S.M.; software, J.Y.C, J.S; validation, K.Y., N.M, C.M., A.N, and M.G.; formal analysis, E.W, S.M, J.Y.C, E.M .; investigation, E.W, S.M, Si.M, J.S, C.M, K.Y, M.G, A.N, N.M.; resources, E.W, M.M.; data curation, H.K, E.F.; writing—original draft preparation, E.W, J.Y.C, S.M, J.S, Si.M, C.M, K.Y, E.F, A.N, N.M, M.G and H.K.; writing—review and editing, E.W, J.Y.C, S.M, Si.M, J.S, C.M, K.Y, E.F, N.M, M.G and H.K.; visualization, E.W, E.F, N.M, M.M, J.Y.C, S.M, A.N, Si.M, J.S; supervision, E.W, H.K, M.M.; project administration, E.W, M.M.; funding acquisition, E.W, and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the World Bank under the Strengthening Pandemic Preparedness Project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require ethical approval.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the Ministries of Health and National Antimicrobial Resistance Coordinating Committees for the governments of Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Zambia. We acknowledge financial support from the World Bank Strengthening Pandemic Preparedness Project, through the East Central and Southern Africa Health Community.

Transparency declarations

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to declare. All the authors do not have any financial interests or connections that may directly or indirectly raise concerns of bias in the work reported or the conclusions, implications or opinions made in this publication.

References

- EClinicalMedicine Antimicrobial Resistance: A Top Ten Global Public Health Threat. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 41, 101221. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Antimicrobial Resistance 2023.

- Dadgostar, P. Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications and Costs. Infect Drug Resist 2019, 12, 3903–3910.

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. The Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [CrossRef]

- Naghavi, M.; Emil Vollset, S.; Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Gray, A.P.; Wool, E.E.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Mestrovic, T.; Smith, G.; Han, C.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis with Forecasts to 2050. The Lancet 2024, 0. [CrossRef]

- Salam, Md.A.; Al-Amin, Md.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance; 2016;

- Godman, B.; Egwuenu, A.; Wesangula, E.; Schellack, N.; Kalungia, A.C.; Tiroyakgosi, C.; Kgatlwane, J.; Mwita, J.C.; Patrick, O.; Niba, L.L.; et al. Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance across Sub-Saharan Africa: Current Challenges and Implications for the Future. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2022, 21, 1089–1111. [CrossRef]

- Sartorius, B.; Gray, A.P.; Davis Weaver, N.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Ikuta, K.S.; Mestrovic, T.; Chung, E.; Wool, E.E.; Han, C.; et al. The Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in the WHO African Region in 2019: A Cross-Country Systematic Analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2024, 12, e201–e216. [CrossRef]

- Mudenda, S.; Chabalenge, B.; Daka, V.; Mfune, R.L.; Salachi, K.I.; Mohamed, S.; Mufwambi, W.; Kasanga, M.; Matafwali, S.K. Global Strategies to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance: A One Health Perspective. Pharmacol Pharm 2023, 14, 271–328. [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, M.; Morris, A.M.; Thursky, K.; Pulcini, C. How to Start an Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme in a Hospital. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2020, 26, 447–453.

- Majumder, M.A.A.; Rahman, S.; Cohall, D.; Bharatha, A.; Singh, K.; Haque, M.; Gittens-St Hilaire, M. Antimicrobial Stewardship: Fighting Antimicrobial Resistance and Protecting Global Public Health. Infect Drug Resist 2020, 13, 4713–4738. [CrossRef]

- Dyar, O.J.; Huttner, B.; Schouten, J.; Pulcini, C. What Is Antimicrobial Stewardship? Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2017, 23, 793–798.

- Chizimu, J.Y.; Mudenda, S.; Yamba, K.; Lukwesa, C.; Chanda, R.; Nakazwe, R.; Simunyola, B.; Shawa, M.; Kalungia, A.C.; Chanda, D.; et al. Antimicrobial Stewardship Situation Analysis in Selected Hospitals in Zambia: Findings and Implications from a National Survey. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1367703. [CrossRef]

- Chizimu, J.Y.; Mudenda, S.; Yamba, K.; Lukwesa, C.; Chanda, R.; Nakazwe, R.; Shawa, M.; Chambaro, H.; Kamboyi, H.K.; Kalungia, A.C.; et al. Antibiotic Use and Adherence to the WHO AWaRe Guidelines across 16 Hospitals in Zambia: A Point Prevalence Survey. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2024, 6, dlae170. [CrossRef]

- Ashley, E.A.; Shetty, N.; Patel, J.; Van Doorn, R.; Limmathurotsakul, D.; Feasey, N.A.; Okeke, I.N.; Peacock, S.J. Harnessing Alternative Sources of Antimicrobial Resistance Data to Support Surveillance in Low-Resource Settings. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2019, 74, 541–546. [CrossRef]

- Rousham, E.K.; Unicomb, L.; Islam, M.A. Human, Animal and Environmental Contributors to Antibiotic Resistance in Low-Resource Settings: Integrating Behavioural, Epidemiological and One Health Approaches. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2018, 285, 20180332.

- Nadimpalli, M.; Delarocque-Astagneau, E.; Love, D.C.; Price, L.B.; Huynh, B.T.; Collard, J.M.; Lay, K.S.; Borand, L.; Ndir, A.; Walsh, T.R.; et al. Combating Global Antibiotic Resistance: Emerging One Health Concerns in Lower-and Middle-Income Countries. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2018, 66, 963–969. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Singh, A.; Dar, M.A.; Kaur, R.J.; Charan, J.; Iskandar, K.; Haque, M.; Murti, K.; Ravichandiran, V.; Dhingra, S. Menace of Antimicrobial Resistance in LMICs: Current Surveillance Practices and Control Measures to Tackle Hostility. J Infect Public Health 2022, 15, 172–181. [CrossRef]

- Gulumbe, B.H.; Danlami, M.B.; Abdulrahim, A. Closing the Antimicrobial Stewardship Gap - a Call for LMICs to Embrace the Global Antimicrobial Stewardship Accreditation Scheme. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2024, 13, 19. [CrossRef]

- Iskandar, K.; Molinier, L.; Hallit, S.; Sartelli, M.; Hardcastle, T.C.; Haque, M.; Lugova, H.; Dhingra, S.; Sharma, P.; Islam, S.; et al. Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scattered Picture. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2021, 10, 63. [CrossRef]

- Eden, T.; Burns, E.; Freccero, P.; Renner, L.; Paintsil, V.; Dolendo, M.; Scanlan, T.; Khaing, A.A.; Pina, M.; Islam, A.; et al. Are Essential Medicines Available, Reliable and Affordable in Low-Middle Income Countries? J Cancer Policy 2019, 19, 100180. [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, S.; Shankar, R.; Leopold, C.; Orubu, S. Access to Medicines through Health Systems in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. Health Policy Plan 2019, 34, III1–III3. [CrossRef]

- Collignon, P.; Beggs, J.J.; Walsh, T.R.; Gandra, S.; Laxminarayan, R. Anthropological and Socioeconomic Factors Contributing to Global Antimicrobial Resistance: A Univariate and Multivariable Analysis. Lancet Planet Health 2018, 2, e398–e405. [CrossRef]

- Sulis, G.; Sayood, S.; Gandra, S. Antimicrobial Resistance in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Current Status and Future Directions. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2022, 20, 147–160. [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, S.; Raut, S.; Adhikari, B. Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. BMJ Glob Health 2019, 4, e002104.

- Otaigbe, I.I.; Elikwu, C.J. Drivers of Inappropriate Antibiotic Use in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2023, 5, dlad062.

- World Health Organization Access to Essential Medicines, Vaccines and Health Technologies: Fact Sheet on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Health Targets; 2017;

- Huong, V.T.L.; Ngan, T.T.D.; Thao, H.P.; Tu, N.T.C.; Quan, T.A.; Nadjm, B.; Kesteman, T.; Kinh, N. Van; van Doorn, H.R. Improving Antimicrobial Use through Antimicrobial Stewardship in a Lower-Middle Income Setting: A Mixed-Methods Study in a Network of Acute-Care Hospitals in Viet Nam. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2021, 27, 212–221. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization WHO Competency Framework for Health Workers’ Education and Training on Antimicrobial Resistance.; 2018;

- Kerr, F.; Sefah, I.A.; Essah, D.O.; Cockburn, A.; Afriyie, D.; Mahungu, J.; Mirfenderesky, M.; Ankrah, D.; Aggor, A.; Barrett, S.; et al. Practical Pharmacist-Led Interventions to Improve Antimicrobial Stewardship in Ghana, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 124. [CrossRef]

- Kpokiri, E.E.; Ladva, M.; Dodoo, C.C.; Orman, E.; Aku, T.A.; Mensah, A.; Jato, J.; Mfoafo, K.A.; Folitse, I.; Hutton-Nyameaye, A.; et al. Knowledge, Awareness and Practice with Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes among Healthcare Providers in a Ghanaian Tertiary Hospital. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 6. [CrossRef]

- Mudenda, S.; Chabalenge, B.; Daka, V.; Jere, E.; Sefah, I.A.; Wesangula, E.; Yamba, K.; Nyamupachitu, J.; Mugenyi, N.; Mustafa, Z.U.; et al. Knowledge, Awareness and Practices of Healthcare Workers Regarding Antimicrobial Use, Resistance and Stewardship in Zambia: A Multi-Facility Cross-Sectional Study. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2024, 6, dlae076. [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, O.K.O.; Courtenay, A.; Kwame Ayisi-Boateng, N.; Abuelhana, A.; Opoku, D.A.; Kobina Blay, L.; Abruquah, N.A.; Osafo, A.B.; Danquah, C.B.; Tawiah, P.; et al. Assessing the Impact of Antimicrobial Stewardship Implementation at a District Hospital in Ghana Using a Health Partnership Model. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2023, 5, dlad084. [CrossRef]

- Knowles, R.; Chandler, C.; O’neill, S.; Sharland, M.; Mays, N. A Systematic Review of National Interventions and Policies to Optimize Antibiotic Use in Healthcare Settings in England. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2024, 79, 1234–1247. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Health-Care Facilities in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. A WHO Practical Toolkit; 2019;

- 2021; 37. World Health Organization WHO Policy Guidance on Integrated Antimicrobial Stewardship Activities; 2021;

- Njeru, J.; Odero, J.; Chebore, S.; Ndung’u, M.; Tanui, E.; Wesangula, E.; Ndanyi, R.; Githii, S.; Gunturu, R.; Mwangi, W.; et al. Development, Roll-out and Implementation of an Antimicrobial Resistance Training Curriculum Harmonizes Delivery of in-Service Training to Healthcare Workers in Kenya. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1142622. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Health Workers’ Education and Training on Antimicrobial Resistance: Curricula Guide; 2019;

- Wilkinson, A.; Ebata, A.; Macgregor, H. Interventions to Reduce Antibiotic Prescribing in LMICs: A Scoping Review of Evidence from Human and Animal Health Systems. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 2.

- Maki, G.; Smith, I.; Paulin, S.; Kaljee, L.; Kasambara, W.; Mlotha, J.; Chuki, P.; Rupali, P.; Singh, D.R.; Bajracharya, D.C.; et al. Feasibility Study of the World Health Organization Health Care Facility-Based Antimicrobial Stewardship Toolkit for Low-and Middle-Income Countries. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 556. [CrossRef]

- Ashiru-Oredope, D.; Garraghan, F.; Olaoye, O.; Krockow, E.M.; Matuluko, A.; Nambatya, W.; Babigumira, P.A.; Tuck, C.; Amofah, G.; Ankrah, D.; et al. Development and Implementation of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Checklist in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Co-Creation Consensus Approach. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1706. [CrossRef]

- Zanichelli, V.; Sharland, M.; Cappello, B.; Moja, L.; Getahun, H.; Pessoa-Silva, C.; Sati, H.; van Weezenbeek, C.; Balkhy, H.; Simão, M.; et al. The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) Antibiotic Book and Prevention of Antimicrobial Resistance. Bull World Health Organ 2023, 101, 290–296. [CrossRef]

- Hsia, Y.; Lee, B.R.; Versporten, A.; Yang, Y.; Bielicki, J.; Jackson, C.; Newland, J.; Goossens, H.; Magrini, N.; Sharland, M. Use of the WHO Access, Watch, and Reserve Classification to Define Patterns of Hospital Antibiotic Use (AWaRe): An Analysis of Paediatric Survey Data from 56 Countries. Lancet Glob Health 2019, 7, e861–e871. [CrossRef]

- Mudenda, S.; Daka, V.; Matafwali, S.K. World Health Organization AWaRe Framework for Antibiotic Stewardship: Where Are We Now and Where Do We Need to Go? An Expert Viewpoint. Antimicrobial Stewardship & Healthcare Epidemiology 2023, 3, e84. [CrossRef]

- Kakkar, A.K.; Shafiq, N.; Singh, G.; Ray, P.; Gautam, V.; Agarwal, R.; Muralidharan, J.; Arora, P. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs in Resource-Constrained Environments: Understanding and Addressing the Need of the Systems. Front Public Health 2020, 8, 140.

- Veepanattu, P.; Singh, S.; Mendelson, M.; Nampoothiri, V.; Edathadatil, F.; Surendran, S.; Bonaconsa, C.; Mbamalu, O.; Ahuja, S.; Birgand, G.; et al. Building Resilient and Responsive Research Collaborations to Tackle Antimicrobial Resistance—Lessons Learnt from India, South Africa, and UK. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020, 100, 278–282.

- Nassar, H.; Abu-Farha, R.; Barakat, M.; Alefishat, E. Antimicrobial Stewardship from Health Professionals’ Perspective: Awareness, Barriers, and Level of Implementation of the Program. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 99. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.P.; Chintu, C.; Mpundu, M.; Kibuule, D.; Hazemba, O.; Andualem, T.; Embrey, M.; Phulu, B.; Gerba, H. Multidisciplinary and Multisectoral Coalitions as Catalysts for Action against Antimicrobial Resistance: Implementation Experiences at National and Regional Levels. Glob Public Health 2018, 13, 1781–1795. [CrossRef]

- 2019; 50. Ministry of Health Kenya Guidelines, Standards & Policies Portal; 2019;

- Chukwu, E.E.; Abuh, D.; Idigbe, I.E.; Osuolale, K.A.; Chuka-Ebene, V.; Awoderu, O.; Audu, R.A.; Ogunsola, F.T. Implementation of Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs: A Study of Prescribers’ Perspective of Facilitators and Barriers. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0297472. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization South African Antimicrobial Resistance National Strategy Framework: A One Health Approach 2018 - 2024; 2018;

- N: Health Organization Vietnam, 2013; 53. World Health Organization Vietnam: National Action Plan for Combating Drug Resistance; 2013;

- Musoke, D.; Kitutu, F.E.; Mugisha, L.; Amir, S.; Brandish, C.; Ikhile, D.; Kajumbula, H.; Kizito, I.M.; Lubega, G.B.; Niyongabo, F.; et al. A One Health Approach to Strengthening Antimicrobial Stewardship in Wakiso District, Uganda. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 764. [CrossRef]

- Menezes, R.M.; Gonçalves, M.R.S.; Costa, M.M. de M.; Krumennauer, E.C.; Carneiro, G.M.; Reuter, C.P.; Renner, J.D.P.; Carneiro, M. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Brazil: Introductory Analysis. Research, Society and Development 2022, 11, e51011729444. [CrossRef]

- 2017; 56. Government of the Republic of Zambia Multi-Sectoral National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance; 2017;

- N: Health Organization Kenya, 2017; 57. World Health Organization Kenya: National Action Plan on Prevention and Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance 2017-2022; 2017;

- Al-Omari, A.; Al Mutair, A.; Alhumaid, S.; Salih, S.; Alanazi, A.; Albarsan, H.; Abourayan, M.; Al Subaie, M. The Impact of Antimicrobial Stewardship Program Implementation at Four Tertiary Private Hospitals: Results of a Five-Years Pre-Post Analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2020, 9, 95. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Hadi, H.; Eltayeb, F.; Al Balushi, S.; Daghfal, J.; Ahmed, F.; Mateus, C. Evaluation of Hospital Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs: Implementation, Process, Impact, and Outcomes, Review of Systematic Reviews. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 253. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, T.G.; Robertson, J.; Van Den Ham, H.A.; Iwamoto, K.; Bak Pedersen, H.; Mantel-Teeuwisse, A.K. Assessing the Impact of Law Enforcement to Reduce Over-the-Counter (OTC) Sales of Antibiotics in Low- And Middle-Income Countries; A Systematic Literature Review. BMC Health Serv Res 2019, 19, 536.

- Cuevas, C.; Batura, N.; Wulandari, L.P.L.; Khan, M.; Wiseman, V. Improving Antibiotic Use through Behaviour Change: A Systematic Review of Interventions Evaluated in Low- And Middle-Income Countries. Health Policy Plan 2021, 36, 754–773.

- Alabi, A.S.; Picka, S.W.; Sirleaf, R.; Ntirenganya, P.R.; Ayebare, A.; Correa, N.; Anyango, S.; Ekwen, G.; Agu, E.; Cook, R.; et al. Implementation of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme in Three Regional Hospitals in the South-East of Liberia: Lessons Learned. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2022, 4, dlac069. [CrossRef]

- Aiken, A.M.; Wanyoro, A.K.; Mwangi, J.; Juma, F.; Mugoya, I.K.; Scott, J.A.G. Changing Use of Surgical Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Thika Hospital, Kenya: A Quality Improvement Intervention with an Interrupted Time Series Design. PLoS One 2013, 8, e78942. [CrossRef]

- Brink, A.J.; Messina, A.P.; Feldman, C.; Richards, G.A.; Becker, P.J.; Goff, D.A.; Bauer, K.A.; Nathwani, D.; van den Bergh, D. Antimicrobial Stewardship across 47 South African Hospitals: An Implementation Study. Lancet Infect Dis 2016, 16, 1017–1025. [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, U.; Sulaiman, S.A.S.; Adesiyun, A.G. Impact of Pharmacist-Led Antibiotic Stewardship Interventions on Compliance with Surgical Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Obstetric and Gynecologic Surgeries in Nigeria. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0213395. [CrossRef]

- Kpokiri, E.E.; Taylor, D.G.; Smith, F.J. Development of Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes in Low and Middle-Income Countries: A Mixed-Methods Study in Nigerian Hospitals. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 204. [CrossRef]

- Mzumara, G.W.; Mambiya, M.; Iroh Tam, P.Y. Protocols, Policies and Practices for Antimicrobial Stewardship in Hospitalized Patients in Least-Developed and Low-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2023, 12, 131. [CrossRef]

- Shamas, N.; Stokle, E.; Ashiru-Oredope, D.; Wesangula, E. Challenges of Implementing Antimicrobial Stewardship Tools in Low to Middle Income Countries (LMICs). Infection Prevention in Practice 2023, 5, 100315. [CrossRef]

- Sefah, I.A.; Chetty, S.; Yamoah, P.; Godman, B.; Bangalee, V. An Assessment of the Current Level of Implementation of the Core Elements of Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs in Public Hospitals in Ghana. Hosp Pharm 2024, 59, 367–377. [CrossRef]

- Aika, I.N.; Enato, E. Health Care Systems Administrators Perspectives on Antimicrobial Stewardship and Infection Prevention and Control Programs across Three Healthcare Levels: A Qualitative Study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2022, 11, 157. [CrossRef]

- Storr, J.; Twyman, A.; Zingg, W.; Damani, N.; Kilpatrick, C.; Reilly, J.; Price, L.; Egger, M.; Grayson, M.L.; Kelley, E.; et al. Core Components for Effective Infection Prevention and Control Programmes: New WHO Evidence-Based Recommendations. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2017, 6, 6. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Interim Practical Manual Supporting National Implementation of the WHO Guidelines on Core Components of Infection Prevention and Control Programmes 2017, 1–77.

- World Health Organization Improving Infection Prevention and Control at the Health Facility: An Interim Practical Manual; 2018;

- 2016; 74. World Health Organization Guidelines on Core Components of Infection Prevention and Control Programmes at the National and Acute Health Care Facility Level; 2016;

- Cheong, H.S.; Park, K.H.; Kim, H. Bin; Kim, S.W.; Kim, B.; Moon, C.; Lee, M.S.; Yoon, Y.K.; Jeong, S.J.; Kim, Y.C.; et al. Core Elements for Implementing Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs in Korean General Hospitals. Infect Chemother 2022, 54, 637–673. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Yu, X.; Zhou, H.; Li, B.; Chen, G.; Ye, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cui, X.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Impact of Antimicrobial Stewardship Managed by Clinical Pharmacists on Antibiotic Use and Drug Resistance in a Chinese Hospital, 2010-2016: A Retrospective Observational Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026072. [CrossRef]

- Siachalinga, L.; Mufwambi, W.; Lee, I.-H. Impact of Antimicrobial Stewardship Interventions to Improve Antibiotic Prescribing for Hospital Inpatients in Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Hospital Infection 2022, 129, 124–143.

- Bantar, C.; Sartori, B.; Vesco, E.; Heft, C.; Saúl, M.; Salamone, F.; Oliva, M.E. A Hospitalwide Intervention Program to Optimize the Quality of Antibiotic Use: Impact on Prescribing Practice, Antibiotic Consumption, Cost Savings, and Bacterial Resistance. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2003, 37, 180–186. [CrossRef]

- Nyoloka, N.; Richards, C.; Mpute, W.; Chadwala, H.M.; Kumwenda, H.S.; Mwangonde-Phiri, V.; Phiri, A.; Phillips, C.; Makanga, C. Pharmacist-Led Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme in Two Tertiary Hospitals in Malawi. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 480. [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, J.; Cooper, L.; Afriyie, D.K.; Sefah, I.A.; Cockburn, A.; Kerr, F.; Cameron, E.; Goldthorpe, J.; Kurdi, A.; Andrew Seaton, R. Supporting Antimicrobial Stewardship in Ghana: Evaluation of the Impact of Training on Knowledge and Attitudes of Healthcare Professionals in Two Hospitals. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2020, 2, dlaa092. [CrossRef]

- Ashiru-Oredope, D.; Nabiryo, M.; Zengeni, L.; Kamere, N.; Makotose, A.; Olaoye, O.; Townsend, W.; Waddingham, B.; Matuluko, A.; Nambatya, W.; et al. Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance: Developing and Implementing Antimicrobial Stewardship Interventions in Four African Commonwealth Countries through a Health Partnership Model. J Public Health Afr 2023, 14, 2335. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.K.; Dahmash, E.Z.; Madi, T.; Tarawneh, O.; Jomhawi, T.; Alkhob, W.; Ghanem, R.; Halasa, Z. Four Years after the Implementation of Antimicrobial Stewardship Program in Jordan: Evaluation of Program’s Core Elements. Front Public Health 2023, 11, 1078596. [CrossRef]

- Sabbatucci, M.; Ashiru-Oredope, D.; Barbier, L.; Bohin, E.; Bou-Antoun, S.; Brown, C.; Clarici, A.; Fuentes, C.; Goto, T.; Maraglino, F.; et al. Tracking Progress on Antimicrobial Resistance by the Quadripartite Country Self-Assessment Survey (TrACSS) in G7 Countries, 2017–2023: Opportunities and Gaps. Pharmacol Res 2024, 204, 107188. [CrossRef]

- Lazure, P.; Augustyniak, M.; Goff, D.A.; Villegas, M.V.; Apisarnthanarak, A.; Peloquin, S. Gaps and Barriers in the Implementation and Functioning of Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes: Results from an Educational and Behavioural Mixed Methods Needs Assessment in France, the United States, Mexico and India. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2022, 4, dlac094. [CrossRef]

- Dodoo, C.C.; Odoi, H.; Mensah, A.; Asafo-Adjei, K.; Ampomah, R.; Obeng, L.; Jato, J.; Hutton-Nyameaye, A.; Aku, T.A.; Somuah, S.O.; et al. Development of a Local Antibiogram for a Teaching Hospital in Ghana. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2023, 5, dlad024. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, P.; Ranjalkar, J.; Chandy, S.J. Challenges in Implementing Antimicrobial Stewardship Programmes at Secondary Level Hospitals in India: An Exploratory Study. Front Public Health 2020, 8, 493904. [CrossRef]

- 2023; 87. East Central and Southern Africa-Health Community Meeting Report Joint Regional Meeting on Antimicrobial Stewardship and Antimicrobial Surveillance in Eastern and Southern Africa Co-Sponsored by the East Central and Southern Africa-Health Community and Africa Centres for Disease; 2023;

- CDC Core Elements of Antibiotic Stewardship | Antibiotic Use | CDC. April 7 2024, 1–7.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).