1. Introduction

The global burden of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has been growing fast with a prediction of 700,000 deaths per year estimated by WHO and the UN and makes the predicted ’10 million deaths due to AMR by 2050′ (and its economic impact) [

1]. The sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries are more affected, especially among hospitalized adults [

2]. The hospitalized patients are currently presenting with a rise of nosocomial infections (40%

K. pneumoniae and 35.4%

E. coli isolates were ESBL producers [

3]). The overall prevalence of ESBLs in all gram-negative bacteria is reported at 29% from 377 clinical isolates with 64% in

K. pneumonia and 24% in

E. coli in sputum and wound samples [

4]. In Mwanza, Tanzania that used swab samples from the tonsillar surface revealed Methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was observed in 39% of isolates [

5]. Most of these isolates have been associated with poor outcomes [

6].

Despite the availability of a wide range of antimicrobials, treatment failure due to poor adherence to medication, drug toxicities and use of antimicrobials with lower genetic barriers are very common [

7]. Clinicians working in rural primary care settings in developing countries like Tanzania are potentially overwhelmed with patients and thus present a potential risk of unguided antimicrobial use. Despite the availability of surveillance tools [

8] like WHONET [

9], GLASS [

10] and WHO TAP [

11], the prescription behaviour change test and reporting of antimicrobial Use (AMU) have been found to be rare [

12]. The WHO AWaRe classification system categorizes antibiotic use into Access, Watch, and Reserve groups to promote appropriate antibiotic use and combat antimicrobial resistance. The goal is to increase the use of Access antibiotics (those with lower resistance risk) while reducing reliance on Watch and Reserve antibiotics, which are critical for treating severe infections [

13].

The antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) have repeatedly reported the inappropriate use of antimicrobials due to missed guidance [

8] has resulted in inappropriate prescription of extended-spectrum Penicillin, Ceftriaxone and Azithromycin by drug dose, frequency, and route of administration[

14]. Evidence exists that these three antibiotics are haphazardly given due to the missed AMU metrics in the hospital facilities [

15,

16,

17] and misunderstanding the AWaRe classification system. It is, therefore, important to measure AMU by demand, indication, dose, frequency and duration in addressing the second and fourth objectives of the global action plan for antimicrobial resistance. This highlights the need for local antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) and reporting to support AMS teams [

18].

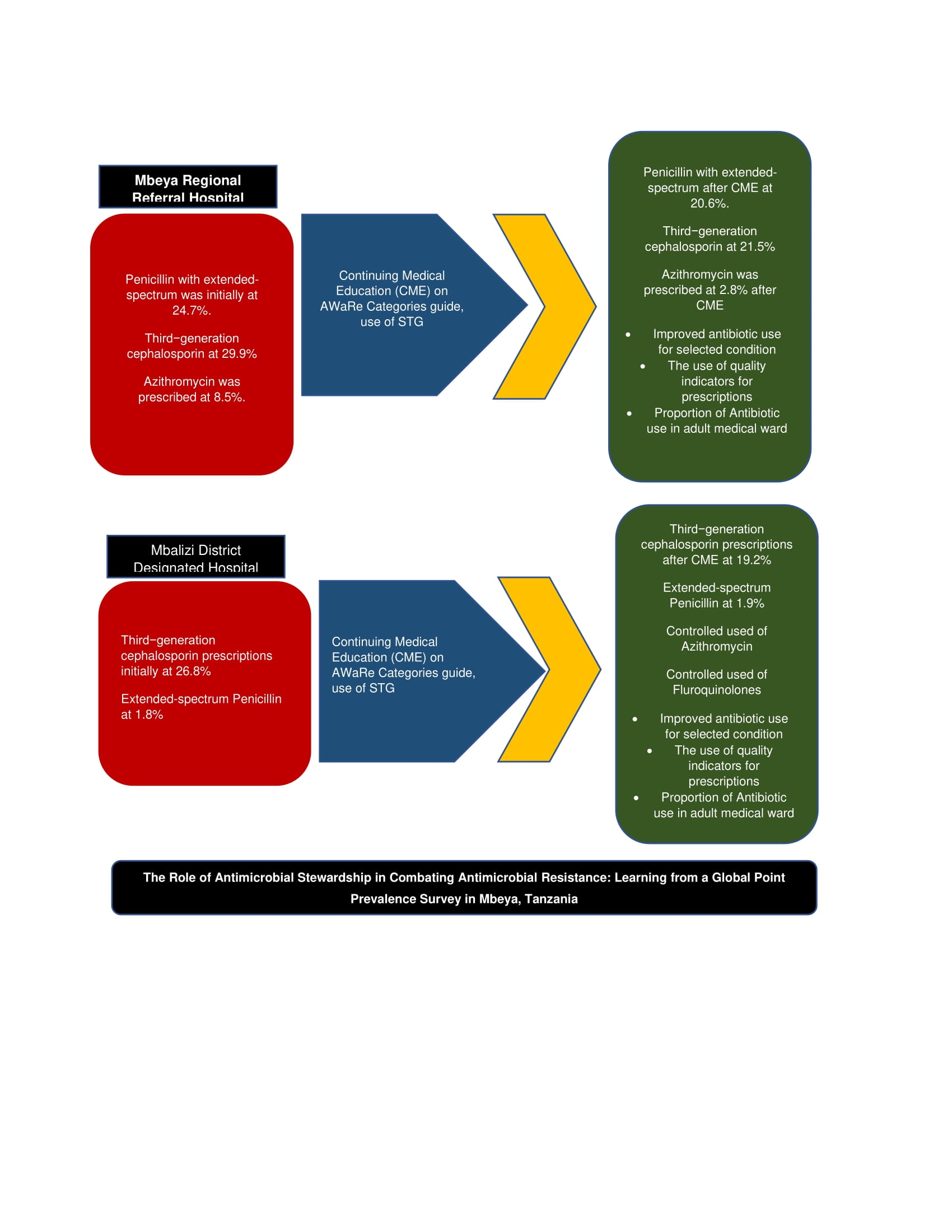

We conducted the one-day Global Point Prevalence Survey (G-PPS) in 2 hospitals in, Tanzania to assess and compare the quantity and quality of antimicrobial use by AWaRe classification systems among the admitted adults, children and neonates. We focused on the control of AMU for extended-spectrum Penicillin, Ceftriaxone and Azithromycin in Mbeya, Tanzania.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

The University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM)—Mbeya College of Heath and Allied Sciences (MCHAS) and Henry Jackson Foundation Medical Research International (HJFMRI) conducted a one-day cross-sectional survey conducted in three phases in 2 hospitals of Mbeya, Tanzania. Before the surveys, two multidisciplinary Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS) teams were established at Mbeya Regional Referral Hospital (Mbeya RRH) and Mbalizi Designated District Hospital (Mbalizi DDH)

. The teams performed a baseline assessment and a follow-up assessment using G-PPS methodologies for all available antimicrobials with a focus on extended-spectrum Penicillin, Ceftriaxone and Azithromycin. Between the surveys, the teams shared the progress data, provided mentorships on prescription in the hospital Continuous Medical Education (CME) sessions and used the continuous quality improvement CQI by plan–do–study–act approach [

19,

20] in monitoring prescriptions improvement.

2.2. Settings, Duration and Interventions

The surveys used the Global Point Prevalence Survey (PPS) [

21] of antimicrobial (antibiotics) consumption at Mbeya Regional Referral Hospital (Mbeya RRH) and Mbalizi Designated District Hospital (Mbalizi DDH) Southern Highlands of Tanzania. The GPPS uses a web-based tool to measure and monitor antimicrobial use with the descriptive intermittent GPPS data collection data analysis, and interpretation in a single day [

22]. In our setting, we conducted GPPS on

2nd June 2022 and repeated on

8th September 2022 view of the national Standard Treatment Guideline for indication, dosing, frequency and duration.

These G-PPS were performed in one day by recruiting all admitted patients who were on antimicrobials from 08:00 am on the day of the survey at the two primary facilities of Mbeya, Tanzania. The G-PPS allowed the automatic determination of prescription errors, mistakes, and inappropriate allocation of antibiotics. The (G-PPS) tools also gave a summary comparison to the rest of the average African hospitals and Global AMU data.

The use of Continuing Medical Education (CME) was done as a part of morning clinical meetings for professional development for physicians, nurses and pharmacists in improving their knowledge, skills, and competence for prescriptions and dispensing. AMS teams provided learning sessions with abreast of the latest advancements on WHO guides for AwaRe categorization and the use of the Standard Treatment Guidelines and Essential Medicines List of Tanzania (STG/NEMLIT) [

23].

2.3. Participants

All patients found admitted to the hospital on the day of the survey were recruited with the total admitted patients in the ward providing the departmental data (Ward data) being the denominator data and entries from patients recorded in the patient form (numerator data).

2.4. Eligibility

2.4.1. Inclusion Criteria

Any patient who was on at least one antimicrobial at 8 am on the day of the G-PPS was included to provide the numerator data of the survey. Any patient with any active and ongoing antimicrobials: include an ongoing antimicrobial prescribed e.g., 3 times/week but until the day of the survey was included in the survey. Any patient who was on Antimicrobials under surveillance (according to WHO ATC classification; this is done automatically during data-entry by the Global-PPS programme), Antibacterials for systemic use: J01, Antimycotics and antifungals for systemic use: J02 and D01BA, Antibiotics and other drugs used for treatment of tuberculosis: J04A, Antibiotics used as intestinal anti-infectives: A07AA, Antiprotozoals used as antibacterial agents, nitroimidazole derivatives: P01AB, Antivirals: J05, Antimalarials: P01B,

2.4.2. Exclusion Criteria

Any patient who was on Antimicrobials for topical use was excluded. Patients admitted on the Day of hospitalization and those admitted for ambulatory care were excluded. Patients admitted to the ward after 8 am on the day of the survey even if were on antimicrobials were excluded.

2.5. Data Sources, Variables and Measurements

The survey used Global-PPS tools to assist in the collection and reporting of the detailed institutional, infectious wards and patients prescribed with antimicrobial agents. The Global Point Prevalence Survey of Antimicrobial Consumption and Resistance (Global-PPS) gave a simple, freely available web-based data management from all patients admitted with a measurement of proportional correct naming, indications, dose and frequency antimicrobial prescribing that can be linked to hospital-based resistance and compared to other centres worldwide.

Data collected from all wards (units/departments) of the hospital will be included once. Surgical departments were not surveyed after a weekend or holiday in order to allow retrospective data collection on surgical prophylaxis. Data was therefore collected on a weekday, not on the weekend or a holiday.

Wards were mainly categorized as Adult wards or Pediatric Wards which were further sub-categorized as Adult medical wards, Adult Surgical wards, Adult Intensive Care wards, Pediatric Medical Wards, Neonatal Medical wards and Neonatal Intensive care wards. Patients admitted for medical reasons who were placed in the designed surgical wards were recognized as patients in mixed wards and those with surgical or ICU treatments admitted in medical wards were also termed as admitted in the mixed wards.

2.6. Bias

There was little information bias on the patients identified as those admitted in the mixed wards. Based on the nature of the surveys and timings it was difficult to use data from the same patients in all surveys.

2.7. Quantitative Variables

The proportions of antimicrobial agent/s (substance level—generic name) per facility, Start date antimicrobial (optional), Dose per administration—number of doses/day—route of administration, Reasons for treatment (anatomical site of infection). The indication of What the clinician intends to treat as an Indication for therapy (community-acquired or Healthcare healthcare-associated infection; Medical or Surgical Prophylaxis) was recorded.

2.8. Statistical Methods

A descriptive statistic on the proportion of antimicrobials was given by age, hospital name, need for antibiotics, category of patient admitted and quality indicators for antibiotic use.

2.9. Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and had been reviewed and approved by the local Institutional Review Board (IRB) in Mbeya i.e., Mbeya Medical Research and Ethics Review Committee (MMREC) through the certificate number SZEC—2439/R.A/24/10, and National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR)—National Health Research Ethics Committee (NatHREC), through the certificate number NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol.IX/4811. Patients were asked for consent before data collection on AMU and patents as well and the hospital data were handled with the utmost confidentiality.

3. Results

A total of 177 patients were studied in the two hospitals of Mbeya RRH and Mbalizi DDH Southern Highlands of Tanzania.

On 2nd June 2022—8.00 am, at Mbeya RRH: 97 prescriptions, there were 47 treated patients; African Continent: 5368 prescriptions, 49 hospitals, 52 surveys; Secondary Level: 384 prescriptions, 5 hospitals, 6 surveys, Europe: 5880 prescriptions, 68 hospitals, 70 surveys. On the same day, at Mbalizi DDH: 56 prescriptions, and 38 treated patients.

On 8th September 2022—8.00 am at Mbeya RRH there were 107 prescriptions, 59 treated patients; African Continent: 5,943 prescriptions, 34 hospitals, 41 surveys; Secondary level: 719 prescriptions, 8 hospitals, 11 surveys, Europe: 6475 prescriptions, 76 hospitals, 78 surveys.

On the same day at Mbalizi DDH: 52 prescriptions, 33 treated patients; African Continent: 6,431 prescriptions, 36 hospitals, 43 surveys; Primary level: 719 prescriptions, 8 hospitals, 11 surveys Europe: 6799 prescriptions, and 77 hospitals in 79 surveys.

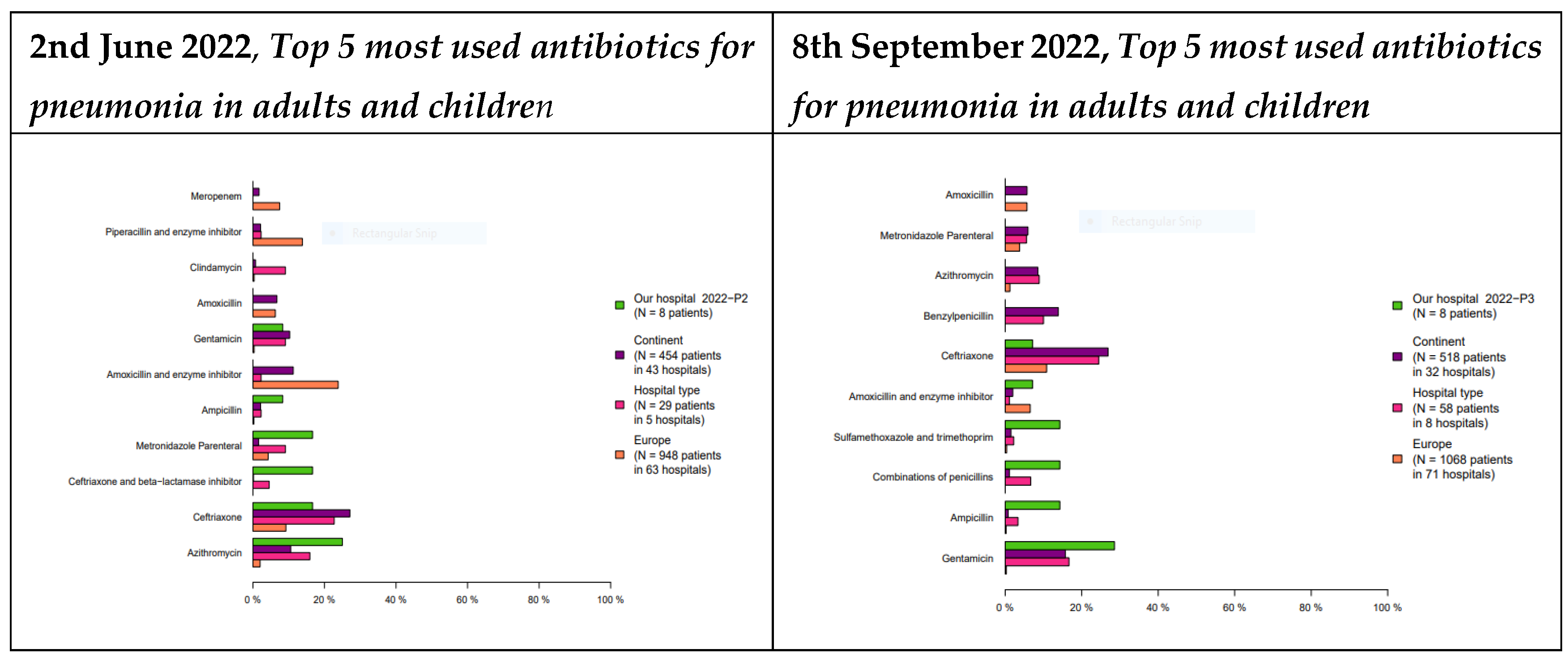

3.1. Antibiotic Prescriptions for the Selected Conditions

The study found a change in the top most used antibiotics at MRRH. The change was from 1st Azithromycin 25%, 2nd Ceftriaxone 15%, 3rd Ceftriaxone and beta-lactamase inhibitor 14%, 4th metronidazole 13%, and 5th Ampicillin 10% being the top prescribed in June 2022 to Gentamycin being the 1st (29%), Ampicillin (18%), a combination of penicillin (17%), Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole (16%), Amoxycillin and enzyme inhibitor (9%) in September 2022. The study also found a change in the top most used antibiotics at MDDH from Ceftriaxone 35%, a combination of penicillin 34%, gentamycin 22%, metronidazole parenteral 11%, Amoxycillin with enzyme inhibitor 2% being the top prescribed in June 2022 that changed to Gentamycin 30%, Benzathine penicillin 15%, benzylpenicillin 14%, ceftriaxone 13.5%, a combination of penicillins 13%. For details see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

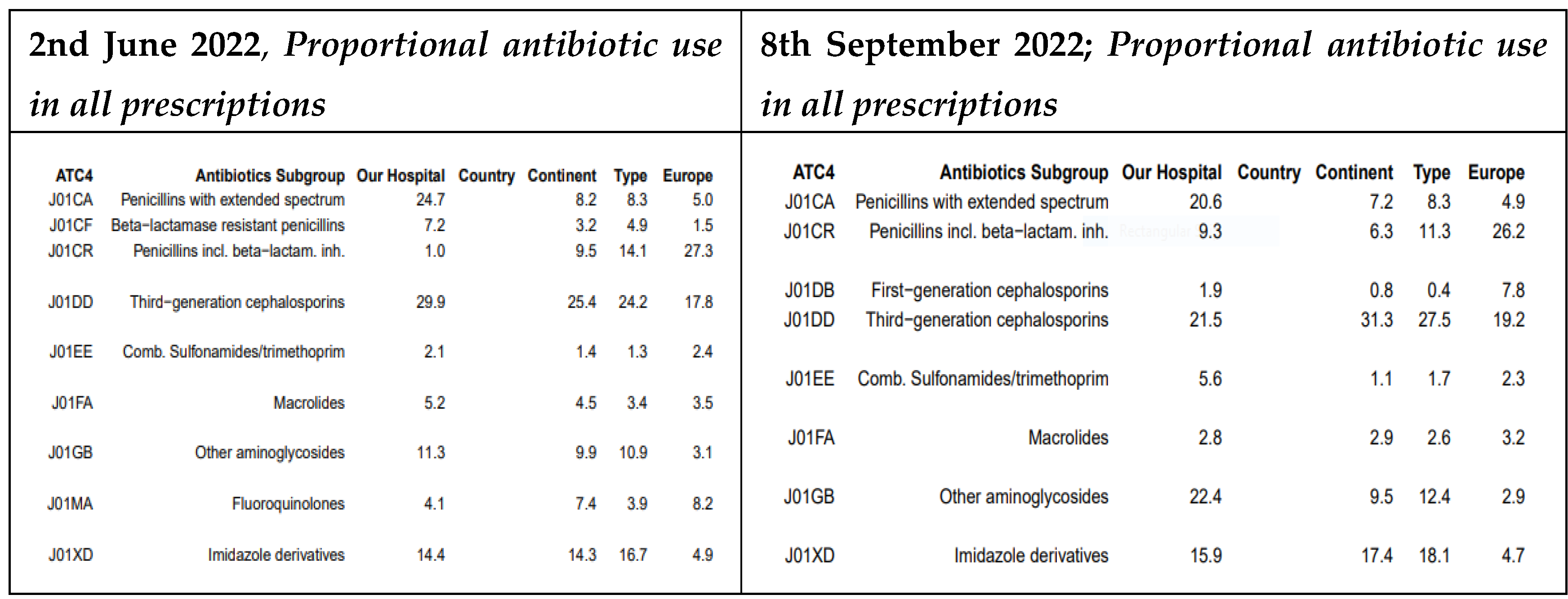

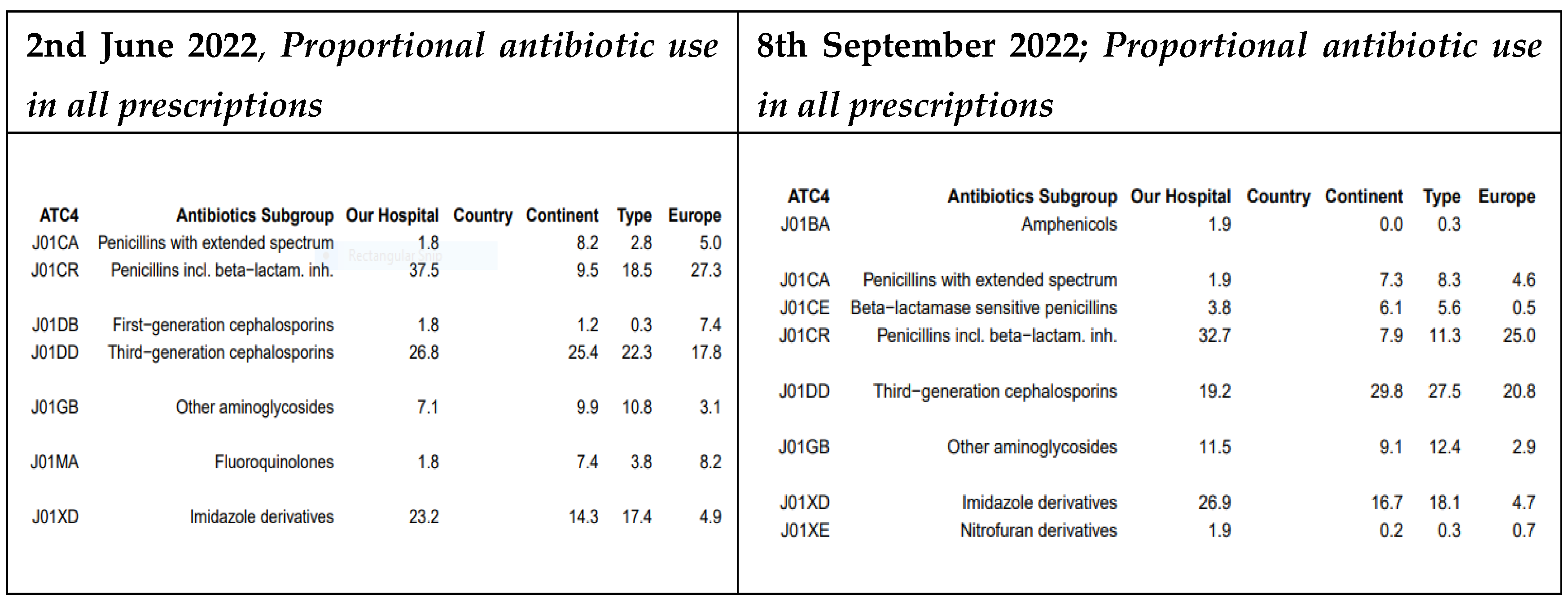

3.2. The Patterns of All Prescriptions in GPPS

At MRRH, the prescription rates for several antibiotic classes decreased between May and September 2022. Specifically, the use of extended-spectrum penicillins dropped from 24.7% to 20.6%, third-generation cephalosporins from 29.9% to 21.5%, and macrolides from 5.2% to 2.8%. In contrast, prescriptions for beta-lactamase–resistant penicillins increased from 7.2% to 9.3% during the same period (For details see

Figure 3).

At MDDH, the prescription rate for third-generation cephalosporins declined from 26.8% in May 2022 to 19.2% in September 2022. Additionally, fluoroquinolones were no longer prescribed for urinary tract infections (UTIs) and were replaced by nitrofurantoin (

Figure 4).

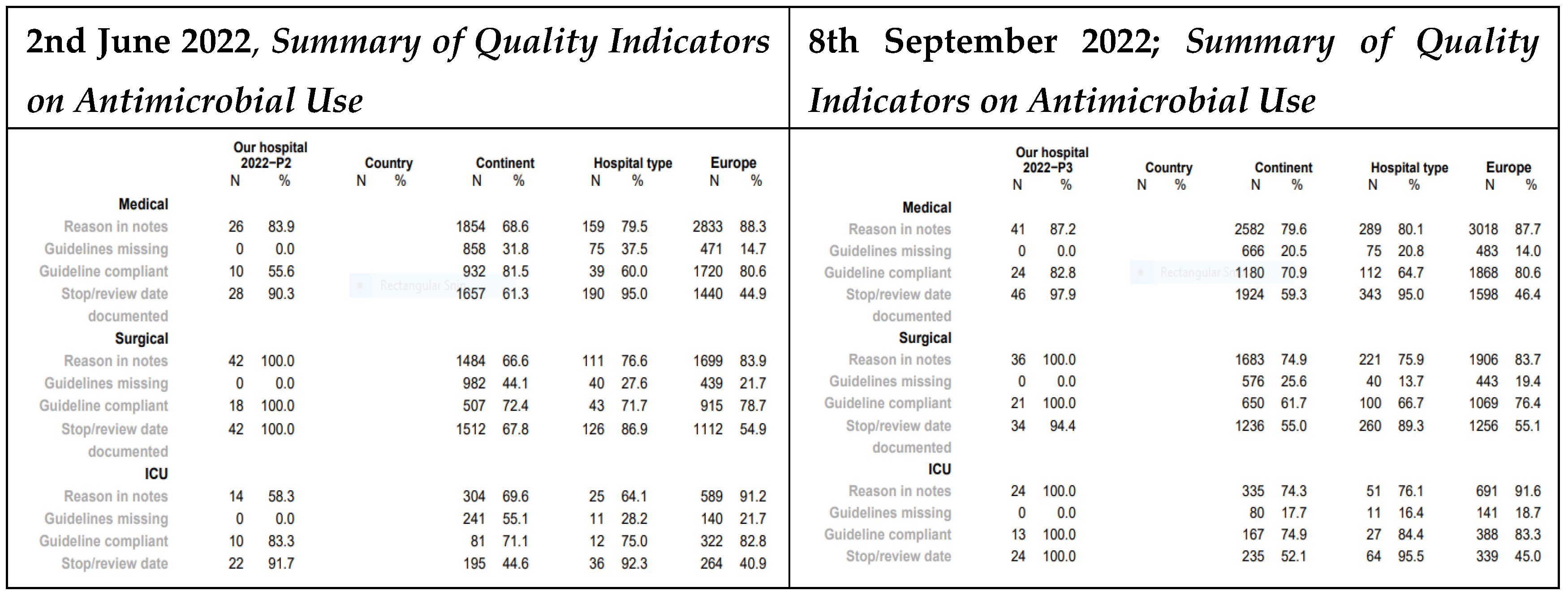

3.3. Quality Indicators

At MRRH, the medical department showed improvements from May to September 2022 in several antimicrobial stewardship indicators: documentation of reasons for prescription increased from 83.9% to 87.2%, guideline compliance from 53.6% to 82.8%, and recording of stop/review dates from 90.3% to 97.9%. In the ICU, three indicators of reasons for prescription (58.3%), guideline compliance (83.3%), and stop/review date (91.7%) rose to 100% (For details see

Figure 5).

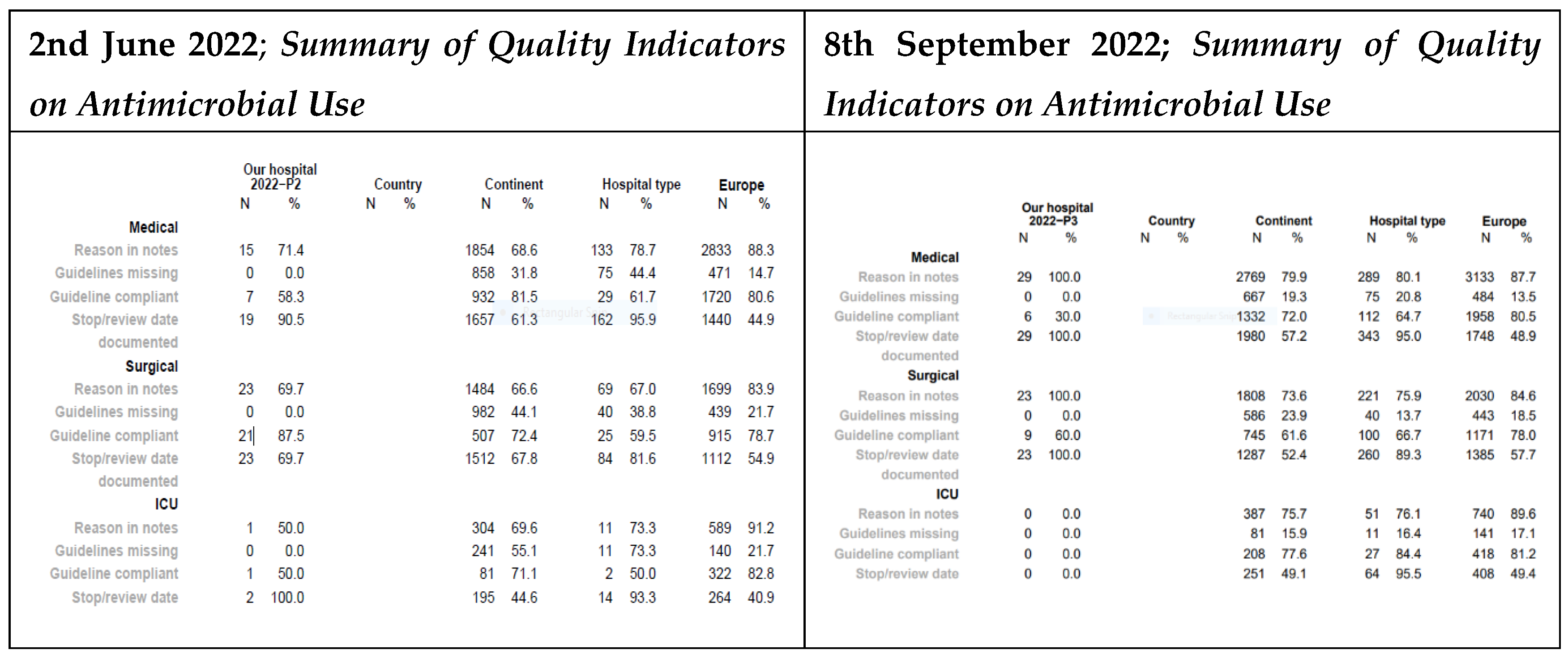

At Mbalizi DDH, the medical unit saw increases in reasons for prescription (from 71.4% to 100%) and stop/review date documentation (from 90.5% to 100%). In the surgical unit, both indicators also improved from 69.7% to 100% (For details see

Figure 6). However, due to the low number of ICU cases at MDDH, its impact could not be assessed.

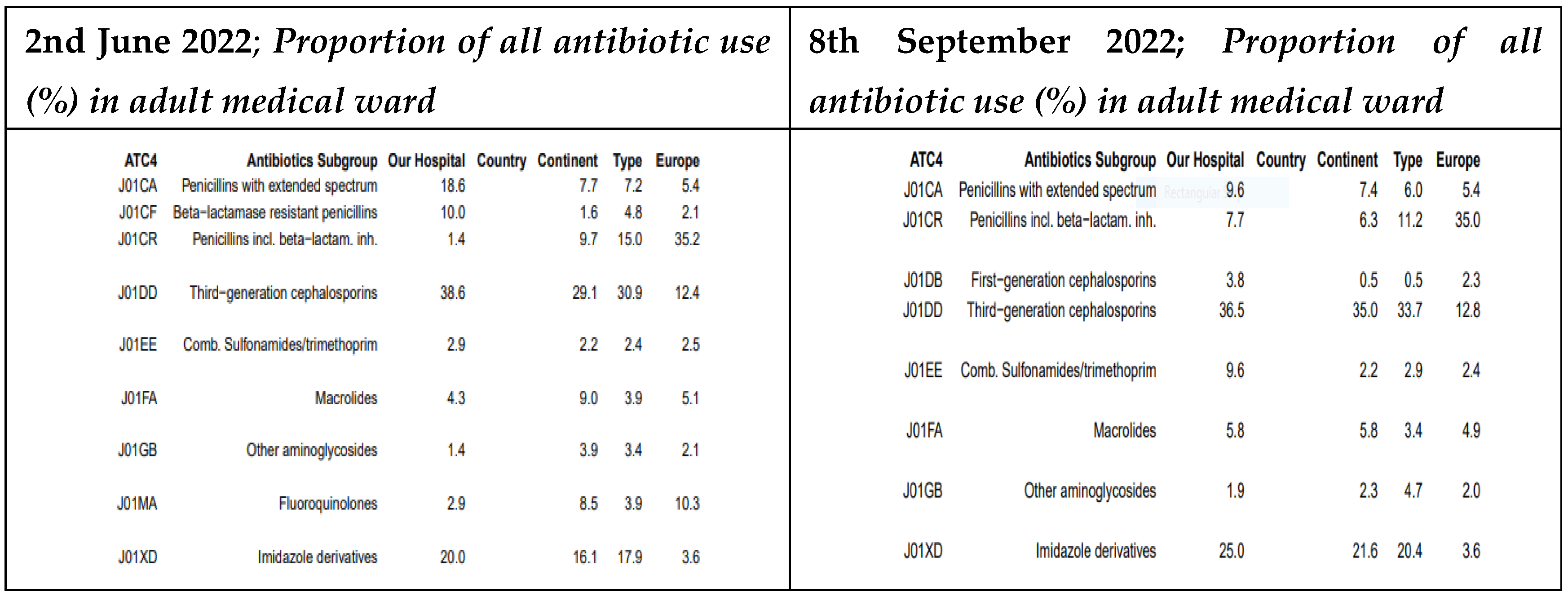

3.4. Proportional Antibiotic Use in Adult Medical Ward in the GPPS

At MRRH, between May and September 2022, the use of extended-spectrum penicillins decreased significantly from 18.6% to 9.6%. Conversely, prescriptions for penicillins with beta-lactamase inhibitors increased from 1.4% to 7.7%. Use of third-generation cephalosporins slightly declined from 38.6% to 36.5%, while fluoroquinolone prescriptions were completely discontinued (previously 2.9%). Aminoglycoside use also rose slightly, from 1.4% to 1.9% (For details see

Figure 7).

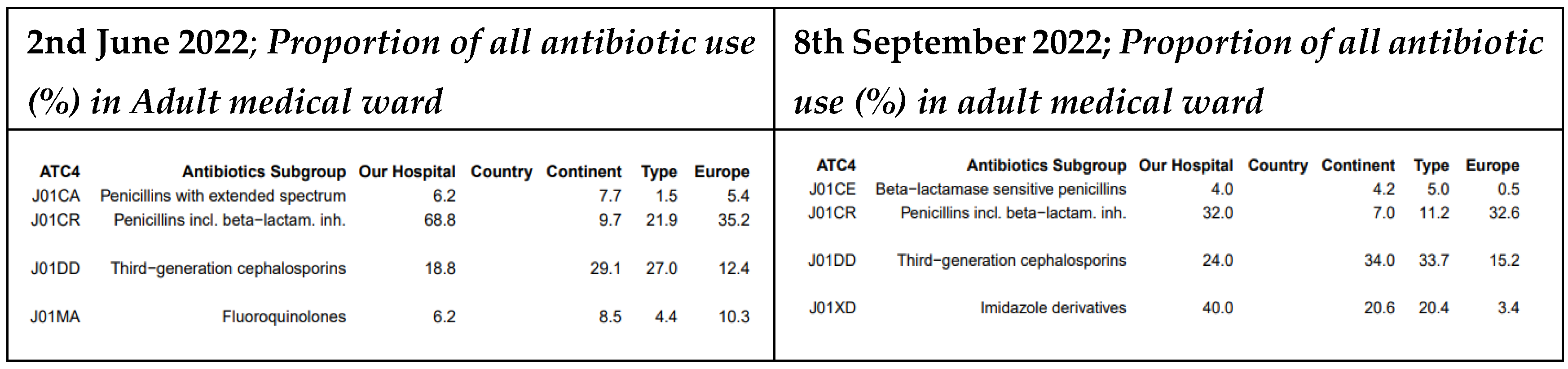

At MDDH, third-generation cephalosporin prescriptions increased from 18.8% to 24%. Fluoroquinolones were no longer prescribed (previously 6.2%), and the use of penicillins with beta-lactamase inhibitors dropped from 68.8% to 32%. In addition, prescriptions for extended-spectrum penicillins were discontinued entirely (For details see

Figure 8).

4. Discussion

This study describes the impact of continuous medical education in improving the change of practice among healthcare provider prescribers following the presentation of PPS data in Tanzania. The study has highlighted the impact of the AMS team on training, reminding and giving feedback to the prescribers in Tanzania. The study highlights the reduction of unnecessary prescription of Penicillin with extended-spectrum from 24.7% to 20.6% at MRRH. There was also a reduction of unnecessary prescriptions for third−generation cephalosporin 29.9% to 21.5%Azithromycin prescription was controlled from 8.5% to 2.8% at MRRH.

In selected conditions that need antibiotics routinely, our study found a better pattern of Access group prescriptions after the CME in both hospitals where the top 3 prescribed antibiotics changed from Watch group to Access group as recommended by the WHO [

13]. We found 1st Azithromycin, 2nd Ceftriaxone, 3rd Ceftriaxone and beta-lactamase inhibitor as the top 3 antibiotics with Gentamycin being the 1st, Ampicillin the 2nd, and a combination of penicillin the 3rd at MRRH. The was a change for the first antibiotics from Ceftriaxone to Gentamycin. Although there could be a change in the type of patients admitted in June and September 2022, we anticipate the 2 hospitals to have similar cases of patients admitted in Mbeya settings. Similar findings were reported in a cross-sectional study conducted for one year (September 2021–September 2022) at Mbeya Zonal Referral Hospital, a public hospital in the southern highlands zone of Tanzania [

24].

When studying the patterns of all prescriptions, our project provided control of the use of extended-spectrum penicillins that dropped from 24.7% to 20.6%, third-generation cephalosporins from 29.9% to 21.5% at MRRH and at MDDH, the prescription rate for third-generation cephalosporins declined from 26.8% to 19.2%, and macrolides from 5.2% to 2.8% while there was a useful guided prescription for beta-lactamase–resistant penicillins that increased from 7.2% to 9.3% during the same period and similarly recommended by Kronman and colleagues for acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs) [

25]. The study also found that fluoroquinolones were no longer prescribed for UTI and were replaced by nitrofurantoin at MDDH. These patterns urge the development of antibiograms in the hospitals of Tanzania and other sub-Saharan African countries based on AMU data mainly because hospital-wide and unit-specific antibiograms can reflect and be used to assess the relationship of ASP interventions to changes in resistance [

26]. Additionally, antibiogram is the key communication tool to clinicians and subsequent monitoring of its influence on prescribing indicators as proven in Ghana [

27].

When studying the quality indicators for prescriptions, we found an increase in quality scores for documentation of reasons for prescription, guideline compliance, and recording of stop/review dates in both hospitals for medical as well as ICU prescriptions. The surgical Unit of MDDH had a better pattern of guideline use and note recording. However, due to the low number of ICU cases at MDDH, its impact could not be assessed. This reminds us of the use of evidence for prescription as emphasized by Arcenillas and colleagues [

28]. Our quality indicators (QI) for the use of standard treatment guidelines [

29,

30] reasons in notes [

31] and review date being shown [

32] are found to be useful and applicable to clinical practice and proved useful for identifying areas with room for improvement within hospitals of Tanzania and SSA [

33].

Our study described the proportions of antibiotic use in adult medical wards for both hospitals where prescriptions for penicillins with beta-lactamase inhibitors increased from 1.4% to 7.7%. And the use of third-generation cephalosporins slightly declined from 38.6% to 36.5%, while fluoroquinolone prescriptions were completely controlled mostly for UT I[

34] (previously 2.9%). Aminoglycoside use also rose slightly, from 1.4% to 1.9% probably in the control of similar conditions but with more interest in the use of Access groups in line with the WHO AWaRe recommendations. Surprisingly, MDDH presented a confusing pattern of an increase for the third-generation cephalosporin from 18.8% to 24%, a 50% drop of penicillins with beta-lactamase inhibitors from 68.8% to 32% and colourful control of Fluoroquinolones which were no longer prescribed (previously 6.2%) [

35].

The findings in this study show that the CME interventions improved AMU in Mbeya after a close follow-up for the WHO AWaRe categorization guided by hospital-based antimicrobial use reported in the GPPS.

4.1. Limitations

Our study faced a funding limitation such that we could not study multiple hospitals in Mbeya on the same survey dates. We found a relatively smaller volume of hospitals at MDDH compared to MRRH which could raise a query as to whether the 2 hospitals are comparable.

5. Conclusions

The G-PPS guided the improvement of AMU for the selected antibiotics in the two selected hospitals. Instituting hospital AMS teams and utilizing CQI and CME methods to improve AMC and AMU should be considered countrywide to reduce AMR risks, in addition to routine monitoring through G-PPS.

6. Recommendations

Structured use of G-PPS is simply more useful in multiple antimicrobial consumption monitoring following a specific need. The G-PSS and CME guidance offers the fundamental tools for AMS teams in developing countries.

Author Contributions

BM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing-original draft, OM: Writing-review & editing. ZZJ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing. OM, TM, BNM, AN, WC, BL, EM, EB, MS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing- review & editing. OM: Data curation, Methodology, Writing-review & editing. FFI, CM: Writing-original draft, data analysis, Writing-review & editing, EN: Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing. BM, OM, TM, ZZJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing-original draft, Writing- review & editing.

Funding

This study was initially supported by the CWPAMS 2.0 for the data collection on GPPS by the University of Dar es Salaam in Mbeya that was later on supported by the Henry Jackson Foundation Medical Research International HJRMRI as a special public health activity under the supply chain and local partners engagement for AMR in Mbeya, Tanzania.

Acknowledgments

The investigators and collaborators of UDSM-MCHAS and HJFMRI wish to declare special gratitude to the management of Mbeya Regional Referral Hospital (Mbeya RRH) and Mbalizi Designated District Hospital (Mbalizi DDH) Southern Highlands of Tanzania, Special memory to the late Prof Eva Muro, the professor of Pharmacology at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College KCMUCo for providing a link and support of UDSM-MCHAS from CWPAMS through KCMUCo.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399:629–55. [CrossRef]

- Durrance-Bagale A, Jung AS, Frumence G, et al. Framing the drivers of antimicrobial resistance in Tanzania. Antibiotics. 2021;10:991. [CrossRef]

- Kazemian H, Heidari H, Ghanavati R, et al. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of ESBL-, AmpC-, and Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli Isolates. Med Princ Pract. 2019;28:547–51. [CrossRef]

- Mshana SE, Matee M, Rweyemamu M. Antimicrobial resistance in human and animal pathogens in Zambia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique and Tanzania: An urgent need of a sustainable surveillance system. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2013;12:28. [CrossRef]

- Buname G, Kiwale GA, Mushi MF, et al. Bacteria Patterns on Tonsillar Surface and Tonsillar Core Tissue among Patients Scheduled for Tonsillectomy at Bugando Medical Centre, Mwanza, Tanzania. Pathogens. 2021;10:1560. [CrossRef]

- Karaiskos I, Giamarellou H. Carbapenem-Sparing Strategies for ESBL Producers: When and How. Antibiotics. 2020;9:61. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins C, Ulenga N, Liu E, et al. HIV virological failure and drug resistance in a cohort of Tanzanian HIV-infected adults. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:1966–74. [CrossRef]

- Kosiyaporn H, Chanvatik S, Issaramalai T, et al. Surveys of knowledge and awareness of antibiotic use and antimicrobial resistance in general population: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0227973. [CrossRef]

- WHONET. The microbiology laboratory database software. WHONET Version 21.16.12. 2022. https://whonet.org/ (accessed 12 February 2022).

- WHO. GLASS report: early implementation 2016-2017. Glob Antimicrob Resist Surveill Syst. Published Online First: 2018.

- WHO Euro. Tailoring Antimicrobial Resistance Programmes (TAP). Copenhagen, Denmark 2019.

- Avent ML, Cosgrove SE, Price-Haywood EG, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship in the primary care setting: From dream to reality? BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21:134. [CrossRef]

- USAID. A Technical Guide to Implementing the World Health Organization ’ s AWaRe Antibiotic Classification in MTaPS Program Countries. 2019;1–7.

- C Reygaert W. An overview of the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of bacteria. AIMS Microbiol. 2018;4:482–501. [CrossRef]

- Hurt CB, Eron JJ, Cohen MS. Pre-exposure prophylaxis and antiretroviral resistance: HIV prevention at a cost? Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1265–70. [CrossRef]

- Weis JF, Baeten JM, et al. PrEP-selected Drug Resistance Decays Rapidly After Drug Cessation. Physiol Behav. 2016;30:31–5. [CrossRef]

- Boffito M, Waters L, Cahn P, et al. Perspectives on the Barrier to Resistance for Dolutegravir + Lamivudine, a Two-Drug Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV-1 Infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2020;36:13–8. [CrossRef]

- Moirongo RM, Lorenz E, Ntinginya NE, et al. Regional Variation of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL)-Producing Enterobacterales, Fluoroquinolone-Resistant Salmonella enterica and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Among Febrile Patients in Sub-Saharan Africa. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Thakkar K, Gilchrist M, Dickinson E, et al. A quality improvement programme to increase compliance with an anti-infective prescribing policy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1916–20. [CrossRef]

- Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, et al. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:290–8. [CrossRef]

- Goossens H, Vlieghe E, Versporten A, et al. Global Point Prevalence Survey (GLOBAL-PPS). Global-PPS. 2023.

- Pauwels I, Versporten A, Vermeulen H, et al. Assessing the impact of the Global Point Prevalence Survey of Antimicrobial Consumption and Resistance (Global-PPS) on hospital antimicrobial stewardship programmes: results of a worldwide survey. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2021;10:138. [CrossRef]

- Wiedenmayer K, Ombaka E, Kabudi B, et al. Adherence to standard treatment guidelines among prescribers in primary healthcare facilities in the Dodoma region of Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:1–10. [CrossRef]

- Nsojo A, George L, Mwasomola D, et al. Prescribing patterns of antimicrobials according to the WHO AWaRe classification at a tertiary referral hospital in the southern highlands of Tanzania. Infect Prev Pract. 2024;6:100347. [CrossRef]

- Kronman MP, Gerber JS, Grundmeier RW, et al. Reducing Antibiotic Prescribing in Primary Care for Respiratory Illness. Pediatrics. 2020;146. [CrossRef]

- Schulz LT, Fox BC, Polk RE. Can the antibiogram be used to assess microbiologic outcomes after antimicrobial stewardship interventions? A critical review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32:668–76. [CrossRef]

- Dakorah MP, Agyare E, Acolatse JEE, et al. Utilising cumulative antibiogram data to enhance antibiotic stewardship capacity in the Cape Coast Teaching Hospital, Ghana. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2022;11:122. [CrossRef]

- Arcenillas P, Boix-Palop L, Gómez L, et al. Assessment of Quality Indicators for Appropriate Antibiotic Use. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Antimicrobial stewardship programmes in health-care facilities in low- and middle-income countries: a WHO practical toolkit. JAC-Antimicrobial Resist. 2019;1. [CrossRef]

- Mbwele B, Slot A, De Mast Q, et al. The use of guidelines for lower respiratory tract infections in Tanzania: A lesson from Kilimanjaro clinicians. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2016;6:100. [CrossRef]

- Aronson JK. Ten principles of good prescribing. Oxford Univ.—Cent. Evidence-Based Med. (CEBM). 2024. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/top-tips/ten-principles-of-good-prescribing# (accessed 20 April 2025).

- Birchwood Medical Practice. Medication Reviews. NHS Birchwood Med. Pract. 2024. https://www.birchwoodbristol.nhs.uk/health-information/medrevpatlflt/#: (accessed 20 April 2025).

- March-López P, Madridejos R, Tomas R, et al. Applicability of Outpatient Quality Indicators for Appropriate Antibiotic Use in a Primary Health Care Area: a Point Prevalence Survey. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64. [CrossRef]

- Al Lawati H, Blair BM, Larnard J. Urinary Tract Infections: Core Curriculum 2024. Am J kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. 2024;83:90–100. [CrossRef]

- Mahdizade Ari M, Dashtbin S, Ghasemi F, et al. Nitrofurantoin: properties and potential in treatment of urinary tract infection: a narrative review. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1148603. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).