1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global health threat with alarming projections for the future [

1]. By 2050, it is estimated that infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria will surpass cancer as the leading cause of death worldwide [

2]. Italy, in particular, faces some of the highest levels of resistance for critical pathogens like

Klebsiella pneumoniae and

Escherichia coli. The country bears one of the heaviest burdens of AMR in Europe, with over 10,000 deaths annually attributed to resistant infections—accounting for more than a third of all AMR-related deaths in the EU. Developing robust antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) programs in hospitals is critical to addressing this issue [

3]. However, it is equally important to focus on primary care settings, where 90% of antibiotic prescriptions are made, with two-thirds originating from primary care physicians. This makes primary care a key area for AMS initiatives aimed at optimizing antibiotic use and preventing the spread of resistance [

4].

National Action Plans (NAPs) for AMR can serve as a crucial tool in shaping national strategies to combat this growing threat [

5]. These plans provide a structured framework for addressing AMR across various sectors, promoting collaboration between healthcare, veterinary, and environmental systems. However, as highlighted in various studies, the existence of NAPs alone is not sufficient to ensure success [

6]. In Italy, the first national plan was introduced with the National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance 2017-2020 (updated in 2022), along with its related surveillance system, SPiNCAR (Surveillance and Prevention of Healthcare-Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance), aimed at monitoring the implementation of the NAP [

8,

9].

The Italian National Health Service is a decentralized public system with three levels: central, regional, and local. While the national government sets overall health policies and standards, the 21 regions and autonomous provinces have significant autonomy in managing healthcare services. Each region is governed by elected officials who oversee healthcare delivery through hospital trusts and Local Health Authorities (LHAs). LHAs are responsible for providing healthcare within a defined geographic area. They are managed by General Managers appointed at the regional level and are further divided into Local Health Units (LHUs), which integrate hospital and community-based services. Major hospitals often operate as semi-independent public entities known as 'public hospital enterprises' or specialized hospitals [

10]. In the Veneto region, north-east of Italy, there are 9 LHAs and 3 specialized hospitals. The 9 LHAs vary in size, with populations ranging from 300,000 to nearly 1 million. The community area of each LHA is divided into one or more territorial areas, each with its own director [

11]. Primary care within LHAs is provided by a network of general practitioners, who act as gatekeepers to higher levels of care. Home care services, less complex than those provided in hospitals, are delivered either at the patient's home or in nursing homes. The Community Hospital is a healthcare facility with 20 beds per 100,000 inhabitants, designed for patients requiring short-term, low intensity care [

12].

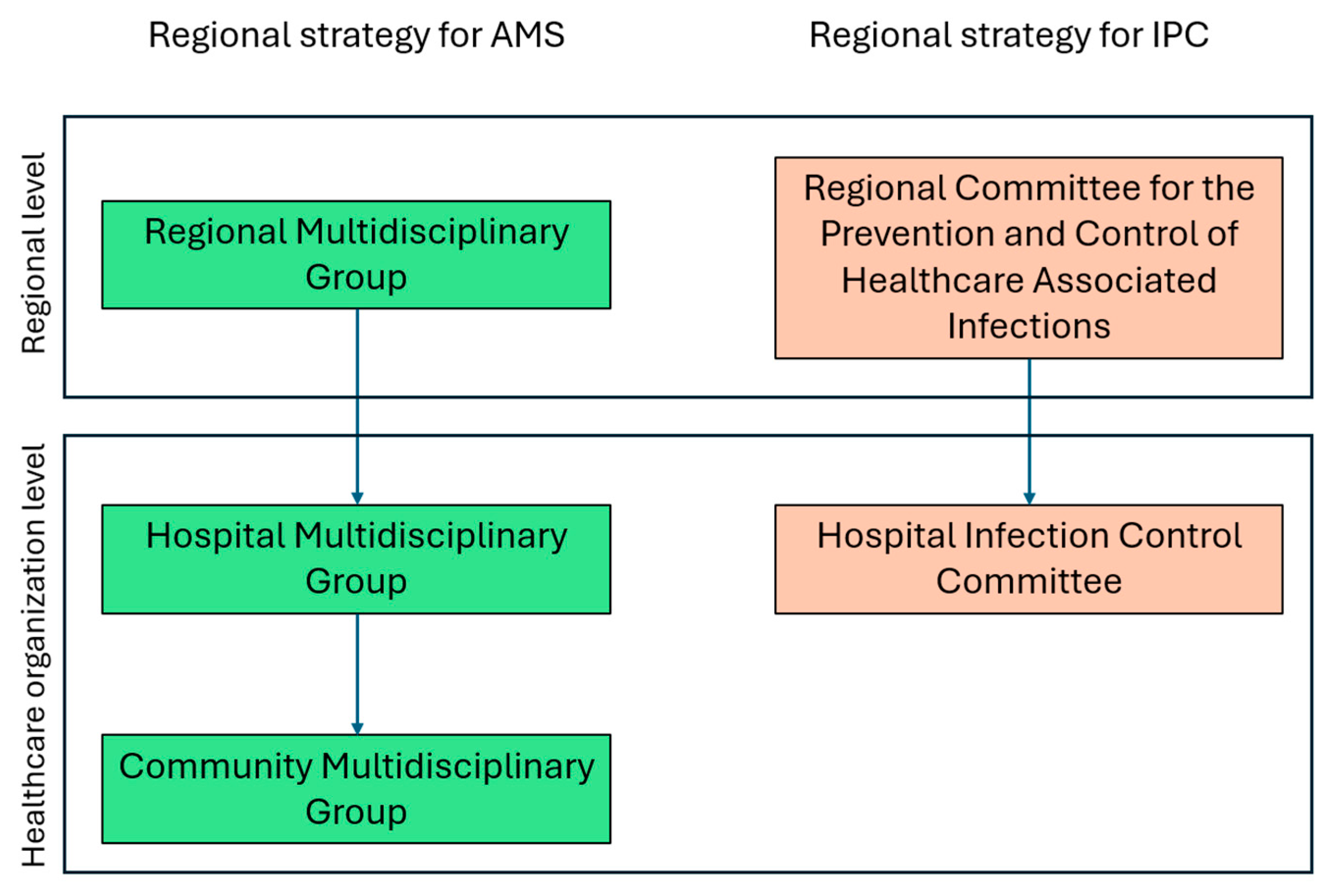

In the Veneto Region the first NAP was adopted in 2019 through a regional decree, which outlined strategies for the proper use of antibiotics in human health and introduced a regional plan for the surveillance, prevention, and control of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). The Veneto Region's strategy for antimicrobial use includes a comprehensive governance structure for AMS, divided into three levels: the Regional Multidisciplinary Group at the regional level, the Hospital Multidisciplinary Group at the hub hospitals, and the Community Multidisciplinary Group in territorial health organizations, managing AMS activities at community level [

13]. Additionally, the governance model for Infection Prevention and Control (IPC), mandates the establishment of the Hospital Infection Control Committee, chaired by the hospital medical director, to oversee infection control measures. Additionally, a regional coordinating committee ensures alignment and consistency across all healthcare settings, both hospital-based and community-based (

Figure 1) [

14]. The plan for the surveillance, prevention, and control of HAIs also introduced the role of Link Professionals, healthcare professionals (e.g., nurses, technicians, doctors, etc.) who play a leadership role within their facility on infection risk-related matters [

15].

This paper presents the findings of the ARCO project (Approcci di Rete per il Contrasto all’Antimicrobico Resistenza Ospedale-Territorio - Network Approaches for Combating Antimicrobial Resistance between Hospital and Community), developed through collaboration among three scientific societies: ANMDO (National Association of Hospital Medical Management), SIFACT (Italian Society of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics), and CARD (Confederation of Regional District Associations). The ARCO working group includes a multidisciplinary team from various healthcare organizations in the Veneto Region, comprising hospital medical directors, hospital pharmacists, infection risk specialists, primary care pharmacists, and coordinators in integrated home care and district functions. The primary objective of the ARCO project is to evaluate the implementation of regional governance models for IPC and AMS across healthcare organizations in the Veneto Region. Additionally, the project involves analyzing data from a focus group of key stakeholders and experts to gain a deeper understanding of current AMS and IPC practices. This analysis will help identify best practices and areas for improvement, contributing to the refinement of AMS and IPC strategies within the region.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Design and Distribution.

A cross-sectional survey was conducted to evaluate adherence to regional governance models for IPC and AMS and to explore the integration between hospital and community care settings. The ARCO working group developed four distinct questionnaires targeting Hospital Medical Management (HMM), District Health Management (DHM), Hospital Pharmacies (HP), and Primary Care Pharmaceutical Department (PCPD). The survey collected information on staffing levels for AMS-related activities (pharmacists, nurses, and physicians), the existence and functioning of AMS programs, training on AMR and AMS, and reporting practices related to antibiotic consumption, protocol adherence, and surveillance data. The survey also explored how healthcare units implemented governance models and the level of coordination between hospital and community settings. The questionnaires were distributed electronically to healthcare units across the Veneto region, supported by a joint communication from the Regional Directorate of Pharmaceutical Services and Medical Devices and the Directorate of Prevention and Food Safety. Responses were collected through Google Forms between November 3 and November 11, 2023, from HMM, DHM, HP, and PCPD. The data collected were analyzed using descriptive statistics in Microsoft Excel.

2.2. Focus Group.

Following the data analysis, a focus group was organized on May 10, 2024, to further interpret the survey results. The participants included members of the ARCO working group, two representatives from the regional directorates, and a panel of experts composed of three infectious disease specialists, a microbiologist, and a hospital hygienist. The discussion centered around three main themes: professional commitment, including staffing and AMS committees; audit and reporting practices; and IPC activities. The focus group discussion provided deeper insights into the current state of AMS implementation in the Veneto region, highlighting strengths and identifying areas for improvement within both hospital and community healthcare settings. This moment of confrontation resulted in statements with the aim of improving practices at the regional level.

3. Results

The survey was completed by healthcare professionals, starting with 21 HMM that represented 34 hospital facilities. These included 26 spoke hospitals, 2 highly specialized hospitals, 4 hub hospitals, and 2 university hospitals, accounting for a total of 12,115 beds. This response represented 100% of the healthcare organizations in the region. Additionally, 22 DHM participated, covering 22 healthcare districts. These districts provide healthcare services to a total of 4,133,010 residents, out of a total population of 4,906,000, also representing 100% of the region’s healthcare organizations. Among HP, 16 out of a total of 19 participated, representing 100% of the healthcare organizations in the region. Lastly, 8 PCPD out of a total of 9 responded, representing 89% of the community pharmacies and healthcare organizations in the region, with one community pharmacy per healthcare organization.

3.1. Governance and Organizational Structure

According to HMM, three out of four healthcare organizations reported having a formalized annual plan for IPC. Additionally, one out of two organizations indicated having a formalized antimicrobial stewardship plan in place.

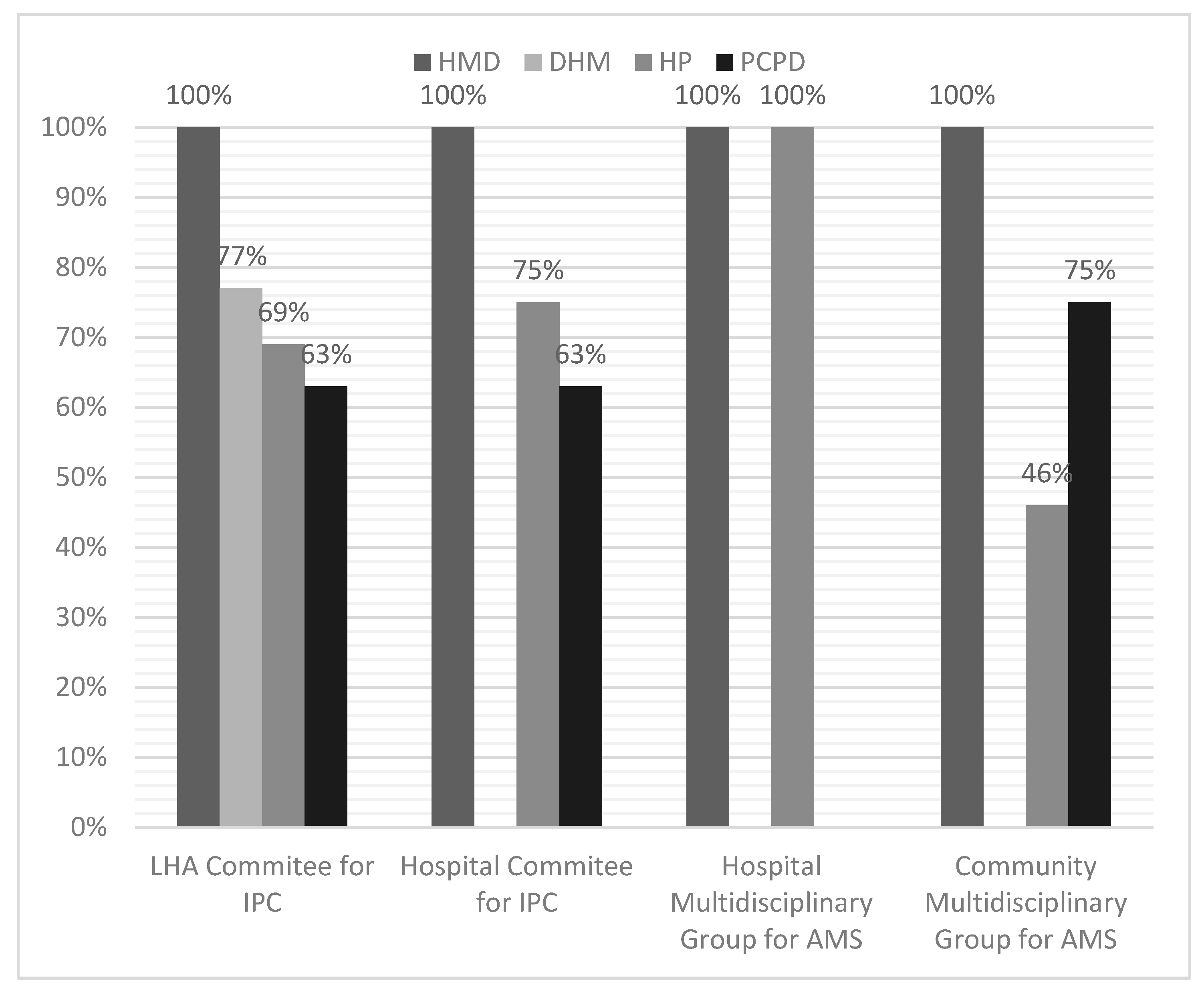

Each respondent could report his or her knowledge in terms of the activation of various company or local committees active in the area of AMS and IPC. These include LHA Committee for IPC, Hospital-based Committee for IPC, Hospital Multidisciplinary Group for AMS, Community Multidisciplinary Group for AMS. All HMM reported that the required committees had been formally established, whereas the other corporate divisions did not provide the same response (

Figure 2), even within the same healthcare organization.

3.2. Human Resources and Link Professional for AMS and IPC

Table 1 presents the allocation of human resources (nurses, physicians and pharmacists) dedicated to IPC and AMS programs across hospital and community care settings. In hospitals, there were 19 fully dedicated infection control nurses (0.25 per 100 beds) and 12 partially dedicated nurses (0.01 per 100 beds). Six public health specialists were fully dedicated (0.04 per 100 beds), while 28 were partially dedicated (0.01 per 100 beds). Hospital pharmacists had only one fully dedicated professional (0.004 per 100 beds), with 16 partially dedicated pharmacists (0.56 per 100 beds).

In community settings, no pharmacists were fully dedicated, though 12 were partially involved (0.004 per 1,000 inhabitants). In primary care, no nurses or physicians were fully dedicated to AMS/IPC programs, but 21 nurses (0.008 per 1,000 inhabitants) and 33 physicians (0.009 per 1,000 inhabitants) were partially involved. Similarly, in community hospitals, no fully dedicated staff were reported, but 41 nurses (6.2 per 100 beds) and 22 physicians (0.10 per 100 beds) were partially involved. In domiciliary care, no fully dedicated staff were present, but 21 nurses (0.022 per 1,000 inhabitants) and 18 physicians (0.005 per 1,000 inhabitants) were partially involved in IPC/AMS activities.

Table 2 provides data on the identification, training, and involvement of Link Professionals in IPC and AMS programs across both hospital and community settings. In hospitals, 76% of link professionals are formally identified, whereas only 36% are formally identified in community settings, with 50% of link professionals in the community not identified at all.

Regarding training, 33% of hospital-based link professionals have received dedicated IPC training, while 48% have participated in non-specific programs, and 19% have not undergone any training. In community settings, these figures are lower: 18% have received dedicated training, 73% have attended non-specific programs, and 9% have not received any training. Link professionals are involved across a range of services. In hospitals, they are present in inpatient wards (100%), emergency departments (86%), operating theaters (81%), and diagnostic imaging services (71%). They also contribute to outpatient services (67%) and day care activities (48%). In community settings, link professionals are primarily engaged in primary care (91%), integrated home care (55%), intermediate care facilities (36%), and residential facilities (36%). The objectives assigned to link professionals vary significantly between hospital and community settings. In hospitals, 76% are involved in training and promoting best practices, 62% participate in HAI reporting, and 52% utilize checklists to ensure IPC measures are followed. In community settings, similar activities are observed, with 82% participating in HAI reporting and 55% focusing on best practices promotion. However, the formalization of these objectives remains limited, with only 10% of hospital-based and 9% of community-based link professionals having formalized, monitored objectives with shared outcomes.

3.3. Infectious Disease (ID) Consultation Services

The survey results indicate that 75% of healthcare organizations have an infectious disease ward, typically located in hub hospitals. Additionally, three out of 12 organizations have established agreements with other institutions to provide infectious disease consultations, while three have hired infectious disease specialists on a freelance basis. Five organizations reported employing infectious disease specialists in departments outside of the infectious diseases unit, ranging from one to three professionals. These specialists are employed in diverse areas, including two in medical management, two in geriatrics, one in internal medicine, and one in pediatrics. This highlights the varied organizational approaches to securing infectious disease expertise across healthcare settings.

As shown in table 3, we highlight the variability in the availability of ID consultation services across healthcare settings. Approximately 5% of facilities reported no access to ID consultation, while the majority have some level of availability. Specifically, 29% of the settings offer consultation services between 1 to 3 days per week, and another 29% provide services for 4 to 5 days. Notably, 38% of settings offer near-daily access, with ID consultation available 6 to 7 days per week. In terms of the number of hours per week that ID consultation is available, nearly half of the healthcare settings (48%) provide access for up to 20 hours per week, while only 14% offer services for 21 to 30 hours per week. Twenty-four percent of the settings report availability for 31 to 70 hours per week. Continuous, around-the-clock consultation (168 hours per week) is available in 14% of healthcare facilities.

3.4. Analysis of Antibiotic Consumption Reports and Indicators in Hospitals and Primary Care Settings

The analysis highlights several key points in the reporting of antibiotic consumption across hospital and primary care settings (

Table 4). In hospital reports, almost all (94%) included economic indicators such as expenditure for ATC category J01, while 63% included quantitative indicators measuring consumption in dosage units or pieces. Notably, 75% of hospital reports also incorporated quantitative indicators expressed in Defined Daily Dose (DDD) and qualitative indicators through the AWaRe classification. However, only 25% of the reports included ESAC indicators, showing limited attention to European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption.

In comparison to hospitals, primary care reports demonstrated a lower use of quantitative indicators expressed in DDD (38% versus 75%). However, there was a significant reliance on indicators that measure the number of patients treated, observed in 50% of primary care reports. Similarly, the qualitative AWaRe classification was present in 63% of primary care reports compared to 75% in hospitals, while none of the primary care reports included ESAC indicators.

In terms of infection management guidelines, 38% of primary care reports addressed upper respiratory, lower respiratory, and lower urinary tract infections, with a smaller percentage (13%) covering soft tissue infections.

3.5. Focus Group Recommendations

The focus group provided a series of detailed recommendations aimed at improving AMS and IPC programs across various healthcare settings. These recommendations, summarized in

Table 5, cover key areas such as governance, human resources, link professionals, infectious disease consultation services, and antibiotic consumption reporting in hospitals and primary care. The group emphasized the importance of tailoring AMS and IPC objectives to the specific needs of healthcare organizations, ensuring these goals are incorporated into senior leadership performance evaluations. Additionally, there was a strong emphasis on improving resource allocation, providing standardized training, and formally recognizing link professionals, especially in community settings where these roles are underdeveloped. The focus group also highlighted the need to expand infectious disease consultation services in both spoke hospitals and community care settings to provide continuous support for AMS activities, rather than relying on ad-hoc consultations. These recommendations aim to address existing gaps in resources and governance structures, ensuring a more cohesive and effective approach to AMS and IPC implementation

4. Discussion

National action plans are useful but not sufficient for the effective implementation of AMS and IPC measures [

5]. The aim of our project was to collect data through surveys and, following a focus group discussion, to identify best practices and approaches within HCAs that could be integrated into regional and local plans.

The ARCO project gathered expert recommendations to strengthen governance within HCAs and enhance leadership commitment by defining clear objectives and allocating resources to incentivize AMS program implementation. Broom et al. highlighted the challenge of prioritizing long-term public health goals, such as AMR, over short-term performance-driven objectives, underscoring the need for clearly defined, long-term objectives aligned with AMS goals to ensure accountability and sustained leadership commitment [

16]. Similarly, Jeleff et al. emphasized that AMS compliance must go beyond formal documentation to include meaningful resource allocation and concrete actions that drive real improvements [

17]. Further recommendations focused on strengthening local and regional governance. Regional and local AMR committees can tailor interventions to local needs, better aligning efforts with regional epidemiological contexts. These committees foster collaboration across hospitals and community settings, enabling quicker responses to resistance trends [

6,

18]. However, localized approaches also present challenges, such as the risk of fragmentation and duplicated efforts due to overlapping roles [

16]. To address this, minimum operational standards should be established, such as regional toolkits accessible to healthcare professionals, modeled after the AMS Toolkit TARGET and Start Smart Then Focus from the UK NHS [

19]. These toolkits should include content for implementation and indicators for organizational plans, ensuring consistent standards across all settings. Additionally, investment in communication and transparency is crucial, ensuring that all healthcare professionals are informed about existing committees and medium- to long-term plans, with key information made accessible via the organization's website.

Our work focuses on the human resources necessary for effective AMS and IPC programs, highlighting the critical importance of adequate staffing for their success and sustainability. Our findings reveal an average of 0.25 IPC nurses and 0.04 IC physicians per 100 beds, which aligns with the national ratio for nurses but falls short of European data, where the average is 0.80 IPC nurses and 0.15 physicians per 100 beds [

20,

21]. Italian guidelines from 1980 recommend 0.25–0.4 IPC nurses and 0.1 physicians per 100 beds, while the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control has recently updated its guidelines to recommend 1 IPC nurse per 100 beds, reflecting the increasing need for specialized personnel [

22,

23]. Where national standards are lacking—such as in HP, PCPD, and community healthcare—dedicated personnel are often absent. Our study found a ratio of 0.004 HP per 100 beds, significantly lower than the European average of 0.1221. Several guidelines suggest that a ratio of 1 HP per 100 beds is necessary for effective clinical pharmacy services, particularly in AMS programs [

24,

25,

26]. The lack of clear roles and organizational structures, especially in community settings, underscores the need for standardized human resource allocation for AMS and IPC programs.

Expanding services and appointing permanent AMS reference figures in primary care would provide the leadership needed to integrate AMS into routine clinical practice, shifting from ad-hoc consultations to continuous support and improving antimicrobial management. The shortage of ID consultation services, especially in spoke hospitals and community settings, further hinders AMS and IPC implementation. A study from another northeastern Italian region found that for a population of 312,000, an AMS program required 4 full-time infectious disease consultants, 0.9 FTE microbiologists, and 0.9 FTE pharmacists, alongside an IPC team [

27]. In the Veneto region, larger healthcare organizations, and the absence of central hub hospitals in some areas, require adjusted staffing models, emphasizing the need for tailored strategies to support AMS and IPC efforts.

Link Professionals are crucial to the success of IPC programs. To ensure these roles are valued and supported, a formal system of recognition and incentives is essential. This echoes findings by Jeleff et al., who emphasize the importance of both financial and symbolic recognition for professionals engaged in AMS. Without adequate remuneration and career incentives, attracting and retaining skilled personnel in these critical roles becomes challenging [

17]. Establishing an annual, structured training curriculum would ensure that link professionals, particularly in community settings, are fully equipped to promote best practices, ensure proper surveillance, and implement infection control policies [

28]. Formalizing the objectives assigned to link professionals and creating a system of regular performance monitoring would further enhance their impact, fostering commitment and accountability across the healthcare organization.

The survey highlights the need for standardized antibiotic consumption reporting across hospitals and primary care. Primary care reports often emphasize economic indicators rather than clinical metrics like DDD or the AWaRe classification. The focus group recommended standardizing reports to include both economic and clinical data for a comprehensive understanding of antibiotic use. Additionally, specific prescribing guidelines for primary care are necessary to reduce inappropriate antibiotic use. The ARCO Project also identified gaps in monitoring and reporting adherence to AMS and IPC protocols in the Veneto Region. Implementing standardized indicators and transparent reporting, like the governance model in England, could improve accountability, enhance performance tracking, and foster a more consistent approach to stewardship across the region [

29].

The focus group reminded the long-standing problem of the application of European Privacy Regulation in Italy, that often represent a barrier to share data between health authorities and interconnection of health informational flows. Quality of data is fundamental to guarantee efficacious health systems governance and disease prevention and control, especially as regards field epidemiology and, consequently, management of HAI and AMR, since these are issues that distress across different healthcare services and spread without taking in account territorial boundaries [

30].

The ARCO project may seem similar to SPiNCAR, the tool used to monitor the implementation of the Italian NAP [

9]. However, while SPiNCAR focuses on assessing the application of Italian’s NAP within HCAs, it does not examine internal organizational models, resource allocation, or regional strategies for managing AMS and IPC. Furthermore, the ARCO project aims to provide a broader perspective by incorporating insights from a wider range of professionals and offering a more detailed analysis of resource allocation and organizational structures. Therefore, results from SPiNCAR and ARCO could be integrated to provide a more comprehensive and multi-faceted approach to governance for AMS and IPC across different levels of the Regional Health Service.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide a comprehensive understanding of HCAs' perspectives and actionable measures by combining survey data with focus group insights to identify best practices and areas for improvement. Previous studies have assessed AMS activities through surveys in community healthcare organizations, interviews with hospital managers, or by examining the perspectives of key experts and stakeholders involved in AMR policy [

16,

17,

19]. However, no previous study has undertaken such a thorough contextual analysis, administering questionnaires across various structures within local healthcare organizations and subsequently gathering expert recommendations on organizational context, along with insights from regional leadership, in a regional audit approach.

Nevertheless, the study is not without its limitations. A significant challenge is the reliance on self-reported data from healthcare organizations, which could introduce reporting biases [

31]. Furthermore, while the study offers valuable insights specific to the Veneto Region, its findings may not be fully generalizable to other regions due to variations in healthcare structures and challenges. Despite these limitations, the study provides actionable insights for optimizing AMS and IPC plans, contributing meaningfully to the broader goal of combating antimicrobial resistance.

In conclusion, while significant progress has been made in establishing governance frameworks for AMS and IPC in the Veneto Region, targeted operational improvements are essential for healthcare units to fully realize the potential of these programs. Strengthening unified governance structures, standardizing antibiotic consumption reports, expanding infectious disease consultation services, and ensuring adequate staffing are critical steps to enhancing the region’s response to antimicrobial resistance. The ARCO project provides a valuable foundation for these efforts, offering actionable recommendations that will be key to driving sustained improvements across both hospital and community care settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A., D.M., U.G., R.R., M.M., M.C., S.M., M.P. and S.V.; methodology, P.A. and D.M..; validation, U.G., R.R., M.M., M.C., S.M., M.P. and S.V.; formal analysis, P.A.; investigation, P.A., D.M., U.G., R.R., M.M., M.C., S.M., M.P. and S.V.; resources, V.B., G.S., F.R., R.C.; data curation, P.A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.F., P.A., D.M.; writing—review and editing, V.M., A.M., P.D.A., D.G., M.T.; visualization, all authors; supervision, V.B., G.S., F.R., R.C.; project administration, P.A., D.M..; funding acquisition, not pertinent. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript..

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Claudia Scardina, Matteo Centomo, and Andrea Basso from the Department of Cardiac, Thoracic, and Vascular Sciences and Public Health at the University of Padua for their support in the preliminary stages of the project and in the initial data analysis. Special thanks to Samuele Gardin and Lolita Sasset, Infectious and Tropical Diseases Unit, AOUPD. We also extend our gratitude to Maria Silvia Varalta from the Health Programming Directorate; Marco Milani from the Regional Directorate of Prevention, Food Safety, Veterinary, Public Health-Veneto Region; and Serena Matteazzi and Francesco Cobello from FSSP (Fondazione Scuola di Sanità Pubblica, Regione Veneto). Finally, we would like to thank Gianfranco Finzi, President of ANMDO (National Association of Hospital Medical Directors).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Antimicrobial resistance 2020. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- O’Neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. Wellcome Trust and HM Government. 2016. Available online : https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160525_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf. (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Cassini A, Högberg LD, Plachouras D, et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: a population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2019, 19, 56–66. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco – AIFA). The Medicines Utilisation Monitoring Centre. National Report on Medicines use in Italy. Year 2022. 2023. Available online: https://www.aifa.gov.it/en/rapporti-osmed (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/global-action-plan/en/ (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Willemsen A, Reid S, Assefa Y. A review of national action plans on antimicrobial resistance: strengths and weaknesses. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2022, 11, 90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of health, Italy. National action plan on antibiotics resistance 2017-2020. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/italy-national-plan-against-antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Ministry of health, Italy. National action plan on antibiotics resistance 2022-2025. 2022. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_3294_allegato.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Bravo G, Cattani G, Malacarne F, et al. SPiNCAR: A systematic model to evaluate and guide actions for tackling AMR. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0265010. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferre F, de Belvis AG, Valerio L, et al. Italy: health system review. Health Syst Transit 2014, 16, 1–168.

- Veneto Region. Regional Law No 19 of October 25, 2016. Establishment of the governance body for regional healthcare in Veneto, called “Azienda per il governo della sanità della Regione del Veneto - Azienda Zero.” Provisions for defining the new territorial areas of the ULSS Companies”. 2016. Available online: https://www.consiglioveneto.it/web/crv/dettaglio-legge?catStruttura=LR&anno=2016&numero=19&tab=storico (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Mauro M, Giancotti M. The 2022 primary care reform in Italy: Improving continuity and reducing regional disparities? Health Policy. 2023, 135, 104862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veneto Region. Regional Decree of Veneto Region No. 1402 of October 1, 2019. “National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance (PNCAR) 2017-2020.” Approval of the documents titled “Veneto Region Strategy for the Proper Use of Antibiotics in Human Health” and “Regional Plan for the Surveillance, Prevention, and Control of Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs).” 2019. Available online: https://bur.regione.veneto.it/BurvServices/Pubblica/DettaglioDgr.aspx?id=404556 (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Veneto Region., Regional Decree of Veneto Region No. 1912 of December 21, 2018. “Update of the Regional Committee for the Prevention and Control of Healthcare-Associated Infections, within the framework of the National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance (PNCAR) 2017-2020, and the Hospital Infection Control Committee (CIO)”. 2018. Available online : https://bur.regione.veneto.it/BurvServices/pubblica/DettaglioDgr.aspx?id=418279#:~:text=1912%20del%2021%20dicembre%202018,specialista%20in%20malattie%20infettive%20all'. (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- Dawson, SJ. The role of the infection control link nurse. J Hosp Infect. 2003, 54, 251–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broom A, Kenny K, Kirby E, et al. The modern hospital executive, micro improvements, and the rise of antimicrobial resistance. Soc Sci Med 2021, 285, 114298. [CrossRef]

- Jeleff M, Haddad C, Kutalek R. Between Superimposition and Local Initiatives: Making Sense of ‘Implementation Gaps’ as a Governance Problem of Antimicrobial Resistance. SSM - Qualitative Research in Health 2023, 100332. [CrossRef]

- Howard P, Pulcini C, Levy Hara G, et al. An international cross-sectional survey of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015, 70, 1245–1255. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashiru-Oredope D, Budd EL, Bhattacharya A, et al. Implementation of antimicrobial stewardship interventions recommended by national toolkits in primary and secondary healthcare sectors in England: TARGET and Start Smart Then Focus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016, 71, 1408–1414. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Società Scientifica Nazionale Infermieri Specialisti Rischio Infettivo (ANIPIO). Le Infezioni Correlate all’Assistenza (ICA): una pandemia silente. Roma: Ufficio Stampa e Comunicazione Federazione nazionale degli ordini delle professioni infermieristiche; 2021.

- Dickstein Y, Nir-Paz R, Pulcini C, et al. Staffing for infectious diseases, clinical microbiology and infection control in hospitals in 2015: results of an ESCMID member survey. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016, 22, 812.e9–812.e17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italian Ministry of Health. Circular of the Ministry of Health No. 8/1988: Fight against hospital infections: surveillance. 1988.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Point prevalence survey of healthcare associated infections and antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals. 2024. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/PPS-HAI-AMR-acute-care-europe-2022-2023 (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE Jr, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007, 44, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciccarello C, Leber MB, Leonard MC, et al. ASHP Guidelines on the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee and the Formulary System. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021, 78, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polidori P, Leonardi Vinci D, Adami S, Bianchi S, Faggiano ME, Provenzani A. Role of the hospital pharmacist in an Italian antimicrobial stewardship programme. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2022, 29, 95–100. [CrossRef]

- Del Fabro G, Venturini S, Avolio M, et al. Time is running out. No excuses to delay implementation of antimicrobial stewardship programmes: impact, sustainability, resilience and efficiency through an interrupted time series analysis (2017-2022). JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2024, 6, dlae072. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Bò O, Fabro R, Faruzzo A, et al. Link Professional: Training Project for Reduction of healthcare-associated infections. GIMPIOS 2017, 7, 125–33. [CrossRef]

- Birgand G, Castro-Sánchez E, Hansen S, et al. Comparison of governance approaches for the control of antimicrobial resistance: Analysis of three European countries. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2018, 7, 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Società Italiana di Leadership e Management in Medicina and Istituto Italiano per la Privacy e la Valorizzazione dei Dati - Consensus Statement. Proposta di revisione della normativa privacy in sanità. 2024. Available online: https://www.medici-manager.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Privacy-in-10-punti-la-proposta-di-SIMM_last_REV.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Broom J, Broom A, Kirby E, Gibson AF, Post JJ. Individual care versus broader public health: A qualitative study of hospital doctors' antibiotic decisions. Infect Dis Health 2017, 22, 97–104. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).