1. Introduction

Evolutive housing is a desirable feature in architectural design, particularly within the social housing context. Changes in user needs over time justify the adoption of the evolutive typology, as it also optimizes public investment. Evolutive housing is designed to enable and anticipate functional and usage adaptations as residents’ needs change [

1]. By addressing both current and future demands, these projects align with the global sustainable development agenda.

Housing evolution is commonly associated with horizontal typologies, designed to be built in stages. This study, however, focuses on evolution in vertical typologies, wich cannot expand their built area but can undergo internal rearrangements to better accommodate changes in residents' needs. Thus, evolutive housing serves as a strategy to "enhance the quality of space and its adaptability to different family types" [

2] (p.39). Residential quality refers to the "adequacy of housing and its surroundings to the immediate and foreseeable needs of residents" [

3] (p.9), while also including a subjective aspect that goes beyond basic functions, as the environment provides physical, personal, and social well-being [

4].

The use of the evolutive typology in social housing in Portugal has been recommended since 1971 by Nuno Portas [

5]. More recently, the Lisbon City Council has adopted evolutive housing as an architectural design premise for social housing aimed at relocating residents of social neighborhood in the Portuguese capital.

This article forms part of ongoing research within the doctoral program jointly supervised by the Universidade de Lisboa and the Universidade Federal do Pará in Brazil. The aim is to deepen studies on the use of evolutive housing as a design alternative for social housing and, in the future, to identify parameters that can be proposed for the Brazilian context.

In recent years, Brazil’s experience in mass-producing social housing has standardized projects into two-bedroom units, which have been criticized for the quality of the spaces produced [

6]. Field studies have observed modifications made by residents themselves [

7,

8], often immediately after unit delivery. These adjustments, without technical supervision, have sometimes compromised residents' physical safety. Consequently, housing conditions often revert to precariousness, further contributing to Brazil's housing deficit. As a result, public resources fail to achieve their primary goal: improving the population’s quality of life.

This study builds on previous analyses of the quality of evolutive housing projects used in the resettlement efforts in the Boavista neighborhood in Lisbon, presented at

the I Congreso Iberoamericano de Vivienda Social Sostenible, held in Mexico City in March 2024 [

9]. The evaluation, based on the quality analysis methodology proposed by João Pedro Branco of the

Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil (LNEC) [

3], validated that the projects maintained minimum quality performance, even after the "evolution" of the layouts. However, the analysis identified critical points, highlighting losses to the spaciousness indicator (usable area). Thus, this study seeks to deepen the qualitative analysis, still using the quality parameters proposed by LNEC as a reference [

10].

The projects adopted in the ongoing resettlement process in the Boavista neighborhood in Lisbon served as case studies. At this stage, based on the housing program defined by LNEC [

10], parameters for usable areas by housing typology were established. Simulations of evolution were conducted, leading to the identification of relationships that can inform project design. These relationships may also support advocacy for the adoption of evolutive housing and typological diversity in social housing developments in Brazil, particularly in the Amazon region.

One of the motivations for this doctoral research is to explore alternatives to the standardization of social housing projects currently implemented in Brazil while retaining the time and cost benefits of medium- and large-scale production. Several authors have criticized ongoing Brazilian housing programs, yet little progress has been made in practical design issues [

11]. Developing housing solutions suitable for the local context and the users' needs is widely advocated [

4,

6,

7,

11,

12]. However, public entities continue to present to the federal government, the main funder, projects disconnected from the sociocultural characteristics of their implementation areas. For instance, in Belém, the capital of the state of Pará, in Brazil’s Amazon region, for example, studies indicate that self-built social housing is heavily influenced by riverine housing [

7,

13]. Nevertheless, projects replicating patterns from southern and southeastern Brazil are still prevalent.

2. Flexibility and Adaptability in Housing

A house must physically adapt to the different stages of its residents' lives, the diversity of family groupings, and changes in use over time [

1,

2,

9,

12]. In the context of social housing, families typically remain in the same residence for extended periods. Due to their low-income status, socioeconomic mobility tends to progress at a slower pace. This reality highlights the necessity for social housing projects to prioritize quality, adopt timeless designs, and go beyond the constraints imposed by cost control.

Flexibility and adaptability are integral to the functional lifespan of a building [

14] and are associated with desirable qualities in housing design. Both concepts aim to accommodate emerging needs and behaviors over time, addressing current and future demands, even those not yet known. These principles closely align with sustainability, which also encompasses economic, social, and cultural dimensions.

Direct interaction between designer and the space user typically occurs in horizontal residential projects. Adaptation and flexibility can replace this interaction when there is no direct contact between these actors, a very common situation in multifamily housing projects [

15]. In vertical housing typologies, which are the focus of this study, two forms of flexibility are possible: initial flexibility and continuous or functional flexibility.

Initial flexibility refers to the ability to make layout adjustments and select unit types during the design phase, up until the space is occupied. Continuous or functional flexibility occurs during the occupancy phase, allowing for spatial and functional rearrangements. While continuous flexibility does not take place during the design phase like initial flexibility, it relies on decisions made during the proposal's conception [

4,

15].

Within the concept of continuous and functional flexibility, general guidelines for expansion are proposed, particularly in the realm of social housing. Among the listed characteristics, this study highlights the low hierarchy of rooms and the incorporation of reversible and multipurpose spaces that can be integrated with others, as examples [

4,

15].

Flexibility can also be classified as active or passive. Active flexibility involves structural modifications to space, while passive flexibility does not; instead, space itself adapts to new uses and requirements. Some authors consider passive flexibility to represent true adaptability, arguing that spaces with minimal hierarchy, whether achieved through similar dimensions or strategic connections to circulation areas, are inherently more adaptable [

16].

3. Evolutive Housing Projects in the Boavista Neighborhood

The evolutive housing projects used as a case study are being implemented in the ongoing resettlement process in the Boavista neighborhood in Lisbon. The neighborhood was originally designed for public social housing. In 1938, small, prefabricated houses made of wood and fiber cement were built under the

Casas Desmontáveis program. In 1961, two-story masonry houses were constructed. In 1975, families residing in the original prefabricated houses were relocated to three-story buildings. Between 1980 and 1996, additional buildings with five to seven floors were constructed, completing the rehousing process and the total demolition of the initial prefabricated houses in the neighborhood [

17].

The lot where the masonry houses were built allowed small expansions. However, over the years, the Lisbon City Council (

Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, CML) neither guided nor regulated these expansions. Combined with a lack of maintenance, these houses eventually fell into precarious conditions. In response, the CML has been planning and implementing the staged resettlement of families living in the area known as the

Zona de Alvenaria (masonry zone) to new housing units within the same neighborhood since 2012. The ongoing projects were developed by the municipal technical teams – The Building (

Figure 1) and the architectural firm Orange Arquitetura – The Monoblocks (

Figure 2), the winner of a design competition for this purpose.

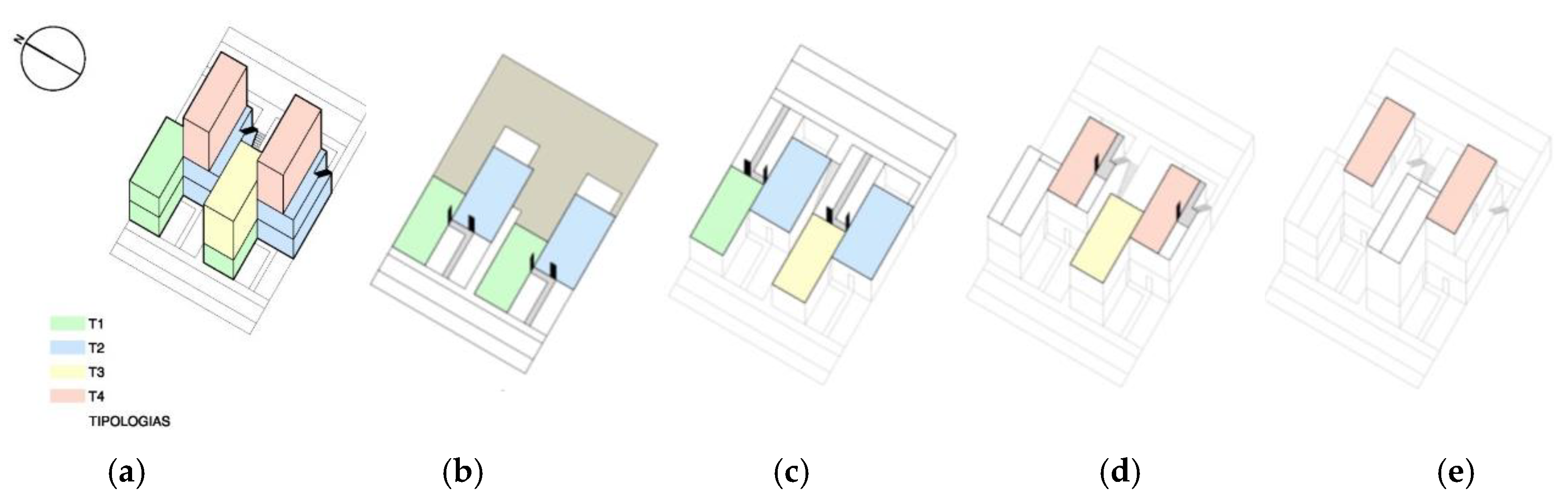

3.1. The Design of the Housing Monoblocks

The winning proposal adhered to the main premises of the competition’s guidelines: typological diversity and the potential for housing evolution [

18]. In addition to these features, the two strongest attributes of this project are the preservation of the private character of the individual units, with direct access from the street, and private backyards. Both solutions refer to characteristics of horizontal housing, although the project adopts a vertical typology of up to four floors.

Figure 2 illustrates the architectural design proposed for the competition. Initially, the plan included ten housing units for every two blocks, forming a monoblock, comprising three T1 units, four T2 units, two T3 units, and one T4 unit. Here, T1 refers to a one-bedroom unit, T2 to a two-bedroom unit, T3 to a three-bedroom unit, and T4 to a four-bedroom unit. Only seven of the ten units had the potential for evolution, with some requiring demolitions and internal rearrangements of hydro sanitary installations. One unit even included the possibility of expanding the built area by adding an upper floor [

19].

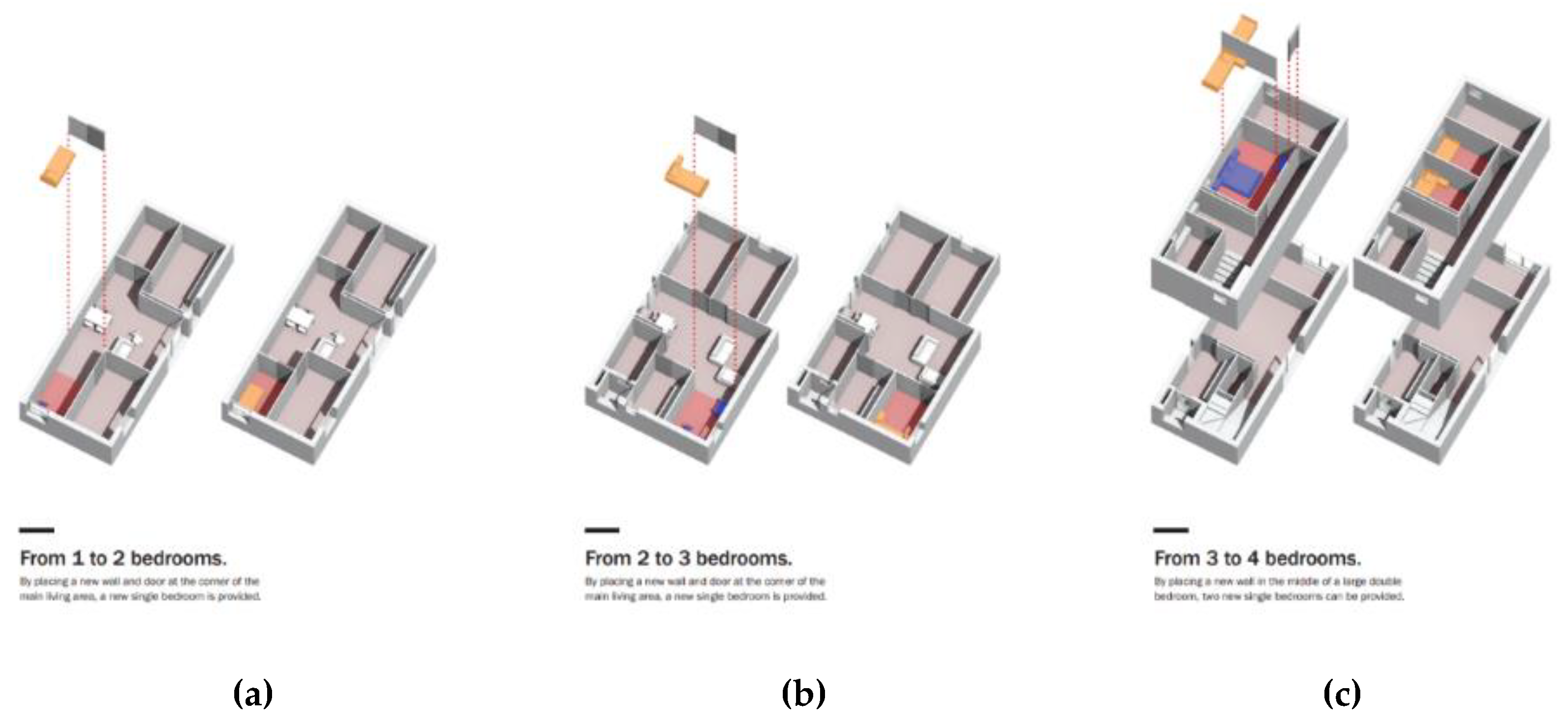

In the final project, the evolution was simplified. The possibility for evolution was expanded to eight typologies by considering the subdivision of the living room to create an additional bedroom or the subdivision of an existing bedroom. In two T2 units, there is provision for a study/work area integrated into the living room, making the space adaptable for multiple uses, including a bedroom. In this way, the total built area remains unchanged (

Figure 3).

The analysis of the functional spatial quality of the monoblock projects revealed critical issues across all typologies after evolution, particularly regarding the spaciousness indicator (usable area). Meanwhile, the adaptability analysis, which assesses whether the housing units allow for changes in spatial relationships to suit residents' lifestyles, ranged from minimal (T1 and T4) to recommended (T2 and T3). The inability to integrate the kitchen with the dining room was one of the unfavorable aspects for typologies evaluated at the minimal level [

9].

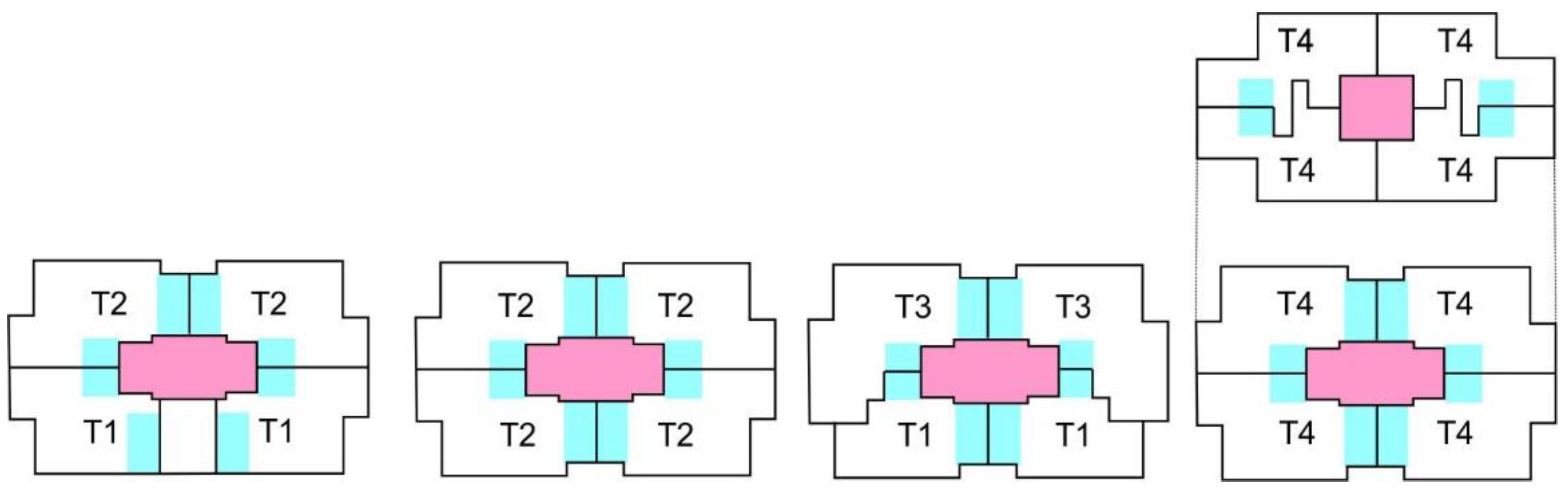

3.2. The Design of Multifamily Buildings

To initiate the construction of the monoblock project, part of the families needed to be relocated. The solution devised by the Lisbon City Council was to phase the construction works. To expedite the resettlement process, the decision was made to construct a five-story building with 46 housing units, which allowed the demolition of the first phase of masonry houses.

The design of these buildings, developed by the Lisbon City Council architects, adhered to the premises of the competition for evolutive housing and typological variety. In addition to all typologies being evolutive (

Figure 4), this project features a modular floor plan, enabling a diversity of typology arrangements per floor (

Figure 5).

A central staircase core in each block, together with the modularity and vertical continuity of constructive elements (bathrooms, kitchens, and technical areas), provided versatility to the floor plan. Next to the staircase, an elevator installation is planned. The possibility of different typological arrangements per floor (

Figure 5) allows the project to be implemented in other areas, adapting to various demands.

Similar to the monoblock project, the analysis of the functional spatial quality of the housing units in the buildings, particularly regarding the spaciousness indicator (usable area), demonstrated a loss of capacity in all typologies after evolution, except for the T3 typology. The evaluation also revealed that, in the case of the buildings, one of the critical points is the kitchen, which has the same dimensions for all typologies, from T1 to T4+1 [

9].

4. Project Evaluation Methodology

Qualitative evaluation employed the parameters of spatial-functional adequacy present in the studies of architectural housing quality developed by LNEC [

10]. It is important to emphasize that this study considers the Portuguese context and Controlled Cost Housing.

According to the document, the quality program aids the design phase by defining requirements that contribute to the satisfaction of a greater number of users. This aligns with the subject of this research, where vertical housing projects cater to a diverse user profile. Furthermore, the program allows for the analysis and objective evaluation of already conceived housing projects, which constitutes one of the objectives of this work.

The quality parameters proposed by João Pedro Branco [

3,

10] are based on an ideal and abstract scenario and do not reflect universal quality standards. Instead, they serve as a more current starting point. It is noteworthy that the minimum area requirements for housing in Portugal are still governed by the

Regulamento Geral das Edificações Urbanas (RGEU), of 1975 [

20].

The analysis methodology developed by LNEC researcher [

3,

10] presents different quality levels, where the minimum level meets the basic daily needs of residents. The recommended level accommodates possible changes in usage modes and the evolution of user needs. The optimal level offers the best response to anticipated changes in housing conditions over time. Based on the areas allocated to each function within the dwelling and considering the minimum quality levels, the information was synthesized in

Table 1.

Table 1 lists the minimum areas for each space within the different housing typologies. The functions defined by the housing program were grouped into the main spaces of a dwelling. For the living room, the areas of the living and formal dining functions were combined. For the kitchen, the areas of meal preparation, daily dining (combined), and laundry (combined) were included [

3,

10]. Ultimately, the total usable areas for each typology were calculated, as well as the total usable areas after adding a twin or single bedroom.

Based on the minimum quality level, three percentage benchmarks for typology evolution were defined, as shown in

Table 2. The first reference considers the full evolution of the typology, increasing the usable area across all spaces where necessary. The second reference pertains to partial evolution, considering the addition of a twin bedroom and the consequent reduction of the living room area. The third reference pertains to partial evolution, considering the addition of a single bedroom.

Table 2 presents the comparative synthesis of the three references of total and partial evolution, based on the minimum level of quality proposed by the LNEC program. The second and third references (partial evolution) are closer to those being practiced by the projects under study.

5. Results

To determine the percentage of evolution adopted in the Boavista neighborhood resettlement projects, the relationship between the area of the additional bedroom and the total usable area of the typology was considered. The formula used to calculate the evolution percentage is expressed in Eq. (1):

Table 3 summarizes the areas and the percentages found for each typology in both Buildings and Monoblocks. It is worth noting that the T4 typology of Monoblocks does not allow evolution.

Finally,

Table 4 presents a comparative synthesis of evolution percentages, high-lighting the partial evolution situation (addition of one bedroom) and the evolutions being implemented in each project.

The evolutionary housing projects used in the Boavista neighborhood resettlement process in Lisbon exhibited significant discrepancies in evolution percentages when compared to each other. This divergence arises from the varying areas adopted by the designers to allow project flexibility. The areas proposed by the Monoblock designers were closer to the addition of a single bedroom, while the areas designed for the Buildings better accommodated the addition of a double bedroom (see

Table 3). Thus, when compared to the equivalent partial evolution (considering the addition of either a double or a single bedroom), the percentages generally exceeded the reference values. The exception was the T1 typology of the Monoblocks, which fell below the reference value.

Previous analysis [

9] demonstrated that even within projects, uniform quality levels were not achieved. Not all spaces within the same typology were of the same quality level, nor did all typologies within the same project (Building or Monoblock) exhibit uniform performance. Evaluations ranged from minimum to recommended quality levels. For instance, while Monoblocks partially met the established criteria, they failed to consistently achieve minimum quality standards across all areas. Living rooms maintained optimal quality levels even after evolution, whereas certain bedrooms—especially when considered for double occupancy—were classified at the minimum or even null quality level.

A notable aspect of the analysis is that the size of the typology is inversely proportional to the percentage of additional area evolution. The area of the additional bedroom is diluted in the total useful area of the typology. This relationship is significant when correlated with the cost per square meter in social housing.

For evolutionary housing projects adopting the same strategy as the Boavista neighborhood—subdividing the living room to add a bedroom—it is necessary to consider oversizing. It is important to highlight that the critical points in the general quality analysis of the projects were the use of a single kitchen module for all typologies and not the dimensions of the living rooms or bedrooms [

9]. However, the maintenance of the kitchen size for all typologies follows the minimum size proposed by RGEU [

20].

Referring to the concept of quality levels presented by the LNEC analysis methodology, the ideal would be to adopt the recommended level, which accommodates potential changes in usage modes and evolving user needs, or the optimal level, which best anticipates housing changes over time. However, these references would be too distant from the Brazilian context, where only the minimum usable area standard for social housing exists.

6. The Brazil´ Social Housing Parameters

In Brazil, there is no mandatory minimum area requirement for residential spaces such as bedrooms or living rooms. Studies suggest a general reference of 11 to 14 m² per inhabitant [

12]. The current guidelines of the Brazilian government for the social housing program,

Minha Casa, Minha Vida (MCMV), specify only a minimum total usable area of 40 m² and a minimum typology of T2 (double bedroom + twin bedroom) [

21].

Table 5 shows that the arrangement of mandatory furniture and equipment determines the room size [

21]. Therefore, social housing projects in Brazil are currently guided by the minimum required furniture and its corresponding area, as the MCMV program has become a national reference.

Thus, the government assumes that housing units should be designed for four people in a uniform and standardized way throughout the country. While the program outlines the minimum requirements, the federal government does not provide additional funding for projects that exceed the T2 typology or 40 m². Consequently, the flexibility advocated here, including the possibility of layout evolution and typological diversity, is not implemented by states and municipalities in executing housing programs. Flexibility under the MCMV program is limited to provisions for expansion in horizontal housing, such as single-story houses [

21].

The MCMV technical specifications also recommend that hooks for hammocks be provided in bedrooms in the North and Northeast regions of Brazil. Hammocks are not considered furniture, although sleeping in hammocks is a cultural reality in these regions and contributes to bedroom usage.

The use of hammocks as furniture could be a specific feature of the Amazonian social housing program. Investigating how spatial relationships in stilt houses are translated into urban housing still requires further studies. In such contexts, the kitchen may play a more central role in family and social integration than the living room [

13].

In comparison with the Quality Program of LNEC standards, considering the T2 typology for four-person occupancy, the minimum usable area would be 46.5 m² (see

Table 1). The Brazilian program shows a deficit of approximately 14% in area. Including an additional room equivalent to a single bedroom would increase the usable area by 10.6% (see

Table 2). Thus, based on the usable area standards adopted in Portugal, the required area for a T2 housing unit with flexibility and minimum spatial quality would be 51.43 m², representing an approximate 22.22% increase in area compared to the MCMV model in Brazil.

6.1. Implications and Future Needs

The analysis can serve as a parameter for incorporating flexibility and adaptability into housing projects. Instead of following a uniform and standardized approach, it is essential for projects to allow customization and evolution based on the changing needs and preferences of residents, offering them choices, options for use, and opportunities to appropriate space. Adapting bedrooms and providing the possibility of transforming additional areas into multifunctional spaces are critical aspects to address a broader range of individual needs and preferences.

Adapting housing designs to cultural needs and local realities is essential for improving housing quality and enhancing user satisfaction. It is well known that multiple solutions exits for the same basic need (housing), but these solutions vary according to cultural, social, and economic contexts, even within the same locality. Family habits are constantly changing [

22].

Similarly, the design of bedrooms warrants reconsideration. While current programs allocate larger areas to the master bedroom, bedrooms could be designed with similar areas, thus breaking hierarchical norms, or as larger spaces accommodating up to three people, with provisions for future subdivision based on shifting family needs and privacy requirements. The bedroom is the most private area of a home [

23]. This point is particularly significant when considering that housing is more than just a dwelling [

24]; it transcends physical space, encompassing security, intimacy, privacy, isolation, and personal space [

25].

Interaction with the built environment is crucial for addressing individual needs and fostering personal development. The additional space, conventionally considered as another bedroom, could serve various purposes. For families affected by resettlements in Brazil, this space could support commercial or professional activities, provide more room for hosting guests, or allow for an expanded kitchen—a central feature of Brazilian homes. Ultimately, families should have the autonomy to determine how best to utilize this space.

7. Final Considerations

Spatial quality is an essential aspect of social housing, directly influencing the comfort and quality of the residents´ life. The analysis of the Boavista neighborhood projects in Lisbon highlights the importance of considering flexibility and adaptability in housing designs. These approaches enable housing to evolve according to residents’ needs, providing greater functionality and long-term satisfaction.

The projects currently under development adopt three distinct forms of spatial flexibility: typological diversity, intrinsic flexibility, and adaptability [

22]. These approaches have significantly contributed to a participatory resettlement process, offering more suitable options to meet individual needs.

The comparison with the Brazilian context reveals that there is still a long way to go for social housing projects in Brazil to move beyond the minimum quality standards. The adopting of spatial quality criteria, combined with provisions for flexibility and adaptability, is essential to improving housing quality and ensuring it meet residents´ needs over time.

The analysis conducted used the minimum reference framework, aiming to understand the bare minimum necessary to allow for project flexibility. However, within the quality concept proposed by the LNEC program, it would be more appropriate to adopt at least the recommended level as a reference. It is crucial to conduct studies more closely aligned with the Brazilian reality, not as a universal model but as a starting point for designing evolutionary projects.

The minimum requirements established by MCMV program represented significant progress compared to the previous lack of parameters. The analyses presented here aim to contribute to rethinking the next steps for technical specifications in Brazilian social housing. This includes considering flexibility and typological diversity, as well as housing activities not currently addressed, such as study spaces, for example.

Future steps should consider the financial impacts of these proposals. Other studies indicate an increase of up to 50% in area and, consequently, in costs for designing flexible social housing projects [

12]. This highlights the need to redefine the guidelines of Brazilian housing programs to accommodate this alternative.

The percentage increases required to allow this flexibility may strengthen the argument for public entities to adopt evolutionary typologies and typological diversity in social housing developments in Brazil. A 22% increase in area and costs represents a justifiable investment considering the social gains and benefits in terms of quality and sustainability in these projects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, and supervision, A.K.P and F.R.; methodology, L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, LS.; writing—review and editing, A.K.P, F.R. and L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is financed by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the Strategic Project with the references UIDB/04008/2020 and UIDP/04008/2020.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Departamento de Habitação da Câmara Municipal de Lisboa and Architect Alexandre Dias of ORANGE Arquitectura e Gestão de Projeto for providing access to the projects adopted in the Boavista neighborhood resettlement process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LNEC |

Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil (National Civil Engineering Laboratory) |

| CML |

Câmara Municipal de Lisboa (Lisbon City Council) |

| RGEU |

Regulamento Geral das Edificações Urbanas (General Regulation of Urban Buildings) |

| MCMV |

Minha Casa, Minha Vida (My House, My Life) |

References

- Peña, A.R.; Brandão, D.Q. Habitação de interesse social evolutiva: Análise de projetos flexíveis quanto à construtibilidade no momento de ampliação. In XV Encontro Nacional de Tecnologia do Ambiente Construído, Maceió, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Félix, R.D. Habitação evolutiva: projeto para o Programa de Autoconstrução em Santa Maria da Feira. Dissertação de doutorado, Faculdade de Arquitectura, Universidade de Porto, 2020. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10216/134008 (accessed on 15 Jan 2025).

- Pedro, J.B. Definição e avaliação da qualidade arquitectónica. Dissertação de doutorado, Faculdade de Arquitectura, Universidade do Porto, 2000. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260087253_Definicao_e_avaliacao_da_qualidade_arquitectonica_habitacional (accessed on 15 Jan 2025).

- Peteno, E.A.; Capelin., L.J.; Trentini, L.D. A importância das disposições técnicas e diretrizes para projetos de habitações de interesse social (HIS) saudáveis. Akrópolis 2020, 28, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portas, N. e Dias, F. Tipologias de Edifícios – Habitação Evolutiva – Princípios e critérios de projectos. LNEC: Lisboa, Portugal, 1971.

- Ferreira, J.S.W. (coord.) Produzir casas ou construir cidades? Desafios para um novo Brasil urbano. parâmetros de qualidade para a implementação de projetos habitacionais e urbanos. LABHAB.; FUPAM: São Paulo, Brasil, 2012; Available online: http://www.labhab.fau.usp.br/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/ferreira_2012_produzirhab_cidades.pdf (accessed on 15 Jan 2025).

- Trindade, R.P.; Vicente, L.R.; Perdigão, A.K.A.V. Interpretações do uso espacial para discussão projetual em programas habitacionais na Amazônia: Vila da Barca e Taboquinha, Belém (PA). In Revista Nacional de Gerenciamento de Cidades 2017, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graim, R.M.T.; Felisbino, D. de A. ; Perdigão, A.K.A.V. Impacto causado pelo processo de remanejamento/reassentamento no idoso: o projeto Vila da Barca, Belém (PA). In Revista Nacional de Gerenciamento de Cidades 2017, 5, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.G.T.; Roseta, F.; A tipologia evolutiva e a diversidade tipológica para a habitação social pública. Uma importante ferramenta participativa dentro do processo de realojamento do bairro da Boavista em Lisboa. In I Congresso Iberoamericano de Vivienda Social Sostenible, Cidade do México, México, Março de 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381997267_A_tipologia_evolutiva_e_a_diversidade_tipologica_para_a_habitacao_social_publica_Uma_ferramenta_participativa_dentro_do_processo_de_realojamento_do_bairro_da_Boavista_em_Lisboa (accessed on 15 Jan 2025).

- Pedro, J.B. Programa Habitacional: Habitação. LNEC: Lisboa, 1999. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257652659_Programa_habitacional_Habitacao (accessed on 15 Jan 2025).

- Kowaltowski, D.C.C.K.; Muianga, E.A.D.; Granja, A.D.; Moreira, D. de C. ; Bernardini, S.P.; Castro, M.R. A critical analysis of research of a mass-housing programme. In Building Research & Information 2019, 47, 716–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logsdon, L.; Costa, H.; Fabrício, M. Flexibilidade na arquitetura: mapeamento sistemático de literatura em bases brasileiras. In XVII Encontro Nacional de Tecnologia do Ambiente Construído, 2018, p. 2257–2272.

- Nascimento, I.C.M. de O. ; Perdigão, A.K. de A. V. Interpretação socioespacial em comunidades tradicionais na Amazônia pela teoria de Christopher Alexander. In Oculum Ensaios 2023, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar, P.; e Brito, J. O ciclo de vida das construções II - vida útil funcional. In Arquitectura & Vida 2003, p. 74-78. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281744941_O_Ciclo_de_Vida_das_Construcoes_II_-_Vida_Util_Funcional (accessed on 15 Jan 2025).

- Brandão, D.Q. Disposições técnicas e diretrizes para projeto de habitações sociais evolutivas. Ambiente Construído 2011, 11, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, H. Para um habitar mais versátil, diversificado e inclusivo. In 9o PROJETAR, Curitiba, Brasil, 22 a 25 de outubro 2019, 1-10.

- Soares, M.S.; Cidade partilhada, cidade participada - Proposta participada de qualificação. O bairro da Boavista em Lisboa. Dissertação de mestrado, Faculdade de Arquitetura, Universidade de Lisboa, 2017. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.5/15399 (accessed on 15 Jan 2025).

- Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. Caderno de encargos. Concurso público de conceção da solução arquitetônica para a “Zona de Alvenaria” do bairro da Boavista em Lisboa. Lisboa, 2013.

- Dias, A., Silvestre, B. e Spranger, L. Memória descritiva e justificativa, Concurso público de conceção da solução arquitetónica para a “Zona de alvenaria” do bairro da Boavista em Lisboa, 2013.

- Portugal. Ministério do Equipamento Social. Secretaria de Estado de Habitação e Urbanismo. Decreto-Lei 650/75 de 18 de novembro de 1975. Regulamento Geral das Edificações Urbanas (RGEU). Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-lei/650-1975-310259 (accessed on 15 Jan 2025).

- Brasil. Ministério das Cidades. Portaria 725, de 15 de junho de 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.br/cidades/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/acoes-e-programas/habitacao/arquivos-1/copy_of_20241213_Portaria_MCID_725_Especificacoes_MCMV_FAReFDS_COMPILADA.pdf (accessed on 15 Jan 2025).

- Brandão, D.Q.; Heineck, L.F.M. Significado multidimensional e dinâmico do morar: compreendendo as modificações na fase de uso e propondo flexibilidade nas habitações sociais. In Ambiente Construído out./dez. 2003, 3, 35–48. Available online: https://seer.ufrgs.br/index.php/ambienteconstruido/article/view/3504. (accessed on 15 Jan 2025).

- Hertzberger, Herman. Lições de Arquitetura. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2006.

- Turner, J. Housing as a Verb. In Freedom to Build, dweller control of the housing process. John F C Turner & Robert Fichter. Collier Macmillan: New York, 1972; pp. 148-175.

- Cabrita, A.R. O homem e a casa: definição individual e social da qualidade da habitação. LNEC: Lisboa, 1995.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).