1. Introduction

The genus

Curtobacterium, meaning short rods[

1], includes Gram-positive, obligate aerobic bacteria that belongs to the family Microbacteriaceae in the phylum Actinomycetota and is represented by over a dozen species[

2].

Curtobacterium species are present in diverse environments including soil and plants. In plants,

Curtobacterium has been frequently described in the rhizosphere as well as endophytes in various parts of plants including roots, leaves, stem, fruit, and seeds[

2,

3].

Curtobacterium was described as the predominant genus of the leaf litter community, likely decomposing plant debris[

3].

The most commonly associated

Curtobacterium species with plants is

Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens, which includes pathogenic and non-pathogenic variants[

4]. Several pathovars of

C. flaccumfaciens, are known to infect many species of plants including legumes, beet, and flowering ornamentals, with significant economic losses; as a result, these pathovars are even subject to strict quarantine in many countries[

4]. Recently,

C. allii (renamed as

C. flaccumfaciens pv.

allii) was identified as a bulb rot pathogen in onion[

5]. Pathogenic

Curtobacterium spp. primarily colonize vascular tissues, resulting in wilt disease[

4], and can also cause root rot[

5]. Aside from

C. flaccumfaciens though, most

Curtobacterium species are not known to be pathogenic in plants; it is suggested that many species may perform more ecological roles and promote plant growth[

6]. Other species of

Curtobacterium include

C. luteum,

C. citreum,

C. pusillum,

C. herbarum and

C. oceanosedimentum. Species

C. plantarum,

C. luteum and

C. herbarum were reported as leaf endophytes in soybean[

7], Citrus[

8] and grass[

9], respectively.

C. luteum, isolated from the sediment of sea grass meadow[

10] and

C. oceanosedimentum recovered from paddy soil[

11] were both reported as plant growth promoters.

C. citreum was isolated as a strawberry fruit endophyte[

12],

C. albidum (now considered

C. citreum) was studied as a plant growth promoter in rice[

13] and

C. pusillum was found as a human clinical specimen[

14].

Endophytic

Curtobacterium could be beneficial to plants, for example, through mitigating disease symptoms[

15]. However, the knowledge of endophytic

Curtobacterium is restricted to rhizosphere and phyllosphere niches and less is known about the colonization in other parts of the plant. Additionally,

Curtobacterium species have been predicted, based on genomic analysis, to be capable of digesting carbohydrates through glycosyl hydrolases[

2], but functional evidence for such nutritional activities is limited. Furthermore, it is unclear if species other than

C. flaccumfaciens are prominent endophytes in plants.

In this study, we comparatively characterized six endophytic Curtobacterium species isolated from fruits, stems, and a previously unreported niche of Curtobacterium, flower petals. We found that all isolates shared starch-degrading and phosphate solubilizing capabilities as well as the ability to digest the plant sugars glucose, sucrose, and fructose. Finally, we discovered that multiple isolates related to C. oceanosedimentum are plant endophytes. Surprisingly, we also found that nearly all tested Curtobacterium endophytes are psychrotolerant with some adaptive variants.

2. Methods

2.1. Bacterial Growth Media

Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) was used for general growth and propagation of bacteria, as well as to test growth at various temperatures. Milk agar plates were prepared by adding 3% skim milk to TSA. Starch agar, nutrient gelatin, Simmons citrate agar and urea broth were prepared according to manufacturer’s instructions (Carolina Biological), as was Pikovskayas agar (Himedia Inc). To test salt tolerance, TSA plates were prepared with 5%, 7.5% and 10% sodium chloride.

2.2. Isolation of Bacterial Endophytes

Endophytic bacteria were isolated from six samples: four fruits, one flower and one stem tissue (

Table 1). The four fruits were two batches of store-bought rambutan in Springfield, Virginia and Cleveland, Ohio, respectively, with the fruits most likely having a South East Asian origin, steak tomato from a local store in Erie, Pennsylvania (PA), and a roughleaf dogwood wild berry fruit found on campus at Mercyhurst University (MU) in Erie, PA. Flower petals of a purple hydrangea at MU and the stem of Indian pipe,

Monotropa uniflora from Allegheny National Forest were the sources for the two remaining isolates. Endophytic bacteria were isolated by serial dilution plating. About 0.5-1 gram of tissue was surface sterilized by submerging in 95% ethanol for 15-20 seconds and immediately rinsed thoroughly three times in sterile nanopure water. Using a sterile razor blade, the exterior layers were shaved off and the rest of the tissue was homogenized in 9mL of sterile water in a sterile mortar and pestle. Bacteria were mostly isolated in the first three dilutions (10

-1 to 10

-3) on Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) plates. Pure cultures of the bacteria were obtained by streak for isolation. Bacteria identified as

Curtobacterium species were further characterized. Bacteria were grown at 25 °C unless otherwise indicated.

2.3. Visualization of Bacteria

Colony morphology analysis was performed by streaking for isolation and incubating at 25 °C for one week. Gram staining was performed with 30-second sequential treatment of heat fixed smears with crystal violet, Gram’s iodine, 95% ethanol, and safranin.

2.4. Molecular Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis of Bacterial Isolates

To identify the bacteria, PCR was performed to amplify the 16S rRNA gene from the isolates. 5µL of overnight tryptic soy broth (TSB) cultures were combined with 45µL of master mix containing the 1.25µM primers- 27F (5’-AGAGTTTGATYMTGGCTCAG-3’) and 1512R (5′-ACGGCTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) and DreamTaq PCR Master Mix (2X) (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). PCR was performed with an annealing temperature of 57 °C. PCR amplification was confirmed through agarose gel (1.5%) electrophoresis and the PCR products were purified using the Invitrogen PureLink PCR Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific) and the purified PCR samples were submitted to Azenta Inc. (New Jersey) for Sanger sequencing. The forward and reverse sequences were combined to obtain a 1.4kb contig. All six 16S rRNA contig sequences have been submitted to Genbank and the accession numbers are IPS11, PV019085; KB1, PV019086; PBH-A, PV019087; RMB2, PV019088; ST1.1, PV019089; WBB, PV019090. The 16S rRNA sequences were used for nucleotide BLAST search on NCBI. The contigs were assembled with reference

Curtobacterium sequences obtained from Genbank in MEGA11 and multiple sequence alignment was performed using CLUSTALW on MEGA. A neighbor joining tree was constructed on MEGA11[

16] with 500 bootstrap replications.

2.5. Detection of Bacterial Pigments

3 mL of overnight TSB culture of each isolate (three replicates) was centrifuged at 13,000rpm to obtain a pellet which was yellow or orange. The pellet was resuspended in 1mL of 100% methanol, vortexed for 15-20 seconds to resuspend the pellet, incubated at 80 °C for 10 minutes to extract the pigment, then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 1 minute to pellet the cells. At this point, the pellet was discolored, and the supernatant acquired a yellow color with the extracted pigment. Aliquots of 200µL of each replicate was loaded into a 96 well plate and an absorption spectrum was generated and specific absorbance at 450nm was measured using the Biotek Synergy H1M Microplate reader (Agilent Technologies).

2.6. Metabolic Tests of Bacterial Isolates

The catalase test was performed by observing bubbling in 3% hydrogen peroxide. An oxidase test was done by adding one drop of oxidase reagent on a swab with bacteria and observing for blue coloration as positive result. Gelatinase was tested by looking for liquefaction of nutrient gelatin stabs. Citrate tests were positive if blue coloration was observed on Simmons Citrate slants. To test amylase activity, bacteria were grown for 2 days on starch agar and iodine was added to stain the starch in the plate. The presence of a halo around the bacterial growth indicated starch digestion and amylase activity. Caseinase activity was determined by growing bacteria on 3% milk agar plates. To quantify growth stimulation by milk, 3 replicate 20µL drops (OD600=0.1) were plated on milk agar and allowed to grow for 5 days. All bacteria from each drop were suspended in 10mL and sterile water and absorbance was read at 600nm to quantify growth.

2.7. Stress Tolerance of Bacterial Isolates

Mild, moderate, and high salt tolerance was determined by growth on 5%, 7.5%, and 10% sodium chloride, respectively. For heat tolerance experimentation, all Curtobacterium were inoculated in TSB cultures and allowed to sit at 42 °C for 2 days. Absorbance at 600nm was recorded for cultures at day 0 and day 2 to quantify growth. For cold tolerance testing, overnight TSB cultures of bacteria, normalized to OD600=0.1, were used to plate three replicate 20µL drops on TSA plates and incubated at 25 °C and 6 °C for 5 days. Bacteria from each replicate was homogenized in 10mL of sterile water and absorbance at 600nm was observed to quantify growth.

2.8. Statistical Tests

Experiments were performed with three replicates and each experiment was repeated 2-3 times. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Significance of the results among the treatments was determined using Student t-tests (p < 0.05) and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test (

https://astatsa.com/OneWay_Anova_with_TukeyHSD/).

3. Results

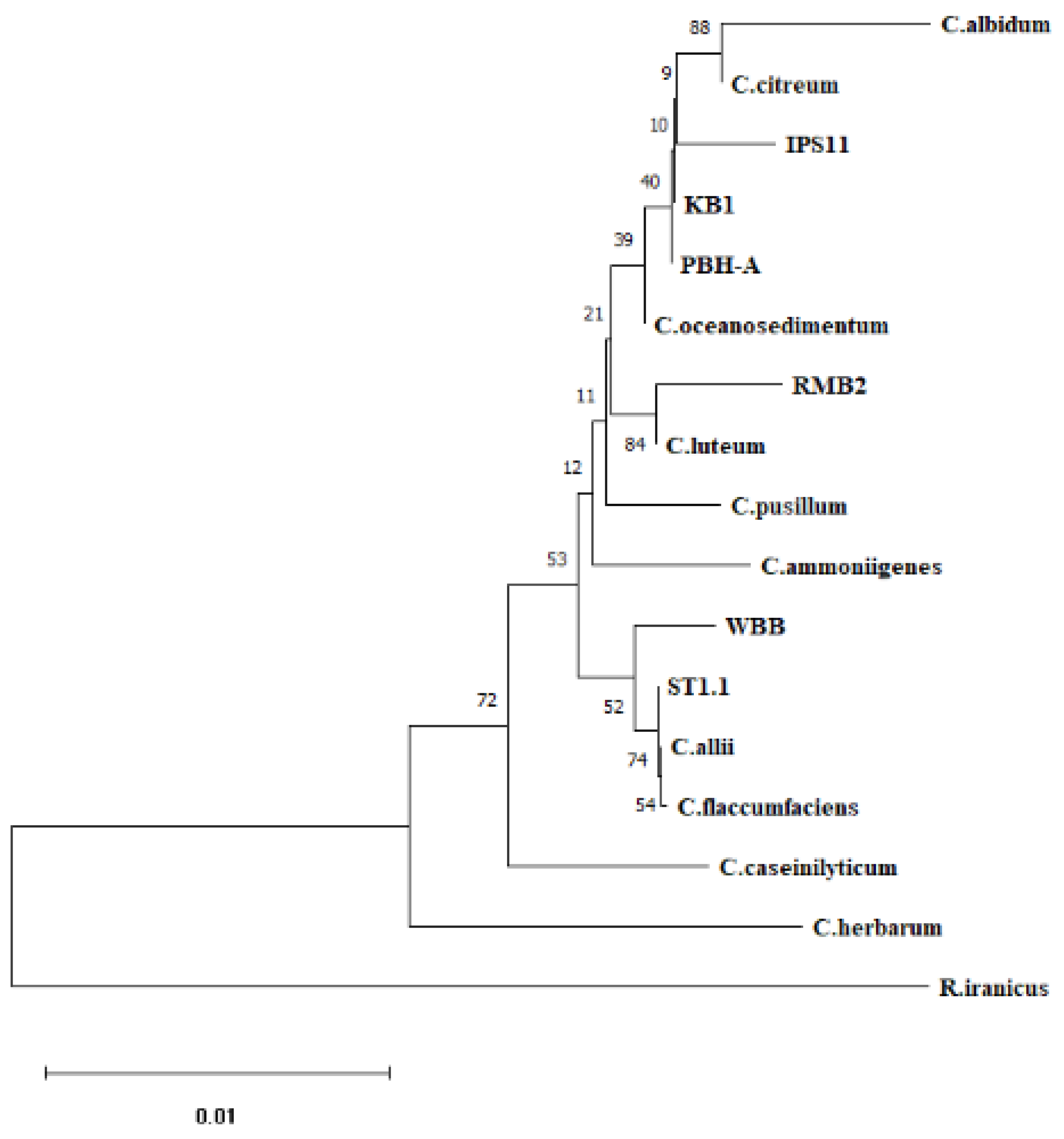

3.1. Curtobacterium Species Isolated from Various Sources

Six

Curtobacterium species isolated using serial dilution plating were selected for comparative analysis from a collection of bacteria isolated from wild or store-bought samples. Four of the isolates were from fruit pulp, one from flower petals, and one from the stem of the parasitic plant,

Monotropa uniflora, commonly referred to as Indian pipe (

Table 1). A 1.4kb amplicon of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified from each of the isolates and sequenced to assemble ~1.4kb contigs. BLAST search of the contigs and phylogenetic analysis of the six endophytic isolates revealed best matches with three species:

C. oceanosedimentum (IPS11, KB1, PBH-A),

C. luteum (RMB2) and

C. flaccumfaciens (ST1.1, WBB) (

Table 1,

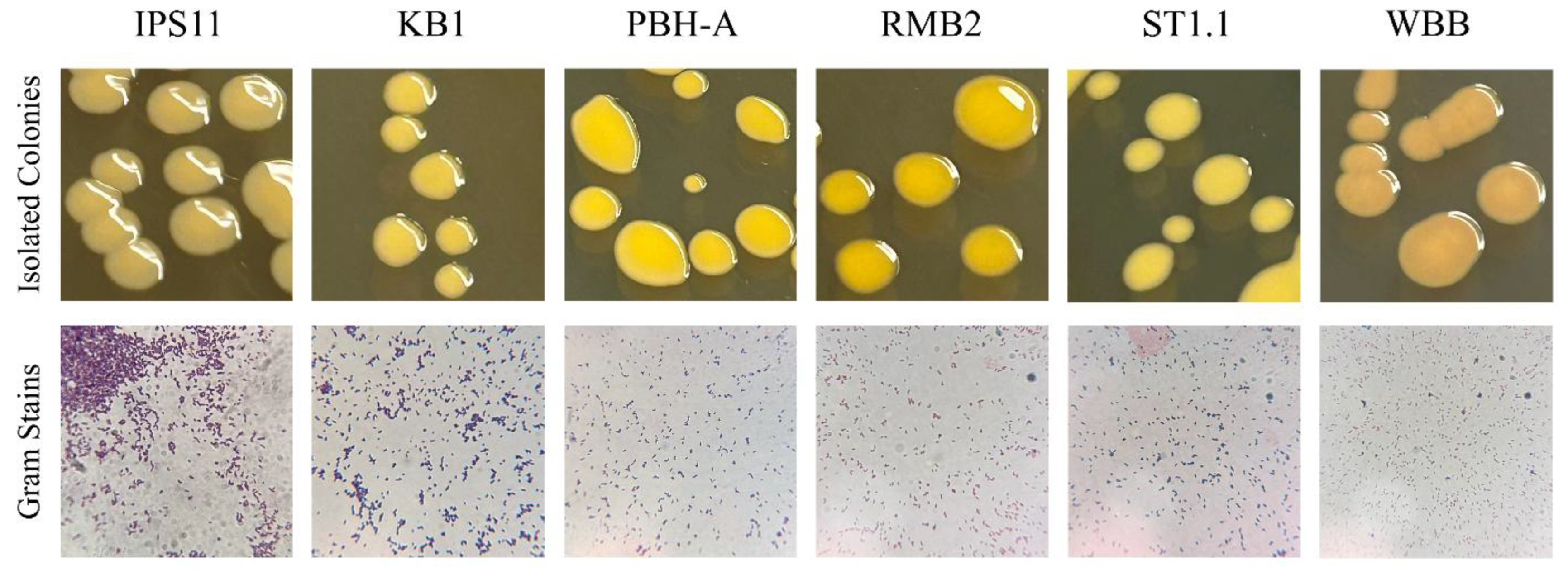

Figure 1). All isolates were visualized as short Gram-positive rods in Gram staining, characteristic of

Curtobacterium species (

Figure 2). Colony morphology was generally similar among the isolates (

Table 2). Colonies were flat or raised, distinctly glossy and mostly circular with a tendency to fuse with neighboring colonies, resulting in ovoid colonies in a paint splatter pattern (

Figure 2).

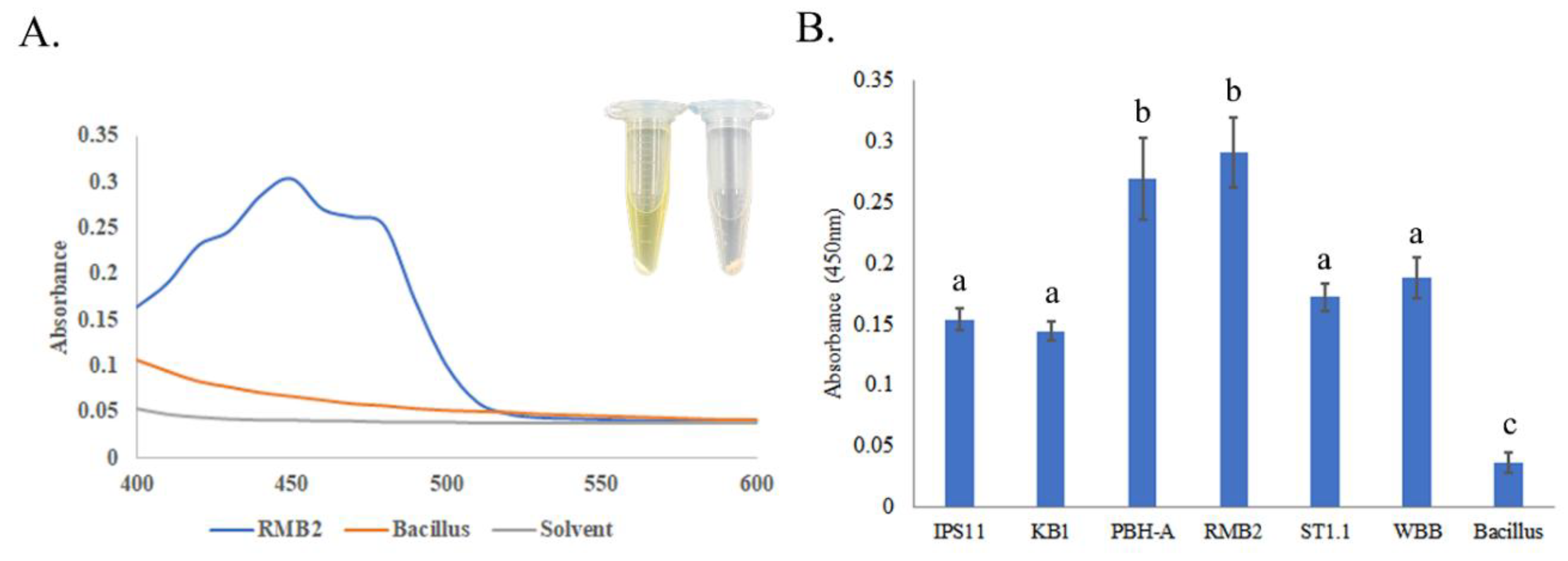

3.2. Pigmentation in Curtobacterium Species

All

Curtobacterium isolates, except IPS11, which generally produced pale yellow colonies and WBB that produced orange colonies, were characterized by vibrant yellow colonies (

Figure 2,

3). A spectral scan of the extract of a representative isolate, RMB2, revealed a peak with an absorption maximum at 450nm, which was absent in the non-pigmented control

Bacillus species (

Figure 3). Relatively high absorption at 450nm was observed in all

Curtobacterium isolates, suggestive of a potential carotenoid peak that could contribute to the yellow/orange coloration of the isolates.

3.3. All Curtobacterium Isolates Could Digest Starch, Casein and Insoluble Phosphate, But Differed in Their Ability to Utilize Citrate

All

Curtobacterium species in this study appear to have certain conserved secreted enzyme activities. All isolates displayed amylase activity in digesting starch on starch agar, caseinase activity in digesting milk protein in milk agar and phosphatase activity in their ability to solubilize inorganic phosphate on Pikovskayas agar (

Figure 4A,B). Furthermore, growth of nearly all

Curtobacterium species is remarkably stimulated by skim milk, suggesting that milk protein, sugars and/or minerals could enhance the growth of these isolates (

Figure 4A). Interestingly, all isolates displayed an exceptionally mucoid and watery phenotype on Pikovskayas agar plates (

Figure 4B). Two of the six isolates corresponding to the

C. oceanosedimentum group, IPS11 and KB1, were able to utilize citrate and grow better on Simmons citrate agar, unlike the other isolates (

Figure 4C). Interestingly, the isolate WBB did not grow on Simmons Citrate agar, suggesting possible inhibition by bromothymol blue or other ingredients of the medium (

Figure 4C). None of the isolates appeared to display gelatinase, urease or laccase enzyme activity (

Table 3).

3.4. All Curtobacterium Isolates Could Ferment Fructose, Sucrose and Glucose, But Some Isolates Developed Specialized Sugar Fermentation Capacity

The ability of the

Curtobacterium isolates to ferment ten different sugars was tested in phenol red broth with sugar supplements. All the isolates were able to ferment fructose, sucrose, glucose, galactose and arabinose, based on their ability to acidify the medium through sugar fermentation and turn it yellow (

Table 4). However, only IPS11 was able to ferment mannitol and only IPS11 and RMB2 were able to break down maltose. None of the

Curtobacterium isolates were able to ferment lactose, sorbitol or trehalose.

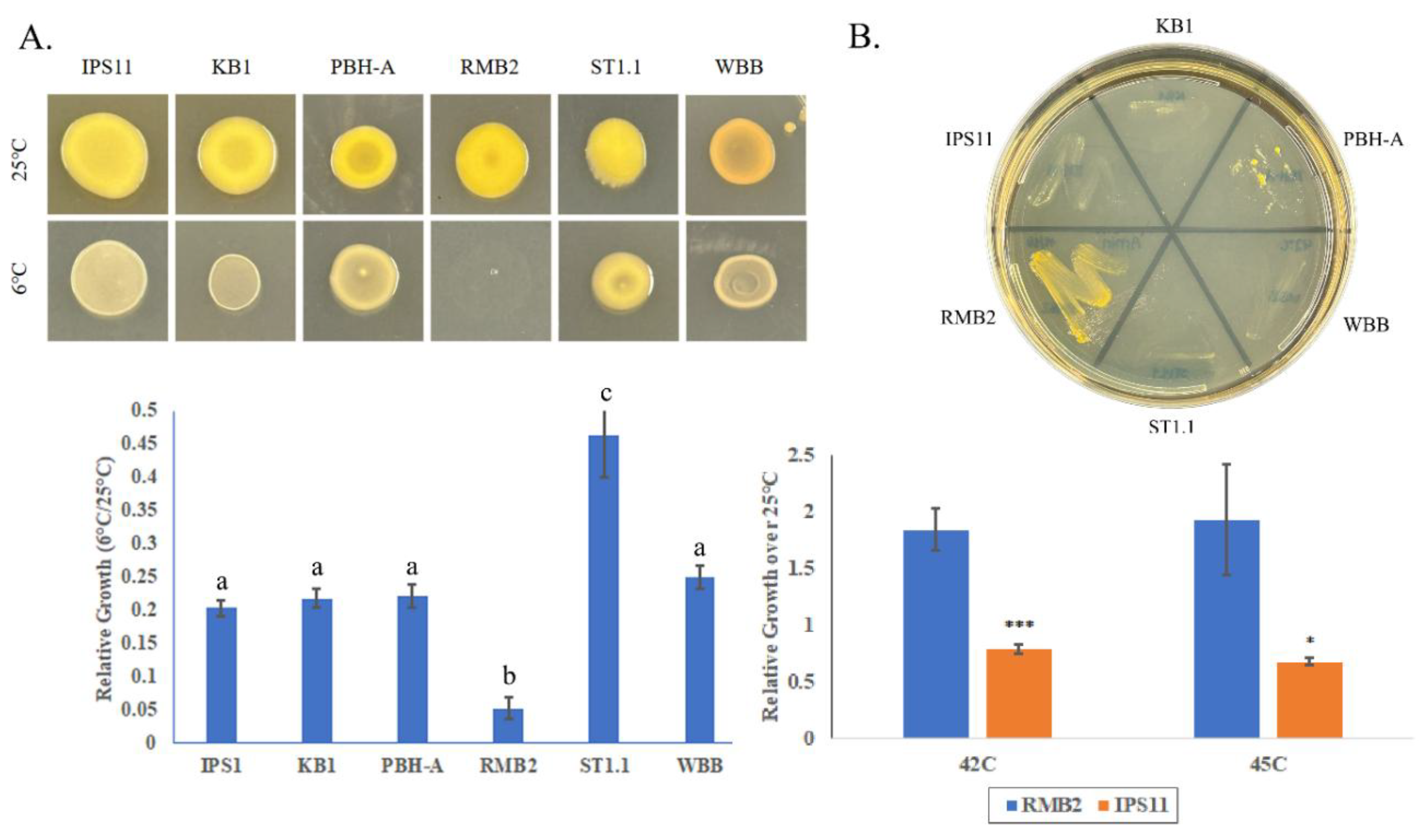

3.5. All Curtobacterium Isolates Are Psychrotolerant, With the Exception of One Isolate That Is Thermotolerant

All

Curtobacterium isolates, except RMB2, demonstrated cold tolerance, being able to grow at 6 °C, with one isolate, ST1.1 displaying superior cold tolerance (

Figure 5A). Interestingly, RMB2 was the only isolate that could grow at high temperatures up to 45 °C (

Figure 5B). Besides temperature tolerance, all

Curtobacterium bacterium species displayed moderate salt tolerance based on their ability to grow on 7.5% sodium chloride (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

In this study, we compared six endophytic isolates of Curtobacterium species isolated from various plant sources, specifically fruit, flower and stem tissue. The isolates appeared to be mostly related to C. flaccumfaciens, C. luteum and C. oceanosedimentum species based on BLAST search and phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA sequences. All tested isolates were yellow or orange pigmented, short or curt Gram-positive rods (hence the name, Curtobacterium) mostly psychrotolerant, capable of starch, casein, and insoluble phosphate hydrolysis, able to digest common plant sugars, and differentially utilized citrate and other sugars. We also found a thermotolerant Curtobacterium isolate suggesting novel adaptations.

4.1. Curtobacterium Species as Plant Endophytes

Four of the six

Curtobacterium isolates in this study were isolated from fruits- KB1, RMB2, ST1.2 and WBB (

Table 1). Consistent with our observation,

Curtobacterium species have been found on the surface or interior of a number of fruits previously, suggesting that

Curtobacterium is a common pomophyte, inhabiting fruits. Specifically,

Curtobacterium has been isolated as an epiphyte from blueberry[

17], wild cranberry fruit[

18], withered grapes[

19], and nectarine[

20], and as an endophyte in fruits of coffee berry[

21], mulberry[

22], and strawberry[

12]. Typically,

C. flaccumfaciens and

C. citreum have been reported in fruits, which makes our observation of

C. luteum (RMB2) and

C. oceanosedimentum (KB1) in fruits novel. One of the

Curtobacterium strains was isolated from purple hydrangea flower petals (PBH-A) and is the first characterization of a

Curtobacterium from flower petals, since the only one other study reported the floral isolation of

Curtobacterium from apple flower stigmas[

23].

Curtobacterium has also been commonly found on or inside the stem of dry bean (

Phaseolus sp.)[

24]

Eucalyptus[

25], sugarcane[

26], tea chrysanthemum[

27], tomato[

28], willow tree[

29] and yerba mate (

Ilex sp.)[

30]. Our isolation of

Curtobacterium from the stem of the parasitic plant,

Monotropa uniflora (IPS11) in this study adds to the knowledge that

Curtobacterium is a stem endophyte in a diversity of plants. Since all strains in this study were isolated from apparently healthy tissue, it is possible that these isolates are commensals that are supported by the host tissue and protect the host from potential pathogens or could themselves be opportunistic pathogens.

4.2. Morphological Features of Curtobacterium Species

Curtobacterium has primarily been described as a yellow pigmented genus; some

C. flaccumfaciens isolates were noted to be orange or pink[

31]. Consistently, nearly all our isolates were yellow, with the exception of the

C. flaccumfaciens WBB, which displayed an orange color (

Figure 2,

3). Interestingly, all isolates, including WBB, showed a similar absorption spectrum with a maximal absorption at 450nm (

Figure 3), suggesting the presence of a potential carotenoid pigment producing the yellow color[

32], akin to

Pantoea stewarti, which is also yellow with an absorption maximum of 450nm of a carotenoid pigment[

33]. Since the orange colored WBB had a similar absorption spectrum as others, the orange color may be a reflection of a different internal environment (perhaps pH) in WBB that may allow the same pigment to display a different color. Carotenoids are pigments that can serve as blue light filters by absorbing at 450nm and thus protect from damage by excess light. They could also protect cells from reactive oxygen species arising from light exposure or other sources. The apparent presence of carotenoids or other pigments in all our isolates (even endophytes that may have limited light exposure) as well as every

Curtobacterium reported in literature suggests that pigments could be intimately conserved in

Curtobacterium species as an antioxidant guardian. Colonies of all six

Curtobacterium isolates on tryptic soy agar plates were circular to avoid and generally flat or raised (

Figure 2), which may be reflective of the obligate aerobic nature of

Curtobacterium species[

34], which is interesting for endophytes that appear to be living in oxygen limiting conditions inside plant tissues. Colonies of some of the isolates were mucoid as has been reported for

C. pusillum[

14], which may reflect the ability of some of the isolates to synthesize water-retaining extracellular polysaccharides (EPS), possibly using sugars from the medium.

4.3. Nutritional Preferences of Curtobacterium Species

All six isolates tested were capable of degrading the plant carbohydrate starch and the milk protein casein as well as solubilize phosphate based on plate assays (

Figure 4,

Table 3). Since all strains were isolated as endophytes from plants (fruit, flower, stem), this may be reflective of their reliance on the starch in their environment for nutrition. Casein hydrolysis, mediated by the exoenzyme caseinase, is confirmed by the presence of a clear zone around the bacteria on a milk agar plate and all isolates in this study were caseinase positive. Caseinase is not only found in bacteria associated with milk and dairy products but also appears to be a virulence factor in digesting host proteins that are structurally similar to casein[

35]. All six diverse

Curtobacterium isolates in our study were caseinase positive and the enzyme may perhaps digest casein-like proteins in the host or perhaps remodel their own secreted proteins or extracellular matrix with the protease activity. Indeed, every reference that tested casein hydrolysis reported that the

Curtobacterium isolates were caseinase positive[

28,

36,

37,

38,

39], suggesting that casein hydrolysis by

Curtobacterium species may be universally conserved. Furthermore, casein hydrolysis is one of the confirmatory markers to identify pathogenic

C. flaccumfaciens, as recommended by the US National Seed Health System in the Be 4.3 Selective Media Assay (University of Idaho). It is interesting to note that milk supplementation enhanced the growth of many of the

Curtobacterium isolates (

Figure 4), likely from the enrichment with milk protein, sugars, minerals and vitamins. This suggests that

Curtobacterium growth in culture could be enhanced by adding skim milk.

Phosphate is abundantly present in soil, but most of it is insoluble and inaccessible, making many plants rely on microbes that solubilize phosphate by secreting extracellular phosphatases[

40]. All six isolates in this study could solubilize inorganic phosphate based on a halo on Pikovskayas agar, which contains insoluble calcium phosphate (

Figure 4). This may be indicative of their ability to hydrolyze insoluble phosphate while in soil or within the plant’s internal tissue (fruit, flower, stem) while they are endophytes. Perhaps, the endophytes could utilize structural phosphate present around plant cells or stored in fruits and other tissues[

41].

Curtobacterium has been broadly reported as a phosphate solubilizing bacterium[

10],[

42],[

43], [

44],[

45],[

46] supporting our observation and indicating that the secreted phosphatase activity may be widely conserved. Remarkably, all

Curtobacterium isolates exhibited a highly mucoid and runny phenotype only on phosphate-containing Pikovskayas agar suggesting that phosphate could promote mucoidal growth, perhaps, by stimulating production of water-retaining extracellular polysaccharides or phosphorylated polysaccharides that may be phosphorylated. Indeed, phosphate appeared to be required for EPS production in

Enterobacter sp.[

47]

Citrate utilization as a carbon and energy source by

Curtobacterium species has been rarely published and the reported species were unable to absorb or metabolize citrate[

10,

48] (Kim et al., 2008, Saranya et al., 2013). Some of the isolates in our study- specifically those belonging to the

C. oceanosedimentum group- were able to utilize citrate as observed on Simmons citrate agar, while others did not (

Figure 4). This may suggest local nutritional adaptations of these strains based on their environment. Fruits and other plant organs are rich in nutrients such as minerals and sugars, particularly fructose, sucrose and glucose[

49]. Not surprisingly all six isolates in this study were able to ferment all these three sugars in addition to galactose and arabinose (

Table 4) and the fruit/plant sugars could be supporting the endophytic growth of these

Curtobacterium species. Indeed, many of the strains previously reported appeared to capable of fermenting these sugars[

14], [

38],[

50],[

51].

4.4. Temperature Adaptations of Curtobacterium Species

All

Curtobacterium isolates displayed moderate levels of salt stress tolerance, based on their growth on 7.5% sodium chloride (

Table 5), suggesting that osmotic stress tolerance may be conserved. The ability to grow at various temperatures was surprising. It appears from literature evidence that

Curtobacterium species are generally mesophilic bacteria with an optimum growth temperature of 25-30 °C[

14,

38], with only an isolated report of a strain being able to grow at low temperatures (5 °C)[

52]. Surprisingly, we found five out of six isolates to be cold tolerant, being able to grow comfortably at 6 °C (

Table 5,

Figure 5). This suggests that psychrotolerance may be conserved in two major clusters of

Curtobacterium:

Curtobacterium oceanosedimentum (IPS11, KB1, PBH-A) and

Curtobacterium flaccumfacciens (ST1.1, WBB). The cold adaptation may be necessary for survival of these

Curtobacterium isolates in their endophytic environments, especially with higher water content as in fruits that raise the risk of lethality by icing and freezing.

Only one of the isolates, RMB2 (

Curtobacterium luteum), isolated from tropical fruit rambutan fruit, lacked the ability to grow at low temperatures. Intriguingly, RMB2 showed exceptional heat tolerance in contrast to the other five isolates being able to grow at temperatures as high as 45 °C (

Figure 5). This observation aligns with a previous study demonstrating the ability of

C. luteum isolated from seagrass meadow to grow up to 45 °C[

10] and indicates that

C. luteum isolates of Asian origin may have evolved heat adaptations. Heat tolerant strains of

Curtobacterium could widen their applications in areas such as plant growth promotion in the face of climate change and in commercial enzyme production. In summary, the study of endophytic

Curtobacterium species revealed many conserved traits with variations that may imply local adaptations and the presence of

Curtobacterium isolates in flowers and fruits suggests that vertical transmission is possible to perpetuate the endophytic habit through generations.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we found two new species of Curtobacterium- C. luteum and C. oceanosedimentum as endophytes in plants-specifically in the understudied niches, floral and fruit tissues. Surprisingly, we found nearly all isolates were psychrotolerant and this capacity of Curtobacterium appears to be underevaluated. Only one of the isolates (C. luteum) was distinctly cold sensitive and, exceptionally, turned out to be heat tolerant, suggesting differential evolution of stress tolerance in Curtobacterium species and also implying that Curtobacterium species could be a source of cold active and thermostable enzymes. All the plant isolates in this study, consistent with their environment, were able to digest plant carbohydrates- starch, sucrose and fructose in addition to inorganic phosphate and casein. The growth stimulation of these isolates by milk suggests that Curtobacterium growth in culture could be enhanced through milk supplementation. The endophytic nature of these bacteria not only suggests a potential for plant protection or plant growth promotion, but also implies possible vertical seed-borne transmission to the next generation and these prospects could be tested in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M.; methodology, A.A., R.M.; software, I.F., R.M.; validation, A.A., R.M.; formal analysis, A.A., R.M.; investigation, A.A., S.W., K.B., K.C., K.S. and R.M.; resources, R.M.; data curation, A.A., R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A., S.W., K.B., K.C., K.S. and R.M.; writing—review and editing, S.W., R.M.; visualization, I.F., A.A., R.M.; supervision, R.M.; project administration, R.M.; funding acquisition, R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Darbaker Prize in Microscopical Biology awarded to R.M. and undergraduate research grants awarded by the Pennsylvania Academy of Sciences (2024).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Justin Baker and Allison Cortina for assistance with the isolation of strains.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

| EPS |

Extracellular Polysaccharide |

| IPS11 |

Indian Pipe Stem 1 |

| OD |

Optical Density |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| TSA(B) |

Tryptic Soy Agar (Broth) |

References

- Saddler, G.S. and Guimarāes, P.M. Curtobacterium. In Bergey's Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria, pp. 1-14 . [CrossRef]

- Evseev, P., et al. (2022) Curtobacterium spp. and Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens: Phylogeny, Genomics-Based Taxonomy, Pathogenicity, and Diagnostics. Current issues in molecular biology 44, 889-927. [CrossRef]

- Chase, A.B., et al. (2016) Evidence for Ecological Flexibility in the Cosmopolitan Genus Curtobacterium. Frontiers in microbiology 7, 1874. [CrossRef]

- Osdaghi, E., et al. (2018) Phenotypic and Molecular-Phylogenetic Analysis Provide Novel Insights into the Diversity of Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens. Phytopathology 108, 1154-1164. [CrossRef]

- Khanal, M., et al. (2023) Isolation and Characterization of Bacteria Associated with Onion and First Report of Onion Diseases Caused by Five Bacterial Pathogens in Texas, U.S.A. Plant disease 107, 1721-1729. [CrossRef]

- Sturz, A.V., et al. (1997) Biodiversity of endophytic bacteria which colonize red clover nodules, roots, stems and foliage and their influence on host growth. Biology and Fertility of Soils 25, 13-19. [CrossRef]

- DUNLEAVY, J.M. (1989) Curtobacterium plantarum sp. nov. Is Ubiquitous in Plant Leaves and Is Seed Transmitted in Soybean and Corn†. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 39, 240-249. [CrossRef]

- Munir, S., et al. (2020) Core endophyte communities of different citrus varieties from citrus growing regions in China. Scientific reports 10, 3648. [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, U., et al. (2002) Diversity of grass-associated Microbacteriaceae isolated from the phyllosphere and litter layer after mulching the sward; polyphasic characterization of Subtercola pratensis sp. nov., Curtobacterium herbarum sp. nov. and Plantibacter flavus gen. nov., sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 52, 1441-1454. [CrossRef]

- Saranya, K., et al. (2022) Screening of multi-faceted phosphate-solubilising bacterium from seagrass meadow and their plant growth promotion under saline stress condition. Microbiological research 261, 127080. [CrossRef]

- Patel, M., et al. (2022) Cadmium-Tolerant Plant Growth-Promoting Bacteria Curtobacterium oceanosedimentum Improves Growth Attributes and Strengthens Antioxidant System in Chili (Capsicum frutescens). Sustainability 14, 4335. [CrossRef]

- de Melo Pereira, G.V., et al. (2012) A multiphasic approach for the identification of endophytic bacterial in strawberry fruit and their potential for plant growth promotion. Microbial ecology 63, 405-417. [CrossRef]

- Vimal, S.R., et al. (2019) Plant growth promoting Curtobacterium albidum strain SRV4: An agriculturally important microbe to alleviate salinity stress in paddy plants. Ecological Indicators 105, 553-562. [CrossRef]

- Funke, G., et al. (2005) First description of Curtobacterium spp. isolated from human clinical specimens. Journal of clinical microbiology 43, 1032-1036. [CrossRef]

- Bulgari, D., et al. (2014) Curtobacterium sp. Genome Sequencing Underlines Plant Growth Promotion-Related Traits. Genome announcements 2. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K., et al. (2021) MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38, 3022-3027. [CrossRef]

- Chacon, F.I., et al. (2022) Native Cultivable Bacteria from the Blueberry Microbiome as Novel Potential Biocontrol Agents. Microorganisms 10. [CrossRef]

- Kooner, A. and Soby, S. (2022) Draft Genome Sequence of Curtobacterium sp. Strain MWU13-2055, Isolated from a Wild Cranberry Fruit Surface in Massachusetts, USA. Microbiology resource announcements 11, e0056522. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzini, M. and Zapparoli, G. (2020) Epiphytic bacteria from withered grapes and their antagonistic effects on grape-rotting fungi. International journal of food microbiology 319, 108505. [CrossRef]

- Janisiewicz, W.J. and Buyer, J.S. (2010) Culturable bacterial microflora associated with nectarine fruit and their potential for control of brown rot. Canadian journal of microbiology 56, 480-486. [CrossRef]

- Vega, F.E., et al. (2005) Endophytic bacteria in Coffea arabica L. Journal of basic microbiology 45, 371-380. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.Y., et al. (2019) [Responses of soil microbial communities in mulberry rhizophere to intercropping and nitrogen application.]. Ying yong sheng tai xue bao = The journal of applied ecology 30, 1983-1992. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z., et al. (2021) Complete Genome Sequences of Curtobacterium, Pantoea, Erwinia, and Two Pseudomonas sp. Strains, Isolated from Apple Flower Stigmas from Connecticut, USA. Microbiology resource announcements 10. [CrossRef]

- Harveson, R.M., et al. (2015) Bacterial Wilt of Dry-Edible Beans in the Central High Plains of the U.S.: Past, Present, and Future. Plant disease 99, 1665-1677. [CrossRef]

- Procopio, R.E., et al. (2009) Characterization of an endophytic bacterial community associated with Eucalyptus spp. Genetics and molecular research : GMR 8, 1408-1422. [CrossRef]

- Magnani, G.S., et al. (2010) Diversity of endophytic bacteria in Brazilian sugarcane. Genetics and molecular research : GMR 9, 250-258. [CrossRef]

- Sun, T., et al. (2023) Biodiversity of Endophytic Microbes in Diverse Tea Chrysanthemum Cultivars and Their Potential Promoting Effects on Plant Growth and Quality. 12. [CrossRef]

- Kizheva, Y., et al. (2024) First Report of Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens in Bulgaria. Pathogens 13. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J., et al. (2024) Curtobacterium salicis sp. nov., isolated from willow tree stems in Washington state. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 117, 62. [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.L., et al. (2016) Diversity of endophytic fungal and bacterial communities in Ilex paraguariensis grown under field conditions. World journal of microbiology & biotechnology 32, 61. [CrossRef]

- Osdaghi, E., et al. (2020) Bacterial wilt of dry beans caused by Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens pv. flaccumfaciens: A new threat from an old enemy. Molecular plant pathology 21, 605-621. [CrossRef]

- Stahl, W. and Sies, H. (2003) Antioxidant activity of carotenoids. Molecular aspects of medicine 24, 345-351. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M., et al. (2012) Biological role of pigment production for the bacterial phytopathogen Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii. Applied and environmental microbiology 78, 6859-6865. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, J.C., et al. (2013) Draft Genome Sequence of Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens Strain UCD-AKU (Phylum Actinobacteria). Genome announcements 1. [CrossRef]

- Preda, M. and Mihai, M.M. (2021) Phenotypic and genotypic virulence features of staphylococcal strains isolated from difficult-to-treat skin and soft tissue infections. 16, e0246478. [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.-D., et al. (2023) Curtobacterium caseinilyticum sp. nov., Curtobacterium subtropicum sp. nov. and Curtobacterium citri sp. nov., isolated from citrus phyllosphere. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 73. [CrossRef]

- Krimi, Z., et al. (2023) Euphorbia helioscopia a Putative Plant Reservoir of Pathogenic Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens. Current microbiology 80, 154. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.F., et al. (2007) Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens pv. beticola, A New Pathovar of Pathogens in Sugar Beet. Plant disease 91, 677-684. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.J., et al. (2005) Bacterial Wilt of Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) Caused by Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens in Southeastern Spain. Plant disease 89, 1361. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, H. and Fraga, R. (1999) Phosphate solubilizing bacteria and their role in plant growth promotion. Biotechnology advances 17, 319-339. [CrossRef]

- Weigend, M., et al. (2018) Calcium phosphate in plant trichomes: the overlooked biomineral. Planta 247, 277-285. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.I. and Castro, P.M. (2014) Diversity and characterization of culturable bacterial endophytes from Zea mays and their potential as plant growth-promoting agents in metal-degraded soils. Environmental science and pollution research international 21, 14110-14123. [CrossRef]

- Diez-Mendez, A. and Rivas, R. (2017) Improvement of saffron production using Curtobacterium herbarum as a bioinoculant under greenhouse conditions. AIMS microbiology 3, 354-364. [CrossRef]

- Kirui, C.K., et al. (2022) Diversity and Phosphate Solubilization Efficiency of Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria Isolated from Semi-Arid Agroecosystems of Eastern Kenya. Microbiology insights 15, 11786361221088991. [CrossRef]

- Kandel, S.L., et al. (2017) An In vitro Study of Bio-Control and Plant Growth Promotion Potential of Salicaceae Endophytes. Frontiers in microbiology 8, 386. [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.K. and White, J.F. (2018) Indigenous endophytic seed bacteria promote seedling development and defend against fungal disease in browntop millet (Urochloa ramosa L.). Journal of applied microbiology 124, 764-778. [CrossRef]

- Concórdio-Reis, P., et al. (2018) Effect of mono- and dipotassium phosphate concentration on extracellular polysaccharide production by the bacterium Enterobacter A47. Process Biochemistry 75, 16-21. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K., et al. (2008) Curtobacterium ginsengisoli sp. nov., isolated from soil of a ginseng field. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 58, 2393-2397. [CrossRef]

- Vincente, A.R., et al. (2014) Chapter 5 - Nutritional Quality of Fruits and Vegetables. In Postharvest Handling (Third Edition) (Florkowski, W.J., et al., eds), pp. 69-122, Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, T., et al. (2007) Curtobacterium ammoniigenes sp. nov., an ammonia-producing bacterium isolated from plants inhabiting acidic swamps in actual acid sulfate soil areas of Vietnam. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 57, 1447-1452. [CrossRef]

- Tokmakova, A.D., et al. (2024) Phytopathogenic Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens Strains Circulating on Leguminous Plants, Alternative Hosts and Weeds in Russia. Plants 13. [CrossRef]

- Kuddus, M. and Ramteke, P.W. (2008) A cold-active extracellular metalloprotease from Curtobacterium luteum (MTCC 7529): enzyme production and characterization. The Journal of general and applied microbiology 54, 385-392. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of Curtobacterium species. 16S rRNA sequences of the six Curtobacterium isolates and representative Curtobacterium species were subjected to multiple sequence alignment using CLUSTALW on MEGA11. The alignment was used to prepare a neighbor joining tree with 500 bootstrap replicates. Genbank accessions of reference sequences: C. allii OK275102, C. albidum NR_026156.1, C. ammoniigenes AB266597, C. caseinilyticum OR143695, C. citreum X77436, C. flaccumfaciens AJ312209, C. herbarum AJ310413, C. luteum X77437, C. pusillum AJ784400, Rathayibacter iranicus NR_042575.1 (Microbacteriaceae relative- outgroup).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of Curtobacterium species. 16S rRNA sequences of the six Curtobacterium isolates and representative Curtobacterium species were subjected to multiple sequence alignment using CLUSTALW on MEGA11. The alignment was used to prepare a neighbor joining tree with 500 bootstrap replicates. Genbank accessions of reference sequences: C. allii OK275102, C. albidum NR_026156.1, C. ammoniigenes AB266597, C. caseinilyticum OR143695, C. citreum X77436, C. flaccumfaciens AJ312209, C. herbarum AJ310413, C. luteum X77437, C. pusillum AJ784400, Rathayibacter iranicus NR_042575.1 (Microbacteriaceae relative- outgroup).

Figure 2.

Colony morphology & Gram staining of Curtobacterium isolates. A. Four-to-five-day old colonies on TSA grown at 25 °C were used to document morphology. B. Gram staining was performed on 2-day old colonies and Gram-stained cells were documented at 100X magnification.

Figure 2.

Colony morphology & Gram staining of Curtobacterium isolates. A. Four-to-five-day old colonies on TSA grown at 25 °C were used to document morphology. B. Gram staining was performed on 2-day old colonies and Gram-stained cells were documented at 100X magnification.

Figure 3.

Pigmentation in Curtobacterium isolates. Overnight TSB cultures of bacteria were used for pigment extraction in 100% methanol. A. Spectral scan was performed with a methanol extract of RMB2 as well as the non-pigmented Bacillus subtilis. B. Absorbance at 450nm of all Curtobacterium isolates to quantify pigmentation. Error bars reflect standard deviation across three replicates. Statistical significance was determined using One-way ANOVA and the letters above the bars indicate statistical grouping following Tukey’s post hoc test (p<0.01).

Figure 3.

Pigmentation in Curtobacterium isolates. Overnight TSB cultures of bacteria were used for pigment extraction in 100% methanol. A. Spectral scan was performed with a methanol extract of RMB2 as well as the non-pigmented Bacillus subtilis. B. Absorbance at 450nm of all Curtobacterium isolates to quantify pigmentation. Error bars reflect standard deviation across three replicates. Statistical significance was determined using One-way ANOVA and the letters above the bars indicate statistical grouping following Tukey’s post hoc test (p<0.01).

Figure 4.

Metabolic capabilities of Curtobacterium isolates. A. Upper panel, Bacteria were swabbed on to 3% milk agar and grown for 2 days at 25 °C. Halo indicates positive casein hydrolysis. Lower panel, Graph indicating stimulation of growth of the isolates on milk agar. 20µL drops (OD600 =0.1) of each isolate grown on TSA or milk agar for 5 days and bacteria quantified with absorbance at 600nm. Error bars represent standard deviation and statistical significance was confirmed with T-test. ns, no significant difference; *, p<0.05, **, p<0.01. B. Amylase and phosphatase activity visualized by growth on starch agar and Pikovskayas agar, respectively, for 2 days. Clear zones around bacteria after adding iodine indicate amylase activity. Clear zones on Pikovskayas agar indicate inorganic phosphate solubilization. C. Growth on TSA (control) and Simmons Citrate agar after 5 days. 20uL of overnight cultures (OD600=0.1) spotted in triplicate.

Figure 4.

Metabolic capabilities of Curtobacterium isolates. A. Upper panel, Bacteria were swabbed on to 3% milk agar and grown for 2 days at 25 °C. Halo indicates positive casein hydrolysis. Lower panel, Graph indicating stimulation of growth of the isolates on milk agar. 20µL drops (OD600 =0.1) of each isolate grown on TSA or milk agar for 5 days and bacteria quantified with absorbance at 600nm. Error bars represent standard deviation and statistical significance was confirmed with T-test. ns, no significant difference; *, p<0.05, **, p<0.01. B. Amylase and phosphatase activity visualized by growth on starch agar and Pikovskayas agar, respectively, for 2 days. Clear zones around bacteria after adding iodine indicate amylase activity. Clear zones on Pikovskayas agar indicate inorganic phosphate solubilization. C. Growth on TSA (control) and Simmons Citrate agar after 5 days. 20uL of overnight cultures (OD600=0.1) spotted in triplicate.

Figure 5.

Temperature tolerance of Curtobacterium isolates. A. Upper panel, Overnight TSB cultures diluted to OD600 of 0.1 were spotted in triplicate and incubated at 6 °C or 25 °C for 5 days. Lower panel, Growth was quantified by suspending each replicate in 10mL of sterile water and determining absorbance at 600nm. Error bars are standard deviation. One-way ANOVA was performed followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Letters indicate significance groupings (p<0.01). B. Upper panel. Growth on TSA after 4 days at 42C. Lower panel. Absorbance (OD600) of cultures after incubating 2 days at 25 °C, 42 °C or 45 °C. Error bars represent standard deviation. T-test was performed and significant differences are as follows: * p ≤ 0.05, *** p ≤ 0.001.

Figure 5.

Temperature tolerance of Curtobacterium isolates. A. Upper panel, Overnight TSB cultures diluted to OD600 of 0.1 were spotted in triplicate and incubated at 6 °C or 25 °C for 5 days. Lower panel, Growth was quantified by suspending each replicate in 10mL of sterile water and determining absorbance at 600nm. Error bars are standard deviation. One-way ANOVA was performed followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Letters indicate significance groupings (p<0.01). B. Upper panel. Growth on TSA after 4 days at 42C. Lower panel. Absorbance (OD600) of cultures after incubating 2 days at 25 °C, 42 °C or 45 °C. Error bars represent standard deviation. T-test was performed and significant differences are as follows: * p ≤ 0.05, *** p ≤ 0.001.

Table 1.

Sequence identification of Curtobacterium species. The six isolates and their sources are listed. 16S rRNA contigs were subjected to NCBI Nucleotide search and best matches are listed.

Table 1.

Sequence identification of Curtobacterium species. The six isolates and their sources are listed. 16S rRNA contigs were subjected to NCBI Nucleotide search and best matches are listed.

| Isolate |

Source |

Contig size (bp) |

Best match in NCBI BLAST |

Query

Cover % |

% identity |

Match Accession |

| IPS11 |

Monotropa uniflora (Indian pipe)-stem |

1380 |

Curtobacterium sp. |

100 |

99.13 |

MH043942.1 |

| KB1 |

Rambutan fruit |

1382 |

C. oceanosedimentum |

100 |

99.49 |

OL413667.1 |

| PBH-A |

Hydrangea petal |

1393 |

Curtobacterium sp. |

100 |

99.64 |

MK704290.1 |

| RMB2 |

Rambutan fruit |

1372 |

C.luteum |

100 |

99.05 |

MW052578.1 |

| ST1.1 |

Steak tomato fruit |

1396 |

C. flaccumfaciens |

100 |

99.71 |

DQ015978.1 |

| WBB |

Rough leaf dogwood berry fruit |

1399 |

Curtobacterium sp. |

100 |

99.64 |

MN989052.1 |

Table 2.

Colony morphology analysis of Curtobacterium Isolates. Five-day old colonies streaked for isolation on TSA at 25 °C were assessed for morphological features listed in the table.

Table 2.

Colony morphology analysis of Curtobacterium Isolates. Five-day old colonies streaked for isolation on TSA at 25 °C were assessed for morphological features listed in the table.

| Code |

Probable ID |

Color |

Form |

Margin |

Elevation |

Surface |

| IPS11 |

Curtobacterium sp. |

yellow |

circular |

entire |

raised |

smooth, glistening |

| KB1 |

C. oceanosedimentum |

yellow |

circular |

entire |

raised |

smooth, glistening |

| PBH-A |

Curtobacterium sp. |

yellow |

ovoid |

entire |

raised |

smooth, glistening |

| RMB2 |

C. luteum |

yellow |

ovoid |

entire |

raised |

smooth, glistening |

| ST1.1 |

C. flaccumfaciens |

yellow |

ovoid |

entire |

raised |

smooth, glistening |

| WBB |

Curtobacterium sp. |

orange |

circular |

entire |

raised |

smooth, glistening |

Table 3.

Enzyme tests of Curtobacterium isolates. Amylase, caseinase and phosphatase activities were tested by growing the isolates on 1% starch agar, 3% milk agar and Pikovskayas agar, respectively for 4-5 days at 25 °C. Citrate utilization was tested on Simmons Citrate agar slants as well as plates for 3-4 days. Urea hydrolysis test was performed in urea broth for 3-5 days. Laccase activity was tested on LB medium containing 2,6-dimethoxyphenol for 4-5 days. nd, not determined due to no growth.

Table 3.

Enzyme tests of Curtobacterium isolates. Amylase, caseinase and phosphatase activities were tested by growing the isolates on 1% starch agar, 3% milk agar and Pikovskayas agar, respectively for 4-5 days at 25 °C. Citrate utilization was tested on Simmons Citrate agar slants as well as plates for 3-4 days. Urea hydrolysis test was performed in urea broth for 3-5 days. Laccase activity was tested on LB medium containing 2,6-dimethoxyphenol for 4-5 days. nd, not determined due to no growth.

| Isolate |

Probable ID |

Amylase |

Caseinase |

Phosphatase |

Citrate |

Urease |

Laccase |

| IPS11 |

Curtobacterium sp. |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

| KB1 |

C. oceanosedimentum |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

| PBH-A |

Curtobacterium sp. |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

| RMB2 |

C. luteum |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

| ST1.1 |

C. flaccumfaciens |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

| WBB |

Curtobacterium sp. |

+ |

+ |

+ |

nd |

- |

- |

Table 4.

Sugar Tests of Curtobacterium isolates. Sugar fermentation was tested using phenol red broth supplemented with various sugars (1% final concentration). Yellow color observed in 2-5 dpi was indicative of sugar fermentation (+). Ara (Arabinose), Fru (Fructose), Gal (Galactose), Glu (Glucose), Lac (Lactose), Mal (Maltose), Man (Mannitol), Sor (Sorbitol), Suc (Sucrose), Tre (Trehalose).

Table 4.

Sugar Tests of Curtobacterium isolates. Sugar fermentation was tested using phenol red broth supplemented with various sugars (1% final concentration). Yellow color observed in 2-5 dpi was indicative of sugar fermentation (+). Ara (Arabinose), Fru (Fructose), Gal (Galactose), Glu (Glucose), Lac (Lactose), Mal (Maltose), Man (Mannitol), Sor (Sorbitol), Suc (Sucrose), Tre (Trehalose).

| Isolate |

Probable ID |

Ara |

Fru |

Gal |

Glu |

Lac |

Mal |

Man |

Sor |

Suc |

Tre |

| IPS11 |

Curtobacterium sp. |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

| KB1 |

C. oceanosedimentum |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

| PBH-A |

Curtobacterium sp. |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

| RMB2 |

C. luteum |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

| ST1.1 |

C. flaccumfaciens |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

| WBB |

Curtobacterium sp. |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

Table 5.

Temperature and salt tolerance of Curtobacterium isolates. Salt tolerance was examined by swabbing the isolates on TSA containing 5%, 7.5% and 10% sodium chloride and incubating at 25 °C for 5 days. Cold and heat tolerance was tested by growing the isolates on TSA for up to week at various temperatures; plates were incubated for 2 weeks at 2° C.

Table 5.

Temperature and salt tolerance of Curtobacterium isolates. Salt tolerance was examined by swabbing the isolates on TSA containing 5%, 7.5% and 10% sodium chloride and incubating at 25 °C for 5 days. Cold and heat tolerance was tested by growing the isolates on TSA for up to week at various temperatures; plates were incubated for 2 weeks at 2° C.

| Isolate |

Probable ID |

Salt Tolerance |

Temperature Tolerance |

| 5% |

7.5% |

10% |

2 °C |

6 °C |

25 °C |

37 °C |

42 °C |

| IPS11 |

Curtobacterium sp. |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

| KB1 |

C. oceanosedimentum |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

| PBH-A |

Curtobacterium sp. |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

| RMB2 |

C. luteum |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| ST1.1 |

C. flaccumfaciens |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

| WBB |

Curtobacterium sp. |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).