Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

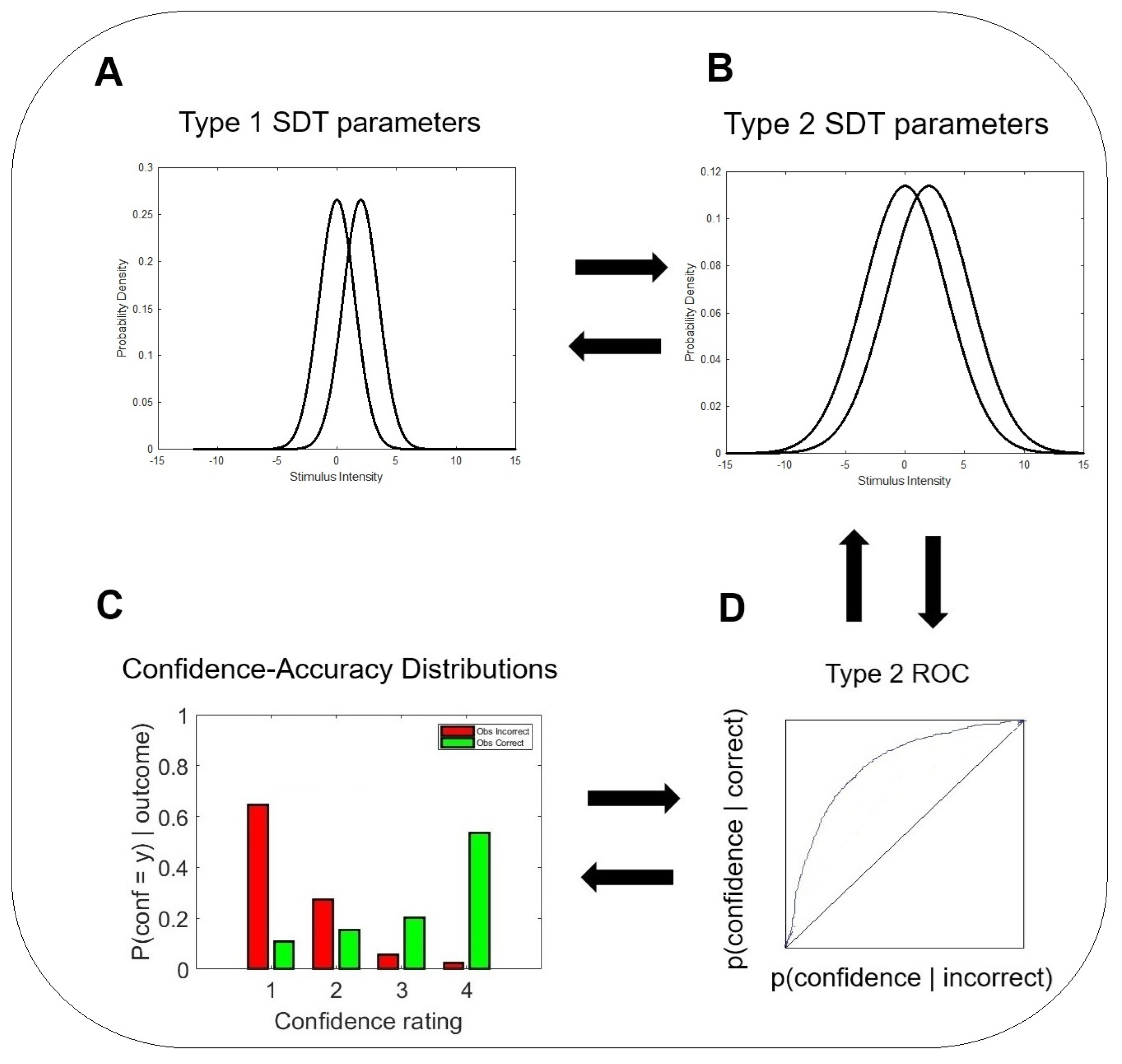

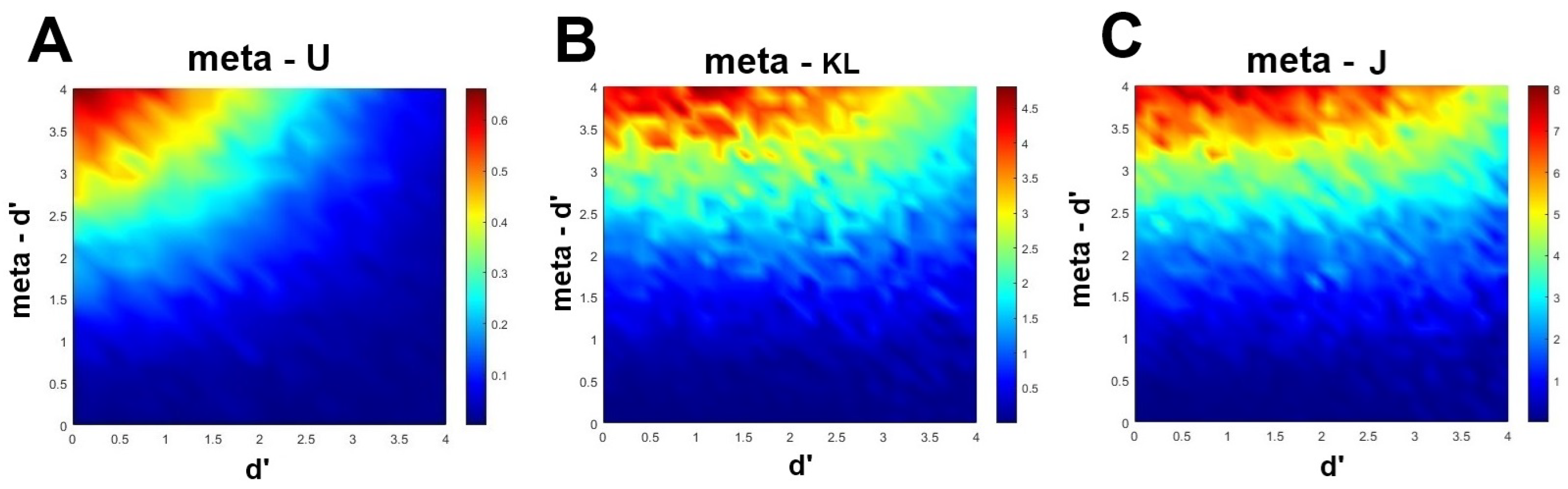

2. An information-Theoretic Approach to Metacognitive Efficiency

2.1. Dayan’s

2.2. Fitousi’s , , and

3. Empirical Validation

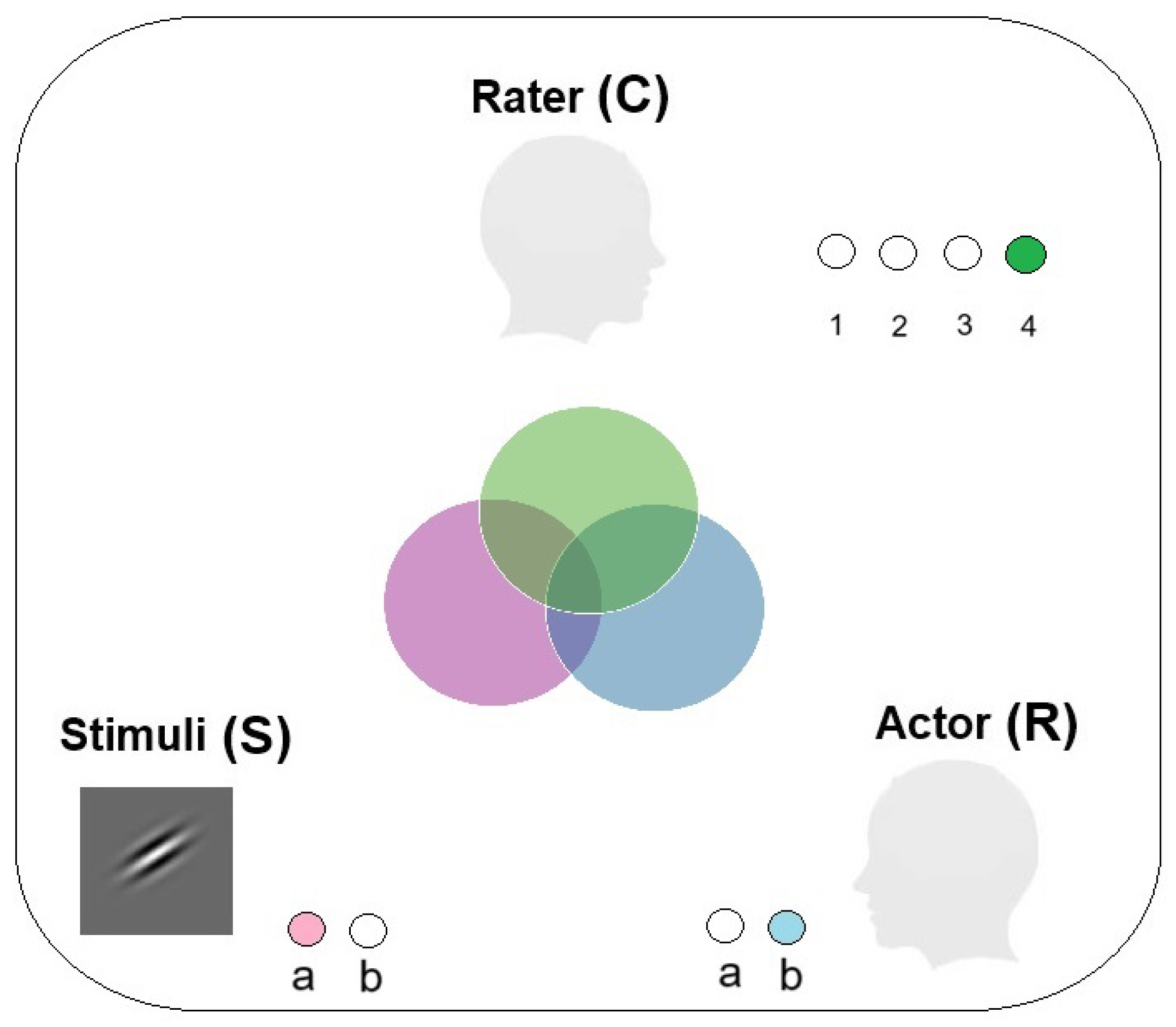

3.1. The Face-Matching Task

3.2. The Data Sets

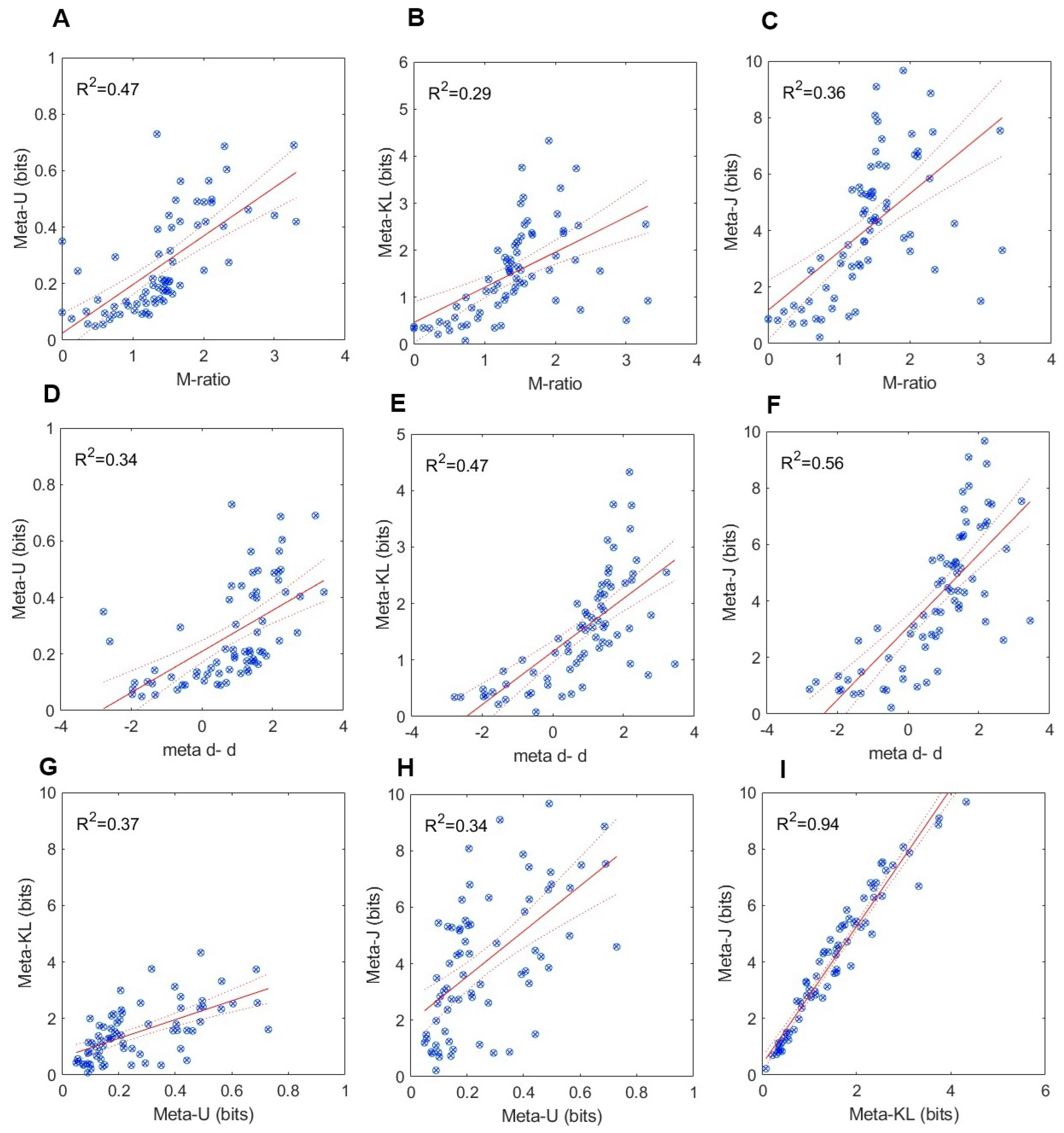

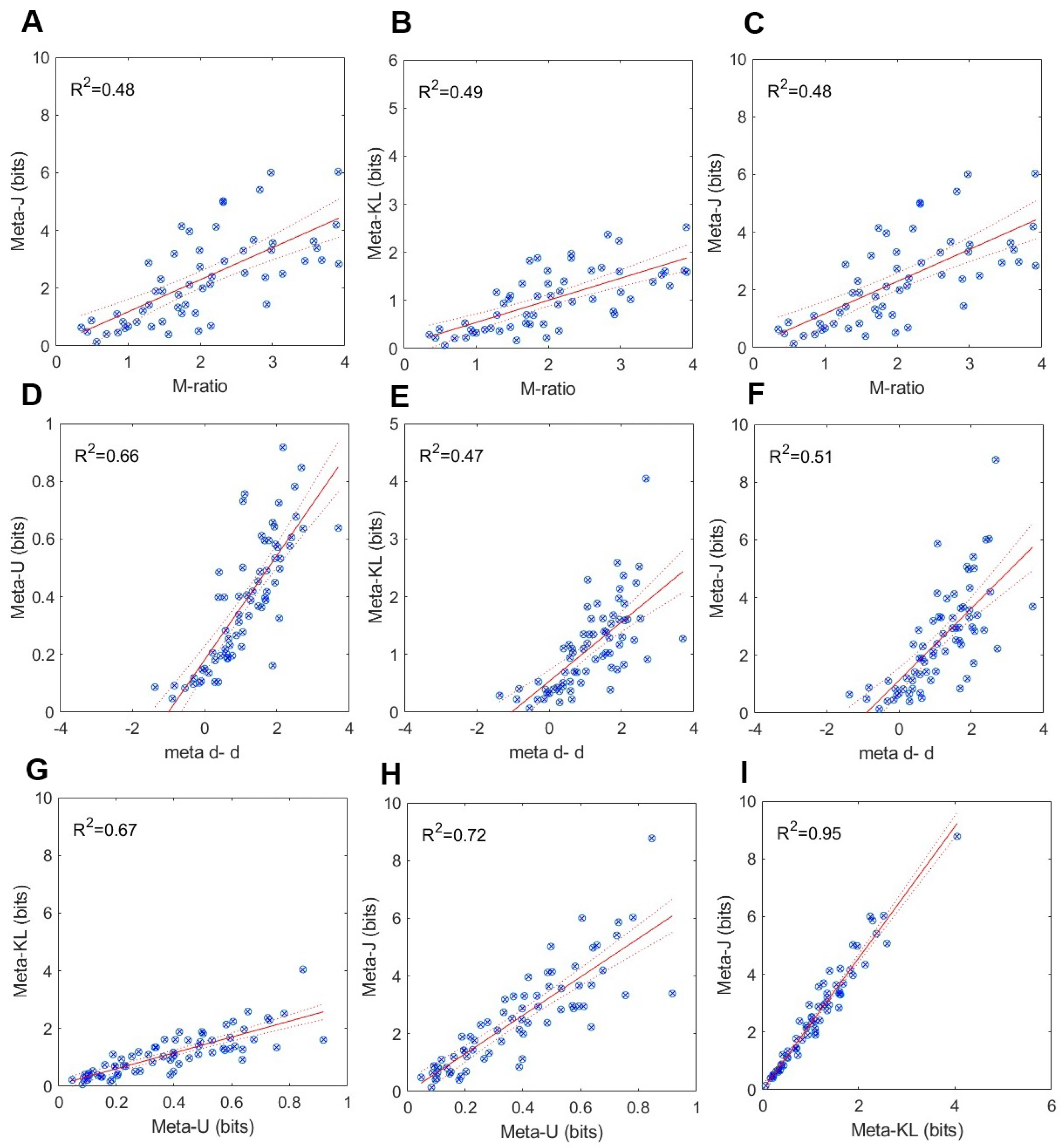

3.3. Results

4. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maniscalco, B.; Lau, H. A signal detection theoretic approach for estimating metacognitive sensitivity from confidence ratings. Consciousness and cognition 2012, 21, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniscalco, B.; Lau, H. Signal detection theory analysis of type 1 and type 2 data: meta-d, response-specific meta-d, and the unequal variance SDT model. In The Cognitive Neuroscience of Metacognition; Springer, 2014; pp. 25–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dayan, P. Metacognitive information theory. Open Mind 2023, 7, 392–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, L.; Rollwage, M.; Dolan, R.J.; Fleming, S.M. Dogmatism manifests in lowered information search under uncertainty. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 31527–31534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, L.; Fleming, S.M.; Dayan, P. Metacognitive computations for information search: Confidence in control. Psychological Review 2023, 130, 604–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, C.S.; Jastrow, J. On small differences in sensation. Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences 1884, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Henmon, V.A.C. The relation of the time of a judgment to its accuracy. Psychological Review 1911, 18, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, H. In consciousness we trust: The cognitive neuroscience of subjective experience; Oxford University Press, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe, J.; Shimamura, A.P. Metacognition: Knowing about knowing; MIT press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, S.M.; Dolan, R.J. The neural basis of metacognitive ability. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2012, 367, 1338–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, S.M.; Weil, R.S.; Nagy, Z.; Dolan, R.J.; Rees, G. Relating introspective accuracy to individual differences in brain structure. Science 2010, 329, 1541–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, S.M. Metacognition and confidence: A review and synthesis. Annual Review of Psychology 2024, 75, 241–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyniel, F.; Schlunegger, D.; Dehaene, S. The sense of confidence during probabilistic learning: A normative account. PLoS computational biology 2015, 11, e1004305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koriat, A.; Goldsmith, M. Monitoring and control processes in the strategic regulation of memory accuracy. Psychological Review 1996, 103, 490–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koriat, A. Monitoring one’s own knowledge during study: A cue-utilization approach to judgments of learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 1997, 126, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koriat, A. The feeling of knowing: Some metatheoretical implications for consciousness and control. Consciousness and Cognition 2000, 9, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persaud, N.; McLeod, P.; Cowey, A. Post-decision wagering objectively measures awareness. Nature neuroscience 2007, 10, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Berg, R.; Zylberberg, A.; Kiani, R.; Shadlen, M.N.; Wolpert, D.M. Confidence is the bridge between multi-stage decisions. Current Biology 2016, 26, 3157–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoven, M.; Lebreton, M.; Engelmann, J.B.; Denys, D.; Luigjes, J.; van Holst, R.J. Abnormalities of confidence in psychiatry: an overview and future perspectives. Translational psychiatry 2019, 9, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahrami, B.; Olsen, K.; Latham, P.E.; Roepstorff, A.; Rees, G.; Frith, C.D. Optimally interacting minds. Science 2010, 329, 1081–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitousi, D. A Signal-detection based confidence-similarity model of face-matching. Psychological Review 2024, 131, 625–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, W.R.; Hake, H.W.; Eriksen, C.W. Operationism and the concept of perception. Psychological Review 1956, 63, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, F.R.; Birdsall, T.G.; Tanner Jr, W.P. Two types of ROC curves and definitions of parameters. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 1959, 31, 629–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, S.J.; Podd, J.V.; Drga, V.; Whitmore, J. Type 2 tasks in the theory of signal detectability: Discrimination between correct and incorrect decisions. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 2003, 10, 843–876. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, S.M.; Daw, N.D. Self-evaluation of decision-making: A general Bayesian framework for metacognitive computation. Psychological Review 2017, 124, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.M.; Swets, J.A. Signal detection theory and psychophysics; Wiley: New York, 1966; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan, N.A.; Creelman, C.D. Detection theory: A user’s guide; Psychology press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, T.O. A comparison of current measures of the accuracy of feeling-of-knowing predictions. Psychological Bulletin 1984, 95, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, S.M. HMeta-d: hierarchical Bayesian estimation of metacognitive efficiency from confidence ratings. Neuroscience of consciousness 2017, 2017, nix007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunimoto, C.; Miller, J.; Pashler, H. Confidence and accuracy of near-threshold discrimination responses. Consciousness and cognition 2001, 10, 294–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniscalco, B.; Peters, M.A.; Lau, H. Heuristic use of perceptual evidence leads to dissociation between performance and metacognitive sensitivity. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics 2016, 78, 923–937. [Google Scholar]

- Shekhar, M.; Rahnev, D. Sources of metacognitive inefficiency. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2021, 25, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guggenmos, M. Measuring metacognitive performance: type 1 performance dependence and test-retest reliability. Neuroscience of consciousness 2021, 2021, niab040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, K.; Shekhar, M.; Rahnev, D. Examining the robustness of the relationship between metacognitive efficiency and metacognitive bias. Consciousness and Cognition 2021, 95, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luce, R.D. Whatever happened to information theory in psychology? Review of general psychology 2003, 7, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knill, D.C.; Pouget, A. The Bayesian brain: the role of uncertainty in neural coding and computation. TRENDS in Neurosciences 2004, 27, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, J. Information-theoretic signal detection theory. Psychological Review 2021, 128, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killeen, P.; Taylor, T. Bits of the ROC: Signal detection as information transmission. Unpublished manuscript 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fitousi, D. Mutual information, perceptual independence, and holistic face perception. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics 2013, 75, 983–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Fitousi, D.; Algom, D. The quest for psychological symmetry through figural goodness, randomness, and complexity: A selective review. i-Perception 2024, 15, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitousi, D. Quantifying Entropy in Response Times (RT) Distributions Using the Cumulative Residual Entropy (CRE) Function. Entropy 2023, 25, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friston, K. The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature reviews neuroscience 2010, 11, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwich, K.H. Information, sensation, and perception; Academic Press: San Diego, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh, J.B.; Mar, R.A.; Peterson, J.B. Psychological entropy: A framework for understanding uncertainty-related anxiety. Psychological Review 2012, 119, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shannon, C. A mathematical theory of communication. The Bell system technical journal 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication,(first published in 1949). Urbana University of Illinois Press 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K. The free-energy principle: a rough guide to the brain? Trends in cognitive sciences 2009, 13, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouget, A.; Drugowitsch, J.; Kepecs, A. Confidence and certainty: distinct probabilistic quantities for different goals. Nature neuroscience 2016, 19, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.H.; Ma, W.J. Confidence reports in decision-making with multiple alternatives violate the Bayesian confidence hypothesis. Nature communications 2020, 11, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullback, S. Information theory and statistics; Courier Corporation, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, R.C. Probability and the Art of Judgment; Cambridge University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cover, T.; Thomas, J. Elements of information theory; John Wiley & Sons, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, J. Jeffrey’s rule, passage of experience, and neo-Bayesianism. In Knowledge representation and defeasible reasoning; Springer, 1990; pp. 245–265. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, A.M.; White, D.; McNeill, A. The Glasgow face matching test. Behavior research methods 2010, 42, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.; Towler, A.; Kemp, R. Understanding professional expertise in unfamiliar face matching. In Forensic face matching: Research and practice; 2021; pp. 62–88. [Google Scholar]

- Megreya, A.M.; Burton, A.M. Unfamiliar faces are not faces: Evidence from a matching task. Memory & Cognition 2006, 34, 865–876. [Google Scholar]

- Megreya, A.M.; Burton, A.M. Hits and false positives in face matching: A familiarity-based dissociation. Perception & Psychophysics 2007, 69, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, R.; Towell, N.; Pike, G. When seeing should not be believing: Photographs, credit cards and fraud. Applied Cognitive Psychology: The Official Journal of the Society for Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 1997, 11, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, A.J.; An, X.; Dunlop, J.; Natu, V.; Phillips, P.J. Comparing face recognition algorithms to humans on challenging tasks. ACM Transactions on Applied Perception (TAP) 2012, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fysh, M.C.; Bindemann, M. The Kent face matching test. British Journal of Psychology 2018, 109, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, S.; Mestry, N.; Portch, E. Individual differences between observers in face matching. In Forensic Face Matching: Research and Practice; 2021; pp. 117–145. [Google Scholar]

- Towler, A.; White, D.; Kemp, R.I. Evaluating training methods for facial image comparison: The face shape strategy does not work. Perception 2014, 43, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R.; White, D.; Van Montfort, X.; Burton, A.M. Variability in photos of the same face. Cognition 2011, 121, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindemann, M.; Attard, J.; Leach, A.; Johnston, R.A. The effect of image pixelation on unfamiliar-face matching. Applied Cognitive Psychology 2013, 27, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megreya, A.M.; Bindemann, M. Feature instructions improve face-matching accuracy. PloS one 2018, 13, e0193455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, M.; Rahnev, D. The nature of metacognitive inefficiency in perceptual decision making. Psychological Review 2021, 128, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).