To provide an analysis of the above equation for gravitational waves and the analysis of the resulting classes of metrics, a representation using null-vectors will be useful. Therefore, in the next few steps it will be shown that Alena Tensor allows representing the energy-momentum tensor of the electromagnetic field with the use of two null-vectors.

3.1. Decomposition of the electromagnetic field using null vectors

At first step one may recall equation (

17) and define new four-vector

obtaining

Since it is know from previous publications, that

and

, therefore above definition also yields

. This property allows to represent

and

using two null-vectors

and

as follows

thus

Next, one may define auxiliary parameter

as

and subtract the linear combination of

and

from both sides

Next, using

for simplicity, one may recall from [

9] coefficients related to the electromagnetic field

relative permeability

volume magnetic susceptibility

relative permittivity

electric susceptibility

and notice, that one obtains Alena Tensor

as

where electromagnetic stress-energy tensor is equal to

and where

actually simplifies, as shown in introduction, to

Completing the definition of the first invariant of the electromagnetic field tensor

, one may define the second invariant

by electric

and magnetic

fields as

where it is known [

28], that

Therefore from (

29) one obtains simplifications

and by defining a useful auxiliary variable

one gets

Finally, defining for simplicity as below

then calculating from (

29) and (

32)

and expressing

, one gets further useful expressions

To simplify further analysis, one may also normalize four-vectors

and

using (

33) as follows

where

(not

) was introduced to avoid confusion related to the previously defined perturbation

. After few calculations using previously derived relationships in (

29)

one may now rewrite the electromagnetic field tensor

as

As shown in [

9] element

is responsible for electric field energy density carried by light, where

was shown as describing energy density of magnetic moment and was linked to charged matter in motion. The element

is a new term and part of equation related to this term may be expressed as

with help of (

37) as

Since

does not actually carry energy but only momentum, it can be associated with some description of spin field effects by analogy to (

22). Using (

33), (

34) (

37) and (

40), electromagnetic field tensor

may be, however, expressed in more useful form. Since

thus

As one may notice, (

38) also allows to simplify (

21) by introducing

what using (

34) yields

and therefore allows to analyze the system using hyperbolic (and trigonometric) functions

One may thus denote normalized Alena Tensor in flat spacetime as

with help of (

27) and above as follows

and notice, that it may be presented after simple calculations using (

45) - (

49) as

Since the expression in the brackets must be equal to

, thus

Therefore, according to (

41), (

42) there must occur

. Indeed, with help of (

34) and (

37) one obtains

and the same equality may be calculated for

what confirms compliance with (

44). Since

is merely auxiliary variable (used only to highlight certain relationships) and thanks to simple algebraic transformations may be expressed in terms of

one may thus further simplify the description of the system. This shows that further, in-depth analysis of the system is also possible, however, modeling and simplifying the description of the electromagnetic field or searching for elementary particles that provide stable solutions requires a separate article (probably several articles). From the perspective of describing gravitational waves, other elements of the description are crucial, which will be discussed next.

Finally, one may notice, that property

in (

38) requires analysis in a complex basis. An example of such a basis are four-vectors

where the angle

was introduced to facilitate further analysis. The null basis product is a simple consequence of equation (

32) as a consequence of taking only the electromagnetic field into account in the analysis. Since reality requires other fields (e.g. electroweak), it can be assumed that changing

into the field tensor corresponding to reality, would probably provide

, which then makes it possible to assume a basis in real numbers. However, since in this paper it is considered the Alena Tensor with the electromagnetic field only, the basis (

56) will be retained for further analysis as an example, especially since the transition to the generalized field in the discussed approach is a fairly simple procedure.

A cursory examination shows that this basis describes the electromagnetic field very well indeed. It has a good representation in conformal geometry (null vectors correspond to points on the equator of the Penrose sphere), where the propagation directions are perpendicular to the time axis (purely spatial), ideal for describing a circularly or elliptically polarized wave in the direction of Poyting vector , where represents the constant phase relation between the electric and magnetic fields. The proposed basis naturally enters the Newman–Penrose formalism, allows for a full spinor representation of the electromagnetic field, where is a typical massless wave, satisfies the wave equation , and since it provides a spin-helicity of +/- 1, it is well suited for further analysis in the QFT framework as a photon wave representation, describing a single-particle state. However, detailed analysis of these issues is beyond the scope of this article.

3.2. Covariant metric, Higgs field, Riemann tensor, Weyl tensor and gravitational waves

Substituting (

41) into (

19) using (

37) and using Alena Tensor properties one gets expression for metric

describing the system in curved spacetime

It turns out that using properties of metrics, one may find a general solution for the inverted metric

. Summarizing the key properties one obtains

where in the last condition it is enough to check the index (0,0), because the null vectors are normalized (

). To simplify the calculations, it is easiest to define auxiliary variable q and start from anstaz with unknown

in

By eliminating the subsequent variables to provide equations (

58), one obtains covariant metric in the form

where invariants of electromagnetic field turns out to be related to the trace

which means that the trace

is also invariant. The supplementary material contains equations confirming the correctness of the derivation.

Using arc ⌢ for simplicity, to emphasize the change to curvilinear description (since values in curvilinear description may be different), one may notice, that considered in curved spacetime trace

yields

. Therefore, the transition to curved spacetime can be understood as solutions with imaginary magnetic field

. It is also worth notice, that for the null basis example (

56), the above metric seems to describe a gravitational wave in conformal geometry, where

plays the role of a conformal factor

. Further analysis in this direction should allow to isolate both the polarization and the relation of

to the Ricci scalar by classical relation

.

Expressing

by null-vectors as in (

49) and requesting

one obtains ugly expression linking

and

q (due to the complexity of the calculations and the result, it is shown in the attached supplementary material with calculations).

However, substituting q as the

function according to (

61)

and denoting

, it appears that this ugly expression (

62) actually expresses following dependence

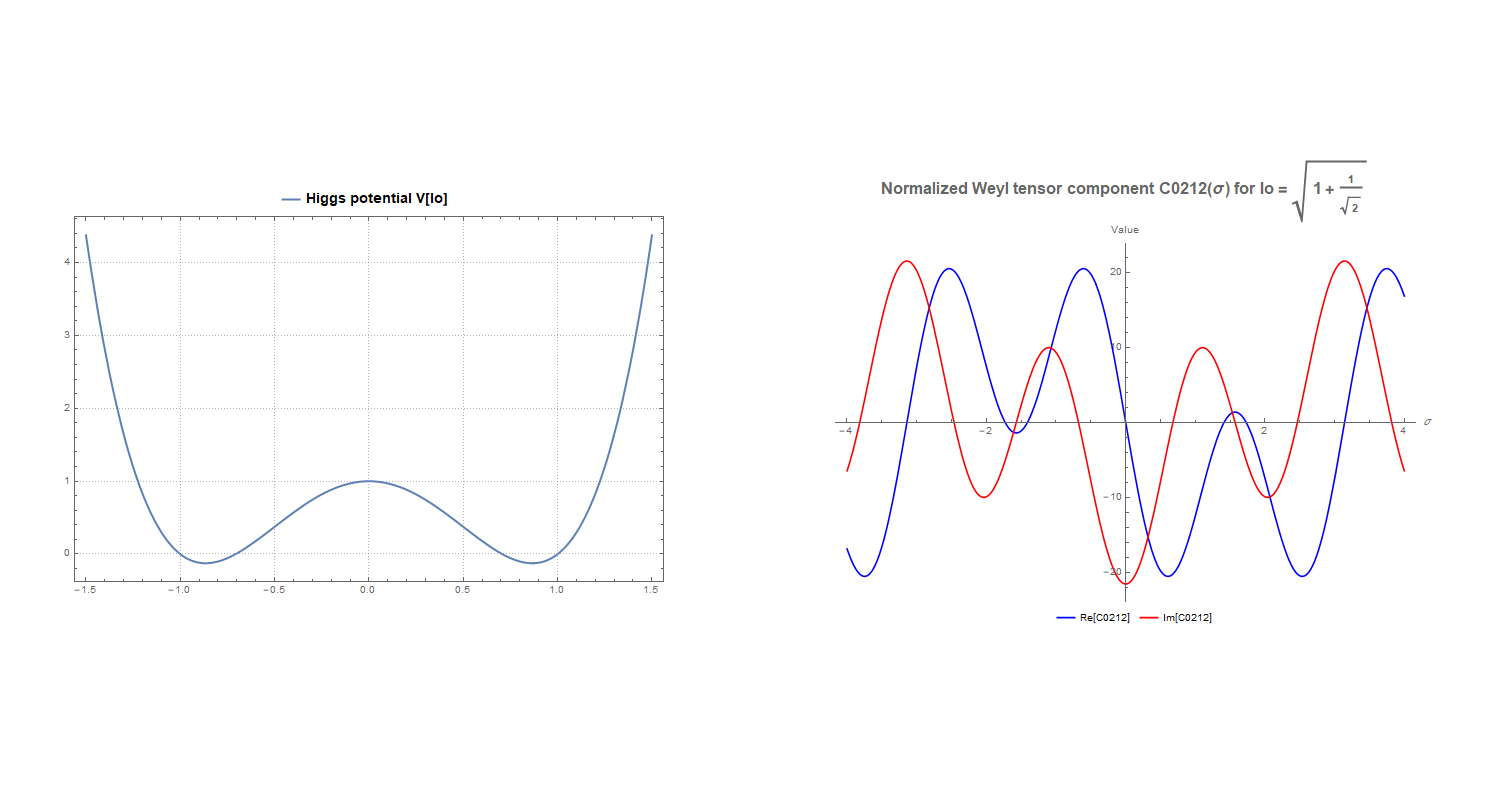

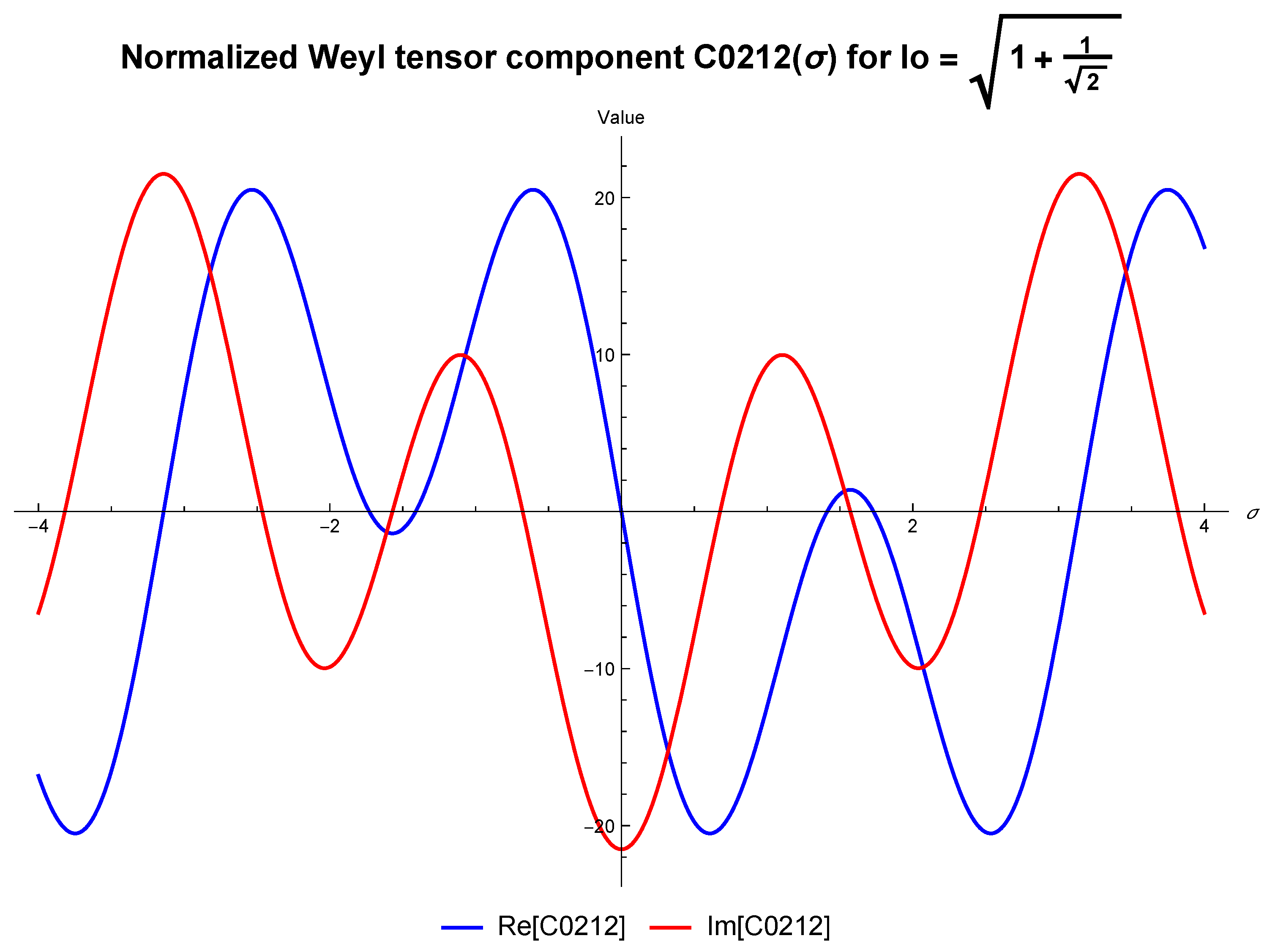

where V is the classical Higgs potential and the broken symmetry in the system can be interpreted as an apparent mismatch of coefficients related to

. The

Figure 1 shows the classic "Mexican sombrero" potential

. Since

is related in equation (

42) to the angle describing the spin, this means that in this solution the spin effect of the field is described by invariant angle (depends only on

) and, according to (

61) it is closely related to the trace of the metric and, consequently, to the Ricci scalar in the curvilinear description and thus to spacetime curvature. This also at least means that to obtain correct results in curved spacetime in the Alena Tensor model, the Higgs-like potential is needed.

Since this paper considers a system with only electromagnetic field, the above described broken symmetry should be considered more as a consequence of the Higgs field in electromagnetism (equivalent to the Abelian mechanism and broken U(1) symmetry) visible in the curvilinear description within GR. However, the above result may contribute to a better understanding of the description of the Higgs field action within the GR containing electromagnetism and connections of the Higgs potential with curvature and spin seen in obtained result. Perhaps it will also help to extend Alena Tensor description to the electroweak field, which will allow to compare the quantum and curvilinear images, which, however, deserves a separate article.

For

the whole metric becomes significantly simplified and symmetric

which means that it may be assumed that adopting the above value leads to some significant and physically important solution of the equations for the system.

Using hyperbolic identities and expressing

then using (

37) one obtains

which allows for further analysis of the Higgs potential. For example, using (

41) and (

46), the relation between electromagnetic energy density

, angle

and spin four-vector

zero component is therefore

Above also explains the origin of

and the connection of spin and Lagrangian with the energy density of the electromagnetic field. Since, according to the considered Alena Tensor approach, in curved spacetime the energy density expressed by

must vanish (the entire stress-energy tensor of the electromagnetic field vanishes), this means, that

and thus

in curved spacetime becomes invariant, which allows to analyze the transition to curved spacetime.

One may now consider what value the Alena Tensor takes in curved spacetime. To do this, it is easiest to analyze the behavior of

. As one may calculate, the determinant of this tensor is 0 and the matrix rank is 2, but, as described in the introduction, it degenerates to

in curved spacetime. It can be seen that in the Alena Tensor approach the metric follows from propagation. However, in curved spacetime the electromagnetic field according to this approach should vanish, remaining present only in the metric and determining geodetic. This can be achieved by degenerating vectors

and

to a single vector in curved spacetime

. However, in such situation the equation (

49) forces this vector to be the four-velocity, divided by the Lorenz factor

which degenerates

from (

51) to the form

As can be easily verified, the exact above relation of variables leads to the vanishing field stress-energy tensor in (

53) upon transition to curved spacetime.

Since the metric is known and

may be expressed by values of

,

in flat spacetime thanks to (

49) this allows to easy obtain the normalized Einstein tensor and Ricci tensor (normalized by

) using the equation (

12). According to the notation used in (

12) one obtains

where Ricci scalar R (normalized according to notation used) may be calculated as

.

The described system seems to be Petrov type D or II [

29], although to be sure, the Weyl tensor should be calculated. This does not seem possible for the general case (without auxiliary assumptions about symmetries), but one could simplify the obtained description considerably, based on the following observation. One may notice, that the vanishing Lorentz factor

in

can be interpreted as an important suggestion for the description of motion in curved spacetime. Such motion would correspond to a stream of particles moving without dilation, a strictly ordered flow without local perturbations, resembling a perfect, infinitely stiff fluid. This means that

should be the Killing tensor and the system should have hidden symmetry (similar to the Carter constant in Kerr solutions).

As shown previously, product of the basis is in considered case , which means that null vectors have global significance for spacetime geometry, thus Killing tensor should have a strong connection with propagation along null vectors (it is not a random symmetry, but a deep feature of spacetime) and this would mean the existence of special wave surfaces, e.g. electromagnetic waves and/or gravitational radiation. This would be also a clear indication that spacetime belongs to the Petrov D or II class and is associated with wave propagation solutions.

Also, the analysis of obtained equations drive to conclusion, that energy (energy density) is not something external to geometry in Alena Tensor approach, but energy is defined by the geometry of spacetime itself. This is a result in the spirit of General Relativity, but it goes even deeper: metric

depends on

, but at the same time

depends on the metric because it is trace of

in this metric. The system itself defines its own energy through the structure of the field, which is similar to the idea of Self-consistent Field [

30] - where the field and the source are inseparable, or Emergent Gravity [

31,

32] - where energy, gravity and geometry arise from a common structure, or Induced Geometry [

33] - where energy comes from deformation of spacetime itself, as e.g. in Sakharov’s theory [

34]. It seems impossible to "decree" energy in Alena Tensor, but it must be calculated from geometry and the system works as a closed causal cycle.

The dependence for

of its norm and trace in curved spacetime (the norm is the square of the trace) is a key property for null space and suggests that

describes isometries related to null wave propagation, similar to pp-wave [

35] and Robinson-Trautman solutions [

36], what is actually expected in considered approach based on electromagnetic stress-energy tensor and result (

57). This would also mean that the Killing tensor is directly related to the energy distribution in spacetime as expected, similar to other GR solutions (eg. Kerr solution), and lead to a rather groundbreaking but also expected result in the context of the discussed approach, that the Killing tensor directly determines the Einstein tensor in main GR equation.

Since is simply the Alena Tensor (stress-energy tensor for the system) divided by , it gives correct conserved values in the Noether formalism (conserved density of energy and momentum). From the definition of the Alena Tensor as the energy-momentum tensor for the system it also follows that is symmetric and vanishes.

Since

this implies that along a geodesic parametrized by proper time

, its total derivative vanishes.

Using the symmetry of

one may note that

Therefore, the condition

holds for arbitrary tangent vectors

, and it indeed follows that

. Therefore normalized Alena Tensor is Killing tensor for considered system.

In this way Alena Tensor theory, in curved spacetime, becomes equivalent to some specific case of General Relativity equation expressed in the following form

where according to (

12) in the above equation

is the classical Einstein tensor in commonly used notation

(classical Einstein tensor).

Thanks to the above, since the Weyl tensor is defined as the part of the Riemann tensor that does not depend on the Ricci tensor, this implies that since Killing tensor determines the Einstein tensor, and the Einstein tensor determines the Ricci tensor, then one could calculate the Weyl tensor by extracting the part of the curvature that does not contain the Ricci tensor. This would also mean that the Christoffel symbols can be expressed as a function of the Killing and Einstein tensors, and the Riemann tensor can be written directly as a function of the Ricci and Killing tensors.

For the system under consideration, one may therefore construct a general Weyl tensor ansatz

, which must contain only components that do not become zero when the trace part is subtracted from the Riemann tensor. It should be of the form

where

It is easy to check that the above tensors are linearly independent and form the basis for the representation of any Weyl tensor in the system under consideration. Analysis of their behavior indicates that

is responsible for "pure" directional propagation, e.g. a gravitational wave propagating along null directions (purely conformal part of the Weyl tensor, described solely by null geometry),

describes non-radiating, "axial" deformation of space, e.g. tidal sequences, consistent with mass motion without undulations,

describes conformal distortion of the background metric itself.

The coefficients

,

,

are not known a priori, but one may determine them with help of Riemann tensor. To obtain Riemann tensor

in the system under consideration, it is enough to assume the following ansatz

t has the following justification

The Riemann tensor satisfies the known algebraic symmetries: . The above ansatz satisfies them automatically.

There are only two tensor objects available in the system: the metric and the Killing tensor . The Riemann tensor must be constructed exclusively from them.

The first term with corresponds to the geometry of a spacetime with constant curvature, as in de Sitter spacetime:

The second term with is the minimal geometrically correct extension that takes into account the presence of non-null energy (represented by ). Its construction provides correct symmetries and enables the reproduction of a non-null Ricci tensor

Other possible combinations (e.g. ) are linearly dependent or asymmetric with respect to the required properties of the Riemann tensor, and do not provide new information in the case under consideration.

The whole creates the most general fourth-order tensor with Riemann symmetries, which can be constructed from available geometric objects.

Computing the contraction of the above Riemann tensor anstaz with

one gets

Since normalized Ricci tensor

is known (

71), therefore considering for simplicity above Riemann tensor anstaz as normalized, one gets

Such normalized form is convenient to use because it allows one to easily obtain both: classical tensors (multiplication by the cosmological constant

) and tensors in the Alena Tensor notation (multiplication by field invariant

).

Next, one may consider normalized trace part of the Riemann tensor

, which provides the necessary symmetries and the vanishing trace in the Weyl tensor. For this to be satisfied, trace part must have the following, classical [

37] form (where Ricci tensor

is considered for simplicity also as normalized):

Since all terms related to

reduce after grouping the components in

, one obtains normalized Weyl tensor in generalized form for the system under consideration

Trace of above Weyl tensor disappears and it has all the expected symmetries. Substituting the metric known from (

57), one obtains the coefficients postulated in the anstaz (

76) and as one may notice from non-zero coefficient

, gravitational waves exist in the system.

One can also demonstrate the existence of gravitational waves using classical analysis using the Weyl tensor components and Newman-Penrose formalism [

38]. Having calculated the above-mentioned tensors and sample basis (

56), one may notice, that four-vector

is purely real. One may thus construct a Newman-Penrose tetrad around it, fitting to the geometry of the system, as follows

The above four-vectors satisfy all the tetrad requirements and lead to only two non-zero NP scalars

what is confirmed in the supplementary materials. Scalar

can be zeroed by a rotation around

without modifying

and the system under consideration is thus Petrov type III or N. However, taking into account the non-zero Ricci tensor and the Bel criteria, considered spacetime must be Petrov type III, since due

is built from reversible metric (

89), thus there does not exist any vector

satisfying

.

Therefore, finally, spacetime described by Alena Tensor with only electromagnetic field may be interpreted as a certain form of the Kundt solution with dust [

39] of Petrov type III, similar to described in [

40,

41]. One may also notice, that additional fields added to the Alena Tensor depending on the new null directions should break the obtained degeneracy leading to the general Petrov type I case.

One may also substitute an example basis (

56) into Weyl tensor to analyze its values. Table 1 presents the values of the key components of the Weyl tensor in this basis.

Table 1.

Component values of the Weyl tensor.

Table 1.

Component values of the Weyl tensor.

| Component |

Value |

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

0 |

One may then solve the system of equations (

37,

55,

64) presenting the results only as a function of

and

. Due to the complex relationships between variables, analytical solution and obtained results are presented in supplementary file. Weyl tensor component values were calculated for the value

adopted for the analysis (

65) and for chosen solution

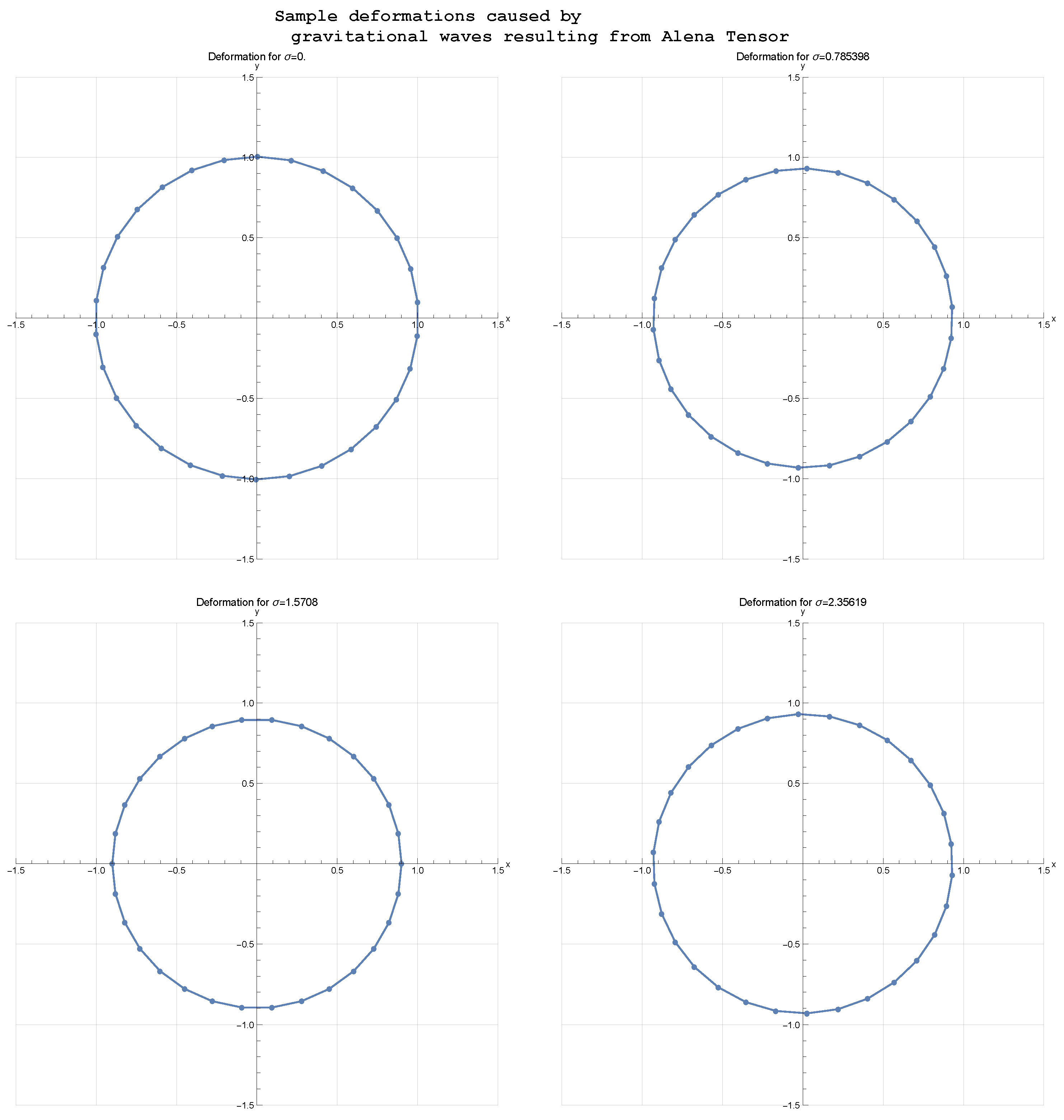

. The

Figure 2 below clearly shows the wave nature of the

component of the Weyl tensor, presenting the result of the calculations performed. Obtained Weyl tensor component

seems to encode the variation of some curvature field along the propagating direction

.

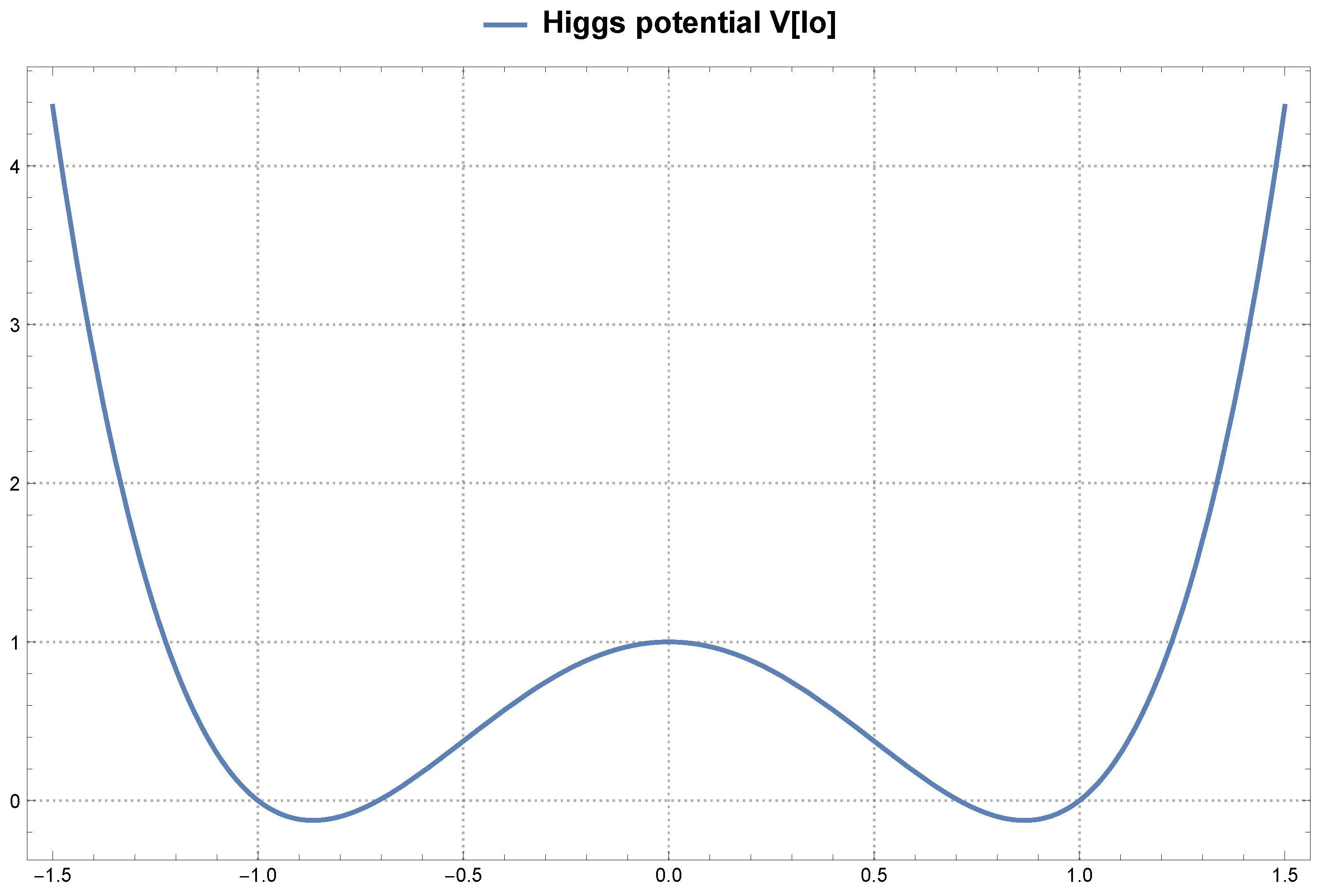

Gravitational waves are often modeled using Gaussian impulse as in [

42], but this can also be done using the dependence of

on

. One may therefore show the deformation effects for an example arrangement of test particles on a circle. In the supplementary materials there are calculations and a gif file presenting animation of this distortion. This animation reveals the typical quadrupolar nature of spacetime distortions induced by gravitational waves (characteristic twisting and stretching).

Figure 3.

Deformation visualization for particles on a circle.

Figure 3.

Deformation visualization for particles on a circle.

The above Weyl tensor components are actually normalized. One may thus present the main GR equation in the Alena Tensor notation (

12) and represent it using the vacuum pressure

as follows

Since the obtained Weyl tensor is normalized (by

- classical notation or by

- Alena Tensor notation) this means that the interpretation from (

20) that gravitational waves in the Alena Tensor approach are in fact propagating vacuum pressure disturbances also seems to be correct.

It is also worth noting that the obtained metric term

can in principle be interpreted as a vacuum energy contribution (effective cosmological constant) as in [

43,

44] playing the role of a metric scaling factor, as e.g. described in [

45].

Additionally, one may invoke the scalar field

associated with the presence of matter, where

. It is known from

Section 2.2 that

is responsible for the presence of sources and in their absence

. Therefore, interpreting whole

as the wave amplitude tensor one would get representation

which would also allow to search for

as a certain wave function.

This approach allows for two simplifications related to the analysis of gravitational waves. Considering the force

responsible for effects related to gravity as shown in (

14) and extracting the acceleration

from it, one gets

since according amendment from [

10]

.

As shown in [

9],

is directly related to the effective potential in gravitational systems which can be calculated from the GR equations. This would allow searching for propagating changes of the effective potential itself (

) similarly as was postulated in [

46]. It would significantly simplify both the calculations and perhaps the methods of detecting gravitational waves, for example, using the approach discussed in [

47].

The second potential simplification results from the possibility of analyzing only the Poynting four-vector as which might also help simplify the calculations and search for experimental proof for the Alena Tensor approach.