Submitted:

16 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Organizing and Interpreting the Alena Tensor Previous Results for Electromagnetism

2.1. Transforming a Curved Path into a Geodesic

- in flat spacetime is the usual, classical energy-momentum tensor of the electromagnetic field

- its trace vanishes in any spacetime, regardless of the considered metric tensor

- in spacetime for which the entire tensor vanishes

- which is expected property of the metric tensor (it was already shown in [11] that indeed may be considered as metric tensor for curved spacetime).

- relative permittivity

- relative permeability

- volume magnetic susceptibility

- is the density of the electromagnetic four-force

- was shown in [10] as related to the presence of gravity in the system.

2.2. Connection with Continuum Mechanics, GR and QFT/QM

- is the density of the radiation reaction four-force

- is density of the four-force related to gravity, where

- is related to the effective potential in the system with gravity.

- - which turns out to be the case of free fall

- which occurs in the case of circular orbits

-

simplified Dirac equation for QED:

- Klein-Gordon equation,

- equivalent of the Schrödinger equation:

2.3. Possible Generalizations to All Gauge Fields

3. Results

3.1. Decomposition of the Electromagnetic Field Using Null Vectors

- relative permeability

- volume magnetic susceptibility

- relative permittivity

- electric susceptibility

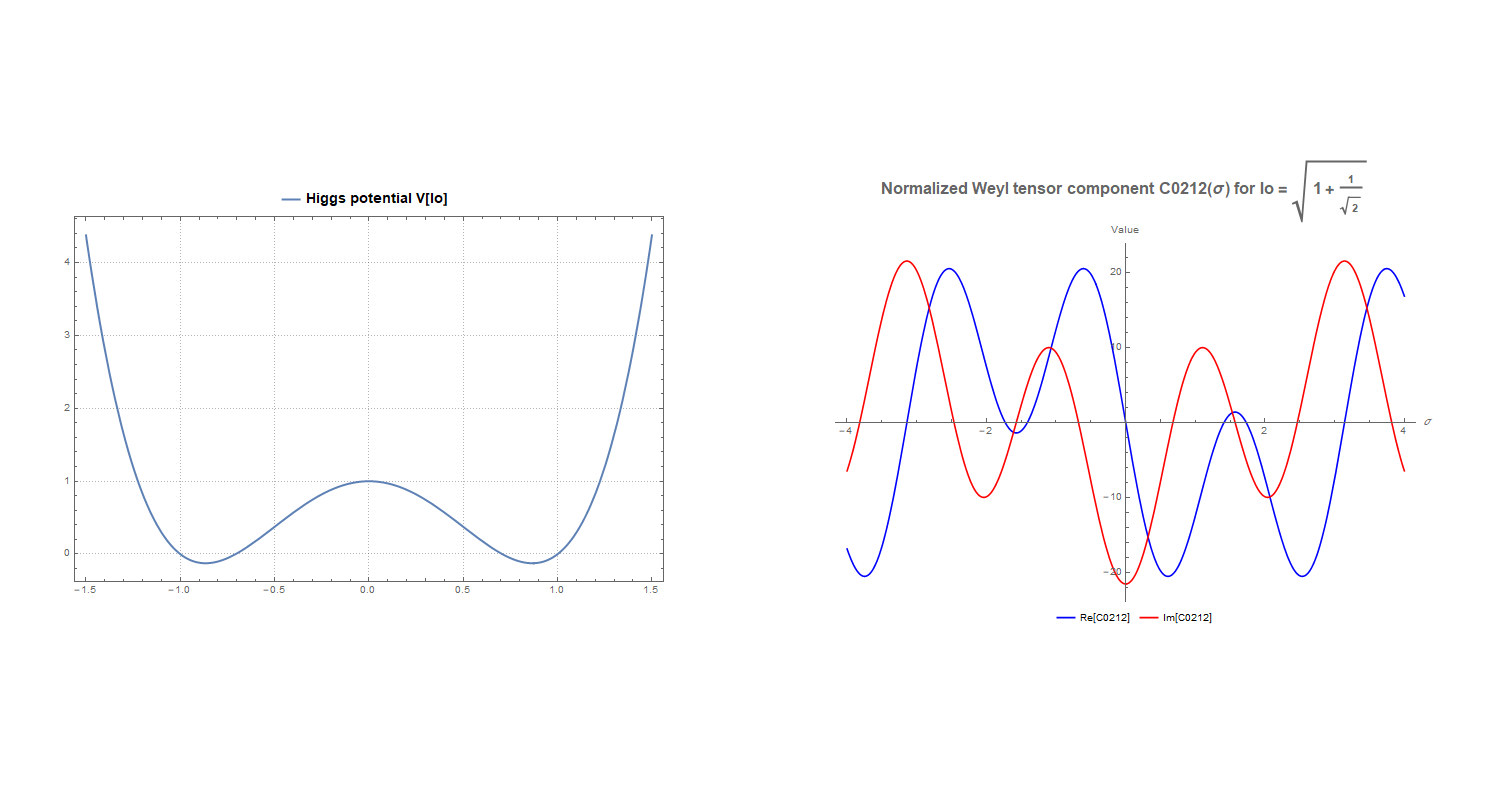

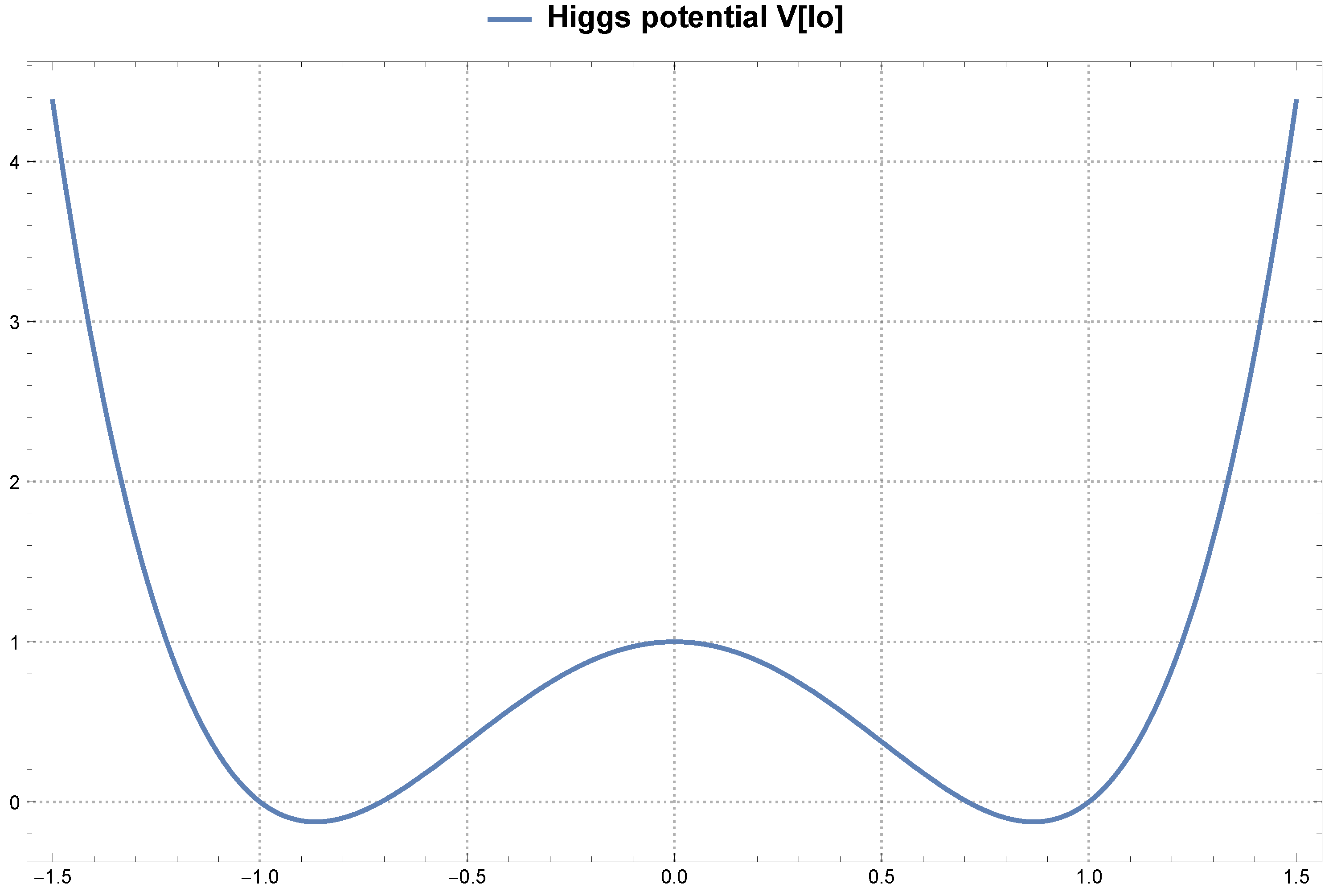

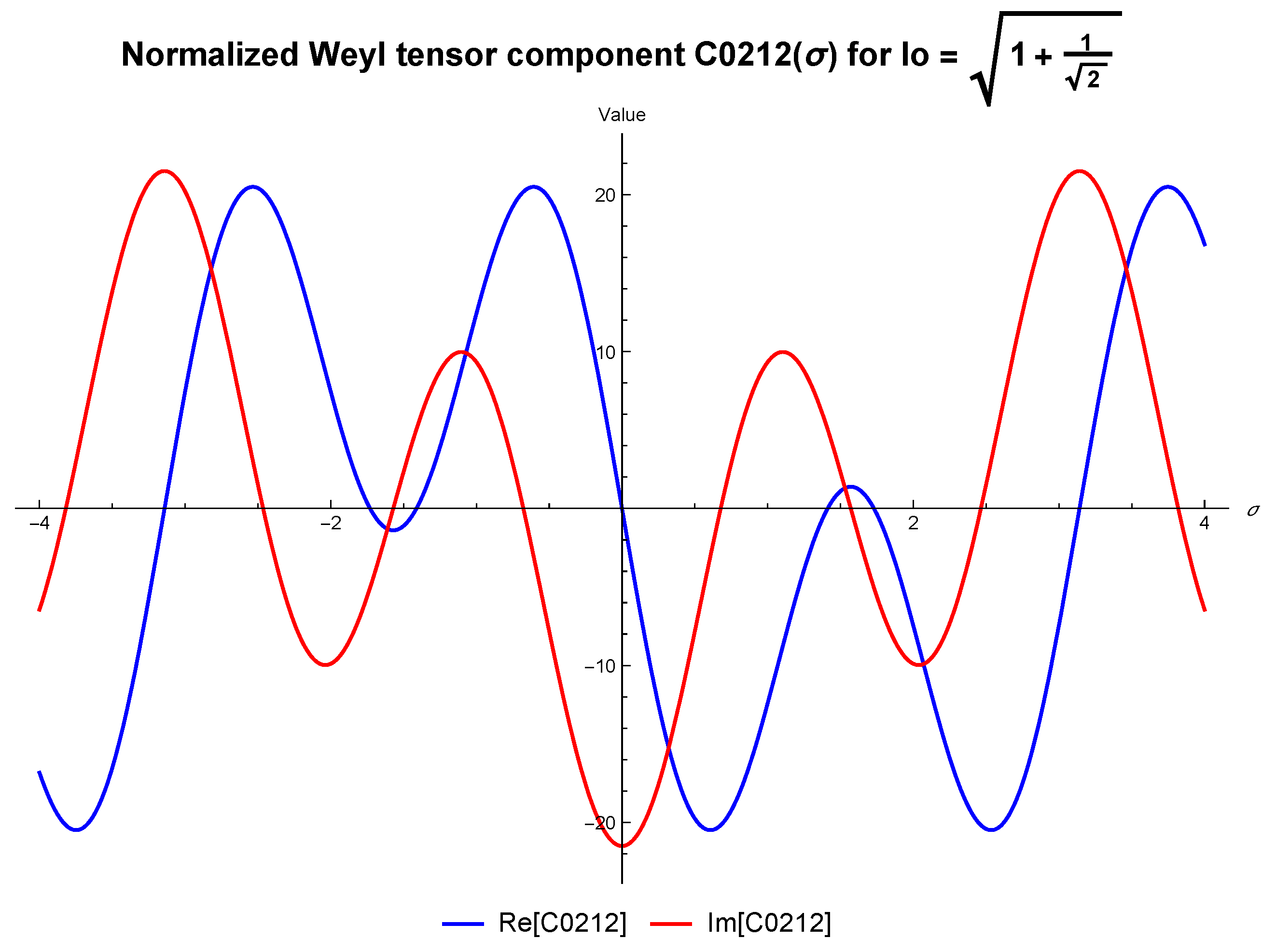

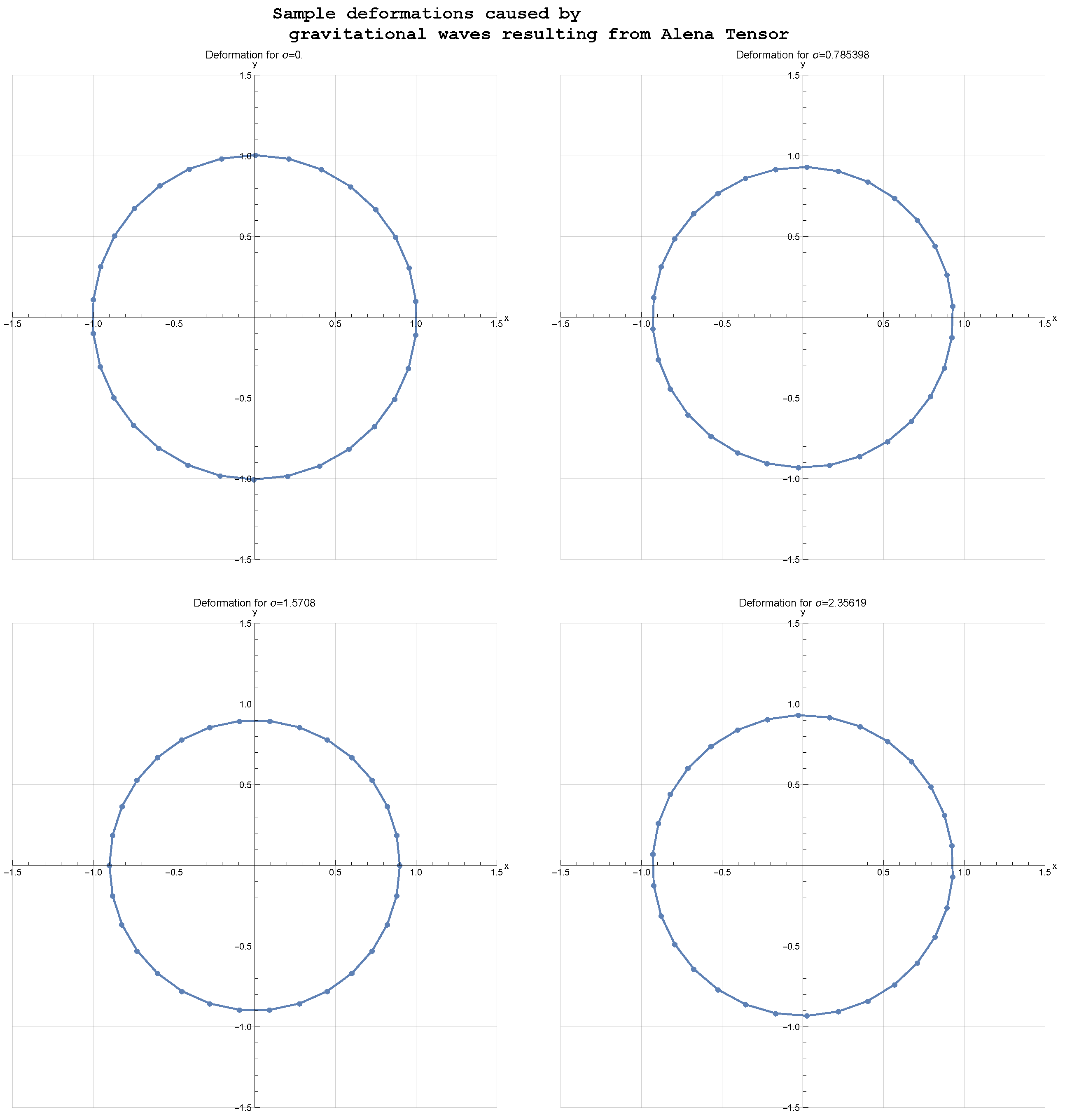

3.2. Covariant Metric, Higgs-Like Potential, Riemann Tensor, Weyl Tensor and Gravitational Waves

- is responsible for "pure" directional propagation, e.g. a gravitational wave propagating along null directions (purely conformal part of the Weyl tensor, described solely by null geometry),

- describes non-radiating, "axial" deformation of space, e.g. tidal sequences, consistent with mass motion without undulations,

- describes conformal distortion of the background metric itself.

- The Riemann tensor satisfies the known algebraic symmetries: . The above ansatz satisfies them automatically.

- There are only two tensor objects available in the system: the metric and the Killing tensor . The Riemann tensor must be constructed exclusively from them.

- The first term with corresponds to the geometry of a spacetime with constant curvature, as in de Sitter spacetime:

- The second term with is the minimal geometrically correct extension that takes into account the presence of non-null energy (represented by ). Its construction provides correct symmetries and enables the reproduction of a non-null Ricci tensor

- Other possible combinations (e.g. ) are linearly dependent or asymmetric with respect to the required properties of the Riemann tensor, and do not provide new information in the case under consideration.

- The whole creates the most general fourth-order tensor with Riemann symmetries, which can be constructed from available geometric objects.

| Component | Value |

|---|---|

| 0 | |

| 0 | |

| 0 | |

| 0 |

3.3. Effective Description of Gravity for the General Case

- is the retarded time, ensuring causal propagation of the field from the source to the observer

- are the current-type multipole moments of the source (), directly related to the mass-current distribution inside the source They encode the full time dependence of the gravitomagnetic field, including both stationary and radiative contributions

- are the toroidal vector spherical harmonics on the unit sphere, representing the purely rotational (divergence-free) part of the vector field on

- corresponds to the spin-dipole (total angular momentum vector ), which dominates in the far zone for an isolated rotating body

- are the higher current multipoles, describing more complex rotational structures of the source (e.g. internal circulation, non-axisymmetric rotation)

4. Conclusion and Discussion

4.1. Conclusions About GR and Gravitational Waves

- The cosmological constant is indeed constant in curved spacetime.

- The energy-momentum tensor of the system in curved spacetime becomes the Killing tensor.

- The available metrics take on a specific form (2+ null vectors and a background metric). Although the paper presents the metric only for a system with electromagnetism and gravity, the Alena Tensor model enforces this metric arrangement in general case.

- The resulting Riemann tensor describes the general case, ensures the formation of the Ricci tensor in contraction, and allows for the derivation of the Weyl tensor.

4.2. Possible Directions of Further Unification

4.3. Conclusions on Energy Conservation in Energy-Momentum Tensors

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Bailes, M.; Berger, B.K.; Brady, P.; Branchesi, M.; Danzmann, K.; Evans, M.; Holley-Bockelmann, K.; Iyer, B.; Kajita, T.; Katsanevas, S.; et al. Gravitational-wave physics and astronomy in the 2020s and 2030s. Nature Reviews Physics 2021, 3, 344–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, B.F. Gravitational wave astronomy. Classical and Quantum Gravity 1999, 16, A131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, R.C.; Ng, K.W. Charting the nanohertz gravitational wave sky with pulsar timing arrays. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2025, 34, 2540013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M.; Nichols, D.A. Outlook for detecting the gravitational-wave displacement and spin memory effects with current and future gravitational-wave detectors. Physical Review D 2023, 107, 064056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borhanian, S.; Sathyaprakash, B. Listening to the universe with next generation ground-based gravitational-wave detectors. Physical Review D 2024, 110, 083040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. Gravitational waves in bimetric MOND. Physical Review D 2014, 89, 024027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahura, S.; Nichols, D.A.; Yagi, K. Gravitational-wave memory effects in Brans-Dicke theory: Waveforms and effects in the post-Newtonian approximation. Physical Review D 2021, 104, 104010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, I.S.; Calvão, M.O.; Waga, I. Gravitational wave propagation in f (R) models: New parametrizations and observational constraints. Physical Review D 2021, 103, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, I.L.; Pelinson, A.M.; de, O. Salles, F. Gravitational waves and perspectives for quantum gravity. Modern Physics Letters A 2014, 29, 1430034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogonowski, P.; Skindzier, P. Alena Tensor in unification applications. Physica Scripta 2024, 100, 015018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogonowski, P. Proposed method of combining continuum mechanics with Einstein Field Equations. International Journal of Modern Physics D 2023, 2350010, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogonowski, P. Developed method: interactions and their quantum picture. Frontiers in Physics 2023, 11, 1264925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logunov, A.; Mestvirishvili, M. Hilbert’s causality principle and equations of general relativity exclude the possibility of black hole formation. Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 2012, 170, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Y. Superposition principle in relativistic gravity. Physica Scripta 2024, 99, 105045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplawski, N.J. Geometrical formulation of classical electromagnetism. arXiv 2008, arXiv:0802.4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.F. Unification of gravitational and electromagnetic fields in Riemannian geometry. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0901.0201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernitskii, A. On unification of gravitation and electromagnetism in the framework of a general-relativistic approach. Gravitation and Cosmology 2009, 15, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholmetskii, A.; Missevitch, O.; Yarman, T. Generalized electromagnetic energy-momentum tensor and scalar curvature of space at the location of charged particle. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1111.2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novello, M.; Falciano, F.; Goulart, E. Electromagnetic Geometry. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1111.2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo Duarte, C. The classical geometrization of the electromagnetism. International Journal of Geometric Methods in Modern Physics 2015, 12, 1560022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojman, S.A. Geometrical unification of gravitation and electromagnetism. The European Physical Journal Plus 2019, 134, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodside, R. Space-time curvature of classical electromagnetism. arXiv preprint gr-qc/0410043 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, H.; Hamm, B.; Hirsch, S.; Wheeler, J.; Zhang, Y. Flatly foliated relativity. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.00967 2019, arXiv:1911.00967 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, N. Evolution of the concept of the curvature in the momentum space. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.08553 2024, arXiv:2404.08553 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, L.; Wazwaz, A.M. Similarity solutions of field equations with an electromagnetic stress tensor as source. Rom. Rep. Phys 2018, 70, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- MacKay, R.; Rourke, C. Natural observer fields and redshift. J Cosmology 2011, 15, 6079–6099. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, N.; Nouri-Zonoz, M. Massive spinor fields in flat spacetimes with nontrivial topology. Physical Review D—Particles, Fields, Gravitation, and Cosmology 2005, 71, 104012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waluk, P.; Jezierski, J. Gauge-invariant description of weak gravitational field on a spherically symmetric background with cosmological constant. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2019, 36, 215006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.Y.; Peng, C.; Li, L.X. Multiway Junction Conditions for Spacetimes with Multiple Boundaries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 133, 131601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, B.; Lamprou, L.; McCandlish, S.; Sully, J. Integral geometry and holography. Journal of High Energy Physics 2015, 2015, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forger, M.; Römer, H. Currents and the energy-momentum tensor in classical field theory: a fresh look at an old problem. Annals of Physics 2004, 309, 306–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaschke, D.N.; Gieres, F.; Reboud, M.; Schweda, M. The energy-momentum tensor(s) in classical gauge theories. Nuclear Physics B 2016, 912, 192–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosyakov, B. Self-interaction in classical gauge theories and gravitation. Physics Reports 2019, 812, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghinoni, B.; Flizikowski, G.; Malacarne, L.C.; Partanen, M.; Bialkowski, S.; Astrath, N.G.C. On the formulations of the electromagnetic stress-energy tensor. Annals of Physics 2022, 443, 169004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G. Wave Surface Symmetry and Petrov Types in General Relativity. Symmetry 2024, 16, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignat’ev, Y.G. The self-consistent field method and the macroscopic universe consisting of a fluid and black holes. Gravitation and Cosmology 2019, 25, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Emergent gravity paradigm: recent progress. Modern Physics Letters A 2015, 30, 1540007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volovik, G. Fermi-point scenario for emergent gravity. arXiv preprint arXiv:0709.1258 2007, arXiv:0709.1258 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, A.; Surya, S.; Versteegen, F. Induced spatial geometry from causal structure. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2019, 36, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakharov, A.D. Vacuum quantum fluctuations in curved space and the theory of gravitation. General Relativity and Gravitation 2000, 32, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sämann, C.; Steinbauer, R.; Švarc, R. Completeness of general pp-wave spacetimes and their impulsive limit. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2016, 33, 215006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, W. Robinson-Trautman solutions to Einstein’s equations. General Relativity and Gravitation 2017, 49, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrov, I. Curvature of space and time, with an introduction to geometric analysis; Vol. 93, American Mathematical Soc., 2020.

- Jizba, P.; Mudruňka, K. Newman-Penrose formalism and exact vacuum solutions to conformal Weyl gravity. Physical Review D 2024, 110, 124006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster Pérez, A. Kundt spacetimes in general relativity and supergravity. PhD thesis, Vrije U., Amsterdam, 2007.

- Kuchynka, M.; Pravdová, A. Weyl type N solutions with null electromagnetic fields in the Einstein-Maxwell p-form theory. General Relativity and Gravitation 2017, 49, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervik, S.; Ortaggio, M.; Pravda, V. Universal electromagnetic fields. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2018, 35, 175017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Guha, S. Memory effect of gravitational wave pulses in PP-wave spacetimes. Physica Scripta 2024, 99, 075023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Reformulation of the cosmological constant problem. Physical Review Letters 2020, 125, 051301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueorguiev, V.G.; Maeder, A. Revisiting the Cosmological Constant Problem within Quantum Cosmology. Universe 2020, 6, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, A. Defining geometric gauge theory to accommodate particles, continua, and fields. Journal of Mathematical Physics 2024, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, G. Scalar induced gravitational waves review. Universe 2021, 7, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athron, P.; Balázs, C.; Fowlie, A.; Morris, L.; Searle, W.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y. PhaseTracer2: from the effective potential to gravitational waves. The European Physical Journal C 2025, 85, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossos, S.; Vossos, E.; Massouros, C.G. The Relation between General Relativity’s Metrics and Special Relativity’s Gravitational Scalar Generalized Potentials and Case Studies on the Schwarzschild Metric, Teleparallel Gravity, and Newtonian Potential. Particles 2021, 4, 536–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maartens, R.; Bassett, B.A. Gravito-electromagnetism. Classical and Quantum Gravity 1998, 15, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, M.L. A note on the gravitoelectromagnetic analogy. Universe 2021, 7, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bini, D.; Mashhoon, B.; Obukhov, Y.N. Gravitomagnetic helicity. Physical Review D 2022, 105, 064028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.; Hu, J.; Yu, H. Quantum gravitomagnetic interaction. Physical Review D 2024, 109, 126016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, A.E.; Vallejo-Peña, S.A. Gravitoelectromagnetic quadrirefringence. Physics of the Dark Universe 2024, 44, 101492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.; de Montigny, M.; Khanna, F. Abelian and non-Abelian Weyl gravitoelectromagnetism. Annals of Physics 2020, 418, 168182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, A.; Luna, C.; Ramos, J. Retarded solutions for Weyl gravitoelectromagnetic fields. Canadian Journal of Physics 2023, 101, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, G.O. Extended gravitoelectromagnetism. I. Variational formulation. European Physical Journal Plus 2021, 136, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, E.; Kent, B.; Balaji, H.P. Gravito-electromagnetism, Kerr-Schild and Weyl double copies; a unified perspective. Journal of High Energy Physics 2025, 2025, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, L. Gravitational radiation from post-Newtonian sources and inspiralling compact binaries. Living reviews in relativity 2014, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulart, É.; Bergliaffa, S.E.P. Nonlinear electrodynamics nonminimally coupled to gravity: Symmetric-hyperbolicity and causal structure. APS, 2022, Vol. 105, p. 024021. [CrossRef]

- Rakitzis, T.P. Spatial wavefunctions of spin. Physica Scripta 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Quantum Gravity; Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Barbour, J. The End of Time: The Next Revolution in Our Understanding of the Universe; Oxford University Press, 1999.

- D’Amico, G.; Kaloper, N. Power-law inflation satisfies Penrose’s Weyl curvature hypothesis. Physical Review D 2022, 106, 103503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jizba, P.; Mudruňka, K. Newman-Penrose formalism and exact vacuum solutions to conformal Weyl gravity. Physical Review D 2024, 110, 124006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoris, D.; Ong, Y.C. Understanding gravitational entropy of black holes: a new proposal via curvature invariants. Physical Review D 2022, 105, 104017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozziello, S.; De Falco, V.; Ferrara, C. Comparing equivalent gravities: common features and differences. The European Physical Journal C 2022, 82, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P.; Adhikari, R.X.; Adya, V.B.; et al. Tests of general relativity with GW170817. Physical review letters 2019, 123, 011102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.; Alexandre, B.; Magueijo, J.; Pezzelle, M. Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking in Graviweak Theory. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.17935 2025, arXiv:2505.17935 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaposhnikov, M.; Shkerin, A.; Zell, S. Standard model meets gravity: Electroweak symmetry breaking and inflation. Physical Review D 2021, 103, 033006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burda, P.; Gregory, R.; Moss, I.G. Gravity and the stability of the Higgs vacuum. Physical review letters 2015, 115, 071303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlow, D.; Heidenreich, B.; Reece, M.; Rudelius, T. Weak gravity conjecture. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2023, 95, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varani, E. Torsional Effects in the Coupling between Gravity and Spinors-Yukawa Gravity. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.17158 2025, arXiv:2505.17158 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.N.; Soo, C. Standard model with gravity couplings. Physical Review D 1996, 53, 5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, A.; Lippoldt, S. Quantum gravity and Standard-Model-like fermions. Physics Letters B 2017, 767, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volovik, G. From Landau two-fluid model to de Sitter Universe. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.04392 2024, arXiv:2410.04392 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josset, T.; Perez, A.; Sudarsky, D. Dark energy from violation of energy conservation. Physical review letters 2017, 118, 021102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Quaglia, R.; German, G. A comparison between the Jordan and Einstein frames in Brans-Dicke theories with torsion. The European Physical Journal Plus 2023, 138, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.Z. Energy-momentum non-conservation on noncommutative spacetime and the existence of infinite spacetime dimension. arXiv preprint arXiv:0710.4619 2007, arXiv:0710.4619 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velten, H.; Caramês, T.R. To conserve, or not to conserve: A review of nonconservative theories of gravity. Universe 2021, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastall, P. Generalization of the Einstein theory. Physical Review D 1972, 6, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghnezhad, N. Wormhole solutions in generalized Rastall gravity. International Journal of Geometric Methods in Modern Physics, 00; 2550153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calogero, S.; Velten, H. Cosmology with matter diffusion. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2013, 2013, 025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, A.; Lochan, K.; Satin, S.; Singh, T.P.; Ulbricht, H. Models of wave-function collapse, underlying theories, and experimental tests. Reviews of Modern Physics 2013, 85, 471–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankaranarayanan, S.; Johnson, J.P. Modified theories of gravity: Why, how and what? General Relativity and Gravitation 2022, 54, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazlollahi, H. Non-conserved modified gravity theory. The European Physical Journal C 2023, 83, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anero, J.; Martin, C.P. Unimodular gravity and the gauge/gravity duality. Physical Review D 2023, 107, 046001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo-Rubio, R.; Garay, L.J.; García-Moreno, G. Unimodular gravity vs general relativity: a status report. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2022, 39, 243001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, E.; Velasco-Aja, E. A primer on unimodular gravity. In Handbook of Quantum Gravity; Springer, 2023; pp. 1–43. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).