Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protein Datasets

2.2. Computational Analyses of Viral and Host Proteins

3. Results and Discussion

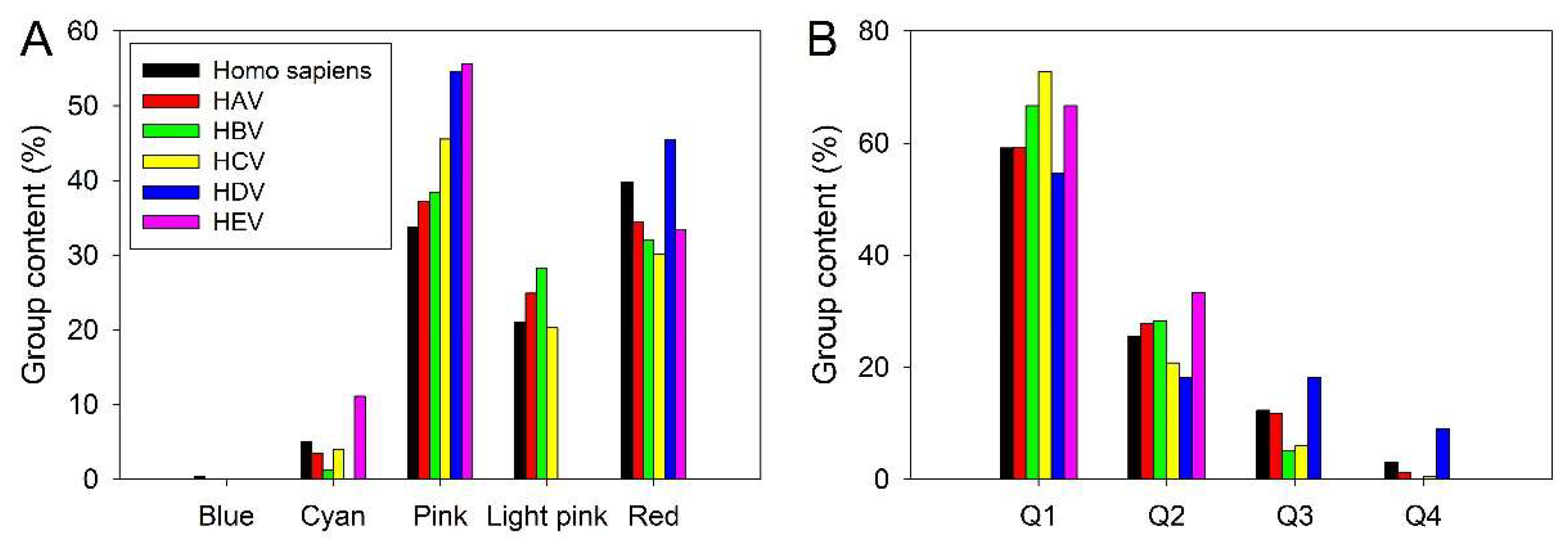

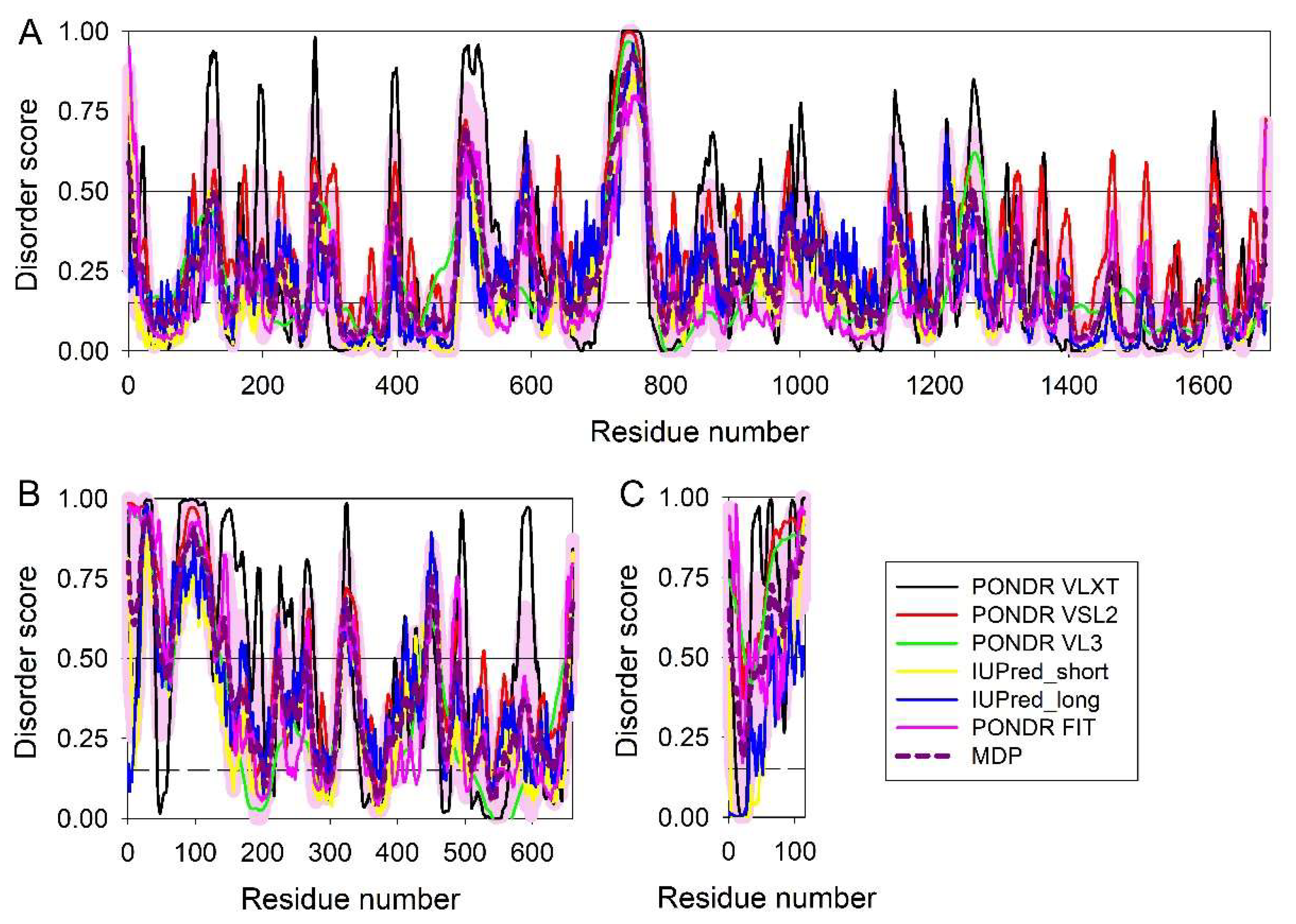

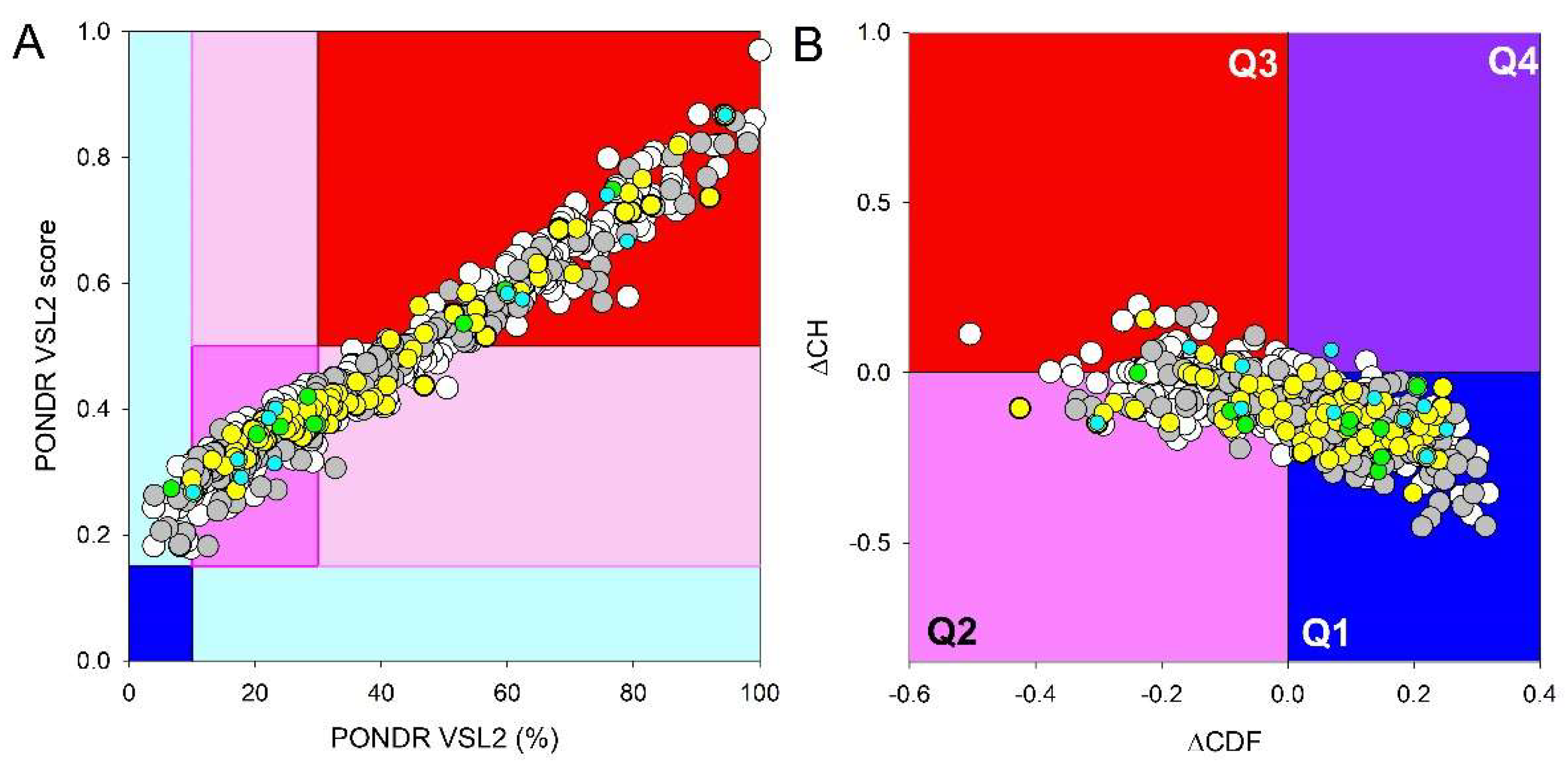

3.1. Intrinsic Disorder in Proteomes of Human Hepatitis Viruses

3.1.1. Hepatitis A Virus

3.1.2. Hepatitis B Virus

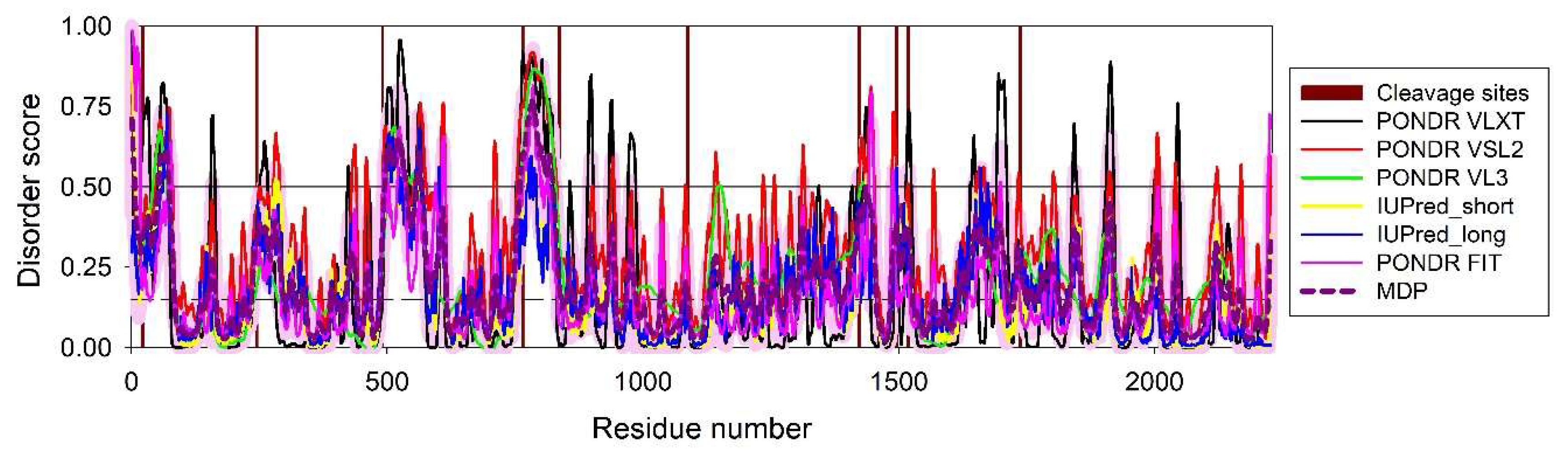

3.1.3. Hepatitis C Virus

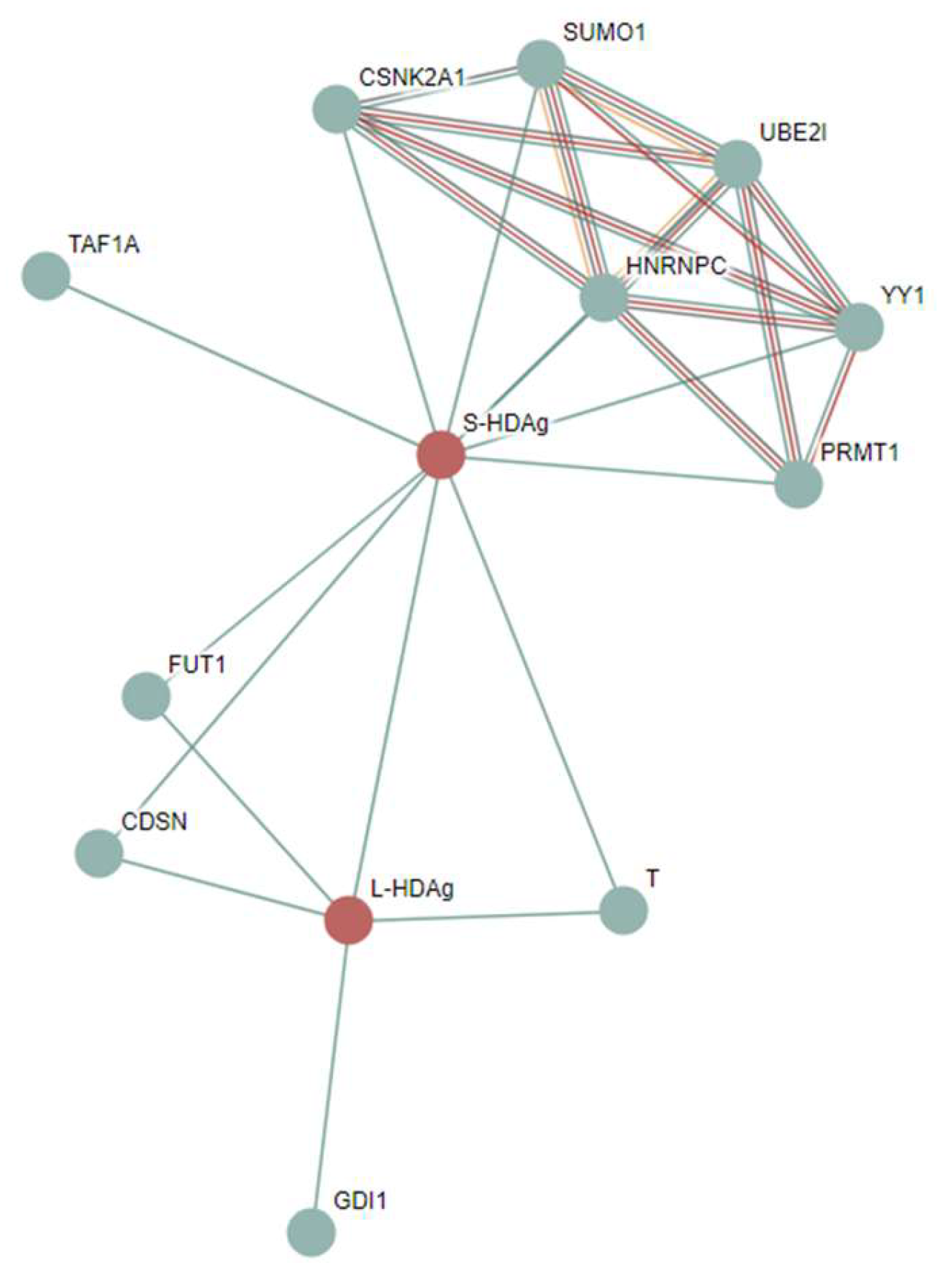

3.1.4. Hepatitis D Virus

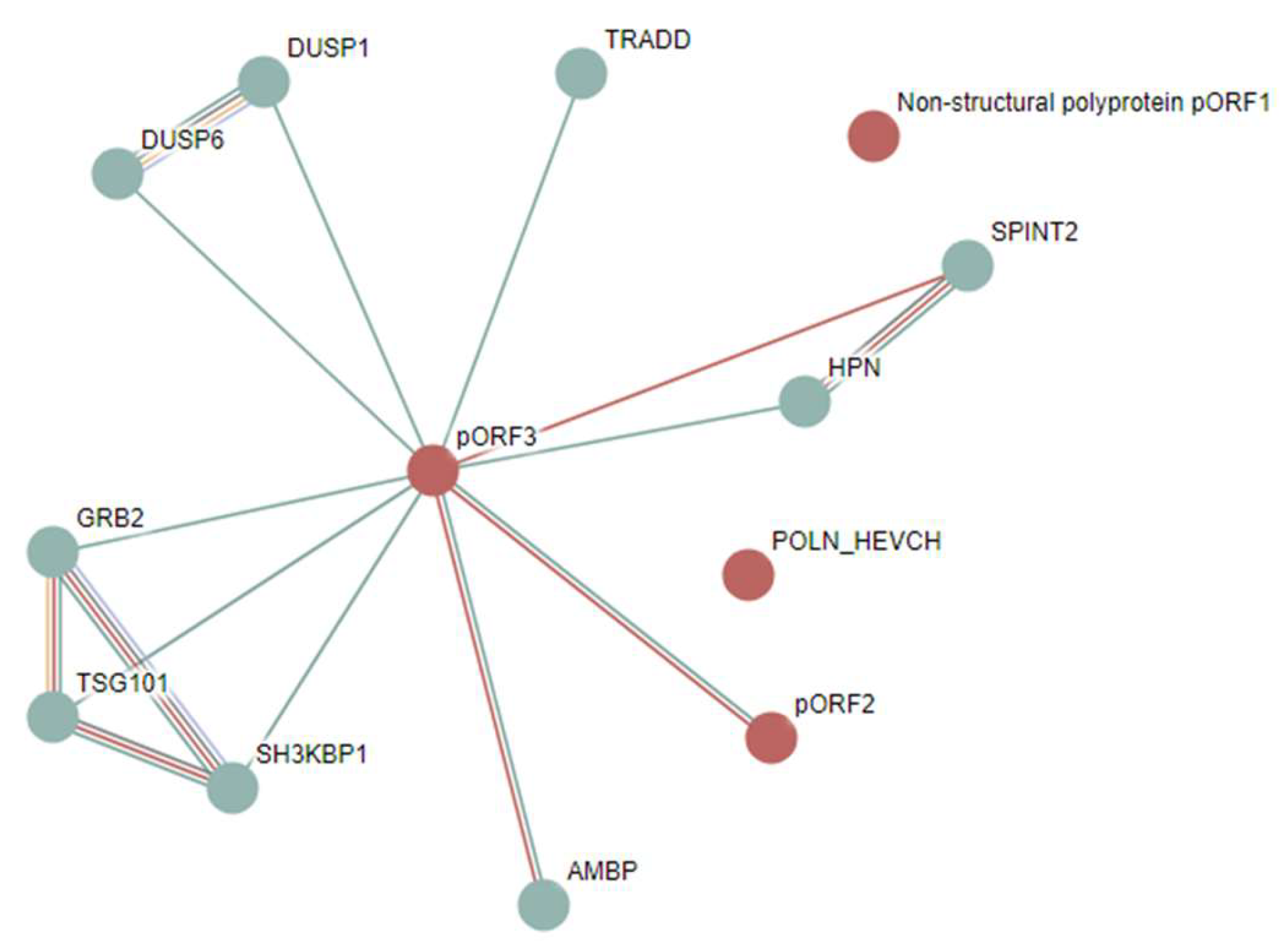

3.1.5. Hepatitis E Virus

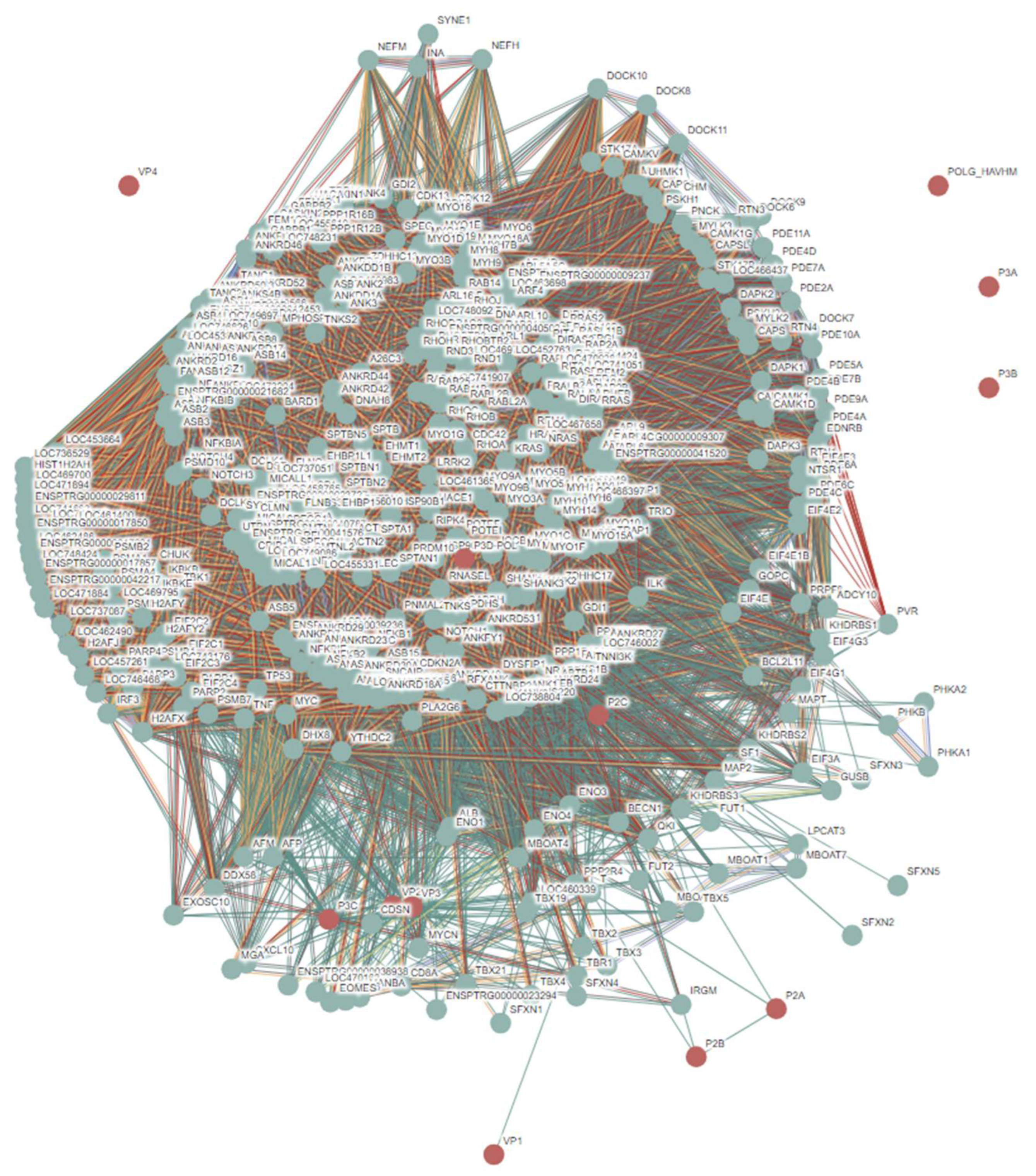

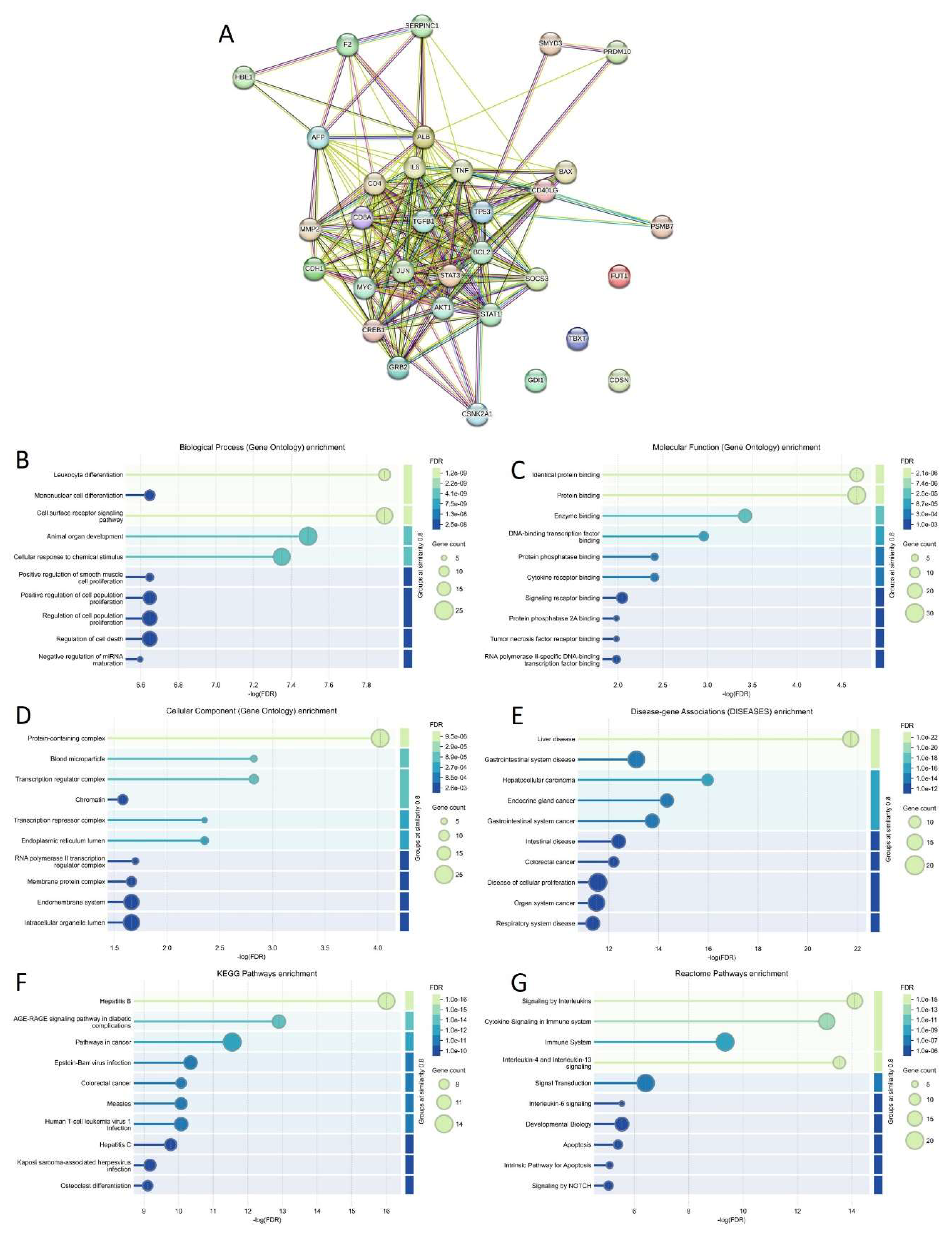

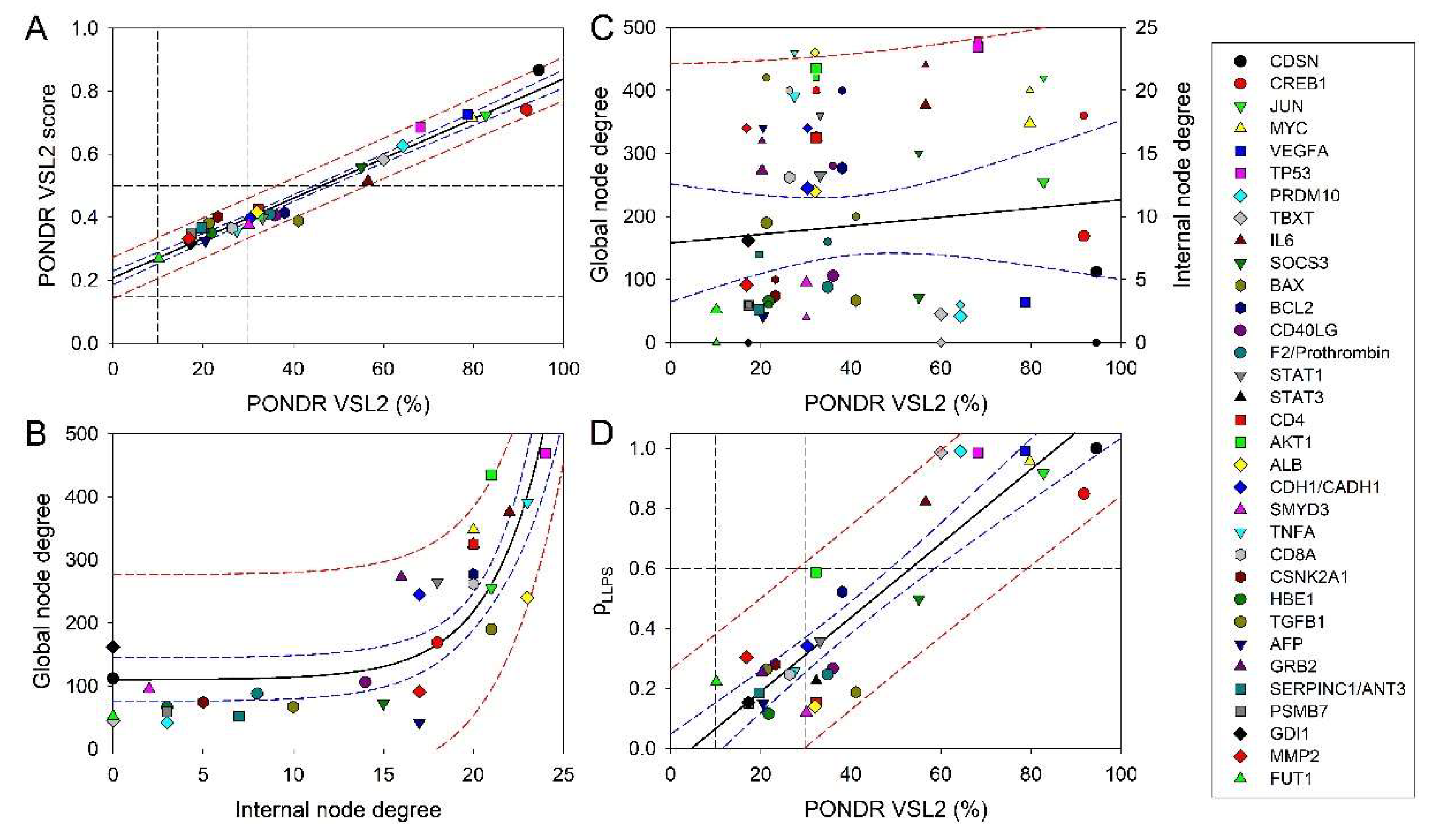

3.2. Intrinsic Disorder Status of Host Proteins Interacting with Hepatotropic Viruses

3.3. Intrinsic Disorder Status of Host Proteins Shared by Different Hepatotropic Viruses

3.4. Functional Intrinsic Disorder in Most Shared Host Proteins

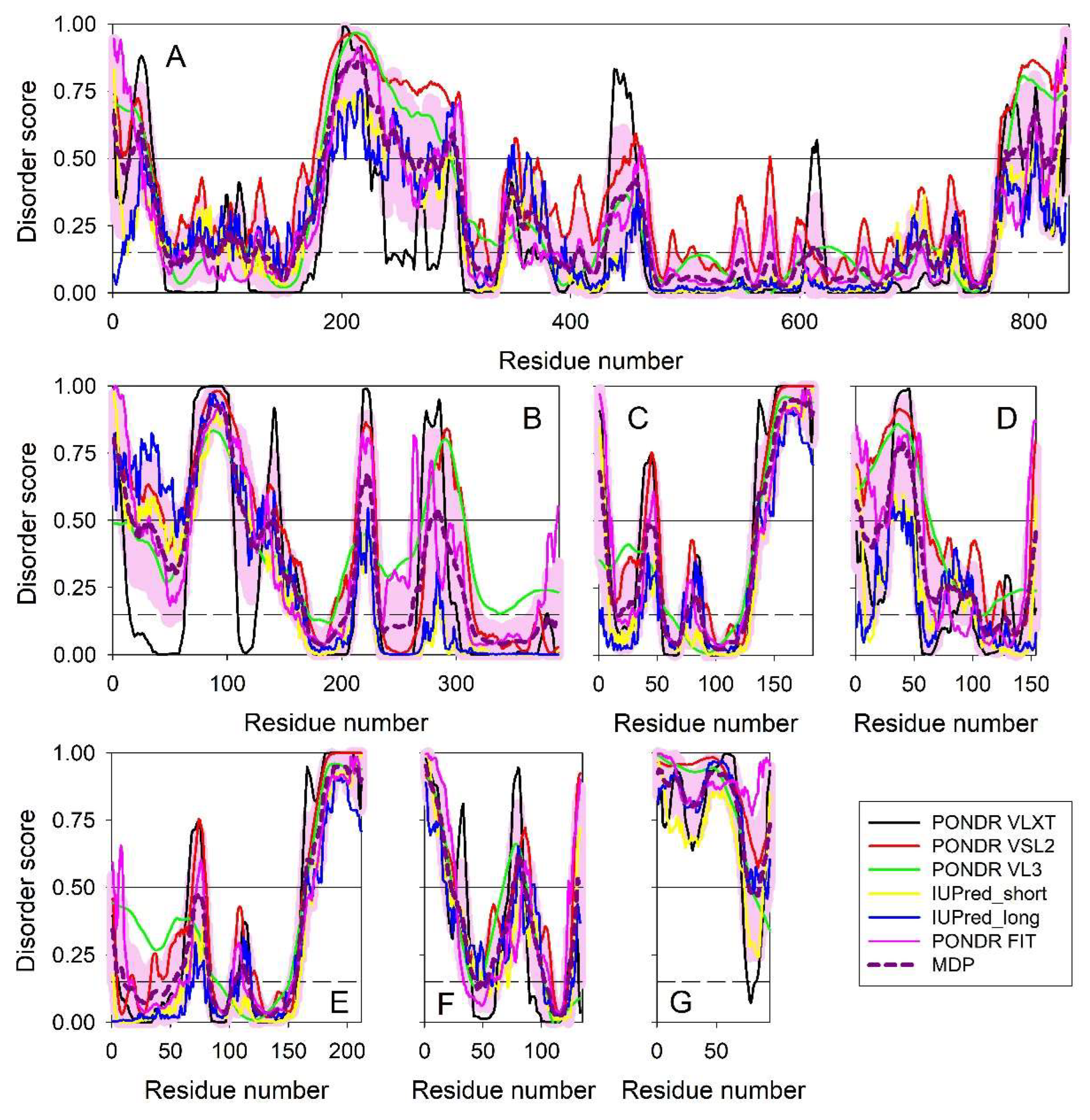

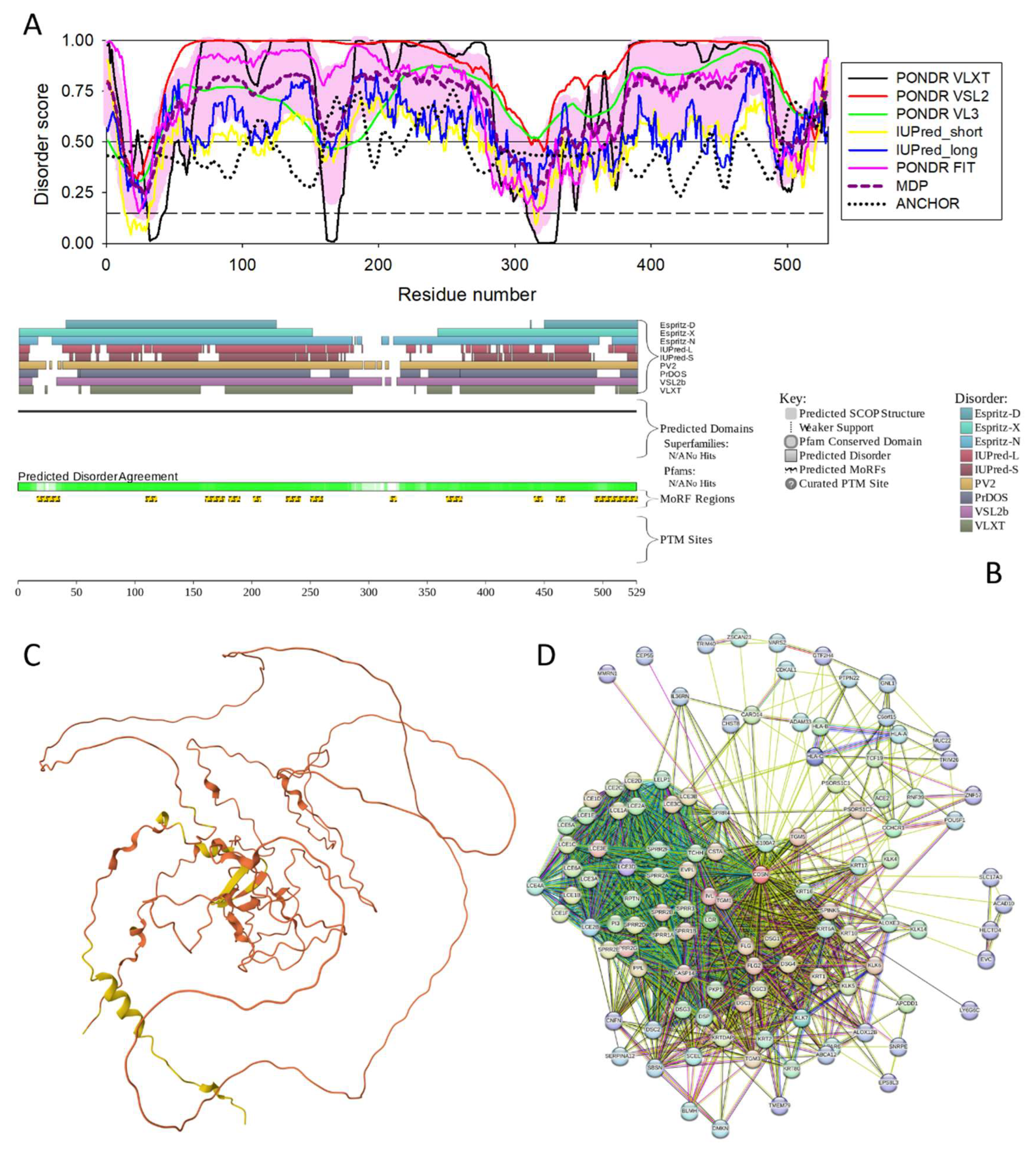

3.4.1. Corneodesmosin (CDSN, UniProt ID: Q15517; PPIDR: 94.52%) Shared by HAV, HBV, HCV, and HDV

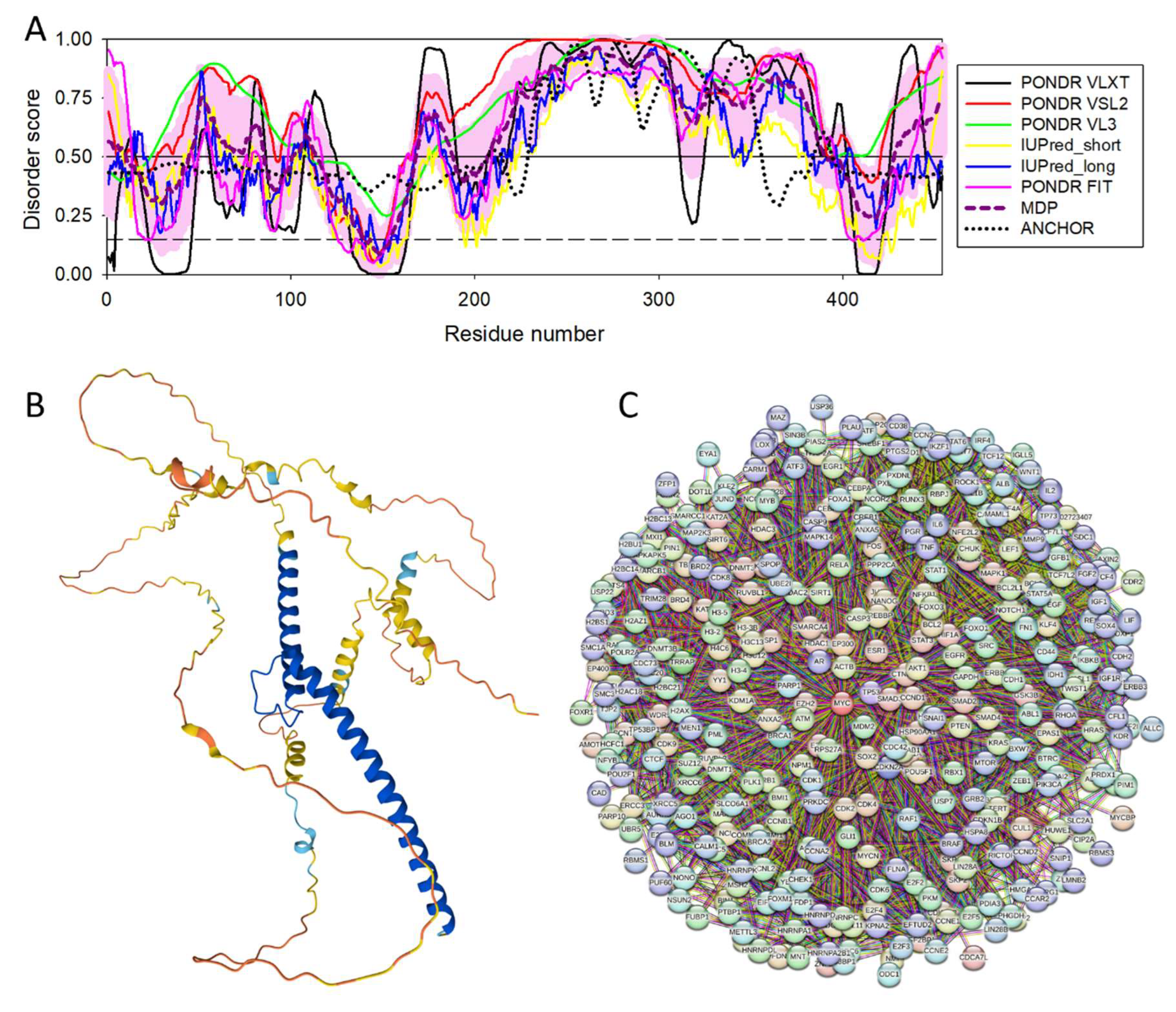

3.4.2. Myc Proto-Oncogene Protein (MYC, UniProt ID: P01106; PPIDR: 79.74%) Shared by HAV (H2QWQ2), HBV and HCV

3.4.3. Cellular Tumor Antigen p53 (TP53, UniProt ID: P04637; PPIDR: 68.11%) Shared by HAV, HBV and HCV

3.4.4. PR Domain Zinc Finger Protein 10 (PRDM10, UniProt ID: Q9NQV6; PPIDR: 64.34%) Shared by HAV, HBV and HCV

3.4.5. T-Box Transcription Factor T (TBXT, UniProt ID: O15178; PPIDR: 60.00%) Shared by HAV, HBV, HCV, and HDV

3.4.6. Human Serum Albumin (ALB; UniProt ID: P02768; PPIDR: 32.02%) Shared by HAV, HBV and HCV

3.4.7. T-Cell Surface Glycoprotein CD8 Alpha Chain (CD8A; UniProt ID: P01732; PPIDR: 26.38%) Shared by HAV, HBV and HCV

3.4.8. α-Fetoprotein (AFP; UniProt ID: P02771; PPIDR: 20.53%) Shared by HAV, HBV and HCV

3.4.9. Proteasome Subunit Beta Type-7 (PSMB7; UniProt ID: Q99436; PPIDR: 17.33%) Shared by HAV, HBV and HCV

3.4.10. RAB GDP Dissociation Inhibitor Alpha (GDI1; UniProt ID: P31150; PPIDR: 17.23%) Shared by HAV, HBV, HCV, and HDV

3.4.11. Galactoside Alpha-(1,2)-Fucosyltransferase 1 (FUT1; UniProt ID: P19526; PPIDR: 10.14%) Shared by HAV, HBV, HCV, and HDV

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, G.; Jing, W.; Liu, J.; Liu, M. The global trends and regional differences in incidence and mortality of hepatitis A from 1990 to 2019 and implications for its prevention. Hepatol Int 2021, 15, 1068-1082. [CrossRef]

- Linder, K.A.; Malani, P.N. Hepatitis A. JAMA 2017, 318, 2393. [CrossRef]

- Gish, R.G. Current treatment and future directions in the management of chronic hepatitis B viral infection. Clin Liver Dis 2005, 9, 541-565, v. [CrossRef]

- Akbar, F.; Yoshida, O.; Abe, M.; Hiasa, Y.; Onji, M. Engineering immune therapy against hepatitis B virus. Hepatol Res 2007, 37 Suppl 3, S351-356. [CrossRef]

- Global Burden Of Hepatitis, C.W.G. Global burden of disease (GBD) for hepatitis C. J Clin Pharmacol 2004, 44, 20-29. [CrossRef]

- Shepard, C.W.; Finelli, L.; Fiore, A.E.; Bell, B.P. Epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis B virus infection in United States children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005, 24, 755-760. [CrossRef]

- Frank, C.; Mohamed, M.K.; Strickland, G.T.; Lavanchy, D.; Arthur, R.R.; Magder, L.S.; El Khoby, T.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.; Aly Ohn, E.S.; Anwar, W.; et al. The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Lancet 2000, 355, 887-891. [CrossRef]

- Alter, M.J. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol 2007, 13, 2436-2441. [CrossRef]

- Heidrich, B.; Manns, M.P.; Wedemeyer, H. Treatment options for hepatitis delta virus infection. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2013, 15, 31-38. [CrossRef]

- Reinheimer, C.; Doerr, H.W.; Berger, A. Hepatitis delta: on soft paws across Germany. Infection 2012, 40, 621-625. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, C.; Tavanez, J.P.; Gudima, S. Hepatitis delta virus: A fascinating and neglected pathogen. World J Virol 2015, 4, 313-322. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Su, J.; Ma, Z.; Bramer, W.M.; Cao, W.; de Man, R.A.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; Pan, Q. The global epidemiology of hepatitis E virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Liver Int 2020, 40, 1516-1528. [CrossRef]

- Migueres, M.; Lhomme, S.; Izopet, J. Hepatitis A: Epidemiology, High-Risk Groups, Prevention and Research on Antiviral Treatment. Viruses 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Villena, E.Z. Module lTransmission routes of hepatitis C virus infection. Annals of Hepatology 2006, 5, 12-14. [CrossRef]

- Seeger, C.; Mason, W.S. Molecular biology of hepatitis B virus infection. Virology 2015, 479-480, 672-686. [CrossRef]

- Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep 1998, 47, 1-39.

- Rizzetto, M.; Hoyer, B.; Canese, M.G.; Shih, J.W.; Purcell, R.H.; Gerin, J.L. delta Agent: association of delta antigen with hepatitis B surface antigen and RNA in serum of delta-infected chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1980, 77, 6124-6128. [CrossRef]

- Ponzetto, A.; Negro, F.; Popper, H.; Bonino, F.; Engle, R.; Rizzetto, M.; Purcell, R.H.; Gerin, J.L. Serial passage of hepatitis delta virus in chronic hepatitis B virus carrier chimpanzees. Hepatology 1988, 8, 1655-1661. [CrossRef]

- Niro, G.A.; Casey, J.L.; Gravinese, E.; Garrubba, M.; Conoscitore, P.; Sagnelli, E.; Durazzo, M.; Caporaso, N.; Perri, F.; Leandro, G.; et al. Intrafamilial transmission of hepatitis delta virus: molecular evidence. J Hepatol 1999, 30, 564-569. [CrossRef]

- Rizzetto, M.; Verme, G.; Recchia, S.; Bonino, F.; Farci, P.; Arico, S.; Calzia, R.; Picciotto, A.; Colombo, M.; Popper, H. Chronic hepatitis in carriers of hepatitis B surface antigen, with intrahepatic expression of the delta antigen. An active and progressive disease unresponsive to immunosuppressive treatment. Ann Intern Med 1983, 98, 437-441. [CrossRef]

- Fattovich, G.; Giustina, G.; Christensen, E.; Pantalena, M.; Zagni, I.; Realdi, G.; Schalm, S.W. Influence of hepatitis delta virus infection on morbidity and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type B. The European Concerted Action on Viral Hepatitis (Eurohep). Gut 2000, 46, 420-426. [CrossRef]

- Khuroo, M.S.; Kamili, S. Aetiology, clinical course and outcome of sporadic acute viral hepatitis in pregnancy. J Viral Hepat 2003, 10, 61-69. [CrossRef]

- Koff, R.S. Risks associated with hepatitis A and hepatitis B in patients with hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001, 33, 20-26. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, J.R.; Hachem, C.Y.; Kanwal, F.; Mei, M.; El-Serag, H.B. Meeting vaccination quality measures for hepatitis A and B virus in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Hepatology 2011, 53, 42-52. [CrossRef]

- Syed, N.A.; Hearing, S.D.; Shaw, I.S.; Probert, C.S.; Brooklyn, T.N.; Caul, E.O.; Barry, R.E.; Sarangi, J. Outbreak of hepatitis A in the injecting drug user and homeless populations in Bristol: control by a targeted vaccination programme and possible parenteral transmission. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003, 15, 901-906. [CrossRef]

- Vento, S. Fulminant hepatitis associated with hepatitis A virus superinfection in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat 2000, 7 Suppl 1, 7-8. [CrossRef]

- Mavilia, M.G.; Wu, G.Y. HBV-HCV Coinfection: Viral Interactions, Management, and Viral Reactivation. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2018, 6, 296-305. [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, Q.; Sumrin, A.; Iqbal, M.; Younas, S.; Hussain, N.; Mahnoor, M.; Wajid, A. Hepatitis C virus/Hepatitis B virus coinfection: Current prospectives. Antivir Ther 2023, 28, 13596535231189643. [CrossRef]

- Weakley, T.; Rajender Reddy, K. Hepatitis B. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 1999, 2, 463-472. [CrossRef]

- Weltman, M.D.; Brotodihardjo, A.; Crewe, E.B.; Farrell, G.C.; Bilous, M.; Grierson, J.M.; Liddle, C. Coinfection with hepatitis B and C or B, C and delta viruses results in severe chronic liver disease and responds poorly to interferon-alpha treatment. J Viral Hepat 1995, 2, 39-45. [CrossRef]

- Jardi, R.; Rodriguez, F.; Buti, M.; Costa, X.; Cotrina, M.; Galimany, R.; Esteban, R.; Guardia, J. Role of hepatitis B, C, and D viruses in dual and triple infection: influence of viral genotypes and hepatitis B precore and basal core promoter mutations on viral replicative interference. Hepatology 2001, 34, 404-410. [CrossRef]

- Bumbea, H.; Vladareanu, A.M.; Vintilescu, A.; Radesi, S.; Ciufu, C.; Onisai, M.; Baluta, C.; Begu, M.; Dobrea, C.; Arama, V.; et al. The lymphocyte immunophenotypical pattern in chronic lymphocytic leukemia associated with hepatitis viral infections. J Med Life 2011, 4, 256-263.

- Gozlan, J.; Lacombe, K.; Gault, E.; Raguin, G.; Girard, P.M. Complete cure of HBV-HDV co-infection after 24weeks of combination therapy with pegylated interferon and ribavirin in a patient co-infected with HBV/HCV/HDV/HIV. J Hepatol 2009, 50, 432-434. [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, J.; Wedemeyer, H. Hepatitis delta: immunopathogenesis and clinical challenges. Dig Dis 2010, 28, 133-138. [CrossRef]

- Lacombe, K.; Boyd, A.; Desvarieux, M.; Serfaty, L.; Bonnord, P.; Gozlan, J.; Molina, J.M.; Miailhes, P.; Lascoux-Combe, C.; Gault, E.; et al. Impact of chronic hepatitis C and/or D on liver fibrosis severity in patients co-infected with HIV and hepatitis B virus. AIDS 2007, 21, 2546-2549. [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, B.; Sikorska, K.; Stalke, P.; Bielawski, K.; Zietkowski, D. Hepatitis D, B and C virus (HDV/HBV/HCV) coinfection as a diagnostic problem and therapeutic challenge. Clin Exp Hepatol 2017, 3, 23-27. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, N.B.; Poles, M.A. Hepatitis B virus infection: co-infection with hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus, and human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Liver Dis 2004, 8, 445-460, viii. [CrossRef]

- Burkard, T.; Proske, N.; Resner, K.; Collignon, L.; Knegendorf, L.; Friesland, M.; Verhoye, L.; Sayed, I.M.; Bruggemann, Y.; Nocke, M.K.; et al. Viral Interference of Hepatitis C and E Virus Replication in Novel Experimental Co-Infection Systems. Cells 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Elhendawy, M.; Abo-Ali, L.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; Hagras, M.M.; Kabbash, I.; Mansour, L.; Atia, S.; Esmat, G.; Abo-ElAzm, A.R.; El-Kalla, F.; et al. HCV and HEV: two players in an Egyptian village, a study of prevalence, incidence, and co-infection. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2020, 27, 33659-33667. [CrossRef]

- Oluremi, A.S.; Ajadi, T.A.; Opaleye, O.O.; Alli, O.A.T.; Ogbolu, D.O.; Enitan, S.S.; Alaka, O.O.; Adelakun, A.A.; Adediji, I.O.; Ogunleke, A.O.; et al. High seroprevalence of viral hepatitis among animal handlers in Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria. J Immunoassay Immunochem 2021, 42, 34-47. [CrossRef]

- Salu, O.B.; Akinbamiro, T.F.; Orenolu, R.M.; Ishaya, O.D.; Anyanwu, R.A.; Vitowanu, O.R.; Abdullah, M.A.; Olowoyeye, A.H.; Tijani, S.O.; Oyedeji, K.S.; et al. Detection of hepatitis viruses in suspected cases of Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers in Nigeria. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0305521. [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N.; Roman, A.; Oldfield, C.J.; Dunker, A.K. Protein intrinsic disorder and human papillomaviruses: increased amount of disorder in E6 and E7 oncoproteins from high risk HPVs. J Proteome Res 2006, 5, 1829-1842. [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Xue, B.; Dolan, P.T.; LaCount, D.J.; Kurgan, L.; Uversky, V.N. The intrinsic disorder status of the human hepatitis C virus proteome. Mol Biosyst 2014, 10, 1345-1363. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Yan, J.; Fan, X.; Mizianty, M.J.; Xue, B.; Wang, K.; Hu, G.; Uversky, V.N.; Kurgan, L. Exceptionally abundant exceptions: comprehensive characterization of intrinsic disorder in all domains of life. Cell Mol Life Sci 2015, 72, 137-151. [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Blocquel, D.; Habchi, J.; Uversky, A.V.; Kurgan, L.; Uversky, V.N.; Longhi, S. Structural disorder in viral proteins. Chem Rev 2014, 114, 6880-6911. [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Dunker, A.K.; Uversky, V.N. Orderly order in protein intrinsic disorder distribution: disorder in 3500 proteomes from viruses and the three domains of life. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2012, 30, 137-149. [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Mizianty, M.J.; Kurgan, L.; Uversky, V.N. Protein intrinsic disorder as a flexible armor and a weapon of HIV-1. Cell Mol Life Sci 2012, 69, 1211-1259. [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Williams, R.W.; Oldfield, C.J.; Goh, G.K.; Dunker, A.K.; Uversky, V.N. Viral disorder or disordered viruses: do viral proteins possess unique features? Protein Pept Lett 2010, 17, 932-951. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.M.; Verma, N.C.; Rao, C.; Uversky, V.N.; Nandi, C.K. Intrinsically disordered proteins of viruses: Involvement in the mechanism of cell regulation and pathogenesis. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2020, 174, 1-78. [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P.T.; Roth, A.P.; Xue, B.; Sun, R.; Dunker, A.K.; Uversky, V.N.; LaCount, D.J. Intrinsic disorder mediates hepatitis C virus core-host cell protein interactions. Protein Sci 2015, 24, 221-235. [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Ganti, K.; Rabionet, A.; Banks, L.; Uversky, V.N. Disordered interactome of human papillomavirus. Curr Pharm Des 2014, 20, 1274-1292. [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Uversky, V.N. Intrinsic disorder in proteins involved in the innate antiviral immunity: another flexible side of a molecular arms race. J Mol Biol 2014, 426, 1322-1350. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhou, W.; Li, D.; Pan, T.; Guo, J.; Zou, H.; Tian, Z.; Li, K.; Xu, J.; Li, X.; et al. Comprehensive characterization of human-virus protein-protein interactions reveals disease comorbidities and potential antiviral drugs. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2022, 20, 1244-1253. [CrossRef]

- Chabrolles, H.; Auclair, H.; Vegna, S.; Lahlali, T.; Pons, C.; Michelet, M.; Coute, Y.; Belmudes, L.; Chadeuf, G.; Kim, Y.; et al. Hepatitis B virus Core protein nuclear interactome identifies SRSF10 as a host RNA-binding protein restricting HBV RNA production. PLoS Pathog 2020, 16, e1008593. [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.; Samanta, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Barik, S.; Biswas, A. The HBV web: An insight into molecular interactomes between the hepatitis B virus and its host en route to hepatocellular carcinoma. J Med Virol 2023, 95, e28436. [CrossRef]

- Nakai, Y.; Miyakawa, K.; Yamaoka, Y.; Hatayama, Y.; Nishi, M.; Suzuki, H.; Kimura, H.; Takahashi, H.; Kimura, Y.; Ryo, A. Generation and Utilization of a Monoclonal Antibody against Hepatitis B Virus Core Protein for a Comprehensive Interactome Analysis. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, E.; Vanhove, J.; Severyn, B.; Verschueren, L.; Pauwels, F. The Hepatitis B Virus Interactome: A Comprehensive Overview. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 724877. [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, I.T.; Romero, S.; Kissi-Twum, A.; Knoener, R.; Scalf, M.; Sherer, N.M.; Smith, L.M. Identification of Host Proteins Involved in Hepatitis B Virus Genome Packaging. J Proteome Res 2024, 23, 4128-4138. [CrossRef]

- Budzko, L.; Marcinkowska-Swojak, M.; Jackowiak, P.; Kozlowski, P.; Figlerowicz, M. Copy number variation of genes involved in the hepatitis C virus-human interactome. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 31340. [CrossRef]

- Colpitts, C.C.; El-Saghire, H.; Pochet, N.; Schuster, C.; Baumert, T.F. High-throughput approaches to unravel hepatitis C virus-host interactions. Virus Res 2016, 218, 18-24. [CrossRef]

- de Chassey, B.; Navratil, V.; Tafforeau, L.; Hiet, M.S.; Aublin-Gex, A.; Agaugue, S.; Meiffren, G.; Pradezynski, F.; Faria, B.F.; Chantier, T.; et al. Hepatitis C virus infection protein network. Mol Syst Biol 2008, 4, 230. [CrossRef]

- Dolan, P.T.; Zhang, C.; Khadka, S.; Arumugaswami, V.; Vangeloff, A.D.; Heaton, N.S.; Sahasrabudhe, S.; Randall, G.; Sun, R.; LaCount, D.J. Identification and comparative analysis of hepatitis C virus-host cell protein interactions. Mol Biosyst 2013, 9, 3199-3209. [CrossRef]

- Germain, M.A.; Chatel-Chaix, L.; Gagne, B.; Bonneil, E.; Thibault, P.; Pradezynski, F.; de Chassey, B.; Meyniel-Schicklin, L.; Lotteau, V.; Baril, M.; et al. Elucidating novel hepatitis C virus-host interactions using combined mass spectrometry and functional genomics approaches. Mol Cell Proteomics 2014, 13, 184-203. [CrossRef]

- Matthaei, A.; Joecks, S.; Frauenstein, A.; Bruening, J.; Bankwitz, D.; Friesland, M.; Gerold, G.; Vieyres, G.; Kaderali, L.; Meissner, F.; et al. Landscape of protein-protein interactions during hepatitis C virus assembly and release. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12, e0256222. [CrossRef]

- Mosca, E.; Alfieri, R.; Milanesi, L. Diffusion of information throughout the host interactome reveals gene expression variations in network proximity to target proteins of hepatitis C virus. PLoS One 2014, 9, e113660. [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, A.; Maulik, U. Network-based study reveals potential infection pathways of hepatitis-C leading to various diseases. PLoS One 2014, 9, e94029. [CrossRef]

- Saik, O.V.; Ivanisenko, T.V.; Demenkov, P.S.; Ivanisenko, V.A. Interactome of the hepatitis C virus: Literature mining with ANDSystem. Virus Res 2016, 218, 40-48. [CrossRef]

- Martino, C.; Di Luca, A.; Bennato, F.; Ianni, A.; Passamonti, F.; Rampacci, E.; Henry, M.; Meleady, P.; Martino, G. Label-Free Quantitative Analysis of Pig Liver Proteome after Hepatitis E Virus Infection. Viruses 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Ojha, N.K.; Lole, K.S. Hepatitis E virus ORF1 encoded non structural protein-host protein interaction network. Virus Res 2016, 213, 195-204. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Huang, W.; Yang, J.; Wen, Z.; Geng, Y.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Systematic identification of hepatitis E virus ORF2 interactome reveals that TMEM134 engages in ORF2-mediated NF-kappaB pathway. Virus Res 2017, 228, 102-108. [CrossRef]

- Cristina, J.; Costa-Mattioli, M. Genetic variability and molecular evolution of hepatitis A virus. Virus Res 2007, 127, 151-157. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ren, J.; Gao, Q.; Hu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Rowlands, D.J.; Yin, W.; Wang, J.; Stuart, D.I.; et al. Hepatitis A virus and the origins of picornaviruses. Nature 2015, 517, 85-88. [CrossRef]

- Probst, C.; Jecht, M.; Gauss-Muller, V. Intrinsic signals for the assembly of hepatitis A virus particles. Role of structural proteins VP4 and 2A. J Biol Chem 1999, 274, 4527-4531. [CrossRef]

- Jecht, M.; Probst, C.; Gauss-Muller, V. Membrane permeability induced by hepatitis A virus proteins 2B and 2BC and proteolytic processing of HAV 2BC. Virology 1998, 252, 218-227. [CrossRef]

- Teterina, N.L.; Bienz, K.; Egger, D.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Ehrenfeld, E. Induction of intracellular membrane rearrangements by HAV proteins 2C and 2BC. Virology 1997, 237, 66-77. [CrossRef]

- Kusov, Y.Y.; Probst, C.; Jecht, M.; Jost, P.D.; Gauss-Muller, V. Membrane association and RNA binding of recombinant hepatitis A virus protein 2C. Arch Virol 1998, 143, 931-944. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Qu, L.; Chen, Z.; Yi, M.; Li, K.; Lemon, S.M. Disruption of innate immunity due to mitochondrial targeting of a picornaviral protease precursor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 7253-7258. [CrossRef]

- Kusov, Y.; Gauss-Muller, V. Improving proteolytic cleavage at the 3A/3B site of the hepatitis A virus polyprotein impairs processing and particle formation, and the impairment can be complemented in trans by 3AB and 3ABC. J Virol 1999, 73, 9867-9878. [CrossRef]

- Beneduce, F.; Ciervo, A.; Kusov, Y.; Gauss-Muller, V.; Morace, G. Mapping of protein domains of hepatitis A virus 3AB essential for interaction with 3CD and viral RNA. Virology 1999, 264, 410-421. [CrossRef]

- Ciervo, A.; Beneduce, F.; Morace, G. Polypeptide 3AB of hepatitis A virus is a transmembrane protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1998, 249, 266-274. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Guo, Y.; Lou, Z. Formation and working mechanism of the picornavirus VPg uridylylation complex. Curr Opin Virol 2014, 9, 24-30. [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.Y.; Ehrenfeld, E.; Summers, D.F. Proteolytic activity of hepatitis A virus 3C protein. J Virol 1991, 65, 2595-2600. [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, K.; Mooney, S.M.; Parekh, N.; Getzenberg, R.H.; Kulkarni, P. A majority of the cancer/testis antigens are intrinsically disordered proteins. J Cell Biochem 2011, 112, 3256-3267. [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N. Analyzing IDPs in interactomes. In Intrinsically Disordered Proteins, Kragelund, B.B., Skriver, K., Eds.; Humana New York, NY, 2020; Volume Methods in Molecular Biology, pp. 895-945.

- Lanford, R.E.; Walker, C.M.; Lemon, S.M. The Chimpanzee Model of Viral Hepatitis: Advances in Understanding the Immune Response and Treatment of Viral Hepatitis. ILAR J 2017, 58, 172-189. [CrossRef]

- Luke, S.; Verma, R.S. Human (Homo sapiens) and chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) share similar ancestral centromeric alpha satellite DNA sequences but other fractions of heterochromatin differ considerably. Am J Phys Anthropol 1995, 96, 63-71. [CrossRef]

- Brocca, S.; Grandori, R.; Longhi, S.; Uversky, V. Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation by Intrinsically Disordered Protein Regions of Viruses: Roles in Viral Life Cycle and Control of Virus-Host Interactions. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Brodrick, A.J.; Broadbent, A.J. The Formation and Function of Birnaviridae Virus Factories. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, T.; Lu, P.; Chen, K. Liquid-liquid phase separation in viral infection: From the occurrence and function to treatment potentials. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2025, 246, 114385. [CrossRef]

- Caragliano, E.; Brune, W.; Bosse, J.B. Herpesvirus Replication Compartments: Dynamic Biomolecular Condensates? Viruses 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Chau, B.A.; Chen, V.; Cochrane, A.W.; Parent, L.J.; Mouland, A.J. Liquid-liquid phase separation of nucleocapsid proteins during SARS-CoV-2 and HIV-1 replication. Cell Rep 2023, 42, 111968. [CrossRef]

- Di Nunzio, F.; Uversky, V.N.; Mouland, A.J. Biomolecular condensates: insights into early and late steps of the HIV-1 replication cycle. Retrovirology 2023, 20, 4. [CrossRef]

- Dolnik, O.; Gerresheim, G.K.; Biedenkopf, N. New Perspectives on the Biogenesis of Viral Inclusion Bodies in Negative-Sense RNA Virus Infections. Cells 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Eltayeb, A.; Al-Sarraj, F.; Alharbi, M.; Albiheyri, R.; Mattar, E.H.; Abu Zeid, I.M.; Bouback, T.A.; Bamagoos, A.; Uversky, V.N.; Rubio-Casillas, A.; et al. Intrinsic factors behind long COVID: IV. Hypothetical roles of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein and its liquid-liquid phase separation. J Cell Biochem 2024, 125, e30530. [CrossRef]

- Etibor, T.A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Amorim, M.J. Liquid Biomolecular Condensates and Viral Lifecycles: Review and Perspectives. Viruses 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Glon, D.; Leonardon, B.; Guillemot, A.; Albertini, A.; Lagaudriere-Gesbert, C.; Gaudin, Y. Biomolecular condensates with liquid properties formed during viral infections. Microbes Infect 2024, 26, 105402. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ernst, C.; Kolonko-Adamska, M.; Greb-Markiewicz, B.; Man, J.; Parissi, V.; Ng, B.W. Phase separation in viral infections. Trends Microbiol 2022, 30, 1217-1231. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, N.; Camporeale, G.; Salgueiro, M.; Borkosky, S.S.; Visentin, A.; Peralta-Martinez, R.; Loureiro, M.E.; de Prat-Gay, G. Deconstructing virus condensation. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17, e1009926. [CrossRef]

- Mouland, A.J.; Chau, B.A.; Uversky, V.N. Methodological approaches to studying phase separation and HIV-1 replication: Current and future perspectives. Methods 2024, 229, 147-155. [CrossRef]

- Nevers, Q.; Albertini, A.A.; Lagaudriere-Gesbert, C.; Gaudin, Y. Negri bodies and other virus membrane-less replication compartments. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2020, 1867, 118831. [CrossRef]

- Papa, G.; Borodavka, A.; Desselberger, U. Viroplasms: Assembly and Functions of Rotavirus Replication Factories. Viruses 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.; Shofa, M.; Ode, H.; Yumiya, M.; Hirano, J.; Okamoto, T.; Yoshimura, S.H. How Do Flaviviruses Hijack Host Cell Functions by Phase Separation? Viruses 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Scoca, V.; Di Nunzio, F. Membraneless organelles restructured and built by pandemic viruses: HIV-1 and SARS-CoV-2. J Mol Cell Biol 2021, 13, 259-268. [CrossRef]

- Su, J.M.; Wilson, M.Z.; Samuel, C.E.; Ma, D. Formation and Function of Liquid-Like Viral Factories in Negative-Sense Single-Stranded RNA Virus Infections. Viruses 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Bai, L.; Yan, B.; Meng, W.; Wang, H.; Zhai, J.; Si, F.; Zheng, C. When liquid-liquid phase separation meets viral infections. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 985622. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ye, H.; Liu, C.; Zhou, H.; He, M.; Liang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, K.; Qin, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. PABP-driven secondary condensed phase within RSV inclusion bodies activates viral mRNAs for ribosomal recruitment. Virol Sin 2024, 39, 235-250. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zheng, R.; Li, Z.; Ma, J. Liquid-liquid Phase Separation in Viral Function. J Mol Biol 2023, 435, 167955. [CrossRef]

- Giraud, G.; Roda, M.; Huchon, P.; Michelet, M.; Maadadi, S.; Jutzi, D.; Montserret, R.; Ruepp, M.D.; Parent, R.; Combet, C.; et al. G-quadruplexes control hepatitis B virus replication by promoting cccDNA transcription and phase separation in hepatocytes. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, 2290-2305. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhai, Z.; Liu, C.; Yang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zeng, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Nie, X.; et al. Upregulated PrP(C) by HBx enhances NF-kappaB signal via liquid-liquid phase separation to advance liver cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol 2024, 8, 211. [CrossRef]

- Hundie, G.B.; Stalin Raj, V.; Gebre Michael, D.; Pas, S.D.; Koopmans, M.P.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Smits, S.L.; Haagmans, B.L. A novel hepatitis B virus subgenotype D10 circulating in Ethiopia. J Viral Hepat 2017, 24, 163-173. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Xie, X.; Tan, X.; Yu, H.; Tian, M.; Lv, H.; Qin, C.; Qi, J.; Zhu, Q. The Functions of Hepatitis B Virus Encoding Proteins: Viral Persistence and Liver Pathogenesis. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 691766. [CrossRef]

- Leupin, O.; Bontron, S.; Schaeffer, C.; Strubin, M. Hepatitis B virus X protein stimulates viral genome replication via a DDB1-dependent pathway distinct from that leading to cell death. J Virol 2005, 79, 4238-4245. [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Pan, T.; Wu, X.; Song, W.; Wang, S.; Xu, Y.; Rice, C.M.; Macdonald, M.R.; Yuan, Z. Hepatitis C virus co-opts Ras-GTPase-activating protein-binding protein 1 for its genome replication. J Virol 2011, 85, 6996-7004. [CrossRef]

- Wolk, B.; Buchele, B.; Moradpour, D.; Rice, C.M. A dynamic view of hepatitis C virus replication complexes. J Virol 2008, 82, 10519-10531. [CrossRef]

- Nesterov, S.V.; Ilyinsky, N.S.; Uversky, V.N. Liquid-liquid phase separation as a common organizing principle of intracellular space and biomembranes providing dynamic adaptive responses. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 2021, 1868, 119102. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Holehouse, A.S.; Leung, D.W.; Amarasinghe, G.K.; Dutch, R.E. Liquid Phase Partitioning in Virus Replication: Observations and Opportunities. Annu Rev Virol 2022, 9, 285-306. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ndongwe, T.P.; Puray-Chavez, M.; Casey, M.C.; Izumi, T.; Pathak, V.K.; Tedbury, P.R.; Sarafianos, S.G. Effect of P-body component Mov10 on HCV virus production and infectivity. FASEB J 2020, 34, 9433-9449. [CrossRef]

- Mello, F.C.A.; Barros, T.M.; Angelice, G.P.; Costa, V.D.; Mello, V.M.; Pardini, M.; Lampe, E.; Lago, B.V.; Villar, L.M. Circulation of HDV Genotypes in Brazil: Identification of a Putative Novel HDV-8 Subgenotype. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11, e0396522. [CrossRef]

- Sunbul, M. Hepatitis B virus genotypes: global distribution and clinical importance. World J Gastroenterol 2014, 20, 5427-5434. [CrossRef]

- Weiner, A.J.; Choo, Q.L.; Wang, K.S.; Govindarajan, S.; Redeker, A.G.; Gerin, J.L.; Houghton, M. A single antigenomic open reading frame of the hepatitis delta virus encodes the epitope(s) of both hepatitis delta antigen polypeptides p24 delta and p27 delta. J Virol 1988, 62, 594-599. [CrossRef]

- Chao, M.; Hsieh, S.Y.; Taylor, J. Role of two forms of hepatitis delta virus antigen: evidence for a mechanism of self-limiting genome replication. J Virol 1990, 64, 5066-5069. [CrossRef]

- Glenn, J.S.; White, J.M. trans-dominant inhibition of human hepatitis delta virus genome replication. J Virol 1991, 65, 2357-2361. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.H.; Yung, B.Y.; Syu, W.J.; Lee, Y.H. The nucleolar phosphoprotein B23 interacts with hepatitis delta antigens and modulates the hepatitis delta virus RNA replication. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 25166-25175. [CrossRef]

- Polson, A.G.; Bass, B.L.; Casey, J.L. RNA editing of hepatitis delta virus antigenome by dsRNA-adenosine deaminase. Nature 1996, 380, 454-456. [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.K.; Lazinski, D.W. Replicating hepatitis delta virus RNA is edited in the nucleus by the small form of ADAR1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 15118-15123. [CrossRef]

- Glenn, J.S.; Watson, J.A.; Havel, C.M.; White, J.M. Identification of a prenylation site in delta virus large antigen. Science 1992, 256, 1331-1333. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.B.; Lai, M.M. Isoprenylation mediates direct protein-protein interactions between hepatitis large delta antigen and hepatitis B virus surface antigen. J Virol 1993, 67, 7659-7662. [CrossRef]

- Khalfi, P.; Denis, Z.; McKellar, J.; Merolla, G.; Chavey, C.; Ursic-Bedoya, J.; Soppa, L.; Szirovicza, L.; Hetzel, U.; Dufourt, J.; et al. Comparative analysis of human, rodent and snake deltavirus replication. PLoS Pathog 2024, 20, e1012060. [CrossRef]

- Brazda, V.; Valkova, N.; Dobrovolna, M.; Mergny, J.L. Abundance of G-Quadruplex Forming Sequences in the Hepatitis Delta Virus Genomes. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 4096-4101. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Purcell, R.H.; Emerson, S.U. Identification of the 5’ terminal sequence of the SAR-55 and MEX-14 strains of hepatitis E virus and confirmation that the genome is capped. J Med Virol 2001, 65, 293-295. [CrossRef]

- Kenney, S.P.; Meng, X.J. Hepatitis E Virus Genome Structure and Replication Strategy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2019, 9. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.B.; Simmonds, P.; Members Of The International Committee On The Taxonomy Of Viruses Study, G.; Jameel, S.; Emerson, S.U.; Harrison, T.J.; Meng, X.J.; Okamoto, H.; Van der Poel, W.H.M.; Purdy, M.A. Consensus proposals for classification of the family Hepeviridae. J Gen Virol 2014, 95, 2223-2232. [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.H.; Tan, B.H.; Teo, E.C.; Lim, S.G.; Dan, Y.Y.; Wee, A.; Aw, P.P.; Zhu, Y.; Hibberd, M.L.; Tan, C.K.; et al. Chronic Infection With Camelid Hepatitis E Virus in a Liver Transplant Recipient Who Regularly Consumes Camel Meat and Milk. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 355-357 e353. [CrossRef]

- Parvez, M.K. Mutational analysis of hepatitis E virus ORF1 “Y-domain”: Effects on RNA replication and virion infectivity. World J Gastroenterol 2017, 23, 590-602. [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Purdy, M.A.; Rozanov, M.N.; Reyes, G.R.; Bradley, D.W. Computer-assisted assignment of functional domains in the nonstructural polyprotein of hepatitis E virus: delineation of an additional group of positive-strand RNA plant and animal viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992, 89, 8259-8263. [CrossRef]

- Purdy, M.A. Evolution of the hepatitis E virus polyproline region: order from disorder. J Virol 2012, 86, 10186-10193. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Heller, B.; Capuccino, J.M.; Song, B.; Nimgaonkar, I.; Hrebikova, G.; Contreras, J.E.; Ploss, A. Hepatitis E virus ORF3 is a functional ion channel required for release of infectious particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 1147-1152. [CrossRef]

- Gouttenoire, J.; Pollan, A.; Abrami, L.; Oechslin, N.; Mauron, J.; Matter, M.; Oppliger, J.; Szkolnicka, D.; Dao Thi, V.L.; van der Goot, F.G.; et al. Palmitoylation mediates membrane association of hepatitis E virus ORF3 protein and is required for infectious particle secretion. PLoS Pathog 2018, 14, e1007471. [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, S.; Takahashi, M.; Jirintai; Tanaka, T.; Yamada, K.; Nishizawa, T.; Okamoto, H. A PSAP motif in the ORF3 protein of hepatitis E virus is necessary for virion release from infected cells. J Gen Virol 2011, 92, 269-278. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Takahashi, M.; Hoshino, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Ichiyama, K.; Nagashima, S.; Tanaka, T.; Okamoto, H. ORF3 protein of hepatitis E virus is essential for virion release from infected cells. J Gen Virol 2009, 90, 1880-1891. [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Yang, C.; Yu, W.; Bi, Y.; Long, F.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Jing, S. Hepatitis E virus infection activates signal regulator protein alpha to down-regulate type I interferon. Immunol Res 2016, 64, 115-122. [CrossRef]

- Rancurel, C.; Khosravi, M.; Dunker, A.K.; Romero, P.R.; Karlin, D. Overlapping genes produce proteins with unusual sequence properties and offer insight into de novo protein creation. J Virol 2009, 83, 10719-10736. [CrossRef]

- Willis, S.; Masel, J. Gene Birth Contributes to Structural Disorder Encoded by Overlapping Genes. Genetics 2018, 210, 303-313. [CrossRef]

- Tokuriki, N.; Oldfield, C.J.; Uversky, V.N.; Berezovsky, I.N.; Tawfik, D.S. Do viral proteins possess unique biophysical features? Trends Biochem Sci 2009, 34, 53-59. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Sullivan, W.J., Jr.; Radivojac, P.; Dunker, A.K.; Uversky, V.N. Intrinsic disorder in pathogenic and non-pathogenic microbes: discovering and analyzing the unfoldomes of early-branching eukaryotes. Mol Biosyst 2008, 4, 328-340. [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Oldfield, C.; Meng, J.; Hsu, W.L.; Xue, B.; Uversky, V.N.; Romero, P.; Dunker, A.K. Subclassifying disordered proteins by the CH-CDF plot method. Pac Symp Biocomput 2012, 128-139.

- Oldfield, C.J.; Cheng, Y.; Cortese, M.S.; Brown, C.J.; Uversky, V.N.; Dunker, A.K. Comparing and combining predictors of mostly disordered proteins. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 1989-2000. [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N.; Gillespie, J.R.; Fink, A.L. Why are “natively unfolded” proteins unstructured under physiologic conditions? Proteins 2000, 41, 415-427. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.S.; Uversky, V.N. Intrinsic Disorder as a Natural Preservative: High Levels of Intrinsic Disorder in Proteins Found in the 2600-Year-Old Human Brain. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal statistical society: series B (Methodological) 1995, 57, 289-300. [CrossRef]

- Hardenberg, M.; Horvath, A.; Ambrus, V.; Fuxreiter, M.; Vendruscolo, M. Widespread occurrence of the droplet state of proteins in the human proteome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 33254-33262. [CrossRef]

- Turoverov, K.K.; Kuznetsova, I.M.; Fonin, A.V.; Darling, A.L.; Zaslavsky, B.Y.; Uversky, V.N. Stochasticity of Biological Soft Matter: Emerging Concepts in Intrinsically Disordered Proteins and Biological Phase Separation. Trends Biochem Sci 2019, 44, 716-728. [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Brangwynne, C.P. Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease. Science 2017, 357. [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N.; Kuznetsova, I.M.; Turoverov, K.K.; Zaslavsky, B. Intrinsically disordered proteins as crucial constituents of cellular aqueous two phase systems and coacervates. FEBS Lett 2015, 589, 15-22. [CrossRef]

- Brangwynne, C.P. Phase transitions and size scaling of membrane-less organelles. The Journal of cell biology 2013, 203, 875-881. [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N. Intrinsically disordered proteins in overcrowded milieu: Membrane-less organelles, phase separation, and intrinsic disorder. Current opinion in structural biology 2016, 44, 18-30. [CrossRef]

- Brangwynne, Clifford P.; Tompa, P.; Pappu, Rohit V. Polymer physics of intracellular phase transitions. Nat Phys 2015, 11, 899-904. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Fu, C.; Yao, R.; Li, H.; Peng, F.; Li, N. Emerging roles of liquid-liquid phase separation in liver innate immunity. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 430. [CrossRef]

- Ishida-Yamamoto, A.; Igawa, S. The biology and regulation of corneodesmosomes. Cell Tissue Res 2015, 360, 477-482. [CrossRef]

- Jonca, N.; Caubet, C.; Guerrin, M.; Simon, M.; Serre, G. Corneodesmosin: structure, function and involvement in pathophysiology. 2010.

- Jonca, N.; Leclerc, E.A.; Caubet, C.; Simon, M.; Guerrin, M.; Serre, G. Corneodesmosomes and corneodesmosin: from the stratum corneum cohesion to the pathophysiology of genodermatoses. Eur J Dermatol 2011, 21 Suppl 2, 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Oji, V.; Eckl, K.M.; Aufenvenne, K.; Natebus, M.; Tarinski, T.; Ackermann, K.; Seller, N.; Metze, D.; Nurnberg, G.; Folster-Holst, R.; et al. Loss of corneodesmosin leads to severe skin barrier defect, pruritus, and atopy: unraveling the peeling skin disease. Am J Hum Genet 2010, 87, 274-281. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Zhou, Y.; Matsuo, S.; Nakanishi, H.; Hirose, K.; Oura, H.; Arase, S.; Ishida-Yamamoto, A.; Bando, Y.; Izumi, K.; et al. Targeted deletion of the murine corneodesmosin gene delineates its essential role in skin and hair physiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 6720-6724. [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, E.A.; Huchenq, A.; Mattiuzzo, N.R.; Metzger, D.; Chambon, P.; Ghyselinck, N.B.; Serre, G.; Jonca, N.; Guerrin, M. Corneodesmosin gene ablation induces lethal skin-barrier disruption and hair-follicle degeneration related to desmosome dysfunction. J Cell Sci 2009, 122, 2699-2709. [CrossRef]

- Noe, M.H.; Grewal, S.K.; Shin, D.B.; Ogdie, A.; Takeshita, J.; Gelfand, J.M. Increased prevalence of HCV and hepatic decompensation in adults with psoriasis: a population-based study in the United Kingdom. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017, 31, 1674-1680. [CrossRef]

- Enomoto, M.; Tateishi, C.; Tsuruta, D.; Tamori, A.; Kawada, N. Remission of Psoriasis After Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection With Direct-Acting Antivirals. Ann Intern Med 2018, 168, 678-680. [CrossRef]

- Sayiner, M.; Golabi, P.; Farhat, F.; Younossi, Z.M. Dermatologic Manifestations of Chronic Hepatitis C Infection. Clin Liver Dis 2017, 21, 555-564. [CrossRef]

- Steinert, P.M.; Mack, J.W.; Korge, B.P.; Gan, S.Q.; Haynes, S.R.; Steven, A.C. Glycine loops in proteins: their occurrence in certain intermediate filament chains, loricrins and single-stranded RNA binding proteins. Int J Biol Macromol 1991, 13, 130-139. [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, M.E.; Castillo, F.; Soucek, L. Structural and Biophysical Insights into the Function of the Intrinsically Disordered Myc Oncoprotein. Cells 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Higgs, M.R.; Lerat, H.; Pawlotsky, J.M. Hepatitis C virus-induced activation of beta-catenin promotes c-Myc expression and a cascade of pro-carcinogenetic events. Oncogene 2013, 32, 4683-4693. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yu, M.; Qu, M.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, D.; Yue, Y.; Guo, S.; Tang, L.; Li, G.; Zheng, W.; et al. Hepatitis B virus-triggered PTEN/beta-catenin/c-Myc signaling enhances PD-L1 expression to promote immune evasion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2020, 318, G162-G173. [CrossRef]

- Tappero, G.; Natoli, G.; Anfossi, G.; Rosina, F.; Negro, F.; Smedile, A.; Bonino, F.; Angeli, A.; Purcell, R.H.; Rizzetto, M.; et al. Expression of the c-myc protooncogene product in cells infected with the hepatitis delta virus. Hepatology 1994, 20, 1109-1114.

- Terradillos, O.; Billet, O.; Renard, C.A.; Levy, R.; Molina, T.; Briand, P.; Buendia, M.A. The hepatitis B virus X gene potentiates c-myc-induced liver oncogenesis in transgenic mice. Oncogene 1997, 14, 395-404. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Miao, X.; Qi, Z.; Zeng, W.; Liang, J.; Liang, Z. Hepatitis B virus X protein upregulates HSP90alpha expression via activation of c-Myc in human hepatocarcinoma cell line, HepG2. Virol J 2010, 7, 45. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.B.; Shao, S.W.; Zhao, L.J.; Luan, J.; Cao, J.; Gao, J.; Zhu, S.Y.; Qi, Z.T. Hepatitis C virus F protein up-regulates c-myc and down-regulates p53 in human hepatoma HepG2 cells. Intervirology 2007, 50, 341-346. [CrossRef]

- Fathy, A.; Abdelrazek, M.A.; Attallah, A.M.; Abouzid, A.; El-Far, M. Hepatitis C virus may accelerate breast cancer progression by increasing mutant p53 and c-Myc oncoproteins circulating levels. Breast Cancer 2024, 31, 116-123. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Peng, Z.; Ding, J.; Ding, K. From cirrhosis to hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-infected patients: genes involved in tumor progression. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2012, 16, 995-1000.

- Bayliss, R.; Burgess, S.G.; Leen, E.; Richards, M.W. A moving target: structure and disorder in pursuit of Myc inhibitors. Biochem Soc Trans 2017, 45, 709-717. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K.; Lewis, B.A.; Levens, D. MYC: a complex problem. Trends Cell Biol 2023, 33, 235-246. [CrossRef]

- Khaitin, A.M.; Guzenko, V.V.; Bachurin, S.S.; Demyanenko, S.V. c-Myc and FOXO3a-The Everlasting Decision Between Neural Regeneration and Degeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Metallo, S.J. Intrinsically disordered proteins are potential drug targets. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2010, 14, 481-488. [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.; Miron, C.E.; Plescia, J.; Laplante, P.; McBride, K.; Moitessier, N.; Moroy, T. Targeting MYC: From understanding its biology to drug discovery. Eur J Med Chem 2021, 213, 113137. [CrossRef]

- Sammak, S.; Zinzalla, G. Targeting protein-protein interactions (PPIs) of transcription factors: Challenges of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and regions (IDRs). Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2015, 119, 41-46. [CrossRef]

- Tsafou, K.; Tiwari, P.B.; Forman-Kay, J.D.; Metallo, S.J.; Toretsky, J.A. Targeting Intrinsically Disordered Transcription Factors: Changing the Paradigm. J Mol Biol 2018, 430, 2321-2341. [CrossRef]

- Feris, E.J.; Hinds, J.W.; Cole, M.D. Formation of a structurally-stable conformation by the intrinsically disordered MYC:TRRAP complex. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0225784. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Wang, L.; Qin, Z.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X.; Wei, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Li, Z.; et al. Phase Separation of Epstein-Barr Virus EBNA2 and Its Coactivator EBNALP Controls Gene Expression. J Virol 2020, 94. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.S.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, Z.J.; Long, Z.R.; Xiao, Y.; Liang, Z.Y.; Sun, X.; Li, H.M.; Huang, H. Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation-Related Genes Associated with Tumor Grade and Prognosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Bioinformatic Study. Int J Gen Med 2021, 14, 9671-9679. [CrossRef]

- Tai, J.; Wang, L.; Yan, Z.; Liu, J. Single-cell sequencing and transcriptome analyses in the construction of a liquid-liquid phase separation-associated gene model for rheumatoid arthritis. Front Genet 2023, 14, 1210722. [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, L.; Meng, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L. E242-E261 region of MYC regulates liquid-liquid phase separation and tumor growth by providing negative charges. J Biol Chem 2024, 300, 107836. [CrossRef]

- Soussi, T. The p53 tumor suppressor gene: from molecular biology to clinical investigation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000, 910, 121-137; discussion 137-129. [CrossRef]

- el-Deiry, W.S.; Tokino, T.; Velculescu, V.E.; Levy, D.B.; Parsons, R.; Trent, J.M.; Lin, D.; Mercer, W.E.; Kinzler, K.W.; Vogelstein, B. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 1993, 75, 817-825. [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, T.; Reed, J.C. Tumor suppressor p53 is a direct transcriptional activator of the human bax gene. Cell 1995, 80, 293-299.

- Vousden, K.H.; Prives, C. Blinded by the Light: The Growing Complexity of p53. Cell 2009, 137, 413-431. [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.P. p53, guardian of the genome. Nature 1992, 358, 15-16. [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, J.C. p53 Family isoforms. Current pharmaceutical biotechnology 2007, 8, 332-336. [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N. p53 Proteoforms and Intrinsic Disorder: An Illustration of the Protein Structure-Function Continuum Concept. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17. [CrossRef]

- Hirohashi, S. Pathology and molecular mechanisms of multistage human hepatocarcinogenesis. Princess Takamatsu Symp 1991, 22, 87-93.

- Hollstein, M.; Sidransky, D.; Vogelstein, B.; Harris, C.C. p53 mutations in human cancers. Science 1991, 253, 49-53. [CrossRef]

- Gallinger, S.; Langer, B. Primary and secondary hepatic malignancies. Curr Opin Gen Surg 1993, 257-264.

- Tabor, E. Tumor suppressor genes, growth factor genes, and oncogenes in hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J Med Virol 1994, 42, 357-365. [CrossRef]

- Tabor, E. Hepatocarcinogenesis: hepatitis viruses and altered tumor suppressor gene function. Princess Takamatsu Symp 1995, 25, 151-161.

- Tornesello, M.L.; Buonaguro, L.; Tatangelo, F.; Botti, G.; Izzo, F.; Buonaguro, F.M. Mutations in TP53, CTNNB1 and PIK3CA genes in hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections. Genomics 2013, 102, 74-83. [CrossRef]

- Eskander, E.F.; Abd-Rabou, A.A.; Yahya, S.M.; El Sherbini, A.; Mohamed, M.S.; Shaker, O.G. “P53 codon 72 single base substitution in viral hepatitis C and hepatocarcinoma incidences”. Indian J Clin Biochem 2014, 29, 3-7. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.S. Molecular events in the pathogenesis of hepadnavirus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Annu Rev Med 1994, 45, 297-323. [CrossRef]

- Koike, K.; Takada, S. Biochemistry and functions of hepatitis B virus X protein. Intervirology 1995, 38, 89-99. [CrossRef]

- Cromlish, J.A. Hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma: possible roles for HBx. Trends Microbiol 1996, 4, 270-274. [CrossRef]

- Feitelson, M.A. Hepatitis B x antigen and p53 in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 1998, 5, 367-374. [CrossRef]

- Feitelson, M.A.; Duan, L.X. Hepatitis B virus X antigen in the pathogenesis of chronic infections and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Pathol 1997, 150, 1141-1157.

- Kew, M.C. Increasing evidence that hepatitis B virus X gene protein and p53 protein may interact in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 1997, 25, 1037-1038. [CrossRef]

- Henkler, F.F.; Koshy, R. Hepatitis B virus transcriptional activators: mechanisms and possible role in oncogenesis. J Viral Hepat 1996, 3, 109-121. [CrossRef]

- Dewantoro, O.; Gani, R.A.; Akbar, N. Hepatocarcinogenesis in viral Hepatitis B infection: the role of HBx and p53. Acta Med Indones 2006, 38, 154-159.

- Kew, M.C. Hepatitis B virus x protein in the pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011, 26 Suppl 1, 144-152. [CrossRef]

- Anzola, M.; Burgos, J.J. Hepatocellular carcinoma: molecular interactions between hepatitis C virus and p53 in hepatocarcinogenesis. Expert Rev Mol Med 2003, 5, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- McGivern, D.R.; Lemon, S.M. Tumor suppressors, chromosomal instability, and hepatitis C virus-associated liver cancer. Annu Rev Pathol 2009, 4, 399-415. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.K.; McGivern, D.R. Mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepat Oncol 2014, 1, 293-307. [CrossRef]

- Tornesello, M.L.; Annunziata, C.; Tornesello, A.L.; Buonaguro, L.; Buonaguro, F.M. Human Oncoviruses and p53 Tumor Suppressor Pathway Deregulation at the Origin of Human Cancers. Cancers (Basel) 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Brychtova, V.; Hrabal, V.; Vojtesek, B. Oncogenic Viral Protein Interactions with p53 Family Proteins. Klin Onkol 2019, 32, 72-77. [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, C.J.; Meng, J.; Yang, J.Y.; Yang, M.Q.; Uversky, V.N.; Dunker, A.K. Flexible nets: disorder and induced fit in the associations of p53 and 14-3-3 with their partners. BMC Genomics 2008, 9 Suppl 1, S1. [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N.; Oldfield, C.J.; Dunker, A.K. Showing your ID: intrinsic disorder as an ID for recognition, regulation and cell signaling. J Mol Recognit 2005, 18, 343-384. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Fu, G.; Guo, Q.; Xue, S.; Luo, S.Z. Phase separation of p53 induced by its unstructured basic region and prevented by oncogenic mutations in tetramerization domain. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 222, 207-216. [CrossRef]

- Datta, D.; Navalkar, A.; Sakunthala, A.; Paul, A.; Patel, K.; Masurkar, S.; Gadhe, L.; Manna, S.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Sengupta, S.; et al. Nucleo-cytoplasmic environment modulates spatiotemporal p53 phase separation. Sci Adv 2024, 10, eads0427. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, G.A.P.; Cordeiro, Y.; Silva, J.L.; Vieira, T. Liquid-liquid phase transitions and amyloid aggregation in proteins related to cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 2019, 118, 289-331. [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Kumar, G.; Singh, V.; Sinha, S. Doxorubicin catalyses self-assembly of p53 by phase separation. Curr Res Struct Biol 2024, 7, 100133. [CrossRef]

- Kamagata, K.; Kanbayashi, S.; Honda, M.; Itoh, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Kameda, T.; Nagatsugi, F.; Takahashi, S. Liquid-like droplet formation by tumor suppressor p53 induced by multivalent electrostatic interactions between two disordered domains. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 580. [CrossRef]

- Kilic, S.; Lezaja, A.; Gatti, M.; Bianco, E.; Michelena, J.; Imhof, R.; Altmeyer, M. Phase separation of 53BP1 determines liquid-like behavior of DNA repair compartments. EMBO J 2019, 38, e101379. [CrossRef]

- Liebl, M.C.; Hofmann, T.G. Regulating the p53 Tumor Suppressor Network at PML Biomolecular Condensates. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.A.; de Oliveira, G.A.P.; Silva, J.L. The chameleonic behavior of p53 in health and disease: the transition from a client to an aberrant condensate scaffold in cancer. Essays Biochem 2022, 66, 1023-1033. [CrossRef]

- Silonov, S.A.; Mokin, Y.I.; Nedelyaev, E.M.; Smirnov, E.Y.; Kuznetsova, I.M.; Turoverov, K.K.; Uversky, V.N.; Fonin, A.V. On the Prevalence and Roles of Proteins Undergoing Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation in the Biogenesis of PML-Bodies. Biomolecules 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Usluer, S.; Spreitzer, E.; Bourgeois, B.; Madl, T. p53 Transactivation Domain Mediates Binding and Phase Separation with Poly-PR/GR. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zeng, J.; Tan, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wei, G. Multiscale simulations reveal the driving forces of p53C phase separation accelerated by oncogenic mutations. Chem Sci 2024, 15, 12806-12818. [CrossRef]

- Zong, Z.; Xie, F.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, B.; Zhou, F. Alanyl-tRNA synthetase, AARS1, is a lactate sensor and lactyltransferase that lactylates p53 and contributes to tumorigenesis. Cell 2024, 187, 2375-2392 e2333. [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, A.; Howorth, D.; Brenner, S.E.; Hubbard, T.J.; Chothia, C.; Murzin, A.G. SCOP database in 2004: refinements integrate structure and sequence family data. Nucleic Acids Res 2004, 32, D226-229. [CrossRef]

- Murzin, A.G.; Brenner, S.E.; Hubbard, T.; Chothia, C. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J Mol Biol 1995, 247, 536-540. [CrossRef]

- de Lima Morais, D.A.; Fang, H.; Rackham, O.J.; Wilson, D.; Pethica, R.; Chothia, C.; Gough, J. SUPERFAMILY 1.75 including a domain-centric gene ontology method. Nucleic Acids Res 2011, 39, D427-434. [CrossRef]

- Meszaros, B.; Simon, I.; Dosztanyi, Z. Prediction of protein binding regions in disordered proteins. PLoS Comput Biol 2009, 5, e1000376. [CrossRef]

- Hornbeck, P.V.; Kornhauser, J.M.; Tkachev, S.; Zhang, B.; Skrzypek, E.; Murray, B.; Latham, V.; Sullivan, M. PhosphoSitePlus: a comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res 2012, 40, D261-270. [CrossRef]

- Fog, C.K.; Galli, G.G.; Lund, A.H. PRDM proteins: important players in differentiation and disease. Bioessays 2012, 34, 50-60. [CrossRef]

- Han, B.Y.; Seah, M.K.Y.; Brooks, I.R.; Quek, D.H.P.; Huxley, D.R.; Foo, C.S.; Lee, L.T.; Wollmann, H.; Guo, H.; Messerschmidt, D.M.; et al. Global translation during early development depends on the essential transcription factor PRDM10. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 3603. [CrossRef]

- Di Zazzo, E.; De Rosa, C.; Abbondanza, C.; Moncharmont, B. PRDM Proteins: Molecular Mechanisms in Signal Transduction and Transcriptional Regulation. Biology (Basel) 2013, 2, 107-141. [CrossRef]

- Fumasoni, I.; Meani, N.; Rambaldi, D.; Scafetta, G.; Alcalay, M.; Ciccarelli, F.D. Family expansion and gene rearrangements contributed to the functional specialization of PRDM genes in vertebrates. BMC Evol Biol 2007, 7, 187. [CrossRef]

- Hohenauer, T.; Moore, A.W. The Prdm family: expanding roles in stem cells and development. Development 2012, 139, 2267-2282. [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, A.; Federico, A.; Rienzo, M.; Gazzerro, P.; Bifulco, M.; Ciccodicola, A.; Casamassimi, A.; Abbondanza, C. PR/SET Domain Family and Cancer: Novel Insights from the Cancer Genome Atlas. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [CrossRef]

- van de Beek, I.; Glykofridis, I.E.; Oosterwijk, J.C.; van den Akker, P.C.; Diercks, G.F.H.; Bolling, M.C.; Waisfisz, Q.; Mensenkamp, A.R.; Balk, J.A.; Zwart, R.; et al. PRDM10 directs FLCN expression in a novel disorder overlapping with Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome and familial lipomatosis. Hum Mol Genet 2023, 32, 1223-1235. [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Xu, H.; Wu, R.; Niu, J.; Li, S. Aberrant DNA methylation profile of hepatitis B virus infection. J Med Virol 2019, 91, 81-92. [CrossRef]

- Dunker, A.K.; Lawson, J.D.; Brown, C.J.; Williams, R.M.; Romero, P.; Oh, J.S.; Oldfield, C.J.; Campen, A.M.; Ratliff, C.M.; Hipps, K.W.; et al. Intrinsically disordered protein. J Mol Graph Model 2001, 19, 26-59. [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.M.; Obradovic, Z.; Mathura, V.; Braun, W.; Garner, E.C.; Young, J.; Takayama, S.; Brown, C.J.; Dunker, A.K. The protein non-folding problem: amino acid determinants of intrinsic order and disorder. Pac Symp Biocomput 2001, 89-100.

- Radivojac, P.; Iakoucheva, L.M.; Oldfield, C.J.; Obradovic, Z.; Uversky, V.N.; Dunker, A.K. Intrinsic disorder and functional proteomics. Biophys J 2007, 92, 1439-1456. [CrossRef]

- Vacic, V.; Uversky, V.N.; Dunker, A.K.; Lonardi, S. Composition Profiler: a tool for discovery and visualization of amino acid composition differences. BMC Bioinformatics 2007, 8, 211. [CrossRef]

- Engert, C.G.; Droste, R.; van Oudenaarden, A.; Horvitz, H.R. A Caenorhabditis elegans protein with a PRDM9-like SET domain localizes to chromatin-associated foci and promotes spermatocyte gene expression, sperm production and fertility. PLoS Genet 2018, 14, e1007295. [CrossRef]

- Cerdan, C.; McIntyre, B.A.; Mechael, R.; Levadoux-Martin, M.; Yang, J.; Lee, J.B.; Bhatia, M. Activin A promotes hematopoietic fated mesoderm development through upregulation of brachyury in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 2012, 21, 2866-2877. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, D.G.; Bhatt, S.; Herrmann, B.G. Expression pattern of the mouse T gene and its role in mesoderm formation. Nature 1990, 343, 657-659. [CrossRef]

- Le Gouar, M.; Guillou, A.; Vervoort, M. Expression of a SoxB and a Wnt2/13 gene during the development of the mollusc Patella vulgata. Dev Genes Evol 2004, 214, 250-256. [CrossRef]

- Risbud, M.V.; Shapiro, I.M. Notochordal cells in the adult intervertebral disc: new perspective on an old question. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 2011, 21, 29-41. [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, H.E.; Dall’Agnese, A.; Park, W.D.; Shamim, M.H.; Dubrulle, J.; Johnson, H.L.; Stossi, F.; Cogswell, P.; Sommer, J.; Levy, J.; et al. Targeted brachyury degradation disrupts a highly specific autoregulatory program controlling chordoma cell identity. Cell Rep Med 2021, 2, 100188. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, D.H.; David, J.M.; Dominguez, C.; Palena, C. Development of Cancer Vaccines Targeting Brachyury, a Transcription Factor Associated with Tumor Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Cells Tissues Organs 2017, 203, 128-138. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, H.; McFarlane, R.J.; Wakeman, J.A. Brachyury: Strategies for Drugging an Intractable Cancer Therapeutic Target. Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 271-273. [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Bai, J.; Zhang, Y. Current understanding of brachyury in chordoma. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2023, 189010. [CrossRef]

- Walcott, B.P.; Nahed, B.V.; Mohyeldin, A.; Coumans, J.V.; Kahle, K.T.; Ferreira, M.J. Chordoma: current concepts, management, and future directions. Lancet Oncol 2012, 13, e69-76. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.E.; Barbaux, S.; Hoess, K.; Fraterman, S.; Whitehead, A.S.; Mitchell, L.E. The human T locus and spina bifida risk. Hum Genet 2004, 115, 475-482. [CrossRef]

- Postma, A.V.; Alders, M.; Sylva, M.; Bilardo, C.M.; Pajkrt, E.; van Rijn, R.R.; Schulte-Merker, S.; Bulk, S.; Stefanovic, S.; Ilgun, A.; et al. Mutations in the T (brachyury) gene cause a novel syndrome consisting of sacral agenesis, abnormal ossification of the vertebral bodies and a persistent notochordal canal. J Med Genet 2014, 51, 90-97. [CrossRef]

- Chase, D.H.; Bebenek, A.M.; Nie, P.; Jaime-Figueroa, S.; Butrin, A.; Castro, D.A.; Hines, J.; Linhares, B.M.; Crews, C.M. Development of a Small Molecule Downmodulator for the Transcription Factor Brachyury. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2024, 63, e202316496. [CrossRef]

- Peters, T., Jr. Serum albumin. Adv Protein Chem 1985, 37, 161-245. [CrossRef]

- Peters, T. All About Albumin: Biochemistry, Genetics, and Medical Applications; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 1996.

- Evans, T.W. Review article: albumin as a drug--biological effects of albumin unrelated to oncotic pressure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002, 16 Suppl 5, 6-11. [CrossRef]

- Mendez, C.M.; McClain, C.J.; Marsano, L.S. Albumin therapy in clinical practice. Nutr Clin Pract 2005, 20, 314-320. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, K.O. An analysis of measured and calculated calcium quantities in serum. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1978, 38, 659-667. [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, R.A.; Shearer, W.T.; Gurd, F.R. Sites of binding of copper (II) ion by peptide (1-24) of bovine serum albumin. J Biol Chem 1968, 243, 3817-3825. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B. Albumin as the major plasma protein transporting metals. Life Chem. Reports 1983, 1, 165-209.

- Gurd, F.R.; Wilcox, P.E. Complex formation between metallic cations and proteins, peptides and amino acids. Adv Protein Chem 1956, 11, 311-427. [CrossRef]

- Nandedkar, A.K.; Nurse, C.E.; Friedberg, F. Mn++ binding by plasma proteins. Int J Pept Protein Res 1973, 5, 279-281. [CrossRef]

- Klopfenstein, W.E. Thermodynamics of binding lysolecithin to serum albumin. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Lipids and Lipid Metabolism 1969, 187, 272-274. [CrossRef]

- Roda, A.; Cappelleri, G.; Aldini, R.; Roda, E.; Barbara, L. Quantitative aspects of the interaction of bile acids with human serum albumin. Journal of lipid research 1982, 23, 490-495. [CrossRef]

- Savu, L.; Benassayag, C.; Vallette, G.; Christeff, N.; Nunez, E. Mouse alpha 1-fetoprotein and albumin. A comparison of their binding properties with estrogen and fatty acid ligands. J Biol Chem 1981, 256, 9414-9418. [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, J. Studies of the affinity of human serum albumin for binding of bilirubin at different temperatures and ionic strength. Int J Pept Protein Res 1977, 9, 235-239. [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, W.H.; Crepy, O. Steroid-protein interaction with particular reference to testosterone binding by human serum. J Biol Chem 1967, 242, 182-189. [CrossRef]

- Unger, W. Binding of prostaglandin to human serum albumin. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 1972, 24, 470-477. [CrossRef]

- Sollenne, N.P.; Wu, H.L.; Means, G.E. Disruption of the tryptophan binding site in the human serum albumin dimer. Arch Biochem Biophys 1981, 207, 264-269. [CrossRef]

- Kragh-Hansen, U. Molecular aspects of ligand binding to serum albumin. Pharmacol Rev 1981, 33, 17-53. [CrossRef]

- Biere, A.L.; Ostaszewski, B.; Stimson, E.R.; Hyman, B.T.; Maggio, J.E.; Selkoe, D.J. Amyloid beta-peptide is transported on lipoproteins and albumin in human plasma. J Biol Chem 1996, 271, 32916-32922. [CrossRef]

- He, X.M.; Carter, D.C. Atomic structure and chemistry of human serum albumin. Nature 1992, 358, 209-215. [CrossRef]

- Fanali, G.; di Masi, A.; Trezza, V.; Marino, M.; Fasano, M.; Ascenzi, P. Human serum albumin: from bench to bedside. Mol Aspects Med 2012, 33, 209-290. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Lis, C.G. Pretreatment serum albumin as a predictor of cancer survival: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J 2010, 9, 69. [CrossRef]

- Koga, M.; Kasayama, S. Clinical impact of glycated albumin as another glycemic control marker. Endocr J 2010, 57, 751-762. [CrossRef]

- Sbarouni, E.; Georgiadou, P.; Voudris, V. Ischemia modified albumin changes - review and clinical implications. Clin Chem Lab Med 2011, 49, 177-184. [CrossRef]

- Shevtsova, A.; Gordiienko, I.; Tkachenko, V.; Ushakova, G. Ischemia-Modified Albumin: Origins and Clinical Implications. Dis Markers 2021, 2021, 9945424. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.A.; Greenwald, H.S.; Sheikh, L.; Wooten, D.A.; Malhotra, A.; Schooley, R.T.; Sweeney, D.A. Predictors of Acute Liver Failure in Patients With Acute Hepatitis A: An Analysis of the 2016-2018 San Diego County Hepatitis A Outbreak. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019, 6, ofz467. [CrossRef]

- Tillmann, H.L.; Manns, M.P.; Rudolph, K.L. Merging models of hepatitis C virus pathogenesis. Semin Liver Dis 2005, 25, 84-92. [CrossRef]

- Chitturi, S.; George, J. Predictors of liver-related complications in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Ann Med 2000, 32, 588-591. [CrossRef]

- Jeng, L.B.; Li, T.C.; Hsu, S.C.; Chan, W.L.; Teng, C.F. Association of Low Serum Albumin Level with Higher Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence in Patients with Hepatitis B Virus Pre-S2 Mutant after Curative Surgical Resection. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Michalak, T.; Krawczynski, K.; Ostrowski, J.; Nowoslawski, A. Hepatitis B surface antigen and albumin in human hepatocytes. An immunofluorescent and immunoelectron microscopic study. Gastroenterology 1980, 79, 1151-1158. [CrossRef]

- Thung, S.N.; Wang, D.F.; Fasy, T.M.; Hood, A.; Gerber, M.A. Hepatitis B surface antigen binds to human serum albumin cross-linked by transglutaminase. Hepatology 1989, 9, 726-730. [CrossRef]

- Halder, K.; Sengupta, P.; Chaki, S.; Saha, R.; Dasgupta, S. Understanding Conformational Changes in Human Serum Albumin and Its Interactions with Gold Nanorods: Do Flexible Regions Play a Role in Corona Formation? Langmuir 2023, 39, 1651-1664. [CrossRef]

- Litus, E.A.; Permyakov, S.E.; Uversky, V.N.; Permyakov, E.A. Intrinsically disordered regions in serum albumin: what are they for? Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics 2018, 76, 39-57. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Bevan, M.J. CD8(+) T cells: foot soldiers of the immune system. Immunity 2011, 35, 161-168. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Zhu, C.; McShan, A.C. Structure, function, and immunomodulation of the CD8 co-receptor. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1412513. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, W.M.; Huang, Z.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Tong, Y.Y.; Chang, G.B.; Duan, X.J.; Chen, G.H. DNA methylation and regulation of the CD8A after duck hepatitis virus type 1 infection. PLoS One 2014, 9, e88023. [CrossRef]

- Tregaskes, C.; Kong, F.; Paramithiotis, E.; Chen, C.; Ratcliffe, M.; Davison, T.; Young, J. Identification and analysis of the expression of CD8 alpha beta and CD8 alpha alpha isoforms in chickens reveals a major TCR-gamma delta CD8 alpha beta subset of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 1995, 154, 4485-4494. [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.F.; Jakobsen, B.K. Molecular interactions of coreceptor CD8 and MHC class I: the molecular basis for functional coordination with the T-cell receptor. Immunol Today 2000, 21, 630-636. [CrossRef]

- Alromaih, S.; Mfuna-Endam, L.; Bosse, Y.; Filali-Mouhim, A.; Desrosiers, M. CD8A gene polymorphisms predict severity factors in chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2013, 3, 605-611. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Lu, H.; Xiong, M. Identifying Immune Cell Infiltration and Effective Diagnostic Biomarkers in Rheumatoid Arthritis by Bioinformatics Analysis. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 726747. [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, S. Comparative expression analysis of PD-1, PD-L1, and CD8A in lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Transl Med 2020, 8, 1478. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zuo, L.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, X.; Zou, J.; Xu, H. CD8A is a Promising Biomarker Associated with Immunocytes Infiltration in Hyperoxia-Induced Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. J Inflamm Res 2023, 16, 1653-1669. [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.M.; Liang, S.; Zhou, B. Revealing immune infiltrate characteristics and potential immune-related genes in hepatic fibrosis: based on bioinformatics, transcriptomics and q-PCR experiments. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1133543. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Xie, D.; Azami, N.L.B.; Lu, L.; Huang, Y.; Ye, W.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, M. CCL20 and CD8A as potential diagnostic biomarkers for HBV-induced liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28329. [CrossRef]

- Sriraman, S.K.; Davies, C.W.; Gill, H.; Kiefer, J.R.; Yin, J.; Ogasawara, A.; Urrutia, A.; Javinal, V.; Lin, Z.; Seshasayee, D.; et al. Development of an (18)F-labeled anti-human CD8 VHH for same-day immunoPET imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2023, 50, 679-691. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mirazee, J.M.; Skorupka, K.A.; Matsuo, H.; Youkharibache, P.; Taylor, N.; Walters, K.J. The CD8alpha hinge is intrinsically disordered with a dynamic exchange that includes proline cis-trans isomerization. J Magn Reson 2022, 340, 107234. [CrossRef]

- Bergstrand, C.G.; Czar, B. Demonstration of a new protein fraction in serum from the human fetus. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1956, 8, 174. [CrossRef]

- Galdo, A.; Casado, J.P.; Talavera, R. [Demonstration of a new protein fraction in the serum of the human fetus by means of paper electrophoresis]. Arch Fr Pediatr 1959, 16, 954-962.

- Ruoslahti, E.; Seppala, M. alpha-Foetoprotein in normal human serum. Nature 1972, 235, 161-162. [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, H.F. Chemistry and biology of alpha-fetoprotein. Adv Cancer Res 1991, 56, 253-312. [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, J.R.; Uversky, V.N. Structure and function of alpha-fetoprotein: a biophysical overview. Biochim Biophys Acta 2000, 1480, 41-56. [CrossRef]

- Mizejewski, G.J. Alpha-fetoprotein structure and function: relevance to isoforms, epitopes, and conformational variants. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2001, 226, 377-408. [CrossRef]

- Terentiev, A.A.; Moldogazieva, N.T. Structural and functional mapping of alpha-fetoprotein. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2006, 71, 120-132. [CrossRef]

- Tatarinov, J. Content of embryo-specific alpha-globulin in the blood serum of human fetus, newborn and adult man in primary cancer. Vopr. Med. Khim. 1964, 10, 90-91.

- Abelev, G. Alpha-fetoprotein in ontogenesis and its association with malignant tumors. Advances in cancer research 1971, 14, 295-358.

- Tatarinov, Y.S. Detection of embryospecific alpha-globulin in serum of patients with primary liver cancer. In Proceedings of the 1st All-Union Biochem Congress Abstract Book. Moscow–Leningrad, 1963.

- Okuda, K.; Kotoda, K.; Obata, H.; Hayashi, N.; Hisamitsu, T. Clinical observations during a relatively early stage of hepatocellular carcinoma, with special reference to serum alpha-fetoprotein levels. Gastroenterology 1975, 69, 226-234. [CrossRef]

- Terentiev, A.A.; Moldogazieva, N.T. Alpha-fetoprotein: a renaissance. Tumour Biol 2013, 34, 2075-2091. [CrossRef]

- Nochomovitz, L.E.; DeLa Torre, F.E.; Rosai, J. Pathology of germ cell tumors of the testis. Urol Clin North Am 1977, 4, 359-378. [CrossRef]

- Itoh, T.; Kishi, K.; Tojo, M.; Kitajima, N.; Kinoshita, Y.; Inatome, T.; Fukuzaki, H.; Nishiyama, N.; Tachibana, H.; Takahashi, H.; et al. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas with elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein levels: a case report and a review of 28 cases reported in Japan. Gastroenterol Jpn 1992, 27, 785-791. [CrossRef]

- Yoshiki, T.; Itoh, T.; Shirai, T.; Noro, T.; Tomino, Y.; Hama Jima, T.I. Primary intracranial yolk sac tumor: immunofluorescent demonstration of alpha-fetoprotein synthesis. Cancer 1976, 37, 2343-2348. [CrossRef]

- Seppala, M.; Ruoslahti, E. Alpha fetoprotein: Physiology and pathology during pregnancy and application to antenatal diagnosis. J Perinat Med 1973, 1, 104-113. [CrossRef]

- Brock, D.J.; Scrimgeour, J.B.; Nelson, M.M. Amniotic fluid alphafetoprotein measurements in the early prenatal diagnosis of central nervous system disorders. Clin Genet 1975, 7, 163-169. [CrossRef]

- Seppala, M. Fetal pathophysiology of human alpha-fetoprotein. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1975, 259, 59-73. [CrossRef]

- Ruoslahti, E.; Seppala, M. alpha-Fetoprotein in cancer and fetal development. Adv Cancer Res 1979, 29, 275-346. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.S.; Cheng, K.S.; Lai, Y.C.; Wu, C.H.; Chen, T.K.; Lee, C.L.; Chen, D.S. Decreasing serum alpha-fetoprotein levels in predicting poor prognosis of acute hepatic failure in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol 2002, 37, 626-632. [CrossRef]

- Di Bisceglie, A.M.; Hoofnagle, J.H. Elevations in serum alpha-fetoprotein levels in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Cancer 1989, 64, 2117-2120. [CrossRef]

- Liaw, Y.F.; Tai, D.I.; Chen, T.J.; Chu, C.M.; Huang, M.J. Alpha-fetoprotein changes in the course of chronic hepatitis: relation to bridging hepatic necrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver 1986, 6, 133-137. [CrossRef]

- Bayati, N.; Silverman, A.L.; Gordon, S.C. Serum alpha-fetoprotein levels and liver histology in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol 1998, 93, 2452-2456. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, N.S.; Blue, D.E.; Hankin, R.; Hunter, S.; Bayati, N.; Silverman, A.L.; Gordon, S.C. Serum alpha-fetoprotein levels in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Relationships with serum alanine aminotransferase values, histologic activity index, and hepatocyte MIB-1 scores. Am J Clin Pathol 1999, 111, 811-816. [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.W.; Hwang, S.J.; Luo, J.C.; Lai, C.R.; Tsay, S.H.; Li, C.P.; Wu, J.C.; Chang, F.Y.; Lee, S.D. Clinical, virologic, and pathologic significance of elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein levels in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Gastroenterol 2001, 32, 240-244. [CrossRef]

- Tagliabracci, V.S.; Wiley, S.E.; Guo, X.; Kinch, L.N.; Durrant, E.; Wen, J.; Xiao, J.; Cui, J.; Nguyen, K.B.; Engel, J.L.; et al. A Single Kinase Generates the Majority of the Secreted Phosphoproteome. Cell 2015, 161, 1619-1632. [CrossRef]

- Yoshima, H.; Mizuochi, T.; Ishii, M.; Kobata, A. Structure of the asparagine-linked sugar chains of alpha-fetoprotein purified from human ascites fluid. Cancer Res 1980, 40, 4276-4281.

- Mizejewski, G. α-fetoprotein as a biologic response modifier: relevance to domain and subdomain structure. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine 1997, 215, 333-362. [CrossRef]

- Breborowicz, J. Microheterogeneity of human alphafetoprotein. Tumour Biol 1988, 9, 3-14. [CrossRef]

- Lester, E.P.; Miller, J.B.; Yachnin, S. Human alpha-fetoprotein: immunosuppressive activity and microheterogeneity. Immunol Commun 1978, 7, 137-161. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Liu, N.; Gao, X.; Zhu, W.; Liu, K.; Wu, C.; Yan, R.; Zhang, J.; Gao, X.; Yao, Y.; et al. Uniform thin ice on ultraflat graphene for high-resolution cryo-EM. Nat Methods 2023, 20, 123-130. [CrossRef]

- Morinaga, T.; Sakai, M.; Wegmann, T.G.; Tamaoki, T. Primary structures of human alpha-fetoprotein and its mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1983, 80, 4604-4608. [CrossRef]

- Eang, R.; Girbal-Neuhauser, E.; Xu, B.; Gairin, J.E. Characterization and differential expression of a newly identified phosphorylated isoform of the human 20S proteasome beta7 subunit in tumor vs. normal cell lines. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2009, 23, 215-224. [CrossRef]

- Jayarapu, K.; Griffin, T.A. Protein–protein interactions among human 20S proteasome subunits and proteassemblin. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2004, 314, 523-528. [CrossRef]

- Rho, J.H.; Qin, S.; Wang, J.Y.; Roehrl, M.H. Proteomic expression analysis of surgical human colorectal cancer tissues: up-regulation of PSB7, PRDX1, and SRP9 and hypoxic adaptation in cancer. J Proteome Res 2008, 7, 2959-2972. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.Y.; Wang, J.Y.; Roehrl, M.H.A. An Investigation Into the Prognostic Significance of High Proteasome PSB7 Protein Expression in Colorectal Cancer. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020, 7, 401. [CrossRef]

- Munkacsy, G.; Abdul-Ghani, R.; Mihaly, Z.; Tegze, B.; Tchernitsa, O.; Surowiak, P.; Schafer, R.; Gyorffy, B. PSMB7 is associated with anthracycline resistance and is a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2010, 102, 361-368. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, X.; Shi, S.; Su, H.; Bai, X.; Cai, G.; Yang, F.; Xie, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Bioinformatics analysis of proteomic profiles during the process of anti-Thy1 nephritis. Mol Cell Proteomics 2012, 11, M111 008755. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.X.; Tiedemann, R.; Shi, C.X.; Yin, H.; Schmidt, J.E.; Bruins, L.A.; Keats, J.J.; Braggio, E.; Sereduk, C.; Mousses, S.; et al. RNAi screen of the druggable genome identifies modulators of proteasome inhibitor sensitivity in myeloma including CDK5. Blood 2011, 117, 3847-3857. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Miao, J.; Hu, J.; Li, F.; Gao, D.; Chen, H.; Feng, Y.; Shen, Y.; He, A. PSMB7 Is a Key Gene Involved in the Development of Multiple Myeloma and Resistance to Bortezomib. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 684232. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Qin, S.; Hou, X.; Qian, X.; Xia, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Chen, C.; Yang, Q.; Miele, L.; et al. Proteomic-based analysis for identification of proteins involved in 5-fluorouracil resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Pharm Des 2014, 20, 81-87. [CrossRef]

- Rouette, A.; Trofimov, A.; Haberl, D.; Boucher, G.; Lavallee, V.P.; D’Angelo, G.; Hebert, J.; Sauvageau, G.; Lemieux, S.; Perreault, C. Expression of immunoproteasome genes is regulated by cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic factors in human cancers. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 34019. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; You, G.; Guo, W.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Geng, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Zan, J.; Zheng, L. Bioinformatic Analysis and Experimental Validation of Ubiquitin-Proteasomal System-Related Hub Genes as Novel Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease. J Integr Neurosci 2023, 22, 138. [CrossRef]

- Ebstein, F.; Poli Harlowe, M.C.; Studencka-Turski, M.; Kruger, E. Contribution of the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) to the Pathogenesis of Proteasome-Associated Autoinflammatory Syndromes (PRAAS). Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2756. [CrossRef]

- Makjaroen, J.; Somparn, P.; Hodge, K.; Poomipak, W.; Hirankarn, N.; Pisitkun, T. Comprehensive Proteomics Identification of IFN-lambda3-regulated Antiviral Proteins in HBV-transfected Cells. Mol Cell Proteomics 2018, 17, 2197-2215. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kwong, J.; Sun, E.; Liang, T.J. Proteasome complex as a potential cellular target of hepatitis B virus X protein. Journal of virology 1996, 70, 5582-5591. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Torii, N.; Furusaka, A.; Malayaman, N.; Hu, Z.; Liang, T.J. Structural and functional characterization of interaction between hepatitis B virus X protein and the proteasome complex. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 15157-15165. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Doo, E.; Coux, O.; Goldberg, A.L.; Liang, T.J. Hepatitis B virus X protein is both a substrate and a potential inhibitor of the proteasome complex. Journal of virology 1999, 73, 7231-7240. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Protzer, U.; Hu, Z.; Jacob, J.; Liang, T.J. Inhibition of cellular proteasome activities enhances hepadnavirus replication in an HBX-dependent manner. Journal of virology 2004, 78, 4566-4572. [CrossRef]

- James, S.A.; Ong, H.S.; Hari, R.; Khan, A.M. A systematic bioinformatics approach for large-scale identification and characterization of host-pathogen shared sequences. BMC genomics 2021, 22, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cimermancic, P.; Yu, C.; Schweitzer, A.; Chopra, N.; Engel, J.L.; Greenberg, C.; Huszagh, A.S.; Beck, F.; Sakata, E.; et al. Molecular Details Underlying Dynamic Structures and Regulation of the Human 26S Proteasome. Mol Cell Proteomics 2017, 16, 840-854. [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, A.; Aufderheide, A.; Rudack, T.; Beck, F.; Pfeifer, G.; Plitzko, J.M.; Sakata, E.; Schulten, K.; Forster, F.; Baumeister, W. Structure of the human 26S proteasome at a resolution of 3.9 A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 7816-7821. [CrossRef]

- Stenmark, H.; Olkkonen, V.M. The Rab GTPase family. Genome Biol 2001, 2, REVIEWS3007. [CrossRef]

- Kirsten, M.L.; Baron, R.A.; Seabra, M.C.; Ces, O. Rab1a and Rab5a preferentially bind to binary lipid compositions with higher stored curvature elastic energy. Mol Membr Biol 2013, 30, 303-314. [CrossRef]

- Castellvi-Bel, S.; Mila, M. Genes responsible for nonspecific mental retardation. Mol Genet Metab 2001, 72, 104-108. [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Ng-Cordell, E.; Hanna, N.; Brkic, D.; Baker, K. The neurodevelopmental spectrum of synaptic vesicle cycling disorders. J Neurochem 2021, 157, 208-228. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, L.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, W. GDP dissociation inhibitor 1 (GDI1) attenuates beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s diseases. Neurosci Lett 2024, 818, 137564. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Lin, H.; Zhang, X.; Song, P.; He, X.; Zhong, J.; Shi, J. Overexpression of GDP dissociation inhibitor 1 gene associates with the invasiveness and poor outcomes of colorectal cancer. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 5595-5606. [CrossRef]

- Kiyota, A.; Iwama, S.; Sugimura, Y.; Takeuchi, S.; Takagi, H.; Iwata, N.; Nakashima, K.; Suzuki, H.; Nishioka, T.; Kato, T.; et al. Identification of the novel autoantigen candidate Rab GDP dissociation inhibitor alpha in isolated adrenocorticotropin deficiency. Endocr J 2015, 62, 153-160. [CrossRef]

- Erdem-Eraslan, L.; Heijsman, D.; de Wit, M.; Kremer, A.; Sacchetti, A.; van der Spek, P.J.; Sillevis Smitt, P.A.; French, P.J. Tumor-specific mutations in low-frequency genes affect their functional properties. J Neurooncol 2015, 122, 461-470. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, H.; Jin, X.; Zhao, L. Loss of RhoGDI is a novel independent prognostic factor in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2013, 6, 2535-2541.

- Lai, M.C.; Zhu, Q.Q.; Owusu-Ansah, K.G.; Zhu, Y.B.; Yang, Z.; Xie, H.Y.; Zhou, L.; Wu, L.M.; Zheng, S.S. Prognostic value of Rho GDP dissociation inhibitors in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma following liver transplantation. Oncol Lett 2017, 14, 1395-1402. [CrossRef]

- Montaldo, C.; Terri, M.; Riccioni, V.; Battistelli, C.; Bordoni, V.; D’Offizi, G.; Prado, M.G.; Trionfetti, F.; Vescovo, T.; Tartaglia, E.; et al. Fibrogenic signals persist in DAA-treated HCV patients after sustained virological response. J Hepatol 2021, 75, 1301-1311. [CrossRef]