Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

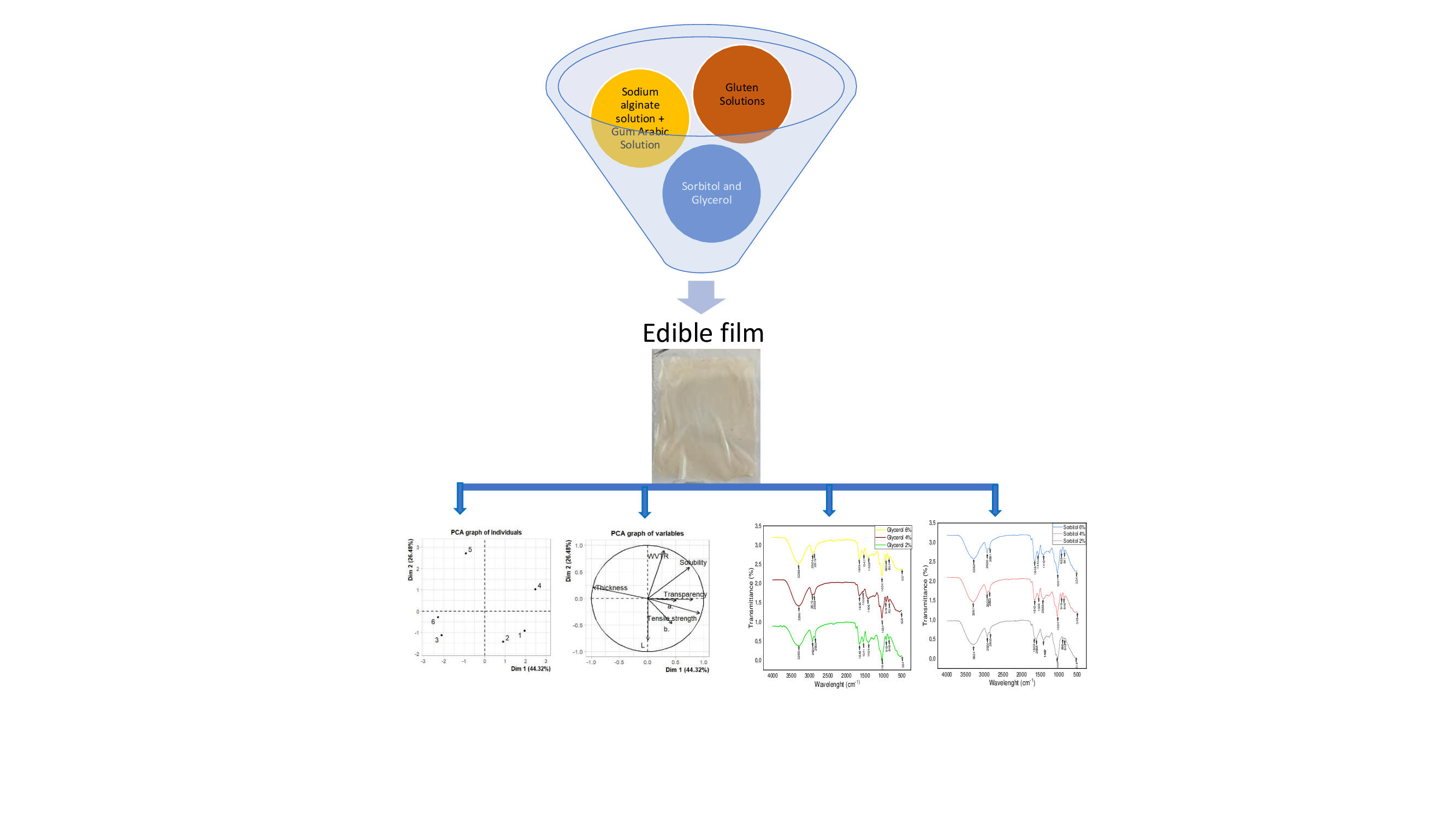

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

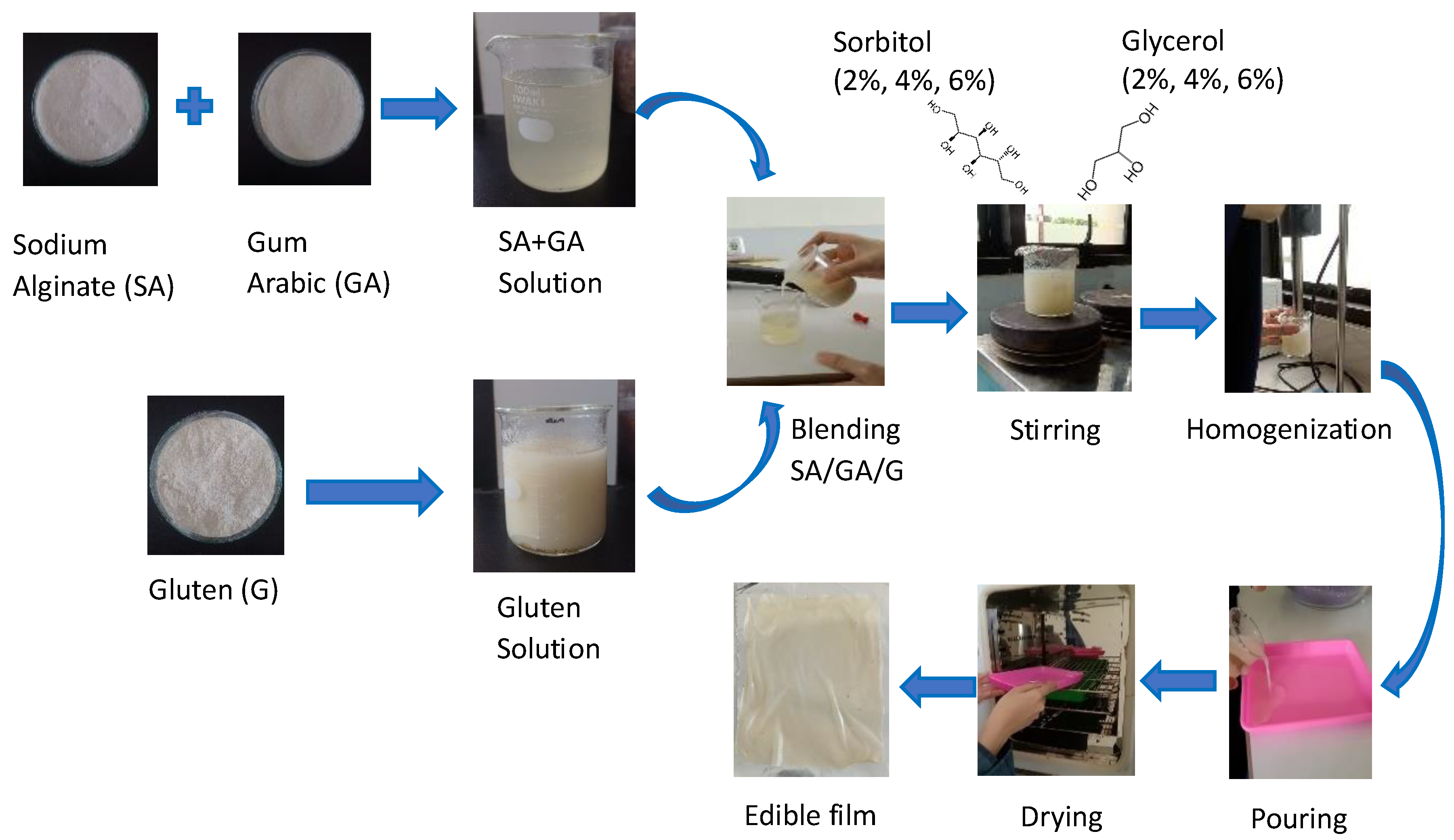

2.2. Preparation of Wheat Gluten Solution

2.3. Preparation of Sodium Alginate and Gum Arabic Solution

2.4. Preparation of Edible Film

2.5. Film Characterizations

2.5.1. Thickness

2.5.2. Film Solubility in Water

2.5.3. Tensile Strength

2.5.4. Water Vapor Transmission Rate

2.5.5. Color

2.5.6. Transparency

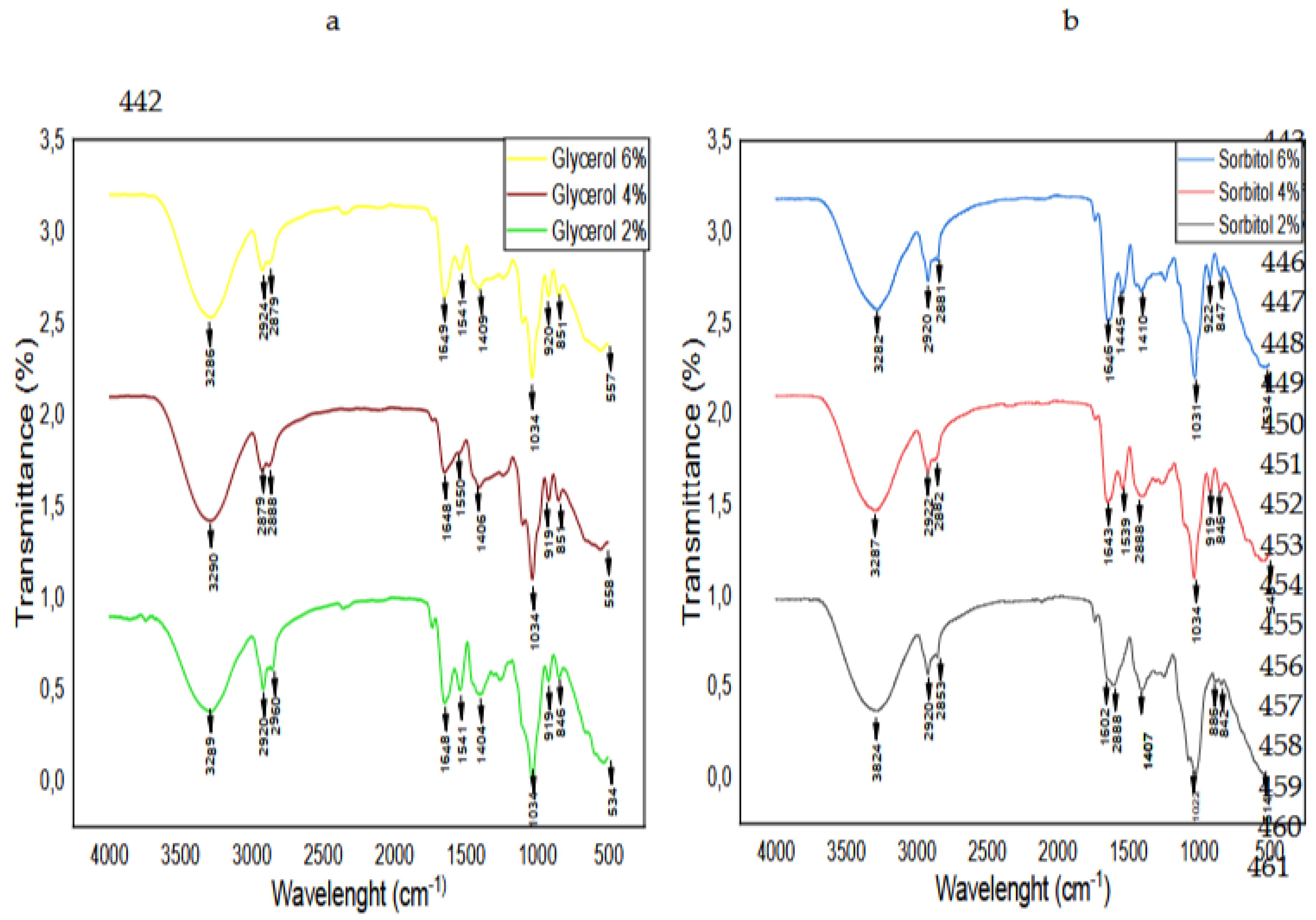

2.5.7. FTIR

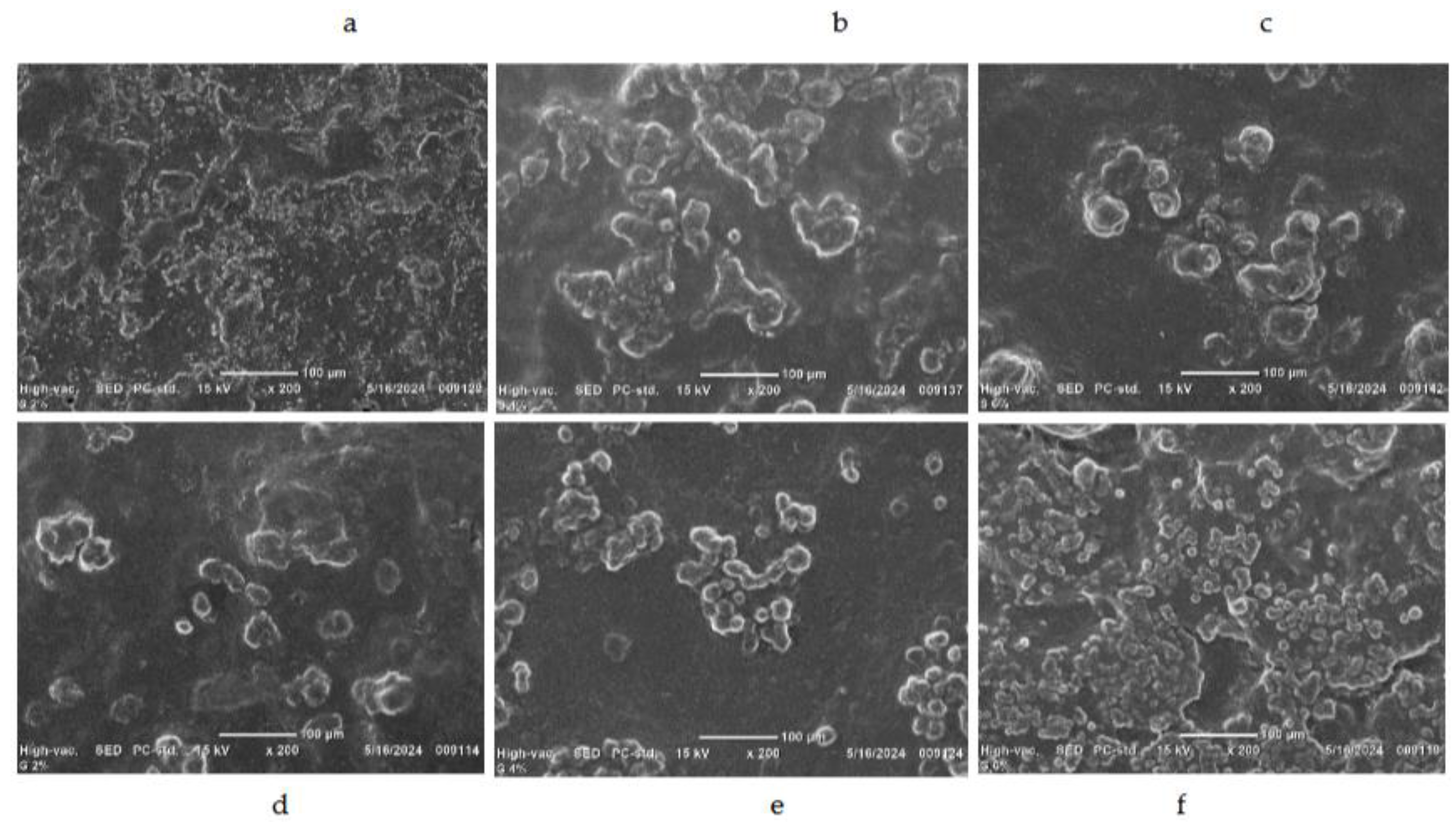

2.5.8. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) of Films

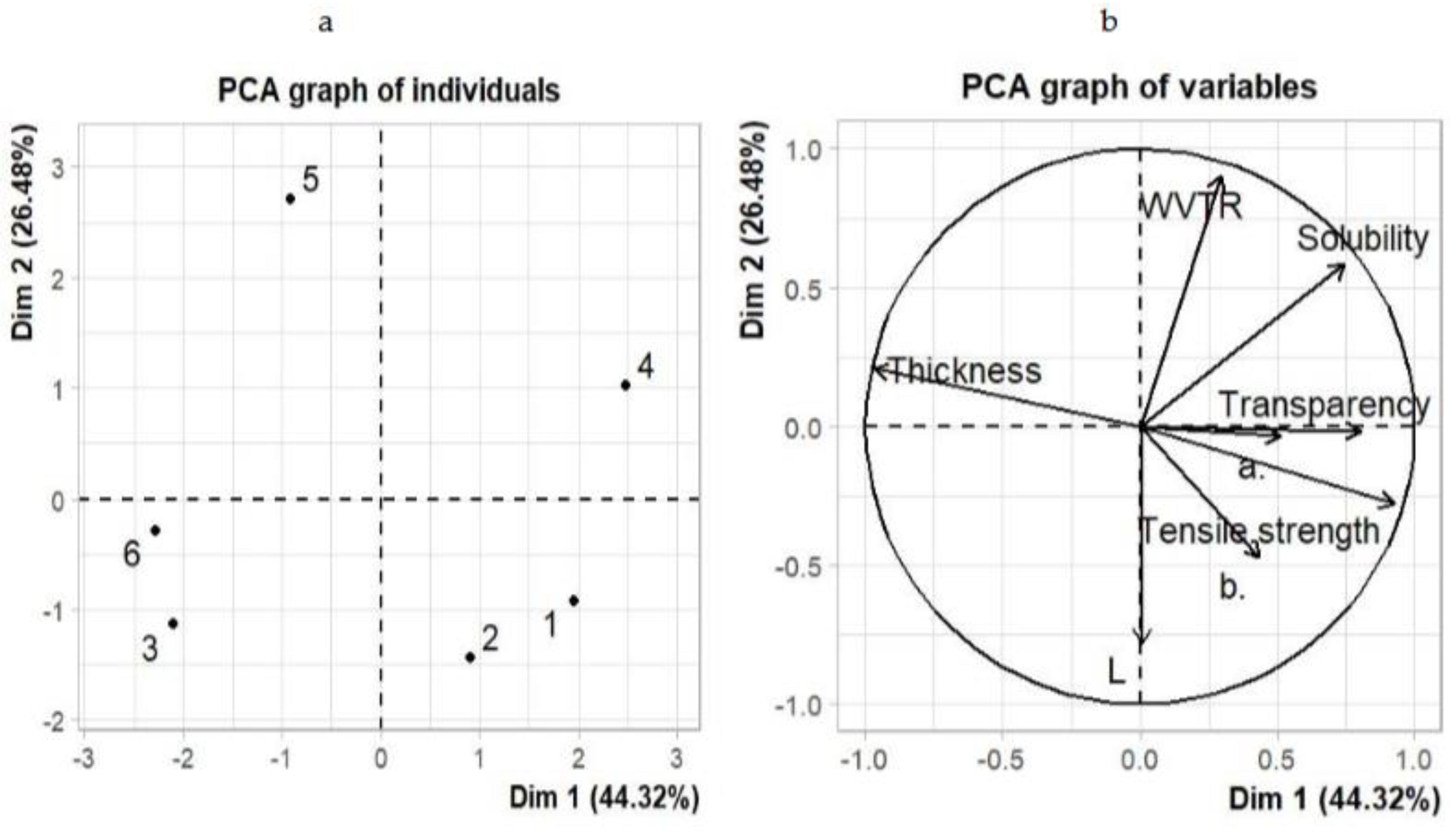

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Thickness

3.2. Color

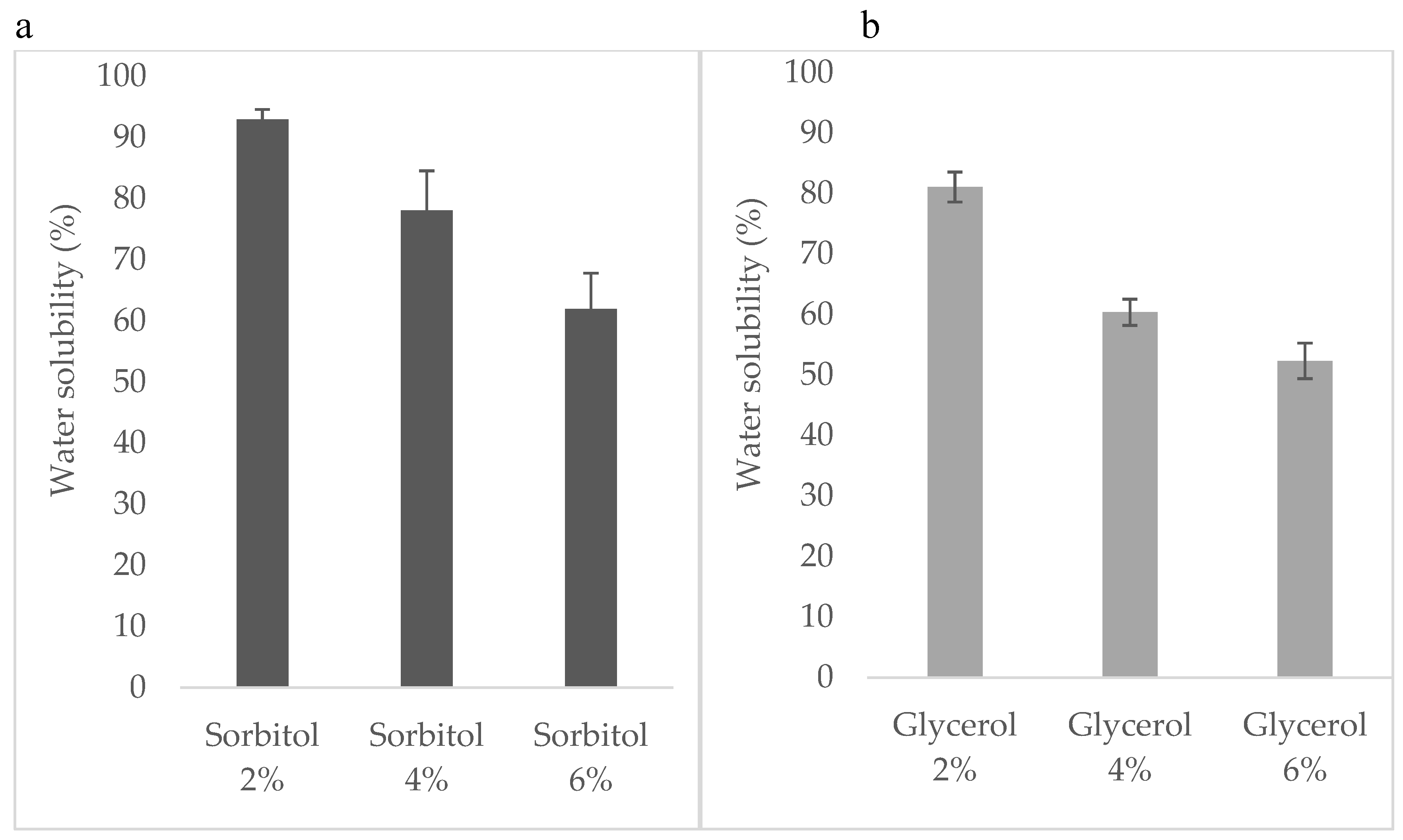

3.3. Solubility

3.4. Tensile Strength

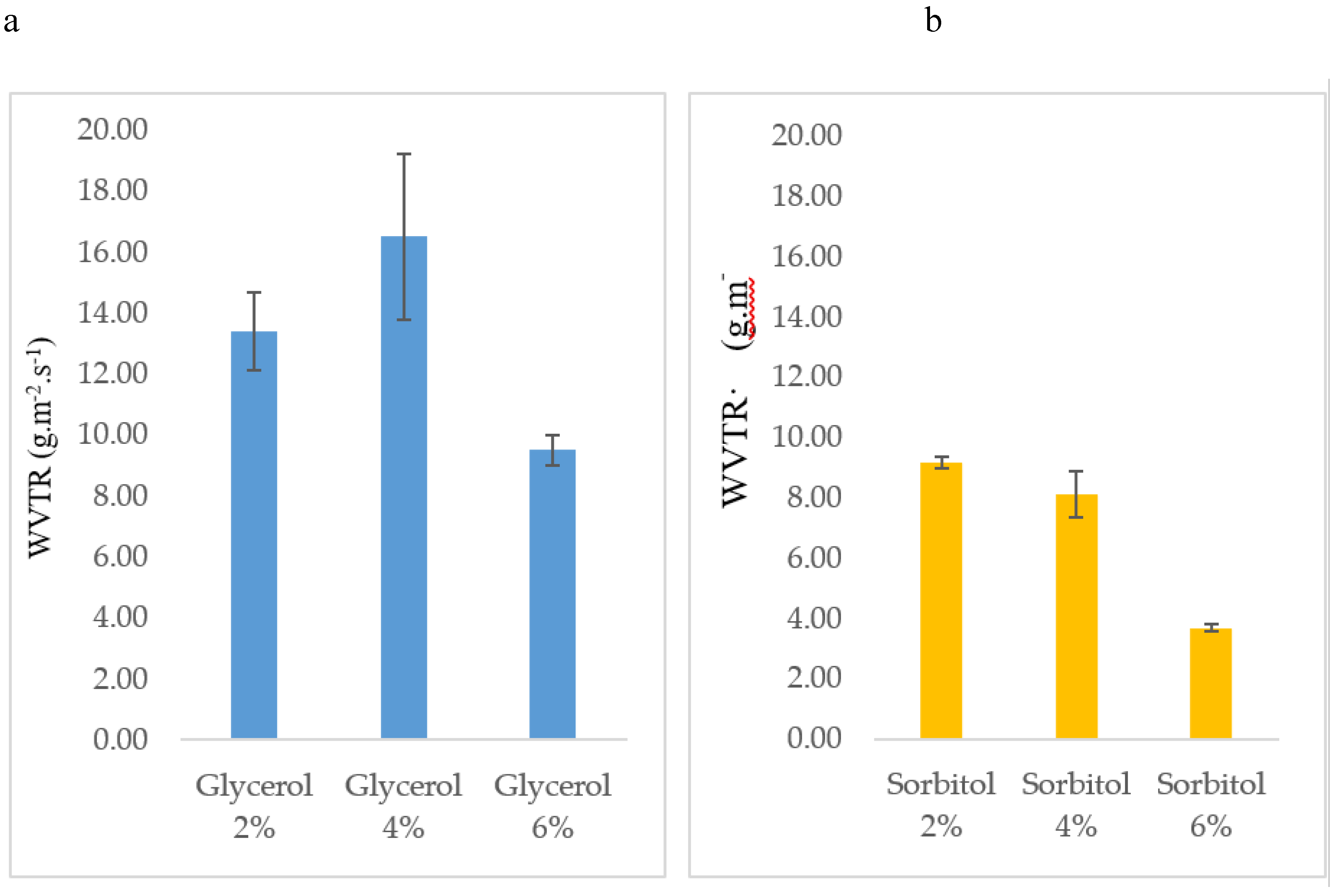

3.5. Water Vapor Transmission Rate

3.6. Transparency

3.7. FTIR Spectroscopy

3.8. Microstructure of Edible Films

3.9. Principle Component Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Puscaselu R, Gutt G, Amariei S. The use of edible films based on sodium alginate in meat product packaging: An eco-friendly alternative to conventional plastic materials. Coatings 2020;10. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Liu C, Sun J, Lv S. Bioactive Edible Sodium Alginate Films Incorporated with 2022.

- Yuan Y, Wang H, Fu Y, Chang C, Wu J. Sodium alginate/gum arabic/glycerol multicomponent edible films loaded with natamycin: Study on physicochemical, antibacterial, and sweet potatoes preservation properties. Int J Biol Macromol 2022;213:1068–77. [CrossRef]

- Fan Y, Yang J, Duan A, Li X. Pectin/sodium alginate/xanthan gum edible composite films as the fresh-cut package. Int J Biol Macromol 2021;181:1003–9. [CrossRef]

- Dursun Capar T. Characterization of sodium alginate-based biodegradable edible film incorporated with Vitis vinifera leaf extract: Nano-scaled by ultrasound-assisted technology. Food Packag Shelf Life 2023;37:101068. [CrossRef]

- Gopi S, Amalraj A, Kalarikkal N, Zhang J, Thomas S. Materials Science & Engineering C Preparation and characterization of nanocomposite films based on gum arabic , maltodextrin and polyethylene glycol reinforced with turmeric nanofiber isolated from turmeric spent. Mater Sci Eng C 2019;97:723–9. [CrossRef]

- Xu T, Gao C, Feng X, Yang Y, Shen X, Tang X. Structure, physical and antioxidant properties of chitosan-gum arabic edible films incorporated with cinnamon essential oil. Int J Biol Macromol 2019;134:230–6. [CrossRef]

- Kawhena TG, Opara UL, Fawole OA. Optimization of gum arabic and starch-based edible coatings with lemongrass oil using response surface methodology for improving postharvest quality of whole “wonderful” pomegranate fruit. Coatings 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Jiang H, Wang F, Ma R, Tian Y. Advances in gum Arabic utilization for sustainable applications as food packaging: Reinforcement strategies and applications in food preservation. Trends Food Sci Technol 2023;142:104215. [CrossRef]

- Tahsiri Z, Mirzaei H, Hosseini SMH, Khalesi M. Gum arabic improves the mechanical properties of wild almond protein film. Carbohydr Polym 2019;222:114994. [CrossRef]

- Seididamyeh M, Mantilla SMO, Netzel ME, Mereddy R, Sultanbawa Y. Gum Arabic edible coating embedded aqueous plant extracts: Interactive effects of partaking components and its effectiveness on cold storage of fresh-cut capsicum. Food Control 2024;159:110267. [CrossRef]

- Erben M, Pérez AA, Osella CA, Alvarez VA, Santiago LG. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules Impact of gum arabic and sodium alginate and their interactions with whey protein aggregates on bio-based fi lms characteristics. Int J Biol Macromol 2019;125:999–1007. [CrossRef]

- Dong J, Yu D, Yu Z, Zhang L, Xia W. Thermally-induced crosslinking altering the properties of chitosan films: Structure, physicochemical characteristics and antioxidant activity. Food Packag Shelf Life 2022;34:100948. [CrossRef]

- Tanada-Palmu PS, Grosso CRF. Effect of edible wheat gluten-based films and coatings on refrigerated strawberry (Fragaria ananassa) quality. Postharvest Biol Technol 2005;36:199–208. [CrossRef]

- Najafian N, Aarabi A, Nezamzadeh-ejhieh A. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules Evaluation of physicomechanical properties of gluten-based film incorporated with Persian gum and Guar gum. Int J Biol Macromol 2022;223:1257–67. [CrossRef]

- Hu F, Song Y, Thakur K, Zhang J, Rizwan M. Blueberry anthocyanin based active intelligent wheat gluten protein films : Preparation , characterization , and applications for shrimp freshness monitoring. Food Chem 2024;453:139676. [CrossRef]

- Sothornvit R, Krochta JM. Plasticizers in edible films and coatings. Innov Food Packag 2005:403–33. [CrossRef]

- Cao L, Liu W, Wang L. Developing a green and edible film from Cassia gum: The effects of glycerol and sorbitol. J Clean Prod 2018;175:276–82. [CrossRef]

- Farhan A, Hani NM. Characterization of edible packaging films based on semi-refined kappa-carrageenan plasticized with glycerol and sorbitol. Food Hydrocoll 2017;64:48–58. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Li Y, Ma Z, Rao Z, Zheng X, Tang K, et al. Effect of polyol plasticizers on properties and microstructure of soluble soybean polysaccharide edible films. Food Packag Shelf Life 2023;35:101023. [CrossRef]

- Sharma N, Khatkar BS, Kaushik R, Sharma P, Sharma R. Isolation and development of wheat based gluten edible film and its physicochemical properties. Int Food Res J 2017;24:94–101.

- Silva OA, Pellá MG, Pellá MG, Caetano J, Simões MR, Bittencourt PRS, et al. Synthesis and characterization of a low solubility edible film based on native cassava starch. Int J Biol Macromol 2019;128:290–6. [CrossRef]

- Ríos-De-benito LF, Escamilla-García M, García-Almendárez B, Amaro-Reyes A, Di Pierro P, Regalado-González C. Design of an active edible coating based on sodium caseinate, chitosan and oregano essential oil reinforced with silica particles and its application on panela cheese. Coatings 2021;11. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Auty MAE, Kerry JP. Physical assessment of composite biodegradable films manufactured using whey protein isolate, gelatin and sodium alginate. J Food Eng 2010;96:199–207. [CrossRef]

- Dick M, Costa TMH, Gomaa A, Subirade M, Rios ADO, Flôres SH. Edible film production from chia seed mucilage: Effect of glycerol concentration on its physicochemical and mechanical properties. Carbohydr Polym 2015;130:198–205. [CrossRef]

- Paidari S, Zamindar N, Tahergorabi R, Kargar M, Ezzati S, Shirani N, et al. Edible coating and films as promising packaging: a mini review. J Food Meas Charact 2021;15:4205–14. [CrossRef]

- Huber KC, Embuscado ME, editors. Edible Films and Coatings for Food Applications. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2009. [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Mártinez L, Pérez-Cervera C, Andrade-Pizarro R. Effect of glycerol and sorbitol concentrations on mechanical, optical, and barrier properties of sweet potato starch film. NFS J 2020;20:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins EJ, Chang C, Lam RSH, Nickerson MT. Effects of fl axseed oil concentration on the performance of a soy protein isolate-based emulsion-type fi lm. FRIN 2015;67:418–25. [CrossRef]

- Jaderi Z, Tabatabaee F, Seyed Y, Mortazavi A, Koocheki A. Effects of glycerol and sorbitol on a novel biodegradable edible film based on Malva sylvestris flower gum 2023:991–1000. [CrossRef]

- Paudel S, Regmi S, Janaswamy S. Effect of glycerol and sorbitol on cellulose-based biodegradable films. Food Packag Shelf Life 2023;37:101090. [CrossRef]

- Wang B, Xu X, Fang Y, Yan S, Cui B, Abd El-Aty AM. Effect of Different Ratios of Glycerol and Erythritol on Properties of Corn Starch-Based Films. Front Nutr 2022;9:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Nehra A, Biswas D, Siracusa V, Roy S. Natural Gum-Based Functional Bioactive Films and Coatings: A Review. Int J Mol Sci 2022;24:485. [CrossRef]

- Sartori T, Feltre G, do Amaral Sobral PJ, Lopes da Cunha R, Menegalli FC. Properties of films produced from blends of pectin and gluten. Food Packag Shelf Life 2018;18:221–9. [CrossRef]

- Faust S, Foerster J, Lindner M, Schmid M. Effect of glycerol and sorbitol on the mechanical and barrier properties of films based on pea protein isolate produced by high-moisture extrusion processing 2022:95–102. [CrossRef]

- Ikmar M, Mohamad N, Sarbon NM. Effect of sorbitol at different concentrations on the functional properties of gelatin / carboxymethyl cellulose ( CMC )/ chitosan composite films Effect of sorbitol at different concentrations on the functional properties of gelatin / carboxymethyl cellu 2020.

- Fakhouri FM, Martelli SM, Caon T, Velasco JI, Mei LHI. Edible films and coatings based on starch/gelatin: Film properties and effect of coatings on quality of refrigerated Red Crimson grapes. Postharvest Biol Technol 2015;109:57–64. [CrossRef]

- Seyedi S, Koocheki A, Mohebbi M, Zahedi Y. Lepidium perfoliatum seed gum: A new source of carbohydrate to make a biodegradable film. Carbohydr Polym 2014;101:349–58. [CrossRef]

- GONTARD N, DUCHEZ C, CUQ J -L, GUILBERT S. Edible composite films of wheat gluten and lipids: water vapour permeability and other physical properties. Int J Food Sci Technol 1994;29:39–50. [CrossRef]

- Pourfarzad A, Ahmadian Z. Interactions between polyols and wheat biopolymers in a bread model system forti fi ed with inulin : A Fourier transform infrared study 2018. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hassan AA. Development and characterization of camel gelatin films: Influence of camel bone age and glycerol or sorbitol on film properties. Heliyon 2024;10:e30338. [CrossRef]

- Dong M, Tian L, Li J, Jia J, Dong Y, Tu Y, et al. Improving physicochemical properties of edible wheat gluten protein films with proteins, polysaccharides and organic acid. Lwt 2022;154:112868. [CrossRef]

- Khashayary S, Aarabi A. Evaluation of Physico-mechanical and Antifungal Properties Of Gluten-based Film Incorporated with Vanillin, Salicylic Acid, and Montmorillonite (Cloisite 15A). Food Bioprocess Technol 2021;14:665–78. [CrossRef]

| Samples | Thickness (mm) | Color | ||

| L* | a* | b* | ||

| Glycerol | ||||

| Glycerol 2% | 0.14±0.01a | 58.66±0.64a | -5.36±0.20a | 11.11±1.26a |

| Glycerol 4% | 0.17±0.02a | 57.98±0.41a | -6.24±0.72a | 7.66±3.41b |

| Glycerol 6% | 0.17±0.02a | 59.98±4.30a | -6.42±0.38a | 8.62±1.30a |

| Sorbitol | ||||

| Sorbitol 2% | 0.14±0.01a | 60.37±0.72a | -6.67±0.15a | 8.84±0.29a |

| Sorbitol 4% | 0.15±0.01a | 59.27±0.69a | -4.51±0.42b | 14.96±1.52b |

| Sorbitol 6% | 0.17±0.01a | 59.33±0.42a | -7.01±0.27a | 9.19±0.43a |

| Samples | Tensile strength (MPa) | Transparency |

| Glycerol | ||

| Glycerol 2% | 0.10±0.00a | 17.85±1.07a |

| Glycerol 4% | 0.01±0.01b | 13.58±0.73b |

| Glycerol 6% | 0.01±0.00b | 6.39±0.35c |

| Sorbitol | ||

| Sorbitol 2% | 0.13±0.07a | 20.89±2.57a |

| Sorbitol 4% | 0.07±0.03a | 13.61±0.81b |

| Sorbitol 6% | 0.02±0.01b | 13.91±0.83b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).