Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Related Works

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Description

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

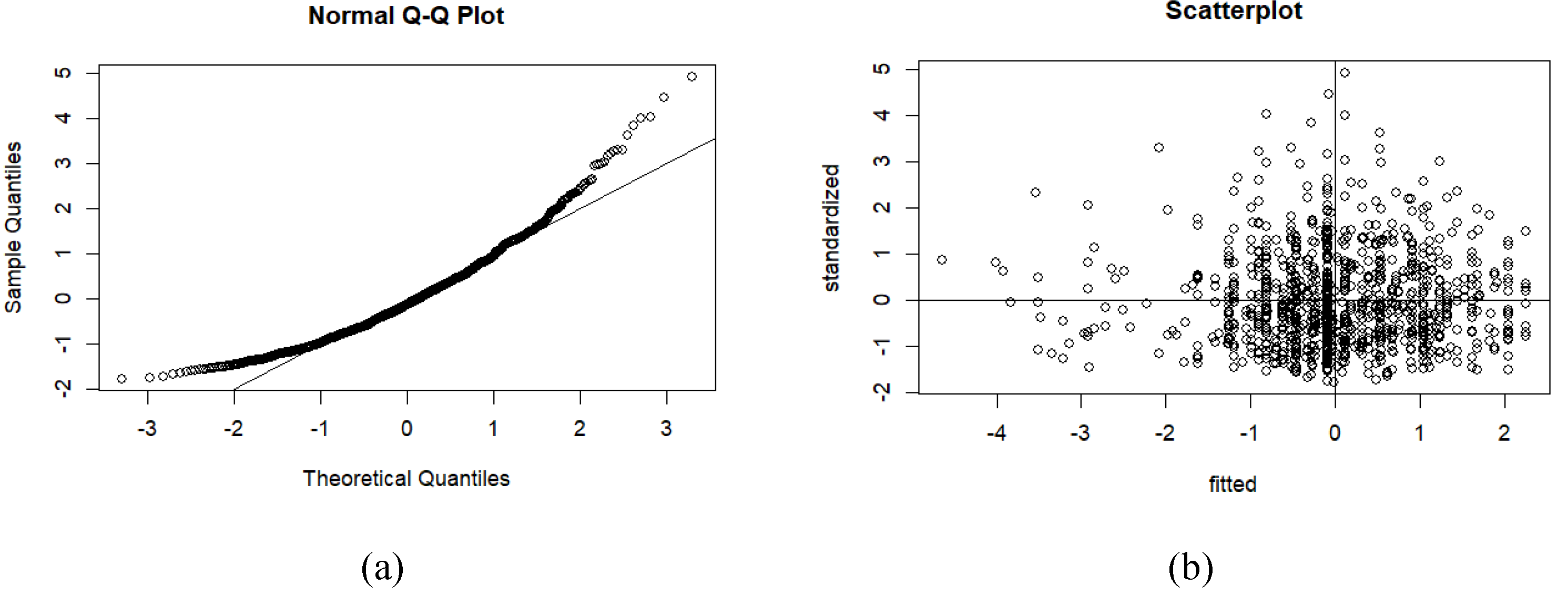

3.1. Data Treatment

3.2. Tests for Differences

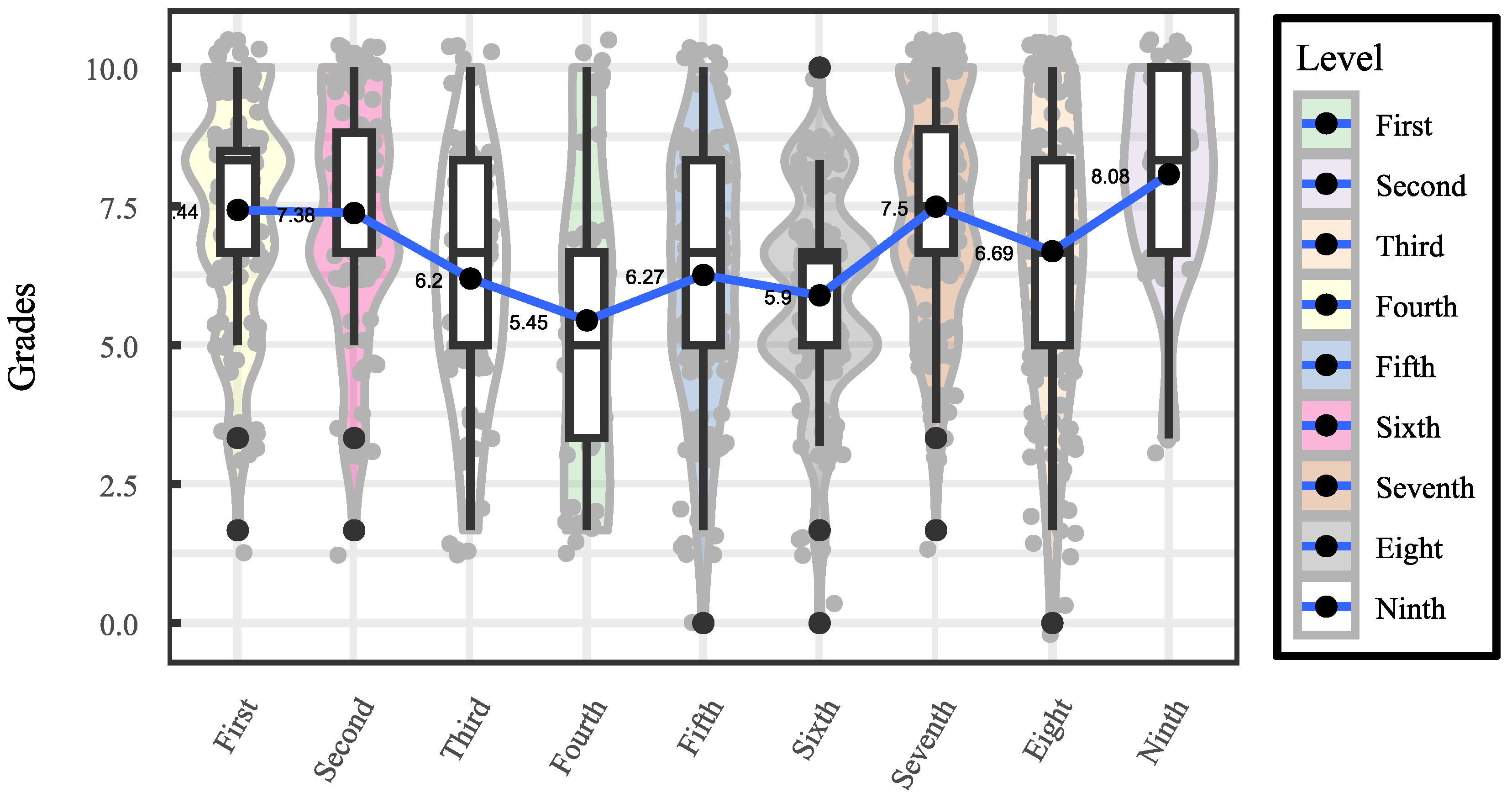

3.2.1. Diferences by Level

| Kruskal-Wallis Test – Qualification ~ Subjects | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kruskal Wallis χ2 | 95.304 | Degrees of freedom | 8 | p-value | 2.2e − 16 Significant |

||||||||

| Paired Test – Dunn- Šidák | |||||||||||||

| Fouth | Nineth | Eighth | First | Fifth | Second | Seventh | Sixth | ||||||

| Ninth |

pval = 0.00062 Significant |

||||||||||||

| Eighth |

pval = 0.31649 Not significant |

pval = 0.02063 Significant |

|||||||||||

| First |

pval = 0.00282 Significant |

pval = 1.00000 Not significant |

pval = 0.42292 Not significant |

||||||||||

| Fifth |

pval = 1.00000 Not significant |

pval = 3.5e − 05 Significant |

pval = 1.00000 Not significant |

pval = 0.00037 Significant |

|||||||||

| Second |

pval = 0.00849 Significant |

pval = 1.00000 Not significant |

pval = 1.00000 Significant |

pval = 1.00000 Significant |

pval = 0.00328 Significant |

||||||||

| Seventh |

pval = 0.00099 Significant |

pval = 1.00000 Not significant |

pval = 0.17073 Not significant |

pval = 1.00000 Significant |

pval = 4.7e − 05 Significant |

pval = 1.00000 Not significant |

|||||||

| Sixth |

pval = 1.00000 Not significant |

pval = 2.4e − 08 Significant |

pval = 0.03490 Significant |

pval = 1.6e − 07 Significant |

pval = 1.00000 Not significant |

pval = 3.5e − 06 Significant |

pval = 5.7e − 09 Significant |

||||||

| Third |

pval = 1.00000 Not significant |

pval = 6.2e − 05 Not significant |

pval = 1.00000 Not significant |

pval = 0.00134 Significant |

pval = 1.00000 Not significant |

pval = 0.00776 Significant |

pval = 0.00043 Significant |

pval = 1.00000 Not significant |

|||||

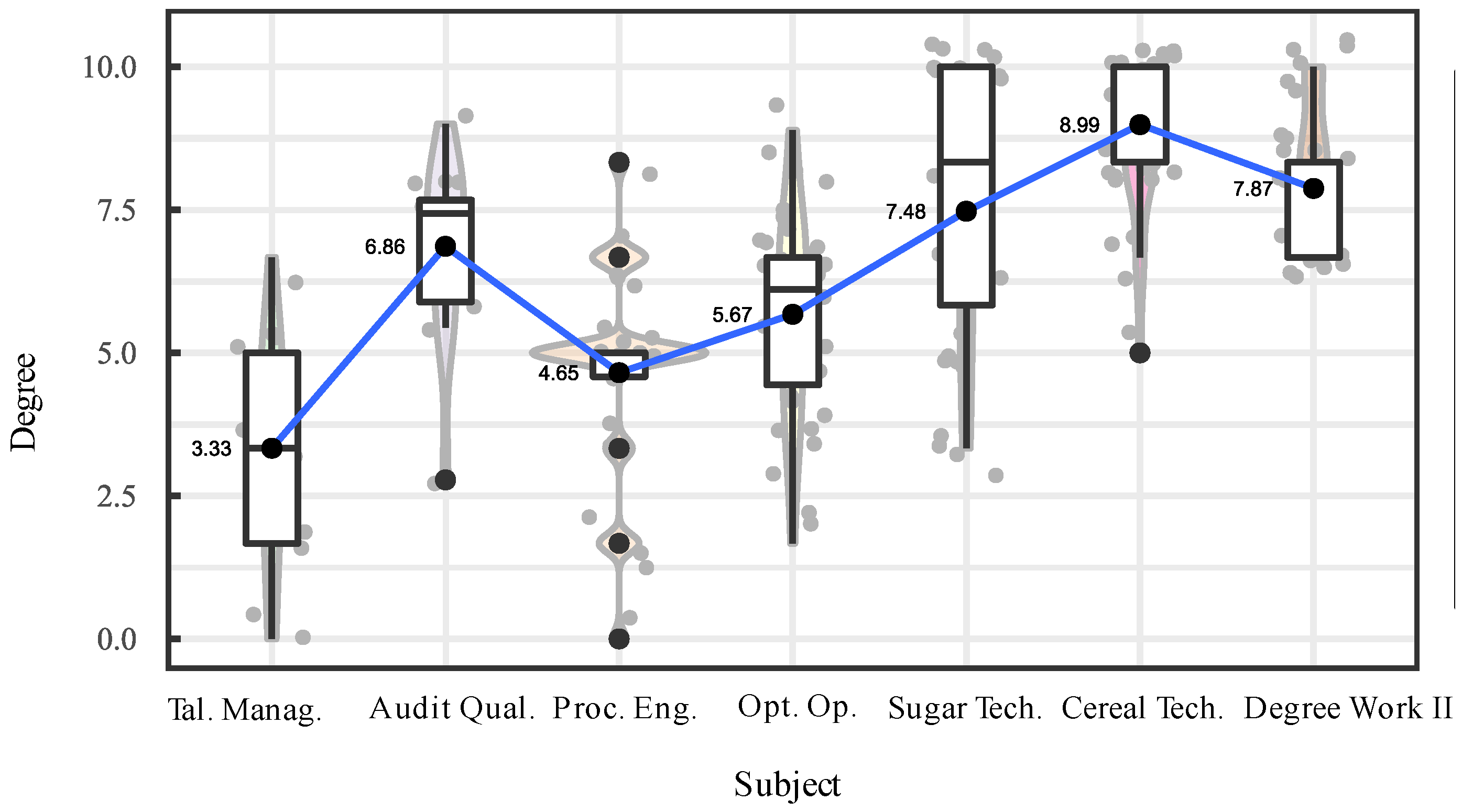

3.2.2. Differences by Subject

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- A. E. Jácome Ortega, J. A. Caraguay Procel, E. P. Herrera-Granda, and I. D. Herrera Granda, “Confirmatory Factorial Analysis Applied on Teacher Evaluation Processes in Higher Education Institutions of Ecuador,” in Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Springer, 2020, pp. 157–170. [CrossRef]

- A. E. Jácome-Ortega, E. P. Herrera-Granda, I. D. Herrera-Granda, J. A. Caraguay-Procel, and A. V. Basantes-Andrade, “Análisis temporal y pronóstico del uso de las TIC, a partir del instrumento de evaluación docente de una Institución de Educación Superior,” Rev. Ibérica Sist. e Tecnol. Informação, vol. 2019, no. E22, pp. 399–412, 2019, [Online]. Available: https://www.proquest.com/openview/96910c7cb0c260ae2409940921c7f71b/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=1006393.

- C. P. Guevara-Vega, W. P. Chamorro-Ortega, E. P. Herrera-Granda, I. D. García-Santillán, and J. A. Quiña-Mera, “Incidence of a web application implementation for high school students learning evaluation: A case study,” Rev. Ibérica Sist. e Tecnol. Informação, vol. 2020, no. E32, pp. 509–523, 2020, [Online]. Available: https://www.proquest.com/openview/bfe21dc96eab6a1dd96d132373a9eefc/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=1006393.

- L. Meng, M. A. Muñoz, and D. Wu, “Teachers’ perceptions of effective teaching: a theory-based exploratory study of teachers from China,” Educ. Psychol., vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 461–480, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Huerta Rosales, “Evaluación basada en evidencias, un nuevo enfoque de evaluación por competencias,” Rev. Investig. la Univ. Le Cordon Bleu, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 159–171, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Zapata, P. Leihy, D. Theurillat, G. Zapata, P. Leihy, and D. Theurillat, “Compromiso estudiantil en educación superior: adaptación y validación de un cuestionario de evaluación en universidades chilenas,” Calid. en la Educ., no. 48, pp. 204–250, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Rodríguez and D. Díaz, “Análisis de resultados de futuros profesores de matemática en los contenidos estadísticos y probabilísticos de la evaluación nacional diagnóstica,” PARADIGMA, pp. 142–164, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Pedraza, “Satisfacción laboral y compromiso organizacional del capital humano en el desempeño en instituciones de educación superior,” RIDE. Rev. Iberoam. para la Investig. y el Desarro. Educ., vol. 10, no. 20, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. G. Pérez Ibarra, J. R. Quispe, F. F. Mullicundo, and D. A. Lamas, “Aplicación de la herramienta Quizizz como estrategia de gamificación en la educación superior,” XXIII Work. Investig. en Ciencias la Comput. (WICC 2021, Chilecito, La Rioja), no. August 2021, pp. 963–968, 2021.

- N. Arias, W. U. Rincón, and J. M. Cruz, “Diferencia de logro geolocalizado en educación presencial y a distancia en Colombia,” Rev. electrónica Investig. Educ., vol. 23, pp. 1–22, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Valverde and B. Solis, “Estrategias de enseñanza virtual en la educación superior,” Polo del Conoc., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 1110–1132, Jan. 2021.

- E. E. Mancha, M. D. Casa, M. Yana, D. Mamani, and P. S. Mamani, “Competencias digitales y satisfacción en logros de aprendizaje de estudiantes universitarios en tiempos de Covid-19,” Comuni@cción, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 106–116, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. N. Ventosilla, H. R. Santa María, F. Ostos De La Cruz, and A. M. Flores, “Aula invertida como herramienta para el logro de aprendizaje autónomo en estudiantes universitarios,” Propósitos y Represent., vol. 9, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Ghorbani, “MAHALANOBIS DISTANCE AND ITS APPLICATION FOR DETECTING MULTIVARIATE OUTLIERS,” FACTA Univ. Ser. Math. INFORMATICS, vol. 34, pp. 583–595, 2019. [CrossRef]

- F. Nwobi and F. Akanno, “Power comparison of ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests when error assumptions are violated,” Adv. Methodol. Stat. / Metod. Zv., vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 53–71, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Chamorro-Hernandez, E. P. Herrera-Granda, and C. Rivas-Rosero, “Selection of the Processing Method for Green Banana Chips from Barraganete and Dominico Varieties Using Multivariate Techniques,” Appl. Sci., vol. 14, no. 7, p. 2682, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- O. J. Dunn, “Estimation of the Means of Dependent Variables,” Ann. Math. Stat., vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 1095–1111, Feb. 1958, [Online]. Available: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2236948.

| First Level | Second Level | Third Level | Fourth Level | Fifth Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Subject | Code | Subject | Code | Subject | Code | Subject | Code | Subject |

| A11 | Linear Algebra | A21 | Applied Physics | A31 | Food Biochemistry | A41 | Instrumental analysis | A51 | Bromatology |

| À12 | Biology | A22 | General Microbiology | A32 | Engineering Fundamentals | A42 | Food Biotechnology | A52 | Experimental Design |

| A13 | General Chemistry | A23 | Nutrition | A33 | Food Microbiology | A43 | Inferential statistics | A53 | Standardization and Quality Assurance |

| A24 | Organic Chemistry | A34 | Toxicology | A44 | Transportation Phenomena | A54 | Rheology | ||

| A45 | Basic Thermodynamics | A55 | Applied Thermodynamics | ||||||

| Sixth Level | Seventh Level | Eight Level | Ninth Level | ||||||

| Code | Subject | Code | Subject | Code | Subject | Code | Subject | ||

| A61 | Food Safety and Management Systems | A71 | Project Design and Evaluation | A81 | Human Talent Management | A91 | Design and Organization of Industrial Plants | ||

| A62 | Development of New Products | A72 | Sensory Evaluation | A82 | Audit of Quality and Safety Systems | A92 | Degree Work III | ||

| A63 | Containers and Packaging | A73 | Unit Operations II | A83 | Process and Food Engineering | ||||

| A64 | Unit Operations | A74 | Integrated Management Systems | A84 | Optimization of Processes and Operations | ||||

| A65 | Dairy Technology | A75 | Fruit and Vegetable Technology | A85 | Sugar Technology | ||||

| A76 | Meat Products Technology | A86 | Cereal Technology | ||||||

| A77 | Degree Work I | A87 | Degree Work II | ||||||

| Mean | 6,810 | Variance | 4,980 | Maximum | 10,000 |

| Median | 6,670 | Standard Deviation | 2,230 | Q3 | 8,330 |

| Mode | 6,670 | Range | 10,000 | Median | 6,670 |

| Trimmed mean | 6.91 | Interquartile range | 3,330 | Q1 | 5,000 |

| Bias | -0.45 | Coeff . of variation | 32,770 | 5% quantile | 3,330 |

| Kurtosis | -0.30 | Standard error | 0.070 | Minimum | 0.000 |

| Level | Mean | Median | Mode | Trimmed mean | Std. deviation | Coeff. of variation | Bias | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 7.44 | 8.33 | 8.33 | 7.33 | 2.00 | 26.91 | -0.60 | -0.27 |

| Second | 7.38 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 7.47 | 2.07 | 28.06 | -0.54 | -0.31 |

| Third | 6.20 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 6.24 | 2.13 | 34.40 | -0.25 | -0.42 |

| Room | 5.45 | 5.00 | 6.67 | 5.41 | 2.91 | 53.43 | 0.19 | -1.16 |

| Fifth | 6.27 | 6.67 | 8.33 | 6.32 | 2.20 | 35.06 | -0.36 | -0.39 |

| Sixth | 5.90 | 6.53 | 5.00 | 5.99 | 1.83 | 30.94 | -0.46 | 0.23 |

| Seventh | 7.50 | 7.50 | 10 | 7.59 | 1.94 | 25.92 | -0.35 | -0.56 |

| Eighth | 6.69 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 6.82 | 2.48 | 37.03 | -0.47 | -0.36 |

| Ninth | 8.08 | 8.33 | 8.33 | 8.22 | 1.80 | 22.31 | -1.05 | 1.21 |

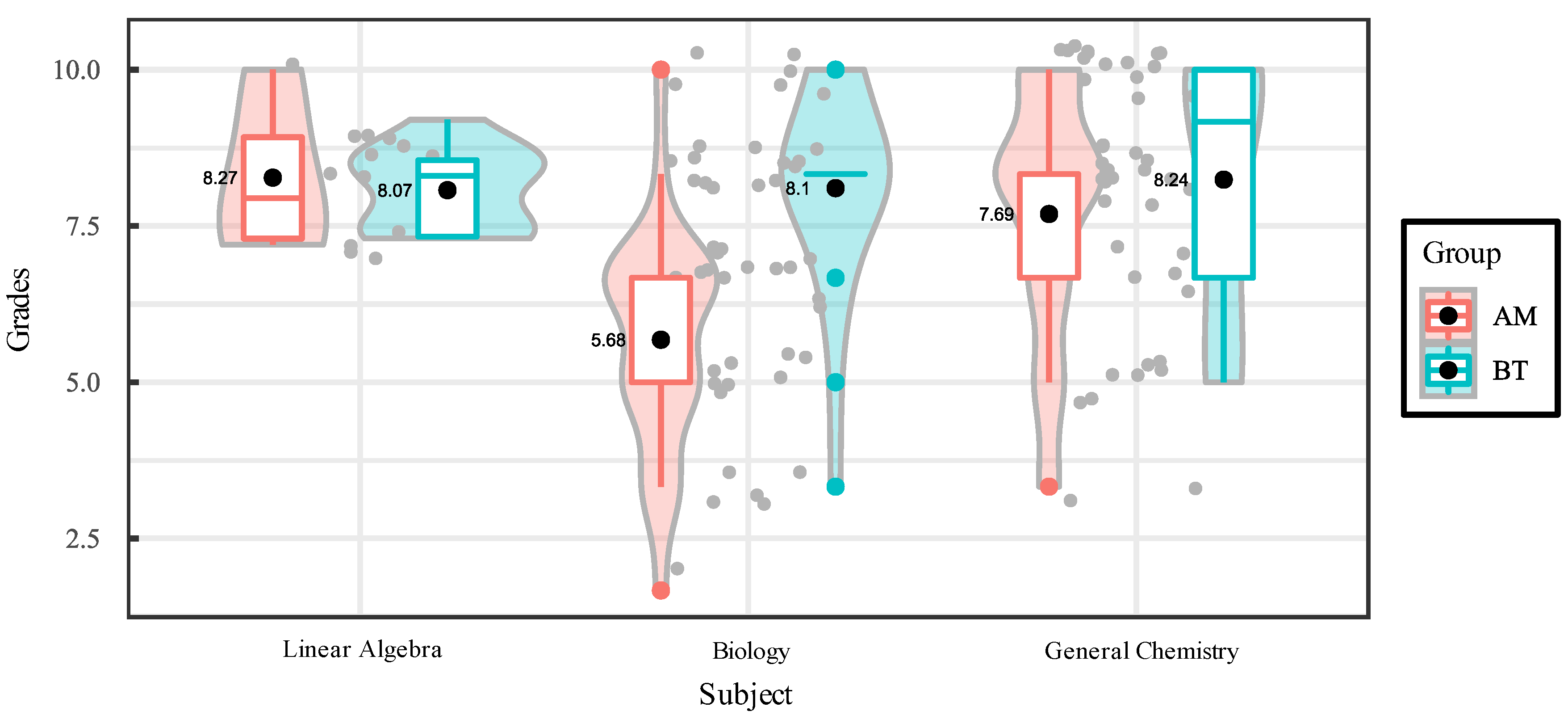

| Kruskal-Wallis Test – Qualification ~ Subjects | |||||

| Kruskal Wallis χ2 | 11.081 | Degrees of freedom | 2 | p-value | 0.003925 Significant |

| Pairwise Dunn- Šidák Test | |||||

| Linear algebra | Biology | ||||

| Biology |

pval = 0.009 Significant |

||||

| General Chemistry |

pval = 1.000 Not significant |

|

|||

| Subject | Mean | Median | Mode | Trimmed mean | Std. deviation | Coeff. of variation | Bias | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Algebra | 8.12 | 8.30 | 7.33 | 8.12 | 0.80 | 9.91 | 0.67 | 0.03 |

| Biology | 6.77 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 6.81 | 2.08 | 30.74 | -0.32 | -0.43 |

| General Chemistry | 7.92 | 8.33 | 10 | 8.04 | 2.04 | 25.73 | -0.70 | -0.60 |

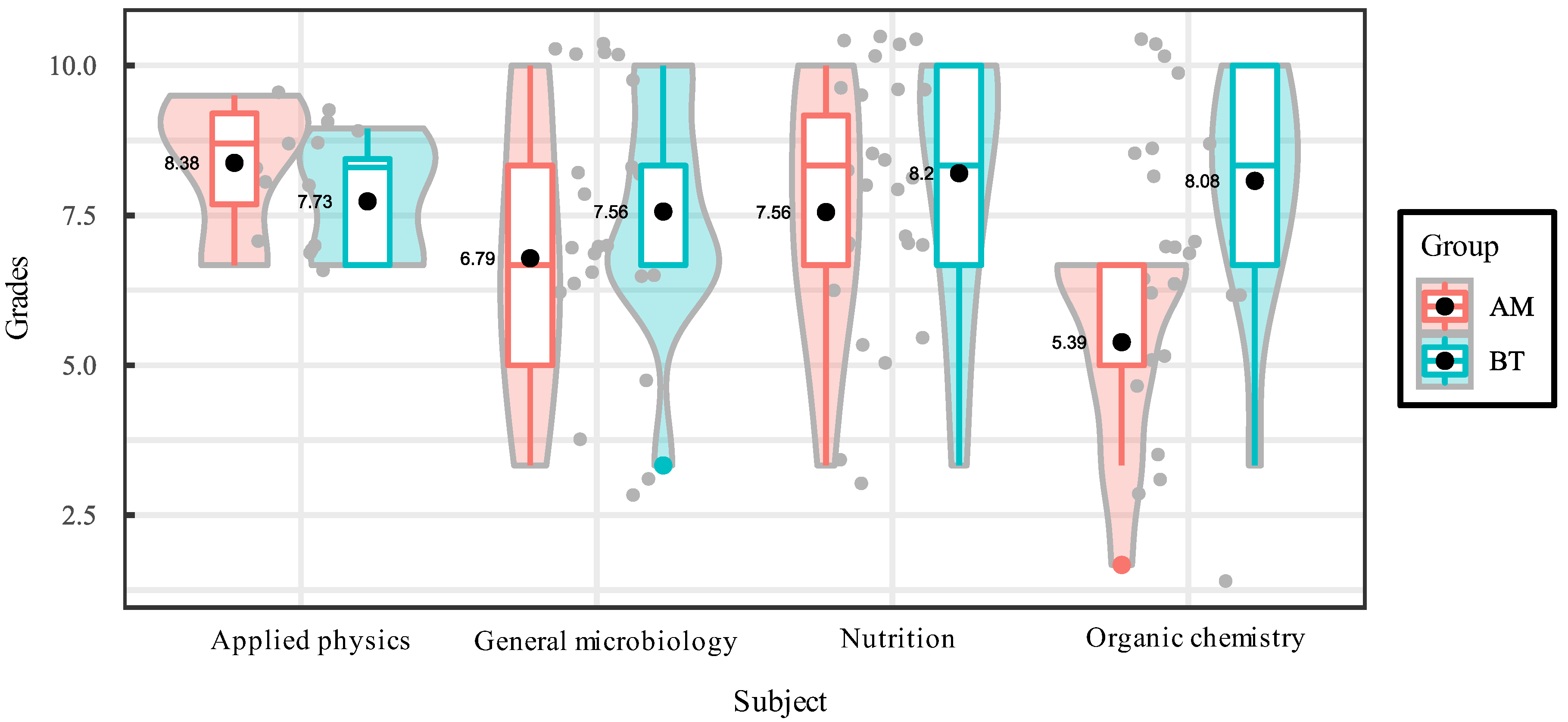

| Kruskal-Wallis Test – Qualification ~ Subjects | |||||

| Kruskal Wallis χ2 | 5.5123 | Degrees of freedom | 3 | p-value | 0.1304 Note significant |

| Pairwise Dunn- Šidák Test | |||||

| Applied Physic | General Microbiology | Nutrition | |||

| General Microbiology |

|

||||

| Nutrition |

|

|

|||

| Organic Chemistry |

|

|

|

||

| Subject | Mean | Median | Mode | Trimmed mean | Std. deviation | Coeff. of variation | Bias | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applied Physic | 8.06 | 8.44 | 6.67 | 8.06 | 1.12 | 13.91 | -0.38 | -1.72 |

| General Microbiology | 7.16 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 7.20 | 2.11 | 29.45 | -0.24 | -0.66 |

| Nutrition | 7.86 | 8.33 | 10.00 | 7.95 | 2.12 | 26.99 | -0.70 | -0.48 |

| Organic Chemistry | 6.73 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 6.81 | 2.23 | 33.20 | -0.40 | -0.19 |

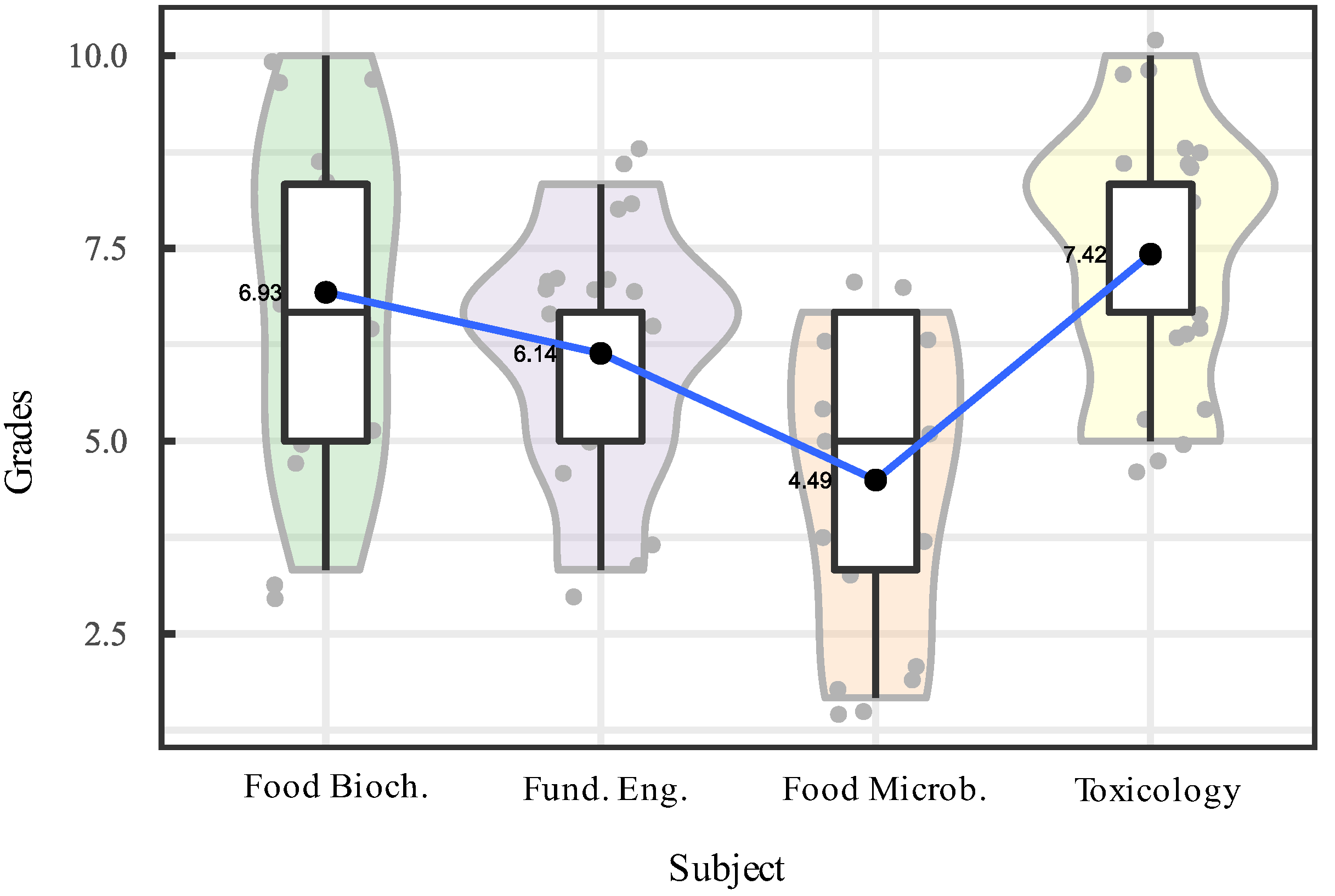

| Kruskal-Wallis Test – Qualification ~ Subjects | |||||

| Kruskal Wallis | Degrees of freedom | 3 | p-value | 5.581e-05 |

|

| Pairwise Dunn-Šidák Test | |||||

| Food Biochemistry | Engineering Fundamentals | Food Microbiology | |||

| Engineering Fundamentals |

|

||||

| Food Microbiology |

|

|

|||

| Toxicology |

|

|

|

||

| Subject | Mean | Median | Mode | Trimmed mean | Std. deviation | Coeff. of variation | Bias | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Biochemistry | 6.93 | 6.67 | 8.33 | 6.93 | 2.17 | 31.32 | -0.16 | -1.14 |

| Engineering Fundamentals | 6.14 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 6.17 | 1.58 | 25.69 | -0.40 | -0.52 |

| Food Microbiology | 4.49 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 4.42 | 1.91 | 42.49 | -0.33 | -1.29 |

| Toxicology | 7.42 | 8.33 | 8.33 | 7.42 | 1.68 | 22.68 | -0.17 | -1.02 |

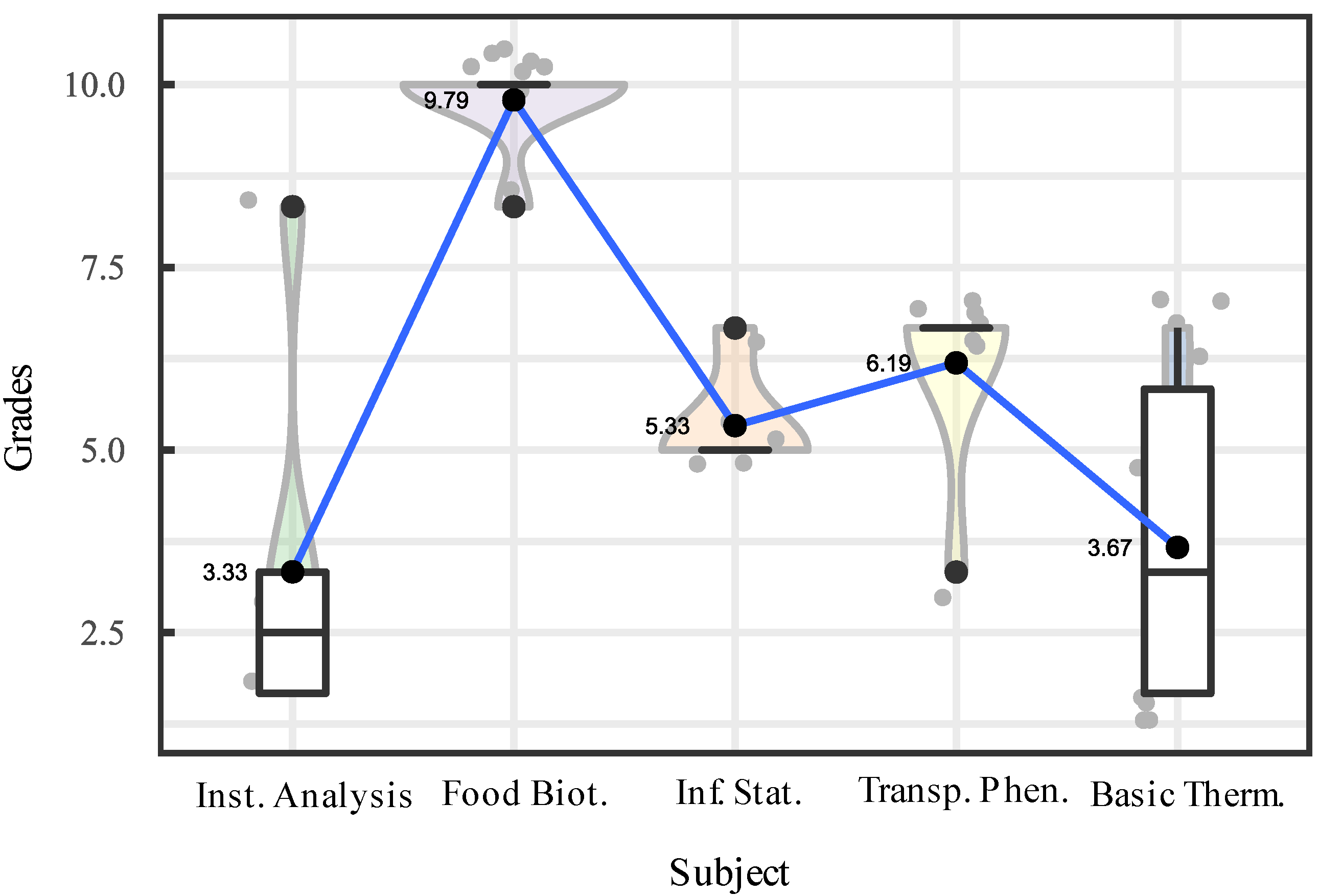

| Kruskal-Wallis Test – Qualification ~ Subjects | ||||||

| Kruskal Wallis | Degrees of freedom | 4 | p-value | 4.613e-05 | ||

| Later – Dunn- Šidák | ||||||

| Instrumental analysis | Food Biotechnology | Inferential Statistics | Transport Phenomena | |||

| Food Biotechnology |

|

|||||

| Inferential Statistics |

|

|

||||

| Transport Phenomena |

|

|

|

|||

| Basic Thermodynamics |

|

|

|

|

||

| Subject | Mean | Median | Mode | Trimmed mean | Std. deviation | Coeff. of variation | Bias | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrumental analysis | 3.33 | 2.50 | 1.67 | 3.33 | 2.58 | 77.38 | 1.94 | 3.97 |

| Food Biotechnology | 9.79 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 9.79 | 0.59 | 6.03 | -2.83 | 8.00 |

| Inferential Statistics | 5.33 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.33 | 0.75 | 14.00 | 2.24 | 5.00 |

| Transport Phenomena | 6.19 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 6.19 | 1.26 | 20.38 | -2.65 | 7.00 |

| Basic thermodynamics | 3.67 | 3.33 | 1.67 | 3.67 | 2.11 | 57.48 | 0.55 | -1.41 |

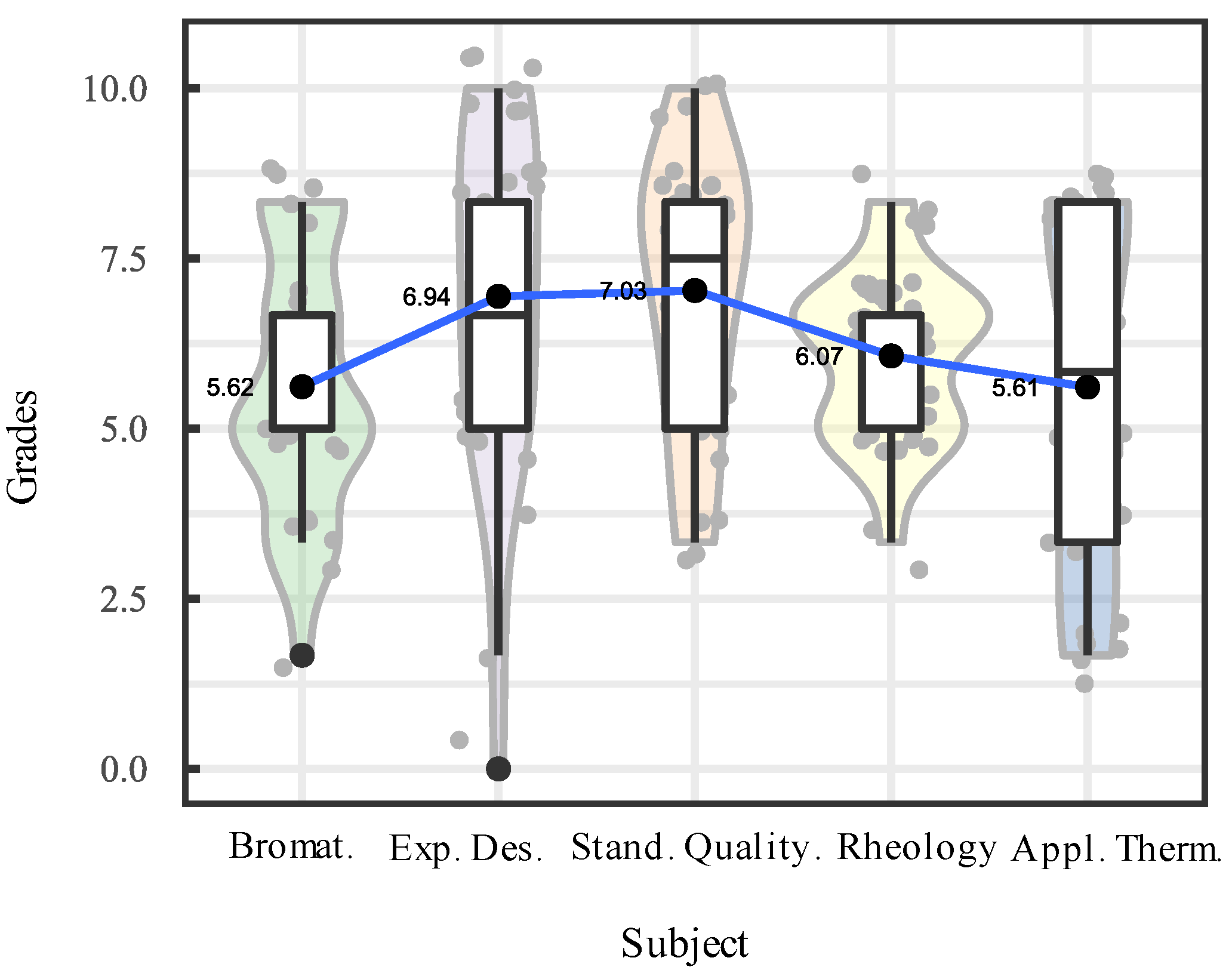

| Kruskal-Wallis Test – Qualification ~ Subjects | ||||||

| Kruskal Wallis | Degrees of freedom | 4 | p-value | 0.01684 | ||

| Posteriori – Dunn- Šidák test | ||||||

| Bromatology | Experimental design | Standardization and assurance of quality | Rheology | |||

| Experimental design |

|

|||||

| Standardization and quality assurance |

|

|

||||

| Rheology |

|

|

|

|||

| Applied Thermodynamics |

|

|

|

|

||

| Subject | Mean | Median | Mode | Trimmed mean | Std. deviation | Coeff. of variation | Bias | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bromatology | 5.62 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.67 | 1.91 | 34.08 | 0.01 | -0.81 |

| Experimental design | 6.94 | 6.67 | 5.00 | 7.08 | 2.59 | 37.32 | -0.77 | 0.43 |

| Standardization and assurance of quality | 7.03 | 7.50 | 8.33 | 7.05 | 2.06 | 29.33 | -0.45 | -0.76 |

| Rheology | 6.07 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 6.08 | 1.24 | 20.41 | -0.12 | -0.14 |

| Applied Thermodynamics | 5.61 | 5.84 | 8.33 | 5.65 | 2.75 | 48.99 | -0.29 | -1.63 |

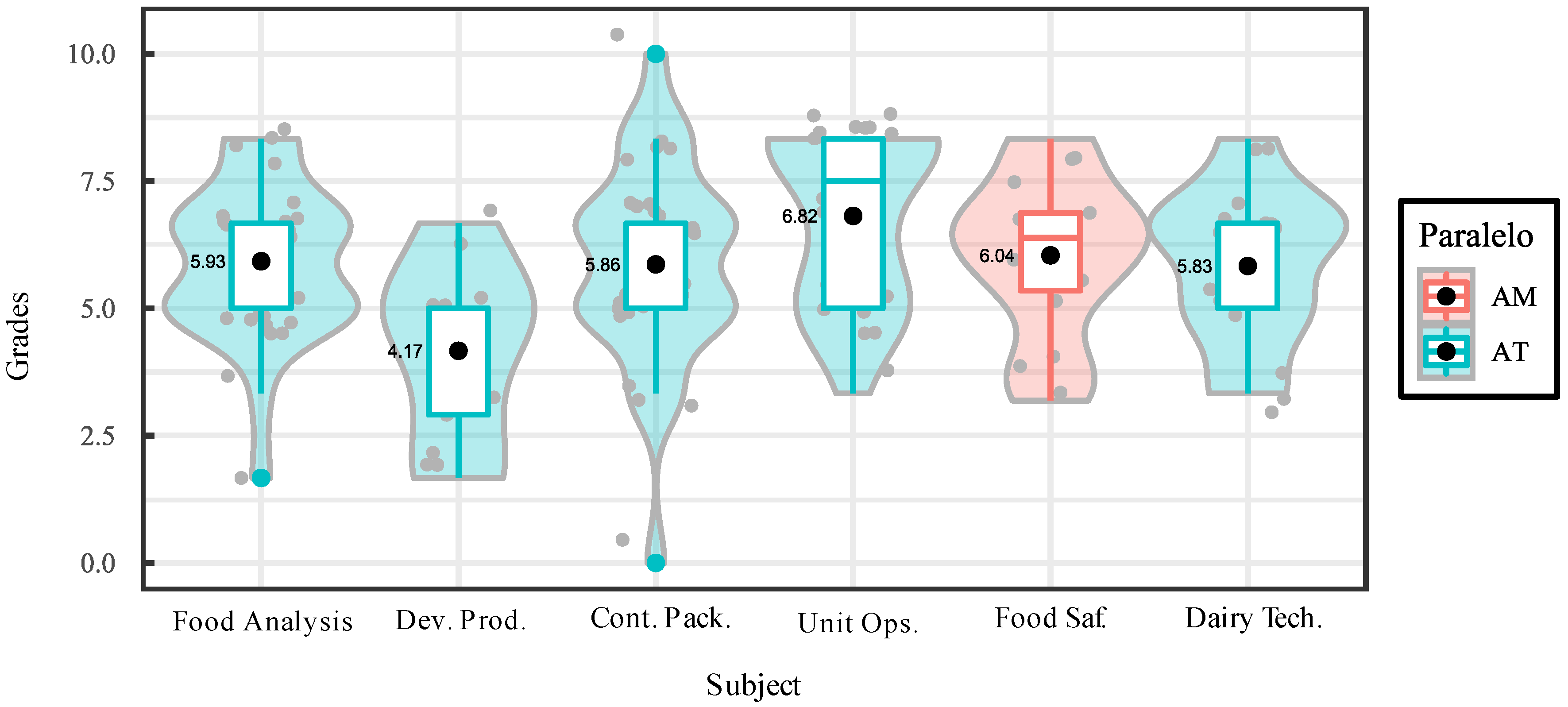

| Kruskal-Wallis Test – Qualification ~ Subjects | ||||||||||

| Kruskal Wallis χ2 | 14.474 | Degrees of freedom | 4 | p- value | 0.01286 Significant |

|||||

| Posteriori – Dunn- Šidák test | ||||||||||

| Food analysis | Development of new products | Containers and packaging | Unit Operations | Food safety systems | ||||||

| Development of new products |

|

|||||||||

| Containers and packaging |

|

|

||||||||

| Unit Operations |

|

|

|

|||||||

| Food safety systems |

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Dairy Technology |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Subject | Mean | Median | Mode | Trimmed mean | Std. deviation | Coeff. of variation | Bias | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food analysis | 5.93 | 6.67 | 5.00 | 6.00 | 1.56 | 26.25 | -0.48 | 0.91 |

| Development of new products | 4.17 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 4.17 | 1.81 | 43.47 | -0.25 | -1.13 |

| Containers and packaging | 5.86 | 6.67 | 5.00 | 5.93 | 2.03 | 34.70 | -0.60 | 1.58 |

| Unit Operations | 6.82 | 7.50 | 8.33 | 6.92 | 1.70 | 24.90 | -0.50 | -1.33 |

| Food safety systems | 6.04 | 6.39 | 6.39 | 6.04 | 1.62 | 26.76 | -0.42 | -0.56 |

| Dairy Technology | 5.83 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 5.83 | 1.54 | 26.40 | -0.26 | -0.61 |

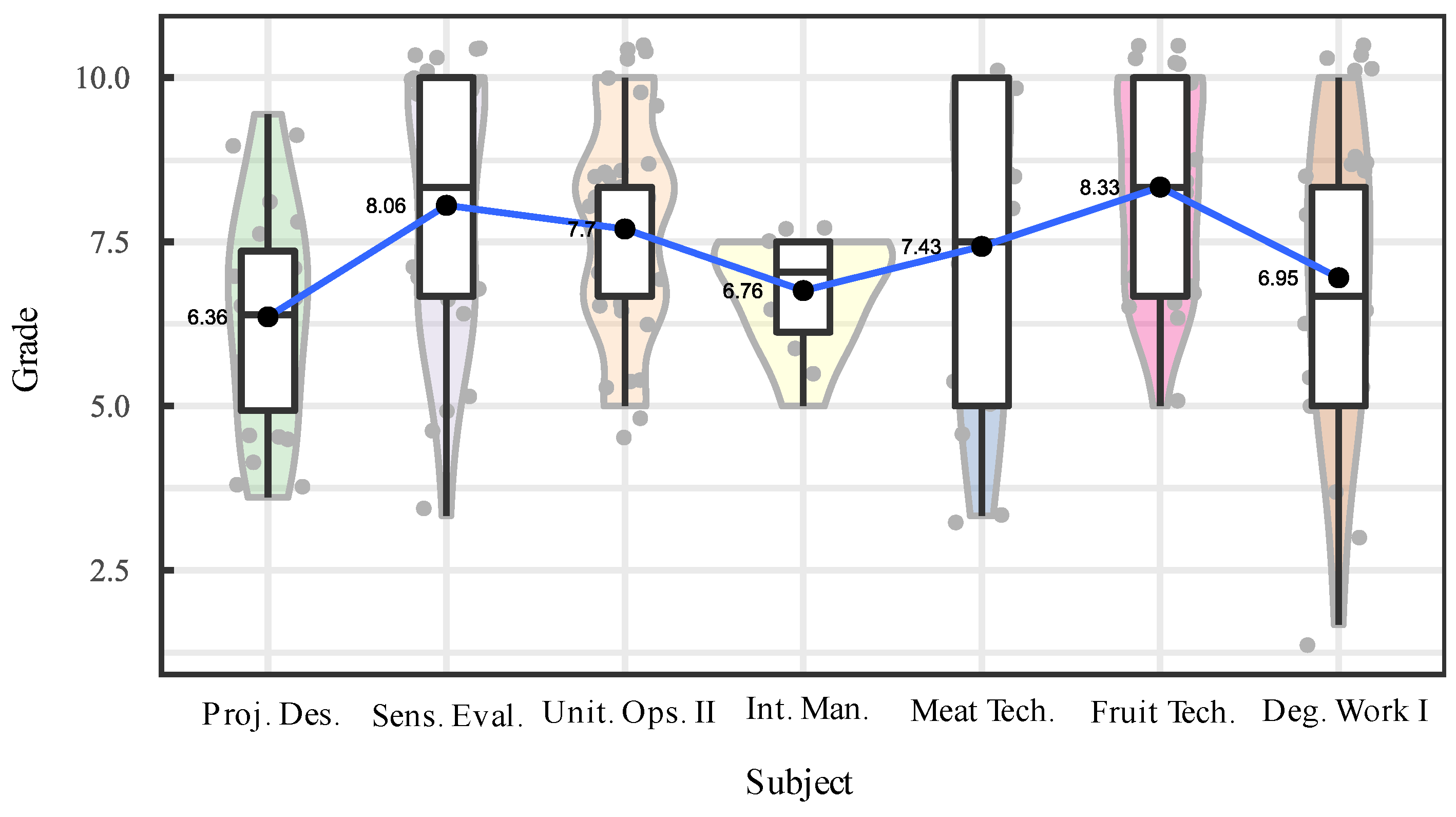

| Kruskal-Wallis Test – Qualification ~ Subjects | |||||||

| Kruskal Wallis χ2 | 18.434 | Degrees of freedom | 6 | p- value | 0.005235 Significant |

||

| Posteriori – Dunn- Šidák test | |||||||

| Design and evaluation. of projects | AssessmentSensory | OperationsUnitary II | System ofIntegrated Management | Product Technology Meat | Frut Technologies . and Veg . | ||

| Sensory evaluation |

|

||||||

| Unitary Operations II |

|

|

|||||

| Integrated Management Systems |

|

|

|

||||

| Meat Products Technology |

|

|

|

|

|||

| Fruit and Vegetable Technologies |

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Degree Work I |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Subject | Mean | Median | Mode | Trimmed mean | Std. deviation | Coeff. of variation | Bias | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design and evaluation. of projects | 6.36 | 6.39 | 5.83 | 6.36 | 1.71 | 26.91 | -0.01 | -0.88 |

| Sensory evaluation | 8.06 | 8.33 | 10.00 | 8.15 | 1.95 | 24.21 | -0.58 | -0.63 |

| Unitary Operations II | 7.70 | 8.33 | 8.33 | 7.71 | 1.64 | 21.32 | -0.15 | -0.91 |

| Integrated Management Systems | 6.76 | 7.04 | 7.50 | 6.76 | 0.87 | 12.82 | -0.98 | 0.11 |

| Meat Products Technology | 7.43 | 7.50 | 10.00 | 7.50 | 2.30 | 31.01 | -0.28 | -1.25 |

| Fruit and Vegetable Technologies | 8.33 | 8.33 | 10.00 | 8.40 | 1.53 | 18.38 | -0.32 | -1.08 |

| Degree Work I | 6.95 | 6.67 | 8.33 | 7.04 | 2.23 | 32.06 | -0.43 | -0.36 |

| Kruskal-Wallis Test – Qualification ~ Subjects | ||||||||

| Kruskal Wallis χ2 | 18.434 | Degrees of freedom | 6 | p-value | 0.005235 Significant |

|||

| Posteriori – Dunn- Šidák test | ||||||||

| Design and evaluation. of projects | AssessmentSensory | OperationsUnitary II | System ofIntegrated Management | Product Technology Meat | Fruit and Vegetable Technologies | |||

| Sensory evaluation |

|

|||||||

| Unitary Operations II |

|

|

||||||

| Integrated Management Systems |

|

|

|

|||||

| Meat Products Technology |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Fruit and Vegetable Technologies |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Degree Work I |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Subject | Mean | Median | Mode | Trimmed mean | Std. deviation | Coeff. of variation | Bias | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design and evaluation. of projects | 6.36 | 6.39 | 5.83 | 6.36 | 1.71 | 26.91 | -0.01 | -0.88 |

| Sensory evaluation | 8.06 | 8.33 | 10.00 | 8.15 | 1.95 | 24.21 | -0.58 | -0.63 |

| Unitary Operations II | 7.70 | 8.33 | 8.33 | 7.71 | 1.64 | 21.32 | -0.15 | -0.91 |

| Integrated Management Systems | 6.76 | 7.04 | 7.50 | 6.76 | 0.87 | 12.82 | -0.98 | 0.11 |

| Meat Products Technology | 7.43 | 7.50 | 10.00 | 7.50 | 2.30 | 31.01 | -0.28 | -1.25 |

| Fruit and Vegetable Technologies | 8.33 | 8.33 | 10.00 | 8.40 | 1.53 | 18.38 | -0.32 | -1.08 |

| Degree Work I | 6.95 | 6.67 | 8.33 | 7.04 | 2.23 | 32.06 | -0.43 | -0.36 |

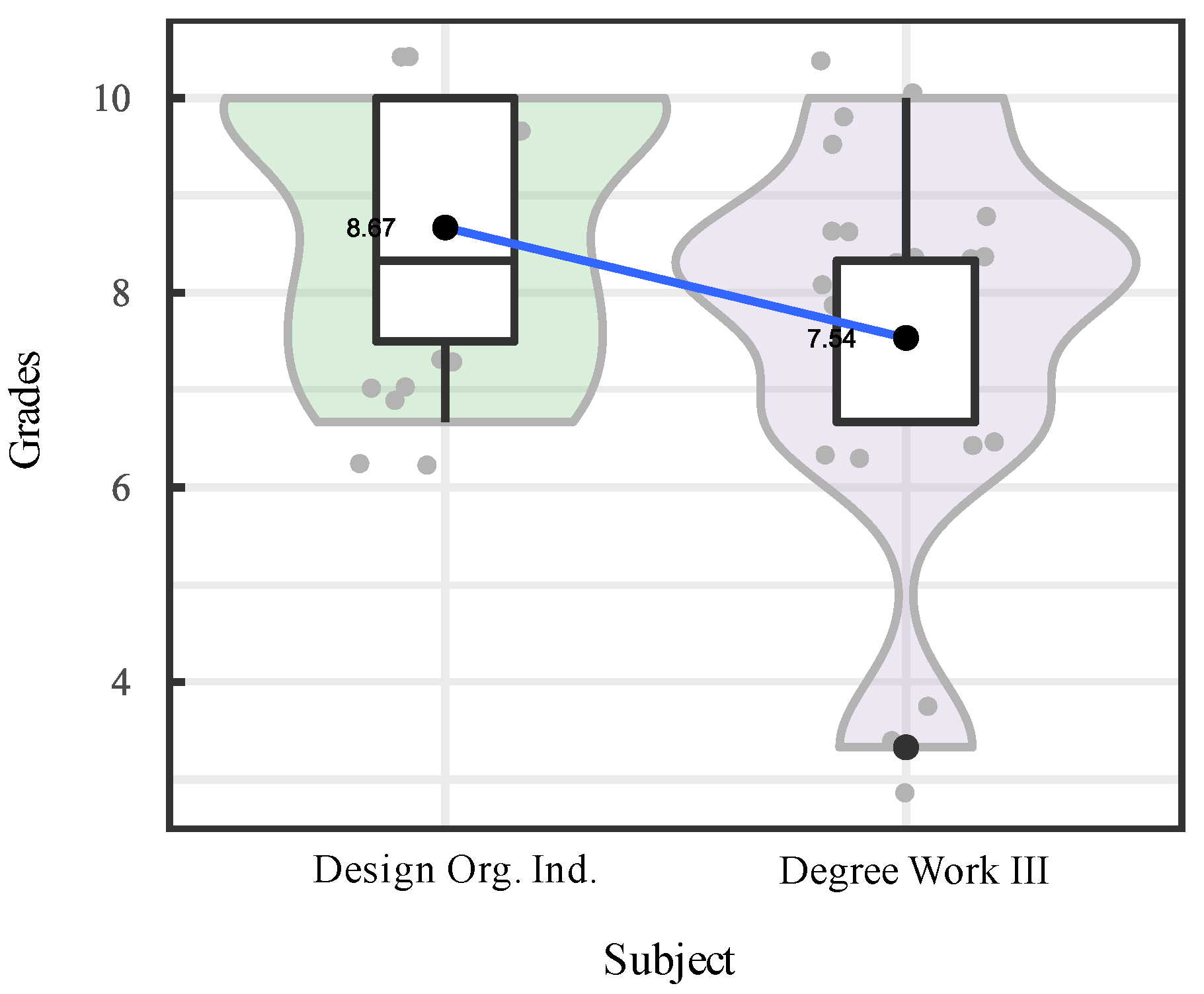

| Subject | Mean | Median | Mode | Trimmed mean | Std. deviation | Coeff. of variation | Bias | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design and organization of industrial plants | 8.67 | 8.33 | 10.00 | 8.71 | 1.37 | 15.75 | -0.33 | -1.60 |

| Degree work III | 7.54 | 8.33 | 8.33 | 7.62 | 2.00 | 26.57 | -1.01 | 0.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).