1. Introduction

Leukemia and lymphoma are common hematologic malignancies in children, young and adults which pose a huge threat to the lives of these patients worldwide despite the availability of efficient therapies. Finding ways to cure these diseases is of great importance in oncohematology.

In this study, we have showed that targeting the MST1/2 kinases, the key molecules in the Hippo signaling pathway may prove to be an effective way to treat hematologic tumors.

Hippo signaling pathway regulates the development of organs and their size, tissue regeneration, and apoptosis. The central role of this pathway in maintaining tissue homeostasis has been demonstrated [

1]. The disorders of this signaling pathway usually lead to tumor formation [

2,

3]. A detailed analysis of the Hippo signaling pathway is extremely hard to perform due to the multitude of its components and its ability to respond to a vast array of extracellular and intracellular signals [

4]. The key players in the Hippo signaling pathway include the MST1/2 and LATS1/2 kinases and their targets, YAP/TAZ transcription coactivators [

4,

5,

6]. LATS1/2 is phosphorylated by the MST1/2–SAV1 complex [

7]. It gets thereby activated, and in its turn phosphorylates and inactivates YAP and TAZ [

8,

9,

10]. If YAP/TAZ are not phosphorylated, they translocate to the nucleus and act via TEAD 1-4 and other transcription factors they interact with [

11,

12].

Disruption of this signaling pathway is observed in many human tumors. A recent systematic analysis of tumor samples revealed dysregulation of the Hippo signaling pathway components in many types of human cancers, including glioma, collateral cancer, endometrial cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma [

2,

10,

13]. YAP/TAZ hyperactivation stimulates cancer cell proliferation [

14]. The cells stop responding to the negative regulators of proliferation, overcome internal death mechanisms, and acquire resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs or molecular targeted therapy, which contributes to cancer recurrence [

15,

16]. However, the way the Hippo signaling pathway functions depends on the type of cell. For example, in hematopoietic cells, the pathway works in an atypical way or an alternative variant is used. Unlike solid tumors, knockdown MST1 or increasing YAP1 expression in hematopoietic tumors inhibits growth and leads to apoptosis [

17]. In leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma, low YAP1 levels block apoptosis, while activating YAP1 causes death of hematological cancer cells. Genetic inactivation of MST1 restores unphosphorylated YAP1 and triggers apoptosis in vitro and in vivo [

18]. These data demonstrate that MST1 can be a promising therapeutic target and provide a rationale for the development and clinical evaluation of novel MST1 inhibitors. The CN103429582A Patent describes the drug called XMU-MP-1. This compound is a reversible, potent and selective inhibitor of Mammalian sterile 20-like kinases 1/2 (MST1/2), the key molecules in the Hippo signaling pathway. XMU-MP-1 blocks the activity of MST1 and MST2 kinases, which reduces the phosphorylation of endogenous LATS1/2 and YAP1 in human liver carcinoma (HepG2) cells when applied in the concentrations from 0.1 to 10 μM in a dose-dependent manner. This leads to activation of YAP1 and TAZ and their nuclear translocation. Similar results have been obtained for other tumor cell lines [

20].

XMU-MP-1 was originally designed and used as a “small molecule” to analyze the Hippo signaling pathway [

19,

20] and as a drug promoting liver regeneration, as well as for the prevention and treatment of hematopoietic system diseases caused by oxidative stress and ionizing radiation. XMU-MP-1 treatment restores hematopoietic stem cell and progenitor cell functions under the oxidative stress induced by ionizing radiation and also increased the survival rate of mice which received lethal radiation doses [

21].

We have demonstrated for the first time the antitumor activity of XMU-MP-1 against hematologic tumors [

21] (Preprints.org Doi: 10.20944/preprints202502.0217.v1). In this study, we showed that XMU-MP-1 effectively inhibits the growth of B- and T-cell hematologic tumors. XMU-MP-1 blocks the cell cycle in the G2/M phase, inducing cell death, apoptosis and autophagy. It also enhances the effects of doxorubicin. A whole transcriptome analysis revealed key regulatory genes involved in these processes, whose expression is altered in response to XMU-MP-1 treatment.

2. Results

2.1. Hippo Pathway Inhibitor XMU-MP-1 Suppresses the Growth of B and T Tumor Cells

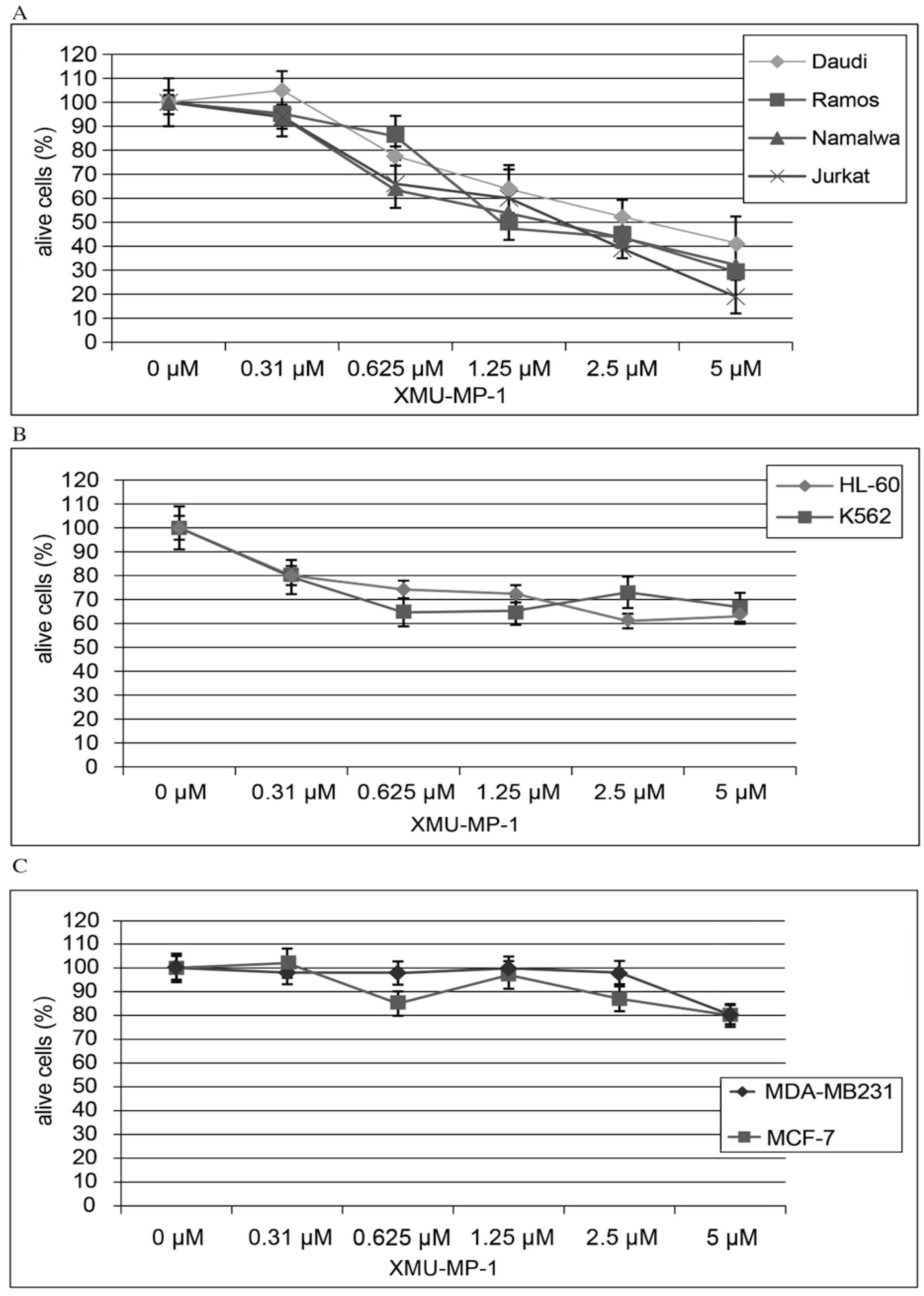

Using the CellTiter AQueous One Solution kit we have shown that treatment of hematopoietic cell lines with the MST1/2 inhibitor XMU-MP-1 causes a concentration- dependent inhibition of cell population growth (

Figure 1). This XMU-MP-1 effect was particularly strong in the B and T tumor cell lines (

Figure 1a). EC50 is achieved in the Namalwa, Raji, Ramos, Jurkat, and Daudi cell lines in 72 h at XMU-MP-1 concentrations ranging from 1.25 to 2.7 µM (

Figure 1a). At the same time, HL-60, and K562 cell lines show higher resistance to XMU-MP-1 (

Figure 1b). The triplet-negative and triplet-positive breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB231 and MCF-7 are resistant to XMU-MP-1 in the discussed concentration range (

Figure 1c).

We have performed analysis of MST1 expression in the cell lines used in this work and have demonstrated high levels of MST1 expression in Namalwa, Daudi and Ramos В-cell lymphoblastomas and Jurkat Т-cell lymphoblastoma (

Supplementary Figure S1).

CellTiter AQueous One Solution kit (MTT/MTS analysis) is a common method used to study cell proliferation and death. However, the results may reflect not only changes in the number of cells, but also changes in the metabolic activity of the cellular population. To confirm that the observed effects were associated with a decrease in cell population, we performed a direct count of Namalva cells treated with XMU-MP-1 and control cells at 24, 48, and 72 hours after treatment. We found that XMU-MP-1 suppressed the growth of the cell population (

Supplementary Figure S2).

2.2. XMU-MP-1 Induces Apoptosis in Hematopoietic Tumor Cells

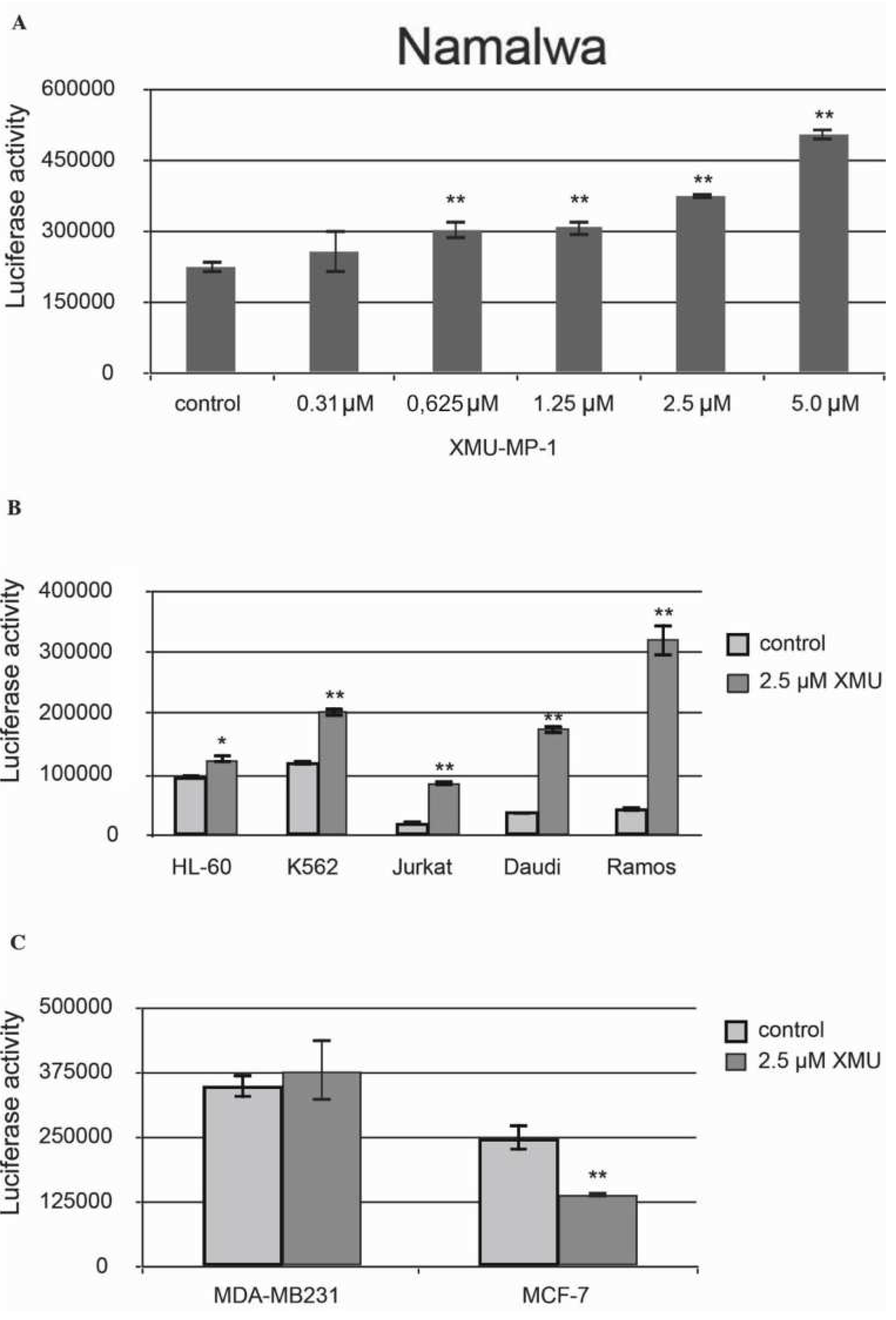

We have then demonstrated that XMU-MP-1 causes apoptosis in Namalwa cells. The Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay protocol was used in this experiment. The analysis demonstrated a significant concentration-dependent increase in basic caspase 3/7 activity in XMU-MP-1–treated Namalwa cell line (

Figure 2a).

XMU-MP-1 also causes apoptosis in the Daudi, Ramos, Jurkat, K562, HL-60, and MP-1 cell lines. However, the XMU-MP-1-induced increase in caspase 3/7 activity may differ significantly between these tumor cell lines (

Figure 2b). It is important to mention that XMU-MP-1 doesn’t induce caspase 3/7 activation and apoptosis in the breast cancer MDA-MB231 and MCF-7 cell lines. Suppression of the basic caspase 3/7 activity level can even be observed in the MCF-7 cells, which indicates the suppression of apoptosis as a result of XMU-MP-1 application (

Figure 2c).

To summarize, the results of our experiments have demonstrated that the response of cells to XMU-MP-1 being largely cell-specific. Antiproliferative and proapoptotic responses were found predominantly in the B- and T-cell lines.

2.3. XMU-MP-1 Increases the Sensitivity of Tumor Cells to Doxorubicin

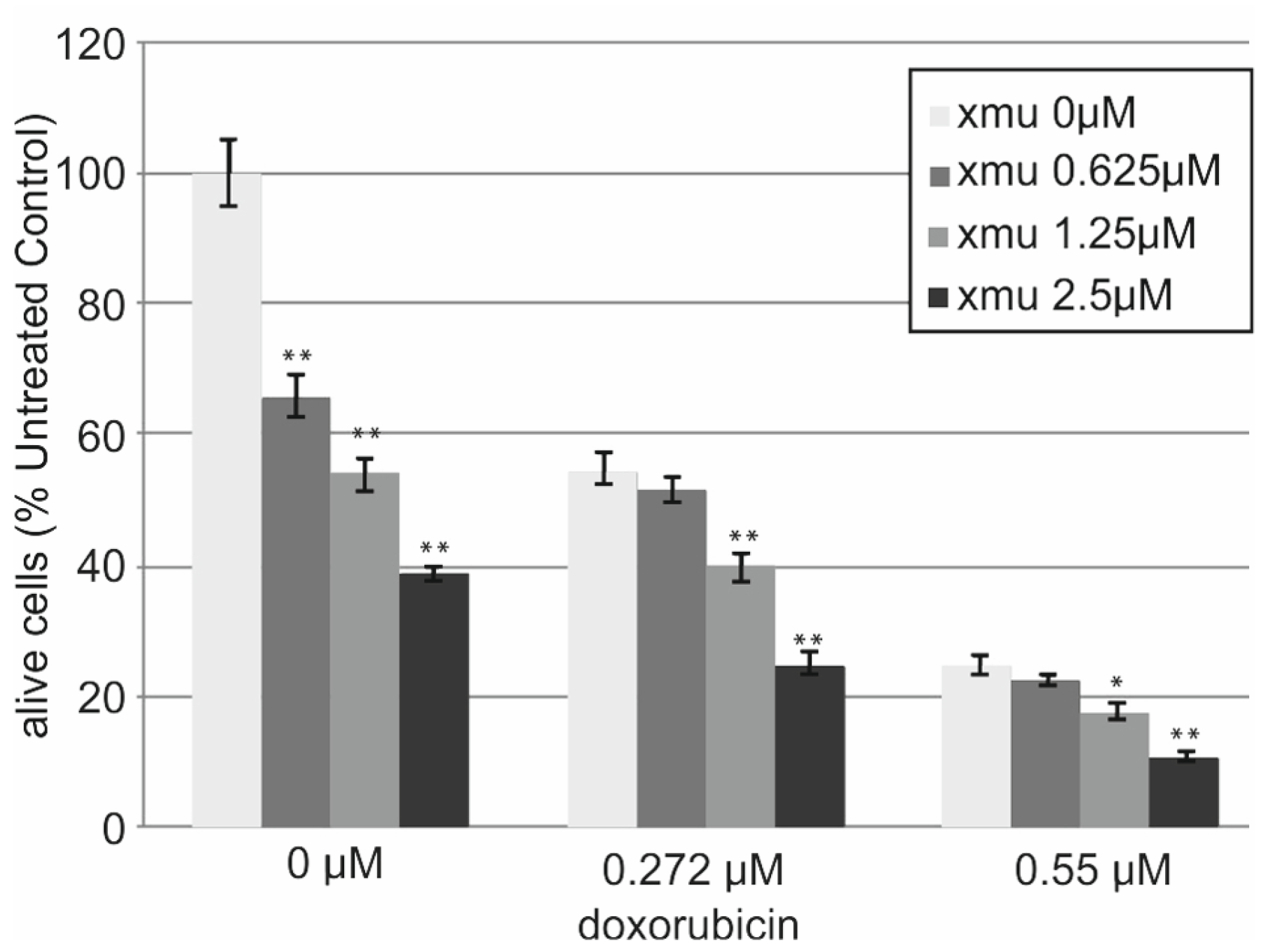

We performed in vitro analysis of the resistance of the B-cell lymphoma tumor cells Namalwa to the combined action of XMU-MP-1 and doxorubicin. The addition of XMU-MP-1 to the culture medium resulted in a dose-dependent enhancement of the chemotherapeutic action of doxorubicin (

Figure 3).

We observed the additive effect of combined XMU-MP-1 and doxorubicin resulting in their total effect being lower than the sum of effects, but higher than the effect of either compound used separately (

Supplementary Table S1). Doxorubicin is an antitumor anthracycline group antibiotic, the genotoxic drug which causes damage to genomic DNA. It is used to treat many different malignancies including lymphoblastic leukemias and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas.

2.4. RNA-Seq

Herein, for the better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of the effects exerted by the Hippo signaling pathway inhibitor XMU-MP-1 on the B-cell lymphoma, we carried out a whole transcriptome analysis and identified genes which expression changes after cell line Namalwa treatment with XMU-MP-1. We have also determined their biological functions and the underlying mechanisms of XMU-MP-1 action in Namalwa cells. Towards this we have prepared cDNA libraries from the control Namalwa cell and Namalwa cells to which XMU-MP-1 was applied in the concentrations of 0.3 µМ and 2.5 µМ for 72 h.

Human mRNA profiles of Namalwa cells and Namalwa cells treated with 0.3 or 2.5 μM of XMU-MP-1 were generated using new generation sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq platform. RNA-seq was used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in cells treated with XMU-MP-1 (GEO database: GSE80287). Changes in gene transcription levels were considered significant based on a fold change of ≥2.0 and a Paji ≤ 0.01.

DEGs common for the 0.3 µM and 2.5 µM XMU-MP-1 treatments had a similar, unidirectional response (either up or down), response levels being different though. We also observed that at the higher concentration, the resulting change in gene activity was more pronounced and the effect could differ by several times (Supplementary

Tables S2–S5). This shows that the action of XMU-MP-1 on gene expression is concentration dependent.

2.5. Functional Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

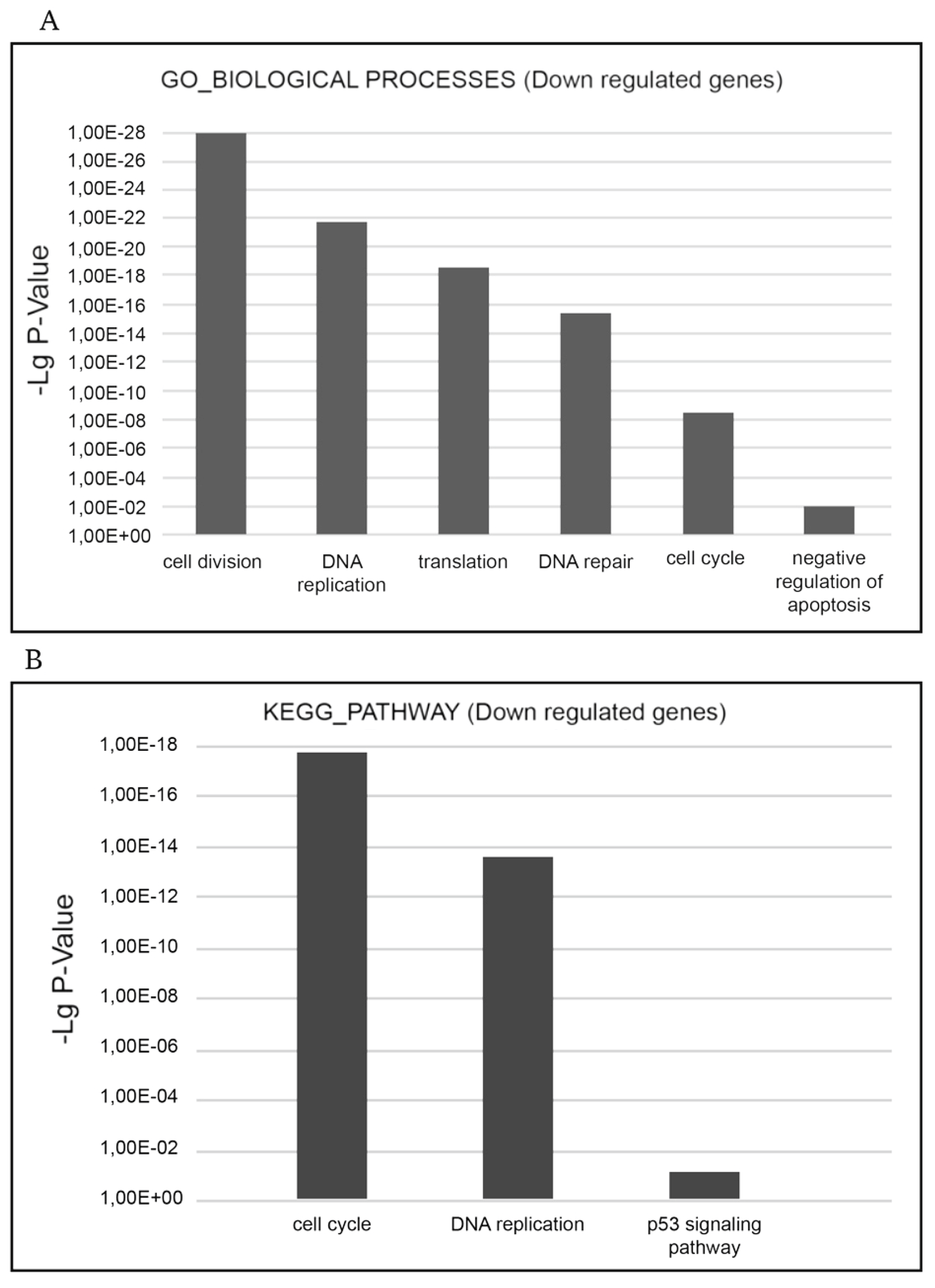

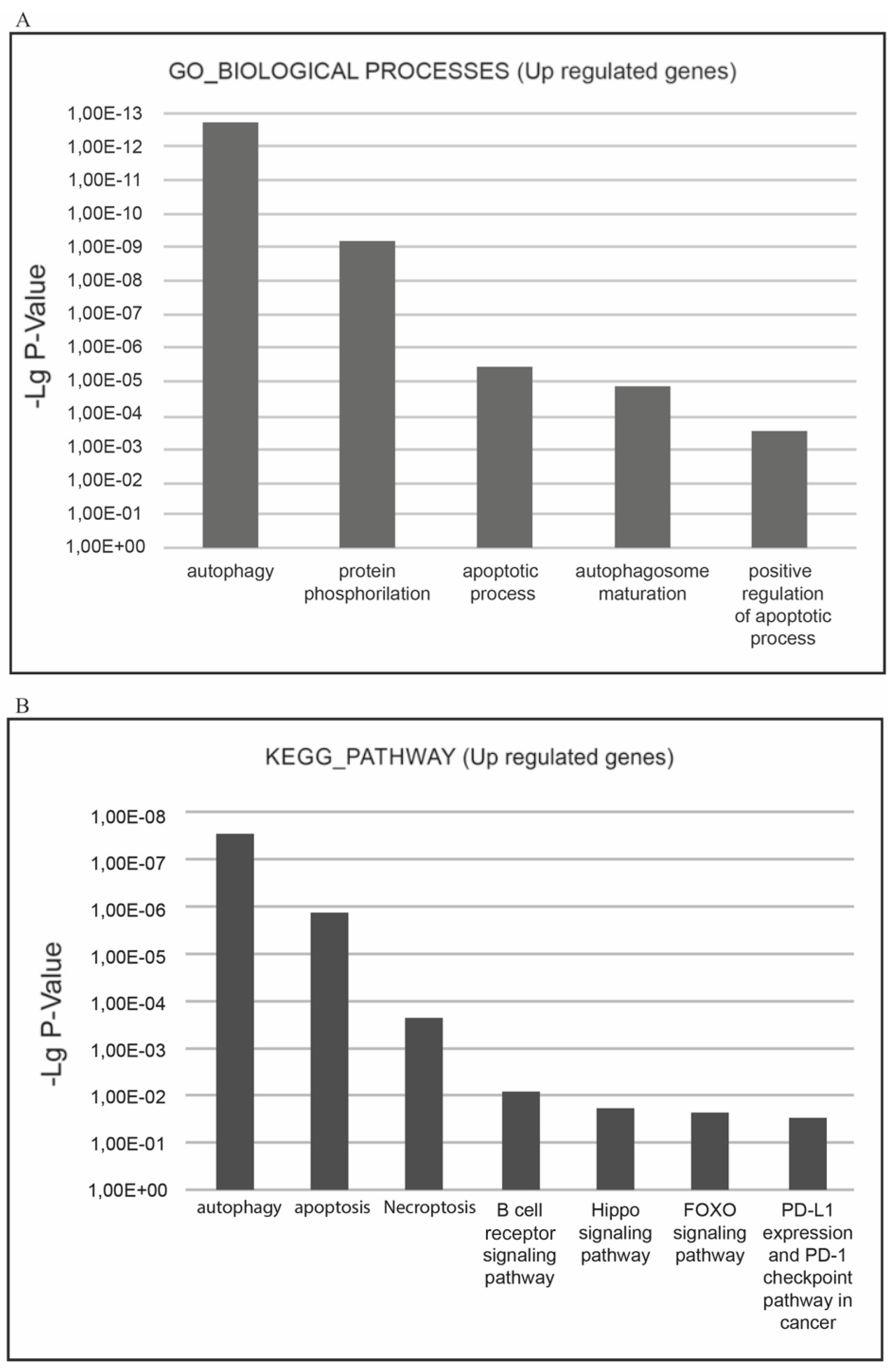

To identify biological processes and to determine more relevant groups of DEGs regulated by XMU-MP-1, we performed functional enrichment analysis by DAVID utilizing the GO (gene ontology) and KEGG pathways databases. Three gene ontology domains (biological process, cellular component, and molecular function) were analyzed for DEGs.

The functional enrichment analysis demonstrated XMU-MP-1 to be a negative regulator of cell cycle and a positive regulator of programmed cell death in hematopoietic tumor cells.

The most relevant downgulated processes, which are present in GO_BIOLOGICAL PROCESSES databases are ‘cell cycle’, ‘cell division’, ‘mitosis’, ‘DNA replication’, ‘DNA repair’, ‘DNA damage’, ‘mRNA splicing’, and ‘stress response’. The most relevant downregulated KEGG pathways are ‘cell cycle’, ‘DNA replication’, and ‘p53 signaling pathway’ implying that negative cell cycle regulation is the XMU-MP-1 function in Namalwa cells (

Figure 4a.b).

The ‘cell cycle’ term encompasses a significant group of downregulated DEGs which participate in cell cycle regulation (

Supplementary Table S2). This group includes the E2F family transcription factors (E2F1, E2F2, E2F7, and E2F8), which expression is 7-15 times decreased. The E2F family of transcription factors play a key role in cell cycle control. As transcription activators they interact with the promoters of the genes which products are engaged in cell cycle regulation or DNA replication and control cell cycle progression. Along with the downregulation of the E2F family transcription factors expression, the expression of other key cell cycle regulators is significantly downregulated too; the expression of many of them is under E2F control. These include cell division cycle genes (CDC6; CDC7; CDC20; CDC25A; CDC25B; CDC25C, and CDC45), which regulate the cell cycle at its different stages, cyclins including А2, which controls both the G1/S and the G2/M transition phases of the cell cycle, and cyclin B1(CCNB1) and cyclin B2(CCNB2), which are indispensable in the control of cell cycle at the G2/M (mitosis) transition, kinases—the regulators of the cell cycles including cyclin dependent kinase 1(CDK1), Checkpoint kinase 1(CHEK1), polo-like kinase 1(PLK1) and others, мinichromosome maintenance complex components (MCM2-7), Origin recognition complex subunits 1 and 6 (ORC1 and PRC6) and others. Thus, XMU-MP-1 triggers a cascade of transcription repression of the key cell cycle regulators in Namalwa cells.

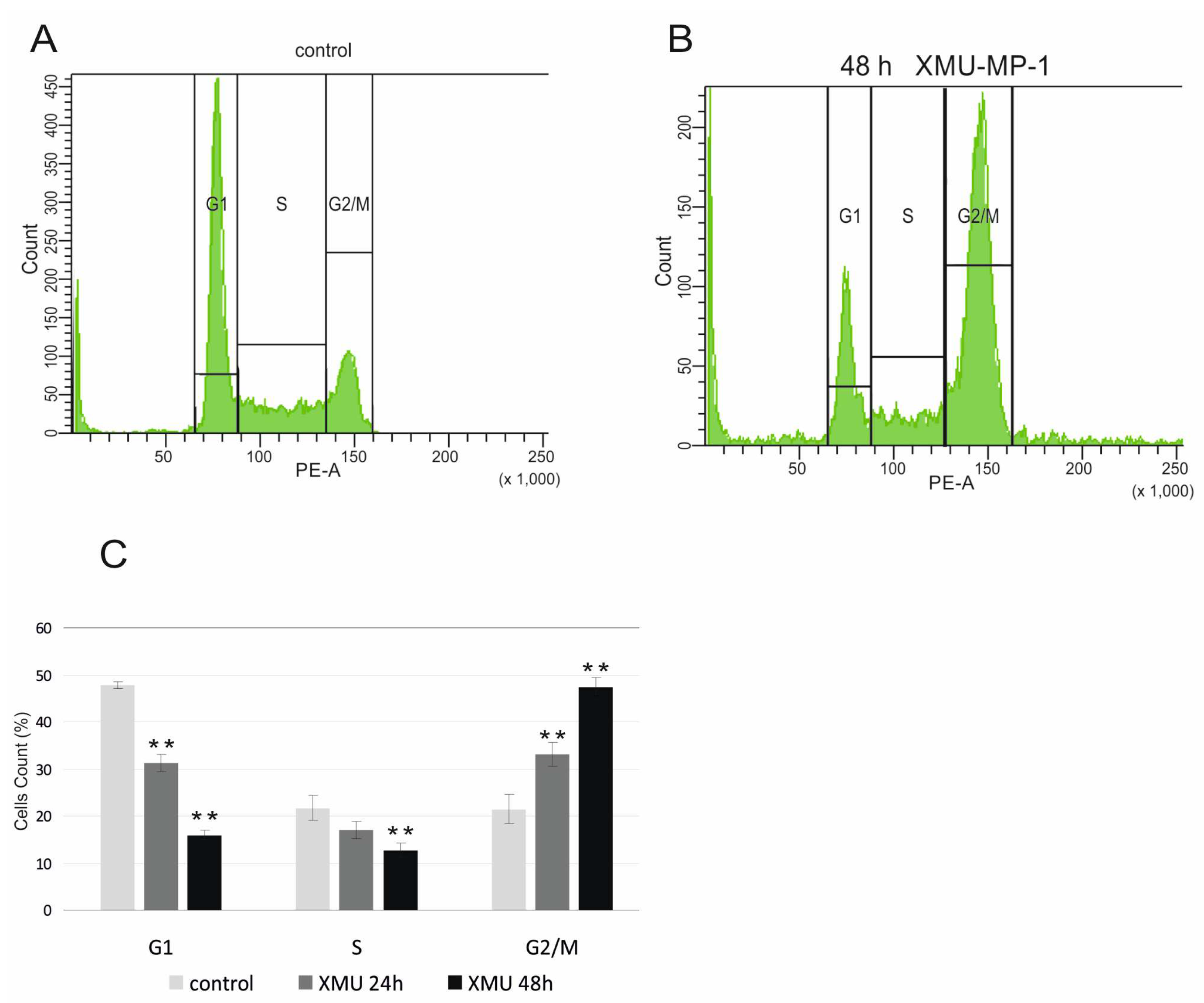

To confirm the functional significance of these transcriptome changes, we performed a cell cycle analysis using flow cytometry and showed that XMU-MP-1 significantly alters the cell cycle and leads to cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase of Namalwa cells (

Figure 5).

The results obtained from the RNA-Seq and flow cytometry assays are in perfect agreement with the experiments that demonstrate the suppression of B and T tumor cell growth (

Figure 1).

The most relevant upregulated processes, which are present in the KEGG pathways and GO_BIOLOGICAL PROCESSES databases are ‘autophagy, ‘apoptosis’, ‘necroptosis’, which confirms the suppressive effect of XMU-MP-1 on cell population growth and demonstrates the mechanisms by which XMU-MP-1 regulates the programmed cell death (

Figure 6a,b).

XMU-MP-1 causes changes in the activity of many key apoptotic regulatory genes (

Supplementary Table S3). The ‘apoptosis’ term includes a significant group of upregulated DEGs involved in the development and regulation of apoptosis: CASP6 и CASP7 caspases; BBC3; BCL2A1; BLCAP; FAS (Fas cell surface death receptor); TRAF1; TRAF4; TNFSF10; TRADD; XAF1; APAF1; BIRC3 and other. The proteins encoded by these genes are essential for the development of apoptosis: APAF1, a cytoplasmic protein that initiates apoptosis and forms an oligomeric complex, called an apoptosome, which activates caspases and triggers the caspase cascade; caspases 6 and 7; FAS, a cell surface death receptor that promotes apoptosis; pro-apoptotic proteins from the BCL2 family, such as BBC3 and BCL2A1, and apoptosis regulatory proteins like MOAP1 and XAF1. MOAP1 interacts with BAX to activate caspase-dependent apoptosis, while XAF1 binds and inactivates apoptosis inhibitors (IAPs), leading to cell death.

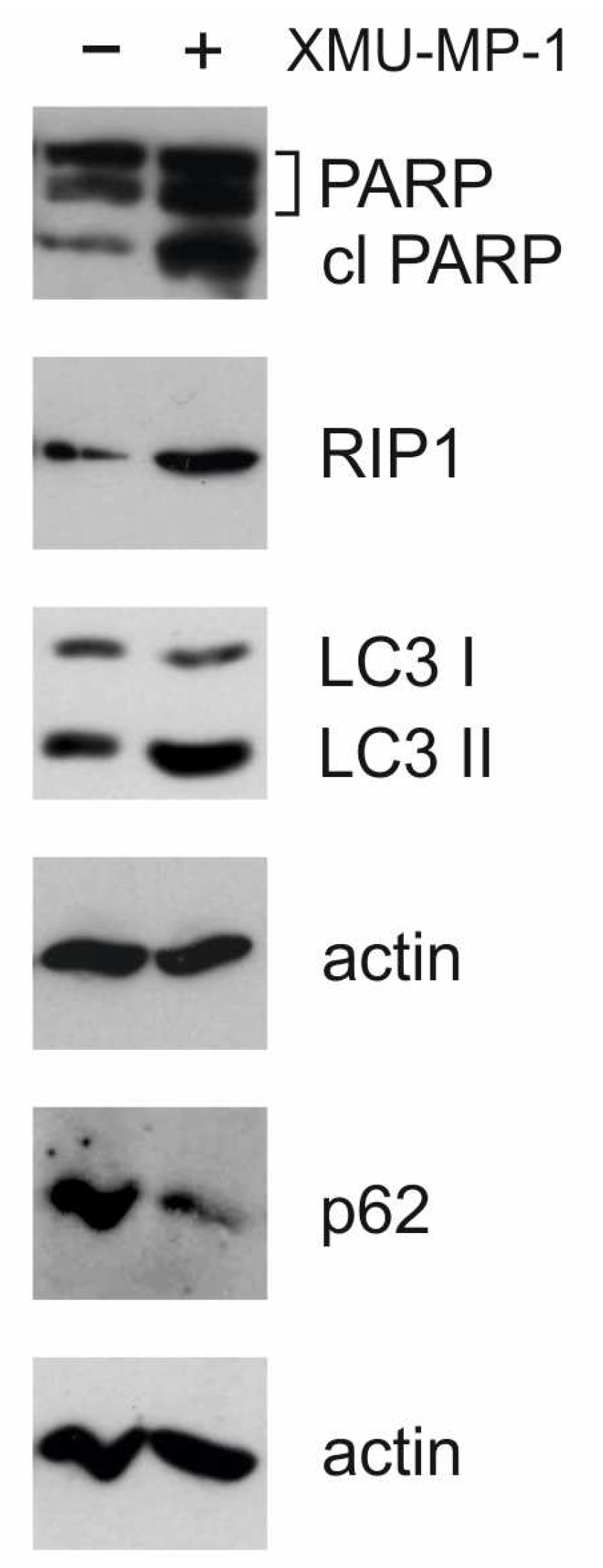

Activation of apoptosis is also supported by the results of Western blot analysis. In response to XMU-MP-1 treatment, an accumulation of the cleavage form of PARP-1 (poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase 1) was observed (

Figure 7). This molecule is a downstream target of caspase-3 and indicates the activation of the caspase cascade and apoptosis [

22]. This finding has also been confirmed by the results of the caspase 3/7-Glo assay (

Figure 2).

XMU-MP-1 considerably increases the expression of the key genes participating in autophagy activation and autophagosomes maturation (

Supplementary Table S4). The ‘autophagy’ term includes a significant group of upregulated DEGs involved in autophagy regulation and autophagosome membrane formation including beclin 1 (BECN1); DEPP autophagy regulator 1 (DEPP1); DNA damage regulated autophagy modulator 2( DRAM2); autophagy related 2A (ATG2A); autophagy related 4B cysteine peptidase (ATG4B); death associated protein (DAP); VPS18 core subunit of CORVET and HOPS complexes (VPS18); VPS39 subunit of HOPS complex (VPS39); autophagy and beclin 1 regulator 1 (AMBRA1); ectopic P-granules 5 autophagy tethering factor (EPG5), and unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (ULK1).

The activation of autophagy in cells was confirmed by Western blot analysis.

Figure 7 shows that, under XMU-MP-1 treatment, the p62/SQSTM1 protein (sequestosome 1) is degraded and the accumulation of LC3-II (microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B light chain 3A) occurs. These two proteins are markers for autophagy [

22]. Additionally, there is an accumulation of RIP1 protein, which may be linked to apoptosis, necroptosis, or autophagy [

22]. These findings are consistent with RNA-Seq data showing transcriptome changes associated with programmed cell death and cell cycle defects.

Together, the combination of Western blot, RNA-Seq, and other assays showed that the reduction in the population of hematopoietic tumor cells under XMU-MP-1 is due to cytostatic and cytotoxic mechanisms.

We hypothesize that this cascade of changes begins with the activation of the Hippo signaling pathway and leads to the death of Namalwa cells. Under the influence of XMU-MP-1, the expression of some key genes in the Hippo signaling pathway changes. This change in expression suggests that the Hippo signaling pathway may be regulated through a feedback mechanism. XMU-MP-1 leads to an increase in the expression of several genes, including MST1 serine/threonine kinase 4, LIMD1 (LIM domain containing 1), MOB1A, MOB1B, NF2, RASSF2.

3. Discussion

MST1/2 regulates the development of T and B cells through the “noncanonical” Hippo signaling pathway in hematopoiesis and hematopoietic tumor cells [

23,

24]. When the MST1 and MST2 kinase activities are inhibited, the canonical Hippo pathway leads to increased cell proliferation and decreased apoptosis in many somatic cells. However, in hematopoietic tumor cells, we observe an opposite effect [

19].

We have investigated how XMU-MP-1, the inhibitor of the serine/threonine kinases MST1/2, the key components of the Hippo pathway, affects hematopoietic tumors and have demonstrated that treatment of several hematopoietic tumor cell lines with XMU-MP-1 causes suppression of their growth and induces programmed cell death. This treatment causes significant changes in the transcriptome of these cells, while the expression of “canonical” Hippo pathway target genes such as Cyr61 (CCN1) and CTGF (CCN2) remains unchanged in Namalwa cells under MST1/2 inhibition. These findings suggest that the Hippo pathway activates and regulates alternative transcriptional pathways in hematological cancer cells

The results of whole transcriptome analysis revealed that XMU-MP-1, in Namalwa cells, suppresses the expression of genes whose products play a crucial role in regulating the cell cycle and DNA replication. It is known that an imbalance in the levels of proteins that regulate the cell cycle can lead to significant disruptions in the mitotic process and stop the cell cycle in the G2/M phase, which can trigger a mitotic catastrophe and subsequent cell death through apoptosis, necroptosis, or autophagy [

25]. Similar effects we observed in Namalwa cells after XMU-MP-1 treatment. XMU-MP-1 induces cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase and activates genes that regulate three types of programmed cell death: apoptosis, autophagy, and necroptosis (

Supplementary Table S5). This activation suggests that XMU-MP-1 has a specific effect on the death of hematopoietic tumor cells, but it does not affect triple-negative or triple-positive breast cancer cells and does not cause their death.

The activation of various types of programmed cell death by XMU-MP-1 has potential for the treatment of hematological cancers because the inhibition of programmed cell death is a strategy widely used by tumor cells to resist damaging factors. For example, the ability of neoplastic cells to escape apoptosis significantly increases their viability, making the activation of apoptosis essential for effective antitumor treatment

The issue of autophagy appears to be more complex. It is known that autophagy plays a crucial role in maintaining the balance between proliferation and cell death of B and T lymphocytes. However, the cytotoxic role of autophagy has also been shown in cancer. There is abundant evidence that autophagy acts as a suppressor of neoplasm development [

27,

28].

Some effective chemotherapy drugs aim to activate one or more types of programmed cell death. For example, Rasfonin triggers apoptosis, autophagy, and necroptosis in kidney cancer cells [

29]. The antitumor activity of arsenic trioxide (As2O3) in acute promyelocytic leukemia depends on the activation of autophagy, leading to tumor cell death [

29,

30]. RAD001 (everolimus), a mTOR inhibitor, also blocks cell survival in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia by inducing autophagy [

31,

32]. Resveratrol, another drug, induces the death of chronic myeloid leukemia cells through autophagy [

33]. All these studies emphasize the significant role of autophagy in hematologic cancers. Our study demonstrates that XMU-MP-1 activates the autophagy pathway by inducing the expression of genes involved in autophagosome assembly, including beclin 1, DEP1, DAP, VPS18, and VPS39 and upregulates the expression of AMBRA1.

Activation of necroptosis also is an important therapeutic tool to target tumors that are especially resistant to apoptosis. For example, the anticancer drug shikonin exerts an antitumor effect on osteosarcoma by triggering RIPK1 and RIPK3-dependent necroptosis [

34]. Resibufogenin triggers necroptosis in colon cancer cells thereby inhibiting tumor growth [

35]. In our work, we have shown that the expression of RIPK1 protein was significantly increased and necroptosis regulator genes FAS, TNFSF10, TRADD, and RIPK1, as well as the expression of PEA15, the caspase 8 inhibitor, were activated in the presence of XMU-MP-1 in the Namalwa cell population (

Supplementary Table S5).

In our work, we have shown that XMU-MP-1 treatment increases the effectiveness of doxorubicin chemotherapy. Doxorubicin is a drug that damages DNA and is used to treat different types of blood cancer. Previous studies have found that low doses of doxorubicin (600 nanomolar) can cause a mitotic catastrophe due to DNA damage [

22]. We propose that combining XMU-MP-1 with doxorubicin increases the likelihood of this process by inhibiting key regulators of the cell cycle and arresting cells in the G2/M phase, thereby enhancing the cytotoxic effects of doxorubicin.

Another mechanism that causes an increased effect of doxorubicin when combined with XMU-MP-1 is due to the fact that in hematological tumors, DNA damage leads to the activation of a proapoptotic pathway based on the nuclear relocation of the ABL1 kinase. Previous studies have shown that low levels of YAP1 can block ABL1-induced apoptosis in hematological malignancies, while the genetic inactivation of MST1 restores YAP1 levels, causing cell death both in vitro and in vivo [

19]. As a result, the simultaneous use of these two compounds leads to an increase in the death rate of Namalwa cells.

It is possible that the combined use of doxorubicin and XMU-MP-1 may reduce the effective dose of doxorubicin in the treatment of hematological cancers and significantly reduce the life-threatening toxic effects of doxorubicin, such as free radical formation, which underlies cardiotoxicity, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia and necrotizing colitis. XMU-MP-1 is known to stimulate platelet recovery after immune thrombocytopenia and promote the migration of megakaryocytes from the bone marrow [

35]. It also promotes the regeneration of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, and reduces damage to the small intestine caused by whole-body exposure to radiation, increasing the average survival time in mice exposed to lethal doses of radiation [

21]. Our previous studies have also shown that XMU-MP-1 enhances the antitumor activity of other chemotherapy drugs, such as etoposide and cisplatin, in hematologic tumors [

37]. Therefore, XMU-MP-1 has the potential to be an effective component of combination therapy for hematologic tumors, however further investigation are required.

4. Conclusions

Taking into account the results obtained in our work, we consider the investigation of the possibility of using the MST1/2 kinase inhibitors in the treatment of hematologic tumors extremely promising.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Cell Lines

B lymphoblastoid Burkitt lymphomas Namalwa, Daudi, and Ramos, Jurkat T-cell lymphoblastoma, HL-60—acute promyelocytic leukemia, promyeloblast; K562—chronic myeloid leukemia at blast crisis, and breast adenocarcinomas MDA MB-231 and MCF-7 were used in the work. Human cell lines were obtained from the Russian Cell Culture Collection, Institute of Cytology, St. Petersburg, Russia. Cells were maintained in DMEM or RPMI (“GIBCO”, “Thermo Fisher Scientific”, United States) with 10% FCS (FBS; “HyClone”, United States), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, in the 5% CO2 atmosphere.

5.2. Cell Proliferation Assay

Cells were cultured at +37ºС in the humid atmosphere in the cultural plates manufactured by ТРР (Switzerland) in DMEM or RPMI (Life Technologies, United States) with the addition of 10% calf fetal serum (BioSera, France), in 5% СО2. The effect of XMU-MP-1 on Namalwa cell proliferation was evaluated using the CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution kit (Promega, USA). Namalwa cells were inoculated into a 96-well plate at the density of 3x104 cells per well in the DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum 24 h prior to the addition of the studied compound. Antiproliferative activity of XMU-MP-1 was studied by treating Namalwa cells with the XMU-MP-1 reagent at the concentrations of 0.3; 0.6; 1.25, and 2.5 μM in DMSO. Cells with only DMSO and no reagent added served as the control. After 72 h of incubation, antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects of XMU-MP-1 were analyzed using the CellTiter 96 suppresses the expression AQueous One Solution kit (Promega, United States) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Solutions’ optical density was measured at 490 nm using the Chameleon V plate reader (Hydex Oy, Finland). The amount of the formazan product calculated based on the absorbance rate at 490 nm is in direct proportion to the live cells number in the culture. Cell viability was assessed relative to the control, and the concentration reducing cell viability by 50% (CD50) was determined.

5.3. Bioluminescence Caspase 3/7 Assay

Apoptosis caused by XMU-MP-1 in the cell lines was assessed using the Caspase 3/7-Glo kit (Promega, United States). Namalwa cells were inoculated into a 96-well plate at the density of 2x104 cells per well in the DMEM or RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum 24 h prior to the addition of the studied compound. Apoptotic activity of XMU-MP-1 was studied by treating Namalwa cells with the XMU-MP-1 reagent at the concentrations of 0.3; 0.6; 1.25, and 2.5 μM. The other cell lines were treated with XMU-MP-1 at the concentration of 2.5 μM. Cells with only DMSO and no reagent added served as the control. After 48 h of incubation, the apoptosis was assessed by measuring the activity of caspases 3 and 7 in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. Towards this end, 20 µl of reagent was added to each well and cells were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The luminescence of the solutions was then measured using the Chameleon V plate reader (Hydex Oy, Finland). Luminescence activity is directly proportional to the activity of the terminal capases 3 and 7 and to the cell apoptosis levels in the culture. Apoptosis level at different concentrations of XMU-MP-1 was estimated based on the luminescence levels relative to control.

5.4. Determination of Cell Cycle by Flow Cytometry

Cells were seeded in 60 mm2 dishes and treated 0.6 µM XMU-MP-1. Only DMSO was added to the control group. The measurements were taken in three separate trials. 24 h and 48 h after treatment, cells were collected, fixed in 70% ethanol, and stained with 50 µg/mL propidium iodide (PI) treated with 100 µg/mL RNase A (Sigma, catalog R-4875) at 370 C for 60 min. Flow cytometric analysis was carried out using a BD LSRFortessa Cell Analyzer equipped with BD Bioscience software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). The distribution of cells according to their fluorescence was determined for G1, S, and G2/M subpopulations.

5.5. Antibodies and Western blot Analysis

We used the following antibodies: Rabbit anti-PARP (Cell Signaling, CST 9541) and Rabbit anti-cleaved PARP (CST 137653), Rabbit anti-beta-actin (CST 13E5), Rabbit anti-LC3 (CST 12741), and Rabbit anti-p62 (CST B0255). Additionally, we used Rabbit anti-RIP1 (CST 94C12) and Goat anti-Rabbit HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch, 111-035-144). Protein extracts (10 µg) were mixed with loading buffer containing DTT and incubated at 40°C for 10 minutes. The samples were then applied to 8% or 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in TBS for 1 hour at room temperature. 10 µg of cell protein extract was loaded into each lane, and beta actin was used as a loading control. The membranes were probed with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C and then washed three times for 15 minutes with TBS-T. After that, they were incubated for 1 hour at RT with anti-rabbit HRP antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-2005) at a 1:5,000 dilution. After four additional washing steps with TBS-T, signal detection was performed using the standard protocol and the ECL reagent (GE Healthcare).

5.6. Sequencing Library Preparation

Human Namalwa cells treated with 0.3 or 2.5 µM of XMU-MP-1 for 72 h and control Namalwa cells to which only DMSO was added were obtained in triplicate. The NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (NEB#E7490) was used to isolate mRNA. NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB #E7760) was used with 3 ug of total RNA for sequencing library construction. Standard Illumina protocols were used to make RNA libraries. AgencourtAMPure XP beads were used to purify double-stranded cDNA, ligation reaction products, and PCR reaction products.

5.7. NGS Sequencing and Data Processing

the KAPA Library Quant qPCR kit (Kapa Biosystems) was used to measure molar library concentrations. Library size distribution was assessed after PCR (12 cycles) using Agilent BioAnalyzer. Then, the cDNA libraries were normalized and pooled together in equal volumes. Finally, they were sequenced using 75-base pair double-ended reads on an Illumina NovaSeq instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The bcl2fastq v2.20 Conversion Software (Illumina) was utilized to obtain FASTQ files. The hisat software was used to map reads on the human genome (hg38). In each library, about 89–90% of the obtained data on average were uniquely aligned. The htseq-count package was used to calculate the number of reads which were mapped to known genes (ncbi—entrezID). The obtained values (cpm—countpermillion) for each gene in each library were combined into a matrix for further analysis. Filtration, normalization by the TMM method, variance estimation, and assessment of differentially expressed genes were performed using the edgeR module. A quasi-likelihood F-test (default in edgeR) was used to assess the statistical significance of observed expression changes. The Benjamini-Hochberg method was then applied to the resulting p-values to calculate the false discovery rate (FDR).

5.8. Functional Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

Gene Ontology (GO) screening was performed using DAVID (david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp) including GOTERM_BP_FAT (biological process), GOTERM_ MF_FAT (molecular function), and GOTERM_CC_FAT (cellular component), and KEGG Pathway (www.genome. jp/kegg/pathway.html) resources. DAVID calculates modified Fisher’s Exact p-values to demonstrate GO or molecular pathway enrichment. The Paji <0.01 was chosen as a cut-off criterion.

5.9. Statistics

Statistical analysis of the results from the Cell proliferation assay, the Bioluminescence Caspase 3/7 assay, and the flow cytometry assay was conducted using GraphPad software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Student’s t-tests were used to generate p-values. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01)

5.10. Accession Number

RNA-Seq data GSE279247

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1; Figure S2; Table S1; S2; S3; S4; S5.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.V.P. and A.G.S, methodology, E.V.P. and A.G.S, validation, E.V.P., A.G.S, formal analysis, E.V.P., A.G.S, investigation, E.V.P., A.G.S, data curation, E.V.P., S.G.G, writing—original draft preparation, E.V.P, writing—review and editing, E.V.P., A.G.S., S.G.G; project administration, E.V.P.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (Agreement No. 075-15-2019-1660) Center for Precision Genome Editing and Genetic Technologies for Biomedicine Engelhardt Institute of Molecular Biology (E.V.P.), and by the Program of Fundamental Research in the Russian Federation for the 2021–2030 period (project No. 124031800074-4) (S.G.G. and A.G.S.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and provided by GEO Database GSE80287.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nikolay Lukinyh, Anton Pankratov and Svetlana Foto for their help in preparing the figures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Meng, Z.; Moroishi, T.; Mottier-Pavie, V.; Plouffe, S.W.; Hansen, C.G.; Hong, A.W.; Park, H.W.; Mo, J.S.; Lu, W.; Lu, S.; et al. MAP4K family kinases act in parallel to MST1/2 to activate LATS1/2 in the Hippo pathway. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 8357. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Pan, D. The Hippo Signaling Pathway in Development and Disease. Dev Cell 2019, 50, 264–282. [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Hu, Y.; Lan, T.; Guan, K.L.; Luo, T.; Luo, M. The Hippo signalling pathway and its implications in human health and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 376. [CrossRef]

- Boggiano, J.C.; Vanderzalm, P.J.; Fehon, R.G. Tao-1 phosphorylates Hippo/MST kinases to regulate the Hippo-Salvador-Warts tumor suppressor pathway. Dev Cell 2011, 21, 888–895. [CrossRef]

- Praskova, M.; Khoklatchev, A.; Ortiz-Vega, S.; Avruch, J. Regulation of the MST1 kinase by autophosphorylation, by the growth inhibitory proteins, RASSF1 and NORE1, and by Ras. Biochem J 2004, 381, 453–462. [CrossRef]

- Glantschnig, H.; Rodan, G.A.; Reszka, A.A. Mapping of MST1 kinase sites of phosphorylation. Activation and autophosphorylation. J Biol Chem 2002, 277, 42987–42996. [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.L.; Lin, J.I.; Zhang, X.; Harvey, K.F. The sterile 20-like kinase Tao-1 controls tissue growth by regulating the Salvador-Warts-Hippo pathway. Dev Cell 2011, 21, 896–906. [CrossRef]

- Hergovich, A.; Schmitz, D.; Hemmings, B.A. The human tumour suppressor LATS1 is activated by human MOB1 at the membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006, 345, 50–58. [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.; Yu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, N.; Pan, D. Spatial organization of Hippo signaling at the plasma membrane mediated by the tumor suppressor Merlin/NF2. Cell 2013, 154, 1342–1355. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Li, L.; Lei, Q.; Guan, K.L. The Hippo-YAP pathway in organ size control and tumorigenesis: an updated version. Genes Dev 2010, 24, 862–874. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, B.; Wang, P.; Chen, F.; Dong, Z.; Yang, H.; Guan, K.L.; Xu, Y. Structural insights into the YAP and TEAD complex. Genes Dev 2010, 24, 235–240. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.G.; Moroishi, T.; Guan, K.L. YAP and TAZ: a nexus for Hippo signaling and beyond. Trends Cell Biol 2015, 25, 499–513. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.L.; Guan, K.L. The two sides of Hippo pathway in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 2022, 85, 33–42. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Du, S.; Lei, T.; Wang, H.; He, X.; Tong, R.; Wang, Y. Multifaceted regulation and functions of YAP/TAZ in tumors. Oncol Rep 2018, 40, 16–28. [CrossRef]

- Zanconato, F.; Cordenonsi, M.; Piccolo, S. YAP/TAZ at the Roots of Cancer. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 783–803. [CrossRef]

- Baroja, I.; Kyriakidis, N.C.; Halder, G.; Moya, I.M. Expected and unexpected effects after systemic inhibition of Hippo transcriptional output in cancer. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 2700. [CrossRef]

- Sezutsu, H.; Itoh, M.; Tohda, S. Effects of YAP Inhibitors and Activators on the Growth of Leukemia Cells. Anticancer research 2025, 45, 977–987. [CrossRef]

- Cottini, F.; Hideshima, T.; Xu, C.; Sattler, M.; Dori, M.; Agnelli, L.; ten Hacken, E.; Bertilaccio, M.T.; Antonini, E.; Neri, A.; et al. Rescue of Hippo coactivator YAP1 triggers DNA damage-induced apoptosis in hematological cancers. Nat Med 2014, 20, 599–606. [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; He, Z.; Kong, L.L.; Chen, Q.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, S.; Ye, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, X.; Geng, J.; et al. Pharmacological targeting of kinases MST1 and MST2 augments tissue repair and regeneration. Sci Transl Med 2016, 8, 352ra108. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, H.; Li, D.; Song, N.; Yang, F.; Xu, W. MST1/2 inhibitor XMU-MP-1 alleviates the injury induced by ionizing radiation in haematopoietic and intestinal system. J Cell Mol Med 2022, 26, 1621–1628. [CrossRef]

- Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Egorshina, A.Y.; Zamaraev, A.V.; Kaminskyy, V.O.; Radygina, T.V.; Zhivotovsky, B.; Kopeina, G.S. Necroptosis as a Novel Facet of Mitotic Catastrophe. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 3733. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Jing, Y.; Kang, D.; Yang, L.; Li, J.; Yu, Z.; Peng, Z.; Li, X.; Wei, Y.; Gong, Q.; et al. The Role of Mst1 in Lymphocyte Homeostasis and Function. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 149. [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Xu, H.; Du, X. The role of non-canonical Hippo pathway in regulating immune homeostasis. Eur J Med Res 2023, 28, 498. [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Park, T.; Noh, J.Y.; Kim, W. Emerging role of Hippo pathway in the regulation of hematopoiesis. BMB Rep 2023, 56, 417–425. [CrossRef]

- Sazonova, E.V.; Petrichuk, S.V.; Kopeina, G.S.; Zhivotovsky, B. A link between mitotic defects and mitotic catastrophe: detection and cell fate. Biol Direct 2021, 16, 25. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.H.; Jackson, S.; Seaman, M.; Brown, K.; Kempkes, B.; Hibshoosh, H.; Levine, B. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nature 1999, 402, 672–6. [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Jin, S.; Yang, C.; Levine, A.J.; Heintz, N. Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 15077–15082. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sun, H.; Che, Y.; Jiang, X. Rasfonin promotes autophagy and apoptosis via upregulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)/JNK pathway. Mycology 2016, 7, 64–73. [CrossRef]

- Goussetis, D.J.; Altman, J.K.; Glaser, H.; McNeer, J.L.; Tallman MS, Platanias LC. Autophagy is a critical mechanism for the induction of the antileukemic effects of arsenic trioxide. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 29989–29997. [CrossRef]

- Crazzolara, R.; Bradstock, K.F.; Bendall, L.J. RAD001 (Everolimus) induces autophagy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Autophagy 2009, 5, 727–728. [CrossRef]

- Crazzolara, R.; Cisterne, A.; Thien, M.; Hewson, J.; Baraz, R.; Bradstock, K.F.; Bendall, L.J. Potentiating effects of RAD001 (Everolimus) on vincristine therapy in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2009, 113, 3297–3306. [CrossRef]

- Puissant, A.; Robert, G.; Fenouille, N.; Luciano, F.; Cassuto, J.P.; Raynaud, S.; Auberger, P. Resveratrol promotes autophagic cell death in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells via JNK-mediated p62/SQSTM1 expression and AMPK activation. Cancer Res 2010, 70, 1042–1052. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Deng, B.; Liao, Y.; Shan, L.; Yin, F.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, H.; Zuo, D.; Hua, Y.; Cai, Z. The anti-tumor effect of shikonin on osteosarcoma by inducing RIP1 and RIP3 dependent necroptosis. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 580. [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H.; Dai, Y.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y.; Jing, L.; Sun, X. Resibufogenin suppresses colorectal cancer growth and metastasis through RIP3-mediated necroptosis. J Transl Med 2018, 16, 201. [CrossRef]

- Patent CN114366750B. Application of XMU-MP-1 in preparation of medicine for preventing and/or treating immune thrombocytopenia ITP. Publication 2022-11-25.

- Stepchenko, A.G.; Ilyin, Y.V.; Georgieva, S.G.; Pankratova, E.V. Inhibition of MST1/2 Kinases of the Hippo Signaling Pathway Enhances Antitumor Chemotherapy in Hematological Cancers. Dokl Biol Sci 2025, 520, 60–63. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).