Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We model the multi-agent task allocation problem as a Markov game, where each agent functions as an independent agent, interacting continuously with its environment to iteratively improve its task allocation. Under this framework, each agent determines its actions based on local observations, facilitating coordinated and efficient task distribution across the swarm.

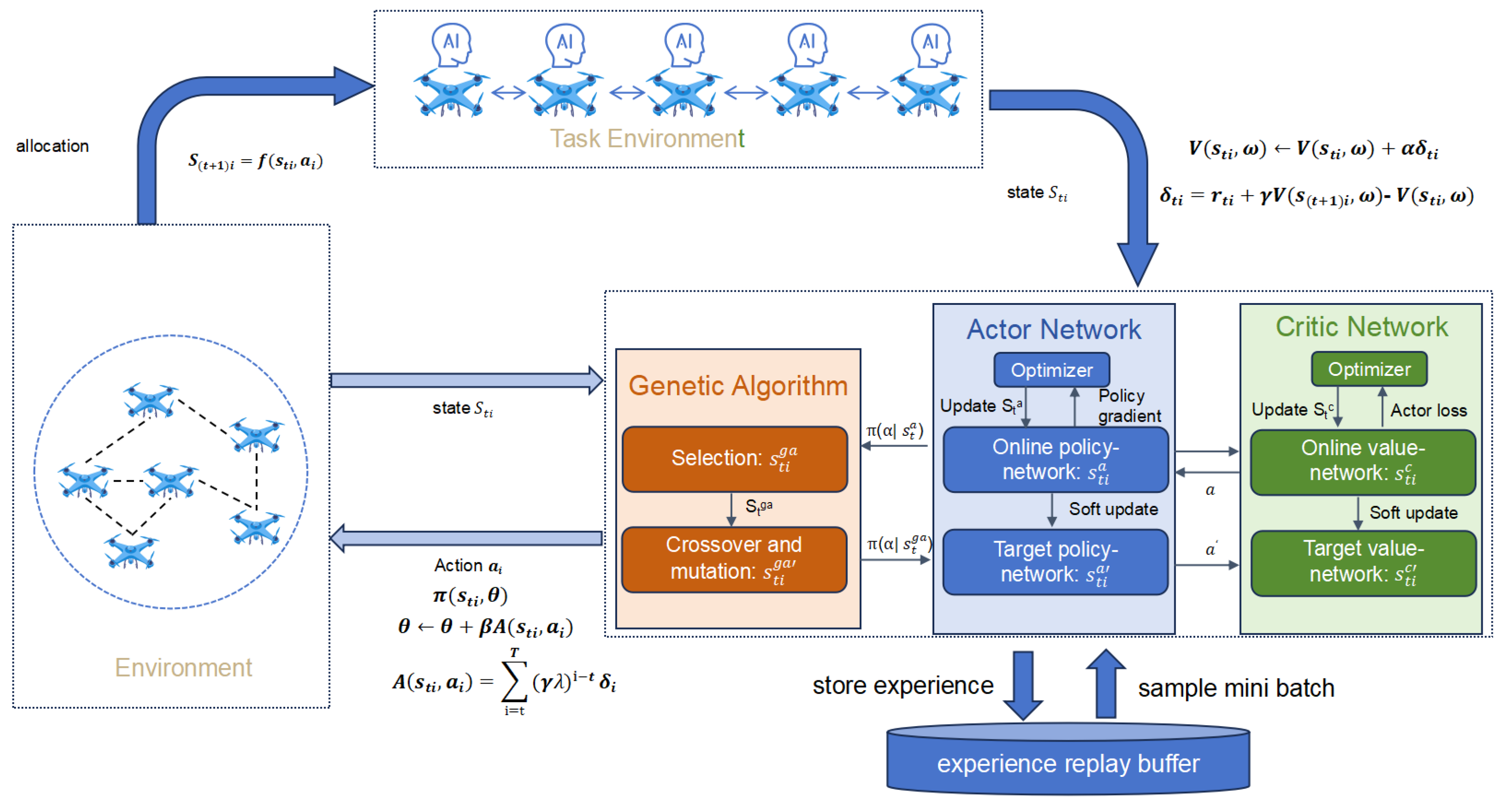

- We propose a GA-PPO reinforcement learning algorithm, which combines genetic algorithms with proximal policy optimization, incorporating an attention mechanism and adaptive learning rate. This algorithm empowers each agent to autonomously adapt to changing task demands, improving learning efficiency and facilitating effective coordination with multi-agent environments. By leveraging those features, the system optimizes resource utilization while maintaining robust performance in dynamic scenarios.

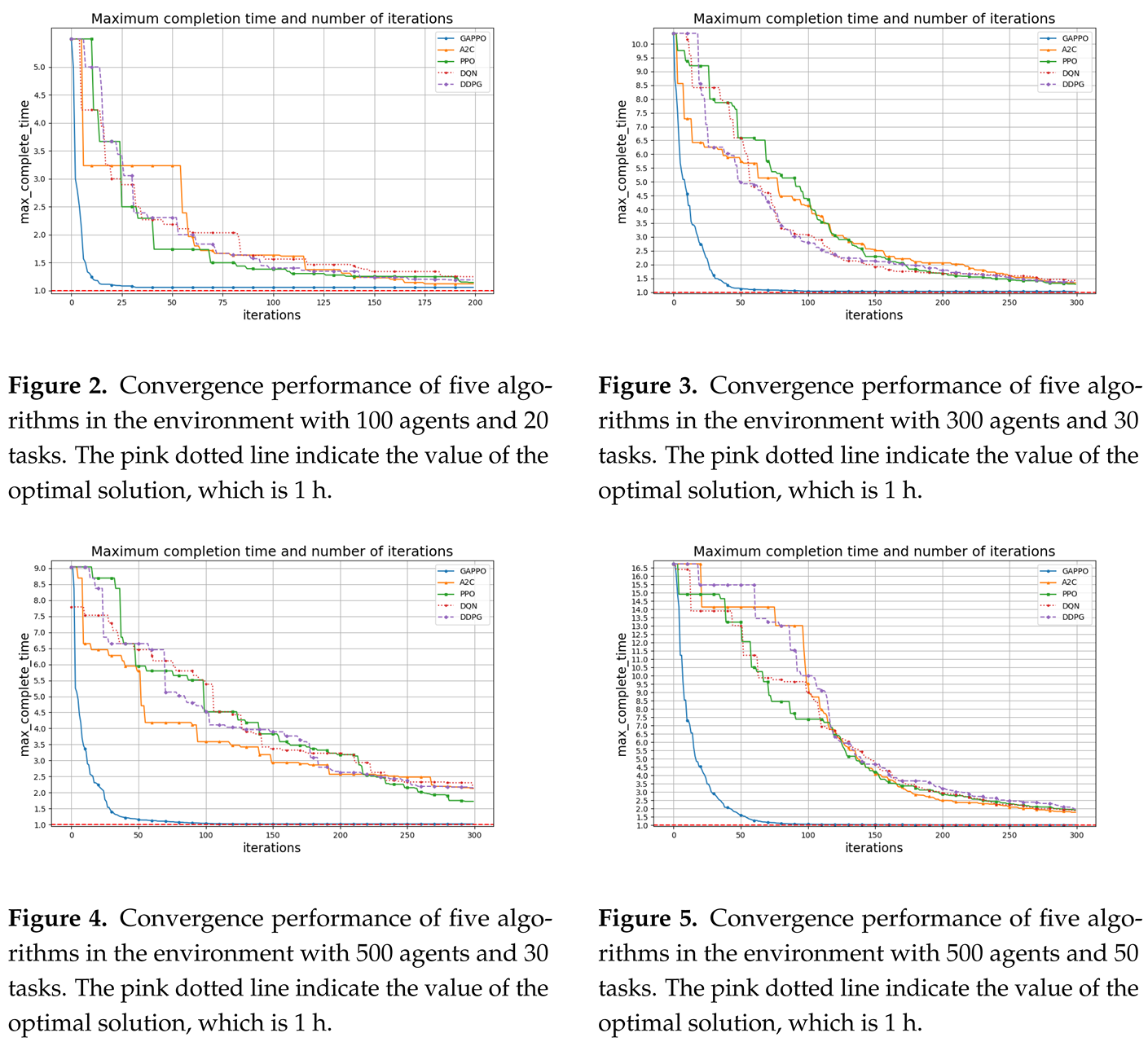

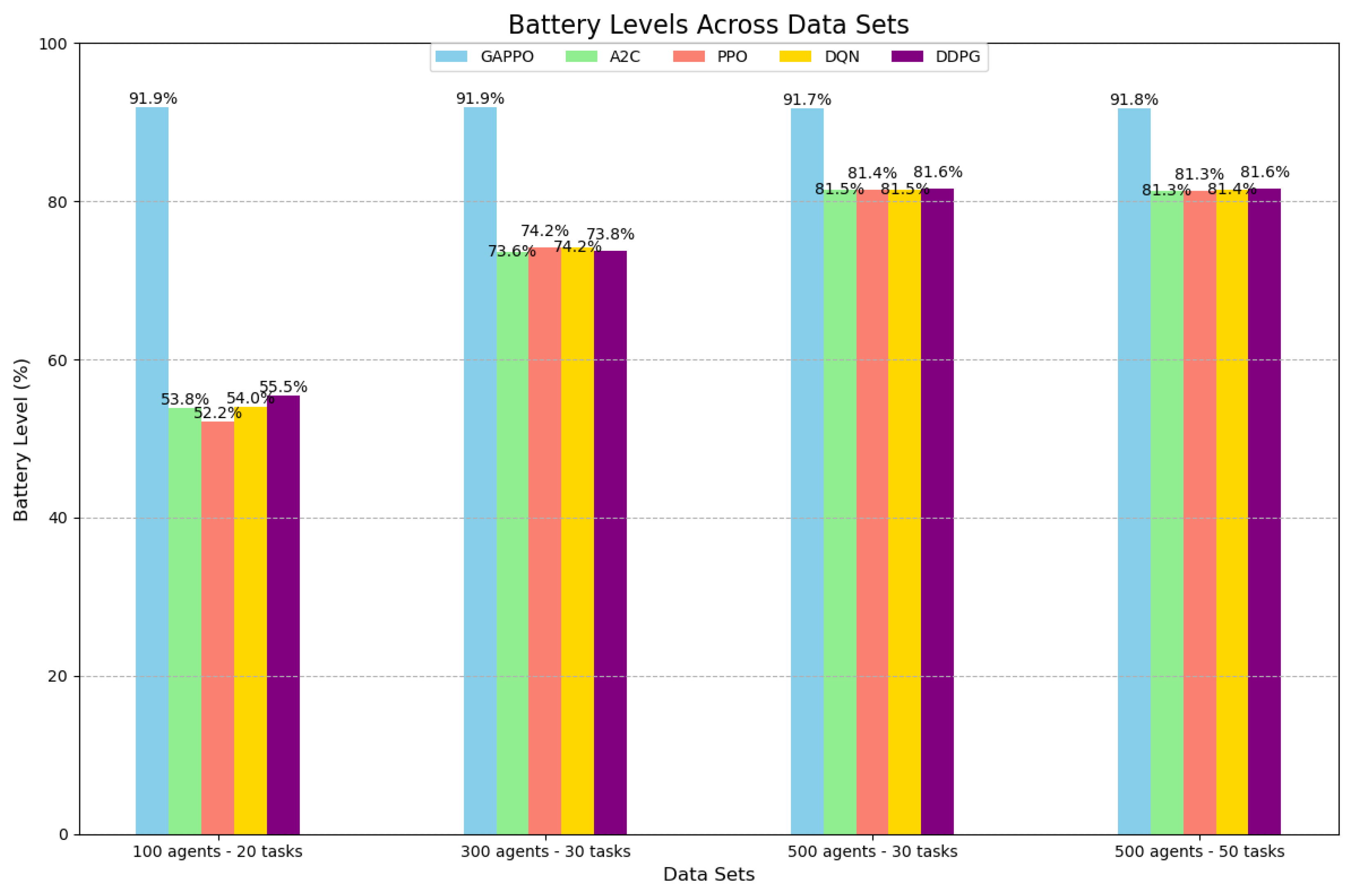

- Numerical experiments demonstrate that our proposed algorithm performs well in terms of convergence speed and scalability compared with the existing representative algorithms.

2. Problem Formulation

- Primary (Extrinsic) Task: High-quality execution of multiple operational tasks by agents, such as conducting surveillance on designated targets or performing search and rescue missions in critical scenarios. Those tasks necessitate that agents autonomously assess their environments and adapt to dynamic conditions, thereby ensuring effective and efficient performance.

- Secondary (Intrinsic) Task: Evaluation of task allocation decisions. This task focuses on evaluating the effectiveness of agents’ decisions in optimizing resource utilization and enhancing operational efficiency, thereby improving the overall performance of the multi-agent system.

- State Estimation: The state information includes the positions of individual agents, an occupancy map of the environment, and the IDs of associated targets. In this multi-agent environment, the state represents the specific configuration of each agent i at time t. Each agent continuously updates its own state information through onboard sensors and communication systems, capturing details about nearby targets and obstacles in the task environment. The task environment models the transition from the current state and action of a agent to the next state using the function , representing the dynamics of the environment. The comprehensive state representation, including spatial positions, environmental occupancy, and task-related details, is then input into the Actor-Critic network module, which supports policy generation and optimization for intelligent navigation and target detection by each agent.

- Task Allocation: To optimize task distribution among agents and prevent clustering around the same task, we implement a dynamic task allocation algorithm. Each agent independently evaluates available tasks based on specific criteria, including proximity, urgency, and current workload. The allocation process employs a priority-based strategy, whereby agents rank tasks and assign themselves based on their evaluations. The vital factors influencing this decision include the estimated time required to complete a task and the anticipated benefits of successful execution. In addition, agents communicate detailed task statuses, including progress updates, current allocation status, and priority changes. This information, along with relevant environmental data, is shared with nearby agents, facilitating dynamic task reallocation as conditions change or new tasks emerge. This collaborative algorithm enhances overall task coverage and enables agents to manage resources effectively while adapting to unexpected developments in the operational environment.

- Strategy: Beginning with the estimated state, each agent must determine its navigation path to optimize joint detection, mapping performance, and overall network efficacy. Initially, each agent functions as an independent learner, estimating its policy and making navigation decisions to improve local outcomes. Upon executing an action, each agent receives an instantaneous reward that reflects the effectiveness of the chosen action, facilitating an initial policy update. In collaborative scenarios, agents can exchange information with neighboring or more experienced agents, such as sharing policy gradients, which contributes to the refinement of their policies. The system employs a GAPPO strategy, allowing agents to make informed navigation decisions autonomously or in coordination with others. GAPPO utilizes attention mechanisms to selectively incorporate shared information, thereby optimizing policy performance and enhancing coordination among agents.

2.1. System Model

2.2. State Action Model

-

denotes the agent’s current state, which is a composite representation consisting of:

- -

- the agent’s location , providing the agent’s spatial position in the environment. This information is essential for determining the agent’s proximity to tasks and other agents, which influences both task allocation and collision avoidance.

- -

- task-related information, including task priorities, workload status, and the agent’s assigned task. This information allows the agent to evaluate its current workload and adjust its decisions based on the urgency and importance of tasks within its scope.

- -

- the occupancy map, encoding the spatial distribution of tasks and agents within the agent’s communication or sensing range. This map helps the agent understand its environment by providing real-time updates on the locations of other agents and tasks, enabling more informed decisions on task allocation and collaboration with other agents.

-

is the action selected by the agent in state . The action is defined as the selection of a task , where S represents the set of available tasks. Formally,where is the policy function that outputs the probability of selecting task j given the current state , and is the set of tasks within the communication or sensing range of agent i. If no tasks are feasible, the agent may choose an idle action.The policy function is learned using the Actor-Critic architecture, where the Actor is responsible for selecting actions based on the current state, while the Critic evaluates the actions taken by estimating the value function. Specifically, the Actor network takes the current state as input and outputs a probability distribution over possible actions (tasks). The policy function is expressed aswhere is the action selected by the agent at time step t, and j is a task from the set of available tasks .The Critic, on the other hand, estimates the expected cumulative reward for the agent starting from state . This is done through the value function , which represents the expected long-term reward given the current state. It is formally expressed aswhere is the reward received at time step k, and is the discount factor that determines the importance of future rewards.At each time step, the agent selects an action based on the policy by maximizing the probability of selecting a task from the set based on the current state . The interaction between the Actor and Critic helps in continuously optimizing the policy, with the Critic providing feedback on the expected rewards, guiding the Actor to improve its decision-making over time.If no feasible tasks are within the agent’s sensing or communication range, the agent may choose an idle action, which corresponds to not selecting any task. This idle action is implicitly represented within the action space, where one of the actions is designated as "idle."

- represents the reward obtained after executing action . This reward reflects the agent’s contribution to task completion, considering factors such as task importance, completion effectiveness, and collaborative efficiency with other agents.

- is the subsequent state resulting from the agent’s interaction with the environment after performing .

3. A learning Algorithm

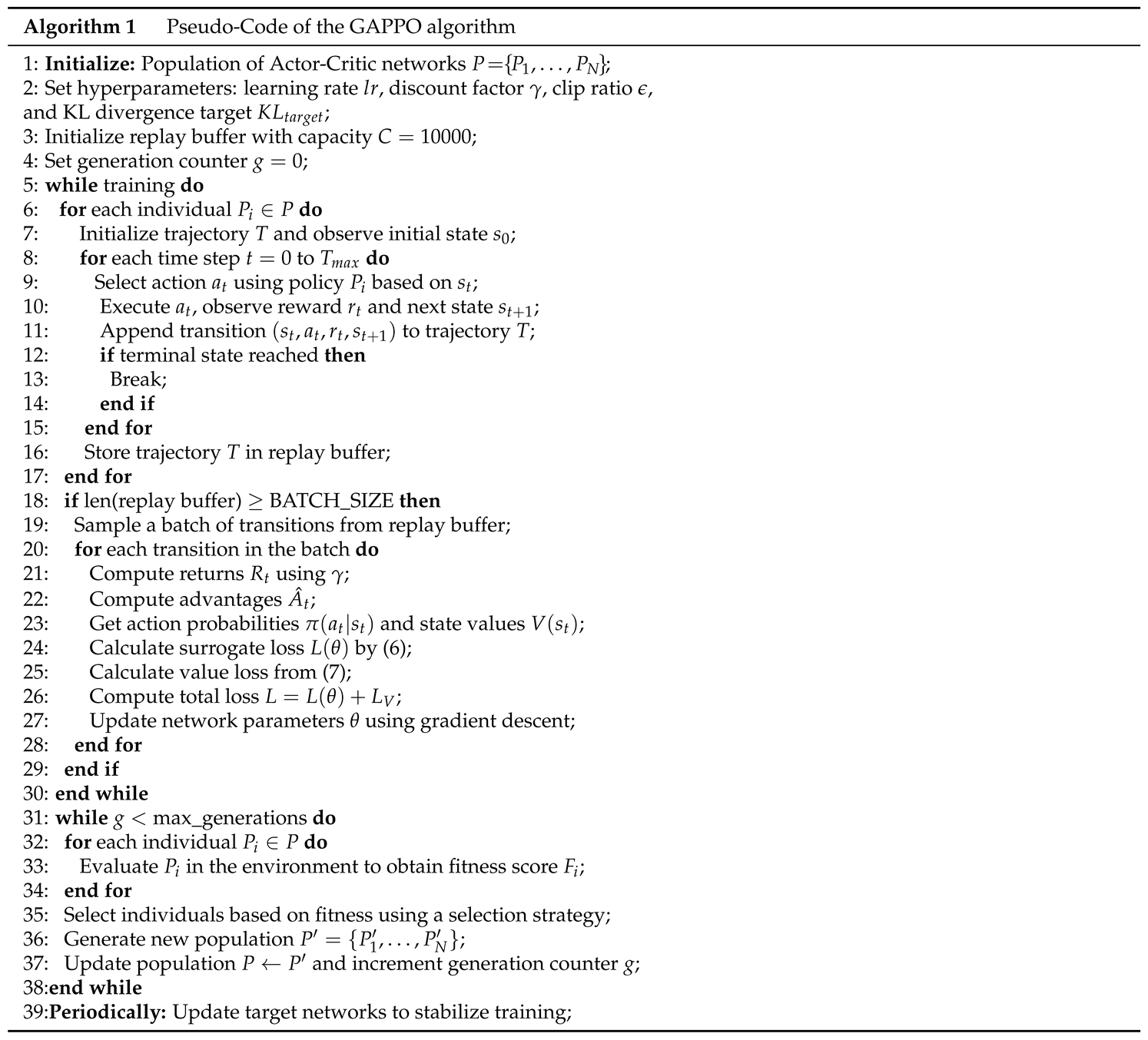

3.1. Genetic Algorithm-Enhanced Proximal Policy Optimization

4. Experimental Results

4.1. Task Allocation

- Advantage Actor-Critic (A2C) [38]: The A2C algorithm optimizes decision-making by integrating policy and value functions. The advantage function , is expressed aswhere denotes the expected return from action in state , and provides the baseline value of . This structure enhances stability in learning by reducing gradient variance.

- Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) [39]: PPO is an on-policy algorithm designed to balance exploration and exploitation by constraining policy updates, which limits excessive updates and enhances stability and sample efficiency in learning.

- Deep Q-Network (DQN) [40]: DQN is a value-based reinforcement learning algorithm that approximates the optimal action-value function using deep neural networks. Leveraging experience replay and a target network, DQN stabilizes learning and updates the Q-values aswhere is the learning rate, is the reward, and is the discount factor.

- Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) [41]: DDPG is an off-policy algorithm that addresses continuous action spaces by combining an actor-critic framework with deterministic policy gradients. The actor network directly optimizes the policy, while the critic network evaluates the action-value function, with the policy gradient update given bywhere is the action-value function, is the policy, and and are the parameters of the actor and critic networks, respectively.

5. Conclusions and the Future Work

References

- Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Xin, B.; Jia, Q.-S.; Gui, W. Multiagent dynamic task assignment based on forest fire point model. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2022, 19, 833–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Feng, B.; Bi, Y.; Yu, D. An Integrated Approach to Precedence-Constrained Multi-Agent Task Assignment and Path Finding for Mobile Robots in Smart Manufacturing. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Wu, Y.; Tempini, N. A Knowledge Flow Empowered Cognitive Framework for Decision Making With Task-Agnostic Data Regulation. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 2304–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Lei, C.; Chen, Y.; Tan, X. Cooperative Decision-Making for Mixed Traffic at an Unsignalized Intersection Based on Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, D.; Yu, Y.; Gao, L.; Wu, J.; Han, G. An attention mechanism and adaptive accuracy triple-dependent MADDPG formation control method for hybrid UAVs. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 11648–11663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhai, Z.; Li, W.; Ma, J. Target-Oriented Multi-Agent Coordination with Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, L.; Han, G. Multi-UAV collaborative dynamic task allocation method based on ISOM and attention mechanism. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 6225–6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, X.; Jin, B.; Luo, D.; Zha, H. Structured Cooperative Reinforcement Learning With Time-Varying Composite Action Space. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 44, 8618–8634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furch, A.; Lippi, M.; Carpio, R. F.; Gasparri, A. Route optimization in precision agriculture settings: A multi-Steiner TSP formulation. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2023, 20, 2551–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemidokht, H.; Rafsanjani, M. K.; Gupta, B. B.; Hsu, C.-H. Efficient and secure routing protocol based on artificial intelligence algorithms with UAV-assisted for vehicular ad hoc networks in intelligent transportation systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 4757–4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, T.; Zhu, L.; Yu, F. R.; Tang, T. Edge Intelligence in Intelligent Transportation Systems: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 8919–8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R. G.; Cota, L. P.; Euzebio, T. A. M.; et al. Unmanned aerial vehicle routing problem with mobile charging stations for assisting search and rescue missions in post-disaster scenarios. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2021, 52, 6682–6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Zhou, K.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, H. TEBChain: A trusted and efficient blockchain-based data sharing scheme in UAV-assisted IoV for disaster rescue. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2024, 21, 4119–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro, C.; Rodriguez-Ramos, A.; Bavle, H.; Carrio, A.; De la Puente, P.; Campoy, P. A fully-autonomous aerial robot for search and rescue applications in indoor environments using learning-based techniques. J. Intell. Robotic Syst. 2019, 95, 601–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; He, Z.; Su, R.; Yadav, P. K.; Teo, R.; Xie, L. Decentralized multi-UAV flight autonomy for moving convoys search and track. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2017, 25, 1480–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Qiu, C.; Zhang, Z. Sequence-to-Sequence Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Multi-UAV Task Planning in 3D Dynamic Environment. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Guo, S.; Yuan, D. Deployment and association of multiple UAVs in UAV-assisted cellular networks with the knowledge of statistical user position. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2022, 21, 6553–6567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Luo, X.; He, Z. A multi-agent collaborative environment learning method for UAV deployment and resource allocation. IEEE Trans. Signal Inf. Process. Netw. 2022, 8, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabanighazikelayeh, M.; Koyuncu, E. Optimal placement of UAVs for minimum outage probability. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 9558–9570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consul, P.; Budhiraja, I.; Garg, D.; Kumar, N.; Singh, R.; Almogren, A. S. A hybrid task offloading and resource allocation approach for digital twin-empowered UAV-assisted MEC network using federated reinforcement learning for future wireless network. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 3120–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Liang, X.; Li, Z.; Hou, Y.; Yang, A. PSE-D model-based cooperative path planning for UAV and USV systems in antisubmarine search missions. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2024, 60, 6224–6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hussaini, S.; Gregory, J. M.; Gupta, S. K. Generating Task Reallocation Suggestions to Handle Contingencies in Human-Supervised Multi-Robot Missions. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, G.; Anbalagan, S.; Ganapathisubramaniyan, A.; Selvakumar, M. S.; Bashir, A. K.; Mumtaz, S. Efficient and secured swarm pattern multi-UAV communication. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 7050–7058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, J.; Xu, K. Task-driven relay assignment in distributed UAV communication networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 11003–11017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, D.; Yu, J. Multi-UAV task assignment with parameter and time-sensitive uncertainties using modified two-part wolf pack search algorithm. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2018, 54, 2853–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Liu, Z.; Fan, M.; Wu, K. Joint task offloading and resource allocation in multi-UAV multi-server systems: An attention-based deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 11964–11978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, C. Multi-UAV cooperative task offloading and resource allocation in 5G advanced and beyond. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2024, 23, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Dou, L.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Zong, Q. Multi-agent reinforcement learning-based coordinated dynamic task allocation for heterogeneous UAVs. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 4372–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Ye, Z.; Pei, Y.; Liang, Y.-C.; Niyato, D. Multi-agent deep reinforcement learning for task offloading in UAV-assisted mobile edge computing. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2022, 21, 6949–6960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Wu, G.; Fan, M.; Cao, Z.; Pedrycz, W. DL-DRL: A double-level deep reinforcement learning approach for large-scale task scheduling of multi-UAV. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Yu, F. R.; Lin, Q.; Leung, V. C. M. Efficient resource allocation in multi-UAV assisted vehicular networks with security constraint and attention mechanism. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 2023, 22, 4802–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, N.; Ji, H.; Wang, X.; et al. Joint optimization of data acquisition and trajectory planning for UAV-assisted wireless powered Internet of Things. IEEE Trans. Mobile Comput. 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Feng, G.; Qin, S.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y. Joint UAV deployment and resource allocation: A personalized federated deep reinforcement learning approach. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 4005–4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Luo, X.; He, Z. A multi-agent collaborative environment learning method for UAV deployment and resource allocation. IEEE Trans. Signal Inf. Process. Netw. 2022, 8, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Beard, R. W. Consensus seeking in multi-agent systems under dynamically changing interaction topologies. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2005, 50, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, C. B. A dynamic virtual structure formation control for fixed-wing UAVs. 2011 9th IEEE Int. Conf. Control Autom. 2011, 627–632. [Google Scholar]

- Balch, T.; Arkin, R. C. Behavior-based formation control for multi-robot teams. IEEE Trans. Robotics Autom. 1998, 14, 926–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konda, V.; Tsitsiklis, J. Actor-critic algorithms. In Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 1999, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, M.; Liu, X.; Wen, X.; Wang, N.; Long, K. PPO-based PDACB traffic control scheme for massive IoV communications. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 1116–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Jia, X.; Chi, K.; Liu, X. DDPG-based joint time and energy management in ambient backscatter-assisted hybrid underlay CRNs. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2023, 71, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Notation | Definitions |

| the number of agents at time t | |

| m | the number of tasks |

| N | the set of agents |

| S | the set of m tasks |

| the number of agents participating in task j | |

| the task that agent i chooses | |

| the set of agents or the group for task j | |

| the work ability of agent i | |

| the workload of task j | |

| the completion time of task j | |

| T | the max completion time of all tasks |

| the strategy set of agent i | |

| A | the strategy space |

| the discount factor reflecting the rate of task reward change | |

| the communication radius of agent i j | |

| the reward of task j | |

| the battery level of the agent i | |

| the speed of the agent i | |

| the elevation angle of the agent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).