Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

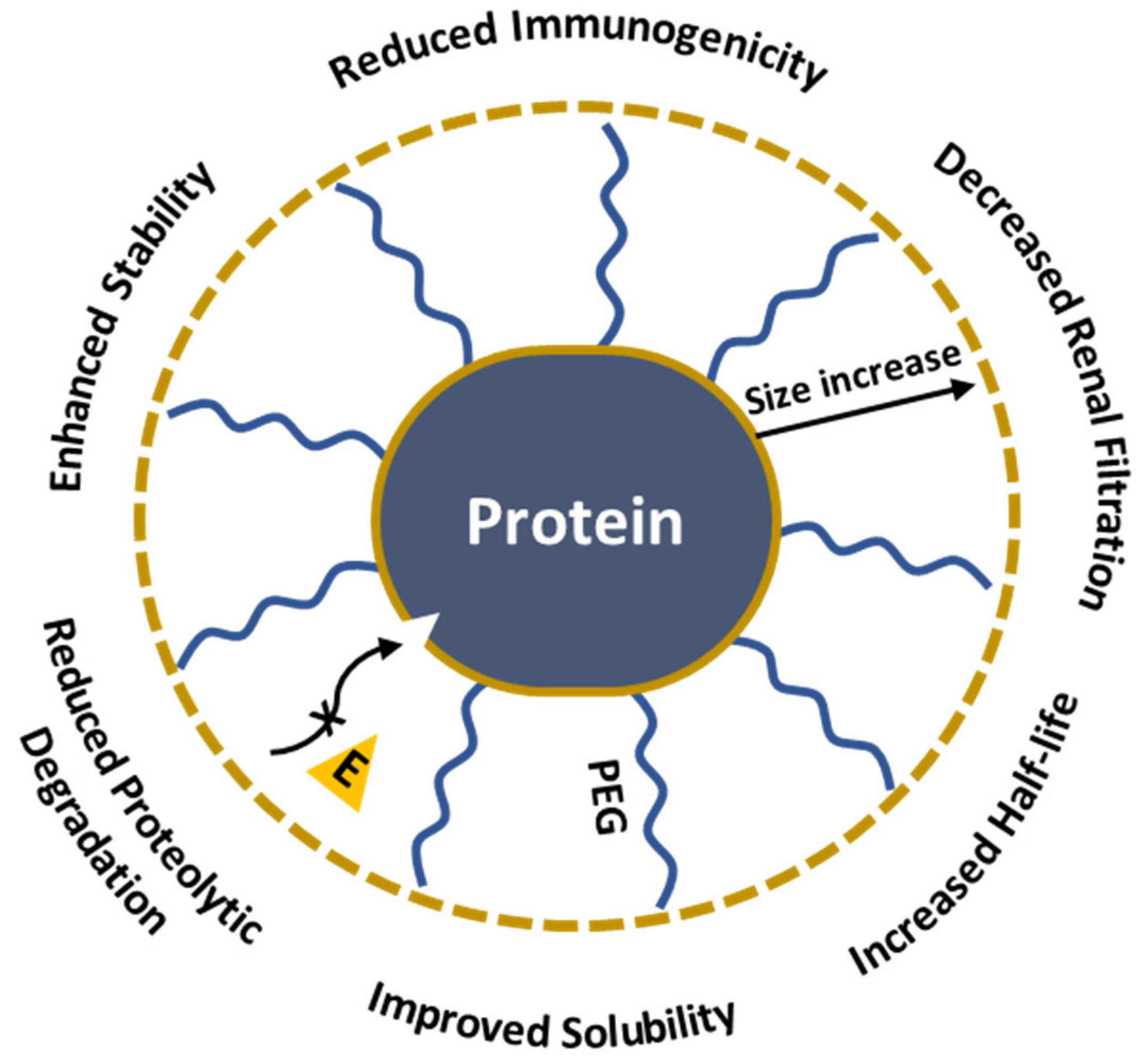

The development of effective drug delivery systems is a major challenge in cancer therapy, gene therapy, and infectious disease treatment because of its low bioavailability, rapid clearance, and toxicity towards non-targeted healthy tissues. This review discusses how PEGylation, the covalent attachment of poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), enhances the pharmacokinetic profiles of the drug-containing nanosystems through the "stealth effect" that avoids immune system detection and improves circulation times in different nano-delivery systems. The review provides an overview of the synthetic methods of PEG derivatives, their conjugation with nanoparticles, proteins, and drugs, and their characterization using modern analytical tools. The paper explores various PEGylation strategies, including covalent conjugation and self-assembly, and discusses the influence of PEG chain length, density, and conformation on drug delivery efficiency. Despite its advantages, there are several challenges associated with PEGylation such as the immunogenicity of anti-PEG responses, the potential for accelerated clearance of PEGylated drugs, reduced therapeutic efficacy, and the possibility of allergic reactions. Consequently, the balance between the benefits of PEGylation and its immunogenic risks remains a critical area of investigation.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Functionalization on PEG

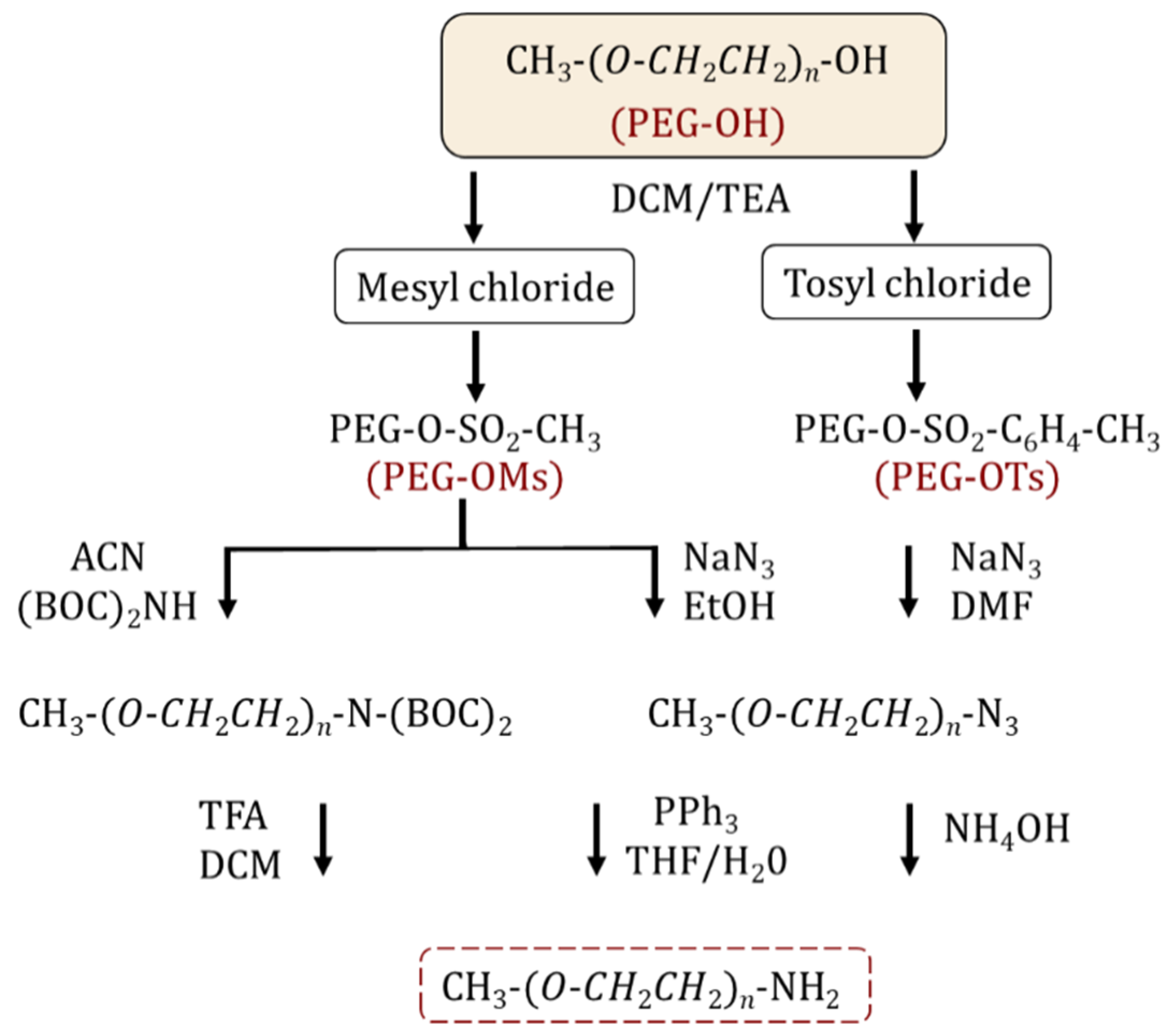

2.1. Synthesis and Functionalization of Amine and Thiol-Terminated PEGs

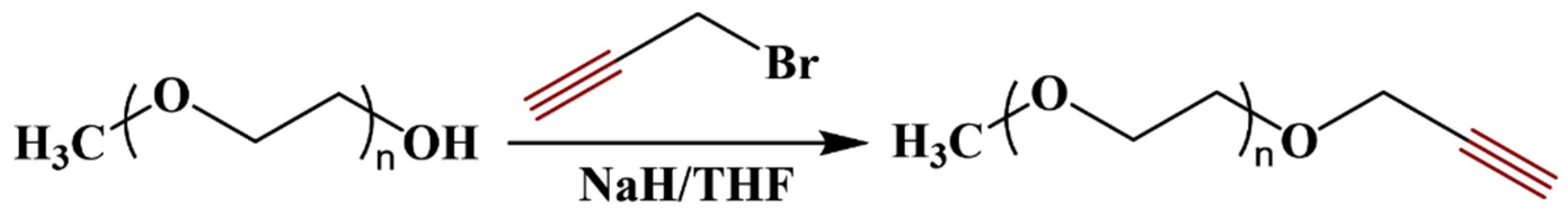

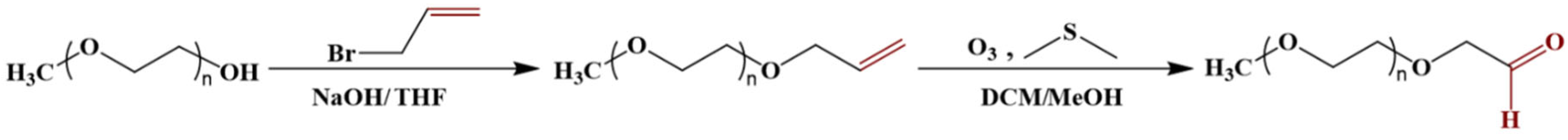

2.2. Alkyne Functionalized PEGs

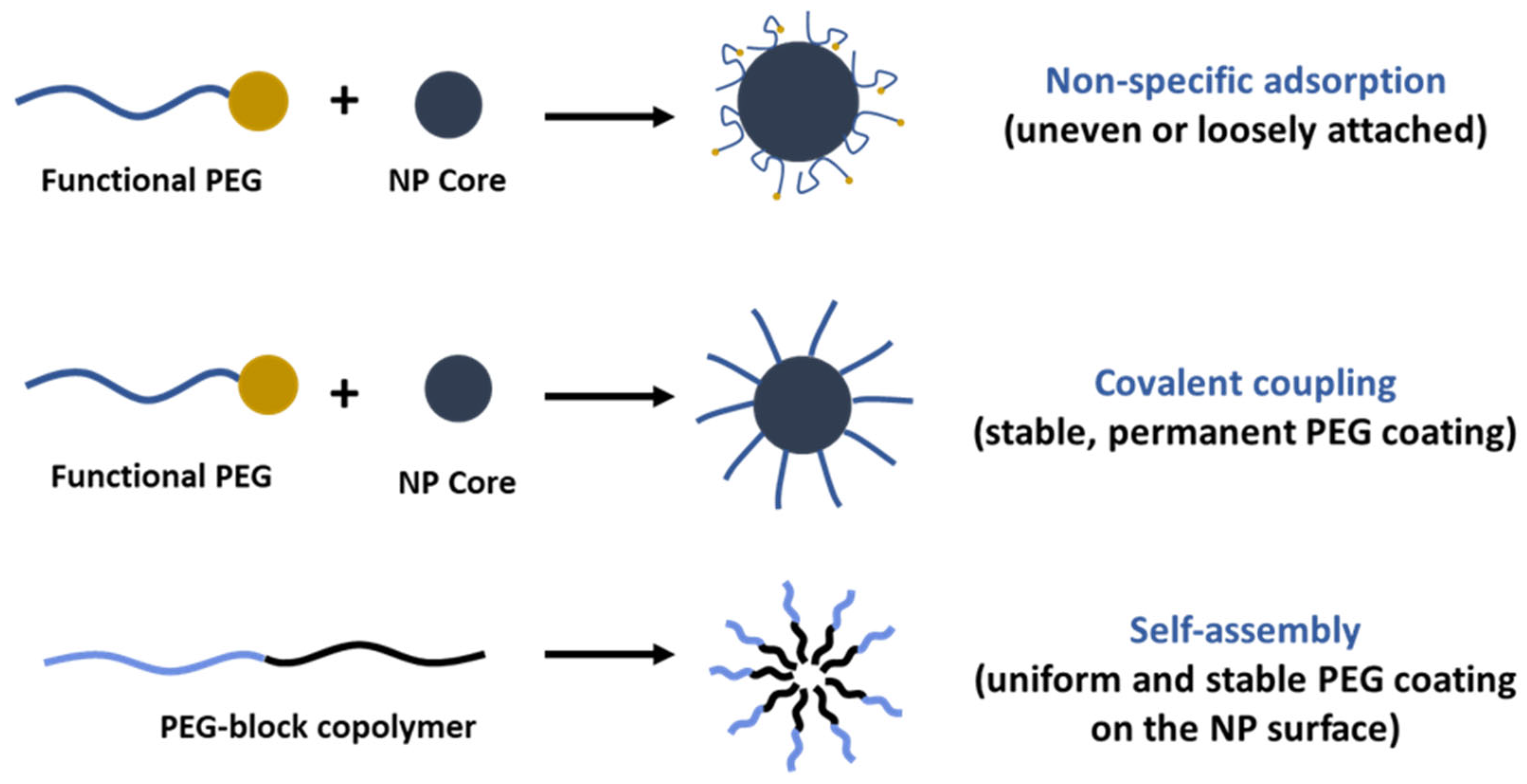

3. PEGylation Strategies for Nanosystems

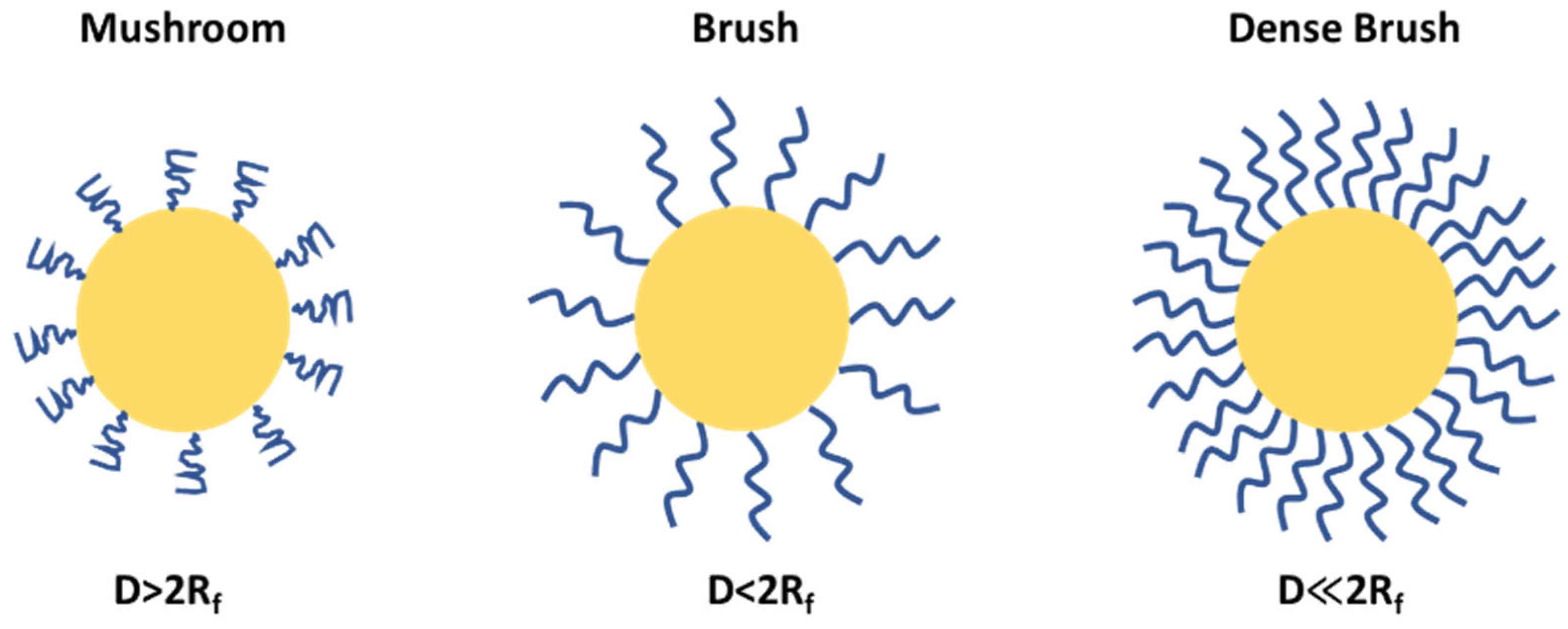

4. Flory Radius, PEG Chain Length, and Density: Influence on PEG Conformation and Biological Interactions

5. Quantification of PEG Surface Density on Nanoparticles

6. Protein PEGylation

6.1. N-terminus and Lysine PEGylation

6.2. Cysteine (Thiol) PEGylation

6.3. Carboxyl PEGylation

7. PEG Immunogenicity

8. PEGylated Nanocarriers in Cancer Therapy

8.1. PEGylated liposomes

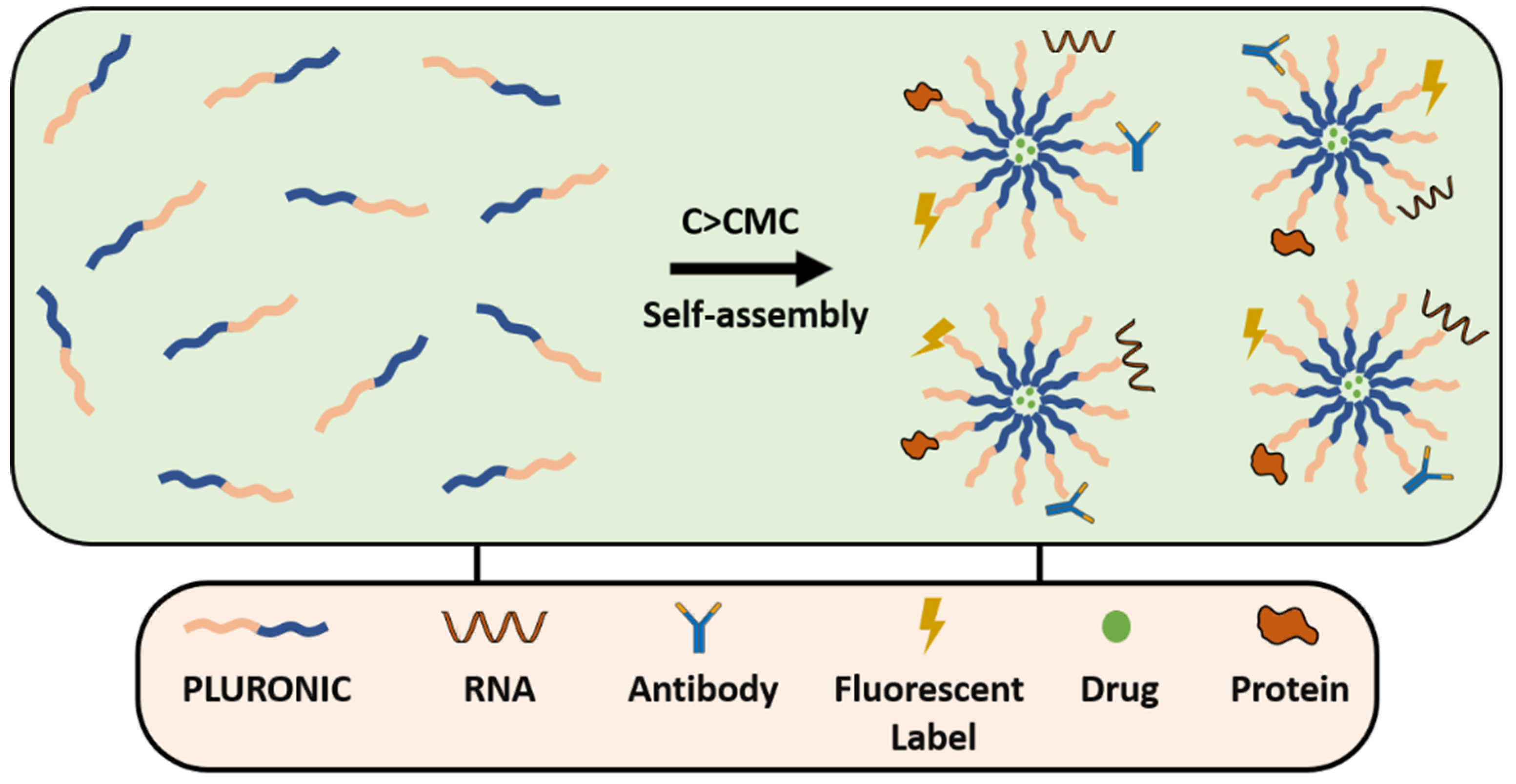

8.2. PEGylated Micelles

8.3. PEGylated Dendrimers

8.4. PEGyled Polymeric Nanoparticles

8.4.1. Methods for Preparation of PEGylated Polymeric Nanoparticles

Nanoprecipitation

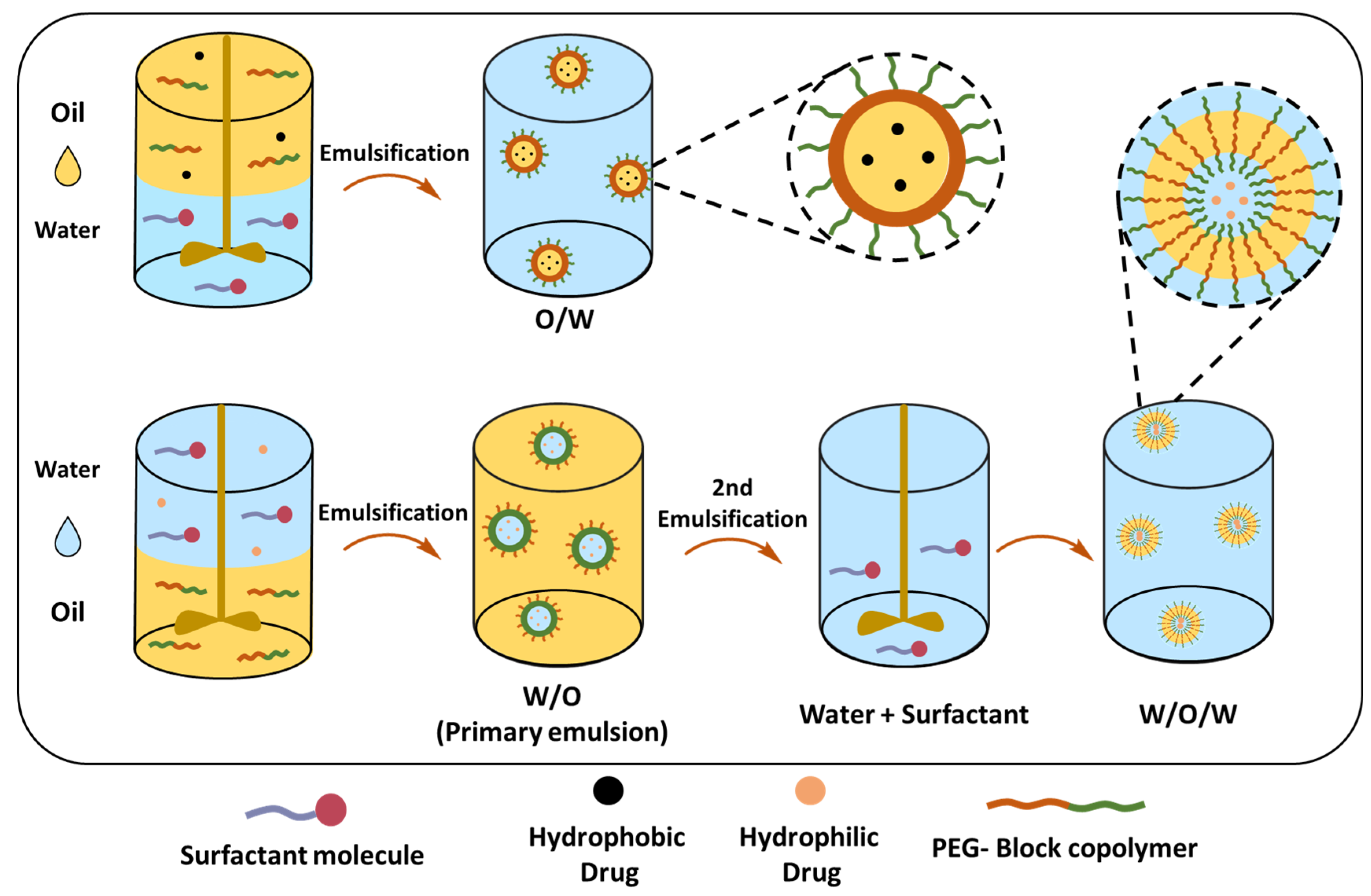

Single (O/W) and Double Emulsion (W/O/W) Solvent Evaporation Techniques

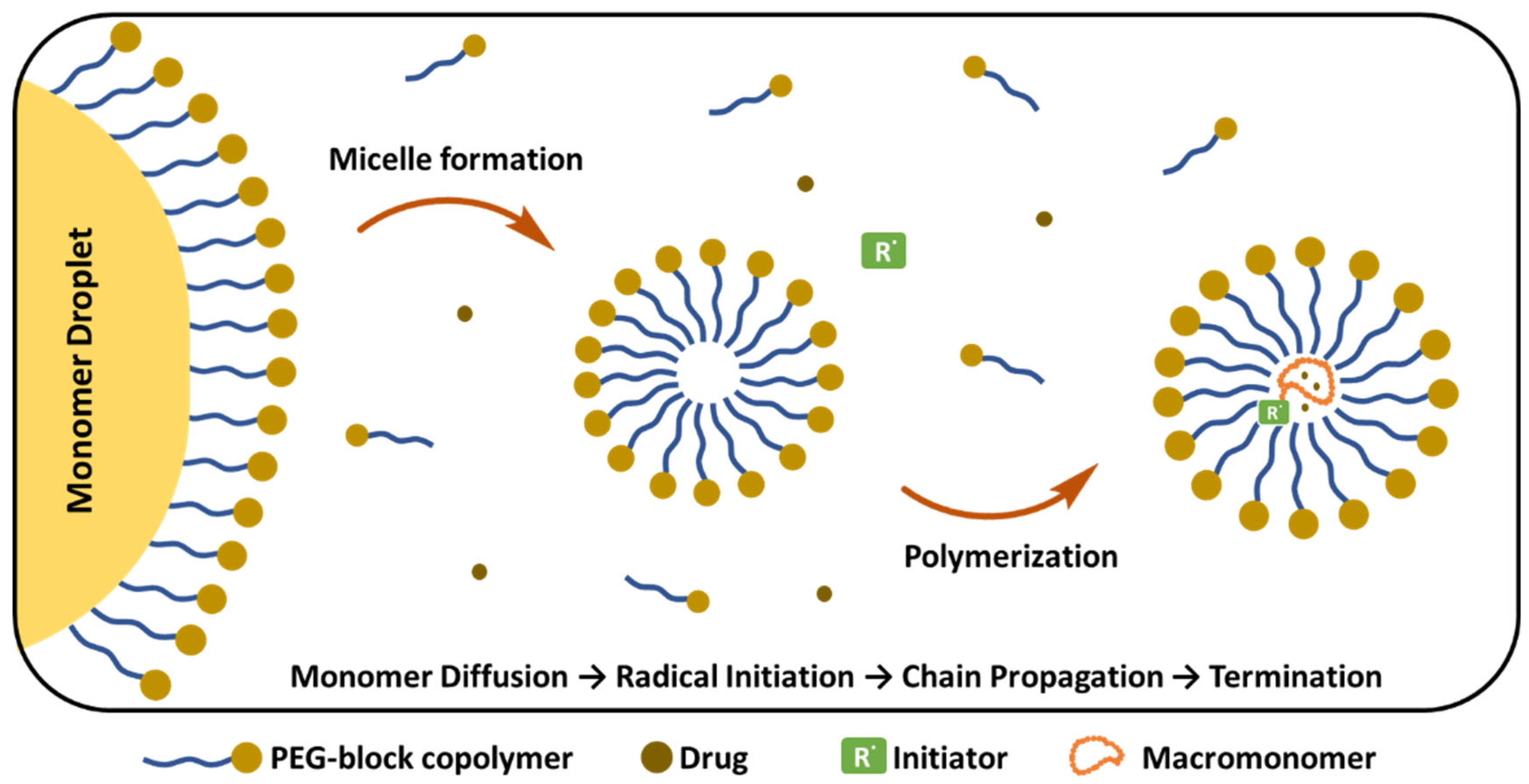

Emulsion Polymerization

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

References

- OWENSIII, D.; PEPPAS, N. Opsonization, Biodistribution, and Pharmacokinetics of Polymeric Nanoparticles. Int J Pharm 2006, 307, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobı́o, M.; Sánchez, A.; Vila, A.; Soriano, I.; Evora, C.; Vila-Jato, J.L.; Alonso, M.J. The Role of PEG on the Stability in Digestive Fluids and in Vivo Fate of PEG-PLA Nanoparticles Following Oral Administration. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2000, 18, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korake, S.; Bothiraja, C.; Pawar, A. Design, Development, and in-Vitro/in-Vivo Evaluation of Docetaxel-Loaded PEGylated Solid Lipid Nanoparticles in Prostate Cancer Therapy. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2023, 189, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Loira-Pastoriza, C.; Patil, H.P.; Ucakar, B.; Muccioli, G.G.; Bosquillon, C.; Vanbever, R. PEGylation of Paclitaxel Largely Improves Its Safety and Anti-Tumor Efficacy Following Pulmonary Delivery in a Mouse Model of Lung Carcinoma. Journal of Controlled Release 2016, 239, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Joshi, M.; Zhao, Z.; Mitragotri, S. PEGylated Therapeutics in the Clinic. Bioeng Transl Med 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belén, L.H.; Rangel-Yagui, C. de O.; Beltrán Lissabet, J.F.; Effer, B.; Lee-Estevez, M.; Pessoa, A.; Castillo, R.L.; Farías, J.G. From Synthesis to Characterization of Site-Selective PEGylated Proteins. Front Pharmacol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, T.; Tian, X.; An, W.; Wang, Z.; Han, B.; Tao, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Research Progress on the PEGylation of Therapeutic Proteins and Peptides (TPPs). Front Pharmacol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Ramadan, E.; Elsadek, N.E.; Emam, S.E.; Shimizu, T.; Ando, H.; Ishima, Y.; Elgarhy, O.H.; Sarhan, H.A.; Hussein, A.K.; et al. Polyethylene Glycol (PEG): The Nature, Immunogenicity, and Role in the Hypersensitivity of PEGylated Products. Journal of Controlled Release 2022, 351, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-M.; Cheng, T.-L.; Roffler, S.R. Polyethylene Glycol Immunogenicity: Theoretical, Clinical, and Practical Aspects of Anti-Polyethylene Glycol Antibodies. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 14022–14048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Park, J.K.; Jeong, B. Rediscovery of Poly(Ethylene Glycol)s as a Cryoprotectant for Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Biomater Res 2023, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalipsky, S.; Gilon, C.; Zilkha, A. Attachment of Drugs to Polyethylene Glycols. Eur Polym J 1983, 19, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevševar, S.; Kunstelj, M.; Porekar, V.G. PEGylation of Therapeutic Proteins. Biotechnol J 2010, 5, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-C.; Anseth, K.S. PEG Hydrogels for the Controlled Release of Biomolecules in Regenerative Medicine. Pharm Res 2009, 26, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.-C.; Raza, A.; Shih, H. PEG Hydrogels Formed by Thiol-Ene Photo-Click Chemistry and Their Effect on the Formation and Recovery of Insulin-Secreting Cell Spheroids. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 9685–9695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.M.; Struck, E.C.; Case, M.G.; Paley, M.S.; Yalpani, M.; Van Alstine, J.M.; Brooks, D.E. Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Derivatives. Journal of Polymer Science: Polymer Chemistry Edition 1984, 22, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward Semple, J.; Sullivan, B.; Vojkovsky, T.; Sill, K.N. Synthesis and Facile End-group Quantification of Functionalized PEG Azides. J Polym Sci A Polym Chem 2016, 54, 2888–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fernández, D.; Torneiro, M.; Lazzari, M. Some Guidelines for the Synthesis and Melting Characterization of Azide Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Derivatives. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woghiren, C.; Sharma, B.; Stein, S. Protected Thiol-Polyethylene Glycol: A New Activated Polymer for Reversible Protein Modification. Bioconjug Chem 1993, 4, 314–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, M.; Geng, C.; Xu, G.; Wang, S. A Scalable and Efficient Approach to High-Fidelity Amine Functionalized Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Derivatives. Polym Chem 2023, 14, 3352–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahou, R.; Wandrey, C. Versatile Route to Synthesize Heterobifunctional Poly(Ethylene Glycol) of Variable Functionality for Subsequent Pegylation. Polymers (Basel) 2012, 4, 561–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbert, D.L.; Hubbell, J.A. Conjugate Addition Reactions Combined with Free-Radical Cross-Linking for the Design of Materials for Tissue Engineering. Biomacromolecules 2001, 2, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, S.; Hooftman, G.; Schacht, E. Poly(Ethylene Glycol) with Reactive Endgroups: I. Modification of Proteins. J Bioact Compat Polym 1995, 10, 145–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.K.; Snyder, C.G.; Shields, J.D.; Smith, A.W.; Elbert, D.L. Clickable Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Microsphere-Based Cell Scaffolds. Macromol Chem Phys 2013, 214, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menger, F.M.; Zhang, H. Self-Adhesion among Phospholipid Vesicles. J Am Chem Soc 2006, 128, 1414–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, M.; Bandyopadhyay, D.; Singh, R.P.; Harde, H.; Kumar, S.; Jain, S. Orthogonal Biofunctionalization of Magnetic Nanoparticles via “Clickable” Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Silanes: A “Universal Ligand” Strategy to Design Stealth and Target-Specific Nanocarriers. J Mater Chem 2012, 22, 24652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, M.; Geng, C.; Xu, G.; Wang, S. A Scalable and Efficient Approach to High-Fidelity Amine Functionalized Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Derivatives. Polym Chem 2023, 14, 3352–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahou, R.; Wandrey, C. Versatile Route to Synthesize Heterobifunctional Poly(Ethylene Glycol) of Variable Functionality for Subsequent Pegylation. Polymers (Basel) 2012, 4, 561–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.J.; Brash, J.L. Synthesis and Characterization of Thiol-terminated Poly(Ethylene Oxide) for Chemisorption to Gold Surface. J Appl Polym Sci 2003, 90, 594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, P.; Valsesia, A.; Colpo, P.; Gilliland, D.; Ceccone, G.; Papadopoulou-Bouraoui, A.; Rauscher, H.; Reniero, F.; Guillou, C.; Rossi, F. Thiolated Polyethylene Oxide as a Non-Fouling Element for Nano-Patterned Bio-Devices. Appl Surf Sci 2007, 253, 4796–4804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüchow, M.; Fortuin, L.; Malkoch, M. Modular, Synthetic, Thiol-ene Mediated Hydrogel Networks as Potential Scaffolds for <scp>3D</Scp> Cell Cultures and Tissue Regeneration. Journal of Polymer Science 2020, 58, 3153–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, T.; Baldwin, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Kiick, K.L. Production of Heparin-Functionalized Hydrogels for the Development of Responsive and Controlled Growth Factor Delivery Systems. Journal of Controlled Release 2007, 122, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, L.D.; Tun, Z.; Sheardown, H.; Brash, J.L. Chemisorption of Thiolated Poly(Ethylene Oxide) to Gold: Surface Chain Densities Measured by Ellipsometry and Neutron Reflectometry. J Colloid Interface Sci 2005, 281, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulay, P.; Shrikhande, G.; Puskas, J.E. Synthesis of Mono- and Dithiols of Tetraethylene Glycol and Poly(Ethylene Glycol)s via Enzyme Catalysis. Catalysts 2019, 9, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, S.M.; McNelles, S.A.; Abdullahu, L.; Marozas, I.A.; Anseth, K.S.; Adronov, A. Reproducible Dendronized PEG Hydrogels via SPAAC Cross-Linking. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 4054–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, A.; Kužmová, E.; Pohl, R.; Sýkorová, V.; Vrábel, M.; Kraus, T.; Hocek, M. Trans -Cyclooctene- and Bicyclononyne-Linked Nucleotides for Click Modification of DNA with Fluorogenic Tetrazines and Live Cell Metabolic Labeling and Imaging. Bioconjug Chem 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilding, K.M.; Smith, A.K.; Wilkerson, J.W.; Bush, D.B.; Knotts, T.A.; Bundy, B.C. The Locational Impact of Site-Specific PEGylation: Streamlined Screening with Cell-Free Protein Expression and Coarse-Grain Simulation. ACS Synth Biol 2018, 7, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macias-Contreras, M.; He, H.; Little, K.N.; Lee, J.P.; Campbell, R.P.; Royzen, M.; Zhu, L. SNAP/CLIP-Tags and Strain-Promoted Azide–Alkyne Cycloaddition (SPAAC)/Inverse Electron Demand Diels–Alder (IEDDA) for Intracellular Orthogonal/Bioorthogonal Labeling. Bioconjug Chem 2020, 31, 1370–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, S.M.; McNelles, S.A.; Abdullahu, L.; Marozas, I.A.; Anseth, K.S.; Adronov, A. Reproducible Dendronized PEG Hydrogels via SPAAC Cross-Linking. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 4054–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, S.M.; Bakaic, E.; Stewart, S.A.; Hoare, T.; Adronov, A. Properties of Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Hydrogels Cross-Linked via Strain-Promoted Alkyne–Azide Cycloaddition (SPAAC). Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-C. Recent Advances in Crosslinking Chemistry of Biomimetic Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Hydrogels. RSC Adv 2015, 5, 39844–39853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Gao, H.; Fu, G.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, W. Synthesis, Characterization and Chondrocyte Culture of Polyhedral Oligomeric Silsesquioxane (POSS)-Containing Hybrid Hydrogels. RSC Adv 2016, 6, 23471–23478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzberger, J.; Leibig, D.; Langhanki, J.; Moers, C.; Opatz, T.; Frey, H. “Clickable PEG” via Anionic Copolymerization of Ethylene Oxide and Glycidyl Propargyl Ether. Polym Chem 2017, 8, 1882–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Zhong, W. Synthesis of Propargyl-Terminated Heterobifunctional Poly(Ethylene Glycol). Polymers (Basel) 2010, 2, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkersdorfer, A.M.; Jugovic, I.; Scheller, L.; Gutmann, M.; Hahn, L.; Diessner, J.; Lühmann, T.; Meinel, L. PEGylation of Human Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2024, 10, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.M. LABORATORY SYNTHESIS OF POLYETHYLENE GLYCOL DERIVATIVES. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part C 1985, 25, 325–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topchieva, I.N.; Kuzaev, A.I.; Zubov, V.P. Modification of Polyethylene Glycol. Eur Polym J 1988, 24, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, E.; Rossi, F.; Sacchetti, A. Simple and Efficient Strategy to Synthesize PEG-aldehyde Derivatives for Hydrazone Orthogonal Chemistry. Polym Adv Technol 2015, 26, 1456–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Lemmouchi, Y.; Akala, E.O.; Bakare, O. Studies on PEGylated and Drug-Loaded PAMAM Dendrimers. J Bioact Compat Polym 2005, 20, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Jiang, D.; Wang, L.; You, X.; Teng, Y.-O.; Yu, P. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel Water-Soluble Poly-(Ethylene Glycol)-10-Hydroxycamptothecin Conjugates. Molecules 2015, 20, 9393–9404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavon, O.; Pasut, G.; Moro, S.; Orsolini, P.; Guiotto, A.; Veronese, F.M. PEG–Ara-C Conjugates for Controlled Release. Eur J Med Chem 2004, 39, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.; Aucamp, M.; Ebrahim, N.; Samsodien, H. Supramolecular Assembly of Rifampicin and PEGylated PAMAM Dendrimer as a Novel Conjugate for Tuberculosis. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2021, 66, 102773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KITO, M.; MIRON, T.; WILCHEK, M.; KOJIMA, N.; OHISHI, N.; YAGI, K. A Simple and Efficient Method for Preparation of Monomethoxypolyethylene Glycol Activated with P-Nitrophenylchloroformate and Its Application to Modification of L-Asparaginase. J Clin Biochem Nutr 1996, 21, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Lemmouchi, Y.; Akala, E.O.; Bakare, O. Studies on PEGylated and Drug-Loaded PAMAM Dendrimers. J Bioact Compat Polym 2005, 20, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Ahsan, F. Synthesis and Evaluation of Pegylated Dendrimeric Nanocarrier for Pulmonary Delivery of Low Molecular Weight Heparin. Pharm Res 2009, 26, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Hao, S.-J.; Liu, Y.-D.; Hu, T.; Zhang, G.-F.; Zhang, X.; Qi, Q.-S.; Ma, G.-H.; Su, Z.-G. PEGylation Markedly Enhances the in Vivo Potency of Recombinant Human Non-Glycosylated Erythropoietin: A Comparison with Glycosylated Erythropoietin. Journal of Controlled Release 2010, 145, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nojima, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Abe, F.; Shiga, T.; Takeuchi, T.; Sugiyama, A.; Shimizu, H.; Sato, A. Lactoferrin Conjugated with 40-KDa Branched Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Has an Improved Circulating Half-Life. Pharm Res 2009, 26, 2125–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.H.P.M.; Feitosa, V.A.; Meneguetti, G.P.; Carretero, G.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Ventura, S.P.M.; Rangel-Yagui, C.O. Lysine-PEGylated Cytochrome C with Enhanced Shelf-Life Stability. Biosensors (Basel) 2022, 12, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javid, A.; Ahmadian, S.; Saboury, A.A.; Kalantar, S.M.; Rezaei-Zarchi, S.; Shahzad, S. Biocompatible APTES–PEG Modified Magnetite Nanoparticles: Effective Carriers of Antineoplastic Agents to Ovarian Cancer. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2014, 173, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.-M.; Lau, J.Y.-N.; Fok, M.; Yeung, Y.-K.; Fok, S.-P.; Zhang, S.; Ye, P.; Zhang, K.; Li, X.; Li, J.; et al. Preclinical Evaluation of the Mono-PEGylated Recombinant Human Interleukin-11 in Cynomolgus Monkeys. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2018, 342, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soderquist, R.G.; Milligan, E.D.; Sloane, E.M.; Harrison, J.A.; Douvas, K.K.; Potter, J.M.; Hughes, T.S.; Chavez, R.A.; Johnson, K.; Watkins, L.R.; et al. PEGylation of Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor for Preserved Biological Activity and Enhanced Spinal Cord Distribution. J Biomed Mater Res A 2009, 91A, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, D. Acrylate-Based PEG Hydrogels with Ultrafast Biodegradability for 3D Cell Culture. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 6195–6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almany, L.; Seliktar, D. Biosynthetic Hydrogel Scaffolds Made from Fibrinogen and Polyethylene Glycol for 3D Cell Cultures. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 2467–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, D.; Nie, J. Chitosan/Polyethylene Glycol Diacrylate Films as Potential Wound Dressing Material. Int J Biol Macromol 2008, 43, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Kar, R.; Chwatko, M.; Shoga, E.; Cosgriff-Hernandez, E. High Porosity <scp>PEG</Scp> -based Hydrogel Foams with Self-tuning Moisture Balance as Chronic Wound Dressings. J Biomed Mater Res A 2023, 111, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, Z.; Guan, G.; Lu, Z.; Yan, S.; Du, A.; Wang, L.; Li, Q. Polyethylene Glycol Diacrylate Scaffold Filled with Cell-Laden Methacrylamide Gelatin/Alginate Hydrogels Used for Cartilage Repair. J Biomater Appl 2022, 36, 1019–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Pan, X.; Hu, H.; Xu, Y.; Wu, C. N-Terminal Site-Specific PEGylation Enhances the Circulation Half-Life of Thymosin Alpha 1. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2019, 49, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.-Q.; Wang, H.-B.; Lai, J.; Xu, Y.-C.; Zhang, C.; Chen, S.-Q. Site-Specific PEGylation of a Mutated-Cysteine Residue and Its Effect on Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand (TRAIL). Biomaterials 2013, 34, 9115–9123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, M.; Sahni, G.; Datta, S. Development of Site-Specific PEGylated Granulocyte Colony Stimulating Factor With Prolonged Biological Activity. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, D.H.; Rosendahl, M.S.; Smith, D.J.; Hughes, J.M.; Chlipala, E.A.; Cox, G.N. Site-Specific PEGylation of Engineered Cysteine Analogues of Recombinant Human Granulocyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor. Bioconjug Chem 2005, 16, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Waengler, C.; Lennox, R.B.; Schirrmacher, R. Preparation of Water-Soluble Maleimide-Functionalized 3 Nm Gold Nanoparticles: A New Bioconjugation Template. Langmuir 2012, 28, 5508–5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, F.; Vossmeyer, T.; Bastús, N.G.; Weller, H. Effect of the Spacer Structure on the Stability of Gold Nanoparticles Functionalized with Monodentate Thiolated Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Ligands. Langmuir 2013, 29, 9897–9908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-C.; Tai, J.-T.; Wang, H.-F.; Ho, R.-M.; Hsiao, T.-C.; Tsai, D.-H. Surface PEGylation of Silver Nanoparticles: Kinetics of Simultaneous Surface Dissolution and Molecular Desorption. Langmuir 2016, 32, 9807–9815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endres, T.K.; Beck-Broichsitter, M.; Samsonova, O.; Renette, T.; Kissel, T.H. Self-Assembled Biodegradable Amphiphilic PEG–PCL–LPEI Triblock Copolymers at the Borderline between Micelles and Nanoparticles Designed for Drug and Gene Delivery. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 7721–7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

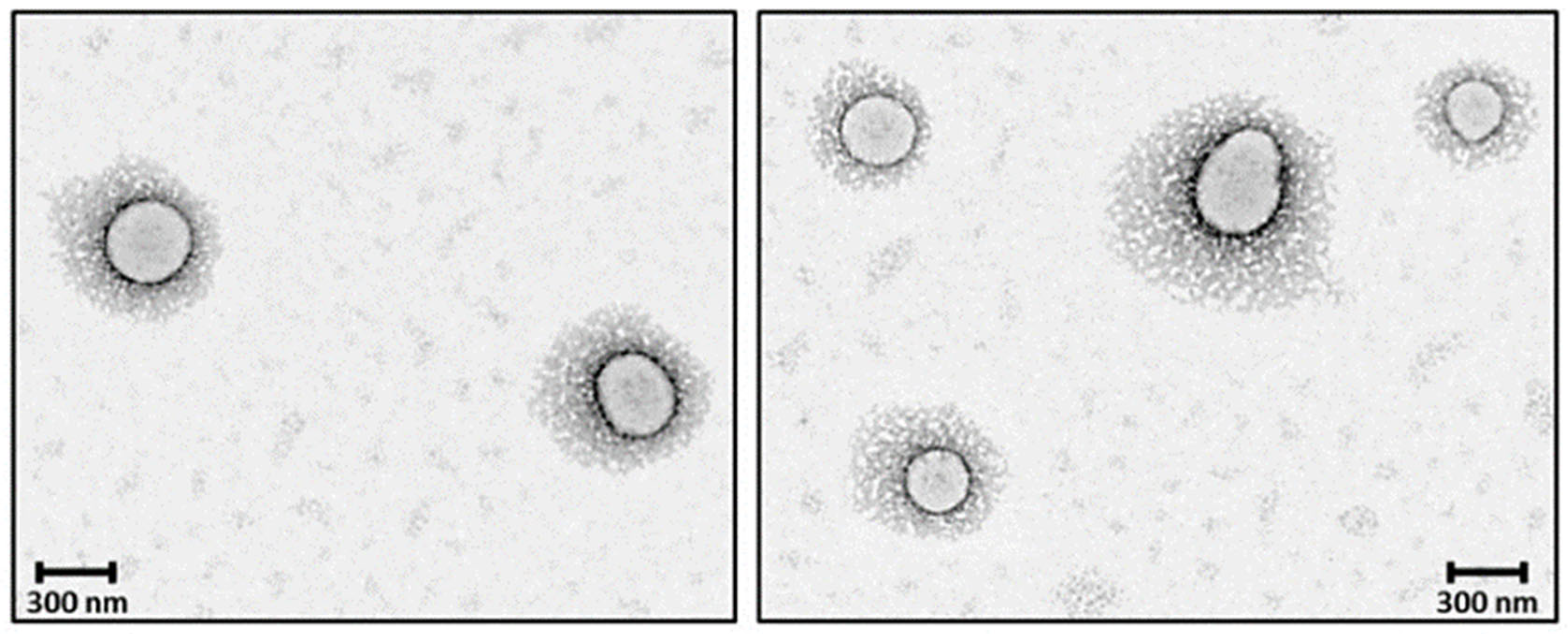

- Makharadze, D.; Kantaria, T.; Yousef, I.; del Valle, L.J.; Katsarava, R.; Puiggalí, J. PEGylated Micro/Nanoparticles Based on Biodegradable Poly(Ester Amides): Preparation and Study of the Core–Shell Structure by Synchrotron Radiation-Based FTIR Microspectroscopy and Electron Microscopy. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thierry, B.; Zimmer, L.; McNiven, S.; Finnie, K.; Barbé, C.; Griesser, H.J. Electrostatic Self-Assembly of PEG Copolymers onto Porous Silica Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2008, 24, 8143–8150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueya, Y.; Umezawa, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ichihashi, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Matsuda, T.; Takamoto, E.; Kamimura, M.; Soga, K. Effects of Hydrophilic/Hydrophobic Blocks Ratio of PEG-b-PLGA on Emission Intensity and Stability of over-1000 Nm near-Infrared (NIR-II) Fluorescence Dye-Loaded Polymeric Micellar Nanoparticles. Analytical Sciences 2022, 38, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qu, Q.; Li, J.; Zhou, S. The Effect of the Hydrophilic/Hydrophobic Ratio of Polymeric Micelles on Their Endocytosis Pathways into Cells. Macromol Biosci 2013, 13, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.M.; Peça, I.N.; Bicho, A. Impact of PEG Content on Doxorubicin Release from PLGA-Co-PEG Nanoparticles. Materials 2024, 17, 3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliceti, P.; Salmaso, S.; Elvassore, N.; Bertucco, A. Effective Protein Release from PEG/PLA Nano-Particles Produced by Compressed Gas Anti-Solvent Precipitation Techniques. Journal of Controlled Release 2004, 94, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.G.; Teng, D.Y.; Wu, Z.M.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, D.M.; Li, C.X. PEG-Grafted Chitosan Nanoparticles as an Injectable Carrier for Sustained Protein Release. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2008, 19, 3525–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torchilin, V.P. Structure and Design of Polymeric Surfactant-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Journal of Controlled Release 2001, 73, 137–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukawala, M.; Rajyaguru, T.; Chaudhari, K.; Manjappa, A.S.; Pimple, S.; Babbar, A.K.; Mathur, R.; Mishra, A.K.; Murthy, R.S.R. Investigation on Design of Stable Etoposide-Loaded PEG-PCL Micelles: Effect of Molecular Weight of PEG-PCL Diblock Copolymer on the in Vitro and in Vivo Performance of Micelles. Drug Deliv 2012, 19, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, R.; Pasche, S.; Textor, M.; Castner, D.G. Influence of PEG Architecture on Protein Adsorption and Conformation. Langmuir 2005, 21, 12327–12332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jiang, S.; Simon, J.; Paßlick, D.; Frey, M.-L.; Wagner, M.; Mailänder, V.; Crespy, D.; Landfester, K. Brush Conformation of Polyethylene Glycol Determines the Stealth Effect of Nanocarriers in the Low Protein Adsorption Regime. Nano Lett 2021, 21, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walkey, C.D.; Olsen, J.B.; Guo, H.; Emili, A.; Chan, W.C.W. Nanoparticle Size and Surface Chemistry Determine Serum Protein Adsorption and Macrophage Uptake. J Am Chem Soc 2012, 134, 2139–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Chandaroy, P.; Hui, S.W. Grafted Poly-(Ethylene Glycol) on Lipid Surfaces Inhibits Protein Adsorption and Cell Adhesion. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1997, 1326, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Jones, S.W.; Parker, C.L.; Zamboni, W.C.; Bear, J.E.; Lai, S.K. Evading Immune Cell Uptake and Clearance Requires PEG Grafting at Densities Substantially Exceeding the Minimum for Brush Conformation. Mol Pharm 2014, 11, 1250–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-L.; Du, X.-J.; Yang, J.-X.; Shen, S.; Li, H.-J.; Luo, Y.-L.; Iqbal, S.; Xu, C.-F.; Ye, X.-D.; Cao, J.; et al. The Effect of Surface Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Length on in Vivo Drug Delivery Behaviors of Polymeric Nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2018, 182, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gref, R.; Lück, M.; Quellec, P.; Marchand, M.; Dellacherie, E.; Harnisch, S.; Blunk, T.; Müller, R.H. ‘Stealth’ Corona-Core Nanoparticles Surface Modified by Polyethylene Glycol (PEG): Influences of the Corona (PEG Chain Length and Surface Density) and of the Core Composition on Phagocytic Uptake and Plasma Protein Adsorption. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2000, 18, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chithrani, D.B. Polyethylene Glycol Density and Length Affects Nanoparticle Uptake by Cancer Cells. J Nanomed Res 2014, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, D.; Colapicchioni, V.; Caracciolo, G.; Piovesana, S.; Capriotti, A.L.; Palchetti, S.; De Grossi, S.; Riccioli, A.; Amenitsch, H.; Laganà, A. Effect of Polyethyleneglycol (PEG) Chain Length on the Bio–Nano-Interactions between PEGylated Lipid Nanoparticles and Biological Fluids: From Nanostructure to Uptake in Cancer Cells. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Webster, P.; Davis, M.E. PEGylation Significantly Affects Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Trafficking of Non-Viral Gene Delivery Particles. Eur J Cell Biol 2004, 83, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Yang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, J.; Xia, Y. Quantifying the Coverage Density of Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Chains on the Surface of Gold Nanostructures. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Waengler, C.; Lennox, R.B.; Schirrmacher, R. Preparation of Water-Soluble Maleimide-Functionalized 3 Nm Gold Nanoparticles: A New Bioconjugation Template. Langmuir 2012, 28, 5508–5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Baeckmann, C.; Kählig, H.; Lindén, M.; Kleitz, F. On the Importance of the Linking Chemistry for the PEGylation of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. J Colloid Interface Sci 2021, 589, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.S.; Hlady, V.; Gölander, C.-G. The Surface Density Gradient of Grafted Poly(Ethylene Glycol): Preparation, Characterization and Protein Adsorption. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 1994, 3, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanuma, S.; Powell, C.J.; Penn, D.R. Calculations of Electron Inelastic Mean Free Paths. V. Data for 14 Organic Compounds over the 50-2000 EV Range. Surface and Interface Analysis 1994, 21, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebby, K.B.; Mansfield, E. Determination of the Surface Density of Polyethylene Glycol on Gold Nanoparticles by Use of Microscale Thermogravimetric Analysis. Anal Bioanal Chem 2015, 407, 2913–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahme, K.; Chen, L.; Hobbs, R.G.; Morris, M.A.; O’Driscoll, C.; Holmes, J.D. PEGylated Gold Nanoparticles: Polymer Quantification as a Function of PEG Lengths and Nanoparticle Dimensions. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 6085–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, D.N.; Zhu, H.; Lilierose, M.H.; Verm, R.A.; Ali, N.; Morrison, A.N.; Fortner, J.D.; Avendano, C.; Colvin, V.L. Measuring the Grafting Density of Nanoparticles in Solution by Analytical Ultracentrifugation and Total Organic Carbon Analysis. Anal Chem 2012, 84, 9238–9245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jiang, S.; Simon, J.; Paßlick, D.; Frey, M.-L.; Wagner, M.; Mailänder, V.; Crespy, D.; Landfester, K. Brush Conformation of Polyethylene Glycol Determines the Stealth Effect of Nanocarriers in the Low Protein Adsorption Regime. Nano Lett 2021, 21, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Desai, R.; Perez-Luna, V.; Karuri, N. PEGylation of Lysine Residues Improves the Proteolytic Stability of Fibronectin While Retaining Biological Activity. Biotechnol J 2014, 9, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, M.R.; Saifer, M.G.P.; Perez-Ruiz, F. PEG-Uricase in the Management of Treatment-Resistant Gout and Hyperuricemia. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2008, 60, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailon, P.; Palleroni, A.; Schaffer, C.A.; Spence, C.L.; Fung, W.-J.; Porter, J.E.; Ehrlich, G.K.; Pan, W.; Xu, Z.-X.; Modi, M.W.; et al. Rational Design of a Potent, Long-Lasting Form of Interferon: A 40 KDa Branched Polyethylene Glycol-Conjugated Interferon α-2a for the Treatment of Hepatitis C. Bioconjug Chem 2001, 12, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouzeid, A.H.; Patel, N.R.; Sarisozen, C.; Torchilin, V.P. Transferrin-Targeted Polymeric Micelles Co-Loaded with Curcumin and Paclitaxel: Efficient Killing of Paclitaxel-Resistant Cancer Cells. Pharm Res 2014, 31, 1938–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torchilin, V.P.; Levchenko, T.S.; Lukyanov, A.N.; Khaw, B.A.; Klibanov, A.L.; Rammohan, R.; Samokhin, G.P.; Whiteman, K.R. P-Nitrophenylcarbonyl-PEG-PE-Liposomes: Fast and Simple Attachment of Specific Ligands, Including Monoclonal Antibodies, to Distal Ends of PEG Chains via p-Nitrophenylcarbonyl Groups. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2001, 1511, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriraman, S.K.; Salzano, G.; Sarisozen, C.; Torchilin, V. Anti-Cancer Activity of Doxorubicin-Loaded Liposomes Co-Modified with Transferrin and Folic Acid. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2016, 105, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, M.; Zheng, J.; Rosenblat, J.; Jaffray, D.A.; Allen, C. APN/CD13-Targeting as a Strategy to Alter the Tumor Accumulation of Liposomes. Journal of Controlled Release 2011, 154, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Kate, P.; Torchilin, V.P. Matrix Metalloprotease 2-Responsive Multifunctional Liposomal Nanocarrier for Enhanced Tumor Targeting. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 3491–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Paz, J.; Saxena, M.; Delinois, L.J.; Joaquín-Ovalle, F.M.; Lin, S.; Chen, Z.; Rojas-Nieves, V.A.; Griebenow, K. Thiol-Maleimide Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Crosslinking of L-Asparaginase Subunits at Recombinant Cysteine Residues Introduced by Mutagenesis. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0197643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Lu, X.; Liu, C.; Zhong, J.; Zhou, L.; Chen, T. Site Specific PEGylation of β-Lactoglobulin at Glutamine Residues and Its Influence on Conformation and Antigenicity. Food Research International 2019, 123, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakane, T.; Pardridge, W.M. Carboxyl-Directed Pegylation of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Markedly Reduces Systemic Clearance with Minimal Loss of Biologic Activity. Pharm Res 1997, 14, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Cao, Y.; Chi, S.; Lou, D. A PEGylation Technology of L-Asparaginase with Monomethoxy Polyethylene Glycol-Propionaldehyde. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 2012, 67, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, J.A.; Rivera-Rivera, I.; Solá, R.J.; Griebenow, K. Enzymatic Activity and Thermal Stability of PEG-α-Chymotrypsin Conjugates. Biotechnol Lett 2009, 31, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettit, D.K.; Bonnert, T.P.; Eisenman, J.; Srinivasan, S.; Paxton, R.; Beers, C.; Lynch, D.; Miller, B.; Yost, J.; Grabstein, K.H.; et al. Structure-Function Studies of Interleukin 15 Using Site-Specific Mutagenesis, Polyethylene Glycol Conjugation, and Homology Modeling. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1997, 272, 2312–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghmi, A.; Mendez-Villuendas, E.; Greschner, A.A.; Liu, J.Y.; de Haan, H.W.; Gauthier, M.A. Mechanisms of Activity Loss for a Multi-PEGylated Protein by Experiment and Simulation. Mater Today Chem 2019, 12, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Lai, S.K. Anti- <scp>PEG</Scp> Immunity: Emergence, Characteristics, and Unaddressed Questions. WIREs Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2015, 7, 655–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichihara, M.; Shimizu, T.; Imoto, A.; Hashiguchi, Y.; Uehara, Y.; Ishida, T.; Kiwada, H. Anti-PEG IgM Response against PEGylated Liposomes in Mice and Rats. Pharmaceutics 2010, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Hihara, T.; Kubara, K.; Kondo, K.; Hyodo, K.; Yamazaki, K.; Ishida, T.; Ishihara, H. PEG Shedding-Rate-Dependent Blood Clearance of PEGylated Lipid Nanoparticles in Mice: Faster PEG Shedding Attenuates Anti-PEG IgM Production. Int J Pharm 2020, 588, 119792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvestre, M.; Lv, S.; Yang, L.F.; Luera, N.; Peeler, D.J.; Chen, B.-M.; Roffler, S.R.; Pun, S.H. Replacement of L-Amino Acid Peptides with D-Amino Acid Peptides Mitigates Anti-PEG Antibody Generation against Polymer-Peptide Conjugates in Mice. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 331, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, R.P.; El-Gewely, R.; Armstrong, J.K.; Garratty, G.; Richette, P. Antibodies against Polyethylene Glycol in Healthy Subjects and in Patients Treated with PEG-Conjugated Agents. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2012, 9, 1319–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Lee, W.S.; Pilkington, E.H.; Kelly, H.G.; Li, S.; Selva, K.J.; Wragg, K.M.; Subbarao, K.; Nguyen, T.H.O.; Rowntree, L.C.; et al. Anti-PEG Antibodies Boosted in Humans by SARS-CoV-2 Lipid Nanoparticle MRNA Vaccine. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 11769–11780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, A.; Bottau, P.; Calamelli, E.; Caimmi, S.; Crisafulli, G.; Franceschini, F.; Liotti, L.; Mori, F.; Paglialunga, C.; Saretta, F.; et al. Hypersensitivity to Polyethylene Glycol in Adults and Children: An Emerging Challenge. Acta Biomed 2021, 92, e2021519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münter, R.; Christensen, E.; Andresen, T.L.; Larsen, J.B. Studying How Administration Route and Dose Regulates Antibody Generation against LNPs for MRNA Delivery with Single-Particle Resolution. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2023, 29, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takata, H.; Shimizu, T.; Yamade, R.; Elsadek, N.E.; Emam, S.E.; Ando, H.; Ishima, Y.; Ishida, T. Anti-PEG IgM Production Induced by PEGylated Liposomes as a Function of Administration Route. Journal of Controlled Release 2023, 360, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Cao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Deng, C.; Wei, N.; Yang, J.; Cui, J. Accelerated Blood Clearance of Pegylated Liposomal Topotecan: Influence of Polyethylene Glycol Grafting Density and Animal Species. J Pharm Sci 2012, 101, 3864–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, T.; Harada, M.; Wang, X.Y.; Ichihara, M.; Irimura, K.; Kiwada, H. Accelerated Blood Clearance of PEGylated Liposomes Following Preceding Liposome Injection: Effects of Lipid Dose and PEG Surface-Density and Chain Length of the First-Dose Liposomes. Journal of Controlled Release 2005, 105, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifer, M.G.P.; Williams, L.D.; Sobczyk, M.A.; Michaels, S.J.; Sherman, M.R. Selectivity of Binding of PEGs and PEG-like Oligomers to Anti-PEG Antibodies Induced by MethoxyPEG-Proteins. Mol Immunol 2014, 57, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, M.R.; Williams, L.D.; Sobczyk, M.A.; Michaels, S.J.; Saifer, M.G.P. Role of the Methoxy Group in Immune Responses to MPEG-Protein Conjugates. Bioconjug Chem 2012, 23, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Wang, X.; Shimizu, T.; Nawata, K.; Kiwada, H. PEGylated Liposomes Elicit an Anti-PEG IgM Response in a T Cell-Independent Manner. Journal of Controlled Release 2007, 122, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlinger, C.; Spear, N.; Doddareddy, R.; Shankar, G.; Schantz, A. A Generic Method for the Detection of Polyethylene Glycol Specific IgG and IgM Antibodies in Human Serum. J Immunol Methods 2019, 474, 112669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozma, G.T.; Mészáros, T.; Berényi, P.; Facskó, R.; Patkó, Z.; Oláh, C.Zs.; Nagy, A.; Fülöp, T.G.; Glatter, K.A.; Radovits, T.; et al. Role of Anti-Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Antibodies in the Allergic Reactions to PEG-Containing Covid-19 Vaccines: Evidence for Immunogenicity of PEG. Vaccine 2023, 41, 4561–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klibanov, A.L.; Maruyama, K.; Torchilin, V.P.; Huang, L. Amphipathic Polyethyleneglycols Effectively Prolong the Circulation Time of Liposomes. FEBS Lett 1990, 268, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamala, M.; Palmer, B.D.; Jamieson, S.M.; Wilson, W.R.; Wu, Z. Dual PH-Sensitive Liposomes with Low PH-Triggered Sheddable PEG for Enhanced Tumor-Targeted Drug Delivery. Nanomedicine 2019, 14, 1971–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.-S.; Lim, S.-J.; Oh, Y.-K.; Kim, C.-K. PH-Sensitive, Serum-Stable and Long-Circulating Liposomes as a New Drug Delivery System. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2002, 54, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Fang, M.; Dong, J.; Xu, C.; Liao, Z.; Ning, P.; Zeng, Q. PH Sensitive Liposomes Delivering Tariquidar and Doxorubicin to Overcome Multidrug Resistance of Resistant Ovarian Cancer Cells. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2018, 170, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, A.A.; Torchilin, V.P. “Smart” Drug Carriers: PEGylated TATp-Modified PH-Sensitive Liposomes. J Liposome Res 2007, 17, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safra, T.; Muggia, F.; Jeffers, S.; Tsao-Wei, D.D.; Groshen, S.; Lyass, O.; Henderson, R.; Berry, G.; Gabizon, A. Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin (Doxil): Reduced Clinical Cardiotoxicity in Patients Reaching or Exceeding Cumulative Doses of 500 Mg/M2. Annals of Oncology 2000, 11, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosova, A.S.; Koloskova, O.O.; Nikonova, A.A.; Simonova, V.A.; Smirnov, V. V.; Kudlay, D.; Khaitov, M.R. Diversity of PEGylation Methods of Liposomes and Their Influence on RNA Delivery. Medchemcomm 2019, 10, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Kiwada, H. Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) Phenomenon upon Repeated Injection of PEGylated Liposomes. Int J Pharm 2008, 354, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Ichihara, M.; Wang, X.; Yamamoto, K.; Kimura, J.; Majima, E.; Kiwada, H. Injection of PEGylated Liposomes in Rats Elicits PEG-Specific IgM, Which Is Responsible for Rapid Elimination of a Second Dose of PEGylated Liposomes. Journal of Controlled Release 2006, 112, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Sayed, M.M.; Takata, H.; Shimizu, T.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Abu Lila, A.S.; Elsadek, N.E.; Alaaeldin, E.; Ishima, Y.; Ando, H.; Kamal, A.; et al. Hepatosplenic Phagocytic Cells Indirectly Contribute to Anti-PEG IgM Production in the Accelerated Blood Clearance (ABC) Phenomenon against PEGylated Liposomes: Appearance of an Unexplained Mechanism in the ABC Phenomenon. Journal of Controlled Release 2020, 323, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ishida, T.; Kiwada, H. Anti-PEG IgM Elicited by Injection of Liposomes Is Involved in the Enhanced Blood Clearance of a Subsequent Dose of PEGylated Liposomes. Journal of Controlled Release 2007, 119, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawant, R.R.; Jhaveri, A.M.; Koshkaryev, A.; Zhu, L.; Qureshi, F.; Torchilin, V.P. Targeted Transferrin-Modified Polymeric Micelles: Enhanced Efficacy in Vitro and in Vivo in Ovarian Carcinoma. Mol Pharm 2014, 11, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarisozen, C.; Abouzeid, A.H.; Torchilin, V.P. The Effect of Co-Delivery of Paclitaxel and Curcumin by Transferrin-Targeted PEG-PE-Based Mixed Micelles on Resistant Ovarian Cancer in 3-D Spheroids and in Vivo Tumors. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2014, 88, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajbhiye, V.; Vijayaraj Kumar, P.; Tekade, R.K.; Jain, N.K. PEGylated PPI Dendritic Architectures for Sustained Delivery of H2 Receptor Antagonist. Eur J Med Chem 2009, 44, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesharwani, P.; Jain, K.; Jain, N.K. Dendrimer as Nanocarrier for Drug Delivery. Prog Polym Sci 2014, 39, 268–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, R.K.; Gothwal, A.; Rani, S.; Nakhate, K.T.; Ajazuddin; Gupta, U. PEGylated Dendrimer Mediated Delivery of Bortezomib: Drug Conjugation versus Encapsulation. Int J Pharm 2020, 584, 119389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Bielinska, A.U.; Mecke, A.; Keszler, B.; Beals, J.L.; Shi, X.; Balogh, L.; Orr, B.G.; Baker, J.R.; Banaszak Holl, M.M. Interaction of Poly(Amidoamine) Dendrimers with Supported Lipid Bilayers and Cells: Hole Formation and the Relation to Transport. Bioconjug Chem 2004, 15, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.; Kesharwani, P.; Gupta, U.; Jain, N.K. Dendrimer Toxicity: Let’s Meet the Challenge. Int J Pharm 2010, 394, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somani, S.; Laskar, P.; Altwaijry, N.; Kewcharoenvong, P.; Irving, C.; Robb, G.; Pickard, B.S.; Dufès, C. PEGylation of Polypropylenimine Dendrimers: Effects on Cytotoxicity, DNA Condensation, Gene Delivery and Expression in Cancer Cells. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 9410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Haverstick, K.; Belcheva, N.; Han, E.; Saltzman, W.M. Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Conjugated PAMAM Dendrimer for Biocompatible, High-Efficiency DNA Delivery. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 3456–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xiong, W.; Wan, J.; Sun, X.; Xu, H.; Yang, X. The Decrease of PAMAM Dendrimer-Induced Cytotoxicity by PEGylation via Attenuation of Oxidative Stress. Nanotechnology 2009, 20, 105103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jangid, A.K.; Patel, K.; Joshi, U.; Patel, S.; Singh, A.; Pooja, D.; Saharan, V.A.; Kulhari, H. PEGylated G4 Dendrimers as a Promising Nanocarrier for Piperlongumine Delivery: Synthesis, Characterization, and Anticancer Activity. Eur Polym J 2022, 179, 111547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaudeu, S.J.; Fox, M.E.; Haidar, Y.M.; Dy, E.E.; Szoka, F.C.; Fréchet, J.M.J. PEGylated Dendrimers with Core Functionality for Biological Applications. Bioconjug Chem 2008, 19, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sideratou, Z.; Kontoyianni, C.; Drossopoulou, G.I.; Paleos, C.M. Synthesis of a Folate Functionalized PEGylated Poly(Propylene Imine) Dendrimer as Prospective Targeted Drug Delivery System. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2010, 20, 6513–6517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Jia, X. A Poly(Amidoamine) Dendrimer-Based Nanocarrier Conjugated with Angiopep-2 for Dual-Targeting Function in Treating Glioma Cells. Polym Chem 2016, 7, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, Y.; Jia, X.-R.; Du, J.; Ying, X.; Lu, W.-L.; Lou, J.-N.; Wei, Y. PEGylated Poly(Amidoamine) Dendrimer-Based Dual-Targeting Carrier for Treating Brain Tumors. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, S.; Qian, L.; Pei, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Jiang, Y. RGD-Modified PEG–PAMAM–DOX Conjugates: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies for Glioma. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2011, 79, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, H.; Jia, X.; Lu, W.-L.; Lou, J.; Wei, Y. A Dual-Targeting Nanocarrier Based on Poly(Amidoamine) Dendrimers Conjugated with Transferrin and Tamoxifen for Treating Brain Gliomas. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 3899–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OWENSIII, D.; PEPPAS, N. Opsonization, Biodistribution, and Pharmacokinetics of Polymeric Nanoparticles. Int J Pharm 2006, 307, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, X.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, C.; Tao, X.; Sheng, Y.; Xu, F. Influence of PEG Chain on the Complement Activation Suppression and Longevity in Vivo Prolongation of the PCL Biomedical Nanoparticles. Biomed Microdevices 2009, 11, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, N.M.; Nascimento, T.C.F. do; Casa, D.M.; Dalmolin, L.F.; Mattos, A.C. de; Hoss, I.; Romano, M.A.; Mainardes, R.M. Pharmacokinetics of Curcumin-Loaded PLGA and PLGA–PEG Blend Nanoparticles after Oral Administration in Rats. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2013, 101, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadi, S.; Serpooshan, V.; Tao, W.; Hamaly, M.A.; Alkawareek, M.Y.; Dreaden, E.C.; Brown, D.; Alkilany, A.M.; Farokhzad, O.C.; Mahmoudi, M. Cellular Uptake of Nanoparticles: Journey inside the Cell. Chem Soc Rev 2017, 46, 4218–4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-P.; Pei, Y.-Y.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Gu, Z.-H.; Zhou, Z.-H.; Yuan, W.-F.; Zhou, J.-J.; Zhu, J.-H.; Gao, X.-J. PEGylated PLGA Nanoparticles as Protein Carriers: Synthesis, Preparation and Biodistribution in Rats. Journal of Controlled Release 2001, 71, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O.A.A.; Badr-Eldin, S.M. Biodegradable Self-Assembled Nanoparticles of PEG-PLGA Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymer as a Promising Stealth System for Augmented Vinpocetine Brain Delivery. Int J Pharm 2020, 588, 119778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layre, A.; Couvreur, P.; Chacun, H.; Richard, J.; Passirani, C.; Requier, D.; Benoit, J.P.; Gref, R. Novel Composite Core-Shell Nanoparticles as Busulfan Carriers. Journal of Controlled Release 2006, 111, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaz, B.; del Pino, P.; Maffre, P.; Hartmann, R.; Gallego, M.; Rivera-Fernández, S.; de la Fuente, J.M.; Nienhaus, G.U.; Parak, W.J. Surface Functionalization of Nanoparticles with Polyethylene Glycol: Effects on Protein Adsorption and Cellular Uptake. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 6996–7008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, S.; Chitkara, D.; Mittal, A. Exploration and Insights into the Cellular Internalization and Intracellular Fate of Amphiphilic Polymeric Nanocarriers. Acta Pharm Sin B 2021, 11, 903–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayen, W.Y.; Kumar, N. A Systematic Study on Lyophilization Process of Polymersomes for Long-Term Storage Using Doxorubicin-Loaded (PEG)3–PLA Nanopolymersomes. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2012, 46, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Wu, Y.; Ahmad, A.; Ramzan, N.; Kayitmazer, A.B.; Zhou, X.; Xu, Y. Lyophilizable Polymer–Lipid Hybrid Nanoparticles with High Paclitaxel Loading. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2024, 7, 19194–19210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorso, A.; Musumeci, T.; Carbone, C.; Vicari, L.; Lauro, M.R.; Puglisi, G. Revisiting the Role of Sucrose in PLGA-PEG Nanocarrier for Potential Intranasal Delivery. Pharm Dev Technol 2018, 23, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Fang, G.; Gou, J.; Wang, S.; Yao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhao, Y. Lyophilization of Self-Assembled Polymeric Nanoparticles Without Compromising Their Microstructure and Their <I>In</I> <I>Vivo</I> Evaluation: Pharmacokinetics, Tissue Distribution and Toxicity. J Biomater Tissue Eng 2015, 5, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joye, I.J.; McClements, D.J. Production of Nanoparticles by Anti-Solvent Precipitation for Use in Food Systems. Trends Food Sci Technol 2013, 34, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farokhzad, O.C.; Cheng, J.; Teply, B.A.; Sherifi, I.; Jon, S.; Kantoff, P.W.; Richie, J.P.; Langer, R. Targeted Nanoparticle-Aptamer Bioconjugates for Cancer Chemotherapy in Vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 6315–6320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, X.; Gui, Z.; Zhang, L. Development of Hydrophilic Drug Encapsulation and Controlled Release Using a Modified Nanoprecipitation Method. Processes 2019, 7, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Liu, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, N. Preparation and Characterization of Cationic PLA-PEG Nanoparticles for Delivery of Plasmid DNA. Nanoscale Res Lett 2009, 4, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.K.; Mishra, P.; Jain, S.; Mishra, P.; Mishra, A.K.; Agrawal, G.P. Preparation and Characterization of HA–PEG–PCL Intelligent Core–Corona Nanoparticles for Delivery of Doxorubicin. J Drug Target 2008, 16, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, S.; Gu, F.X.; Langer, R.; Farokhzad, O.C.; Lippard, S.J. Targeted Delivery of Cisplatin to Prostate Cancer Cells by Aptamer Functionalized Pt(IV) Prodrug-PLGA–PEG Nanoparticles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 17356–17361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-López, E.; Egea, M.A.; Cano, A.; Espina, M.; Calpena, A.C.; Ettcheto, M.; Camins, A.; Souto, E.B.; Silva, A.M.; García, M.L. PEGylated PLGA Nanospheres Optimized by Design of Experiments for Ocular Administration of Dexibuprofen—in Vitro, Ex Vivo and in Vivo Characterization. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2016, 145, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, J.; Nakada, Y.; Sakurai, K.; Nakamura, T.; Takahashi, Y. Preparation of Nanoparticles Consisted of Poly(l-Lactide)–Poly(Ethylene Glycol)–Poly(l-Lactide) and Their Evaluation in Vitro. Int J Pharm 1999, 185, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Ensign, L.M.; Boylan, N.J.; Schön, A.; Gong, X.; Yang, J.-C.; Lamb, N.W.; Cai, S.; Yu, T.; Freire, E.; et al. Impact of Surface Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Density on Biodegradable Nanoparticle Transport in Mucus Ex Vivo and Distribution in Vivo. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9217–9227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, J.; Kumar Gupta, S.; Kreuter, J. Preparation of Biodegradable Cyclosporine Nanoparticles by High-Pressure Emulsification-Solvent Evaporation Process. Journal of Controlled Release 2004, 96, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vangara, K.K.; Liu, J.L.; Palakurthi, S. Hyaluronic Acid-Decorated PLGA-PEG Nanoparticles for Targeted Delivery of SN-38 to Ovarian Cancer. Anticancer Res 2013, 33, 2425–2434. [Google Scholar]

- Essa, S.; Rabanel, J.M.; Hildgen, P. Characterization of Rhodamine Loaded PEG-g-PLA Nanoparticles (NPs): Effect of Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Grafting Density. Int J Pharm 2011, 411, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, J.J.; Thulasidasan, A.K.T.; Anto, R.J.; Devika, N.C.; Ashwanikumar, N.; Kumar, G.S.V. Curcumin Entrapped Folic Acid Conjugated PLGA–PEG Nanoparticles Exhibit Enhanced Anticancer Activity by Site Specific Delivery. RSC Adv 2015, 5, 25518–25524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila, A.; Sánchez, A.; Pérez, C.; Alonso, M.J. PLA-PEG Nanospheres: New Carriers for Transmucosal Delivery of Proteins and Plasmid DNA. Polym Adv Technol 2002, 13, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-López, E.; Egea, M.A.; Davis, B.M.; Guo, L.; Espina, M.; Silva, A.M.; Calpena, A.C.; Souto, E.M.B.; Ravindran, N.; Ettcheto, M.; et al. Memantine-Loaded PEGylated Biodegradable Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Glaucoma. Small 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massadeh, S.; Alaamery, M.; Al-Qatanani, S.; Alarifi, S.; Bawazeer, S.; Alyafee, Y. Synthesis of Protein-Coated Biocompatible Methotrexate-Loaded PLA-PEG-PLA Nanoparticles for Breast Cancer Treatment. Nano Rev Exp 2016, 7, 31996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobío, M.; Gref, R.; Sánchez, A.; Langer, R.; Alonso, M.J. Stealth PLA-PEG Nanoparticles as Protein Carriers for Nasal Administration. Pharm Res 1998, 15, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babos, G.; Biró, E.; Meiczinger, M.; Feczkó, T. Dual Drug Delivery of Sorafenib and Doxorubicin from PLGA and PEG-PLGA Polymeric Nanoparticles. Polymers (Basel) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Nan, K.; Nie, G.; Chen, H. Enhanced Anti-Tumor Efficacy by Co-Delivery of Doxorubicin and Paclitaxel with Amphiphilic Methoxy PEG-PLGA Copolymer Nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 8281–8290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurnani, P.; Sanchez-Cano, C.; Abraham, K.; Xandri-Monje, H.; Cook, A.B.; Hartlieb, M.; Lévi, F.; Dallmann, R.; Perrier, S. RAFT Emulsion Polymerization as a Platform to Generate Well-Defined Biocompatible Latex Nanoparticles. Macromol Biosci 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colombo, C.; Morosi, L.; Bello, E.; Ferrari, R.; Licandro, S.A.; Lupi, M.; Ubezio, P.; Morbidelli, M.; Zucchetti, M.; D’Incalci, M.; et al. PEGylated Nanoparticles Obtained through Emulsion Polymerization as Paclitaxel Carriers. Mol Pharm 2016, 13, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupi, M.; Colombo, C.; Frapolli, R.; Ferrari, R.; Sitia, L.; Dragoni, L.; Bello, E.; Licandro, S.A.; Falcetta, F.; Ubezio, P.; et al. A Biodistribution Study of PEGylated PCL-Based Nanoparticles in C57BL/6 Mice Bearing B16/F10 Melanoma. Nanotechnology 2014, 25, 335706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, R.; Yu, Y.; Lattuada, M.; Storti, G.; Morbidelli, M.; Moscatelli, D. Controlled PEGylation of PLA-Based Nanoparticles. Macromol Chem Phys 2012, 213, 2012–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PEG Derivative | Primary Application | Reaction | Benefits |

| PEG-Amine | Protein, peptide conjugation | N-terminal, Lysine PEGylation | Increased stability and half-life [55,56,57] |

| PEG-Silane | Surface functionalization, drug delivery | Highly reactive with hydroxyl groups on surfaces | Stable surface functionalization, increased circulation time [58] |

| PEG-Aldehyde | Protein conjugation | Nucleophilic addition with hydroxyl or amine groups | Improved half-life [59,60] |

| PEG-Azide | Click chemistry | Click reaction with alkyne-functionalized molecules | High specificity, bioorthogonality |

| PEG-Acrylate | Tissue engineering and hydrogel preparation | Michael addition, radical Polymerization | Hydrogel scaffolds for 3D cell culture[61,62], wound dressing [63,64],tissue engineering [65] |

| PEG-Maleimide | Protein, drug, NP conjugation | Reacts with thiols (cysteine) in proteins, gold NP surface | Increased stability, half-life [66,67,68,69] |

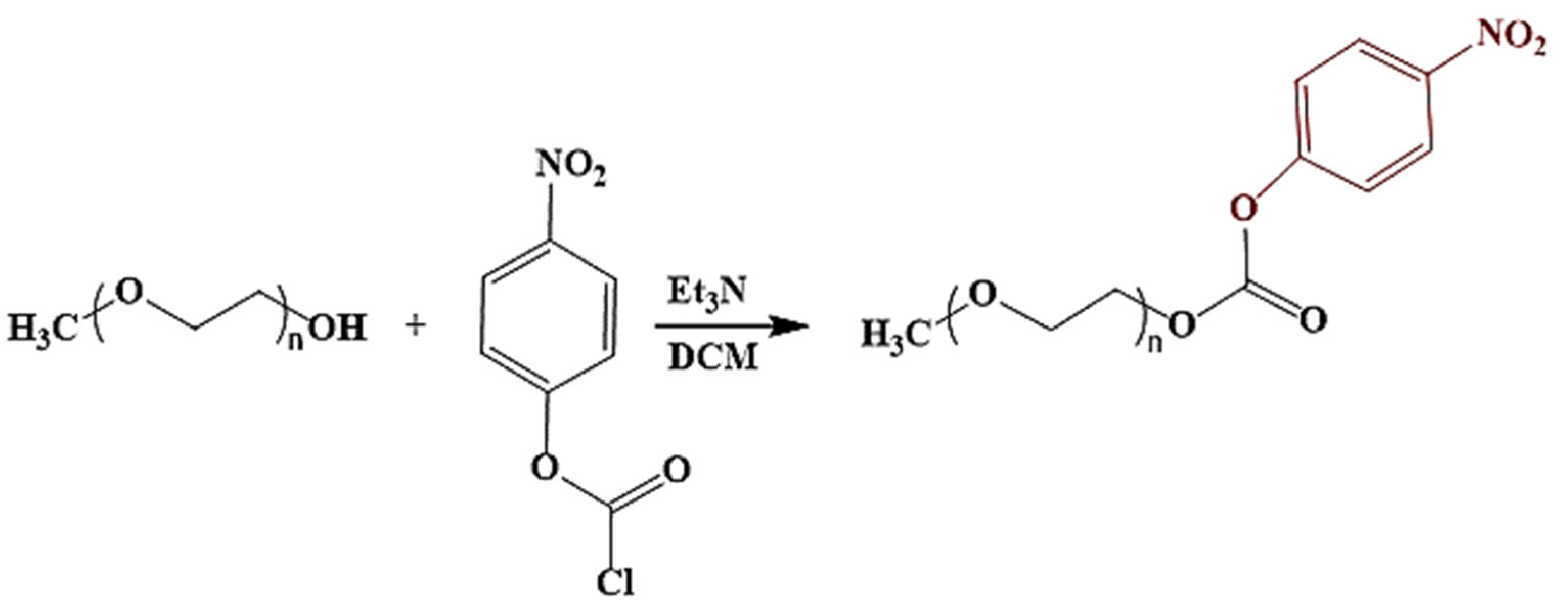

| PEG-Nitrophenyl | Protein conjugation, crosslinking | Nucleophilic substitution reactions | Rapid and simple modification of nanocarriers for protein conjugation |

| Brand Name | Active Ingredient | Cancer Type | Mechanism of Action |

| Onivyde | Irinotecan hydrochloride trihydrate | Pancreatic cancer, small cell lung cancer, colon cancer | Topoisomerase I inhibitor |

| DaunoXome | Daunorubicin | Kaposi’s sarcoma, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Topoisomerase II inhibitor |

| Doxil, Zolsketil , Caelyx, Myocet | Doxorubicin hydrochloride | Ovarian cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma, myeloid melanoma, Breast cancer | Topoisomerase II inhibitor |

| Mepact | Mifamurtide | Osteosarcoma | Activating immune cells |

| Marqibo | Vincristine sulfate | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), Hodgkin's disease, neuroblastoma | Microtubule synthesis Inhibition |

| Vyxeos | Daunorubicin, cytarabine (in combination) | Leukemia | Topoisomerase II, Nucleoside Inhibitor |

| DepoCyt | Cytarabine | Lymphomatous meningitis | Nucleoside Inhibitor |

| Polymer | Encapsulated Drug | Organic Solvent | Antisolvent | EE or DL (%) | Stabilizer | Particle Size (nm) | Activity | Refs. | |

| PEG-PLGA | Vinpocetine | Acetone | Water | 60-90 ● | PVA | 30-290 | Cerebrovascular disorder | [166] | |

| PEG-PLGA | Docetaxel | Acetonitrile | Water | - | Without stabilizer | 153.3 | Antineoplastic agent | [175] | |

| PLGA-PEG | Ciprofloxacin | DMSO | Water | 1.70-3.29 * | Without stabilizer | 174-205 | Antibiotic | [176] | |

| PEG-PLA | pEGFP | Acetone | Water | 95.56 ● | CTAB/Tween 80 |

128.9 | Plasmid vector | [177] | |

| HA–PEG–PCL | DOXORUBICIN | Acetone | Water | 92 ● | Pluronic F-68 | 95 | Antineoplastic agent | [178] | |

| Poly(isobutylcyanoacrylate/ PCL–PEG | Busulfan | Acetone | Water | 17.0 ● | Without stabilizer | 152 | Antineoplastic agent | [167] | |

| PEG-PLGA | Platinum(IV) | Acetonitrile | Water | 18.4 * | Without stabilizer | 172 | Antineoplastic agent | [179] | |

| PEG-PLGA | Dexibuprofen | Acetone | Water | 85-100 ● | PVA | 201-226 | Anti-inflammatory drug | [180] | |

| Polymer |

Encapsulated Drug |

Organic solvent |

Emulsifier |

Particle size (nm) |

Encapsulation Efficiency (%) |

Refs. |

| PLGA-PEG | Cyclosporine | DCM | PVA | 212 | 91.90 | [183] |

| PLA-PEG-PLA | Progesterone | DCM | PVA | 193-335 | 65-71 | [181] |

| PLGA-PEG | Curcumin | Ethyl Acetate/DCM | PVA | 152.37 | 73.22 | [163] |

| PLGA-PEG | SN-38 | DCM | PVA | 249.2 | 81.85 | [184] |

| PEG-PLA | Rhodamine B | DCM | PVA | 169.5 | 67.79 | [185] |

| PLGA–PEG | Curcumin | DCM | PVA | 100-200 | 52.2 | [186] |

| Polymer | Encapsulated Drug | Organic solvent | Emulsifier |

Particle size (nm) |

Encapsulation Efficiency (%) |

Refs. | |

| PLA-PEG | Tetanus toxoid | Ethyl Acetate | Sodium cholate | 196 | 33.4 | [187] | |

| PLGA-PEG | Memantine | Ethyl Acetate | PVA | 193-224 | 77-80 | [188] | |

| PLA-PEG-PLA | Methotrexate | Chloroform | PVA | 100-173 | 23-48 | [189] | |

| PLA-PEG | Tetanus toxoid | Ethyl Acetate | Gelatin | 136.8 | 35.3 | [190] | |

| PLGA-PEG | BSA | DCM | PVA | 198.1 | 48.6 | [165] | |

| PLGA-PEG | Sorafenib, Doxorubicin |

DCM/Acetone | PVA | 177.2 | 88 69 |

[191] | |

| PLGA-PEG | Paclitaxel, Doxorubicin |

DCM | PVA | 243.63 | 70.13 57.5 |

[192] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).