Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Collection and Material Preservation

2.2. Karyotyping

2.3. Genotyping by RLFP-RCR

2.4. Genotyping by Sequencing

3. Results

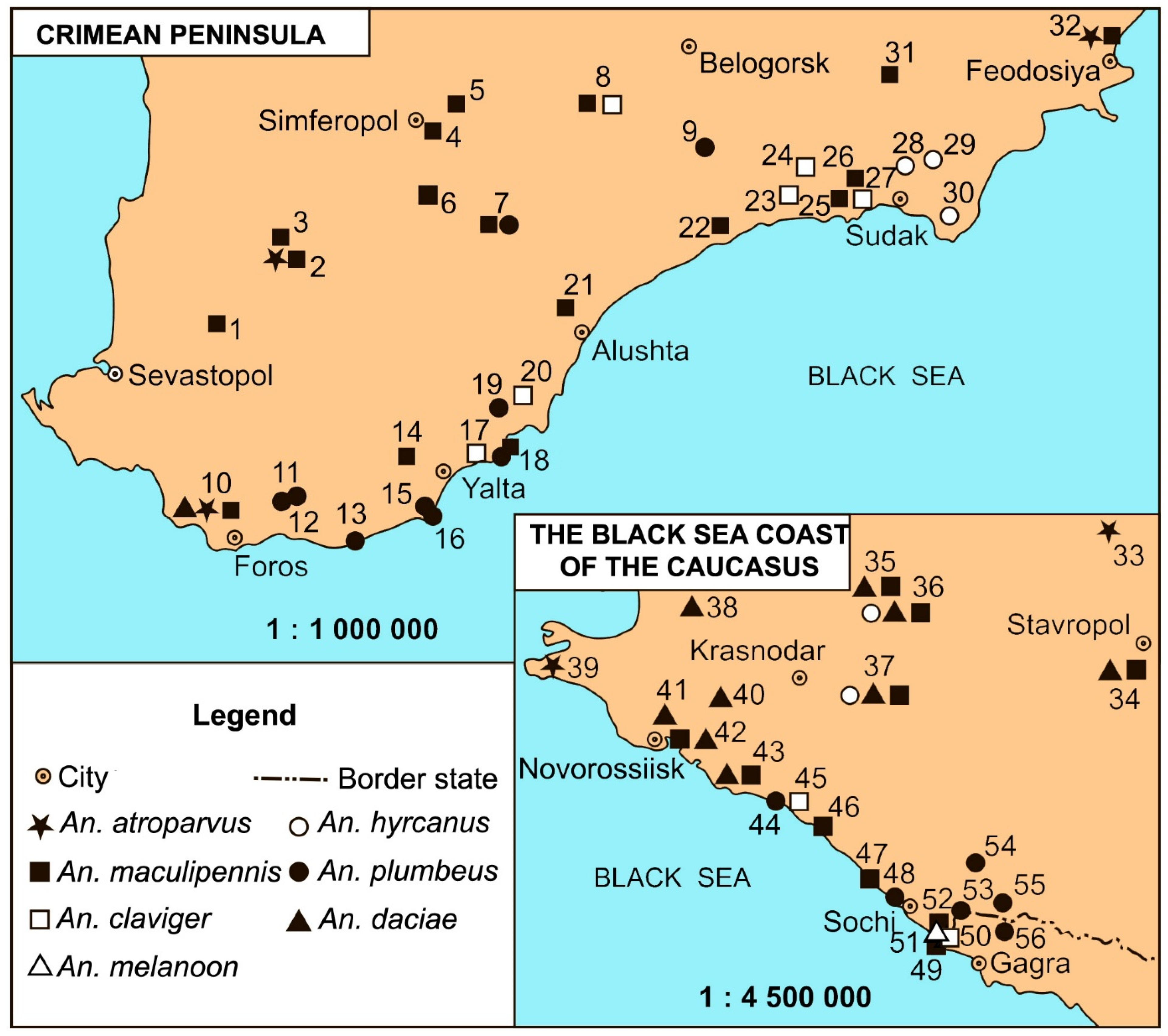

3.1. Species Composition, Geographical Distribution and Ecological Preferences

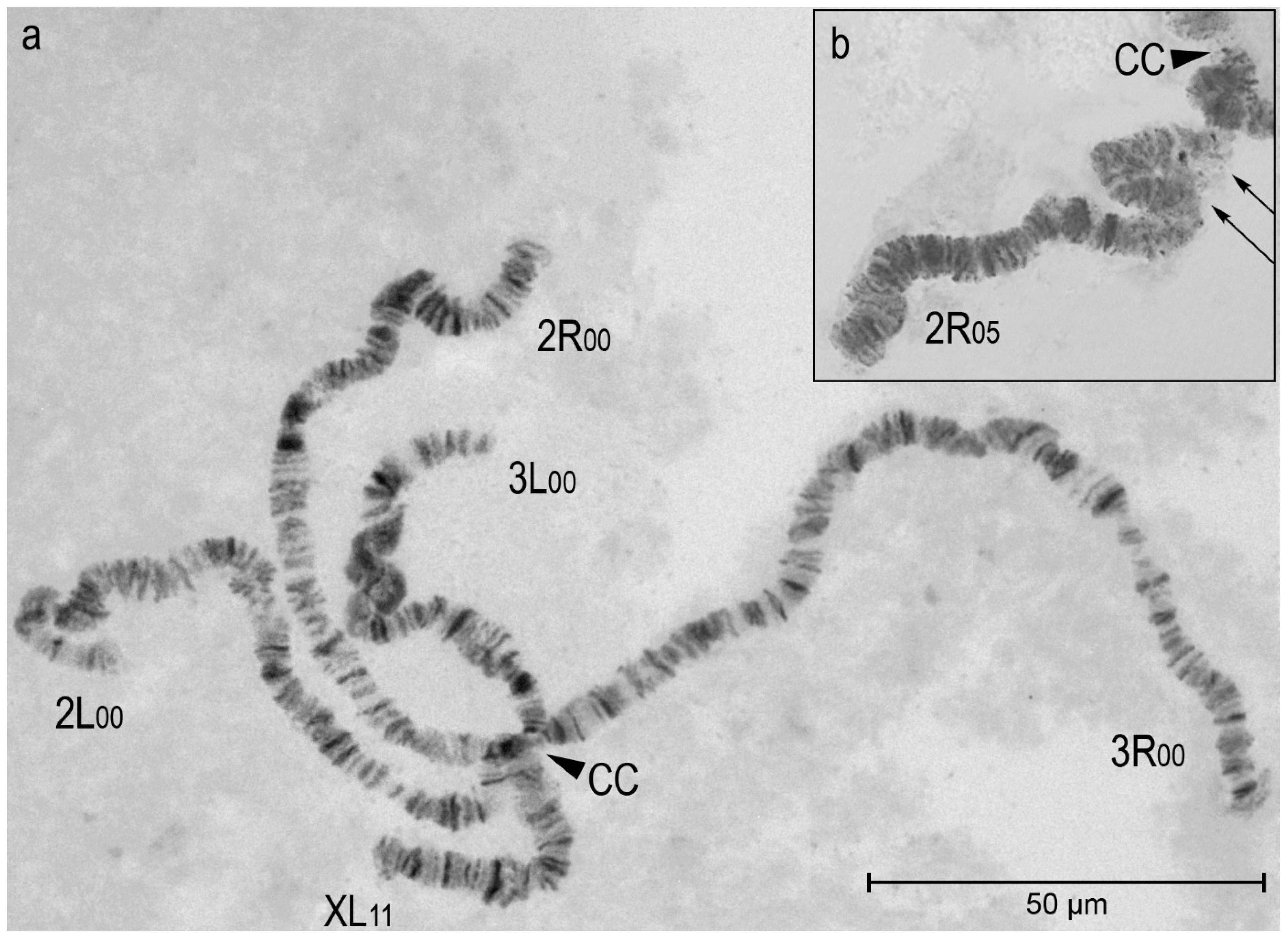

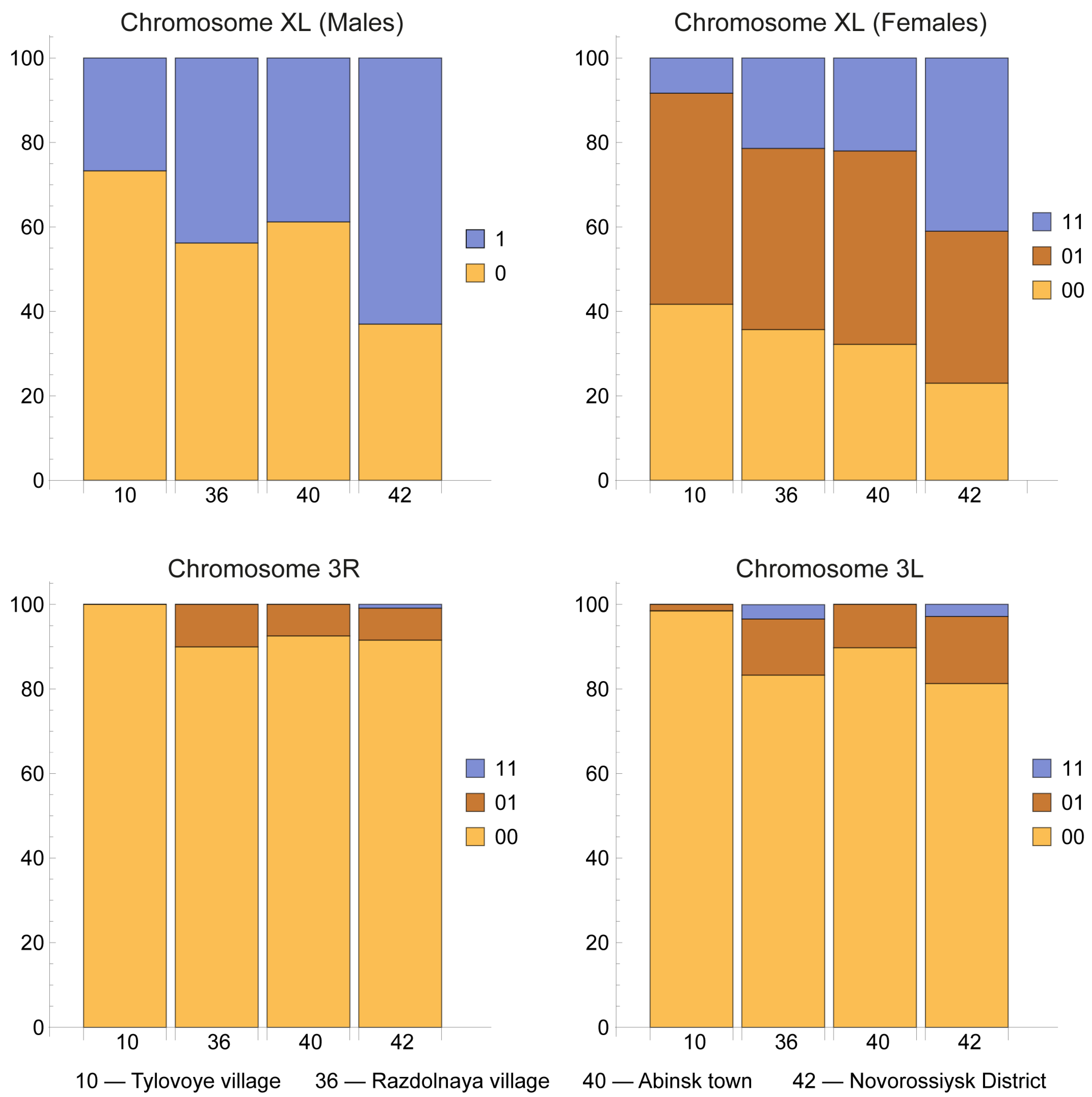

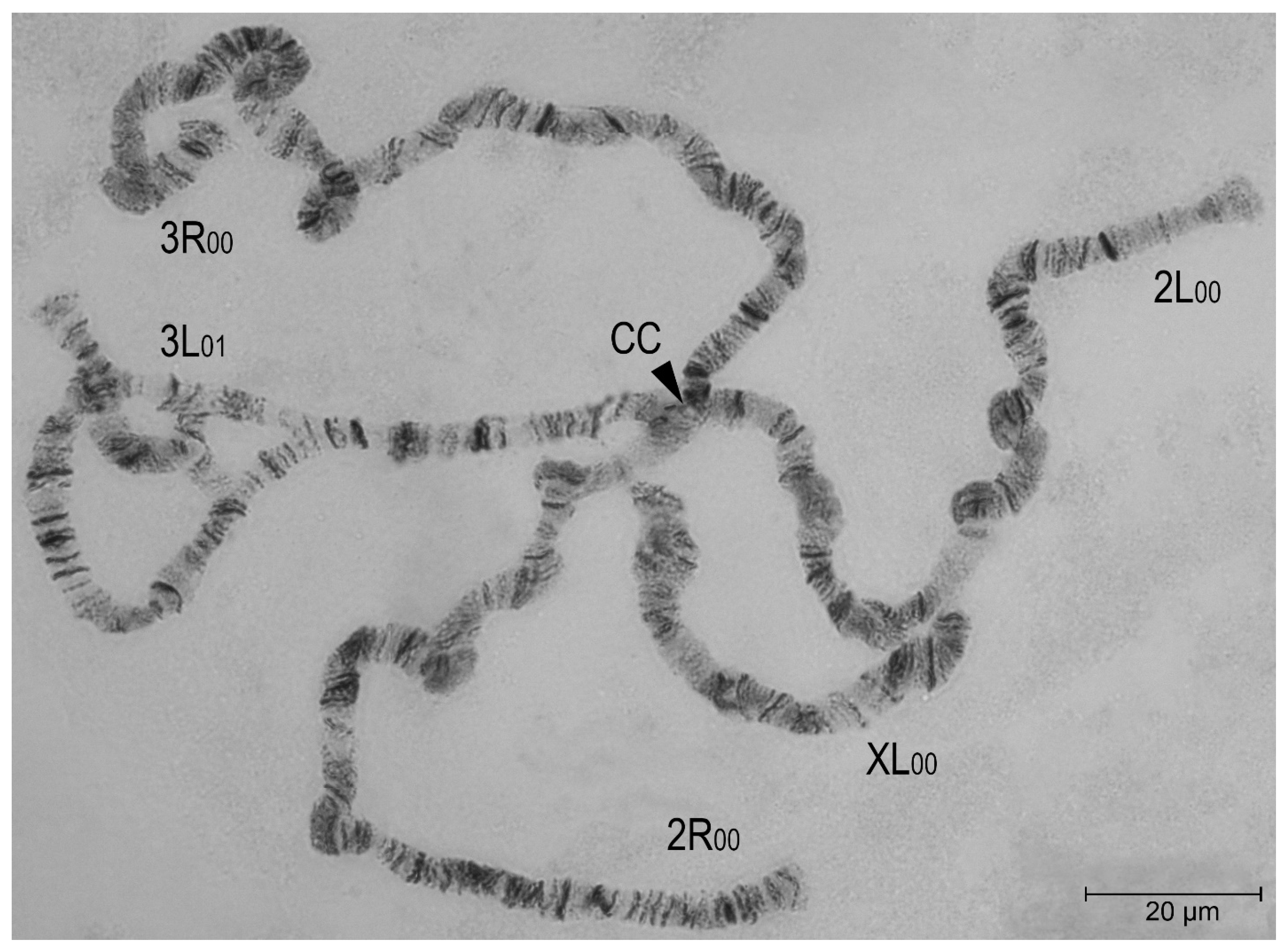

3.2. Chromosomal Inversion Polymorphism

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Mironova, L.P. Socio-ecological problems of Eastern Crimea in the past and present: causes of emergence, ways of solution. History and Modernity 2017, 1, 79–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kudaktin, A.N. Ecological threats to the resorts of the south of Russia. Fundamental researches 2006, 10, 56–58. Available online: https://fundamental-research.ru/ru/article/view?id=5473 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Rossati, A.; Bargiacchi, O.; Kroumova, V.; Zaramella, M.; Caputo, A.; et al. Climate, environment and transmission of malaria. Infez Med 2016, 24, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fischer, L.; Gultekin, N.; Kaelin, M. B.; Fehr, J.; Schlagenhauf, P. Rising temperature and its impact on receptivity to malaria transmission in Europe: A systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis 2020, 36, 101815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regional strategy: from malaria control to elimination in the WHO European Region 2006–2015. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark. 2006, p. 40. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/107760/E88840.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Ejov, M.; Sergiev, V.; Baranova, A.; Kurdova-Mintcheva, R; Emiroglu, N.; et al. Malaria in the WHO European Region: on the road to elimination 2000-2015: summary; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018; p. 40. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/342148/9789289053112-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Lysenko, A. J.; Kondrashin, A.V. Malariology. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999. Available online: https://fundamental-research.ru/ru/article/view?id=5473 (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Morenets, T.M.; Isaeva, E.B.; Gorodin, V.N.; Avdeeva, M.G.; Grechanaya, T.V. Clinical and epidemiologic aspects of malaria in Krasnodar Krai. Epidemiology and Infectious Diseases 2016, 21, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimov, I.Z.; Los’-Yatsenko, N.G.; Midikari, A.S.; Gorovenko, M.V.; Arshinov, P.S. Clinical and epidemiological features of imported malaria in the Republic of Crimea for a twenty-year period (1994-2014). Kazan medical journal 2014, 95, 916–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranova, A.M.; Sergiev, V.P.; Guzeeva, T.M.; Tokmalaev, A.K. Clinical suspicion to imported malaria: transfusion cases and deaths in Russia. Infectious Diseases: News, Opinions, Training 2018, 7, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornostaeva, R.M. A checklist of the mosquitoes (fam. Culicidae) in the European part of Russia. Parazitologiia 2000, 34, 428–434. [Google Scholar]

- Gutsevich, A.V.; Dubitskiy, A.M. New species of mosquitoes in the fauna of the USSR. Parazitologicheskiy sbornic 1981, 30, 97–165. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmiller, J.B.; Frizzi, G.; Baker, R. Wright, J.W., Ed.; Evolution and speciation within the Maculipennis complex of the genus Anopheles. In Genetics of Insect Vectors of Disease; Elsevier Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1967; pp. 151–210. [Google Scholar]

- Coluzzi, M. Sibling species in Anopheles and their importance in malariology. Miscellaneous Publ. Entomol. Soc. Amer. 1970, 7, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, K.L.; Stone, A. A catalog of the mosquitoes of the world (Diptera, Culicidae). 2nd edition. Thomas Say Found. Entomol. Soc. Amer. 1977. [Google Scholar]

- White, G.B. The place of morphological studies in the investigation of Anopheles species complexes. Mosquito Systematics 1977, 9, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- White, G.B. Systematic reappraisal of the Anopheles maculipennis complex. Mosquito Systematics 1978, 10, 13–44. [Google Scholar]

- Stegniy, V.N. Population Genetics and Evolution of Malaria Mosquitoes; Tomsk State University Publisher: Tomsk, Russia, 1991; pp. 1–137. ISBN 5-7511-0073-5. [Google Scholar]

- Frizzi, G. Salivary gland chromosomes of Anopheles. Nature (London) 1947, 160, 226–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frizzi, G. Nuovi contributi e prospetti di ricerca nel gruppo Anopheles maculipennis in base allo studio del dimorfismo cromosomico. Symposia Genetica 1952, 3, 231–265. [Google Scholar]

- Frizzi, G. Etude cytogénétique d'Anopheles maculipennis en Italie. Bull World Health Organ. 1953, 9, 335–344. [Google Scholar]

- Kiknadze, I.I. Chromosomes of Diptera. Evolutionary and practical significance. Genetika 1967, 7, 145–165. [Google Scholar]

- Kabanova, V.M.; Kartashova, N.N.; Stegnii, V.N. Karyological study of natural populations of malarial mosquitoes in the Middle Ob river. I. Characteristics of the karyotype of Anopheles maculipennis messeae. Tsitologiia 1972, 14, 630–636. [Google Scholar]

- Stegnii, V.N.; Kabanova, V.M. Cytoecological study of natural populations of malaria mosquitoes on the USSR territory. 1. Isolation of a new species of Anopheles in Maculipennis complex by the cytodiagnostic method. Med Parazitol (Mosk) 1976, 45, 192–198. [Google Scholar]

- Stegniy, V.N. Detection of chromosomal races in the malaria mosquito Anopheles sacharovi. Tsitologiia 1976, 18, 1039–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Stegniy, V.N. Reproductive interrelations of malaria mosquitos of the complex Anopheles maculipennis (Diptera, Culicidae). Zool Zh. 1980, 59, 1469–1475. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, R.H.; French, W.L.; Kitzmiller, J.B. Induced copulation in Anopheles mosquitoes. Mosq News 1962, 22, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, F.H.; Paskewitz, S.M. A review of the use of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) to differentiate among cryptic Anopheles species. Insect Mol. Biol. 1996, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbach, R.E. The classification of genus Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae): a working hypothesis of phylogenetic relationships. Bull Entomol Res. 2004, 94, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbach, R.E. Review of the internal classification of the genus Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae): the foundation for comparative systematics and phylogenetic research. Bulletin of Entomological Research 1994, 84, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedoroff, N.V. On spacers. Cell 1979, 16, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaghat, M.M.; Linton, Y.-M.; Oshaghu, M.A.; Vatandoost, H.; Harbach, R.E. The Anopheles maculipennis complex in Iran: Molecular characterization and recognition of a new species. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2003, 93, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaghat, M.M.; Howard, T.; Harbach, R.E. Morphological study and description of Anopheles (Anopheles) persiensis, a member of the Maculipennis Group (Diptera: Culicidae: Anophelinae) in Iran. Journal of Entomological Society of Iran 2009, 28, 35–25. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolescu, G.; Linton, Y.-M.; Vladimirescu, A.; Howard, T.M.; Harbach, R. E. Mosquitoes of the Anopheles maculipennis group (Diptera: Culicidae) in Romania, with the discovery and formal recognition of a new species based on molecular and morphological evidence. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2004, 94, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeev, M.I.; Zvantsov, A.B.; Goriacheva, I.I.; Shaĭkevich, E.V.; Ezhov, M.N. Description of the new species Anopheles artemievi sp.n. (Diptera, Culicidae). Med Parazitol (Mosk) 2005, 2, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, Y.-M.; Smith, L.; Harbach R., E. Observations on the taxonomic status of Anopheles subalpinus Hackett & Lewis and An. melanoon Hackett. Eur. Mosq. Bull. 2002, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, F.H.; Paskewitz, S.M. A review of the use of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) to differentiate among cryptic Anopheles species. Insect Mol. Biol. 1996, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinucci, M.; Romi, R.; Mancini, P.; Di Luca, M.; Severini, C. Phylogenetic relationships of seven palearctic members of the maculipennis complex inferred from ITS2 sequence analysis. Insect Mol Biol. 1999, 8, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proft, J.; Maier, W.A.; Kampen, H. Identification of six sibling species of the Anopheles maculipennis complex (Diptera: Culicidae) by a polymerase chain reaction assay. Parasitol. Res. 1999, 85, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harbach, R.E. The classification of genus Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae): a working hypothesis of phylogenetic relationships. Bull Entomol Res. 2004, 94, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbach, R. E. Manguin, S., Ed.; The phylogeny and classification of Anopheles. In Anopheles mosquitoes - New insights into malaria vectors; Chapter 1; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013; pp. 3–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, J.M.; Yurchenko, A.A.; Karagodin, D.A.; Masri, R.A.; Smith, R.C.; Gordeev, M.I.; Sharakhova, M.V. The new Internal Transcribed Spacer 2 diagnostic tool clarifies the taxonomic position and geographic distribution of the North American malaria vector Anopheles punctipennis. Malar J. 2021, 20, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumenko, A.N.; Karagodin, D.A.; Yurchenko, A.A.; Moskaev, A.V.; Martin, O.I.; Baricheva, E.M.; Sharakhov, I.V.; Gordeev, M.I.; Sharakhova, M.V. Chromosome and Genome Divergence between the Cryptic Eurasian Malaria Vector-Species Anopheles messeae and Anopheles daciae. Genes 2020, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko, A.A.; Naumenko, A.N.; Artemov, G.N.; Karagodin, D.A.; Hodge, Ja.M.; Velichevskaya, A.I.; Kokhanenko, A.A.; Bondarenko, S.M.; Abai, M.R.; Kamali, M.; Gordeev, M.I.; Moskaev, A.V.; Caputo, B.; Aghayan, S.A.; Baricheva, E.M.; Stegniy, V.N.; Sharakhova, M.V.; Sharakhov, I.V. Phylogenomics revealed migration routes and adaptive radiation timing of Holarctic malaria mosquito species of the Maculipennis Group. BMC Biol. 2023, 21, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalin, A.V.; Gornostaeva, R.M. On the taxonomic composition of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) of the world and Russian fauna (critical review). Parazitologiia 2008, 42, 360–381. [Google Scholar]

- Gornostaeva, R.M. Analysis of modern data on the fauna and ranges of malaria mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae: Anopheles) on the territory of Russia. Parazitologiia 2003, 37, 298–305. [Google Scholar]

- Gornostaeva, R.M.; Danilov, A.V. On ranges of the malaria mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae: Anopheles) of the Maculipennis complex on the territory of Russia. Parazitologiia 2002, 36, 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict, M.; Dotson, E. Methods in Anopheles research. 2015. Atlanta: Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center.

- Gutsevich, A.V.; Monchadskii, A.S.; Shtakelberg, A.A. Fauna of the USSR. Diptera. Mosquitoes; family Culicidae. Zoological Institute, USSR Academy of Science: Leningrad, Russia, 1971; p. 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, M.V.; Sycheva, K.A. Blood-sucking mosquitoes (Diptera:Culicidae) of the Krasnodar Territory and the Crimean Peninsula: an identifier Akimkin, V.G., Eds.; FBIS Central Research Institute of Epidemiology: Moscow, Russia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Moskaev, A.V.; Gordeev, M.I.; Kuzmin, O.V. Chromosomal composition of populations of malaria mosquito Anopheles messeae in the centre and on the periphery of the species range. Bulletin of Moscow State Regional University. Natural Sciences 2015, 1, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Stegniy, V. N.; Kabanova, V. M. Chromosomal analysis of malaria mosquitoes Anopheles atroparvus and A. maculipennis (Diptera, Culicidae). Zool. zh. 1978, 57, 613–619. [Google Scholar]

- Artemov, G.N.; Fedorova, V.S.; Karagodin, D.A.; Brusentsov, I.I.; Baricheva, E.M.; Sharakhov, I.V.; Gordeev, M.I.; Sharakhova, M.V. New cytogenetic photomap and molecular diagnostics for the cryptic species of the malaria mosquitoes Anopheles messeae and Anopheles daciae from Eurasia. Insects 2021, 12, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corder, G.W.; Foreman, D.I. Nonparametric statistics: a step-by-step approach, 2nd ed; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; p. 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Purification of nucleic acids by extraction with phenol:chloroform. CSH protocols 2006, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusentsov, I.I.; Gordeev, M.I.; Yurchenko, A.A.; Karagodin, D.A.; Moskaev, A.V.; Hodge, J.M.; Burlak, V.A.; Artemov, G.N.; Sibataev, A.K.; Becker, N.; Sharakhov, I.V.; Baricheva, E.M.; Sharakhova, M.V. Patterns of genetic differentiation imply distinct phylogeographic history of the mosquito species Anopheles messeae and Anopheles daciae in Eurasia. Mol Ecol. 2023, 32, 5609–5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozen, S.; Skaletsky, H.J. Misener, S., Krawetz, S., Eds.; Primer 3 on the WWW for general users and biologist programmers. In In Methods in molecular biology: Bioinformatics methods and protocols; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2000; Volume 132, pp. 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untergasser, A.; Cutcutache, I.; Koressaar, T.; Ye, J.; Faircloth, B.C.; Remm, M.; Rozen, S.G. Primer3 — new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, K.S. A Comparative Study of Mosquito Karyotypes. Ann. Ent. Soc. Amer. 1963, 56, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeev, M.I.; Temnikov, A.A.; Panov, V.I.; Klimov, K.S.; Lee, E.Yu.; Moskaev, A.V. Chromosomal variability in populations of malaria mosquitoes in different landscape zones of Eastern Europe and the Southern Urals. Bulletin of the Moscow State Regional University (Geographical Environment and Living Systems 2022, 4, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, Y.M.; Vaulin, O.V. Expansion of Anopheles maculipennis s.s. (Diptera: Culicidae) to northeastern Europe and northwestern Asia: causes and consequences. Parasit Vectors. [CrossRef]

- Moskaev, A.V.; Bega, A.G.; Panov, V.I.; Perevozkin, V.P.; Gordeev, M.I. (2024). Chromosomal polymorphism of malaria mosquitoes of Karelia and expansion of northern boundaries of species ranges. Russian Journal of Genetics 2024, 60, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeev, M.I.; Moskaev, A.V.; Bezzhonova, O.V. Chromosomal polymorphism in the populations of malaria vector mosquito Anopheles messeae at the south of Russian plain. Russian Journal of Genetics 2012, 48, 962–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beklemishev, V.N. Ecology of the malaria mosquito; Medgiz: Moscow, Russia, 1944; pp. 1–299. [Google Scholar]

- Jetten, T.H.; Takken, W. Anophelism without malaria in Europe: a review of the ecology and distribution of the genus Anopheles in Europe; Agric Univ Pap.: Wageningen, Netherlands, 1994; Volume 94, pp. 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bertola, M.; Mazzucato, M.; Pombi, M.; Montarsi, F. Updated occurrence and bionomics of potential malaria vectors in Europe: a systematic review (2000–2021). Parasit Vectors 2022, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanchilina, A.G.; Ryan, W.B.F.; McManus, J.F.; Dimitrov, P.; Dimitrov, D.; Slavova, K.; Filipova-Marinova, M. Compilation of geophysical, geochronological, and geochemical evidence indicates a rapid Mediterranean-derived submergence of the Black Sea's shelf and subsequent substantial salinification in the early Holocene. Marine Geology 2017, 383, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseev, E.V.; Razumeiko, V.N. Blood-sucking mosquitoes (Diptera, Culicidae) of anthropogenic landscapes of flat Crimea. Ecosystems, their optimisation and protection 2005, 16, 120–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hubenov, Z. Species composition and distribution of the dipterans (Insecta: Diptera) in Bulgaria. Advanced Books. National Museum of Natural History: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2021; Sep 9. [CrossRef]

- Șuleșco, T.; Sauer, F.G.; Lühken, R. Update on the distribution of Anopheles maculipennis s. l. members in the Republic of Moldova with the first record of An. daciae. 2024; Aug 17. [CrossRef]

- Bezzhonova, O.V.; Babuadze, G.A.; Gordeev, M.I.; Goriacheva, I.I.; Zvantsov, A.B.; Ezhov, M.N.; Imnadze, P.; Iosava, M.; Kurtsikashvili, G. Malaria mosquitoes of the Anopheles maculipennis (Diptera, Culicidae) complex in Georgia. Med Parazitol (Mosk) 2008, 3, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Akiner, M.M.; Cağlar, S.S. Identification of Anopheles maculipennis group species using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the regions of Birecik, Beyşehir and Cankiri. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2010, 34, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Simsek, F.M.; Ulger, C.; Akiner, M.M.; Tuncay, S.S.; Kiremit, F.; Bardakci, F. Molecular identification and distribution of Anopheles maculipennis complex in the Mediterranean region of Turkey. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 2011, 39, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharakhova, M.V.; Stegnii, V.N.; Braginets, O.P. Interspecies differences in the ovarian trophocyte precentromere heterochromatin structure and evolution of the malaria mosquito complex Anopheles maculipennis. Genetika 1997, 33, 1640–1648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stegnii, V.N. , Structure reorganization of the interphase nuclei during ontogenesis and phylogenesis of malaria mosquitoes. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1979, 249, 1231–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Stegnii, V.N. Systemic reorganization of the architectonics of polytene chromosomes in the onto- and phylogenesis of malaria mosquitoes. Genetika 1987, 23, 821–827. [Google Scholar]

- Stegnii, V.N.; Sharakhova, M.V. Systemic reorganization of the architechtonics of polytene chromosomes in onto- and phylogenesis of malaria mosquitoes. Structural features regional of chromosomal adhesion to the nuclear membrane. Genetika 1991, 27, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kadamov, D.S.; Zvantseva, A.B.; Karimov, S.S.; Gordeev, M.I.; Goriacheva, I.I.; Ezhov, M.N.; Tadzhiboev, A. Malaria mosquitoes (Diptera, Culicidae, Anopheles) of North Tajikistan, their ecology, and role in the transmission of malaria pathogens. Med Parazitol (Mosk) 2012, 3, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Perevozkin, V.P. Chromosomal polymorphism of malarial mosquitoes (Diptera, Culicidae) of Primorsky Krai. Tomsk State Pedagogical University Bulletin 2009, 11, 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Khrabrova, N.V.; Andreeva, Y.V.; Sibataev, A.K.; Alekseeva, S.S.; Esenbekova, P.A. Mosquitoes of Anopheles hyrcanus (Diptera, Culicidae) group: species diagnostic and phylogenetic relationships. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015, 93, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarkova-Lyakh, I.V. Natural complexes of the coastal zone of the Southern coast of Crimea. Scientific Notes of the V. I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University. Geography. Geology 2015, 1, 42–58. [Google Scholar]

- Razumeiko, V.N.; Ivashov, A.V.; Oberemok, V.V. Seasonal activity and density dynamics of blood-sucking mosquitoes (Diptera, Culicidae) in water bodies of the southern coast of Crimea. Scientific Notes of the V. I. Vernadsky Tauride National University 2010, 23, 114–128. [Google Scholar]

- Gordeev, M.I.; Zvantsov, A.B.; Goriacheva, I.I.; Shaĭkevich, E.V.; Ezhov, M.N.; Usenbaev, N.T.; Shapieva, Zh.Zh.; Zhakhongirov, Sh.M. Anopheles mosquitoes (Diptera, Culicidae) of the Tien Shan: morphological, cytogenetic, and molecular genetic analysis. Med Parazitol (Mosk) 2008, 3, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Service, M.W. 1968. Observations on feeding and oviposition in some British mosquitoes. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 1968, 11, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffner, F.; Thiéry, I.; Kaufmann, C.; Zettor, A.; Lengeler, C.; Mathis, A.; Bourgouin, C. Anopheles plumbeus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Europe: a mere nuisance mosquito or potential malaria vector? Malar J. 2012, 11, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heym, E.C.; Kampen, H.; Fahle, M.; Hohenbrink, T.L.; Schäfer, M.; Scheuch, D.E.; Walther, D. Anopheles plumbeus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Germany: updated geographic distribution and public health impact of a nuisance and vector mosquito. Trop Med Int Health 2017, 22, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, N.; Petric, D.; Zgomba, M.; Boase, C.; Madon, M.; Dahl, C.; Kaiser, A. Mosquitoes and Their Control; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno-Marí, R.; Jiménez-Peydró, R. Anopheles plumbeus Stephens, 1828: a neglected malaria vector in Europe. Malaria Reports 2011, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekoninck, W.; Hendrickx, F.; Vasn Bortel, W.; Versteirt, V.; Coosemans, M.; Damiens, D.; Hance, T.; De Clercq, E.M.; Hendrickx, G.; Schaffner, F.; Grootaert, P. Human-induced expanded distribution of Anopheles plumbeus, experimental vector of West Nile virus and a potential vector of human malaria in Belgium. J Med Entomol. 2011, 48, 924–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bega, A.G.; Moskaev, A.V.; Gordeev, M.I. Ecology and distribution of the invasive mosquito species Aedes albopictus (Skuse, 1895) in the south of the European Part of Russia. Russian Journal of Biological Invasions 2021, 12, 148–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant, P.; Eling, W.; van Gemert, G.J.; Leake, C.J.; Curtis, C.F. Could british mosquitoes transmit falciparum malaria? Parasitol Today 1998, 14, 344–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno-Marí, R.; Jiménez-Peydró, R. Study of the malariogenic potential of Eastern Spain. Trop Biomed. 2012, 29, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, A.; Rech, A.; Su, X.Z.; Tannich, E. Two cases of autochthonous Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Germany with evidence for local transmission by indigenous Anopheles plumbeus. Trop Med Int Health 2001, 6, 983–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlock, J.M.; Snow, K.R.; Leach, S. Potential transmission of West Nile virus in the British Isles: an ecological review of candidate mosquito bridge vectors. Med Vet Entomol. 2005, 19, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlock, J.M.; Snow, K.R.; Leach, S. Possible ecology and epidemiology of medically important mosquito-borne arboviruses in Great Britain. Epidemiol Infect. 2007, 135, 466–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbina V., P. Materials on the fauna of blood-sucking mosquitoes (Diptera, Culicidae) of the Lower Don and North Caucasus. Parasitol. sb. of ZIN AS USSR 1974, 26, 205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Enikolopov, S.K. Biology of Anopheles algeriensis Theo. Med Parazitol (Mosk) 1944, 13, 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- Enikolopov, S.K. On the ecology of Anopheles algeriensis Theo. 1903. Med Parazitol (Mosk) 1937, 6, 354–359. [Google Scholar]

- Savitskiĭ, B.P. Blood-sucking mosquitoes (Culicidae) attacking man in the region of the Eastern Manych (Kalmyk ASSR). Parazitologiia 1982, 16, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tippelt, L.; Walther, D.; Scheuch, D.E.; Schäfer, M.; Kampen, H. Further reports of Anopheles algeriensis Theobald, 1903 (Diptera: Culicidae) in Germany, with evidence of local mass development. Parasitol. Res. 2018, 117, 2689–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perevozkin, V.P.; Bondarchuk, S.S.; Gordeev, M.I. The population-and-species-specific structure of malaria (Diptera, Culicidae) mosquitoes in the Caspian Lowland and Kuma-Manych Hollow. Med Parazitol (Mosk). 2012, 1, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, W.J.M.; Kovats, R.S.; Nijhof, S.; deVries, P.; Livermore, M.J.T.; Mc Michael, A.J.; Bradley, D.; Cox, J. Climate change and future populations at risk of malaria. Global Environ Change 1999, 9, S89–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasjukevich, V.V. Malaria in Russia and its immediate geographical environment: analysis of the situation in connection with the expected climate change. Problems of ecological monitoring and modelling of ecosystems 2002, 18, 142–157. [Google Scholar]

- Yasjukevich, V.V.; Titkina, S.N.; Popov, I.O.; Davidovich, E.A.; Yasjukevich, N.V. Climate-dependent diseases and arthropod vectors: possible impact of climate change observed in Russia. Problems of ecological monitoring and modelling of ecosystems 2013, 25, 314–359. [Google Scholar]

- NCBI. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

| No. | Location / breeding place | Latitude | Longitude | Date of sampling | Number (%) of mosquitoes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | AT | CL | HY | MA | DA | PL | ML | |||||

| Crimean Peninsula | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Pirogovka village, Nakhimov district of Sevastopol /water storage | 44.685296 | 33.739026 | 11.09.2016 | 18 | - | - | - | 18 (100) | - | - | - |

| 2 | Bakhchisaray town / pond | 44.763889 | 33.853056 | 10.09.2016 | 12 | 3 (25,0) | - | - | 9 (75,0) | - | - | - |

| 3 | Bakhchisaray town / dried-up creek | 44.763889 | 33.853611 | 10.09.2016 | 10 | - | - | - | 10 (100) | - | - | - |

| 4 | Simferopol city, botanical garden / pond | 44.939167 | 34.133056 | 10.09.2016 | 15 | - | - | - | 15 (100) | - | - | - |

| 5*1 | Mazanka village, Simferopol district / pond | 45.014861 | 34.235861 | 12.07.2016 | 57 | - | - | - | 57 (100) | - | - | - |

| 6 | Konstantinovka village, Simferopol district / lake | 44.856389 | 34.123333 | 20.08.2016 | 3 | - | - | - | 3 (100) | - | - | - |

| 7 | Mramornoye village, Simferopol district / lake | 44.813889 | 34.237222 | 20.06.2016 | 9 | - | - | - | 7 (77,8) | - | 2 (22,2) | - |

| 8 | Mezhgorye village, Belogorsky district / river | 44.970556 | 34.416111 | 20.06.2016 | 9 | - | 5 (55,6) | - | 4 (44,4) | - | - | - |

| 9 | Krasnosyolovka village, Belogorsky district / river spill | 44.917778 | 34.633333 | 20.06.2016 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | 2 (100) | - |

| 10A | Tylovoye village, Balaklava district of Sevastopol / pond | 44.441389 | 33.728056 | 13.09.2016 | 128 | 2 (1,6) | - | - | 60 (46,9) | 66 (51,5) | - | - |

| 10B*2 | 44.443570 | 33.739879 | 12.08.2017 | 21 | - | - | - | 12 (57,1) | 9 (42,9) | - | - | |

| 10C | 84 | 1 (1,2) | - | - | 83 (98,8) | - | - | - | ||||

| 10D*3 | 44.441740 | 33.727469 | 08.08.2019 | 53 | - | - | - | 23 (43,4) | 30 (56,6) | - | - | |

| 10E | 95 | - | - | - | 55 (57,9) | 40 (42,1) | - | - | ||||

| 11 | Rodnikovoye village, Balaklava district of Sevastopol / puddle | 44.453611 | 33.862222 | 20.07.2016 | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | 3 (100) | - |

| 12 | Rodnikovoye village, Balaklava district of Sevastopol / tree hollow | 44.457222 | 33.872778 | 20.07.2016 | 7 | - | - | - | - | - | 7 (100) | - |

| 13 | Simeiz Settlement, Yalta district / mountain puddle | 44.403611 | 33.991667 | 20.06.2016 | 5 | - | - | - | - | - | 5 (100) | - |

| 14 | Yalta district / forest puddle | 44.516389 | 34.143889 | 20.07.2016 | 37 | - | - | - | 37 (100) | - | - | - |

| 15 | Gaspra settlement, Yalta district / water in rock cracks | 44.433611 | 34.130000 | 20.06.2016 | 3 | - | - | - | - | - | 3 (100) | - |

| 16 | Gaspra settlement, Yalta district / tree hollow | 44.445278 | 34.118889 | 20.06.2016 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | 2 (100) | - |

| 17 | Voskhod settlement, Yalta district / lake | 44.517417 | 34.219796 | 20.08.2016 | 8 | - | 8 (100) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 18 | Nikitsky Botanical Gardens, Yalta district / pond | 44.508831 | 34.233093 | 13.09.2016 | 7 | - | - | - | 1 (14,3) | - | 6 (85,7) | - |

| 19 | Krasnokamenka village, Yalta district / forest puddle | 44.577500 | 34.255556 | 20.06.2016 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | 2 (100) | - |

| 20 | Zaprudnoye village, Alushta district / lake | 44.599444 | 34.305000 | 20.08.2016 | 14 | - | 14 (100) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 21 | Nizhnyaya Kutuzovka village, Alushta district / pond | 44.709842 | 34.377544 | 14.09.2016 | 31 | - | - | - | 31 (100) | - | - | - |

| 22 | Alushta district / pond | 44.814167 | 34.657778 | 14.09.2016 | 12 | - | - | - | 12 (100) | - | - | - |

| 23 | Gromovka village, Sudak district / pond | 44.857778 | 34.791389 | 20.06.2016 | 3 | - | 3 (100) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 24 | Voron village, Sudak district / spring | 44.892222 | 34.820278 | 20.08.2016 | 3 | - | 3 (100) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 25 | Veseloye village, Sudak district / water reserve | 44.849722 | 34.883611 | 15.09.2016 | 9 | - | - | - | 9 (100) | - | - | - |

| 26 | Sudak district / pond | 44.868611 | 34.900556 | 15.09.2016 | 3 | - | - | - | 3 (100) | - | - | - |

| 27 | Veseloye village, Sudak district / lake | 44.851944 | 34.883333 | 20.08.2016 | 2 | - | 2 (100) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 28 | Dachnoye village, Sudak district / river spill | 44.888889 | 34.990278 | 20.08.2016 | 1 | - | - | 1 (100) | - | - | - | - |

| 29 | Dachnoye village, Sudak district / lake | 44.897362 | 35.040173 | 20.08.2016 | 4 | - | - | 4 (100) | - | - | - | - |

| 30 | Mindalnoye village, Sudak district / lake | 44.831756 | 35.082243 | 20.07.2016 | 3 | - | - | 3 (100) | - | - | - | - |

| 31 | Grushevka village, Sudak district / lake | 45.010570 | 34.971796 | 15.09.2016 | 48 | - | - | - | 48 (100) | - | - | - |

| 32 | Feodosia city / pond | 45.063792 | 35.341071 | 16.09.2016 | 9 | 7 (77,8) | - | - | 2 (22,2) | - | - | - |

| Black Sea coast of the Caucasus | ||||||||||||

| 33 | Krasnogvardeyskoye village, Stavropol Krai / dried up river | 45.850476 | 41.482381 | 12.08.2015 | 27 | 27 (100) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 34 | Stavropol city / pond | 45.013332 | 41.974723 | 12.08.2015 | 30 | - | - | - | 26 (86,7) | 4 (13,3) | - | - |

| 35 | Malevanyi settlement, Krasnodar Krai / river | 45.531517 | 39.461591 | 21.08.2015 | 50 | - | - | - | 1 (2,0) | 49 (98,0) | - | - |

| 36 | Razdolnaya village, Korenovsky district, Krasnodar Krai / lake | 45.383469 | 39.537257 | 01.08.2024 | 100 | - | - | 18 (18,0) | 52 (52,0) | 30 (30,0) | - | - |

| 37 | Shengzhiy settlement, Republic of Adygeya / channel | 44.883810 | 39.075139 | 05.08.2009 | 54 | - | - | 1 (1,9) | 2 (3,7) | 51 (94,4) | - | - |

| 38 | Novonikolayevskaya village, Krasnodar Krai / pond | 45.581165 | 38.369233 | 04.08.2019 | 120 | - | - | - | - | 120 (100) | - | - |

| 39 | Tamanskoye Settlement, Temryuksky district, Krasnodar Krai / lake | 45.144803 | 36.700849 | 07.07.2016 | 35 | 35 (100) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 40*4 | Abinsk town, Krasnodar Krai / pond | 44.862380 | 38.183556 | 14.08.2018 | 108 | - | - | - | - | 108 (100) | - | - |

| 41 | Gaiduk village, Novorossiysk district, Krasnodar Krai / pond | 44.781486 | 37.679653 | 03.08.2018 | 100 | - | - | - | - | 100 (100) | - | - |

| 42 | Novorossiysk district, Krasnodar Krai / water storage | 44.780000 | 37.815833 | 09.07.2016 | 108 | - | - | - | 1 (0,9) | 107 (99,1) | - | - |

| 43 | Pshada village, Gelendzhik district, Krasnodar Krai / river | 44.452257 | 38.346501 | 19.08.2015 | 106 | - | - | - | 70 (66,0) | 36 (34,0) | - | - |

| 44 | Community Zarya, Tuapse district, Krasnodar Krai /car tire | 44.082778 | 39.131667 | 31.07.2021 | 36 | - | - | - | - | - | 36 (100) | - |

| 45 | Novomikhailovsky settlement, Tuapse district, Krasnodar Krai / drainage ditch | 44.247752 | 38.844524 | 18.08.2015 | 100 | - | 100 (100) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 46 | Agui-Shapsug village, Tuapse district, Krasnodar Krai / river | 44.174722 | 39.066944 | 11.07.2016 | 35 | - | - | - | 35 (100) | - | - | - |

| 47 | Zubova Shchel village, Sochi district, Krasnodar Krai / river | 43.837451 | 39.441109 | 13.07.2016 | 34 | - | - | - | 34 (100) | - | - | - |

| 48 | Sochi city, Krasnodar Krai / tree hollow | 43.675833 | 39.608889 | 30.07.2021 | 60 | - | - | - | - | - | 60 (100) | - |

| 49 | Adler town, Krasnodar Krai / swamp | 43.432222 | 39.947222 | 17.07.2016 | 32 | - | - | - | 32 (100) | - | - | - |

| 50A | Verkhneveseloye village, Sochi district, Krasnodar Krai / drainage ditch | 43.426067 | 39.973288 | 04.08.2023 | 14 | - | 14 (100) | - | - | - | - | - |

| 50B*5 | 6 | - | 6 (100) | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 50C | 43.426306 | 39.973515 | 04.08.2024 | 3 | - | 3 (100) | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 51*6 | Sochi city, Krasnodar Krai / stream | 43.410321 | 39.983947 | 07.08.2024 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 (100) |

| 52 | Sirius settlement, Krasnodar Krai / fire pond | 43.412778 | 39.937778 | 16.07.2016 | 156 | - | - | - | 156 (100) | - | - | - |

| 53 | Vesyoloye microdistrict, Sochi city, Krasnodar Krai / car tire | 43.409722 | 40.008330 | 11.08.2018 | 32 | - | - | - | - | - | 32 (100) | - |

| 54 | Krasnaya Polyana Resort, Sochi district, Krasnodar Krai / hollow tree | 43.711944 | 40.209167 | 25.07.2021 | 94 | - | - | - | - | - | 94 (100) | - |

| 55 | Rosa Khutor resort, Sochi district, Krasnodar Krai /hollow tree | 43.638978 | 40.307983 | 29.07.2021 | 39 | - | - | - | - | - | 39 (100) | - |

| 56 | Ritsinsky National Park, Gudauta district, Abkhazia /car tire | 43.473889 | 40.538056 | 24.07.2021 | 16 | - | - | - | - | - | 16 (100) | - |

| No. | Location / breeding place | Latitude | Longitude | Date of sampling | Density of larvae (1-4 instars/sq. m) | Ecological characteristics of habitats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h (m) | pH | T (°C) | ppt | O₂ (mg/L) | ||||||

| Crimean Peninsula | ||||||||||

| 1 | Pirogovka village, Nakhimov district of Sevastopol /water storage | 44.685296 | 33.739026 | 11.09.2016 | 45 | 63 | 8,05 | 30,0 | 0,34 | 6,0 |

| 2 | Bakhchisaray town / pond | 44.763889 | 33.853056 | 10.09.2016 | 28 | 160 | 8,05 | 18,0 | 0,59 | 7,7 |

| 3 | Bakhchisaray town /dried-up creek | 44.763889 | 33.853611 | 10.09.2016 | 160 | 160 | 7,70 | 20,7 | 0,70 | 4,5 |

| 4 | Simferopol city, botanical garden / pond | 44.939167 | 34.133056 | 10.09.2016 | 76 | 255 | 6,48 | 22,6 | 0,16 | 4,5 |

| 5 | Mazanka village, Simferopol district / pond | 45.014861 | 34.235861 | 12.07.2016 | - | 298 | 8,15 | 24,5 | 0,26 | 7.0 |

| 6 | Konstantinovka village, Simferopol district / lake | 44.856389 | 34.123333 | 20.08.2016 | 3 | 421 | 7,84 | 24,8 | 2,56 | - |

| 7 | Mramornoye village, Simferopol district / lake | 44.813889 | 34.237222 | 20.06.2016 | 7 | 493 | 7,62 | 16,5 | 2,14 | - |

| 8 | Mezhgorye village,Belogorsky district / river | 44.970556 | 34.416111 | 20.06.2016 | 9 | 385 | 7,22 | 21,6 | 1,21 | - |

| 9 | Krasnosyolovka village, Belogorsky district / river spill | 44.917778 | 34.633333 | 20.06.2016 | 2 | 401 | 7,62 | 18,3 | 1,94 | - |

| 10 | Tylovoye village, Balaklava district of Sevastopol / pond | 44.441389 | 33.728056 | 13.09.2016 | 15 | 295 | 8,15 | 22,1 | 0,22 | 7,8 |

| 11 | Rodnikovoye village, Balaklava district of Sevastopol / puddle | 44.453611 | 33.862222 | 20.07.2016 | 3 | 657 | 7,32 | 32,3 | 0,14 | - |

| 12 | Rodnikovoye village, Balaklava district of Sevastopol /tree hollow | 44.457222 | 33.872778 | 20.07.2016 | 7 | 434 | 7,14 | 24,7 | 0,04 | - |

| 13 | Simeiz Settlement, Yalta District / mountain puddle | 44.403611 | 33.991667 | 20.06.2016 | 5 | 149 | 8,32 | 18,0 | 0,17 | - |

| 14 | Yalta district / forest puddle | 44.516389 | 34.143889 | 20.07.2016 | 7 | 212 | 7,24 | 19,7 | 0,15 | - |

| 15 | Gaspra settlement, Yalta District / water in rock cracks | 44.433611 | 34.130000 | 20.06.2016 | 3 | 24 | 7,52 | 24,8 | 0,31 | - |

| 16 | Gaspra settlement, Yalta district / tree hollow | 44.445278 | 34.118889 | 20.06.2016 | 2 | 338 | 7,16 | 25,1 | 0,03 | - |

| 17 | Voskhod settlement, Yalta district / lake | 44.517417 | 34.219796 | 20.08.2016 | 8 | 330 | 7,30 | 21,5 | 0,24 | - |

| 18 | Nikitsky Botanical Gardens, Yalta district / pond | 44.508831 | 34.233093 | 13.09.2016 | 15 | 110 | 7,37 | 20,2 | 0,31 | 7,5 |

| 19 | Krasnokamenka village, Yalta district / forest puddle | 44.577500 | 34.255556 | 20.06.2016 | 2 | 770 | 7,23 | 14,9 | 0,11 | - |

| 20 | Zaprudnoye village, Alushta district / lake | 44.599444 | 34.305000 | 20.08.2016 | 14 | 614 | 7,14 | 17,5 | 0,21 | - |

| 21 | Nizhnyaya Kutuzovka village, Alushta district / pond | 44.709842 | 34.377544 | 14.09.2016 | 78 | 153 | 7,29 | 25,2 | 0,20 | 10,2 |

| 22 | Alushta district / pond | 44.814167 | 34.657778 | 14.09.2016 | 70 | 70 | 7,05 | 22,4 | 0,98 | 4,4 |

| 23 | Gromovka village, Sudak district / pond | 44.857778 | 34.791389 | 20.06.2016 | 3 | 157 | 7,52 | 16,5 | 2,08 | - |

| 24 | Voron village, Sudak district / spring | 44.892222 | 34.820278 | 20.08.2016 | 3 | 229 | 7,72 | 16,7 | 0,74 | - |

| 25 | Veseloye village, Sudak district / water reserve | 44.849722 | 34.883611 | 15.09.2016 | - | 131 | 7,28 | 23,2 | 0,81 | 2,3 |

| 26 | Sudak district / pond | 44.868611 | 34.900556 | 15.09.2016 | - | 125 | 8,31 | 22,6 | 0,25 | - |

| 27 | Veseloye village, Sudak district / lake | 44.851944 | 34.883333 | 20.08.2016 | 2 | 101 | 7,42 | 23,7 | 0,24 | - |

| 28 | Dachnoye village, Sudak district / river spill | 44.888889 | 34.990278 | 20.08.2016 | - | 76 | 7,47 | 22,4 | 3,02 | - |

| 29 | Dachnoye village, Sudak district / lake | 44.897362 | 35.040173 | 20.08.2016 | 4 | 239 | 7,54 | 23,8 | 0,92 | - |

| 30 | Mindalnoye village, Sudak district / lake | 44.831756 | 35.082243 | 20.07.2016 | 3 | 33 | 8,24 | 26,3 | 1,18 | - |

| 31 | Grushevka village, Sudak district / lake | 45.010570 | 34.971796 | 15.09.2016 | 29 | 223 | 6,93 | 22,0 | 0,27 | 8,0 |

| 32 | Feodosia city / pond | 45.063792 | 35.341071 | 16.09.2016 | 26 | 20 | 7,14 | 24,3 | 1,46 | 16,5 |

| Black Sea coast of the Caucasus | ||||||||||

| 33 | Krasnogvardeyskoye village, Stavropol Krai / dried up river | 45.850476 | 41.482381 | 12.08.2015 | 1 | 60 | 9,10 | 28,0 | 5,99 | 11,3 |

| 34 | Stavropol city / pond | 45.013332 | 41.974723 | 12.08.2015 | - | 484 | 8,85 | 26,5 | 0,20 | 7,9 |

| 35 | Malevanyi settlement, Krasnodar Krai / river | 45.531517 | 39.461591 | 21.08.2015 | 1 | 40 | 8,00 | 24,0 | 1,58 | 6,9 |

| 36 | Razdolnaya village, Korenovsky district,Krasnodar Krai / lake | 45.383469 | 39.537257 | 01.08.2024 | 10 | 47 | 8,06 | 25,6 | 1,01 | 10,0 |

| 37 | Shengzhiy settlement, Republic of Adygeya / channel | 44.883810 | 39.075139 | 05.08.2009 | - | 44 | 7,00 | 33,3 | 0,81 | - |

| 38 | Novonikolayevskaya village, Krasnodar Krai / pond | 45.581165 | 38.369233 | 04.08.2019 | 29 | 2 | 8,50 | 25,5 | 0,19 | 8,0 |

| 39 | Tamanskoye Settlement, Temryuksky district, Krasnodar Region / lake | 45.144803 | 36.700849 | 07.07.2016 | 11 | 155 | 8,00 | 20,5 | - | 8,0 |

| 40 | Abinsk town, Krasnodar Krai / pond | 44.862380 | 38.183556 | 14.08.2018 | - | 29 | 7,60 | 30,0 | 0,27 | 5,0 |

| 41 | Gaiduk village, Novorossiysk district, Krasnodar Krai / pond | 44.781486 | 37.679653 | 03.08.2018 | 16 | 98 | 7,40 | 26,2 | 0,27 | 4,0 |

| 42 | Novorossiysk District, Krasnodar Krai / water storage | 44.780000 | 37.815833 | 09.07.2016 | 14 | 162 | 8,40 | 21,5 | - | 5,0 |

| 43 | Pshada village, Gelendzhik District, Krasnodar Krai / river | 44.452257 | 38.346501 | 19.08.2015 | 56 | 27 | 7,30 | 21,8 | 0,48 | 8,1 |

| 44 | Community Zarya, Tuapse district, Krasnodar Krai /car tire | 44.082778 | 39.131667 | 31.07.2021 | - | 172 | 5,50 | 26,5 | 1,45 | 2,5 |

| 45 | Novomikhailovsky settlement, Tuapse district, Krasnodar Krai / drainage ditch | 44.247752 | 38.844524 | 18.08.2015 | 32 | 5 | 7,54 | 23,4 | 0,45 | 2,5 |

| 46 | Agui-Shapsug village, Tuapse district, Krasnodar Krai / river | 44.174722 | 39.066944 | 11.07.2016 | 67 | 31 | 7,80 | 22,0 | - | 8,0 |

| 47 | Zubova Shchel village, Sochi district, Krasnodar Krai / river | 43.837451 | 39.441109 | 13.07.2016 | 72 | 175 | 7,80 | 24,0 | - | 8,0 |

| 48 | Sochi city, Krasnodar Krai / tree hollow | 43.675833 | 39.608889 | 30.07.2021 | - | 74 | 6,00 | 24,0 | 2,04 | 3,0 |

| 49 | Adler town, Krasnodar Krai / swamp | 43.432222 | 39.947222 | 17.07.2016 | 1,5 | 45 | 8,20 | - | - | 6 |

| 50 | Verkhneveseloye village, Sochi district, Krasnodar Krai / drainage ditch | 43.426306 | 39.973515 | 04.08.2024 | 3 | 31 | 9,26 | 27,8 | 0,54 | 7,6 |

| 51 | Sochi city, Krasnodar Krai / stream | 43.410321 | 39.983947 | 07.08.2024 | - | 14 | 7,60 | - | - | - |

| 52 | Sirius settlement, Krasnodar Krai / fire pond | 43.412778 | 39.937778 | 16.07.2016 | 18 | 15 | 8,40 | 27,0 | - | 4 |

| 53 | Vesyoloye microdistrict, Sochi city, Krasnodar Krai / car tire | 43.409722 | 40.008330 | 11.08.2018 | - | 13 | 7,40 | 27,3 | 0,25 | - |

| 54 | Krasnaya Polyana Resort, Sochi district, Krasnodar Krai / hollow tree | 43.711944 | 40.209167 | 25.07.2021 | - | 1693 | 5,50 | 22,6 | 2,30 | 3,5 |

| 55 | Rosa Khutor resort, Sochi district, Krasnodar Krai / hollow tree | 43.638978 | 40.307983 | 29.07.2021 | - | 1708 | 5,20 | 21,5 | 1,50 | 3,0 |

| 56 | Ritsinsky National Park, Gudauta district, Abkhazia /car tire | 43.473889 | 40.538056 | 24.07.2021 | - | 1041 | 6,00 | 21,3 | 2,78 | 2,5 |

| Inversion homo- and heterozygotes | Frequencies of chromosomal variants, f ± Sf, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crimean Peninsula | Black Sea coast of the Caucasus | |||

| Location 10 | Location 36 | Location 40 | Location 42 | |

| Males, n | 30 | 16 | 49 | 46 |

| XL0 | 73,3±8,1 | 56,2±12,4 | 61,2±7,0 | 37,0±7,1 |

| XL1 | 26,7±8,1 | 43,8±12,4 | 38,8±7,0 | 63,0±7,1 |

| Females, n | 36 | 14 | 59 | 61 |

| XL00 | 41,7±8,2 | 35,7±12,8 | 32,2±6,1 | 23,0±5,4 |

| XL01 | 50,0±8,3 | 42,9±13,2 | 45,8±6,5 | 36,0±6,1 |

| XL11 | 8,3±4,6 | 21,4±11,0 | 22,0±5,4 | 41,0±6,3 |

| Both sexes, n | 66 | 30 | 108 | 107 |

| 2R00 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99,1±0,9 |

| 2R05 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0,9±0,9 |

| 2L00 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 3R00 | 100 | 90,0±5,5 | 92,6±2,5 | 91,6±2,7 |

| 3R01 | 0 | 10,0±5,5 | 7,4±2,5 | 7,5±2,5 |

| 3R11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0,9±0,9 |

| 3L00 | 98,5±1,5 | 83,3±6,8 | 89,8±2,9 | 81,3±3,8 |

| 3L01 | 1,5±1,5 | 13,3±6,2 | 10,2±2,9 | 15,9±3,5 |

| 3L11 | 0 | 3,3±3,3 | 0 | 2,8±1,6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).