1. Introduction

The case study in this article and its research content is an approach to Fog Computing (Fog) and Intelligent Edge Computing (IEC) as applied to Smart Cities and Smart Buildings provided with suitable automation and intelligence for the management and control of smart IoT devices of different types. Over the last decade a novel architecture has emerged designed to be applied in data analytics and smart IoT devices. Fog and IEC are increasing their hold around the world for constrained applications by such factors as costly bandwidth, long latency and QoE sensitivity or even need high processing power and large storage for structured or unstructured data close to the place where data are generated or received by IoT devices.

Besides Smart Cities, services are provided in several areas for applications such as traffic control, public services, environmentally sustainable systems, water and electricity supply, buildings or neighborhoods integration to the roadway network, energy distribution network for electric vehicles (EVs). The application areas are Industry 4.0 or Fourth Industrial Revolution, smart factory, smart farming in order to boost the productivity of agribusiness by means of drones, smart machinery equipped with IoT devices, LoRa networks, video and security surveillance systems [

1].

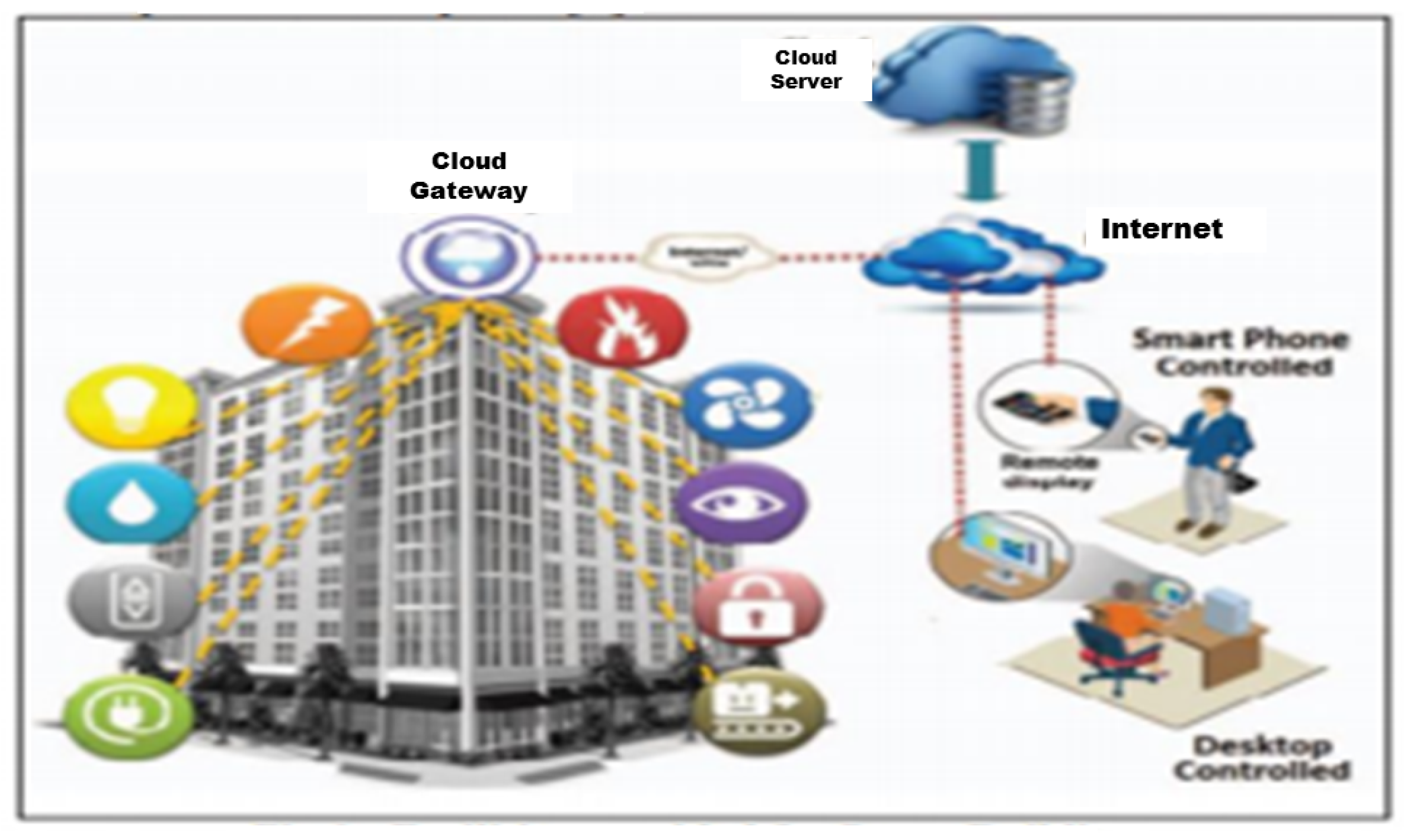

The core of this article is the site where the computational power is to be installed and supplied with reference to the Smart Buildings (SBs) in order to make it possible to carry on the operational study. This computing power may be concentrated within the Fog or the IEC or even yet in a hybrid solution as in the two cases cited in

multi-cloud, which could be extended to the traditional cloud. A parallel discussion which is entertained concerns the ideal number of cloud providers which should be contemplated. We refer to

Figure 1 [

2], which illustrates an SB operating under multiple solutions and implementations.

The proposed use case is a Smart Building (SB), or some federated or non-federated SBs, considering the main challenges to run secure data and voice services for taking actions on actuators, interpreting sensor readings in Wi-Fi networks at the edge, access and mobility of actors in SB complemented with Voice over IoT (VIoT) technology and even IoT using video-analytics.

Furthermore, the deployment of advanced services is considered, which may be demanded by a smartphone within the Smart Building or from the outside. And, also, federated entities in the Fog or the IEC may intervene such as a chatbot for communication to and from the SB virtual or real doorman, advanced audio services such as unified communication, videoconference or a conference call between actors, call parking, call forwarding. Also, exclusive use of complementary intra condominium Wi-Fi network can be made, as long as the cost can be afforded, over 4G/5G through authentication applications for multiple actors by means of a smartphone and integrated smart messaging.

A large number of studies about the integration of cloud computing, either Fog or IEC, with IoT bring forward methods and beneficial aspects targeting the evolution in the application and use of the technology. In addition, there is much innovation underway ranging from new network models and open communications such as SDN, or even NFV which is being adopted by telecommunications operators. Besides, better routing methods and security procedures down to the edge with IoT devices are envisaged. Beyond that, it is possible to adopt a microservices architecture for Fog and IEC with applications running in containers integrated with data analitycs for the acquisition, storage and feedback of critical data analyses.

Such data acquired or processed in large volume over a short period of time may be optimally handled by Machine Learning (ML) in real world applications [

3]. At the end, a comparative study is carried out between Fog and IEC taking into consideration the state of the art.

This article is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes the methodology used for this research.

Section 3 describes the main concepts, models and discloses a brief vision about relevant technologies while

Section 4 discusses the primary references for this research followed by a wide overview of the sources for the case study as well as its main current and future challenges and contributions.

Section 5 outlines the main challenges of integrating Fog or IEC into a

smart Building (SB) or a federation of SBs. It summarizes the key categories and services in a central, guiding table for recommended solutions, considering both IoT devices and Fog/IEC, with and without SDN adoption.

Section 6 details a paradigmatic use case of an SB within a smart city, leveraging best practices and state-of-the-art research. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the study

3. Concepts, Models and Technologies

This Section provides a concise overview of the core concepts, models, and technologies essential for comprehending this study and its future development.

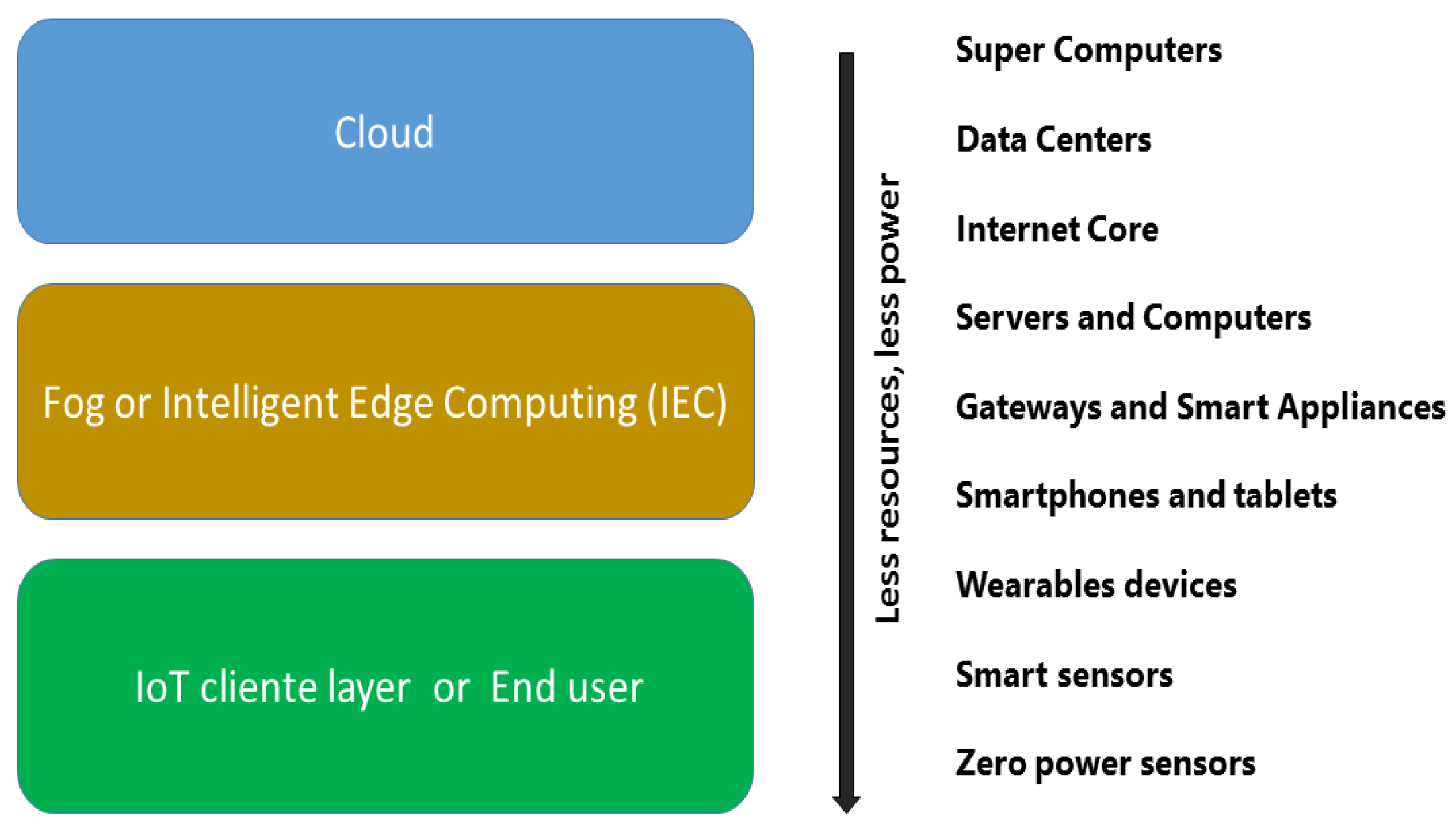

3.1. Fog Computing

Fog computing facilitates the management of data consistency and access controls in scenarios where two or more small, independent, distributed

cloud entities share resources including files, computational resources, commands, and authentication or access to local data storage within each Fog node on

Figure 2. The Fog architecture [

4] represents a fully distributed, multi-tier cloud computing system integrating millions of devices and a large-scale network of interconnected distributed cloud data centers. This architecture is particularly well-suited for applications requiring low latency, real-time responsiveness, such as those involving IoT devices.

3.2. Intelligent Edge Computing (IEC)

The IEC, or its origin in

Edge Computing, as shown in

Figure 2 and [

5], serves as a local source for data processing, storage, and computational needs within a broader cloud computing strategy. The most comprehensive definition of IEC is

Edge Computing with enhanced intelligence in data handling, applications, and communication representing a natural evolution of network and cloud computing architectures. So, to simplify notation, the term

IEC is adopted. Similar to Fog Computing, IEC is positioned closer to the edge in the layered model and is primarily designed for applications requiring real-time responses, low latency, and connectivity to IoT devices [

6].

Many times, Edge nodes [

7] are often implemented on high-end IoT devices, such as boards equipped with NVIDIA GPUs (high-performance) or from other manufacturers, as well as on desktop computers and laptops. These nodes do not necessarily rely on traditional servers, which are typically characterized by robust computational power and reasonable storage capacity but are cost-sensitive. The degree of maturity and security in these implementations has advanced significantly, enabling the adoption of more sophisticated models, depending on the specific use case.

Figure 2.

Cloud, Fog and Intelligent Edge Computing(IEC).

Figure 2.

Cloud, Fog and Intelligent Edge Computing(IEC).

Finally, given the extensive literature on cloud over the past fifteen years, the text simplifies the discussion by omitting a redefinition of Cloud Computing, focusing instead on other more pertinent topics.

3.3. Software Defined Network (SDN)

SDN, Software Defined Network, is by definition an emerging, dynamic, cost-effective, manageable, and highly adaptable architecture, in short an ideal solution for the dynamic and broadband nature of real-world applications. The SDN architecture separates the network control and packet forwarding functions, allowing network control to be directly programmable on switches and routers, and the infrastructure, in turn, to be made a new abstraction for network applications and services, according to the definition of the Open Network Foundation itself.

The advent of SDN initially brought

Openflow [

8,

9] a way for researchers to program the API and open network interface of switches from various worldwide manufacturers, creating a parallel research network that was later used for business or production environments, see the articles: [

10,

11] current research presents to a moderate adoption in the IoT space, both integrated with IEC and Fog.

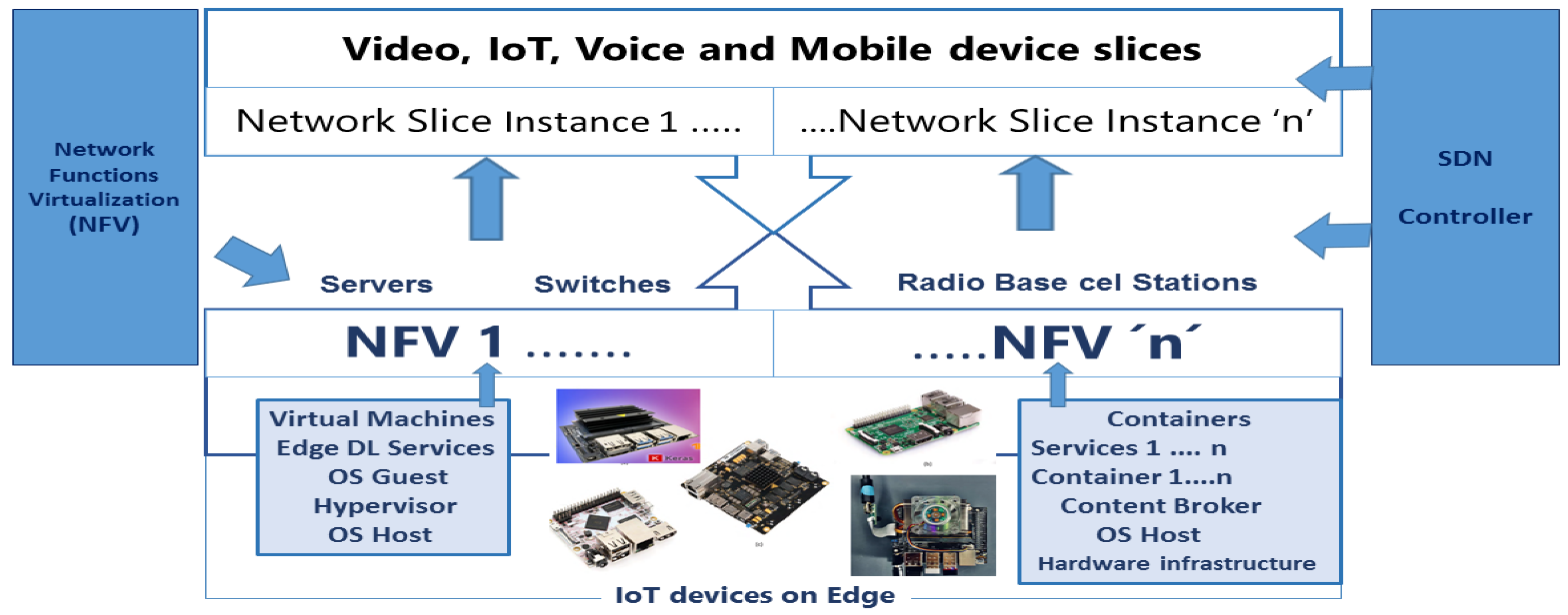

3.4. Network Functions Virtualization

Network Functions Virtualization (NFV) originated from discussions among telecommunications service providers about improving network operations in response to the significant growth in multimedia traffic volume. As a result of these initial efforts, in 2012, the European Telecommunication Standards Institute (ETSI) proposed the NFV framework. In the document produced, the ETSI working group outlined the overarching goal of NFV: leveraging IT virtualization standards to consolidate various types of equipment into a new industry standard for high-volume servers, storage systems, switches, routers, and other network elements. These elements can be deployed across network nodes, data centers, and routers or switches referred to by operators as Customer Premises Equipment (CPE), which are installed on the client’s or end user’s premises (at the network Edge).

This initiative was driven by the extensive variety of proprietary hardware and software included in CPEs, which posed several challenges for operators. These challenges included the constant reinvestment in technological upgrades (CapEx - Capital Expenditure) that could not always be passed on to enterprise and public sector clients, as well as ongoing expenditures in training and recertification of specialized human resources. These factors highlight the fundamental motivation behind the development of NFV.

Currently, the main driver of NFV is the 5G cellular network. NFV is a fundamental part of the 5G network and, in fact, one of the requirements of its standards. NFV is built on the standards of machine virtualization (

VM - Virtual Machines) technology,

Figure 3 , extending its use into the network domain, such as: firewalls, caching, DNS, points of presence with web content (or

CDN - Content Delivery Networks), intrusion detection, etc., decoupling them from hardware or proprietary equipment to software solutions running on VMs [

12].

It is recommended that researchers interested in developing deeper research into NFV architecture study [

13,

14].

3.5. Wi-Fi Networks (5/6) and WSNs, Wireless Sensor Networks

Wireless networking technologies, widely studied and popularly known as Wi-Fi, encompass standards such as the extensively used Wi-Fi 4 and 5 (or IEEE 802.11 b/n/g) as well as the latest implementations like Wi-Fi 6 - IEEE 802.11ax. These technologies culminate in a vital byproduct that supports users’ daily activities: Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) in the IoT ecosystem - WSNs [

11], along with relevant protocols and [

15], are designed to integrate seamlessly into use cases for Smart Buildings and, with the advent of 5G-IoT, into broader smart city infrastructure.

Figure 3.

Intelligent Edge Computing, SDN without the Fog layer, NFV and IoT devices [

12].

Figure 3.

Intelligent Edge Computing, SDN without the Fog layer, NFV and IoT devices [

12].

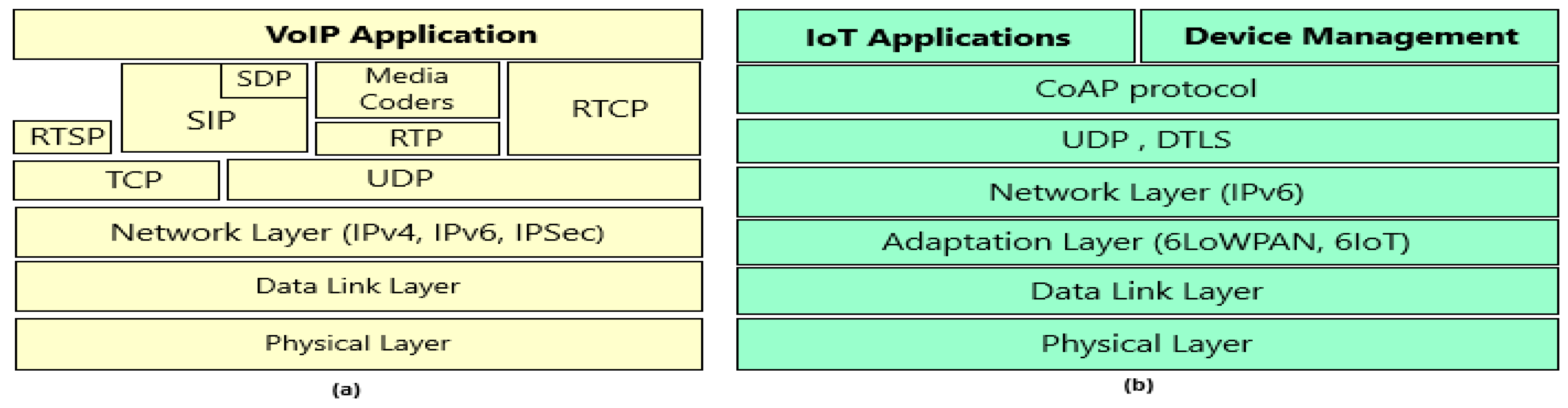

3.5.1. IoT Protocols: CoAP and MQTT in IoT and WSN and IoT Management

Wireless networks that control and interact with IoT devices, including wireless sensors and actuators, are becoming increasingly common. Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) are now widely adopted in

Smart Factory, Smart Farm, Smart Grid, and Smart Building implementations. These networks and infrastructures utilize various configurations, such as mesh and non-mesh, while advancing significantly in routing protocols tailored for WSNs. For further insights, refer to the studies in [

2] and [

16].

The CoAP (

Constrained Application Protocol) protocol of the IoT world, defined by the IETF in RFC7252 [

17] and with updates in subsequent RFCs: RFC 7959 and 8613, is a lightweight information transfer protocol designed for the Internet and integrates with the

http protocol using message exchange, supporting multicast traffic,

Figure 4. These protocols are of particular interest in the case of SB use, being used in restricted environments of various types of IoT devices, that is, an inhospitable environment subject to interferences,packet loss, noise, less CPU processing use and low transmission power.

The CoAP protocol supports devices with little RAM, high error rates and is used in IoT, and networks with low data transfer rates. The motivation for using CoAP is to bring the RESTful (Representational State Transfer) communication paradigm to smart objects, such as the IoT. Recalling the main idea of RESTful resource representations, they are exchanged between a server and an IoT device at the edge (client on the network).

CoAP integrates with the HTTP protocol, with support for multimedia traffic and low additional overhead. This message exchange is very similar to those known from HTTP. It meets the requirements for

M2M - Machine-to-Machine Internet protocols, uses the UDP protocol with support for both multicast and optional unicast traffic, also allowing the exchange of asynchronous messages. It has simple and low-complexity headers, allows stateless http, that is, without any state, allowing a possible proxy to access CoAP resources through the HTTP protocol [

18].

3.6. Types of IoT Devices: (1) Low-End, (2) Middle-End and (3) High-End

Memory capacity and processing units are essential characteristics of embedded IoT devices, enabling them to perform the basic tasks required for proper functionality.

The study presented in the IEEE article [

19] categorizes a wide range of models and manufacturers, widely adopted in the current decade, into three distinct groups and highlights their key features, advantages, and disadvantages: low-end [

20] (1), middle-end (2), and high-end (3). These categories are exemplified and recommended for the use case discussed in

Section 6 on Smart Buildings.

3.7. Voice Over IoT—VIoT and Video Over IoT

Real audio and voice traffic over IP operates through applications packaged by the protocol utilizing Voice over IP (VoIP) technology, running on network or Internet infrastructures [

21]. Over the years, this has expanded with IPv6, distinguishing itself through client-to-client addressing and connectivity. Regarding IoT devices, as previously discussed, there are

middle-end or

high-end boards or embedded devices and applications capable of running protocols such as RTP (Real-Time Protocol), SIP, and others. Applications with robust performance are referred to as

VIoT (Voice over IoT), featuring VIoT gateways that internally implement an SIP client to scale it, as detailed in [

22].

However, the integration, availability, response time, and cost-effectiveness of a VIoT implementation are not necessarily straightforward. For example, in the case of Smart Building (SB) use case, there is significant research potential in the integration of VoIP (SIP) with the IoT edge or, more advanced, audio and video streaming, as well as the emerging video over IoT, which involves multimedia protocols, video compression, and related technologies. To simplify implementation and account for critical, simultaneous data traffic on the same network, a QoS (Quality of Service) mechanism must be deployed. This mechanism ensures an optimal /textitQoE (Quality of Experience) for the services provided to users by the service provider.

Figure 4.

(a) Protocol stacks SIP(IP, RTP - VoIP) between a SIP Server and the client device, (b) Protocol stacks IoT - IoT devices and an associated IoT application Server.

Figure 4.

(a) Protocol stacks SIP(IP, RTP - VoIP) between a SIP Server and the client device, (b) Protocol stacks IoT - IoT devices and an associated IoT application Server.

3.8. Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL)

Machine Learning (ML) enables computers to learn from data through optimization techniques or control mechanism by leveraging calculations and weight adjustments. ML, along with its subcategory

Deep Learning (DL), has captured significant attention in recent years, particularly in the fields of data communication networks, audio signal processing, voice, and video over IP. Given that networks play a fundamental role in distributed learning systems—including collaborative learning at the edge, whether via Fog Computing or IEC - it is understandable that research in this area has seen substantial growth [

23].

With the advent of cloud computing and the adoption of application architectures based on containers, companies and research centers have observed increasing complexity in network infrastructures and data centers, along with their configurations and the rapid expansion of applications operating within this new architecture. This scenario demands network intelligence with a more holistic perspective to address critical issues effectively.

The complexity is already evident in metropolitan wireless networks, large public or private spaces, and smart cities, particularly with the explosion of 5G and 5G-IoT networks [

5]. This complex environment presents a fertile field for research, especially in the context of distributed application approaches.

3.9. Containers and Cloud Microservices Architecture

In the case of applications controlling IoT devices within a Smart City or Smart Building, as well as in Smart Grid or Smart Factory scenarios, an important middleware software component known as

the Content Broker(CB) plays a key role. The CB acts as middleware between software systems, databases, and various IoT applications. On the other edge, it manages IoT devices through protocols such as CoAP, SIP/RTP or MQTT, enabling real-time data collection and transmission with low latency. The European organization

Fiware.org [

24] has gained prominence in recent years for its reference architecture, which incorporates the Fiware Content Broker, known as

Orion. In the subsequent case study on Smart Buildings, a simplified architecture will be adopted, leveraging CBs for integration with both Fog Computing and IEC. However, integrating and utilizing SDN with Fog or IEC remains an open research area, in spite of being a decisor parameter on SB study case.

The rationale behind the research techniques proposed in this study lies in addressing the challenge of selecting the most suitable network architectures and solutions between Cloud and Edge Computing, given the current state of the art in technology. Additionally, a secondary objective is to contribute to the positioning and development of real-time multimedia applications at the network edge, using high-performance IoT devices. For example, the proposed application of Voice over IoT (VIoT) gateways serves as a very interesting case study to understand its behaviour on SBs [

22].

4. A Comprehensive Survey and Related Works

In summary, considering the referenced research, the articles originating from IEEE studies and others related to the present study were selected, presenting the indicated references and the problems presented, as well as their respective solutions. This research will be the effective

procedure for validating the solutions adopted in the cells of

Table 1 of

Section 6. The discussion follows with the six primary references of the chosen research and brief comments:

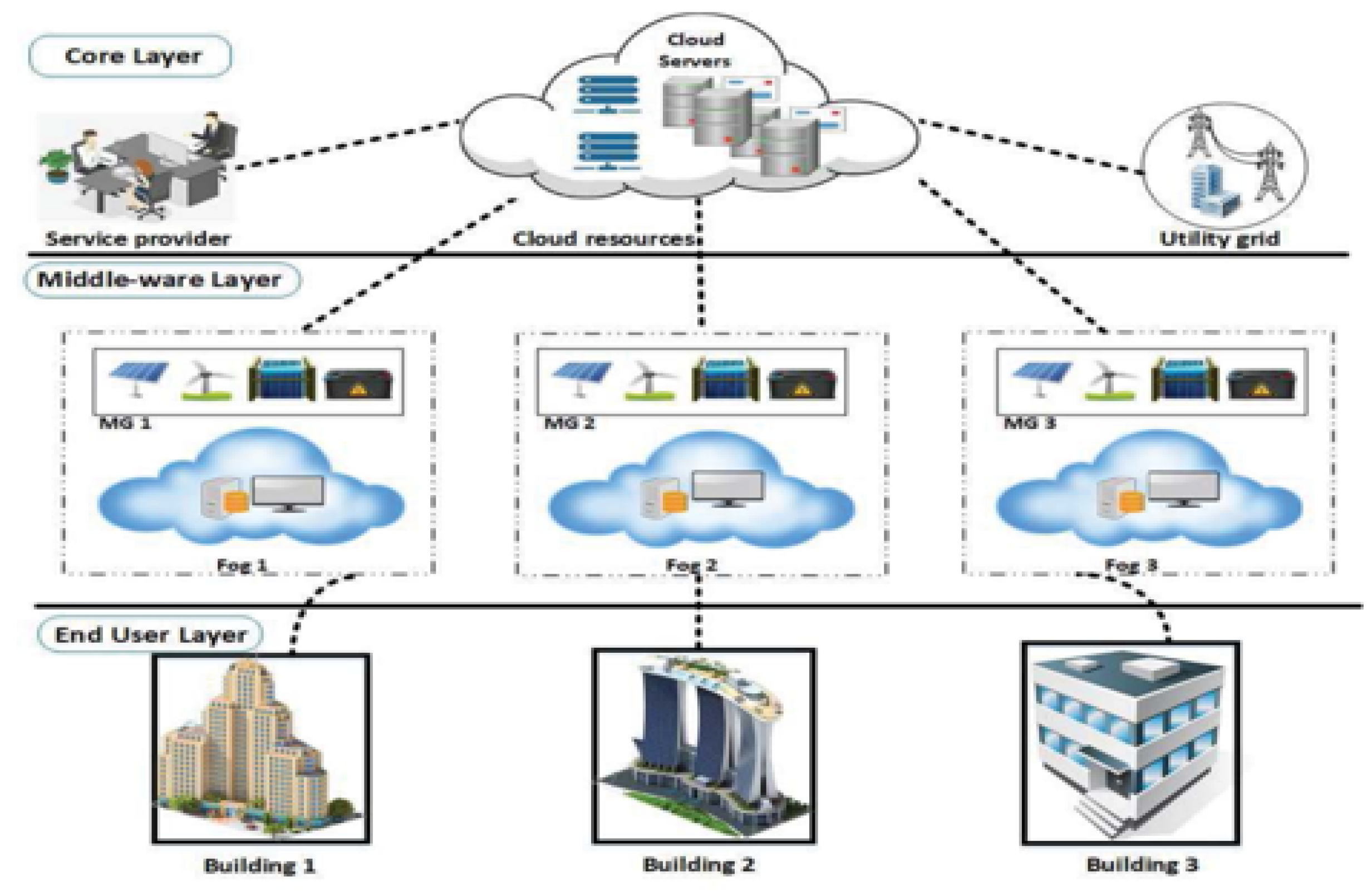

In their article [

2], Dutta et al. explore the architecture of Fog and cloud-based systems for A Smart City, culminating in a simplified case study of a smart building. The authors highlight the significant volume and variety of data generated by smart building (SB) sensors, advocating for the use of Wireless Sensor Networks where feasible. Their proposed architecture, in our interpretation, leans more heavily on Industrial Edge Computing (IEC) than Fog computing—a common observation in the literature, given the frequent interchange of acronyms and architectural models. They conclude with the implementation of a small-scale system or prototype, detailing the roles of both cloud and Fog layers, see [

25,

26].

The article [

27] and secondary reference [

5] offer a more structured delineation of application layers (Cloud and PaaS) residing in the cloud, the Fog layer, and the Internet of Things (IoT) device layer. These works highlight key concepts such as Mobile Cloud Computing (MCC), Mobile Edge Computing (MEC), Mist computing, and cloudlets, driving substantial research between 2017 and 2022. Furthermore, [

27] delves into the design of intelligent edge systems for smart cities, promoting the use of

data analytics to enhance urban management and decision-making. The implementation of

surrogate nodes (or Fog nodes) is deemed crucial, alongside the challenge of developing applications for highly dynamic environments. This necessitates addressing technological gaps in existing systems designed for cloud deployment, rather than Fog or IEC environments. The authors ultimately propose a novel programming model to solve this issue.

To further clarify this discussion, K. Shafique et al. [

5] complement the overview by addressing heterogeneous networks:

HetNets, M2M, and NB-IoT (Narrowband IoT), and the new landscape emerging with the advent of 5G cellular networks, leading to new technologies such as

Software Defined WSN and the use of ML and DL. Beyond the requirements for achieving optimal QoS in the proposed new 5G-IoT implementation for high data rates, based on large volumes of IoT devices [

28], the authors highlight real-world applications and modules for s

smart Cities, Buildings, homes [29], Grids, Health, Transport, and smart Industry, including a brief history of network evolution from 2G to the current 5G standard.

Regarding network convergence and the integration of cloud, edge, and fog computing, a study [

12] explores opportunities to apply Deep Learning methods across various network layers. The researchers delve into the potential of utilizing DL in fog or edge computing. Recommended application areas include online content delivery, streaming, routing control, traffic control, and QoS optimization. The study presents compelling results on its tables about edge optimization using DL in various application scenarios and models, showcasing the advantages of bringing decision-making closer to the network edge

Yasmeen et al.’s 2018 study [

30] aligns well with the Fog-based approach advocated in this research for a federation or geographically proximate set of smart Buildings . The authors propose a Fog-integrated

smart Grid application model, dividing it into the three well-known layers: the end-user layer (or SB layer in this study), the Fog layer, and the cloud-based central layer, see

Figure 5 [

30]. They propose novel load balancing algorithms and conduct response time simulations using a newly proposed tool,

CloudAnalyst. This work suggests a promising avenue for future research.

Focusing on the network edge and IoT device deployment, the Italian study [

19] provides a valuable overview of globally deployed devices. It presents a comprehensive review of various vendor models, categorized into

low-end, middle-end, and

high-end devices based on features as computational power, memory, and storage. This study highlights the rapid technological advancements, including sensor technology, in embedded IoT board development. This provides a crucial informational foundation for implementations and adoption in the smart Building use case of this research.

Subsequently, Camerlynck et al. [

22] propose a

VIoT (Voice over IoT) framework, aiming to integrate Voice over IP (VoIP) with advanced services such as unified communication, collaboration, and omnichannel capabilities.

This integration leverages high-performance IoT devices exceeding the capabilities of the middle-end devices described in the previous study, incorporating video calls (audio and video). The authors innovatively explore the convergence of VoIP protocols and IoT device challenges, proposing an integrated architecture by bridging the communication protocols of both domains. This approach informs the design of the virtual concierge and novel VIoT intercom system, with or without video, for security and communication within the SB case study. The authors also detail a mechanism for implementing a VIoT gateway adding a SIP client to facilitate this integration of two worlds.

5. Main Problems and Proposed Solution Using fog Or Iec in Smart Buildings

Following the comprehensive literature review in the

Section 4, this Section addresses key challenges and issues related to the three-layer architecture: Cloud, Fog/IEC, and the user layer with edge IoT devices. The discussion focuses on Quality of Experience (

QoE) for users, solution availability, and associated problems.

Four key challenges, categorized in

Table 1, are identified. The Table’s central cells indicate proposed solutions for each application category described in its rows of

Table 1.

These main challenges and issues include:

a. Network relevant noise and Jitter: Significant jitter, noise, and interference from the SB’s Wi-Fi network and other unforeseen sources may negatively impact communication with the Fog or IEC [

32].

b. Cloud Communication Latency: Latency in communication between the central database,

dashboard, and applications within the Cloud-based Operational Control Center (CCO or OCC) — integrated with the Fog/IEC and interconnected to one or more federated or independent SBs—presents a challenge [

32].

c. QoS and QoE Optimization: Optimizing Quality of Service (QoS) and Quality of Experience (

QoE), particularly for VoIP, VIoT, and short-form video streaming (video over IoT), and ensuring reliable video recording for emergency situations, requires attention [

33,

34].

d. Security and Access Control: Enterprise clients (or federations of SBs) using the Fog layer require seamless access to multiple cloud services through a single authentication mechanism for both users and IoT devices[

35]. Implementing robust security measures is therefore crucial for protecting the privacy of residents, employees, and visitors, and ensuring secure access to SB facilities while maintaining cost-effectiveness [

36].

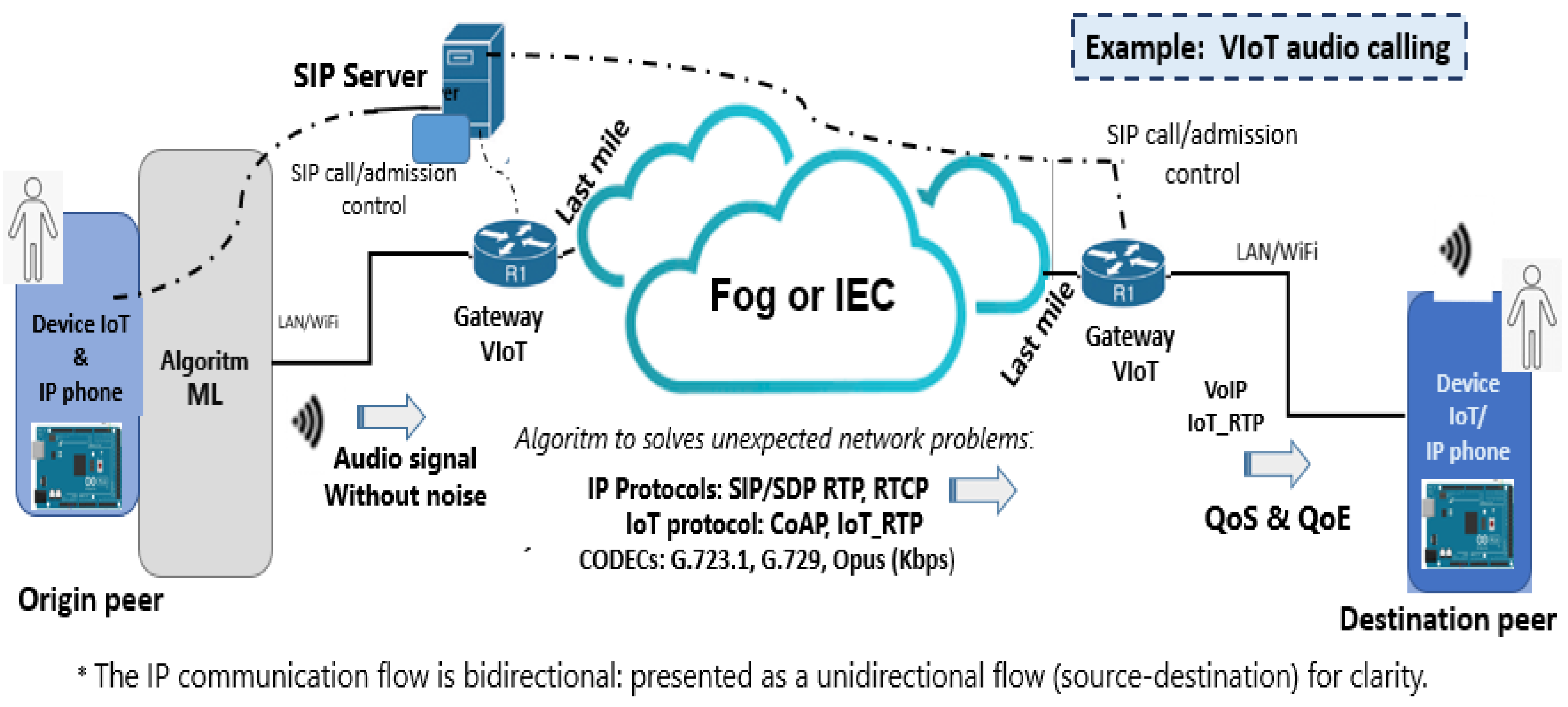

Figure 6 illustrates a general solution to the aforementioned issues and challenges, exemplified by a Voice over IP (VoIP) call. The Figure uses

VIoT as an application example for both Fog and IEC deployments, employing machine learning (ML) algorithms at the call origin to mitigate background noise. Adaptive

IoT/RTCP (Real-Time Control Protocol) protocols are also utilized during the VIoT call.

Figure 6 depicts the main call flow from origin to destination, with the lines (arcs, edges, connections) representing unidirectional or bidirectional VoIP packet streams.

The solutions presented in the cells of

Table 1 directly relate to

Figure 6 .

Table 1, which includes a glossary of abbreviations and acronyms (e.g., Fog with SDN or NFV (

FSN),

FOG, IEC with SDN or NFV (

ISN),

IEC, and

ANY [representing any of the previous architecture alternatives], or

(—-) [not applicable]) further detailed in

Table 2, outlines key challenges and issues in the columns (

itemsa.->d.previously detailed), those must be addressed for one or more SBs and various application categories (rows of

Table 1) within the proposed SB use case. The Table further proposes optimal solutions based on two main implementation approaches:

(i) Intelligent IoT Device Selection: This approach focuses on determining the optimal IoT device category (1)

low-end, (2)

middle-end, or (3)

high-end – as detailed in

Table 2 – to achieve the best cost-benefit ratio. The goal is to avoid unnecessary expenses by selecting the most appropriate category for the various IoT devices deployed within the SB.

(ii) Network Architecture Selection: This approach focuses on selecting the optimal Fog or IEC network architecture for the proposed use case, based on the three-tier cloud computing model: - with Fog or IEC as the intermediary layer, as detailed in the

Table 2. This includes considering the adoption of open Software Defined Networking (SDN) and/or Network Functions Virtualization (NFV) technologies.

The decision to adopt SDN or NFV is complex and is more justifiable for federations of SBs or regional service providers serving numerous SBs within a defined geographical area (e.g., a large neighborhood or municipality). Future work will expand upon this study and refine this central

Table 1 to further aid in decision-making. The optimal implementation decision will depend on factors such as the number of SBs (one or two buildings in close proximity, or a larger geographical complex), the size of the residential/commercial complex, or the scale of a clearly defined federation of SBs within a specific neighborhood, morever the indicated articles research complements this decision-making process.

6. Use Case of One Smart Building (SB) and Its Applications

This Section aims to discuss a simplified use case that applies the results from the

Section 5 and consolidates the research presented in

Section 4. This provides a novel and comprehensive perspective on SBs, paving the way for future advancements considering emerging scientific developments in IoT, Fog, and IEC.

Section 1 examines Smart Buildings (SBs) within the context of

Smart Cities, highlighting their rapid growth internationally, including Europe -

Fiware.org [

24], the USA, and some eastern countries. This growth introduces significant innovation in communication engineering, cloud computing, and high-performance IoT devices.

The proposed SB solution utilizes Voice over IP (VoIP) and video equipment, typically embedded within IoT devices (as detailed in

Section 4 and

Table 1), offering a suitable number of interfaces for easy integration into the SB’s wired and wireless local area networks. These IoT devices, connected by VIoT gateways, integrate IP phones (replacing traditional intercoms and potentially fixed-line phones), temperature and fire sensors, actuators, RFID and biometric readers, analog-to-digital converters for actuator control, IP cameras, and other typical devices adopted in a SB.

Overall, the SB solution aims for secure, robust, and reliable applications with consistent performance and the delivery of excellent Quality of Service (QoS), resulting in a desirable Quality of Experience (QoE) for users. Finally, this use case emphasizes high availability for edge solutions, parameters that should be regularly monitored within service contracts and their Service Level Agreements (SLAs), long-term contracts spanning several years.

To streamline the solution, the scope of the proposed SB is reduced to a single local Server and simple container per application and a single Content Broker. Only the most relevant applications, with direct connectivity to the chosen Fog or IEC architecture, are detailed here:

-

i)

IP telephony and VoIP (see [

37]), video recording, and structured and unstructured database applications.

-

ii)

Directory applications with permissions for various user types, access levels, credentials, and a comprehensive identity and access management (IAM) system [

35].

-

iii)

Centralized control and monitoring dashboards via the Operational Control Center (CCO or OCC) operating on the selected cloud platform.

-

iv)

Visitor authentication applications: biometric authentication,

QR code or physical token access [

35].

-

v)

Applications for SB access control and authorization, including a virtual concierge linked to the CCO or OCC. This may also include user-friendly applications such as smartphone apps and intelligent chatbots, as well as internal IP telephony within the SB’s commercial or residential areas. These cloud services are integrated with local SB Server or desktop (container) to complement the solution.

Alternative architectures could involve a centralized environment through the federation of SBs and Fog nodes, or SBs with internal IECs. The latter is generally suitable for a small number of towers in commercial or residential SBs. For simplification, this proposal and study limit the scope to one or two building towers to be exhaustive.

This results in a comprehensive suite of applications, storage, and high-capacity

data analytics integrated via Fog or IEC with intelligent IoT devices at the SB’s edge. This data is stored in the central cloud database, which interacts with the Fog or IEC [

3].

In the single-tower scenario, an IEC infrastructure is deployed within the SB described in detail on this Section. For security and high-availability of data, voice, and video communication (VIoT and VoIP), redundancy and a reliable fail-safe system are implemented. In the second hypothetical scenario involving multiple SBs, a Fog computing approach or a hybrid Fog and IEC model is adopted; this implementation is out of the scope of this study.

This ensures the necessary SB functionality and acceptable SLA (as contract), minimizing deployment and operational costs, and enabling rapid recovery from disasters to prevent serious problems for residents, such as prolonged power outages (several hours), partial building fires, or unforeseen temporary service disruptions, for example, last-mile network outages or edge server failures, despite the proposed redundancy in a single SB.

Table 1.

An overview of the main issues of SBs adopting: a. the best category of IoT devices; b. preferred architecture: Fog or IEC, c. adoption or not of SDN/NFV. The methodological decision is based on research (referenced articles) and for each cell seeks the best cost-benefit ratio(

see Table 2: on Table below are the acronyms adopted to understand it).

Table 1.

An overview of the main issues of SBs adopting: a. the best category of IoT devices; b. preferred architecture: Fog or IEC, c. adoption or not of SDN/NFV. The methodological decision is based on research (referenced articles) and for each cell seeks the best cost-benefit ratio(

see Table 2: on Table below are the acronyms adopted to understand it).

| Problems (Columns): |

Jitter, Background |

Latency and Packet Loss On |

Security Challenges |

QoS,QoE: Video |

| vs. |

Noise, Wi-Fi and Its |

E2E Communication |

Data Privacy, Governance and |

Streaming and VoIP |

| Application Categories (Lines): |

Interference Signal(SB) |

(SB<>FOG or IEC<>Cloud) |

Access Entrance (SB and Cloud) |

(SB<>FOG);(IEC<>Cloud) |

| (I)Voice and audio(VIoT), VoIP, IP Telephony included the communicaton between devices IoT and SIP Server |

(2) and FSN or IEC |

(2) and FSN or ISN |

(2)(3) and ANY |

(2)(3) and FSN or ISN |

| |

Articles*: [22,23,35] |

articles*: [12,22,23,35] |

articles*: [3,13,20,35] |

articles*: [3,5,14,30,32] |

| (II) Vídeo surveillance, included Virtual concierge (VIoT, vídeo) |

(3) and ANY |

(3) and FOG or FSN |

(–) and FOG or FSN |

(3) and FOG or FSN |

| |

articles: [16,30,31,38] |

articles: [16,18,38] |

articles: [2,16,26,35] |

articles: [5,18,30] |

| (III) Video recording (Virtual concierge with VIoT, Vídeo) |

(3) and ANY |

(3) and IEC or ISN |

(–) and FSN or ISN |

(3) and FSN or ISN |

| |

articles: [10,16,29,30,38] |

articles: [8,18,30,38] |

articles: [2,16,30,35,38] |

articles: [2,5,18,26] |

| (IV) Chatbot Integrated with CCO and Cloud DB/VoIP on SB and Virtual concierge |

(1)(2) and FOG or FSN |

(1)(2) and ANY |

(1)(2) and FOG or FSN |

(–) and ANY |

| |

articles: [12,24,27,29,31] |

articles: [4,24,30,38], |

articles: [19,24,30,31] |

articles: [3,5,14,30] |

| (V) Biometrics Identification and Entrance authorization | Virtual concierge (SB) |

(2)(3) and FOG or FSN |

(2)(3) and FOG or FSN |

(2)(3) and FOG or FSN |

(2)(3) and ANY |

| |

articles: [16,34,38], |

articles: [10,16,30,34] |

articles: [4,14,16,35] |

articles: [3,5,20,30] |

| (VI) Light control, Environment control, the water pumps (SB common facilities) |

(1) and (–) |

(1)(2) and (–) |

(2) and (–) |

(–) and (–) |

| |

articles: [6,16,27] |

articles: [11,16,19,24] |

articles: [4,19,36] |

articles: Not Applicable (n/a) |

| (VII) WI-FI Network, temperature/fire sensors and actuators, leisure area, gym, swimming pool(pumps) |

(1)(2) and FOG or IEC |

(1)(2) and FOG or FSN |

(1)(2) and ANY |

(2) and ANY |

| |

articles: [5,16,19,21], |

articles: [5,16,19] |

articles: [5,14,20,36] |

articles: [5,16,19,32] |

| (VIII) Building application (SB Visitor registration, Virtual concierge communication, |

| Smartphone-based applications for SB access, information retrieval, and delivery/mail services |

(1)(2) and FOG or IEC |

(1)(2) and FOG or FSN |

(1)(2) and FOG or IEC |

(1)(2) and FOG or IEC |

| |

articles: [16,24,27,30,38], |

articles: [2,4,18,28] |

articles: [2,5,14,31] |

articles: [5,24,30,32] |

|

(*)Validation Procedure:The referenced articles [n] offer further discussion and can aid in the technical selection of the optimal solution

|

| for each Table cell, in conjunction with other factors detailed in the Smart Building Use Case Section. |

|

|

|

|

The values in each cell of

Table 1 reflect the findings from the literature review in

Section 3 and represent an optimized decision based on three factors: quality, performance, and minimized cost for the SB solution, IoT device, and chosen Cloud solution. A glossary of abbreviations and acronyms is provided in help

Table 2.

Table 2.

Classification of IoT

devices categories and recommended Cloud architecture in

Table 1.

Table 2.

Classification of IoT

devices categories and recommended Cloud architecture in

Table 1.

| Classification of IoT and subtitles of Tabela 1 (IoT), |

| IoT devices: Category of the Embedded boards: |

| (1) = Low-end IoT device

|

| (2) = Middle-end IoT device

|

| (3) = High-end IoT device

|

| ANY = any of 3 categories could be applied |

| Acronyms for Architecture, Cloud architecture and Integration: |

| FSN = Fog + SDN (or NFV) |

| FOG = Fog without SDN (or NFV) |

| ISN = IEC + SDN (or NFV) |

| IEC = IEC without SDN (or NFV) |

| ANY = any of above Cloud solution could be chosen |

| (–) = N/A Not applicable |

Further research is needed to evaluate the quality of service, higher uptime and SLA aspects, representing a promising area for future investigation.

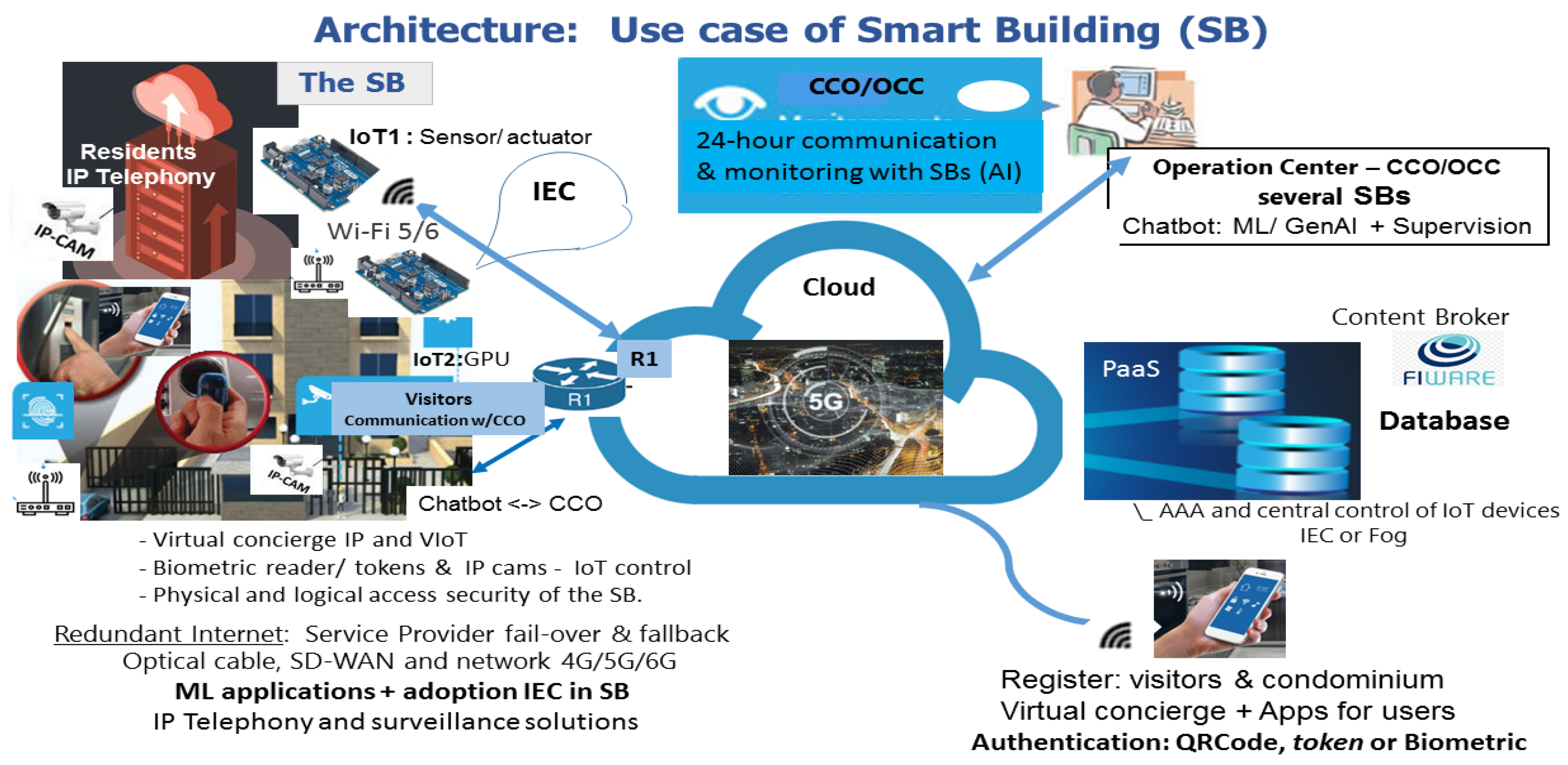

The network architecture, depicted in

Figure 7, incorporates

failover and

fallback mechanisms. Failover utilizes a redundancy system, while fallback employs a secondary terrestrial communication link from a different provider (e.g., a fiber optic cable as the primary link and any available radio-link or satellite solution as failover), using 4G/5G and future 6G cellular networks in the SB’s router. For medium and large cities, redundancy is achieved using two distinct carriers or at least a secondary local Internet Service provider. In rural areas, a failover link using microwave radio/tower networks may be necessary, supplementing the primary connection (fiber optic or other technology).

The proposed SB architecture in

Figure 7 includes connections to cloud computing. For simplicity, the Figure does not show all Fog components in detail, although it may be included in the deployment.

Figure 7 shows a general example of the SB (left side of the figure), where the proposed IEC (

Edge) resides within the SB and is directly connected via router R1 to the cloud. This topology is applicable to one SB or, at most, two SBs.

The SB’s router or VoIP gateway connects to the two redundant carriers mentioned. Only in the case of integration with a geographically proximate Fog node it provides access to that Fog and enable integration with federated SBs.

However, in the second proposed IEC topology, computation and processing are handled by an IEC or Edge device deployed internally within the SB, as described in [

2,

38]. In this case, the last-mile router R1 connects directly to the external network or the Internet, and to the central cloud solution. While a three-layer Cloud architecture is maintained, the IEC simplifies implementation by reducing the number of accesses to the central network. The adoption of SDN architecture with its switches, where feasible, is recommended to reduce costs through the use of open platforms for internal and external routers and switches. The manageability and administration of the solution are crucial; from a technical standpoint,

billing and technical support is delegated to the local provider

Visitor registration and scheduling will be handled by mobile applications available in smartphone app stores and through readily available market APIs, facilitating easy authorization and registration of visitors and new residents by the building’s residents.

This SB context is managed by a Operational Control Center (CCO or OCC), at the top of

Figure 7) of the solution provider, shared among one or multiple SBs. Furthermore, the central databases of actors and their credentials, obtained from Directory Services (

Active Directory, AD), are implemented in the cloud Database -

DB (see same Figure), connected by small local or remote replicas of the Fog or the IEC itself.

Some of the SB’s functionalities under study are summarized in

Table 1,

Figure 7, and described in this Section as a use case for these SB applications.

One of the most prominent SB solutions employing large-scale IP technology is VoIP calling within the condominium or between buildings (which may be federated within the same architectural complex). This is implemented using SIP client devices (see

Table 1). The virtual concierge adopts IoT technology with integrated microphones and speakers, enabling audio and video connection with the CCO or OCC; see the call flow in

Figure 7. Within the SB, an IP-PBX/SIP server controls call admission and addressing between IoT devices and SIP clients (e.g., extensions 01-999) and IP phones using or not IoT devices together (replacing traditional TDM intercom systems).

Another interesting feature is the centralized billing procedure, managed within the database and accessed by the Operational Center administrator. This billing information is sent to the condominium residents from the CCO, detailing water, electricity, and gas consumption, separated by unit and measured by IoT-equipped control devices (meters and sensors) in each condominium unit. The CCO automatically generates and sends monthly electronic invoices to each resident’s email address using their system credentials (AD users).

The important choice of adopting an IEC or Fog computing approach in the simplified SB follows the solutions chosen during the research and outlined in

Table 1 , along with its evolution concerning the types of IoT devices,

5G-IoT [

5], VIoT, SDN, gateways, containers, etc. Further studies are needed to provide greater scientific depth to the research conducted thus far.

The results obtained from research articles, for example, on a solitary SB, are linked to the network architecture adopted for this scenario: where Edge Computing (or IEC) alone reduces latency and

jitter in the growing data, voice, and video traffic. It is important to note that the local integration of various networks (Wi-Fi, WSN, and wired network where necessary) within the SB still needs review, given that all critical computational aspects, including computing, processing, and storage, are implemented at the network edge. A review of the cells marked with IEC in

Table 1 is necessary at this point.

7. Conclusions

This study concludes that, in the case of a federation or a group of

Smart Buildings, the strategy of using Fog Computing with IoT devices of the three types mentioned (1) to (3) in

Table 2, intelligently and sparingly at the Edge, is the best solution. It is also recommended to complement this strategy with the adoption of SDN by service providers and cloud vendors.

Conversely, for standalone Smart Buildings with a limited number of properties per tower (estimated at 20–60 units), the study concludes that a strategy employing IEC and IoT devices of types (1) and (2) at the Edge, leveraging simpler technological solutions within this condominium category, represents the optimal approach. Generally, these isolated SBs are sensitive to operational costs and initial investments. The adoption of open SDN architecture by cloud providers maintains the consistency of this approach and should be strongly considered.

NFV, in agreement with telecommunication companies, can also be adopted for both scenarios, resulting in reduced operational costs and technological advancement without requiring significant hardware and software reinvestment after a certain number of years following initial Smart Building implementation. Decision-making should consider the advent of 6G, 5G, 5G-IoT cellular networks, and new fiber optic implementations within Smart Cities, which may introduce both innovative solutions and new challenges to the current landscape.

The future challenge, in countries such as Brazil, will be to balance investments in innovative 6G, 5G-IoT, SDN, NFV technologies associated with Fog and IEC. Effective service availability for enterprise, medium businesses and users will be achieved through economies of scale coupled with innovation, leading to lower-cost solutions.

A key challenge will be to extend this strategy and the scientific advancements presented in this study of SB(s) to a larger scale within Smart Cities, ideally coordinated through a public-private partnership leveraging the technological progress of emerging Smart Buildings within a specific geographical area.