Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- RQ1.

- Are the Spanish National Curriculum Guidelines for EFL pronunciation instruction at primary school level adequately scaffolded and coherent across AACC?

- RQ2.

- What are teachers’ beliefs and practices towards EFL pronunciation instruction in the New Curriculum, and are there differences between public and private schools and/or between AACC?

3. Results

3.1. The LOMLOE and Its Regional Adaptations

3.2. Beliefs About EFL Pronunciation Instruction in the New Curriculum

-

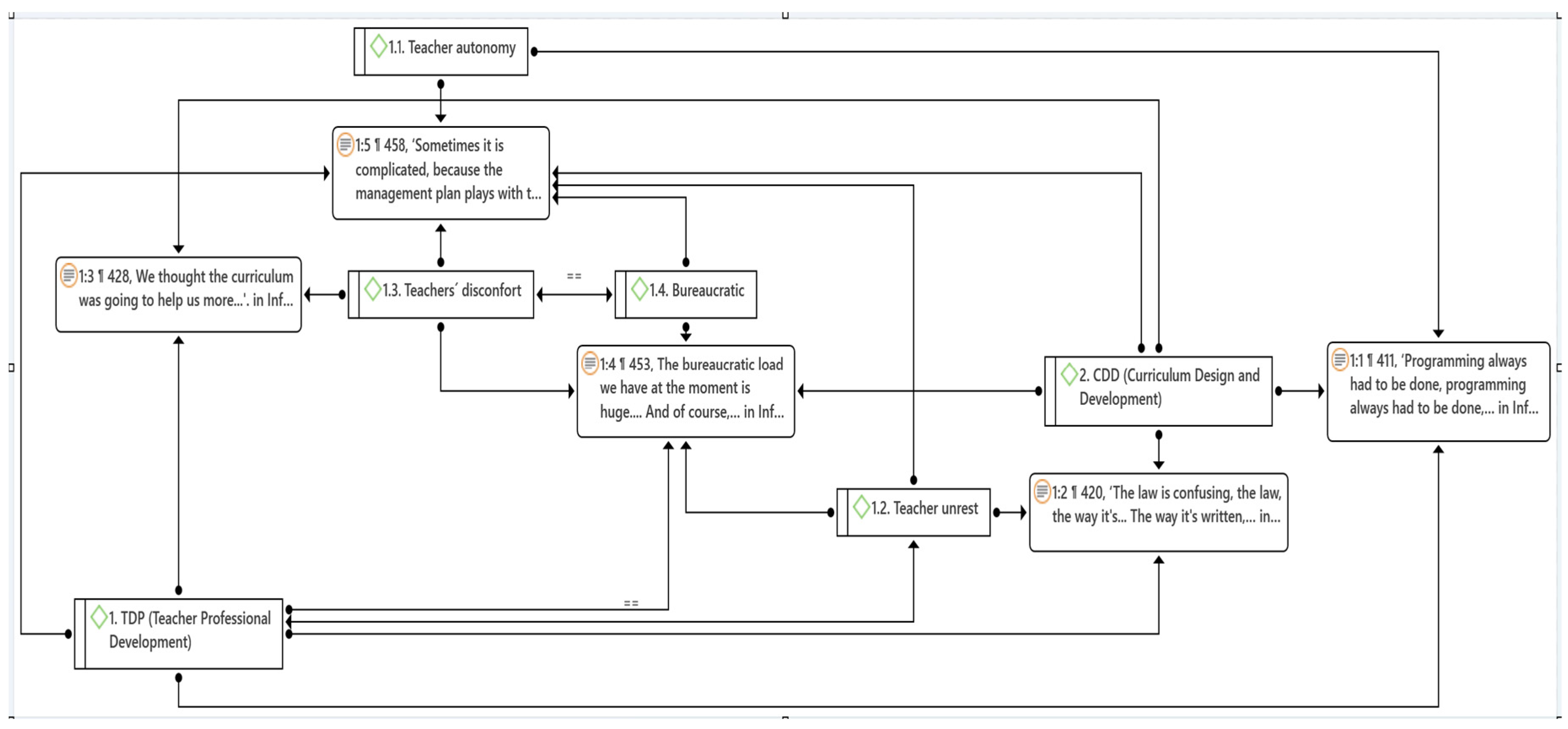

Curriculum Design and Development (CDD) (278 quotations), referring to the structure or organization of the curriculum, as well as to the planning, implementation and evaluation processes of the curriculum (Mohanasundaram, 2018), and covering the following (sub)codes and corresponding topics (in decreasing frequency):1.1. Contents of the English Curriculum1.1.1. Pronunciation1.1.2. Phonetics1.2. Methodological principles1.7. Resources and Didactic Materials1.7.9. Publishing houses1.7.1. Textbooks1.7.29. Constraints1.9. Technology and digitalization1.6. Timing1.6.3. Teaching Load1.5.5. Ratio of students

-

Teacher Professional Development (TPD) (100 quotations), referring to the attitudes, commitments and actions involved in the teaching career in which professionals go through different stages, both autonomously or self-directed and collectively with the supports of others since teaching is a collaborative profession (Van Ha & Murray, 2021), which registered the following most relevant (sub)codes and topics:2.1.11. Teacher Autonomy2.1.9. Teacher Unrest2.3.2. Control2.3.3. Bureaucracy

4. Discussion

4.1. EFL Pronunciation Curriculum

4.2. Methodologies

4.3. Resources and Didactic Materials

4.4. Professional Training

4.5. Professional Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| AACC | Pronunciation contents |

| Andalusia |

A. Communication block 1st year LE.02.A.8. Basic sound, accentual and intonation patterns in common use, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. The search for the terms sound patterns reports data referring to Interculturality: Participate, in a guided way, in simple dialogues and conversations about familiar topics, using some repetition supports, reproducing sound patterns, with basic intonation and rhythm and using some non-verbal techniques, favoring the ability to show empathy. Learning situations are not specified, nor is supplementary information on phonics. In addition, reference to sound patterns is also made in the Intercultarality block. |

| Aragon |

A. Communication block 1st cycle Phonetic-synthetic methods are recommended to teach children in a multisensory way: through image, movement, and sound. Each sound may be represented separately in action, using a picture with the grapheme and a picture beginning with that sound) and a short song, which allows children to learn the sounds more easily and helps them to remember them for later reading. This approach also allows students to learn the movements of each letter in a more entertaining way. Coordination with the early childhood stage is necessary in this respect. 2nd cycle: Basic sound, accentual and intonation patterns in common use (particularly in questions) in association with their communicative functions, using phonic-synthetic methods in vertical coordination. 3rd cycle: Basic sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns commonly used (particularly third person and simple past inflectional endings, as well as the prosody of questions) in association with their communicative functions, using phonic-synthetic methods in vertical coordination |

| Asturias |

A. Communication block 1st cycle: Introduction to elementary sound and accent patterns. 2nd cycle: Basic sound, accentual and intonation patterns in common use, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. 3rd cycle: Basic sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. Basic strategies for identifying, organizing, retaining, retrieving, and using linguistic units (lexis, morphosyntax, sound patterns, etc.) based on the comparison of the languages and varieties which make up the personal linguistic repertoire. Learning situations and syntactic-discursive structures are not made explicit. |

| Balearic Islands |

A. Communication block 1st cycle: Introduction to elementary sound and accent patterns. 2nd cycle: Basic sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. 3rd cycle: Basic sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. There is no further specification of possible learning situations or further specification of sound and phonetic patterns. |

| Basque Country |

A. Communication block 1st cycle: Introduction to the elementary sound and accent patterns; basic sound, accent and intonation patterns in common use, and the general communicative functions associated with these patterns. 3rd cycle: Basic sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. Express orally with sufficient accuracy, fluency, pronunciation and intonation simple, structured, understandable, coherent and appropriate to the communicative situation texts in order to describe, narrate, argue and inform, in different media, using verbal and nonverbal resources, and making an effective and ethical use of language. Interest and initiative in carrying out communicative exchanges through different media with speakers or students of the foreign language with appropriate pronunciation, rhythm and intonation, respect for basic spelling conventions and care in the presentation of texts. B. Multilingualism block 1st cycle: Introduction to the basic strategies of identification and use of linguistic units (lexicon, morphosyntax, sound patterns, etc.) from the comparison of the languages and varieties that make up the personal linguistic repertoire. 2nd cycle: Basic strategies in common use to identify, retain, retrieve and use linguistic units (lexis, morphosyntax, sound patterns, etc.) from the comparison of languages and varieties that make up the personal linguistic repertoire. |

|

Canary Islands |

A. Communication block Introduction to elementary strategies to identify and use linguistic units (lexis, morphosyntax, sound patterns...), based on the comparison of the languages and varieties that make up the personal linguistic repertoire; sound patterns are also mentioned on several occasions in the specific competencies: the aim is for students to make use of their individual linguistic repertoire and establish relations with the foreign language using lexis, morphosyntax or sound patterns. In the three cycles the same statement is repeated in the specification of basic knowledge: 7. Development of basic sound, accentual and intonation patterns in common use, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. But there is no complementary information, nor is there any breakdown of more specific knowledge. |

| Cantabria |

A. Communication block 1st cycle: Introduction to elementary sound and accent patterns. 2nd cycle: Basic sound, accentual and intonation patterns of common use, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. 3rd cycle: Basic sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. |

| Castile-Leon |

A. Communication block 1st year/course: Introduction to basic and elementary sound and accent patterns: songs, rhymes, riddles, tongue twisters and other oral resources from the cultural tradition of the foreign language. 2nd year: Introduction to elementary sound and accent patterns: songs, rhymes, riddles, tongue twisters and other oral resources from the cultural tradition of the foreign language. 3rd year: Basic and simple sound, accentual and intonation patterns in common use, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns: rhymes, tongue twisters, songs, riddles, resources of oral and written tradition. 4th and 5th years: Basic sound, accentual and intonation patterns in common use, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns: rhymes, letters, tongue twisters, songs, riddles, resources of oral and written tradition. 6th year: Basic sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns and general communicative functions associated with these patterns, such as rhythm, sonority of the language through rhymes, rhymes, tongue-twisters, songs, riddles and resources from the oral and written tradition. |

|

Castile- La Mancha |

A. Communication block 1st cycle: Introduction to elementary sound and accent patterns. 2nd cycle: Basic sound, rhythmic, accentual and intonation patterns in common use, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns and basic orthographic conventions in common use and meanings associated with formats and graphic elements. 3rd cycle: Basic sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns and basic orthographic conventions and meanings associated with formats and graphic elements. There are no explicit sections referring to learning situations or syntactic-discursive structures referring to the phonetics of the language. |

| Catalonia |

A. Communication block 1st cycle: 1st and 2nd years: Recognition, analysis and use of commonly used sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns, and general communicative meanings and intentions associated with these patterns, in informal and semi-formal situations. 3rd cycle: 5th and 6th years: They do not appear. Likewise, there are no explicit learning situations or examples of syntactic-discursive structures in the document. |

| Extremadura |

A. Communication block 1st cycle: Elementary sound and accent patterns (initiation). Elementary communicative functions and intentions associated with these patterns. 2nd cycle: Basic sound, accent, and intonation patterns in common use. General communicative functions and intentions associated with these patterns. 3rd cycle: Common sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns. Functions and communicative intentions associated with these patterns. Common spelling conventions. Common meanings associated with formats and graphic elements. B. Interculturality block 1st cycle: Recognition of the basic characteristics of the foreign language: spelling and pronunciation. 2nd and 3rd cycles: No examples of learning situations or syntactic-discursive structures. |

| Galicia |

A. Communication block 1st cycle: 1st year: Introduction to elementary sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns. 2nd year: Introduction to elementary sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns. 2nd cycle: 3rd year: Basic sound, accentual and intonation patterns in common use, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. 4th year: Basic sound, accentual and intonation patterns in common use and general communicative functions associated with them. 3rd cycle: 5th and 6th years: Basic sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. B. Multilingualism block 3rd cycle: 5th and 6th years Basic commonly used strategies for identifying, organizing, retaining, retrieving and using linguistic units (lexis, similar phonemes, morphosyntax, sound patterns, position of question and exclamation marks) by comparing the languages and varieties which make up one’s personal linguistic repertoire. Learning situations or supplementary information on phonetics and/or sound patterns are not specified. |

| La Rioja |

A. Communication block 1st cycle: In addition to the information on syntactic-discursive structures, a section on mastering the sounds of the English language is added as a differentiating element: Introduction to the recognition of the 44 sounds. Vowel sounds, consonant sounds. 2nd cycle: In addition to the information on syntactic-discursive structures, a section on the mastery of the sounds of the English language is added as a differentiating element: Oral, written and monomodal knowledge of the 44 sounds. Vowel sounds, consonant sounds. 3rd cycle: In addition to the information on syntactic-discursive structures, a section on the mastery of the sounds of the English language is added as a differentiating element: Oral, written and multimodal mastery of the 44 sounds: Mastery of blending and segmenting. Writing long vowels. Intelligible pronunciation when communicating in simple everyday situations, provided that the interlocutor tries to understand specific sounds. Interest in expressing oneself orally with appropriate pronunciation and intonation through narratives or personal experiences, popular texts (stories, sayings, poems, songs, riddles). Pronunciation of the regular past tense. Importance of L1-L2 contrasts involving accent, rhythm and intonation, which may affect intelligibility and require the collaboration of interlocutors. |

| Madrid |

A. Communication block 1st cycle: Utterance of words and short, simple messages with correct pronunciation, intonation, accentuation and rhythm. Participation in classroom conversations. Strategies for understanding key words and simple messages produced with different accents in the English language; Introduction to elementary sound and accent patterns. Basic phonetic differences in the English language through sound groups, words and simple sentences. Words sharing a common pattern, rhyming words and final phonemes. Songs, rhymes, rhymes, humming, tongue twisters, basic jokes, poetry, accompanied by facial and body gestures, mime and initiation into elementary spelling conventions. The sound and name of the letters of the alphabet. Use of capital letters, full stops and other punctuation marks. 2nd cycle: Delivery of key words, phrases and information in short messages with correct pronunciation, stress, intonation and rhythm. Strategies for understanding messages produced with different accents of English. Basic sound, accent and intonation patterns in common use, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. Basic phonetic differences in the English language through words, simple sentences, songs, rhymes, rhymes, strings, tongue twisters, basic jokes, poems, comic quatrains (limericks), accompanied by facial and body gestures and mime. Reading, spelling and recognition of words sharing a common pattern, rhyming words and final phonemes. Basic commonly used spelling conventions and meanings associated with formats and graphic elements. The sound and name of the letters of the alphabet. Spelling. Correct use of punctuation, capital letters and apostrophes. 3rd cycle: Utterance of key words, sentences, messages, frequently used everyday expressions with correct pronunciation, stress, intonation and rhythm using simple connectors in English. Basic sound, accent, rhythm and intonation patterns and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. Phonological aspects: sounds, rhythm, intonation, and accentuation of words in sentences frequently used in the classroom, through songs, rhymes, tongue twisters, jokes, riddles, poetry, comic quatrains, etc., accompanied by facial and body gestures and mime. Reading, spelling, recognition and utterance of words sharing a common pattern, rhyming words and final phonemes. Understanding messages produced with different accents of the English language. Oral production: basic elements of prosody (pauses, pronunciation, proper intonation...) and non-verbal communication. Construction, communication and valuation of knowledge through the planning and production of oral and multimodal texts to relate events or happenings, invent or modify stories, summarize texts heard, express opinions on nearby topics, respond to questions, etc. Adequacy of expression to the intention, considering the interlocutor and the subject matter. |

| Murcia |

A. Communication block 1st cycle: Initiation to elementary sound and accentual patterns. 2nd cycle: Basic sound, accentual and intonation patterns in common use, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. 3rd cycle: Basic sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. Lexicon and expressions in common use, with careful pronunciation and appropriate rhythm, intonation and accentuation, both in oral interaction and expression and in dramatizations or representations of communicative situations, to understand statements on communication, language, learning and communication and learning tools (metalanguage). Learning situations and complementary information on phonetics and/or sound patterns are not specified. |

| Navarre |

A. Communication block 1st cycle: Introduction to basic sound and accent patterns in common use. 2nd cycle: Basic sound, accentual and intonation patterns of common use, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. 3rd cycle: Basic sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns, and general communicative functions associated with those patterns. The search for the term phonics or phonemes does not yield any data; neither do they exemplify learning situations. |

| Valencia |

A. Communication block Language and use, integrates the linguistic knowledge of the foreign language (phonetics and phonology, spelling, grammar, vocabulary, communicative functions and textual genres). It is essential to know, reflect on and contrast the linguistic and discursive elements between languages (phonetics, grammar, syntax, vocabulary or textual typology), as well as the extra-linguistic ones (body language, visual signs, pauses, rhythm and intonation), for the understanding and subsequent reformulation of the message. In relation to sound, accent and intonation patterns: 1st cycle: Introduction to elementary sound and accent patterns. 2nd cycle: Language and Use, in relation to Communicative Functions. Basic sound, accentual and intonation patterns in common use and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. 3rd cycle: Basic sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns and general communicative functions associated with these patterns, alongside spelling conventions. No specific discourse structures or more specific examples of pronunciation-related issues. |

Appendix C

Appendix D

| (Sub)Codes | Number of quotations |

| ● 1. Curriculum Design and Development | 278 |

| ● 1.1. Contents of English Curriculum | 109 |

| ● 1.1.1. Pronunciation | 101 |

| ● 1.1.2. Phonetics | 82 |

| ● 1.1.3. Grammar | 20 |

| ● 1.1.4. Student difficulties | 15 |

| ● 1.1.5. Student attitudes | 35 |

| ● 1.1.6. Contents | 2 |

| ● 1.1.7. Basic knowledge | 2 |

| ● 1.1.8. Editorial proposals | 18 |

| ● 1.1.9. Educational projects | 12 |

| ● 1.1.10. Area structure | 15 |

| ● 1.1.11.Objectives | 10 |

| ● 1.1.15.Games | 5 |

| ● 1.1.16. Activities | 39 |

| ● 1.1.22. Interdisciplinary Projects | 6 |

| ● 1.1.22. Learning situations | 5 |

| ● 1.2. Methodological Principles | 69 |

| ● 1.2.1. Platforms | 10 |

| ● 1.2.2. Applications | 38 |

| ● 1.2.2. Methods | 19 |

| ● 1.2.9. Difficulties | 30 |

| ● 1.2.11.Jolly Phonics | 8 |

| ● 1.3. LOMLOE Curricular Proposals | 52 |

| ● 1.3.1. Curricular Structure | 52 |

| ● 1.3.2. Center documents | 33 |

| ● 1.3.3. Reforms | 6 |

| ● 1.3.4. UDL (Universal Design for Learning) | 3 |

| ● 1.3.5. Digitalization (ICT) | 20 |

| ● 1.3.7. Operational descriptors | 3 |

| ● 1.3.8. Key competences | 4 |

| ● 1.3.9. Specific competences | 1 |

| ● 1.3.10. Evaluation criteria | 25 |

| ● 1.3.11. Basic Knowledge | 1 |

| ● 1.3.12. Contents | 1 |

| ● 1.3.14. Areas of learning | 4 |

| ● 1.3.16. Educational intentions | 1 |

| ● 1.4. Evaluation | 42 |

| ● 1.4.1. Resources | 1 |

| ● 1.4.2. Competence-based approach | 11 |

| ● 1.4.4. Tools | 8 |

| ● 1.4.5. Headings | 4 |

| ● 1.4.6. Indicators of achievement | 2 |

| ● 1.4.10. SELFIE | 1 |

| ● 1.4.13. Role of students | 28 |

| ● 1.4.14. Teacher training | 7 |

| ● 1.4.16. Applications | 1 |

| ● 1.5. Spaces | 22 |

| ● 1.5.1. Autonomous Communities | 8 |

| ● 1.5.3. Classroom | 13 |

| ● 1.5.4. Family (household) context | 6 |

| ● 1.5.5. Ratio of students | 15 |

| ● 2.6. Timing | 35 |

| ● 1.6.1. Timetables | 18 |

| ● 1.6.3. Teaching load | 28 |

| ● 1.7. Teaching Resources and Materials | 107 |

| ● 1.7.1. Textbooks | 50 |

| ● 1.7.4. Tablets | 2 |

| ● 1.7.8. Digital platforms | 1 |

| ● 1.7.9. Publishers | 31 |

| ● 1.7.10. Applications | 1 |

| ● 1.7.11. Needs | 4 |

| ● 1.7.14. PROENS | 2 |

| ● 1.7.15. EDIXGAL | 5 |

| ● 1.7.16. Snappet (Pupil app) | 5 |

| ● 1.7.17.Use | 4 |

| ● 1.7.22. Support | 4 |

| ● 1.7.23. Educational stages | 32 |

| ● 1.7.25. Music | 4 |

| ● 1.7.26.Videos | 2 |

| ● 1.7.27. Obstacles | 8 |

| ● 1.7.28. Accessibility | 1 |

| ● 1.7.29. Constraints | 40 |

| ● 1.7.30 Licences | 6 |

| ● 1.8. Economic Resources | 1 |

| ● 1.9. Technologies and Digitalization | 75 |

| ● 1.9.1. Programs | 15 |

| ● 1.9.2. Digital Books | 10 |

| ● 1.9.11. Digital games | 1 |

| ● 1.10. Educational Cycles and Levels | 24 |

| ● 1.10.1. Courses | 12 |

| ● 1.10.2. Stages | 15 |

| ● 1.10.6. Adaptations | 2 |

| ● 1.10.7. Curricular Flexibility | 3 |

| ● 1.11. Support and attention to diversity | 9 |

| ● 1.11.1. Curricular Adaptations | 10 |

| ● 1.11.3. Educational support | 9 |

| ● 1.11.4. Curricular measures | 5 |

| ● 2. Teacher Professional Development (TPD) | 100 |

| ● 2.1. Teaching staff | 31 |

| ● 2.1.3. Teaching coordination | 11 |

| ● 2.1.4. Needs | 8 |

| ● 2.1.6. Technical role | 4 |

| ● 2.1.8. Curricular pressure | 1 |

| ● 2.1.9. Teacher unrest | 41 |

| ● 2.1.10. Teaching load | 4 |

| ● 2.1.11. Teaching Autonomy | 25 |

| ● 2.2. Centers | 60 |

| ● 2.3. Administration | 45 |

| ● 2.3.2. Control | 42 |

| ● 2.3.3. Bureaucracy | 40 |

| ● 2.3.4. Deadlines | 8 |

| ● 2.3.9. Inspection | 8 |

| ● 2.4. Educational Innovation Processes | 23 |

| ● 2.4.3. Attitudes | 2 |

| ● 2.5. Lifelong learning | 6 |

| ● 1.6. Theory-Practice Relationship | 8 |

| ● 2.6.1. Knowledge production | 2 |

| ● 2.6.2. Teaching role | 55 |

Appendix E

|

CODES |

FG01 | FG02 | FG03 | |

| 1 | Curriculum Development and Design (CDD) | |||

|

1.1.1. 1.1.2. |

Importance of EFL pronunciation Importance of EFL phonetics |

|||

| English pronunciation is very important, and it should be worked on from an early age. The younger learners are, the less embarrassing it is for them to deal with pronunciation issues and the more plastic their brains are to internalize the sounds and prosody of English. Pronunciation contents can be gradually introduced through games, songs, drills, jolly phonics cards or the materials provided by publishing houses across the cycles, the third cycle focusing on phonetic symbols and prosody (intonation and rhythm). |

We attach a lot of importance to English pronunciation. We think students must learn to pronounce well. However, if a child answers in English, we let him/her speak, despite his/her mispronunciations. What you value is his/her willingness to communicate. The basic difficulty is that Spanish has 24 phonemes while English has 44. First, it is essential to understand the language, and then to be able to speak it. It is very important to work on communicative skills, as well as on language exposure for children to become more self-confident in English. |

EFL pronunciation is very important, to be able to pronounce the sounds of the language in an understandable way. We know that it is very difficult for students to be able to recognize all the sounds of English words, especially vowels since there are more in English than in Spanish. These are aspects that are not included in EFL primary school textbooks. We work on them ourselves, giving elementary instructions (e.g. position of the tongue, silent letters, phonological awareness of differences). In first grade, students must know the letters and they must learn to read, listen and repeat. |

||

| 1.2. | Methodologies: Pronunciation models | |||

| We use British English as the accent of reference, which is the “poshest”. In the third cycle, I work with Word reference to see the differences between British English, an American accent, as well as other varieties such as Scottish English, for example. |

We prioritize British English as practically all the materials we use target this variety. However, as we favor the communicative approach, listening activities do not focus on just one accent, but often present other models such as American English or speakers of other languages speaking in English in real life situations. We give the English and the American version of some words. It would also be interesting to expose children to other pronunciation models (Scottish English, Irish English, etc.) to have a taste of how real people talk. |

Students are used to studying and listening to British English. This is their reference pronunciation model that conditions their EFL pronunciation learning. Although it is difficult for them, they perceive differences between British English and American English in song lyrics, singers, and music groups. |

||

| 1.2. | Methodologies: Approaches to teach EFL pronunciation | |||

| Instructors know the Jolly Phonics method. “Of course” — they say — “English sounds are divided into 7 groups using a very structured methodology that works very well. But it is better to work on it from an early age.” They also affirm that they use IPA in the third cycle. |

The instructors know what the Jolly Phonics method and use it in class. They say that it is employed in UK to teach reading and writing. We also use explain the differences between right and wrong pronunciations as an eye-opener technique. | Neither of the teachers is familiar with the Jolly Phonics method. However, both emphasize the importance of noting the lack of correspondence between sounds and spelling/letters in English, giving the example of word-final <-r>, because students tend to pronounce them. |

||

| 1.7. | Resources and Didactic Materials | |||

| We use the textbook and accompanying activity book, as well as complementary materials. Instructors claim to be somewhat “constricted” by the contents of textbooks, and one observes an involution in the case of EFL phonetics and pronunciation activities: “I remember materials from years ago that specifically worked on phonetic issues much more explicitly perhaps by saying something like “We are going to work on this phonetic symbol, this sound”, presenting the phonetic symbols as well as sounds, and comparing them”. |

Production logs, audiovisual materials such as TV (series, movies, drawings...), digital whiteboard, audio (songs...) and multimedia materials (virtual notebook to carry out interactive activities inside the Chromebook). |

The basic material is the textbook that covers a bit of everything (phonetics, oral activities, viewing, listening, grammar). One instructor thinks that it is very well structured, using additional materials such as videos, songs, and the like, to connect what they are studying with students’ interests. The other teacher also uses the textbook, but to a certain extent, as didactic unit material, but does not wish to be “enslaved” to the book contents. |

||

| 1.7. | Resources and Didactic Materials | |||

| All the teachers agree that music (songs that children like) is very important because it brings many EFL dimensions together (vocabulary, pronunciation, phonetics, rhythm and so on). Small fragments of original English versions of movies/series (with Spanish subtitles) are also found very useful. In 4th, 5th and 6th grades, instructors introduce phonetic concepts and symbols to represent sounds, which are gradually worked on, raising children’s awareness of these aspects in playful way. Complementary materials are also used to contrasting EFL and Spanish sounds in the classroom. |

Basically, we work on oral competence through songs, since, at this age children have a great capacity for retention, and they can reproduce words and sounds quite well. In 1st and 2nd grade, the methodology is very active. We believe it is essential that they lose their fear to speak. In the 2nd cycle, we use Jolly Phonics to differentiate similar sounds, as well as error analysis to distinguish what is right and wrong. In 3rd cycle, 5th and 6th grades, pronunciation and oral skills are enhanced through oral presentations. Specific pronunciation-related activities focus on sound-spelling correspondences distinguishing between grapheme and phoneme, targeting correct pronunciations. |

Practicing communicative routines, the days of the week, the months, the numbers, and so on. Additionally, both instructors work with music (songs), videos (series) for the same purpose. When students are older, the watch short series in the original English version with Spanish subtitles, as a sort of “immersion” activity. |

||

|

1.7.9. 1.7.1. |

Publishers Textbooks and selection criteria |

|||

| The textbooks we use are Oxford and Macmillan. |

The textbooks we use in the three cycles are from British publishing houses, mostly Macmillan. However, we use them as a support, because now we prefer to follow our own methodology and portfolio in the center. | In Galicia most primary schools work with Oxford and/or Macmillan. All educational centers, regardless of their curriculum, work with the same textbooks. We always work with Oxford because we consider that it is a serious publisher. I personally like Macmillan a little more for the little ones, and Oxford for the slightly older ones. We decided to stick to Oxford in the three cycles for the sake of coherence. |

||

| 1.6. | Timing | |||

| Within the timeframe we have, three hours a week, there is not enough time to work on the competencies associated with EFL learning. Time is always a problem. Ideally, the system should be self-managed. The deadlines and excessive bureaucratization required for the development of teaching programs predetermined by curricular requirements in institutional educational platforms conditions and usually turn in a work overload, often to the detriment of greater attention to students. |

We devote eight hours a week to EFL learning, which are distributed in projects (each one lasting three weeks), in addition to seminars and playful interdisciplinary workshops (exhibition or oral presentation). Children have one additional session per week with a conversation assistant. |

We teach EFL three hours a week. In the first courses, we make a very detailed timetable/programming, specifying how many days we dedicate to each content and how we do it. All the sessions are 60 minutes long, except the ones after recess, which are 45 minutes (until 2:00 pm). |

||

| 1.4. | Assessment | |||

| In a language classroom, we cannot be with 25 students, when the curriculum talks about making small groups to prioritize oral skills. We cannot assess them individually regarding their EFL pronunciation skills. To do this and to prioritize oral skills, it would be essential to have smaller groups as established in the primary school national curriculum. |

We give new students a placement test to find out their written and oral competencies. Students’ oral presentations are recorded to observe their pronunciation, correct mistakes and discuss issues, and sometimes checklists are made to register each student’s pronunciation and expression issues. EFL orality is evaluated using rubrics (for fluency, pronunciation, and vocabulary) on a one to four scale. Each student has three rubrics corresponding to initial, mid-term and final evaluation. |

Communicative competence is what we care about. We want students to listen, understand, speak, and write. So, we continually assess students’ performance in these competencies and skills. |

||

| 2 | Teacher Professional Development (TPD) | |||

|

2.1.9. 2.2. 2.4. 2.3.3. |

Teacher Unrest Centers Educational Innovation Bureaucracy |

|||

| Primary school teachers are capable of instructing EFL pronunciation, but this requires several prerequisites: coordination, adaptation of the curriculum by the administration, EFL (pronunciation) specialization courses, group work and group dynamics, mastering innovative technologies, provision of adequate equipment, and adjustment of teachers’ schedules to enable them to retrain. | Absolutely not. Primary school instructors would need additional training to work on the didactics of language teaching (e.g. phonological skills, among others). | Primary school instructors do not receive enough training in EFL pronunciation, or in any other competencies related to language learning. Teaching training courses on these topics are a necessity. Instead, instructors receive more general pedagogical training, which is often outdated. Furthermore, ICT resources are not always helpful either or make matters more complicated. Educational innovation takes a back seat because of the many obstacles instructors must face, ranging from limited time schedules, a high ratio of students per group, bureaucratic obligations to lack of adequate or necessary means and resources. |

||

|

2.1.11. 2.3. 2.3.2. 2.3.3. |

Teacher autonomy Administration Control Bureaucracy |

|||

| Sometimes it is complicated, because the management plan plays with tools that are also very ... bureaucracy, bureaucracy eh... it is very easy to put it on the table and it is very easy to demand deadlines, and those deadlines condition people, in general we are afraid of deadlines. |

Programming always had to be done, the current one, or the teaching one, or whatever you want to call it, it always had to be done… they don’t ask you for it. They also never asked you for it, unless an inspector came. The law is confusing. The way it’s written, and you have to read it several times because it is very technical, it’s very technical discourse. We thought the curriculum was going to help us more. The bureaucratic load we have at the moment is huge. And of course, that does not translate into our timetable, our timetable says 25 hours of classes, OK, you can’t tell anyone that 25 hours of classes is a huge effort, but we need to adapt that timetable because we can’t, if I want to join training. |

|||

| 1 | The term pronunciation may be defined in a narrow sense concerning speech production and reception skills (Dalton & Seidlhofer, 1994), or it may be used as a cover term for both phonetics, or the study of human speech sounds, and phonology, or how sounds function in a systematic way (Gimson 1989; Cruttenden, 2014). Following the latter approach, in this study EFL pronunciation encompasses phonetic and phonological knowledge and skills, which are linguistically-oriented, as well as other competencies and methodologies that are necessary for developing expression and communication. |

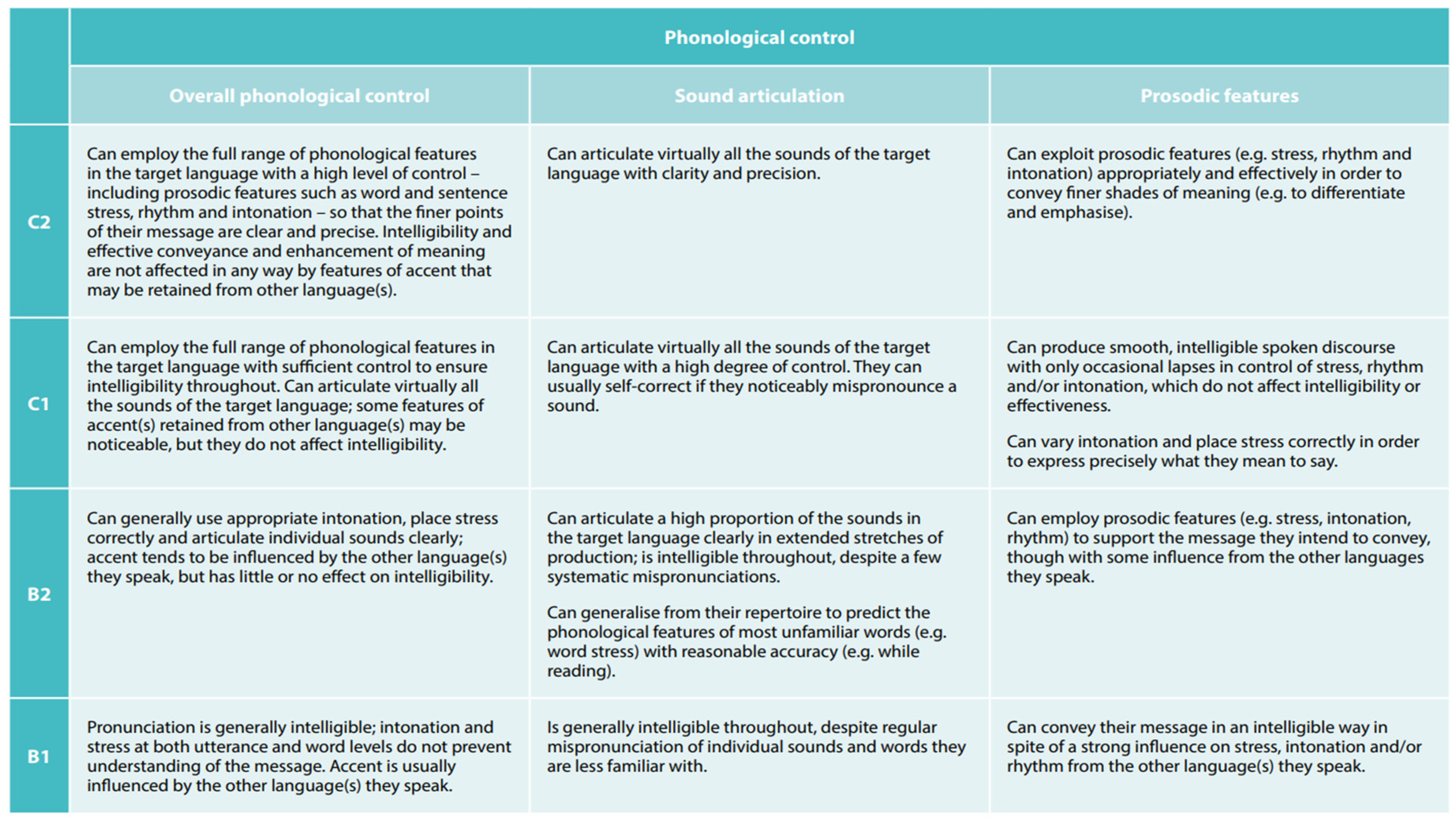

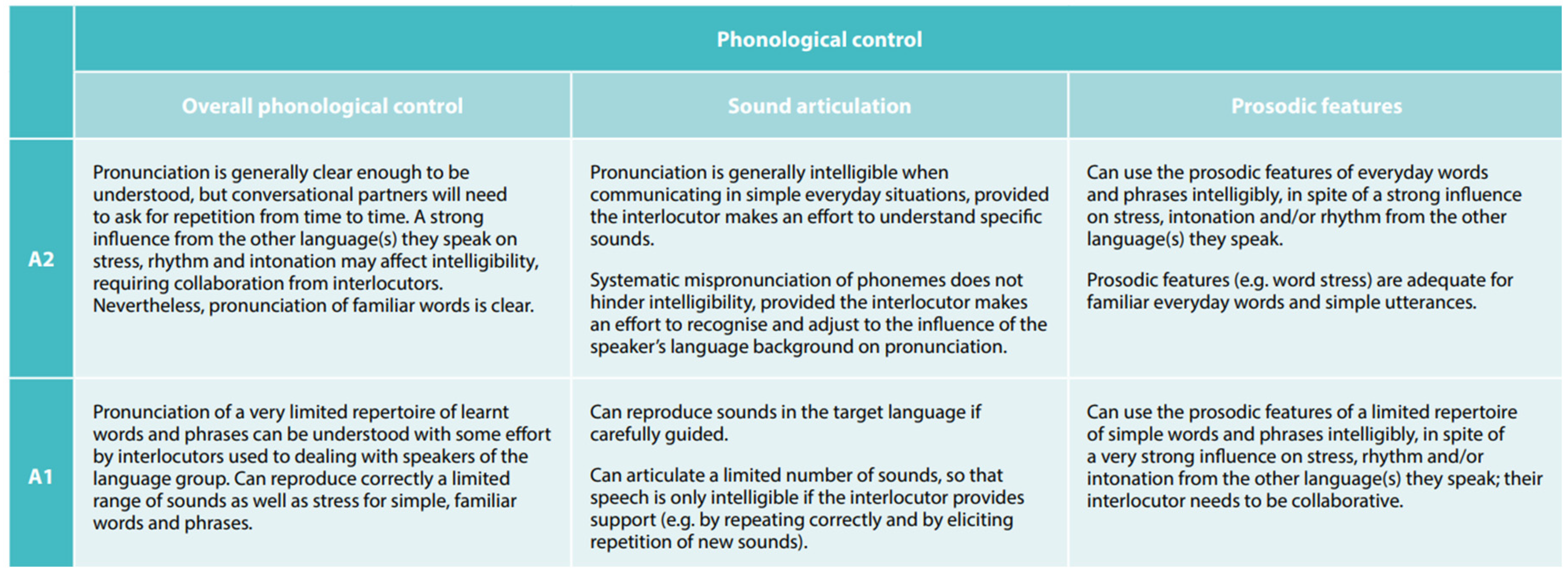

| 2 | ACTFL (American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages) Standards for Foreign Language Learning in the 21st Century (National Standards Collaborative Board, 2015) offer only brief and vague commentaries on phonological learning goals (O’Brien, 2004). The European Language Portfolio (ELP), on the other hand, is linked to the CEFR but focuses on the development of learner autonomy and competence, as well as on plurilingualism and intercultural awareness, whether gained inside or outside formal education. It also scaffolds spoken interaction and spoken production into six levels, but it makes no explicit reference to pronunciation issues. |

| 3 | We ensured that the study adhered to the ethical principles proposed by the Research Ethics Committee at the University of Santiago de Compostela and respected the privacy and confidentiality of the participants involved. |

References

- Anderson-Hsieh, J.; Johnson, R.; Koehler, K. The relationship between native speaker judgments of nonnative pronunciation and deviance in segmentals, prosody, and syllable structure. Language Learning 1992, 42(4), 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, R. Teaching speaking: an exploratory study in two academic contexts. Porta Linguarum 2014, 22, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsson, N.; Hyltenstam, K. Age of onset and nativelikeness in L2: Listener perception versus linguistic scrutiny. Language Learning 2009, 59, 249–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azpilicueta-Martínez, R.; Lázaro-Ibarrola, A. Intensity of CLIL exposure and L2 motivation in primary school: Evidence from Spanish EFL learners in non-CLIL, low-CLIL and high-CLIL programmes. IRAL: International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Yuan, R. EFL teachers’ beliefs and practices about pronunciation teaching. ELT Journal 2019, 73(2), 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.; Burri, M. Feedback on second language pronunciation: A case study of EAP teachers’ beliefs and practices. Australian Journal of Teacher Education 2016, 41(6), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. A parents’ and teachers’ guide to bilingualism, 4th ed.; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bakla, A.; Demirezen, M. An overview of the ins and outs of L2 pronunciation: A clash of methodologies. Journal of Mother Tongue Education 2018, 6(2), 477–497. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, S. J. The teachers’ soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy 2003a, 18(2), 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S. J. Professionalism, Managerialism and Performativity. (Keynote Address, Professional Development and Educational Change, a Conference organized by The Danish University of Education, 14 May 2003.). 2003b. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, S. J. Performativity, commodification and commitment: An I-Spy guide to the neoliberal university. British Journal of Educational Studies 2012, 60(1), 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbero, J. La enseñanza de la lengua inglesa en el sistema educativo español: De la legislación al aula como entidad social (1970-2000). Cabás 2012, 8, 72–96. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, J. A autonomia das escolas: Retórica, instrumento e modo de regulação da acção política. In A Autonomia das Escolas; Moreira, A., Ed.; Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian: Lisbon, 2006; pp. 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolí Rigol, M. La pronunciación en las clases de lenguas extranjeras. Phonica 2005, 1, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bayyurt, Y.; Sifakis, N. C. ELF-aware in-service teacher education: A transformative perspective. In International perspectives on teaching English as a lingua franca; Bowles, H., Cogo, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan; Basingstoke, 2015b; pp. 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Bent, T.; Bradlow, A.R. The interlanguage speech intelligibility benefit. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 2003, 114(3), 1600–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, C. T.; Tyler, M. D. Nonnative and second-language speech perception: Commonalities and complementarities. In Language experience in second speech learning: In honor of James Emil Flege; Munro, M. J., Bohn, O.-S., Eds.; John Benjamins: Amsterdam and Philadelphia, 2007; pp. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss, H.; Abel, J.; Gick, B. Computer-assisted visual articulation feedback in L2 pronunciation instruction: A review. Journal of Second Language Pronunciation 2018, 4(1), 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOE. Organic Law 3/2020, of 29 December, which amends Organic Law 2/2006, of 3 May, on Education. Official State Journal 2022a, 340, 122868–122953. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2020/12/29/3.

- BOE. Decreto Enseñanzas Mínimas y Currículo Primaria. Order EFP/678/2022, of 15 July, which establishes the curriculum and regulates the organisation of Primary Education in the area of management of the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training. Official State Journal 2022b, 174, 103615–103772. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2022-12066.

- Bolívar, A. El discurso de las competencias en España: Educación básica y educación superior. Revista de docencia universitaria 2008, 6(2), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolívar, A. Liderazgo para el aprendizaje. En Organización y gestión educativa: Revista del Fórum Europeo de Administradores de la Educación 2010, 18(1), 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar, A. Un currículum inclusivo en una escuela que asegure el éxito para todos. Revista E-currículum 2019, 17(3), 827–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, S. The impact of in-service teacher education on language teachers’ beliefs. System 2011, 39, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil, D.; Coulthard, M.; Johns, C. Discourse intonation and language teaching; Longman: London, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-Alastuey, M. C.; Gómez-Lacabex, E. Technology and pronunciation. In The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition and technology; Routledge: London, 2022; pp. 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo Benzies, Y. J. The teaching and learning of English pronunciation in Spain. An analysis and appraisal of students’ and teachers’ views and teaching materials. Unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Santiago de Compostela, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cantarutti, M. Pronunciation and e-portfolios: Developing self-regulatory skills and self-esteem. In IATEFL 2014 Harrogate Conference Selections; Pattison, T., Ed.; IATEFL, 2015; pp. 136–138. [Google Scholar]

- Carlet, A.; Cebrian, J. Assessing the effect of perceptual training on L2 vowel identification, generalization and long-term effects. In A sound approach to language matters; Nyvad, A. M., Hejna, M., Hojen, A., Jespersen, A. B., Sorensen, M. H., Eds.; Aarhus University Press; Aarhus, 2019; pp. 91–119. [Google Scholar]

- Carrie, E. British is professional, American is urban: attitudes towards English reference accents in Spain. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 2016, 27(2), 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo Rodríguez, C.; Torrado Cespón, M.; Lago Ferreiro, A. The ideal English pronunciation resource: non-native teachers’ beliefs. Opción 2023, 39, 131–154. [Google Scholar]

- Celce-Murcia, M. Teaching Pronunciation; Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Celce-Murcia, M.; Brinton, D. M.; Goodwin, J. M. Teaching pronunciation: A reference for teachers of English to speakers of other languages; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Celce-Murcia, M.; Brinton, D. M.; Goodwin, J. M. Teaching pronunciation hardback with audio CDs (2): A course book and reference guide; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cenoz, J.; Garcia-Lecumberri, M. L. The acquisition of English pronunciation: Learners’ views. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 1999, 9, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapelle, C.; Jamieson, J. Tips for teaching with CALL: Practical approaches to computer-assisted language learning; Pearson-Longman: White-Plains, NY, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coll, C.; Martín, E. Las competencias específicas de área y materia. Cuadernos de Pedagogía 2022, 537, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR). Companion Volume with New Descriptors. 2018. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages.

- Council of Europe. Council Regulation (EU) 2020/1998 of 7 December 2020 concerning restrictive measures against serious violations and abuses of human rights. 2020a. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2020/1998/oj.

- Council of Europe. Council conclusions on European teachers and trainers for the future (2020/C 193/04). 2020b. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020XG0609(02).

- Couper, G. Teacher cognition of pronunciation teaching: Teachers’ concerns and issues. Tesol Quarterly 2017, 51(4), 820–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano, CV. Designing and conducting mixed methods research, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cruttenden, A. Gimson’s pronunciation of English; Routledge: London, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy, A. 2018. Available online: https://www.euronews.com/2018/11/03/which-eu-countries-are-the-best-and-worst-at-speaking-english.

- Dalton, C.; Seidlhofer, B. Pronunciation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Darcy, I.; Ewert, D.; Lidster, R. Bringing pronunciation instruction back into the classroom: An ESL teachers’ pronunciation “toolbox”. In Proceedings of the 3rd Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference; Levis, J., LeVelle, K., Eds.; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, 2012; pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, Y.; Kartal, G. Mapping research on L2 pronunciation: A bibliometric analysis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 2022, 44(5), 1211–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirezen, M. The recognition and the production of question forms of English intonation by Turkish first year students. Worldwide Forum on Education and Culture-Putting Theory intoPractice: Teaching for the Next Century, Rome, Italy, 4–5 December; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Derwing, T. M. Utopian goals for pronunciation teaching. In Proceedings of the 1st Pronunciation in the Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference; Levis, J., Velle, L., Eds.; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, 2010; pp. 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Derwing, T. M.; Munro, M. J. Putting accent in its place: Rethinking obstacles to communication. Language teaching 2009, 42(4), 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwing, T. M.; Munro, M. J. Pronunciation fundamentals: Evidence-based perspectives for L2 teaching and research; John Benjamins: Amsterdam & Philadelphia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Derwing, T. M.; Rossiter, M.J. ESL learners’ perceptions of their pronunciation needs and strategies. System 2002, 30(2), 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwing, T.; Munro, M. J. Second language accent and pronunciation teaching: A research-based approach. TESOL Quarterly 2005, 39(3), 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, M.; Patsko, L. ELF and teacher education. In The Routledge Handbook of English as a Lingua Franca; Jenkins, J., Baker, W., Dewey, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, 2018; pp. 441–455. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez Baguer, I. An approach to the teaching of pronunciation in primary education in Spain. BA dissertation, University of Zaragoza, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Lage, J. M.; Gómez González, M. Á.; Santos Díaz, I. C. Teaching and learning English phonetics/pronunciation in digital and other learning environments: Challenges and perceptions of Spanish instructors and students. In Current Trends on Digital Technologies and Gaming for Language Teaching and Linguistics; Santos Díaz, et al., Eds.; Peter Lang: Bern, 2023a; pp. 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Dörnyei, Z. The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition; Lawrence Erlbaum: New York, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Engwall, O.; Bälter, O. Pronunciation feedback from real and virtual language teachers. Journal of Computer Assisted Language Learning 2007, 20(3), 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EURYDICE. Teachers in Europe: careers, development and well-being. [Online]. 2021. Available online: https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/publications/.

- Fernández González, J. Reflections on foreign accent. In Issues in second language acquisition and learning; Fernández González, J., de Santiago-Guervós, J., Eds.; Universitat de València: Valencia, 1988; pp. 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Flege, J. E.; Bohn, O. The Revised Speech Learning Model (SLM-r) applied. In Second language speech learning: Theoretical and empirical progress; Wayland, R., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2021; pp. 84–118. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Mora, M.C.; Fernández-Corbacho, A. Procesamiento fonológico y aprendizaje de la lectura en lengua extranjera. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada/Spanish Journal of Applied Linguistics (RESLA/SJAL) 2017, 30(1), 166–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foote, J. A.; Trofimovich, P.; Collins, L.; Soler Urzua, F. Pronunciation teaching practices in communicative second language classes. The Language Learning Journal 2016, 44(2), 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouz-González, J.; Mompean, J. A. Exploring the potential of phonetic symbols and keywords as labels for perceptual training. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 2021, 43, 297–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga-Varela, F.; Ceinos-Sanz, C.; García-Murias, R.; Ramos-Trasar, I. Currículos autonómicos LOMLOE de Educación Primaria y autonomía del profesorado: Un análisis comparado. Revista de Investigación en Educación 2024, 22(3), 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullan, M.; Quinn, J. Coherence: The right drivers in action for schools, districts, and systems; Corwin Press: LACE, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo del Puerto, F. La adquisición de la pronunciación del inglés como tercera lengua. Unpublished Ph D dissertation, Universidad del País Vasco, Thousand Oaks, CA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo del Puerto, F.; García Lecumberri, M. L.; Cenoz Iragui, J. Degree of foreign accent and age of onset in formal school instruction PLACE/PUBLISHER? In Proceedings of the Phonetics Teaching and Learning Conference; 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo del Puerto, F.; García Lecumberri, M. L.; Gómez Lacabex, E. The assessment of foreign accent and its communicative effects by native judges vs. experienced non-native judges. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 2015, 25(2), 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo del Puerto, F.; Lecumberri, M. L. G.; Cenoz, J. Age and native language influence on the perception of English vowels. In English with a Latin Beat; John Benjamins: Amsterdam & Philadelphia, 2005; pp. 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L. Pronunciation difficulties analysis: a case study using native language linguistic background to understand a Chinese English learner’s pronunciation problems. Celea Journal 2005, 28(2), 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- García Lecumberri, M.L.; Gallardo del Puerto, F. English FL sounds in school learners of different ages. In Age and the acquisition of English as a foreign language; García Mayo, M.P., García Lecumberri, M.L., Eds.; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, 2003; pp. 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- García Mayo, M. P. Learning foreign languages in primary school. Research insights; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gass, S. M.; Selinker, L. Second language acquisition: An introductory course; Lawrence Erlbaum: New York, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou, G. P. EFL teachers’ cognitions about pronunciation in Cyprus. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 2018, 40(6), 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilakjani, A.P.; Sabouri, N.B. Why is English pronunciation ignored by EFL teachers in their classes? International Journal of English Linguistics 2016, 6(6), 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimson, A. C. An introduction to the pronunciation of English, 4th ed.; Edward Arnold: London, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez González, M. Á.; Sánchez Roura, M. T. English Pronunciation for Speakers of Spanish. In From Theory to Practice; Mouton de Gruyter: Boston/Berlin/Beijing, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-González, M. Á.; Sánchez Roura, M. T.; Torrado Cespón. English Pronunciation for Speakers of Spanish. A Practical Course Toolkit; Santiago de Compostela University Press: Santiago de Compostela, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez González, M. Á.; Lago Ferreiro, A.; Fragueiro Agrelo, A. Using a Serious Game for English Phonetics and Pronunciation Training: Foundations and Dynamics. In Current Trends on Digital Technologies and Gaming for Language Teaching and Linguistics; Santos Díaz, et al., Eds.; Peter Lang: Bern, 2023b; pp. 109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-González, M. Á.; Lago Ferreiro, A. Computer-Assisted Pronunciation Training (CAPT): An empirical evaluation of EPSS Multimedia Lab. Language Learning & Technology 2024a, 28(1), 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Lacabex, E.; García Lecumberri, M.L.; Cooke, M. Training and generalization effects of English vowel reduction for Spanish listeners. In Recent research in second language phonetics/ Phonology: perception and production; Watkins, M. A., et al., Eds.; CSP: Newcastle upon Tyne, 2009; pp. 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Lacabex, E.; Gallardo del Puerto, F. Two phonetic-training procedures for young learners: Investigating instructional effects on perceptual awareness. Canadian Modern Language Review 2014, 70(4), 500–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Lacabex, E.; Gallardo del Puerto, F. Explicit phonetic instruction vs. implicit attention to native exposure: Phonological awareness of English schwa in CLIL. IRAL 2020, 58(4), 419–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Lacabex, E.; Gallardo-del-Puerto, F.; Gong, J. Perception and production training effects on production of English lexical schwa by young Spanish learners. Journal of Second Language Pronunciation 2022, 8(2), 196–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, A. J.; Russo, F. A.; Sullivan, J. The efficacy of singing in foreign language learning. Psychology of Music 2015, 43, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelsman, J.; Ebert-May, D.; Beichner, R.; Bruns, P.; Chang, A.; DeHaan, R.; et al. Scientific teaching. Science 2004, 304, 521–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.; Curnick, L.; Frost, D.; Kautzsch, A.; Kirkova-Naskova, A.; Levey, D.; Waniek-Klimczak, E. The English pronunciation teaching in Europe survey: Factors inside and outside the classroom. In Investigating English pronunciation: Trends and directions; Mompean, J.A., Fouz-González, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, 2015; pp. 260–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.; Frost, D.; Tergujeff, E.; Kautszch, A.; Murphy, D.; Kirlova Naskova, A.; Cunick, L. English pronunciation teaching in Europe survey: Selected results. Research in language 2012, 2012, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, F.; Sloep, P.; Kreijs, K. Teacher professional development in the contexts of teaching English pronunciation. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2017, 14(23). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiep, P. H. Teacher development: A real need for English departments in Vietnam. Forum 2001, 39(4), n4. Available online: http://exchanges.state.gov/forum.

- Hişmanoğlu, M. The [ɔ:] and [oʊ] contrast as a fossilized pronunciation error of Turkish learners of English and solutions to the problem. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies 2007, 3(1), 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs, T. Shifting sands in second language pronunciation teaching and assessment research and practice. Language Assessment Quarterly 2018, 15(3), 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, F.; Koffi, E.; Uchikawa, M. English education in Japan from the perspective of a Japanese student. Linguistic Portfolios 2020, 9(8), 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, J. The phonology of English as an international language. New models, new norms, new goals; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, J. English as a Lingua Franca: Attitude and identity; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, J. Repositioning English and multilingualism in English as a Lingua Franca. Englishes in Practice 2015, 2(3), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L. G. Twenty-five centuries of language teaching; Newbury House: PLACE, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Kenworthy, J. Teaching English pronunciation; Longman: PLACE, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl, P. K. The role of experience in early language development: Linguistic experience alters the perception and production of speech. In The role of early experience in infant development; Johnson & Johnson Pediatric Institute, 1999; pp. 101–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaravadivelu, B. The decolonial option in English teaching: Can the subaltern act? TESOL Quarterly 2016, 50(1), 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, D.; Lara, L. Podcasting: An effective tool for honing language students’ pronunciation? Learning & Technology 2009, 13(3), 66–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lázaro-Ibarrola, A. Enseñanza de la lectura a través de phonics en el aula de Lengua Extranjera de Educación Primaria; University of Granada University Press: Universidad de Granada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lázaro-Ibarrola, A. English phonics for Spanish children: adapting to new English as a Foreign Language classrooms. In Researching literacy in a foreign language among primary school learners/Forschung zum Schrifterwerb in der Fremdsprache bei Grundschülern; Diehr, B., Rymarczyk, J., Eds.; Peter Lang: Berne, 2010; pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Jang, J.; Plonsky, L. The effectiveness of second language pronunciation instruction: A meta-analysis. Applied Linguistics 2015, 36(3), 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, J. Research into practice: How research appears in pronunciation teaching materials. Language Teaching 2016, 49(3), 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levis, J. M. Intelligibility, oral communication, and the teaching of pronunciation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D. Researching NNSs’ views toward intelligibility and identity: Bridging the gap between high moral grounds and down-to-earth concerns. In English as an international language: Perspectives and pedagogical issues; Sharifan, F., Ed.; Multilingual Matters: Clevedon, 2009; pp. 81–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lindade Rodrigues, C. J. A comprehensive analysis on how English Language Teaching coursebooks promote pronunciation in Portuguese public schools; University of Vigo Press; Vigo, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lintunen, P. Pronunciation and phonemic transcription: A study of advanced Finnish learners of English; Anglicana Turkuensia: Turku, 2004; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Lintunen, P.; Mäkilähde, A. Short-and long-term effects of pronunciation teaching: EFL learners’ views. In The pronunciation of English by speakers of other languages; Teoksesssa Volín, J., Skarnitzl, R., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2018; pp. 46–72. [Google Scholar]

- Low, E. L. EIL pronunciation research and practice: Issues, challenges, and future directions. RELC Journal 2021, 52(1), 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludke, K. M.; Ferreira, F.; Overy, K. Singing can facilitate foreign language learning. Memory & cognition 2014, 42, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, S. Pronunciation: views and practices of reluctant teachers. Prospect 2002, 17(3), 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, J.; Łeba, P. L. Cinderella at the crossroads: quo vadis, English pronunciation teaching. Babylonia 2011, 2(11), 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Alonso, D.; Sierra, E.; Blanco, N. Relationships and tensions between the curricular program and the lived curriculum. Narrative research. Teaching and Teacher Education 2021, 105, 103433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A. M. M. Explicit and differentiated phonics instruction as a tool to improve literacy skills for children learning English as a Foreign Language. GIST Education and Learning Research Journal 2011, 5, 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, A. M.; Gallardo, F. Hacia la mejora de la exposición oral en inglés en ámbito universitario. GRETA Journal 2011, 19, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Flor, A.; Usó, E.; Alcón, E.; Usó, E.; Martínez-Flor, A. Towards acquiring communicative competence through speaking. In Current trends in the development and teaching of the four language skills; Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin, 2006; pp. 139–157. [Google Scholar]

- Matera, M. Explore Like a Pirate: Gamification and Game-Inspired Course Design to Engage, Enrich and Elevate Your Learners; Editorial Paperback: San Diego, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Medgyes, P. The non-native teacher, 3rd ed.; Swan Communication: Scotland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum, N. Young learners and the phonemic chart. 19 January 2004. Available online: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/young-learners-phonemic-chart.

- Mitterer, H.; Eger, N.A.; Reinisch, E. My English sounds better than yours. Second-language learners perceive their own accent as better than that of their peers. PLOS One 2020, 15(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanasundaram, K. Curriculum Design and Development. Journal of Applied and Advanced Research 2018, 3 Suppl. 1, S4−S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mompean, J. A. Options and criteria for the choice of an English pronunciation model in Spain. In Linguistic perspectives from the classroom (1043-1059); Oro Cabanas, J. M., Anderson, J., Varela Zapata, J., Eds.; Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mompean, J. A.; Fouz-González, J. Twitter-based EFL pronunciation instruction. Language Learning & Technology 2016, 20(1), 166–190. [Google Scholar]

- Mompean, J. A.; Fouz-Gonzalez, J. Phonetic symbols in contemporary pronunciation instruction. RELC Journal 2021, 52(1), 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mompean, J.A.; Lintunen, P. Phonetic notation in foreign language teaching and learning: Potential advantages and learners’ views. Research in Language 2015, 13, 292–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, J. The pronunciation component in teaching English to speakers of other languages. TESOL Quarterly 1991, 25(3), 481–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, J. El Perfil de Salida y sus consecuencias para el desarrollo del currículo. Cuadernos de Pedagogía 2022, 537, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, M. Conceptualizing pronunciation as part of translingual/transcultural competence: New impulses for SLA research and the L2 classroom. Foreign Language Annals 2013, 46(2), 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz. Exploring young learners’ foreign language learning awareness. Language Awareness 2013, 23(1-2), 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D. An investigation of English pronunciation teaching in Ireland. English Today 2011, 27, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Standards Collaborative Board. World-readiness standards for learning languages, 4th ed; ACTFL: Alexandria, VA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Navas-Brenes, C. A. The language laboratory and the EFL course. Revista Electrónica Actualidades Investigativas en Educación 2006, 6(2), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, Nivela. An approach to the teaching of pronunciation in Primary Education in Spain. BA dissertation, University of Zaragoza, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, T. Writing in a foreign language: Teaching and learning. Language Teaching 2004, 37(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organic Law 3/2020, of 29 December, which amends Organic Law 2/2006, of 3 May, on Education. Official State Journal 2020, 340, 122868–122953. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2020/12/29/3/con.

- Palacios-Hidalgo, F. J.; Gómez-Parra, M. E.; Huertas-Abril, C. A. “Spanish bilingual and language education: A historical view of language policies from EFL to CLIL”. Policy Futures in Education 2022, 20(8), 877–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallarès, M.; Chiva, Ó.; Planella, J.; y López Martín, R. Repensando la educación. Trayectoria y futuro de los sistemas educativos modernos. Perfiles educativos 2019, 41(163), 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcerisa, L.; y Falabella, A. The consolidation of the evaluative state through accountability policies: Trajectory, enactment and tensions in the Chilean education system. Education Policy Analysis Archives 2017, 25, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, M. C. Teaching pronunciation: The state-of-the-art 2021. RELC Journal 2021, 52(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, M.C.; Rogerson-Revell, P. English pronunciation teaching and research: contemporary perspectives; Palgrave Macmillan: PLACE, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Cañado, M. L. CLIL and pedagogical innovation: Fact or fiction? Innovation in language learning and teaching. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 2018, 28, 369–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Cañado, M.L. English and Spanish spelling: Are they really different? The Reading Teacher 2003, 58(6), 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Chowdhury, R. Teaching “English for Life”: Beliefs and attitudes of secondary school English teachers in rural Bangladesh. Bangladesh Education Journal 2018, 17(2), 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rajadurai, J. Forum: Intelligibility studies: A consideration of empirical and ideological issues. World Englishes 2007, 26(1), 101–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallo Fabra, L.; Juan-Garau, M. Assessing FL pronunciation in a semi-immersion setting: The effects of CLIL instruction on Spanish-Catalan learners’ perceived comprehensibility and accentedness. Poznań Studies in Contemporary Linguistics 2011, 47(1), 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.; Michaud, C. An integrated approach to pronunciation: Listening comprehension and intelligibility in theory and practice. In Proceedings of the 2nd Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference; Levis, J., LeVelle, K., Eds.; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, 2011; pp. 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Redón Romero, S. I.; Navarro Pablo, M.; García Jiménez, E. Using phonics to develop the emergent English literacy skills of Spanish learners. Porta Linguarum 2021, 35, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martínez, C. La proletarización del profesorado en la LOMCE y en las nuevas políticas educativas: de actores a culpables. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 2014, 81(28.3), 73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Decree 126/2014, of 28 February, establishing the basic curriculum for Primary Education. Official State Journal 2014, 52, 19349–19420. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2014/02/28/126.

- Royal Decree 157/2022, of 1 March, which establishes the organisation and minimum teachings of Primary Education. Official State Journal 2022, 52, 24386–24504. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2022/03/01/157.

- Saito, K. What characterizes comprehensible and native-like pronunciation among English-as-a-second-language speakers? Meta-analyses of phonological, rater, and instructional factors. Tesol Quarterly 2021, 55(3), 866–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Díaz, I. C.; Gómez González, M. Á.; Díaz Lage, J. Do you speak English? Teachers and students’ perceptions and pronunciation practices. Logos: Revista de Lingüística, Filosofía y Literatura 2024b, 34(1). [Google Scholar]

- Setter, J. Theories and approaches in English pronunciation. In 25 años de lingüística aplicada en España: hitos y retos; Monroy, R., Sanchez, A., Eds.; Editum: PLACE, 2018; pp. 447–457. [Google Scholar]

- Sifakis, N. C.; Sougari, A. M. Pronunciation issues and EIL pedagogy in the periphery: A survey of Greek state school teachers’ beliefs. Tesol Quarterly 2005, 39(3), 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, A. Teaching pronunciation with phonemic symbols. [On-line]. 2002. Available online: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk.

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques; Sage Publications: London, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeting, A. Pronunciation in EFL instruction: A research-based approach. Journal of Academic Language and Learning 2015, 9(1), B1–B3. [Google Scholar]

- Tiana Ferrer, A. Los cambios recientes en la formación inicial del profesorado en España: Una reforma incompleta. Revista española de educación comparada 2013, 22, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trillo Alonso, F.; Fraga Varela, F.; Escudero, J. M.; Moreno, J. M.; Pérez-García, M. P.; Domingo, J. Efectos indeseados de la LOMLOE: de las razonables competencias formativas generales al disparate de una taxonomía de conductas operativas específicas. Un análisis del currículo en Galicia. In Compromiso con la mejora educativa. Homenaje al profesor Antonio Bolívar; University of Granada: University of Granada Press, coords., 2023; pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Uchida, Y.; Sugimoto, J. A survey of Japanese English teachers’ attitudes towards pronunciation teaching and knowledge on phonetics: Confidence and teaching. Proceedings of ISAPh2016: Diversity in Applied Phonetics; 2016; pp. 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Underhill, A. Pronunciation - the poor relation? 2010. Available online: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/pronunciation-poor-relation.

- Valle, J. M. LOMLOE y Competencias Clave: España converge con las tendencias educativas supranacionales. Cuadernos de pedagogía 2022, 537, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ha, X.; Murray, J. C. The impact of a professional development program on EFL teachers’ beliefs about corrective feedback. System 2021, 96, 102405. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, N. Listening: The most difficult skill to teach. Encuentro 2014, 23(1), 167–175. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, D. The social construction of beliefs in the language classroom. Beliefs about SLA: New research approaches 2003, 201–229. [Google Scholar]

|

General provisions |

Sections in the basic knowledge: Communication, Multilingualism and Interculturalism, supported by digital competence with corresponding descriptors based on the language activities and competencies established by the Council of Europe in the CEFR Digital tools reinforce the learning, teaching and assessment of foreign languages and cultures Action-oriented methodological approach Learning through oral and written language use Learning situations involving production and interaction; emphasis on communicative language activities and language proficiency (oral and written): comprehension, production, interaction, mediation, using personal linguistic repertoires across languages, and appreciating and respecting linguistic and cultural diversity Guidelines for the practice of evaluation, both of the learning process and of the teaching process |

| Cycles | Pronunciation in the Communication block and CLC competencies |

| 1st | -Introduction to elementary sound and accent patterns. |

| 2nd | -Basic sound, accentual and intonation patterns in common use, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. |

| 3rd |

-Basic sound, accentual, rhythmic and intonation patterns, and general communicative functions associated with these patterns. -The learning of the foreign language encompasses the acquisition of both the phonetic code and the graphic code of that language. In the first years of this stage, priority will be given to orality while gradually incorporating the written code that allows the comprehensive reading of words and expressions. The acquisition of this code will facilitate the subsequent recognition of written forms and their progressive analysis. -The learning of the written code must be done through the reading and production of texts in real or simulated communicative contexts of personal, family and social life, and related to the needs and interests of the students. This learning will include aspects related to the composition and organization of the different textual manifestations and their use, as well as the different supports and channels that can be used both to access texts and to create them. -Oral production: pronunciation and intonation. Postural attitude. Construction and communication of knowledge through the planning and production of simple oral and multimodal texts. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).