Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

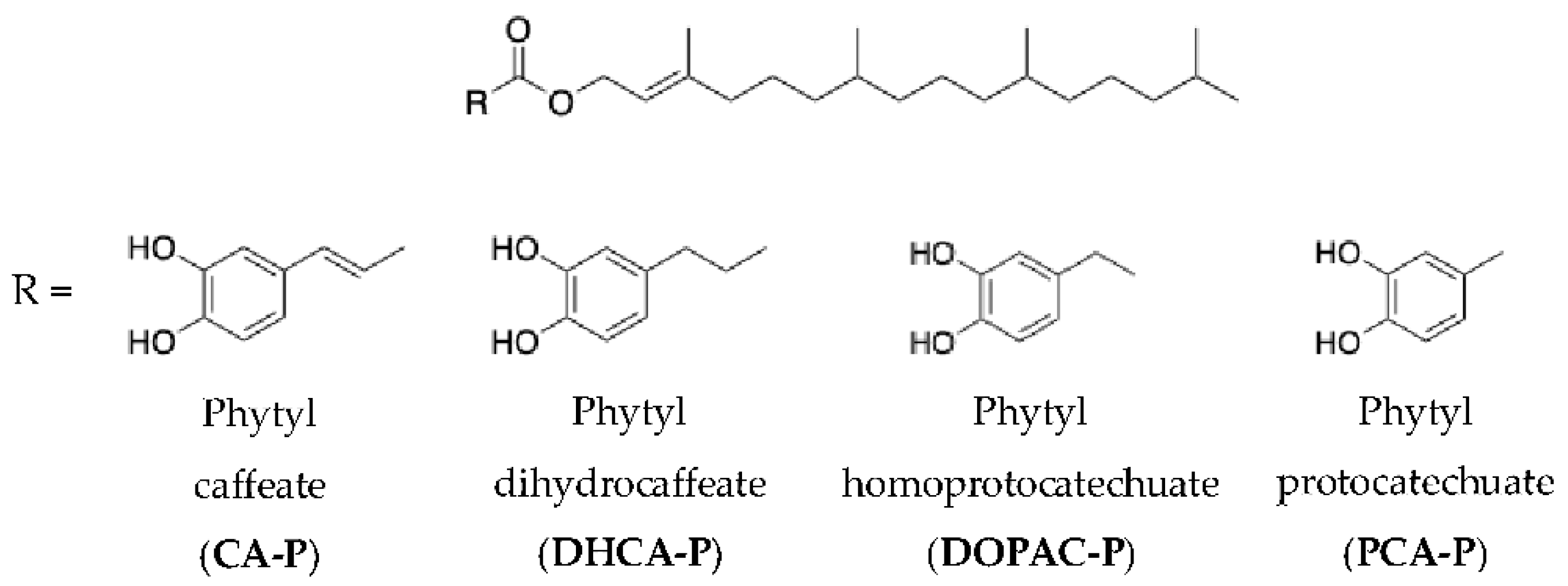

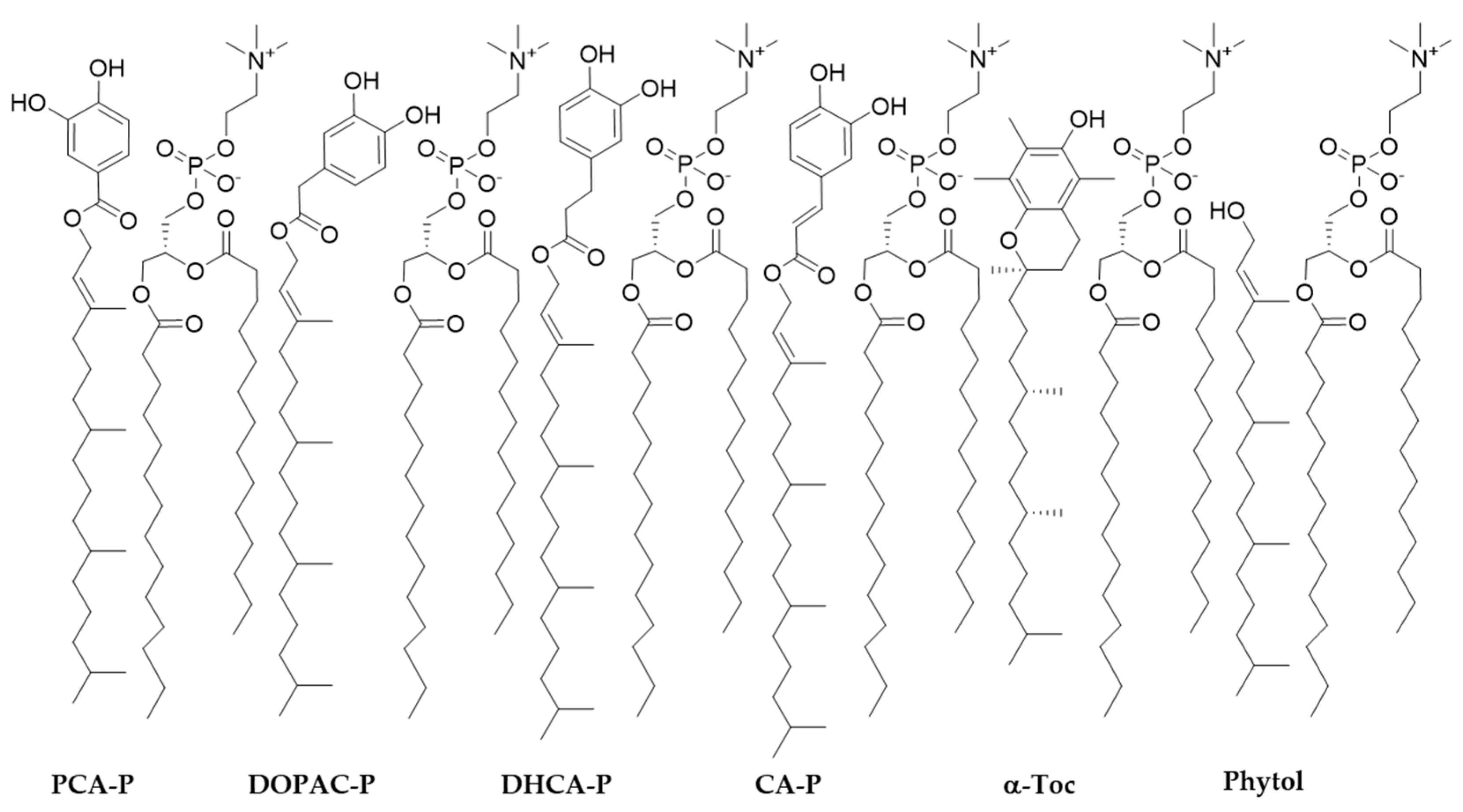

2.1. Synthesis of Phytyl Phenolipids

2.2. Evaluation of Free Radical Scavenging Capacity of Phytyl Phenolipids

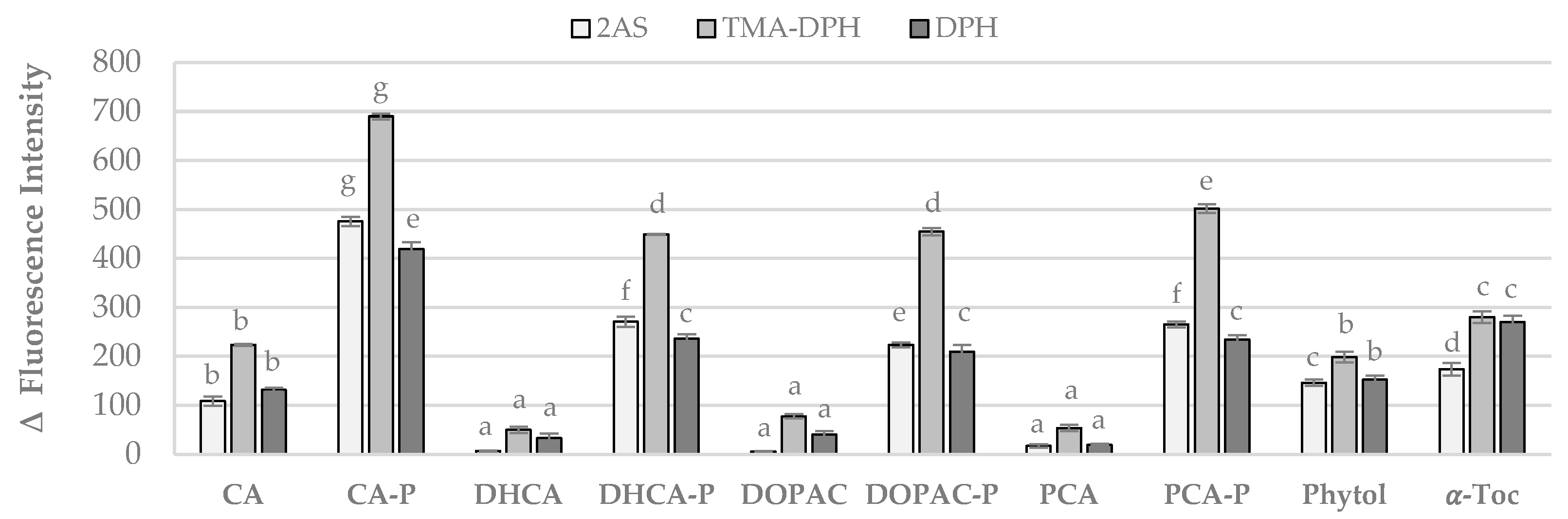

2.3. Interaction of Compounds with Liposomal Membranes

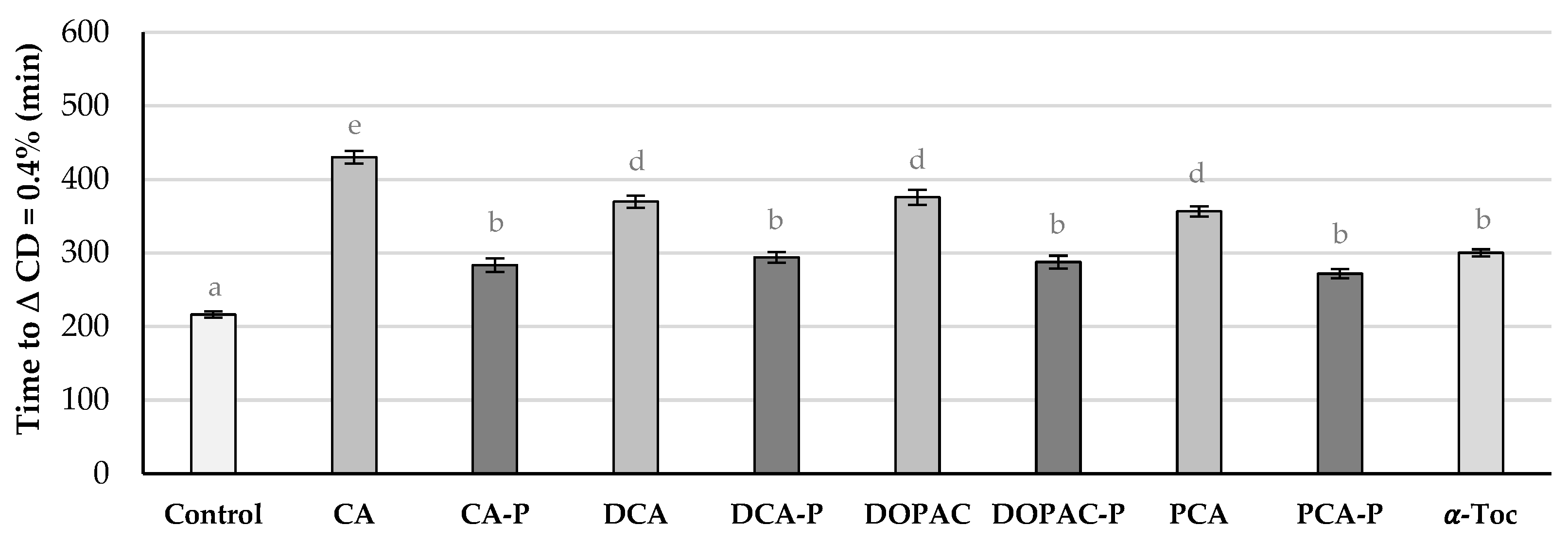

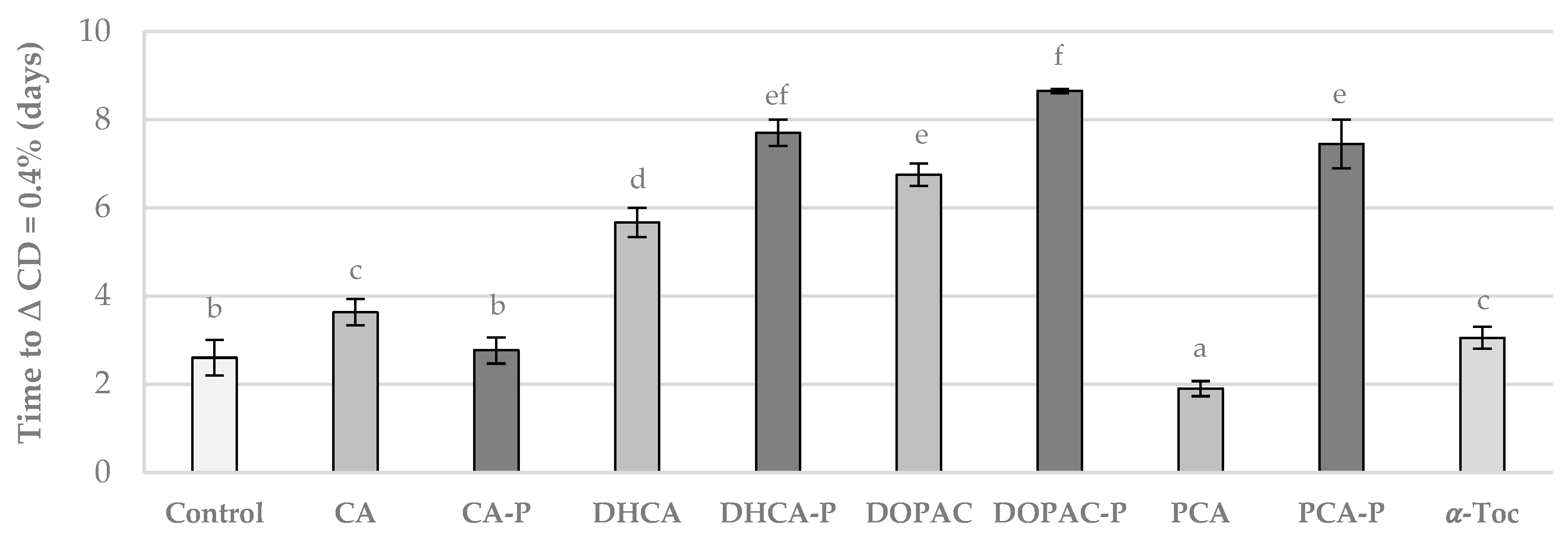

2.4. Antioxidant Capacity of Phytyl Phenolipids in Liposomal Systems

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Synthesis of Phytyl Esters of Polyphenolic Acids

3.2.1. Synthesis of CA-P

3.2.2. Synthesis of DHCA-P and DOPAC-P

3.2.3. Synthesis of PCA-P

3.3. Determination of milogP Values

3.4. DPPH Radical Scavenging Capacity

3.5. Cyclic Voltammetry

3.6. Preparation of Large Unilamellar Vesicles

3.7. Dynamic Light Scattering Measurements

3.8. Fluorescence Quenching Measurements

3.9. Effect of Compounds on the Fluorescence Polarization of Probes

3.10. Evaluation of the Antioxidant Activity of Compounds in PC Liposomes

3.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tomlinson, B.; Wu, Q. Y.; Zhong, Y. M.; Li, Y. H. Advances in Dyslipidaemia Treatments: Focusing on ApoC3 and ANGPTL3 Inhibitors. J Lipid Atheroscler 2024, 13(1), 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilson, J.; Mantovani, A.; Byrne, C. D.; Targher, G. Steatotic liver disease, MASLD and risk of chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Metab 2024, 50(1), 101506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibullah, M.; Jemmieh, K.; Ouda, A.; Haider, M. Z.; Malki, M. I.; Elzouki, A.-N. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: a selective review of pathogenesis, diagnostic approaches, and therapeutic strategies. Frontiers in Medicine 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Fleishman, J. S.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Ren, Z.; Chen, J.; Ding, M. Pharmacological therapy of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease-driven hepatocellular carcinoma. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipovic, B.; Marjanovic-Haljilji, M.; Mijac, D.; Lukic, S.; Kapor, S.; Kapor, S.; Starcevic, A.; Popovic, D.; Djokovic, A. Molecular Aspects of MAFLD—New Insights on Pathogenesis and Treatment. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2023, 45(11), 9132–9148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, P.; Martin, A.; Lang, S.; Kütting, F.; Goeser, T.; Demir, M.; Steffen, H.-M. NAFLD and cardiovascular diseases: a clinical review. Clinical Research in Cardiology 2021, 110(7), 921–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Bai, H.; Mather, B.; Hill, M. A.; Jia, G.; Sowers, J. R. Diabetic Vasculopathy: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Insights. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25(2), 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell-Wiley, T. M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L. E.; Després, J.-P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C. J.; Lear, S. A.; Ndumele, C. E.; Neeland, I. J.; Sanders, P.; St-Onge, M.-P.; On behalf of the American Heart Association Council on, L.; Cardiometabolic, H.; Council on, C.; Stroke, N.; Council on Clinical, C.; Council on, E.; Prevention; Stroke, C. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143(21), e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma, L.; Stancu, C. S.; Sima, A. V. Endothelial Dysfunction in Diabetes Is Aggravated by Glycated Lipoproteins; Novel Molecular Therapies. Biomedicines 2021, 9(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Zaninotto, P. Lower socioeconomic status and the acceleration of aging: An outcome-wide analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117(26), 14911–14917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, M. S. Natural Antioxidants: Sources, Compounds, Mechanisms of Action, and Potential Applications. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2011, 10(4), 221–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V.; Costa, M.; Arques, F.; Ferreira, M.; Gameiro, P.; Geraldo, D.; Monteiro, L. S.; Paiva-Martins, F. Cholesteryl Phenolipids as Potential Biomembrane Antioxidants. Molecules 2024, 29(20), 4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalas, J.; Claise, C.; Edeas, M.; Messaoudi, C.; Vergnes, L.; Abella, A.; Lindenbaum, A. Effect of ethyl esterification of phenolic acids on low-density lipoprotein oxidation. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2001, 55(1), 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Katsoura, M. H.; Polydera, A. C.; Tsironis, L. D.; Petraki, M. P.; Rajacić, S. K.; Tselepis, A. D.; Stamatis, H. Efficient enzymatic preparation of hydroxycinnamates in ionic liquids enhances their antioxidant effect on lipoproteins oxidative modification. N Biotechnol 2009, 26(1-2), 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.; Costa, M.; Ferreira, M.; Gameiro, P.; Fernandes, S.; Catarino, C.; Santos-Silva, A.; Paiva-Martins, F. Caffeic acid phenolipids in the protection of cell membranes from oxidative injuries. Interaction with the membrane phospholipid bilayer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2021, 1863(12), 183727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, R.; Costa, M.; Ferreira, M.; Gameiro, P.; Paiva-Martins, F. A new family of hydroxytyrosol phenolipids for the antioxidant protection of liposomal systems. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2021, 1863(2), 183505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabiej-Kozioł, D.; Roszek, K.; Krzemiński, M. P.; Szydłowska-Czerniak, A. Phenolipids as new food additives: from synthesis to cell-based biological activities. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess 2022, 39(8), 1365–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M. T.; Ali, E. S.; Uddin, S. J.; Shaw, S.; Islam, M. A.; Ahmed, M. I.; Chandra Shill, M.; Karmakar, U. K.; Yarla, N. S.; Khan, I. N.; Billah, M. M.; Pieczynska, M. D.; Zengin, G.; Malainer, C.; Nicoletti, F.; Gulei, D.; Berindan-Neagoe, I.; Apostolov, A.; Banach, M.; Yeung, A. W. K.; El-Demerdash, A.; Xiao, J.; Dey, P.; Yele, S.; Jóźwik, A.; Strzałkowska, N.; Marchewka, J.; Rengasamy, K. R. R.; Horbańczuk, J.; Kamal, M. A.; Mubarak, M. S.; Mishra, S. K.; Shilpi, J. A.; Atanasov, A. G. Phytol: A review of biomedical activities. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2018, 121, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S. P.; Sashidhara, K. V. Lipid lowering agents of natural origin: An account of some promising chemotypes. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2017, 140, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condo, A. M.; Baker, D. C.; Moreau, R. A.; Hicks, K. B. Improved Method for the Synthesis of trans-Feruloyl-β-sitostanol. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2001, 49(10), 4961–4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler-Moser, J. K.; Hwang, H.-S.; Bakota, E. L.; Palmquist, D. A. Synthesis of steryl ferulates with various sterol structures and comparison of their antioxidant activity. Food Chemistry 2015, 169, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Z.; Shahidi, F. Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Phytosteryl Ferulates and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Activity. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2011, 59(23), 12375–12383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Losada-Barreiro, S.; Paiva-Martins, F.; Bravo-Díaz, C.; Romsted, L. S. A direct correlation between the antioxidant efficiencies of caffeic acid and its alkyl esters and their concentrations in the interfacial region of olive oil emulsions. The pseudophase model interpretation of the "cut-off" effect. Food Chem 2015, 175, 233-42.

- Almeida, J.; Losada-Barreiro, S.; Costa, M.; Paiva-Martins, F.; Bravo-Díaz, C.; Romsted, L. S. Interfacial Concentrations of Hydroxytyrosol and Its Lipophilic Esters in Intact Olive Oil-in-Water Emulsions: Effects of Antioxidant Hydrophobicity, Surfactant Concentration, and the Oil-to-Water Ratio on the Oxidative Stability of the Emulsions. J Agric Food Chem 2016, 64(25), 5274–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pletcher, D.; Greff, R.; Peat, R.; Peter, L. M.; Robinson, J. In Instrumental Methods in Electrochemistry, Pletcher, D.; Greff, R.; Peat, R.; Peter, L. M.; Robinson, J., Eds. Woodhead Publishing: 2010; pp 15-41.

- Kaiser, R. D.; London, E. Determination of the depth of BODIPY probes in model membranes by parallax analysis of fluorescence quenching. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1998, 1375 (1), 13-22.

- Terao, J.; Piskula, M.; Yao, Q. Protective Effect of Epicatechin, Epicatechin Gallate, and Quercetin on Lipid Peroxidation in Phospholipid Bilayers. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 1994, 308(1), 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada-Barreiro, S.; Paiva-Martins, F.; Bravo-Díaz, C. Analysis of the Efficiency of Antioxidants in Inhibiting Lipid Oxidation in Terms of Characteristic Kinetic Parameters. Antioxidants 2024, 13(5), 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva-Martins, F.; Gordon, M. Effects of pH and ferric ions on the antioxidant activity of olive polyphenols in oil-in-water emulsions. JAOCS, Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society 2002, 79, 571-576.

- Paiva-Martins, F.; Gordon, M. H. Interactions of ferric ions with olive oil phenolic compounds. J Agric Food Chem 2005, 53(7), 2704–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, C.; Gameiro, P.; Prieto, M.; de Castro, B. Interaction of rifampicin and isoniazid with large unilamellar liposomes: spectroscopic location studies. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2003, 1620 (1), 151-159.

- Lakowicz, J. R. Fluorescence Anisotropy. In Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy Springer, Ed. Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp 353-382.

- Silva, R. O.; Sousa, F. B.; Damasceno, S. R.; Carvalho, N. S.; Silva, V. G.; Oliveira, F. R.; Sousa, D. P.; Aragão, K. S.; Barbosa, A. L.; Freitas, R. M.; Medeiros, J. V. Phytol, a diterpene alcohol, inhibits the inflammatory response by reducing cytokine production and oxidative stress. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2014, 28(4), 455–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, C. C.; Salvadori, M. S.; Mota, V. G.; Costa, L. M.; de Almeida, A. A.; de Oliveira, G. A.; Costa, J. P.; de Sousa, D. P.; de Freitas, R. M.; de Almeida, R. N. Antinociceptive and Antioxidant Activities of Phytol In Vivo and In Vitro Models. Neurosci J 2013, 2013, 949452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jéssica, P. C.; Md, T. I.; Pauline, S. S.; Paula, B. F.; George, L. S. O.; Marcus, V. O. B. A.; Marcia, F. C. J. P.; Éverton, L. F. F.; Chistiane, M. F.; Antonia, M. G. L. C.; Damião, P. S.; Ana Amelia, C. M.-C. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity of Phytol Using Non- and Pre-Clinical Models. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology 2016, 17(14), 1278–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M. T.; Ayatollahi, S. A.; Zihad, S.; Sifat, N.; Khan, M. R.; Paul, A.; Salehi, B.; Islam, T.; Mubarak, M. S.; Martins, N.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Phytol anti-inflammatory activity: Pre-clinical assessment and possible mechanism of action elucidation. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2020, 66 (4), 264-269.

- de Alencar, M. V. O. B.; Islam, M. T.; da Mata, A. M. O. F.; dos Reis, A. C.; de Lima, R. M. T.; de Oliveira Ferreira, J. R.; de Castro e Sousa, J. M.; Ferreira, P. M. P.; de Carvalho Melo-Cavalcante, A. A.; Rauf, A.; Hemeg, H. A.; Alsharif, K. F.; Khan, H. Anticancer effects of phytol against Sarcoma (S-180) and Human Leukemic (HL-60) cancer cells. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30(33), 80996–81007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobe, G.; Zhang, Z.; Kopp, R.; Garzotto, M.; Shannon, J.; Takata, Y. Phytol and its metabolites phytanic and pristanic acids for risk of cancer: current evidence and future directions. Eur J Cancer Prev 2020, 29(2), 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hu, X.; Ai, W.; Zhang, F.; Yang, K.; Wang, L.; Zhu, X.; Gao, P.; Shu, G.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, S. Phytol increases adipocyte number and glucose tolerance through activation of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in mice fed high-fat and high-fructose diet. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2017, 489(4), 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaccio, F.; D′Arino, A.; Caputo, S.; Bellei, B. Focus on the Contribution of Oxidative Stress in Skin Aging. Antioxidants 2022, 11(6), 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Acid Catalysis | Enzymatic Catalysis | |||||

| Toluene | THF | Toluene | Dioxane | DCM | THF | ||

| DCA-P | NR | 17% | 95% | 50% | NR | NR | |

| DOPAC-P | NR | 56% | 46% | 83% | NR | NR | |

| PCA-P | NR | NR | 18% | 0% | NR | NR | |

| Compound | miLog P | EC50** | Compound | miLog P | EC50** | ||

| 5 min | 30 min | 5 min | 30 min | ||||

| Phytol | 6.76 | - | - | α-Toc | 9.04 | 0.33 | 0.29 |

| PCA | 0.86 | 0.22 | 0.19 | PCA-P | 8.20 | 0.19 | 0.14 |

| DOPAC | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.13 | DOPAC-P | 8.09 | 0.21 | 0.18 |

| DHCA | 0.91 | 0.19 | 0.13 | DHCA-P | 8.26 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| CA | 0.94 | 0.23 | 0.21 | CA-P | 8.49 | 0.23 | 0.22 |

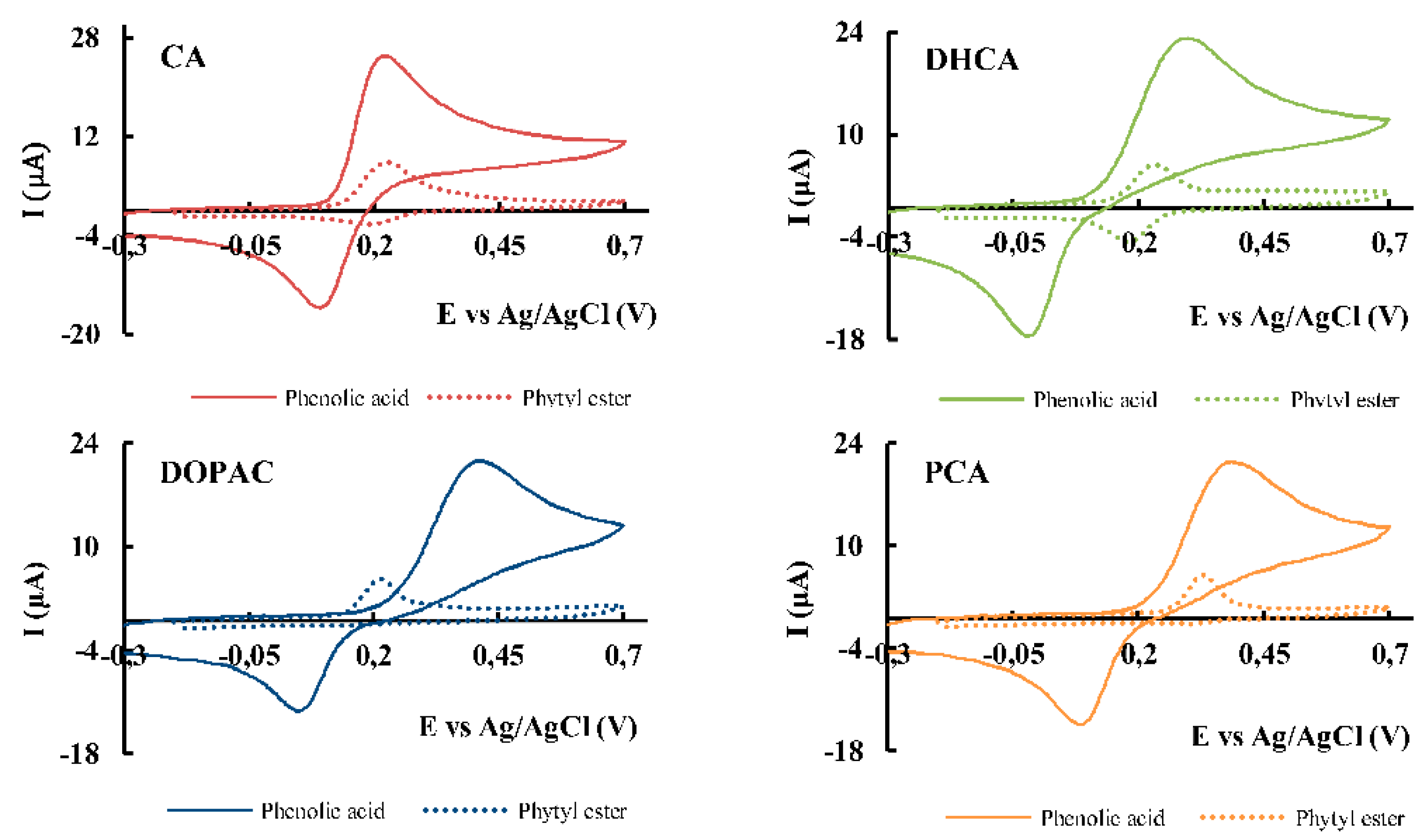

| Compound | Epa (V)* | Epc (V)* | Ipa (µA)* | - Ipc (µA)* | Compound | Epa (V)* | Epc (V)* | Ipa (µA)* | - Ipc (µA)* |

| CA | 0.223 | 0.091 | 21.67 | 17.79 | CA-P | 0.235 | 0.198 | 6.71 | 2.25 |

| DHCA | 0.297 | -0.026 | 17.31 | 14.63 | DHCA-P | 0.250 | 0.171 | 4.49 | 4.22 |

| DOPAC | 0.403 | 0.053 | 14.67 | 12.72 | DOPAC-P | 0.219 | - | 4.56 | - |

| PCA | 0.387 | 0.082 | 15.18 | 10.35 | PCA-P | 0.327 | 0.303 | 4.55 | 0.35 |

| α-Toc | 0.219 | - | 4.10 | - |

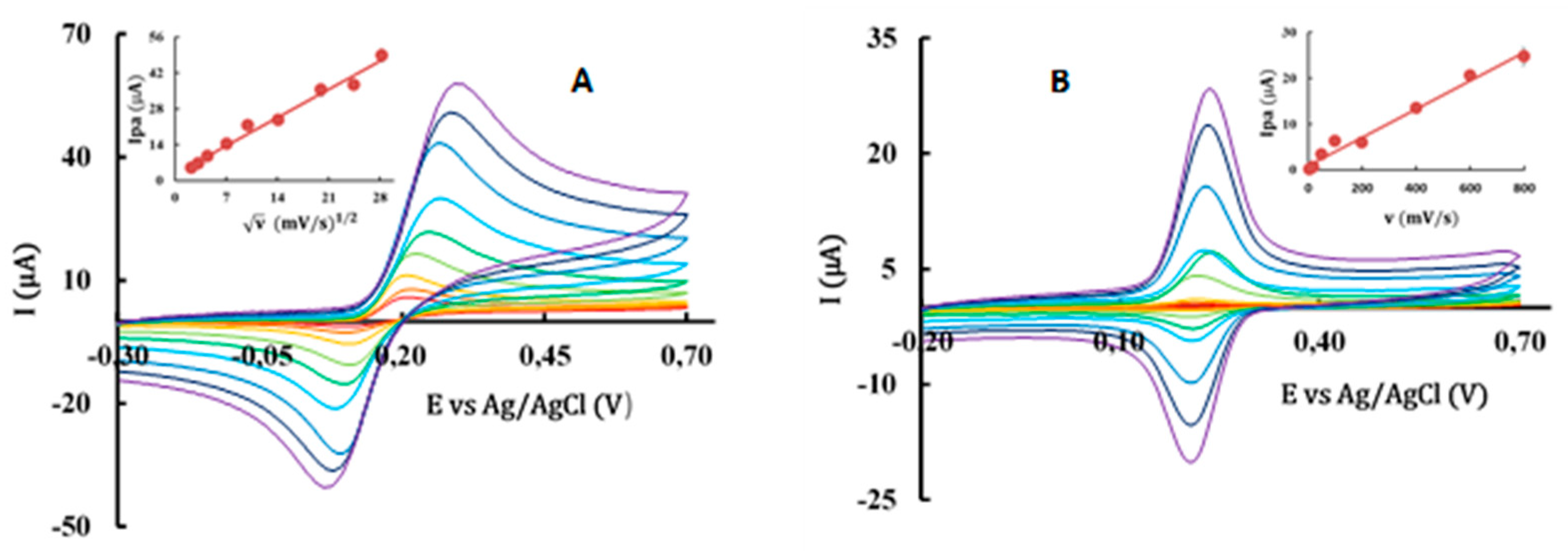

| Compound | Anodic process | Cathodic process | Controlled by | |||

| Linear regression equation | r | Linear regression equation | r | |||

| CA | Ip = (1.57 ± 0.08) v1/2 + (2.6 ± 1.2) | 0.991 | -Ip = (1.63 ± 0.07) v1/2 + (-0.6 ± 1.2) | 0.993 | Diffusion | |

| DHCA | Ip = (1.54 ± 0.04) v1/2 + (2.0 ± 0.6) | 0.998 | -Ip = (1.23 ± 0.09) v1/2 + (1.0 ± 1.4) | 0.98 | Diffusion | |

| PCA | Ip = (1.43 ± 0.01) v1/2 + (1.0 ± 0.2) | 0.9996 | -Ip = (1.25 ± 0.03) v1/2 + (-0.9 ± 0.5) | 0.998 | Diffusion | |

| DOPAC | Ip = (1.30 ± 0.02) v1/2 + (2.1 ± 0.3) | 0.9993 | -Ip = (1.20 ± 0.04) v1/2 + (-1.5 ± 0.7) | 0.995 | Diffusion | |

| CA-P | Ip = (0.031 ± 0.002) v + (0.9 ± 0.6) | 0.991 | -Ip = (0.0231 ± 0.0004) v + (-0.2 ± 0.1) | 0.9992 | Adsorption | |

| DHCA-P | Ip = (0.0388 ± 0.0006) v + (0.8 ± 0.1) | 0.9993 | -Ip = (0.054 ± 0.001) v + (-0.8 ± 0.4) | 0.997 | Adsorption | |

| PCA-P | Ip = (0.030 ± 0.001) v + (0.7 ± 0.4) | 0.994 | -Ip = (0.0125 ± 0.0006) v + (-0.5 ± 0.2) | 0.993 | Adsorption | |

| DOPAC-P | Ip = (0.0251 ± 0.0009) v + (1.0 ± 0.3) | 0.996 | - | - | Adsorption | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).