1. Introduction

In recent years, the remarkable pace of semiconductor fabrication technology advancements has been largely driven by the relentless demand for electronic devices that are not only smaller and faster but also more reliable and efficient. The continuous push for innovation in this sector has brought about numerous breakthroughs; however, it has simultaneously introduced significant technical challenges that have become increasingly difficult to overcome. One of the primary challenges arises from the physical limitations associated with the ongoing miniaturization of transistors, which now threaten to slow the progression of Moore's Law [

1], a principle that has guided the semiconductor industry for decades. As the dimensions of transistors approach atomic scales, fundamental constraints related to quantum effects, heat dissipation, and power efficiency begin to dominate, making it increasingly difficult to sustain the exponential improvements in transistor density and performance that Moore's Law predicts. In light of these challenges, the semiconductor industry has shifted its focus toward alternative strategies that go beyond the traditional approach of simply scaling down transistor sizes. This shift has led to the development of what is often referred to as the "More than Moore" paradigm, which emphasizes heterogeneous integration through advanced packaging technologies [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Unlike the conventional scaling methods that focus solely on transistor miniaturization, the "More than Moore" approach seeks to enhance system performance by integrating multiple functions into a single package. These functions can include processing, memory, sensing, and communication, all of which are combined into a compact and highly efficient package. This approach has gained significant traction in recent years as a means of overcoming the limitations imposed by transistor scaling, offering a path forward for the continued advancement of electronic devices.

Among the various innovative packaging technologies that have been developed in support of the "More than Moore" paradigm, Fan-out wafer-level packaging (FOWLP) has emerged as one of the most promising solutions. FOWLP stands out due to its ability to deliver several key advantages that are highly sought after in the industry, including a higher I/O (input/output) density, a reduced form factor, and improved electrical performance. These advantages make FOWLP an ideal candidate for heterogeneous system integration, where multiple components with different functions and characteristics must be brought together into a single, cohesive package. By reducing the overall footprint of the package while simultaneously improving its performance, FOWLP enables manufacturers to meet the growing demand for smaller and more powerful electronic devices. Moreover, the integration of various components into a single package using FOWLP helps reduce the overall complexity of the system, leading to cost savings and greater efficiency in the manufacturing process. Despite its widespread recognition and growing adoption in the semiconductor industry, FOWLP is not without its challenges. As with any emerging technology, FOWLP faces several technical hurdles that must be addressed before it can fully realize its potential. Key challenges include optimizing yields, enhancing reliability, managing thermal dissipation, and, perhaps most critically, controlling warpage during the manufacturing process. Warpage, in particular, presents a significant obstacle, as it can manifest at various stages of the FOWLP manufacturing process and have far-reaching consequences for the overall performance and reliability of the final product. The deformation that results from warpage can lead to a range of issues, including misalignment of components, inaccuracies in material handling, and errors in registration during assembly. These issues, in turn, can result in reduced manufacturing yields, increased production costs, and diminished overall efficiency [

6,

9].

Given the significant impact that warpage can have on both the manufacturing process and the final product, it is critical to develop a deep understanding of the factors that contribute to warpage in FOWLP. This understanding must begin at the design phase, where the materials, geometries, and assembly processes used in FOWLP can be carefully analyzed and optimized to minimize warpage. Achieving this level of understanding, however, requires a comprehensive approach that combines both theoretical modeling and experimental validation. Unfortunately, despite the critical importance of this issue, existing research in the field has provided relatively limited insights into the underlying mechanisms that drive warpage in FOWLP [

10]. The lack of extensive theoretical and experimental characterization presents a significant barrier to the development of effective warpage control strategies, and this gap in knowledge must be addressed in order to enable further advancements in FOWLP technology.

Theoretical approaches, such as finite element analysis (FEA), have emerged as powerful tools for investigating the complex interactions that lead to warpage in FOWLP. FEA offers a cost-effective and efficient means of exploring the underlying physical mechanisms that contribute to warpage, allowing researchers and engineers to simulate various design scenarios and assess their impact on warpage before actual fabrication begins. By utilizing FEA, it is possible to model the behavior of materials under thermal and mechanical loads, examine how different packaging geometries affect deformation, and predict the conditions under which warpage is likely to occur. This predictive capability is invaluable for optimizing FOWLP designs, as it enables designers to anticipate potential issues and implement corrective measures during the early stages of the development process. Although FEA and other theoretical modeling techniques offer substantial advantages in terms of cost and efficiency, they are not without limitations. The accuracy of these models is heavily dependent on the quality of the input data, including the material properties and boundary conditions used in the simulations. Moreover, FEA models often rely on certain simplifying assumptions, which can limit their ability to fully capture the complexity of real-world manufacturing environments. As a result, while FEA provides valuable insights into the potential causes of warpage, experimental validation remains an essential component of the overall process. Experimental methods, such as in-situ monitoring of warpage during the manufacturing process, can provide the empirical data needed to refine and validate theoretical models. This iterative process of theoretical modeling and experimental validation is crucial for achieving a comprehensive understanding of warpage and developing effective control strategies.

As global digitalization continues to advance at a rapid pace, electronic products have become intricately woven into the fabric of everyday life, fundamentally altering how individuals across the world work, communicate, and conduct their daily activities. These products offer an unprecedented level of convenience, reshaping industries and enhancing the quality of life on a massive scale. From indispensable devices like smartphones, tablets, and wearable technology to more complex systems such as smart home appliances, autonomous vehicles, and sophisticated aerospace applications, the proliferation of electronic products is ubiquitous. Their impact extends far beyond individual consumer usage, influencing economic structures, social interactions, and the broader trajectory of technological progress. The innovations that have emerged from these advancements not only serve to enhance daily living but have also played a pivotal role in driving forward societal and industrial transformation.

Nevertheless, the technological marvels that these electronic products represent are underpinned by exceptionally complex manufacturing processes, with the packaging design stage presenting some of the most significant and intricate challenges. Packaging design is a critical component of the overall manufacturing process, as it directly affects the performance, reliability, and durability of the final product. Designers working in this domain must navigate a multitude of factors that contribute to the successful integration of various electronic components within a limited space. Among these factors are the careful selection of materials, which must meet stringent thermal, mechanical, and electrical criteria, and the determination of optimal process parameters, which are crucial for ensuring the reliability of the final product under operational stress. Workflow design is equally important, as it involves the coordination of multiple manufacturing steps to ensure that the final assembly meets performance specifications while remaining cost-effective. These considerations demand not only a deep understanding of the technical aspects of packaging design but also an ability to anticipate and respond to the evolving requirements of both the market and the technology itself.

As technological advancements continue to accelerate and market demands become increasingly diverse, the challenges faced by packaging designers are only becoming more complex. The traditional methods of packaging design, which once sufficed in addressing the relatively straightforward demands of earlier electronic products, are now proving inadequate for the intricate systems being developed today. The rise of heterogeneous integration, advanced semiconductor packaging technologies, and the push for miniaturization are all placing new and significant demands on the packaging design process. In this rapidly evolving landscape, designers are tasked with balancing the competing needs for reduced size, improved performance, and enhanced reliability, all while ensuring that the manufacturing process remains scalable and cost-efficient.

To address the complexities and challenges faced in modern packaging design, particularly in the realm of microelectronics, researchers have increasingly turned to artificial intelligence (AI) in combination with advanced simulation methodologies [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. AI has rapidly evolved into an essential tool for solving highly intricate problems across a broad range of disciplines, encompassing fields as diverse as medical diagnostics, autonomous transportation systems, space exploration missions, defense technologies, and various engineering domains. Its application in these areas has demonstrated the unparalleled ability of AI to manage and analyze vast datasets, identify patterns, and generate predictive models that offer unprecedented accuracy and efficiency. In the context of microelectronic packaging, AI-driven simulation models have become indispensable for evaluating critical aspects such as thermal-mechanical performance, which includes understanding the thermal behavior of packaging systems [

12,

13] and predicting system reliability [

14,

15,

16]. These areas are particularly challenging due to the complex interactions between materials, geometries, and environmental conditions, all of which must be accounted for to ensure the performance and longevity of the electronic device.

To achieve these objectives, a wide array of machine learning techniques has been employed, each offering unique advantages in terms of predictive capabilities and computational efficiency. Techniques such as support vector regression (SVR) [

11], random forest (RF) [

16], gradient boosting regression (GBR) [

17], K-nearest neighbors (KNN) [

18], and kernel ridge regression (KRR) [

19] have all been successfully applied to model various performance parameters in microelectronic packaging. These machine learning algorithms have the capacity to process large amounts of structured data, uncover complex relationships within the data, and generate predictions that can guide the design process. For instance, GBR has proven highly effective in handling non-linear relationships within datasets, while SVR offers robust performance by mapping data into high-dimensional feature spaces. KNN, with its straightforward approach to regression and classification tasks, remains a valuable tool in instances where the decision boundaries between data points are difficult to define, while KRR and RF provide powerful methods for handling noisy data and complex interactions between variables.

In addition to these machine learning models, several deep learning architectures have also been employed in the study of microelectronic packaging, further enhancing the ability to predict and optimize system performance. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) [

20], gated recurrent units (GRUs) [

21], multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) [

22], and long short-term memory networks (LSTMs) [

23,

24] have all demonstrated their effectiveness in capturing intricate, temporal dependencies within datasets and predicting long-term performance trends. These deep learning models are particularly adept at managing sequential and time-series data, making them ideal for tasks that require continuous monitoring of system behavior under varying conditions. In practice, AI techniques have been applied in a variety of scenarios to improve the thermal and mechanical performance of packaging structures. For example, Law et al. [

12] developed an artificial neural network (ANN) model capable of predicting the thermal behavior of quad flat no-lead (QFN) packages, demonstrating the potential of AI in capturing complex thermal dynamics. Similarly, Subbarayan et al. [

14] employed a similar approach to build a reliability prediction model for ball grid array (BGA) packages, further highlighting the versatility of AI in addressing different packaging designs. In more recent studies, Hsiao and Chiang [

16] utilized the random forest algorithm to forecast the reliability lifespan of WLP through FEA simulations, validating their model against empirical data. The ability of the random forest algorithm to process large datasets with high accuracy while avoiding overfitting proved invaluable for this application. Additionally, Panigrahy et al. [

25] explored the optimization of WLP reliability using AI-assisted design-on-simulation technologies, comparing multiple algorithms, including ANN, RNN, SVR, KRR, KNN, and RF. Their study not only demonstrated the predictive accuracy of these methods but also shed light on their computational efficiency, which is an increasingly important consideration as simulations grow in complexity. Kuo et al. [

26] further expanded upon this by applying SVR techniques with both single and multiple kernel functions to predict the reliability of WLPs, demonstrating the flexibility of SVR in adapting to different dataset structures. Cheng et al. [

27] also contributed to this body of work by developing an ANN-based model capable of predicting the warpage behavior of flip-chip chip-scale packages (FCCSP), achieving high computational efficiency and accuracy. These simulation models account for various material behaviors, including viscoelasticity, and incorporate temperature-dependent thermal-mechanical properties to closely match real-world conditions. Each of these studies underscores the growing importance of AI in microelectronic packaging, where the ability to predict performance and reliability is crucial for advancing next-generation technologies.

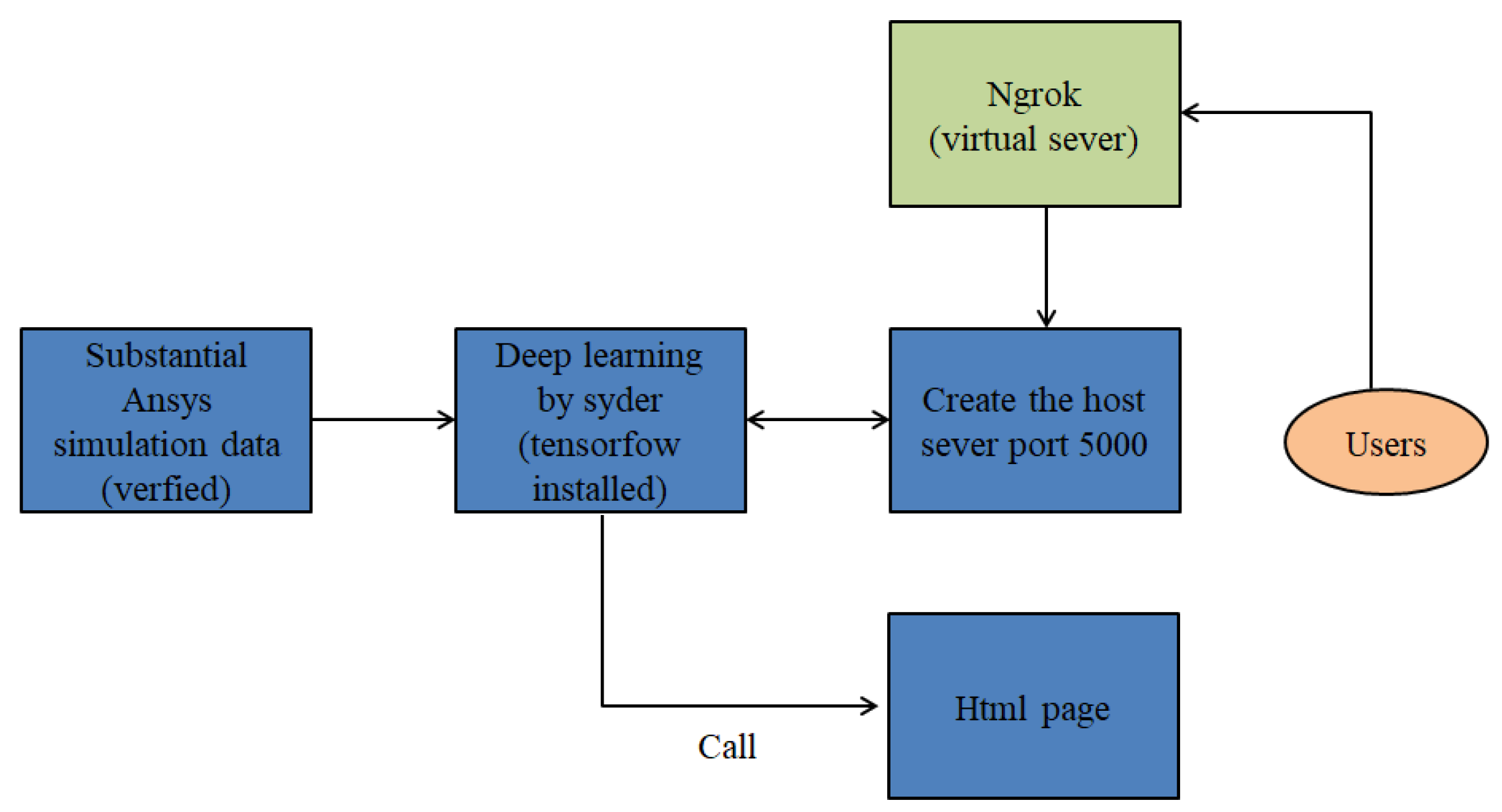

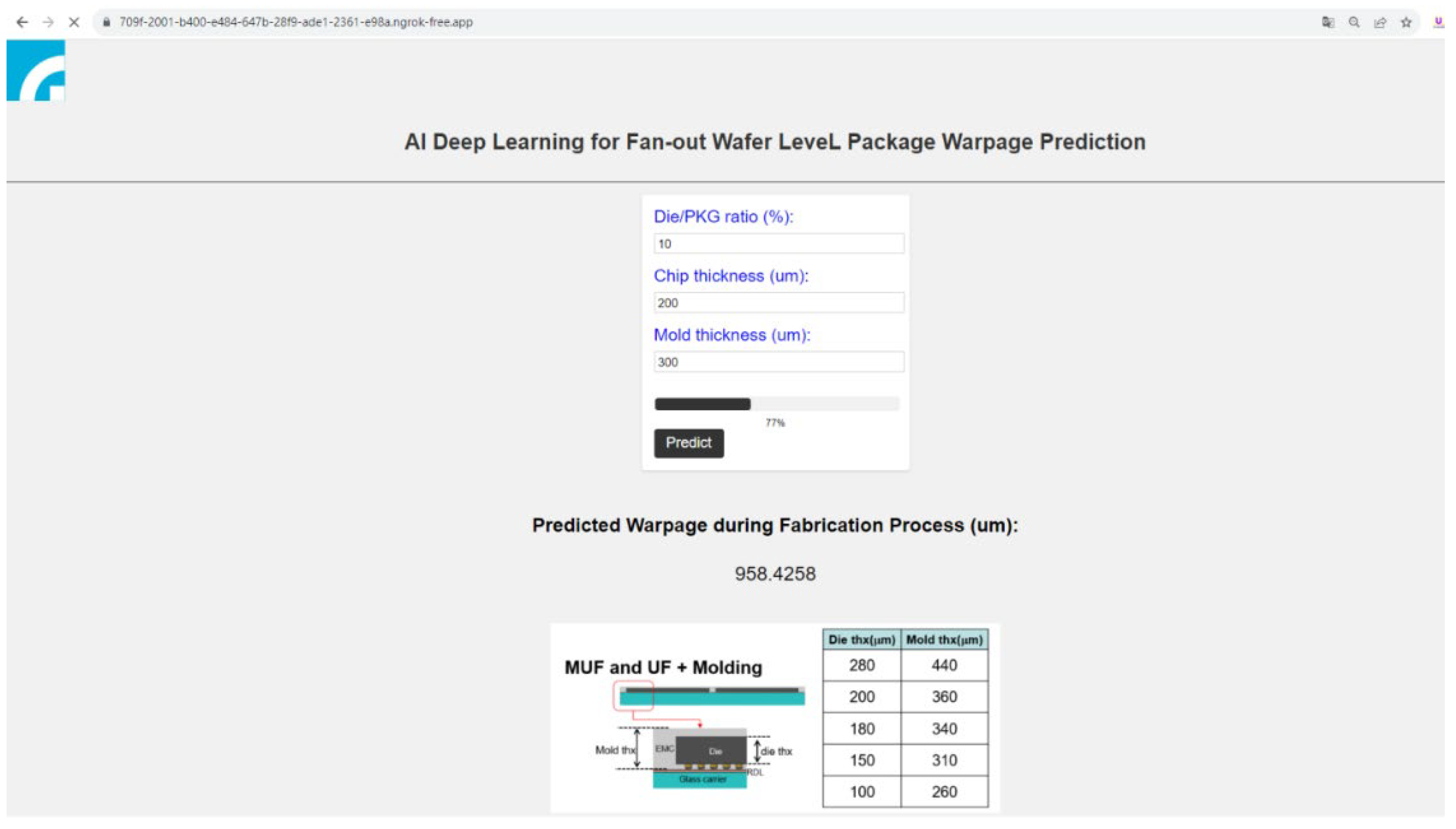

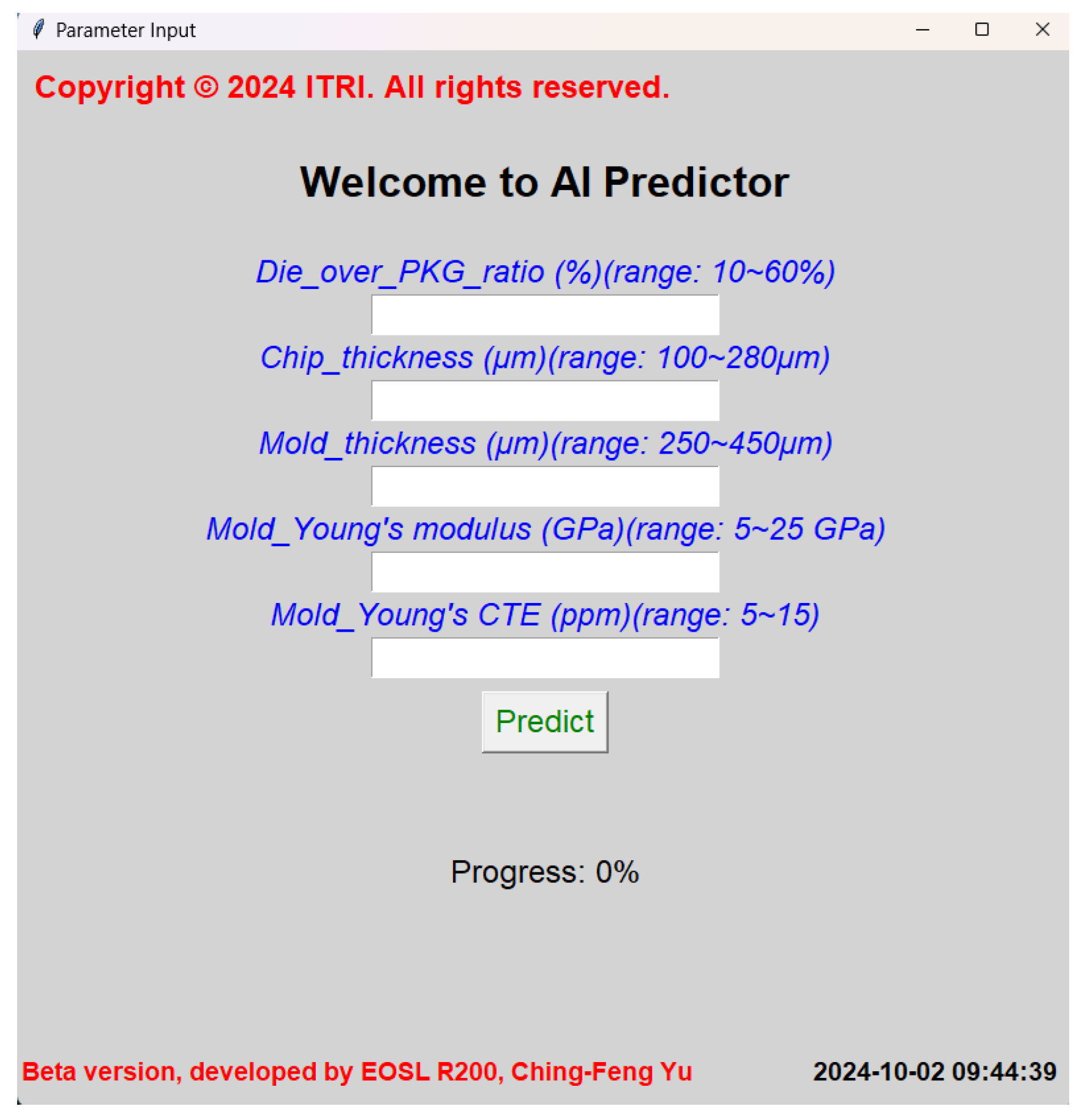

Building upon these important developments, this study aims to address a critical gap in the existing literature regarding warpage prediction for FOWLP by developing a novel predictive model. This model integrates FEA with advanced AI techniques to provide rapid, accurate assessments of process-induced warpage behavior, an issue that has long challenged the microelectronics manufacturing sector. A major innovation in this research is the introduction of a user-friendly graphical user interface (GUI) that complements the predictive model. This feature, which has been largely absent in prior studies, is particularly significant as it enhances both the accessibility and usability of the model for engineers and practitioners. Previous research, while focused on the technical accuracy and development of predictive models, has not placed sufficient emphasis on creating user-centric interfaces that facilitate widespread adoption in industry settings. The inclusion of a GUI in this study not only addresses that shortcoming but also elevates the functionality of the model by allowing users to input design parameters intuitively and observe real-time visualizations of warpage predictions. This real-time interaction transforms the design workflow, making it more efficient and accessible. The introduction of the GUI serves to democratize the use of advanced predictive models, bridging the gap between highly technical machine learning methodologies and practical engineering applications. This approach empowers a broader range of users, including those who may have limited expertise in AI or simulation technologies, to engage with complex predictive tools. Moreover, by simplifying the process of obtaining accurate predictions, the GUI plays a crucial role in integrating sophisticated models into the design and manufacturing process, making it easier for engineers to explore multiple design scenarios and optimize their solutions. Thus, this work provides an innovative contribution to the field, fostering greater accessibility and practical application of advanced modeling techniques in the context of FOWLP.

In this study, various machine learning approaches, including SVR [

11], RF [

16], GBR [

17], KNN [

18], and KRR [

19], are examined in conjunction with deep learning methods such as RNN [

20], GRU [

21], MLP [

22], and LSTM networks [

23,

24]. These methodologies are rigorously compared through a comprehensive evaluation, where the algorithm that demonstrates the closest alignment with FEA data is selected as the core algorithm for integration into the warpage prediction platform. This process of selecting the optimal algorithm ensures that the prediction model reflects the most accurate and reliable results possible, which are critical for further application in real-world scenarios. In addition to the machine learning and deep learning techniques, an FEA-driven process modeling approach is implemented, taking into account the viscoelastic properties of the epoxy molding compound (EMC) and the thermal-mechanical characteristics of the materials used in FOWLP, which vary with temperature. This combination allows for a more detailed understanding of how these material properties affect the warpage behavior during the manufacturing process. By incorporating these critical aspects into the modeling framework, the study provides a more holistic view of the factors influencing warpage. The effectiveness of this integrated modeling methodology is validated by comparing simulated warpage results with experimental data, ensuring that the model is not only theoretically robust but also practically relevant and accurate.

Further enhancing the study, a detailed parametric analysis is conducted to identify the key factors that exert the greatest influence on warpage behavior. These influential factors are carefully incorporated into the construction of the predictive model, ensuring that the model captures all relevant aspects of the process that may contribute to warpage. The inclusion of such detailed parametric variables allows for greater flexibility in the model, as it can be applied across a range of scenarios to predict warpage under different material and process conditions. Moreover, the feasibility and robustness of the developed warpage prediction model, now integrated with a GUI, are thoroughly evaluated using a separate validation dataset. This validation serves to test the performance of the model in predicting warpage under various conditions, ensuring that the predictions remain accurate across diverse testing scenarios. The introduction of the GUI is of particular importance, as it allows engineers to interact with the model in a user-friendly manner, facilitating real-time feedback and aiding significantly in the design process. By enabling users to adjust input parameters dynamically and receive instant predictions, the GUI adds a new layer of practicality to the warpage prediction model, making it more accessible and usable for industry professionals who may not be experts in machine learning or simulation techniques. This study goes beyond improving the accuracy of warpage prediction models for FOWLP by introducing a novel, intuitive GUI that dramatically enhances the usability of the model for real-world applications. The integration of this user-friendly interface streamlines the design process, enabling engineers to make more informed decisions quickly, thereby accelerating the overall workflow. By providing real-time predictive capabilities, the GUI-driven model not only improves the efficiency of the design process but also has the potential to significantly improve the performance and reliability of FOWLP systems. This new approach represents a significant advancement in the field, contributing to both the theoretical and practical aspects of microelectronic packaging design.

2. Structure and Fabrication Process of FOWLP

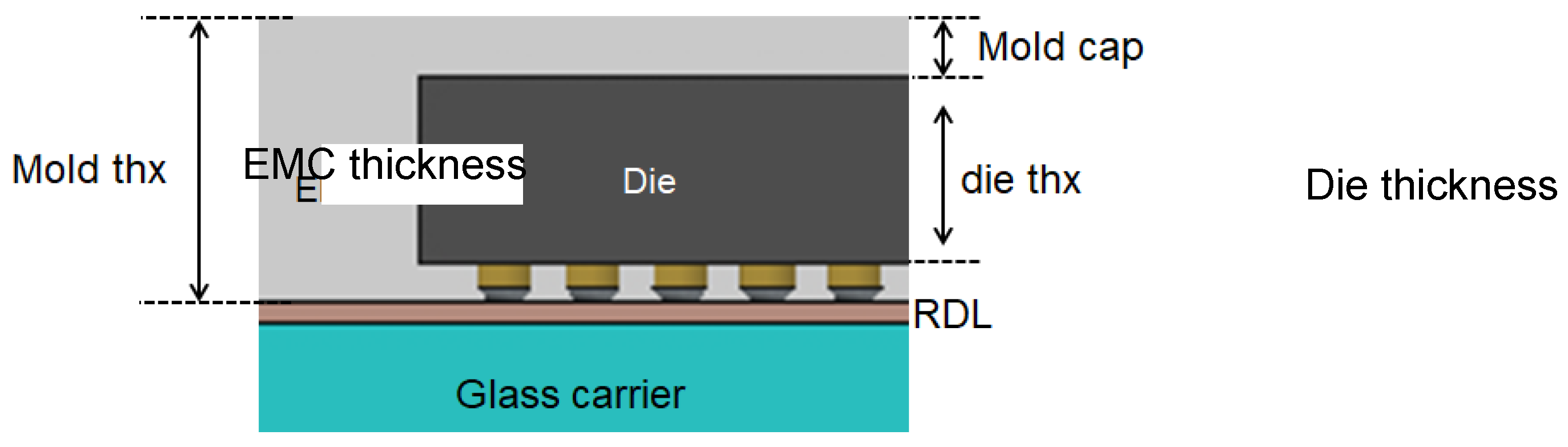

The structure of the FOWLP under investigation is elaborately illustrated in

Figure 1, featuring a series of intricate and essential components that are pivotal to its functionality and reliability. These components include a glass carrier, redistribution layers (RDLs), silicon dies, copper pillar bumps (CPBs), and an EMC. Each element plays a significant role in the overall performance of the FOWLP, contributing to its mechanical strength, thermal stability, and electrical conductivity. The fabrication process of FOWLP begins with the deposition of a polyimide (PI) layer onto the glass carrier, which is a critical step that lays the foundation for the subsequent stages of the packaging process. Polyimide is chosen for its excellent thermal stability, chemical resistance, and mechanical properties, which are essential for maintaining the structural integrity of the package during high-temperature processes. Once the PI layer is deposited, the next crucial step is curing, wherein the carrier is subjected to a controlled heating process, reaching a temperature of approximately 210°C. This elevated temperature ensures that the polyimide layer adheres properly to the glass carrier, creating a stable and durable foundation for the subsequent layers that will be added to the package. The curing process also enhances the thermal stability of the PI layer, ensuring that it can withstand the thermal cycling that the FOWLP will experience during its operation. Following the successful curing of the polyimide layer, the fabrication process progresses to more complex stages that involve the creation of the RDLs. The RDLs are essential components of the FOWLP as they facilitate electrical interconnections between the silicon die and the external environment. The RDLs are typically composed of thin metal lines, such as copper, that are patterned onto the substrate. These metal lines provide a low-resistance path for electrical signals, ensuring efficient signal transmission between the die and the external circuitry. In addition to the RDLs, dielectric layers are also deposited during this stage to provide electrical insulation between the metal lines and other components of the package. The dielectric materials used in FOWLP are carefully selected for their ability to withstand high voltages and temperatures, ensuring the reliability and longevity of the package.

An important stage in the fabrication of FOWLP involves the formation of under bump metallization (UBM), which is a crucial interface between the silicon die and the copper pillar bumps. UBM plays a key role in ensuring a reliable electrical connection and mechanical adhesion between the die and the bumps. The UBM layer is typically composed of metals such as nickel and gold, which provide excellent electrical conductivity and corrosion resistance. The precise deposition of the UBM layer is critical for ensuring the long-term performance of the package, as any defects in this layer can lead to issues such as electrical shorts or mechanical failure. The die bonding process marks a significant step in the assembly of the FOWLP. During this process, the silicon die is carefully aligned and mounted onto the RDL substrate using CPBs as the interconnects. The precise alignment of the die with the bond pads on the substrate is essential for ensuring accurate electrical connections between the die and the substrate. Any misalignment during this stage could result in poor signal transmission or mechanical failure, both of which would compromise the performance of the package. The die bonding process is carried out in a highly controlled environment to minimize the risk of contamination or misalignment.

To ensure the mechanical stability and electrical conductivity of the die-substrate interface, the assembly is heated to a temperature of approximately 260°C. At this elevated temperature, the solder material in the copper pillar bumps melts, forming a strong bond between the silicon die and the substrate. This soldering process not only establishes electrical connectivity but also provides mechanical support to the die, ensuring that it remains securely attached to the substrate even under the stress of thermal cycling or mechanical shock. The high temperature required for this process is carefully controlled to prevent damage to the delicate components of the FOWLP while ensuring the integrity of the solder joints. Once the die bonding process is complete and the die is securely attached to the substrate, the next step involves the application of a liquid-type EMC. The EMC serves several critical functions in the FOWLP. First, it provides mechanical protection to the silicon die, shielding it from physical damage caused by external forces such as vibration, impact, or thermal expansion. Second, the EMC enhances the thermal stability of the package by distributing heat away from the die and preventing localized hotspots. This thermal management is crucial for maintaining the performance and longevity of the electronic components housed within the package. Third, the EMC provides electrical insulation, ensuring that the various conductive elements within the FOWLP remain electrically isolated from one another. This insulation is essential for preventing electrical shorts and ensuring the reliable operation of the package. After the liquid EMC is applied, it undergoes a curing process to solidify and adhere to the underlying components. The curing process is carried out at a temperature of approximately 150°C, which is sufficient to harden the EMC without causing thermal damage to the other components of the FOWLP. The cured EMC provides additional mechanical support to the package, ensuring that the silicon die and other components remain securely in place even under the stress of thermal cycling or mechanical vibrations. Furthermore, the cured EMC enhances the overall reliability of the package by protecting it from environmental factors such as moisture, dust, and chemical contaminants.

In addition to its protective functions, the EMC also contributes to the overall structural integrity of the FOWLP. By encapsulating the silicon die and other components, the EMC helps to distribute mechanical stresses evenly throughout the package, reducing the likelihood of localized failures. This even distribution of stress is particularly important in high-performance electronic applications, where the FOWLP may be subjected to extreme conditions such as high temperatures, rapid thermal cycling, or mechanical shock. The EMC ensures that the package can withstand these conditions without compromising its electrical or mechanical performance. The fabrication of the FOWLP is a highly intricate and precise process, requiring careful attention to detail at every stage. Each component, from the PI layer to the EMC, plays a critical role in ensuring the overall performance, reliability, and longevity of the package. By carefully controlling the deposition, bonding, and curing processes, the FOWLP can be engineered to meet the stringent demands of modern electronic devices, providing a reliable and efficient solution for advanced packaging applications.

3. Theoretical Frameworks of Machine Learning and Deep Learning

In this study, a combination of both machine learning and deep learning techniques is utilized to perform a comprehensive analysis and prediction of complex datasets, addressing the challenges inherent in capturing nuanced patterns within diverse data types. The machine learning approaches employed in this investigation include SVR [

11], RF [

16], GBR [

17], KNN [

18], and KRR [

19]. Each of these methods brings distinct capabilities and strengths to the table, particularly in their ability to process structured data, which is a common characteristic of many real-world datasets. These algorithms excel in creating models that are capable of uncovering intricate relationships within data, and they vary in their approach to learning from the input variables. For instance, GBR is highly effective in handling non-linear relationships by sequentially building a series of models that correct the errors of previous iterations, whereas SVR focuses on constructing hyperplanes in a high-dimensional space to best separate the data points, offering robust performance even in complex scenarios. KNN, on the other hand, is valuable for its simplicity in classification and regression tasks, utilizing distance metrics to make predictions based on the nearest neighbors in the feature space, while KRR merges the strengths of ridge regression with kernel methods to handle non-linearity. In addition, RF is recognized for its ensemble learning approach, which combines multiple decision trees to improve prediction accuracy, reduce overfitting, and handle a diverse range of input data types. This method is particularly advantageous when working with large datasets that contain noisy or unbalanced data, as the averaging of multiple trees mitigates the risk of overfitting, providing stable and reliable predictions.

Furthermore, deep learning techniques are also incorporated into the analysis, including RNN [

20], GRU [

21], MLP [

22], and LSTM [

23,

24]. These models are inherently more complex than traditional machine learning algorithms, as they are designed to automatically learn and extract features from unstructured data, such as time-series or sequential data. Their architecture allows them to recognize patterns across time steps, making them particularly well-suited for tasks that require temporal dynamics, such as predicting trends in financial markets, understanding user behavior over time, or forecasting demand in supply chain management. The recurrent nature of RNNs allows them to maintain a memory of previous inputs, enabling the model to make more informed predictions based on past information. However, due to issues such as vanishing gradients, GRU and LSTM were developed as advanced variants to overcome these limitations by introducing gating mechanisms that better control the flow of information through the network. These gated units are crucial for enabling the model to focus on relevant time steps, filtering out irrelevant information and thereby improving prediction accuracy.

In particular, LSTMs are highly effective in managing long-range dependencies within sequential data, offering a distinct advantage over traditional RNNs in applications that require the retention of information across extended sequences. This makes LSTMs particularly suitable for complex tasks such as speech recognition, language translation, and time-series forecasting, where the relationships between data points may span long intervals. GRUs offer a more streamlined architecture than LSTMs, reducing computational complexity while still retaining the ability to capture temporal dependencies. This makes GRUs an attractive option for scenarios where computational efficiency is critical, yet the task still demands the ability to model sequential dependencies with high accuracy.

MLP, though not explicitly designed for sequential data, provide a versatile framework for handling both regression and classification tasks. As a feedforward neural network, the MLP operates by passing information through multiple layers of interconnected nodes, allowing the network to learn hierarchical representations of the data. This approach is particularly powerful when working with high-dimensional datasets, as it enables the model to discover complex relationships between input features and target variables. While MLPs are often used for structured data, they can also be applied to unstructured data, particularly when combined with other models or used as part of a larger ensemble. The deep learning models, with their capacity to process vast amounts of data and their ability to automatically learn complex feature representations, significantly enhance the accuracy and robustness of the predictions generated in this study. By capturing intricate patterns that might be overlooked by traditional machine learning algorithms, these models contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the data, ultimately leading to more reliable and informed decision-making processes. The combination of both machine learning and deep learning methodologies thus provides a comprehensive toolkit for tackling the challenges presented by complex datasets, ensuring that the models developed in this study are both flexible and capable of delivering high-performance predictions across a variety of applications. A more comprehensive analysis and explanation of the previously discussed machine learning and deep learning models will now be presented, providing deeper insights into their respective functionalities and applications.

3.1. Support Vector Regression (SVR)

The SVR model [

11] works by constructing a linear function in a high-dimensional feature space to capture the relationship between input features and the target variable. For a set of training data {(x

1,y

1),(x

2,y

2),…,(x

n,y

n)}, where x

i ∈ R

d are the input feature vectors and y

i ∈ R are the corresponding target values, the goal is to find a function f(x) that deviates from the actual target values by no more than ε and is as flat as possible. In its simplest form, the regression function can be expressed as,

where w is the weight vector and b is the bias term. However, not all data points can be perfectly fitted within this margin, so SVR introduces slack variables

and

to account for instances where the prediction error exceeds ε. The optimization problem can then be formulated as,

subject to the constraints:

In this formulation, the term represents the model complexity, or the flatness of the regression function, while the slack variables and account for the errors outside the ε margin. The parameter C controls the trade-off between minimizing the prediction error and maintaining a smooth regression function. A large C value prioritizes minimizing errors, allowing more points to violate the ε margin, whereas a smaller C enforces a smoother model at the cost of higher errors.

3.2. Random Forest (RF)

RF [

16] is an ensemble learning technique that combines multiple decision trees to improve predictive accuracy and reduce overfitting. The algorithm works by generating multiple decision trees during training, with each tree trained on a random subset of the data and a random subset of the input features. The final prediction is made by aggregating the predictions from all the trees, typically through majority voting for classification or averaging for regression. In the case of regression, RF constructs M decision trees, each trained on a different bootstrap sample from the original dataset. The prediction for a given input x is the average of the individual predictions from each tree, expressed as,

where T

m(x) is the prediction of the m-th decision tree for input x, and M is the total number of trees in the forest. Each tree T

m is built by recursively splitting the data to minimize the variance in the output variable, typically using criteria like MSE. The goal of each split is to find the feature and threshold that maximally reduce the variance within each resulting subset, defined as,

where S is the original subset of data before the split, S

1 and S

2 are the resulting subsets after the split, and Var(S) is the variance of the target values in subset S. The algorithm selects the split that maximizes this variance reduction. In addition to bootstrapping, RF introduces randomness by selecting a random subset of features at each split within a tree. This is controlled by a parameter m

try, which specifies the number of features to consider at each node. For regression, this is typically set to

, where p is the total number of features. This random selection ensures that each tree is diverse and not overly dependent on any specific features. Once all trees are trained, the RF model makes its final prediction for a given input x by averaging the predictions of all trees, as shown earlier. This averaging helps reduce the variance of the model and increases its robustness, as the individual errors of the trees tend to cancel each other out.

3.3. Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR)

GBR [

17] is a sophisticated machine learning technique designed to iteratively improve predictive accuracy by combining multiple weak models, typically decision trees, into a strong ensemble model. At its core, GBR seeks to minimize a loss function, such as mean squared error (MSE), which is represented by,

yi represents the actual target value, and

denotes the predicted value. The algorithm initiates with a preliminary prediction, typically defined as the mean of the target value

. Subsequently, it computes the residuals, which are the deviations between the predicted value

and the corresponding actual value

yi, as expressed by the following equation,

In each iteration, GBR fits a weak learner to the residuals, where the weak learners typically consist of shallow decision trees. While these individual weak learners may exhibit a propensity for underfitting when considered in isolation, their sequential combination results in a significantly more robust predictive model. The principal innovation of GBR lies in the application of gradient descent to iteratively minimize the specified loss function. At each iteration, the model computes the gradient of the loss function with respect to the current predictions, expressed as,

is the gradient of the loss function

evaluated at the current prediction

. A new weak learner is then fitted to approximate this gradient, and the model is updated by incorporating the predictions of the weak learner, scaled by a learning rate α, which modulates the contribution of each learner to the overall model. The updated prediction at iteration

m+1 is given by,

where

hm(

x) denotes the weak learner trained on the residuals. This process is iteratively repeated over a pre-defined number of iterations, progressively refining the accuracy of the model by minimizing the residual errors. After

M iterations, the final model is represented as the cumulative sum of the initial prediction and the contributions of all weak learners, formulated as,

3.4. K-nearest Neighbors (KNN)

KNN [

18] is a simple yet effective machine learning algorithm used for both classification and regression tasks. In the context of regression, KNN operates by identifying the kkk-nearest data points in the training set to a given query point and then predicting the target value based on the average of these neighbors. The core idea behind KNN is that similar instances are likely to have similar outcomes, making it a non-parametric method that does not assume any prior distribution of the data. In KNN, the first step is to define a distance metric to measure the similarity between data points. The most commonly used metric is the Euclidean distance, which for two data points x

i and x

j in a d-dimensional space is given by,

This formula computes the square root of the sum of squared differences between the corresponding features of the two points. Once the distance is calculated for all points in the training set relative to the query point, the algorithm selects the k-nearest neighbors, where k is a predefined integer. For KNN regression, the prediction is made by averaging the target values of these k-nearest neighbors. If the target values of the k-nearest neighbors are denoted by y

1,y

2,…,y

k, the predicted value

for the query point is computed as,

This simple averaging method ensures that the prediction reflects the local neighborhood of the query point. Alternatively, a weighted version of KNN can be used, where closer neighbors contribute more to the prediction than those further away. In such cases, the weights are inversely proportional to the distance between the query point and its neighbors. The weighted prediction is computed as,

where

is the weight assigned to the i-th neighbor based on its distance to the query point. This approach improves accuracy in situations where nearer neighbors are more likely to have similar target values.

3.5. Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR)

KRR [

19] is an extension of ridge regression that incorporates the power of kernel methods, enabling it to handle non-linear relationships between features and target variables. Like standard ridge regression, KRR aims to minimize a penalized sum of squared errors, balancing the trade-off between fitting the data well and preventing overfitting by controlling the magnitude of the coefficients. The ridge regression problem is formulated as,

where y

i represents the target values, x

i the feature vectors, w the coefficients, and λ is the regularization parameter that discourages large coefficients and controls overfitting. While this works well for linear problems, it is insufficient for non-linear data, where a simple linear model cannot capture complex patterns. This is where Kernel Ridge Regression comes into play by mapping the data into a higher-dimensional feature space using a kernel function, allowing the model to fit non-linear relationships. In KRR, instead of solving the regression problem in the original feature space, we utilize a kernel function K(x

i,x

j), which computes the similarity between data points x

i and x

j without explicitly performing the high-dimensional mapping. One popular kernel used in KRR is the radial basis function kernel, which is defined as,

This kernel function measures the similarity between two data points based on their Euclidean distance, and the parameter σ controls the width of the Gaussian function, dictating how much influence each data point has in the higher-dimensional space. The use of kernels transforms the original regression problem into one that can be solved in the kernel space, leading to the following solution in the dual form. The solution for the regression problem in KRR can be written as,

where

represents the vector of dual coefficients, K is the kernel matrix with entries K(x

i,x

j), λ is the regularization parameter, I is the identity matrix, and y is the vector of target values. Once

is computed, predictions for a new data point x are made by evaluating the weighted sum of the kernel functions between the new data point and the training data points,

This formulation shows that the prediction for x depends on how similar it is to the training points, weighted by the coefficients , which were learned during the training process. The regularization parameter λ helps control the complexity of the model by preventing the kernel matrix from overfitting the training data. A larger λ results in a smoother, more generalized model, while a smaller λ allows the model to fit the data more closely.

3.6. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN)

RNN [

20] is a type of neural network architecture specifically designed for handling sequential data by allowing connections between units to form directed cycles, which introduces the concept of memory in the network. Unlike traditional feed forward neural networks, RNNs maintain a hidden state that is passed from one time step to the next, enabling them to capture temporal dependencies in data. At each time step

t, the RNN takes an input

xt, updates its hidden state

ht, and generates an output

yt, where the hidden state is influenced by both the current input and the hidden state from the previous time step. The fundamental equations governing an RNN are,

ht is the hidden state at time step t, Wh, Wx, and Wy are the weight matrices corresponding to the hidden state, input, and output, respectively, and bh and by are the bias terms. The non-linear activation function tanh is often used to introduce non-linearity into the network. The hidden state ht captures the information from both the current input xt and the past hidden state ht-1, thereby allowing the RNN to retain memory over time. The output yt is typically a linear transformation of the hidden state, followed by a non-linear activation function depending on the task.

For sequences, the RNN processes inputs sequentially, updating the hidden state at each time step, which allows it to learn patterns across time steps. The hidden state at time ttt not only depends on the input at that particular step but also on the entire history of previous inputs, thus allowing RNNs to capture long-term dependencies. This recurrence is what gives RNN their power for tasks like time-series prediction, natural language processing, and speech recognition.

3.7. Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)

A GRU [

21] is designed to handle sequential data by maintaining a hidden state that captures dependencies over time. It uses two main gates: the reset gate and the update gate, both of which control how information flows through the network and updates the hidden state. The update gate

zt controls the degree to which the previous hidden state

ht−1 influences the current hidden state

ht. It is computed as,

where W

z and U

z are weight matrices, x

t is the input at time step t, and σ represents the sigmoid function. The reset gate r

t determines how much of the previous hidden state should be ignored when computing the candidate hidden state. It is calculated as,

Using the reset gate, the candidate hidden state

is formed, which incorporates the influence of the input and selectively includes information from the past,

Finally, the new hidden state

ht is updated by blending the previous hidden state

ht−1 and the candidate hidden state

, weighted by the update gate,

This mechanism allows the GRU to maintain relevant information over time while effectively discarding unnecessary details, ensuring that the model can capture both short- and long-term dependencies in the data.

3.8. Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)

A MLP [

22] is a type of artificial neural network composed of at least three layers: an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. Each layer consists of multiple nodes or neurons, where each neuron applies a weighted sum of its inputs followed by a nonlinear activation function. The mathematical model for a single neuron can be represented as,

where w

i represents the weights, x

i are the input features, and b is the bias term. The output of the neuron is passed through an activation function σ(z), commonly a sigmoid, rectified linear unit, or hyperbolic tangent function,

For the entire MLP, the forward propagation of inputs through multiple layers follows this process, and the network learns by adjusting the weights and biases through backpropagation. The goal is to minimize the loss function

, where

y is the true label and

is the predicted label, using gradient descent,

where

η is the learning rate. Through iterative training, the MLP optimizes its parameters to perform tasks like classification or regression.

3.9. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

LSTM [

23,

24] is an architecture specifically designed to address the vanishing gradient problem, which poses significant challenges when models attempt to learn long-term dependencies. LSTMs use memory cells that maintain their state over time and are regulated by three gates: input, forget, and output gates. The memory cell

ct is updated as follows,

where

ct−1 is the previous cell state,

is the candidate cell state,

it is the input gate, and

ft is the forget gate. The input gate

it, forget gate

ft, and output gate

ot are defined as:

xt represents the input at time step

t,

ht−1 is the hidden state from the previous time step, and

σ is the sigmoid function. The candidate cell state

is computed as,

Finally, the hidden state

ht is updated based on the output gate and the new cell state,

4. Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Model for FOWLP

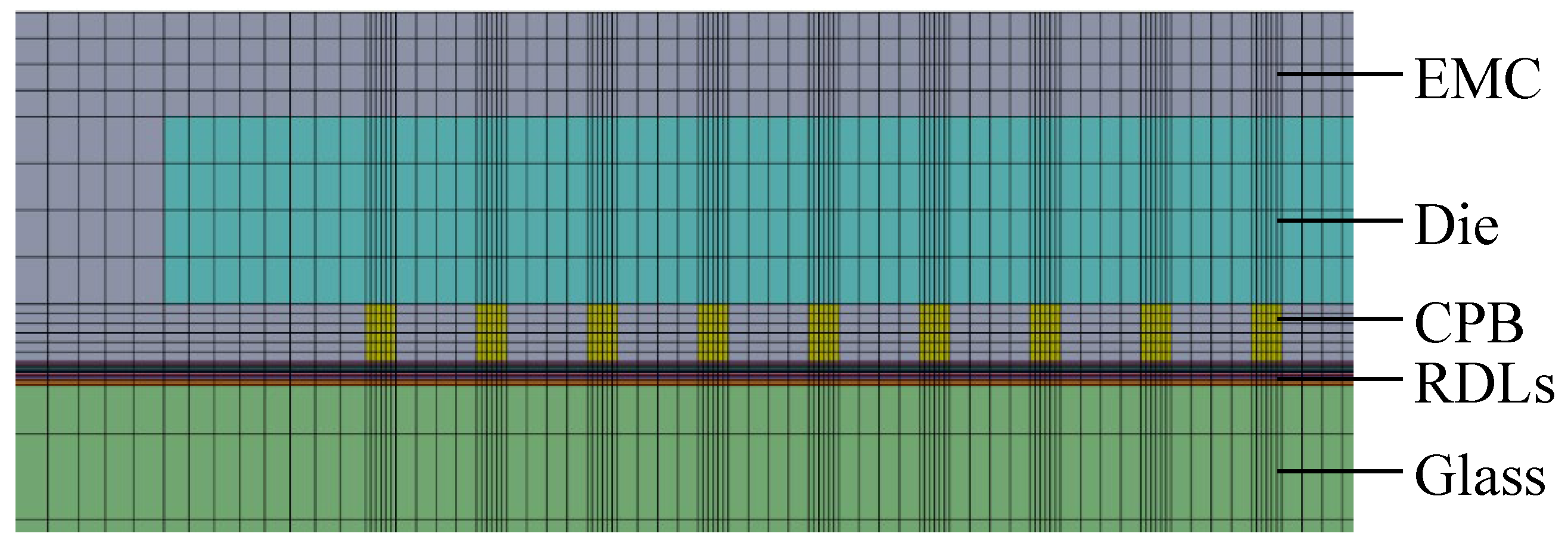

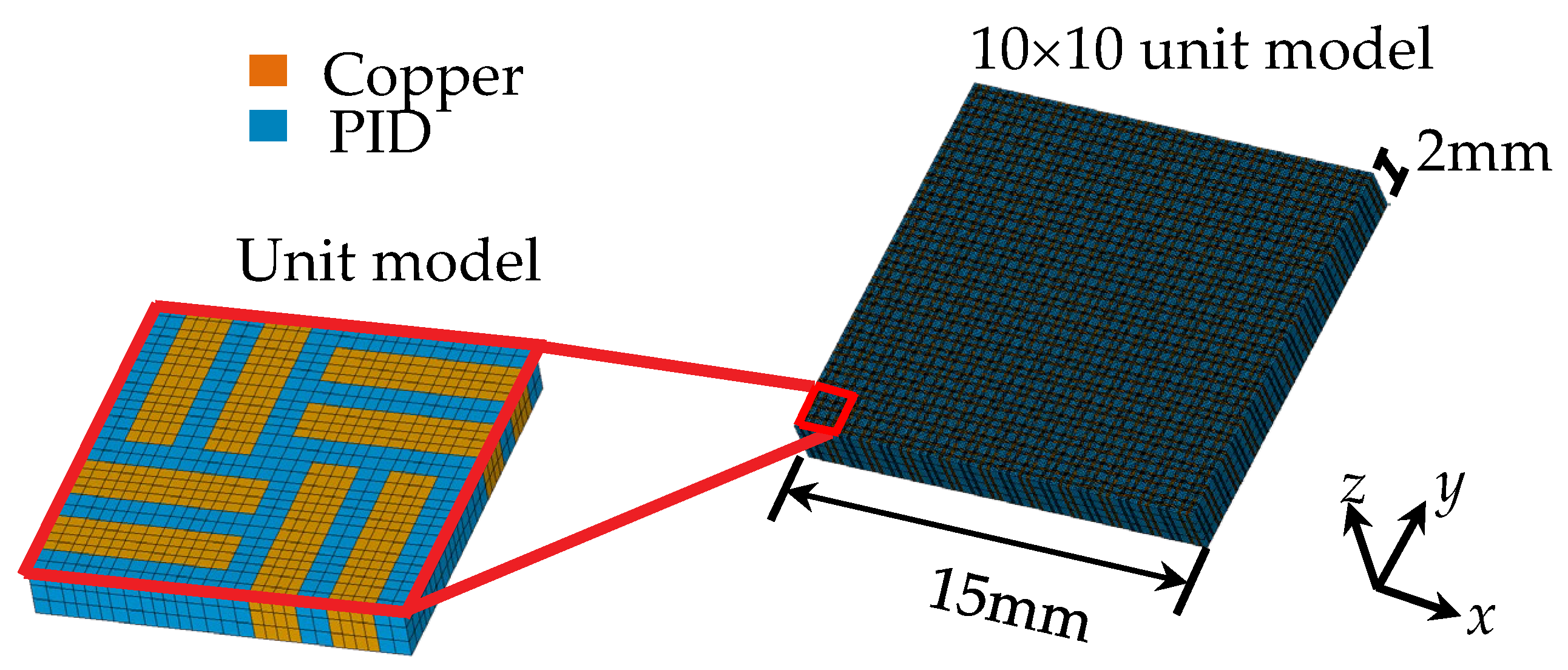

A comprehensive FEA model has been developed, incorporating the ANSYS element birth and death technique alongside nonlinear FEA, to provide an accurate assessment of the warpage behavior observed in FOWLP during its fabrication process. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the model represents a fully three-dimensional simulation of the FOWLP structure. In order to eliminate the possibility of rigid body motion, the displacement of the nodes located at the center of the bottom surface of the glass carrier is constrained. The detailed composition of the FEA model, depicted in

Figure 3, includes critical components such as RDLs, EMC, CPBs, silicon dies, and the glass carrier. The mesh is constructed using hexahedral solid elements (ANSYS SOLID185), resulting in approximately 457,272 elements and 498,726 nodes in total for the entire FOWLP structure, ensuring a high level of precision in the warpage simulation.

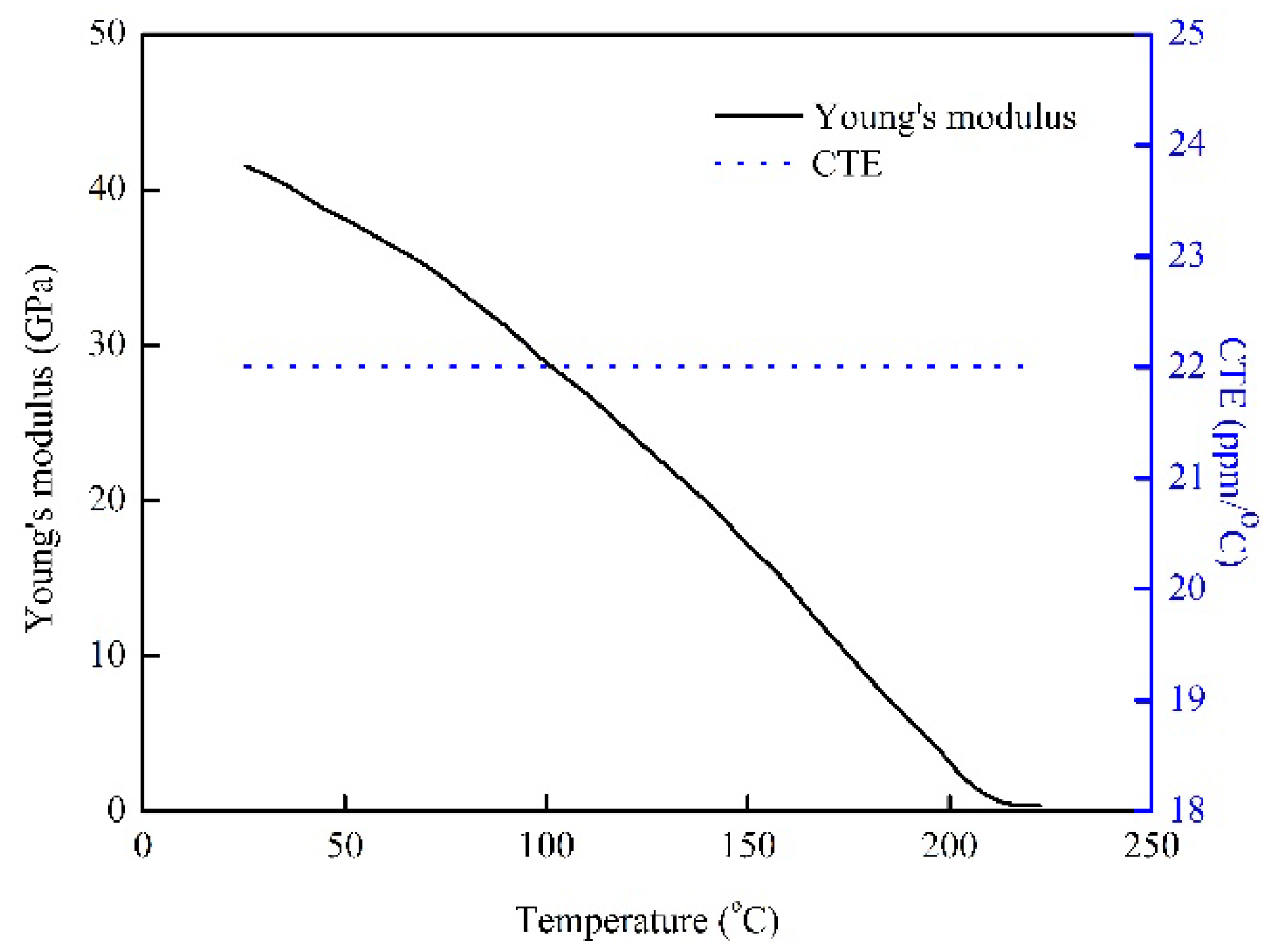

Table 1 shows the material properties of the WLP model. It is crucial to highlight that all materials, with the exception of the solder balls, exhibit linear behavior and are not influenced by temperature variations. The material properties of the SAC 305 solder balls, on the other hand, demonstrate nonlinear behavior and are highly dependent on temperature, as shown in

Figure 4 [

27]. While the EMC is modeled as a linearly viscoelastic material, all other materials are treated as linearly elastic, isotropic, and temperature-dependent, thereby ensuring an accurate representation of their mechanical response in the simulation.

EMC materials are critical in determining the thermal-mechanical performance of electronic packaging systems [

28]. These materials typically exhibit viscoelastic characteristics that are influenced by temperature, time, and strain rate, leading to complex behaviors such as creep, stress relaxation, and hysteresis. The viscoelastic relaxation behavior of EMC materials is commonly modeled using a generalized Maxwell framework, which consists of multiple Maxwell elements and an independent spring arranged in parallel. This approach effectively captures the relaxation dynamics and is frequently represented through a Prony series expansion in frequency domain, which provides an accurate fit to experimental relaxation data.

E(ω) denotes the relaxation modulus of the entire model, gi the weight factor of the ith Maxwell element, the long-term fully relaxed weight factor, ω the frequency, τi the relaxation time, and N the total number of Maxwell elements.

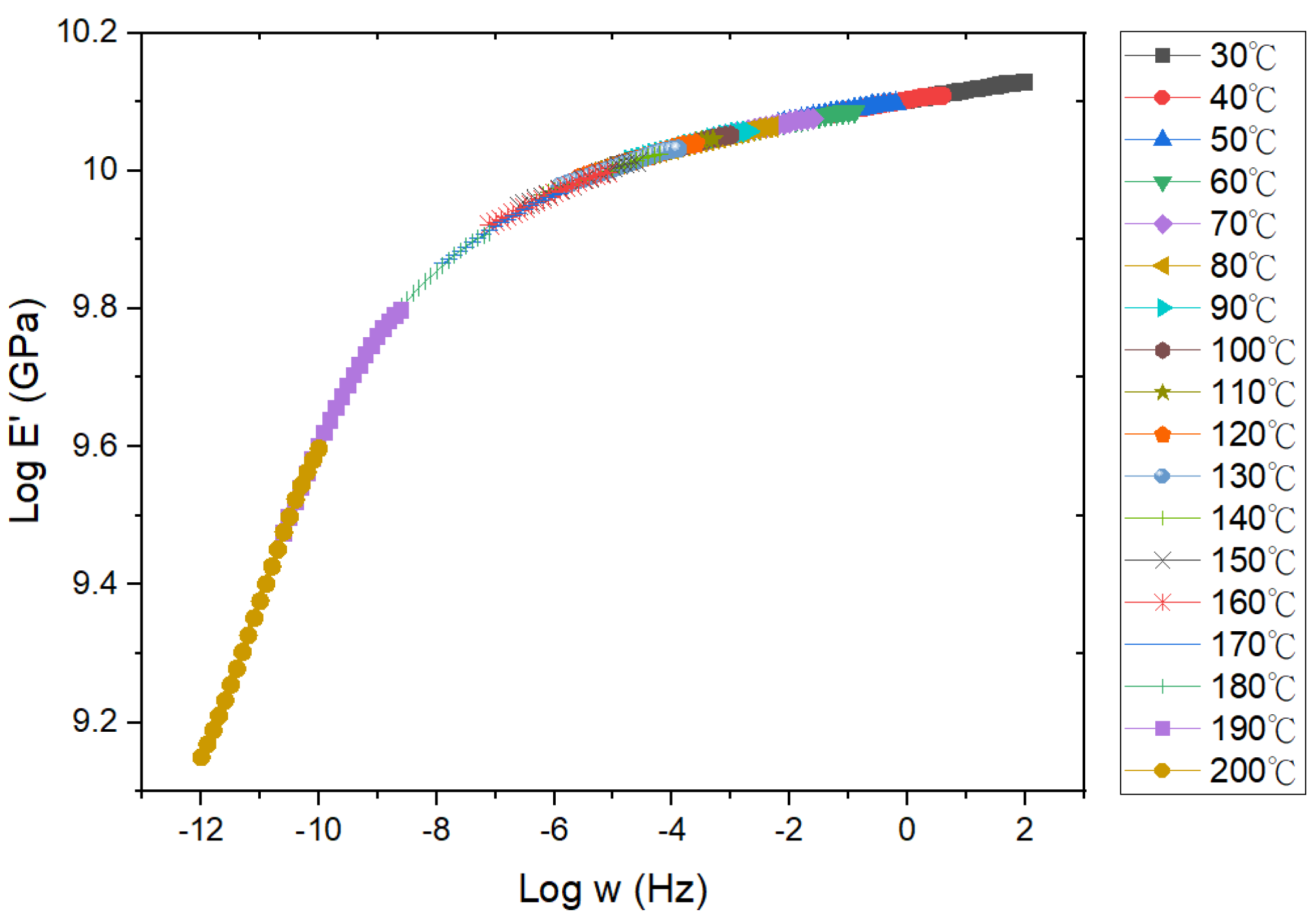

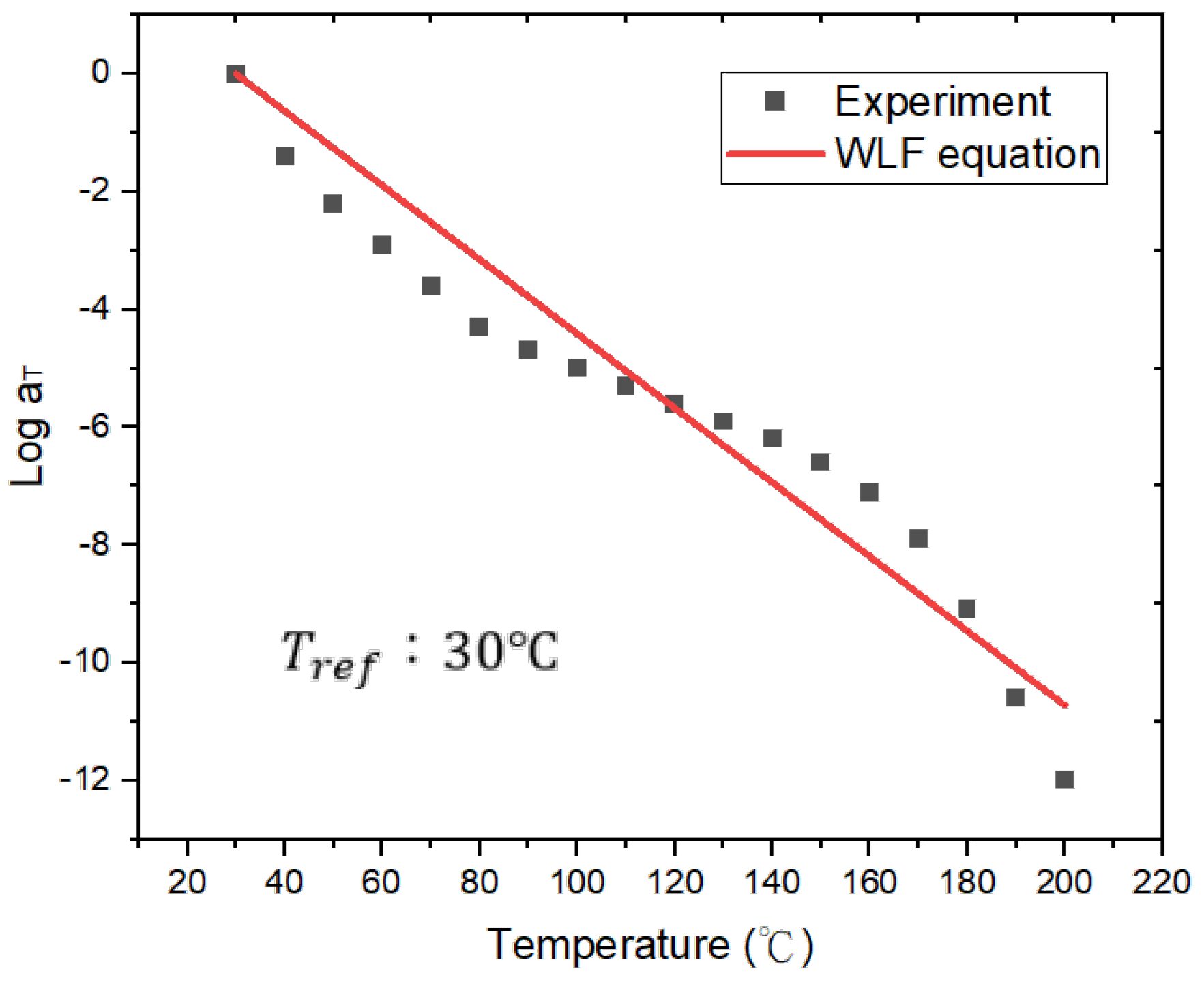

The time and temperature dependence of the mechanical properties of a viscoelastic material can be correlated using the time–temperature superposition principle (TTSP). More specifically, the TTSP suggests that a relaxation curve of a viscoelastic material at a specific temperature can be employed as a reference for further characterizing the relaxation curves at other temperatures by conducting a horizontal translation of the reference relaxation curve in the logarithmic time domain. The temperature translation factor

λT is normally approximated using an empirical relationship, the so-called Williams–Landel–Ferry (WLF) equation,

κ1 and

κ2 are identified as curve-fitting coefficients, with

Tr representing the reference temperature. The master curve of the relaxation modulus at this reference temperature can be derived by shifting the experimentally obtained frequency-dependent storage moduli measured at various temperatures along the time axis, utilizing the temperature-dependent translation factors

λT. Through relaxation modulus data obtained at different isothermal conditions under 1% applied strain [

29], a reference master curve has been constructed at the glass transition temperature of EMC, as depicted in

Figure 5. The coefficients

gi and

τi for the 20-term Prony series model, which are used to fit this master curve, are presented in

Table 2. Moreover, using the shift factor as a temperature function, as illustrated in

Figure 6, the fitted WLF model coefficients,

κ1=6.311×10

7 and

κ2=1.001×10

9, have been determined for the translation factors, providing a temperature-dependent characterization.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Characterization of Process-Induced Warpage of FOWLP

In this study, an experimental approach using the Shadow Moiré measurement technique was meticulously employed to validate and confirm the accuracy of the FEA simulations for FOWLP. This technique, known for its high precision in measuring warpage and deformation, plays a pivotal role in ensuring that the simulation results align closely with real-world experimental outcomes. By leveraging the capabilities of the Shadow Moiré method, the study aimed to provide a robust and reliable validation framework, ensuring the predictive models are not only theoretical but also applicable to practical scenarios in semiconductor packaging.

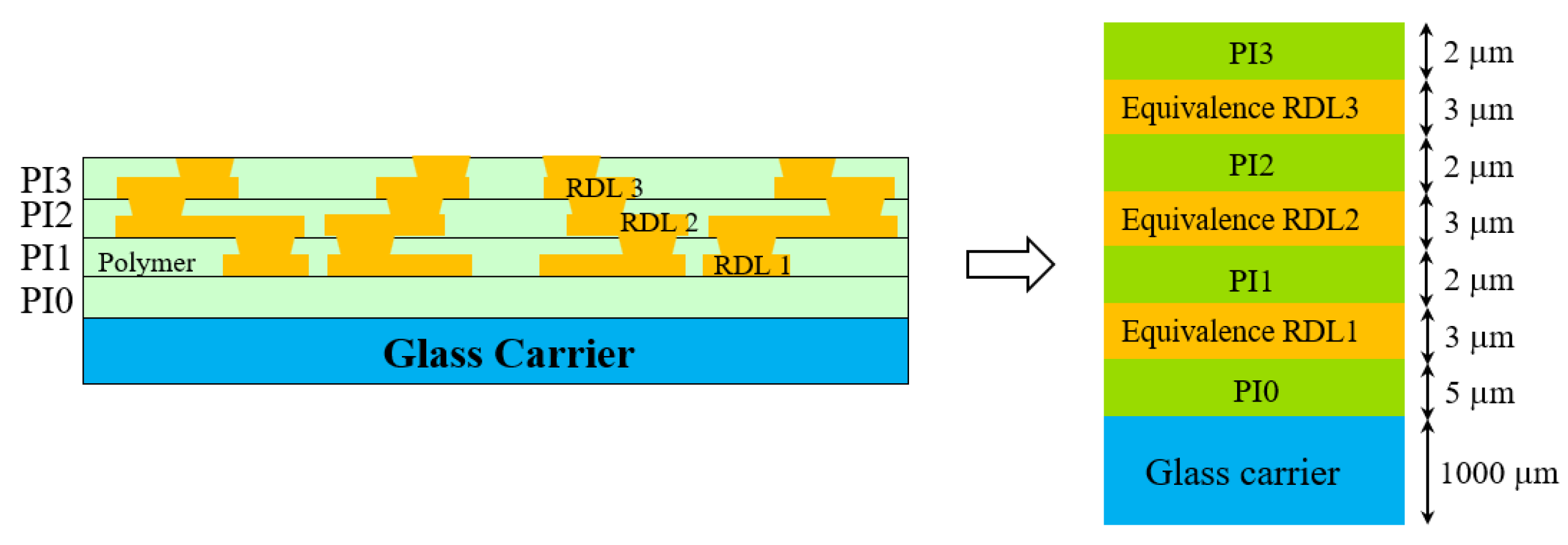

Figure 7, presented in this study, offers a clear schematic representation of the RDLs within the FOWLP structure, a key component that plays a significant role in the overall performance and reliability of these advanced packaging systems. The RDLs serve as essential pathways for electrical connectivity, linking the microchips with external systems. Understanding the behavior of these layers under thermal and mechanical stress is crucial to the design and development of high-performance FOWLP structures, which are increasingly becoming the standard in modern electronics due to their high density and efficient use of space. The fabrication process for these complex structures begins with the deposition of the PI 0 dielectric layer onto the carrier substrate at a controlled temperature of 210°C, a critical step that ensures the proper insulation and protection of the underlying components. The precise temperature control is essential because any deviations could lead to defects in the dielectric layer, impacting the overall performance of the package. The PI 0 layer serves as the foundational layer, providing the necessary insulation and mechanical support for the subsequent RDLs and dielectric layers that will be added in the later stages of the process.

In the second stage of the fabrication process, the first redistribution layer (RDL 1) is fabricated. This layer forms the initial network of interconnections, establishing the primary pathways for electrical signals within the FOWLP structure. The process of fabricating the RDL involves precise lithography and metallization techniques, which must be executed with high accuracy to ensure the correct alignment and functionality of the interconnections. Once RDL 1 is successfully formed, the process moves to the third stage, where the dielectric layer PI 1 is deposited. This layer serves to insulate the RDL 1 from subsequent redistribution layers, preventing any electrical short circuits and ensuring the structural integrity of the entire package. The steps in stages two and three, specifically the fabrication of the RDLs and dielectric layers, are subsequently repeated twice to complete the formation of the additional layers, namely RDL 2, PI 2, RDL 3, and PI 3. Each repetition of this process is conducted with extreme precision, as the accuracy and performance of the final FOWLP structure depend heavily on the correct fabrication of each layer. The RDLs must be perfectly aligned, and the dielectric layers must provide effective insulation without introducing any mechanical stress or defects that could affect the warpage behavior of the package. By repeating these steps, the multilayered structure of the FOWLP is built, with each layer contributing to the overall electrical and mechanical performance of the system.

Moreover, the repeated fabrication process, involving multiple RDL and dielectric layers, introduces additional complexity in terms of thermal management and mechanical stability. Each layer, especially the redistribution layers, contributes to the overall thermal expansion characteristics of the package, which in turn influences the warpage behavior during thermal cycling. The Shadow Moiré technique was particularly useful in capturing these subtle deformations, providing detailed insights into how each layer affects the overall warpage of the structure. By correlating the experimental data with the FEA simulations, the study was able to refine the predictive models, ensuring that they accurately represent the real-world behavior of FOWLP structures under varying conditions. The combination of advanced fabrication techniques, precise measurement methods like Shadow Moiré, and sophisticated FEA simulations provides a comprehensive approach to understanding and mitigating warpage in FOWLP. This detailed understanding is critical for the development of reliable and efficient semiconductor packaging solutions that meet the demands of modern electronics, where performance, miniaturization, and reliability are paramount.

Due to the inherent scale mismatch between the intricate and smaller features of the RDL pattern and the significantly larger 12-inch wafer, it becomes clear that utilizing a conventional direct modeling approach for FEA simulations is not practical. The vast difference in scale leads to computational challenges, as accurately representing every detail of the RDL pattern within the full-scale wafer model would result in an excessively large computational burden and unmanageable simulation times. Therefore, The FEA utilizing a detailed fine mesh model can be directly applied to determine the effective orthotropic elastic properties of Cu circuit layers. This approach is particularly effective in capturing the critical parameters that influence these effective properties with high accuracy. However, it involves a highly intricate, time-intensive, and complex process for modeling and simulating the material behavior [

30]. This methodology is succinctly referred to as the FEA-based effective approach [

31]. The fundamental concept of this approach is to ensure that the elastic responses of the homogeneous equivalent continuum are in alignment with those of the original heterogeneous medium.

Figure 8 depicts the model used in this study for the evaluation of equivalent material properties.

The effective CTEs of the Cu circuit layers could be simply calculated based on the strength of the materials,

where

δi is the thermal deformation,

αi (

i =

x,

y,

z) stands for the effective CTE in the

i-th direction, ∆

T denotes the temperature increment, and

Li represents the side length of the Cu circuit layers in the

i-th direction.

In accordance with the generalized Hooke’s law, the stress-strain relationship of an orthotropic material is expressed as,

where

ε(

εx,

εy,

εz) and

σ(

σx,

σy,

σz) are the normal strain and stress, respectively,

γ(

γxy,

γyz,

γzx) and

τ(

τxy,

τyz,

τzx) represent the shear strain and stress, respectively, and

υ(

υxy,

υyz,

υzx) denotes the Poisson’s ratio. In total, there are nine independent effective elastic constants to be determined for an orthotropic elastic material, which are

Ex,

Ey,

Ez,

υxy,

υyz,

υzx,

Gxy,

Gyz, and

Gxz. These constants can be simply derived based on Equations (38)–(43) through FEAs with a set of different loading and boundary conditions. The rest of the effective elastic constants

υxy,

υyz,

υzx can be readily derived from the fact that the compliance matrix is symmetric.

Table 3 presents the material properties of the RDLs. The effective material properties are calculated based on the equations mentioned above. The Cu volume fraction is approximately 24.9% in RDL1, 35.7% in RDL2, 40.2% in RDL3, and 23.5% in RDL4. This effective material approach not only simplifies the FEA simulation but also provides a more accurate representation of the mechanical behavior of the RDLs at the wafer scale. Without this approach, the simulation would either be too computationally expensive to be feasible or too simplified to yield meaningful results. By integrating the FEA-based effective approach, the study ensures that the essential mechanical properties of the RDLs are accurately captured, enabling precise predictions of warpage and other thermomechanical effects in the FOWLP structure. The combination of in-plane and out-of-plane CTE calculations allows for a comprehensive understanding of the thermal behavior of the RDLs, contributing to the overall accuracy of the simulation. Ultimately, this approach underscores the importance of balancing computational efficiency with the need for accuracy in FEA simulations, particularly when dealing with complex multi-material systems like FOWLP. Through the use of effective material properties, the study is able to overcome the challenges posed by the scale mismatch between the RDL pattern and the 12-inch wafer, ensuring that the simulation results remain reliable and relevant to real-world applications in semiconductor packaging.

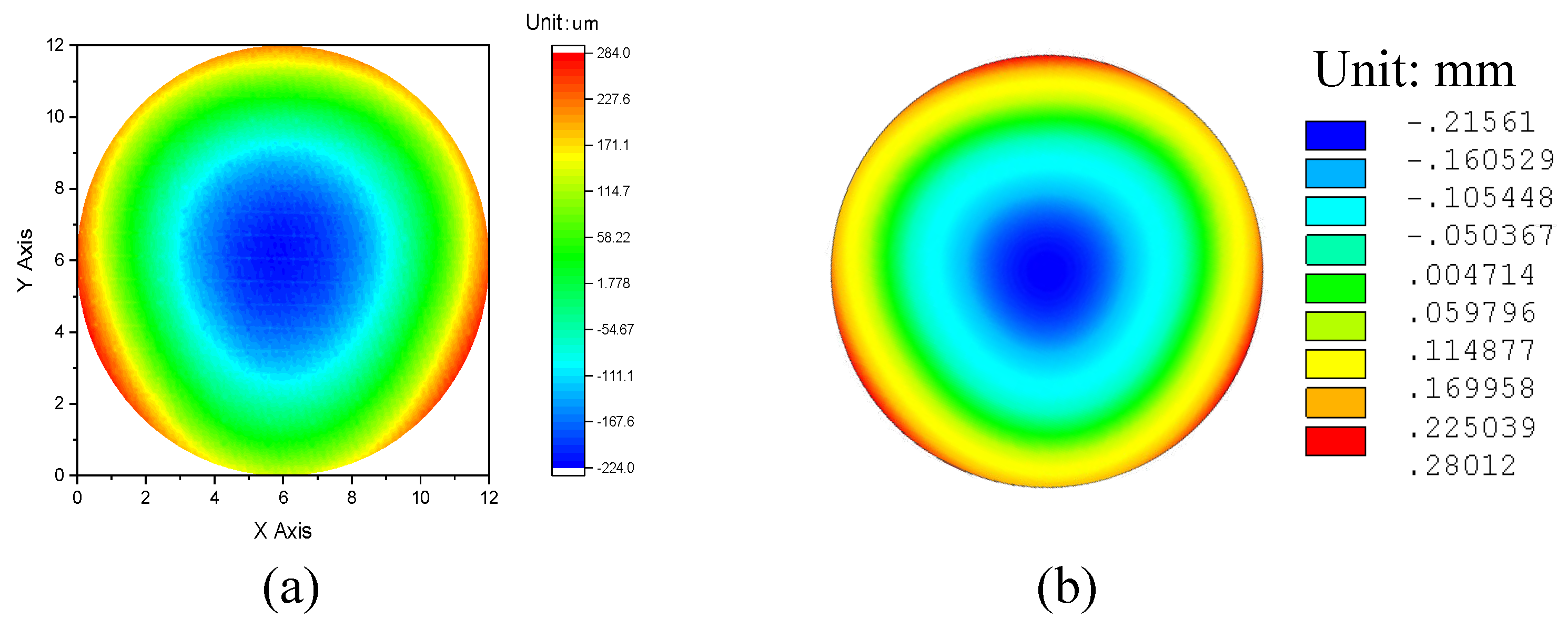

The warpage analysis results, obtained through both experimental measurements and FEA simulations, are presented in

Figure 9 for a detailed comparison. These results are critical for understanding the complex thermomechanical behavior that occurs during the RDL fabrication process, a key stage in the production of FOWLP structures. Specifically,

Figure 9 (a) displays the experimentally measured warpage after the entire RDL fabrication process has been completed, showcasing the actual physical deformation of the structure. On the other hand,

Figure 9 (b) illustrates the corresponding warpage as predicted by the FEA simulations, providing a theoretical representation of the same deformation based on the assumptions of the model and the material properties used in the simulation. Warpage refers to the differential deformation experienced by the structure along the

z-axis, which is the vertical direction perpendicular to the wafer plane. Warpage is quantified as the difference between the maximum and minimum displacement values across the surface of the wafer, effectively measuring how much the structure bends or deforms due to thermal or mechanical stress. This deformation can be caused by several factors, including the differing CTE between the various materials used in the packaging, as well as the internal stresses that develop during the RDL fabrication process.

The comparison between the experimental measurements and the simulated results reveals a high degree of correlation, which is crucial in validating the accuracy and reliability of the FEA model employed in this study. Such validation is essential for ensuring that the simulation can be trusted to predict real-world outcomes, which is particularly important when designing and optimizing semiconductor packaging technologies. According to the results, the experimentally measured warpage reached a value of 506.6 μm, while the simulated warpage value was 495.7 μm. This minimal deviation of only 10.9 μm between the experimental and simulated values demonstrates a remarkably close agreement, underscoring the precision of the FEA model used in this analysis. This small discrepancy between the measured and simulated warpage can be attributed to several factors, including slight variations in material properties, process conditions, or the inherent limitations of experimental measurement techniques. Nonetheless, the close alignment between these two values highlights the robustness and reliability of the FEA approach, confirming that the model is capable of accurately capturing the key physical phenomena that occur during the RDL fabrication process. The ability of the FEA model to predict warpage with such a high degree of accuracy is particularly noteworthy given the inclusion of the viscoelastic properties of the EMC in the simulation. Viscoelastic materials, such as the EMC, exhibit both elastic and time-dependent viscous behavior, making their mechanical response more complex than purely elastic materials. By accounting for these viscoelastic properties in the simulation, the model is able to more accurately reflect the real-world behavior of the FOWLP structure under thermal cycling conditions.

The close congruence between the experimental and simulated results serves as strong evidence of the accuracy and robustness of the proposed process modeling methodology for predicting warpage. This high level of agreement between the two sets of data not only validates the effectiveness of the FEA framework in capturing the complex thermomechanical behavior of the system but also emphasizes the capability of the model to provide reliable predictions of warpage under practical manufacturing conditions. In other words, the FEA-based approach proves to be a highly effective tool for understanding and predicting the deformation behavior of FOWLP structures during the critical RDL fabrication process, which is essential for optimizing these structures to minimize undesirable warpage. Moreover, the successful validation of the FEA model in this study paves the way for its future application in optimizing packaging designs to minimize thermally induced warpage in advanced electronic systems. By providing a reliable and accurate tool for predicting warpage, this methodology enables engineers and designers to test various design configurations and material choices in a virtual environment before implementing them in actual manufacturing processes. This ability to simulate and predict warpage behavior in advance allows for more efficient and cost-effective design optimization, reducing the risk of failures and defects in the final product. Furthermore, the accuracy of the FEA model, as thoroughly validated through the comparison with experimental data, lays a strong foundation for the development of an AI-based predictive platform for warpage analysis. The data derived from the FEA simulations, having been confirmed to be accurate and reliable, will serve as a highly credible and robust dataset for training and validating the AI model. The integration of FEA-derived data into the AI platform will significantly enhance the precision and reliability of the AI predictions, ensuring that the platform can provide accurate and trustworthy results in real-world applications.

The use of AI in warpage prediction offers several advantages, including the ability to quickly analyze large datasets and identify complex patterns that may not be immediately apparent through traditional methods. By leveraging machine learning algorithms, the AI platform can learn from the FEA data and improve its predictive capabilities over time, becoming more accurate and efficient with each iteration. This integration of FEA and AI will facilitate more effective optimization and control of warpage in future packaging technologies, allowing for faster and more reliable design iterations. In practical terms, this AI-based predictive platform could be used to simulate the effects of various design parameters, such as material properties, layer thicknesses, and process conditions, on the warpage behavior of FOWLP structures. By providing accurate predictions of how these factors will influence warpage, the platform will enable engineers to make informed decisions during the design phase, ultimately leading to more robust and reliable packaging solutions. This will be particularly valuable in the development of next-generation electronic systems, where the demand for smaller, faster, and more efficient devices requires increasingly complex packaging designs with tight tolerances for warpage and other mechanical deformations. In conclusion, the results of this study firmly establish the credibility and effectiveness of the FEA-based approach in predicting warpage phenomena during the RDL fabrication process. The close agreement between the experimental measurements and the FEA simulations underscores the accuracy and robustness of the model, while the inclusion of viscoelastic properties further enhances its predictive capabilities. The successful validation of the FEA model not only demonstrates its usefulness in current packaging design optimization efforts but also lays the groundwork for the development of an AI-based predictive platform, which will enable even more efficient and accurate warpage analysis in the future. Through this integration of FEA and AI, the study contributes to the ongoing advancement of semiconductor packaging technologies, helping to meet the ever-growing demands of the electronics industry for high-performance, reliable, and miniaturized devices.

5.2. Establishment of Training/Test and Validation Datasets

In this study, five critical parameters were meticulously identified as the most influential factors contributing to thermal stress-induced warpage in FOWLP structures. These parameters include the Die/Package area ratio, the die thickness, the EMC thickness, and two key material properties of the EMC: Young’s modulus and the CTE.

Figure 10 provides detailed specifications regarding the die thickness and EMC thickness. Each of these parameters was selected for its substantial impact on the thermomechanical performance of FOWLP structures, particularly under thermal cycling, a prevalent operational stressor in advanced packaging technologies that significantly influences warpage behavior.

To further understand how changes in these five parameters affect warpage, they were systematically incorporated into the development of an AI model designed to predict warpage behavior induced by thermal stress. The AI model, built using FEA-generated data, enables engineers to optimize FOWLP structures by minimizing warpage. The training dataset, consisting of 1200 data points, was created through FEA simulations, each representing a unique combination of the five parameters and corresponding warpage behavior, as detailed in

Table 4. This comprehensive dataset offers a solid foundation for the AI model to accurately predict warpage across various design configurations. Additionally, this study systematically investigates the effects of the Die/Package area ratio, die thickness, EMC thickness, as well as the Young’s modulus and CTE of the EMC on warpage behavior. The Die/Package ratio was varied across 12 distinct percentage values ranging from 10% to 60% to capture a broad spectrum of design possibilities. Similarly, realistic variations in die and EMC thicknesses were examined, as these parameters critically influence the structural integrity and thermal stress response of the package. The mechanical properties of the EMC were evaluated across a range of Young’s modulus values (5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 GPa) and CTE values (5, 7, 10, and 15 ppm), reflecting different material behaviors under thermal stress. By exploring these variations, the study provides insights into the stiffness and thermal expansion behavior of the EMC, which are critical in minimizing warpage. Through the comprehensive simulation process, the generated dataset offers a robust foundation for in-depth analysis and accurate predictions across a wide variety of design configurations. Ultimately, the findings from this study contribute to a deeper understanding of the factors that influence warpage in FOWLP structures and provide valuable guidance for future packaging design, enhancing the reliability and performance of these technologies.

5.3. A Comparison of Prediction Results from Different Learning Models

The SVR model is initialized with a radial basis function (RBF) kernel, commonly used to handle non-linear relationships in data. The parameter C is set to 100, which controls the regularization of the model, with a higher value leading to a smaller margin and less tolerance for misclassification, making it more sensitive to training data. The gamma parameter, set to 0.1, defines the influence range of a training point, where a lower gamma extends the influence farther, and a higher gamma restricts it to nearby points. The epsilon parameter, set to 0.1, specifies the margin of tolerance within which no penalty is applied to errors in the training data. The model is trained on standardized input data, allowing it to make continuous predictions based on normalized features. In the RF model, the n_estimators parameter, set to 100, determines the number of decision trees used in the ensemble. With 100 trees, the model gains robustness and stability by averaging the outputs of multiple trees, reducing overfitting. The random_state parameter is set to 42, ensuring reproducibility by fixing the randomness in the internal processes of the algorithm. These parameters help balance randomness and repeatability while maximizing the predictive power of the model.

The GBR model uses 100 estimators, performing 100 boosting iterations to refine predictions and reduce errors. The learning rate is set to 0.1, controlling the contribution of each tree to the final prediction. The maximum depth of the trees is limited to 3, preventing overfitting, and the random_state parameter is set to 0 for reproducibility. Together, these parameters guide the model in handling bias, variance, and overall accuracy. For the KNN model, n_neighbors=3 specifies that the three closest neighbors will be used for regression. Both the input data and the target variable are normalized during training, and predictions are denormalized back to their original scale after the model completes the prediction process. The KRR model employs an RBF kernel, which captures non-linear relationships by measuring data point similarities based on their distance in feature space. The alpha parameter, set to 1.0, controls the regularization strength, balancing the trade-off between fitting the training data and generalizing to unseen data. A higher alpha increases regularization to reduce overfitting, while a lower alpha allows the model to capture more intricate patterns, potentially at the cost of overfitting. This combination of the RBF kernel and regularization through alpha enables KRR to handle non-linear regression tasks effectively while managing the risk of overfitting.

The input layer of the RNN model accepts a shape of (5, 1), indicating that each sample has five time steps, with each step containing a single feature. In the RNN and LSTM layers, 128 units are used, meaning they maintain 128 hidden units. Both layers use the ReLU activation function, which introduces non-linearity into the model to help it learn complex patterns. The final output layer, named 'output1,' is a single-unit Dense layer, reflecting that the model predicts a single target variable, such as the warpage value. In the RNN model, the SimpleRNNCell, with its 128 units, maintains the hidden state, while in the LSTM model, the LSTM layer processes sequences of data across multiple time steps. Both models are compiled using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, which is suited for gradient-based optimization. The loss function used is MSE, appropriate for regression tasks as it measures the squared differences between predicted and actual values.

Similarly, in the GRU model, the main parameter is the number of units, set to 128, which defines the dimensionality of the output space. The GRU is wrapped in a Bidirectional layer, which processes the input sequence both forward and backward, allowing the model to capture information from past and future time steps. The MLP model is designed with an input layer that accepts five features. It has three Dense layers, each containing 128 neurons, and all using the ReLU activation function. The final output layer is a single neuron for prediction. This model is also compiled using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001, and MSE is used as the loss function. In all these models, normalization is applied to the input data, scaling it based on the mean and standard deviation, ensuring that all features contribute equally. Similarly, the output variable is normalized before training, and the predicted values are denormalized after prediction for better interpretability. All models are trained with 10000 epochs and a batch size of 240, with verbosity turned off during training to minimize console output.