1. Introduction

Historically, industry and research have focused on additive manufacturing (AM) owing to its capacity to realize complex geometries with reduced raw material consumption and shortened production cycles, while simultaneously facilitating weight reduction, lowering production costs, minimizing waste, and accelerating time-to-market. The large-scale implementation to achieve mass production remains limited by quality differences and processing constraints inherent in the process [

1,

2]. Laser-based powder bed fusion of polymers (PBF-LB/P) is a widely used additive manufacturing process that employs a laser to selectively fuse polymer powder particles layer by layer. This technology enables the fabrication of robust prototypes and functional end-use components from polyamides, polycarbonates, polypropylene, and thermoplastic polyurethane, produced as rigid parts with high structural integrity and without the need for supporting structures. By offering greater design freedom than conventional subtractive manufacturing technologies, more efficient material utilization, and shorter lead times, the process opens up new opportunities across aeronautics, automotive, medical devices, and consumer products. Despite its promising prospects, powder bed fusion of polymers continues to face quality challenges, including warpage, coating defects such as part shifting and particle drag, as well as dimensional inconsistencies resulting from the complex interactions between powder behavior, thermal gradients, and the laser–material response. Irregular surface texture, in homogeneously irregular density, and residual stresses are important obstacles to wider application [

3,

4]. The mechanical and plastic characteristics of the components, such as density, hardness, and porosity, are strongly influenced by parameters such as laser power, scanning speed, hatching strategy, enclosure spacing, and temperature, which require fine-tuning to achieve the required size and mechanical characteristics [

5]. Conventional process control strategies rely on large-scale, physics-based simulations or advanced inspection systems; although highly informative, these approaches are computationally intensive and impractical for near-real-time process monitoring and industrial deployment. The resulting bottleneck leads to incoherent production with reduced acceptability. With the advent of artificial intelligence, machine and deep learning approaches, new approaches have been allowed to represent nonlinear quality-versus-process variables associations [

6]. While the literature on laser-based powder bed fusion of metals (PBF-LB/M) demonstrates strong CNN performance for layer-wise defect detection, the polymer domain differs in both sensing modality and defect phenomenology. Consequently, models trained on melt pool images cannot be directly applied to infrared or visible powder bed surface data, necessitating the development of polymer-specific datasets and evaluation protocols [

7,

8]. Recent research synthesizes how artificial intelligence is changing the monitoring and control of AM, but also highlights gaps in open data and reporting standards on powder bed fusion [

9,

10], which prevent consistent comparison. Supervised CNN and regression models are used, while classification is used for the detection and mapping of anomalies. Unsupervised grouping and anomaly detection are used to detect anomalies where labelled information is not available. In reinforcement learning, trial-and-error process control with feedback is used. Closed-loop adaptive quality control offers promise when integrated with ML for multimodal in situ inspection, combining thermal imaging, acoustic monitoring, and optical profiling. However, there is still a gap: current ML and DL solutions are typically data-hungry black boxes, lacking robustness and interpretation. Industrial deployment is hindered by latency, scalability, and domain adaptation issues [

11,

12]. Lightweight, efficient, and widely applicable models with physical knowledge are therefore needed for near-real-time quality assurance. However, most existing approaches continue to struggle with simultaneously achieving high detection accuracy and meeting the stringent latency requirements necessary for real-time industrial deployment.

1.1. Objectives and Contributions

This study addresses the above limitations by integrating deep learning into the quality control of powder bed fusion of polymers. Its main contributions can be summarized as follows:

Comparative Analysis: A comparison of different deep learning algorithms for PBF-LB/P quality control, highlighting their advantages and disadvantages.

Hybrid Strategies: Suggestions for advantageous combinations of different methods.

Defining the roadmap for next-generation AM: In addition to providing a comprehensive overview of the most advanced techniques, this work outlines the future path towards predictive, efficient, and reliable industrial-scale additive manufacturing.

However, further experiments are needed to determine whether these contributions can be generalized to different types of machines and types of polymers.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Additive Manufacturing Process and PBF-LB/P

Additive manufacturing (AM) technologies, particularly powder bed fusion (PBF), have fundamentally transformed both the design of complex geometries and the manufacturing process itself. PBF enables the fabrication of polymer components without the need for supporting structures and demonstrates outstanding capability in processing polyamide (PA12 and PA11), polypropylene (PP), and thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU), even for intricate geometries [

13]. The technology is based on a layer-by-layer approach, where powder particles are selectively sintered by a laser beam following cross-sectional patterns derived from digital models. After each layer is solidified, the build platform is lowered to allow the deposition of a new powder layer. In contrast to PBF-LB/M, where the powder is fully melted, polymer-based PBF operates at lower temperatures that cause the particles to partially fuse rather than completely liquefy. The temperature is typically kept just below the melting point of the material being processed, while the build chamber is heated close to the glass transition temperature to minimize thermal stresses [

14] Furthermore, the morphology and flowability of particles strongly influence the quality of powder spreading and, consequently, the thermal homogeneity of polymer-based PBF. Recent machine learning pipelines using SEM images demonstrate that automated particle shape classification (e.g., YOLO-based) can reveal critical distribution patterns for polymer stability [

15]. Despite these advances, polymer-based PBF remains susceptible to thermally induced defects. One of the most common issues is curling, which is caused by differential thermal gradients and non-uniform cooling. Such distortions can compromise recoating processes and structural performance. The accumulation of residual stresses across successive layers highlights the need for advanced in situ monitoring and control methodologies. Effective thermal management, through stable chamber conditions and controlled cooling cycles, is essential to minimize warping and achieve dimensional accuracy. However, the limited availability of open-access datasets for polymer-based PBF continues to hinder the systematic benchmarking of competing models.

2.2. Deep Learning in Additive Manufacturing

Integrating DL techniques into AM has significantly improved both predictive modelling and real-time defect detection. Unlike manually designed feature-based models, DL-based models automatically extract hierarchical representations from raw sensor outputs and imaging modalities, demonstrating improved accuracy and generalization capabilities [

2].

2.1.1. Supervised CNNs: VGG16, ResNet50, and Xception

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are one of the most significant architectures for feature extraction in computer vision [

16]. Several advanced versions of CNNs have been developed based on this primary architecture, including VGG16 [

17], ResNet50 [

18], and Xception [

19]. These models have demonstrated excellent performance in image classification tasks and have been used productively in AM for in-situ monitoring based on infrared thermal and melt pool imagery. For example, Klamert et al. achieved 99.1% accuracy and a 97.2% F1 score using VGG16 to detect curling defects on thermal recordings in polymer-based PBF [

20]. However, these main accuracies are typically in balanced, carefully selected data sets; multiple-label co-occurrence and class imbalance in real-world occupations degrade generalization and require metrics that go beyond accuracy (e.g., F1 class ROC-AUC) and reliability [

8]. However, practical problems in AM are often due to the lack of available training data and the imbalance of datasets, and high accuracy is usually achieved only with a balanced dataset [

21,

22,

23]. However, these CNN models’ reliance on carefully selected and balanced data sets raises questions about their resilience to industrial noise.

2.1.2. CNN-LSTM Hybrids for Modeling

Research into metal-based PBF processes has demonstrated the effectiveness of LSTM in tracking instabilities caused by spatter formation over extended periods using acoustic signals. These signals correlate with plasma plume dynamics during the melting process; frequencies around 25 kHz, in particular, show a strong correlation with melt pool behavior. Hybrid models achieved 85.08% classification accuracy in spatter detection using acoustic signals, demonstrating the feasibility of low-cost monitoring approaches. [

24]. A CNN-LSTM model was successfully applied for progressive defect detection, and research into acoustic signals based on PBF-LB/M has revealed that LSTMs are effective in tracking instabilities induced by spatter over time [

22]. In polymer-based PBF settings with low signal-to-noise ratios and limited time labels, sequence models should be combined with class balance handling and uncertainty estimation; otherwise, the added latency and training complexity may not be worth the benefits in the field [

25]. Although CNNs excel at spatial pattern recognition, they lack the inherent capability to capture the temporal dependencies that are crucial for process monitoring. To address this, hybrid architectures that combine CNNs with recurrent neural networks (RNNs), specifically long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, have been developed. CNN-LSTM models use CNNs to extract spatial features while using LSTMs to model temporal sequences, enabling the detection of time-evolving anomalies [

26]. Nevertheless, the extent to which CNN-LSTM approaches can be scaled up for long-duration builds involving millions of frames is not yet fully understood.

2.1.3. Generative Models: Autoencoders and GANs

Autoencoders (AEs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs) have emerged as important unsupervised networks for detecting AM anomalies. AEs compress input data into lower-dimensional latent spaces, which are then reconstructed. Any deviations between the original and reconstructed data are highly effective identifiers of anomalies [

27]. Recent work has demonstrated the potential of AE-based networks for detecting metal AM anomalies in images, with reconstruction error rates of 5.2% or less at interface boundaries [

28]. Concurrently, GANs (generator and discriminator networks) serve two purposes: data augmentation and anomaly detection. They have also been used to address the common issue of class imbalance in the production of sensor signals, resulting in increased insensitivity of a classifier [

29,

30]. Extensions of the fundamental GAN construction, for example, those involving three-player GANs with an additional auxiliary classifier alongside the generator and discriminator, have even outperformed traditional oversampling methods such as SMOTE in cases of extreme imbalance [

29]. Although much has been learned from research, the scope of the technique’s real-world application is nevertheless limited due to issues of learning instability, mode collapse, and limited interpretability. These phenomena are particularly prominent when anomalous cases are scarce or inconsistent [

21]. Addressing GAN instability and mode collapse when applied to highly imbalanced defect data is a key area for future research.

2.1.4. Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs)

Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) are a new approach that incorporates governing physical laws, typically expressed as partial differential equations (PDEs), into applications involving heat transfer during the learning process. By incorporating these constraints into the loss function, PINNs significantly reduce reliance on extensive datasets while enhancing the accuracy, generalizability, and interpretability of predictive models [

12]. In AM, there has been an increasing focus on the advantages of PINNs for thermal simulation and process control. Safari et al. demonstrated the application of PINNs to predicting multi-track LPBF temperatures, achieving highly accurate results at a much lower computational cost than conventional finite element methods. In addition to forward simulations, PINNs are well-suited to inverse problems, such as determining process parameters from real-time thermal data. This is a prerequisite for closed-loop control of AM [

31]. Subsequently, A physics-informed machine learning (PIML) model for PBF was introduced by combining PDE-based thermal modelling and data-driven neural networks, resulting in a hybrid model. This approach enabled effective temperature prediction and real-time parameter estimation. The dual-functional model has the potential to optimize polymer-based PBF process parameters through PINNs, whereas traditional thermal models are limited in terms of computation and accuracy [

32]. In addition to academic research, recent studies have examined the potential of combining transfer learning with physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) to estimate melt pool geometry at a significantly lower computational cost [

33]. These approaches suggest the possibility of real-time monitoring and adaptive control in PBF. More broadly, such physics-informed machine learning (PIML) hybrids and PINNs highlight the transformative potential of predictive simulation in additive manufacturing, enabling the solution of inverse problems and advancing closed-loop control by bridging the gap between high-fidelity thermal modelling and real-time process optimization. Yet, the computational overhead of multi-physics PINNs may limit their scalability. This could affect full build-chamber monitoring.

2.3. Challenges and Knowledge Gaps

Although there have been some remarkable advancements, there are still some challenges that prevent the widespread implementation of DL for AM applications.

Limitations of data: A common barrier at the level of large-scale, high-quality labelled data persists, particularly in the case of rare defects. Although generative models and synthetic data augmentation techniques can improve class balance, concerns remain about the validity, representativeness, and generalizability of artificially generated data [

34]. The imbalance between the abundance of normal process data and the scarcity of defect data makes it difficult to train models stably.

Computational Needs: Advanced DL models, such as residual networks (ResNet) and generative adversarial networks (GANs), are computationally expensive, which limits their potential for real-time in-situ control and monitoring in industrial systems [

31]. The trade-off between model intricacy and inference delay poses a significant challenge to scaled deployment.

Deficits in Interpretability: Current DL models are, for the most part, ’black boxes’, making it difficult to extract physically understandable explanations from their predictions. This lack of transparency hinders their adoption in safety-critical applications such as aerospace and healthcare, where explainability and accountability are prerequisites [

35]. Although recent advancements in interpretable machine learning (IML) have begun to address this issue, practical implementation into AM workflows remains limited. Nevertheless, studies have shown that the application of gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) substantially improves the transparency and interpretability of CNN predictions and their underlying results [

20].

Domain Generalization: The performance of DL models deteriorates when tested in unseen domains, including variations in material properties, machine hardware, or processing conditions not observed in the training dataset. Increasing the amount of data or model size does not improve out-of-distribution generalization, suggesting fundamental flaws in current architectures [

36].

Physics-Constrained Limitations: While physics-informed machine learning and, more specifically, PINNs offer a means of offsetting data inadequacy and achieving greater generalizability, they also present new challenges. multi-physics PINN models for thermal field predictions in PBF also exhibit instability during the learning process and require careful balancing between data-driven learning and PDE-constrained modelling. Currently, these challenges, coupled with the high computational overhead for complex geometries, limit the scalability of these models in real-time industrial applications [

32].

To address these challenges, promising research directions include physics-informed learning approaches that incorporate governing equations into the learning process [

31,

32], self-supervised learning to reduce the reliance on labelled data, and domain adaptation methods to enhance process robustness in changing conditions. Furthermore, the development of lightweight, multimodal, and physics-constrained models is rapidly becoming essential for the scalable, explainable, and real-time quality assurance of next-generation AM systems [

34]. A method for working out the balance between how accurate a model is, how easy it is to understand, and how long it takes to run is still needed.

3. Methodology

When applying DL to AM, it is important to pay particular attention to data acquisition and preprocessing, network structure design, and systematic evaluation methods. In this section, we highlight shared routines and distinctive methods among supervised, unsupervised, and physics-informed approaches by combining methodological insights from recent case studies.

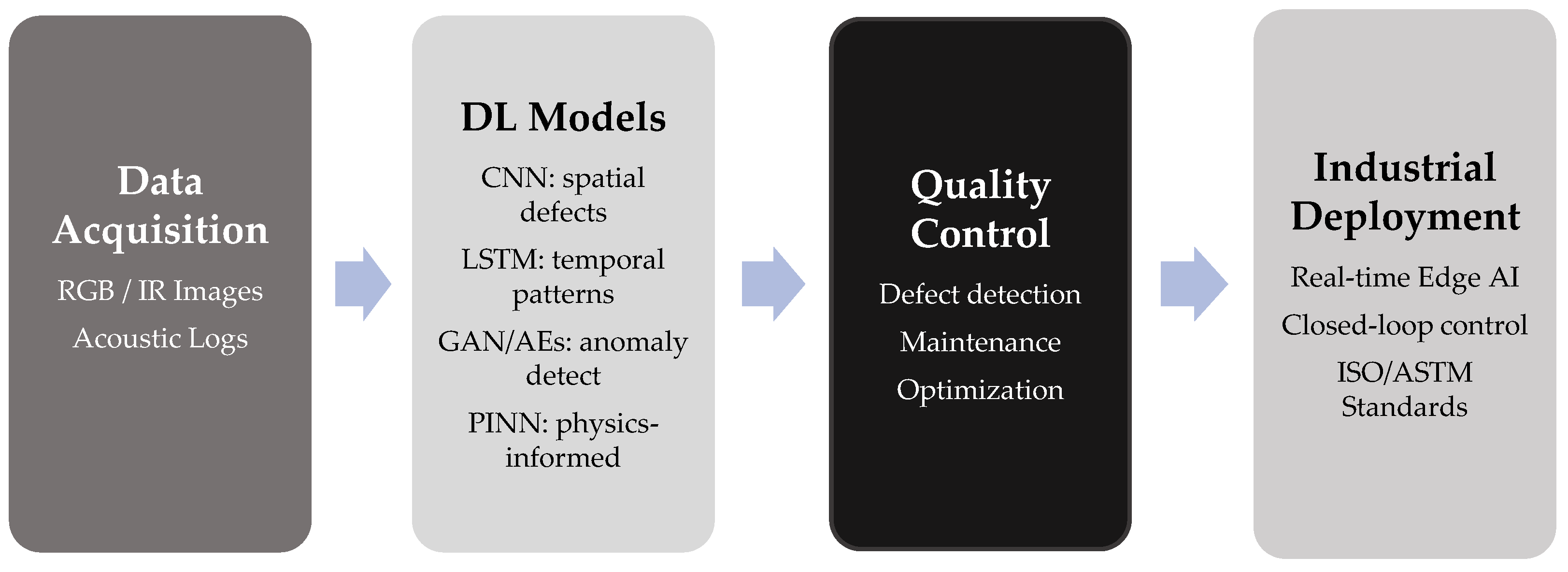

Figure 1.

A conceptual framework that links data acquisition, deep learning architectures, and quality control for the industrial deployment of PBF-LB monitoring systems.

Figure 1.

A conceptual framework that links data acquisition, deep learning architectures, and quality control for the industrial deployment of PBF-LB monitoring systems.

3.1. Data Acquisition and Dataset Preparation

Strong and sturdy datasets form the basis for any successful DL model. In the case of AM, two prominent data modalities come into play: optical/thermal imaging and process sensor logs. High-definition infrared (IR) imaging has proven very useful for capturing thermal dynamics for polymer-based powder bed fusion. For example, a FLIR T420 thermal camera operating at 30 frames per second has been used to generate over 144,000 thermal frames for a single build, capturing layer-wise heating and cooling cycles [

32]. Complete print sequences for CNN–LSTM–based video classification have also been recorded using IR imaging [

22]. Large-scale infrared image datasets of up to 100,000 images have been constructed and grouped into “good” vs. “bad” states based on curling faults [

37]. In these studies, only the collected data were analyzed, while the sensor integration and setup were carried out separately. Furthermore, a low-cost RGB camera solution combined with a custom CNN achieved over 99% accuracy in real-time defect detection for polymer-based PBF-LB/P [

20]. The data preparation typically included layer-specific events (e.g., powder deposit, laser scanning, and cooling) and label assignment subsequently. Supervised labor relied on explicit defect regions annotation, while Esmaeel concentrated on unsupervised anomaly detection, computing feature vectors such as temperature distribution properties for cluster exploration and autoencoder-based reconstruction [

21,

22,

37,

38]. A common challenge for everyone was class imbalance, since defective events are several times less frequent than a regular set of operations. Alleviation techniques included under sampling and oversampling at random [

22], data augmentation [

37], and restricted dataset experiments for model robustness testing. However, the robustness of these datasets is not yet fully validated. This is in terms of varying process conditions and machine vendors. We will adopt best practices reporting on data management (detailed class distribution, leak-free distribution, and multilabel protocols) to mitigate the optimistic bias often observed in AM data sets [

8].

3.1.1. Camera Integration

Camera integration in polymer laser powder bed fusion (PBF-LB-P) has emerged as a viable but technically demanding route for the real-time quality monitoring of laser beams. Low-cost RGB cameras provide effective surface and corrosion control with a moderate integration effort and achieve >99 percent classification accuracy for surface defects when combined with CNNs [

20]. However, thermal field observations and the dynamics of the melting pools require infrared or high-speed pyrometry, which poses problems such as emissivity calibration, complexity of optical pathways, and large amounts of data, which require high-performance computing [

39,

40]. The reviews consistently highlight that the dominant obstacles to camera-based monitoring in industrial polymer systems are optical access limitations, time and spatial resolution trade-offs, and calibration and synchronization with scanning motion [

41]. These limitations are compounded by environmental hazards - dust from gunpowder, reprocessing, and laser interference, which increase the need for maintenance and require protective coverings and periodic recalibration [

42]. Despite these difficulties, the literature shows successful implementation when sensing methods are aligned with the physical defect mechanisms of interest. For example, profilometry was used to quantify the thickness, density, and curl of the polymer PBF with an active feedback for closed-loop control [

42], and off-axis IR thermography correlated the temperature maps at the layer level with the detection of micro-CT defects [

39]. Coaxial two-wavelength pyrometry offers quantitative thermometry of the melting pool, but requires expensive optics and computing infrastructure [

40]. A pragmatic approach recommended by several studies is to start with low-cost RGB monitoring for surface-related coatings, then to gradually integrate profilometry or off-axis IR for thermal analysis in advanced applications, where the cost is justified by the quantitative melt pool data [

43,

44]. Overall, the integration of cameras in the polymer PBF-LB+P system represents a balance between cost, complexity, and monitoring objectives, with algorithmic pre-processing and selective data reduction emerging as key enablers for the practical industrial take-up. However, despite reported achievements, current studies often lack systematic cost-benefit analysis and long-term industrial validation, which limits the transferability of laboratory-based monitoring strategies to robust polymer PBF systems on a production scale.

Table 1.

Summary of camera modalities for polymer PBF-LB/P monitoring.

Table 1.

Summary of camera modalities for polymer PBF-LB/P monitoring.

| Modality |

Typical mount and

access |

What it measures |

Key

advantages |

Key constraints |

Industrial

readiness |

| RGB / off-axis industrial camera [20] |

Fixed internal mount viewing bed after recoating or post-exposure angles; sometimes mounted on recoater or inside the cabinet |

Powder bed surface, coating defects, part outline |

Low cost, whole-bed coverage, effective with CNNs for coating defects |

Cannot see subsurface/thermal signatures; sensitive to lighting and powder glare |

High - already implemented in commercial research setups |

| Off-axis IR thermal camera [39] |

Window/port or dedicated optic with a view of the slice; often off-axis to avoid scanner optics |

Surface/inter pass temperatures and thermal maps of the entire slice |

Wide thermal field maps, layer-wise temperature distribution useful for defect correlation |

Requires calibration, emissivity assumptions; lower spatial resolution than visible cameras |

Medium - feasible, but calibration and cost are barriers |

| Coaxial high-speed pyrometer / two-wavelength camera [40] |

Coaxial or common-optic assembly aligned with process laser or aperture-division optic |

Quantitative melt pool temperature profiles, dynamics at high fps (>10k–30k fps) |

Direct melt pool temperature monitoring and high temporal resolution |

Complex optical integration (coaxial paths), expensive sensors, and HPC for data processing |

Low - technically powerful but costly and not yet widespread in industry |

3.2. Model Architectures and Training Strategies

In AM research, thermal imaging data have been the primary modality for defect detection in PBF-LB/P, and are used to inform the design of model architectures across supervised and unsupervised learning paradigms. Thermal recordings of polymer powder-bed fusion builds are used as the basis for detecting anomalies such as curling, delamination, or coating failures.

Supervised image-based classification has been used extensively with pre-trained CNNs (e.g., VGG16, ResNet50, Xception), with shallower models such as VGG16 showing superior performance (99.1% accuracy, 97.2% F1-score) on thermal datasets [

37], and extended to hybrid CNN–LSTM models to capture spatio-temporal patterns in thermal video sequences, with 97.6% accuracy [

22].

In the Anomaly detection without supervision method, the performance of clustering methods (K-Means, DBSCAN) and deep generative models (autoencoders, GANs) was compared for detecting curling directly from thermal image data of PBF-LB/P builds. Clustering achieved 97% accuracy and semi-supervised hybrids (clustering + deep classification) 99.7%, while unsupervised GAN-based detection was less stable (≈87%) due to reconstruction difficulties in thermal domains [

21].

For Physics-informed modeling, heat-transfer PDEs were embedded into Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs), using thermal measurements from powder-bed builds as supervision and constraints (BCs/ICs and PDE residuals in the loss), yielding physically consistent thermal-field predictions and improved convergence on simplified and real geometries [

32].

In these studies, TensorFlow/PyTorch/Keras were employed and losses specific to the thermal-imaging domain were applied (cross-entropy for CNNs, reconstruction for autoencoders, adversarial for GANs, physics-based residuals for PINNs). However, training was offline, indicating a need for online/adaptive detection. Additional improvements include data-efficiency strategies when thermal recordings are sparse, with recent lines showing training-free segmentation of layer images and layer-wise 3D powder-bed reconstruction as complementary inspection tools without learning weights (e.g., low-cost optical camera + CNN workflows in PBF-LB/P [

20], and a Grab Cut-based, training-free pipeline validated for PBF-LB/M (metals) that reconstructs fused geometries and detects recoater defects [

45].

Together, these advances underline that thermal imaging remains the primary data source for PBF-LB and PBF defect detection, while training-free optical strategies can enhance reliability when data is limited and pave the way for practical online monitoring.

3.3. Evaluation Protocols

Assessment methods included singleton train/test splits, often involving entire print jobs for validation for a test of generalizability. Following the new evaluation guidelines in AMML, we report on individual accuracy, recall, F1 under multiple label imbalances, ROC-AUC, calibration curves, and drift checks between tasks, in accordance with the latest [

25]. Metrics varied by task: Classification models reported accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-scores (Ribeiro: 97.6% accuracy, precision 100%, recall 47.1%; Schmid-Kietreiber: 99.1% accuracy, F1-score 97.2%) [

22,

37]. Anomaly detection approaches assessed reconstruction error and tested clustering validity (Esmaeel: clustering 97%, GAN 87%) [

21]. PINN models were validated using experimental thermal sensor data by adopting RMSE and PDE residual minimization as measures of performance [

32]. Furthermore, interpretability was addressed: Schmid-Kietreiber applied Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) for visualization of salient image regions that influence CNN decisions, allowing necessary transparency for implementation in industry [

37].

3.4. Synthesis

The above-mentioned works demonstrate methodological diversity for DL for AM:

CNNs and CNN–LSTM models dominate supervised defect detection, leveraging large annotated thermal datasets. They provide tenable alternatives in case there are few labels, while stability is a drawback. Physics-informed neural networks hold much promise and combine knowledge from the field by reducing data requirements and preserving physical believability.

Simultaneously, the methods reveal the potential of DL for quality control in AM while also echoing persistent challenges, that is, dataset imbalance, instability in the GAN algorithm, and computer resource needs for real-time applications. Still, the lack of standardized evaluation benchmarks complicates cross-study comparability, which is a problem that must be addressed.

4. Comparative Results

Deep learning has demonstrated significant potential in supporting both quality control and predictive modelling in AM, particularly in polymer-based powder bed fusion. Collectively, the research studies emphasize how architectures address complementary aspects of process predictability and defect detection, from the level of convolutional networks to that of physics-informed models.

4.1. CNN-Based Defect Detection

Convolutional neural networks remain the most reliable instrument for classifying defects in images. A fine-tuned VGG16 model demonstrated that using infrared PBF-LB/P layer images achieved an accuracy of 99.09% and an F1 score of 0.972, recognizing curling defects with almost perfect reliability. In contrast, deeper architectures such as ResNet-50 and Xception performed poorly under class imbalance, achieving only 16.58% accuracy [

37,

38]. These results confirm once again that, in the AM environment, where thermal image cues are weak and data sets are small, model simplicity and dataset suitability can outweigh architectural novelty. Furthermore, CNNs are amenable to interpretability in the form of saliency maps that identify curling regions, enabling their use in real-time quality monitoring. This suggests an urgent need to move beyond accuracy metrics towards those that reflect real-world risk sensitivity, such as the number of false negatives in industries where defects are critical.

4.2. Temporal Modeling with CNN-LSTM

To capture time dynamics, a CNN-LSTM was integrated into infrared video streams. The network achieved a cumulative accuracy of 97.64% and perfect precision (100%), but recall was only 47.08%. This imbalance suggests that the detector is conservatively reliable in cases involving significant anomalies, but potentially liable to overlook minor or preliminary-stage imperfections [

22]. Although time-based modelling improves detection by integrating process evolution across frames, experiments show that it only works when a large defect is present. Balanced datasets are superior to simpler frame-based CNNs as they are sequence models. In practice, CNN-LSTMs show promise in detecting sequence-sensitive imperfections, but they are less robust when class imbalance is not alleviated.

4.3. Unsupervised Techniques / Generative Models

Ways of reducing reliance on labelled data using unsupervised approaches have been investigated. K-means clustering achieved an accuracy of around 97% in detecting curling; however, when used alongside a semi-supervised deep classifier, performance improved to 99.7%, approaching the level of full supervision. In contrast, deep autoencoders and GANs only achieved around 87% accuracy and did not generalize well to unknown datasets [

21]. These findings suggest that, while generative models can potentially detect anomalies within their training domain, they are themselves unstable and very dataset-specific. Traditional clustering, in conjunction with weak supervision, performed better, highlighting the importance of data structure and feature engineering in AM anomaly detection.

4.4. Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Thermal Prediction

In addition to classification, a physics-informed neural network (PINN) has been developed to predict thermal fields in PBF. By embedding heat transfer equations in the loss function, the network achieved a root mean square error (RMSE) of ~1.3 K, while reducing the computational cost by up to 70% compared to finite element calculations. In addition to modelling thermal distributions with high fidelity, the PINN enabled inverse analysis to deduce latent process parameters such as laser power, scanning speed, and hatching strategy [

32]. This dual functionality, in both forward simulation and discovering parameters, demonstrates the particular suitability of physics-informed learning for predictive maintenance and real-time process optimization.

4.5. Synthesis and Practical Implications

Overall, the results demonstrate the strengths of each approach, which complement those of the others. CNNs offer highly accurate, real-time detection of spatial anomalies, while LSTM hybrids can observe temporal dynamics, although they are prone to imbalance. Unsupervised techniques reduce the need for labelling, but lack robustness. PINNs offer computationally efficient, physically realistic thermal forecasts that are optimal for predictive control. Thus far, hybrids, including sensor fusion CNNs or semi-supervised clustering with deep classifiers, have achieved the highest accuracies, suggesting that integrating more than one approach offers the greatest promise for robust deployment in industry. If CNNs underperform in a minority of classes (e.g., deformity or powder deficiency), this reflects the class frequency bias reported in industrial data sets; stratified sampling and cost-sensitive losses mitigate this problem but do not eliminate it [

8]. In line with recent best practice guidance, the evaluation should go beyond single precision scores to include class-related metrics, cross-validation and reproducibility checks, ensuring comparability across independent studies [

46].

Table 2.

Summary of the application of deep learning to AM, as cited in the references. ’Acc’ = accuracy; ’F1’ = F1 score. Ribeiro and Schmid-Kietreiber addressed the classification of defects using imaging data, while Esmaeel concentrated on defect detection in an unsupervised setting. Aydemir developed a physics-based regression model for thermal fields.

Table 2.

Summary of the application of deep learning to AM, as cited in the references. ’Acc’ = accuracy; ’F1’ = F1 score. Ribeiro and Schmid-Kietreiber addressed the classification of defects using imaging data, while Esmaeel concentrated on defect detection in an unsupervised setting. Aydemir developed a physics-based regression model for thermal fields.

| Method |

Application |

Data Source |

Performance |

Strengths |

Limitations |

| VGG16 CNN [37,38] |

Defect detection (thermal images) |

IR images |

Acc. = 99.09%; F1 = 0.972 |

High accuracy, interpretable via Grad-CAM |

Requires labeled data; domain-specific |

| CNN-LSTM [22] |

Sequence-based defect detection |

IR video sequences |

Acc. = 97.64%; Prec. = 100%; Rec. = 47.08% |

Captures temporal trends; no false alarms |

Misses subtle defects; imbalance sensitive |

| K-Means + Classifier [21] |

Semi-supervised anomaly detection |

Thermal features |

Acc. = 99.7% |

Minimal labels required; robust within the dataset |

Weak cross-dataset generalization |

GAN/Autoencoder

[21] |

Unsupervised anomaly detection |

Thermal images |

~87% Acc. |

Works with unlabeled data; fast inference |

Training instability; poor generalization |

| PINN [32] |

Thermal prediction & parameter ID |

Simulation + IR data |

RMSE ≈ 1.3 K; 70% faster than FEM |

Physics-constrained; interpretable |

Complex training; scaling challenges |

5. Discussion

Interconnection of laboratories requires standardized data sets with shareable label taxonomy and reproducible distribution; without these resources, the comparison between paper and real-life results remains inconclusive. [

9]. A comparison of deep learning methods in AM shows that none of these approaches offers a universally optimum solution. Each approach has its own strengths and weaknesses, and its suitability depends on the type of monitoring mission, the availability of data, and the limitations of deployment.

Convolutional Neural Networks: CNNs are by far the most advanced and effective technique for detecting spatial defects in AM. Several studies have achieved an accuracy of 95–99% in discriminating between melt pool anomalies and curling defects using image data [

23,

38]. The main advantage is their ability to automatically extract spatially informative features, such as heat signatures and irregularities in contour shapes, while enabling fast inference suitable for real-time deployment. However, CNNs are standalone image processors, which limits their ability to interpret time evolution. Furthermore, performance is still very much dependent on the size and variety of the training dataset employed. In practice, the small number of defect instances in AM datasets remains a bottleneck, thus making transfer learning beneficial, albeit imperfect.

Recurrent Networks: Time models in the form of long short-term memory (LSTM) networks augment the strength of CNNs by integrating sequential knowledge, thereby enabling the detection of slow-moving anomalies that evolve at various levels. That CNN-LSTM demonstrated variants can detect subtle time patterns with high accuracy and precision when provided with balanced datasets, though recall is low. This highlights their strengths and weaknesses: while sequential modelling improves defect detection, it increases the complexity of training and computation, as well as introducing latencies in time-based monitoring [

22]. Unless the architecture is carefully balanced and fine-tuned, LSTMs tend to ignore rare yet significant defect occurrences.

Generative Models: When labelled data are unavailable, which is not uncommon in AM, weakly supervised and unsupervised autoencoders (AEs) and GANs hold great promise. They can identify patterns that deviate from the ’normal’ patterns they have learned and can even produce synthetic defect patterns to augment training sets [

21]. Semi-supervised classifiers combined with clustering achieved an accuracy of up to 99.7%, demonstrating the potential of hybrid unsupervised approaches. However, fully unsupervised GANs and AEs tended to underperform, achieving ~87% accuracy, due to their training instabilities and limited generalizability to new, unseen datasets. This suggests that weakly supervised approaches complement rather than replace supervised CNN approaches for high-stakes defect detection.

Physics-Informed Neural Networks: Unlike purely data-driven models, which exclude governing physical laws from the learning process, PINNs incorporate these laws, offering a link between physics-based simulations and machine learning. PINNs can achieve thermal field prediction errors as low as ~1.3 K, while reducing computational time by up to 70% compared to high-fidelity finite element models. Their ability to perform both forward prediction and inverse parameter identification demonstrates their value for predictive maintenance and process optimization [

32]. However, PINNs require careful loss weighting and are computationally expensive during training. They also struggle with multi-physics phenomena. Despite these limitations, their ability to generalize beyond the training domain makes them highly promising for industrial applications.

Integration and Hybridization: The above discussion suggests that these methodologies are not necessarily mutually exclusive. CNNs can provide rapid, high-accuracy, image-based monitoring, while LSTMs can extend detection into the time domain. GANs and AEs can offer either synthetic data or unsupervised anomaly detection, and PINNs can provide physically consistent predictions to enable process control. There is an increasing number of references to hybrid and multimodal approaches that combine these strengths, such as multi-sensor fusion CNNs [

47] and semi-supervised GAN-classifier pipelines [

21]. Such approaches may offer the robustness and flexibility required for deployment in industrial PBF-LB/P environments. Nevertheless, there are still questions about how these hybrid pipelines can be practically integrated into existing manufacturing workflows without disrupting throughput.

Multi-Sensor Fusion and Hybrid Frameworks: Recent advances in fault detection for PBF-LB highlight the combination of multiple sensing methods and machine learning to overcome the limitations of sensor-based monitoring. Multi-sensor fusion incorporates complementary physics, optical emissions, thermal fields, acoustic vibrations and three-dimensional geometry to capture orthogonal defect signature signatures. Studies show that the combination of near-infrared and CNN imaging provides the highest accuracy for predictions, while the combination of acoustic and optical components allows for the sub-millisecond detection of transient keyhole events [

48]. Similarly, 3D segmentation of the point cloud by indirect 2D projection improves the detection of small defects and high resolution thermography strongly correlates with micro-CT porosity [

39,

49,

50]. Machine learning approaches combine deep CNNs, feature-based ensembles, transfer learning and hybrid classifiers, balancing the feasibility of real time with the interpretability of the data. Gradual reinforcement of engineered thermal properties has proven effective for predicting porosity, while transfer learning reduces data requirements and improves the adaptability of the model to new fault classes [

51,

52]. In addition to detection, hybrid frameworks combine in-process monitoring with repair and control of the process. Local reassembly strategies restore density and reduce missing fusions, while closed loop parameter modifications with deep learning support reduce the severity of defects in polymer and composites systems [

53,

54]. Post-processing inspection, in particular micro-CT, provides the basic factual basis for model validation and training, and the voxelized thermal-CT fusion enhances porosity prediction [

51]. Despite these advances, challenges remain, in particular in the production of large-scale labelled data sets, the synchronization of heterogeneous sensor signals, and the validation of closed-loop remediation under industrial conditions. Future priorities include standardized multi-modal data sets with CT ground truth, lightweight mobile ML models, physics-based interpretation capability, and certified integration of detection with in-process repair processes, from fault detection to guaranteed quality in polymer PBF [

55,

56]. Despite the integration of supplementary sensors and advanced machine learning models, in situ monitoring of PBF-LB is often hampered by the difficulty of obtaining synchronized, high-reliability, multi-modal data and the lack of comprehensive data sets on the ground to train and validate the models [

57].

Implications: A primary implication is that AM monitoring is evolving from simple threshold-based controls and subjective human inspection to a level where algorithms can detect fine thermal or geometrical anomalies with a performance that often surpasses that of humans. However, problems remain in terms of generalization, interpretability, and implementation in real-time workflows. Future advances will likely rely on hybrid systems that use multiple classes of models, incorporate physics-informed constraints, and utilize multi-sensor streams.

Overall, CNNs remain the gold standard for detecting spatial defects. LSTMs offer temporal depth, albeit at the cost of increased complexity. GANs and AEs reduce label dependence, but stabilization and hybridization are required. PINNs, meanwhile, offer new approaches to physics-constrained simulation and predictive control. Hybridization between these methodologies, specifically designed for AM objectives, offers the most promise for providing practical, reliable, and scalable solutions.

6. Future Outlook

The use of DL applications in AM is set to increase significantly. However, technical limitations must first be addressed to enable wider implementation across industries. This article outlines the main ways to overcome current limitations and achieve real-time implementation while ensuring reliability and scalability.

Table 3.

Key challenges and potential solutions for applying deep learning to PBF-LB/P.

Table 3.

Key challenges and potential solutions for applying deep learning to PBF-LB/P.

| Challenge |

Description |

Proposed Solutions |

| Data Scarcity |

Lack of large, labeled datasets; rare defects are difficult to capture |

Self-supervised learning, GAN-based augmentation, transfer learning |

| Class Imbalance |

Abundance of normal process data vs. limited defect samples |

Oversampling/undersampling, anomaly detection with Autoencoders, and Few-shot learning |

| Scalability & Latency |

Heavy DL models are not suitable for real-time industrial monitoring |

Edge AI deployment, FPGA/GPU acceleration, lightweight CNNs (MobileNet) |

| Interpretability |

DL models act as “black boxes”; limited trust in safety-critical industries |

Explainable AI (Grad-CAM, SHAP, LRP), Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) |

| Generalization |

Models often overfit specific machines, materials, or geometries |

Domain adaptation, federated learning, multi-material datasets |

| Integration With Standards |

Industrial adoption is limited by a lack of standardized frameworks (ISO/ASTM) |

Hybrid digital twin + AI approaches, model certification under ISO/ASTM guidelines |

6.1. Data Limitations and Quality

A persistent challenge in developing successful DL models for AM is the limited availability of extensive, high-quality, and diverse datasets. While there are millions of annotated photos in computer vision, AM defect datasets are either scarce or proprietary. Future research will therefore focus on data-efficient learning. One answer to reducing data dependence is physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), which embed physical principles in model learning [

32]. Another promising solution is transfer learning and domain adaptation; these techniques allow models trained on one machine or material to generalize to another with very little additional data [

23]. Few-shot learning may even enable models to generalize to new defects based on just a few examples. Open datasets, in combination with benchmarking efforts, will accelerate progress; however, confidentiality remains an impediment from industry. Federated learning has been proposed as a way of sharing knowledge without distributing proprietary information [

2].

6.2. Real-Time Inferencing and Edge Processing

Using deep learning for real-time monitoring of additive manufacturing processes imposes stringent requirements on both computational speed and hardware resources. While most prior work outlines offline analyses utilizing high-performance GPUs [

22,

37] Commercial printers are equipped with only a few embedded processors. To address this, future research will use lightweight models such as MobileNet or EfficientNet variants coupled with compression and distillation techniques to enable use on edge devices [

58,

59]. Another promising route to high-throughput and low-latency inference, supporting high-resolution thermal and optical imaging, is FPGA or ASIC implementations for hardware acceleration [

60]. Closed-loop control is emerging, albeit in its infancy. For instance, a CNN-based in-process warping detection platform for fused filament fabrication has been developed, enabling corrective action during printing [

61]. Proofs of concept like this demonstrate the potential for real-time DL-based systems to provide feedback. In the future, interaction between streaming architectures and adaptive controllers will enable real-time defect correction. These developments suggest that, optimized architectures and hardware acceleration aside, real-time inference for DL in AM is feasible and approaching implementation in industry.

6.3. Generalization and Robustness

An important research task is to ensure that models trained under specific conditions remain trustworthy when confronted with new geometries, machines, or environmental variations. Domain shifts are ever-present in AM, and models are most likely to malfunction when they are taken outside of the training distribution [

21]. Domain randomization and advanced data augmentation can improve robustness, whereas PINNs can generalize better under physical constraint-based predictions [

21,

32]. Another avenue is uncertainty quantification: Bayesian DL and ensemble modelling can provide confidence intervals, enabling operators to determine when to trust AI outputs and when to rely on human judgement or non-destructive evaluation (NDE) methods.

6.4. Interpretability and Trust

For safety-critical AM environments to adopt them, stakeholders must be able to trust the outputs of the models. Explainable AI (XAI) tools, such as Grad-CAM, have been used to identify the areas responsible for defect classifications [

20,

37,

38]. Future systems should improve upon this by providing human-interpretable outputs, such as the type and severity of defects and their precise location in the build. PINNs are inherently interpretable due to their physically consistent outputs, whereas most purely data-driven models can be interpreted post hoc. Interactive dashboards that are transparent in their reasoning will enable DL to be adopted in engineers’ decision-making processes.

6.5. Integration and Scalability

As AM scales up to larger parts and longer prints, tracking becomes a significant data challenge. Hybrid edge–cloud systems will emerge, combining local models in the printer for rapid decision-making with cloud systems for advanced analysis, predictive modelling, and digital twin simulations [

47]. Digital twins, driven by PINNs and continually improved with sensor readings, can provide real-time ’what if’ predictions to inform adaptive control systems. Reinforcement learning can also be used for parameter tuning, whereby an agent progressively learns the optimal process conditions in simulated environments [

61].

6.6. Towards Standards and Industrial Adoption

Ultimately, establishing validation protocols and formulating global standards will be crucial for industry adoption. Conducting round-robin tests on standardized constructions with intentionally introduced flaws may become standard practice for validating DL-based monitoring tools [

60]. Organizations such as ASTM and ISO are currently developing guidelines for AI in the manufacturing sector. The development of trustworthy, validated, and explainable AI systems will significantly influence the level of industry adoption. The adoption of AI-driven quality control in AM across different industries will continue to be fragmented unless there is consensus on validation protocols.

7. Conclusion

Deep learning is set to transform AM by evolving open-loop systems into intelligent, adaptive, closed-loop configurations. This transformation promises not only technical progress but also measurable economic benefits, including reduced scrap rates, lower material and energy consumption, and a more sustainable production chain. This paper outlines the use of various deep learning architectures, including CNNs, LSTMs, GANs, autoencoders, and PINNs, to address key AM issues such as defect detection and thermal simulation. However, process control is not implemented in this work; the above-mentioned approaches focus only on process monitoring and defect detection, as active control of machine parameters was not possible with the available equipment. The comparison highlights the unique strengths of each model category: CNNs and CNN-LSTM deliver exceptional performance in defect detection by leveraging both thermal and imagery data streams. The semi-supervised and unsupervised variants diminish dependence on labelled datasets while facilitating broader application to raw process outputs. Beyond their technical performance, these models help minimize material waste and reduce rework, thereby improving cost efficiency and supporting resource conservation. PINNs enhance predictive accuracy by integrating domain-specific physics into models, thereby increasing both generalizability and user confidence. However, no single model offers a comprehensive solution. Evidence suggests that hybrid systems, which combine the strengths of different models, are more effective. These systems merge data-driven learning with physics-informed reasoning to achieve predictive control and anomaly detection. However, there are still challenges to overcome: achieving generalization across diverse geometries, machines, and materials; enabling low-latency, real-time inference within the constraints of industrial hardware; and establishing rigorous validation and interpretability standards for models in safety-critical scenarios. In addition to these technical hurdles, economically viable implementations and resource-efficient process designs will be key to enabling adoption on an industrial scale, particularly for energy-intensive AM applications. These challenges require algorithmic advancements and systems integration, including sensor fusion and user-focused interface enhancements. Deep learning has already brought measurable value to the additive manufacturing (AM) world by reducing defects, improving process knowledge, and enabling proactive quality control. As the field of research matures further, the convergence of AI and AM will deliver the next generation of ’smart’ manufacturing systems. In this future landscape, machines will observe every layer in real time, learn from each build, and respond immediately to maintain quality. Such systems will facilitate broader adoption in sectors such as aerospace and biomedicine, where reliability and high accuracy are paramount, and realize the full transformative potential of additive manufacturing as a production technology. So, the most important thing for progress in this field is to keep working to bring algorithmic innovation and industrial feasibility closer together. Crucially, these systems will not only enhance reliability and accuracy in sectors such as aerospace and biomedicine but also help meet global sustainability targets by minimizing waste, optimizing energy usage, and lowering overall production costs. The most important factor for progress in this field is therefore to bring algorithmic innovation, industrial feasibility, and sustainability considerations ever closer together.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the City of Vienna projects: MA23 - Projekt 29-22, “Artificial Intelligence” and MA23 - Projekt 30-25, “AI & VR Lab”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AM |

Additive Manufacturing |

| DL |

Deep Learning |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| RNN |

Recurrent Neural Network |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory |

| GAN |

Generative Adversarial Network |

| PINN |

Physics-Informed Neural Network |

| PBF-LB/P |

Powder Bed Fusion – Laser Beam of Polymers |

| PBF-LB/M |

Powder Bed Fusion – Laser Beam of Metals |

| AE |

Autoencoder |

| PDE |

Partial Differential Equation |

| PIML |

Physics-Informed Machine Learning |

| IR |

Infrared |

| Acc |

Accuracy |

| F1 |

F1 Score |

| RMSE |

Root Mean Square Error |

| XAI |

Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| Grad-CAM |

Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping |

| SHAP |

SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| LRP |

Layer-wise Relevance Propagation |

| FPGA |

Field Programmable Gate Array |

| ASIC |

Application-Specific Integrated Circuit |

| ISO |

International Organization for Standardization |

| ASTM |

American Society for Testing and Materials |

References

- Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B. Additive Manufacturing Technologies: 3D Printing, Rapid Prototyping, and Direct Digital Manufacturing, 3rd ed.; Springer, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Saimon, A.I.; Yangue, E.; Yue, X.; Kong, Z.J.; Liu, C. Advancing Additive Manufacturing through Deep Learning: A Comprehensive Review of Current Progress and Future Challenges. IISE Transactions 2025, 76, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everton, S.K.; Hirsch, M.; Stravroulakis, P.; Leach, R.K.; Clare, A.T. Review of in-situ process monitoring and in-situ metrology for metal additive manufacturing. Materials & Design 2016, 95, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xie, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yang, C.; Kollo, L.; Eckert, J.; Prashanth, K.G. Premature failure of an additively manufactured material. NPG Asia Mater 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, H.M.; Hamada, A.; Sebaey, T.A.; Abd-Elaziem, W. Selective Laser Sintering of Polymers: Process Parameters, Machine Learning Approaches, and Future Directions. JMMP 2024, 8, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scime, L.; Beuth, J. Using machine learning to identify in-situ melt pool signatures indicative of flaw formation in a laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing process. Additive Manufacturing 2019, 25, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamert, V.; Schmid-Kietreibera, M.; Bublin, M. A deep learning approach for real-time process monitoring and curling defect detection in selective laser sintering by infrared thermography and convolutional neural networks. 12th CIRP Conference on Photonic Technologies 2022, 7, 261–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkel, N.; Thölken, D.; Behler, K. Deep learning-based automated defect classification for powder bed fusion – Laser beam. European Journal of Materials 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Jough, F.; Dastres, R.; Arezoo, B. Additive Manufacturing Modification by Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning: A Review. Additive Manufacturing Frontiers 2025, 4, 200198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.; Belluomo, L.; Bici, M.; Prist, M.; Campana, F.; Cicconi, P. Machine learning in design for additive manufacturing: A state-of-the-art discussion for a support tool in product design lifecycle. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2025, 137, 2157–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffar, M.; Liao, S.; Lin, H.; Ehmann, K.; Cao, J. Geometry-agnostic data-driven thermal modeling of additive manufacturing processes using graph neural networks. Additive Manufacturing 2021, 48, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. Journal of Computational Physics 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Ye, Z. Selective Laser Sintering: Processing, Materials, Challenges, Applications, and Emerging Trends. J. Adv. Therm. Sci. Res. 2024, 11, 65–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, N.; Osman, R.B. Additive Manufacturing Technologies: Where Did We Start and Where Have We Landed? A Narrative Review. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2024, 37, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malashin, I.; Martysyuk, D. Powder particle classification with scanning electron microscopy images using machine learning techniques. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 286, 128001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. IEEE 1998, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR)) 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, F. Xception: Deep Learning with Depthwise Separable Convolutions. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klamert, V.; Achsel, T.; Toker, E.; Bublin, M.; Otto, A. Real-Time Optical Detection of Artificial Coating Defects in PBF-LB/P Using a Low-Cost Camera Solution and Convolutional Neural Networks. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 11273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeel, M.A. Process quality improvement of selective laser sintering using unsupervised machine learning algorithms. Master’s thesis, Vienna, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, L. Monitoring and recording printing errors through thermal imaging and deep learning: Recognition by image sequences. Master’s thesis, FH Campus Wien, Vienna, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Westphal, E.; Seitz, H. Corrigendum to: “A machine learning method for defect detection and visualization in selective laser sintering based on convolutional neural networks” [Addit. Manuf., 41 (2021), 101965]. Additive Manufacturing 2023, 75, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Ma, X.; Xu, J.; Li, M.; Cao, L. Deep Learning Based Monitoring of Spatter Behavior by the Acoustic Signal in Selective Laser Melting. Sensors (Basel) 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özel, T. Deep learning-based applications in metal additive manufacturing processes: Challenges and opportunities–A review. International Journal of Lightweight Materials and Manufacture 2025, 8, 453–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumar, G.; Philip, J. CNN-LSTM hybrid deep learning model for remaining useful life estimation. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Bartler, A.; Yang, B. Anomaly Detection Based on Selection and Weighting in Latent Space 2021.

- Säfström, D.; Persson, N. Image-based anomaly detection for metal additive manufacturing. Master’s thesis, Linköping University, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, J.; Shen, B.; Kong, Z.J. Anomaly detection in additive manufacturing processes using supervised classification with imbalanced sensor data based on generative adversarial network. J Intell Manuf 2024, 35, 2387–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, C. Attention-stacked Generative Adversarial Network (AS-GAN)-empowered Sensor Data Augmentation for Online Monitoring of Manufacturing System. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, H.; Wessels, H. Physics-Informed Surrogates for Temperature Prediction of Multi-Tracks in Laser Powder Bed Fusion 2023.

- Aydemir, T. Hybrid Thermal Modeling in Additive Manufacturing with Physics-Informed Machine Learning: Advanced Temperature Prediction for Powder Bed Fusion. Master’s thesis, FH Campus Wien, Vienna, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Lu, Z.; Hu, Y. Transfer learning-enhanced physics informed neural network for accurate melt pool prediction in laser melting. Advanced Manufacturing 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Peng, S.; Guo, J.; Wang, F. A review on physics-informed machine learning for monitoring metal additive manufacturing process. Advanced Manufacturing 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, S.J.; Ha, S.; Iten, R.; Klopotek, M.; Liu, Z. Interpretable Machine Learning in Physics: A Review 2025.

- Sutton, C.; Boley, M.; Ghiringhelli, L.M.; Rupp, M.; Vreeken, J.; Scheffler, M. Identifying domains of applicability of machine learning models for materials science. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid-Kietreiber, M. In-situ detection of printing defects during SLS using Convolutional Neural Networks. Bachelor Thesis, FH Campus Wien, Vienna, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid-Kietreiber, M. Increasing performance of a deep learning model for SLS printing defect detection. Bachelor Thesis, FH Campus Wien, Vienna, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Errico, V.; Palano, F.; Campanelli, S.L. Advancing powder bed fusion-laser beam technology: in-situ layerwise thermal monitoring solutions for thin-wall fabrication. Prog Addit Manuf 2025, 10, 3361–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabh, C.K.P.; Zhao, X. Single-camera Two-Wavelength Imaging Pyrometry for Melt Pool Temperature Measurement and Monitoring in Laser Powder Bed Fusion based Additive Manufacturing 2021.

- Özel, T. A review on in-situ process sensing and monitoring systems for fusion-based additive manufacturing. IJMMS 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillani, F.; MacDonald, E.; Villela, J.; Schmid, M.; Wegner, K. In situ monitoring of powder bed fusion of polymers using laser profilometry. Additive Manufacturing 2022, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Wang, D.; Zhao, K.; Gao, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, A.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, Y. Layer wise surface quality improvement in laser powder bed fusion through surface anomaly detection and control. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnebusch, S.; Anderson, D.; Bostan, B.; To, A.C. In Situ Infrared Camera Monitoring for Defect and Anomaly Detection in Laser Powder Bed Fusion: Calibration, Data Mapping, and Feature Extraction. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosoratti, E.; Potthoff, U.; Bennewitz, C.; Bambach, M. A training-free machine learning approach for 3D powder bed reconstruction and defect detection in PBF-LB/M. Prog Addit Manuf 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadiani, N.; Barnard, A.S.; Gunasegaram, D.; Fayyazifar, N. Best practices for machine learning strategies aimed at process parameter development in powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. J Intell Manuf 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusheef, A.S.; Shahbazi, M.; Hashemi, R. Deep Learning-Based Multi-Sensor Fusion for Process Monitoring: Application to Fused Deposition Modeling. Arab J Sci Eng 2024, 49, 10501–10522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Shao, J.; Liu, H.; Clark, S.J.; Gao, L.; Balderson, L.; Mumm, K.; Fezzaa, K.; Rollett, A.D.; Kara, L.B.; et al. Sub-millisecond keyhole pore detection in laser powder bed fusion using sound and light sensors and machine learning. Mater. Futures 2024, 3, 45001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, G.; Dong, F.; Liu, S. Real-time detection of powder bed defects in laser powder bed fusion using deep learning on 3D point clouds. VIRTUAL AND PHYSICAL PROTOTYPING 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, R.W.; Kutschke, Z.; Hart, A.J. High-Fidelity Optical Monitoring of Laser Powder Bed Fusion via Aperture Division Multiplexing. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, J.; Li, Z.L.; Taphorn, K.; Herzen, J.; Wudy, K. Porosity prediction in laser based powder bed fusion of polyamide 12 using infrared thermography and machine learning. Additive Manufacturing 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.A.; Crampton, A.; Mubarak, S.M. Enhanced detection of surface deformations in LPBF using deep convolutional neural networks and transfer learning from a porosity model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Weise, M.; Köhler, M.; Lacroix, F.v.; Ploshikhin, V.; Dilger, K. Local Remelting in Laser Powder Bed Fusion. JMMP 2024, 8, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Hou, J.; Yuan, S.; Yao, X.; Li, Y.; Zhu, J. Deep learning-assisted real-time defect detection and closed-loop adjustment for additive manufacturing of continuous fiber-reinforced polymer composites. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 2023, 79, 102431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Peng, X.; Kong, L.; Dong, G.; Remani, A.; Leach, R. Defect inspection technologies for additive manufacturing. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2021, 3, 22002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.; Brandt, M.; Trinchi, A.; Sola, A.; Molotnikov, A. Process monitoring and machine learning for defect detection in laser-based metal additive manufacturing. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing 2024, 35, 1407–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martucci, A.; Aversa, A.; Lombardi, M. Ongoing Challenges of Laser-Based Powder Bed Fusion Processing of Al Alloys and Potential Solutions from the Literature-A Review. Materials (Basel) 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNetV2: Smaller Models and Faster Training. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Uhrich, B.; Pfeifer, N.; Schäfer, M.; Theile, O.; Rahm, E. Physics-informed deep learning to quantify anomalies for real-time fault mitigation in 3D printing. Appl Intell 2024, 54, 4736–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saluja, A.; Xie, J.; Fayazbakhsh, K. A closed-loop in-process warping detection system for fused filament fabrication using convolutional neural networks. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2020, 58, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions, and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).