1. Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in men worldwide, with a lifetime risk of 1 in 9. It is primarily diagnosed in older men, with about 60% of cases in the U.S. occurring in those over age 65 [

1]. At initial diagnosis, most cancer is confined to the prostate, although some cases progress to advanced stages, frequently spreading to organs such as the bones and liver. In 2022, there were almost 1.5 million new cases globally, and age-standardized incidence rates are similar in the US and UK at approximately 75 per 100,000. In the same year, there were 34,000 deaths in the U.S. and 13,000 in the UK as a result of prostate cancer [

2]. Prostate cancer clearly presents a significant, continuing health and socioeconomic burden.

Advances in prostate cancer understanding have required in-depth comprehension of its associated pathobiology supported by the development of various research platforms and models. Such models include those based on cell lines for genetic studies and drug screening. However, this

in vitro work generally lacks a realistic representation of tumor heterogeneity and relevant tissue microenvironments. To address these limitations,

in vivo murine models have been evolved, providing a more complete depiction of prostate tumor microenvironments [

3]. During the progression of prostate cancer through to metastatic stages, the tumor microenvironment undergoes significant modification, including changes to the extracellular matrix (ECM) and vasculature. Significantly, there appear to be similarities in stromal alterations between primary tumor and bone metastases [

4], suggesting a critical role for the microenvironment (its architecture and components) in the effective disease progression. It has been well demonstrated that a particular challenge for prostate cancer therapy lies in its unique microenvironment, where, unusually, greater T-cell infiltration is correlated with poorer outcomes, as an example [

5].

As with many complex pathologies, there are several gaps and challenges in understanding the etiology and progression of prostate cancer. Recently, new methods to study and characterize prostate tissues have been explored, enabling new understandings of metastatic change.

Several physical science-based approaches have been developed for potential cancer diagnostic and monitoring probes. Of particular interest in the study of prostate cancers is mass spectrometry imaging, which has addressed issues of tissue heterogeneity and enabled the acquisition of lipid and metabolite profiles from different architectural prostate components, as well as their response to tumor progression [

6]. Another method capable of mapping on relatively wide histological scales and increasingly used to address various diagnostic demands is Raman spectroscopy. This promising optical method with high spatial resolution for cancer diagnosis and treatment monitoring has matured to clinical application [

7]. When applied to prostate cancer, it has indicated increased lipid synthesis and intracellular lipid heterogeneity within cancer cells [

8]. Perhaps a less mature analysis approach involves the measurement of X-ray scatter. X-rays are scattered whenever they pass through materials, which is the basis of crystallography. The fundamental experiment is to quantify the scatter features when tissues are illuminated with small-diameter X-ray beams. This diagnostic probe provides a detailed characterization of long- and short-range molecular order in terms of features such as molecular repeat distances and magnitude of disorder. It has previously been used to characterize ECM components of a small range of tissue types, especially those containing fibrous proteins (e.g., collagens), lipids, and ectopic calcifications [

9]. These components exhibit specific features at certain values of the transfer momentum,

q, and the cancer-induced modifications of these features can serve as structural biomarkers for early cancer detection. The technique we have termed

Vitacrystallography has been successfully applied in previous studies, for example, to investigate atypical collagens associated with breast tumors and ECM invasion [

10,

11], lipid structures in liver cancer [

12], and alterations to triglycerides in breast cancer [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17].

There is an increasing interest in cancer-associated lipid metabolism, given the suggested role of these molecules in supporting the rapid growth and survival of tumors. It was shown [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] that in human breast tissues, the peak at approximately

q = 14 nm

-1, corresponding to inter-fatty-acid molecular distances, is prominent in healthy samples, but its height reduces in cancerous samples. Concurrently, at approximately

q = 20 nm

-1, the magnitude of another peak, associated with the oxygen-oxygen distance in the tetrahedral structure of water, increases in cancerous tissues.

For the first time, our study takes the initial steps toward exploiting X-ray scattering to examine tissue ECM components associated with prostate cancer and its progression. We have used a mouse model to initiate prostate cancer and have subsequently tracked temporal changes (cancer trajectory) in adipose characteristics as measured by X-ray scattering. The results have been compared to those related to healthy mice, tracked across the same temporal periods. We have shown that the structural biomarkers in the mouse prostate tissues are the same as in the human breast tissues, with the magnitudes of the peaks associated with the lipids and water being modified as the tumor advances.

2. Results

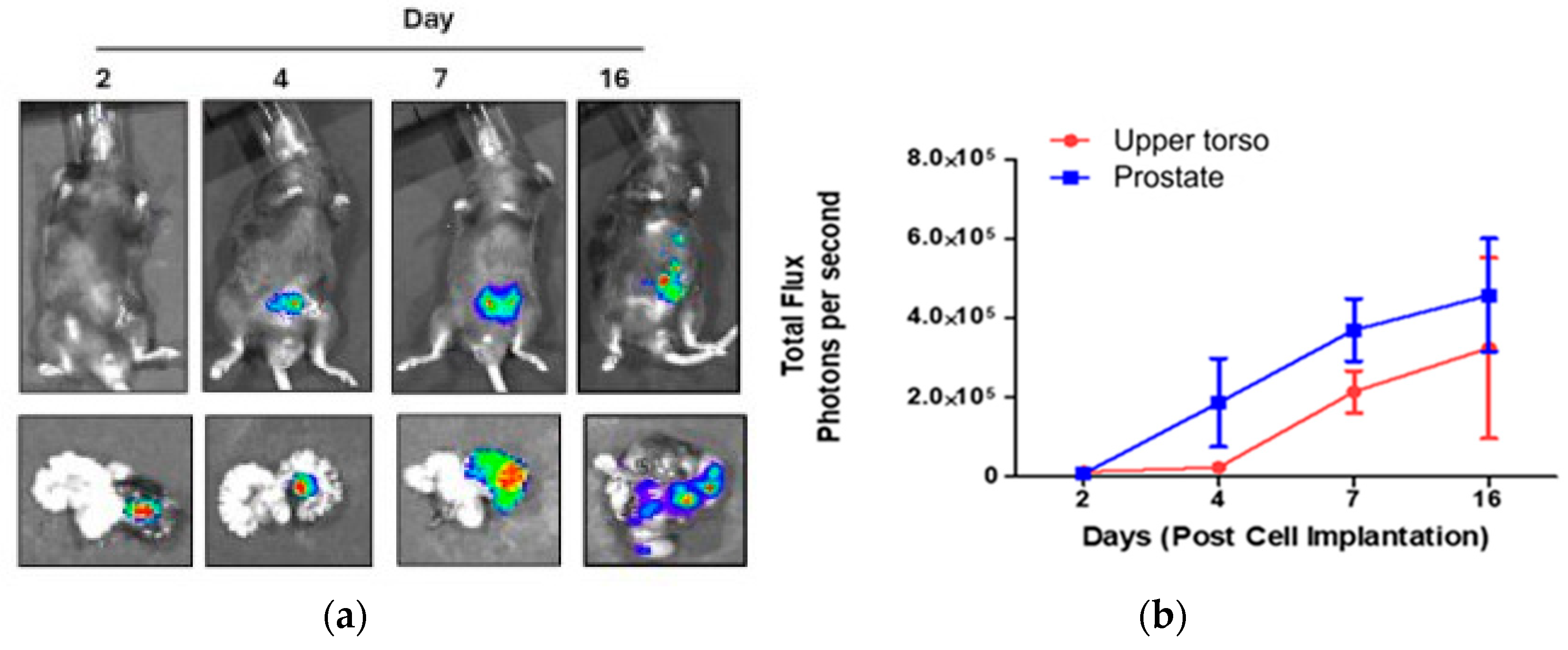

To establish the cancer trajectory, we induced prostate cancer in mice by inoculation of the cell line RM-1 into the left anterior prostate. Inoculated mice were sacrificed on Days 2, 4, 7, and 16 after the operation, along with control mice that were not inoculated. The cell line is luciferase-expressed, so the tumor development can be visualized using D-luciferin injection before the sacrificial. The images of the sacrificed mice and the removed prostates (with the left prostate lobe being on the right in the images) are displayed in

Figure 1 (a). The measured bioluminescence is shown in

Figure 1 (b) separately for the Region of Interest (ROI) of the excised prostate and ROI at the upper torso region from the whole-body image.

Increased bioluminescence flux indicates tumor progression, initially within the left lobe of the prostate and thereafter throughout the body. It should be noted that the right lobe of the prostate remains almost unaffected, so it can be used as an additional control.

The prostates of the inoculated and control mice were separated into the left and right parts, and the samples were prepared for the X-ray scattering measurements on beamline I22 at Diamond Light Source [

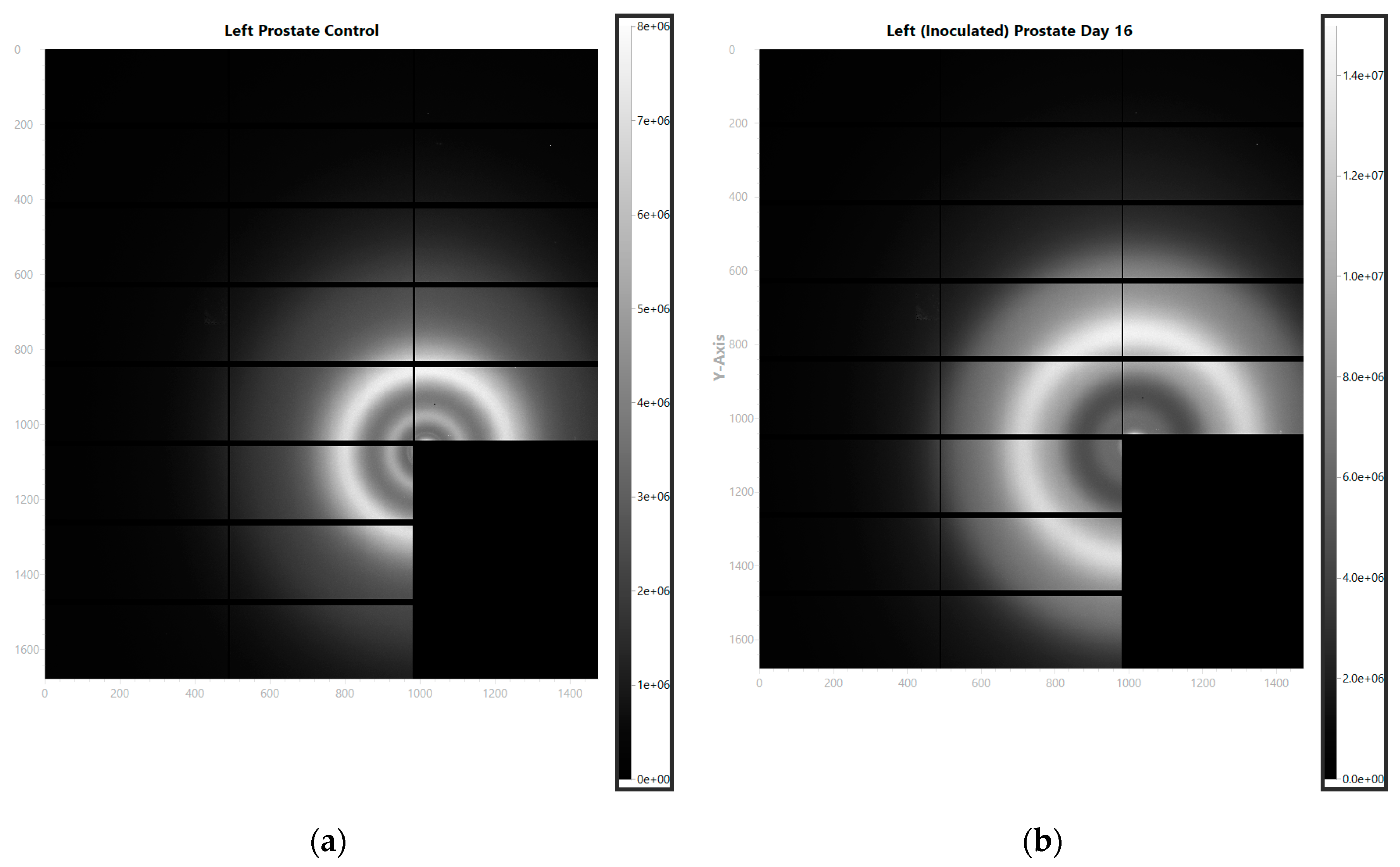

18]. The representative images of the observed scattering patterns are shown in

Figure 2 for (a) the control and (b) inoculated mice.

After azimuthal integration, the intensity of the scattered signal can be represented as a function of the distance to the center, which, in turn, can be recalculated in terms of the momentum transfer as

q = (4π sin

θ)/

λ, where 2

θ is the scattering angle and sin 2

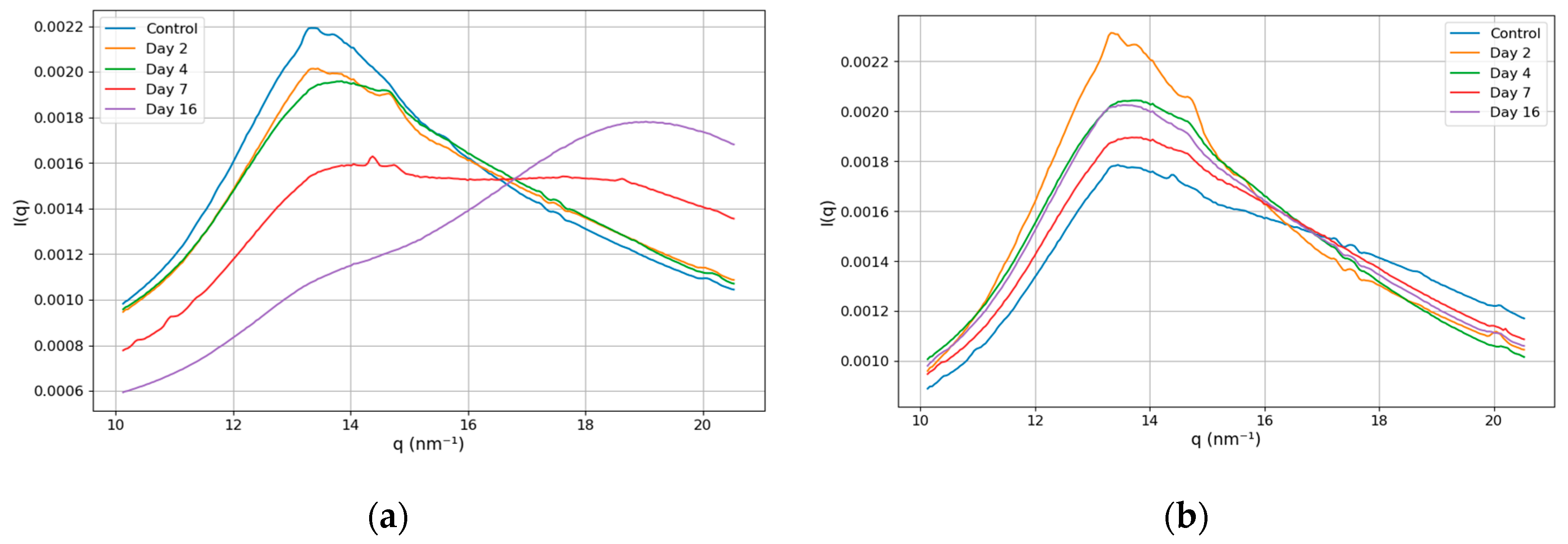

θ is the ratio of the distances from the pixel to the center and from the sample to the detector. In this work, we focus on the structural biomarker associated with the ratio of the magnitudes of the lipid and water peaks. In

Figure 3, we present the intensity dependence on the momentum transfer in the range of 10 - 20.5 nm

-1. The panels (a) and (b) show the results for the left and right lobes of the prostate, respectively.

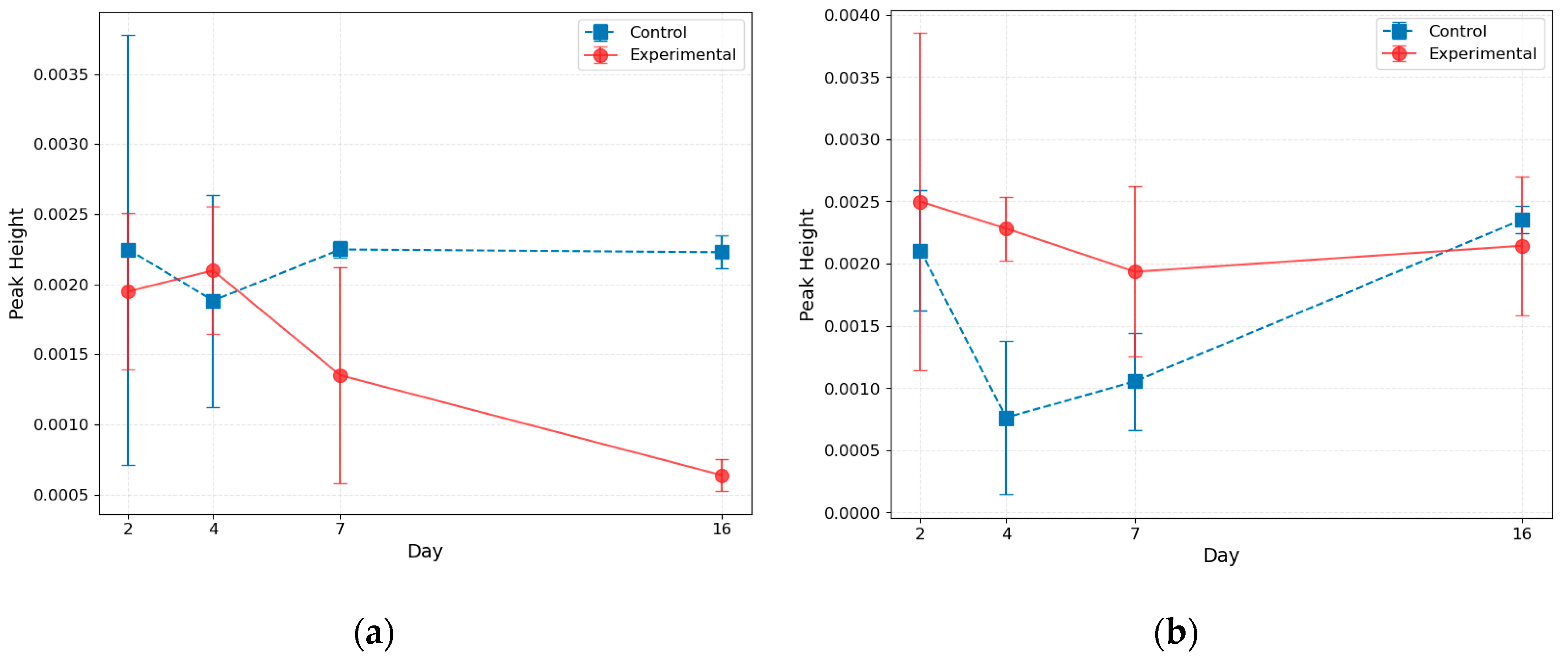

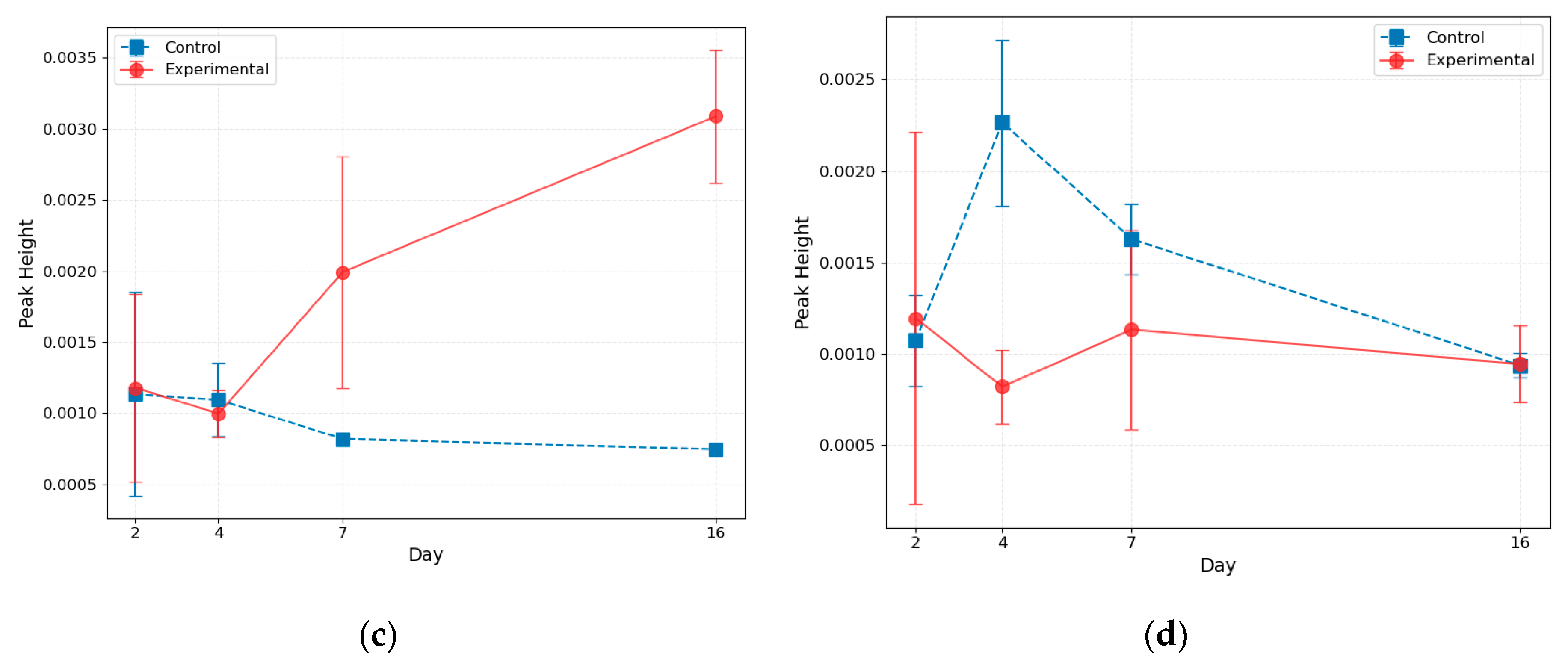

This figure reveals that the structure of the peaks changes for the left part of the prostate as the tumor progresses. For Days 2 and 4, the curves' shapes are similar to those of the control, while for Day 7, the lipid and water peaks have the same magnitude, and for Day 16, the water peak dominates. The curve's shape remains unchanged for the right part of the prostate. To get deeper insight, we perform the Gaussian fit of the peaks and demonstrate the results in

Figure 4. We also present the results for control mice sacrificed at specific time points.

This analysis confirms our conclusion that, for the cancer-affected left lobe, the magnitude of the lipid peak decreases, and the magnitude of the water peak increases as the tumor progresses. In the right lobe, these magnitudes remain essentially constant.

3. Discussion

Our results show that the prostate cancer trajectory in the mouse model can be observed in X-ray scattering patterns. The lipid peak, associated with the inter-fatty-acid molecular distances, reduces intensity as the tumor progresses, while the magnitude of the water peak, corresponding to the oxygen-oxygen distance, increases. The structural biomarker, based on the ratio of the lipid and water peaks, was previously used to classify human breast cancer samples [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, we showed here that this biomarker is also applicable to prostate cancer in mice. Moreover, we followed its modifications at various time points and established the cancer trajectory.

Our results have several implications. First, we showed that structural biomarkers are identical for humans and animals. Animal models allow researchers to perform experiments that are impractical or ethically impossible with humans, but the applicability of the obtained results can be questioned. X-ray scattering addresses the molecular structure of tissue components (lipids, in our case), which are the same for humans and animals, and we showed that the response to cancer is the same as well. Second, we showed that structural biomarkers are universal among the organs. It was found initially in human breast tissues but also appears in the mouse prostate. It simplifies the equipment for future diagnostics using X-ray diffractometers. It should be noted that even though the current results are obtained in the synchrotron facilities, this biomarker can be observed in laboratory apparatus as well [

16,

17]. Finally, and importantly, the established cancer trajectory could possibly be used to determine the efficiency of cancer treatment. Clinicians may be able to continuously monitor structural biomarkers to decide whether or not they return to healthy values along the trajectory.

Our current studies represent an initial step toward determining structural biomarkers, their temporal evolution (trajectory), and their applicability in cancer diagnosis and treatment. They should be expanded to involve more animals for better statistics and, in particular, to eliminate the variability of the control samples seen in Figs. 4 (b,d). They can also be extended to other organs within the mouse model. Other biomarkers need to be investigated, from the triglyceride peak at

q = 1.5 nm

-1 to the collagen reflexes and those of glycoproteins. We have already shown in the canine model [

19,

20] that the keratin in the dog's claws can serve as a cancer biomarker. We believe that the structural biomarkers monitored using X-ray scattering can potentially drive breakthroughs in the diagnostics of cancer and other diseases and our understanding of the functionalities of organisms.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mouse Inoculation

C57BL/6 male mice underwent prostatic implantation, during which the animals were anesthetized via inhalation using isoflurane in an oxygen carrier. A small incision was made in the lower abdomen. A total of 5×105 luciferase-expressing RM-1 cells were injected into the left anterior prostate using a 29g BD needle in 25µl of PBS. To minimize stress on the animals, absorbable sutures were used.

4.2. Sample Preparation

On Days 2, 4, 7, and 16 post-surgery, animals were injected intraperitoneal with 100µl of D-luciferin in PBS (15mg/ml) before imaging. The animals were anesthetized, and whole-body images were carried out using the IVIS imaging system. Animals were sacrificed at specific time points, and the prostate was excised and imaged. When the entire prostate was removed, a suture was placed through the left vesicle to highlight the correct injection side. Two healthy control mice were sacrificed at each time point, and their prostates were removed. The prostate samples were snap-frozen and shipped on dry ice to the experimental team for analysis.

4.3. XRD Measurements

Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering (WAXS) data were collected on beamline I22 at Diamond Light Source [

17], the UK’s national synchrotron facility. The experiments were conducted using a beam energy of 12.4 keV with a beam size of approximately 240×60 µm, and data were recorded using a Pilatus P3-2M detector. WAXS measurements were performed at a sample-to-detector distance of 170.21 mm, providing a

q-range of 0.72 to 45 nm

-1. For data collection, samples were placed in individual apertures measuring 5.2 mm in diameter and 2 mm thickness within a custom-designed 9×9 aperture aluminum gel-solution sample grid. Scotch tape was used to seal each aperture, ensuring a uniform sample thickness and maintaining sample hydration throughout the analysis. Data were collected from each sample as a 5×5 grid of points, with a step size of 500 µm and 10 data frames collected at each point. The acquisition time per frame was 100 ms.

4.4. Image Processing

Data were processed using standard I22 pipelines [

21] and the DAWN processing package [

22]. The main steps included:

Detector Calibration, with the import of calibration parameters to correct geometric distortions and ensure accurate spatial mapping.

Mask Generation, which applies an initial mask to exclude the beam stop shadow and dead pixels and mask dilation to eliminate edge effects and any remaining problematic regions.

Error Estimation, to set the Poisson error parameters to represent counting statistics correctly.

Data Pre-Processing, with beam stop diode readings for channel averaging, beam intensity correction, and data normalization by exposure time to account for variations in measurement duration.

Frame Processing, which averages the frames collected at each position to obtain a single 2D diffraction pattern and subtracts the background.

Advanced Corrections, applying powder diffraction intensity corrections for geometric and absorption effects and performing azimuthal integration to convert 2D patterns into 1D intensity profiles.

Final Data Conditioning, to remove the NaN values and scaling intensities as needed.

After these steps, each measured position yielded a single 1D diffraction profile suitable for further analysis.

4.5. Data Processing

Following image processing, the dataset included azimuthally integrated 1D profiles from 25 mice distributed across five experimental groups: Control, Day 2, Day 4, Day 7, and Day 16, with five mice per group. Each profile contained 414 data points spanning q-ranges from 3.25 to 21 nm-1, representing measurements from both the left and right prostate sides. Following manual cleaning, 564 individual measurements were retained for analysis.

The 1D profiles were normalized using L1 normalization to ensure consistency across measurements while retaining the relative intensity distribution within each profile. Group-level averaging provided preliminary insights into differences between experimental groups, guiding the identification of two primary peaks in our q-range of interest at approximately 13.5 and 18 nm-1.

Each of the 564 measurements underwent independent curve fitting using a composite model, which includes three Gaussian peaks and amorphous scattering with inverse

q to the fourth power dependence:

where

,

, and

are the peak heights, positions, and standard deviation, respectively; B is the magnitude of the amorphous scattering, and C is a constant background. Averaging the fitting parameters across groups revealed trajectories describing the evolution of these peaks over time.

Control measurements were matched to their corresponding time points before averaging fitting parameters, enabling accurate tracking of parameter variations across experimental stages. This computational approach facilitated the extraction and comparison of structural information, shedding light on the temporal changes in the identified peaks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M. and P.L.; inoculation, H.N; sample preparation, K.T., A.A., L.A., and C.G.; methodology, O.A., S.D., H.N., C.G., K.R., and P.L.; software, O.A. and S.D.; validation, K.R., O.S., L.M., and P.L.; formal analysis, O.A.; investigation, O.A., S.D., A.A., C.G., and K.R.; data curation, O.A., S.D., and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, O.A., S.D., H.N., C.G., K.R., and L.M.; writing—review and editing, C.G., K.R., O.S., L.M., and P.L.; visualization, O.A. and H.N.; supervision, C.G., K.R., L.M., and P.L.; project administration, O.S. and P.L.; funding acquisition, O.S. and P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Innovate UK, part of UK Research and Innovation, through the Smart Grant scheme (Grant number 10063925).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ulster University and then approved by the Department of Health NI (PPL 2951, approved Dec 2023).

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

P.L. is a shareholder of EosDx UK Ltd, O.A., S.D., and O.S. are employees of EosDx UK Ltd, K.R. and L.M. are consultants of EosDx UK Ltd.

References

- Rawla, P. Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Fund: Prostate Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/preventing-cancer/cancer-statistics/prostate-cancer-statistics/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Saranyutanon, S.; Deshmukh, S.K.; Dasgupta, S.; Pai, S.; Singh, S.; Singh, A.P. Cellular and Molecular Progression of Prostate Cancer: Models for Basic and Preclinical Research. Cancers 2020, 12, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; La Manna, F.; Bonollo, F.; Sampson, N.; Alberts, I.L.; Mingels, C.; Afshar-Oromieh, A.; Thalmann, G.N.; Karkampouna, S. Tumor microenvironment mechanisms and bone metastatic disease progression of prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 2022, 530, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, S.; Kryza, T.; Batra, J.; Clements, J. Remodelling of the tumour microenvironment by the kallikrein-related peptidases. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, M.K.; Høiem, T.S.; Claes, B.S.; Balluff, B.; Martin-Lorenzo, M.; Richardsen, E.; Krossa, S.; Bertilsson, H.; Heeren, R.M.; Rye, M.B.; Giskeødegård, G.F.; Bathen, T.F.; Tessem, M. Spatial differentiation of metabolism in prostate cancer tissue by MALDI-TOF MSI. Cancer Metab. 2021, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auner, G.W.; Koya, S.K.; Huang, C.; Broadbent, B.; Trexler, M.; Auner, Z.; Elias, A.; Mehne, K.C.; Brusatori, M.A. Applications of Raman spectroscopy in cancer diagnosis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2018, 37, 691–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaba, F.; Tipping, W.J.; Salji, M.; Faulds, K.; Graham, D.; Leung, H.Y. Raman Spectroscopy in Prostate Cancer: Techniques, Applications and Advancements. Cancers 2022, 14, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosling, S.B.; Arnold, E.L.; Davies, S.K.; Grand Challenge PRECISION Consortium. Microcalcification crystallography as a potential marker of DCIS recurrence. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conceição, A.L.C.; Müller, V.; Burandt, E.C.; Mohme, M.; Nielsen, L.C.; Liebi, M.; Haas, S. Unveiling breast cancer metastasis through an advanced X-ray imaging approach. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohd Sobri, S.N.; Abdul Sani, S.F.; Sabtu, S.N.; Looi, L.M.; Chiew, S.F.; Pathmanathan, D.; Chio-Srichan, S.; Bradley, D.A. Structural Studies of Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition Breast Tissues. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xueqi, L. Structural evolution of lipid droplets in murine liver cancer. M.S. University of Illinois, USA, 2023.

- Conceição, A.L.; Antoniassi, M.; Poletti, M.E. Analysis of breast cancer by small angle X-ray scattering. Analyst 2009, 134, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conceicao, A.L.C.; Antoniassi, M.; Poletti, M.E. Assessment of the differential linear coherent scattering coefficient of biological samples. Nucl. Instr. Meth. Phys. Res. A 2010, 619, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceicao, A.L.C.; Meehan, K.; Antoniassi, M.; Piacenti-Silva, M.; Poletti, M.E. The influence of hydration on the architectural rearrangement of normal and neoplastic human breast tissues. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J.; Blinchevsky, B.; Slight, M.; Tanaka, A.; Lazarev, A.; Zhang, W.; Aram, B.; Ghadimi, M.; Lomis, T.; Mourokh, L.; Lazarev, P. Structural Biomarkers for Breast Cancer Determined by X-Ray Diffraction, In Quantum Effects and Measurement Techniques in Biology and Biophotonics, Aiello, C. , Polyakov, S.V., Derr, P., Eds.; Proc. SPIE 2024, 12863, 1286302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, S.; Blinchevsky, B.; Friedman, J.; Gerbelli, B.; Ajeer, A.; Adams, L.; Greenwood, C.; Rogers, K.; Mourokh, L.; Lazarev, P. Vitacrystallography: Structural Biomarkers of Breast Cancer Obtained by X-ray Scattering. Cancers 2024, 16, 2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.J.; Alcock, S.G.; Davidson, L.S.; Emmins, J.H.; Hiller Bardsley, J.C.; Holloway, P.; Malfois, M.; Marshall, A.R.; Pizzey, C.L.; Rogers, S.E.; Shebanova, O.; Snow, T.; Sutter, J.P.; Williams, E.P.; Terrill, N.J. I22: SAXS/WAXS beamline at Diamond Light Source - an overview of 10 years operation. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2021, 28, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alekseev, A.; Yuk, D.; Lazarev, A.; Labelle, D.; Mourokh, L.; Lazarev, P. Canine Cancer Diagnostics by X-ray Diffraction of Claws. Cancers 2024, 16, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alekseev, A.; Avdieiev, O.; Murokh, S.; Yuk, D.; Lazarev, A.; Labelle, D.; Mourokh, L.; Lazarev, P. Fourier Transformation-Based Analysis of X-Ray Diffraction Pattern of Keratin for Cancer Detection. Crystals 2025, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauw, B.R.; Smith, A.J.; Snow, T.; Terrill, N.J.; Thünemann, A.F. The modular small-angle X-ray scattering data correction sequence. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2017, 29, 1800–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filik, J.; Ashton, A.W.; Chang, P.C.Y.; Chater, P.A.; Day, S.J.; Drakopoulos, M.; Gerring, M.W.; Hart, M.L.; Magdysyuk, O.V.; Michalik, S.; Smith, A.; Tang, C.C.; Terrill, N.J.; Wharmby, M.T.; Wilhelm, H. Processing two-dimensional X-ray diffraction and small-angle scattering data in DAWN 2. J. Appl. Cryst. 2017, 50, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).