1. Introduction

Xylitol is a well-known preventative product used in dentistry for decades [

1]. Erythritol and xylitol are polyols extensively researched and demonstrated to have notable anti-cariogenic and anti-periodontal disease properties with appropriate use [

2,

3,

4]. Polyols have been used traditionally (for about 80 years) to replace sugar in sweet foods to block tooth enamel demineralization and to reduce postprandial blood glucose surges. However, the benefits of added dietary polyols go beyond removing sugar. Emerging evidence shows that xylitol and erythritol can play several functional roles in actively supporting oral and systemic health maintenance with anti-biofilm, antioxidant, and anti-diabetic effects. Xylitol and erythritol disrupt keystone oral disease initiators such as S. mutans (caries) and P. gingivalis (periodontal disease) while acting as prebiotics and helping to balance and maintain a healthy microbiome, beginning with the oral gateway microbiome, which supports innate immunity and disease resistance [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14].

The role of the microbiome in cancer development and treatment is now well-recognized [

15]. Indeed, the interactions between microbiome and cancer have generated research into the complex microbial communities and the possible mechanisms through which the microbiota influence cancer prevention, carcinogenesis, and anti-cancer therapy. In addition, developing next-generation prebiotics and probiotics designed to target specific diseases is considered extremely urgent [

16]. Ideally, healthcare providers will one day optimally implant effective prebiotics, probiotics, and the derived postbiotics to ameliorate disease [

17]. Immune elimination and immune escape are reported as hallmarks of cancer, and both can be partly bacteria-dependent, with the shaping of immunity by mediating host immunomodulation. In addition, host immunity regulates the microbiome by altering bacteria-associated signaling to influence tumor surveillance. Cancer immunotherapy, including immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), appears to have heterogeneous therapeutic effects in different individuals, partially attributed to the microbiota [

18]. In the era of personalized medicine, the microbiota and its interactions with cancer must be better understood, and manipulating the gut microbiota to improve cancer therapeutic responses could be necessary for future cancer treatment [

19].

Research demonstrates the inhibitory properties of xylitol with many cancer cell lines when administered both dietary and systemically [

20,

21,

22]. Because xylitol exhibits almost no side effects and is safely utilized by healthy human cells, it could be a beneficial natural supplement for potentially inhibiting cancer cell proliferation [

23,

24]. Additionally, xylitol inhibits angiogenesis, thereby decreasing the vascularization of the tumor [

25]. Increased vascularization would support tumor growth and possibly cancer metastasis.

Interestingly, the typical human is reported to endogenously produce approximately 15 gm per day in the liver, making xylitol a natural product [

26]. Indeed, xylitol is utilized by the mitochondria of cells as the precursor to the first step in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (also known as the citric acid cycle or the Krebs cycle), with xylitol dehydrogenase on the cristae converting xylitol to d-xylulose which then converts NADP to NADPH [

27]. In addition to the liver production of xylitol, many plants, such as blueberries, strawberries, plums, cauliflower, and even oats, have substantial amounts of xylitol naturally present [

28]. There is considerable overlap when comparing the list of xylitol-containing foods to the American Heart Association's “heart-friendly” foods list. Xylitol has been utilized even in diabetes prevention and as an anti-inflammatory [

29,

30].

Previous research with xylitol supplementation in animal models has had positive results in inhibiting cancer cell lines and xenografts [

31,

32]. Combination treatments with xylitol have also been reported as successful [

33]. Animal models are considered the first phase of cancer research, looking for potential therapeutic agents [

34]. This research study intends to use two mouse models to evaluate the efficacy of a higher concentration (20%) and the modality of direct delivery (intratumorally) of xylitol in cancer.

Metabolomics can be used to identify cancer biomarkers and the drivers of tumorigenesis [

35]. Metabolism is dysregulated in cancer cells to support uncontrolled cell proliferation [

36]. This dysregulation of cellular metabolism leads to specific metabolic phenotypes. These metabolic phenotypes can be used for earlier cancer diagnosis, clinical trials, patient selection, and as biomarkers of treatment response. Drugs that selectively target metabolic enzymes and, with precision medicine and nutrition, can affect cancer-related unique metabolic dependencies [

37]. Cancer outcomes and the patient's quality of life may be affected by cancer and cancer treatments in individual and complex manners due to the whole-body interaction and the influences of diet and exercise [

38].

The purpose was to evaluate the effects, including cell line inhibition of xylitol on tumor progression, in two syngeneic mouse cancer models. Specifically, this pilot study measured tumor growth inhibition from two cancer cell line implantations in two syngeneic mouse cancer models, 4T1 mammary carcinoma and B16F10 melanoma [

39], with 20% xylitol (prebiotic) solution intratumorally and peritumorally administered daily.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Mice and Study Design

This IACUC approved study (IS000097440) included two strains of immunocompetent female mice: 20 C57BL/6 and 20 BALB/c mice for a total of 40 mice. The mice were acquired from Charles River Laboratories, Durham, USA. The BALB/c group was injected with 4T1 mammary carcinoma cells (1 x 10^6 cells into the 4th mammary gland), and the C57BL/6 group was injected with B16F10 melanoma cells (1 x 10^6 cells into the flank). When tumor sizes reached 50 to 100 mm3, both treatment groups (10 each) were injected daily with 100 ul of 20% xylitol solution intratumorally (75%) and subcutaneously (25% peritumoral). The xylitol was acquired from Xlear, American Fork, Utah. A 20% solution was the highest concentration of xylitol possible to formulate. Previously published research reported concentrations of 5 and 10%, but the principal investigator believed it was possible to use a higher percentage in this study. Control mice received sterile saline (10 each) with the same daily treatment frequency and amount (Monday – Sunday) as the xylitol group. All mice's body weight and tumor volume were measured every other day. All tumor volumes were measured by caliper and calculated by the following modified ellipsoidal formula:

Tumor volume = 1/2(length × width2)

Or V= (L×W2)/2, L is length and W is width. Where L is the greatest longitudinal diameter (length) and W is the greatest transverse diameter (width). This formula is the standard in the Developmental Therapeutics Core at Northwestern University.

Table 1.

Forty mice with two syngeneic models (20 each) and ten control versus ten experimental mice in each group. The two syngeneic models were used to check the possible efficacy of xylitol therapy with both immune systems, Adaptive and Innate.

Table 1.

Forty mice with two syngeneic models (20 each) and ten control versus ten experimental mice in each group. The two syngeneic models were used to check the possible efficacy of xylitol therapy with both immune systems, Adaptive and Innate.

| Mouse strain |

Cancer cell line |

Immune system |

Mice |

| BALB/C |

4T1 mammary carcinoma |

Adaptive immunity |

20- 10 controls and 10 experimental |

| C57BL/6 |

B16F10 melanoma |

Innate immunity |

20- 10 controls and 10 experimental |

Euthanization protocol:

All mice were euthanized when control tumor volumes were equal to or larger than 2000 mm3 or if mice lost more than 20% of their original body weight. In addition, euthanization was performed if there were other severe clinical health issues (e.g., paralysis) that would cause undue discomfort. Xylitol was injected daily until significant changes in the tumor sizes were observed (the study was to be terminated if no changes were seen per IACUC protocols). Euthanasia was also performed according to IACUC protocol. Animals were not combined from different cages, and when euthanizing some of the mice from a cage, the rest of the animals remained in their original cage. The maximum number of mice per cage was five, and the CO2 flow rate per mouse cage was 3 L/min until one minute after breathing stopped. Euthanasia was confirmed by cervical dislocation.

2.2. Sample Collection

Immediately following euthanasia, tumors were harvested, sectioned, and one-half fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 48 hours. The other half of the tumor was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for metabolomic analysis. Tumor tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned into 4-5 µm-thick sections, placed on microscopic slides, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) by the Mouse Histology and Phenotyping Laboratory of Northwestern University. Microscopic slides were imaged using an Olympus BX45 microscope with an Olympus DP28 digital camera. Digital images were visualized using Olympus cellSens imaging software (version 4.2).

Metabolomic samples were analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography, high-resolution mass spectrometry, and Tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS). Specifically, the system consisted of a Thermo Q-Exactive in line with an electrospray source and an Ultimate3000 (Thermo) series HPLC consisting of a binary pump, degasser, and auto-sampler outfitted with an Xbridge Amide column (Waters; dimensions of 3.0 mm × 100 mm and a 3.5 µm particle size). The mobile phase A contained 95% (vol/vol) water, 5% (vol/vol) acetonitrile, 10 mM ammonium hydroxide, 10 mM ammonium acetate, pH = 9.0; B was 100% Acetonitrile. The gradient was as follows: 0 min, 15% A; 2.5 min, 30% A; 7 min, 43% A; 16 min, 62% A; 16.1-18 min, 75% A; 18-25 min, 15% A with a flow rate of 150 μL/min. The capillary of the ESI source was set to 275 °C, with sheath gas at 35 arbitrary units, auxiliary gas at 5 arbitrary units, and the spray voltage at 4.0 kV. In positive/negative polarity switching mode, an m/z scan range from 60 to 900 was chosen, and MS1 data was collected at a resolution of 70,000. The automatic gain control (AGC) target was set at 1 × 106, and the maximum injection time was 200 ms. The top 5 precursor ions were subsequently fragmented in a data-dependent manner, using the higher energy collisional dissociation (HCD) cell set to 30% normalized collision energy in MS2 at a resolution power of 17,500. Besides matching m/z, metabolites are identified by matching either retention time with analytical standards and/or MS2 fragmentation pattern. Xcalibur 4.1 software and Tracefinder 4.1 software, respectively (from Thermo Fisher Scientific), carried out data acquisition and analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Tumor Volume

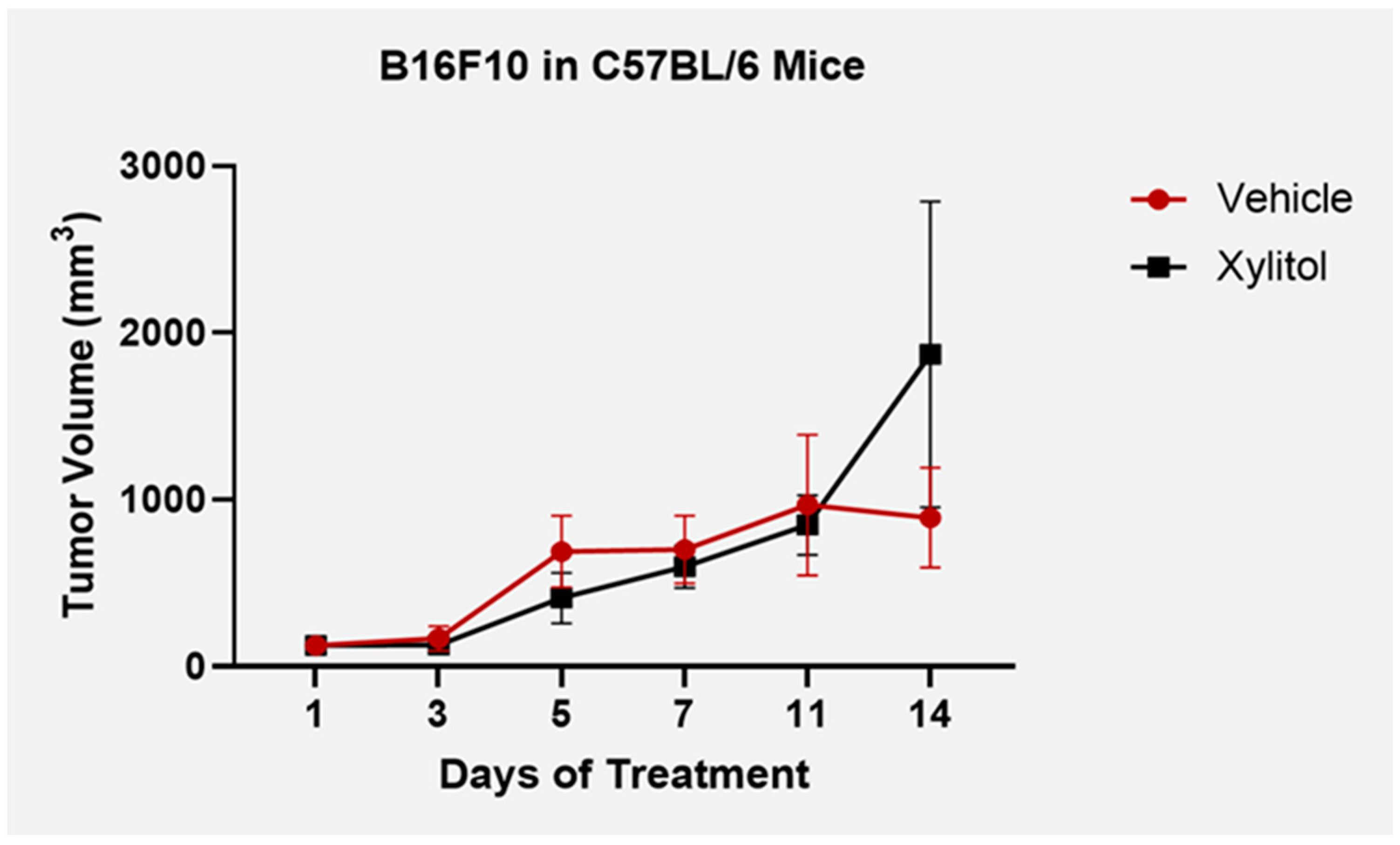

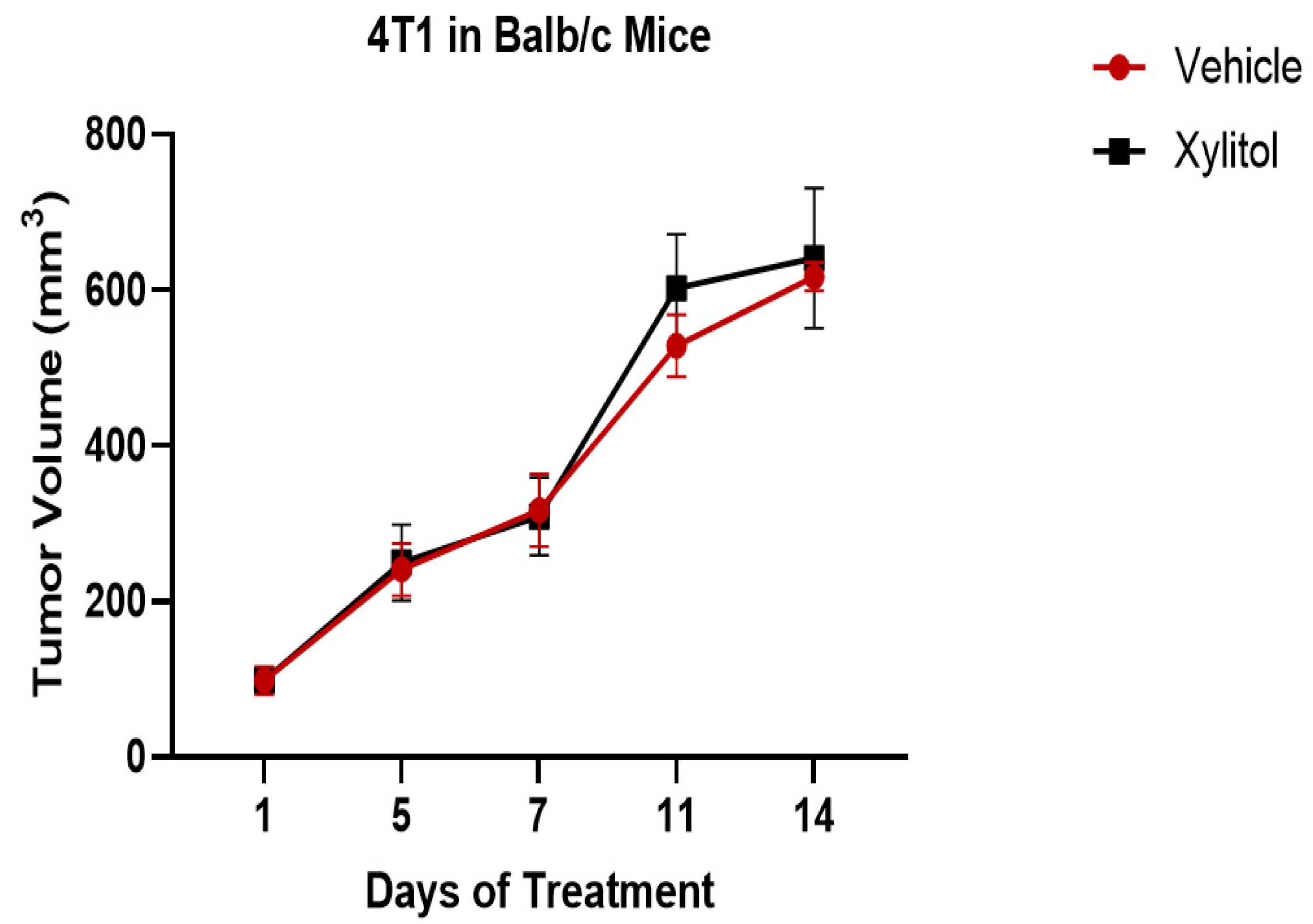

After five days of 20% xylitol injections, tumor volumes were reduced by 40% in the C57BL/6 group with the B16F10 melanoma cells (see

Figure 1), but with the BALB/c + 4T1 cancer line (adaptive immunity), the tumor growth was not significantly different between the control and the experimental (xylitol). With repeated intra-tumoral injections, the tumor stroma deteriorated in the B16F10 tumors, resulting in substantial xylitol leaking onto the skin surface. Afterward, experimental and control tumor volumes would become clinically comparable by study termination at day 14 (see

Table 2). Interstitial tumor pressure increased, preventing effective injection of the solution after five days.

Figure 1.

Tumor volumes B16F10 + C57BL6 model until day 14 and study termination. Tumor volume was reduced by xylitol compared to the controls (saline) until tumor stroma degraded, allowing 20% xylitol solution to leak out. Standard deviation bars were calculated from tumor volumes. Statistical differences were seen on days 5 and 14 of the T-test analysis, with a P value < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Tumor volumes B16F10 + C57BL6 model until day 14 and study termination. Tumor volume was reduced by xylitol compared to the controls (saline) until tumor stroma degraded, allowing 20% xylitol solution to leak out. Standard deviation bars were calculated from tumor volumes. Statistical differences were seen on days 5 and 14 of the T-test analysis, with a P value < 0.05.

Figure 2.

There were no statistically significant differences between the tumor volumes of the experimental (xylitol) group and the control (saline) in the 4T1 syngeneic model with the Balb/c mice (T-test analysis, P value > 0.05).

Figure 2.

There were no statistically significant differences between the tumor volumes of the experimental (xylitol) group and the control (saline) in the 4T1 syngeneic model with the Balb/c mice (T-test analysis, P value > 0.05).

3.2. Metabolomic Analysis

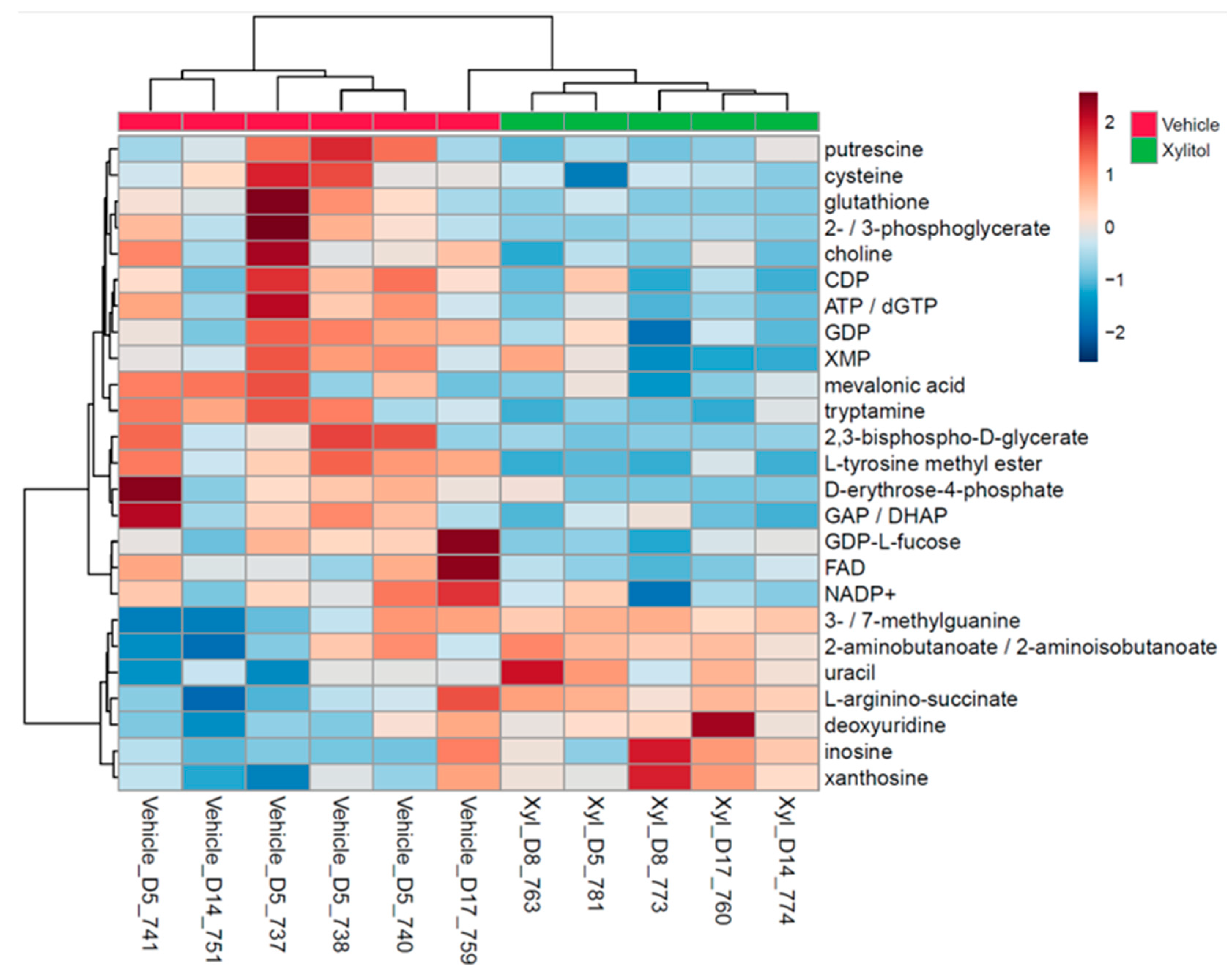

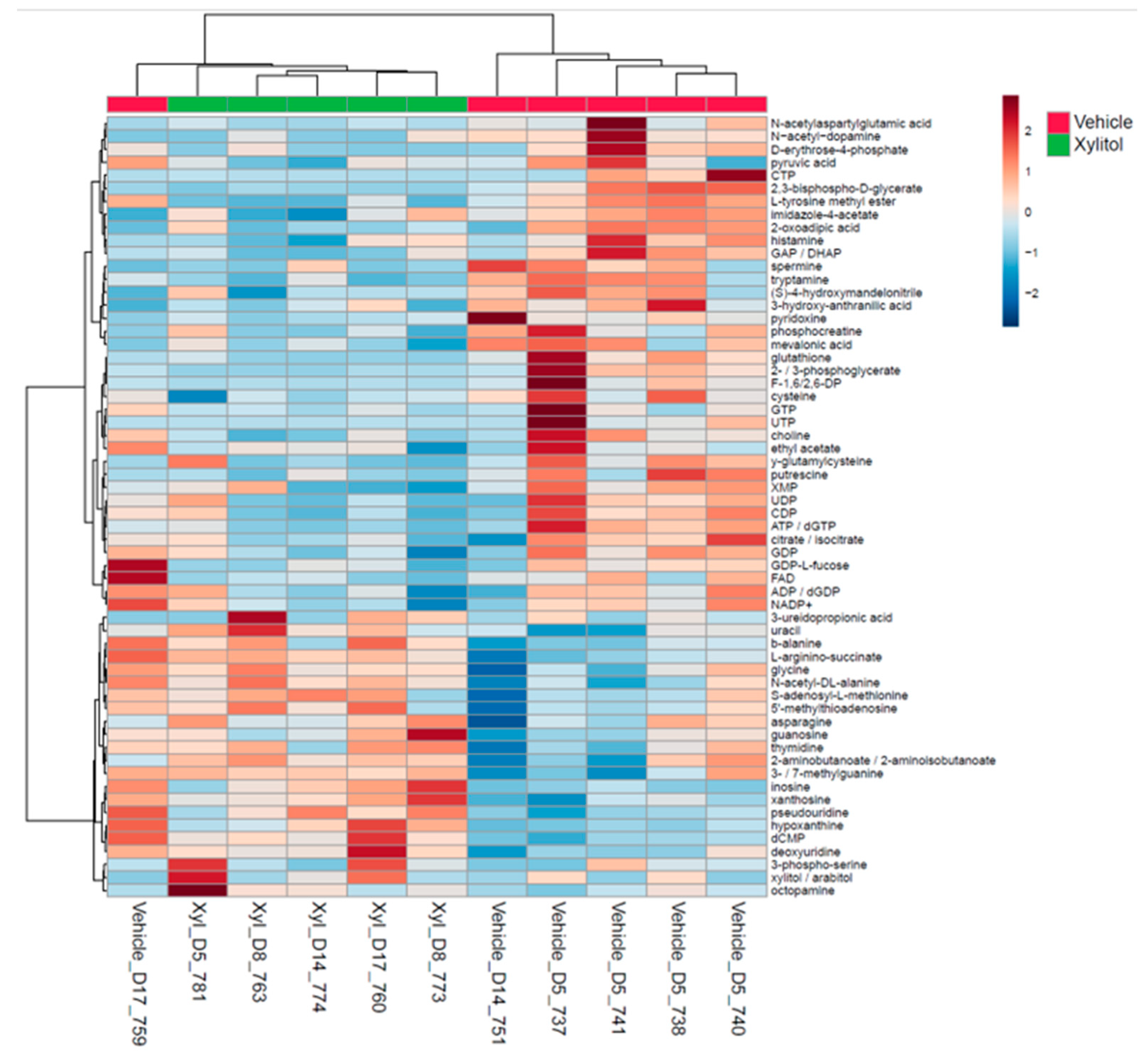

Metabolomic analysis revealed apparent differences between experimental and control tumor cellular metabolism. Lymph node histological analysis demonstrated metastasis in both groups by the time of euthanasia. The metabolomic analysis demonstrates that intratumoral xylitol reduces tumor cell production of histamine, NADP+, ATP, and glutathione, thereby affecting the availability of reactive oxidative species and the host immune response (see

Figure 2). The xylitol group showed significantly decreased phosphocreatine, citrate, and pyruvic acid levels, signifying metabolic stress likely due to inhibiting mitochondrial metabolism within the tumor cells. Notably, xylitol levels were increased in tumors, demonstrating that xylitol accumulates in cancer cells and suggests that the effects of xylitol are likely due to cancer cell-intrinsic effect on metabolism (see

Table 1). In addition, a decrease in tumor glutathione may affect the innate immune response, enhancing the impact of reactive oxidative species.

Table 2.

Important features of the tumor cell metabolism listed by fold change values and t-test P values. Intertumoral xylitol presents changes to the metabolic products that may influence tumor development. This table data was generated using Metaboanalyst software.

Table 2.

Important features of the tumor cell metabolism listed by fold change values and t-test P values. Intertumoral xylitol presents changes to the metabolic products that may influence tumor development. This table data was generated using Metaboanalyst software.

| Metabolite |

Fold Change |

log2(FC) |

P value |

| |

|

|

|

| L-tyrosine methyl ester |

0.13098 |

-2.9326 |

0.00055 |

| tryptamine |

0.43146 |

-1.2127 |

0.006415 |

| 2,3-bisphospho-D-glycerate |

0.34972 |

-1.5157 |

0.017592 |

| ATP / dGTP |

0.29392 |

-1.7665 |

0.019468 |

| cysteine |

0.54949 |

-0.86384 |

0.02808 |

| choline+ |

0.59869 |

-0.74012 |

0.032148 |

| GDP |

0.58635 |

-0.77016 |

0.03544 |

| 2- / 3-phosphoglycerate |

0.30686 |

-1.7044 |

0.037869 |

| glutathione |

0.42802 |

-1.2242 |

0.041884 |

| GAP / DHAP |

0.29889 |

-1.7423 |

0.041934 |

| D-erythrose-4-phosphate |

0.25721 |

-1.959 |

0.043739 |

| CDP |

0.34568 |

-1.5325 |

0.047149 |

| FAD |

0.3264 |

-1.6153 |

0.048366 |

| putrescine |

0.28675 |

-1.8022 |

0.048865 |

Figure 2.

a. Right legend: top 25 metabolic end products, Bottom legend: xylitol injected or vehicle-injected tumor. Significant differences in tumor metabolism with xylitol are present compared to the vehicle's. The xylitol group demonstrated significantly decreased phosphocreatine, citrate, and pyruvic acid levels, signifying metabolic stress within the tumor cells. Putrescine, mevalonic acid and tryptamine are elevated in the tumor cells.

Figure 2.

a. Right legend: top 25 metabolic end products, Bottom legend: xylitol injected or vehicle-injected tumor. Significant differences in tumor metabolism with xylitol are present compared to the vehicle's. The xylitol group demonstrated significantly decreased phosphocreatine, citrate, and pyruvic acid levels, signifying metabolic stress within the tumor cells. Putrescine, mevalonic acid and tryptamine are elevated in the tumor cells.

Figure 2.

b. This heatmap displays the top 50 metabolic end products in tumors treated with xylitol compared to the vehicle control. Significant differences are noted between metabolites of xylitol-treated tumors and the vehicle-treated tumors (P=0.05).

Figure 2.

b. This heatmap displays the top 50 metabolic end products in tumors treated with xylitol compared to the vehicle control. Significant differences are noted between metabolites of xylitol-treated tumors and the vehicle-treated tumors (P=0.05).

3.3. Histological Analysis

Histological analysis did not reveal overall and consistent differences between the xylitol and the vehicle groups. Indeed, the vehicle group demonstrated significant necrosis, perhaps due to the cancer growth. Tears or tracks were present in the xylitol samples, perhaps due to the xylitol injections. The vehicle injection group, however, did not demonstrate possible injection tracks (See Figures 3a and 3b).

Figure 3.

a. Xylitol-treated tumor histology demonstrates slight, patchy intratumoral necrosis (i.e., high viable fraction in the tumor). Foci of degeneration/necrosis are marked (asterisks). Several stromal blood vessels – overall vascularity in the cancer is modest (arrowheads), with occasionally small hemorrhages (arrow). The section is from mouse 754 with 20% xylitol injections. Tears or tracks may represent areas where xylitol injections were placed and resulted in solution loss.

Figure 3.

a. Xylitol-treated tumor histology demonstrates slight, patchy intratumoral necrosis (i.e., high viable fraction in the tumor). Foci of degeneration/necrosis are marked (asterisks). Several stromal blood vessels – overall vascularity in the cancer is modest (arrowheads), with occasionally small hemorrhages (arrow). The section is from mouse 754 with 20% xylitol injections. Tears or tracks may represent areas where xylitol injections were placed and resulted in solution loss.

Figure 3.

b. Vehicle-treated tumor representative image. Histology demonstrates extensive intratumoral necrosis (asterisks), resulting in ~60% viable fraction in tumor based solely on this image. Section from Mouse 765 with B16F10 melanoma tumor. Scattered stromal blood vessels are present, and overall vascularity in the tumor is low (arrows)—blood vessels in viable (solid arrow) and necrotic (open arrows) areas.

Figure 3.

b. Vehicle-treated tumor representative image. Histology demonstrates extensive intratumoral necrosis (asterisks), resulting in ~60% viable fraction in tumor based solely on this image. Section from Mouse 765 with B16F10 melanoma tumor. Scattered stromal blood vessels are present, and overall vascularity in the tumor is low (arrows)—blood vessels in viable (solid arrow) and necrotic (open arrows) areas.

4. Discussion

The previously published data suggests that xylitol inhibits cancer cell lines, although, in our study, tumor growth inhibition was only significant in the melanoma group (syngeneic model C57L/C, B16F10- innate immunity). Statistical differences were seen on days 5 and 14, with T-test analysis P value < .05. Cancer cells cannot utilize xylitol as can normal human cells (and rodents such as rats and mice) in their mitochondria for energy [

40]. Most cancer cells utilize glycolysis and mitochondrial metabolism to sustain growth in vivo [

41]. Certain animal species cannot correctly utilize xylitol, especially carnivores that have not been evolutionarily exposed to plants as foods [

42]. Tubers were once a significant source of food for homo sapiens and still a survivor food for hunter-gatherers, such as the Hadza tribe [

43,

44]. The microbiome of hunter-gatherers and traditional tribal people maintains specific bacterial taxa that can utilize complex carbohydrates and polyols [

45,

46]. One can theorize that homo sapiens cell mitochondria may have rapidly evolved to metabolize xylitol due to its presence in several survival foods, especially during periods of scarcity [

47]. Cockroaches, rats, swine, and humans can metabolize xylitol [

42,

43,

47].

Xylitol enhances the innate immune system response to cancer cells. Cancer cell lines are effectively more sensitive to Reactive Oxidative Species produced by the killer T-cells [

48]. Results from metabolomics support the theory. The metabolomic values were different between the vehicle and xylitol groups. Specifically, tumor cell production of glutathione and histamine was reduced by xylitol. Glutathione is an antioxidant that reduces the reactive oxygen species (ROS) effect on tumor cells [

49,

50]. Xylitol reduction of histamine may hypothetically reduce metastasis by reducing vascularization and proliferation [

51,

52]. In addition, mitochondrial metabolism is necessary to determine stem cell fate. Mitochondrial metabolism is responsible for the production of ATP and maintains the tri-carboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. The metabolites of the TCA cycle support stem cell survival and growth. Recent evidence shows that mitochondria control mammalian stem cells’ fate and function through reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, TCA cycle metabolite production, NAD+/NADH ratio regulation, pyruvate metabolism, and mitochondrial dynamics [

53]. Xylitol affects the mitochondria and the TCA cycle, apparently with anti-oncogenic properties.

Our first protocol utilized intra-tumor injections, which proved less effective due to loss of stroma. Lack of structural integrity, interstitial fluid pressure, and possibly tumor trauma resulted in xylitol solution leaking from the tumor, allowing for tumor progression [

54]. This exact mechanism was reported with previous intra-tumoral injections using chemotherapeutics, such as 5-fluorouracil, until the development of smart hydrogels [

55]. Studies in progress at the Developmental Therapeutics Core utilize Alzet mini osmotic pumps that deliver a consistent concentration of xylitol to the subject animals [

56,

57]. Our research team is now cautiously optimistic that this approach will advance techniques used in previously published studies with IV xylitol, which could be more challenging to implement in an animal group [

21].

The human microbiota and microbiome have many biological functions, including food digestion, synthesis of various vitamins, protection from pathogen colonization, and resistance against systemic infections [

58]. The gut microbiota also plays a crucial role in immune system development, and its alteration can cause immune dysregulation, which can lead to autoimmune diseases [

59]. The role of the microbiome in cancer development/progression via several mechanisms, including immune response modulation and the promotion of a pro-inflammatory tumor environment, has been very well studied and established [

60]. It has also been noted that xylitol significantly affects the composition of the gut microbiota, stimulates the propagation of beneficial bacteria, and produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) [

61,

62]. This altered metabolism of xenobiotic xylitol can potentially influence cancer growth and progression [

63].

Our study offers novel insights into the potential therapeutic role of xylitol in cancer treatment, specifically in melanoma. Treatment with a 20% xylitol solution demonstrated a significant reduction in the initial growth of B16F10 melanoma tumors in a syngeneic mouse model, highlighting xylitol's potential as an adjunctive treatment in oncology. Notably, this effect was only observed in the melanoma model, indicating a potential cancer-type specificity or differential mechanism of action. The efficacy of the xylitol injections decreased after five days in the BF16F10 model due to the degradation of melanoma tumor stroma, and the tumors re-commenced growth. Previous research suggests that a lower concentration of xylitol is more appropriate than concentrations above 5%. [

21].

The findings underscore the intricate relationship between metabolic interventions and tumor progression. Xylitol's impact on tumor metabolism, specifically its influence on reducing tumor cell production of crucial metabolites like histamine, NADP+, ATP, and glutathione, paves the way for further exploration into its role as a metabolic modulator in cancer therapy. This is particularly relevant given the growing interest in metabolic pathways as targets for cancer treatment. Moreover, the differential responses observed between the 4T1 mammary carcinoma and B16F10 melanoma models illuminate the complex nature of cancer biology and the necessity for targeted therapeutic strategies. Our study also brings to light the challenges associated with intratumoral drug delivery, as evidenced by the complications in maintaining the structural integrity of the tumor stroma during xylitol administration.

Future research should focus on optimizing the delivery method of xylitol to enhance its therapeutic efficacy. Extending these findings to other cancer models and eventually to clinical trials will be crucial to fully understanding xylitol's potential in cancer treatment. Our research lays the groundwork for such future investigations, with the hope of contributing to more effective and targeted cancer therapies.

5. Conclusions

Xylitol, a well-known natural sweetener and prebiotic, may be beneficial in reducing the growth of specific cancer cell lines, demonstrating a significant change in the tumor metabolism with the B16F10 syngeneic mouse model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C., and N.G.; methodology, N.G.; validation, A.C., formal analysis, N.C.; investigation, M.C.; resources, L.T.; data curation, L.T, N. C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; writing—review and editing; visualization, A.C.; supervision, M.C.; project administration, N.G.; funding acquisition, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Developmental Therapeutics Core at Northwestern University and the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center support grant (NCI CA060553). Funding was also provided by the Swanson Fund of Northwestern University, with special thanks to Michael Milligan, Lon Jones, and R. William Cornell for their contributions to the Swanson Fund.

Acknowledgments

Mari Tesch , Fernando Valerio-Pascua , and Franck Rahaghi, thank you for contributing to the manuscript.

Ethics Statement

This research was conducted in strict accordance with ethical standards and guidelines for animal experimentation. All procedures performed in animal studies complied with the ethical standards of the institution where the studies were conducted. Efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and reduce the number of animals used. The Institutional Animal Use and Control Committee approved the animal study protocol for Northwestern University, Center for Developmental Therapeutics. The IACUC protocol # is IS00009744.

Data Availability

All data is available at the Developmental Therapeutics Core and the Metabolomic Developing Core, Robert H Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center, Northwestern University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nayak, P. A., Nayak, U. A., & Khandelwal, V. (2014). The effect of xylitol on dental caries and oral flora. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dentistry, 6, 89–94. [CrossRef]

- Janakiram C., Deepan Kumar C. V., Joseph J., Xylitol in preventing dental caries: A systematic review and meta-analyses. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2017 Jan-Jun; 8(1): 16–21.

- Kõljalg S, Smidt I, Chakrabarti A, Bosscher D, Mändar R. Exploration of singular and synergistic effect of xylitol and erythritol on causative agents of dental caries. Sci Rep. 2020 Apr 14;10(1):6297. PMID: 32286378; PMCID: PMC7156733. [CrossRef]

- Mäkinen KK (2017) Sugar alcohols and prevention of oral diseases – comments and rectifications. Oral Health Care 2:. [CrossRef]

- Salli, K., Lehtinen, M. J., Tiihonen, K., & Ouwehand, A. C. (2019). Xylitol's Health Benefits beyond Dental Health: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients, 11(8), 1813. [CrossRef]

- de Cock P. Erythritol Functional Roles in Oral-Systemic Health. Adv Dent Res. 2018 Feb;29(1):104-109. PMID: 29355425. [CrossRef]

- Bettina K. Wölnerhanssen, Anne Christin Meyer-Gerspach, Christoph Beglinger & Md. Shahidul Islam (2020) Metabolic effects of the natural sweeteners’ xylitol and erythritol: A comprehensive review, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 60:12, 1986-1998. [CrossRef]

- Cannon ML, Merchant M, Kabat W, Catherine L, White K, Unruh B, Ramones A. In Vitro Studies of Xylitol and Erythritol Inhibition of Streptococcus Mutans and Streptococcus Sobrinus Growth and Biofilm Production. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2020 Sep 1;44(5):307-314. PMID: 33181842. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez M.C., Romero-Lastra P., Ribeiro-Vidal H., et al. Comparative gene expression analysis of planktonic Porphyromonas gingivalis ATCC 33277 in the presence of a growing biofilm versus planktonic cells. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19(1):58. Published 2019 Mar 12. [CrossRef]

- Badet C., Furiga A., Thébaud N. Effect of xylitol on an in vitro model of oral biofilm. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2008;6(4):337-41.

- Marleen Marga Janus, Catherine Minke Charlotte Volgenant, Bernd Willem Brandt, Mark Johannes Buijs, Bart Jan Frederik Keijser, Wim Crielaard, Egija Zaura & Bastiaan Philip Krom (2017) Effect of erythritol on microbial ecology of in vitro gingivitis biofilms, Journal of Oral Microbiology, 9:1. [CrossRef]

- Söderling E., Hietala, Lenkkeri A.M. (2010) Xylitol and erythritol decrease adherence of polysaccharide-producing oral streptococci. Curr Microbiol 60: 22-29.

- S. Ferreira, Aline; F. Silva-Paes-Leme, Annelisa; R.B. Raposo, Nadia; S. da Silva, Silvio. By Passing Microbial Resistance: Xylitol Controls Microorganisms Growth by Means of Its Anti-Adherence Property. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, Volume 16, Number 1, January 2015, pp. 35-42(8).

- Bahador, A., Lesan, S., & Kashi, N. (2012). Effect of xylitol on cariogenic and beneficial oral streptococci: a randomized, double-blind crossover trial. Iranian journal of microbiology, 4(2), 75–81.

- Meng, C., Bai, C., Brown, T. D., Hood, L. E., & Tian, Q. (2018). Human Gut Microbiota and Gastrointestinal Cancer. Genomics, proteomics & bioinformatics, 16(1), 33–49. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y. L., Lin, T. L., Chang, C. J., Wu, T. R., Lai, W. F., Lu, C. C., & Lai, H. C. (2019). Probiotics, prebiotics and amelioration of diseases. Journal of biomedical science, 26(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M. K., Kumari, I., Singh, B., Sharma, K. K., & Tiwari, S. K. (2022). Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics: Safe options for next-generation therapeutics. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 106(2), 505–521. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C. B., Zhou, Y. L., & Fang, J. Y. (2021). Gut Microbiota in Cancer Immune Response and Immunotherapy. Trends in cancer, 7(7), 647–660. [CrossRef]

- Ting, N. L., Lau, H. C., & Yu, J. (2022). Cancer pharmacomicrobiomics: targeting microbiota to optimise cancer therapy out-comes. Gut, 71(7), 1412–1425. [CrossRef]

- Park, E., Park, M. H., Na, H. S., & Chung, J. (2015). Xylitol induces cell death in lung cancer A549 cells by autophagy. Bio-technology letters, 37, 983-990.

- Tomonobu, N., Komalasari, N. L. G. Y., Sumardika, I. W., Jiang, F., Chen, Y., Yamamoto, K. I., ... & Sakaguchi, M. (2020). Xylitol acts as an anticancer monosaccharide to induce selective cancer death via regulation of the glutathione level. ChemicoBiological Interactions, 324, 109085.

- Sahasakul, Y., Angkhasirisap, W., Lam-Ubol, A., Aursalung, A., Sano, D., Takada, K., & Trachootham, D. (2022). Partial Substitution of Glucose with Xylitol Prolongs Survival and Suppresses Cell Proliferation and Glycolysis of Mice Bearing Orthotopic Xenograft of Oral Cancer. Nutrients, 14(10), 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mehnert, H., Förster, H., & Dehmel, K. H. (1969). The effect of intravenous administration of xylitol solutions in normal persons and in patients with liver diseases and diabetes mellitus. In International Symposium on Metabolism, Physiology, and Clinical Use of Pentoses and Pentitols: Hakone, Japan, August 27th–29th, 1967 (pp. 293-302). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Sato, J., Wang, Y. M., & van Eys, J. (1981). Metabolism of xylitol and glucose in rats bearing hepatocellular carcinomas. Cancer Research, 41(8), 3192-3199.

- Yi, E. Y., & Kim, Y. J. (2013). Xylitol inhibits in vitro and in vivo angiogenesis by suppressing the NF-κB and Akt signaling pathways. International Journal of Oncology, 43(1), 315-320.

- Ylikahri, R. H., & Leino, T. (1979). Metabolic interactions of xylitol and ethanol in healthy males. Metabolism: clinical and experimental, 28(1), 25–29. [CrossRef]

- Hutchenson, R. M., Reynolds, V. H., & Touster, O. (1956). The reduction of L-xylulose to xylitol by guinea pig liver mitochondria. The Journal of biological chemistry, 221(2), 697–709.

- Ahuja, V., Macho, M., Ewe, D., Singh, M., Saha, S., & Saurav, K. (2020). Biological and Pharmacological Potential of Xylitol: A Molecular Insight of Unique Metabolism. Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 9(11), 1592. [CrossRef]

- Islam M. S. (2011). Effects of xylitol as a sugar substitute on diabetes-related parameters in nondiabetic rats. Journal of medicinal food, 14(5), 505–511. [CrossRef]

- Wada, T., Sumardika, I. W., Saito, S., Ruma, I. M. W., Kondo, E., Shibukawa, M., & Sakaguchi, M. (2017). Identification of a novel component leading to anti-tumor activity besides the major ingredient cordycepin in Cordyceps militaris extract. Journal of chromatography. B, Analytical technologies in the biomedical and life sciences, 1061-1062, 209–219. [CrossRef]

- Park, E., Na, H. S., Kim, S. M., Wallet, S., Cha, S., & Chung, J. (2014). Xylitol, an anticaries agent, exhibits potent inhibition of inflammatory responses in human THP-1-derived macrophages infected with Porphyromonas gingivalis. Journal of periodontology, 85(6), e212–e223. [CrossRef]

- Trachootham, D., Chingsuwanrote, P., Yoosadiang, P., Mekkriangkrai, D., Ratchawong, T., Buraphacheep, N., ... & Tuntipopipat, S. (2017). Partial substitution of glucose with xylitol suppressed the glycolysis and selectively inhibited the proliferation of oral cancer cells. Nutrition and cancer, 69(6), 862-872.

- Qusa, M. H., Siddique, A. B., Nazzal, S., & El Sayed, K. A. (2019). Novel olive oil phenolic (−)-oleocanthal (+)-xylitol-based solid dispersion formulations with potent oral anti-breast cancer activities. International journal of pharmaceutics, 569, 118596.

- Ireson, C. R., Alavijeh, M. S., Palmer, A. M., Fowler, E. R., & Jones, H. J. (2019). The role of mouse tumour models in the discovery and development of anticancer drugs. British journal of cancer, 121(2), 101-108.

- Rinschen, M. M., Ivanisevic, J., Giera, M., & Siuzdak, G. (2019). Identification of bioactive metabolites using activity metabolomics. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology, 20(6), 353–367. [CrossRef]

- Vander Heiden, M. G., & DeBerardinis, R. J. (2017). Understanding the Intersections between Metabolism and Cancer Biology. Cell, 168(4), 657–669. [CrossRef]

- Vernieri, C., Casola, S., Foiani, M., Pietrantonio, F., de Braud, F., & Longo, V. (2016). Targeting Cancer Metabolism: Dietary and Pharmacologic Interventions. Cancer discovery, 6(12), 1315–1333. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, DR, Patel, R, Kirsch, DG, Lewis, CA, Vander Heiden, MG, Locasale, JW. Metabolomics in cancer research and emerging applications in clinical oncology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Lofgren J, Miller AL, Lee CCS, Bradshaw C, Flecknell P, Roughan J. Analgesics promote welfare and sustain tumor growth in orthotopic 4T1 and B16 mouse cancer models. Laboratory Animals. 2018;52(4):351-364. [CrossRef]

- Ylikahri R. (1979). Metabolic and nutritional aspects of xylitol. Advances in food research, 25, 159–180. [CrossRef]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Chandel NS. We need to talk about the Warburg effect. Nat Metab. 2020 Feb;2(2):127-129. PMID: 32694689. [CrossRef]

- Cortinovis, C., & Caloni, F. (2016). Household Food Items Toxic to Dogs and Cats. Frontiers in veterinary science, 3, 26. [CrossRef]

- Iannotti, L. L., Gyimah, E. A., Reid, M., Chapnick, M., Cartmill, M. K., Lutter, C. K., Hilton, C., Gildner, T. E., & Quinn, E. A. (2022). Child dietary patterns in Homo sapiens evolution: A systematic review. Evolution, medicine, and public health, 10(1), 371–390. [CrossRef]

- Marlowe, F. W., & Berbesque, J. C. (2009). Tubers as fallback foods and their impact on Hadza hunter-gatherers. American journal of physical anthropology, 140(4), 751–758. [CrossRef]

- Olm, M. R., Dahan, D., Carter, M. M., Merrill, B. D., Yu, F. B., Jain, S., Meng, X., Tripathi, S., Wastyk, H., Neff, N., Holmes, S., Sonnenburg, E. D., Jha, A. R., & Sonnenburg, J. L. (2022). Robust variation in infant gut microbiome assembly across a spec-trum of lifestyles. Science (New York, N.Y.), 376(6598), 1220–1223. [CrossRef]

- De Filippo, C., Cavalieri, D., Di Paola, M., Ramazzotti, M., Poullet, J. B., Massart, S., Collini, S., Pieraccini, G., & Lionetti, P. (2010). Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(33), 14691–14696. [CrossRef]

- Marean C. W. (2010). When the sea saved humanity. Scientific American, 303(2), 54–61. [CrossRef]

- Trachootham, D., Alexandre, J., & Huang, P. (2009). Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach?. Nature reviews. Drug discovery, 8(7), 579–591. [CrossRef]

- Niu, B., Liao, K., Zhou, Y., Wen, T., Quan, G., Pan, X., & Wu, C. (2021). Application of glutathione depletion in cancer therapy: Enhanced ROS-based therapy, ferroptosis, and chemotherapy. Biomaterials, 277, 121110. [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y., Chen, H., Zhang, L., Wu, M., Zhang, F., Yang, D., Shen, J., & Chen, J. (2021). Glycyrrhetinic acid induces oxidative/nitrative stress and drives ferroptosis through activating NADPH oxidases and iNOS, and depriving glutathione in tri-ple-negative breast cancer cells. Free radical biology & medicine, 173, 41–51. [CrossRef]

- Hellstrand, K., Brune, M., Naredi, P., Mellqvist, U. H., Hansson, M., Gehlsen, K. R., & Hermodsson, S. (2000). Histamine: a novel approach to cancer immunotherapy. Cancer investigation, 18(4), 347–355. [CrossRef]

- Stoyanov, E., Uddin, M., Mankuta, D., Dubinett, S. M., & Levi-Schaffer, F. (2012). Mast cells and histamine enhance the proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Lung cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 75(1), 38–44. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, R. P., & Chandel, N. S. (2021). Mitochondria as Signaling Organelles Control Mammalian Stem Cell Fate. Cell stem cell, 28(3), 394–408. [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, T. G., Gaustad, J. V., Leinaas, M. N., & Rofstad, E. K. (2012). High interstitial fluid pressure is associated with tumor-line specific vascular abnormalities in human melanoma xenografts. PloS one, 7(6), e40006. [CrossRef]

- Shin, G. R., Kim, H. E., Kim, J. H., Choi, S., & Kim, M. S. (2021). Advances in Injectable In Situ-Forming Hydrogels for Intra-tumoral Treatment. Pharmaceutics, 13(11), 1953. [CrossRef]

- Gould, H. J., 3rd, & Paul, D. (2022). Targeted Osmotic Lysis: A Novel Approach to Targeted Cancer Therapies. Biomedicines, 10(4), 838. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. X., Liu, W. J., Zhang, H. R., & Zhang, Z. W. (2018). Delivery of bevacizumab by intracranial injection: assessment in glioma model. OncoTargets and therapy, 11, 2673–2683. [CrossRef]

- Algrafi, A. S., Jamal, A. A., & Ismaeel, D. M. (2023). Microbiota as a New Target in Cancer Pathogenesis and Treatment. Cu-reus, 15(10), e47072. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. J., & Wu, E. (2012). The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Gut microbes, 3(1), 4–14. [CrossRef]

- Halley, A., Leonetti, A., Gregori, A., Tiseo, M., Deng, D. M., Giovannetti, E., & Peters, G. J. (2020). The Role of the Microbiome in Cancer and Therapy Efficacy: Focus on Lung Cancer. Anticancer research, 40(9), 4807–4818. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Q. L., Cai, X., Zheng, X. Y., Chen, D. S., Li, M., Liu, Z. Q., Chen, K. Q., Han, F. F., & Zhu, X. (2021). Influences of Xylitol Consumption at Different Dosages on Intestinal Tissues and Gut Microbiota in Rats. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 69(40), 12002–12011. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S., Ye, K., Li, M., Ying, J., Wang, H., Han, J., Shi, L., Xiao, J., Shen, Y., Feng, X., Bao, X., Zheng, Y., Ge, Y., Zhang, Y., Liu, C., Chen, J., Chen, Y., Tian, S., & Zhu, X. (2021). Xylitol enhances synthesis of propionate in the colon via cross-feeding of gut microbiota. Microbiome, 9(1), 62. [CrossRef]

- Koppel, N., Maini Rekdal, V., & Balskus, E. P. (2017). Chemical transformation of xenobiotics by the human gut microbiota. Science (New York, N.Y.), 356(6344), eaag2770. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).