1. Introduction

The crystal structures of many common xanthine alkaloids with important pharmacological properties have been extensively studied both experimentally and computationally [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Caffeine has been of particular interest to researchers since well-ordered anhydrous crystalline forms are elusive, and various studies of its polymorphism [

6,

7,

8] and co-crystal formation to avoid its tendency to hydration [

9,

10] have appeared. Furthermore, its cocrystals with various flavonoids have been the basis for separation based on differential solubility [

11]. We were interested to explore alkaloid: flavonoid cocrystal formation in a broader sense and screened for co-crystal formation from common alkaloid and flavonoid compounds. In addition to caffeine (Caf) which is 1,3,7-trimethylxanthine, the related alkaloids theophylline (Tph) which is 1,3-dimethylxanthine and theobromine (Tbr) which is 3,7-dimethylxanthine were also investigated.

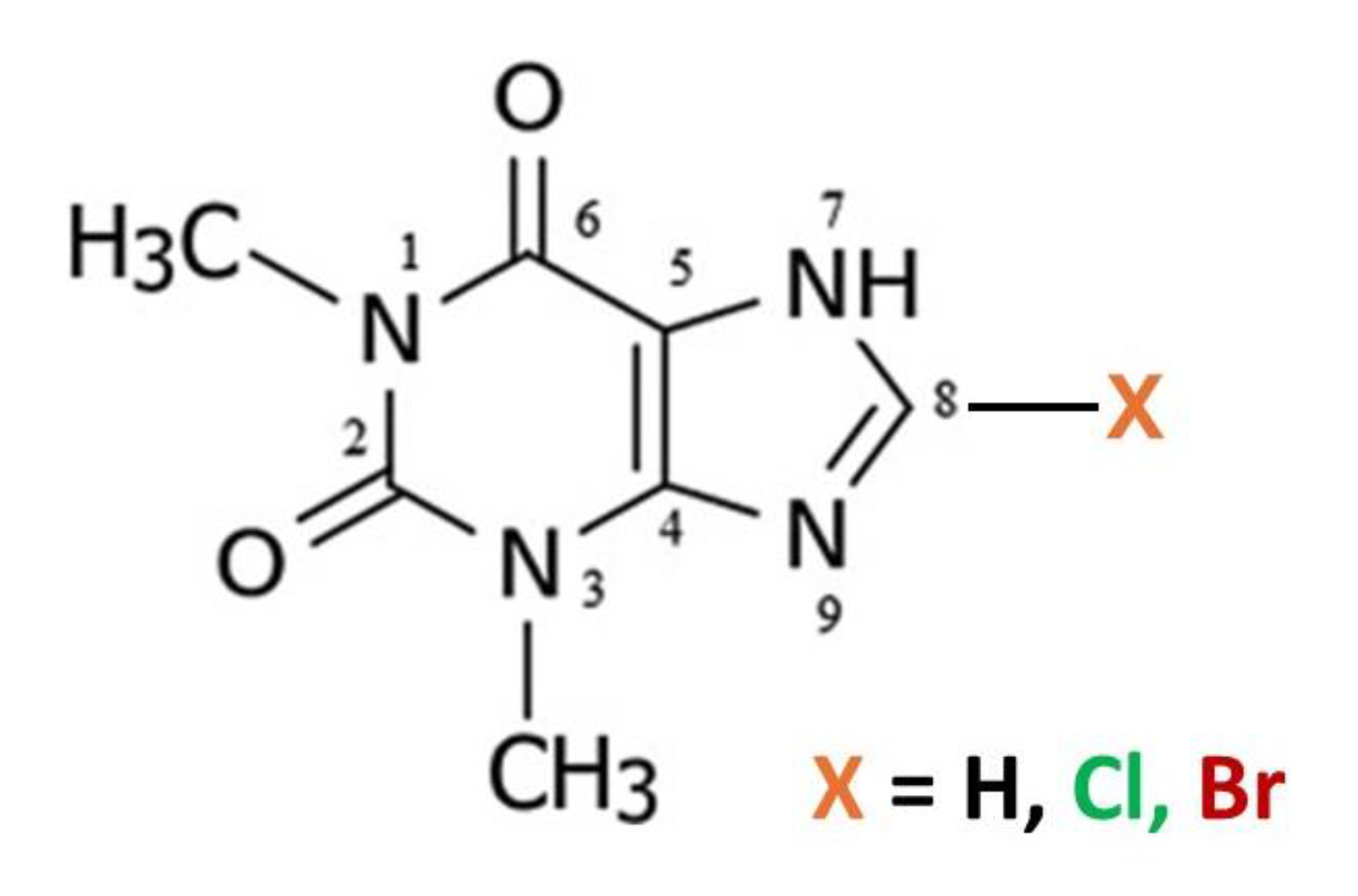

Two simple 8-halo substituted theophyllines, 8-chlorotheophylline (8-Cl-Tph) and 8-bromotheophylline (8-Br-Tph) were also commercially available and thus included in our studies. Neither 8-halo-Tph had a crystal structure previously reported in the Cambridge Structural Database. This was rather surprising in the case of 8-Cl-Tph, since it is a well-known component of Dramamine, (Dimenhydrinate) in which it serves as the anion in a 1:1 salt with diphenhydramine and for which the crystal structure was only recently determined [

12]. Since we wished to compare specific volumes for cocrystals with parent co-formers, we undertook to carry out the crystal structure determinations of both 8-Cl-Tph and 8-Br-Tph, as well as structure re-determination for Tph with all measured at 100K. Through use of differing crystallization conditions, we have uncovered three polymorphic forms of 8-Cl-Tph and two for 8-Br-Tph, all of which we report herein. Only one pair of these structures are isostructural and they are also distinct from the five previously reported Tph polymorphs [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Hence a total of nine distinct packing arrangements have now been uncovered for these simple theophylline alkaloid molecules.

2. Materials and Methods

Theophylline alkaloids and solvents used were of reagent grade supplied by Meryer Chemicals, (Shanghai) with following details: Theophylline, 99% CAS 58-55-9, C

7H

8N

4O

2, Mw: 180.17; 8-chlorotheophylline >98%, CAS 85-18-7, C

7H

7ClN

4O

2, Mw: 214.61; 8-bromotheophylline 97%, CAS 10381-75-6, C

7H

7BrN

4O

2, Mw: 259.06. All new cocrystal phases can be obtained from liquid assisted grinding (LAG) [

21], using a Tencan XQM-0.4A mini-planetary ball mill with zirconia vessels and media. A minimal amount of methanol (η factor = 0.2 mL/g) was used to accelerate the solid-state transformations which took between 30 min to 2 h [

22].

Crystal polymorphs were obtained by heating/ cooling methanolic solutions of the compounds at varying temperature, or hydrates via solvent evaporation at room temperature. Solid-solutions were prepared through common dissolution/ reprecipitation from 50:50 mixtures from MeOH. Specimen size ranged from 80-250 micron.

X-Ray Crystallography

Powder X-ray diffraction data were obtained on crystalline powders at room temperature using Cu-Kα radiation by a PanAlytical X’Pert PRO diffractometer with 1D X’celerator detector or on a PanAlytical Aeris benchtop powder X-ray diffractometer and measured in 2θ range 5 to 30

o with step size of 0.02

o. Single crystal X-ray structure determinations of the various polymorphs and solid solutions of Tph, 8-Cl-Tph and 8-Br-Tph were carried out at 100 K on a Rigaku-Oxford Diffraction Supernova operating with micro-focus Cu-Kα or Mo- Kα sources and Atlas detector, or on a Bruker Metal-jet with Ga- Kα source. The structures were solved and refined using embedded SHELX programs [

23,

24] or internal options from within the Olex2 suite [

25,

26].

Structures refined successfully with solutions showing R-values typically between 2 and 4%. Bond length standard deviations were acceptably low (0.002-0.003Å) and residual electron density was low except for absorption features associated with Br atoms, which were kept below 1.0e Å-3. No disorder of non-hydrogen atoms appeared present in these phases, except in the case of a Cl/Br solid-solution. Organic C-H hydrogens were placed geometrically with riding constraints and ADPs derived from the C atoms to which they were attached. All -CH and CH2 groups had H-Uiso fixed at 1.2 times the C atom. Methyls were idealized as freely rotating CH3 groups with H-Uiso fixed at 1.5 times that of the C atom. In some cases, these were split into two rotationally staggered orientations. Hydrogens on heteroatoms NH and OH (theophylline hydrate) were refined as independent isotropic atoms.

Computational Methods

All DFT calculations carried out on theophylline molecule (and derivatives) were performed using the Gaussian 09 program [

27]. The ωB97X-D functional [

28] was chosen for the DFT calculations. The def2-TZVP basis set [

29] (together with the built-in effective core potentials when present) was used to describe all the atoms in the calculations. The partial charges are estimated with two different schemes: (1) Natural charges and the Wiberg bond index [

30] in the natural atomic orbital basis are calculated using the calculated by the Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) method [

31] embedded in Gaussian 09, and (2) the electrostatic potential-derived charges are calculated according to the Merz-Singh-Kollman [

32,

33] scheme in Gaussian 09.

3. Results

Summary details of the crystal structure determinations for Tph, 8-Cl-Tph and 8-Br-Tph are given in

Table 1 for the various polymorphs. Unit cell data for the previously reported phases of Tph and Tph.H

2O also measured at 100K are included for comparison.

3.1. Polymorphic Forms of Theophylline

The polymorphs of anhydrous theophylline have been the subject of considerable previous study [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. To-date five distinct polymorphic forms have been identified and a monohydrate not readily suppressed with ambient crystallization. Form I is the thermodynamically stable form above 232

oC with related Form II more stable at ambient temperature. Form III is clearly metastable with poor packing efficiency and its formation and structure was established by Madsen after desolvation of the common monohydrate form [

18]. Form IV has been regarded as the most thermodynamically favored form to-date [

19].

In our own work we have tried crystallization of theophylline from ambient solvent evaporation methods, which has typically afforded the monohydrate or a mixture of phase types. The use of higher temperature crystallizations is helpful in suppressing formation of solvate and hydrated phases and at 80

oC from ethanol-water Form-II is isolated and high temperature (solvothermal) from methanol affords the more recently isolated Form-V [

20]. Our structure redetermination of this indicates that this phase is certainly energetically competitive, with a specific molar volume of 195.5Å

3, which is essentially identical with our Form-II and with only the 100K structure from Form-IV clearly giving a smaller specific molecular volume.

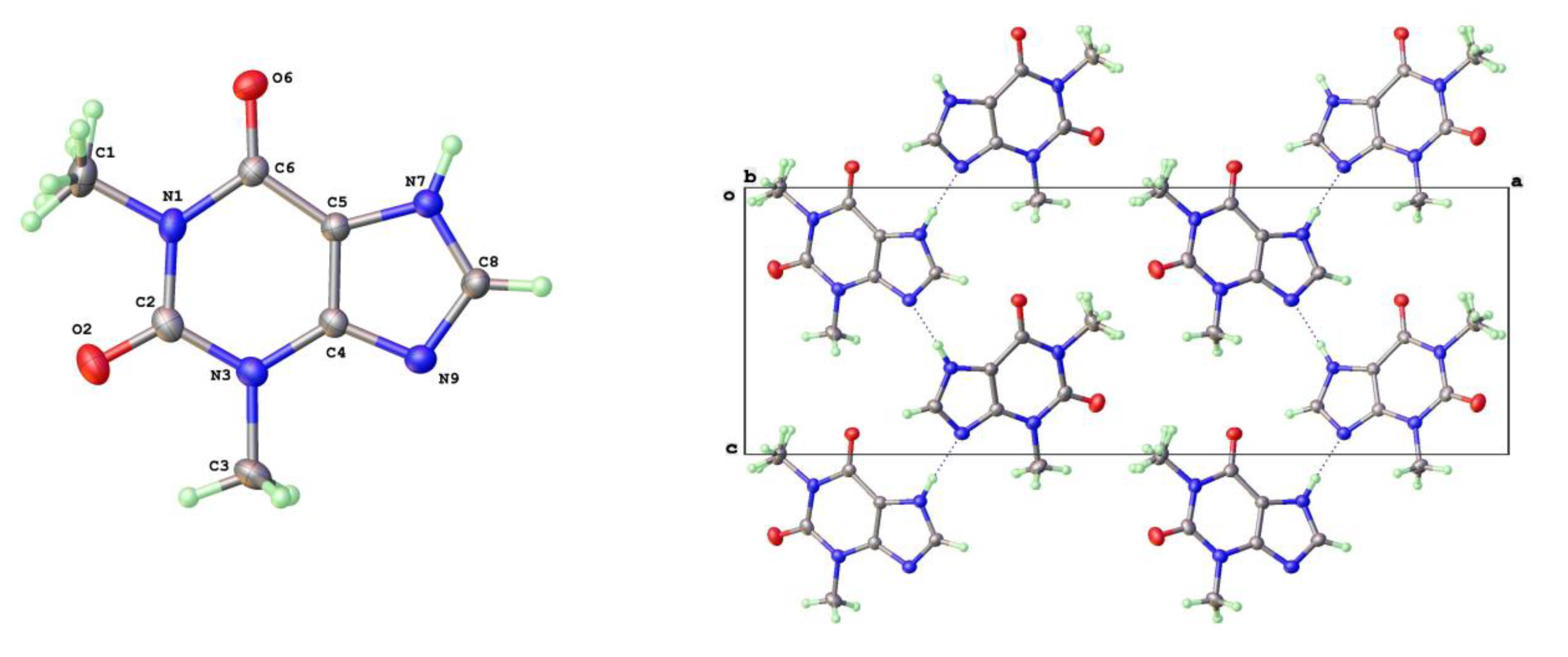

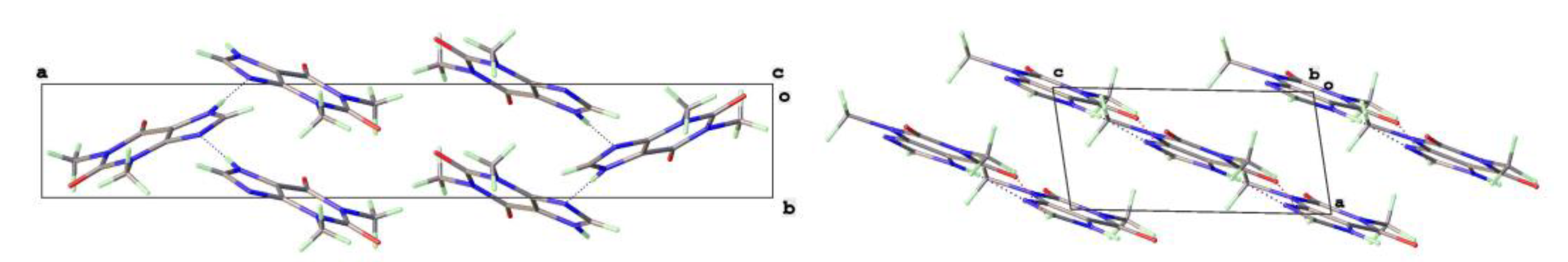

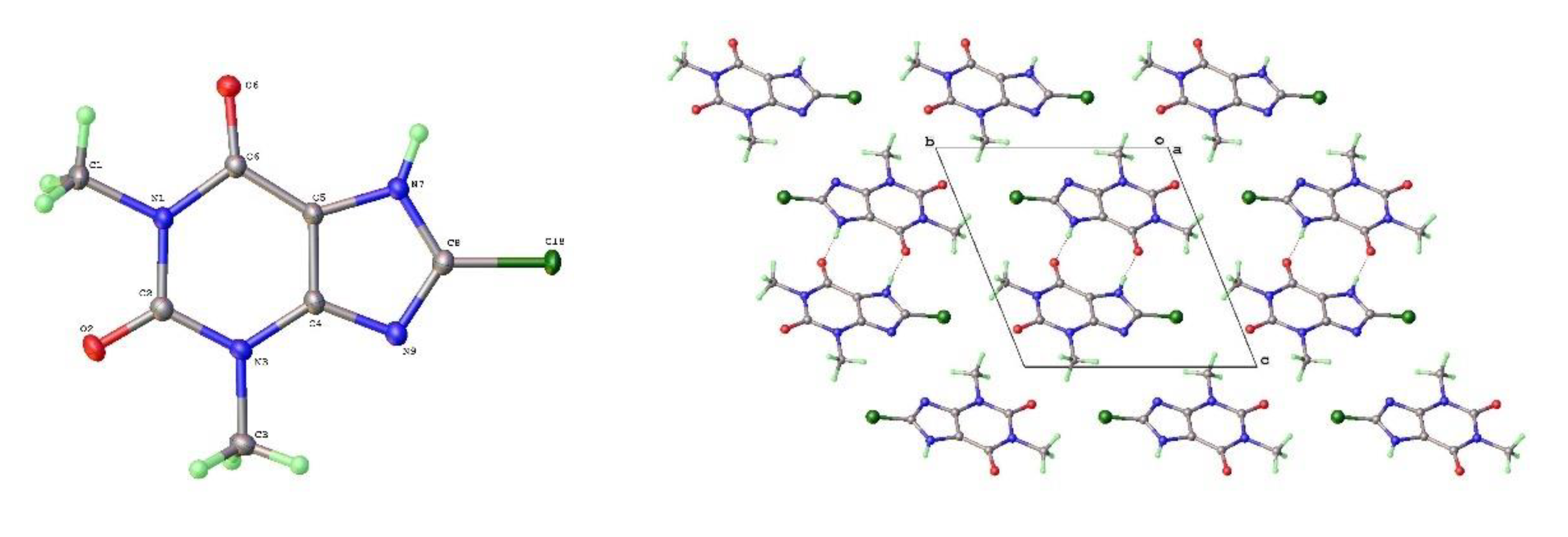

Descriptions of the theophylline polymorphic forms have been reported elsewhere but it is instructive to consider here the three phase types we have isolated for later comparison with the 8-halo analogues. The Form-II anhydrous theophylline [

14,

17] is readily crystallized using slightly higher temperature of crystallization, such as from hot aqueous ethanol. It consists of zigzag linear chains of theophylline molecules screw related along the c-axis and connected via N(7)-H(7)---N(9) hydrogen bonds (N---N = 2.782(3)Å). The molecular labelling scheme and packing diagram viewed along the short b-axis [010] are shown in

Figure 2.

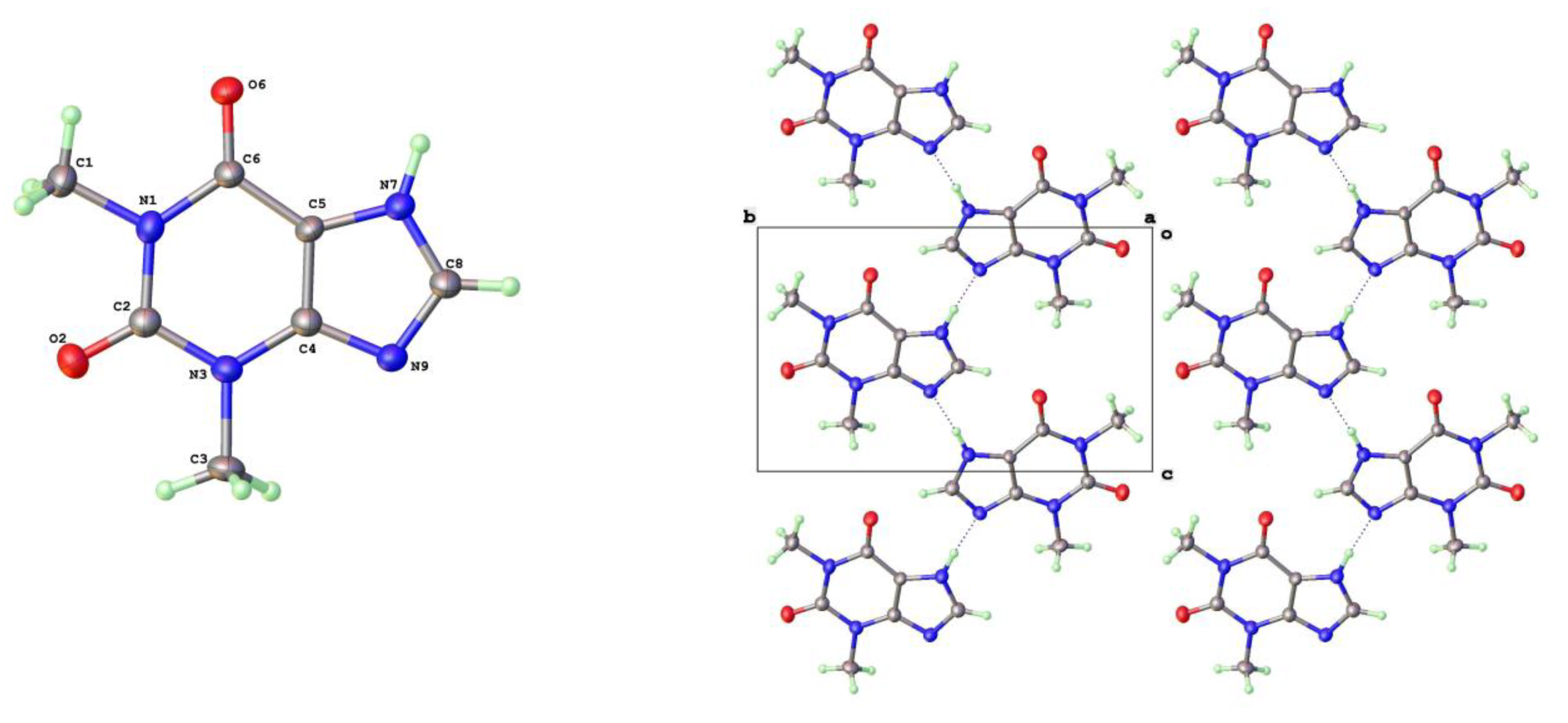

Crystals of Form V were formed using higher temperature solvothermal crystal growth from methanol (140

oC). This is somewhat related to the use of DMF by Dvulgerov et al. in attempted crystallization of a theophylline containing metal organic framework material [

20]. The molecular structure and packing diagram for Form V are shown in

Figure 3. The packing density of Forms II and V are essentially identical and the projections along the short axes look extremely similar. The hydrogen bond geometry in Form V is once again based on N(7)-H(7)---N(9) with a slightly longer N---N separation of 2.820(3)Å

The key difference between the two forms can be seen in

Figure 4, which shows the hydrogen bond strands for Form II have a zigzag arrangement of molecular planes, whilst in Form V the theophylline molecules in each strand are essentially coplanar.

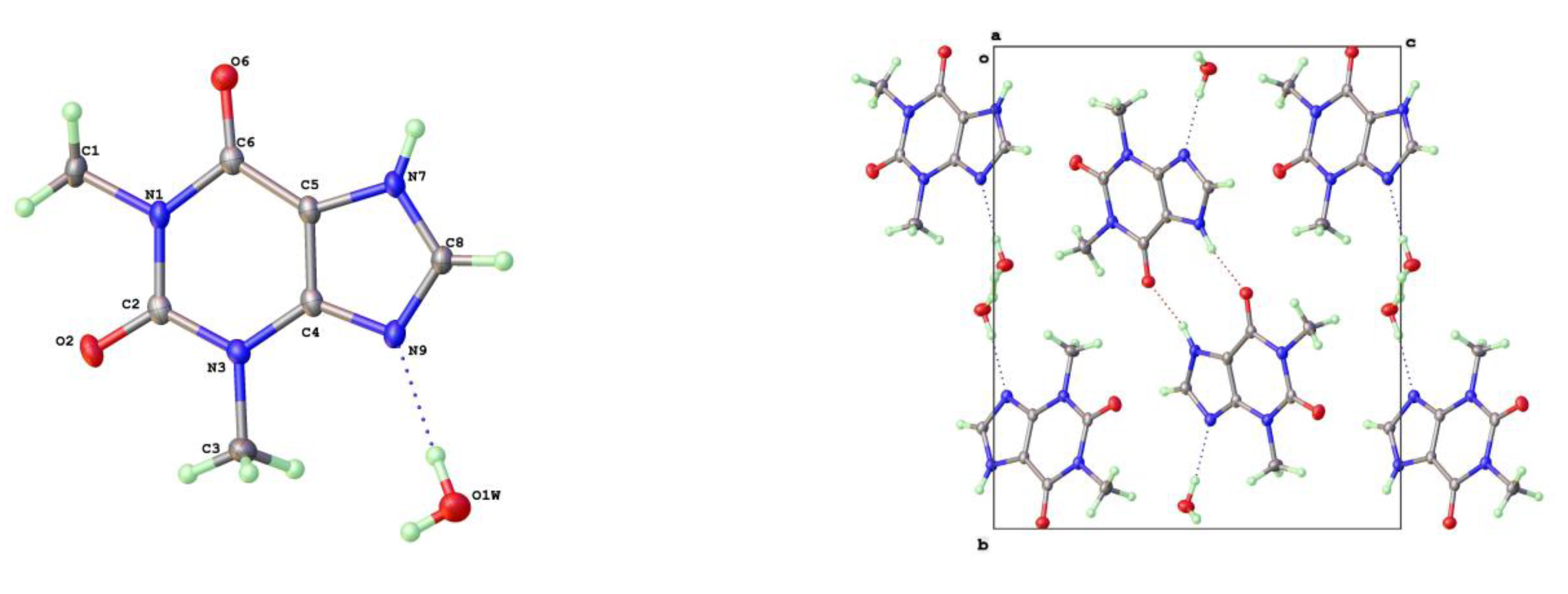

The theophylline monohydrate is readily formed under ambient growth conditions if water is not excluded. The structure is monoclinic P2

1/n with 1-D water channels showing statistical disorder of hydrogen atoms, as previously reported [

17]. The water hydrogen bonds to itself up and down the channel stack as well as to the alkaloid base nitrogen N(9). The N(7)-H(7) forms a hydrogen bond to O(6) keto oxygen (2.754Å) such that the two theophyllines form a dimer R

22(10) in Etter graph set notation [

34]. This dimer motif is anticipated as the most likely molecular aggregation in concentrated aqueous solutions of theophylline and has been examined computationally [

35].

3.2. Polymorphic Forms of 8-Halotheophylline

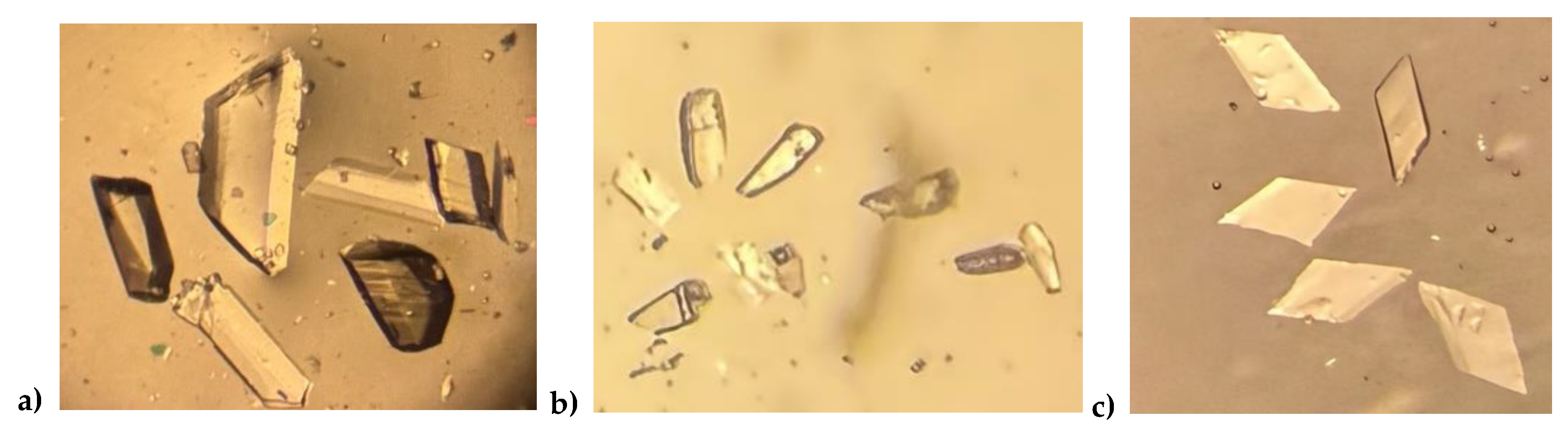

The lack of reported polymorphic forms for the substituted alkaloids 8-chloro and 8-bromotheophylline prompted us to investigate their crystal structures. Given the rich diversity of theophylline structures discussed here, along with the common isolation of theophylline monohydrate, we anticipated that the halo substitutions would likely alter the existing polymorphic energies and potentially alter the stability ranking of these solid structures, or even give rise to new ones. Material of 8-chlorotheophylline as received gave a reasonable powder X-ray diffraction pattern, but Thermal Gravimetric Analysis indicated it was an anhydrous form – we have named this Form-I. Recrystallization from methanol at 140

oC afforded acceptable single crystals of Form-I 8-Cl-Tph, (

Figure 6a) these are monoclinic whereas crystallization from various aprotic solvents gave triclinic Form-II (

Figure 6b) A third form 8-Cl-Tph Form-III involving molcular dimers (

Figure 6c) with a platy rhombus crystal habit was isolated from attempted co-crystalliztion with rutin, but have not yet been prepared in a phase pure manner by a more rational methodology.

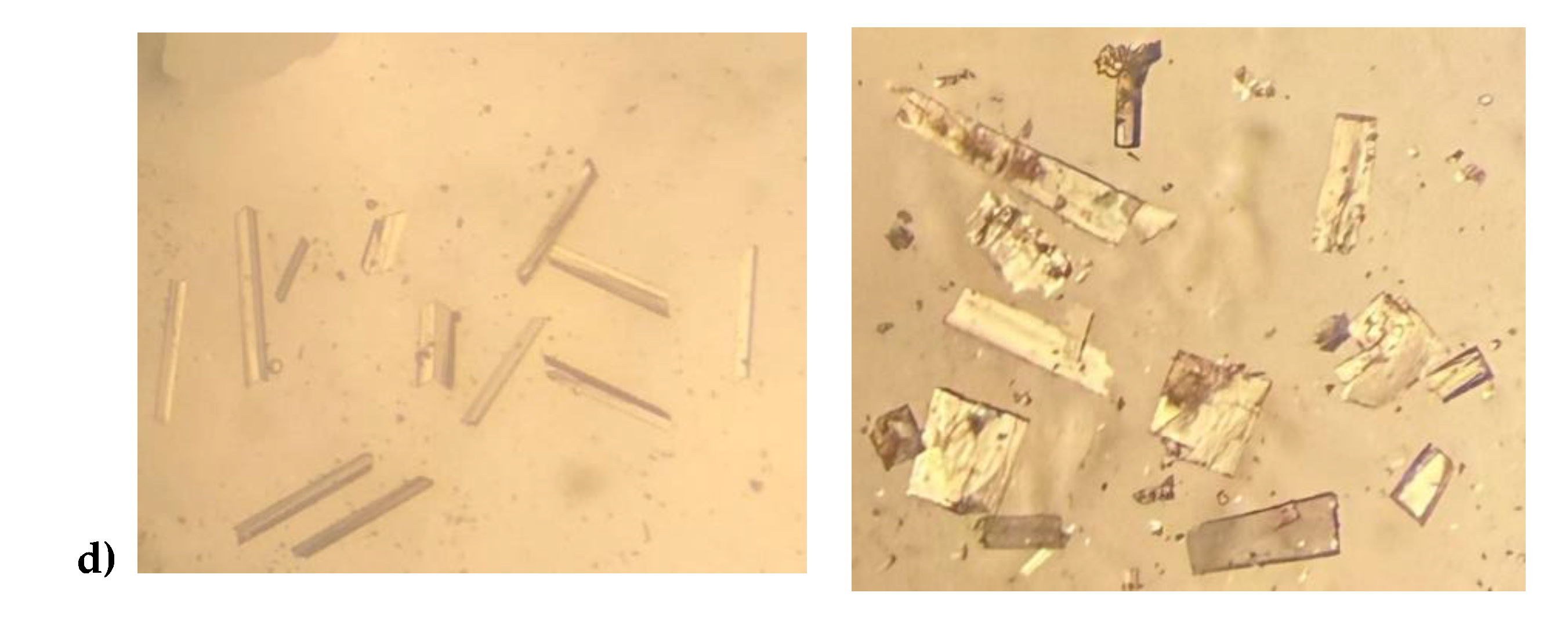

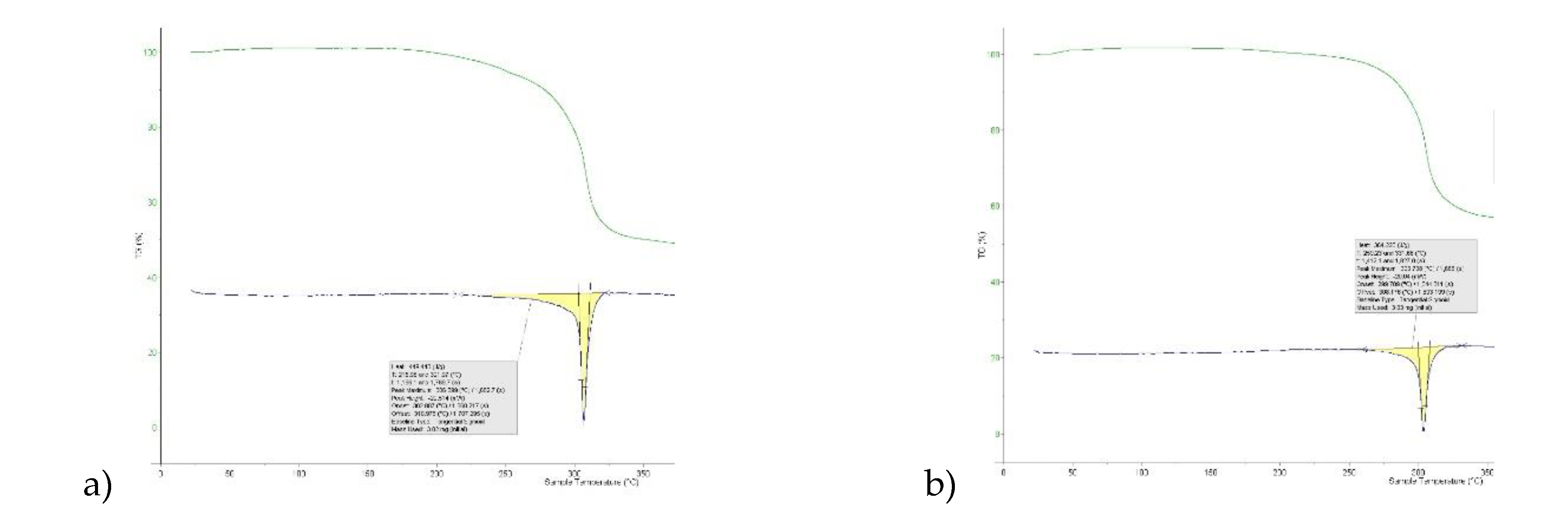

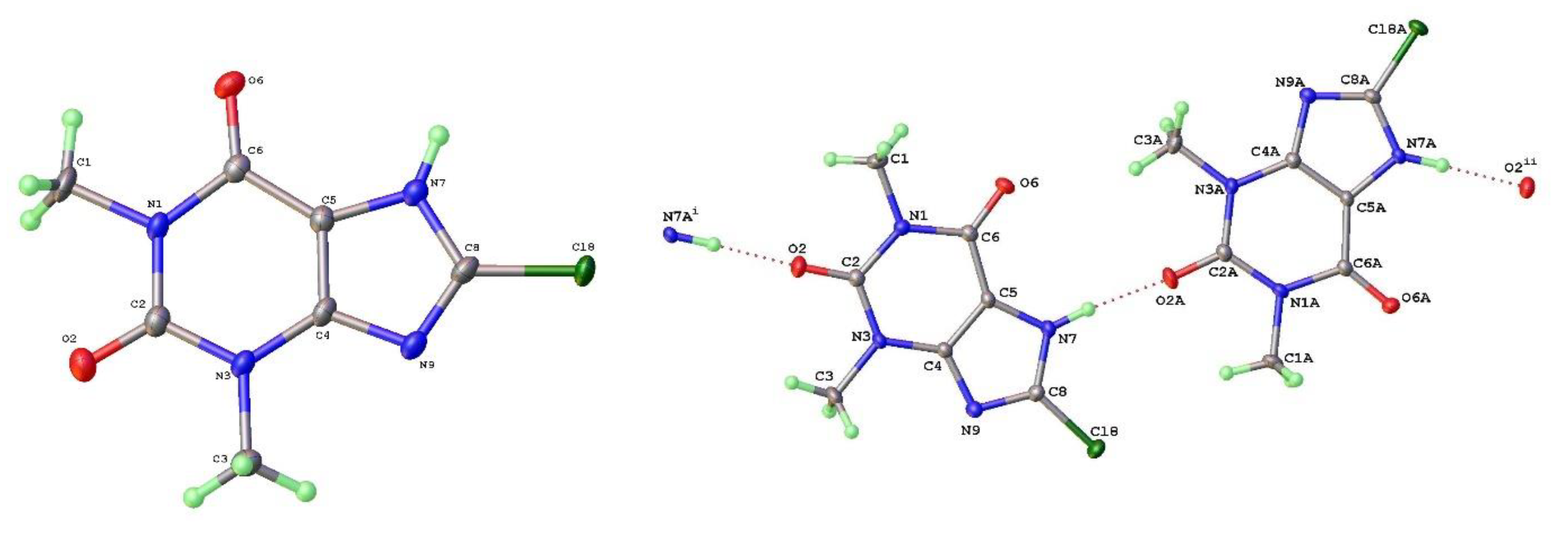

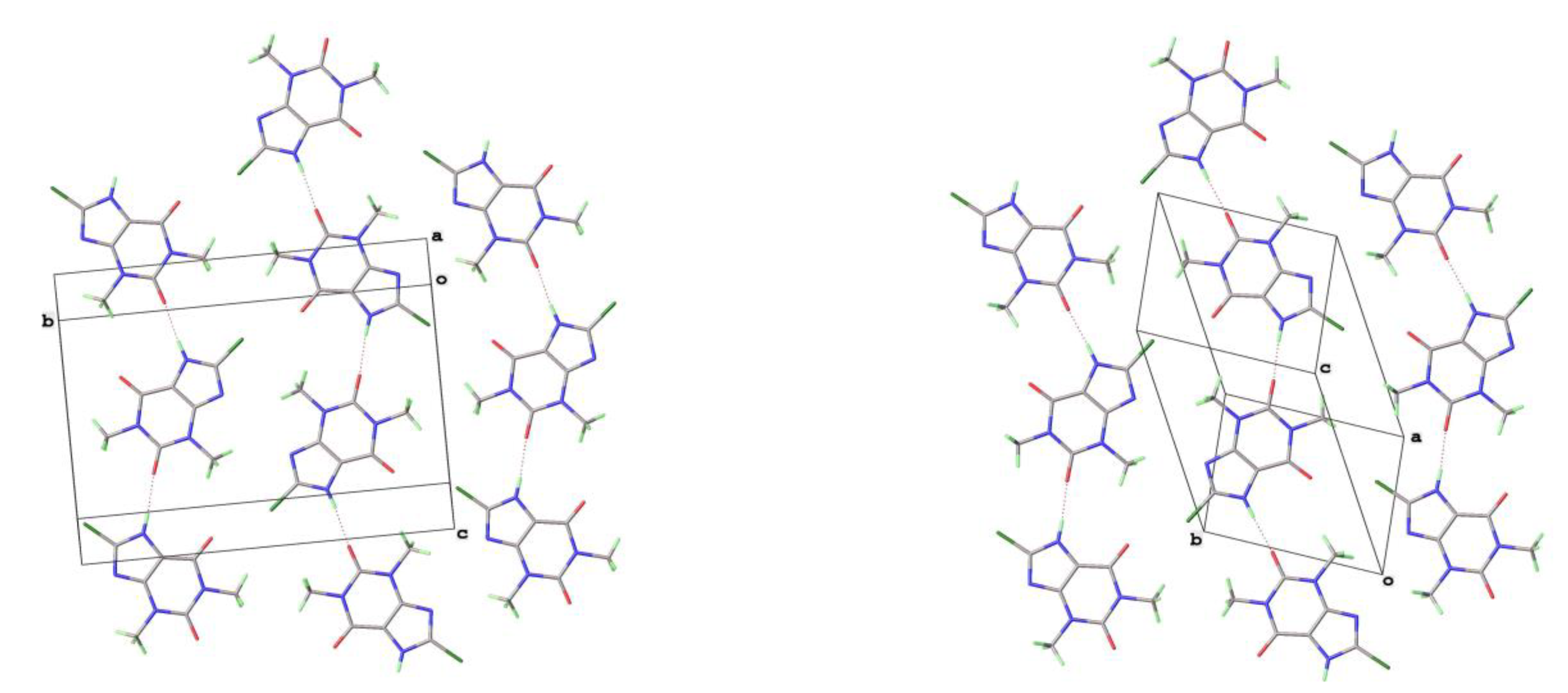

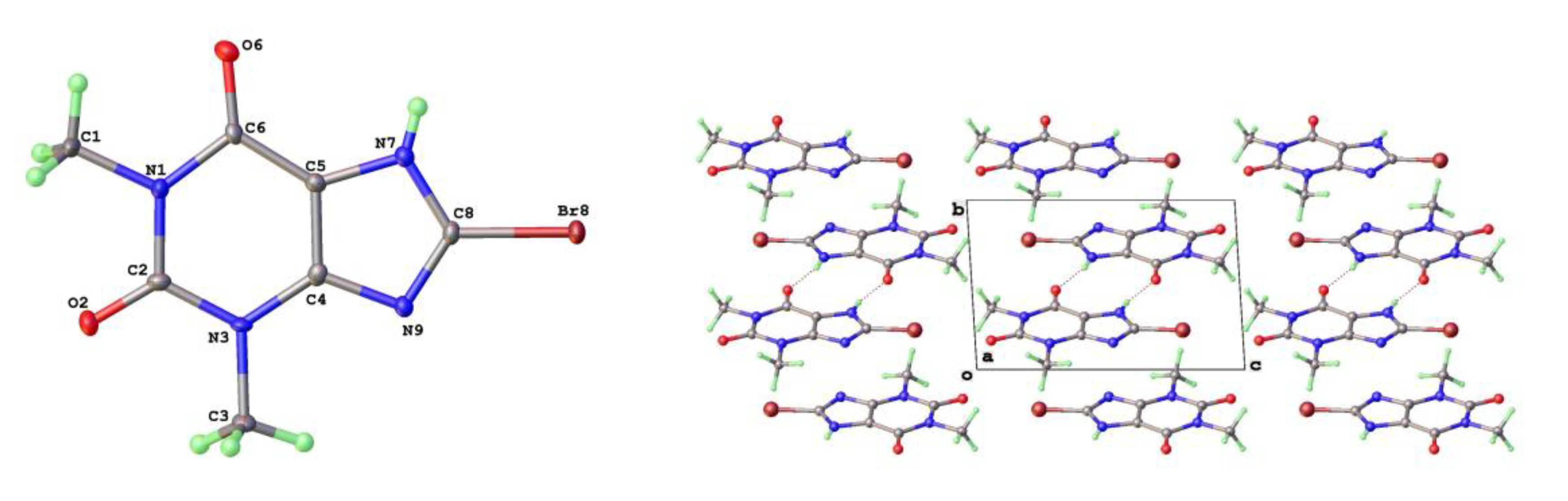

The crystal structures of 8-Cl-Tph and 8-Br-Tph show some differences, although the commonly isolated Form I (

Figure 8) is isostructural in the two cases. The Form-II for 8-Cl-Tph that can be isolated by crystallization from various aprotic solvents is a structural variant of Form I. The asymmetric unit now includes two molecules, so the two forms differ considerably in configurational entropy [

36]. Essentially isometric 2D sheets of 1D hydrogen bonded strands are found in the two cases, as shown in

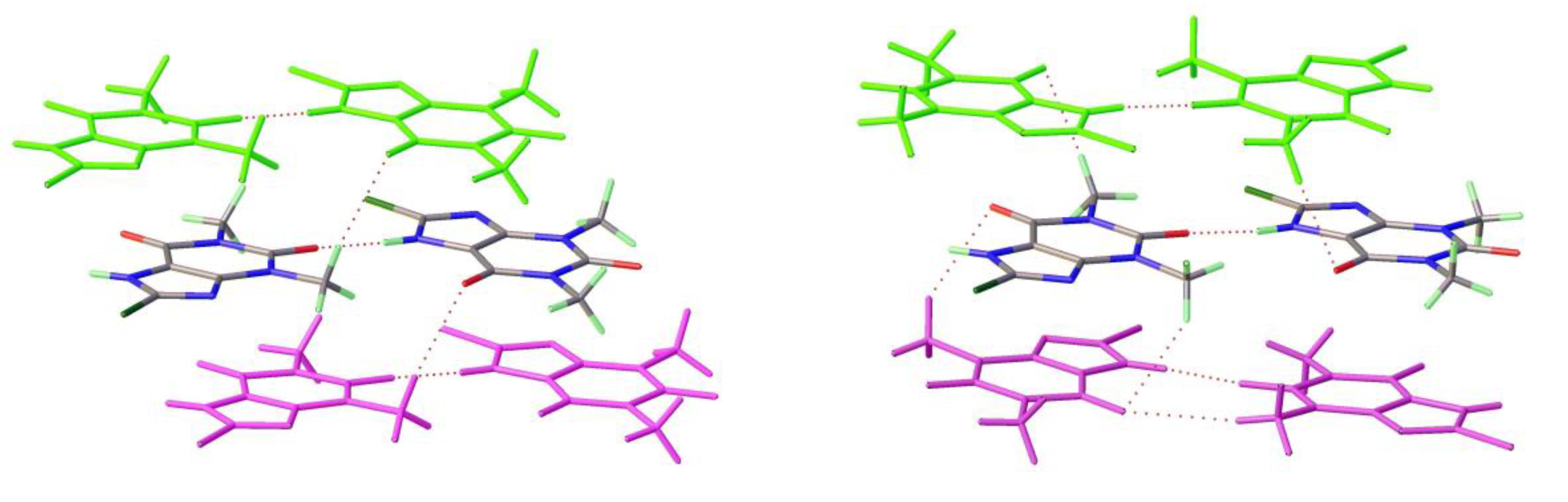

Figure 9. However, quite different stacking of these layers is found for the two forms, (

Figure 10). The strongest interactions are C-H---O nature between methyl hydrogen atoms and keto oxygens of adjacent layers, since there are two chemically distinct CH

3 and keto groups per molecule, this gives scope for different arrangements of very similar energy. DSC (

Figure 7) gives higher melting point (T

m = 306

oC versus 304

oC) and heat of fusion (H

F = 449 Jg

-1 versus 364 Jg

-1) Given the otherwise high similarity of overall packing efficiency (V

mol are essentially equal) and geometric near equivalence of NH---O hydrogen bonds (

Table 6) then these two phases may have an enantiotropic stability relationship, with Form-II more stable at lower temperature.

The related 8-Br-Tph also crystallizes with the monoclinic Form-I structure, however the second chain Form-II type has not yet been observed for 8-Br-Tph, though an extensive search for polymorphic forms of this compound has not yet been conducted, so it may well exist.

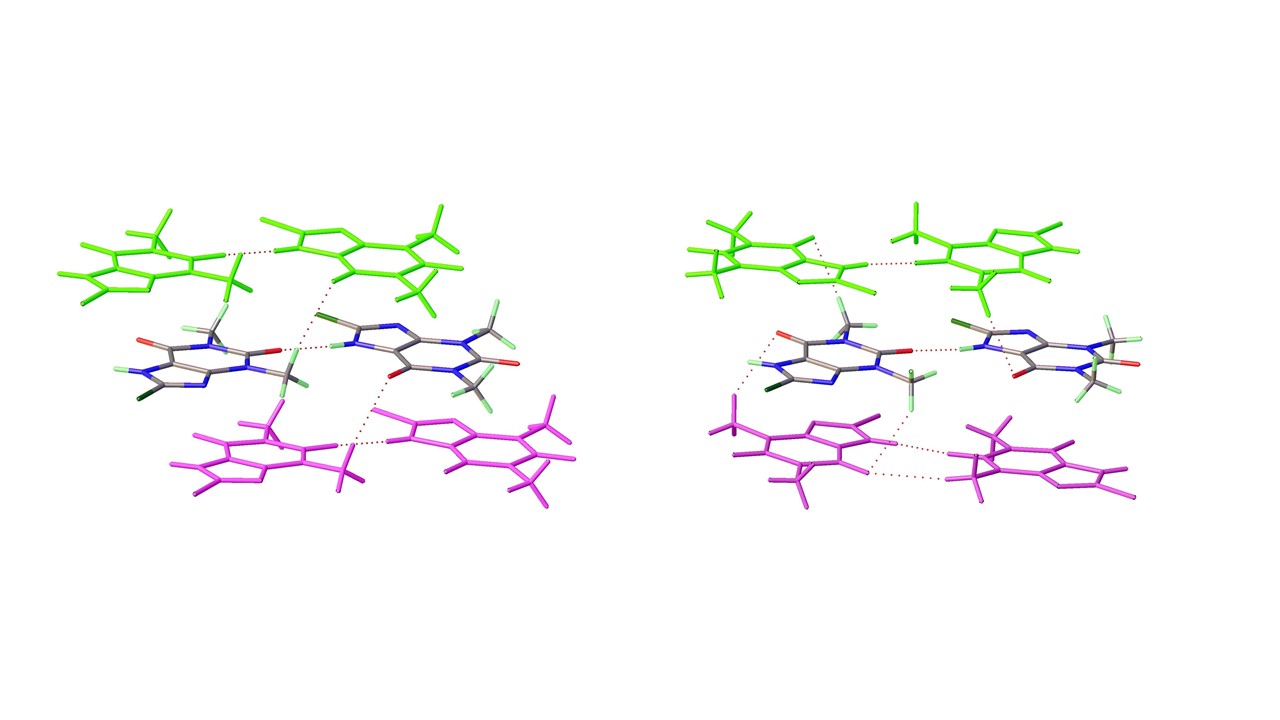

As mentioned above a third polymorph of 8-Cl-Tph, Form III was also isolated from a cocrystallization attempt. This has a dimeric structure, formed by pairing of Tph molecules via N(7)-H(7)---O(6) hydrogen bonds, forming a R

22(10) ring. Interestingly, unlike the dimer polymorph for Tph the specific volume in this 8-Cl-Tph polymorph is the smallest found. 8-Br-Tph has also been isolated in a dimer polymorph from an attempted co-crystallization with chrysin. (We will call this Form IV, since analog structures of the 8-Cl-Tph Form-II and III may yet be found). The 8-X-Tph Forms-III and IV are similar in that dimers pack in coplanar layers that are metrically similar in the two cases, see

Figure 11b and

Figure 12b. Once more however the stacking of these layers is quite different (Fig. 13) A similar dimer arrangement is also found for theophylline hydrate [

17] and the meta-stable Form III of the anhydrous Tph [

18].

4. Discussion

Some rationalization of this structural diversity has been sought and Density Functional Theory has helped to shed some light on the origin of the differences. The main point is that whilst theophylline polymorphs are dominated by N(7)-H(7)—N(9) hydrogen bonds, in the case of the 8-halo analogues N(7)-H(7)---O hydrogen bonds are exclusively found. In general these are to keto oxygen O(2) leading to chain structures that are distinct from Tph cases. The introduction of a 8-X substituent might be expected to modify the acidity/ basicity of the nearby N(7)-H(7) and N(9) functionalities respectively. In the well-known case of pyridine, compared to 2-chloro and 2-bromopyridines the pKa of the pyridinium cations (or pK

HB) are 5.17, 0.72 and 0.90 respectively [

37]. This indicates that the halogen effect would be to render adjacent NH more acidic but an adjacent N less basic. This effect would be stronger for the chloro substituent, but similar in both cases.

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations have been carried out on theophylline before [

35,

38,

39]. This has allowed identification of IR vibrational modes and also confirm the expectation that in concentrated aqueous solution the dimer form will be stable [

35]. Calculations on the 8-Cl-Tph anion in Dimenhydrinate have also been run previously to help confirm the salt rather than the neutral cocrystal formulation for this solid phase of Dramamine [

12]. We undertook DFT calculations on Tph and 8-Cl-Tph and 8-Br-Tph to confirm the assumption that the halo substituted molecule will have a substantial weakening of N(9) basicity, but less effect on keto oxygen O(2). The results in

Table 7 provide an analysis of the partial charges on substituent atoms, calculated by both the Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) [

31] and ESP [

32,

33] methods embedded in Gaussian09 software [

27].

The NBO results show relatively small differences between the three molecules, and ESP approach is better suited to understand likely electrostatic interactions between molecules. In this case charges on O(2) oxygen and N(9) nitrogen can be seen to swap over so that in Tph the N(9) is -0.616 and O(2) -0.532, helping to favour NH---N hydrogen bond formation, whereas in 8-Cl-Tph N(9) is -0.516 and O(2) -0.545, leading to favorability of NH---O polymorphic forms. 8-Br-Tph is intermediate but more similar to the chloro compound. The acidity of the NH functionality is not so clearly demonstrated in the charge on H(7) itself, or the computed bond distances, which are all 1.00Å. However the Wiberg bond order is 0.79 for Tph, greater than in the 8-X-Tph cases (0.78).

Each molecule also has an example of a dimer structure involving R

22(10) rings and N(7)-H(7)---O(6) hydrogen bonds, but none of these are isostructural with each other. In the 8-Cl-Tph and 8-Br-Tph cases the Br atoms lie above and below the alkaloid six membered ring, whereas the Cl atoms interact with methyl groups lying outside the xanthine rings. This may reflect an electronic rather than steric preference. Subtle differences in halogen environment exist in the 8-X-Tph polymorphs, and shorter Br---O contacts than Cl---O contacts are found even in isostructural Form I. We have observed that stronger halogen bond interactions in 11-azaartemisinin cocrystals with 4-halo-salicylic acids leads to switching of energy preferences for polymorphic structures [

40]. In the case of Tph the anhydrous form originates from desolvation of the hydrate, which has a different layer arrangement that is not wholly planar and that orients C(1) methyl groups in proximity to each other, [

19] which is not the case for the halo analogues.

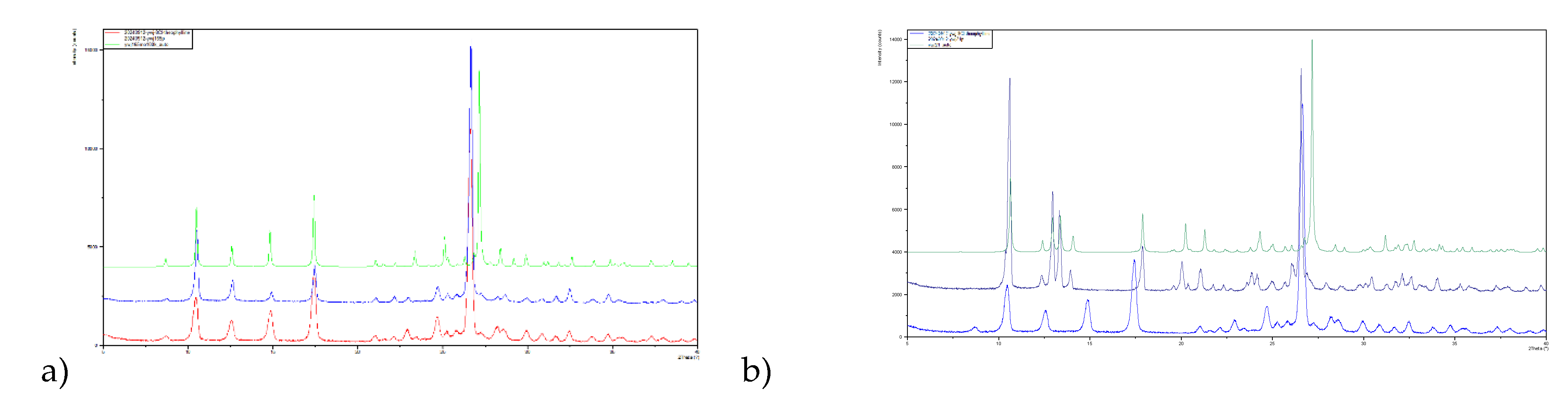

Isolation of phase pure polymorphs has not yet been achieved for all 8-X-Tph forms. In the case of 8-Cl-Tph Form-I and II can be prepared and powder XRD patterns of phases isolated from high temperature crystallization from ethanol and acetone fit to those simulated from the Form-I and Form-II crystal structures. The P-XRD of as received 8-Cl-Tph matches to Form-I. (

Figure 14)

The difference and similarity of these different packing arrangements have also lead us to study possible solid-solution formation between the molecules and the potential to template alternate polymorphic forms from analogue structures [

41,

42]. Unsurprisingly Tph and the 8-halo analogues appear mutually insoluble and LAG co-grinding [

21,

22] does not afford a solid solution. In the case of 8-Cl-Tph and 8-Br-Tph however the electronic and steric similarity lead to the stable Form I being isostructural. Unsurprisingly then, a solid solution can be formed and a single crystal from a 1:1 codissolution in hot methanol and reprecipitation upon cooling gave a crystal structure indicating disorder at the 8-substituted site. This refined to occupancies of 72% 8-Cl and 28% 8-Br-Tph. The unit cell of the Solid Solution crystal is intermediate with V = 849 Å

3 compared to 840 Å

3 and 860Å

3 for the pure 8-Cl-Tph and 8-Br-Tph structures.

Our initial purpose behind study of the theophylline and 8-halotheophyllines was to examine their involvement in formation of cocrystals with a variety of flavonoids. The measurement of their crystal structures at 100K was to provide benchmark specific molecular volumes that might be used to assist comparison of coformer versus cocrystal volumes. The switch of structure type from N(H)---N to NH--O hydrogen bonding and the DFT calculation of weaker basicity for the 8-halo theophyllines hints that weaker basicity of the alkaloid base N adversely affects the formation of cocrystals with the hydrogen bond donor flavonoids. Our initial survey supports this expectation, with initial screening affords six cocrystals for Tph yet only two each for 8-Cl-Tph and 8-Br-Tph the full results of these studies [

43] will be reported elsewhere.

5. Conclusions

The crystal structures of several new polymorphic forms of the 8-halotheophyllines 8-Cl-Tph and 8-Br-Tph have been determined. Unlike parent molecule theophylline, in which NH---N hydrogen bonds are typically favored, the structures are dominated by inter-molecular NH---O hydrogen bonding. This may be rationalized from the electronic perturbation of the halo substituent on the donor and acceptor properties of the proximal N(7)-H and N(9) groups. This renders N(7)H a slightly better donor, but crucially N(9) a weaker acceptor. DFT calculations support the idea that O(2) is more basic than N(9) leading to this switch. The most stable 8-Br-Tph polymorph appears isostructural with that of 8-Cl-Tph. In addition to chain arrangents, distinct dimer forms are found for all three molecules, so that now a total of nine packing arrangements - Tph Forms I-V and 8-X-Tph Forms I-IV, have been found for these theophylline type molecules.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.D.W.; methodology, W.Y.; I.D.W.; computation, refinement H.H-Y.S., F.K.S.; L.W-Y.W; validation, C.Z.; L.W-Y.W; formal analysis, I.D.W., F.K.S.; investigation, W.Y.; C.Z.; F.K.S.; data curation, H.H-Y.S., F.K.S; writing—original draft preparation, I.D.W.; writing—review and editing, All.; supervision, I.D.W.; project administration, I.D.W..; funding acquisition, I.D.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (grant No. 16306515) and equipment grant C6022-20E; Hong Kong Branch of the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Guangzhou) (grant No. SMSEGL-20SC01-D) and the National Engineering Research Center for Tissue Regeneration and Reconstruction (Hong Kong branch).

Data Availability Statement

Crystal structure determinations have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) and available in the Cambridge Structural Database (deposition numbers in

Table 1,

Table 4 and

Table 5).

Acknowledgments

Dr Fanny L-Y. Shek and Jane Y C. Wu are thanked for their help with the DSC measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DFT |

Density Functional Theory |

| Tph |

Theophylline |

| LAG |

Liquid Assisted Grinding |

| TGA |

Thermal Gravimetric Analysis |

References

- Carluccci, L.; Gavezzzotti, A. Molecular Recognition and Crystal Energy Landscapes: An X-ray and Computational Study of Caffeine and Other Methylxanthines. Chem. Eur. J., 2005, 11, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutor, D.J. The structures of the pyrimidines and purines. VII. The crystal structure of caffeine. Acta Crystallogr. 1958, 11, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaro, A.; Starek, G. Thermodynamic Properties of Caffeine Crystal Forms. J. Phys. Chem. 1980, 84, 1345–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trask, A.V.; Motherwell, W.D.S.; Jones, W. Physical stability enhancement of theophylline via cocrystallization. Int. J. Pharmaceutics 2006, 320, 114–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanphui, A.; Nangia, A. Salts and Co-crystals of Theobromine and their phase transformations in water. J. Chem. Sci., 2014, 126, 1249–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, G.D.; Terskikh, V.V.; Brouwer, D.H.; Ripmeester, J.A. The Structure of Two Anhydrous Polymorphs of Caffeine from Single-Crystal Diffraction and Ultrahigh-Field Solid-State 13C NMR Spectroscopy. Cryst. Growth Des., 2007, 7, 1406–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, C.W.; Stowasser, F. The crystal structure of anhydrous beta-caffeine as determined from X-ray powder-diffraction data. Chemistry, 2007, 13, 2908–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalchuk, A.A.L.; Tumanov, I.A.; Boldyreva, E. The effect of ball mass on the mechanochemical transformation of a single-component organic system: anhydrous caffeine. J. Mater. Sci., 2018, 53, 13380–13389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trask, A.V.; Motherwell, W.D.S.; Jones, W. Pharmaceutical Cocrystallization: Engineering a Remedy for Caffeine Hydration. Cryst. Growth Des., 2005, 5, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madusanka, N.; Eddleston, M.D.; Arhangelskis, M.; Jones, W. Polymorphs, hydrates and solvates of a co-crystal of caffeine with anthranilic acid. Acta Crystallogr. Sect B 2014, 70, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Wei, Y.; Chen, H.; Qian, S.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y. Competitive cocrystallization and its application in the separation of flavonoids. IUCrJ, 2021, 8, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putra, O.D.; Yoshida, T.; Umeda, D.; Higashi, K.; Uekusa, H.; Yonemochi, E. Crystal Structure Determination of Dimenhydrinate after More than 60 Years: Solving Salt–Cocrystal Ambiguity via Solid-State Characterizations and Solubility Study. Cryst. Growth Des., 2016, 16, 5223–5229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebisuzaki, Y.; Boyle, P.D.; Smith, J.A. Methylxanthines. I. Anhydrous Theophylline Acta Cryst. C, 1997, 53, 777–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Fischer, A. A monoclinic polymorph of theophylline. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E, 3357. [Google Scholar]

- Khamar, D.; Pritchard, R.G.; Bradshaw, I.J.; Hutcheon, G.; Seton, L. Polymorphs of anhydrous theophylline: stable form IV consists of dimer pairs and metastable form I consists of hydrogen-bonded chains. Acta Crystallogr., Sect.C 2011, 67, o496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fucke, K.; McIntyre, G.J.; Wilkinson, C.; Henry, M.; Howard, J.A.K.; Steed, J.W. New insights into an Old Molecule: Interaction Energies of Theophylline Crystal Forms. Cryst. Growth Des., 2012, 12, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, A.S.; Olsen, M.A.; Moustafa, H.; Larsen, F.H.; Sauer, S.P.A.; Rantanen, J.; Madsen, A.O. Determining short-lived solid forms during phase transformations using molecular dynamics. CrystEngComm, 2019, 21, 4020–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seton, L.; Khamar, D.; Bradshaw, I.J; Hutcheon, G.A. Solid State Forms of Theophylline: Presenting a New Anhydrous Polymorph. Cryst. Growth Des., 2010, 10, 3879–3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhou, D.; Grant, D.J.W; Young Jr, V.G. Theophylline Monohydrate. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E, 2002, 58, O368–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyulgerov, V.M.; Dimowa, L.T.; Kossev, K.; Nikolova, R.P.; Shivachev, B.L. Solvothermal synthesis of theophylline an N,N ′-(ethane-1,2-diyl)diformamide co-crystals from DMF decomposition and N-formylation trough catalytic effect of 3-carboxyphenylboronic acid and cadmium acetate. Bulgarian Chem. Commun., 2015, 47, 311–316. [Google Scholar]

- Trask, A. V.; Jones, W. Crystal Engineering of Organic Cocrystals by the Solid-State Grinding Approach. Top. Curr. Chem. 2005, 254, 41–70. [Google Scholar]

- Trask, A. V.; van de Streek, J.; Motherwell, W. D. S.; Jones, W. Achieving Polymorphic and Stoichiometric Diversity in Cocrystal Formation: Importance of Solid-State Grinding, Powder X-ray Structure Determination, and Seeding. Cryst. Growth Des., 2005, 5, 2233–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A, 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C, 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. Olex2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourhis, L.J.; Dolomanov, O.V.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. The anatomy of a comprehensive constrained, restrained refinement program for the modern computing environment-Olex2 dissected. Acta Cryst. A, 2015, 71, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; et al., Gaussian 09, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2009.

- Chai, J-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2008, 10, 6615–6620. [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiberg, K.B. Application of the Pople-Santry-Segal CNDO method to the cyclopropylcarbinyl and cyclobutyl cation and to bicyclobutane. Tetrahedron, 1968, 24, 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendening, E.D.; Landis, C.R.; Weinhold, F. Natural bond orbital methods. WIREs Comput Mol Sci, 2012, 2, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besler,B. H.; Merz, K.M.Jr.; Kollman, P.A. Atomic charges derived from semiempirical methods. J. Comp. Chem., 1990, 11, 431–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.C.; Kollman, P.A. An approach to computing electrostatic charges for molecules. J. Comp. Chem., 1984, 5, 129–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, M.C.; Macdonald, J.C.; Bernstein, J. Graph-set analysis of hydrogen bond patterns. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B, 1990, 46, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.B. Spectroscopic signatures and structural motifs in isolated and hydrated theophylline: a computational study. RSC Adv 2015, 5, 1143–11444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivovichev, S.V. Structural complexity and configurational entropy of crystals. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B, 2016, 72, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Jencks, W.P.; Westheimer, F.H. Compilation of pKa Acidity Constants (ACS Organic division) 2025. https://www.webqc.org/pkaconstants.php and refs therein.

- Nolasco, M.M.; Amado, A.M.; Ribeiro-Claro, P.J.A. Computationally-Assisted Approach to the Vibrational Spectra of Molecular Crystals: Study of Hydrogen-Bonding and Pseudo-Polymorphism ChemPhysChem, 2006, 7, 2150–2161.

- Hawkins, B.A.; Du, J.J.; Lai, F.; Stanton, S.A.; Williams, P.A.; Groundwater, P.W.; Platts, J.A.; Overgaard, J.; Hibbs, D.E. An experimental and theoretical charge density study of theophylline and malonic acid cocrystallisation. RSC Adv., 2022, 12, 15670–15684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Roy, M.; Nisar, M.; Wong, L.W.-Y.; Sung, H.H.-Y.; Haynes, R.K.; Williams, I.D. Control of 11-Aza:4-X-SalA Cocrystal Polymorphs Using Heteroseeds That Switch On/Off Halogen Bonding. Crystals 2022, 12, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srirambhatla, V. K. , Guo, R., Price, S. L. & Florence, A. J. Isomorphous template induced crystallisation: a robust method for the targeted crystallisation of computationally predicted metastable polymorphs. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 7384–7386. [Google Scholar]

- Case, D. H.; Srirambhatla, V. K.; Guo, R.; Watson, R. E.; Price, L. S.; Polyzois, H.; Cockcroft, J. K.; Florence, A. J.; Tocher, D. A.; Price, S. L. Successful Computationally Directed Templating of Metastable Pharmaceutical Polymorphs. Cryst. Growth Des., 2018, 18, 5322–5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W. Isolation, Purification and Structural Studies of Natural Product Crystals and Cocrystals. PhD Thesis, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Dec. 2024.

Figure 1.

Molecular scheme for Theophylline alkaloids.

Figure 1.

Molecular scheme for Theophylline alkaloids.

Figure 2.

a) Molecular structure and b) packing for Theophylline Form-II (viewed along short b-axis).

Figure 2.

a) Molecular structure and b) packing for Theophylline Form-II (viewed along short b-axis).

Figure 3.

a) Molecular structure and b) packing for Theophylline Form-V (viewed along short b-axis).

Figure 3.

a) Molecular structure and b) packing for Theophylline Form-V (viewed along short b-axis).

Figure 4.

Comparison of zig-zag and parallel hydrogen bonded strands for Form II and V theophylline.

Figure 4.

Comparison of zig-zag and parallel hydrogen bonded strands for Form II and V theophylline.

Figure 5.

a) Molecular structure and b) packing for Theophylline.H2O (viewed along short a-axis).

Figure 5.

a) Molecular structure and b) packing for Theophylline.H2O (viewed along short a-axis).

Figure 6.

Crystal habits of 8-halotheophyllines: 8-Cl-Tph Forms a) -I b) -II c) -III 8-Br-Tph Forms d) -I e) -IV.

Figure 6.

Crystal habits of 8-halotheophyllines: 8-Cl-Tph Forms a) -I b) -II c) -III 8-Br-Tph Forms d) -I e) -IV.

Figure 7.

Differential scanning calorimetry for 8-chlorotheophylline: a) Form-I b) Form-II.

Figure 7.

Differential scanning calorimetry for 8-chlorotheophylline: a) Form-I b) Form-II.

Figure 8.

a) Molecular structure and labelling scheme for 8-Chlorotheophylline Form I (left) and II (right).

Figure 8.

a) Molecular structure and labelling scheme for 8-Chlorotheophylline Form I (left) and II (right).

Figure 9.

Isostructurality of 2D layers in 8-Cl-Tph Forms I (left) and II (right) showing relationship to unit cells.

Figure 9.

Isostructurality of 2D layers in 8-Cl-Tph Forms I (left) and II (right) showing relationship to unit cells.

Figure 10.

Differentiation of 2D layer stacking in 8-Cl-Tph Forms I (left) and II (right).

Figure 10.

Differentiation of 2D layer stacking in 8-Cl-Tph Forms I (left) and II (right).

Figure 11.

a) Molecular structure and b) packing for 8-Chlorotheophylline dimer Form III (viewed along a-axis).

Figure 11.

a) Molecular structure and b) packing for 8-Chlorotheophylline dimer Form III (viewed along a-axis).

Figure 12.

a) Molecular structure and b) packing for 8-Bromotheophylline dimer Form IV (viewed along a-axis).

Figure 12.

a) Molecular structure and b) packing for 8-Bromotheophylline dimer Form IV (viewed along a-axis).

Figure 13.

Differential layer overlap for 8-Cl-Tph (Form III) and 8-Br-Tph (Form IV) dimer structures.

Figure 13.

Differential layer overlap for 8-Cl-Tph (Form III) and 8-Br-Tph (Form IV) dimer structures.

Figure 14.

Powder X-ray diffractograms for 8-Cl-Tph a) Form I and b) Form-II.

Figure 14.

Powder X-ray diffractograms for 8-Cl-Tph a) Form I and b) Form-II.

Table 1.

Summary of Crystal Data of the Theophylline Polymorphs.

Table 1.

Summary of Crystal Data of the Theophylline Polymorphs.

| Form |

T(K) |

Sp Gp |

a (Å) |

b (Å) |

c (Å) |

β (o) |

V (Å3) |

Vmol (Å3) |

CSD Coden |

Ref |

Comment |

| RT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| II |

297 |

Pna21

|

24.612 |

3.83 |

8.501 |

90 |

801.38 |

200.3 |

BAPLOT01 |

14 |

Better RT |

| III |

298 |

P21/c |

4.531 |

11.578 |

15.719 |

93.69 |

822.92 |

205.7 |

BAPLOT08 |

18 |

Metastable |

| IV |

299 |

P21/c |

7.894 |

12.909 |

15.905 |

104.21 |

1571.1 |

196.4 |

BAPLOT02 |

15 |

|

| V |

290 |

Pn |

3.874 |

12.89 |

8.117 |

98.97 |

400.4 |

200.2 |

BAPLOT09 |

20 |

Solvothermal |

| LT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

120 |

Pna21

|

13.087 |

15.579 |

3.8629 |

90 |

787.6 |

196.9 |

BAPLOT05 |

17 |

|

| I |

100 |

Pna21

|

13.158 |

15.630 |

3.854 |

90 |

792.6 |

198.2 |

BAPLOT04 |

16 |

Stable HT |

| II |

120 |

Pna21

|

24.330 |

3.7707 |

8.4850 |

90 |

778.43 |

194.6 |

BAPLOT06 |

17 |

|

| II |

100 |

Pna21

|

24.3948 |

3.7816 |

8.4779 |

90 |

782.1 |

195.5 |

Ywj32 |

This work |

Hot cooled |

| IV |

100 |

P21/c |

7.705 |

13.001 |

15.7794 |

103.22 |

1538.85 |

192.4 |

BAPLOT03 |

16 |

Stable RT |

| V |

100 |

Pn |

3.8121 |

12.8944 |

8.0643 |

99.56 |

390.9 |

195.5 |

Ywj48 |

This work |

|

| H2O |

173 |

P21/n |

4.468 |

15.355 |

13.121 |

97.79 |

891.9 |

223.0 |

THEOPH01 |

19 |

|

| H2O |

120 |

P21/n |

4.4605 |

15.3207 |

13.0529 |

97.51 |

884.36 |

221.1 |

THEOPH02 |

17 |

neutron |

| H2O |

100 |

P21/n |

4.453 |

15.3127 |

13.0396 |

97.42 |

881.7 |

220.4 |

Ywj138 |

This work |

RT growth |

Table 2.

Hydrogen Bonds in Theophylline Forms II, V and its Hydrate.

Table 2.

Hydrogen Bonds in Theophylline Forms II, V and its Hydrate.

| D |

H |

A |

d(D-H)/Å |

d(H-A)/Å |

d(D-A)/Å |

D-H-A/° |

| Form II |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| N7 |

H7 |

N91

|

0.90(5) |

1.88(5) |

2.782(3) |

177(4) |

| Form V |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| N7 |

H7 |

N91

|

0.97(5) |

1.86(5) |

2.820(3) |

174(5) |

| Hydrate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| N7 |

H7 |

O61

|

0.89(2) |

1.88(2) |

2.754(2) |

166(2) |

| O1W |

H1W |

N9 |

0.87(3) |

2.02(3) |

2.888(2) |

175(3) |

| O1W |

H1W |

O1W2

|

0.91(4) |

1.83(4) |

2.725(4) |

169(5) |

| O1W |

H1W |

O1W3

|

0.81(6) |

1.94(6) |

2.734(3) |

168(7) |

Table 3.

Summary of Crystal Data of the 8-Halotheophylline Polymorphs at 100K.

Table 3.

Summary of Crystal Data of the 8-Halotheophylline Polymorphs at 100K.

| Form |

Sp Gp |

a (Å) |

b (Å) |

c (Å) |

α (o) |

β (o) |

γ (o) |

V (Å3) |

Vmol (Å3) |

Code |

R1 |

| 8-Cl |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

P21/c |

3.90604(9) |

16.8562(3) |

12.7664(3) |

90 |

92.031(2) |

90 |

840.02(3) |

210.0 |

Ywj165 |

3.33 |

| II |

P-1 |

8.9581(4) |

8.9956(3) |

11.3519(5) |

80.95(1) |

84.40(1) |

68.80(1) |

841.42(6) |

210.4 |

Ywj21 |

3.14 |

| III |

P-1 |

4.4920(6) |

10.0818(10) |

10.1846(14) |

110.30(1) |

96.88(1) |

99.93(1) |

418.0(1) |

209.0 |

Ywj115 |

3.32 |

| 8-Br |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

P21/c |

3.9463(1) |

17.0024(3) |

12.8384(2) |

90 |

91.933(2) |

90 |

860.92(3) |

215.2 |

Ywj30 |

2.23 |

| IV |

P-1 |

6.5878(6) |

6.8562(4) |

10.3366(10) |

92.754(6) |

90.961(7) |

108.06(1) |

443.11(6) |

221.6 |

Ywj126b |

3.42 |

| 8-Cl/Br |

72:28* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| I |

P21/c |

3.9204(2) |

16.9274(10) |

12.8080(7) |

90 |

91.97(1) |

90 |

849.46(8) |

212.4* |

Louis4Ga |

2.16 |

Table 4.

Structure determination summaries for three polymorphic forms of 8-Cl-Tph.

Table 4.

Structure determination summaries for three polymorphic forms of 8-Cl-Tph.

| 8-Cl-Tph |

Form-I |

Form-II |

Form-III |

| |

|

|

|

| CCDC /(Our code) |

Ywj165 |

Ywj21 |

Ywj115 |

| Empirical formula |

C7H7ClN4O2

|

C7H7ClN4O2

|

C7H7ClN4O2

|

| Formula weight |

214.62 |

214.62 |

214.62 |

| Temperature/K |

99.99(10) |

100.15 |

100.01(10) |

| a/Å |

3.90604(9) |

8.9581(4) |

4.4920(6) |

| b/Å |

16.8562(3) |

8.9956(3) |

10.0818(10) |

| c/Å |

12.7664(3) |

11.3519(5) |

10.1846(14) |

| α/° |

90 |

80.95(1) |

110.304(10) |

| β/° |

92.031(2) |

84.40(1) |

96.877(11) |

| γ/° |

90 |

68.80(1) |

99.931(10) |

| Volume/Å3

|

840.02(3) |

841.42(6) |

417.97(10) |

| Z, Z’ |

4, 1 |

4, 2 |

2, 1 |

| ρcalcg/cm3 μ/mm-1

|

1.697, 3.892 |

1.694, 3.886 |

1.705, 3.911 |

| F(000) |

440.0 |

440.0 |

220.0 |

| Crystal size/mm3

|

0.15 x 0.10 x 0.08 |

0.15 × 0.08 × 0.08 |

0.06 x 0.04 x 0.04 |

| Radiation |

CuKα (λ = 1.54184) |

CuKα (λ = 1.54184) |

CuKα (λ = 1.54184) |

| 2Θ range /° |

8.7 to 154.0 |

8.0 to 149.0 |

9.4 to 149.5 |

| Index ranges |

-3 ≤ h ≤ 4, -21 ≤ k ≤ 20, ж -11 ≤ l ≤ 16 |

-10 ≤ h ≤ 11, -11 ≤ k ≤ 11 ж -14 ≤ l ≤ 14 |

-5 ≤ h ≤ 5, -6 ≤ k ≤ 12 ж -12 ≤ l ≤ 9 |

| Reflections collected |

5186 |

12856 |

2307 |

| Independent reflections ж Rint, Rsigma |

1732 ж 0.0247, 0.0247 |

3347 ж 0.0351, 0.0270 |

1615 ж 0.0187, 0.0273 |

| Data/restraints/parameters |

1732/ 0/ 133 |

3347/ 0/ 265 |

1615/ 0/ 134 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2

|

1.036 |

1.041 |

1.040 |

| Final R1, wR2 [I>=2σ (I)] |

0.0333, 0.0838 |

0.0314, 0.0801 |

0.0329, 0.0881 |

| Final R indexes [all data] |

0.0395, 0.0882 |

0.0367, 0.0840 |

0.0347, 0.0904 |

| Res. peak/hole / e Å-3

|

0.33/ -0.27 |

0.31/ -0.33 |

0.43/ -0.56 |

Table 5.

Structure determination summaries for two polymorphic forms of 8-Br-Tph & 8-Cl/Br-Tph (SS).

Table 5.

Structure determination summaries for two polymorphic forms of 8-Br-Tph & 8-Cl/Br-Tph (SS).

| 8-Br-Tph |

Form-I |

Form-IV |

Form-I 8-Cl/8-Br (SS) |

| |

|

|

|

| CCDC /(Our code) |

Ywj30 |

Ywj126b |

Louis4Ga |

| Empirical formula |

C7H7BrN4O2

|

C7H7BrN4O2

|

C7H7Br0.28Cl0.72N4O2

|

| Formula weight |

259.08 |

259.08 |

227.06 |

| Temperature/K |

100.01(10) |

99.96(12) |

100.01(10) |

| a/Å |

3.94630(10) |

6.5461(3) |

3.9204(2) |

| b/Å |

17.0024(3) |

6.8780(5) |

16.9274(10) |

| c/Å |

12.8384(2) |

10.3419(5) |

12.8080(7) |

| α/° |

90 |

93.114(5) |

90 |

| β/° |

91.933(2) |

90.726(4) |

91.972(2) |

| γ/° |

90 |

107.664(5) |

90 |

| Volume/Å3

|

860.92(3) |

442.82(5) |

849.46(8) |

| Z, Z’ |

4, 1 |

2, 1 |

2, 1 |

| ρcalcg/cm3 μ/mm-1

|

1.999, 6.381 |

1.943, 4.62 |

1.775, 3.024 |

| F(000) |

512.0 |

256.0 |

460.0 |

| Crystal size/mm3

|

0.10 x 0.10 x 0.10 |

0.12 × 0.10 × 0.10 |

0.11 × 0.07 × 0.06 |

| Radiation |

CuKα (λ = 1.54184) |

MoKα (λ = 0.71073) |

GaKα (λ = 1.34139) |

| 2Θ range /° |

8.6 to 148.9 |

4.0 to 57.5 |

7.5 to 115.0 |

| Index ranges |

-4 ≤ h ≤ 4, -20 ≤ k ≤ 19, ж -15 ≤ l ≤ 11 |

-6 ≤ h ≤ 8, -9 ≤ k ≤ 5, ж -13 ≤ l ≤ 12 |

-4 ≤ h ≤ 4, -21 ≤ k ≤ 21, ж -15 ≤ l ≤ 16 |

| Reflections collected |

4627 |

2629 |

9048 |

| Independent reflections ж Rint, Rsigma |

1699 ж 0.0311, 0.0673 |

1947 ж 0.0180, 0.0513 |

1675 ж 0.0272, 0.0232 |

| Data/restraints/parameters |

1593/ 0/ 133 |

1947/ 0/ 133 |

1675/ 0/ 144 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2

|

1.003 |

1.094 |

1.049 |

| Final R1, wR2 [I>=2σ (I)] |

0.0223, 0.0556 |

0.0342 0.0763 |

0.0216, 0.0577 |

| Final R indexes [all data] |

0.0230, 0.0560 |

0.0397, 0.0796 |

0.0221, 0.0580 |

| Res. peak/hole / e Å-3

|

0.52/ -0.47 |

0.95/ -0.65 |

0.26/ -0.23 |

Table 6.

Hydrogen Bonds in 8-Halotheophyllines.

Table 6.

Hydrogen Bonds in 8-Halotheophyllines.

| |

D |

H |

A |

d(D-H)/Å |

d(H-A)/Å |

d(D-A)/Å |

D-H-A/° |

| 8-Cl Form I |

N7 |

H7 |

O21

|

0.87(3) |

1.86(3) |

2.7346(19) |

178(3) |

| 8-Cl Form II |

N7 |

H7 |

O2A |

0.92(2) |

1.81(2) |

2.7185(18) |

174(2) |

| |

N7A |

H7A |

O21

|

0.91(3) |

1.81(3) |

2.7203(18) |

177(2) |

| 8-Cl Form III |

N7 |

H7 |

O61

|

0.84(2) |

1.89(2) |

2.7297(18) |

177(2) |

| 8-Br Form I |

N7 |

H7 |

O21

|

0.84(3) |

1.93(3) |

2.760(2) |

174(3) |

| 8-Br Form IV |

N7 |

H7 |

O21

|

0.77(5) |

1.97(5) |

2.723(4) |

166(5) |

Table 7.

Atomic charges in Theophylline Molecules from DFT.

Table 7.

Atomic charges in Theophylline Molecules from DFT.

| Atom |

Tph |

8-Cl-Tph |

8-Br-Tph |

| N(1) |

-0.436 |

-0.434 |

-0.434 |

| O(2) |

-0.622 |

-0.615 |

-0.614 |

| N(3) |

-0.394 |

-0.391 |

-0.391 |

| O(6) |

-0.603 |

-0.600 |

-0.600 |

| N(7) |

-0.472 |

-0.483 |

-0.488 |

| H(7) |

0.434 |

0.443 |

0.444 |

| X(8) |

H: 0.206 |

Cl: 0.068 |

Br: 0.121 |

| N(9) |

-0.482 |

-0.488 |

-0.494 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).