Submitted:

02 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

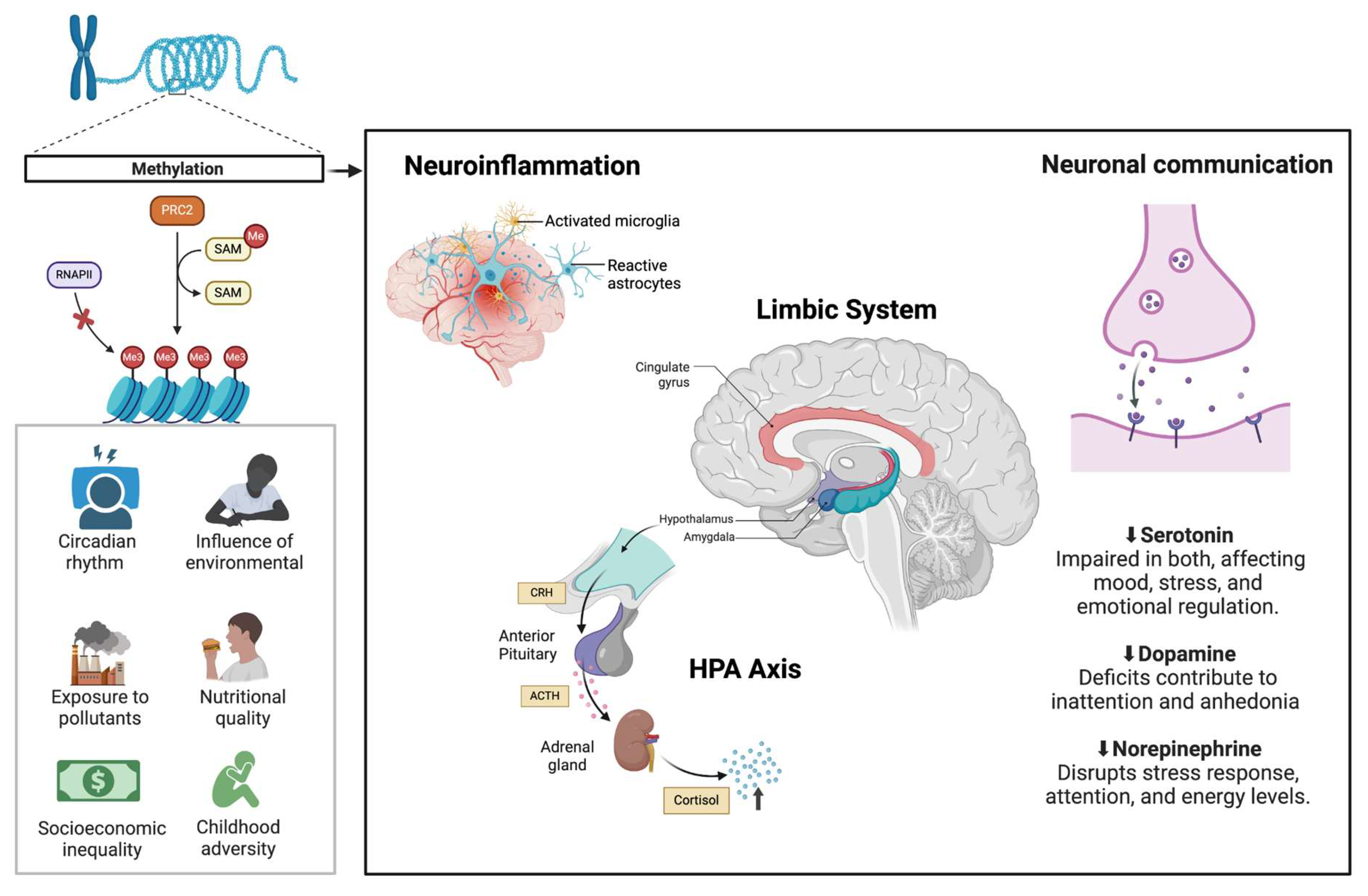

Common neurobiological mechanisms between neurodevelopmental disorders and mood disorders

Autism spectrum disorder

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Intellectual disability

Learning disorders

Communication disorders

Diagnostic and therapeutic implications

Final considerations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steel, Z.; Marnane, C.; Iranpour, C.; Chey, T.; Jackson, J.W.; Patel, V.; Silove, D. The Global Prevalence of Common Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis 1980–2013. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 476–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, M.; Xiang, M.; Zhao, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Han, L.; Ran, J. Prevalence of Neurodevelopmental Disorders among US Children and Adolescents in 2019 and 2020. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 997648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bădescu, G.M.; Fîlfan, M.; Sandu, R.E.; Surugiu, R.; Ciobanu, O.; Popa-Wagner, A. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Neurodevelopmental Disorders, ADHD and Autism. Romanian J. Morphol. Embryol. Rev. Roum. Morphol. Embryol. 2016, 57, 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Gillentine, M.A.; Wang, T.; Eichler, E.E. Estimating the Prevalence of De Novo Monogenic Neurodevelopmental Disorders from Large Cohort Studies. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halvorsen, M.; Mathiassen, B.; Myrbakk, E.; Brøndbo, P.H.; Sætrum, A.; Steinsvik, O.O.; Martinussen, M. Neurodevelopmental Correlates of Behavioural and Emotional Problems in a Neuropaediatric Sample. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 85, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesso, G.; Cristofani, C.; Berloffa, S.; Cristofani, P.; Fantozzi, P.; Inguaggiato, E.; Narzisi, A.; Pfanner, C.; Ricci, F.; Tacchi, A.; et al. Autism Spectrum Disorder and Disruptive Behavior Disorders Comorbidities Delineate Clinical Phenotypes in Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Novel Insights from the Assessment of Psychopathological and Neuropsychological Profiles. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safar, K.; Vandewouw, M.M.; Pang, E.W.; De Villa, K.; Crosbie, J.; Schachar, R.; Iaboni, A.; Georgiades, S.; Nicolson, R.; Kelley, E.; et al. Shared and Distinct Patterns of Functional Connectivity to Emotional Faces in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Children. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 826527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Nowrangi, D.; Yu, L.; Lu, T.; Tang, J.; Han, B.; Ding, Y.; Fu, F.; Zhang, J.H. Activation of Dopamine D1 Receptor Decreased NLRP3-Mediated Inflammation in Intracerebral Hemorrhage Mice. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redenšek, S.; Blagus, T.; Trošt, M.; Dolžan, V. Serotonin-Related Functional Genetic Variants Affect the Occurrence of Psychiatric and Motor Adverse Events of Dopaminergic Treatment in Parkinson’s Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzagalli, D.A.; Berretta, S.; Wooten, D.; Goer, F.; Pilobello, K.T.; Kumar, P.; Murray, L.; Beltzer, M.; Boyer-Boiteau, A.; Alpert, N.; et al. Assessment of Striatal Dopamine Transporter Binding in Individuals With Major Depressive Disorder: In Vivo Positron Emission Tomography and Postmortem Evidence. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenders, M.A.; Mesman, E.; Giltay, E.J.; Elzinga, B.M.; Hillegers, M.H.J. Traumatic Experiences, Family Functioning, and Mood Disorder Development in Bipolar Offspring. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 59, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanabrais-Jiménez, M.A.; Sotelo-Ramirez, C.E.; Ordoñez-Martinez, B.; Jiménez-Pavón, J.; Ahumada-Curiel, G.; Piana-Diaz, S.; Flores-Flores, G.; Flores-Ramos, M.; Jiménez-Anguiano, A.; Camarena, B. Effect of CRHR1 and CRHR2 Gene Polymorphisms and Childhood Trauma in Suicide Attempt. J. Neural Transm. 2019, 126, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vester, A.I.; Hermetz, K.; Burt, A.; Everson, T.; Marsit, C.J.; Caudle, W.M. Combined Neurodevelopmental Exposure to Deltamethrin and Corticosterone Is Associated with Nr3c1 Hypermethylation in the Midbrain of Male Mice. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2020, 80, 106887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straub, L.; Bateman, B.T.; Hernandez-Diaz, S.; York, C.; Lester, B.; Wisner, K.L.; McDougle, C.J.; Pennell, P.B.; Gray, K.J.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Neurodevelopmental Disorders Among Publicly or Privately Insured Children in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 79, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besterman, A.D.; Adams, D.J.; Wong, N.R.; Schneider, B.N.; Mehta, S.; DiStefano, C.; Wilson, R.B.; Martinez-Agosto, J.A.; Jeste, S.S. Genomics-Informed Neuropsychiatric Care for Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Results from A Multidisciplinary Clinic 2024.

- Rai, S.; Griffiths, K.R.; Breukelaar, I.A.; Barreiros, A.R.; Boyce, P.; Hazell, P.; Foster, S.L.; Malhi, G.S.; Harris, A.W.F.; Korgaonkar, M.S. Common and Differential Neural Mechanisms Underlying Mood Disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2022, 24, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Q.; Hu, L.; Ding, Y.-Q.; Lang, B. Editorial: The Commonality in Converged Pathways and Mechanisms Underpinning Neurodevelopmental and Psychiatric Disorders. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1349631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcolongo-Pereira, C.; Castro, F.C.D.A.Q.; Barcelos, R.M.; Chiepe, K.C.M.B.; Rossoni Junior, J.V.; Ambrosio, R.P.; Chiarelli-Neto, O.; Pesarico, A.P. Neurobiological Mechanisms of Mood Disorders: Stress Vulnerability and Resilience. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1006836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Marco, R.L.; Daniel, M.B.N.; Calvo, E.N.; Araldi, B.L. Tea e Neuroplasticidade: Identificação e Intervenção Precoce / Asd and Neuroplasticity: Identification and Early Intervention. Braz. J. Dev. 2021, 7, 104534–104552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittkopf, S.; Stroth, S.; Langmann, A.; Wolff, N.; Roessner, V.; Roepke, S.; Poustka, L.; Kamp-Becker, I. Differentiation of Autism Spectrum Disorder and Mood or Anxiety Disorder. Autism 2022, 26, 1056–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C.; Brugha, T.S.; Charman, T.; Cusack, J.; Dumas, G.; Frazier, T.; Jones, E.J.H.; Jones, R.M.; Pickles, A.; State, M.W.; et al. Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2020, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portolese, J.; Gomes, C.S.; Daguano Gastaldi, V.; Paula, C.S.; Caetano, S.C.; Bordini, D.; Brunoni, D.; Mari, J.D.J.; Vêncio, R.Z.N.; Brentani, H. A Normative Model Representing Autistic Individuals Amidst Autism Spectrum Phenotypic Heterogeneity. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morie, K.P.; Jackson, S.; Zhai, Z.W.; Potenza, M.N.; Dritschel, B. Mood Disorders in High-Functioning Autism: The Importance of Alexithymia and Emotional Regulation. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 2935–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, S.J.; He, X.; Willsey, A.J.; Ercan-Sencicek, A.G.; Samocha, K.E.; Cicek, A.E.; Murtha, M.T.; Bal, V.H.; Bishop, S.L.; Dong, S.; et al. Insights into Autism Spectrum Disorder Genomic Architecture and Biology from 71 Risk Loci. Neuron 2015, 87, 1215–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahamy, A.; Behrmann, M.; Malach, R. The Idiosyncratic Brain: Distortion of Spontaneous Connectivity Patterns in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association Publishing. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5.; Fifth edition. Special edition, 2017.; CBS Publishers & Distributors: New Delhi, 2017; ISBN 978-93-86217-96-7.

- Oakley, B.; Loth, E.; Murphy, D.G. Autism and Mood Disorders. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2021, 33, 280–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, V. [Autism, depression and risk of suicide]. Medicina (Mex.) 2020, 80 Suppl 2, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Olusanya, B.O.; Smythe, T.; Ogbo, F.A.; Nair, M.K.C.; Scher, M.; Davis, A.C. Global Prevalence of Developmental Disabilities in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Umbrella Review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1122009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sappok, T.; Hassiotis, A.; Bertelli, M.; Dziobek, I.; Sterkenburg, P. Developmental Delays in Socio-Emotional Brain Functions in Persons with an Intellectual Disability: Impact on Treatment and Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 13109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyas, M.; Mir, A.; Efthymiou, S.; Houlden, H. The Genetics of Intellectual Disability: Advancing Technology and Gene Editing. F1000Research 2020, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindstrand, A.; Eisfeldt, J.; Pettersson, M.; Carvalho, C.M.B.; Kvarnung, M.; Grigelioniene, G.; Anderlid, B.-M.; Bjerin, O.; Gustavsson, P.; Hammarsjö, A.; et al. From Cytogenetics to Cytogenomics: Whole-Genome Sequencing as a First-Line Test Comprehensively Captures the Diverse Spectrum of Disease-Causing Genetic Variation Underlying Intellectual Disability. Genome Med. 2019, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, H.; Montgomery, A.; Wolff, B.; Strumpher, E.; Masi, A.; Woolfenden, S.; Williams, K.; Eapen, V.; Finlay-Jones, A.; Whitehouse, A.; et al. A Systematic Review of the Biological, Social, and Environmental Determinants of Intellectual Disability in Children and Adolescents. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 926681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tchoua, P.P.; Clarke, E.; Wasser, H.; Agrawal, S.; Scothorn, R.; Thompson, K.; Schenkelberg, M.; Willis, E.A. The Interaction between Social Determinants of Health, Health Behaviors, and Child’s Intellectual Developmental Diagnosis 2024.

- Eaton, C.; Tarver, J.; Shirazi, A.; Pearson, E.; Walker, L.; Bird, M.; Oliver, C.; Waite, J. A Systematic Review of the Behaviours Associated with Depression in People with Severe–Profound Intellectual Disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2021, 65, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, J.P. Diagnostic Issues in Other Mental Disorders Co-Morbid With Intellectual Disability. Eur. Psychiatry 2023, 66, S22–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.L.; Baird, A.; Smith, J.; Williams, N.; Van Den Bree, M.B.M.; Linden, D.E.J.; Owen, M.J.; Hall, J.; Linden, S.C. Psychopathology in Adults with Copy Number Variants. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 3142–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightbody, A.A.; Bartholomay, K.L.; Jordan, T.L.; Lee, C.H.; Miller, J.G.; Reiss, A.L. Anxiety, Depression, and Social Skills in Girls with Fragile X Syndrome: Understanding the Cycle to Improve Outcomes. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2022, 43, e565–e572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivelli, A.; Fitzpatrick, V.; Chaudhari, S.; Chicoine, L.; Jia, G.; Rzhetsky, A.; Chicoine, B. Prevalence of Mental Health Conditions Among 6078 Individuals With Down Syndrome in the United States. J. Patient-Centered Res. Rev. 2022, 9, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barua, P.D.; Vicnesh, J.; Gururajan, R.; Oh, S.L.; Palmer, E.; Azizan, M.M.; Kadri, N.A.; Acharya, U.R. Artificial Intelligence Enabled Personalised Assistive Tools to Enhance Education of Children with Neurodevelopmental Disorders—A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, L.M.; Kelley, M.L. Risk Factors for Dual Disorders in Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities. In Handbook of Dual Diagnosis; Matson, J.L., Ed.; Autism and Child Psychopathology Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 119–139 ISBN 978-3-030-46834-7.

- Dow, M.; Long, B.; Lund, B. Reference and Instructional Services to Postsecondary Education Students with Intellectual Disabilities. Coll. Res. Libr. 2021, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, O.J.; Nair, H.P.; Ahern, T.H.; Neumann, I.D.; Young, L.J. The CRF System Mediates Increased Passive Stress-Coping Behavior Following the Loss of a Bonded Partner in a Monogamous Rodent. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Goyal, N.; Sharma, E. Learning Disability Certification in India: Quo Vadis. J. Indian Assoc. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 18, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Resa, P.; Moraleda-Sepúlveda, E. Working Memory Capacity and Text Comprehension Performance in Children with Dyslexia and Dyscalculia: A Pilot Study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1191304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Español-Martín, G.; Pagerols, M.; Prat, R.; Rivas, C.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A.; Casas, M.; Bosch, R. The Impact of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Specific Learning Disorders on Academic Performance in Spanish Children from a Low-Middle- and a High-Income Population. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1136994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higazi, A.M.; Kamel, H.M.; Abdel-Naeem, E.A.; Abdullah, N.M.; Mahrous, D.M.; Osman, A.M. Expression Analysis of Selected Genes Involved in Tryptophan Metabolic Pathways in Egyptian Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Learning Disabilities. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, T. Biological Understanding of Neurodevelopmental Disorders Based on Epigenetics, a New Genetic Concept in Education. In Learning Disabilities - Neurobiology, Assessment, Clinical Features and Treatments; Misciagna, S., Ed.; IntechOpen, 2022 ISBN 978-1-83968-587-3.

- Avigan, P.D.; Cammack, K.; Shapiro, M.L. Flexible Spatial Learning Requires Both the Dorsal and Ventral Hippocampus and Their Functional Interactions with the Prefrontal Cortex. Hippocampus 2020, 30, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Hu, L.; Liu, X.; Dong, J.; Yang, R.; Mei, L. The Contributions of the Left Hippocampus and Bilateral Inferior Parietal Lobule to Form-meaning Associative Learning. Psychophysiology 2021, 58, e13834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundakovic, M.; Jaric, I. The Epigenetic Link between Prenatal Adverse Environments and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Genes 2017, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugalde, L.; Santiago-Garabieta, M.; Villarejo-Carballido, B.; Puigvert, L. Impact of Interactive Learning Environments on Learning and Cognitive Development of Children With Special Educational Needs: A Literature Review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 674033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokot, S.J. A Neurodevelopmental Approach for Helping Gifted Learners with Diagnosed Dyslexia and Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (AD/HD). Afr. Educ. Rev. 2005, 2, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomer, C.; Berenguer, C.; Roselló, B.; Baixauli, I.; Miranda, A. The Impact of Inattention, Hyperactivity/Impulsivity Symptoms, and Executive Functions on Learning Behaviors of Children with ADHD. Front. Psychol. 2017, 08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, D.; Waldie, K.E. Developmental Learning Disorders: From Generic Interventions to Individualized Remediation. Front. Psychol. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.M.; Bahar, H.F. ; Karbala Governorate Education Directorate Ministry Of Education, Iraq MOOD DISORDER IN STUDENTS WITH LEARNING DISABILITIES. Am. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Innov. 2024, 6, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S.; Gianaros, P.J. Stress- and Allostasis-Induced Brain Plasticity. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011, 62, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupien, S.J.; McEwen, B.S.; Gunnar, M.R.; Heim, C. Effects of Stress throughout the Lifespan on the Brain, Behaviour and Cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maksyutynska, K.; Stogios, N.; Prasad, F.; Gill, J.; Hamza, Z.; De, R.; Smith, E.; Horta, A.; Goldstein, B.I.; Korczak, D.; et al. Neurocognitive Correlates of Metabolic Dysregulation in Individuals with Mood Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Med. 2024, 54, 1245–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Dong, J.; Mei, L.; Feng, G.; Li, L.; Wang, G.; Yan, H. Functional and Structural Abnormalities of the Speech Disorders: A Multimodal Activation Likelihood Estimation Meta-Analysis. Cereb. Cortex 2024, 34, bhae075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoe, M.I.; Forbes, K.; De La Roche, L.; Derby, B.; Psaradellis, E.; Anagnostou, E.; Nicolson, R.; Georgiades, S.; Kelley, E. Exploring the Association between Social Skills Struggles and Social Communication Difficulties and Depression in Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Autism Res. 2023, 16, 2160–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.J.; Currier, D.; Quiroz, J.A.; Manji, H.K. Neurobiology of Severe Mood and Anxiety Disorders. In Basic Neurochemistry; Elsevier, 2012; pp. 1021–1036 ISBN 978-0-12-374947-5.

- Kao, S.-K.; Chan, C.-T. Increased Risk of Depression and Associated Symptoms in Poststroke Aphasia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wren, Y.; Pagnamenta, E.; Orchard, F.; Peters, T.J.; Emond, A.; Northstone, K.; Miller, L.L.; Roulstone, S. Social, Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties Associated with Persistent Speech Disorder in Children: A Prospective Population Study. JCPP Adv. 2023, 3, e12126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fries, G.R.; Saldana, V.A.; Finnstein, J.; Rein, T. Molecular Pathways of Major Depressive Disorder Converge on the Synapse. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Lu, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, Q.; Shuai, M.; Li, R. Autism Spectrum Disorder-like Behavior Induced in Rat Offspring by Perinatal Exposure to Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 52083–52097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletti, S.; Mazza, M.G.; Benedetti, F. Inflammatory Mediators in Major Depression and Bipolar Disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall, M.; Fellinger, J.; Holzinger, D. The Link between Social Communication and Mental Health from Childhood to Young Adulthood: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 944815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantwell, D.P. Psychiatric Disorder in Children With Speech and Language Retardation: A Critical Review. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1977, 34, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellone, S.; Puricelli, C.; Vurchio, D.; Ronzani, S.; Favini, S.; Maruzzi, A.; Peruzzi, C.; Papa, A.; Spano, A.; Sirchia, F.; et al. The Usefulness of a Targeted Next Generation Sequencing Gene Panel in Providing Molecular Diagnosis to Patients With a Broad Spectrum of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 875182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postma, J.K.; Harrison, M.; Kutcher, S.; Webster, R.J.; Cloutier, M.; Bourque, D.K.; Yu, A.C.; Carter, M.T. The Diagnostic Yield of Genetic and Metabolic Investigations in Syndromic and Nonsyndromic Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder, Global Developmental Delay, or Intellectual Disability from a Dedicated Neurodevelopmental Disorders Genetics Clinic. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2024, 194, e63791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dajani, D.R.; Burrows, C.A.; Odriozola, P.; Baez, A.; Nebel, M.B.; Mostofsky, S.H.; Uddin, L.Q. Investigating Functional Brain Network Integrity Using a Traditional and Novel Diagnostic System for Neurodevelopmental Disorders 2018.

- Mohajer, B.; Masoudi, M.; Ashrafi, A.; Mohammadi, E.; Bayani Ershadi, A.S.; Aarabi, M.H.; Uban, K.A. Structural White Matter Alterations in Male Adults with High Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder and Concurrent Depressive Symptoms; a Diffusion Tensor Imaging Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 259, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iffland, M.; Livingstone, N.; Jorgensen, M.; Hazell, P.; Gillies, D. Pharmacological Intervention for Irritability, Aggression, and Self-Injury in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 10, CD011769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canitano, R.; Scandurra, V. Glutamatergic Agents in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Current Trends. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2014, 8, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Li, E.; Li, L.; Liang, W. Efficacy of Interventions Based on Applied Behavior Analysis for Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Investig. 2020, 17, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabian, H.; Abdulbaki Alshirbaji, T.; Schmid, R.; Wagner-Hartl, V.; Chase, J.G.; Moeller, K. Harnessing Wearable Devices for Emotional Intelligence: Therapeutic Applications in Digital Health. Sensors 2023, 23, 8092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, P.S.; Elchynski, A.L.; Porter-Gill, P.A.; Goodson, B.G.; Scott, M.A.; Lipinski, D.; Seay, A.; Kehn, C.; Balmakund, T.; Schaefer, G.B. Multidisciplinary Consulting Team for Complicated Cases of Neurodevelopmental and Neurobehavioral Disorders: Assessing the Opportunities and Challenges of Integrating Pharmacogenomics into a Team Setting. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Hyde, C.; Saravanapandian, V.; Wilson, R.; Distefano, C.; Besterman, A.; Jeste, S. The Diagnostic Journey of Genetically Defined Neurodevelopmental Disorders. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2022, 14, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finucane, B.M.; Ledbetter, D.H.; Vorstman, J.A. Diagnostic Genetic Testing for Neurodevelopmental Psychiatric Disorders: Closing the Gap between Recommendation and Clinical Implementation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2021, 68, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loader, S.J.; Brouwers, N.; Burke, L.M. Neurodevelopmental Therapy Adherence in Australian Parent-Child Dyads: The Impact of Parental Stress. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 36, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamah, S.; Aghazarian, A.; Nazaryan, A.; Hajnal, A.; Covasa, M. Role of Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Regulating Dopaminergic Signaling. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Hoshina, N.; Zhang, C.; Ma, Y.; Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, D.; Bergen, S.E.; Landén, M.; Hultman, C.M.; et al. The Protocadherin 17 Gene Affects Cognition, Personality, Amygdala Structure and Function, Synapse Development and Risk of Major Mood Disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).