Submitted:

01 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Integrated Energy Systems

2.1. Definition of IESs

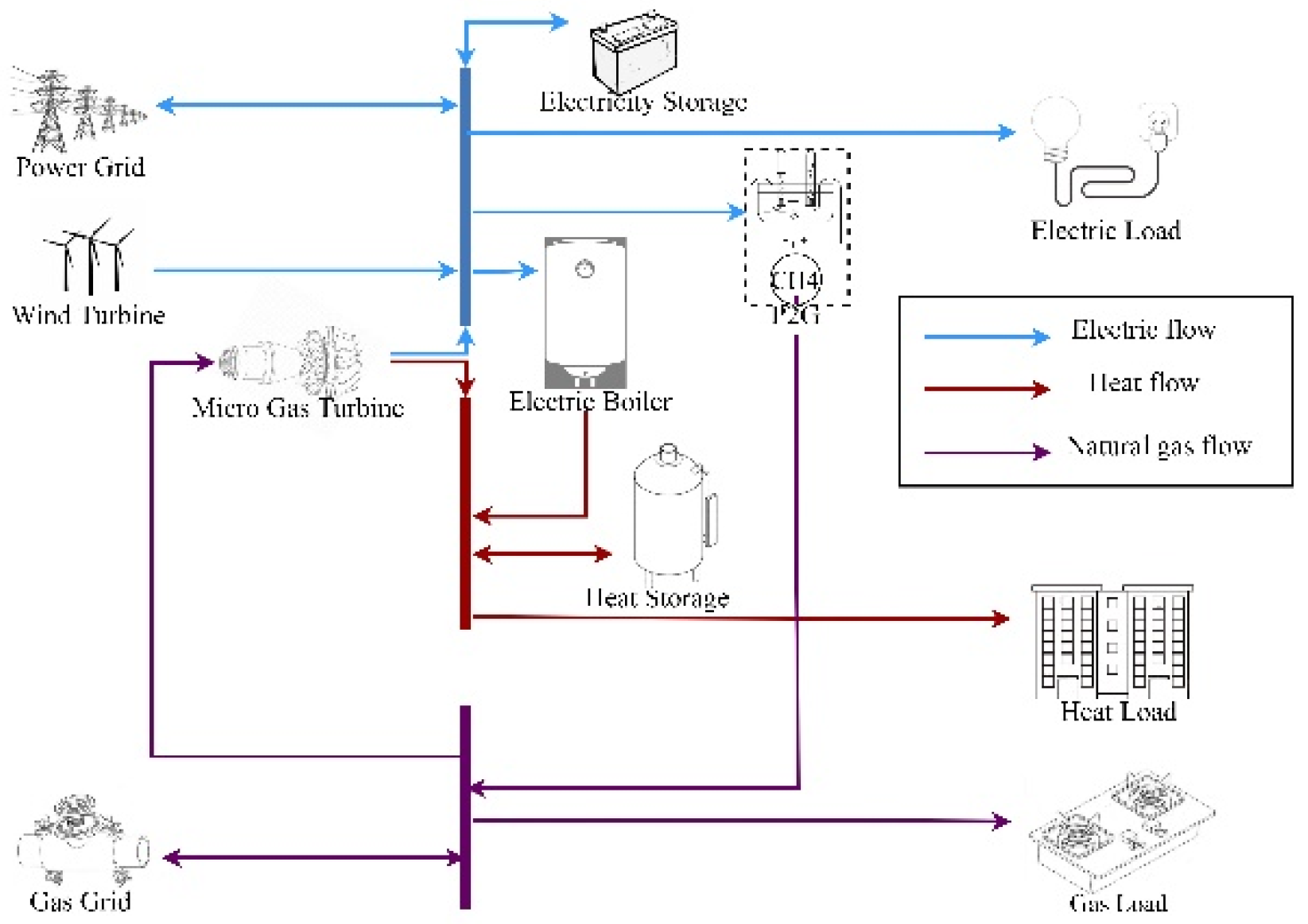

2.2. Structure of Integrated Energy Systems

3. OPF Decoupling Algorithm of IESs

3.1. Overview of OPF Problems in IESs

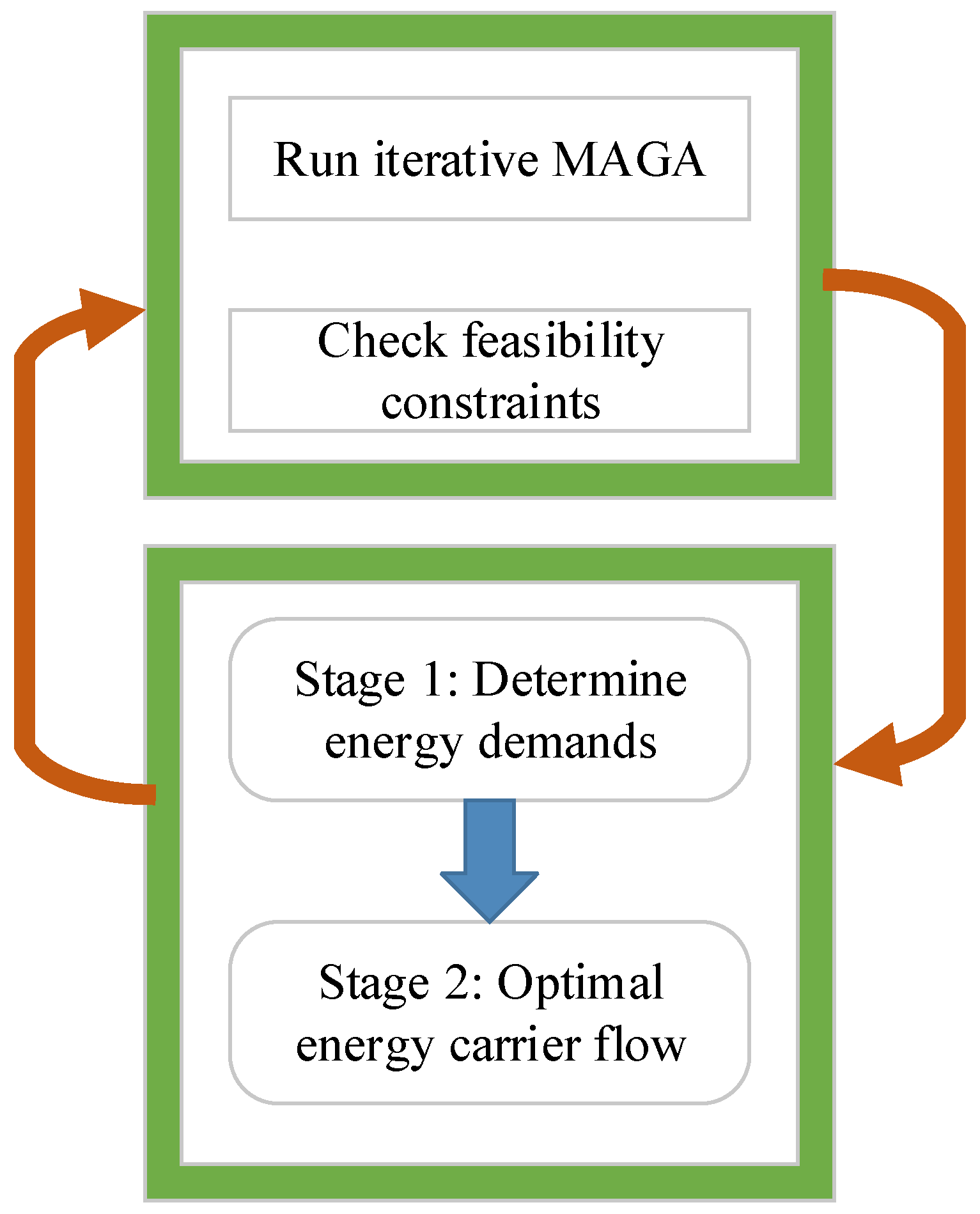

3.2. General Structure after Decoupling the MCOPF

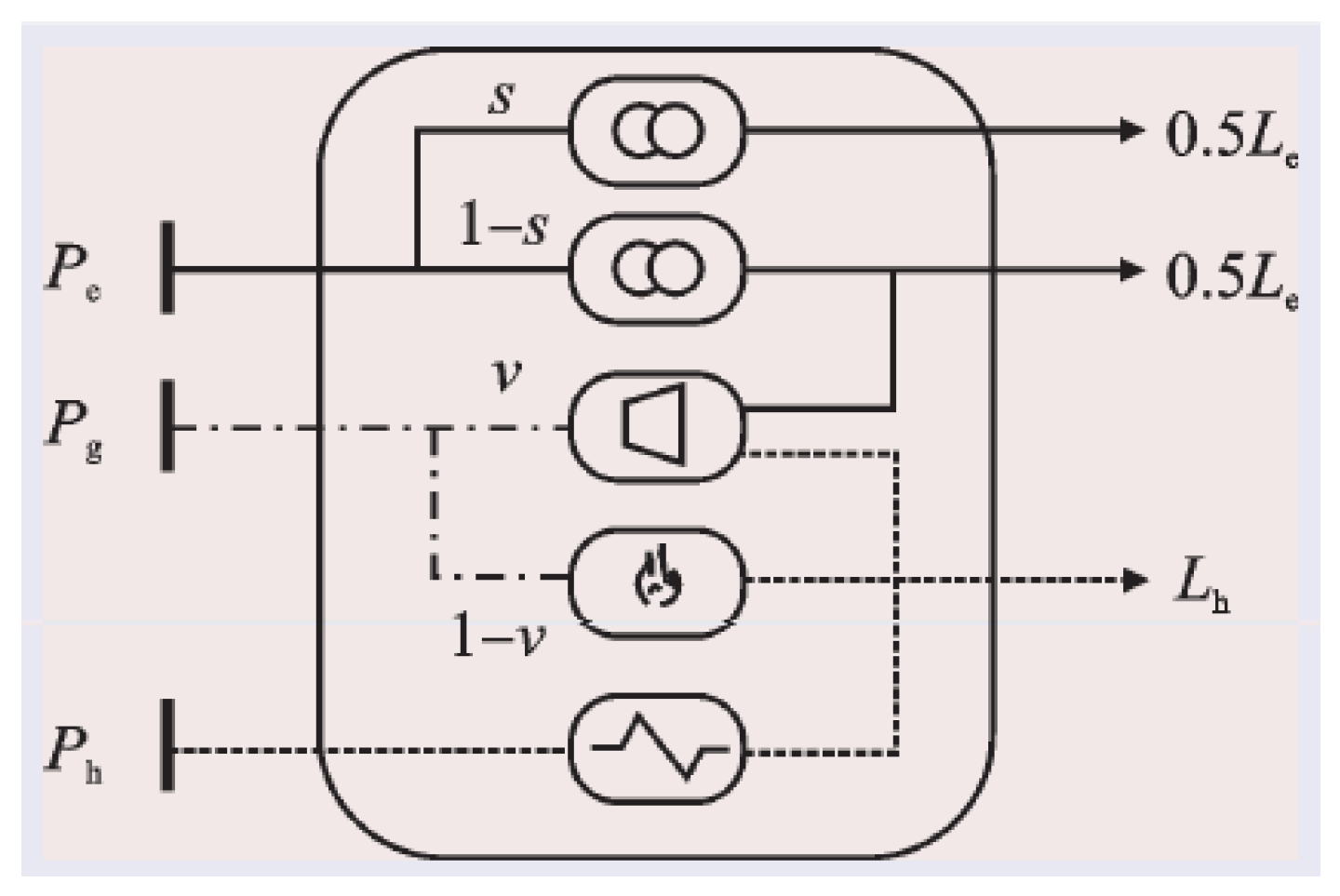

3.3. Mathematical Representation of the MCOPF

4. Gas-Electric IES OPF Model

4.1. Gas-Electric IESs

4.2. Process and Steps

5. OPF Calculation Methods for IESs

5.1. Classical Algorithms

5.2. Intelligent Algorithms

5.3. Other Algorithms

6. Challenges and Future Prospects

6.1. Challenges

6.1.1. Renewable Energy Integration

6.1.2. Electric Vehicle (EV) Integration

6.1.3. Cybersecurity Threats

6.2. Future Prospects

6.2.1. Advanced Predictive and Adaptive Control Systems

6.2.2. Enhanced Energy Storage Solutions

6.2.3. Regulatory and Policy Development

7. Conclusions

References

- Bie Z., Wang X., Hu Y. Overview and Prospects of Energy Internet Planning Research. Proceedings of the Chinese Society of Electrical Engineering, 2017, 37(22): 6445-6462.

- Dong Z., Zhao J., Wen F., et al. From Smart Grids to Energy Internet: Basic Concepts and Research Framework. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2014, 38(15): 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Liu C, Zhou X, et al. Hierarchical optimal dispatch of active distribution networks considering flexibility auxiliary service of multi-community integrated energy systems. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, 2024: 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Ai Q., Hao R. Key Technologies and Challenges for Multi-Energy Complementary and Integrated Optimization Energy Systems. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2018, 42(04): 2-10+46.

- Li Y, Han M, Yang Z, et al. Coordinating flexible demand response and renewable uncertainties for scheduling of community integrated energy systems with an electric vehicle charging station: A bi-level approach. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, 2021, 12(4): 2321-2331. [CrossRef]

- Jia H., Wang D., Xu X., et al. Research on Several Issues of Regional Integrated Energy Systems. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2015, 39(07): 198-207. [CrossRef]

- Wu J. Drivers and Current Status of Integrated Energy System Development in Europe. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2016, 40(05): 1-7.

- Congress of United States. Energy independence and security ACT of 2007 [EB/OL]. (2004-08-01) [2020-03-19]. Available online: http:// www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS- 110hr6enrl pdf/BILLS-110hr6enr.pdf.

- Natural Resources Canada. Integrated community energy solutions: a roadmap for action [R/OL].(2009-09-01) [2020-03-19]. Available online: http://oee.nrcan.gc. ca/sites/oee.nrcan.gc.ca/files/pdf/publications/cem-cmelices_e.pdf.

- Government of Canada. Combining our energies-integrated energy systems for Canadian communities[R/OL]. (2009-06-01) [2020-03-19]. Available online: http://publications.gc.calcollections/collection_2009/parl/xc49-402-1-1-O1E.pdf.

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.The strategic energy plan of Japan[EB/OL]. (2010-06-O1) [2020-03-19]. Available online: http://www.meti.go.jplenglish/press/data/pdf/20100618_08a. pdf.

- Li Y, Wang C, Li G, et al. Improving operational flexibility of integrated energy system with uncertain renewable generations considering thermal inertia of buildings. Energy Conversion and Management, 2020, 207: 112526. [CrossRef]

- Zhu N. Development Context, Technical Characteristics, and Future Trends of Integrated Energy. China Energy, 2019, 41(10): 18-22+43.

- Luo C. Germany’s Adoption of Power-to-Gas Technology for Decarbonization. International Energy, 2017, 22(04): 20-26.

- National Energy Administration. Public Announcement of the Selection Results of the First Batch of Multi-Energy Complementary Integrated Optimization Demonstration Projects [EB/OL]. (2016-12-26) [2020-03-19]. Available online: http://www.nea.gov.cn/2016-12/26/c_135933772.htm.

- Feng H. Latest Developments, Trends, and Challenges in the Competitive Landscape of the Integrated Energy Service Market. Electrical Industry, 2019, (12): 51-61.

- Jiakun Fang, Qing Zeng, Xiaomeng Ai, et al. Dynamic Optimal Energy Flow in the Integrated Natural Gas and Electrical Power Systems. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, 2018, 9 (1): 188-198. [CrossRef]

- Cao M., Shao C., Hu B., et al. Reliability assessment of integrated energy systems considering emergency dispatch based on dynamic optimal energy flow. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, 2022, 13(1): 290-301. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z., Tang Y., Qiao B., et al. Optimal Power Flow and Its Environmental Enhancement Research in Gas-Electric Integrated Energy Systems. Proceedings of the Chinese Society of Electrical Engineering, 2018, 38(S1): 111-120.

- Liu S., Dai S., Hu L., et al. Research on Optimal Power Flow in Electric-Heating Combined Systems. Power System Technology, 2018, 42(01): 285-290.

- Moeini-Aghtaie M, Abbaspour A, Fotuhi-Firuzabad M, et al. A decomposed solution to multiple-energy carriers optimal power flow. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 2014, 29 (2): 707-716. [CrossRef]

- Lin W., Jin X., Mu Y., et al. Multi-objective Optimal Hybrid Power Flow Algorithm for Regional Integrated Energy Systems. Proceedings of the Chinese Society of Electrical Engineering, 2017, 37(20): 5829-5839.

- Li Y, Han M, Shahidehpour M, et al. Data-driven distributionally robust scheduling of community integrated energy systems with uncertain renewable generations considering integrated demand response. Applied Energy, 2023, 335: 120749. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Ma W, Li Y, et al. Enhancing cyber-resilience in integrated energy system scheduling with demand response using deep reinforcement learning. Applied Energy, 2025, 379:124831. [CrossRef]

- BOHM B, HA S, KIM W, et al. Simple models for operational optimisation[R]. Denmark: Technical University of Denmark (DTU), Fraunhofer-Institute for Environmental, Safety and Energy Technology (UMS- ICHT), Korea District Heating Corporation (KDHC), 2002: 3-6.

- STEER KCB, WIRTH A, HALGAMUGE S K. Control period selection for improved operating performance in district heating networks. Energy and Buildings, 2011, 43(2/3): 605-613. [CrossRef]

- Yang J., Liu J., Zhang B. Research on Fault Detection for Hospital Backup Power Systems Based on Hydrogen Fuel Engines. Grid and Clean Energy, 2017, 33(01): 150-153.

- Zhang Z., Guo X., Zhang X., et al. Strategy for Smoothing Wind Power Fluctuations Using Energy Storage Batteries. Power System Protection and Control, 2017, 45(03): 62-68.

- Jia C., Yang C., Shi Y., et al. Research on Enhancing Wind Turbine Penetration through Coordinated Control of Photovoltaic Inverters. Grid and Clean Energy, 2017, 33(03): 131-136.

- Li Y, Wang B, Yang Z, et al. Optimal scheduling of integrated demand response-enabled community-integrated energy systems in uncertain environments. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, 2021, 58(2): 2640-2651. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Study on Analysis Methods for Hybrid Natural Gas-Electric Power Systems [D]. China Electric Power Research Institute, 2005.

- Li Q, An s, Gedra T W. Solving natural gas load flow problems usingelectric load flow techniques[C]// Proceedings of the North American Power Symposium. Rolla, USA, 2003:1-7.

- Martinez-Mares A, Fuerte-Esquivel CR. A Unified gas and power flow analysis in natural gas and electricity coupled networks. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 2012, 27(4):2156-2166. [CrossRef]

- Wang W., Wang D., Jia H., et al. Steady-State Analysis of Electric-Gas Regional Integrated Energy Systems Considering Natural Gas Network Status. Proceedings of the Chinese Society of Electrical Engineering, 2017, 37(05): 1293-1305.

- Zeng Q, Fang J, Li J, et al. Steady-state analysis of the integrated natural gas and electric power system with bi-directional energy conversion. Applied Energy, 2016(184):1483-1492. [CrossRef]

- An S, Li Q, Gedra T W. Natural gas and electricity optimal power flow[C]//Proceedings of the IEEE PES Transmission and Distribution Conference and Exposition. Dallas, TX, USA:IEEE, 2003: 138-143.

- Unsihuay C, Lima J W M, Souza ACZD. Modeling the integrated natural gas and electricity optimal power flow [C]/Power Engineering Society General Meeting, IEEE, 2007: 1-7.

- Sun G., Chen S., Wei Z., et al. Probabilistic Optimal Power Flow in Electric-Gas Interconnected Systems Considering Correlations. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2015, 39(21): 11-17.

- Qiu J, Dong Z Y, Zhao J H, et al. Low carbon oriented expansion planning of integrated gas and power systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 2015, 30(2): 1035-1046.

- Li Y, Bu F, Gao J, et al. Optimal dispatch of low-carbon integrated energy system considering nuclear heating and carbon trading. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2022, 378: 134540. [CrossRef]

- Miao M., Li Y., Cao Y., et al. Optimization Strategy for Multi-Energy Systems with AC/DC Hybrid Supply Considering Environmental Factors. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2018, 42(04): 128-134.

- Wang, X. Modern Power System Analysis [M]. Science Press, 2003: 120-123.

- Wei H, Sasaki H, Kubokawa J, et al. An interior point nonlinear programming for optimal power flow problems with a novel data structure. IEEE Transactions on Power System, 1997, 13(3): 870-877. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T. Application Research on Environmental Cost Accounting in Thermal Power Enterprises [D]. Zhejiang University of Technology, 2013.

- Jia Y., Zhang F. Study on Dual-Layer Optimization Allocation of Multi-Energy Storage Under Distributed Wind Power Integration in Regional Integrated Energy Systems. Renewable Energy, 2019, 37(10): 1524-1532.

- Wang Z., Tang Y., Qiao B., et al. Research on Optimal Power Flow and Environmental Efficiency in Gas-Electric Integrated Energy Systems. Proceedings of the Chinese Society of Electrical Engineering, 2018, 38(S1): 111-120.

- Zhang Y., Wang X., Jing H., et al. Optimal Energy Flow Calculation Methods Considering Heating System Modeling in Integrated Energy Systems. Transactions of China Electrotechnical Society, 2019, 34(03): 562-570.

- Liu S., Dai S., Hu L., et al. Research on Optimal Power Flow in Electric-Heating Combined Systems. Power System Technology, 2018, 42(01): 285-290.

- Yang, L. Research on Flow Optimization Methods for Hybrid Energy Systems of Electricity, Gas, and Heat [D]. Northeastern University, 2017.

- Xu, X. Research on Modeling, Simulation, and Energy Management of Electric/Gas/Heat Micro Energy Systems [D]. Tianjin University, 2014.

- Zheng, B. Research on Distributed Multi-Objective Energy Flow Optimization Methods Under the Context of Integrated Energy Systems [D]. South China University of Technology, 2019.

- MOEINI-AGHTAIE M, ABBASPOUR A, FOTUHI- FIRUZABAD M, et al. A decomposed solution to multiple-energy carriers optimal power flow. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 2014, 29(2): 707-716. [CrossRef]

- Bao Y., Zhang Q., Zhang M., et al. Optimal Power Flow Decoupling Algorithm Based on Integrated Energy Systems. Grid and Clean Energy, 2018, 34(06): 80-86.

- Lin W., Jin X., Mu Y., et al. Multi-Objective Optimal Hybrid Power Flow Algorithm for Regional Integrated Energy Systems. Proceedings of the Chinese Society of Electrical Engineering, 2017, 37(20): 5829-5839.

- Jin, X., Mu Y., Jia H., et al. Optimal Hybrid Power Flow Calculation Considering Distribution Network Reconstruction in Regional Integrated Energy Systems. Automation of Electric Power Systems, 2017, 41(01): 18-24+56.

- Liang, Z., Lin S., Liu M. A Synchronous ADMM Method for Solving Distributed Optimal Power Flow in Interconnected AC/DC Grids. Power System Protection and Control, 2018, 46(23): 28-36.

- Liang, Z. Synchronous Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers for Distributed Optimal Power Flow Calculation in Modern Energy Systems [D]. South China University of Technology, 2018.

- CHANG Y, P. Integration of SQP and PSO for optimalplanning of harmonic filters. ExpertSystems withApplications, 2010, 37(3):2522-2530.

- PAN Z, GUO Q, SUN H. Interactions of district electricity and heating systems considering time-scale characteristics based on quasi-steady multi-energy flow. Applied Energy, 2016, 167: 230-243. [CrossRef]

- LIU X, JENKINS N, WU J, et al. Combined analysis of electricity and heat networks. Energy Procedia, 2014, 61: 155-159. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Yang Z, Li G, et al. Optimal scheduling of an isolated microgrid with battery storage considering load and renewable generation uncertainties. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 2019, 66(2): 1565-1575. [CrossRef]

- Kou L, et al. Review on monitoring, operation and maintenance of smart offshore wind farms. Sensors, 2022, 22(8): 2822. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wang R, Li Y, et al. Wind power forecasting considering data privacy protection: A federated deep reinforcement learning approach. Applied Energy, 2023, 329: 120291. [CrossRef]

- Datta U, Kalam A, Shi J. A review of key functionalities of battery energy storage system in renewable energy integrated power systems. Energy Storage, 2021, 3(5): e224. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wang C, Li G, et al. Optimal scheduling of integrated demand response-enabled integrated energy systems with uncertain renewable generations: A Stackelberg game approach. Energy Conversion and Management, 2021, 235: 113996. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Wei, Z., Sun, G., et al. (2016). Identifying optimal energy flow solvability in electricity-gas integrated energy systems. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, 8(2), 846-854. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Li J, Wang Y. Privacy-preserving spatiotemporal scenario generation of renewable energies: A federated deep generative learning approach. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 2021, 18(4): 2310-2320. [CrossRef]

- Amusat O O, Shearing P R, Fraga E S. Optimal integrated energy systems design incorporating variable renewable energy sources. Computers & Chemical Engineering, 2016, 95: 21-37. [CrossRef]

- Gong X, Li X, Zhong Z. Strategic bidding of hydrogen-wind-photovoltaic energy system in integrated energy and flexible ramping markets with renewable energy uncertainty. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2024, 80: 1406-1423. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wang B, Yang Z, et al. Hierarchical stochastic scheduling of multi-community integrated energy systems in uncertain environments via Stackelberg game. Applied Energy, 2022, 308: 118392. [CrossRef]

- Long X, et al. Collaborative response of data center coupled with hydrogen storage system for renewable energy absorption. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, 2024, 15(2): 986–1000. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., et al. PMU measurements-based short-term voltage stability assessment of power systems via deep transfer learning. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 2023, 72: 2526111. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim A, Jiang F. The electric vehicle energy management: An overview of the energy system and related modeling and simulation. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2021, 144: 111049. [CrossRef]

- Taghizad-Tavana K, Alizadeh A, Ghanbari-Ghalehjoughi M, et al. A comprehensive review of electric vehicles in energy systems: Integration with renewable energy sources, charging levels, different types, and standards. Energies, 2023, 16(2): 630. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Yang Z, Li G, et al. Optimal scheduling of isolated microgrid with an electric vehicle battery swapping station in multi-stakeholder scenarios: A bi-level programming approach via real-time pricing. Applied energy, 2018, 232: 54-68. [CrossRef]

- Cao J, Crozier C, McCulloch M, et al. Optimal design and operation of a low carbon community based multi-energy systems considering EV integration. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy, 2018, 10(3): 1217-1226. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, He H, Jing R, et al. Energy management in integrated energy system with electric vehicles as mobile energy storage: An approach using bi-level deep reinforcement learning. Energy, 2024, 307: 132757. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, He S, Li Y, et al. Probabilistic charging power forecast of EVCS: Reinforcement learning assisted deep learning approach. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles, 2022, 8(1): 344-357. [CrossRef]

- Tabari M, Yazdani A. An energy management strategy for a DC distribution system for power system integration of plug-in electric vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 2015, 7(2): 659-668. [CrossRef]

- Noorollahi Y, Golshanfard A, Aligholian A, et al. Sustainable energy system planning for an industrial zone by integrating electric vehicles as energy storage. Journal of Energy Storage, 2020, 30: 101553. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad A, Zuhaib M, Ashraf I, et al. Integration of electric vehicles and energy storage system in home energy management system with home to grid capability. Energies, 2021, 14(24): 8557. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Li K. Incorporating demand response of electric vehicles in scheduling of isolated microgrids with renewables using a bi-level programming approach. IEEE Access, 2019, 7: 116256-116266. [CrossRef]

- Atia R, Yamada N. More accurate sizing of renewable energy sources under high levels of electric vehicle integration. Renewable Energy, 2015, 81: 918-925. [CrossRef]

- Bo X, Chen X, Li H, et al. Modeling method for the coupling relations of microgrid cyber-physical systems driven by hybrid spatiotemporal events. IEEE Access, 2021, 9: 19619-19631. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, et al. Coordinated cyber-attack detection model of cyber-physical power system based on the operating state data link. Frontiers in Energy Research, 2021, 9: 666130. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Cao J, Xu Y, et al. Deep learning based on Transformer architecture for power system short-term voltage stability assessment with class imbalance. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2024, 189: 113913. [CrossRef]

- Qu Z, Xie Q, Liu Y, et al. Power cyber-physical system risk area prediction using dependent Markov chain and improved grey wolf optimization. IEEE Access, 2020, 8: 82844-82854. [CrossRef]

- Qu Z, Zhang Y, Qu N, et al. Method for quantitative estimation of the risk propagation threshold in electric power CPS based on seepage probability. IEEE Access, 2018, 6: 68813-68823. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, et al. Method for extracting patterns of coordinated network attacks on electric power CPS based on temporal–topological correlation. IEEE Access, 2020, 8: 57260-57272. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Gu S, Wang Y, et al. Stacked autoencoder framework of false data injection attack detection in smart grid. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2021, 2021(1): 2014345. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wei X, Li Y, et al. Detection of false data injection attacks in smart grid: A secure federated deep learning approach. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 2022, 13(6): 4862-4872. [CrossRef]

- Qu Z, Bo X, Yu T, et al. Active and passive hybrid detection method for power CPS false data injection attacks with improved AKF and GRU-CNN. IET Renewable Power Generation, 2022, 16(7): 1490-1508. [CrossRef]

- Qu Z, et al. Localization of dummy data injection attacks in power systems considering incomplete topological information: A spatio-temporal graph wavelet convolutional neural network approach. Applied Energy, 2024, 360: 122736. [CrossRef]

- Xie L, Huang T, Kumar P R, et al. On an information and control architecture for future electric energy systems. Proceedings of the IEEE, 2022, 110(12): 1940-1962. [CrossRef]

- Juma S A, Ayeng’o S P, Kimambo C Z M. A review of control strategies for optimized microgrid operations. IET Renewable Power Generation, 2024, 18(14): 2785-2818.

- Li Y, Feng B, Wang B, et al. Joint planning of distributed generations and energy storage in active distribution networks: A Bi-Level programming approach. Energy, 2022, 245: 123226. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Zhang Y, Xue L, et al. Research on planning optimization of integrated energy system based on the differential features of hybrid energy storage system. Journal of Energy Storage, 2022, 55: 105368. [CrossRef]

- Ding Y, Xu Q, Yang B. Optimal configuration of hybrid energy storage in integrated energy system. Energy Reports, 2020, 6: 739-744. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Niu D, Wu M, et al. Research on battery energy storage as backup power in the operation optimization of a regional integrated energy system. Energies, 2018, 11(11): 2990. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Feng B, Li G, et al. Optimal distributed generation planning in active distribution networks considering integration of energy storage. Applied energy, 2018, 210: 1073-1081. [CrossRef]

- Kotowicz J, Uchman W. Analysis of the integrated energy system in residential scale: Photovoltaics, micro-cogeneration and electrical energy storage. Energy, 2021, 227: 120469. [CrossRef]

- Shi Y, Zeng Y, Engo J, et al. Leveraging inter-firm influence in the diffusion of energy efficiency technologies: An agent-based model. Applied Energy, 2020, 263: 114641. [CrossRef]

- Lund, H., & Münster, E. Integrated energy systems and local energy markets. Energy Policy, 2006, 34(10): 1152-1160. [CrossRef]

- Siano, P. Assessing the impact of incentive regulation for innovation on RES integration. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 2014, 29(5): 2499-2508. [CrossRef]

- Agupugo C P, Ajayi A O, Nwanevu C, et al. Policy and regulatory framework supporting renewable energy microgrids and energy storage systems. Eng. Sci. Technol. J, 2022, 5: 2589-2615. [CrossRef]

- Kerscher S, Arboleya P. The key role of aggregators in the energy transition under the latest European regulatory framework. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 2022, 134: 107361. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).