Submitted:

14 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Principles of Application of Neural Networks in Power Systems

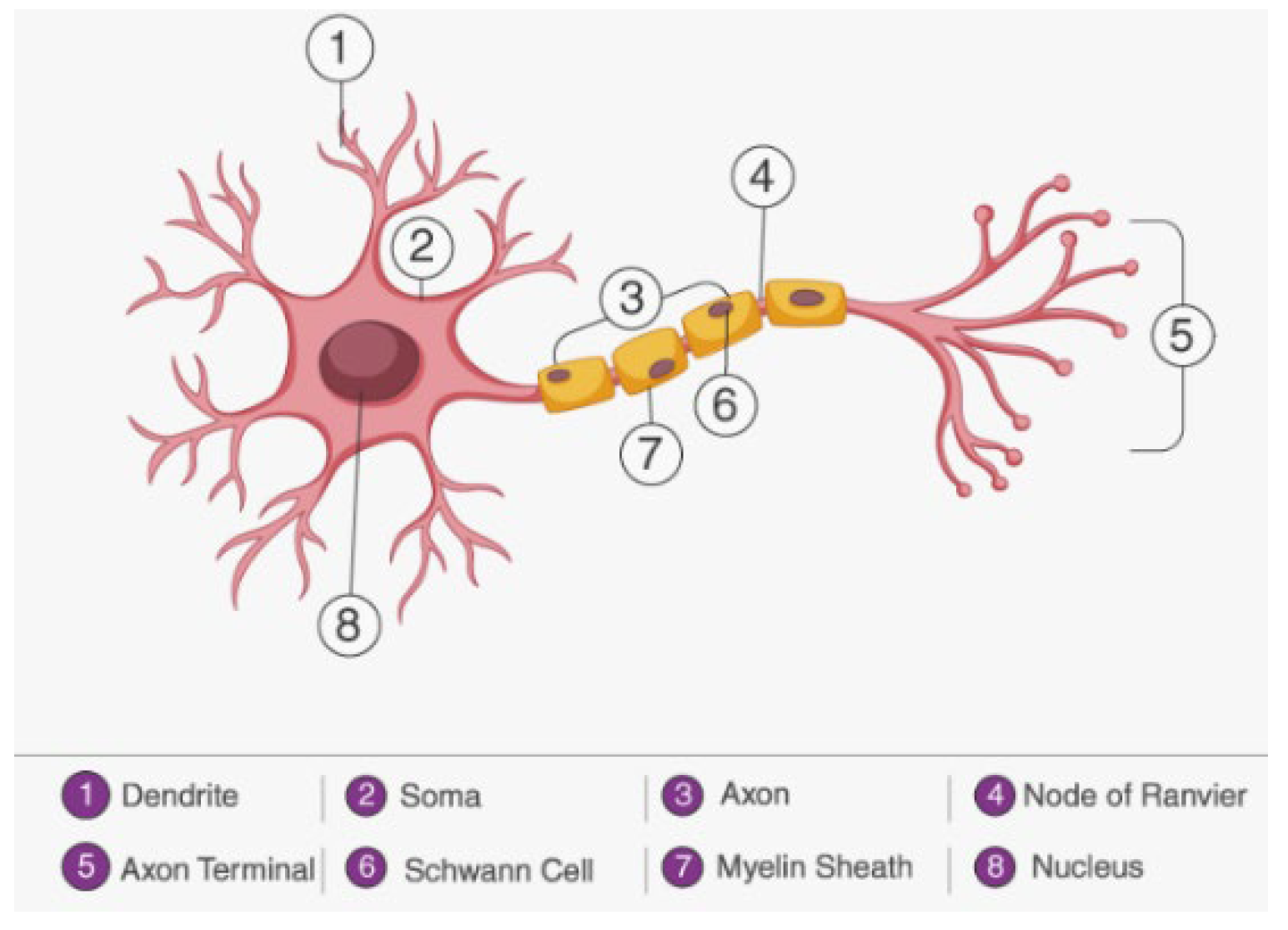

2.1. Fundamentals of Neural Networks

2.2. Application of Neural Networks in Power Systems

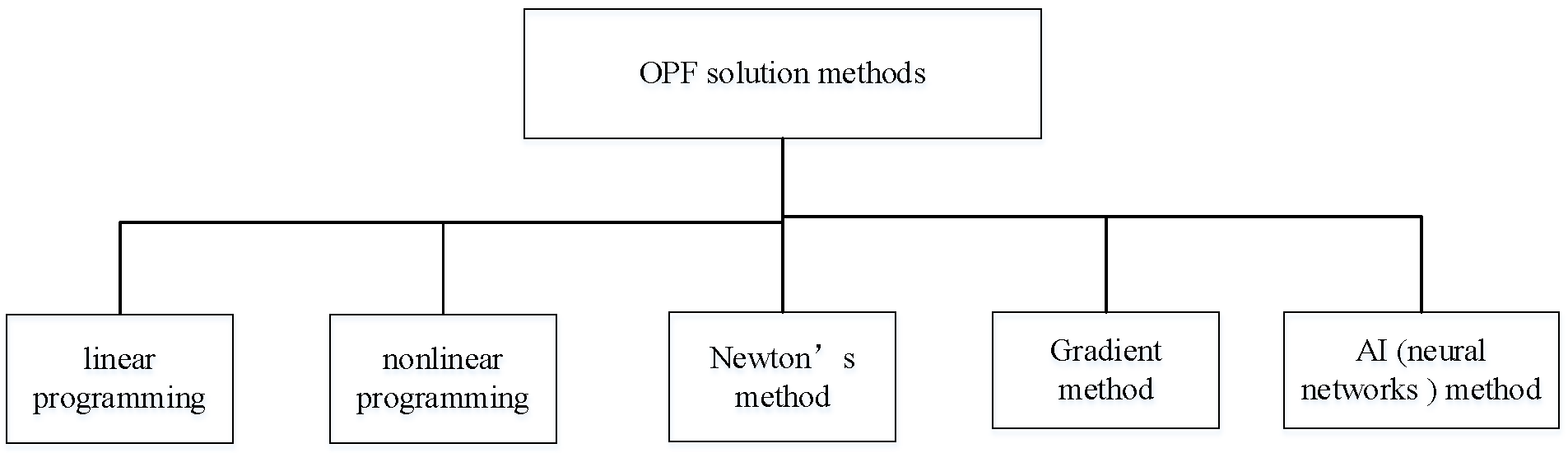

3. Current Status of Neural Network Applications in OPF Calculations

3.1. Role of Neural Networks in OPF Calculations

3.1.1. Deep Learning-Based OPF Models

- CNNs have been applied in OPF calculations to capture spatial relationships in grid topology and to analyze power flow patterns across different areas of the system. By learning hierarchical representations of system behavior, CNNs can provide more accurate predictions of how changes in one part of the grid affect the rest of the system [30].

- LSTMs are particularly suited for OPF because of their ability to model temporal dependencies and handle sequential data. In power systems, load demands and generation levels vary over time, and LSTMs excel at predicting future power flow conditions based on past data. This ability is critical for real-time scheduling and forecasting in power grids with high penetrations of intermittent renewable energy sources [31].

- Transformers, originally designed for natural language processing, have recently gained attention in power systems for their ability to capture long-range dependencies in data, making them useful for optimizing power flow in large, highly interconnected grids. Transformers can process multiple data streams simultaneously, enhancing the efficiency and robustness of the optimization process [32].

3.1.2. Data-Driven Optimization Methods

3.1.3. Real-Time Scheduling and Response Capabilities

3.2. Suitable Network Structures for OPF

3.2.1. Feedforward Neural Networks (FNNs)

3.2.2. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)

3.2.3. Convolutional Neural Networks

3.2.4. Integrating Multiple Neural Network Architectures

4. Challenges and Future Development Trends

4.1. Current Challenges

4.1.1. Data Quality and Availability

4.1.2. Complexity and Computational Efficiency

4.1.3. Impact of Renewable Energy Integration

4.1.4. Challenges of Cyber Attacks

4.1.5. Challenges Posed by Electric Vehicle Integration

4.1.6. Challenges Posed by Power Electronics and HVDC Integration

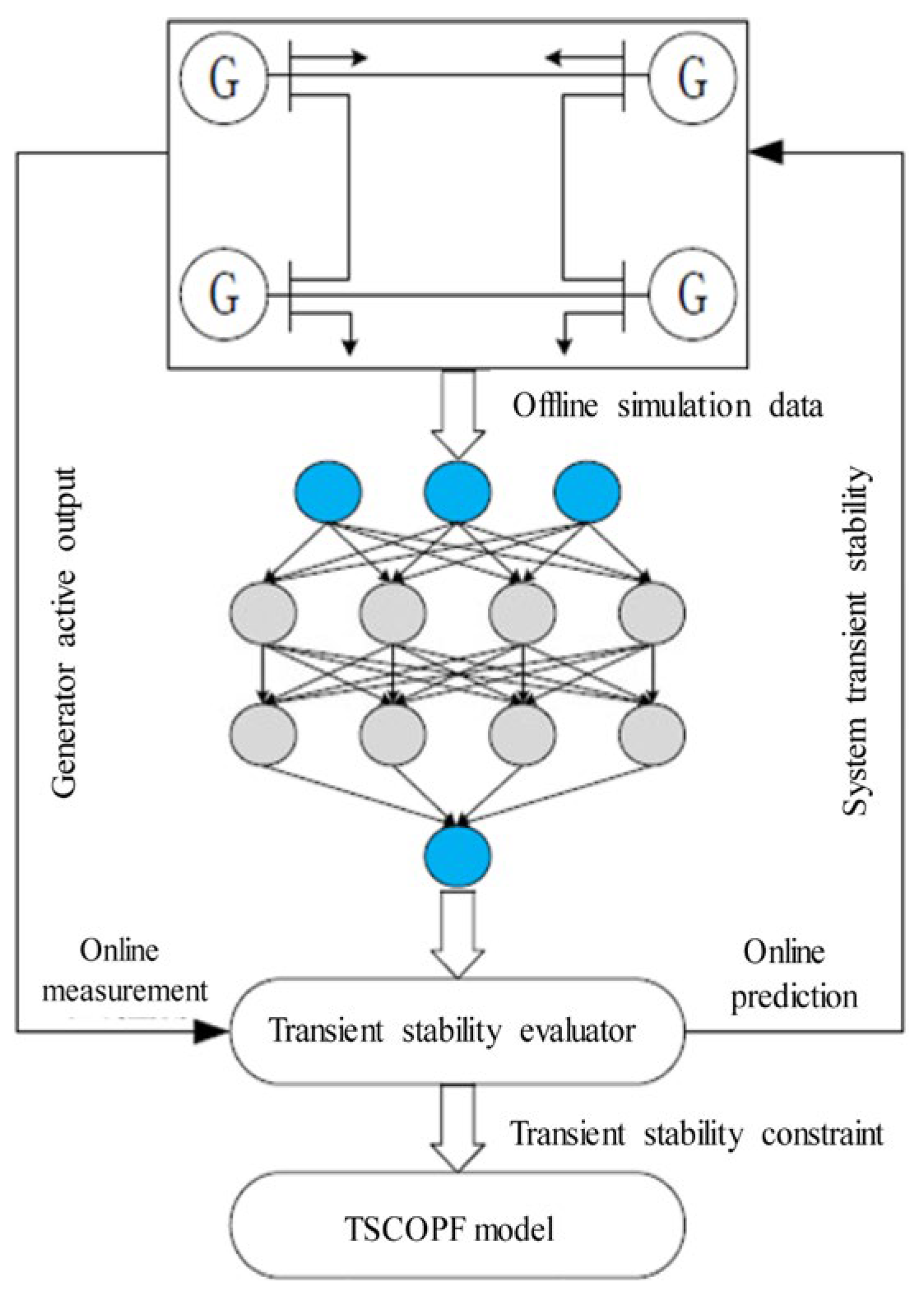

4.1.7. Challenges of Stability-Constrained OPF

4.2. Future Development Directions

4.2.1. Technological Enhancements for Resilience

4.2.2. Leveraging Advanced Learning Algorithms

4.2.3. Adaptive and Predictive Modeling for EV Integration

4.2.4. Advanced Control Strategies for Power Electronics and HVDC Systems

4.2.5. Strategies for Improving Stability-Constrained OPF

5. Conclusions

References

- Chen, S.; Chai, Q.; Li, Y.; Hu, L. A review of flow and optimal flow calculation models and methods in integrated energy systems. Thermal Power Generation 2020, 49, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, D.; Liu, M.; Xu, L. A review and prospect of research on coordination optimization of transmission and distribution in power systems with distributed energy resources. Southern Power System Technology 2023, 17, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Yang, D.; Jin, X.; Hong, W.; Ye, S.; Zhao, X. A review of flow analysis models and methods in integrated smart energy systems. Comprehensive Smart Energy 2023, 45, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, B. A multi-layer optimization scheduling method for AC/DC hybrid distribution networks based on mixed integer linear programming. Guangdong Electric Power 2023, 36, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S. (2019). Research on non-convex economic dispatch problems in power systems based on linear mixed integer programming and nonlinear programming (Master's thesis). Guangxi University.

- Zhang, G.; Wang, C.; Wang, H. A review of multi-solution algorithms for voltage stability in power systems. Journal of Power System and Its Automation 2017, 29, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Guo, Y. Power flow calculation in the assessment of reliability and static safety of distribution systems. Journal of Tsinghua University (Science and Technology), 2000; 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, J. , et al. (1955). A proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence. AI Magazine.

- McCulloch, W.; Pitts, W. (1943). A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics.

- Shi, Z.; Yu, T.; Zhao, Q. , et al. Comparison of algorithms for an electronic nose in identifying liquors. Journal of Bionic Engineering 2008, 5, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Zhu, D.; Li, Y. Data driven based dynamic correction prediction model for NOx emission of coal fired boiler. Proceedings of the CSEE 2022, 42, 5182–5193. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Qu, N. , et al. (2024). Extraction of typical operating scenarios of new power system based on deep time series aggregation. CAAI Transactions on Intelligence Technology (Early Access). [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Wang, C.; Bi, T. Optimal energy flow calculation in electric-gas integrated energy systems based on a dynamic proxy model for gas networks. Journal of Chinese Electrical Engineering 2023, 43, 3415–3429. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wei, X.; Li, Y. , et al. Detection of false data injection attacks in smart grid: A secure federated deep learning approach. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2022, 13, 4862–4872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; He, Y.; Zhang, B. Study on long-term electric power load combination forecast model based on regression neural networks. Statistics & Decision 2007, 24, 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kundur, P.; Balu, N.J.; Lauby, M.G. (1994). Power system stability and control. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Fang, Z.; Zhao, D.; et al. Nonintrusive appliance identification with appliance-specific networks. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2020, 56, 3443–3452. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. , He, S., Li, Y., et al. Renewable energy absorption oriented many-objective probabilistic optimal power flow. IEEE Transactions on Network Science and Engineering 2024, 11, 5432–5448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, H.; Moser, A.; Fuchs, E.F. A review of recent advances in optimal power flow. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2009, 24, 1290–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, B.; Hu, Y.; Huang, G.; Jiang, W.; Xu, H.; Guo, C. Review of novel power system scheduling optimization methods based on deep reinforcement learning. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2023, 47, 187–199. [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch, M.; Trost, T.; Sterner, M. Optimal use of power-to-gas energy storage systems in an 85% renewable energy scenario. Energy Procedia 2014, 46, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X. Optimal scheduling of a gas-electricity interconnected network considering combined heat and power. Power System Protection and Control 2019, 47, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D. , et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, S. , et al. Federated multiagent deep reinforcement learning approach via physics-informed reward for multimicrogrid energy management. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024, 35, 5902–5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, C. , et al. Optimal power flow calculation in power systems based on Newton's method. Journal of North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power (Natural Science Edition) 2014, 35, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, P. Review of multi-energy flow calculation models and methods in integrated energy systems. Electric Power Construction 2018, 39, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Hu, L. Power and heat combined system power flow calculation. Power Supply and Consumption 2017, 34, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, B.; Mu, Y.; Zhao, B. , et al. Static sensitivity analysis of electric-gas coupled integrated energy systems based on a unified power flow model. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2018, 42, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiler, M.D.; Fergus, R. (2014). Visualizing and understanding convolutional networks. European Conference on Computer Vision.

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Computation 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N. , et al. Attention is all you need. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, X. (2022). Opportunity constrained optimal power flow method and application based on data-driven surrogate models. (Master’s thesis). Chongqing University.

- Zhu, J.; Xu, S.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, L.; Xiong, X.; Wang, C. A new real-time scheduling for power systems based on grid expert strategy imitation learning. Power System Technology 2023, 47, 517–530. [Google Scholar]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Chen, J.; Tang, J. A review of optimal power flow with wind farms and its key technologies. Journal of Guangdong University of Technology 2018, 35, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Hao, X.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Hou, J. A review of parallel computing in power systems. Smart Power 2017, 45, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Zareipour, H. Artificial neural network based optimal power flow: Challenges and solutions. Electric Power Systems Research 2019, 167, 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Zhong, Y.; Xu, H.; Geng, G.; Liu, Z. Bayesian data-driven precise decoupled linear power flow model. Journal of Heilongjiang University of Science and Technology 2023, 33, 250–258. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, H.; Soroudi, A. A review on real-time optimal power flow algorithms: Challenges and methods. Electric Power Systems Research 2017, 144, 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Zareipour, H. Optimal power flow considering real-time data uncertainty. Electric Power Systems Research 2015, 122, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, H.; Li, Z.; Yu, J.; Zheng, J. A review of linearization methods for AC power flow in power systems. Shandong Electric Power Technology 2024, 51, 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Xu, J. Power system flow calculation based on BP neural networks. Electronic World 2018, (12), 70–71. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Wang, H. Decision and control methods for load coordination recovery in large-scale power grids. Journal of Chinese Electrical Engineering 2017, 37, 1666–1676. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Anderson, C.L. A progressive period optimal power flow for systems with high penetration of variable renewable energy sources. Energies 2021, 14, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, M. A. , Hasanien, H. M., Turky, R. A., et al. Opf of modern power systems comprising renewable energy sources using improved chgs optimization algorithm. Energies 2021, 14, 6962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , Cui, Y., et al. Collaborative optimization of multi-microgrids system with shared energy storage based on multi-agent stochastic game and reinforcement learning. Energy 2023, 280, 128182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.S.; Bijwe, P.R. Day-ahead and real time optimal power flow considering renewable energy resources. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2016, 82, 400–408. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Yang, S.; Chen, J. , et al. Low-carbon environment-friendly economic optimal scheduling of multi-energy microgrid with integrated demand response considering waste heat utilization. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 450, 141415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabr, R.A.; Karaki, S.; Korbane, J.A. Robust multi-period OPF with storage and renewables. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2014, 30, 2790–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, A.; Soroudi, A. Stochastic multiperiod OPF model of power systems with HVDC-connected intermittent wind power generation. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery 2013, 29, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Yang, Z. Optimal scheduling of isolated microgrids using automated reinforcement learning-based multi-period forecasting. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2021, 13, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Younesi, A.; Liu, M.V. , et al. AC Optimal Power Flow in Power Systems with Renewable Energy Integration: A Review of Formulations and Case Studies. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 102681–102712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onawale, S.; Wang, X. (2024, May). AC OPF Studies for Smart Grid with Renewable Energy Integration. In 2024 International Conference on Control, Automation and Diagnosis (ICCAD) (pp. 1–6). IEEE.

- Li, Y.; Li, K.; Yang, Z. , et al. Stochastic optimal scheduling of demand response-enabled microgrids with renewable generations: An analytical-heuristic approach. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 330, 129840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, M.A.; Hasanien, H.M.; Al-Durra, A. Solving of optimal power flow problem including renewable energy resources using HEAP optimization algorithm. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 35846–35863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zeng, Z. (2024). Flexible Load Control for Enhancing Renewable Power System Operation. Springer Nature Singapore, Imprint: Springer. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Bo, X.; Yu, T. , et al. Active and passive hybrid detection method for power CPS false data injection attacks with improved AKF and GRU-CNN. IET Renewable Power Generation 2022, 16, 1490–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, M.; Shahidehpour, M. , et al. Data-driven distributionally robust scheduling of community integrated energy systems with uncertain renewable generations considering integrated demand response. Applied Energy 2023, 335, 120749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, Z. , et al. A critical review of data-driven transient stability assessment of power systems: principles, prospects, and challenges. Energies 2021, 14, 7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Wang, J.; Chen, C.; Guo, C. Cyber-constrained optimal power flow model for smart grid resilience enhancement. IEEE transactions on smart grid 2018, 10, 5547–5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, S.; Felemban, M. Rule-based detection of false data injections attacks against optimal power flow in power systems. Sensors 2021, 21, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, L. Dynamic state estimation of generators under cyber attacks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 125253–125267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Dong, Y. , et al. Localization of dummy data injection attacks in power systems considering incomplete topological information: A spatio-temporal graph wavelet convolutional neural network approach. Applied Energy 2024, 360, 122736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Zeng, W.; Chow, M.Y. Resilient distributed DC optimal power flow against data integrity attack. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2016, 9, 3543–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Raman, G.; Peng JC, H.; Ye, Z.S. Resilient consensus-based AC optimal power flow against data integrity attacks using PLC. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2022, 13, 3786–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Xie, Q.; Liu, Y. , et al. Power cyber-physical system risk area prediction using dependent Markov chain and improved grey wolf optimization. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 82844–82854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Datta, A. Impact of stealthy attacks on optimal power flow: A simulink-driven formal analysis. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 2018, 17, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bu, F.; Li, Y. , et al. Optimal scheduling of island integrated energy systems considering multi-uncertainties and hydrothermal simultaneous transmission: A deep reinforcement learning approach. Applied Energy 2023, 333, 120540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Li, B. , et al. Bitcoin transaction strategy construction based on deep reinforcement learning. Applied Soft Computing 2021, 113, 107952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, N. , et al. Method for quantitative estimation of the risk propagation threshold in electric power CPS based on seepage probability. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 68813–68823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y. Two-step many-objective optimal power flow based on knee point-driven evolutionary algorithm. Processes 2018, 6, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G. , et al. Dynamic stochastic optimal power flow of wind power and the electric vehicle integrated power system considering temporal-spatial characteristics. Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy, 2016; 8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, G. , et al. Optimal scheduling of isolated microgrid with an electric vehicle battery swapping station in multi-stakeholder scenarios: A bi-level programming approach via real-time pricing. Applied energy 2018, 232, 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, H.T.; Roy, R. Stochastic optimal power flow incorporating offshore wind farm and electric vehicles. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2015, 69, 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Srithapon, C.; Fuangfoo, P.; Ghosh, P.K.; Siritaratiwat, A.; Chatthaworn, R. Surrogate-Assisted multi-objective probabilistic optimal power flow for distribution network with photovoltaic generation and electric vehicles. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 34395–34414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, M.; Yang, Z. , et al. Coordinating flexible demand response and renewable uncertainties for scheduling of community integrated energy systems with an electric vehicle charging station: A bi-level approach. IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 2021, 12, 2321–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Rojas, A.E.; De Oliveira-De Jesus, P.M.; Alvarez, M. Distribution network electric vehicle hosting capacity enhancement using an optimal power flow formulation. Electrical Engineering 2022, 104, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, M.V.; Swarnasri, K.; Muthukumar, P.; Babu PV, K. Improved Skill Optimization Algorithm Based Optimal Power Flow Considering Open-Access Trading of Wind Farms and Electric Vehicle Fleets. International Journal of Intelligent Engineering & Systems 2024, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; He, S.; Li, Y. , et al. Probabilistic charging power forecast of EVCS: Reinforcement learning assisted deep learning approach. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2022, 8, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, J.S.; Arias, N.B.; Vergara, P.P. , et al. Estimating risk-aware flexibility areas for electric vehicle charging pools via ac stochastic optimal power flow. Journal of Modern Power Systems and Clean Energy 2022, 11, 1247–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Duan, C.; Zhang, C.K.; Jiang, L.; Mao, C.; Wang, D. ADMM-based multiperiod optimal power flow considering plug-in electric vehicles charging. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2017, 33, 3886–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, K. Incorporating demand response of electric vehicles in scheduling of isolated microgrids with renewables using a bi-level programming approach. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 116256–116266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotz, M.; Utschick, W. hynet: An optimal power flow framework for hybrid AC/DC power systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2019, 35, 1036–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, S. Controlled islanding for a hybrid AC/DC grid with VSC-HVDC using semi-supervised spectral clustering. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 10478–10490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadehbagheri, M.; Ildarabadi, R.; Javadian, A.M. Optimal power flow in the presence of HVDC lines along with optimal placement of FACTS in order to power system stability improvement in different conditions: Technical and economic approach. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 57745–57771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç; U; Ayan, K. Optimal power flow solution of two-terminal HVDC systems using genetic algorithm. Electrical Engineering 2014, 96, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, K.; Alsiraji, H.A.; El Shatshat, R. (2018, October). Optimal power flow in multi-terminal HVDC systems. In 2018 IEEE Electrical Power and Energy Conference (EPEC) (pp. 1–6). IEEE.

- Ayan, K.; Kılıç; U. Optimal power flow of two-terminal HVDC systems using backtracking search algorithm. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2016, 78, 326–335. [Google Scholar]

- Syllignakis, J.E.; Kanellos, F.D. A PSO optimal power flow (OPF) method for autonomous power systems interconnected with HVDC technology. Electric Power Components and Systems 2021, 49, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, D.; Chattopadhyay, D.; Luo, X. (2003, March). Stability constrained OPF: new results. In Proceedings of the 35th Southeastern Symposium on System Theory, 2003. (pp. 273–277). IEEE.

- Abhyankar, S.; Geng, G.; Anitescu, M.; Wang, X.; Dinavahi, V. Solution techniques for transient stability-constrained optimal power flow–Part I. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2017, 11, 3177–3185. [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla-Romero, J.U.; Pizano-Martínez, A.; Fuerte-Esquivel, et al. Two-stage transient-stability-constrained optimal power flow for preventive control of rotor angle stability and voltage sags. Journal of Modern Power Systems and Clean Energy 2024, 12, 1357–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J. , et al. A review of data-driven short-term voltage stability assessment of power systems: Concept, principle, and challenges. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2021, 2021, 5920244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wei, H.; Qi, J. , et al. Frequency stability constrained optimal power flow incorporating differential algebraic equations of governor dynamics. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2020, 36, 1666–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. , et al. Rule extraction based on extreme learning machine and an improved ant-miner algorithm for transient stability assessment. PloS one 2015, 10, e0130814. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Q.; Khan, H.U.; Khan, I.; Choi, B.J.; Wu, F.; Aly, A.A. An optimized algorithm for optimal power flow based on deep learning. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 2113–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. , et al. Multi-objective optimal reactive power dispatch of power systems by combining classification-based multi-objective evolutionary algorithm and integrated decision making. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 38198–38209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cao, J.; Xu, Y. , et al. Deep learning based on Transformer architecture for power system short-term voltage stability assessment with class imbalance. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 189, 113913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Dong, Z.Y.; Xu, Z. , et al. (2012, July). Power system transient stability-constrained optimal power flow: A comprehensive review. In 2012 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting (pp. 1–7). IEEE.

- Milano, F.; Canizares, C.A.; Invernizzi, M. Voltage stability constrained OPF market models considering N− 1 contingency criteria. Electric Power Systems Research 2005, 74, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. , et al. Resilience assessment and improvement for electric power transmission systems against typhoon disasters: a data-model hybrid driven approach. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 10923–10936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Püschel-Løvengreen, S.; Dozein, M.G.; Low, S.; Mancarella, P. Separation event-constrained optimal power flow to enhance resilience in low-inertia power systems. Electric Power Systems Research 2020, 189, 106678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, Z.A.; Patelli, E. (2021, May). A DC optimal power flow approach to quantify operational resilience in power grids. In International Probabilistic Workshop (pp. 55–65). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Li, Y.; Ma, W.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, Z.; Shahidehpour, M. Enhancing cyber-resilience in integrated energy system scheduling with demand response using deep reinforcement learning. Applied Energy 2025, 379, 124831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S. (2023). Research on optimal power flow solutions for transmission networks based on deep neural networks. (Master’s thesis). Guangxi University.

- Sun, B.; Song, M.; Li, A.; Zou, N.; Pan, P.; Lu, X.; Kong, X. Multi-objective solution of optimal power flow based on TD3 deep reinforcement learning algorithm. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 2023, 34, 101054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, Y. , et al. Wind power forecasting considering data privacy protection: A federated deep reinforcement learning approach. Applied Energy 2023, 329, 120291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S. , et al. (2024). Boosting communication efficiency in federated learning for multiagent-based multimicrogrid energy management. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems (Early Access). [CrossRef]

- Aishwarya, B.K.; Shekar, K.; Revathi, V.; Singh, J.; Singh, N.; Abdulaali, H.S. (2023, December). Federated Learning for Distributed Optimal Power Flow Solutions in Smart Grids. In 2023 International Conference on Power Energy, Environment & Intelligent Control (PEEIC) (pp. 1741–1745). IEEE.

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Toward a modern theory of adaptive networks: Expectation and prediction. Psychological Review 1981, 88, 135–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Tian, M.; Zhu, Z.; Dong, Z.; Gong, L.; Wang, X. Optimization method for distribution network flow based on robust reinforcement learning. High Voltage Technology 2023, 49, 2329–2339. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Lan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, H.; Sun, H. Analysis and decision framework for novel operational modes of power systems based on hybrid intelligence and its key technologies. China Electric Power 2023, 56, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Lv, Z.; Xue, L. Research on the application of multi-dimensional attention mechanism neural networks in power engineering data. Electronic Design Engineering 2024, 32, 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J.; Liu, X.; Cai, X.; Liu, Y.; Dai, J. New coordination optimization technology for source-grid-load-storage reactive power in distribution networks based on adaptive learning rate convolutional neural networks. Renewable Energy 2024, 42, 267–275. [Google Scholar]

- Lotfi, A.; Pirnia, M. Constraint-guided deep neural network for solving optimal power flow. Electric Power Systems Research 2022, 211, 108353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Peng, R.; Lu, C.; Wu, C. Computationally efficient data synthesis for AC-OPF: Integrating Physics-Informed Neural Network solvers and active learning. Applied Energy 2025, 378, 124714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, M.K. Spatial-temporal graph convolutional-based recurrent network for electric vehicle charging stations demand forecasting in energy market. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2024, 15, 3979–3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, G. , et al. Two-stage multi-objective OPF for AC/DC grids with VSC-HVDC: Incorporating decisions analysis into optimization process. Energy 2018, 147, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Yoon, Y.T.; Moon, S.I.; Park, J.K. (2013, July). VSC-HVDC model-based power system optimal power flow algorithm and analysis. In 2013 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (pp. 1–5). IEEE.

- Calle, I.A.; Ledesma, P.; Castronuovo, E.D. Advanced application of transient stability constrained-optimal power flow to a transmission system including an HVDC-LCC link. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2015, 9, 1765–1772. [Google Scholar]

- Mezhoud, N.; Leulmi, S.; Boukadoum, A. AC-DC Optimal Power Flow Incorporating Shunt FACTS Devices Using HVDC Model and Particle Swarm Optimization Method. International Review of Electrical Engineering (IREE) 2014, 9, 382–392. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y. Security-constrained multi-objective optimal power flow for a hybrid AC/VSC-MTDC system with lasso-based contingency filtering. IEEE Access 2019, 8, 6801–6811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Wu, X.; Ye, T. , et al. Output voltage response improvement and ripple reduction control for input-parallel output-parallel high-power DC supply. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 2023, 38, 11102–11112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Guoqing, L. Optimal power flow for AC/DC system based on cooperative multi-objective particle swarm optimization. Automation of Electric Power Systems 2019, 43, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Xia, D.; Gao, Z. , et al. Probabilistic load flow calculation of AC/DC hybrid system based on cumulant method. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2022, 139, 107998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, Z. , et al. A critical review of data-driven transient stability assessment of power systems: principles, prospects and challenges. Energies 2021, 14, 7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, C. A deep-learning intelligent system incorporating data augmentation for short-term voltage stability assessment of power systems. Applied Energy 2022, 308, 118347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomey, P.; Semenenko, S. (2017, June). Super-accelerated power systems power flow and state estimation calculations within the WAMS environment. In 2017 14th International Conference on Engineering of Modern Electric Systems (EMES) (pp. 55–58). IEEE.

- Arpanahi, M.K.; Alhelou, H.H.; Siano, P. A novel multiobjective OPP for power system small signal stability assessment considering WAMS uncertainties. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2019, 16, 3039–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. , et al. PMU measurements based short-term voltage stability assessment of power systems via deep transfer learning. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2023, 72, 2526111. [Google Scholar]

- Di Vito, V.; Mohammadian, M.; Baker, K.; Fioretto, F. (2024). Learning to optimize meets Neural-ODE: Real-time, stability-constrained AC OPF. arXiv, arXiv:2410.19157.

- Qu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Mugemanyi, et al. Dynamic exploitation Gaussian bare-bones bat algorithm for optimal reactive power dispatch to improve the safety and stability of power system. IET Renewable Power Generation 2022, 16, 1401–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Baker, K.; Dall'Anese, E.; Hu, Z.; Summers, T. (2018, June). Stochastic optimal power flow based on data-driven distributionally robust optimization. In 2018 Annual American Control Conference (ACC) (pp. 3840–3846). IEEE.

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, N.; Srivastava, L.; Malik, H.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A.; García Márquez, F.P. A robust optimization approach for optimal power flow solutions using Rao algorithms. Energies 2021, 14, 5449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).