1. Introduction

There is a broad consensus on the existence of a relationship between sleep and memory (for reviews, see [

1], [

2]. Numerous studies have shown that sleep supports memory trace consolidation more than wakefulness, a phenomenon known in literature as the ‘sleep effect’ [

3]. The sleep effect has been demonstrated for various types of information, including declarative and procedural memory (for reviews, [

1], [

4]. In studies on declarative memory, participants are typically asked to memorize stimuli, such as word lists or paired associates, before night sleep and to retrieve them the following morning [

5].

While there is extensive research on the impact of sleep on simple declarative memory tasks, its effect on the consolidation of more complex memory traces, such as narrative passages, has been relatively neglected. Prose memory is a type of long-term declarative memory referring to the ability to remember the content of text materials with different lengths or complexity. We often use prose memory in daily contexts, such as educational ones. The first studies on the topic are outdated and mainly focused on investigating the contribution of REM sleep to the consolidation of brief prose passages [

6], [

7]. Through selective REM-sleep deprivation paradigms, the authors showed that REM sleep is implicated in prose memory consolidation. However, the sleep effect for prose memory was not evaluated and no wake-control conditions were included. More recently, other studies on student populations focused on the impact of prolonged sleep loss on acquisition [

8] and retrieval [

9], but not consolidation, of prose materials. Furthermore, we have recently shown that pre-sleep learning of theatrical monologues improves subsequent sleep quality measures [

10]. While the changes in post-learning sleep parameters are generally ascribed to the involvement of those parameters in memory consolidation, these data represent only indirect proof of a sleep-related processing of this kind of memory.

To the best of our knowledge, only Bäuml and colleagues [

11] have specifically addressed the effect of sleep on prose memory consolidation. Using a between-subjects design, the authors found better recall of texts following a night of sleep than after a waking interval. However, the study did not account for potential differences in encoding between the sleep and wake conditions. Therefore, it cannot be ascertained whether the enhanced performance observed after sleep was due to differences between conditions at encoding rather than to a more effective consolidation process. Furthermore, the absence of baseline performance measures does not allow to evaluate the degree of memory deterioration over the retention intervals (for the importance of evaluating differences in encoding performance between sleep and wake conditions see [

4], [

12].

Here we aim to expand on this scarce literature on sleep and prose memory: in a within-subjects design, we compare memory performance for prose texts between a sleep and a wake condition. Of note, performance after the retention interval is expressed by changes of performance at re-test relative to immediate testing, in order to take into account possible performance differences occurring during the acquisition phase, as well as to evaluate the degree of memory deterioration occurring across the sleep and wake retention periods.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were selected from a sample of volunteer students recruited via online advertisements. Potential participants were previously asked to fill out a web-based set of questionnaires through the Google Form platform: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; [

13]), Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; [

14], Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI;[

14]) and ad hoc questions assessing general medical conditions and health habits.

The final study sample included ten university students (6F, 4M; mean age = 23.5 ± 4.53 years) reporting absence of any relevant somatic or psychiatric disorder, absence of clinically significant depression and anxiety symptoms (BDI-II score ≤ 29; BAI score ≤ 25), no history of drug or alcohol abuse, good sleep quality (PSQI < 5), having a regular sleep-wake pattern (e.g., individuals with irregular study or working habits such as shift-working were excluded), no use of psychoactive medication or alcohol at bedtime.

The study design was submitted to the Ethical Committee of the University of Florence, which approved the research (code 363/2024) and certified that the involvement of human participants was performed according to acceptable standards.

2.2. Procedure

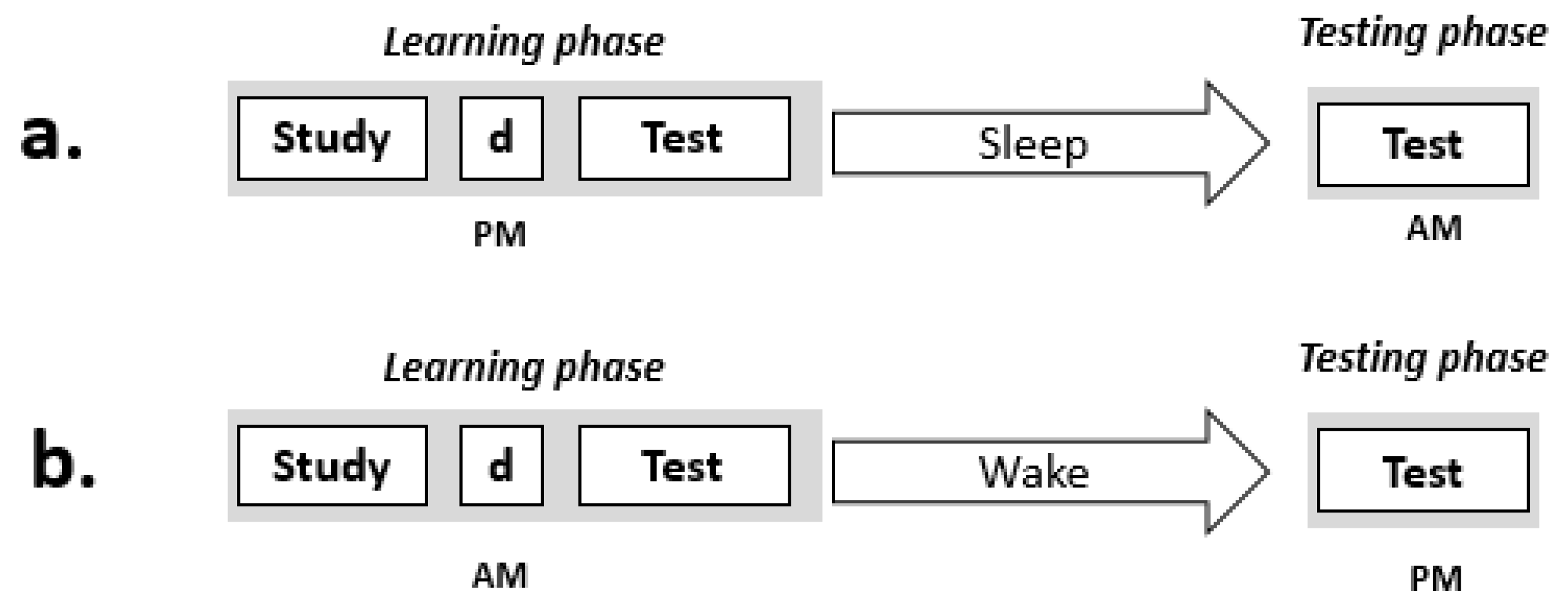

In a within-subject design, all participants underwent a Sleep (S) and a Wake (W) condition in which a learning phase was followed by a ≈9-hours retention interval spent, respectively, asleep or awake and then by a re-test. The order of conditions was balanced between participants. Conditions were conducted during working days, in separate weeks.

Figure 1 displays the study procedure.

The S condition was conducted at the participant’s home. The experimenter arrived there in the evening, about 40 mins before the participant’s habitual bedtime, and immediately administered the learning phase of the memory task. Then, the experimenter proceeded to setting up the Dreem Headband (DH) for sleep recording and the participant was instructed to go to sleep. The re-test phase of the memory task was performed in the morning, 30 minutes after awakening to allow for sleep inertia dissipation. On the night before S, each participant was administered a night of habituation to the DH.

In W, the learning phase was administered at the Sleep Lab in the morning. The re-test phase was performed in the afternoon, after a retention period corresponding to the participant's habitual sleep duration. During this interval, participants were requested to refrain from engaging in cognitively demanding activities.

In both conditions, at the beginning of the learning and of the re-test phase, participants reported their sleepiness level by filling out the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale [

15]. Moreover, at the end of the learning phase, participants were required to answer a set of questions addressing, on a 7-point scale, their level of interest for the text they just studied ('How interesting was the text you just read?'; response alternatives ranging from 1 = very interesting to 7 = very boring), the ease of reading (‘How easy was it to read?'; response alternatives ranging from 1 = very easy to 7 = very difficult), their previous knowledge of the text topic ('Did you have any previous knowledge about the topic of the text?'; response alternatives ranging from 1 = very poor to 7 = very high). Moreover, a final question was asked in order to ascertain that participants had not read the text before ('Had you ever read this text before?'; response alternatives: yes, no).

2.3. Prose Memory Task

The task consisted in studying one of two texts (text 1: ‘‘The Sun’’; text 2: ‘‘The Sea Otters’’, one for each condition), selected from the reading comprehension section of a test-preparation book for the Test of English as a Foreign Language test manual (TOEFL; [

16]) and already used in the study of Roediger & Karpicke [

17]. The texts were translated into Italian by two experts. The length of the texts was 247 and 308 words respectively. The two texts were assigned to the two conditions in balanced order between participants.

During the learning phase, participants were administered in written form one of the two texts and instructed to study it for 5 minutes. Then, subjects were asked to complete a 2-minute distractor task (i.e., an arithmetic task). Finally, a free recall test (“immediate test”, IT) was administered, in which participants had 10 minutes to write down on a blank piece of paper anything they remembered from the previously learned text. The same free recall test was performed as a re-test (“delayed test”, DT) after the retention interval spent in sleep or wakefulness.

2.4. Sleep Recordings

Sleep was monitored through a DREEM Headband (DH), a wireless device that records, stores, and analyses physiological data in real time. Physiological signals are recorded by means of three types of sensors: (1) brain cortical activity through 5 EEG electrodes yielding seven derivations (FpZ-O1, FpZ-O2, FpZ-F7, F8-F7, F7-O1, F8-O2, FpZ-F8; 250 Hz with a 0.4–35 Hz bandpass filter); (2) movements, position, and breathing frequency through a 3D accelerometer located over the head; (3) heart rate via a red-infrared pulse oximeter located in the frontal band. The DH is an alternative to the standard polysomnographic recording and has been considered an adequate device for high-quality large-scale longitudinal sleep studies in the home or laboratory settings [

18]. It also provides an accurate automatic sleep staging classification [

18] that follows the American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines (AASM; [

19]).

From the DH recordings we extracted the following classical sleep architecture variables: Sleep-Onset latency in minutes (SOL), Time in Bed (TIB; i.e. total amount of time, in minutes, from lights off to final awakening), Total Sleep Time (TST; i.e. total amount of time, in minutes, from the first appearance of N1 to final awakening), Actual Sleep Time (AST; i.e. total time spent in sleep states, expressed in minutes), sleep stage proportions over TST (N1%, N2%, N3%, REM%), Wake After Sleep Onset over TST, in minutes (WASO) and Sleep Efficiency (SE%; i.e. percentage of AST over TIB). Moreover, as in Conte et al., 2021, we computed an additional set of variables indexing:

sleep continuity: total frequency of awakenings per hour of AST;

sleep stability: arousals frequency per hour of AST (arousals are defined as all transitions to shallower NREM sleep stages and from REM sleep to N1); state transitions frequency per hour of TST (state transitions are defined as all transitions from one state to another); frequency of “Functional Uncertainty Periods” per hour of TST (“FU periods”; defined as periods in which a minimum of three state transitions follow one another with no longer than 1.5 min intervals; Salzarulo et al., 1997);

sleep organization: total time spent in sleep cycles over TST (TCT%), where sleep cycles are defined as sequences of NREM and REM sleep (each lasting at least 10 min) not interrupted by periods of wake longer than 2 min.

2.5. Data Analysis

Each text was divided into 30 units for scoring purposes [

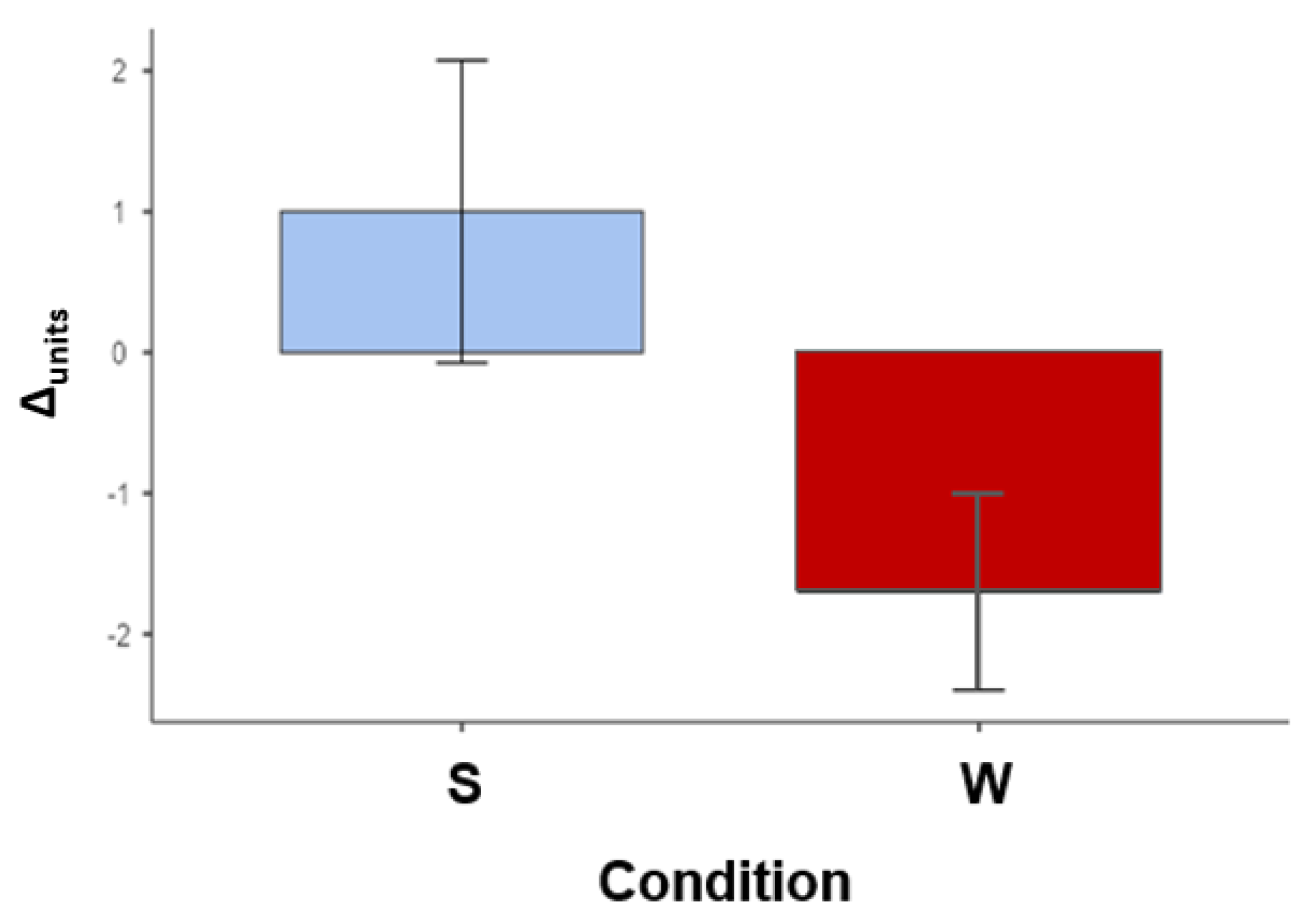

17]. The experimenter assigned one point for each correctly recalled unit (out of 30). Units containing synonyms or reversal of word order were also considered correct recalls. To quantify the degree of memory decay across the retention intervals, we computed the number of text units correctly recalled at IT minus the number of text units correctly recalled at DT (Δunits) as the main dependent variable.

Normality of distribution was checked through the Shapiro-Wilk test. To exclude differences in encoding efficacy between S and W, repeated measures ANOVA was performed with Condition (S and W) and Text (text 1 and text 2) as within factors and the number of text units correctly recalled at IT as dependent variable. To assess the sleep effect, we performed other repeated measures ANOVA with the same within factors and Δ units as dependent variable. Least significant difference (LSD) post hoc comparisons were performed when appropriate. A Pearson’s correlation analysis was also performed to investigate associations between sleep measures and memory performance.

In order to assess changes in sleepiness levels across conditions and study phases, we performed a repeated measures ANOVA with Condition (S and W) and Time (learning phase and re-test phase) as independent variables, and KSS values as dependent variable.

Finally, Student’s t test was employed to investigate differences in the level of interest, perceived difficulties and previous knowledge between prose passages.

Analyses were performed using SPSS (version 27); the significance level was set at p≤ .05.

3. Results

3.1. Memory Performance

The first rmANOVA yielded no significant main effect (Condition: F1,16= .797, p=.385, η2p =.047; Text: F1,16=.019, p= .890, η2p =.001) and no interaction Condition x Text (F1,16=.055, p=.817, η2p =.003), indicating that the number of recalled units at IT did not differ between conditions (S: 12.3±4.40; W: 14.2±4.59) or between texts.

As for the sleep effect, an effect of Condition emerged (F1,16= 4.571, p =.048, η2p =.222). Specifically, in S participants recalled more text units at DT than IT (Δunits: 1.00 ± 3.40), while in W they exhibited a memory trace decay over the retention interval (Δunits: -1.70 ± 2.21; t (16) = 2.14; p = .048, Cohen’s d =.956) (

Figure 2). No main effect of Text (F1,16=.759 p=.397, η2p =.045) and no interaction Condition x Text (F1,16 =1.182, p =.197, η2p =.102) emerged.

3.2. Sleep Features and Correlations with Memory Performance

Table 1 displays participants’ sleep measures. Correlation analyses revealed a significant positive correlation between the TCT% and Δunits, suggesting that the higher the proportion of time spent in sleep cycles in the sleep episode, the more participants benefited from sleep in text retrieval (r=.749, p=.032). No other significant correlation between sleep variables and memory performance emerged.

3.3. Sleepiness Levels

An effect of Condition emerged (F1,36= 22.756, p <.001, η2p =.387), with participants reporting higher KSS values in S (learning phase = 6.00 ± 2.40; re-test phase = 4.50 ± 2.22) than W (learning phase = 2.60 ± 1.07; re-test phase = 2.20 ± 1.55) (t (36) = 4.77; p <.001, Cohen’s d = 1.51). No main effect of Time (F1,36= 2.528 p =.121, η2p =.066) and no interaction Condition x Time (F1,16 = .847, p =.363, η2p =.023) emerged.

3.4. Final Questions about the Text

Table 2 displays participants' answers to the questions regarding the studied texts. Level of interest and ease of reading were rated as similar between texts, whereas participants reported having more prior knowledge about text 1 compared to text 2 (p=.004). None of the participants had read either text before.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to assess the effect of sleep on the consolidation of prose memory, a form of long-term declarative memory very frequently used in everyday contexts, especially in academic and educational settings. Despite its relevance in daily life, the relationship between sleep and prose memory has been surprisingly under-explored. Indeed, although many studies highlighted the positive effect of a retention period spent asleep on performance at simple declarative memory tasks, such as word-list learning, it is still unclear whether and to what extent sleep benefits consolidation of more complex declarative information, such as prose passages.

In this study, we deemed it relevant to include an immediate test in the learning phase for two key reasons. First, it allowed us to rule out the presence of between-condition differences in IT, ensuring that performance observed at DT reflects the consolidation processes occurring over the retention interval in S and W, rather than the effectiveness of encoding. Additionally, the immediate test served as a baseline measure enabling us to quantify the possible decline in memory trace during the retention period in both conditions.

The results of this study are consistent with previous findings showing positive effects of sleep on the consolidation of complex declarative memory materials [

6], [

7], [

11]. In fact, we observed that, in S, participants recalled more units of text at awakening than they did at IT. Conversely, in W, we found a worsening of performance over the retention interval. Therefore, our results suggest that, as far as prose memory is concerned, sleep not only protects memory traces against the decay occurring during periods of wakefulness but also reinforces them. Interestingly, this finding is at variance with data from most studies on word-lists learning (e.g., [

5], [

20]), in which the sleep effect is generally expressed as a lower decay of memory performance in sleep relative to wake conditions. These different results can be interpreted in an ecological perspective: in fact, as already suggested elsewhere (e.g., [

4], [

21]), the role of sleep in memory consolidation appears to be that of optimizing learning in a manner that is functional to future behavior. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that the sleep-dependent benefits observed on learning are more pronounced at tasks that mimic every-day life activities (such as increasing general knowledge through reading) rather than classical laboratory tasks which yield scarce resemblance to real-life memory processes. In other words, prose memory tasks would allow to highlight the “reconstructive” rather than “reproductive” nature of sleep-related memory processing [

4], by triggering, during subsequent sleep, the activation of higher order semantic processing than that engaged after word-lists learning (e.g., integration of new knowledge into existing networks, extraction of gist).

Furthermore, correlation analyses detected a significant positive association between the percentage of time spent in sleep cycles (TCT%) and Δunits. This finding implies that the more organized the sleep episode is, the more effectively it could counteract the natural decay of memory traces, thereby enhancing the ability to recall texts upon awakening. Sleep organization — defined by sleep variables linked to the number and duration of sleep cycles — is known to be crucial for biological and neurophysiological processes [

22], [

23], as well as for long-term memory consolidation [

24], [

25], [

26]. Indeed, participants in this study all displayed good sleep quality, as confirmed by polysomnographic recordings. Moreover, this finding is in line with data from our previous study on prose memory (Conte et al., 2022), in which we observed that, compared to a condition in which sleep was not preceded by learning, sleep after learning theatrical monologues showed higher continuity, stability and cyclic organization. Incidentally, we observed a similar pattern of results also with a complex multi-componential task [

27]: in this study, sleep cyclic organization was enhanced after pre-sleep training at the Ruzzle game compared to sleep following a gaming session which minimized learning demands. Although in the latter study the task fell in the implicit memory domain, its analogy to prose memory tasks resides in its complexity and resemblance to real-life learning processes. Taken together, these findings support the idea of a relationship between well-structured sleep and more efficient memory consolidation of complex ecological tasks.

The study results should be considered in the light of some limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, which could affect the generalizability of the findings. Secondly, participants reported differing levels of prior knowledge about the two texts used in the experimental conditions. However, we found no effect of the type of text on memory performance at IT. This evidence, together with the fact that the assignment of texts to the two conditions was balanced between participants, allows us to rule out an influence of the type of text on memory performance. Furthermore, we found higher levels of sleepiness in S than in W, both at IT and DT. This could be attributed to the natural increase in sleep propensity during evening hours and to possible lingering effects of sleep inertia after awakening [

28]. Still, the sleep effect we observed on prose memory cannot be explained by differences in vigilance levels, since KSS values remained stable across study phases in both conditions.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence supporting the role of sleep in the consolidation of prose memory, a complex and highly relevant form of declarative memory in daily life. Our findings suggest that sleep not only protects prose memory from decay but also actively enhances it. Future research should build on these results by using larger and different samples, including children, older adults, and individuals with cognitive impairments. Moreover, it would be valuable to investigate how sleep influences not just the quantitative retention of prose memory but also the qualitative reorganization of it through processes of transformation, integration in pre-existing knowledge networks and extraction of gist [

4].

5. Conclusions

Unlike studies relying on simple word lists, this research examined how sleep affects our ability to remember more complex declarative information, like prose passages. Our study found that a sleep period helps us to remember prose materials better than an equivalent interval spent awake. Our results confirm that sleep enhances memory retrieval of narrative text, highlighting the importance of sleep for everyday learning and specifically for knowledge acquisition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G., M.P.V, S.M., and G.F; methodology, F.G., F.C., S.M., and S.R.; formal analysis, S.M., O.D.R., and F.C.; investigation, S.M..; writing—original draft preparation, S.M. and F.C.; writing—review and editing, F.G., F.C., and G.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Carolina Brami for her precious help in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- S. Diekelmann e J. Born, «The memory function of sleep», Nat. Rev. Neurosci., vol. 11, fasc. 2, pp. 114–126, feb. 2010. [CrossRef]

- B. Rasch e J. Born, «About Sleep’s Role in Memory», Physiol. Rev., vol. 93, fasc. 2, pp. 681–766, apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- J. G. Jenkins e K. M. Dallenbach, «Obliviscence during Sleep and Waking», Am. J. Psychol., vol. 35, fasc. 4, p. 605, ott. 1924. [CrossRef]

- F. Conte e G. Ficca, «Caveats on psychological models of sleep and memory: A compass in an overgrown scenario», Sleep Med. Rev., vol. 17, fasc. 2, pp. 105–121, apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Gais et al., «Sleep transforms the cerebral trace of declarative memories», Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 104, fasc. 47, pp. 18778–18783, nov. 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. A. C. EMPSON e P. R. F. CLARKE, «Rapid Eye Movements and Remembering», Nature, vol. 227, fasc. 5255, pp. 287–288, lug. 1970. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Tilley e J. A. C. Empson, «REM sleep and memory consolidation», Biol. Psychol., vol. 6, fasc. 4, pp. 293–300, giu. 1978. [CrossRef]

- J. N. Cousins, K. F. Wong, e M. W. L. Chee, «Multi-Night Sleep Restriction Impairs Long-Term Retention of Factual Knowledge in Adolescents», J. Adolesc. Health, vol. 65, fasc. 4, pp. 549–557, ott. 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Lo, K. A. Bennion, e M. W. L. Chee, «Sleep restriction can attenuate prioritization benefits on declarative memory consolidation», J. Sleep Res., vol. 25, fasc. 6, pp. 664–672, dic. 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Conte et al., «Learning Monologues at Bedtime Improves Sleep Quality in Actors and Non-Actors», Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health, vol. 19, fasc. 1, p. 11, dic. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K.-H. T. Bäuml, C. Holterman, e M. Abel, «Sleep can reduce the testing effect: It enhances recall of restudied items but can leave recall of retrieved items unaffected.», J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn., vol. 40, fasc. 6, pp. 1568–1581, 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. Németh et al., «Optimizing the methodology of human sleep and memory research», Nat. Rev. Psychol., vol. 3, fasc. 2, pp. 123–137, 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Curcio et al., «Validity of the Italian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).», Neurol. Sci. Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol., vol. 34, fasc. 4, pp. 511–519, apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Sica e M. Ghisi, «The Italian versions of the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the Beck Depression Inventory-II: Psychometric properties and discriminant power.», in Leading-edge psychological tests and testing research., Hauppauge, NY, US: Nova Science Publishers, 2007, pp. 27–50.

- T. Akerstedt e M. Gillberg, «Subjective and objective sleepiness in the active individual.», Int. J. Neurosci., vol. 52, fasc. 1–2, pp. 29–37, mag. 1990. [CrossRef]

- B. Rogers, TOEFL CBT Success. Princeton: Peterson’s, 2001.

- H. L. Roediger e J. D. Karpicke, «Test-Enhanced Learning: Taking Memory Tests Improves Long-Term Retention», Psychol. Sci., vol. 17, fasc. 3, pp. 249–255, mar. 2006. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Arnal et al., «The Dreem Headband compared to polysomnography for electroencephalographic signal acquisition and sleep staging», Sleep, vol. 43, fasc. 11, p. zsaa097, nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Iber, Ancoli-Israel, Chesson, e Quan, The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2007.

- J. D. Payne et al., «The role of sleep in false memory formation», Neurobiol. Learn. Mem., vol. 92, fasc. 3, pp. 327–334, ott. 2009. [CrossRef]

- F. Conte, M. Cerasuolo, F. Giganti, e G. Ficca, «Sleep enhances strategic thinking at the expense of basic procedural skills consolidation», J. Sleep Res., vol. 29, fasc. 6, p. e13034, dic. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fagioli, C. Ricour, F. Salomon, e P. Salzarulo, «Weight changes and sleep organisation in infants», Early Hum. Dev., vol. 5, fasc. 4, pp. 395–399, set. 1981. [CrossRef]

- P. Salzarulo e I. Fagioli, «Sleep for development or development for waking?--some speculations from a human perspective.», Behav. Brain Res., vol. 69, fasc. 1–2, pp. 23–27, ago. 1995. [CrossRef]

- T. V. Bliss e G. L. Collingridge, «A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus.», Nature, vol. 361, fasc. 6407, pp. 31–39, gen. 1993. [CrossRef]

- G. Ficca, P. Lombardo, L. Rossi, e P. Salzarulo, «Morning recall of verbal material depends on prior sleep organization», 2000.

- G. Ficca e P. Salzarulo, «What in sleep is for memory.», Sleep Med., vol. 5, fasc. 3, pp. 225–230, mag. 2004. [CrossRef]

- M. Cerasuolo et al., «The effect of complex cognitive training on subsequent night sleep», J. Sleep Res., vol. 29, fasc. 6, p. e12929, dic. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. J. Hilditch e A. W. McHill, «Sleep inertia: current insights.», Nat. Sci. Sleep, vol. 11, pp. 155–165, 2019. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).