1. Introduction

Sleep represents an essential physiological reversible state and an important aspect that influences health condition and overall life quality. During sleep, consciousness is temporary suppressed while energy levels are restored and physiological processes occur.

In spite of the fact that sleep hygiene is a well-known subject by the majority of population, intriguingly, studies show that a high percent of people ignore healthcare professionals’ advice regarding sleep hygiene while appropriate knowledge sources are not available.

Young people tend not to value sleep importance, seeking for more time to get involved in other activities, even if wellbeing is influenced by sleep quality and quantity. Globally, numerous studies have been conducted on how sleep influences life quality, academic performance, focus and overall health. Young adults are the most prone to have a poor sleep hygiene. It has been concluded by researchers that adults need between 7 and 9 hours of sleep per night, 8 hours on average, preferably associated with a sleep routine.

The aim of this study is to analyze Romanian students’ status regarding sleep quality, length, duration and sleep hygiene, whether there is a sleep program during final examination sessions versus the rest of the year and if there are consequences of sleep deprivation among them.

1.1. About Sleep and Its Phases

Sleep can be defined as a recurrent, reversible state of perceptual detachment in regard with the environment. According to the Romanian National Mental Health Institute, sleep and alertness are behaviors that reflect variations in brain dynamics and optimize health and body physiology. The sleep and alertness alternance is regulated by homeostatic and circadian processes (1).

Sleep can be divided in 2 major phases: one characterized by rapid eye movement, REM and a less rapid sleep state – NREM which consists of 4 phases. Transition from alertness to sleep happens in the first stage of NREM while the actual sleep starts in the second NREM stage. The third and the fourth stages of sleep are characterized as slow wave sleep, followed by REM where wake or external stimuli response may occur. In humans, this cycle can be repeated up to 6 times, each having 80-110 minutes of duration. The interval between REM and NREM fluctuates during the night, and in the first half of the night the slow wave sleep prevails, while REM is more predominant in the second half, when dreaming occurs (2). In females, low length sleep is dominant, while in males it decreases with ageing (3). During REM, higher values of some neuro-transmitters were detected such as: glutamate, acetylcholine and dopamine, while in NREM gamma-aminobutyric acid and adenosine have higher levels. Neurotransmitters that inhibit sleep and stimulate alertness are: serotonin, histamine, norepinephrine and hypocretin (4). Sleep distribution can be multi-phasic or monophasic if occurs once in 24 hours (2).

1.2. Sleep Length and Sleep Quality

A healthy and restful sleep is adapted in regard with individual, environmental and social needs to ensure mental and physical wellness requirements. In order to measure sleep management, we took into consideration its quality by subjective evaluation, total sleep hours per night and easiness to fall asleep (1). Sleep represents a crucial health process, being involved in homeostasis of: immune system, endocrine system, cardiovascular system, metabolism and appetite. US National Foundation of Sleep recommends 7-9 hours of sleep per night for adults. Sleeping less than 7 hours or more than 9 hours per night were associated with higher risks of mortality and morbidity (5).

Sleep quality is a subjective measurement of its depth and rest. Sleep quantity on the other hand, refers to its duration. Reducing both its quality and duration has a negative impact on human body (6). A higher sleep quality has positive outcomes on brain by boosting toxin excretion or resting for a new day, while an inadequate sleep quality could make an individual more vulnerable physiologically, affecting cognition, emotions, stress management and more prone to altered emotional processing and negative emotions build-up (7). Sleep quality can be a depression predictive marker in young adults enrolled in university studies, research showing that a proper sleep hygiene is beneficial to students, reducing depressive moods (7). Poor sleep quality influences learning process and focus, some studies showing that a sleep quality is more important than sleep duration. In a study made at Michigan University, 85% of students reported an unsatisfactory sleep quality, this increasing anxiety cases, antisocial personality and attention issues (9). It has been shown that globally, adults, especially students suffer from psychological symptoms, linked with poor sleep quality (10).

Less than 6 hours of sleep is considered a risk factor for multiple pathologies that can lead to death (11). During the third sleep stage which mostly occurs before midnight growth hormone secretion is stimulated, playing a role in muscular and visceral development, especially in children, having anabolic effects: inducing lipolysis and gluconeogenesis (12). Lack of sleeps drives to increased levels of ghrelin, lowering leptin resistance, increased blood pressure, sympathetic system stimulation and accelerates insulin resistance process (5). More than 9 hours of sleep per night is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and premature mortality (11). Sleep length has a significant impact on life quality whether it is negative or positive (13). There are differences between males and females in regard with sleep quality and length as well as in circadian rhythm, sleep patterns during weekdays or weekends: females tend to sleep less during weekdays, more on weekends and get up earlier than males in general while males have later sleep hours during weekends (14).

1.3. Sleep Hygiene

In spite of the fact that there might be a better sleep quality in youth, in most of the cases thanks to the absence of disorders that can interfere sleep & a better natural sleep plasticity, lack of proper sleep hygiene awareness associated with busy lifestyles makes this age group experience a worse sleep quality (15).

Sleep hygiene presumes staying away from caffeine consumption during later times of the day, nicotine, not using technology before bed, stress management and physical exercises (16). During the wake state, adenosine accumulates, functioning as an inhibitory neurotransmitter (it’s produced throughout the day, giving a sensation of “urge to sleep” after 12-16 hours of wakefulness) (16). Effects of caffeine, an adenosine blocker, last between 5.5 & 7.5 hours, meaning that its consumption is recommended to be avoided during afternoon (16). According to a study conducted in Taiwan about 57% of people who drink three or more coffees per day have a shorter sleep length (5). Statistics say that men tend to consume more caffeine or other stimulants (16). Caffeine effects depend on its dosage and on a person’s sensibility (17). Alcohol, compared to caffeine, decreases the latency period and increases the duration of wave sleep in the first half of the night, causing sleep fragmentation in the second part of the night, posing a high risk of developing sleep apnea (16) Patients diagnosed with chronic alcohol consumption who suddenly cease alcohol consumption have a higher risk of sleeping disturbances (18). Nicotine, a well-known substance that acts as a cholinergic neuron simulator is associated with prolonged latency period, and REM & slow wave sleep suppression (18). Light coming from multiple sources represents another factor that negatively influences sleep. Melatonin is produced by the pineal gland, playing a role in regulating the circadian rhythm. For example, playing video games before bedtime, increases sleep latency by about 21 minutes, studies suggest. The same study suggested that 51% of teenagers aged between 16 and 29 years old that were using electronic devices before bedtime encountered difficulties falling asleep (16).

A good sleep also involves low levels of noise. Although background noises, such as traffic are usually not noticed, these still influence sleep (18). Improper sleep times, disrupt the circadian rhythm and the sleep/wake physiological state (18). Physical activity is well- known for its positive effects on sleep quality and duration, as well as for reducing psychologic stress (18).

Although sleep hygiene has an important role, most students are not familiar with these recommendations, causing reduced sleep length and quality, resulting in lower academic results. Sleep hygiene education might have positive effects on sleep (19).

1.4. Sleep and Immunity

Immune regulation takes place during sleep in which circadian factors and circadian-dependent processes contribute (2). Night sleep has a major role in innate immunity regulation, increasing the amount of natural killer cells. By releasing interferon gamma, T helper 1 lymphocytes improve immune response to bacterial and viral infections. A peak in interferon-gamma production was observed between 3:00 and 6:30 AM (20). Progressive sleep loss over several nights has an effect on cytokines, levels of IL-6 and CRP escalating after 4 nights of sleep deprivation, while greater TNF and vascular inflammatory markers increase after 1 or 2 nights of sleep restrictions (2). Nocturnal wake can be associated with increased or decreased cytokine levels involved in adaptive immunity, sleep deprivation reducing IL-2 and IL-12, involved in the response of T helper 1 lymphocytes which increase in viral infections. Lack of sleep can also reduce natural killer cells involved in innate immunity (20). Sleep also influences the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system, the first having an increased secretory activity during the night, especially towards morning (2). Release of GH and prolactin, during sleep stimulates proliferation and differentiation of T lymphocytes (20). While transitioning from wake to sleep, a transition from sympathetic to parasympathetic activity occurs with a reduced sympathetic activity during sleep, except REM when its activity is similar to daily sympathetic activity. In people suffering sleep disorders, sympathetic activity is increased during night, this adrenergic signaling favoring proinflammatory status (20).

Multiple studies suggest that sleeping less than 7 hours per night increases chances of dying from various causes with 12% compared to sleeping 7-8 hours per night. Sleep is also involved in physiological and pathological processes that we have discussed above. Risks have been shown as well in people who sleep more than 8 hours per night, therefore it is highly recommended to keep an appropriate number of slept hours per night (21).

1.5. Sleep and Memory

Sleep has an essential role in the process of memory consolidation, during which the synaptic connections that were active during waking periods are strengthened and synapses are formed between dendrites and axons storing information (22,23). Encoding, consolidation and retrieval represent stages of memory, consolidation and retrieval being influenced by sleep, the retrieval stage protecting encoded memories (24). Prospective memory represents the ability to initiate and implement previously planned goals. Studies revealed that short sleep duration or sleep deprivation negatively affect prospective memory (25).

New studies shows that the learning process is positively influenced if sleeping immediately rather, than sleeping after a longer period of time (26). Active neurons in the waking state are reactivated during sleep, in this case modulating the synaptic connections, having an essential role in the long-term memory formation (27). Intense synaptic activity has been observed in neural processes associated with learning, sensory processing, and motor functions, these being disturbed by long periods of wakefulness or even lack of sleep (28). Quality sleep (7-8 hours of sleep per night) means better academic performance. In many cases, sleep deprivation can affect concentration, memory or attention (29). Lack of sleep has been associated with sleepiness, fatigue, poor attention and impaired cognitive performance. Based on one study, an individual who has been awake for 17 hours has the cognitive performance equivalent to that a person with 0,05% alcohol concentration in their blood (30,22).

1.6. Effects of Sleep Deprivation

Sleep deprivation has several effects on: health, academic and professional performance. This might as well increase susceptibility to various infections, anxiety, depression, risk of accidents, substance abuse, cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (31). Sleep deprivation can also affect thermoregulation (32). Studies show that reducing sleep by 1 hour per night decreases cognitive abilities at the same level to a night of total sleep deprivation, mild restriction accumulating over time (31). Limitation of sleep can decrease attention, immune response, lowers pain threshold and increases reaction time (4). Extreme sleepiness represents a state that varies during day, from slight impairment of alertness to inability to be alert or cautious when performing daily chores (32).

Frequently, sleep duration is directly proportional to life quality, a reduced duration and quality can increase the risk of suicide, anxiety, depression in which smoking and alcohol consumption are also added (33). Prefrontal cortex is involved in emotion regulation and it is sensitive to sleep loss which might decrease the ability to control emotions, face emotional challenges, increase sensitivity to unpleasant emotional events. Investigations made on sleep deprived individuals discovered that areas associated with emotional processing and the executive control (prefrontal cortex, thalamus, parietal regions) have a significantly decreased activity (34). Irregular sleep schedules, especially in the case of students, have been associated with depressive symptoms, such as irritability, fatigue, loss of interest and decreased self-esteem (9). US studies suggest that that 42% of young people suffer from insomnia and 19% experienced sleepiness during the day (35). Among students sleep deprivation is often associated with focus disorders, reduced comprehension and memorization (36). Sleeping disorders are a frequent reported factor in triggering migraines among women and are linked to their frequency and intensity (37).

Body weight is always influenced by sleep quantity, altering the levels of the appetite-inhibiting leptin and the appetite-stimulating ghrelin, metabolically relevant hormones, resulting in appetite changes and glucose homeostasis alteration (38). Seeping less than 7 hours changes the circulating levels of leptin and ghrelin, increasing appetite, lowering catabolic processes and increasing the risk of diabetes and hypertension (39).

1.7. Purpose of Our Study

Sleep hygiene includes a set of recommendations for a quality sleep. The majority of individuals have access to information regarding the importance of sleep, it is not used accordingly, resulting in improper study or working conditions. Students have a busy schedule and are exposed to high psychosocial stress levels, being more prone to feel the consequences of insufficient sleep. Our study purpose is to analyze the factors that usually interfere with the quality and duration of sleep, whether it is in a positive or negative way and the effects of sleep deprivation that can be particularly observed among students.

2. Results

2.1. Statistical Analysis of Demographic Data

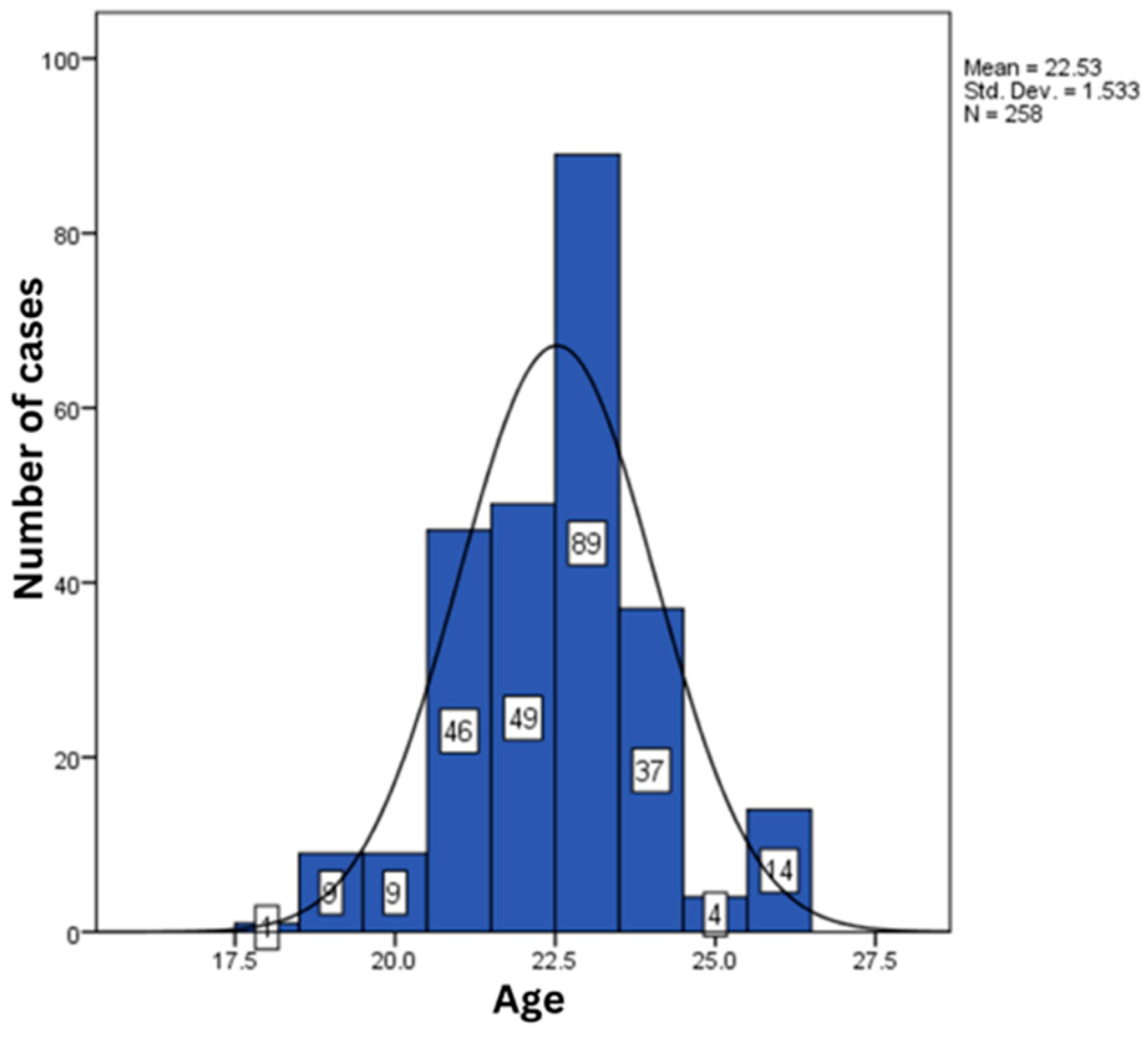

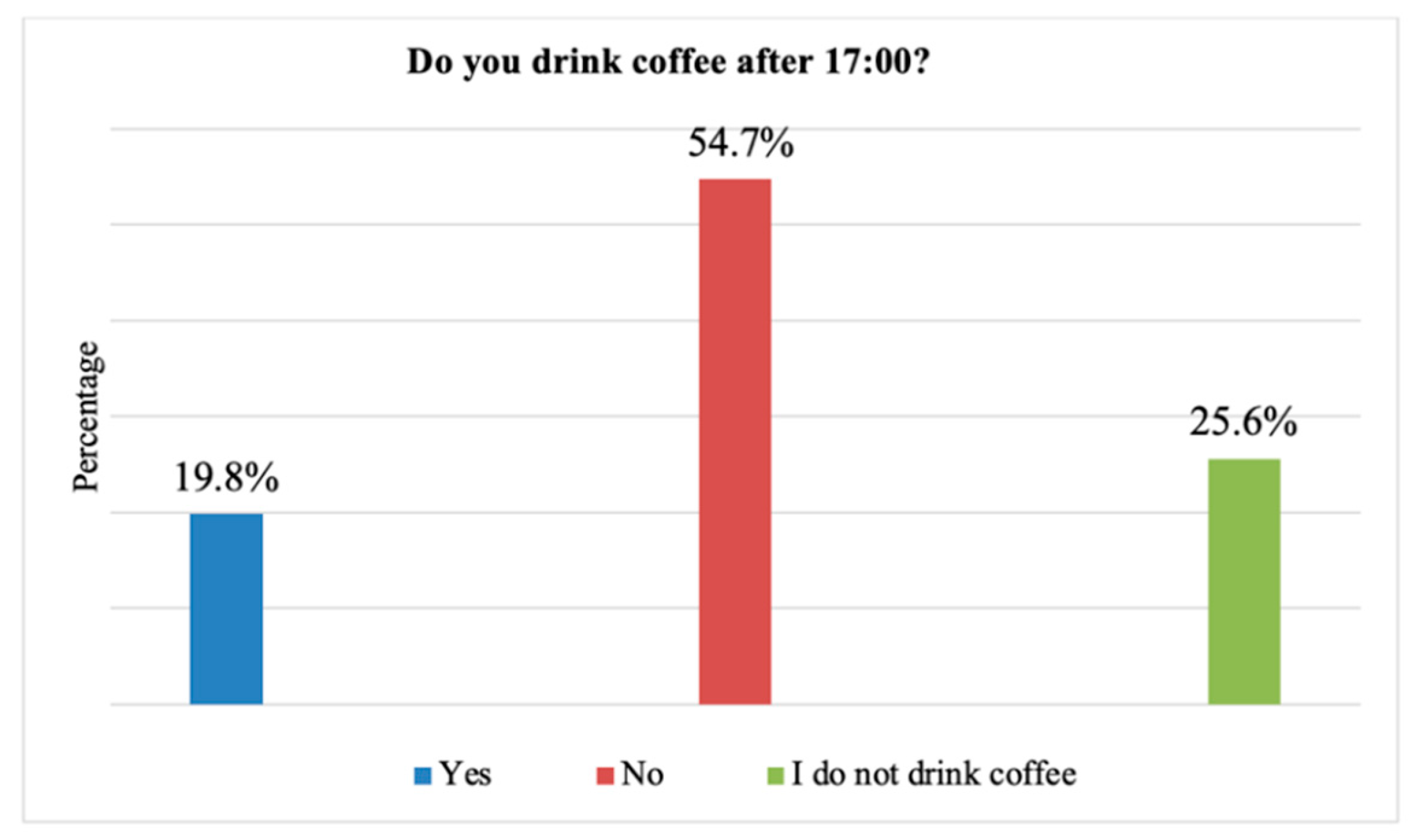

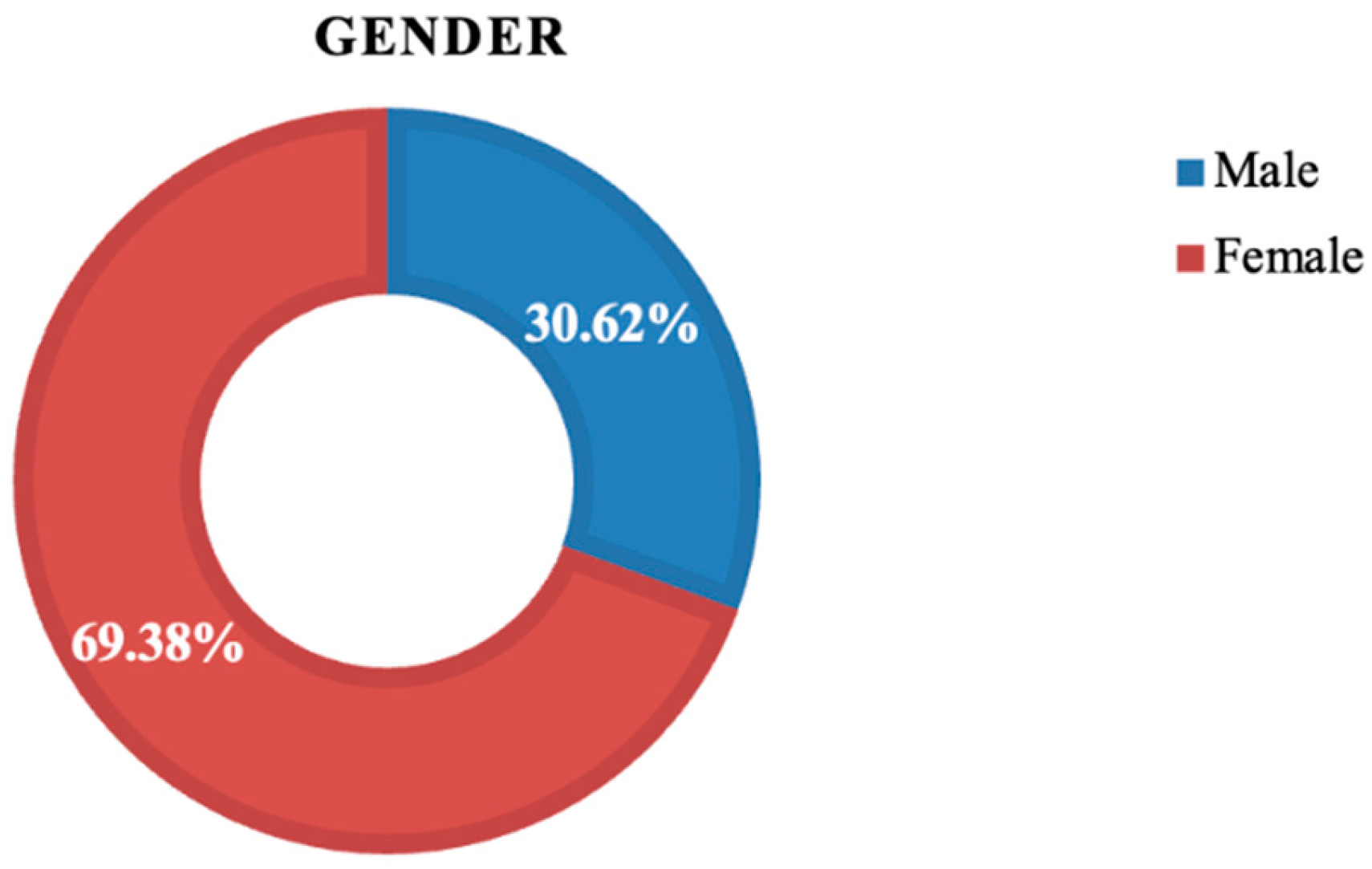

Age and gender of the 258 subjects included in this study represented 2 of the demographic parameters included in the statistical analysis. The percentage of female subjects was 69.38% (179 cases), and 30.62% of the cases were male (79 cases) (statistical P: 0.047) (

Figure 1).

The minimum and maximum age was between 18 to 26 years of age, the average value of this parameter being 22.53; 24 ± 1.53 years (

Table 1,

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Age variation within the statistical analyzed lot.

Figure 2.

Age variation within the statistical analyzed lot.

Table 1.

Statistical analysis of subjects age included in the study.

Table 1.

Statistical analysis of subjects age included in the study.

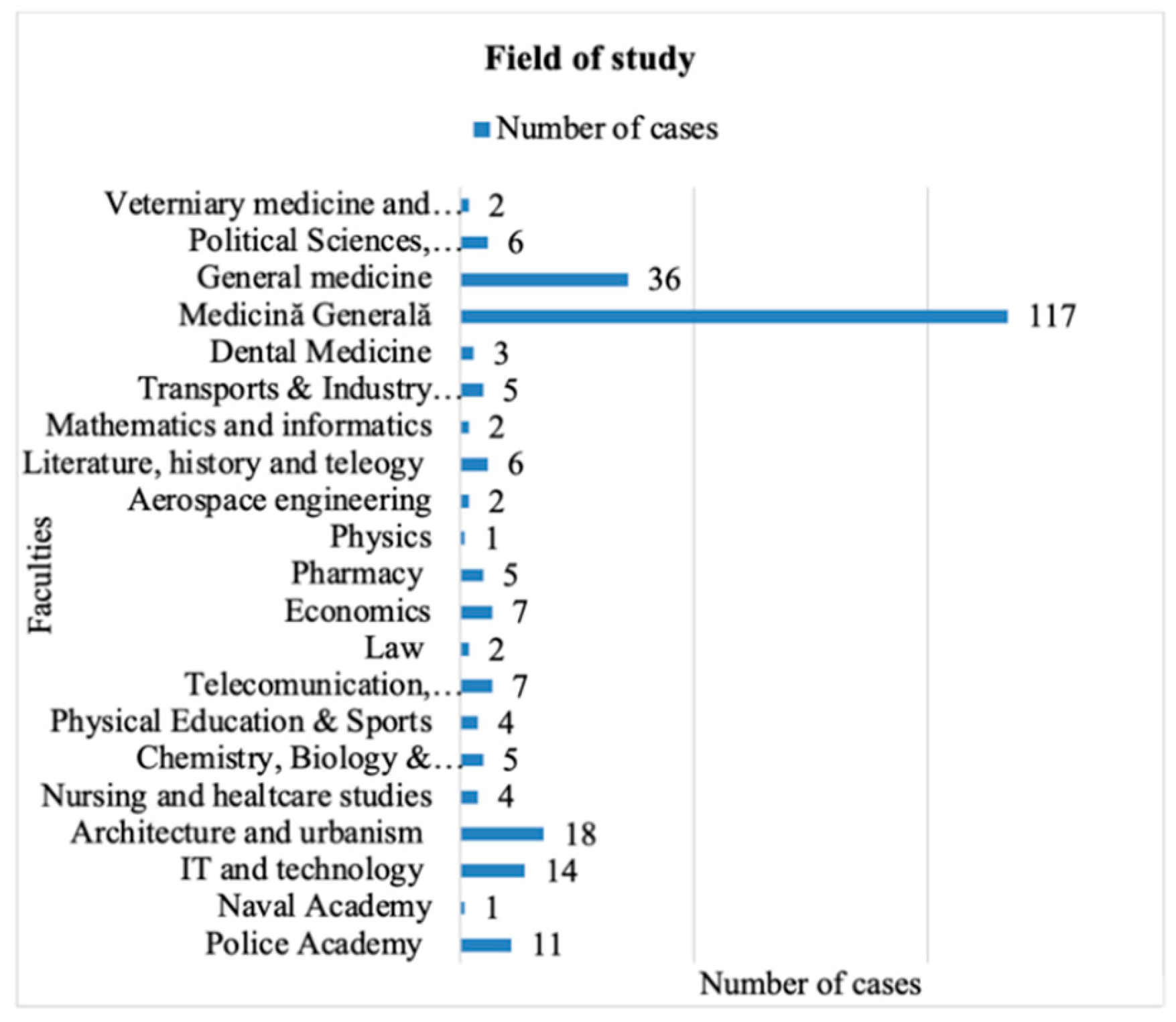

2.2. Statistical Analysis of Education Level (Followed Studies)

The majority of the subjects from our lot were enrolled in medical university (117 cases, 45.3%), followed by subjects enrolled in Sociology and Psychology university (36 cases, 13.9%) (statistical P: 0.078) (

Figure 3).

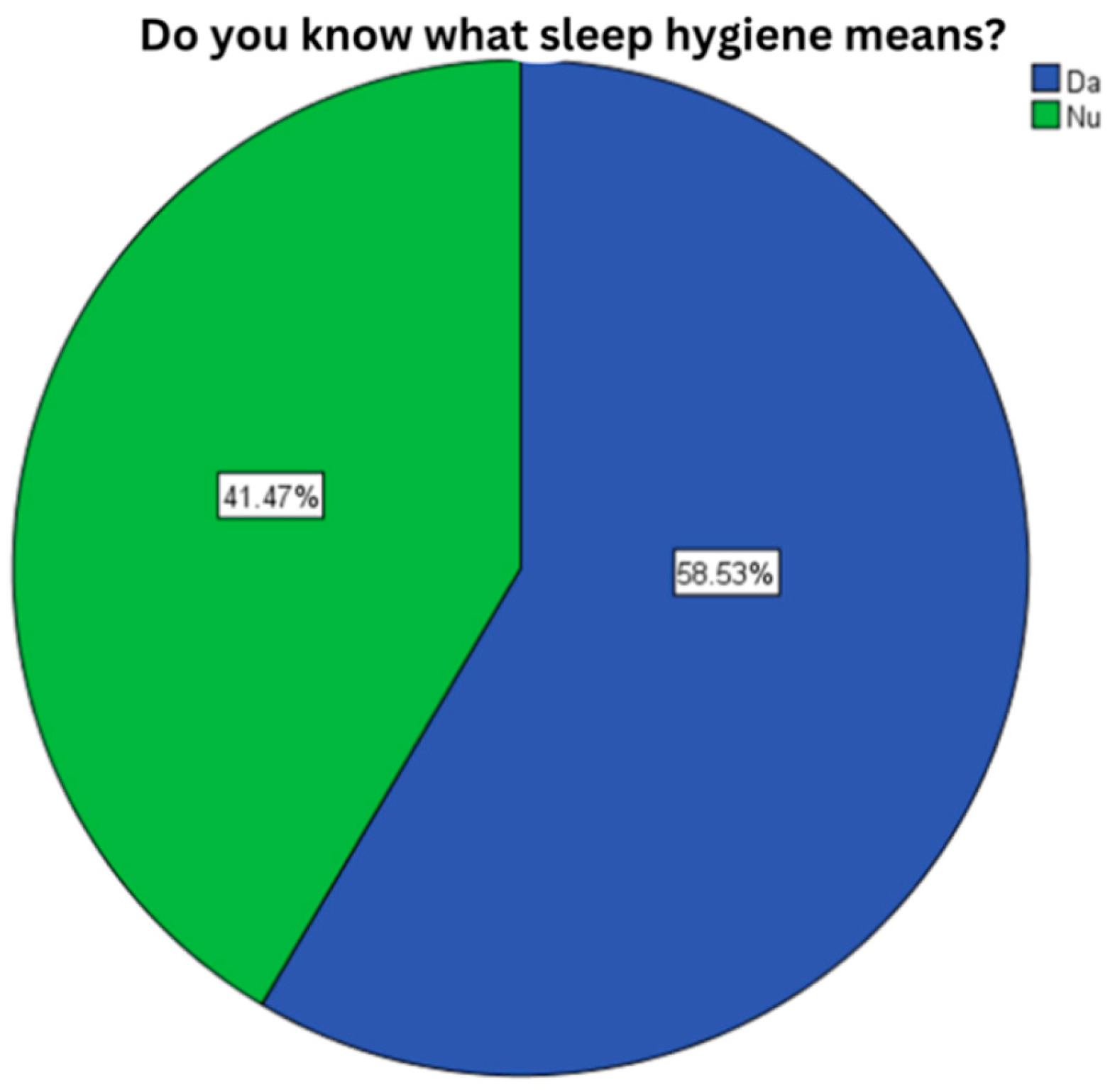

2.3. Level of Knowledge about Sleep Hygiene

58.5% of the subjects (151 cases) stated that were aware of this subject, while 41.47% were not aware of this subject (statistical P: 0.048) (

Figure 4).

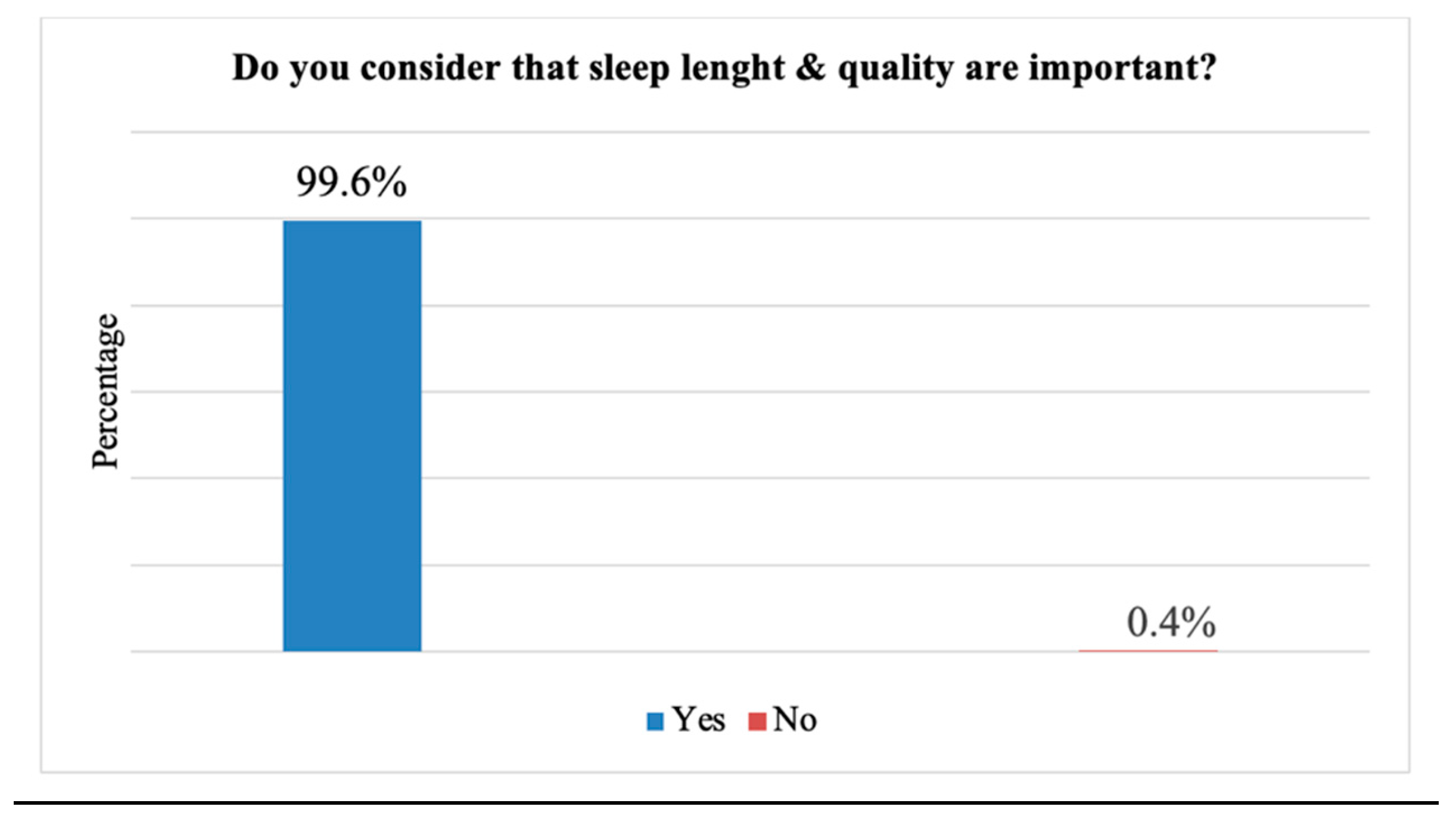

2.4. The Importance of Sleep Quality and Sleep Duration

99,6%. of the subjects enrolled in the study were aware of how important sleep length and quality are (257 cases) (statistical P: 0.039) (

Figure 5).

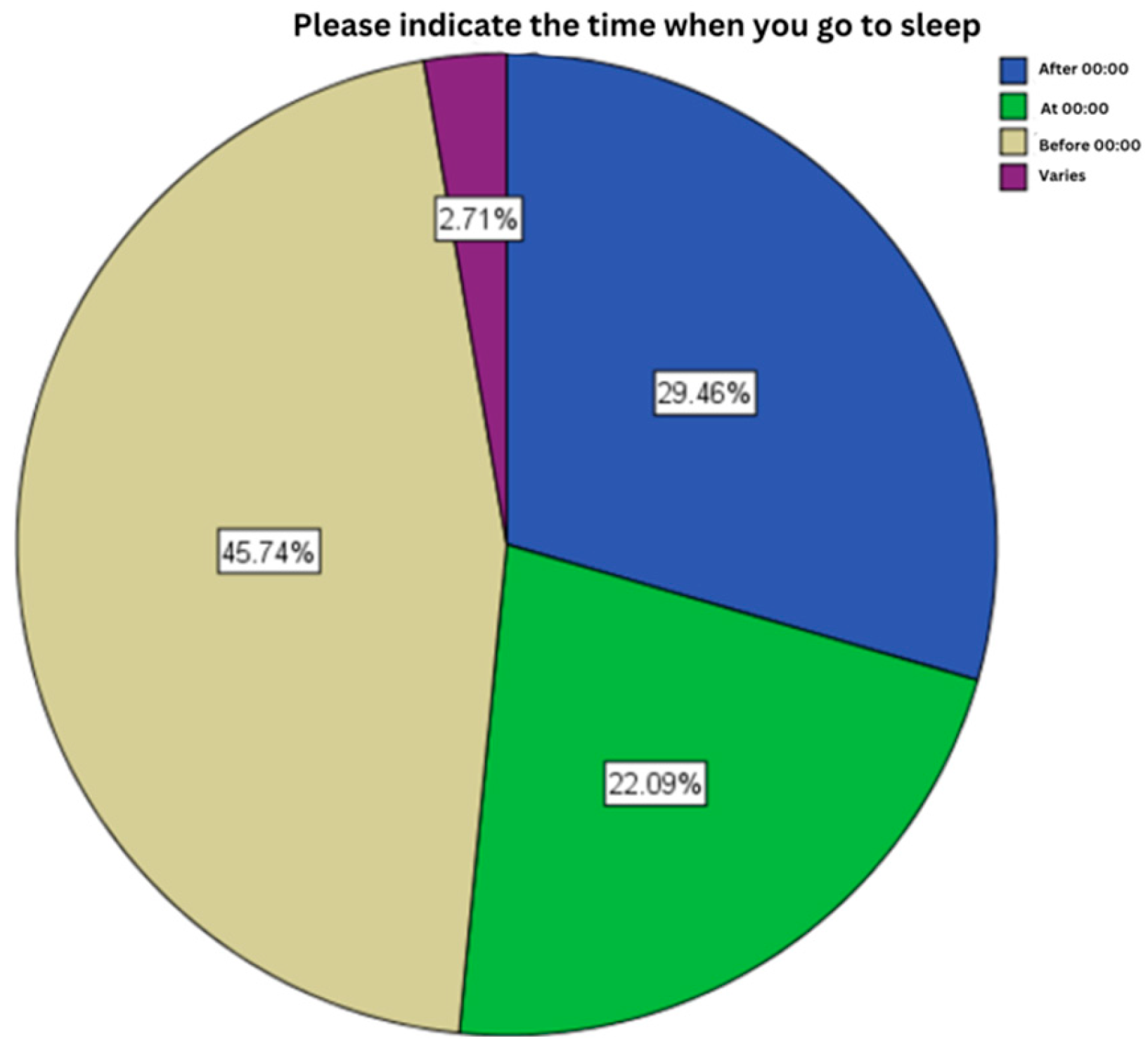

2.5. Sleep Hours

In this section, the statistical analysis highlighted that most of the subjects fall asleep before midnight (118 cases, 45.7%), category followed by subjects who fall asleep after midnight (76 cases, 29.5%) (statistical P: 0.562) (

Figure 6).

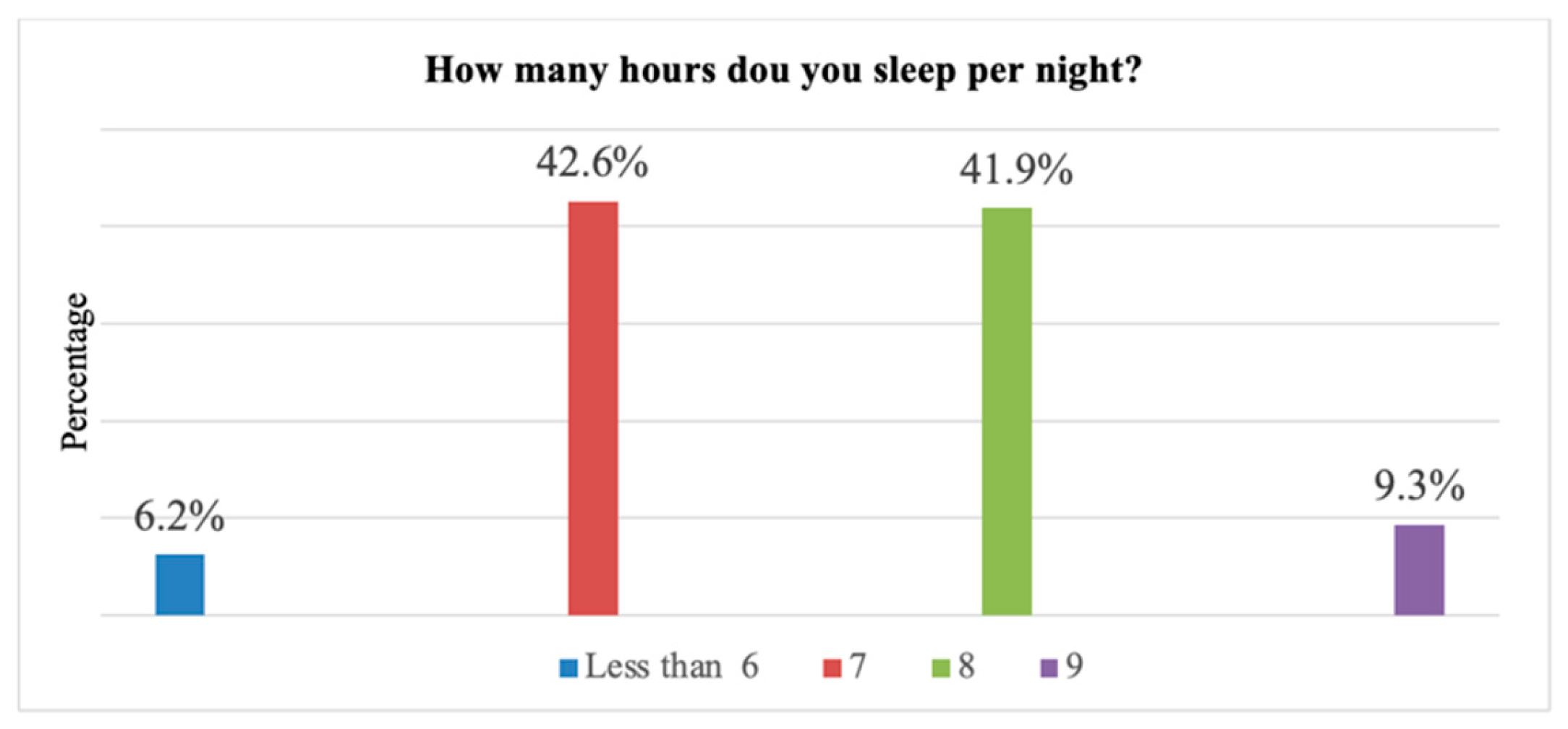

2.6. Number of Sleep Hours

The statistical analysis highlighted that most of the subjects sleep 7 hours per night (110 cases, 42.6%), followed by cases that sleep 8 hours per night (108 cases, 41.9%) (statistical P: 0.022) (

Figure 7).

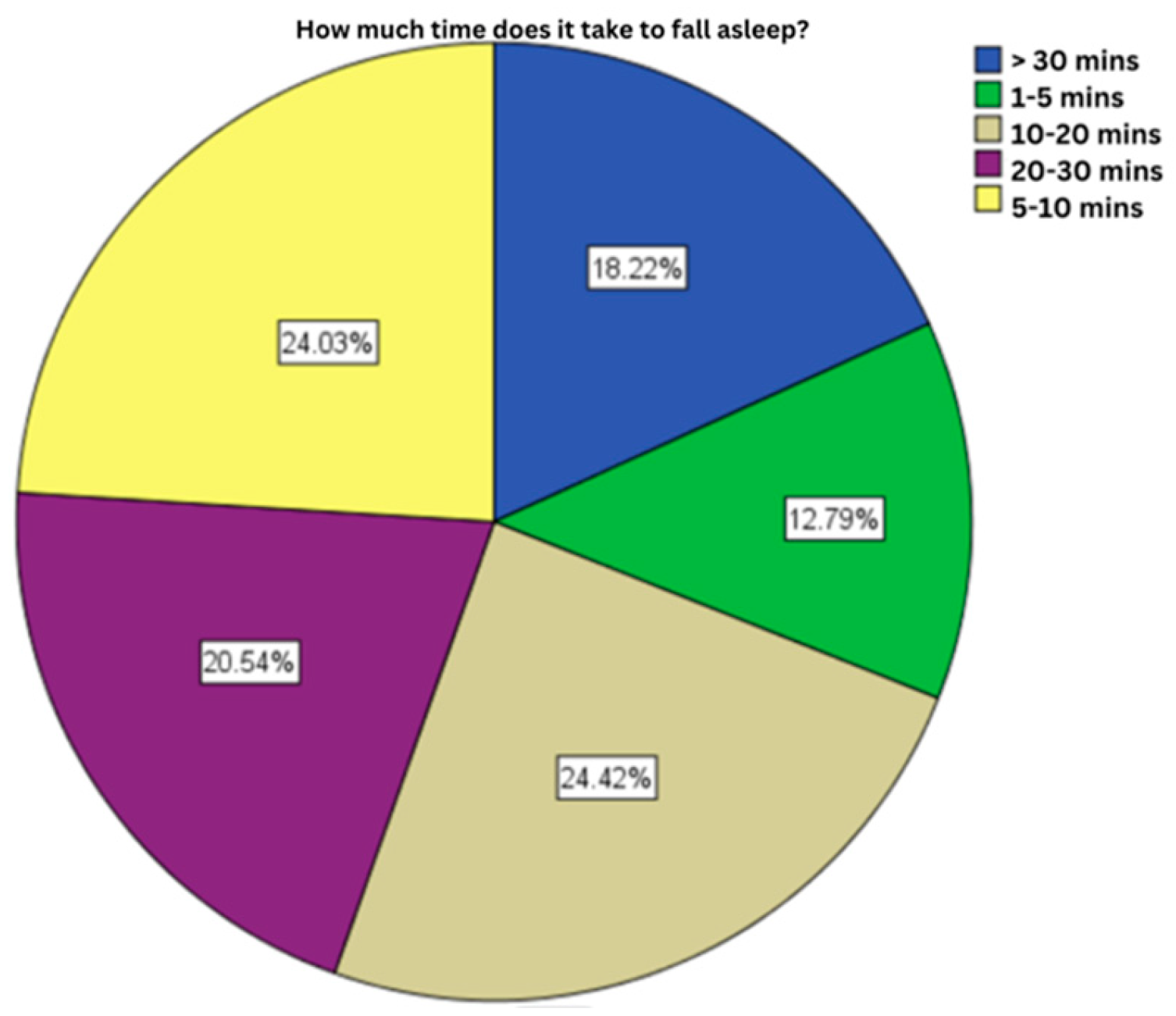

2.7. Time Interval Until Falling Asleep

Most of the subjects enrolled in the presented study declared a time interval of falling asleep between 10 or 20 minutes (63 cases, 24.42%), followed by those with a time interval of 5-10 minutes (62 cases, 24.03%) (statistical P: 0.44) (

Figure 8).

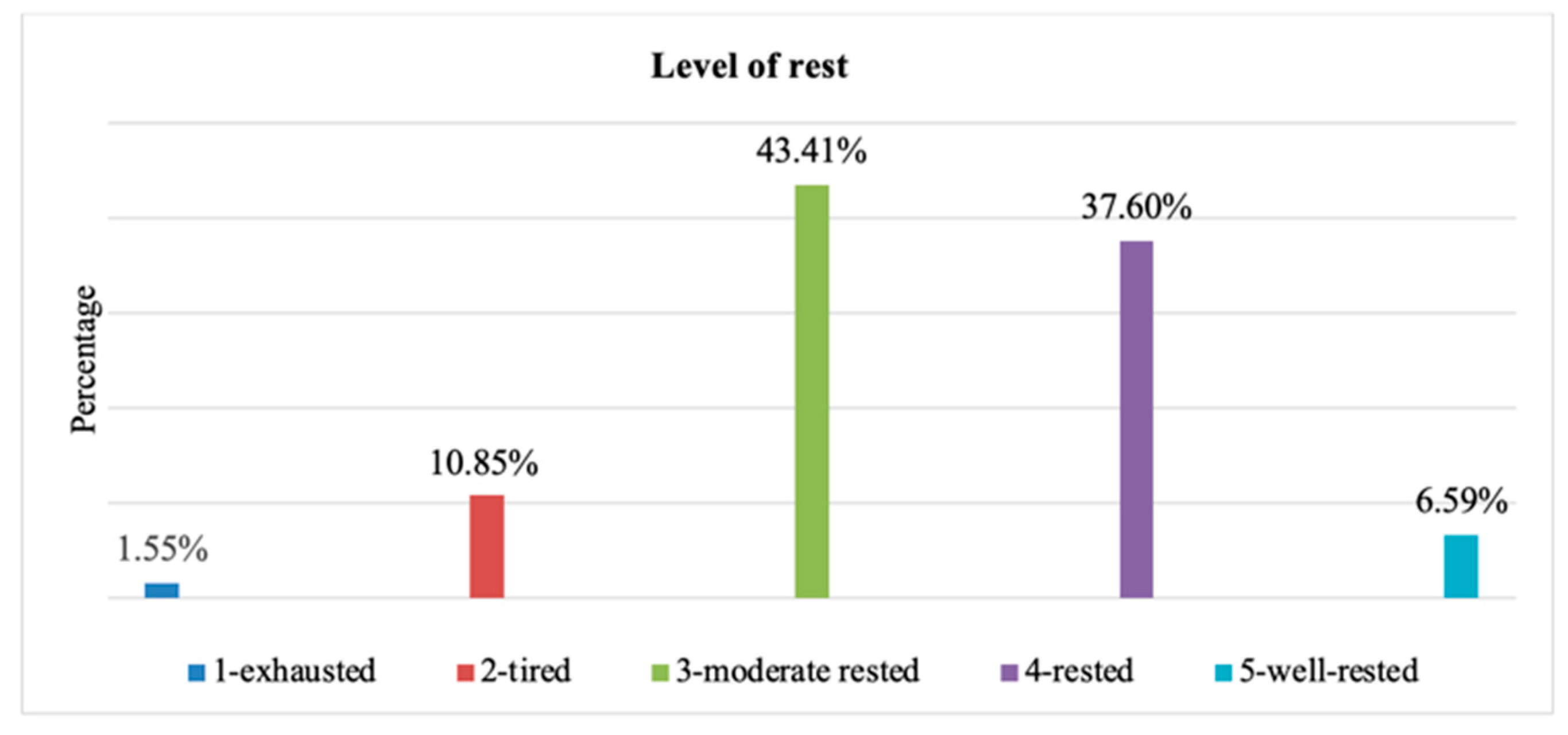

2.8. Evaluating the Rest Level on a Scale from 1 to 5

For this question most subjects gave an intermediate answer, giving predominantly 3 points (112 cases, 43.4%), 1 point meaning exhausted and 5 points well-rested (statistical P: 0.008) (

Figure 9).

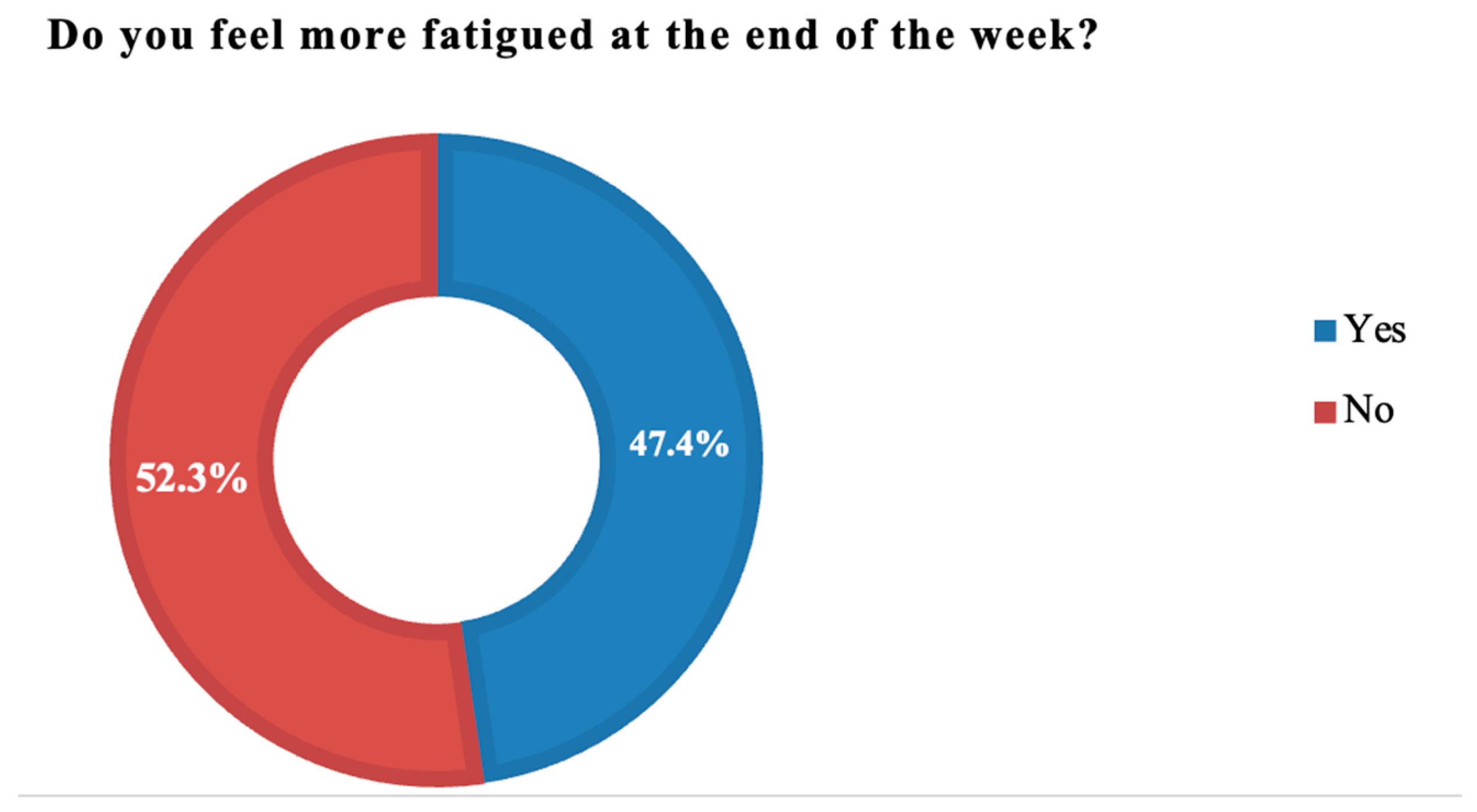

2.9. Fatigue Level at the End of the Week Compared to the Beginning of the Week

Most of the cases answered affirmative (47.7%, 123 cases) (statistical P: 0.057) (

Figure 10).

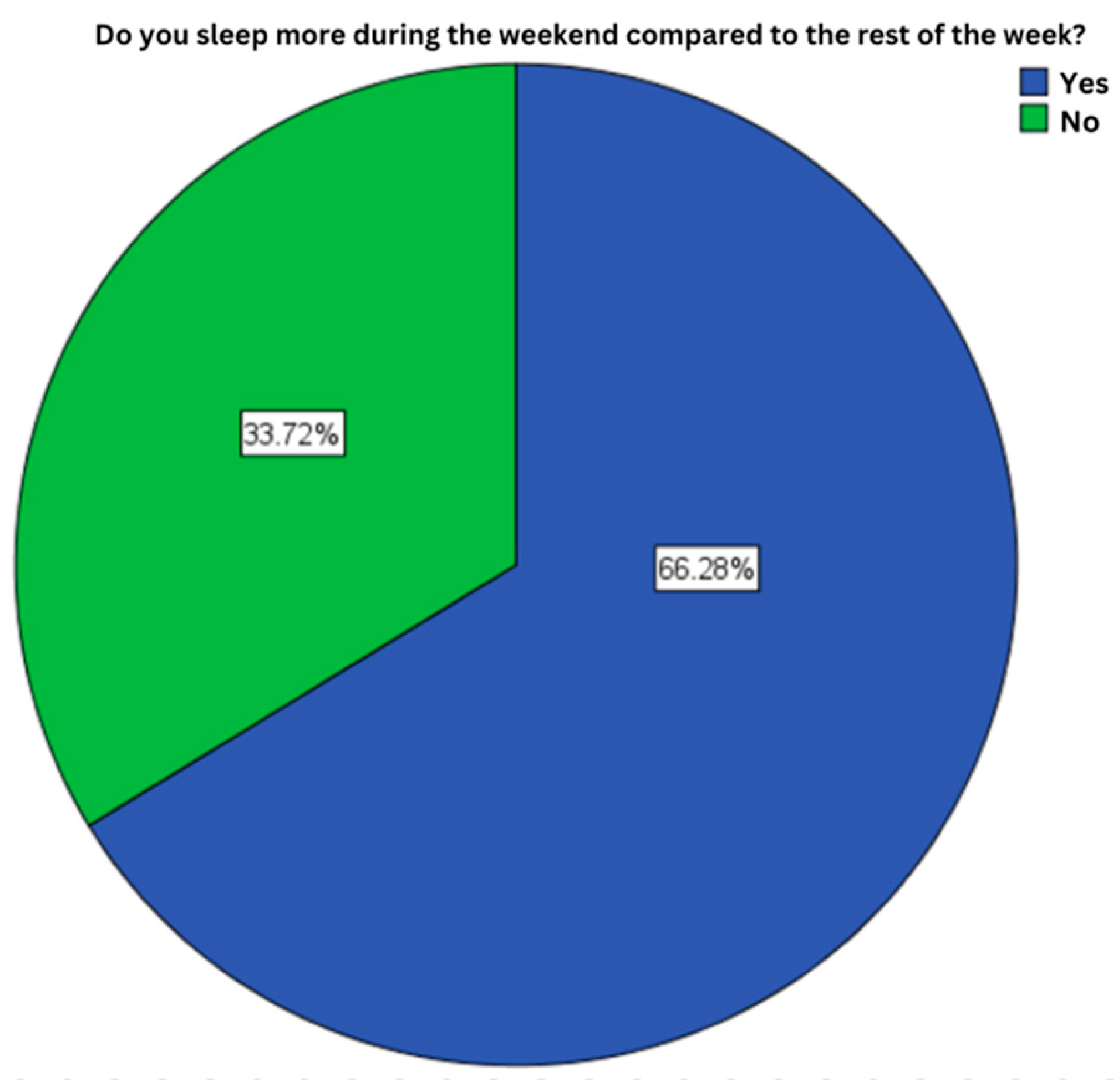

2.10. Sleep Variation Duration During the Week

66.3% of the subjects enrolled in the study stated sleeping more during the weekend compared to the rest of the week (171 cases, 66.3%) (statistical P: 0.044) (

Figure 11).

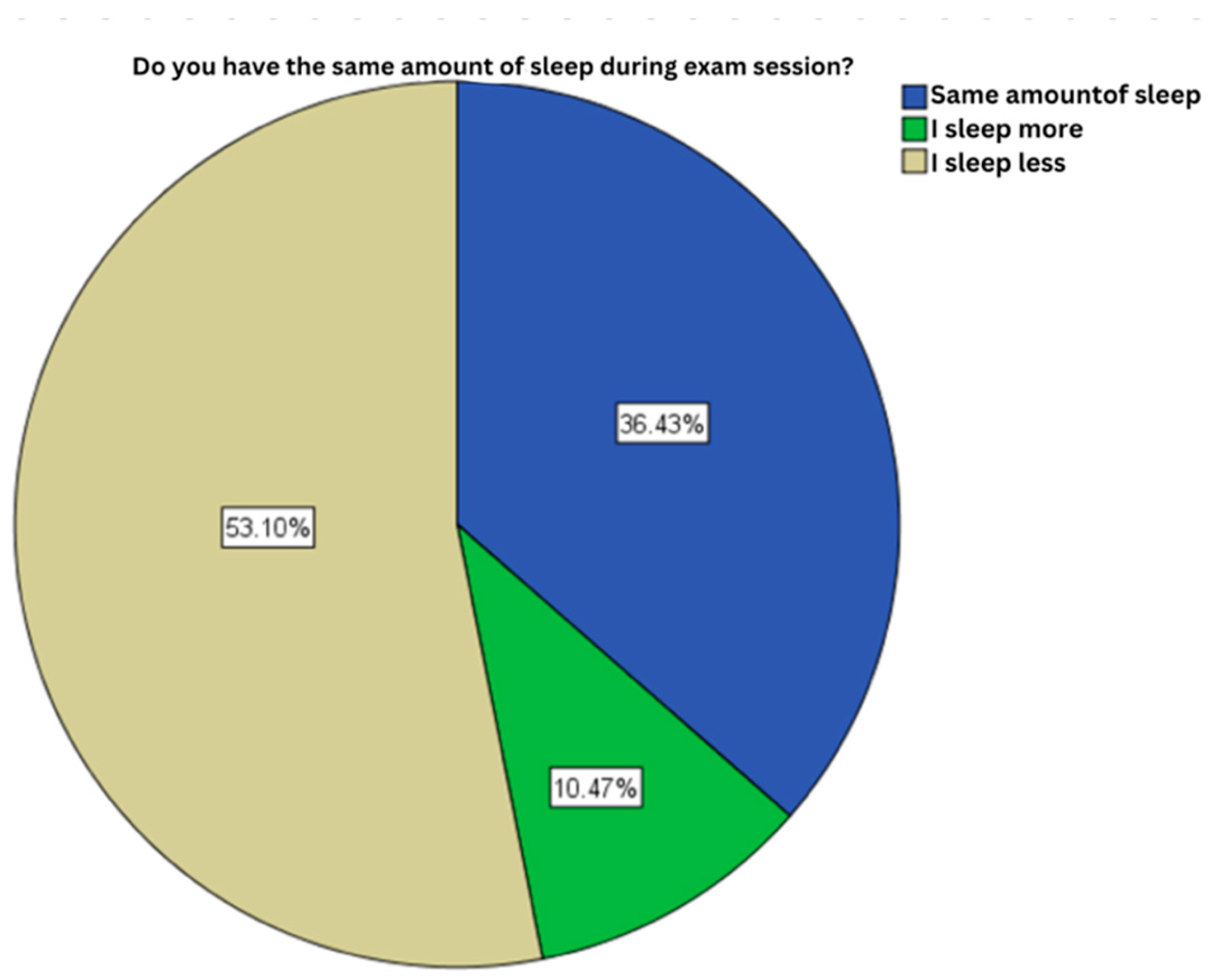

2.11. Sleep Length During Exams Session

For this item, approximately 50% of subjects stated sleeping less during exams session compared to the rest of the academic year (137 cases, 53.1%) (statistical P: 0.088) (

Figure 12).

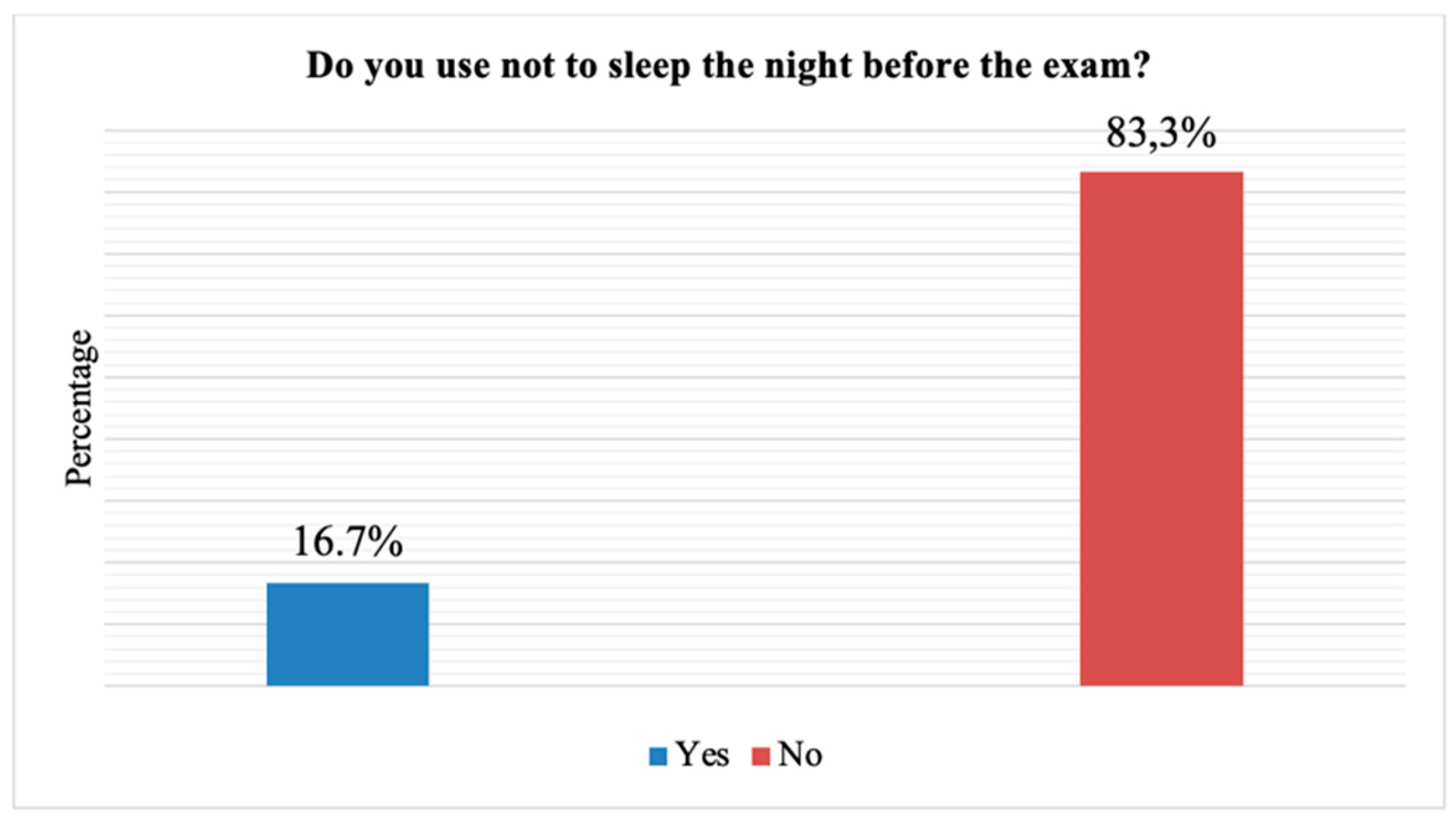

2.12. Sleeping Before Exams

A small percentage of subjects, 16.7% stated that they do not sleep before an exam (43 cases) (statistical P: 0.044) (

Figure 13).

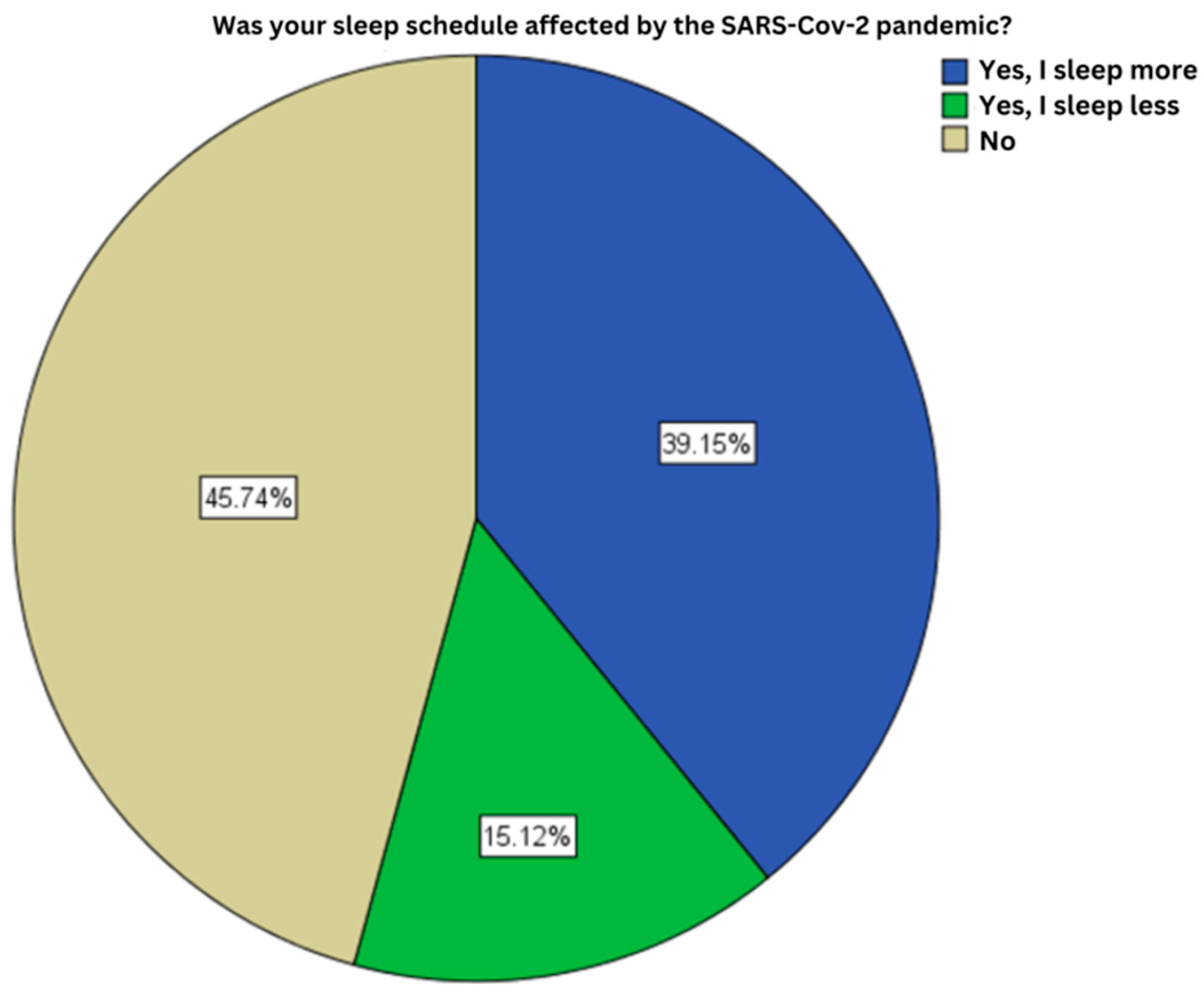

2.13. Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sleep

45.7% of the subjects had no changes in the duration of their sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic (118 cases), followed the cases that declared sleeping more since the pandemic (101 cases, 39.1%) (statistical P: 0.023) (

Figure 14).

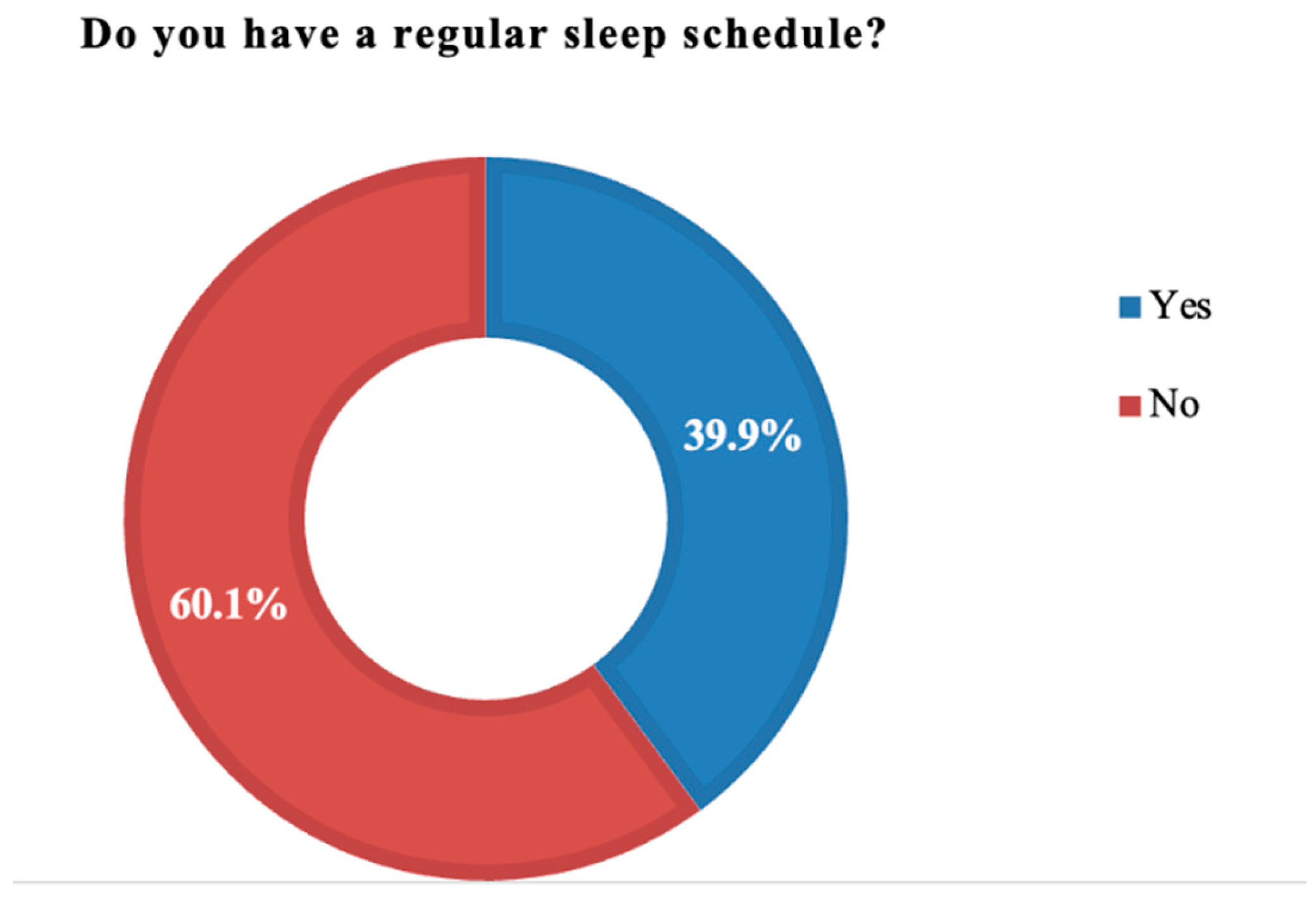

2.14. Implementing a Sleep Schedule

0.1% of the study participants gave a negative answer (155 cases) (statistical P: 0.003) (

Figure 15).

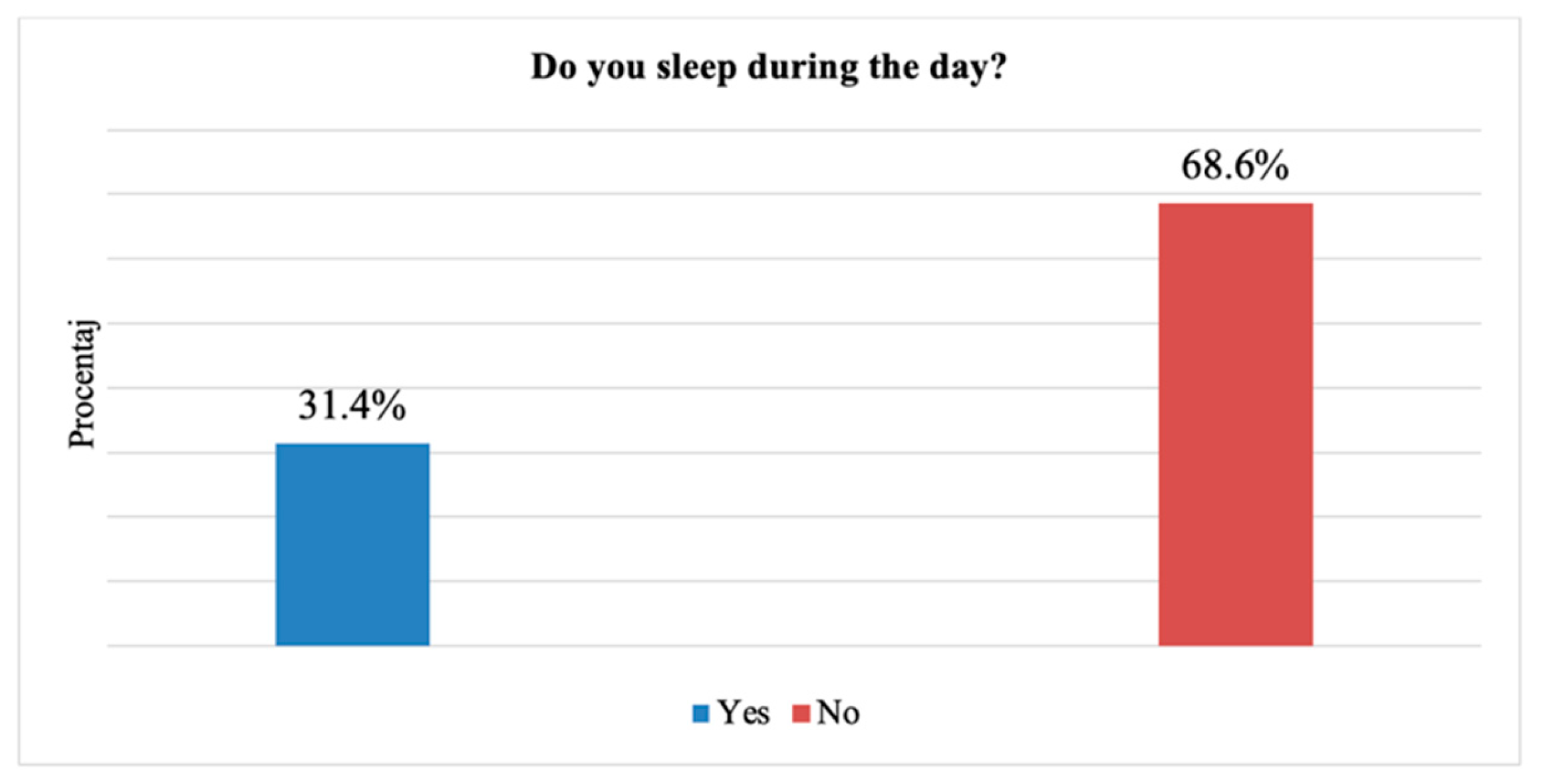

2.15. Sleeping During the Day

31.4% of subjects admitted sleeping during the day (81 cases) (statistical P: 0.055) (

Figure 16).

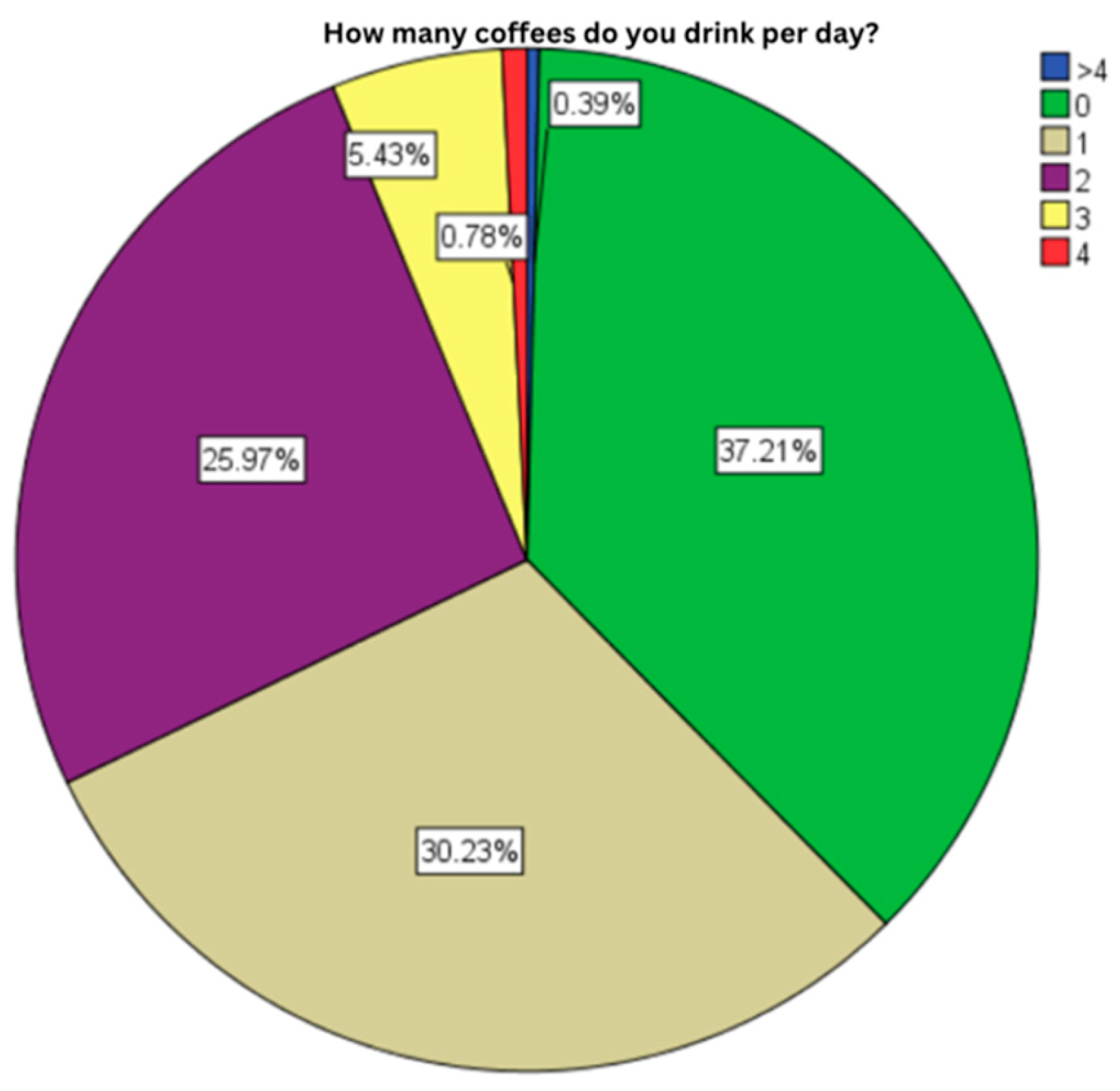

2.16. Daily Coffee Consumption

37.2% of the subjects did not admit drinking coffee (96 cases), followed by the cases that drink one coffee a day (78 cases, 30.2%). At the opposite side, the statistical analysis marked an exaggerate consumption of coffee in only one subject among the 258 (0.4%) (statistical P: 0.51) (

Figure 17).

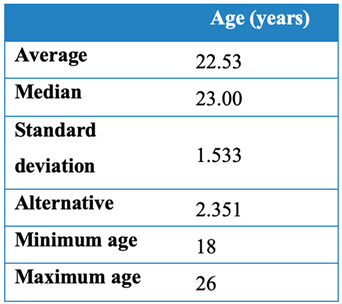

2.17. Coffee Consumption After 17:00

Half of the subjects do not drink coffee after 17:00 (statistical P: 0.573) (

Figure 18).

Figure 13.

Coffee consumption after 17:00.

Figure 13.

Coffee consumption after 17:00.

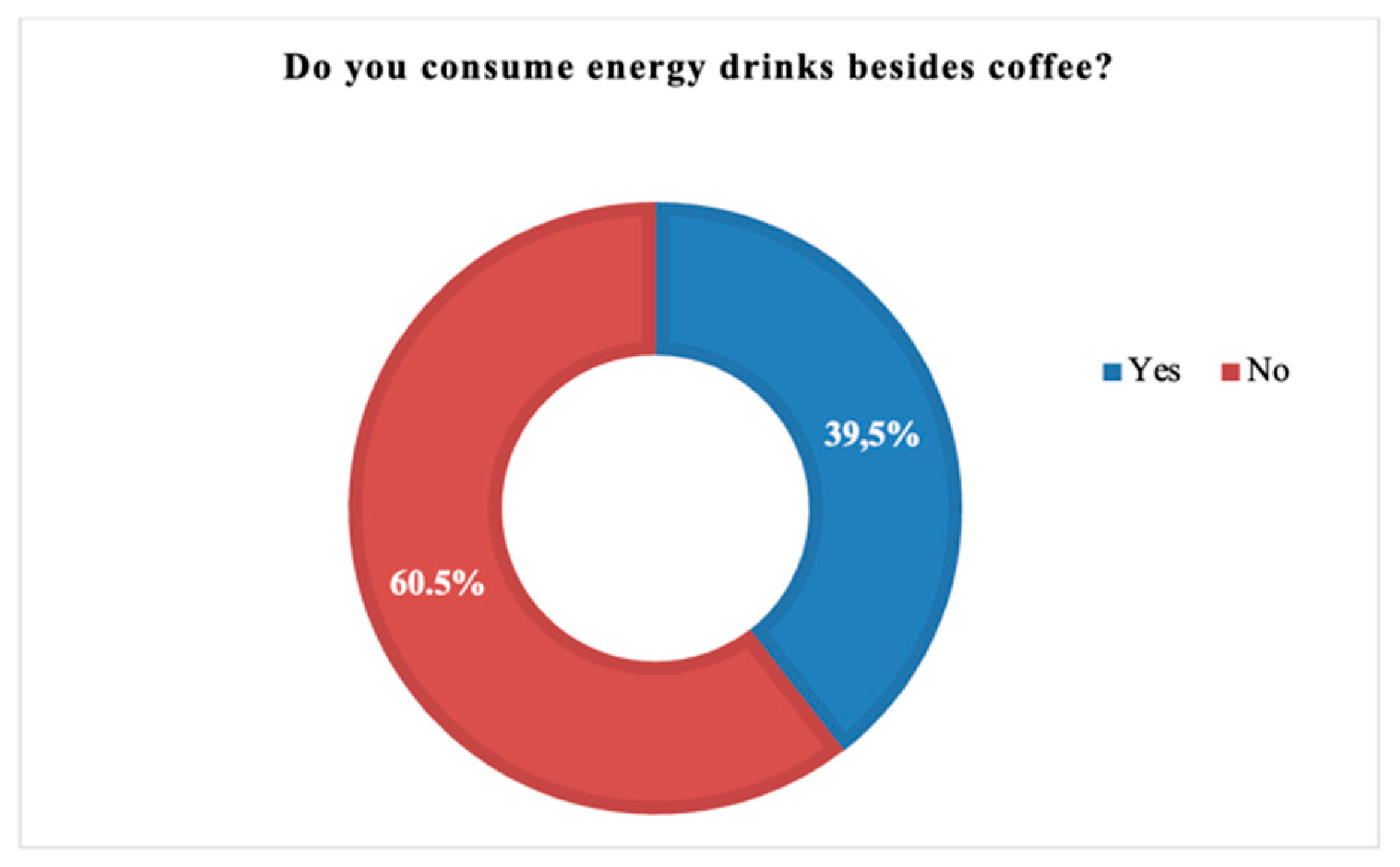

2.18. Consumption of other Energy Drinks (Soft/Energy Drinks, Black Tea)

39,5% 5% of the subjects declared consumption of energy drinks, in addition to coffee (102 cases) (statistical P: 0.088) (

Figure 19).

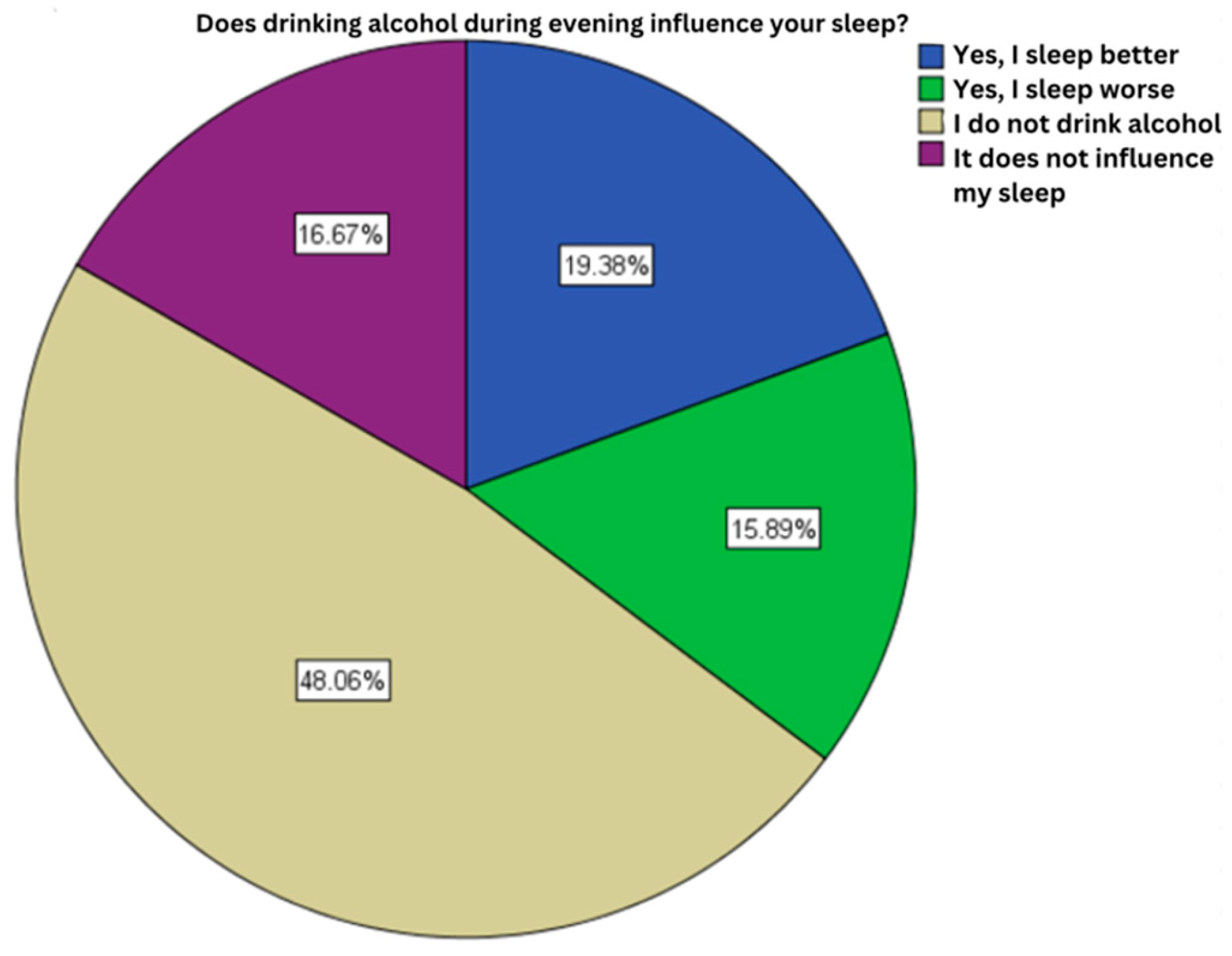

2.19. Alcohol Influence on Sleep Quality

48,1% of the subjects enrolled in this study haven’t consumed alcohol (124 cases), a category followed in percentage, by those who admit an improvement of sleep secondary to alcohol consumption (50 cases, 19.4%) (statistical P 0.023) (

Figure 20).

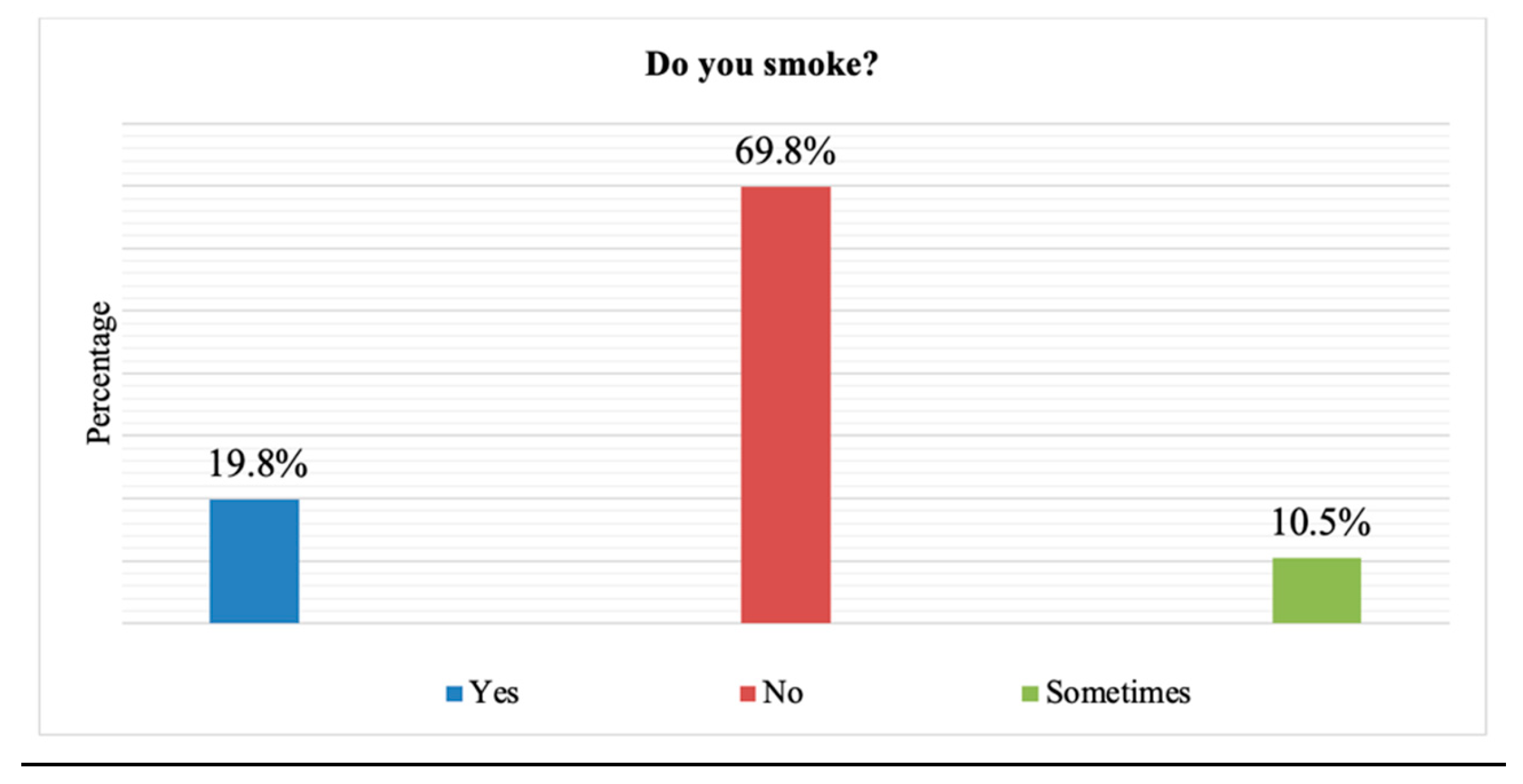

2.20. Smoking

Chronic smoking was identified with the help of statistical analysis in a small percentage of subjects of only 19.8% (51 cases) (statistical P: 0.036) (

Figure 21).

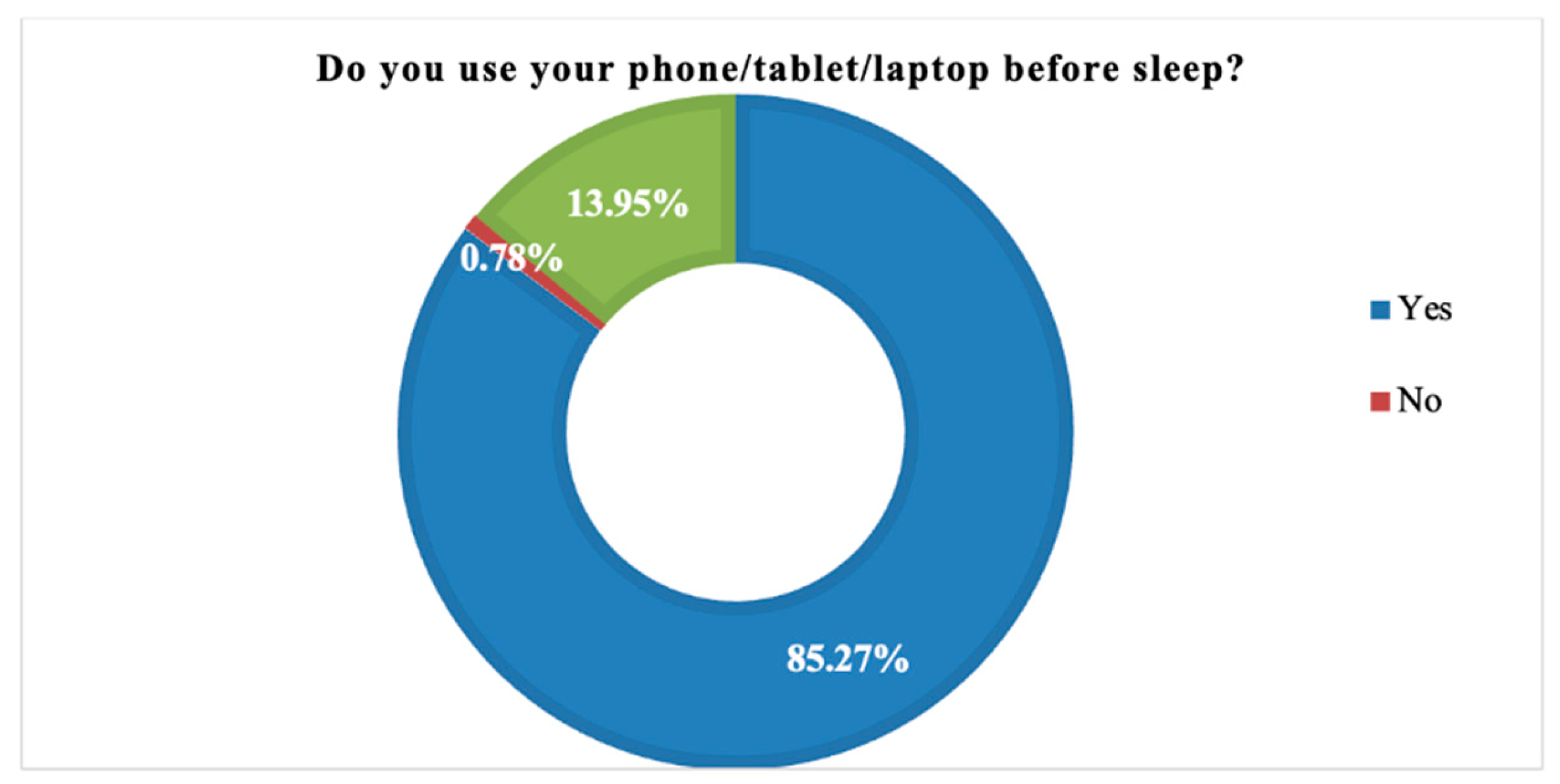

2.21. Using Electronics Before Bed

The majority of subjects enrolled in our study admitted using some electronic devices (phone, tablet, laptop) before falling asleep (statistical P: 0.018) (

Figure 22).

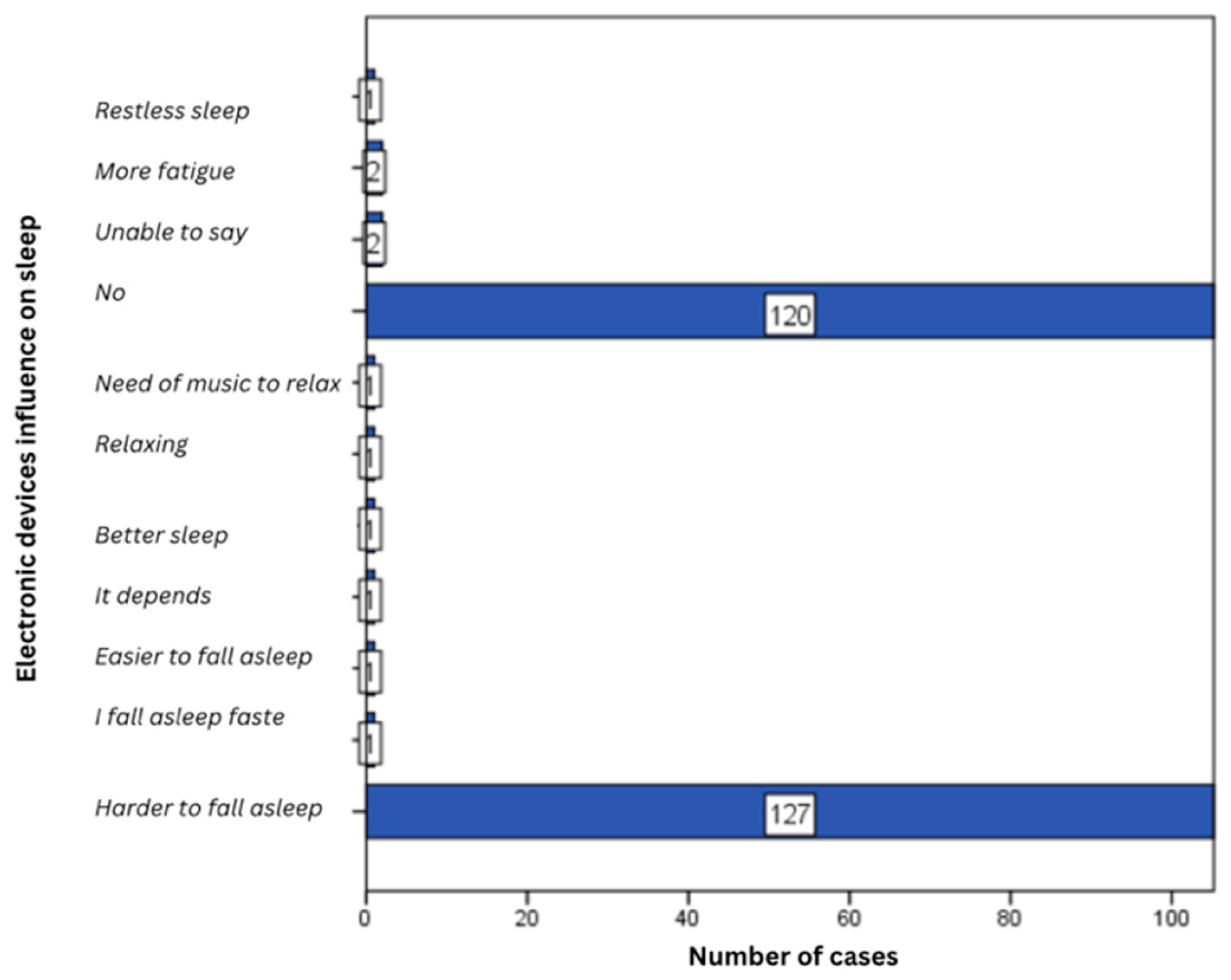

2.22. Electronic Devices Influence on Sleep

About 50% of subjects admitted sleeping difficulties when using electronic devices before going to sleep (127 cases), followed at a slight difference by those who did not experience sleeping difficulties after using electronic devices before sleep (120 cases, 46.5%) (statistical P: 0.681) (

Figure 23).

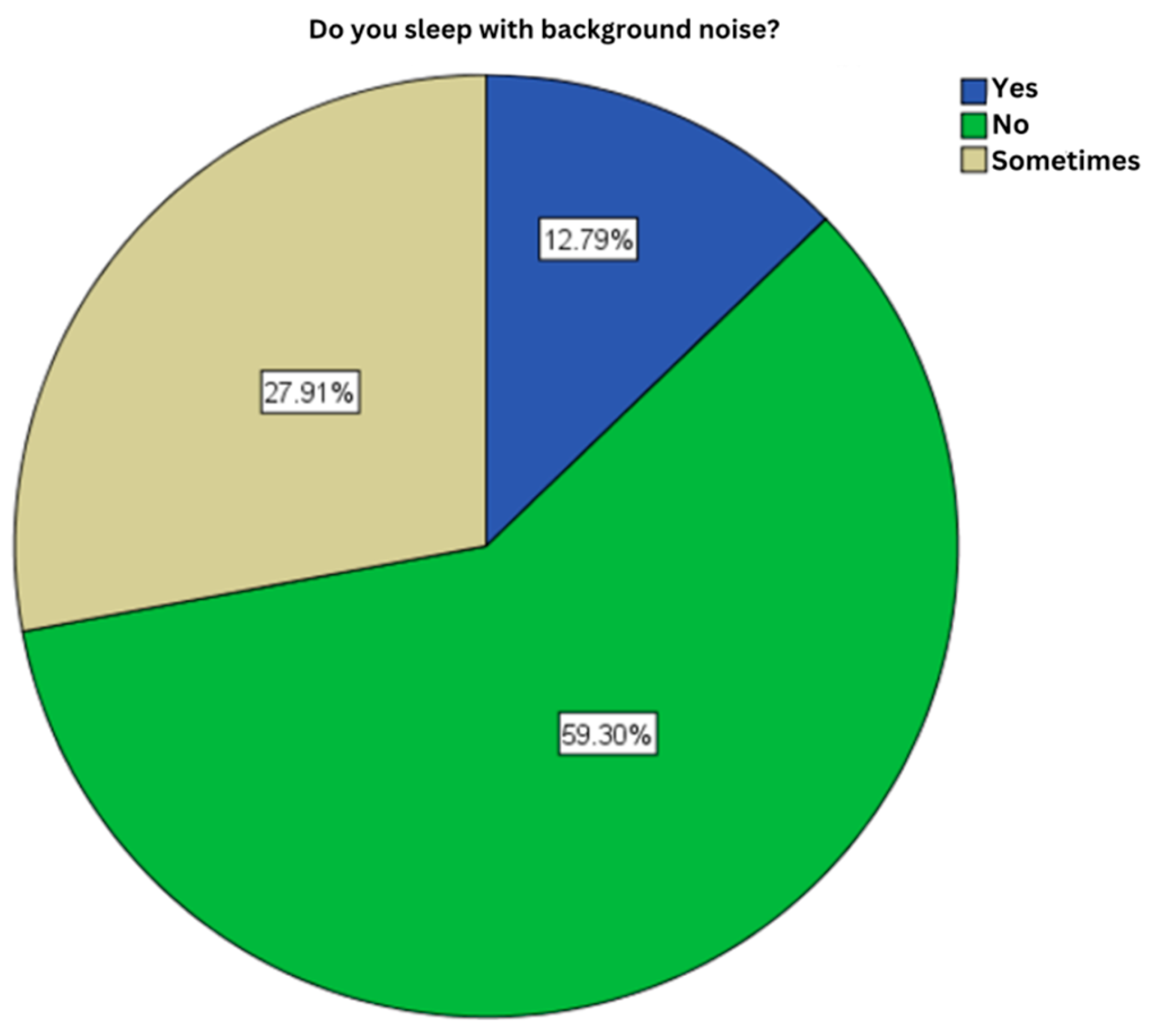

2.23. Background Noises While Sleeping

Approximately 60% of subjects do not sleep with background noise (153 cases) (statistical P: 0.055) (

Figure 24).

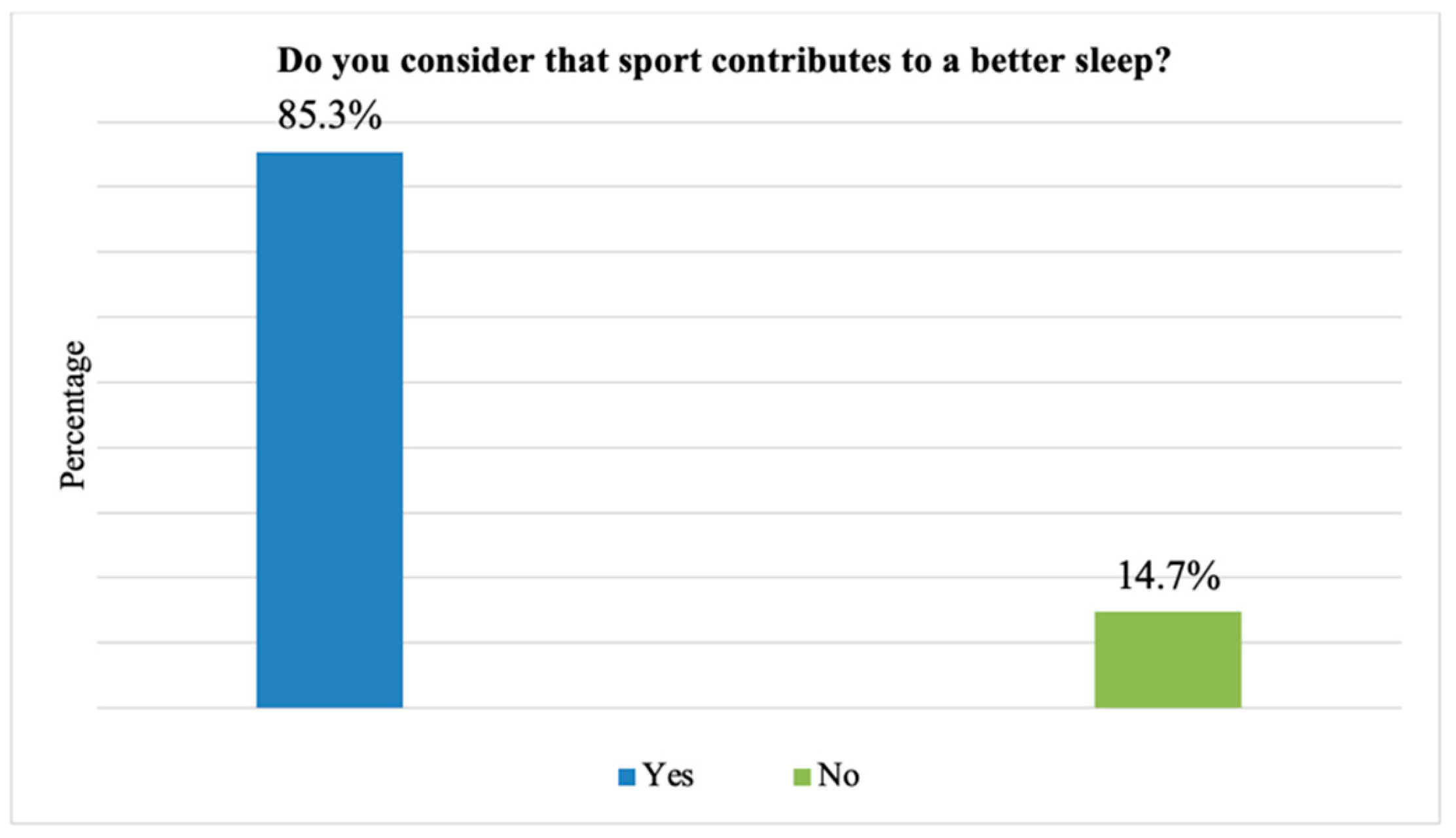

2.24. The Influence of Physical Exercises

85.3% of cases admit a positive effect of physical activity on sleep quality (220 cases) (statistical P: 0.044) (

Figure 25).

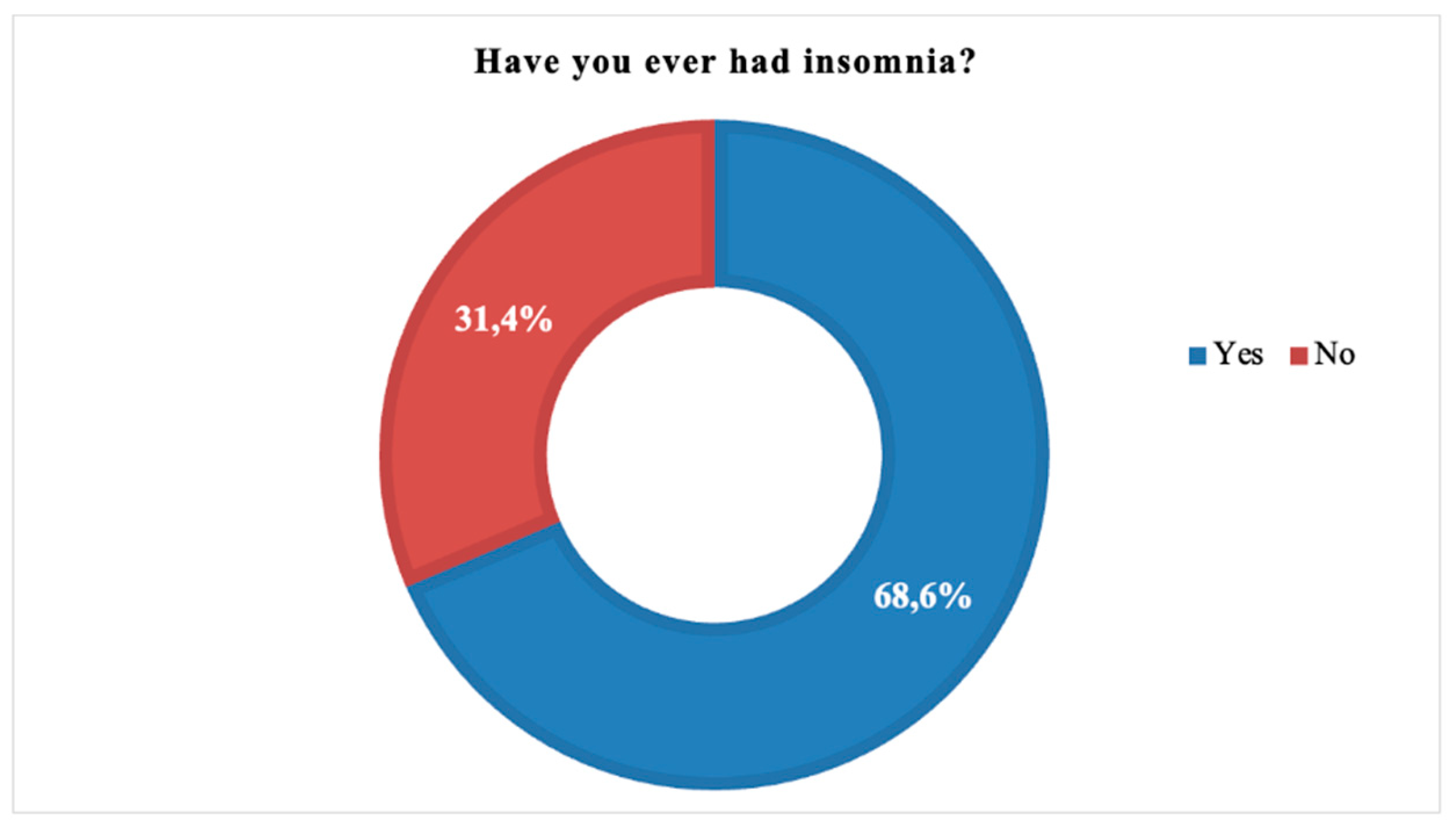

2.25. Insomnia

68.6% of the subjects experienced insomnia at least once (177 cases) (statistical P: 0.004) (

Figure 26).

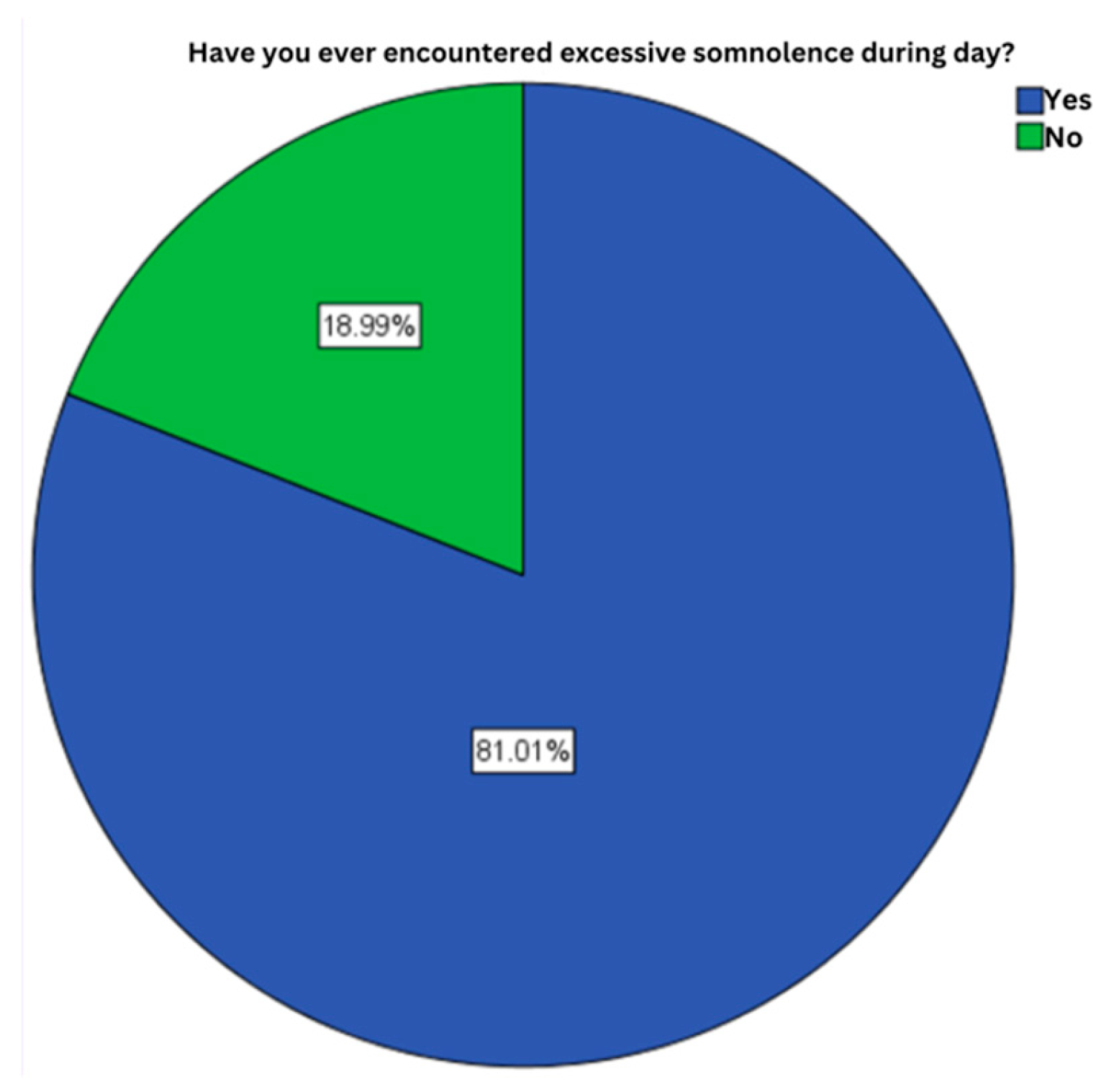

2.26. Excessive Daytime Somnolence

81% of the subjects enrolled in the study, admit the presence of excessive sleepiness/somnolence during the day (209 cases) (statistical P: 0.023) (

Figure 27).

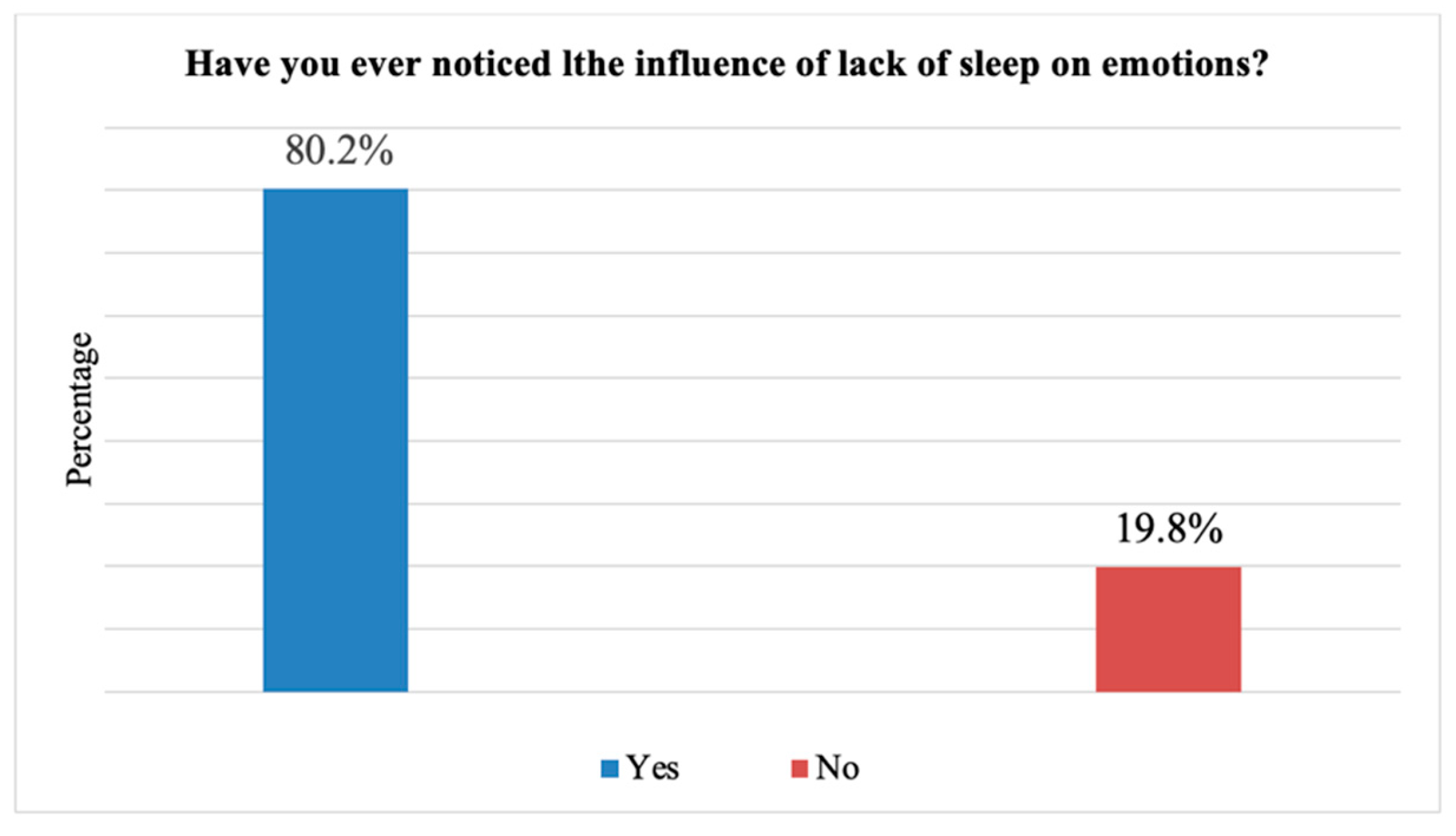

2.27. Sleep Influence on Emotional Sensibility

80.2% of the cases confirm the existence of a link between lack of sleep and emotional sensitivity expressed by irritability, anxiety, low self-esteem (207 cases) (statistical P: 0.008) (

Figure 28).

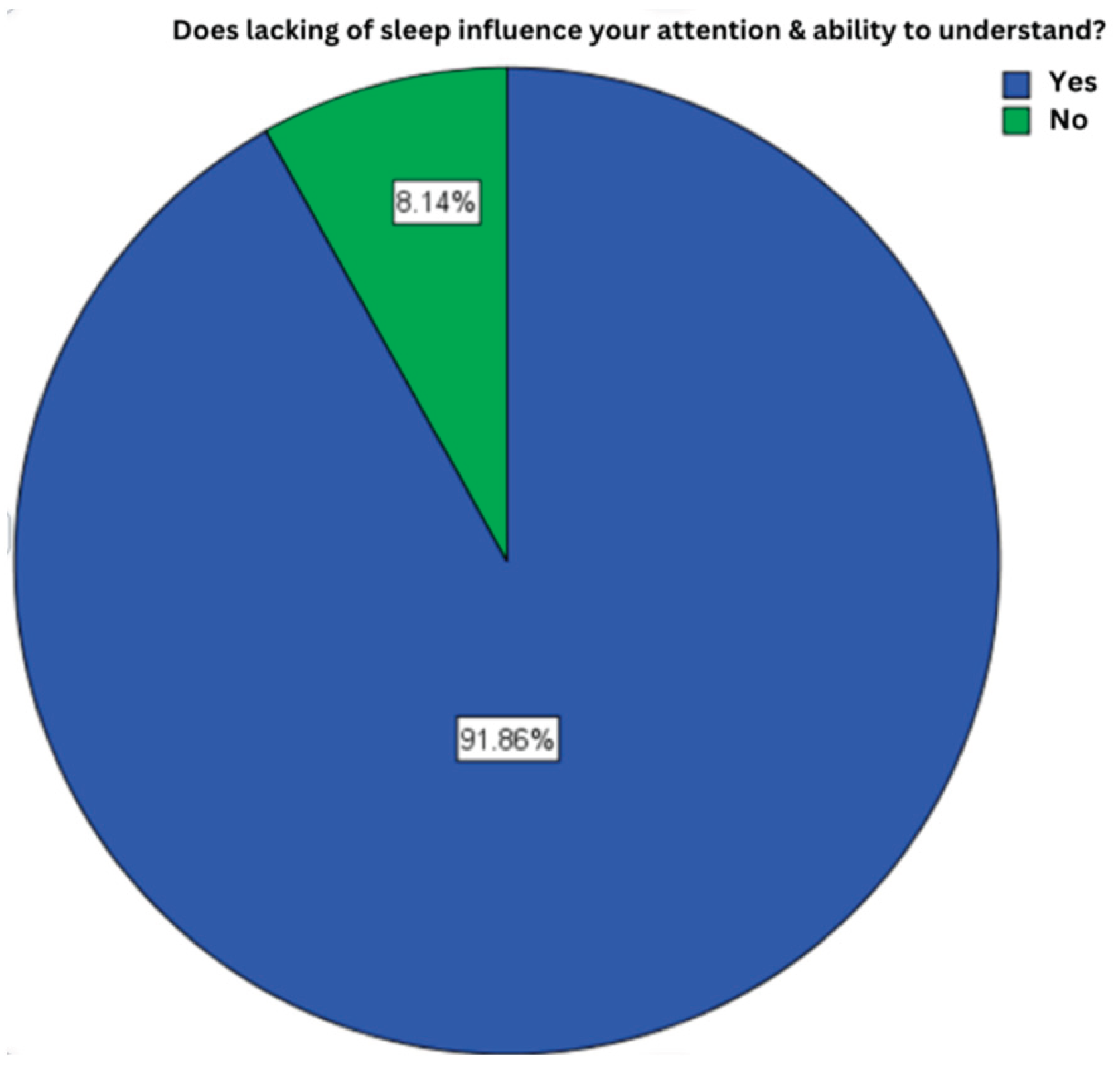

2.28. Sleep Influence on the Ability to Understand

91,9% of the subjects offered an affirmative answer, meaning that 257 subjects experienced a decrease in comprehension caused by lack of sleep (statistical P: 0.033) (

Figure 29).

3. Discussion

Following the demographic statistical analysis data of the 258 participants of this study, women were represented by a percentage of 69.4% (179 cases), and men only by 30.6% (79 cases), both categories having ages between 18 and 26 years, with an average of 22 years. Referring to the field of study, approximately half of the students (45.3%) were attending the Faculty of Medicine at the time of the current study, followed by those from the Faculty of Sociology and Psychology with a percentage of 13.9%, respectively, those from the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism (6.8%).

In terms of knowledge about sleep hygiene, only 151 cases out of 258 (58.5%) were aware of the subject, while the majority believed that sleep duration and quality are important.

According to the recommendations of the National Sleep Foundation in the United States, an adult should sleep between 7 and 9 hours per night, a sleep length less than 7 hours having negative health effects (5). In the present study, only a small percentage of students, 6.2% (16 cases) slept less than 6 hours per night, the majority complying with these recommendations. As for sleeping hours, most of the subjects, 45.74% (118 cases), slept before midnight, while a percentage of 29.5% (76 cases) slept later than midnight.

Hershner SD, Chervil RD and their collaborators have shown that the effect of caffeine can last between 5.5 and 7.5 hours, which is why this substance should be avoided in the afternoon. Also, coffee consumption can double the latency period of sleep (16). In this study, coffee consumption was moderate, most participants consuming one or two coffees per day, but a percentage of 19.8% (51 cases) admitted coffee consumption in the afternoon, respectively after 5:00 p.m. Also, 39.5% (102 cases) consumed other energy drinks besides coffee (black tea, soft drinks).

Studies have shown that nicotine affects sleep by lengthening the latency period and shortening the total sleep time (18). Chronic smoking was identified in 51 cases (19.8%), while 27 cases (10.5%) were occasional smokers.

Also, Irish LA and colleagues stated that background noise during sleep hours can disrupt its quality (18). More than half of our subjects do not sleep with background noise, but there is a percentage of 12.8% who encounter background noises during sleep, and 27.9% of subjects that sometimes experience noise during sleep.

It has been proven that alcohol decreases the latency period, a positive effect at first, but at the same time it fragments sleep (16). From our subjects who consumed alcohol, only 15.89% reported altered sleep quality, while 19.38% reported better sleep, probably due to the positive effect of alcohol on sleep latency period.

Physical activity has a positive effect on sleep as well, reducing psychosocial stress and the number of awakenings during the night (18). The positive influence of physical activity on the quality and duration of sleep could also be observed in this study, 85.3% (220 cases) confirming this hypothesis.

The use of electronic devices, according to the study undertaken by Hershner SD and his collaborators, leads to increased latency and less restful sleep as blue light coming from these sources causes melatonin levels to drop, leading to difficulties in falling asleep (16). In support of these statements our results showed that a majority of students, 85.27% use at least one electronic device before going to sleep, and about half of them (127 cases) admitted having difficulties falling asleep and even feeling more tired or experiencing restlessness during sleep.

Considering these aspects discussed so far, and how all these factors are intricated in sleep quality, duration and latency period, we also observed in the students included by our study, a time interval until falling asleep of 10-20 minutes in 24.4% of cases, category closely followed by 24.03% of those fall asleep between 5 or 10 minutes. Also, there are 33 cases where the sleep latency period was 1-5 minutes, but at the same time at the opposite pole are those with a latency period of 20-30 minutes (20.5%), respectively over 30 minutes (18.2%). By collecting the cases with a sleep latency period longer than 10 minutes, we would have 163 cases (63.1%), this confirming that the lifestyle, namely coffee consumption, use of alcohol, smoking, using electronic devices have a negative effect on sleep. These factors also influence the level of rest, half of the participants’ ratings being positioned in the middle of 1 to 5 scale of rest level. Moreover, 32 students stated that they feel very tired while only 17 admitted feeling well-rested.

The circadian rhythm can be disrupted by the irregular times at which an individual goes to sleep, as well as daytime sleep (longer than 30 minutes) (18). The existence of a regular sleep schedule was noticed in 155 cases (60.1%), and of the total participants, 31.4% (81 cases) admitted that they were sleeping during the day.

After the COVID-19 pandemic, people’s daily schedules have changed, in some cases, also their sleep schedule. In this paper, about half of the students were not affected by the pandemic, while the other half is divided into two categories: that of individuals who sleep more (101 cases - 39.1%) and those who sleep less (39 cases - 15.1%).

A chaotic sleep schedule varying from day to day, along with hours of sleep sacrificed in favor of work, leads to accumulation of fatigue during the week, while during the weekend, individuals end up sleeping more than recommended, order to compensate. This inconsistency in sleep duration and irregular sleep schedule result in lower academic performance on the long term (22). In the present study, as we expected, students sleep more on weekends compared to the rest of the week, with 66.3% admitting this fact (171 cases), while only 47.7% (123 cases) stated feeling more tired at the end of the week.

Lemma S along with his collaborators, concluded that both duration and quality of sleep have effects on the results obtained within the examinations that students go through. Thus, the lower the number of hours of sleep and its unsatisfactory quality, the poorer the academic performance is (29). When asked if the same number of hours of sleep is kept during the examination session as in the rest of the year, only 36.43% admitted this fact. In contrast, about half of the students (53.10%) reported sleeping less during this period. Numerous relatively recent studies, including that of Rasch B together with Born J, have shown how important sleep is in the learning process, stating that sleep occurring after learning information leads to consolidation of long-term memory (26). It is becoming increasingly clear that in order to reach the best academic performance, sleep is very important. Even so, 43 students from the group enrolled in the study (16.7%) choose not to sleep at all the night before an exam.

Insomnia represents a sleep disorder defined by awakenings during the night, difficulty in falling asleep, fatigue, emotional sensitivity and concentration problems (40). In a study conducted in Jordan, a 26.0% prevalence of insomnia could be observed among college students (41). More than half (68.6%) of the students in this study stated that they suffered or have suffered from insomnia at some point, but these results were not obtained following specialized questionnaires dedicated to insomnia. However, we can expect temporary insomnia in our cases, especially during examination periods when those subjects experience higher stress levels responsible for many sleep disorders.

Sleep deprivation has negative effects on quality of life, one of these being excessive sleepiness. El Hangouche AJ and his collaborators conducted a study in which they stated that 12%-16% of the general population suffer from excessive daytime sleepiness, but among students this percentage is slightly higher (42). Asked if they had ever experienced excessive daytime sleepiness, 81.01% of our subjects responded positively, confirming once again that their quality of sleep is inadequate.

Another effect of sleep deprivation is emotional sensitivity, expressed through irritability, anxiety, dramatization, low self-esteem (9). Following the study conducted by Milojevich HM and colleagues, it was demonstrated that following the reduction of sleep quality, the level of aggression and psychological disorders increased both worldwide, especially in the case of students (10). The results of our paper regarding the influence of sleep on emotional sensitivity do not differ from the results of other studies in this field, a number of 207 cases (80.2%) admitted that lack of sleep also leaves its mark on their emotional health.

As seen in several studies, reduced sleep accumulates over time resulting in reduced ability to focus (31). The reduction of attention, the ability to concentrate and memorize in relation to sleep deprivation was also observed in this study, a percentage of 91.86% admitting this statement.

4. Materials and Methods

Our study included 258 subjects that took part and completed a questionnaire containing a series of questions related to sleep hygiene. Our lot was composed by students from different Romanian universities.

The questionnaire contained 32 questions with multiple or single choice questions and sections in which our respondents filled in with text. Most of the questions referred to: participants demographic data, level of sleep hygiene knowledge, data about participants’ sleep schedule (hours sleep per night, sleeping times and the time interval before falling asleep). Other questions referred to any differences between rest and sleep hours during the week versus the weekend compared to exam sessions, when this group is more likely not to sleep properly. Participants were also asked about having a regular sleep schedule, being aware of sleep hygiene concepts (drinking coffee or any energy drinks, using electronic devices before bed, smoking, background noises). Extensive information on the effects of sleep deprivation was collected by asking the subjects about: experiencing excessive daytime sleepiness, having at least one episode of insomnia, or any episode of emotional hypersensitivity caused by lack of sleep, attention deficits and inability to understand information.

The questionnaire was distributed to students through social platforms, in March-September 2021.

4.1. Statistical Data Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation. These variables were compared with the help of the Student T test. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and/or percentages, compared as Person Chi-square test. The statistical tests are 2-tailed, with a P value <0.05, the latter being considered statistically significant. All statistical analyzes included odd ratio (OR) and were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics (Statistical Package for social Sciences) version 20.

5. Conclusions

Our study included 258 students enrolled in different faculties in Romania, 179 females, 79 males, aged between 18 and 26 years. At the end of this study, we were able to establish the following facts: 58.53% of participants knew what sleep hygiene entails; the majority of those enrolled in the study believed that the duration and quality of sleep are important in order to maintain a healthy lifestyle; the recommended number of hours of sleep (7-8 hours/night) was respected by most subjects; about slightly less than half of the subjects fell asleep before midnight, 63 cases having a time interval until falling asleep of 10-20 minutes, category closely followed by those with 5-10 minutes (62 cases); a regular sleep schedule was adopted by only 39.9% of participants; only in 51 cases admitted coffee consumption after dinner, while 39.5% of all subjects also consumed other energy drinks; most students used electronic devices (phone, tablet, laptop) before going to sleep, and about half of them noticed that it is harder to fall asleep while using this kind of devices; the positive effects of physical activity on sleep quality were observed by the majority of study participants (85.3%); from subjects who admit drinking alcohol in the evening, only 15.89% experienced sleeping difficulties; given their busy schedule, 47.7% of students felt more tired at the end of the week, resulting in more than half of subjects sleeping more during weekends compared to the rest of the week; 53.10% of the study participants slept less during the examination session, and 16.67% of the total chose not to sleep at all the night before an exam; the COVID-19 pandemic also had repercussions on sleep, with 101 subjects (39.1%) declaring that they have been sleeping more since the outbreak; excessive daytime sleepiness was observed in 209 cases (81%); 177 students (68.6%) experienced at least one episode of temporary insomnia; 80.2% of subjects (207 cases) confirmed the existence of a link between lack of sleep and emotional sensitivity; decreased attention or comprehension as a result of insufficient sleep duration was noted in 257 subjects (91.9%).

Following the results obtained in this study, we can state that some habits (caffeine consumption, nicotine and alcohol, insufficient physical activity, electronic devices use before sleeping) influence the quality and duration of sleep, these factors being present in the daily lives of a student. Lower student life quality, indicated by altered ability to understand, emotional health and low academic performance, are a result of an inadequate sleep hygiene, which is caused on one hand by insufficient awareness on this topic, but also by ignoring sleep hygiene recommendations. .

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Miloicov Bacean Oana Codruta; Data curation, Văcaru Gabriel Cristian; Investigation, Borca Ciprian Ioan and Folescu Roxana; Writing – original draft, Anuțoni Debora Delia; Writing – review & editing, Simbrac Mihaela Cristina .

Ethical Issues

The research was conduced in accordance with the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance obtained from “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Center for Studies in Preventive Medicine, Timisoara, Romania, Institutional Review Board, research support officers. The research’s objectives, benefit and risks were explained to the participants before data collection and obtained written informed consent from the study participants. The research participants were assured of the attainment of confidentiality, and the information they give us will not be used for any purpose other than the research.

References

- Sleep health: can we define it? Does it matter? DJ, Buysse. s.l. : Sleep, 2014, Vol. 37(1): 9-17. [CrossRef]

- Sleep Health: Reciprocal Regulation of Sleep and Innate Immunity. Irwin MR, Opp MR. s.l. : Neuropsychopharmacology, 2017, Vol. 42(1): 129-155. [CrossRef]

- Exploring sex and gender differences in sleep health: a Society for Women’s Health Research Report. Mallampalli MP, Carter CL. s.l. : J Womens Health (Larchmt)., 2014, Vol. 23(7): 553-562. [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, Wallace B. The science of sleep: what it is, how it works, and why it matters. s.l. : The University of Chicago Press, 2017.

- Prevalence of short sleep duration and effect of co-morbid medical conditions - A cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Althakafi KA, Alrashed AA, Aljammaz KI, et al. s.l. : J Family Med Prim Care., 2019, Vol. 8(10): 3334-3339. [CrossRef]

- The association of stress with sleep quality among medical students at King Abdulaziz University. Safhi MA, Alafif RA, Alamoudi NM, et al. s.l. : J Family Med Prim Care., 2020, Vol. 9(3): 1662-1667. [CrossRef]

- Relationships Among Nightly Sleep Quality, Daily Stress, and Daily Affect. Blaxton JM, Bergeman CS, Whitehead BR, et al. s.l. : J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci., 2017, Vol. 72(3): 363-372. [CrossRef]

- Quality of Sleep and Depression in College Students:A Systematic Review. Dinis J, Bragança M. s.l. : Sleep Sci., 2018, Vol. 11(4): 290-301. [CrossRef]

- The Impact of a Randomized Sleep Education Intervention for College Students. Hershner S, O’Brien LM. s.l. : J Clin Sleep Med., 2018, Vol. 14(3): 337-347. [CrossRef]

- Sleep and Mental Health in Undergraduate Students with Generally Healthy Sleep Habits. Milojevich HM, Lukowski AF. s.l. : PLoS One., 2016, Vol. 11(6):e0156372. [CrossRef]

- Sleeping at the Limits: The Changing Prevalence of Short and Long Sleep Duration in 10 Countries. Bin YS, Marshall NS, Glozier N, et al. 8, s.l. : American Journal of Epidemiology., 2013, Vol. 177: 826-833. [CrossRef]

- The Association between Sleep Duration and Metabolic Syndrome: The NHANES 2013/2014. Smiley A, King D, Bidulescu A. s.l. : Nutrients., 2019, Vol. 11(11):2582. [CrossRef]

- Association of physical activity, sedentary time, and sleep duration on the health-related quality of life of college students in Northeast China. Ge Y, Xin S, Luan D, et al. s.l. : Health Qual Life Outcomes., 2019, Vol. 17(1): 124. [CrossRef]

- Sex-specific sleep patterns among university students in Lebanon: impact on depression and academic performance. Kabrita CS, Hajjar-Muça TA. s.l. : Nat Sci Sleep., 2016, Vol. 8: 189-196. [CrossRef]

- Sleep hygiene awareness: its relation to sleep quality and diurnal preferences. Voinescu BI, Szentagotai-Tatar A. s.l. : J Mol Psychiatry., 2015, Vol. 3(1): 1. [CrossRef]

- Causes and consequences of sleepiness among college students. Hershner SD, Chervin RD. s.l. : Nat Sci Sleep., 2014, Vol. 6: 73-84. [CrossRef]

- Matthew Walker, PhD. Why we sleep: unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. s.l. : SCRIBNER, 2017.

- The role of sleep hygiene in promoting public health: A review of empirical evidence. Irish LA, Kline CE, Gunn HE, et al. s.l. : Sleep Med Rev., 2015, Vol. 22: 23-36. [CrossRef]

- Chronic sleep reduction is associated with academic achievement and study concentration in higher education students. van der Heijden KB, Vermeulen MCM, Donjacour CEHM, et al. s.l. : J Sleep Res., 2018, Vol. 27(2): 165-174. [CrossRef]

- Why sleep is important for health: a psychoneuroimmunology perspective. . MR., Irwin. s.l. : Annu Rev Psychol., 2015, Vol. 66: 143-172. [CrossRef]

- Sleep Disturbance, Sleep Duration, and Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies and Experimental Sleep Deprivation. Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carroll JE. s.l. : Biol Psychiatry., 2016, Vol. 80(1): 40-52. [CrossRef]

- Sleep quality, duration, and consistency are associated with better academic performance in college students. Okano K, Kaczmarzyk JR, Dave N, et al. s.l. : NPJ Sci Learn., 2019, Vol. 4:16. [CrossRef]

- Sleep Duration and Academic Performance Among Student Pharmacists. Zeek ML, Savoie MJ, Song M, et al. s.l. : Am J Pharm Educ., 2015, Vol. 79(5):63. [CrossRef]

- Effects of sleep on memory for conditioned fear and fear extinction. Pace-Schott EF, Germain A, Milad MR. s.l. : Psychol Bull., 2015, Vol. 141(4):835-857. [CrossRef]

- The effects of sleep on prospective memory: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Leong RLF, Cheng GH, Chee MWL, et al. s.l. : Sleep Med Rev., 2019, Vol. 47:18-27. [CrossRef]

- About sleep’s role in memory. Rasch B, Born J. s.l. : Physiol Rev., 2013, Vol. 93(2):681-766. [CrossRef]

- Sleep promotes branch-specific formation of dendritic spines after learning. Yang G, Lai CS, Cichon J, et al. s.l. : Science., 2014, Vol. 344(6188):1173-1178. [CrossRef]

- Sleep homeostasis, habits and habituation. Vyazovskiy VV, Walton ME, Peirson SN, et al. s.l. : Curr Opin Neurobiol., 2017, Vol. 44:202-211. [CrossRef]

- Good quality sleep is associated with better academic performance among university students in Ethiopia. Lemma S, Berhane Y, Worku A, et al. s.l. : Sleep Breath., 2014, Vol. 18(2):257-263. [CrossRef]

- The Impact of Duration of Sleep on Academic Performance in University Students. Raley HR, Naber JL, Cross S, et al. s.l. : Madridge J Nurs., 2016, Vol. 1(1):11-18. [CrossRef]

- The Eight Hour Sleep Challenge During Final Exams Week. MK., Scullin. s.l. : Teaching of Psychology., 2019, Vol. 46(1):55-63. [CrossRef]

- Sleep problems and suicidal behaviors in college students. Becker SP, Dvorsky MR, Holdaway AS, et al. s.l. : J Psychiatr Res., 2018, Vol. 99:122-128. [CrossRef]

- Let’s talk about sleep: a systematic review of psychological interventions to improve sleep in college students. Friedrich A, Schlarb AA. s.l. : J Sleep Res., 2018, Vol. 27(1):4-22. [CrossRef]

- The 8-Hour Challenge: Incentivizing Sleep during End-of-Term Assessments. King E, Scullin MK. s.l. : J Inter Des., 2019, Vol. 44(2):85-99. [CrossRef]

- Sleep characteristics and health-related quality of life among a national sample of American young adults: assessment of possible health disparities. . Chen X, Gelaye B, Williams MA. s.l. : Qual Life Res., 2014, Vol. 23(2):613-625. [CrossRef]

- Insomnia among Medical and Paramedical Students in Jordan: Impact on Academic Performance. Alqudah M, Balousha SAM, Al-Shboul O, et al. s.l. : Biomed Res Int., 2019, Vol. 2019:7136906. [CrossRef]

- Sleep Alterations in Female College Students with Migraines. Rodríguez-Almagro D, Achalandabaso-Ochoa A, Obrero-Gaitán E, et al. s.l. : Int J Environ Res Public Health., 2020, Vol. 17(15):5456. [CrossRef]

- Sleep quality and body mass index in college students: the role of sleep disturbances. Vargas PA, Flores M, Robles E. s.l. : J Am Coll Health., 2014, Vol. 62(8):534-541. [CrossRef]

- Association between sleep duration and metabolic syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Kim CE, Shin S, Lee HW, et al. s.l. : BMC Public Health., 2018, Vol. 18(1):720. [CrossRef]

- Medicine, American Academy of Sleep. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition. s.l. : Darien, IL : American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2014. 0991543408.

- Insomnia among Medical and Paramedical Students in Jordan: Impact on Academic Performance. Alqudah M, Balousha SAM, Al-Shboul O, et al. s.l. : Biomed Res Int., 2019, Vol. 2019:7136906. [CrossRef]

- Relationship between poor quality sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness and low academic performance in medical students. El Hangouche AJ, Jniene A, Aboudrar S, et al. s.l. : Adv Med Educ Pract., 2018, Vol. 9:631-638. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Gender distribution of subjects.

Figure 1.

Gender distribution of subjects.

Figure 3.

Distribution of patients according to their followed studies.

Figure 3.

Distribution of patients according to their followed studies.

Figure 4.

Subjects aware of sleep hygiene.

Figure 4.

Subjects aware of sleep hygiene.

Figure 5.

Importance of sleep length and quality.

Figure 5.

Importance of sleep length and quality.

Figure 6.

Sleeping hours.

Figure 6.

Sleeping hours.

Figure 7.

Number of hours slept per night.

Figure 7.

Number of hours slept per night.

Figure 8.

Time interval until falling asleep.

Figure 8.

Time interval until falling asleep.

Figure 9.

Levels of rest.

Figure 9.

Levels of rest.

Figure 10.

Fatigue level at the end of the week.

Figure 10.

Fatigue level at the end of the week.

Figure 11.

Share of subjects who sleep more on weekends.

Figure 11.

Share of subjects who sleep more on weekends.

Figure 12.

Share of sleep length in the exam session.

Figure 12.

Share of sleep length in the exam session.

Figure 13.

Share of subjects that do not sleep at all before an exam.

Figure 13.

Share of subjects that do not sleep at all before an exam.

Figure 14.

The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on sleep.

Figure 14.

The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on sleep.

Figure 15.

Share of subjects with a regular sleep schedule.

Figure 15.

Share of subjects with a regular sleep schedule.

Figure 16.

Share of subjects sleeping during the day.

Figure 16.

Share of subjects sleeping during the day.

Figure 17.

Daily coffee consumption.

Figure 17.

Daily coffee consumption.

Figure 19.

Share of subjects who consume other energy drinks.

Figure 19.

Share of subjects who consume other energy drinks.

Figure 20.

Alcohol influence on sleep quality.

Figure 20.

Alcohol influence on sleep quality.

Figure 21.

Share of smoking.

Figure 21.

Share of smoking.

Figure 22.

Stake of subjects using electronic devices before sleep.

Figure 22.

Stake of subjects using electronic devices before sleep.

Figure 23.

Electronic devices influence on sleep.

Figure 23.

Electronic devices influence on sleep.

Figure 24.

Share of subjects sleeping with background noises.

Figure 24.

Share of subjects sleeping with background noises.

Figure 25.

Physical activity influence on sleep.

Figure 25.

Physical activity influence on sleep.

Figure 26.

Stake of subjects that experienced insomnia.

Figure 26.

Stake of subjects that experienced insomnia.

Figure 27.

Share of subjects with excessive daytime somnolence.

Figure 27.

Share of subjects with excessive daytime somnolence.

Figure 28.

Sleep influence on emotional sensitivity.

Figure 28.

Sleep influence on emotional sensitivity.

Figure 29.

Share of subjects with impaired comprehension due to lack of sleep.

Figure 29.

Share of subjects with impaired comprehension due to lack of sleep.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).