Submitted:

04 October 2025

Posted:

07 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Background: This study examined the impact of specific unhealthy eating behaviors on sleep quality (SQ) among university students. Understanding how dietary habits affect sleep during the significant lifestyle transitions that students experience during university life can inform health promotion strategies. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted among international university students using a self-administered questionnaire assessing dietary habits, meal timing, and sleep-related behaviors. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was utilized to assess sleep quality. Statistical analyses were performed to examine the relationship between eating patterns and overall sleep quality and its components. Results: More than half of the 385 students (51.7%) had poor sleep quality, as defined by the PSQI criteria. Daytime dysfunction was significantly more common among females than males (27.9% vs. 8.3%, respectively; p<0.001). Conversely, poor sleep efficiency was more prevalent among males than females (27.5% vs. 15.8%; p=0.008). Multivariate logistic regression revealed that, compared to students who did not frequently consume heavy evening meals, those who did were more likely to experience poor sleep quality (OR = 2.73, 95% CI: 1.575-4.731). Similarly, those who frequently replaced regular meals with snacks were more likely to experience poor sleep quality than those who did not (OR = 2.68, 95% CI: 1.465-4.895). Finally, students who ate within three hours of bedtime had higher odds of poor sleep quality compared to those who had their last meal more than three hours before bedtime (OR = 2.06, 95% CI: 1.173-3.629). Conclusion: Unhealthy dietary habits, such as consuming heavy evening meals, replacing meals with snacks, and a short meal-to-bedtime interval are significantly associated with poor sleep quality. Interventions promoting healthier dietary patterns and appropriate meal timing could help improve sleep and overall well-being in this population.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Collection

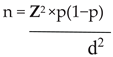

2.5. Sample Size

2.6. Questionnaire Tool

2.6.1. Anthropometric Assessment

2.6.2. Sleep Quality Assessment

2.6.3. Eating Habits Assessment

2.6.4. Coding and Categorization of Variables

2.7. Ethical Approval

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Meal Timing and Sleep Quality

4.1.1. Short Meal-to-Bedtime Interval

4.1.2. Meal Replacement with Snacks

4.1.3. Heavy Evening Meals

4.2. Other Dietary Habits and Their Associations with Sleep Components

4.2.1. Skipping Breakfast

4.2.2. Late-Night Snacking

4.2.3. Irregular Meal Timing

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SQ | Sleep Quality |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| MENA | Middle Eastern & North African |

| AHI | Apnea-Hypopnea Index |

| STROBE | Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| P | Population Proportion |

| GERD | Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease |

References

- Stranges, S.; Tigbe, W.; Gómez-Olivé, F.X.; Thorogood, M.; Kandala, N.-B. Sleep Problems: An Emerging Global Epidemic? Findings From the INDEPTH WHO-SAGE Study Among More Than 40,000 Older Adults From 8 Countries Across Africa and Asia. Sleep 2012, 35, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daley, M.; Morin, C.M.; LeBlanc, M.; Grégoire, J.-P.; Savard, J. The Economic Burden of Insomnia: Direct and Indirect Costs for Individuals with Insomnia Syndrome, Insomnia Symptoms, and Good Sleepers. Sleep 2009, 32, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattu, V.K.; Manzar, M.D.; Kumary, S.; Burman, D.; Spence, D.W.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R. The Global Problem of Insufficient Sleep and Its Serious Public Health Implications. Healthcare 2018, 7, E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohayon, M.M. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med. Rev. 2002, 6, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaranayake, C.; Arroll, B.; Fernando, A.T. Sleep disorders, depression, anxiety and satisfaction with life among young adults: a survey of university students in Auckland, New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2014, 127, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.-L.; Zheng, X.-Y.; Yang, J.; Ye, C.-P.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-G.; Xiao, Z.-J. A systematic review of studies on the prevalence of Insomnia in university students. Public Health. 2015, 129, 1579–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, K.L.; Davis, J.E.; Corbett, C.F. Sleep quality: An evolutionary concept analysis. Nurs. Forum 2022, 57, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., III; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakir, B.; Kılınç, F.N.; Uyar, G.Ö.; Özenir, Ç.; Ekici, E.M.; Karaismailoğlu, E. The relationship between sleep duration, sleep quality and dietary intake in adults. Sleep Biol. Rhythm. 2020, 18, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo, C.M.; del Re, M.P.; Quaresma, M.V.L.d.S.; Antunes, H.K.M.; Togeiro, S.M.; Ribeiro, S.M.L.; Tufik, S.; de Mello, M.T. Relationship of evening meal with sleep quality in obese individuals with obstructive sleep apnea. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2019, 29, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keser, M.G.; Yüksel, A. An Overview of the Relationship Between Meal Timing and Sleep. J. Turk. Sleep Med. 2024, 11, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, T.D.V.C.; Borba, M.E.; Lopes, R.D.V.C.; Fisberg, R.M.; Paim, S.L.; Teodoro, V.V.; Zimberg, I.Z.; Crispim, C.A. Eating Late Negatively Affects Sleep Pattern and Apnea Severity in Individuals with Sleep Apnea. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2019, 15, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Son, B.; Shin, W.-C.; Nam, S.-U.; Lee, J.; Lim, J.; Kim, S.; Yang, C.; Lee, H. Association of Dietary Behaviors with Poor Sleep Quality and Increased Risk of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Korean Military Service Members. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2022, 14, 1737–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoosawi, S.; Vingeliene, S.; Gachon, F.; Voortman, T.; Palla, L.; Johnston, J.D.; Van Dam, R.M.; Darimont, C.; Karagounis, L.G. Chronotype: Implications for Epidemiologic Studies on Chrono-Nutrition and Cardiometabolic Health. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2019, 10, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispim, C.A.; Mota, M.C. New perspectives on chrononutrition. Biol. Rhythm. Res. 2019, 50, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, A.; Bechtold, D.A.; Pot, G.K.; Johnston, J.D. Chrono-nutrition: From molecular and neuronal mechanisms to human epidemiology and timed feeding patterns. J. Neurochem. 2021, 157, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pot, G.K. Chrono-nutrition – an emerging, modifiable risk factor for chronic disease? Nutr. Bull. 2021, 46, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delabos, A. Mincir sur mesure grâce à la chrono-nutrition [Internet]. Beograd: Vulkan izdavaštvo; 2016. 20 p. Available online: https://www.knjizara.com/pdf/147598.pdf.

- Tarquini, R.; Mazzoccoli, G. Clock Genes, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Risk. Heart. Fail. Clin. 2017, 13, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.A.; Zaman, A.; Cornier, M.-A.; Catenacci, V.A.; Tussey, E.J.; Grau, L.; Arbet, J.; Broussard, J.L.; Rynders, C.A. Later Meal and Sleep Timing Predicts Higher Percent Body Fat. Nutrients 2021, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, H.S.; Gómez-Abellán, P.; Qian, J.; Esteban, A.; Morales, E.; Scheer, F.A.; Garaulet, M. Late eating is associated with cardiometabolic risk traits, obesogenic behaviors, and impaired weight loss. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doo, M.; Wang, C. Associations among Sleep Quality, Changes in Eating Habits, and Overweight or Obesity after Studying Abroad among International Students in South Korea. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Facts and Figures, Mobility in Higher Education. [Internet]. UNESCO; 2025 [cited 2025 ]. Available online: http://data.uis.unesco.org.

- International Organization for Migration. World Migration Report 2024: Chapter 2 – International Students [Internet]. International Organization for Migration (IOM); 2024 [cited 2025 May 27]. 2024. Available online: https://worldmigrationreport.iom.int/what-we-do/world-migration-report-2024-chapter-2/international-students.

- Lachat, C.; Hawwash, D.; Ocké, M.C.; Berg, C.; Forsum, E.; Hörnell, A.; Larsson, C.L.; Sonestedt, E.; Wirfält, E.; Åkesson, A.; et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology – nutritional epidemiology (STROBE-nut): An extension of the STROBE statement. Nutr. Bull. 2016, 41, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Pécs. About the University of Pécs [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 5]. Available online: https://international.pte.hu/university/about-university-pecs.

- Jager, J.; Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. II. More than just convenient: the scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2017, 82, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwafi, H.; Alwafi, R.; Naser, A.Y.; Samannodi, M.; Aboraya, D.; Salawati, E.; et al. The Impact of Social Media Influencers on Food Consumption in Saudi Arabia, a Cross-Sectional Web-Based Survey. JMDH 2022, 15, 2129–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naing, N.N. Determination of sample size. Malays J Med Sci. 2003, 10, 84–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Faris, M.E.; Vitiello, M.V.; Abdelrahim, D.N.; Ismail, L.C.; Jahrami, H.A.; Khaleel, S.; Khan, M.S.; Shakir, A.Z.; Yusuf, A.M.; Masaad, A.A.; et al. Eating habits are associated with subjective sleep quality outcomes among university students: findings of a cross-sectional study. Sleep Breath. 2022, 26, 1365–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttall, F.Q. Body Mass Index: Obesity, BMI, and Health: A Critical Review. Nutr. Today 2015, 50, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. The Asia-Pacific perspective : redefining obesity and its treatment [Internet]. Sydney : Health Communications Australia; 2000 [cited 2025 Jan 5]. ISBN: 978-0-9577082-1-1. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/206936.

- Haam, J.-H.; Kim, B.T.; Kim, E.M.; Kwon, H.; Kang, J.-H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, K.-K.; Rhee, S.Y.; Kim, Y.-H.; Lee, K.Y. Diagnosis of Obesity: 2022 Update of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Obesity by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 32, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.G.; Reider, B.D.; Whiting, A.B.; Prichard, J.R. Sleep Patterns and Predictors of Disturbed Sleep in a Large Population of College Students. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 46, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreidi, M.; Asmar, I. Sleep Hygiene and Academic Achievement among University Students in Palestine. Psychol Educ J. 2021, 58, 4138–43. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, A.F.; Al-Musa, H.; Al-Amri, H.; Al-Qahtani, A.; Al-Shahrani, M.; Al-Qahtani, M. Sleep Patterns and Predictors of Poor Sleep Quality among Medical Students in King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia. Malays. J. Med Sci. 2016, 23, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershner, S.; Chervin, R. Causes and consequences of sleepiness among college students. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2014, 6, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, Y.; Doi, S.A.; Najman, J.M.; Al Mamun, A. Exploring Gender Difference in Sleep Quality of Young Adults: Findings from a Large Population Study. Clin. Med. Res. 2016, 14, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galland, B.C.; Gray, A.R.; Penno, J.; Smith, C.; Lobb, C.; Taylor, R.W. Gender differences in sleep hygiene practices and sleep quality in New Zealand adolescents aged 15 to 17 years. Sleep Health 2017, 3, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Arbués, E.; Granada-López, J.-M.; Martínez-Abadía, B.; Echániz-Serrano, E.; Antón-Solanas, I.; Jerue, B.A. The Association between Diet and Sleep Quality among Spanish University Students. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallampalli, M.P.; Carter, C.L. Exploring Sex and Gender Differences in Sleep Health: A Society for Women’s Health Research Report. J. Women’s Health 2014, 23, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispim, C.A.; Zimberg, I.Z.; Dos Reis, B.G.; Diniz, R.M.; Tufik, S.; De Mello, M.T. Relationship between Food Intake and Sleep Pattern in Healthy Individuals. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2011, 07, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahara, Y.; Makino, S.; Suiko, T.; Nagamori, Y.; Iwai, T.; Aono, M.; Shibata, S. Association between Irregular Meal Timing and the Mental Health of Japanese Workers. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.F.; Thorsteinsson, E.B.; Smithson, M.; Birmingham, C.L.; Aljarallah, H.; Nolan, C. Can body temperature dysregulation explain the co-occurrence between overweight/obesity, sleep impairment, late-night eating, and a sedentary lifestyle? Eat. Weight. Disord. 2017, 22, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Machida, A.; Watanabe, Y.; Shiba, M.; Tominaga, K.; Watanabe, T.; Oshitani, N.; Higuchi, K.; Arakawa, T. Association Between Dinner-to-Bed Time and Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 100, 2633–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hou, Z.-K.; Huang, Z.-B.; Chen, X.-L.; Liu, F.-B. Dietary and Lifestyle Factors Related to Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2021, 17, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahara, Y.; Shibata, S. Chronobiology and nutrition. Neuroscience 2013, 253, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; A DeRoo, L.; Sandler, D.P. Eating patterns and nutritional characteristics associated with sleep duration. Public Health Nutr 2011, 14, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binks, H.; Vincent, G.E.; Gupta, C.; Irwin, C.; Khalesi, S. Effects of Diet on Sleep: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, C.A.; Leidy, H.J.; Gwin, J.A. Indices of Sleep Health Are Associated With Timing and Duration of Eating in Young Adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 124, 1051–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, H.; Asher, G. Crosstalk between metabolism and circadian clocks. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Skipping Breakfast and Its Association with Health Risk Behaviour and Mental Health Among University Students in 28 Countries. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2020, 13, 2889–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwin, J.A.; Leidy, H.J. Breakfast Consumption Augments Appetite, Eating Behavior, and Exploratory Markers of Sleep Quality Compared with Skipping Breakfast in Healthy Young Adults. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2018, 2, nzy074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ak, M. Skipping Breakfast Everyday Keeps Well-being Away. J. Food Sci. Nutr. Res. 2018, 1, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.; Nayak, V.K.R. Effect of skipping breakfast on cognition and learning in young adults. Biomedicine 2022, 42, 1285–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirofumi, M.; Hasebe, H.; Ishihara, K.; Suga, Y. Changes in Subjective Questionnaires of Sleep Quality and Mood States When Breakfast Skippers Consistently Eat Breakfast in Japanese Office Worker. JFN 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzani, A.; Ricotti, R.; Caputo, M.; Solito, A.; Archero, F.; Bellone, S.; Prodam, F. A Systematic Review of the Association of Skipping Breakfast with Weight and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Children and Adolescents. What Should We Better Investigate in the Future? Nutrients 2019, 11, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.I.; Paul, T.; Al Banna, H.; Hamiduzzaman, M.; Tengan, C.; Kissi-Abrokwah, B.; Tetteh, J.K.; Hossain, F.; Islam, S.; Brazendale, K. Skipping breakfast and its association with sociodemographic characteristics, night eating syndrome, and sleep quality among university students in Bangladesh. BMC Nutr. 2024, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, M. Exploring convenience orientation as a food motivation for college students living in residence halls. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2005, 29, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandner, M.A.; Kripke, D.F.; Naidoo, N.; Langer, R.D. Relationships among dietary nutrients and subjective sleep, objective sleep, and napping in women. Sleep Med. 2010, 11, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, L.F.R.; Pellegrino, P.; Cipolla-Neto, J.; Moreno, C.R.C.; Marqueze, E.C. Timing and Composition of Last Meal before Bedtime Affect Sleep Parameters of Night Workers. Clocks Sleep 2021, 3, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, R.; Matito, S.; Cubero, J.; Paredes, S.D.; Franco, L.; Rivero, M.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Barriga, C. Tryptophan-enriched cereal intake improves nocturnal sleep, melatonin, serotonin, and total antioxidant capacity levels and mood in elderly humans. AGE 2013, 35, 1277–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, G.P.; Mota, M.C.; Crispim, C.A. Eveningness is associated with skipping breakfast and poor nutritional intake in Brazilian undergraduate students. Chronobiol Int. 2018, 35, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, C.; Imano, H.; Muraki, I.; Yamada, K.; Iso, H. The Association of Having a Late Dinner or Bedtime Snack and Skipping Breakfast with Overweight in Japanese Women. J. Obes. 2019, 2019, 2439571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambalis, K.D.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Psarra, G.; Sidossis, L.S. Insufficient Sleep Duration Is Associated With Dietary Habits, Screen Time, and Obesity in Children. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2018, 14, 1689–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markwald, R.R.; Melanson, E.L.; Smith, M.R.; Higgins, J.; Perreault, L.; Eckel, R.H.; Wright, K.P. Impact of insufficient sleep on total daily energy expenditure, food intake, and weight gain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 5695–5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panda, S. Circadian physiology of metabolism. Science 2016, 354, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gill, S.; Panda, S. A Smartphone App Reveals Erratic Diurnal Eating Patterns in Humans that Can Be Modulated for Health Benefits. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatori, M.; Vollmers, C.; Zarrinpar, A.; DiTacchio, L.; Bushong, E.A.; Gill, S.; Leblanc, M.; Chaix, A.; Joens, M.; Fitzpatrick, J.A.; et al. Time-Restricted Feeding without Reducing Caloric Intake Prevents Metabolic Diseases in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Onge, M.-P.; Mikic, A.; E Pietrolungo, C. Effects of Diet on Sleep Quality. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2016, 7, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Characteristics |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Sex Male Female |

120 265 |

31.2 68.8 |

|

Age group 18-24 25-30 30-40 |

276 75 34 |

71.7 19.5 8.8 |

|

Year of study 1st and 2nd Year 3rd and 4th year 5th and 6th year |

271 100 14 |

70.4 26.0 3.6 |

|

Academic faculty Faculty of Engineering and Sciences Faculty of Medicine, Health Sciences and Pharmacy Faculty of Business, Cultural Sciences, Humanities, Law, Music and Visual Arts |

86 265 34 |

19.5 68.6 11.9 |

|

Academic level Bachelor Master PhD |

270 60 55 |

70.1 15.6 14.3 |

|

Marital status Single Married Other |

317 16 52 |

82.3 4.2 13.5 |

|

Residential setting Dormitory Apartment |

78 307 |

20.3 79.7 |

|

Smoking status Smoker Non-smoker |

53 332 |

13.8 86.2 |

|

Alcohol consumption Irregular alcohol drinker Regular alcohol drinker |

174 211 |

45.2 54.8 |

|

Coffee consumption Irregular coffee drinker Regular coffee drinker |

190 195 |

49.4 50.6 |

|

Physical activity Irregular physical activity exerciser Regular physical activity exerciser |

232 153 |

60.3 39.7 |

|

Stress level Normal Mild Moderate Severe |

78 71 137 99 |

20.3 18.4 35.6 25.7 |

|

Napping frequency Do not nap Once a day More than once |

90 284 11 |

23.3 73.8 2.9 |

|

Nationality European and Americans Middle Eastern & North African Sub-Saharan African Central, Eastern and South Asia |

110 134 52 89 |

28.6 34.8 13.5 23.1 |

|

BMI (kg/m2) Underweight Normal weight Overweight & Obese class 1,2, and 3 |

37 232 116 |

9.6 60.3 30.1 |

|

Global sleep quality (PSQI) Poor sleep quality Good sleep quality |

199 186 |

51.7 48.3 |

| Sleep behaviors |

Male (n=120) n (%) |

Female (n= 265) n (%) |

Total (n=385) n (%) |

X2 | p-value | |

|

Subjective sleep quality Adequate subjective sleep quality 1 Inadequate subjective sleep quality 2 |

88 (73.3) 32 (26.7) |

192 (72.5) 73 (27.5) |

280 (72.7) 105 (27.3) |

0.32 |

0.857 |

|

|

Sleep latency Adequate sleep latency 1 Inadequate sleep latency2 |

79 (65.8) 41 (34.2) |

169 (63.8) 96 (36.2) |

248 (64.4) 137 (35.6) |

0.153 |

0.696 |

|

|

Sleep Duration Adequate sleep latency 1 Inadequate sleep latency 2 |

83 (69.2) 37 (30.8) |

176 (66.4) 89 (33.6) |

259 (67.3) 126 (32.7) |

0.284 |

0.594 |

|

|

Sleep efficiency Adequate sleep efficiency1 Inadequate sleep efficiency2 |

87 (72.5) 33 (27.5) |

223 (84.2) 42 (15.8) |

310 (80.5) 75 (19.5) |

7.148 |

0.008 |

|

|

Sleep disturbance Adequate sleep disturbance1 Inadequate sleep disturbance2 |

106 (88.3) 14 (11.7) |

224 (84.5) 41 (15.5) |

330 (85.7) 55 (14.3) |

0.977 |

0.323 |

|

|

Use of Sleep Medication Adequate use of sleep Medication 1 Inadequate use of sleep Medication 2 |

113 (94.2) 7 (5.8) |

237 (89.4) 28 (10.6) |

350 (90.9) 35 (9.1) |

2.239 |

0.135 |

|

|

Daytime dysfunction Adequate daytime dysfunction1 Inadequate daytime dysfunction2 |

110 (91.7) 10 (8.3) |

191 (72.1) 74 (27.9) |

301 (78.2) 84 (21.8) |

18.585 |

< 0.001* |

|

|

Global PSQI Score Global score ≤5 (good overall sleep quality)3 Global score >5 (poor overall sleep quality)4 |

66 (55.0) 54 (45.0) |

120 (45.3) 145 (54.7) |

186 (48.3) 199 (51.7) |

3.123 |

0.077 |

|

|

Eating habits |

Overall sleep quality | Subjective sleep quality |

Sleep latency |

Sleep duration |

Sleep efficiency |

Sleep disturbances |

Use sleep medication |

Daytime dysfunction |

| Skipping breakfast | 1.24 (0.83-1.86) | 1.46 (0.93-2.30) | 1.53 (1.00-2.33) | 1.47 (0.96- 2.25) |

1.33 (0.80-2.21) | 1.67 (0.94-2.96) | 3.12 (1.48-6.57) | 1.67 (1.03-2.72) |

| Late-night snacking | 1.59 (1.06-2.38) | 1.58 (1.00-2.50) | 1.54 (1.00-2.35) | 1.35 (0.88- 2.07) | 2.10 (1.23- 3.58) | 1.61 (0.89-2.90) | 0.79 (0.40-1.59) | 1.53 (0.93-2.51) |

| Replacing meals with snacks | 3.00 (1.97-4.55) | 2.07 (1.31-3.26) | 2.64 (1.72-4.06) |

2.50 (1.61- 3.87) |

2.17 (1.29-3.63) | 1.63 (0.92-2.89) | 4.50 (1.99-10.19) | 2.15 (1.31-3.52) |

| Eating heavy evening meals | 2.10 (1.39-3.15) | 1.65 (1.04-2.61) | 1.20 (0.79-1.83) | 0.75 (0.49- 1.15) |

2.23 (1.30- 3.83) |

1.03 (0.58-1.82) | 3.15 (1.39-7.13) | 1.42 (0.87-2.32) |

| Irregular mealtime | 1.00 (0.55-1.78) | 2.68 (1.17-6.15) | 2.59 (1.26-5.34) | 1.54 (0.79- 3.00) |

1.02 (0.49- 2.14) |

1.66 (0.63-4.38) | 1.74 (0.51-5.89) | 1.39 (0.65-2.98) |

| Short Meal-to-Bedtime Interval (<3h) | 2.38 (1.58-3.61) | 2.50 (1.58-3.96) | 2.02 (1.32-3.08) |

1.61 (1.05- 2.48) |

1.99 (1.19- 3.31) |

1.67 (0.94-2.96) | 2.07 (1.02-4.21) | 2.14 (1.31-3.50) |

|

. Eating habit |

Odds ratio |

95% CI () |

p-value |

|

Replacing meals with snacks |

2.68 |

(1.47-4.90) |

0.001* |

|

Heavy evening meals |

2.73 |

(1.58-4.73) |

<0.001 |

|

Short Meal-to-Bedtime Interval (<3h) |

2.06 |

(1.17-3.63) |

0.012 |

|

Irregular mealtime |

0.58 |

(0.27-1.26) |

0.168 |

|

Skipping breakfast |

0.67 |

(0.39-1.15) |

0.144 |

| Late-night snacking |

0.82 |

(0.44-1.51) | 0.517 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).