Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

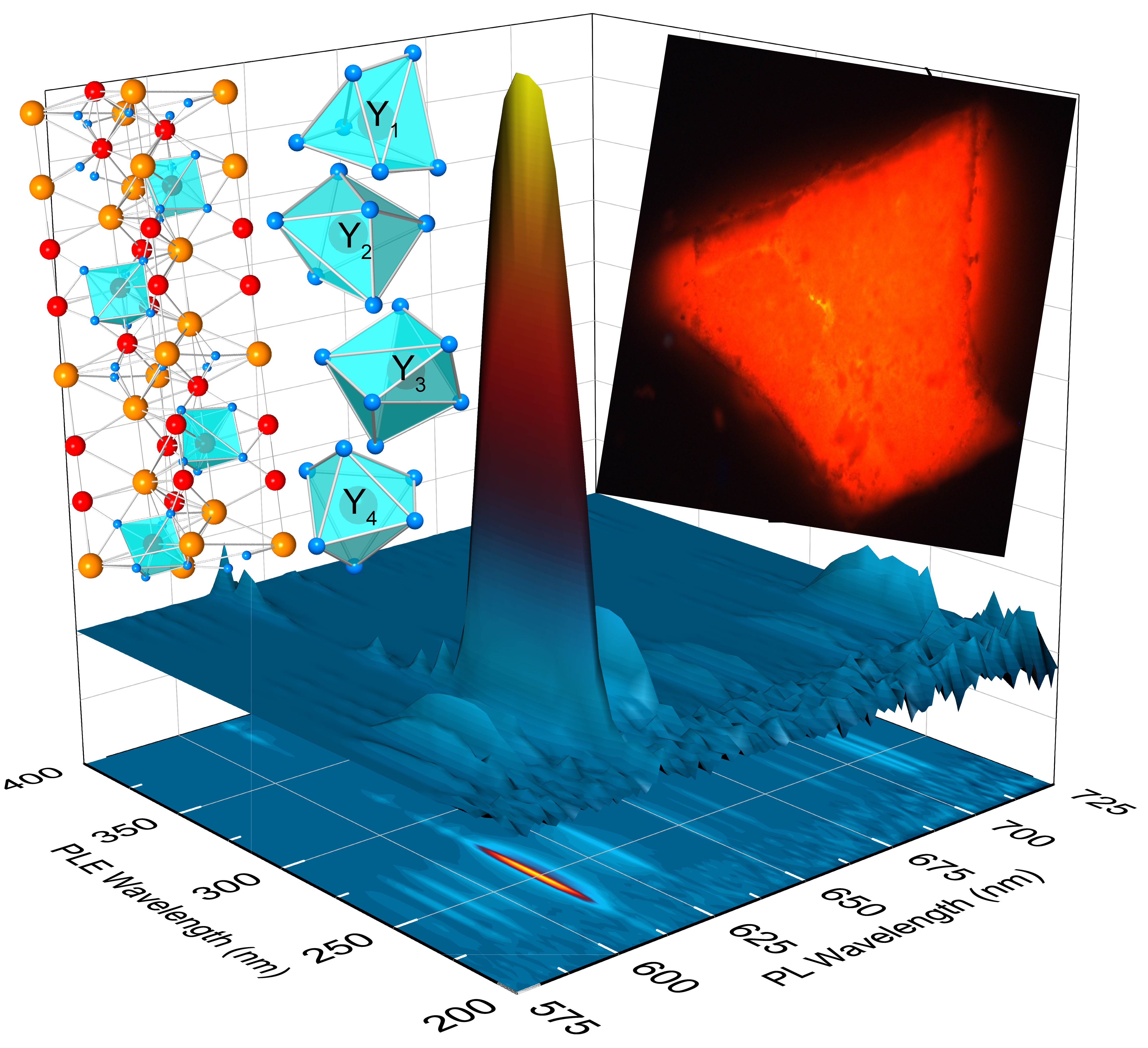

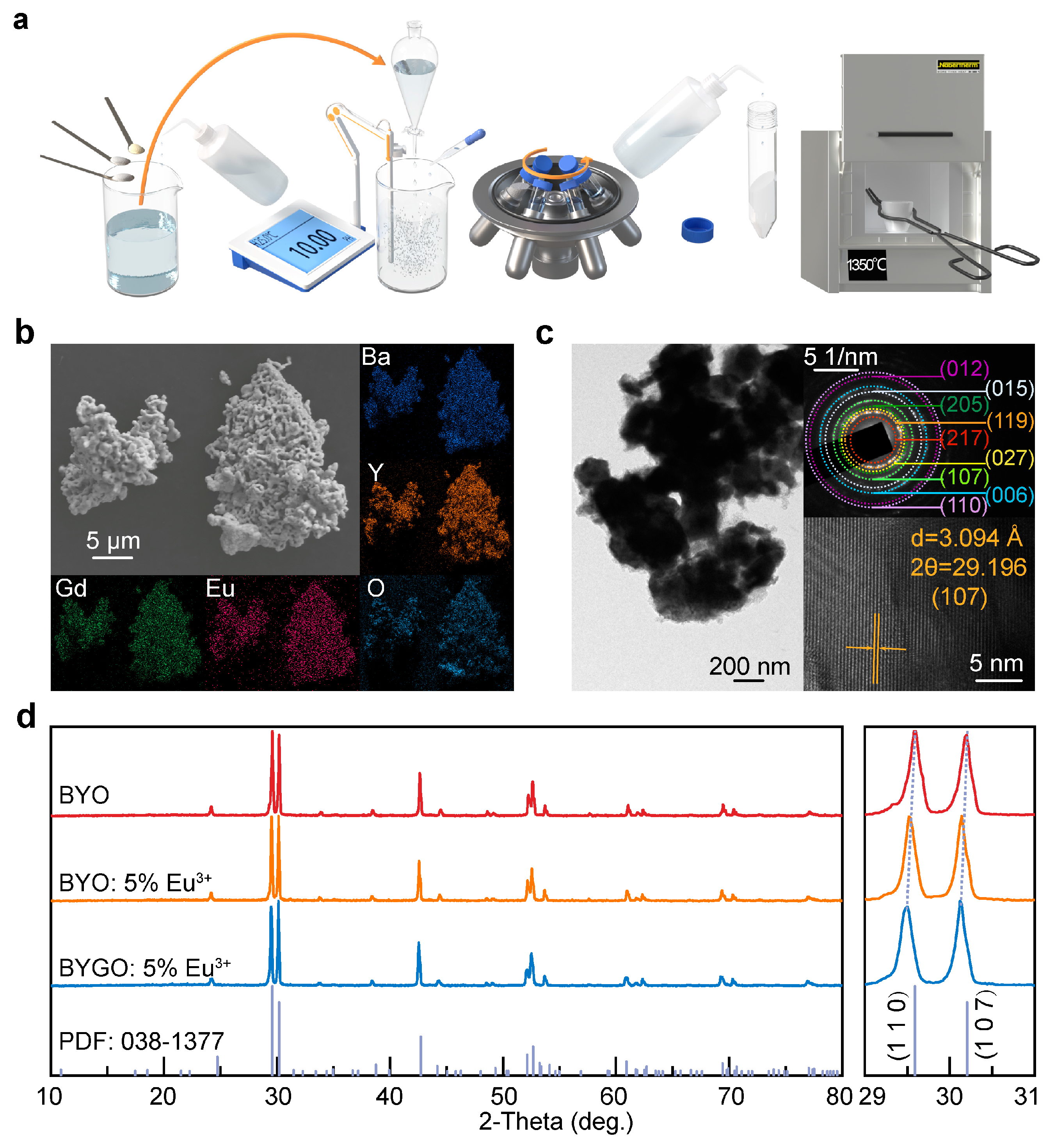

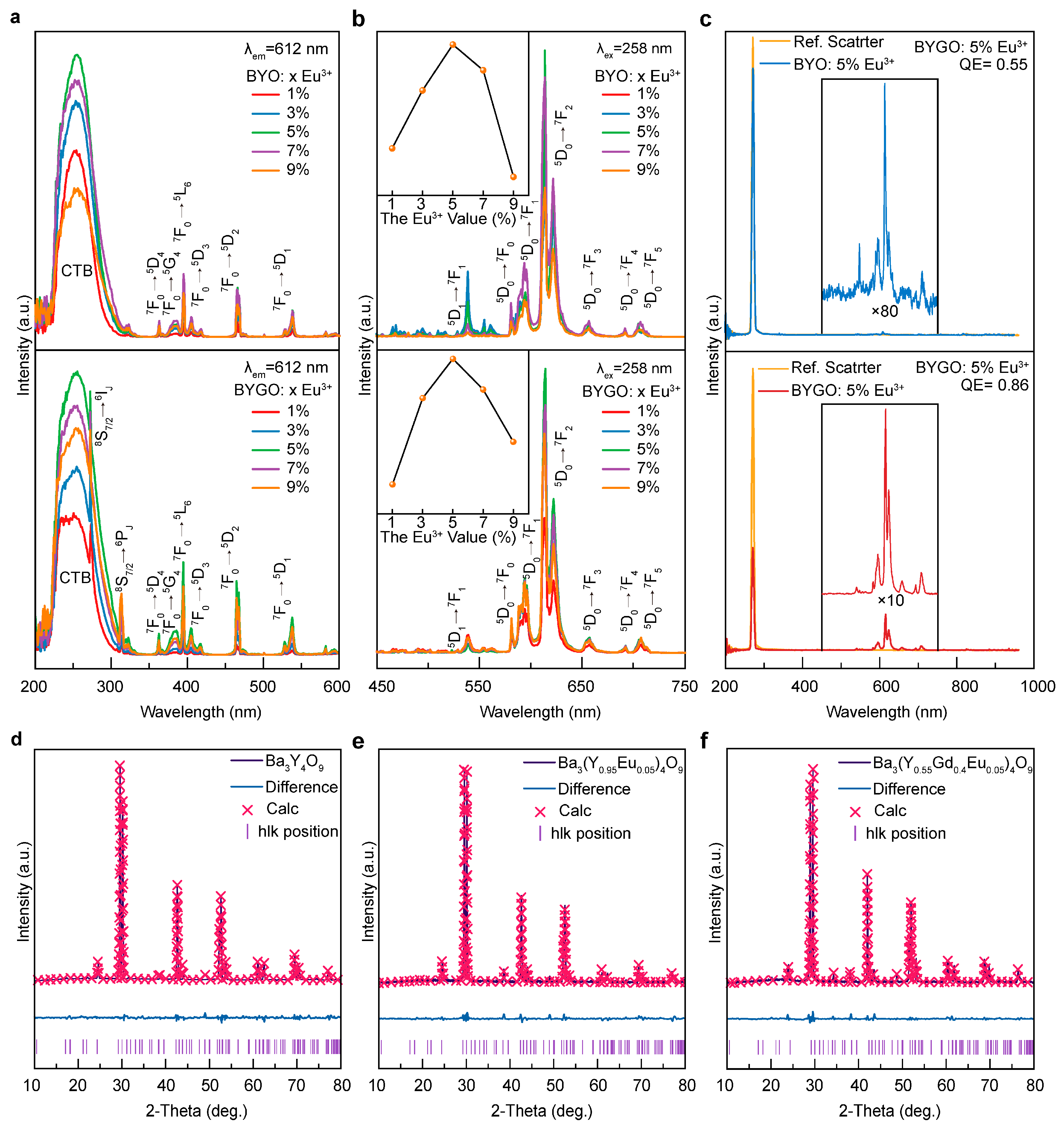

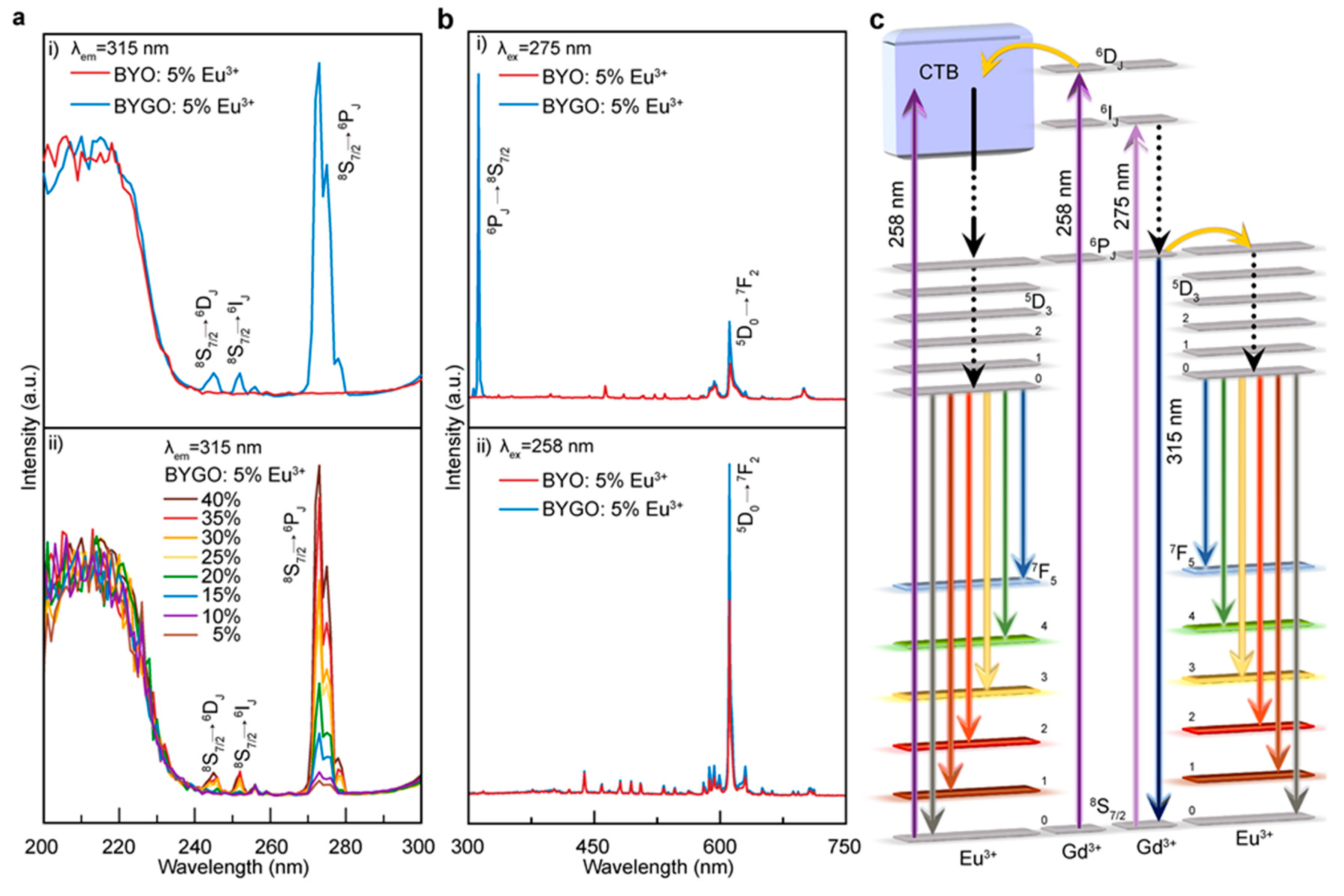

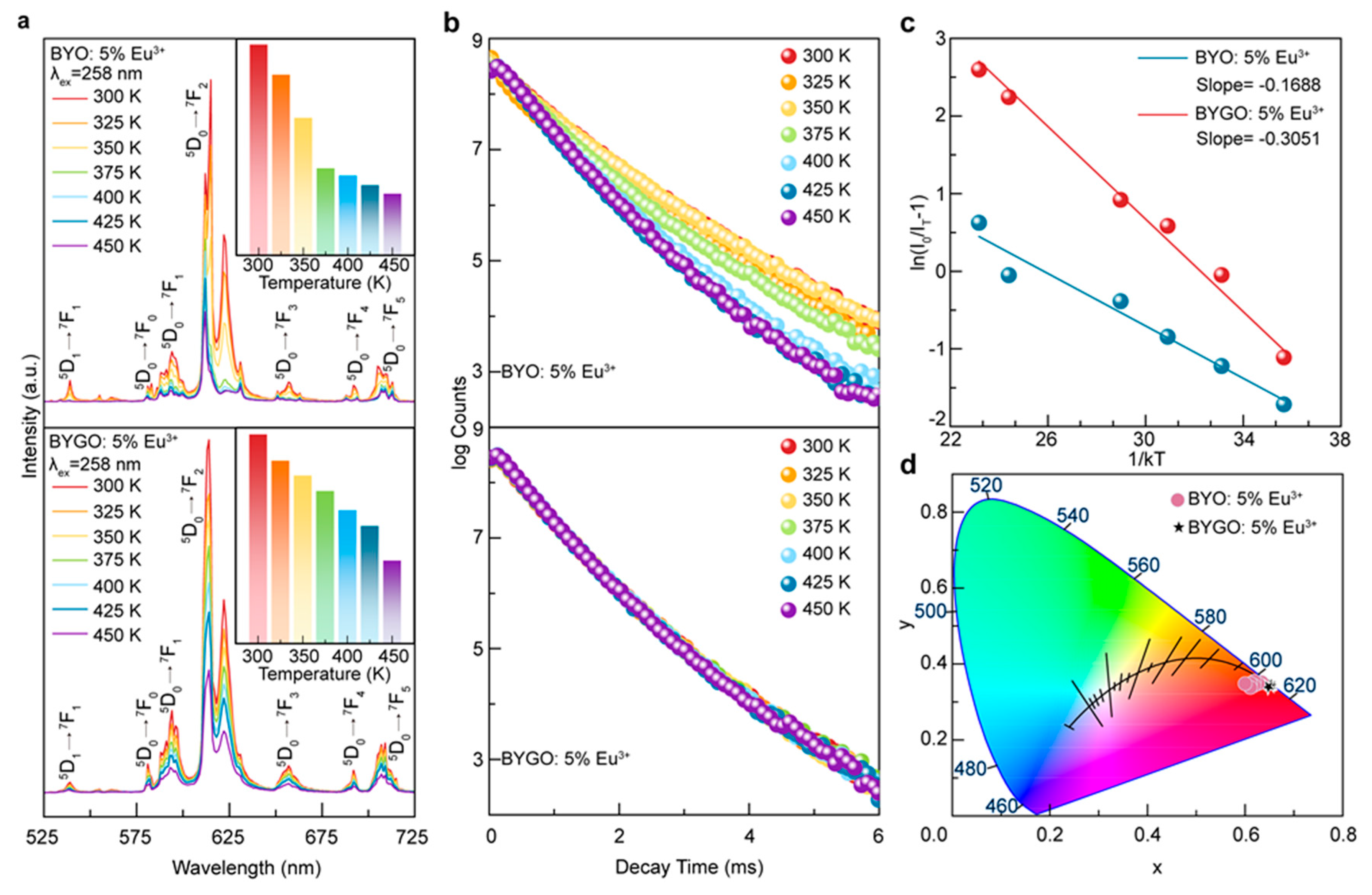

The co-precipitation method was successfully used to synthesize BYGO: Eu3+ phosphors with high Gd3+ doping, resulting in significantly enhanced thermal stability and luminescence performance. Structural analyses confirm that Gd3+ and Eu3+ ions substitute Y3+ in the lattice, causing lattice expansion and improving crystal asymmetry, which enhances Eu3+ emission. The incorporation of Gd3+ creates efficient energy transfer pathways to Eu3+ while suppressing non-radiative relaxation, leading to stable fluorescence lifetimes even at elevated temperatures. With a thermal activation energy of ~0.3051 eV, the BYGO: Eu3+ system exhibits superior resistance to thermal quenching compared to BYO: Eu3+ and many conventional red phosphors. Furthermore, the reduced color temperature and stable emission spectra across a wide temperature range highlight its potential for advanced lighting and display technologies in high-temperature environments.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| W-LEDs | White light-emitting diodes |

| BYO | Ba3Y4O9 |

| BYGO | Ba3(Y0.6Gd0.4)4O9 |

| CCT | Correlated color temperature |

| CTB | Charge transfer band |

| PL | Photoluminescence |

| PLE | photoluminescence excitation |

| QE | Quantum efficiency |

| FE-SEM | Field emission scanning electron microscope |

| EDS | energy-dispersive spectroscopy |

| FE-TEM | Field emission transmission electron microscopy |

| SAED | Selected area electron diffraction |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| Ea | Activation energy |

References

- Lin, S. S.; Lin, H.; Huang, Q. M.; Yang, H. Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, P. F.; Sui, P.; Xu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Y. S., Highly crystalline Y3Al5O12: Ce3+ phosphor in glass film: A new composite color converter for next generation high brightness laser driven lightings. Laser Photonics Rev. 2022, 16, 2200523. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H. Y.; Li, H. M.; Jiang, L. H.; Pang, R.; Zhang, S.; Li, D.; Liu, G. Y.; Li, C. Y.; Feng, J.; Zhang, H. J., Design of a mixed-anionic-ligand system for a blue-light-excited orange-yellow emission phosphor Ba1.31Sr3.69(BO3)3Cl: Eu2+. J. Mater. Chem. C, 2020, 8, 3040-3050. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J. E.; Park, S.; Park, Y.; Ryu, S. W.; Hwang, K.; Jang, H. W., Technological breakthroughs in chip fabrication, transfer, and color conversion for high-performance micro-LED displays. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2204947. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Min, K.; Park, Y.; Cho, K. S.; Jeon, H., Photonic crystal phosphors integrated on a blue LED chip for efficient white light generation. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1703506. [CrossRef]

- Bispo-Jr, A. G.; Saraiva, L. F.; Lima, S. A.; Pires, A. M.; Davolos, M. R., Recent prospects on phosphor-converted LEDs for lighting, displays, phototherapy, and indoor farming. J. Lumin. 2021, 237, 118167. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, C.; Qiao, X.; Fan, X., Simultaneous enhancement of red luminescence and thermal stability of a novel red phosphor: A Li+-Eu3+ co-occupied site strategy in BaAl2Ge2O8 lattices. J. Rare Earth.2024, 42, 1846-1854. [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Tang, J.; Li, W.; Luo, L.; Runowski, M., Manipulating concentration quenching and thermal stability of Eu3+-activated NaYbF4 nanoparticles via phase transition strategy toward diversified applications. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 26, 101013. [CrossRef]

- Jahanbazi, F.; Mao, Y. B., Recent advances on metal oxide-based luminescence thermometry. J. Mater. Chem. C, 2021, 9, 16410-16439. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhu, H.; Huang, X.; She, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Li, W.; Xia, M., Anti-thermal-quenching, color-tunable and ultra-narrow-band cyan green-emitting phosphor for w-LEDs with enhanced color rendering. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 134079. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; Yang, S., Emerging near-unity internal quantum efficiency and color purity from red-emitting phosphors for warm white LED with enhanced color rendition. J. Alloy. Compd. 2022, 899, 163209. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, H.; Lv, Z.; Guan, X.; Yu, J.; Ma, S.; Xia, L.; Dong, X., Design strategies of rare-earth luminescent complexes with zero thermal quenching protected by the wire-in-tube structure and the construction of a W-WLED with highly stable illumination and colour reproduction. J. Mater. Chem. C, 2024, 12, 17278-17288. [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Xie, Y.; Chen, S.; Luo, J.; Li, S.; Wang, T.; Zhao, S.; Wang, H.; Deng, B.; Yu, R., Enhanced local symmetry achieved zero-thermal-quenching luminescence characteristic in the Ca2InSbO6: Sm3+ phosphors for w-LEDs. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 410, 128396. [CrossRef]

- Hooda, A.; Khatkar, A.; Boora, P.; Singh, S.; Devi, S.; Khatkar, S.; Taxak, V., Structural, optical and morphological features of combustion derived Ba3Y4O9: Dy3+ nanocrystalline phosphor with white light emission. Optik, 2021, 228, 166176. [CrossRef]

- Hooda, A.; Khatkar, S.; Khatkar, A.; Malik, R.; Kumar, M.; Devi, S.; Taxak, V., Reddish-orange light emission via combustion synthesized Ba3Y4O9: Sm3+ nanocrystalline phosphor upon near ultraviolet excitation. J. Lumin. 2020, 217, 116806. [CrossRef]

- Hooda, A.; Khatkar, S. P.; Devi, S.; Taxak, V. B., Structural and spectroscopic analysis of green glowing down-converted BYO: Er3+ nanophosphors for pc-WLEDs. Ceram, Int, 2021, 47, 25602-25613. [CrossRef]

- Xing, G. C.; Gao, Z. Y.; Tao, M. X.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Y. X.; Dang, P. P.; Li, G. G.; Lin, J., Novel orange-yellow-green color-tunable Bi3+-doped Ba3Y4-wLuwO9 (0 ≤ w ≤ 4) luminescent materials: site migration and photoluminescence control. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 3598-3603. [CrossRef]

- Han, X. Y.; Hu, C. Q.; Wu, J. M.; Wang, S. X.; Ye, Z. M.; Yang, Q. C., Systematical site investigation and temperature sensing in Pr3+-doped M3Re4O9 (M = Sr and Ba; RE = Sc, Y, Lu). Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139159. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Sun, L. L.; Annadurai, G.; Devakumar, B.; Wang, S. Y.; Sun, Q.; Qiao, J. L.; Guo, H.; Li, B.; Huang, X. Y., Synthesis and photoluminescence characteristics of high color purity Ba3Y4O9: Eu3+ red-emitting phosphors with excellent thermal stability for warm W-LED application. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 32111-32118. [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Lian, H. Z.; Shang, M. M.; Lin, J., A novel greenish yellow-orange red Ba3Y4O9: Bi3+, Eu3+ phosphor with efficient energy transfer for UV-LEDs. Dalton T. 2015, 44, 20542-20550. [CrossRef]

- Zinchenko, V.; Volchak, G.; Chivireva, N.; Doga, P.; Bobitski, Y.; Ieriomin, O.; Smola, S.; Babenko, A.; Sznajder, M., Solidified salt melts of the NaCl-KCl-CeF3-EuF3 system as promising luminescent materials. Materials, 2024, 17, (22). [CrossRef]

- Nikiforov, I. V.; Spassky, D. A.; Krutyak, N. R.; Shendrik, R. Y.; Zhukovskaya, E. S.; Aksenov, S. M.; Deyneko, D. V., Co-doping effect of Mn2+ and Eu3+ on luminescence in strontiowhitlockite phosphors. Molecules, 2024, 29, 124. [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, S. S.; Nielsen, V. R. M.; Sorensen, T. J., Contrasting impact of coordination polyhedra and site symmetry on the electronic energy levels in nine-coordinated Eu3+ and Sm3+ crystals structures determined from single crystal luminescence spectra. Dalton T. 2024, 53, 10079-10092. [CrossRef]

- Ichiba, K.; Kato, T.; Watanabe, K.; Takebuchi, Y.; Nakauchi, D.; Kawaguchi, N.; Yanagida, T., Evaluation of photoluminescence and scintillation properties of Eu-doped YVO4 single crystals synthesized by optical floating zone method. J. Lumin. 2024, 266, 120327. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Q.; Guo, H. J.; Shi, Q. F.; Qiao, J. W.; Cui, C. E.; Huang, P.; Wang, L., Single-band ratiometric thermometry strategy based on the completely reversed thermal excitation of O2- → Eu3+ CTB edge and Eu3+ 4f → 4f transition. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 16304-16312. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. H.; Chen, C. T.; Guo, S. Q.; Zhang, J. Y.; Liu, W. R., Luminescence and theoretical calculations of novel red-emitting NaYPO4F: Eu3+ phosphor for LED applications. J. Alloy. Compd. 2017, 712, 225-232. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Zhou, X. J.; Li, L.; Ling, F. L.; Li, Y. H.; Li, J. F.; Yang, H. M., Comparative study on the anomalous intense 5D0→7F4 emission in Eu3+ doped Sr2MNbO6 (M=Ga, In, Gd) phosphors. J. Lumin. 2024, 267, 120370. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Niu, Y. F.; Liu, C. L.; Jiang, H. M.; Li, J. P.; Wu, J. Z.; Huang, S. P.; Zhang, H. Z.; Zhu, J., Unraveling the Remarkable Influence of Square Antiprism Geometry on Highly Efficient Far-Red Emission of Eu<SUP>3+</SUP> in Borotellurate Phosphors for Versatile Utilizations. Laser Photonics Rev. 2024, 12, 2400843. [CrossRef]

- Mancic, L.; Lojpur, V.; Marinkovic, B. A.; Dramicanin, M. D.; Milosevic, O., Hydrothermal synthesis of nanostructured Y2O3 and (Y0.7Gd0.25)2O3 based phosphors. OPTICAL MATERIALS 2013, 35, (10), 1817-1823. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. Y.; Liu, B.; Li, J. K.; Liu, Z. M., Synthesis and luminescent properties of Ba3Y3.88Gd0.12O9: Eu3+ phosphors with enhanced red emission. J. Rare Earth. 2022, 40, 534-540. [CrossRef]

- Qin, K. L.; Sun, J. B.; Zhu, X. D.; Cao, F. B.; Liu, W. M.; Shen, X. M.; Wu, X. R.; Wu, Z. J., Eu3+ doped high-aluminum cast residue prepared EuCaAl3O7/Ca2Al2SiO7 luminescent material with 5D0→7F2/5D0→7F4 double red intense emission. J. Lumin. 2021, 233, 117920. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C. C.; Chen, K. B.; Lee, C. S.; Chen, T. M.; Cheng, B. M., Synthesis and VUV photoluminescence characterization of (Y,Gd)(V,P)O4: Eu3+ as a potential red-emitting PDP phosphor. CHEMISTRY OF MATERIALS 2007, 19, 3278-3285. [CrossRef]

- Khan, N. Z.; Khan, S. A.; Muhammad, N.; Chen, W. L.; Ahmed, J.; Padhiar, M. A.; Chen, M.; Runowski, M.; Alshehri, S. M.; Zhang, B. H.; Pan, S. S.; Zheng, R. K., Tunable single-phase white light emission from complex perovskite Sr3CaNb2O9: Dy3+/Eu3+ phosphors. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, 2401938. [CrossRef]

- Pawlik, N.; Szpikowska-Sroka, B.; Goryczka, T.; Pisarski, W. A., Studies of energy transfer process between Gd3+ and Eu3+ ions in oxyfluoride sol-gel materials. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 41041-41053. [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.; Michalska-Domanska, M.; Dubey, V.; Ram, T.; Kaur, J.; Dubey, N.; Aman, S.; Manners, O.; Saji, J., Investigation of spectroscopic parameters and trap parameters of Eu3+-activated Y2SiO5 phosphors for display and dosimetry applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 108. [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Jiang, Y.; An, J.; Huang, X.; Elgarhy, A. H.; Cao, H.; Liu, G., Novel Fe/Ca oxide co-embedded coconut shell biochar for phosphorus recovery from agricultural return flows. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 27204-27214. [CrossRef]

- Martins, F. C. B.; Firmino, E.; Oliveira, L. S.; Dantas, N. O.; Silva, A. C. A.; Barbosa, H. P.; Rezende, T. K. L.; Góes, M. S.; dos Santos, M. A. C.; de Oliveira, L. F. C.; Ferrari, J. L., Development of Y2O3:Eu3+ materials doped with variable Gd3+ content and characterization of their photoluminescence properties under UV excitation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 277, 125498. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, X. B.; Guo, J. K.; Wang, L. X.; Song, J. K.; Zhang, Q. T., Second-order John-Teller distortion in the thermally stable Li(La, Gd) MgWO6:Eu3+ phosphor with high quantum efficiency. Dyes Pigments 2019, 160, 165-171.. [CrossRef]

- Bhagyalekshmi, G. L.; Ganesanpotti, S., Comprehension of the photoinduced charge transfer assisted energy transfer in Gd3+-based host sensitized tellurate phosphors for thermal sensing and anticounterfeiting labels. Dalton T. 2024, 53, 8229-8242. [CrossRef]

- Bazzi, R.; Flores, M. A.; Louis, C.; Lebbou, K.; Zhang, W.; Dujardin, C.; Roux, S.; Mercier, B.; Ledoux, G.; Bernstein, E.; Perriat, P.; Tillement, O., Synthesis and properties of europium-based phosphors on the manometer scale: Eu2O3, Gd2O3: Eu, and Y2O3: Eu. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2004, 273, 191-197. [CrossRef]

- Brites, C. D. S.; Balabhadra, S.; Carlos, L. D., Lanthanide-based thermometers: At the cutting-edge of luminescence thermometry. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2019, 7, 1801239. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J. W.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, X. Q.; Chen, W. B.; Gautier, R.; Xia, Z. G., Near-infrared light-emitting diodes utilizing a europium-activated calcium oxide phosphor with external quantum efficiency of up to 54.7%. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2201887. [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, Y.; Tehrani, A. M.; Oliynyk, A. O.; Duke, A. C.; Brgoch, J., Identifying an efficient, thermally robust inorganic phosphor host via machine learning. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4377. [CrossRef]

- Ye, W. G.; Zhao, C.; Shen, X. F.; Ma, C. Y.; Deng, Z. H.; Li, Y. B.; Wang, Y. Z.; Zuo, C. D.; Wen, Z. C.; Li, Y. K.; Yuan, X. Y.; Wang, C.; Cao, Y. G., High quantum yield Gd4.67Si3O13: Eu3+ red-emitting phosphor for tunable white light-emitting devices driven by UV or blue LED. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3, 1403-1412. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, W. T.; Wang, X. M.; Zhang, J. Y.; Gao, X.; Du, H. Y., Structure and luminescence investigation of Gd3+-sensitized perovskite CaLa4Ti4O15: Eu3+: A novel red-emitting phosphor for high-performance white light-emitting diodes and plants lighting. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 608, 3204-3217. [CrossRef]

- Dang, P. P.; Li, G. G.; Yun, X. H.; Zhang, Q. Q.; Liu, D. J.; Lian, H. Z.; Shang, M. M.; Lin, J., Thermally stable and highly efficient red-emitting Eu3+-doped Cs3GdGe3O9 phosphors for WLEDs: non-concentration quenching and negative thermal expansion. Light-science & Applications, 2021, 10, 29. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).