1. Introduction

Mongolia is a low-forest cover country of 7.9% and only 67.5% of this is closed forest.

Pinus sylvestris L is one of the most economically important timber species even though the distribution is limited in Mongolia to the sub-taiga zone [

1]. The southern border of

P. sylvestris distribution dips into northern Mongolia with the main areas in the Khentii mountain range, along the ridge of Khantai-Buren-Buteeliin in the northwest to Orkhon-Selenge catchment, and the south in the Onon-Balj-Barkhiin river basins, and to the northeast along Bayan-Uul-Ereen davaa area [

2]. Reforestation activity in Mongolia started in the 1970s and resulted in a National Forest Policy that considered reforestation and tree planting as key objectives. Restoration and reforestation activities encounter numerous challenges caused by both biotic and abiotic factors. Soil moisture is one of Mongolia's most limiting environmental factors for tree growth and survival. Thus, the selection of appropriate seed sources that have advanced drought tolerance and growth performances could be the best option to promote the quality of planting stocks, obtain high survival of seedlings, and increase growth and productivity in large-scale rehabilitation and reforestation. This unique pine forest ecosystem plays an important role in environmental sustainability including biodiversity conservation, soil protection from erosion, wildlife habitat, and carbon sequestration [

3]. The restoration project of the Scots pine forest of Tujiin nars was implemented between 2003 and 2005 with the financial support of the Yuhan Kimberly (YK) company as an example of forest restoration and afforestation in the forest-steppe region of Mongolia. Over the last two decades, more than 21,000 ha of Scots pine plantations were established on clear-cuts and burnt forest areas using native tree species in the region [

4]. The success of planting and reforestation depends upon many factors, including seed and seedling quality, site-species compatibility, and appropriate silvicultural practices [

5].

Therefore, plantation forest need often maintenance such as a thinning, which is significantly influences forest soil, affecting root density, microbial communities, organic matter turnover, and nutrient budgets, which affects tree growth, understory vegetation composition, and the whole forest ecosystem [

6,

7,

8]. Tree planting can change soil environments by affecting soil temperature and moisture, bulk density, and soil organic carbon [

9,

10,

11,

12]. We evaluated the understory vegetation and soil parameters associated with 18 to 20-year-old plantation forests that were in 2016 and 2017 to offer answers to this topic. (1) to assess the environmental consequences of new forests on understory vegetation; and (2) to access the changes of soil characteristics under plantation forests. Our findings will aid efforts to enhance the management of current plantations and urge planners to employ Scots pine only at the most appropriate densities and locations in future afforestation.

4. Discussion

The establishment of productive forest plantations is becoming an important silvicultural issue in Mongolia. In the study region, plantations are primarily monocultures, consisting only of Scots pine (P. sylvestris L.). Scots pine is a light-demanding tree species that plays an important role not only in domestic wood industry, but also in forest ecosystem sustainability in Mongolia. Several open questions regarding Scots pine in Mongolia include whether to plant or rely on natural regeneration; which regeneration method produces the greatest understory diversity; the optimal spacing for planting; and the effect of planting tree on the growth and development of the over story pine, understory diversity, and soil properties?

Soil water content decreased with increasing tree age, while the thickness of the surface dry layer increased, significantly leading to greater soil drying. In the 4-year-old forests, soil moisture was adequate, and seasonal rainfall could partially compensate for the soil water deficit. However, in 9-year-old forests, water deficit became a serious concern at high tree densities, where seasonal rainfall did not compensate completely offset the soil water deficit at densities greater than 400 trees per hectare (trees ha

−1). Consequently, the soil remained relatively dry at the end of the rainy season, even after more than 640 mm of rainfall. The 15- and 30-year-old forests also experienced significant drought due to their drying effect on the soil. Overall, the trees promoted soil water loss, creating a serious imbalance between the water supply and demand in this desert environment. High-density planting accelerated the deterioration of the water environment (i.e., soil drying) and threatened the future survival of the trees and other plants. Thus, ecological managers must reduce tree planting and test the effectiveness of reducing the density to 333 trees ha

−1 during the young stage [

51]. Natural regeneration in the Tujiin nars Scots pine forests has been impeded by fires and grazing, increasing the emphasis on planting to regenerate these forests. Although this study was not designed to directly compare planting with natural regeneration; we included comparisons of the planted stands to a naturally regenerated stand of approximately the same age to highlight different management effect. On one hand, several studies [

52,

53,

54,

55] have noted the importance of establishing forest plantations with native tree species, which can have highly diverse understory of indigenous species. On the other hand, Hanter [

56] and Hartley [

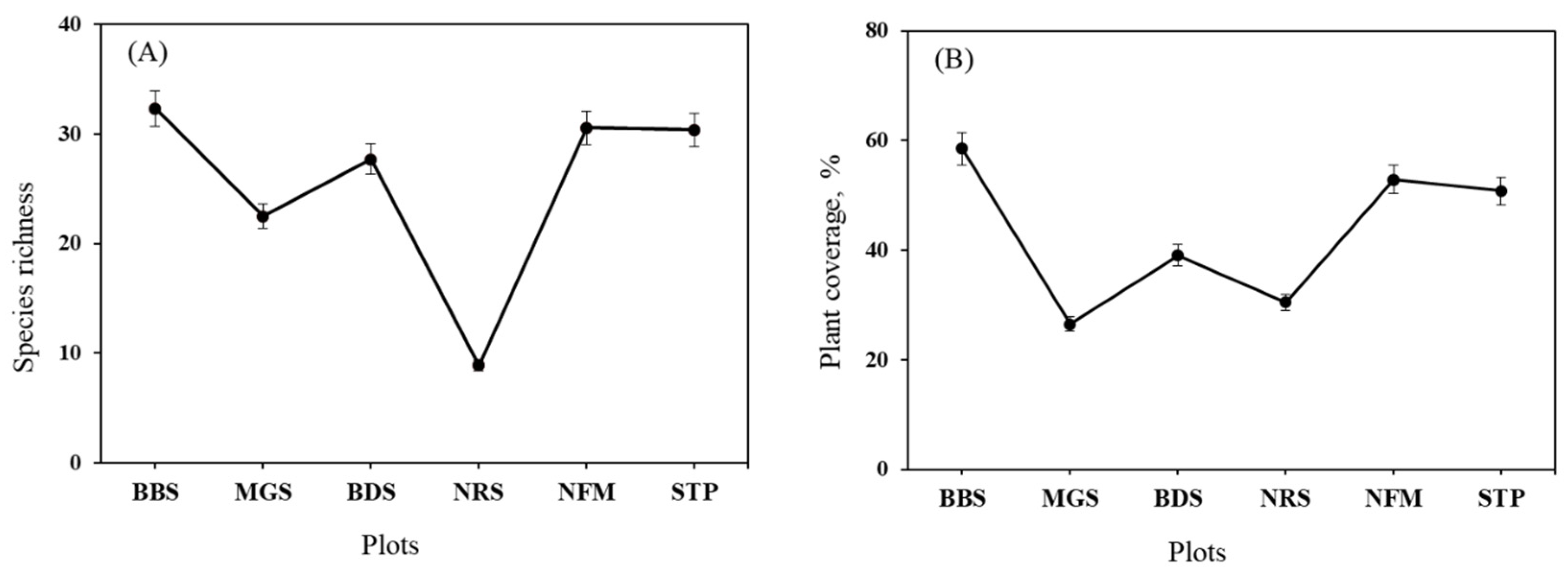

57] stated that plantation forests typically are less favorable as habitat than naturally regenerated stands for a wide range of taxa, particularly in the case in the even-aged, single-species stands. In our case, species richness (30.57-75.18%) and plant coverage (18.4-48.3%) were higher in planted forests than in the naturally regenerated stand (SR-68.16% and PC-48.3%) (

Figure 3). The contrary effects may be due to legacy effects of previous land use [

58,

59]. For example, Hedman et al. [

60] found that understory diversity was greater in pine plantations established after harvesting a forest than on old agricultural fields.

Optimal spacing at planting and during subsequent tending must balance several sometimes-competing factors. Stock ability, a concept of optimal growing space [

61], depends upon species traits and site quality. Additionally, Optimal planting density must consider competing vegetation to ensure that site resources are captured by the target planted species. Managing stand density at lower levels has been proposed as an adaptation to climate change driven increases in aridity, which is an important consideration in Mongolia [

52,

63].

Greater diversity and unique composition in the treatments compared to undisturbed control suggested a link between resource heterogeneity and biodiversity [

65] or legacy effects associated with different treatments changes in understory plant community, which was partly supported by our study. The Shannon index was highly variable among treatments (

Table 7) and generally indicated low species richness, which did not exceed 0.8156 in the BBS.

Open conditions after the removal of previous stands provided an opportunity for non-forest understory species to establish. Changes in species composition and a stable existence of invasive plant species from different ecological groups tend to persist during the initial stage of forest plantation establishment [

66]. Mesophytes and xerophytes were the dominant life forms, which are well adopted to dry climatic conditions and relatively infertile soils. Furthermore, the abundant herbaceous species with high plant coverage from steppe and forest-meadow ecological groups were found not only in STP and NFM, but also in other stands. This high proportion of herbaceous species adapted to steppe and forest-meadow ecosystem within planted forests, and their stable existence in the plantations; indicated a potential risk of replacing the Scots pine ecosystem with steppe ecosystems. As tree crown in size over time, they create shade and more suitable microclimatic conditions for the development of forest and forest-meadow plant. Thus, comparisons of understory composition and biodiversity in plantations with other types of forests heavily depend on plantation age.

Forest management significantly affects forest soils, particular soil organic matter, a key component of sustainability [

67,

68]. Soil is a crucial component in ecosystems, serving as a major storage and source of plant-available nutrients [

8]. Change in the soil properties in our study mainly occurred in the topsoil layers (0 to 20 cm). Significant increases in soil bulk density (1.25±0.11 to 1.46±0.06 g cm

-3), organic carbon (8.85±2.55 to 15.45±4.32 g kg

-1), soil organic carbon stock (8.87±1.34 to 13.39±2.98 Mg ha

-1), available phosphorus (21.17±5.02 to 26.42±5.38 mg kg

-1) and soil moisture (8.6±1.0 to 12.0±2.5%) were observed in plantations compared to NRS and NFM. The results of the assessments showed a slight increase in soil temperature throughout the soil profile and a sharp decrease in the moisture content of the upper soil layer in 2003 plantations.

Restoration objectives include maintaining pH levels between 7.5 and 8.2, enhancing soil organic matter to 30-35%, sustaining electrical conductivity around 0.7-0.8, and demonstrating potential for improvement in all parameters through biological diversity strategies. Additional plots may gain from specific soil enrichment. Furthermore, we propose that a larger sample size be utilized to enhance statistical significance, alongside temporal monitoring to evaluate seasonal fluctuations, examination of additional environmental factors, and a comprehensive analysis of species composition. Future research directions include long-term monitoring of soil-diversity relationships, investigation of species-specific responses to soil conditions, analysis of soil microbial communities, assessment of restoration success using these parameters as indicators, and examination of climate change effects on soil-diversity relationships.

The results indicate that interventions to elevate soil pH, like as liming, in acidic plots like BDS may promote species diversity. Plots with intermediate pH (e.g., NRS, NFM) may require supplementary soil amendments to enhance conditions for biodiversity. Integrate additional soil variables (e.g., soil organic matter, electrical conductivity) into the analysis to enhance comprehension of their collective impact on diversity. Observe alterations in soil characteristics and biodiversity across time to document temporal dynamics. Responses Specific to Species: Examine the responses of specific species to pH and other soil characteristics to determine the primary factors influencing diversity. Soil organic carbon (SOC) levels in plantation forests are higher compared to grasslands and naturally regenerated forests. In low-carbon soils, forest restoration accumulates significantly more carbon than natural regeneration [

70].

Carbon stocks generally decrease with soil depth, as SOC concentrations below 30 cm are less influenced by management practices due to lower carbon inputs and higher decomposition rates in deeper layers. Near the soil surface, SOC concentrations increase non-linearly, driven by carbon inputs from plant residues, roots, and favorable conditions such as optimal temperature and moisture [

71]. Maintaining optimal soil moisture levels is crucial for enhancing carbon sequestration and reducing greenhouse gas emissions [

72].

Drought conditions, which reduce soil moisture, have a significant negative impact on carbon sequestration. Conversely, in some regions, high soil moisture levels promote carbon accumulation. For example, elevated soil moisture in areas like the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, Xinjiang, and Northwest China enhances carbon sink activity, contributing to net ecosystem productivity increases of up to 3.0 g C m² per year [

73]. These findings collectively emphasize the strong connection between soil moisture and SOC dynamics. The results from previous studies align with our findings, which establish a clear relationship between soil moisture levels and carbon dynamics, highlighting the importance of soil moisture in SOC accumulation and loss.

The correlation between soil organic carbon (SOC) in forest plots and carbon sequestration trends demonstrates that SOC functions as a crucial reservoir for atmospheric carbon, especially in tropical wet and moist forest ecosystems [

74]. The density and diversity of trees in these forest plots positively correlate with soil carbon levels, indicating that healthier and more diversified forests can improve carbon sequestration [

75]. Our findings indicate that plantation stands (BBS, MGS, BDS) typically exhibit elevated SOC levels in comparison to natural regeneration stands (NRS) and steppe regions (STP). The detailed BBS exhibits the highest soil organic carbon (SOC) at 14.63±1.78 Mg ha⁻¹, followed by NRS at 10.03±2.23 Mg ha⁻¹. STP exhibits the lowest SOC (3.31±0.64 Mg ha⁻¹), underscoring the restricted carbon storage potential of steppe regions.

This tendency corresponds with Lal's (2004) findings, which highlight that planted trees elevate soil organic carbon levels through augmented organic matter inputs and diminished soil erosion [

76]. SOC functions as a primary reservoir for atmospheric carbon, playing a crucial role in global carbon sequestration initiatives [

74]. Elevated soil organic carbon levels in plantation stands indicate that afforestation and reforestation initiatives are pivotal in alleviating climate change through the augmentation of soil carbon sequestration. The documented reduction in soil organic carbon with increasing soil depth underscores the significance of surface soil layers in carbon sequestration, corroborated by worldwide soil profile investigations [

77]. Plantation stands (e.g., BBS, MGS) likely enhance soil organic carbon (SOC) levels by augmenting litterfall and diminishing competition among trees, as observed by the user. This corresponds with observations that plantation can augment soil organic matter inputs and enhance soil quality indices [

78]. The relationship between soil moisture and SOC dynamics underscores the significance of water availability in carbon sequestration. For instance, BBS, exhibiting elevated soil moisture (SM = 7.65±0.73%), also demonstrates the greatest levels of SOC. This association aligns with research indicating that soil moisture favorably affects SOC buildup by enhancing microbial activity and organic matter breakdown [

78].

The findings endorse the utilization of planted forests as carbon farming zones, especially in degraded environments such as steppes (STP). Policies that advocate for afforestation and reforestation can elevate soil organic carbon levels and aid in achieving carbon sequestration objectives under frameworks such as the Paris Agreement. Plantation and soil moisture management must be incorporated into forest management plans to enhance SOC levels and carbon sequestration. The favourable correlation between soil organic carbon (SOC) and tree diversity emphasizes the necessity of reconciling biodiversity protection with carbon sequestration initiatives. Mixed-species plantations can fulfil both goals. The investigation underscores the essential function of plantation forests in augmenting soil organic carbon levels and facilitating carbon sequestration. The identified trends in the plots offer significant insights for carbon farming and silvicultural management, in accordance with global climate change mitigation strategies. Subsequent study ought to concentrate on refining these approaches to enhance carbon sequestration and biodiversity preservation.

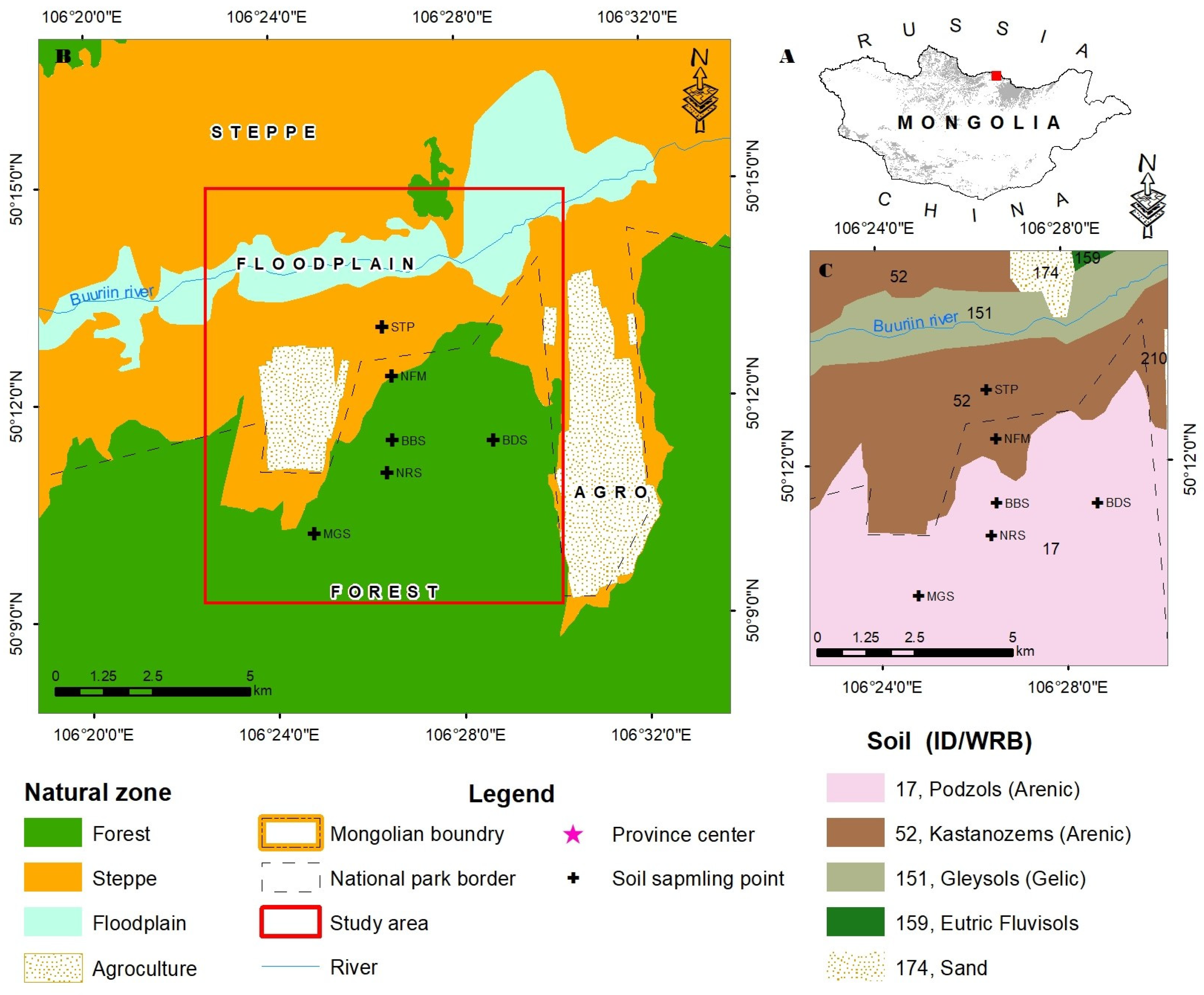

Figure 1.

a) displays the map of Mongolia; b) illustrates the map of Tujiin Nars Nature Conservation Park, Selenge Province, Mongolia, characterized by various environmental zones. c) illustrates that the study region is situated inside the Tujiin Nars, characterized by several soil types.

Figure 1.

a) displays the map of Mongolia; b) illustrates the map of Tujiin Nars Nature Conservation Park, Selenge Province, Mongolia, characterized by various environmental zones. c) illustrates that the study region is situated inside the Tujiin Nars, characterized by several soil types.

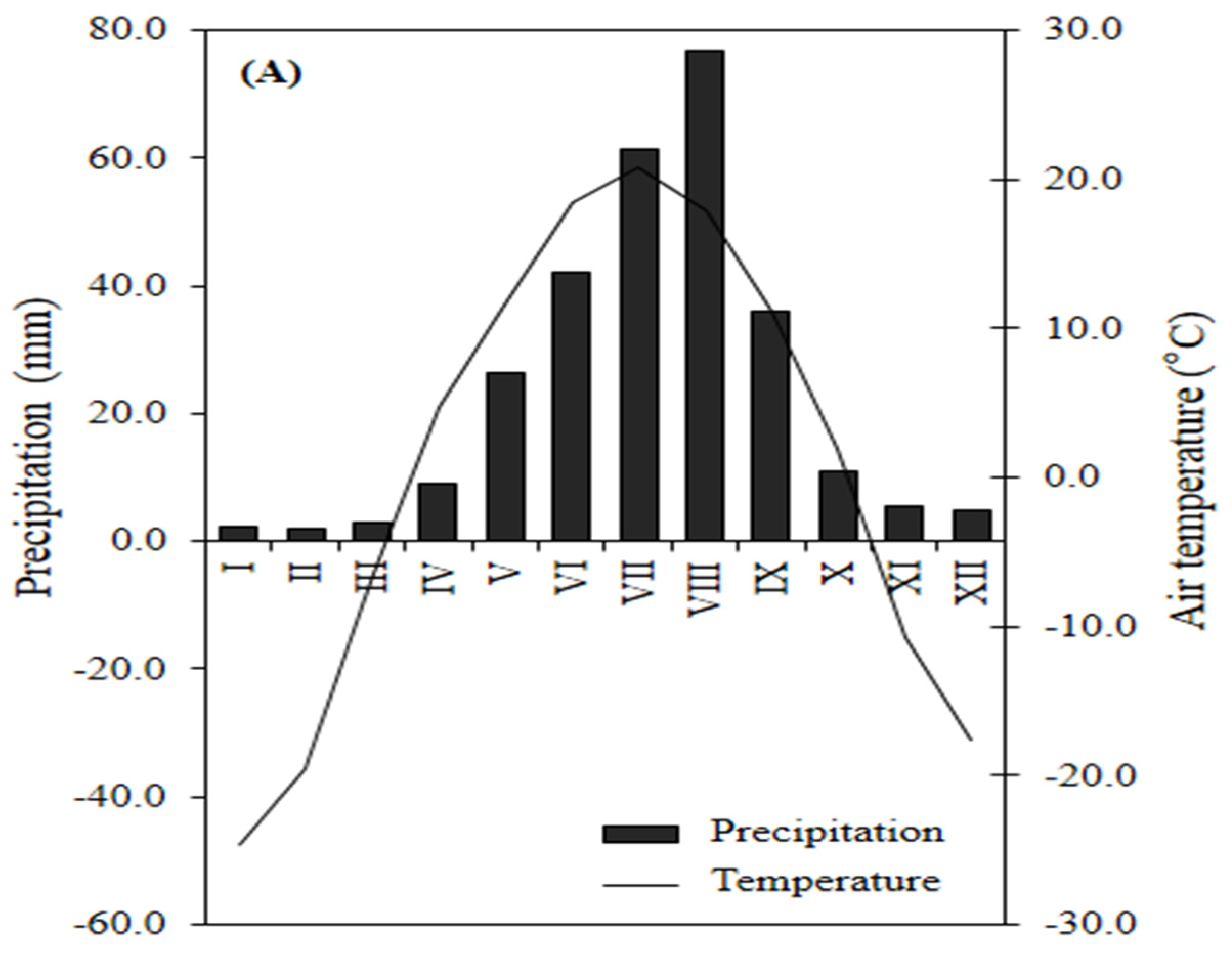

Figure 2.

Overview of the climatic conditions of the study area (meteorological station Sukhbaatar, 2003–2019); Climate diagram; illustrates the integrated representations of total precipitation and mean air temperature on a monthly basis.*Rome numbers described the month.

Figure 2.

Overview of the climatic conditions of the study area (meteorological station Sukhbaatar, 2003–2019); Climate diagram; illustrates the integrated representations of total precipitation and mean air temperature on a monthly basis.*Rome numbers described the month.

Figure 3.

The graphs demonstrate the relationship between species richness and plant coverage percentage across different plot types, suggesting an ecological study comparing different plots. Mean species richness, plant coverage and error bars indicate standard error of values in different plots. (a) Species richness (ranging from 0 to 40); (b) Plant coverage, % (0-80%).

Figure 3.

The graphs demonstrate the relationship between species richness and plant coverage percentage across different plot types, suggesting an ecological study comparing different plots. Mean species richness, plant coverage and error bars indicate standard error of values in different plots. (a) Species richness (ranging from 0 to 40); (b) Plant coverage, % (0-80%).

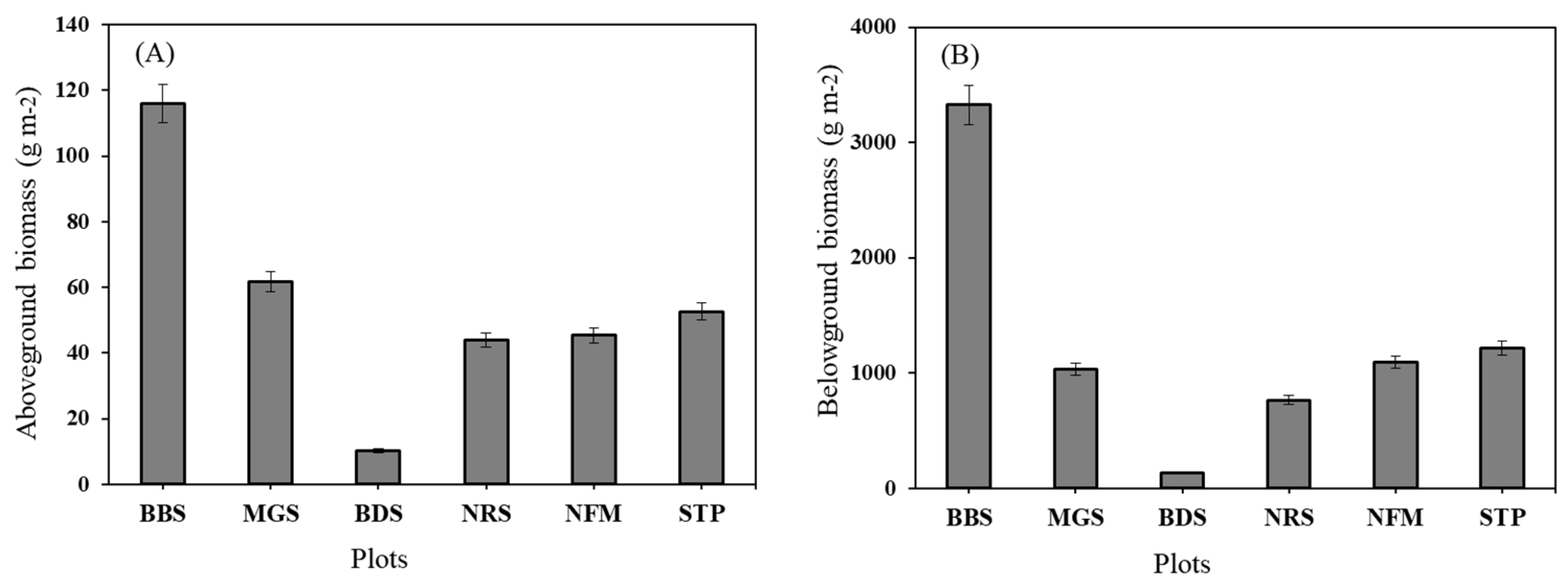

Figure 4.

The graphs show a consistent ratio between above- and below-ground biomass across plots and indicate variability or standard error for each plot. (a) Y-axis is an above-ground (g/m²), ranging from 0 to 140, (b) Y-axis: Below-ground biomass (g/m²), ranging from 0 to 4000 and X-axis: Different plot types: BBS, MGS, BDS, NRS, NFM, and STP.

Figure 4.

The graphs show a consistent ratio between above- and below-ground biomass across plots and indicate variability or standard error for each plot. (a) Y-axis is an above-ground (g/m²), ranging from 0 to 140, (b) Y-axis: Below-ground biomass (g/m²), ranging from 0 to 4000 and X-axis: Different plot types: BBS, MGS, BDS, NRS, NFM, and STP.

Figure 5.

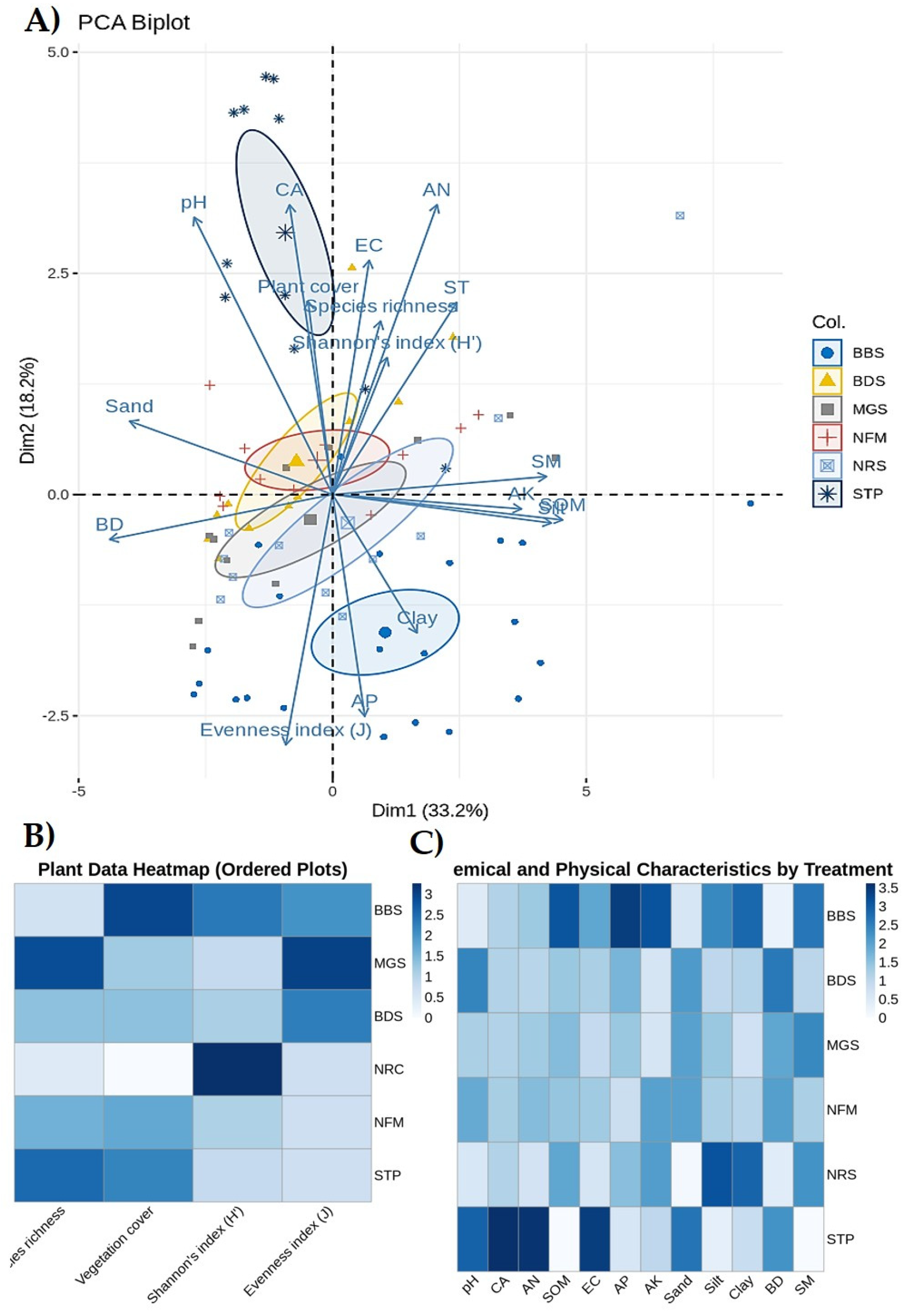

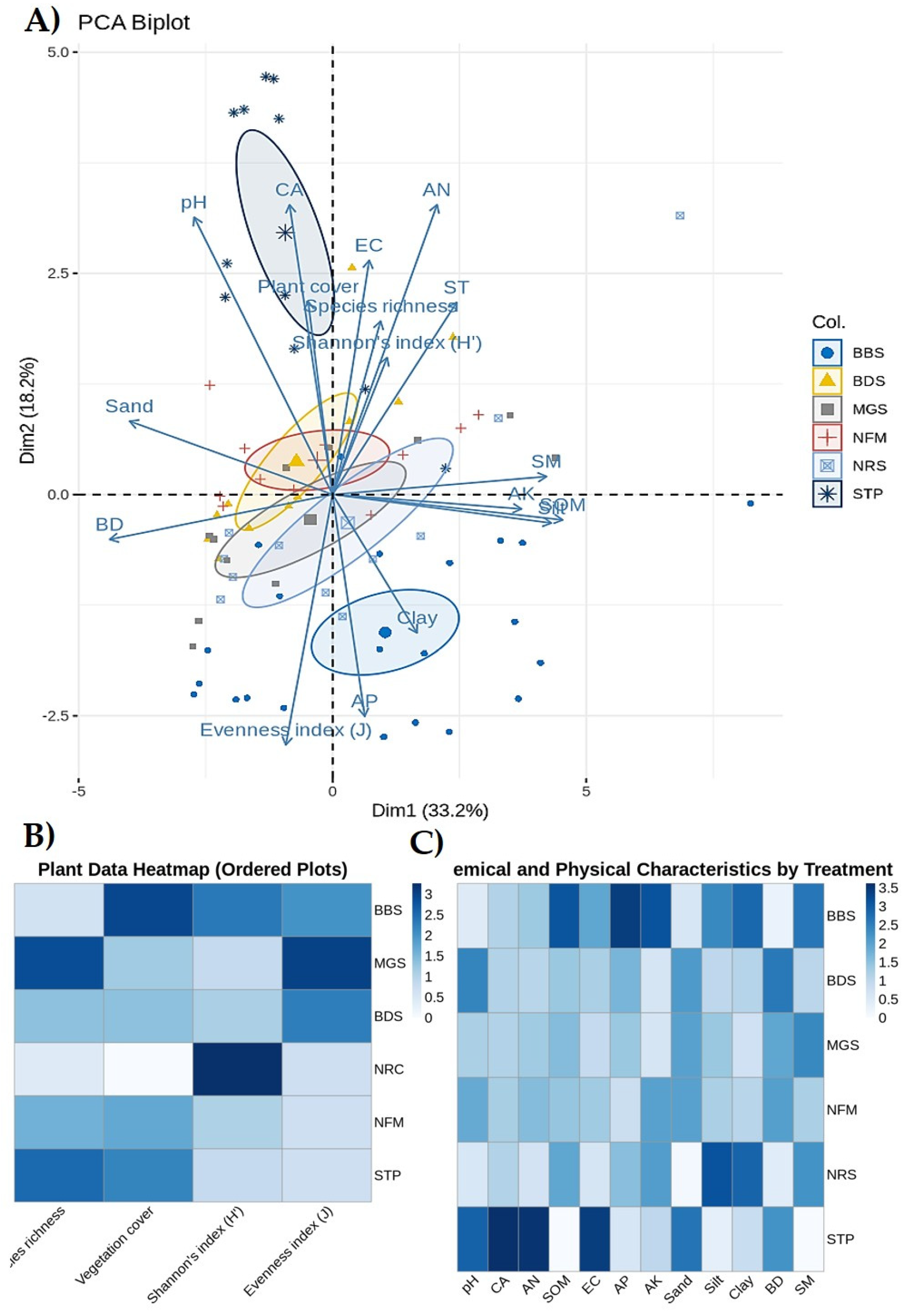

(a) Component Analysis (PCA) biplot illustrates the correlations between variables and samples across two main components (Dim1 and Dim2), accounting for 33.2% and 18.2% of the variance, respectively. Arrows: Indicate variables (e.g., pH, Sand, Clay, Shannon's index, Evenness index, etc.). The orientation and magnitude of the arrows signify the influence of each variable on the principal components. Ellipses: Indicate clusters of samples (e.g., BBS, MGS, BDS, NRS, NFM, STP) according to their similarity. Principal component analysis and heatmap for vegetation and soil parameters under different plots (BBS, BDS, MGS, NFM, NRS, STP). (b) Heat-map of four vegetation parameters in six different plots. (c) Heat-map of twelve soil parameters in six different plots. This heatmap visualizes plant-related variables (species richness, vegetation cover, Shannon's index, and Evenness index) across different plots (BBS, MGS, BDS, NRS, color gradient: darker blue indicates higher values, while lighter blue indicates lower values.

Figure 5.

(a) Component Analysis (PCA) biplot illustrates the correlations between variables and samples across two main components (Dim1 and Dim2), accounting for 33.2% and 18.2% of the variance, respectively. Arrows: Indicate variables (e.g., pH, Sand, Clay, Shannon's index, Evenness index, etc.). The orientation and magnitude of the arrows signify the influence of each variable on the principal components. Ellipses: Indicate clusters of samples (e.g., BBS, MGS, BDS, NRS, NFM, STP) according to their similarity. Principal component analysis and heatmap for vegetation and soil parameters under different plots (BBS, BDS, MGS, NFM, NRS, STP). (b) Heat-map of four vegetation parameters in six different plots. (c) Heat-map of twelve soil parameters in six different plots. This heatmap visualizes plant-related variables (species richness, vegetation cover, Shannon's index, and Evenness index) across different plots (BBS, MGS, BDS, NRS, color gradient: darker blue indicates higher values, while lighter blue indicates lower values.

Figure 6.

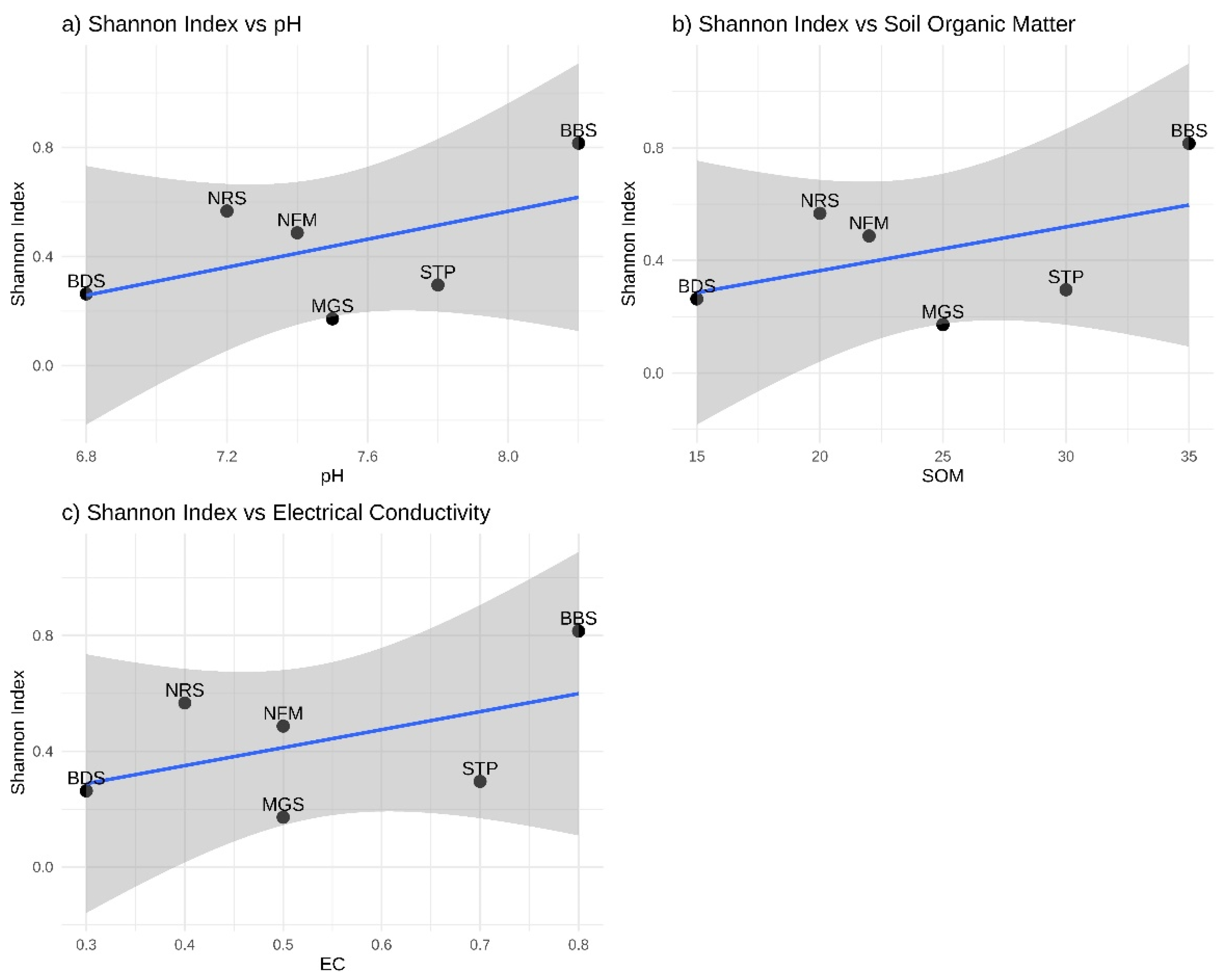

Relationships between Shannon diversity index and soil properties across different plots. Shannon Index (H'): Ranges from 0.172 to 0.816; assesses species diversity by accounting for both richness and evenness. (a) Shannon vs pH: Ranges from 6.8 to 8.2; quantifies soil acidity and alkalinity. (b) Shannon versus SOM (%): Soil Organic Matter ranges from 15% to 35%, indicating organic content. (c) Shannon versus EC (dS/m): Electrical Conductivity ranges from 0.3 to 0.8 dS/m and quantifies soil salinity. *The blue shading denotes 95% confidence intervals, the trend lines illustrate linear regression fits, and the R² values reflect the proportion of variation explained.

Figure 6.

Relationships between Shannon diversity index and soil properties across different plots. Shannon Index (H'): Ranges from 0.172 to 0.816; assesses species diversity by accounting for both richness and evenness. (a) Shannon vs pH: Ranges from 6.8 to 8.2; quantifies soil acidity and alkalinity. (b) Shannon versus SOM (%): Soil Organic Matter ranges from 15% to 35%, indicating organic content. (c) Shannon versus EC (dS/m): Electrical Conductivity ranges from 0.3 to 0.8 dS/m and quantifies soil salinity. *The blue shading denotes 95% confidence intervals, the trend lines illustrate linear regression fits, and the R² values reflect the proportion of variation explained.

Table 1.

Geographical location of the sites.

Table 1.

Geographical location of the sites.

| № |

Plot ID |

Plot definition |

Coordinates |

Altitude (m) |

| 1 |

BBS |

2003 plantation stand |

N 50°11'26.7" |

E 106°26'31.8" |

720 |

| 2 |

MGS |

2004 plantation stand |

N 50°10'10.6" |

E 106°24'49.0" |

712 |

| 3 |

BDS |

2005 plantation stand |

N 50°11'25.4" |

E 106°28'42.8" |

708 |

| 4 |

NRS |

Natural regeneration stand |

N 50°10'59.9" |

E 106°26'24.6" |

714 |

| 5 |

NFM |

Natural forest edge |

N 50°14'7.45" |

E 106°32'58.3" |

666 |

| 6 |

STP |

Steppe area |

N 50°21'69.3" |

E 106°43'92.9" |

624 |

Table 2.

Correlations between tree variables with species richness, plant coverage and above-below-ground biomass.

Table 2.

Correlations between tree variables with species richness, plant coverage and above-below-ground biomass.

| Variables |

BBS |

MGS |

BDS |

NRS |

| SR |

PC |

AGB |

BGB |

SR |

PC |

AGB |

BGB |

SR |

PC |

AGB |

BGB |

SR |

PC |

AGB |

BGB |

| DBH |

-0.14 |

-0.11 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.21 |

0.21 |

-0.5 |

-0.51 |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.48 |

0.59 |

0.38 |

0.31 |

0.03 |

0.26 |

| Height |

-0.2 |

-0.21 |

0.45 |

0.56 |

0.28 |

0.28 |

-.619* |

-0.59 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

0.04 |

0.21 |

0.3 |

0.43 |

0.16 |

0.39 |

| BA |

-0.18 |

-0.15 |

0.48 |

0.49 |

0.18 |

0.18 |

-0.39 |

-0.38 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.46 |

0.57 |

0.47 |

0.23 |

-0.1 |

0.17 |

| Vol |

-0.17 |

-0.15 |

0.53 |

0.57 |

0.19 |

0.19 |

-0.46 |

-0.44 |

0.06 |

0.06 |

0.45 |

0.6 |

0.43 |

0.28 |

-0.02 |

0.25 |

| CL |

-0.2 |

-0.15 |

.627* |

.653*

|

0.4 |

0.4 |

-0.57 |

-0.56 |

-0.33 |

-0.34 |

-0.02 |

0.14 |

0.29 |

0.42 |

0.16 |

0.41 |

| CD |

0.18 |

0.23 |

-0.06 |

-0.01 |

0.33 |

0.33 |

-0.34 |

-0.4 |

0.27 |

0.27 |

0.33 |

0.52 |

0.15 |

0.18 |

0.09 |

0.37 |

| CPA |

0.14 |

0.19 |

-0.17 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-0.1 |

-.637* |

-.781** |

0.49 |

0.48 |

0.1 |

0.29 |

0.22 |

0.27 |

0.08 |

0.35 |

Table 3.

Correlations between soil variables with species richness, plant coverage and above-below ground biomass of studied sample plots.

Table 3.

Correlations between soil variables with species richness, plant coverage and above-below ground biomass of studied sample plots.

| Variables |

BBS |

MGS |

BDS |

| SR |

PC |

AGB |

BGB |

SR |

PC |

AGB |

BGB |

SR |

PC |

AGB |

BGB |

| pH |

0.23 |

0.266 |

-.645* |

-.744** |

-0.034 |

-0.033 |

-0.212 |

-0.099 |

-0.392 |

-0.396 |

-0.297 |

-0.195 |

| SOC |

-0.111 |

-0.155 |

0.302 |

0.442 |

-0.149 |

-0.148 |

0.083 |

0.232 |

-0.273 |

-0.272 |

0.341 |

0.471 |

| BD |

0.23 |

0.266 |

-.645* |

-.744** |

0.096 |

0.095 |

-0.078 |

-0.23 |

0.34 |

0.333 |

-0.382 |

-0.45 |

| SM |

-0.135 |

-0.172 |

-0.149 |

-0.013 |

-0.157 |

-0.156 |

0.165 |

0.317 |

-0.25 |

-0.25 |

0.339 |

0.497 |

| Variables |

NRS |

NFM |

STP |

| SR |

PC |

AGB |

BGB |

SR |

PC |

AGB |

BGB |

SR |

PC |

AGB |

BGB |

| pH |

-0.294 |

-.616* |

0.122 |

-0.094 |

-0.425 |

-0.252 |

-0.126 |

-0.238 |

0.162 |

0.268 |

-0.227 |

-0.371 |

| SOC |

.657* |

0.447 |

-0.222 |

-0.082 |

0.517 |

0.235 |

0.241 |

0.376 |

-0.095 |

-0.217 |

0.315 |

.439** |

| BD |

-0.036 |

-.749** |

-0.529 |

-.627* |

-0.57 |

-0.297 |

-0.25 |

-0.41 |

-0.036 |

0.074 |

-0.123 |

-0.243 |

| SM |

0.35 |

.683* |

0.184 |

0.309 |

.609* |

0.328 |

0.27 |

0.396 |

0.205 |

0.085 |

.411** |

0.468 |

Table 4.

Quantitative analysis for IV of herbaceous vegetation in BBS, MGS and BDS plots.

Table 4.

Quantitative analysis for IV of herbaceous vegetation in BBS, MGS and BDS plots.

| Plots |

BBS |

MGS |

BDS |

| Species |

RF, % |

RC, % |

IV, % |

RF, % |

RC, % |

IV, % |

RF, % |

RC, % |

IV, % |

|

Achillea asiatica Serg. |

17 |

0.2 |

8.4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Agrimonia pilosa Ledeb. |

17 |

2.1 |

9.4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Artemisia commutata Bess. |

17 |

0.2 |

8.4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Artemisia integrifolia L. |

17 |

1 |

8.9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Cirsium esculentum (Siev.) C.A.Mey. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4.8 |

2.4 |

3.6 |

|

Cleistogenes squarrosa (Trinius) Keng. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4.8 |

4.8 |

4.8 |

|

Elymus sibiricus L. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4.8 |

2.4 |

3.6 |

|

Festuca valesiaca Gaud. |

17 |

2.1 |

9.4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Galatella dahurica DC. |

17 |

1 |

8.9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Heteropappus hispidus (Thunbg.) Less. |

17 |

1 |

8.9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4.8 |

2.4 |

3.6 |

|

Iris tigrida Bunge ex Ledebour. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4.8 |

2.4 |

3.6 |

|

Leptopyrum fumarioides (L.) Reichb. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4.8 |

1 |

2.9 |

|

Linum sibiricum DC. |

17 |

2.1 |

9.4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Papaver nudicaule Ldb. |

17 |

0.6 |

8.6 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Phlomis tuberosa L. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7.1 |

2.7 |

4.9 |

4.8 |

2.4 |

3.6 |

|

Potentilla acaulis L. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4.8 |

2.4 |

3.6 |

|

Sedum aizoon L. |

17 |

0.4 |

8.5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Sibbaldia adpressa Bunge. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7.1 |

5.4 |

6.3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Trifolium lupinaster L. |

17 |

1 |

8.9 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 5.

Quantitative analysis for IV of herbaceous vegetation in NRS, NFM and STP plots.

Table 5.

Quantitative analysis for IV of herbaceous vegetation in NRS, NFM and STP plots.

| Plots |

NRS |

NFM |

STP |

| Species |

RF, % |

RC, % |

IV, % |

RF, % |

RC, % |

IV, % |

RF, % |

RC, % |

IV, % |

|

Allium bidentatum Fisch.ex.Prokh. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

6.3 |

8.2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Allium linare L. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

2.6 |

7.5 |

|

Caragana microphylla Lam. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

2.6 |

7.5 |

|

Carum carvi L. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

1.6 |

5.8 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Cirsium esculentum (Siev.) C.A.Mey. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

1.3 |

6.9 |

|

Cleistogenes squarrosa (Trinius) Keng. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

2.6 |

7.5 |

|

Cymbaria dahurica L. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

1.8 |

7.2 |

|

Elymus sibiricus L. |

10 |

8.9 |

9.4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Festuca valesiaca Gaud. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

2.6 |

7.5 |

|

Fragaria orientalis Losinsk. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

1.3 |

6.9 |

|

Galatella dahurica DC. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

1.6 |

5.8 |

13 |

1.3 |

6.9 |

|

Galium verum L. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

1.3 |

6.9 |

|

Inula britannica L. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

0.3 |

6.4 |

|

Leontopodium ochroleucum Beauverd. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

1.3 |

6.9 |

|

Lespedeza davhurica (Laxm.) Schlinder. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

0.3 |

6.4 |

|

Linum sibiricum DC. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

2.6 |

7.5 |

|

Patrinia rupestris (Pall.) Dufr. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

5.1 |

8.8 |

|

Phlomis tuberosa L. |

10 |

3.3 |

6.7 |

10 |

1.6 |

5.8 |

13 |

1.3 |

6.9 |

|

Potentilla acaulis L. |

10 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Plantago major L. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

1.3 |

6.9 |

|

Potentilla acaulis L. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

1.6 |

5.8 |

13 |

1.3 |

6.9 |

|

Stellera chamaejasme (L.) Rydb. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

0.3 |

6.4 |

|

Thalictrum petaloideum L. |

10 |

0.4 |

5.2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 6.

Species diversity indices of studied plots.

Table 6.

Species diversity indices of studied plots.

| Diversity indices |

BBS |

MGS |

BDS |

NRS |

STP |

NFM |

| Shannon index (H') |

0.8156a

|

0.172c

|

0.2632bc

|

0.5671ab

|

0.2959bc

|

0.4871abc |

| Evenness index (J) |

0.1458cd

|

0.4966b

|

0.1720a

|

0.1108cd

|

0.2127c

|

0.0869d

|

| Simpson index (D) |

1.1638c

|

0.5674ab

|

0.7895a

|

0.0855ab

|

0.2988ab

|

0.440bc

|

Table 7.

Similarity coefficients (%) of studied plots.

Table 7.

Similarity coefficients (%) of studied plots.

| Similarity coefficient, % |

BBS, MGS, BDS, NRS |

STP and NFM |

| Bray and Curtis (BC) |

0.30 |

0.28 |

| Sorensen (Ss) |

20.83 |

46.81 |

Table 8.

Soil properties comparison by depth (n=66).

Table 8.

Soil properties comparison by depth (n=66).

| Variables |

Unit |

Soil depth (cm) |

ANOVA statistic |

| 0-30 |

30-60 |

60-100 |

MS |

F value |

| pH |

|

6.70±0.09b

|

7.01±0.07a

|

7.01±0.06a

|

0.85 |

34.8*** |

| Carbonate (CaCO3) |

% |

0.03±0.03c

|

0.89±0.50a

|

0.35±0.16b

|

4.52 |

30.6*** |

| AN (N-NO-3) |

mg kg-1

|

3.16±0.15a

|

2.24±0.25b

|

2.12±0.19b

|

8.69 |

20.5*** |

| OC |

g kg-1

|

10.1±1.00a

|

3.7±0.39b

|

1.4±0.09c

|

54.37 |

60.6*** |

| SOCs |

Mg ha-1

|

9.16±0.81a

|

5.67±0.58b

|

2.33±0.14c

|

326.79 |

58.0*** |

| AP (P2O5) |

mg kg-1

|

21.3±1.59b

|

26.4±2.17a

|

23.8±1.56ab

|

16.02 |

4.0* |

| AK (K2O) |

mg kg-1

|

114.6±9.79a

|

79.4±2.76b

|

74.8±2.39b

|

1288.87 |

13.5*** |

| Sand (2-0.05 mm) |

% |

72.9±1.41c

|

77.9±1.19b

|

86.6±0.44a

|

1335.33 |

94.1*** |

| Silt (0.05-0.002 mm) |

% |

15.1±1.16a

|

9.0±0.7b

|

3.8±0.24c

|

883.58 |

72.5*** |

| Clay (<0.002 mm) |

% |

12.0±0.59b

|

13.0±0.57a

|

9.5±0.37c

|

81.83 |

30.0*** |

| BD |

g cm-3

|

1.36±0.02c

|

1.54±0.01b

|

1.59±0.01a

|

1.24 |

120.5*** |

| SM |

% |

8.87±0.37a

|

5.63±0.21b

|

3.66±0.12c

|

578.42 |

158.0*** |

| ST |

0C |

20.3±0.30a

|

17.4±0.23b

|

15.3±0.23c

|

528.90 |

446.6*** |

Table 9.

Soil properties of studied plots (n=48; depth=0-30 cm).

Table 9.

Soil properties of studied plots (n=48; depth=0-30 cm).

| Variables |

Unit |

BBS |

NRS |

STP |

BDS |

NFM |

MGS |

F value |

| pH |

|

6.10±0.11d

|

6.51±0.07c

|

7.00±0.47b

|

7.39±0.03a

|

6.77±0.13bc

|

6.88±0.11bc

|

13.14*** |

| AN (N-NO-3) |

mg kg-1

|

2.99±0.54ab

|

4.07±0.62a

|

2.88±0.58b

|

3.17±0.58ab

|

3.22±0.51ab

|

3.56±0.81ab

|

1.51ns |

| OC |

g kg-1

|

26.7±12.89a

|

14.6±7.52ab

|

8.7±4.04b

|

15.2±7.61ab

|

15.8±3.53ab

|

16.7±5.43ab

|

1.8ns |

| SOCs |

Mg ha-1

|

22.2±6.95a

|

10.9±0.84bc

|

8.1±1.51c

|

14.5±3.02abc

|

16.5±5.83ab

|

15.3±4abc

|

3.8* |

| AP (P2O5) |

mg kg-1

|

26.4±9.32a

|

17.3±4.42a

|

20.1±7.37a

|

23.9±5.99a

|

14.7±5.34a

|

21.2±8.69a

|

1.1ns |

| AK (K2O) |

mg kg-1

|

173.5±72.9a

|

119.3±36.4ab

|

108.5±35.5ab

|

84.1±36.3b

|

119.3±53.9ab

|

94.9±27ab

|

1.36ns |

| Sand (2-0.05mm) |

% |

69.5±0.73b

|

69.5±3.91b

|

82.9±0.82a

|

76.4±6.47ab

|

75.9±6.93ab

|

73.3±3.59b

|

3.93* |

| Silt (0.05-0.002mm) |

% |

19.8±1.94a

|

17.9±7.54a

|

8.4±1.59b

|

11.6±4.89ab

|

12.7±5.62ab

|

15.3±3.71ab

|

2.38ns |

| Clay (<0.002mm) |

% |

10.8±1.32ab

|

12.6±3.64a

|

8.6±1.37b

|

12±1.8ab

|

11.4±1.74ab

|

11.4±0.53ab

|

1.48ns |

| BD |

g cm-3

|

1.25±0.2a

|

1.24±0.2a |

1.46±0.07a

|

1.46±0.11a

|

1.42±0.14a

|

1.35±0.12a

|

1.41ns |

| SM |

% |

10.6±1.3a

|

8.25±1.97ab |

5.15±2.23b

|

7.97±2.72ab

|

9.41±2.62ab

|

12.06±4.33a

|

2.35ns |

| ST |

0C |

18.65±1.62c

|

17.74±0.74c |

24.68±2.56a

|

21.22±0.85b

|

21.53±1.27b

|

18.09±0.94c

|

9.96*** |

Table 10.

Soil properties of studied plots (n=36; depth=30-60 cm).

Table 10.

Soil properties of studied plots (n=36; depth=30-60 cm).

| Variables |

Unit |

BBS |

NRS |

STP |

BDS |

NFM |

MGS |

F value |

| pH |

|

6.63±0.12e

|

6.79±0.06d

|

7.61±0.02a

|

7.28±0.07b

|

7.13±0.01c

|

6.91±0.04d

|

62.8*** |

| AN (N-NO-3) |

mg kg-1

|

2.64±0.7b

|

1.58±0.18b

|

4.29±1.44a

|

1.73±0.38b

|

2.03±0.18b

|

1.81±0.18b

|

4.45* |

| OC |

g kg-1

|

9.97±1.48a

|

6.38±1.46b

|

2.19±0.45c

|

5.93±1.64b

|

6.02±2.16b

|

5.14±0.75bc

|

5.99** |

| SOCs |

Mg ha-1

|

14.63±1.78a

|

10.03±2.23b

|

3.31±0.64c

|

9.22±2.58b

|

9.31±3.25b

|

8.02±1.04b

|

5.95** |

| AP (P2O5) |

mg kg-1

|

39.19±1.74a

|

31.81±3.62b

|

14.03±3.87d

|

24.07±2.07c

|

17.66±1.2cd

|

20.68±4.04cd

|

19.9*** |

| AK (K2O) |

mg kg-1

|

103.04±0a

|

74.13±5.11b

|

70.52±0b

|

70.52±8.85b

|

77.75±5.11b

|

70.52±0b

|

14.7*** |

| Sand (2-0.05mm) |

% |

72.14±1.38c

|

76.53±1.72c

|

83.36±1.19a

|

80.92±1.82ab

|

79.46±3.01ab

|

82.38±3.29a

|

7.06** |

| Silt (0.05-0.002mm) |

% |

12.69±1.38a

|

9.56±0.66ab

|

5.13±0.6c

|

7.81±0.91bc

|

8.93±2.45abc

|

7.32±2.6bc

|

4.71* |

| Clay (<0.002mm) |

% |

15.17±0a

|

13.91±1.23a

|

11.52±0.6b

|

11.27±0.91b

|

11.61±0.7b

|

10.3±0.69b

|

11.2*** |

| BD |

g cm-3

|

1.47±0.04b

|

1.57±0.01a

|

1.52±0.02ab

|

1.55±0.02a

|

1.55±0.02a

|

1.57±0.03a

|

4.56* |

| SM |

% |

7.65±0.73a

|

6.11±0.79b

|

5.3±0.5b

|

4.86±0.78bc

|

4.44±0.83c

|

3.96±0.38c

|

7.5** |

| ST |

0C |

15.71±0.37b

|

15.38±0.51b

|

19.77±0.45a

|

18.86±0.44a

|

19.49±0.33a

|

15.76±0.55b

|

43.5*** |