Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- To reduce the total annual GHG emissions from international shipping by at least 20%, striving for 30%, by 2030, compared to 2008.

- To reduce the total annual GHG emissions from international shipping by at least 70%, striving for 80%, by 2040, compared to 2008.

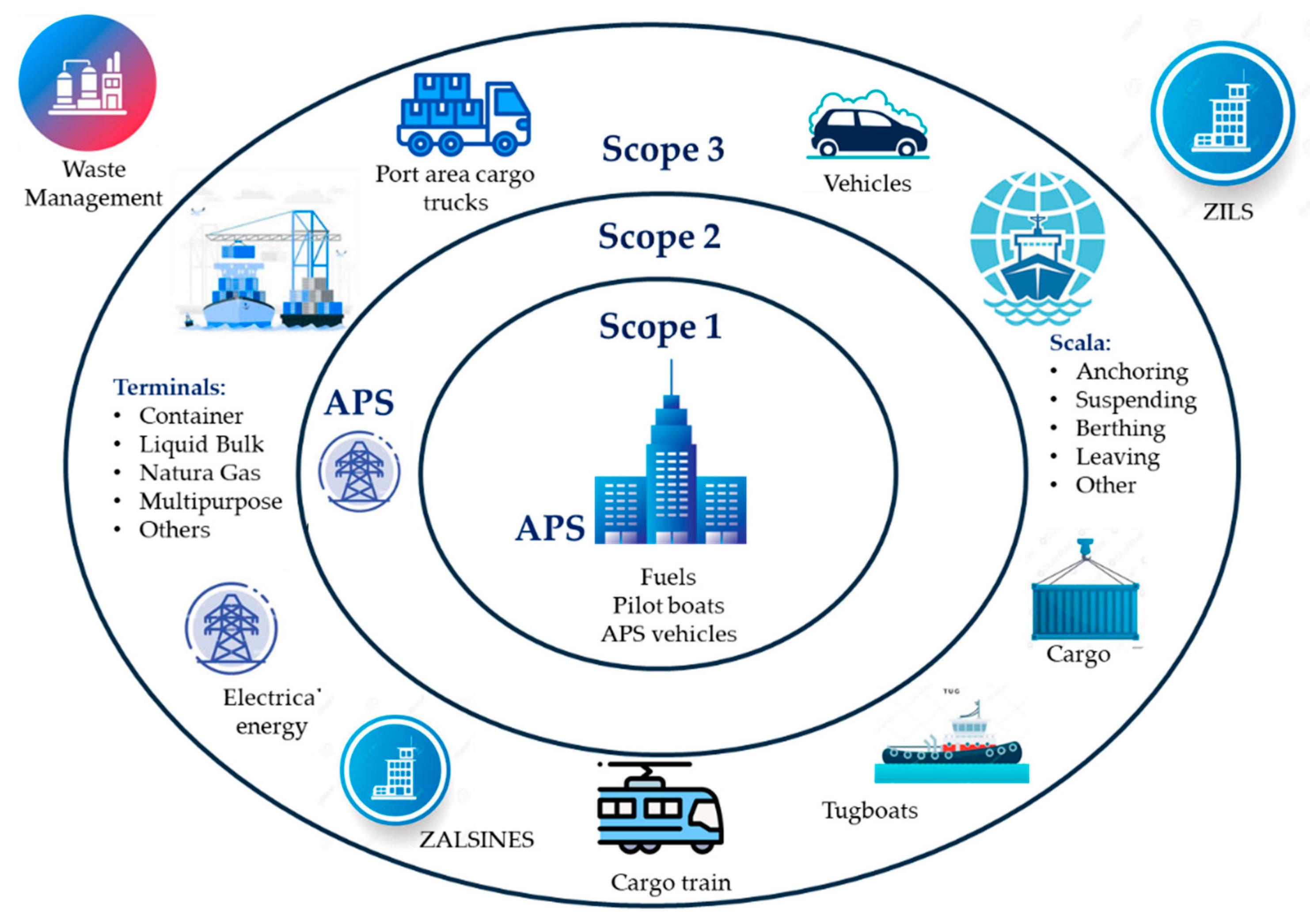

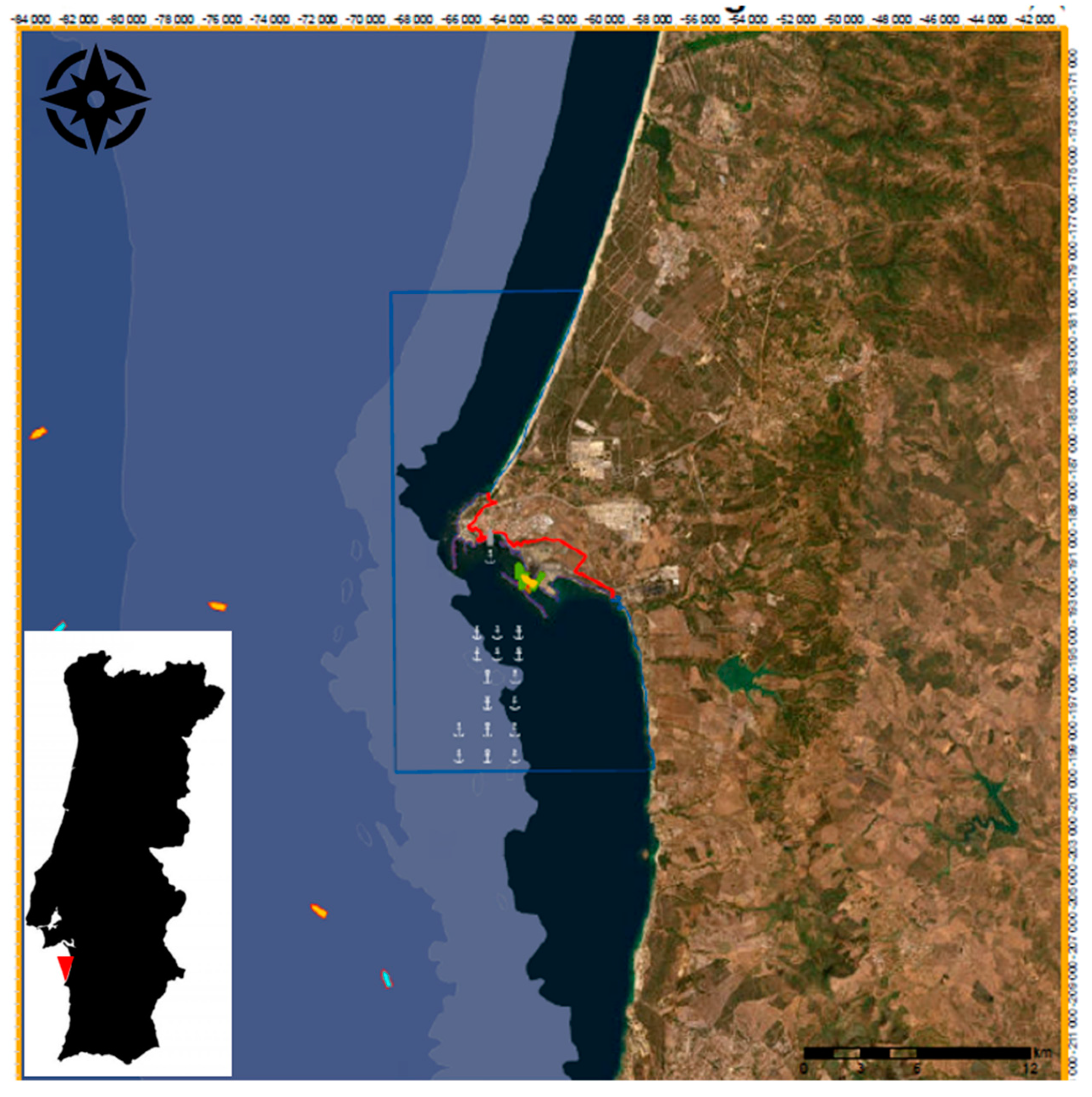

2. Material and Methods

| Terminal | Depth (m) | Cargo type |

|---|---|---|

| SCT | 17 | Container. |

| LBT | 28 | Crude oil, refined oil, liquefied petroleum gas, methanol, and chemical naphtha. |

| NGT | 15 | Liquefied natural gas (LNG). |

| PCT | 12 | Propylene, ethylene, butadiene, ethyl tertiary butyl ether, ethanol, methyl tertiary butyl ether, aromatic mixtures, and methanol. |

| GCT | 18 | Dry bulk, general cargo, and roll-on/roll-off ( ro_ro ). |

- Natural gas for the boilers.

- Diesel fuel for the emergency power plant.

- Diesel fuel for employees’ collective transport vehicles.

- Diesel fuel and gasoline for private employee transport vehicles.

- Diesel fuel for the pilot boats who steer the ships within the AJPS.

- Type of ship and fuel, IMO id and others.

-

Diesel and gasoline for the pendular movement of employees by terminal in private and collective vehicles. Generally, these data are not included in the carbon footprint calculation models [29]. In the present study it was considered all the data in these calculations to ensure greater accuracy and detail in the model. We considered:

- o

- Number of employees at concessionaires and terminals, provided by APS.

- o

- Vehicle occupancy rate: 1,2 passengers/vehicle.

- o

- Distribution of vehicles: 60% diesel and 40% gasoline.

- o

- In accordance with the methodology, only the journey within the APSJ was considered.

- Diesel for the transport of cargo by container, general cargo and cryogenic trucks for LNG.

- Electric power for the train line for container transport. Load factor: full locomotive and full truck (cargo).

3. Results and Discussion

| Energy consumption (MWh) | |||||||

| Scope | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Average | Average (%) |

| 1 | 1.758,78 | 2.024,81 | 1.802,64 | 1.799,73 | 1.601,66 | 1.797,52 | 0,43 |

| 2 | 1.600,12 | 1.613,60 | 1.367,00 | 1.643,00 | 1.504,00 | 1.545,54 | 0,37 |

| 3 | 386.686,69 | 380.522,45 | 413.976,29 | 536.283,83 | 377.707,63 | 419.035,38 | 99,21 |

| Total | 390.045,59 | 384.160,87 | 417.145,93 | 539.726,56 | 380.813,29 | 422.378,45 | 100,00 |

| Base (%) | 100,00 | 98,49 | 106,95 | 138,38 | 97,63 | -- | -- |

| Carbon footprint (tCO2eq) | |||||||

| Scope | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Average | Average (%) |

| 1 | 593,94 | 742,29 | 593,73 | 579,18 | 545,99 | 611,03 | 0,27 |

| 2 | 459,00 | 376,00 | 251,00 | 266,00 | 205,00 | 311,40 | 0,14 |

| 3 | 226.347,11 | 179.767,30 | 217.452,23 | 300.064,52 | 194.915,94 | 223.709,42 | 99,59 |

| Total | 227.400,05 | 180.885,60 | 218.296,96 | 300.909,70 | 195.666,93 | 224.631,85 | 100,00 |

| Base (%) | 100,00 | 79,55 | 96,00 | 132,33 | 86,05 | -- | -- |

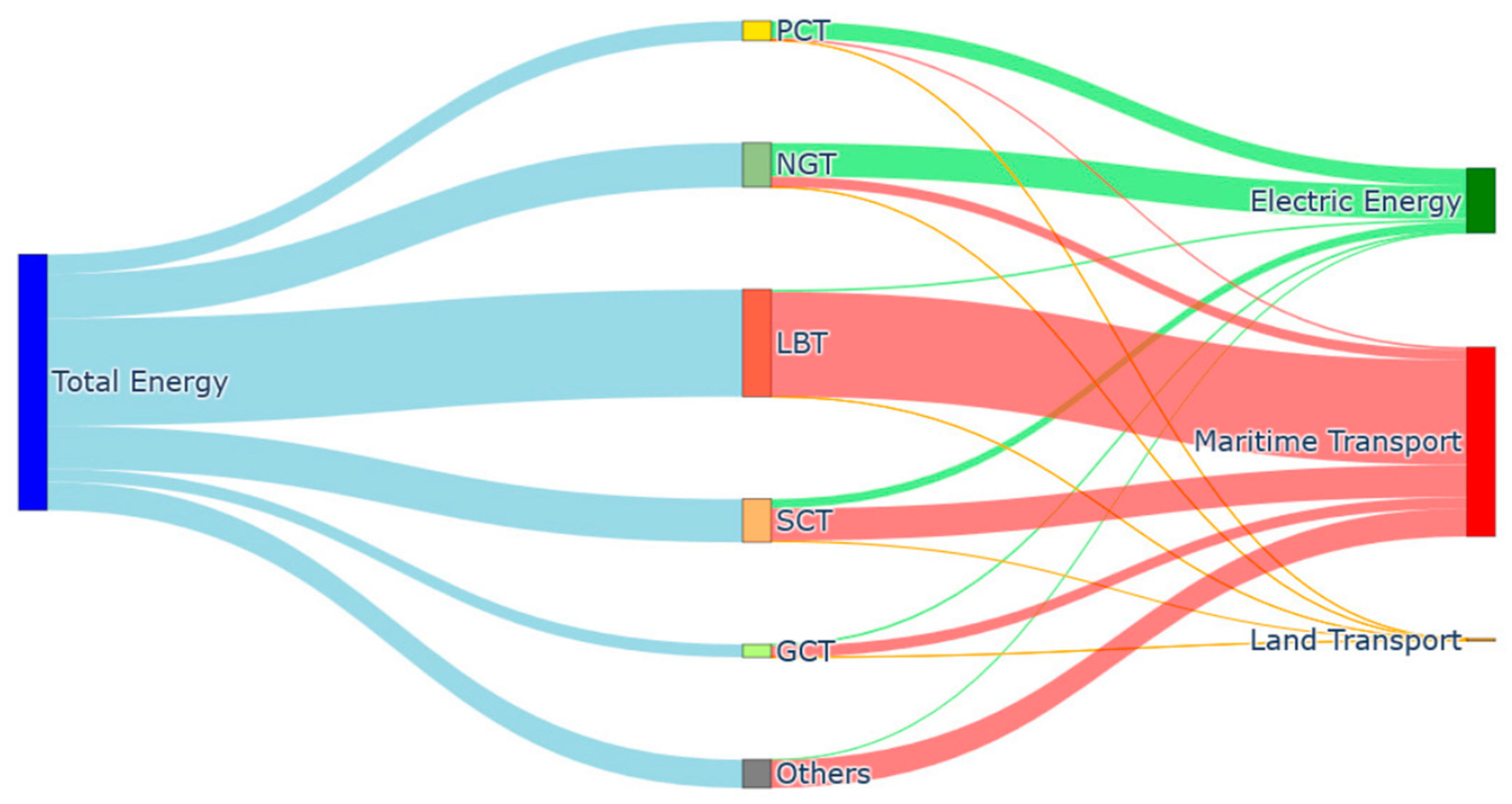

| Energy consumption (MWh) | ||||||||

| Font | SCT | LBT | NGT | PCT | GCT | Others | Scope 3 | Scope 3 (%) |

| Electric energy | 17.163,28 | 4.776,63 | 62.053,12 | 31.634,13 | 2.209,22 | 733,45 | 118.569,83 | 28,03 |

| Land Transport | 3.032,28 | 214,00 | 228,95 | 86,60 | 455,07 | -- | 4.016,90 | 0,95 |

| Maritime Transport | 59.356,17 | 192.397,26 | 19.142,65 | 4.425,97 | 21.126,60 | 3.978,61 | 300.427,26 | 71,02 |

| Total | 79.551,73 | 197.387,89 | 81.424,72 | 36.146,70 | 23.790,89 | 4.712,06 | 423.013,99 | 100,00 |

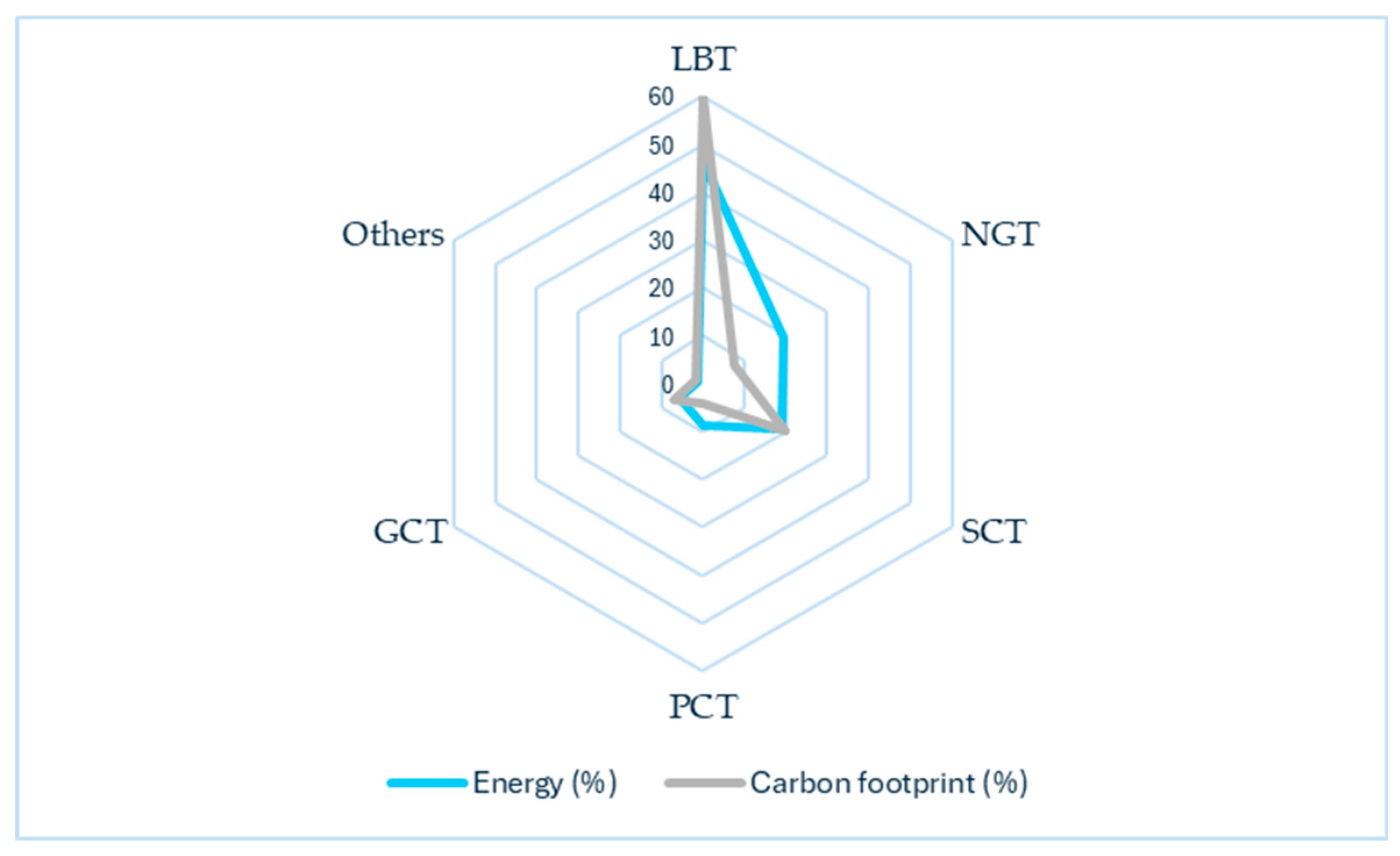

| Contribution (%) | 18,81 | 46,66 | 19,25 | 8,55 | 5,62 | 1,11 | -- | -- |

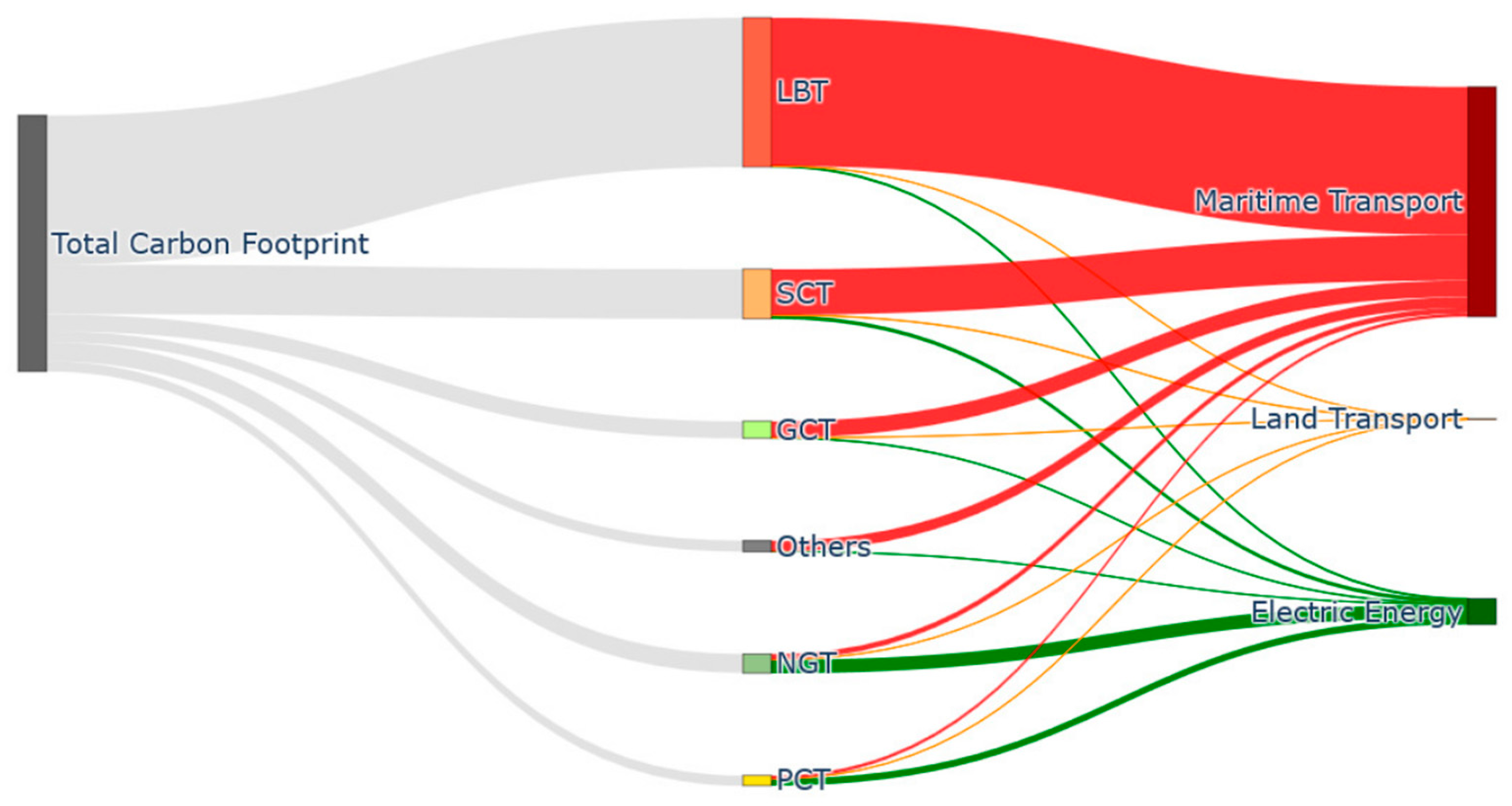

| Carbon footprint (tCO2eq) | ||||||||

| Font | SCT | LBT | NGT | PCT | GCT | Others | Scope 3 | Scope 3 (%) |

| Electric energy | 3.405,46 | 968,07 | 12.269,49 | 6.218,96 | 523,05 | 150 | 23.535,03 | 10,33 |

| Land Transport | 408,09 | 28,76 | 30,81 | 11,66 | 61,24 | -- | 540,60 | 0,24 |

| Maritime Transport | 41.494,34 | 135.238,27 | 5.087,54 | 3.109,00 | 14.886,23 | 3.978,61 | 74.524,11 | 89,43 |

| Total | 45.307,89 | 136.235,10 | 17.387,84 | 9.339,62 | 15.470,52 | 4.128,61 | 227.869,58 | 100,00 |

| Contribution (%) | 19,88 | 59,79 | 7,63 | 4,10 | 6,79 | 1,81 | -- | -- |

- The reduction in the number of ships has a moderating effect on the carbon footprint, suggesting that this variable is a key factor in reducing emissions.

- There are inflection points where energy consumption and emissions do not decrease in the same proportion as the cargo, suggesting the presence of additional factors influencing these variables. These factors include the emission factor from electricity grid consumption, which is decreasing in Portugal, and the efficiency in port operations, terminal depth, and typology of ships.

- There is a decoupling between the cargo and the other variables, indicating that the relationship is not deterministic and that other considered factors play an important role, such as the berthing and docking time of ships at different terminals.

- a)

-

Scope 1 which are the emissions due to the consumption of APS fuels. During this period:

- a.

- The boiler’s natural gas consumption has been reduced due to the close of the restaurant, in 2021.

- b.

- During the years 2021 and 2022 was not reported fuel consumption for electrical plants.

- c.

- There is a 15,7% reduction in diesel consumption of the pilot boats.

- b)

- c)

-

Scope 3 represents the carbon footprint of the concessionaries, during this period:

- a.

- On average, LBT contributes in 59,79% of the carbon footprint. In addition, 99,3% of its emissions are due to maritime transport. For the period 2018-2022, the managed load has increased in 17,2% and the number of ships served only 2,3%, going from 23.238,2 to 26.467,6 t/ship, that is, larger. On average, the 56 and 36% of emissions occur during anchoring and berthing, respectively. During 2022, there is an increase in these times of 31,3 and 15,9%, respectively. Even the percentage of ships anchoring has increased from 51 to 61% during this period. Which indicates that the measures to reduce his carbon footprint must be aimed at lowering he percentage and anchoring time of the ships.

- b.

- The SCT contributes to average in a 19,88% in the carbon footprint. This terminal for December 2019 has an increase in the number of its porticos to 10, which has increased his efficiency in the loading and unloading of the container ships. The 91,2% of their emissions are due to maritime transport, related to 27 and 52% that occur during anchoring and berthing, respectively. For this period, he percentage of ships in anchoring has been reduced from 9,9 to 4,8%. However, it has an increase of these times of 37,3 and 29,9%, thanks to the fact that they have an increment in the cargo handled from 1.726,3 to 2.104,6 TEU/ship. It represents being the most efficient terminal in the port by his relatively low number of ships in anchoring. The remainder of its emissions are due to electric energy consumption (7,5%) and terrestrial transport. The electric energy in this terminal is used for the cranes and gantries operation and their building headquarters, the which they had an increase in his consumption. However, thanks to the reduction of the emissions factor [48], the carbon footprint has been diminished. Finally, the land transport contributes with 1,3% for the carbon footprint, where 70% of this value is related to the transport of cargo within AJPS (30 and 40% by rail and road transport, respectively) in 1,9 (rail) and 2,1 km (road). For this type of terminals, measures to reduce his carbon footprint are found to be related to the use of alternative fuels in auxiliaries’ engines, increasing the efficiency of this engine or the possibility of replacement by electrical engines fed from the terminal during the berthing, which represents 41,9% of the total operation time in the port and 51,8% contribution to the carbon footprint.

- c.

- NGT contributes in 7,63% to the carbon footprint. Unlike the other two terminals, 70,6 % is due to energy consumption of the facility pumping systems for load and unload the ships. This terminal has an increase in its cargo and number of ships for this period, which impacts positively for the energetic transition of the country, being LNG the fuel that has replaced coal in its power plants electrical [54]. What in your opinion time to shocked in the reduction of emissions from this terminal. However, this has gone from 63.396,6 to 59.271,9 t/ship, for the years 2018 and 2022, respectively. The 29,2% of its carbon footprint is due to maritime transportation, which has been reduced, thanks to the reduction of the anchoring and berthing times of 16,9 and 5,06%, respectively. In addition, the reduction from 13 to 9% of the ships that anchor, which denotes improvements in his efficiency logistics. Less than 7% of its cargo is transported by land, hence the contribution to the carbon footprint is less than 0,2%. As a measure to reduce his carbon footprint must be include the reduction of the emissions factor by electricity consumption [48], aligned with the decarbonization policy of the energetic matrix in Portugal [54–56]. Additionally, due to the cold losses during the unload process of the ships in this terminal, this could contribute to reducing the refrigerant consumption in the operations of the adjacent terminals (refrigerated containers) and reduce the Port’s total carbon footprint.

- d.

- GCT, PCT and Others contribute a total of 12,7% to the carbon footprint. Approximately 80,6% of this footprint is due to maritime transportation. Of this value, 35,6% are emissions due to the use of the tugboats, which is decarbonization would impact positively in reducing the carbon footprint. By the last half of 2022, the GCT replaced the solids bulk terminal (SBT), which has impacted positively in reducing its carbon footprint.

- e.

- The carbon footprint of the PCT is due by 67 and 33% to electrical energy consumption and maritime transportation, respectively. The carbon footprint by consumption of the electric energy has been reduced thanks to the reduction of the emission factors [48]. An average of 3.593,7 t/ship of maritime transport is maintained despite the increase in its managed cargo by 18%, guaranteeing his efficiency. 65% of its emissions are due to anchoring and only 30% to berthing. However, the times of these operations have been reduced by 75,3 and 7,2%, respectively. In addition, the percentage of ships in anchoring have reduced from 68,8 to 37,5%, demonstrating improvements in its efficiency from a logistical point of view. On average, the anchoring time and emissions from this terminal account for approximately 46,5%, a similar value to berthing. To reduce the carbon footprint, increasing efficiency in the logistics of ship waiting times and implementing measures for the auxiliary engines can be effective.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AJPS | Jurisdiction Area of the Port of Sines | LNG | Liquefied Natural Gas |

| APA | Portuguese Environment Agency | MARPOL | International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships |

| APS | Administration of the Ports of Sines and Algarve, SA | MEPC | Marine Environment Protection Committee |

| CII | Carbon intensity indicator | NGT | Natural Gas Terminal |

| EEA | European Environment Agency | PCT | Petrochemical Terminal |

| EEDI | Energy Efficiency Design Index | PLF | Passenger Locator Forms |

| PM | Particulate material | ||

| EEXI | Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index | ro_ro | roll-on/roll-off |

| EU | European Union | OILPOL | Convention for the Prevention of Pollution of the Sea by Oil |

| GCT | General Cargo Terminal | SBT | Solid Bulk Terminal |

| GDP | Gross domestic product | SCT | Sine’s Container Terminal |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas | SEEMP | Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan |

| IAPH | International Association of Ports and Harbors | TTW | Tank to Wheel |

| IMO | International Maritime Organization | VOC | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| JUL | Logistics Single Window | ZALSINES | Port and Industrial and Logistics Zone of Sines |

| JUP | Single Port Window | ZILS | Sines Industrial and Logistics Zone |

| LBT | Liquid Bulk Termina |

References

- EU. Regulation 2015/757 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Official Journal of the European Union 2015, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2015/757/oj/eng.

- EU. The European Green Deal of the 2020 2020, https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en.

- EU. Commission welcomes completion of key ‘Fit for 55’ legislation, putting EU on track to exceed 2030 targets 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_4754.

- FDFA. International Convention for the prevention of pollution from ships (MARPOL). Flanders Chancellery and Foreign Office 1973, https://fdfa.be/en/international-convention-for-the-prevention-of-pollution-from-ships-marpol.

- Sáez, P. From maritime salvage to IMO 2020 strategy: Two actions to protect the environment. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2021, 170, 112590. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y. Regulation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from International Shipping and Jurisdiction of States. Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law 2016, 25, 3, 273-401.

- IMO. Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC). https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/MeetingSummaries/Pages/MEPC-default.aspx.

- Baumann, J. From global to human factors: Shipping emissions policy process in the IMO. Marine Policy 2024, 167,106291. [CrossRef]

- Pigani, L; Boscolo, M; Pagan, N. Marine refrigeration plants for passenger ships: Low-GWP refrigerants and strategies to reduce environmental impact. International Journal of Refrigation 2016, 64, 80-92. [CrossRef]

- NU. International Convention for the prevetion of pollution for ship. No. 22484 1978, https://treaties.un.org/pages/showDetails.aspx?objid=0800000280291139.

- EPA. Guidance Documents related to Annex VI Standards for Marine Diesel Engines and Fuel 2024, https://www.epa.gov/regulations-emissions-vehicles-and-engines/guidance-documents-related-annex-vi-standards-marine.

- Roy, W; Sheldeman, K; Nieuwenhove, A; Merveille, J; Schallier R; Maes, F. Current progress in developing a MARPOL Annex VI enforcement strategy in the Bonn Agreement through remote measurements. Marine Policy 2023, 158, 105882. [CrossRef]

- IMO. Resolution MEPC.304 (72). Initial imo strategy on reduction of GHG emissions from ships 2018, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/KnowledgeCentre/IndexofIMOResolutions/MEPCDocuments/MEPC.304(72).pdf.

- Winnes, H; Styhre, L; Fridell, E. Reducing GHG emissions from ships in port areas. Research in Transportation Business & Management 2015, 17,73-82. [CrossRef]

- Fenton, P. The role of port cities and transnational municipal networks in efforts to reduce green house gas emissions on land and at sea from shipping – An assess mentof the World Ports Climate Initiative. Marine Policy 2017, 75, 271-277. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H; Hu, Z; Leung, T. Carbon emissions reduction in China’s container terminals: Optimal strategy formulation and the influence of carbon emissions trading. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 219, 518-530. [CrossRef]

- Barberi, S; Sambito, M; Neduzha y A. Severino. Pollutant Emissions in Ports: A Comprehensive Review. Infrastructures 2021, 6, 114, 1-36. [CrossRef]

- Alamoush, A; Olcer, A; Ballini, F. Port greenhouse gas emission reduction: Port and public authorities’ implementation schemes. Research in Transportation Business & Management 2022, 43, 100708. [CrossRef]

- Winnes, H; Styhre, L; Fridell, E. Reducing GHG emissions from ships in port areas. Research in Transportation Business & Management 2015, 17, 73-82. [CrossRef]

- EU. Monitoring, reporting and verification of EU ETS emissions 2021, https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/eu-emissions-trading-system-eu-ets/monitoring-reporting-and-verification-eu-ets-emissions_en.

- Coelho, M; Mesquita, J; Macedo, E; Macedo, J. Decarbonising mobility in port cities. Transportation Research Procedia 2024, 78, 304-310. [CrossRef]

- Oloruntobi, O; Kasypi, M; Gohari, A; Saira, A; Chuah, L. Sustainable transition towards greener and cleaner seaborne shipping industry: Challenges and opportunities. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 2023, 231, 100628. [CrossRef]

- Styhre, L; Winnes, H; Black, J; Lee, J; Le-Griffin, H. Greenhouse gas emissions from ships in ports – Case studies in four continents. Transportation Research Part D 2017, 54, pp. 212-224. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C; Huang, H; Liu, Z; Ding, Y; Xiao, J; Shu, Y. Identification and analysis of ship carbon emission hotspots based on data field theory: A case study in Wuhan Port. Ocean & Coastal Management 2023, 235, 106479. [CrossRef]

- Mocerino, F; Murena, F; Quaranta, F; Toscano, D. Validation of the estimated ships’ emissions through an experimental campaign in port. Ocean Engineering 2023, 288, 115957. [CrossRef]

- Akakura, Y. Analysis of offshore waiting at world container terminals and estimation of CO2 emissions from waiting ships. Asian Transport Studies, 9, 100111, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Aseel, S; Al-Yafei, H; Kucukvar, M; Onat, N; Turkay, M; Kazancoglu, Y; Al-Sulaiati, A; Al-Hajri, A. A model for estimating the carbon footprint of maritime transportation of Liquefied Natural Gas under uncertainty. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2021, 27,1602-1613.

- Azarkamand, S; Wooldridge, C; Darbra, R. Review of Initiatives and Methodologies to Reduce CO2 Emissions and Climate Change Effects in Ports. International journal of environmental research and public health 2022, 17, 11, 3858. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W; Huynh, N; Quoc, T; Yu, H. An assessment model of eco-efficiency for container terminals within a port. Economics of Transportation 2024, 39. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, D; Gervásio, H. The challenge of benchmarking carbon emissions in maritime ports. Environmental Pollution 2024, 363, Pat 2, 125170. [CrossRef]

- DGPM. Direcao-Geral de Política do Mar 2023, https://www.dgpm.mm.gov.pt/conta-satelite-do-mar.

- Winnes, H; Styhre, L; Fridell, E. Reducing GHG emissions from ships in port areas. Research in Transportation Business & Management 2015, 17, 73-82. [CrossRef]

- Fenton, P; The role of port cities and transnational municipal networks in effort storeduce greenhousegas emissions on landandat sea from shipping – An assessmen tof the World Ports Climate Initiative. Marine Policy 2017, 75, 271-277. [CrossRef]

- Fadiga, A; Ferreira, L; Bigotte, J. Decarbonising maritime ports: A systematic review of the literature and insights for new research opportunities. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 452, 142209. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, R; Alvim-Ferraz, M; Martins, F; Sousa, S. Local mortality and costs from ship-related emissions in three major Portugueses ports. Urban Climate 2024, 53,101780. [CrossRef]

- Kazimieras, E; Turskis, Z; Bagocius, V. Multi-criteria selection of a deep-water port in the Eastern Baltic Sea. Applied Soft Computing 2015, 26, 180-192. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moya, J; Mestre-Alcover, M; Sala-Garrido, R; Furió-Pruñonosa, S. Are transhipment ports more efficient in the Mediterranean Sea? Analysing the role of time at ports using DEA metafrontier approach. Journal of Transport Geography 2024, 116, 103866. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H; Yan, Q; Yang, Y; Wang, S; Yuan, Q; Li, X; Mei, Q. Spatial classification model of port facilities and energy reserve prediction based on deep learning for port management―A case study of Ningbo. Ocean and Coastal Management 2024, 258, 107413. [CrossRef]

- APS. Port of Sines/Statictics 2025, https://www.apsinesalgarve.pt/en/statistics/monthly-statistics/port-of-sines/.

- GloMEEP, gef, UNDP, IMO, IAPH. Port Emissions Toolkit, Guide No.1 – GloMEEP 2018, http://chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://glomeep.imo.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/port-emissions-toolkit-g1-online_New.pdf.

- Osorio-Tejada, J; Llera Sastresa, E; Scarpellini, S. Environmental assessment of road freight transport services beyond the tank-to-wheels analysis based on LCA. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2024, 26, 421–451. [CrossRef]

- GHGPROTOCOL. Standards & Guidance 2024, https://ghgprotocol.org/standards-guidance.

- GreenVoyage2050, Port Emissions Toolkit Guide No. 1: Assessment of Port 2021.

- Zhao, N; Wang, Z; Ji, X; Fu, H; Wang, Q. Analysis of a maritime transport chain with information asymmetry and disruption risk. Ocean and Coastal Management 2023, 231, 106405. [CrossRef]

- EMSA; EEA. European Maritime Transport Environmental Report 2021. ISBN: 978-92-9480-371-9, https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/maritime-transport.

- APA. Factor de Emissao da Electricidade 2024 Portugal 2024, https://apambiente.pt/clima/fator-de-emissao-de-gases-de-efeito-de-estufa-para-eletricidade-produzida-em-portugal.

- PGLISBOA. DL n.º 158/2019. Janela Única Logística. Ministério Público de Portugal 2019. https://www.pgdlisboa.pt/leis/lei_mostra_articulado.php?nid=3188&tabela=leis&ficha=1&pagina=1&so_miolo=.

- Santos, S; Lima, L; Castelo, M. Corporate sustainability of Portuguese seaports. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 380, 136057. [CrossRef]

- Gil, R; Borges, R; Maritna, A; Macebo, B; Teixeira, L. A Simulation Tool to Forecast the Behaviour of a New Smart Pre-Gate at the Sines Container Terminal, sustainability 2025, 17, 1, 163. [CrossRef]

- Run, S; Abouarghoub, W; Demir, E. Enhancing data quality in maritime transportation: Apractical method for imputing missing ship static data. Ocean Engineering 2025, 315, 119722. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, G; Baptista, P. Promotion of renewable energy sources in the Portuguese transport sector: A scenario analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 180, 918-932. [CrossRef]

- Maia, F; Leitao, S; Corria, M. Energy transition in Portugal: The harnessing of solar photovoltaics in electric mobility and its impact on the carbon footprint. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 477, 143834. [CrossRef]

- Xing, H; Spence, S; Chen, H. A comprehensive review on countermeasures for CO2 emissions from ships,» Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 134, 110222. [CrossRef]

- Arif, M; Rais, M; Shinoda, T. Estimation of CO2 emissions for ship activities at container port as and effort towards a green port index,» Energy Reports 2022, 8, 229-236. [CrossRef]

| Chapter | Ruler | Define |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | Rule 12 | Substances that deplete the ozone layer defined in the Montreal Protocol and your amendments |

| 3 | Rule 13 | Nitrogen oxides (NOx) |

| 3 | Rule 14 | Sulphur oxides (SOx) and particulate matter (PM) |

| 3 | Rule 15 | Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC) |

| 3 | Rule 18 | Fuel oil quality and availability |

| 4 | Rule 22 | Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) obtained |

| 4 | Rule 23 | Energy Efficiency Existing Index (EEXI) obtained |

| 4 | Rule 24 | EEDI prescribed |

| 4 | Rule 25 | EEXI prescribed |

| 4 | Rule 26 | Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP) |

| 4 | Rule 27 | Collection and reporting of the data about the ship ’s fuel oil consumption |

| 4 | Rule 28 | Carbon intensity operational (CII) |

| Cargo Handling | Total (t) | Total (%) |

| Total Charge | 36.608.437 | 100,00 |

| Liquid Bulk | 18.484.960 | 50,49 |

| Dry Bulk | 323.018 | 0,88 |

| General Cargo | 17.800.458 | 48,62 |

| Countries of origin/destination | Total (t) | Total (%) |

| Portugal | 2.508.480 | 6,85 |

| EU Countries | 6.544.333 | 17,88 |

| Other Countries | 27.555.624 | 75,27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).