Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

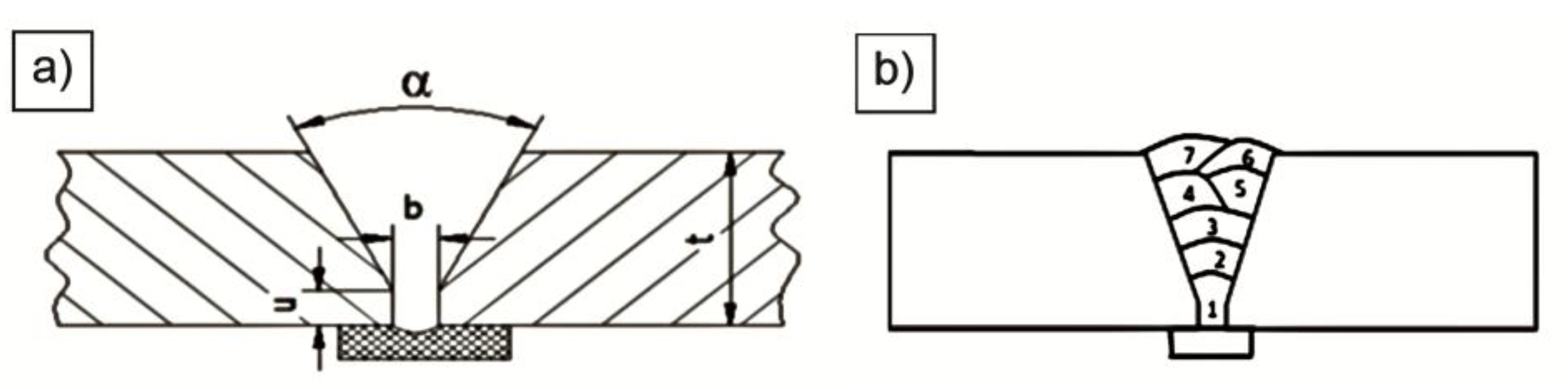

2.1. Material and Welding

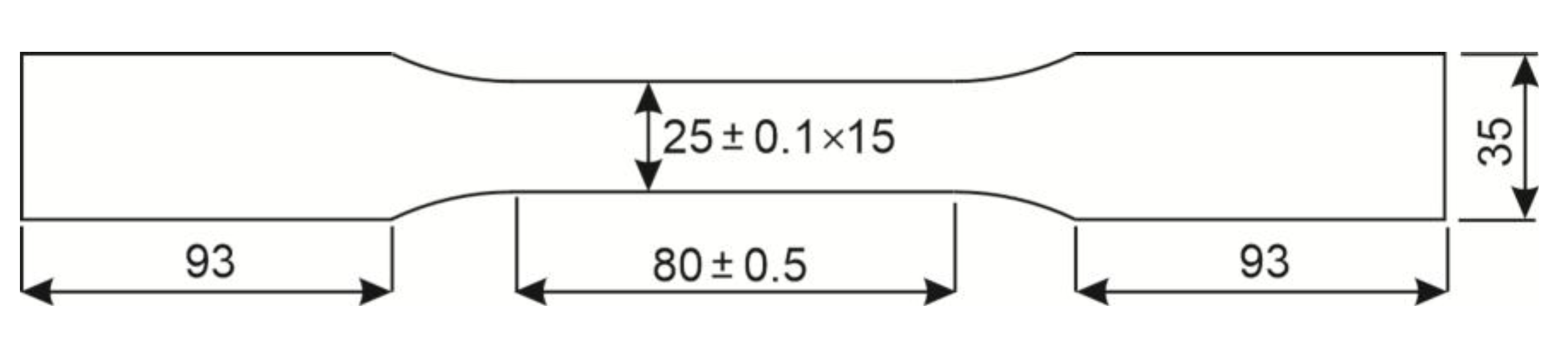

2.2. Tensile Test

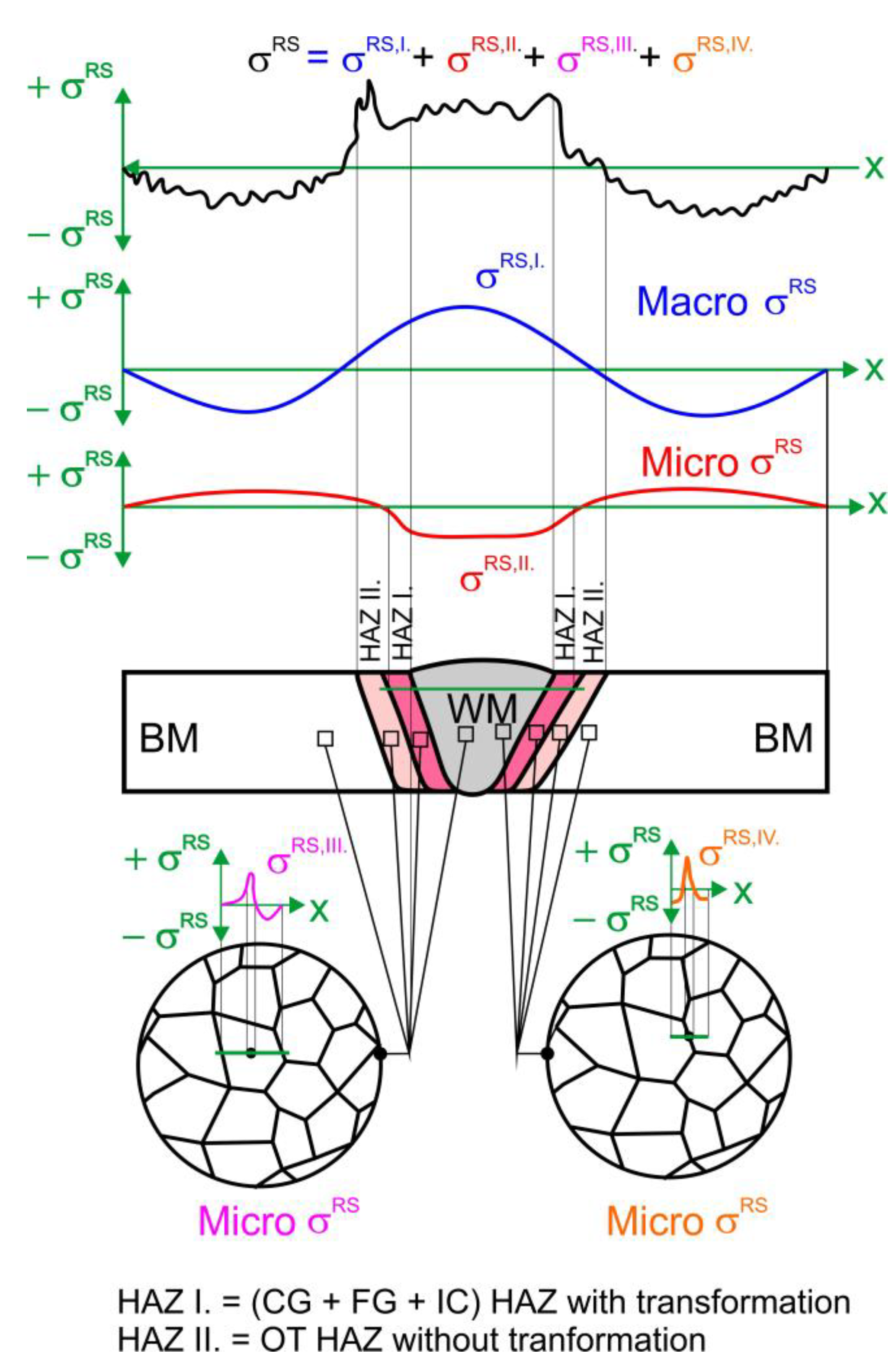

2.3. Residual Stress Measurement

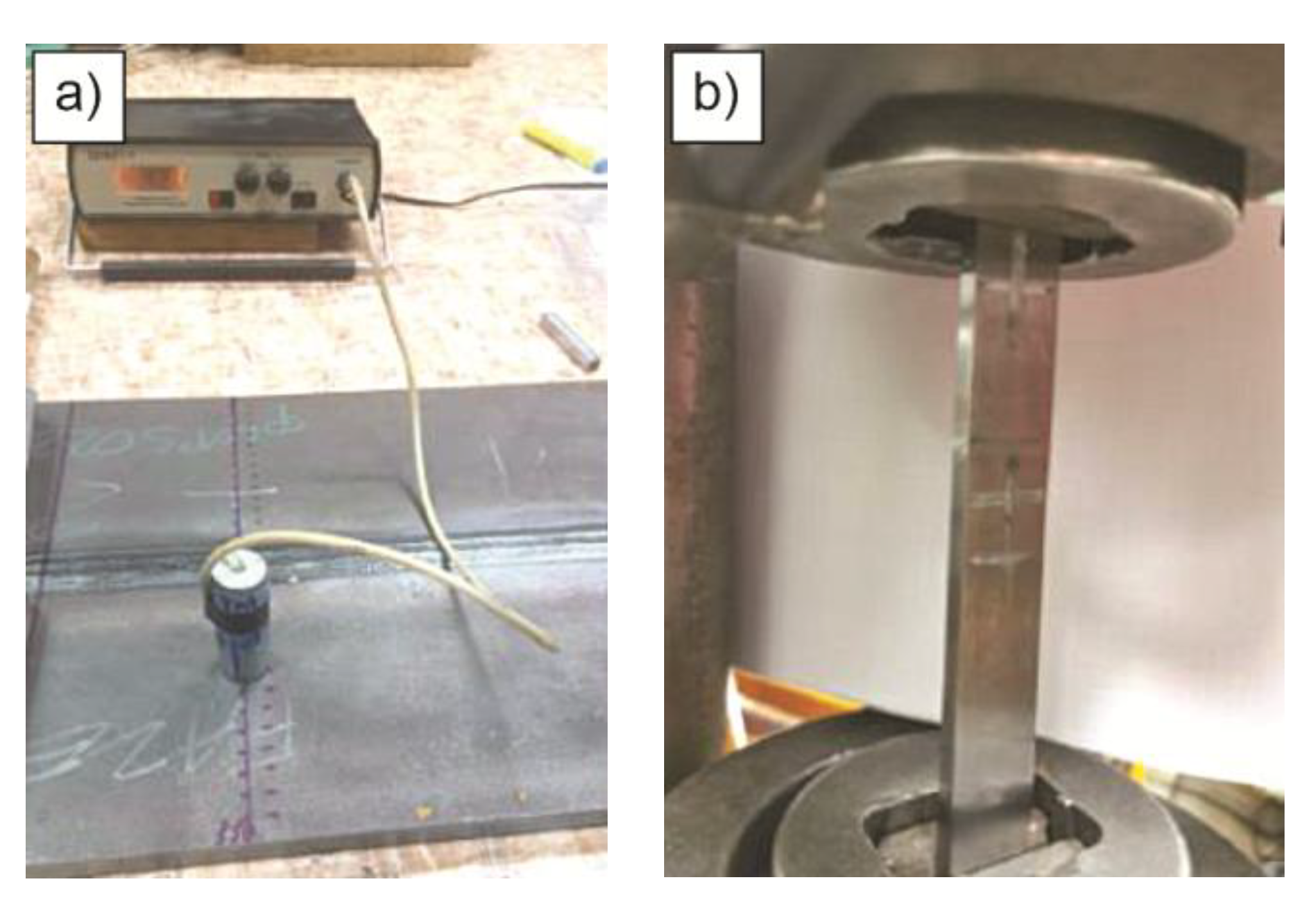

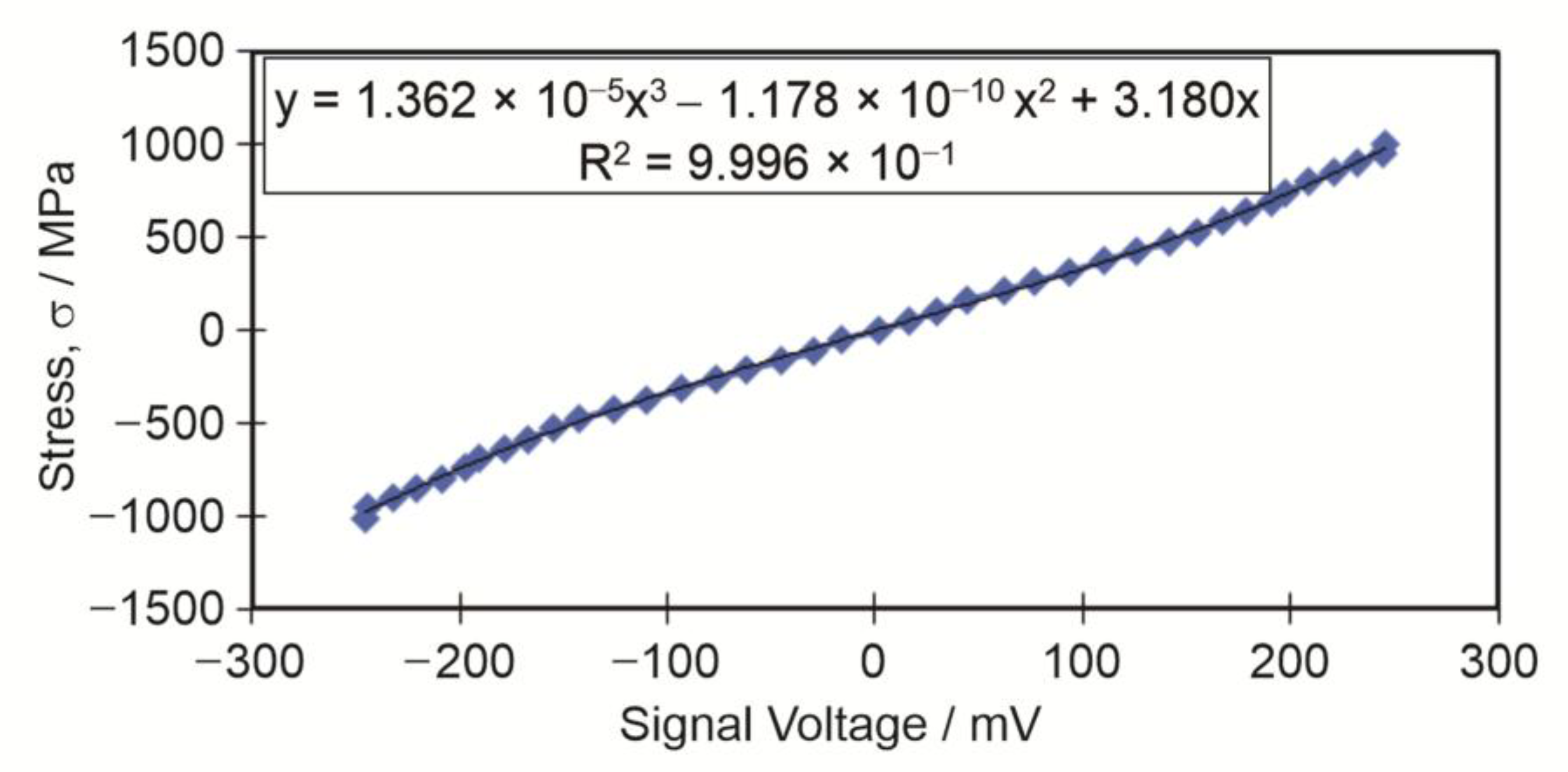

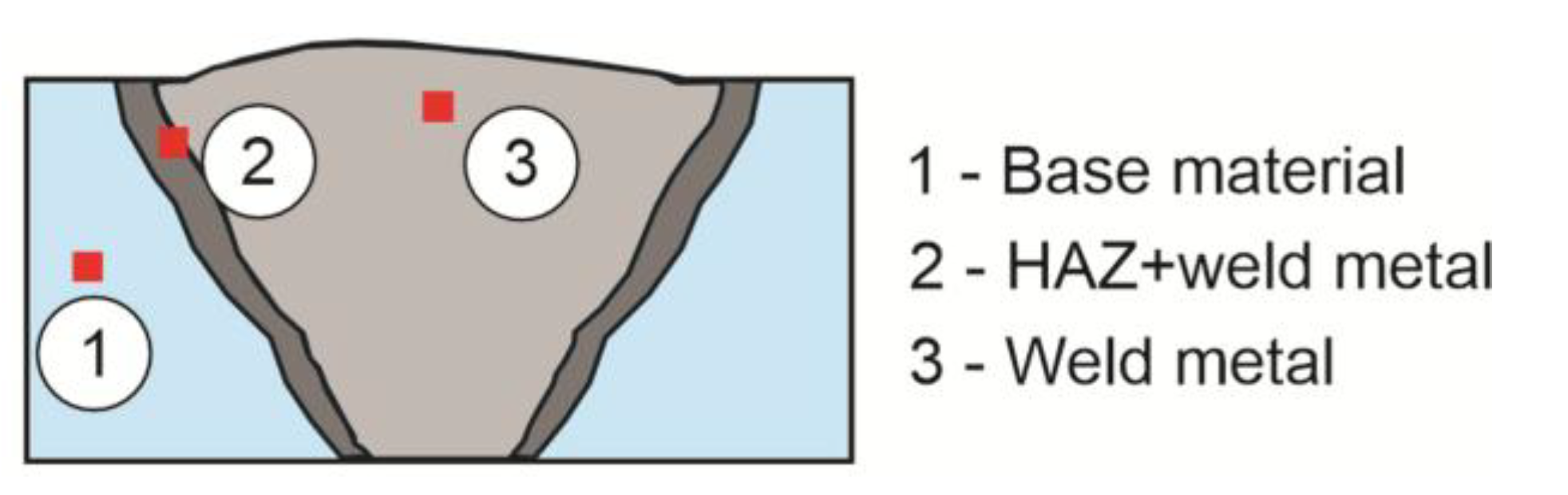

2.3.1. Magnetic Method - MAS

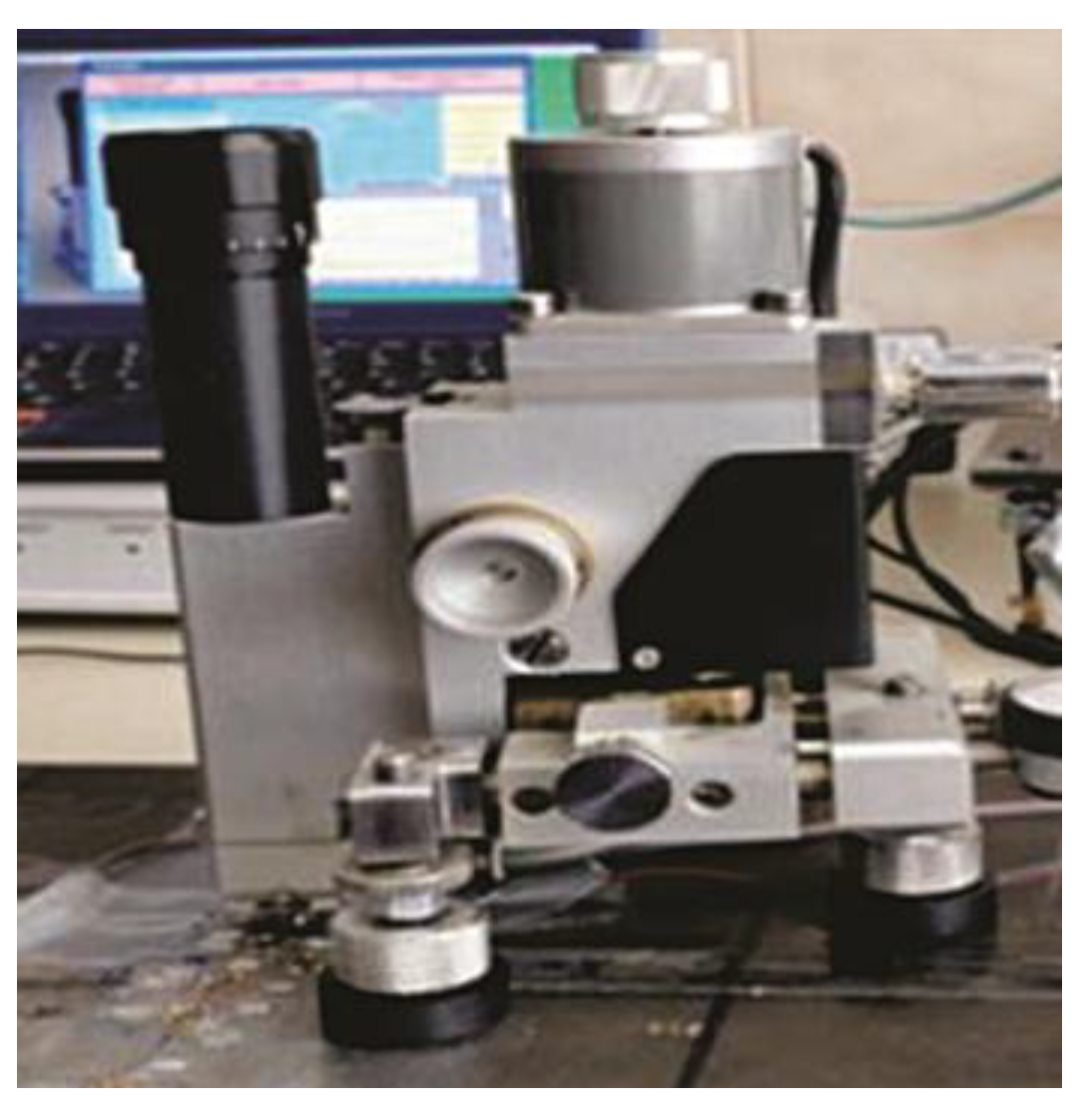

2.3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Method – XRD

2.3.3. Hole Drilling Method – HD

2.4. Optical Microscopy

3. Results

3.1. Tensile Test Results

3.2. Results of Magnetic Method

3.3. Results of X-Ray Diffraction Method

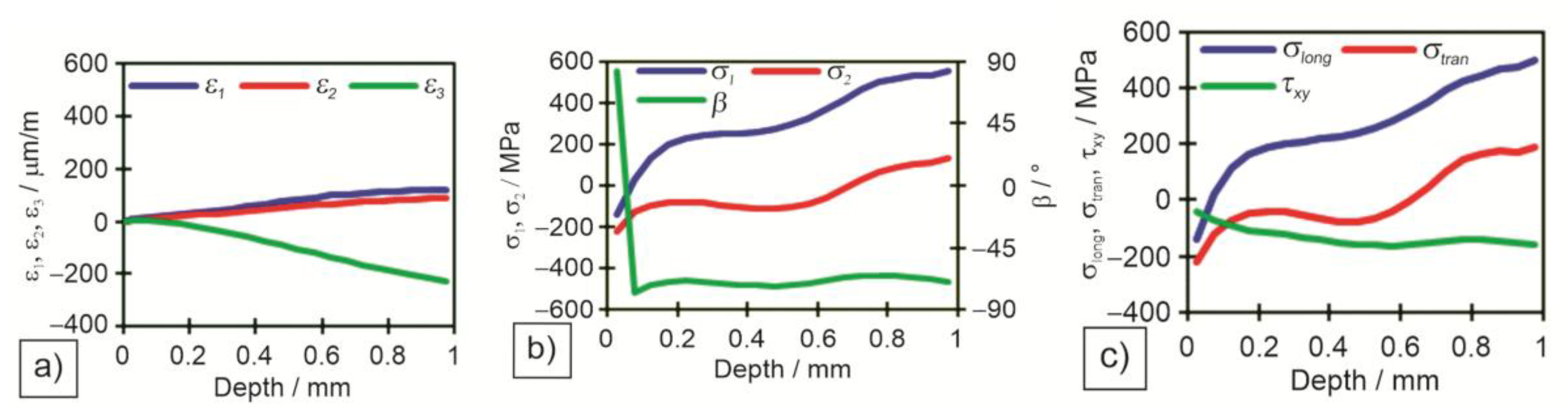

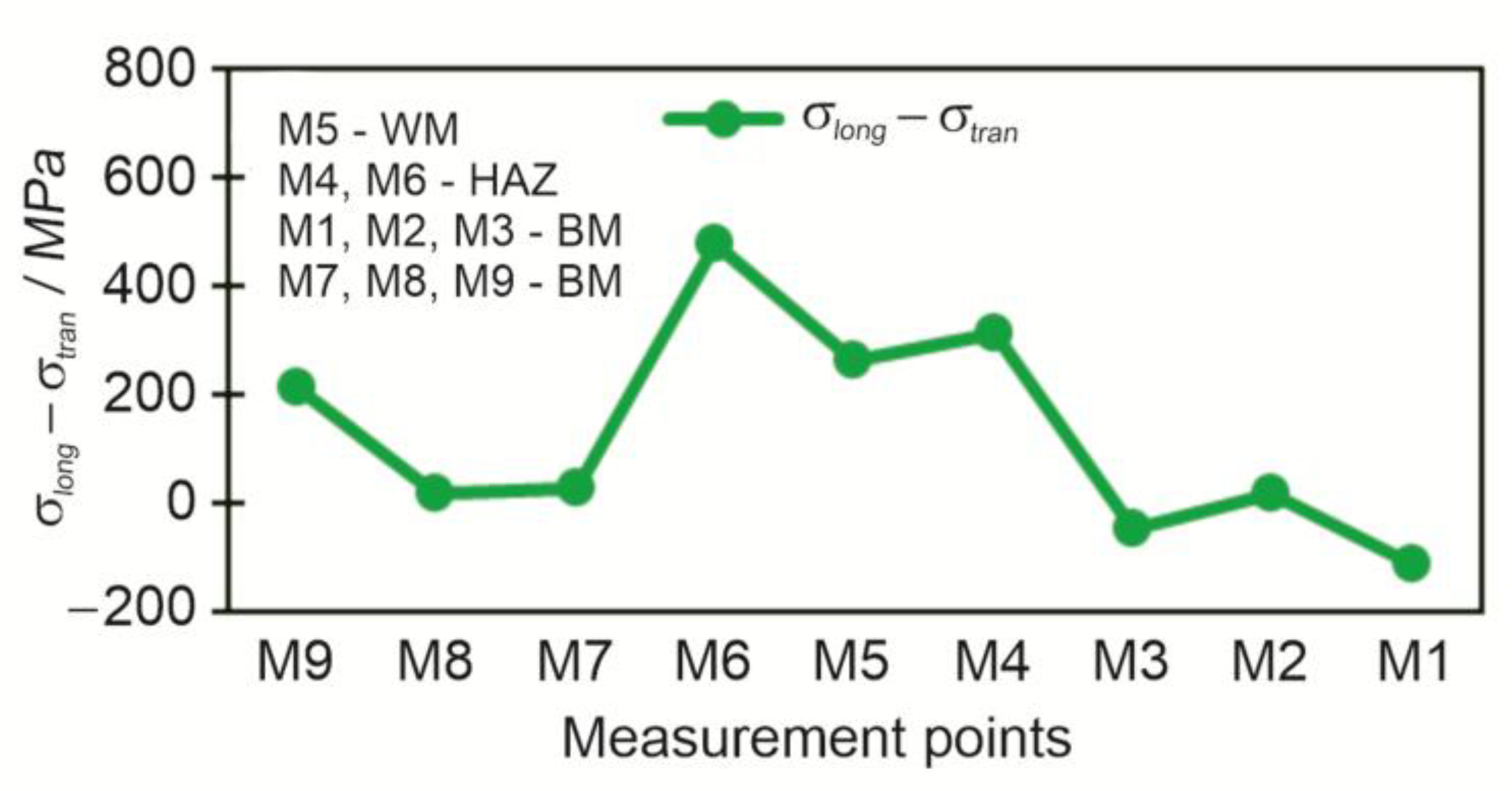

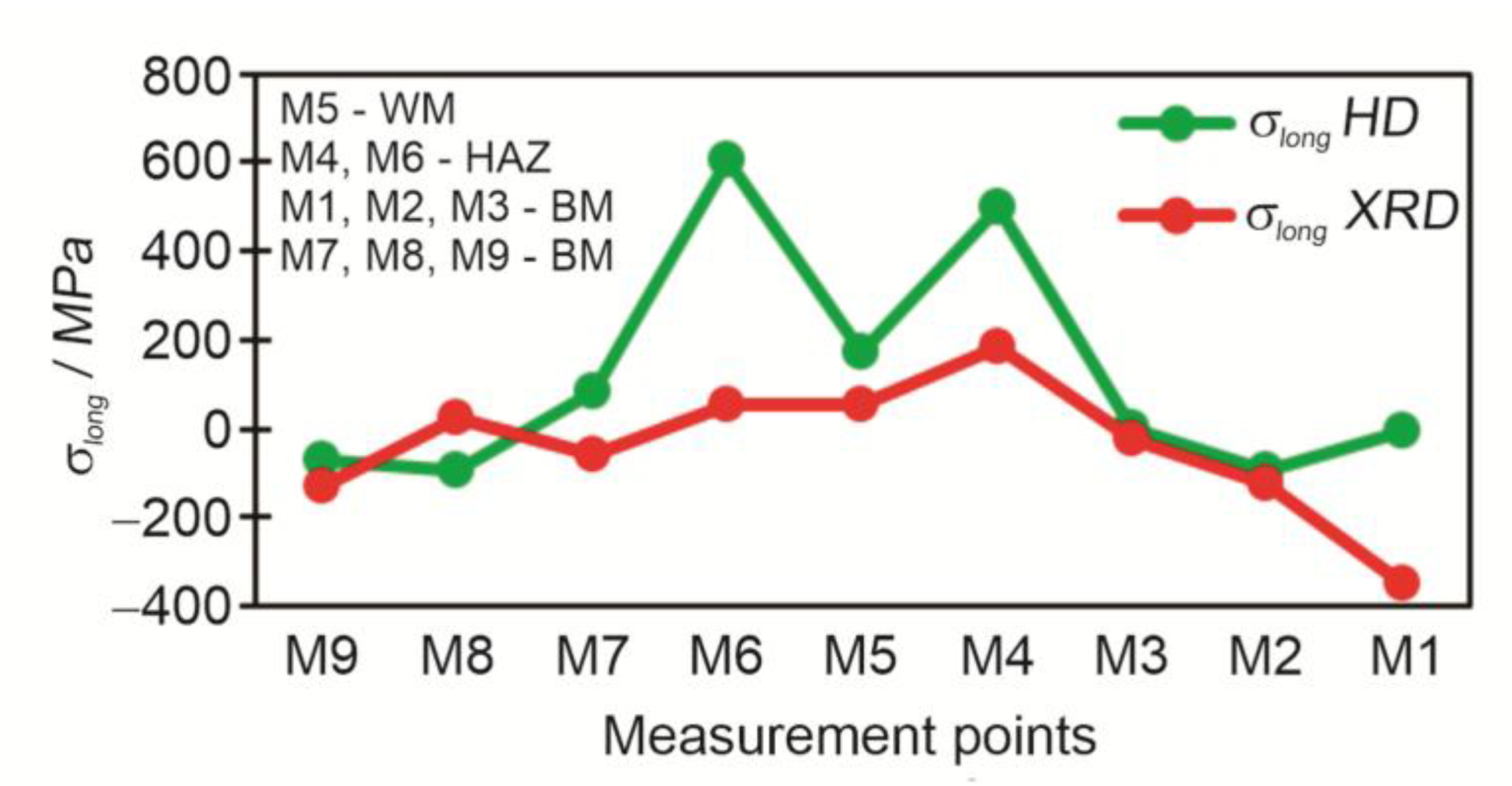

3.4. Results of Hole Drilling Method

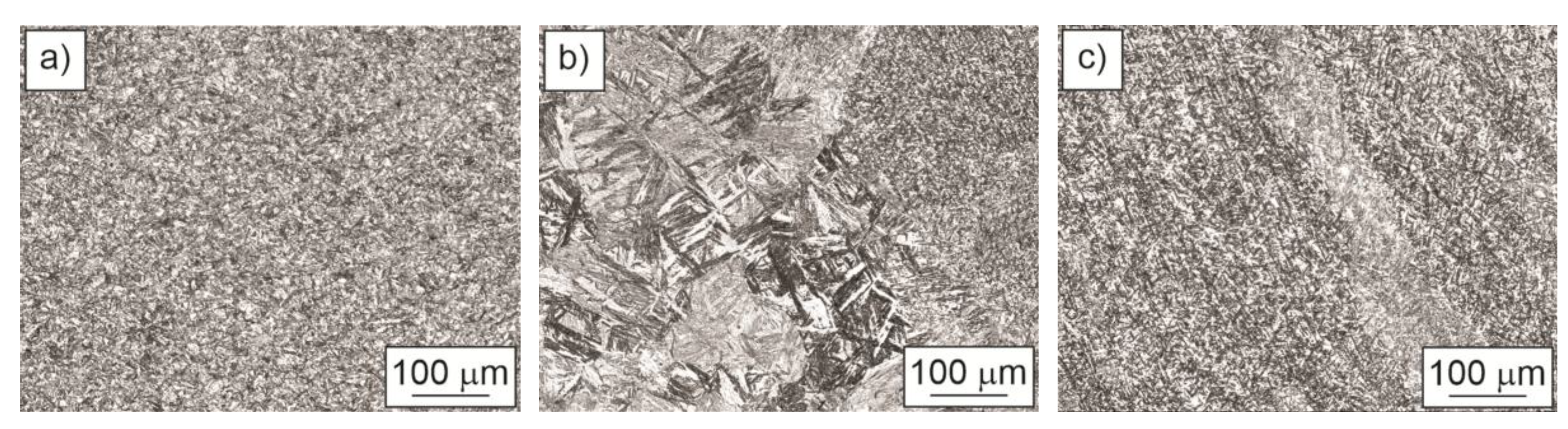

3.5. Microstructure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sisodia, R. P. S.; Gáspár, M., An Approach to Assessing S960QL Steel Welded Joints Using EBW and GMAW. Metals-Basel 2022, 12, (4).

- Lukács, J.; Gáspár, M., Fatigue crack propagation limit curves for high strength steels and their application for engineering critical assessment calculations. Adv Mater Res-Switz 2014, 891-892, 563-568.

- Sága, M.; Blatnická, M.; Blatnicky, M.; Dizo, J.; Gerlici, J., Research of the Fatigue Life of Welded Joints of High Strength Steel S960 QL Created Using Laser and Electron Beams. Materials 2020, 13, (11).

- Hensel, J.; Nitschke-Pagel, T.; Dilger, K.; Schönborn, S., Effects of Residual Stresses on the Fatigue Performance of Welded Steels with Longitudinal Stiffeners. Mater Sci Forum 2014, 768-769, 636-+.

- Schaupp, T.; Schroepfer, D.; Kromm, A.; Kannengiesser, T. Welding Residual Stress Distribution of Quenched and Tempered and Thermo-Mechanically Hot Rolled High Strength Steels. Residual Stresses Ix 2014, 996, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türker, M. The Effect of Welding Parameters on Microstructural and Mechanical Properties of HSLA S960QL Type Steel with Submerged Arc Welding. Journal of Natural and Applied Sciences 2017, 21, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gáspár, M.; Balogh, A. GMAW experiments for advanced (Q+T) high strength steels. Production Processes and Systems 2013, 6, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Madej, K.; Jachym, R. Welding of High Strength Toughened Structural Steel S960QL. Materials Science and Welding Technologies 2017, 2017, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubnell, J.; Carl, E.; Farajian, M.; Gkatzogiannis, S.; Knödel, P.; Ummenhofer, T.; Wimpory, R. C.; Eslami, H. Residual stress relaxation in HFMI-treated fillet welds after single overload peaks. Welding in the World 2020, 64, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- companies, S. g. o. STRENX® Performace Steel - STRENX® 960 E/F https://www.ssab.com/api/sitecore/Datasheet/Get?key=59e738903b6247a3b68df07d49f40239_en (2025-01-27).

- AG, T. STRENX® Performace Steel - STRENX® 960 E/F https://www.thyssenkrupp-steel.com/media/content_1/publikationen/produktinformationen/gbq/april_2021/gbq-0055-s960ql-tkse-cpr-01042021.pdf (2025-01-27).

- Goss, C.; Marecki, P.; Grzelak, K. Fatigue life of S960QL steel welded joints. Biuletyn WAT 2014, 63, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensel, J.; Nitschke-Pagel, T.; Rebelo-Kornmeier, J.; Dilger, K. Experimental investigation of fatigue crack propagation in residual stress fields. Procedia Engineer 2015, 133, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garstka, T.; Szota, P.; Mroz, S.; Stradomski, G.; Grobarczyk, J.; Gryczkowski, R., Calibration Method of Measuring Heads for Testing Residual Stresses in Sheet Metal Using the Barkhausen Method. Materials 2024, 17, (18).

- Withers, P. J.; Bhadeshia, H. K. D. H., -: Residual stress part 1 -: Measurement techniques. Mater Sci Tech-Lond 2001, 17, (4), 355-365.

- ossini, N. S.; Dassisti, M.; Benyounis, K. Y.; Olabi, A. G., Methods of measuring residual stresses in components. Materials & Design 2012, 35, 572-588.

- Salvati, E.; Korsunsky, A. M. An analysis of macro- and micro-scale residual stresses of Type I, II and III using FIB-DIC micro-ring-core milling and crystal plasticity FE modelling. Int J Plasticity 2017, 98, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaissa, M. A. A.; Asmael, M.; Zeeshan, Q. Recent Applications of Residual Stress Measurement Techniques for FSW Joints: A Review. J Kejuruter 2020, 32, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabul, E.; Lunt, A. J. G., A Novel Low-Cost DIC-Based Residual Stress Measurement Device. Appl Sci-Basel 2022, 12, (14).

- Kandil, F.A; Lord, J.D; Fry, A.T; Grant, P.V. A Review of Residual Stress Measurement Methods - A Guide to Technique Selection; NFL Report MATC(A)O4; National Physical Laboratory, Teddington - Materials Centre: Teddington, Middlesex, UK, 2001; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Fu, H. Y.; Pan, B.; Kang, R. K. Recent progress of residual stress measurement methods: A review. Chinese J Aeronaut 2021, 34, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminforoughi, B.; Degener, S.; Richter, J.; Liehr, A.; Niendorf, T., A Novel Approach to Robustly Determine Residual Stress in Additively Manufactured Microstructures Using Synchrotron Radiation. Adv Eng Mater 2021, 23, (11).

- Pardowska, A.M.; Price, J.W.H.; Finlayson, T.R. Poređenje tehnika merenja zaostalih napona primenjljivih na zavarenim čeličnim delovima, Comparison Of Residual Stress Measurements Techniques Applicable To The Steel Welded Components (in translation). Zavarivanje i zavarene konstrukcije, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, S.; Violatos, I. Comparison Between Surface and Near-Surface Residual Stress Measurement Techniques Using a Standard Four-Point-Bend Specimen. Exp Mech 2022, 62, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schajer, G. S.; Prime, M. B.; Withers, P. J. Why Is It So Challenging to Measure Residual Stresses ? Exp Mech 2022, 62, 1521–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM International, ASTM E837-20 - Standard Test Method for Determining Residual Stresses by the Hole-Drilling Strain-Gage Method. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, 19428-2959 USA 2020; pp 1-16.

- Deveci, M. Stresstech Bulletin 12: Measurement Methods of Residual Stresses. https://www.stresstech.com/stresstech-bulletin-12-measurement-methods-of-residual-stresses/ (2025-01-23).

- Yang, Y. P.; Dull, R.; Huang, T. D.; Rucker, H.; Harbison, M.; Scholler, S.; Zhang, W.; Semple, J., Development of Weld Residual Stress Measurement Method for Primed Steels. Proceedings of the Asme Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference, 2017, Vol 6b 2017.

- Wang, Z. Y.; Zhou, H. B.; Zhou, W. W.; Li, Z. Q.; Ju, X.; Peng, Y. C.; Duan, J. A. Experimental and numerical investigation of residual stress and post-weld-shift of coaxial laser diodes during the optoelectronic packaging process. Welding in the World 2023, 67, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engineering Principles-Welding and Residual Stresses. Cooke, K., Cozza, R., C., Ed. IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2022; p 338.

- Schajer, G. S.; Whitehead, P. S. Hole Drilling and Ring Coring. Practical Residual Stress Measurement Methods 2013, 29–64. [Google Scholar]

- The European Committee for Standardization, EN 15305:2008: Non-destructive Testing - Test Method for Residual Stress analysis by X-ray Diffraction. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2008; pp 1-85.

- ASTM International, ASTM E2860-20 - Standard Test Method for Residual Stress Measurement by X-Ray Diffraction for Bearing Steels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, 19428-2959 USA 2020; pp 1-19.

- Yang, Y. P.; Huang, T. D.; Rucker, H. J.; Fisher, C. R.; Zhang, W.; Harbison, M.; Scholler, S. T.; Semple, J. K.; Dull, R. Weld Residual Stress Measurement Using Portable XRD Equipment in a Shipyard Environment. J Ship Prod Des 2019, 35, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technical note TN-503-6: Measurement of Residual Stresses by the Hole-Drilling Strain Gage Method; Vishay Precision Group, Micro-Measurements: North Carolina, USA, 2010; pp. 19–33.

- Belassel, M. Residual Stress Measurement using X-Ray Diffraction Techniques, Guidelines and Normative Standards. SAE International journal of meterials and manufacturing 2012, 5, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, M.; Khan, S. M. A.; El Rayes, M. M.; Seikh, A. H. Evaluation of residual stresses present in spirally welded API grade pipeline steel using the hole drilling method. Mater Test 2017, 59, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, W.; Woo, I.; Mikami, Y.; An, G., Residual Stress Characteristics in Spot Weld Joints of High-Strength Steel: Influence of Welding Parameters. Appl Sci-Basel 2024, 14, (24).

- Wang, L. T.; Xu, C. J.; Feng, L. B.; Wang, W. J. A Survey of the Magnetic Anisotropy Detection Technology of Ferromagnetic Materials Based on Magnetic Barkhausen Noise. Sensors-Basel 2024, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Besevic, M. Experimental investigation of residual stresses in cold formed steel sections. Steel Compos Struct 2012, 12, 465–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttle, D., J.; Moorthy, V.; Shaq, B. A National Measurement Good Practice Guide No. 88 - Determination of Residual Stresses by Magnetic Methods; National Physical Laboratory: Teddington, UK, 2006; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Islamović, F.; Gačo, D.; Hodžić, D. ; E., B., Determination of Stress-Strain State on Elements of Cylindrical Tank Structure. In th scientific conference on defensive technologies OTEH 2020, Lisov M., R. L., Ed. The Military Technical Institute, Ratka Resanovića: Belgrade, Serbia, 2020; pp 429-435.

- Suominen, L.; Khurshid, M.; Parantainen, J. Residual stresses in welded components following post-weld treatment methods. Fatigue Design 2013, International Conference Proceedings 2013, 66, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghawendra, P. S. S.; Gáspár, M.; Sepsi, M.; Mertinger, V. Dataset on full width at half maximum of residual stress measurement of electron beam welded high strength structural steels (S960QL and S960M) by X-ray diffraction method. Data Brief 2021, 38. [Google Scholar]

- The European Committee for Standardization, EN 10025-6:2019+A1:2023: Hot rolled products of structural steels - Part 6: Technical delivery conditions for flat products of high yield strength structural steels in the quenched and tempered condition. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2023; pp 1-28.

- The European Committee for Standardization, EN ISO 4063:2023: Welding, brazing, soldering and cutting - Nomenclature of processes and reference numbers. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2023; pp 1-25.

- International Organization for Standardization, ISO 16834:2012-Welding consumables — Wire electrodes, wires, rods and deposits for gas shielded arc welding of high strength steels — Classification. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012; pp 1-14.

- The European Committee for Standardization, EN 1011-2:2001: Welding - Recommendations for welding of metallic materials - Part 2: Arc welding of ferritic steels. The European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2001; pp 1-57.

- The European Committee for Standardization, EN ISO 6892-1:2019: Metallic materials - Tensile testing - Part 1: Method of test at room temperature. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2019; pp 1-87.

| Element – Mass fraction / wt. % | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C – 0.174 | B – 0.0027 | Cr – 0.623 | N – 0.0015 | Ti – 0.002 |

| Si – 0.297 | P – 0.007 | Cu – 0.043 | Nb – 0.027 | V – 0.002 |

| Mn – 1.070 | S – 0.0017 | Mo – 0.612 | Ni – 0.052 | Zr – 0.001 |

| Thickness / mm | Rp0.2 / MPa | Rm / MPa | A / % | KV / J |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15.0 | 1014 | 1049 | 13 | 150, 153, 156 (- 40⁰C, long.) |

| 1024 | 1060 | 13 | 45, 43, 49 (- 40⁰C, tran.) |

| Element – Mass fraction / wt. % | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Mo | Ni | V | Cu | Ti | Al | Zr |

| 0.09 | 0.78 | 1.79 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.36 | 0.70 | 2.15 | <0.01 | 0.04 | 0.06 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Welding process: MAG – 135 according to EN ISO 4063:23; filler wire diameter φ=1 mm; current DC+ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Welding current / A | 208 | 230 | 240 | 240 | 252 | 258 | 266 |

| Welding Voltage / V | 27.5 | 26.5 | 26.8 | 26.8 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| Wire Speed / m∙min-1 | 10.7 | 11.5 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 14.3 | 16 |

| Travel Speed / cm∙min-1 | 40 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 35 | 34 | 30 |

| Heat Input / kJ∙cm-1 | 6.8 | 7.6 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 9.6 | 10.5 | 12.7 |

| Shielding gas / l∙min-1 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Preheating / ⁰C | 100 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Max. Interpass T / ⁰C | - | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 |

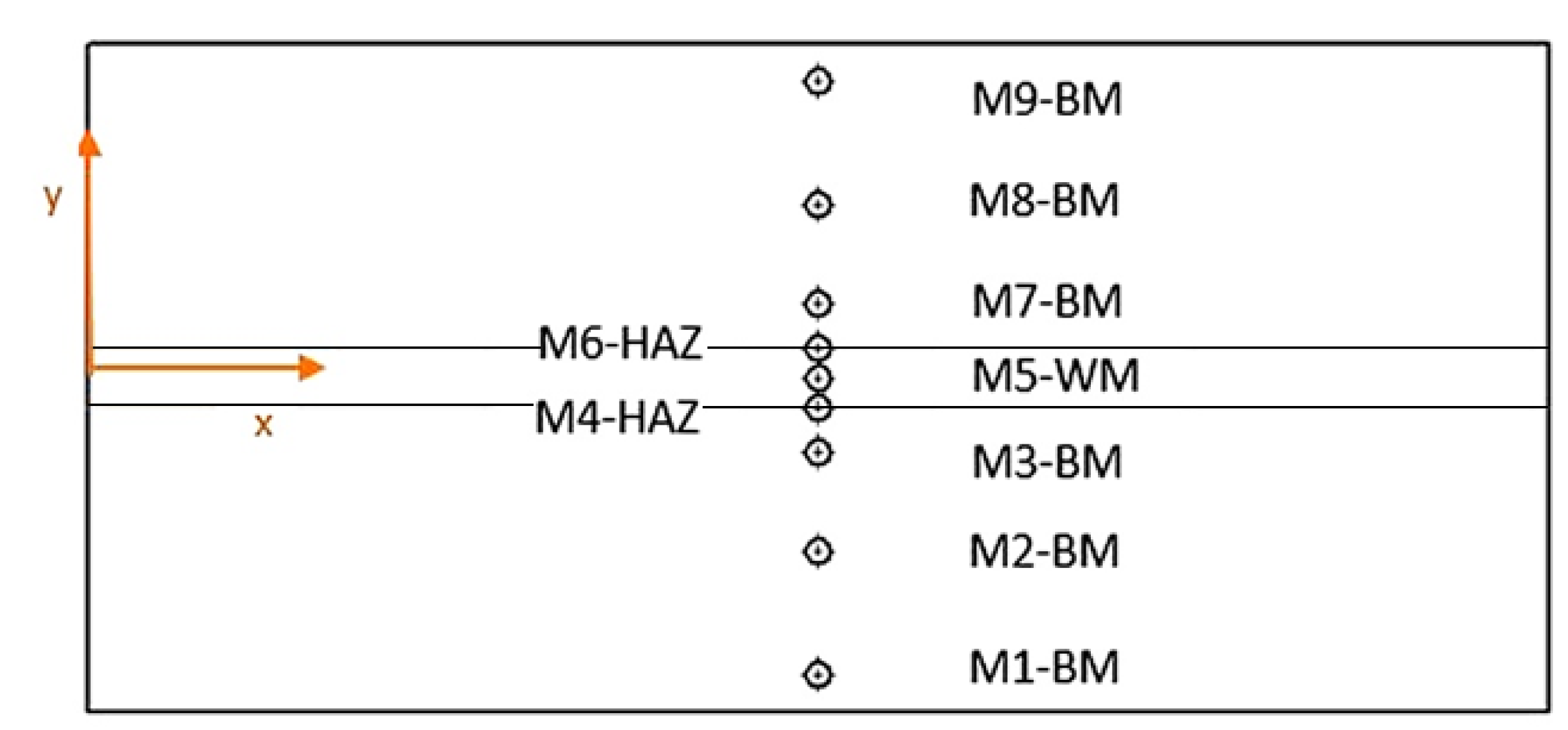

| Location | X / mm | Y / mm | Area in the weld joint* |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 350 | -120 | BM |

| M2 | 350 | -70 | BM |

| M3 | 350 | -30 | BM |

| M4 | 350 | -14 | HAZ |

| M5 | 350 | 0 | WM |

| M6 | 350 | +14 | HAZ |

| M7 | 350 | +30 | BM |

| M8 | 350 | +70 | BM |

| M9 | 350 | +120 | BM |

| Specimen | Measured tensile strength Rm / N/mm2 |

Reduction of area Z / % |

Tensile strength of the base metal Rmp / N/mm2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| TT-1 | 1025 | 39 | 980-1150* |

| TT-2 | 1038 | 33 | 980-1150* |

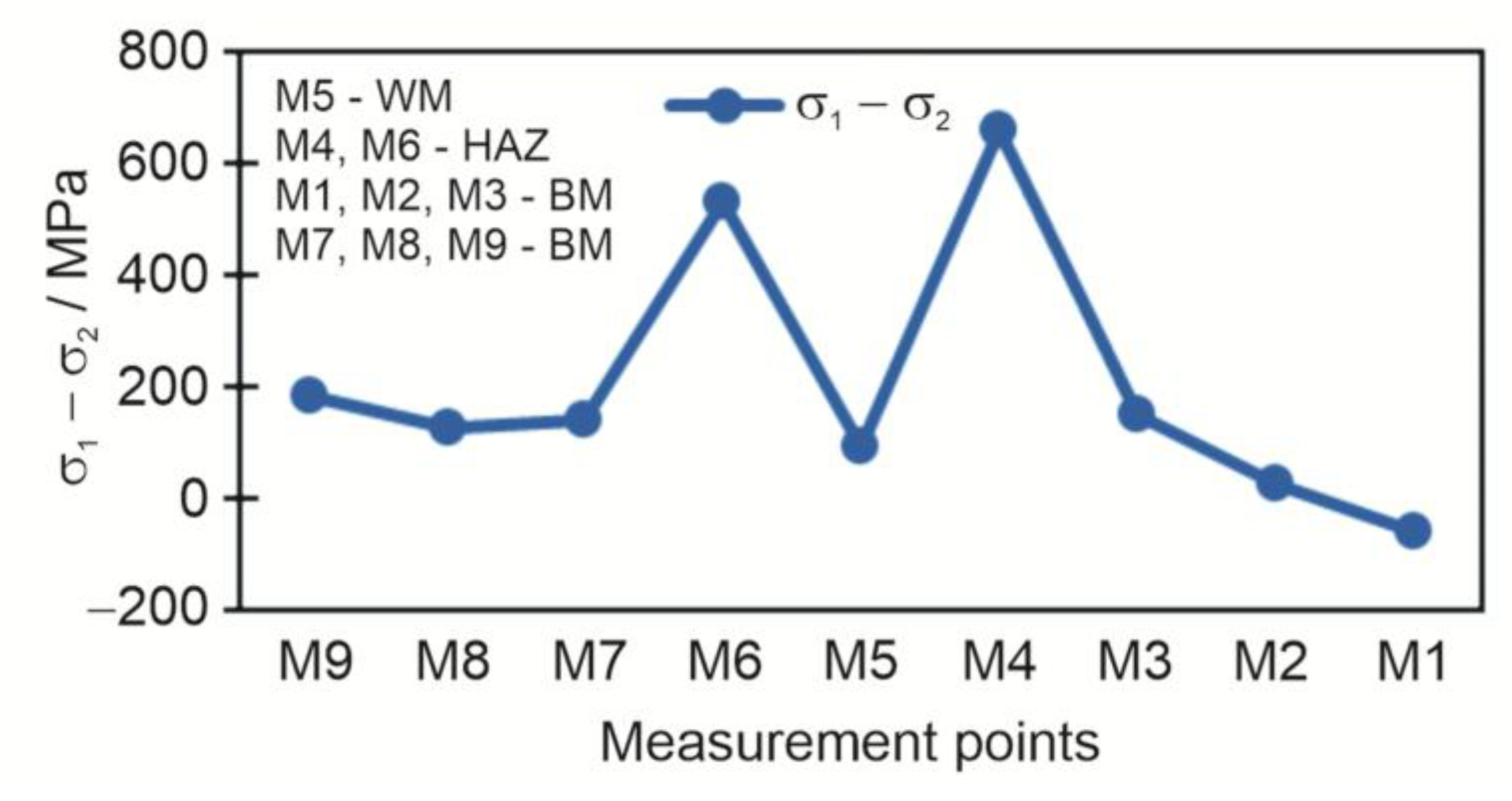

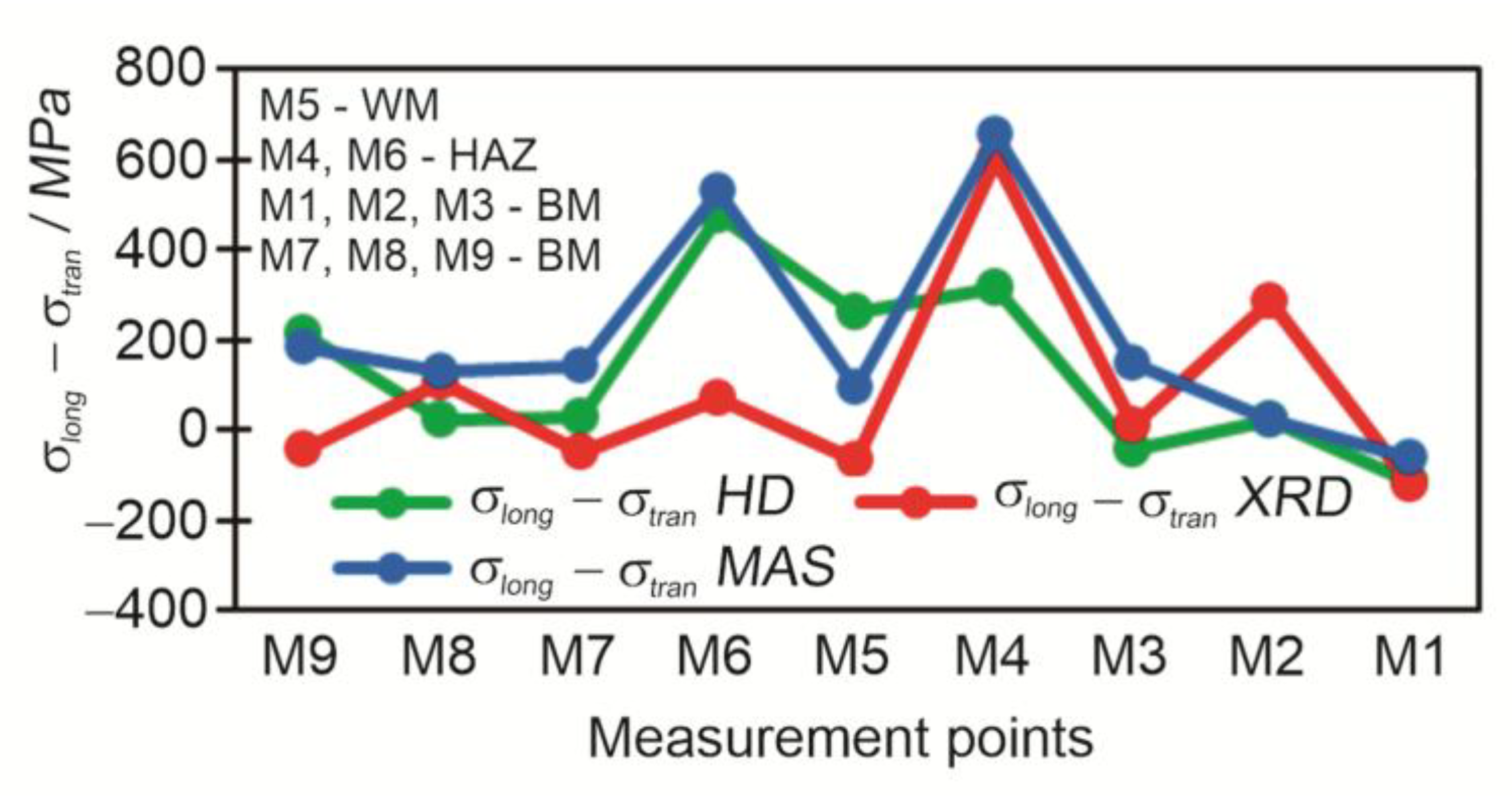

| Measurement point | Signal σ1 – σ2 / mV |

Subtraction of principal stresses σ1 – σ2 / MPa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M9 | BM | 57.6 | 185 |

| M8 | BM | 39.7 | 127 |

| M7 | BM | 44.0 | 141 |

| M6 | HAZ | 152.1 | 531 |

| M5 | WM | 29.4 | 93 |

| M4 | HAZ | 181.4 | 658 |

| M3 | BM | 46.6 | 149 |

| M2 | BM | 7.9 | 25 |

| M1 | BM | −18.6 | −59 |

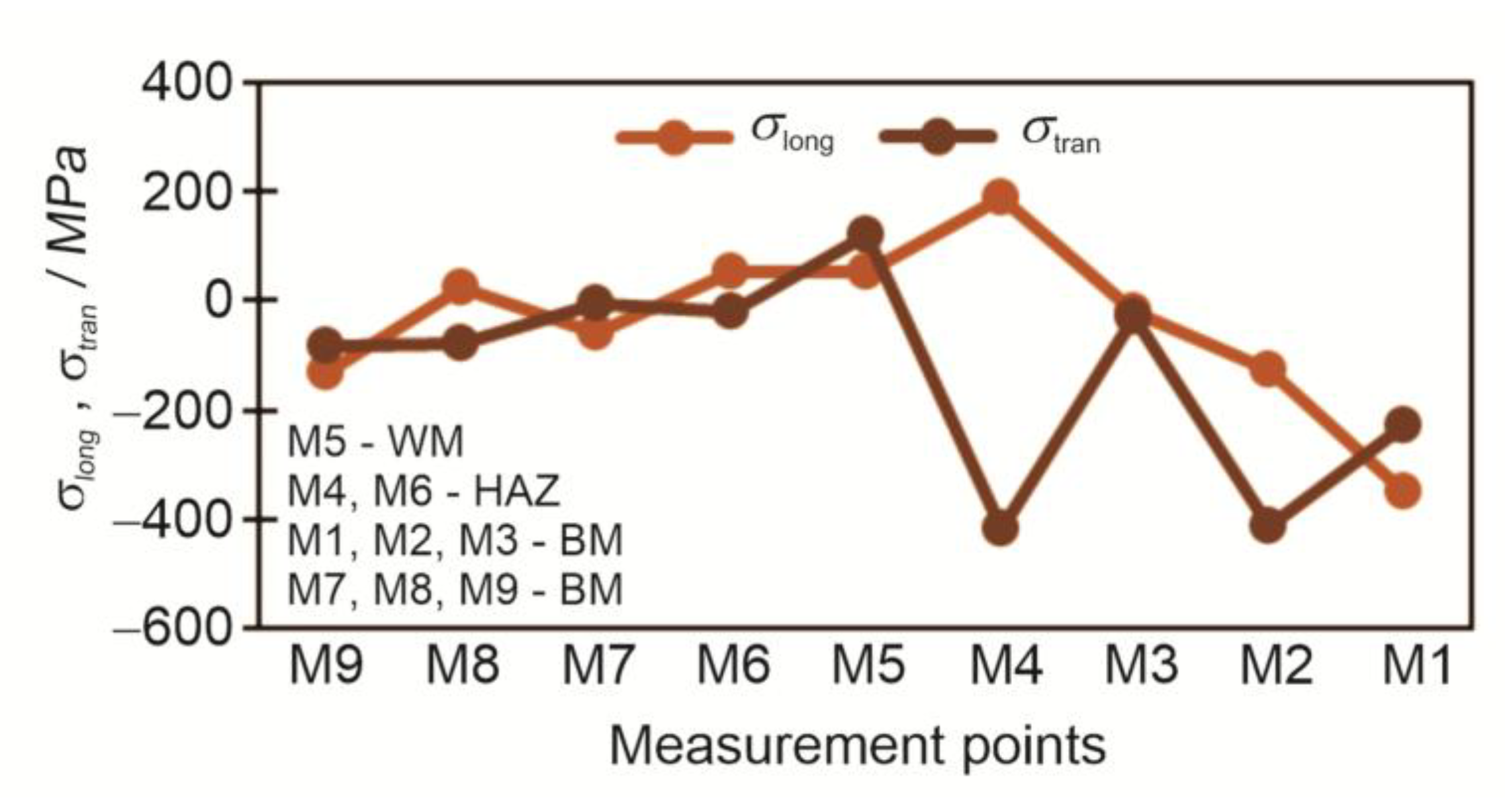

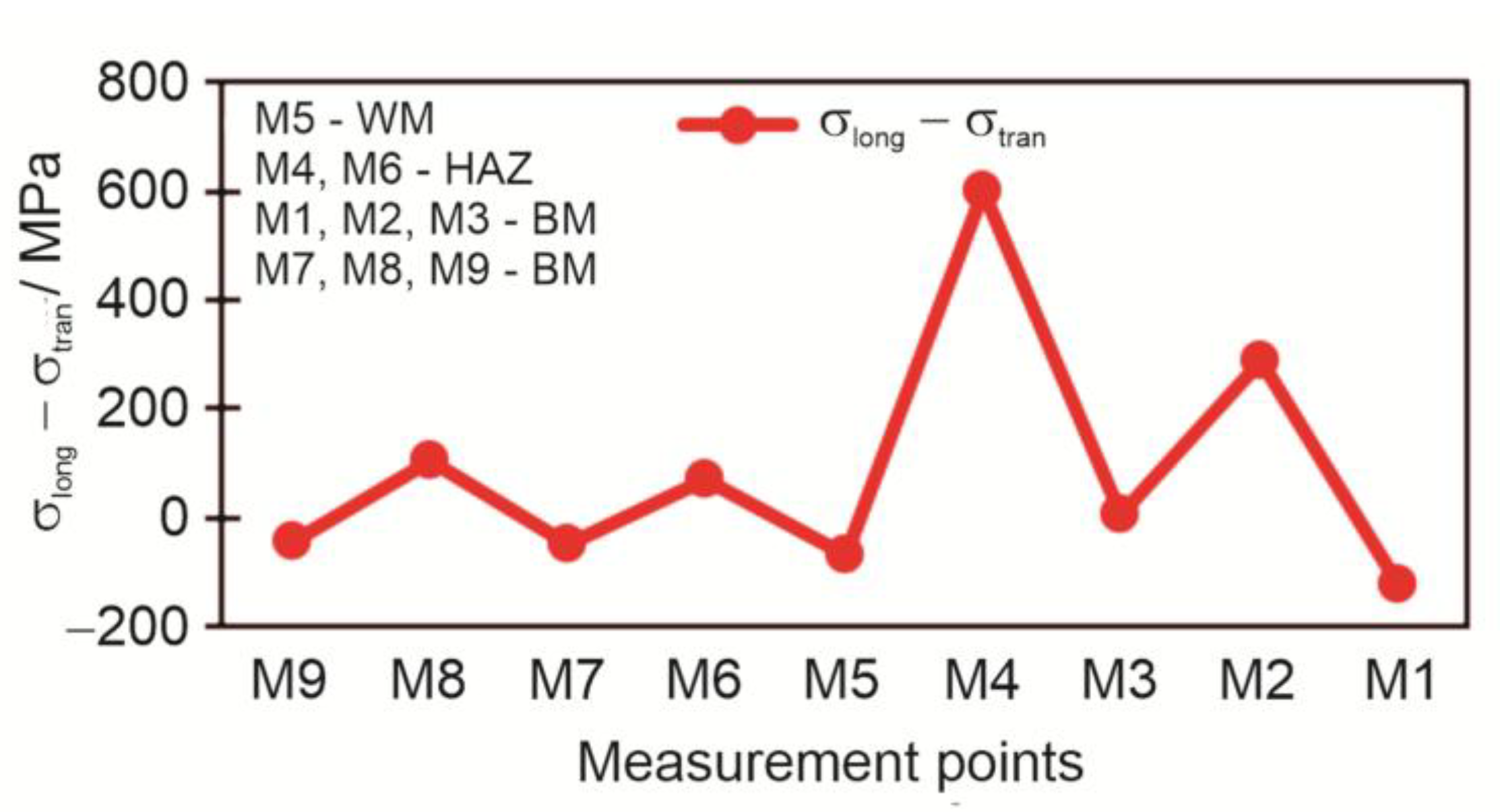

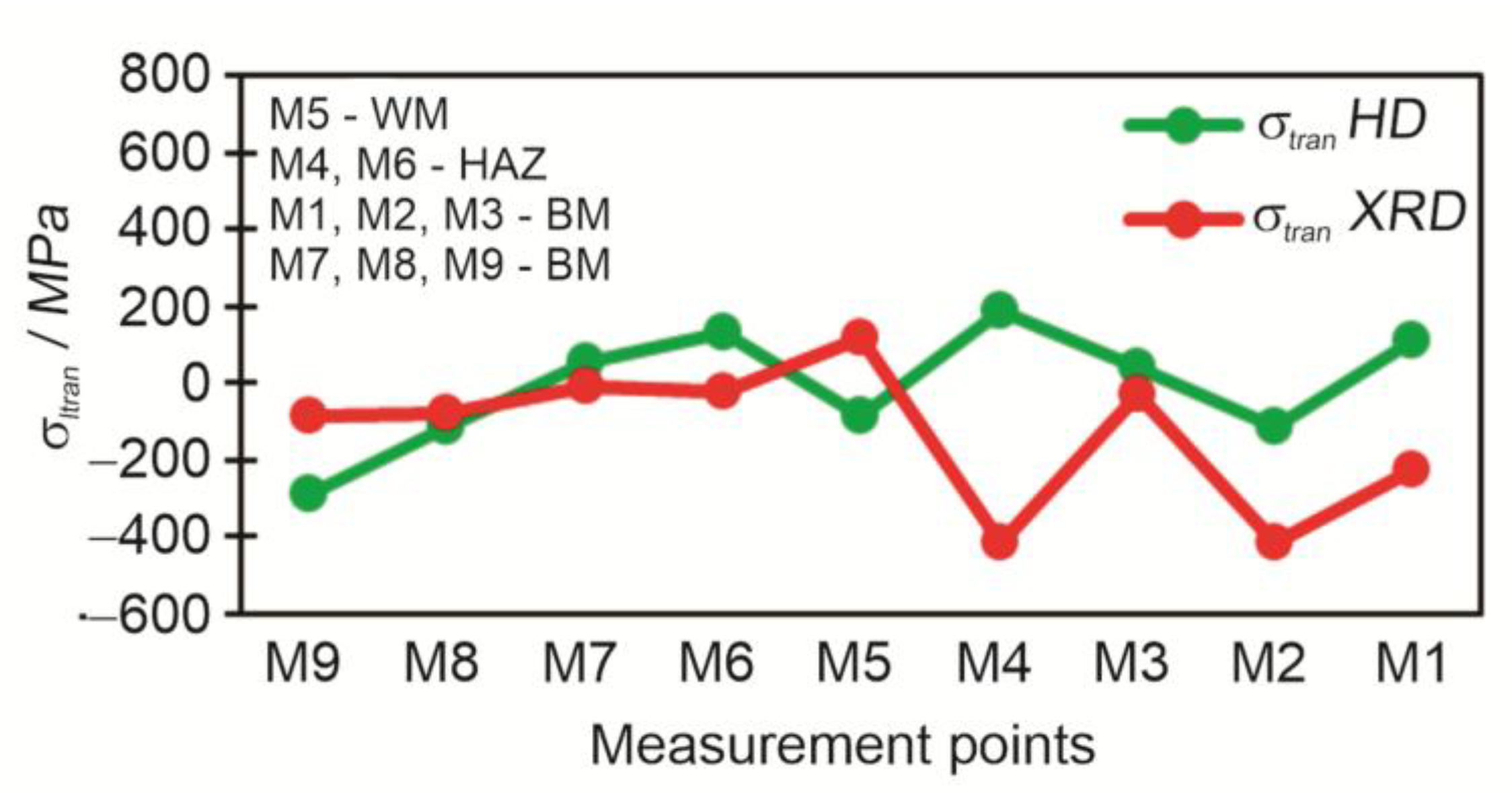

| Measurement point | Residual stresses in longitudinal direction σlong / MPa |

Residual stresses in transverse direction σtran / MPa |

Subtraction of long. and tran. residual stresses σlong – σtran / MPa |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M9 | BM | −130 | −85 | −45 |

| M8 | BM | 25 | −80 | 105 |

| M7 | BM | −57 | −7 | −50 |

| M6 | HAZ | 52 | −19 | 71 |

| M5 | WM | 53 | 119 | −66 |

| M4 | HAZ | 186 | −415 | 601 |

| M3 | BM | −22 | −31 | 9 |

| M2 | BM | −125 | −413 | 288 |

| M1 | BM | −349 | −228 | −121 |

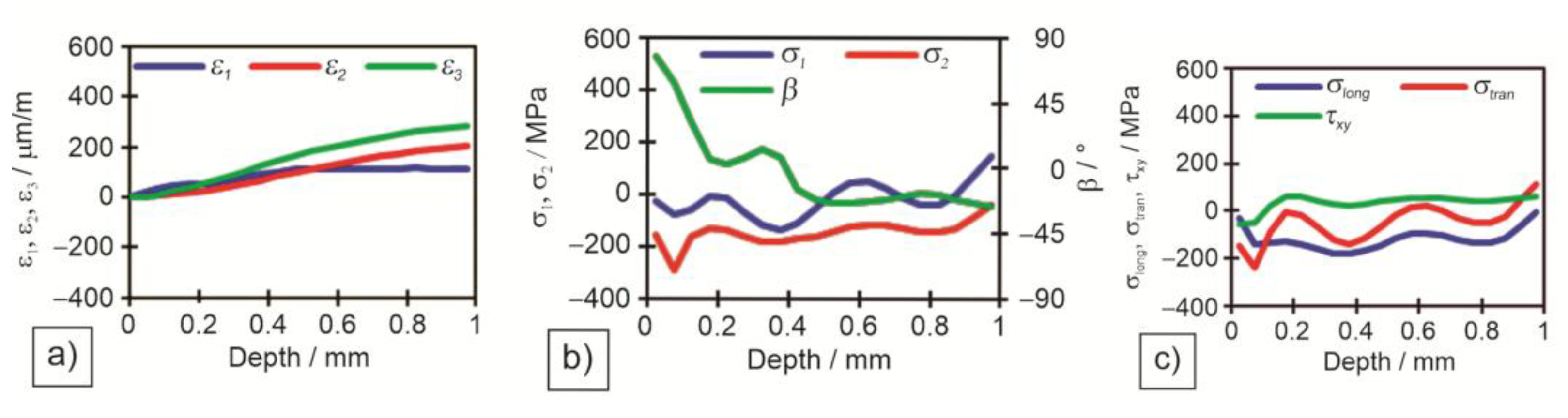

| Measurement point | Principal stress 1 / MPa 1 / MPa |

Principal stress 2 / MPa 2 / MPa |

Angle of principal stresses / ° / ° |

Longitudinal stress long / MPa long / MPa |

Transverse stress tran / MPa tran / MPa |

Shear stress xy / MPa xy / MPa |

Subtraction of long. and tran. stresses long − tran / MPa long − tran / MPa |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | BM | −41 | 147 | −26.2 | −4 | 110 | 57 | −114 |

| M2 | BM | −162 | −42 | 49.8 | −92 | −112 | −10 | 20 |

| M3 | BM | −55 | 98 | −36.3 | −1 | 44 | 22 | −45 |

| M4 | HAZ | 136 | 553 | −69.4 | 501 | 188 | −156 | 313 |

| M5 | WM | −90 | 176 | 85.6 | 175 | −88 | −132 | 263 |

| M6 | HAZ | 93 | 644 | −74.8 | 607 | 131 | −238 | 476 |

| M7 | BM | 41 | 97 | 59.5 | 82 | 55 | −13 | 27 |

| M8 | BM | −162 | −42 | 49.8 | −92 | −112 | −10 | 20 |

| M9 | BM | −339 | −19 | 65.9 | −72 | −285 | −106 | 213 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).