1.1. Evolution of rebar potential, Rs, and Rc

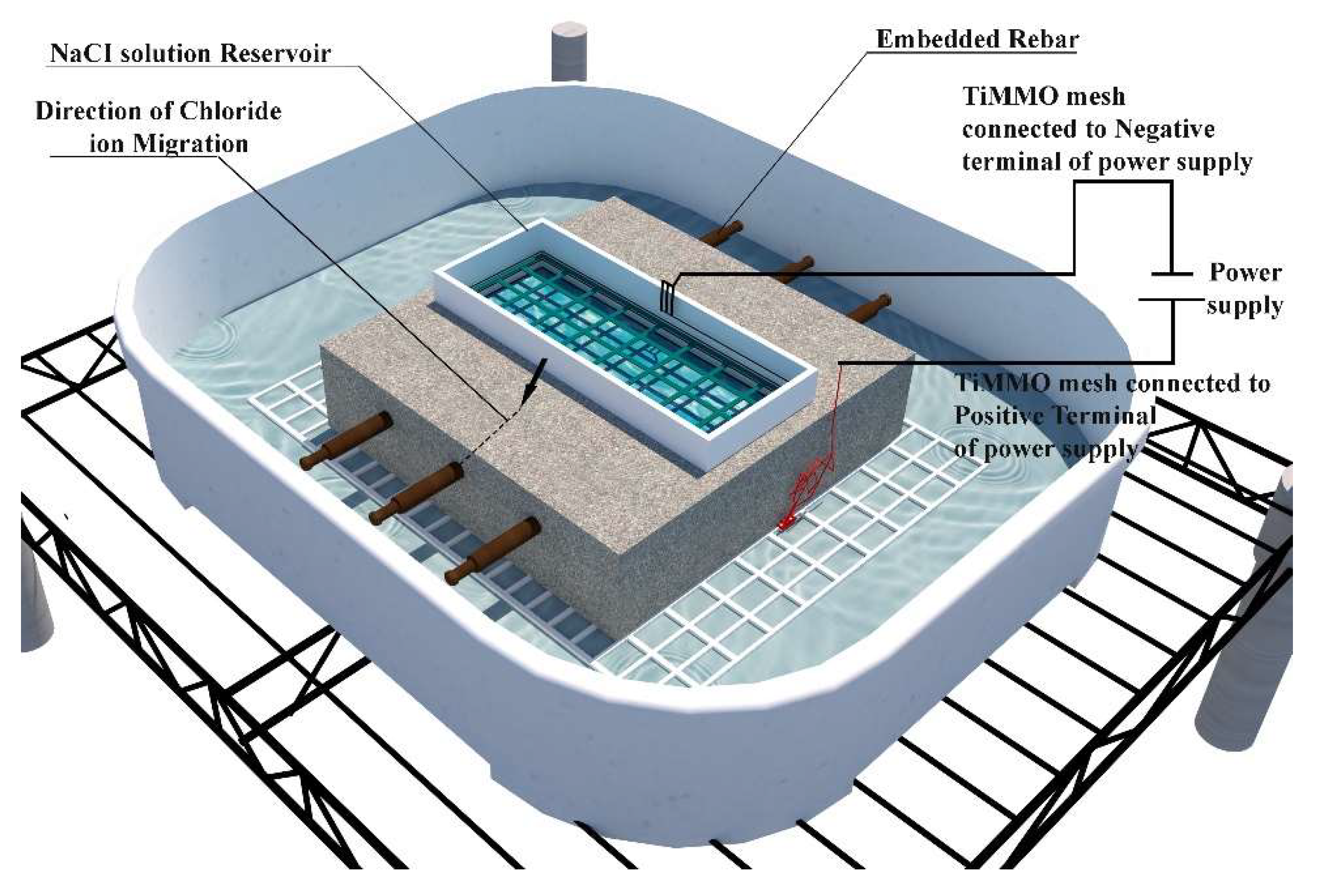

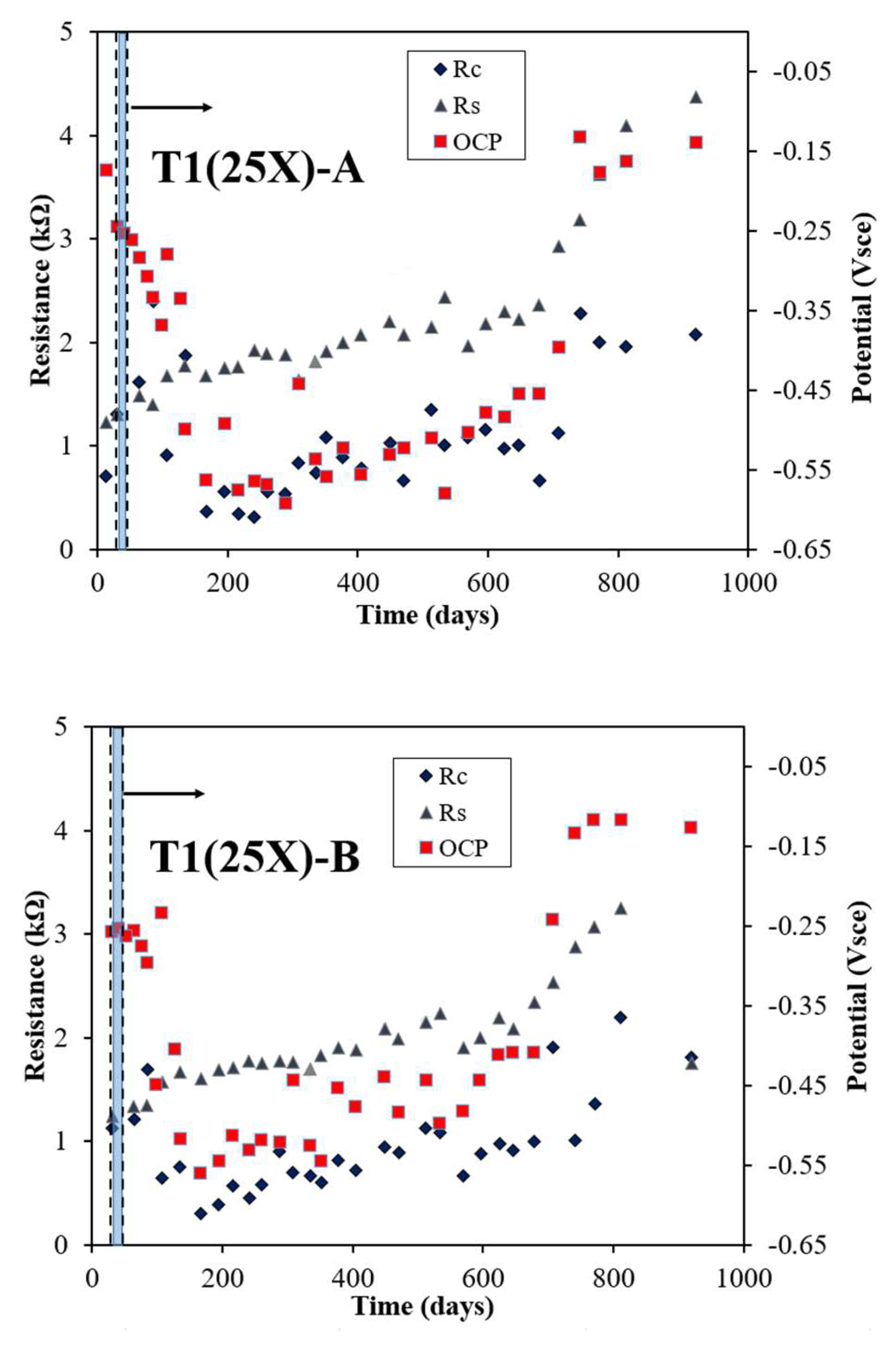

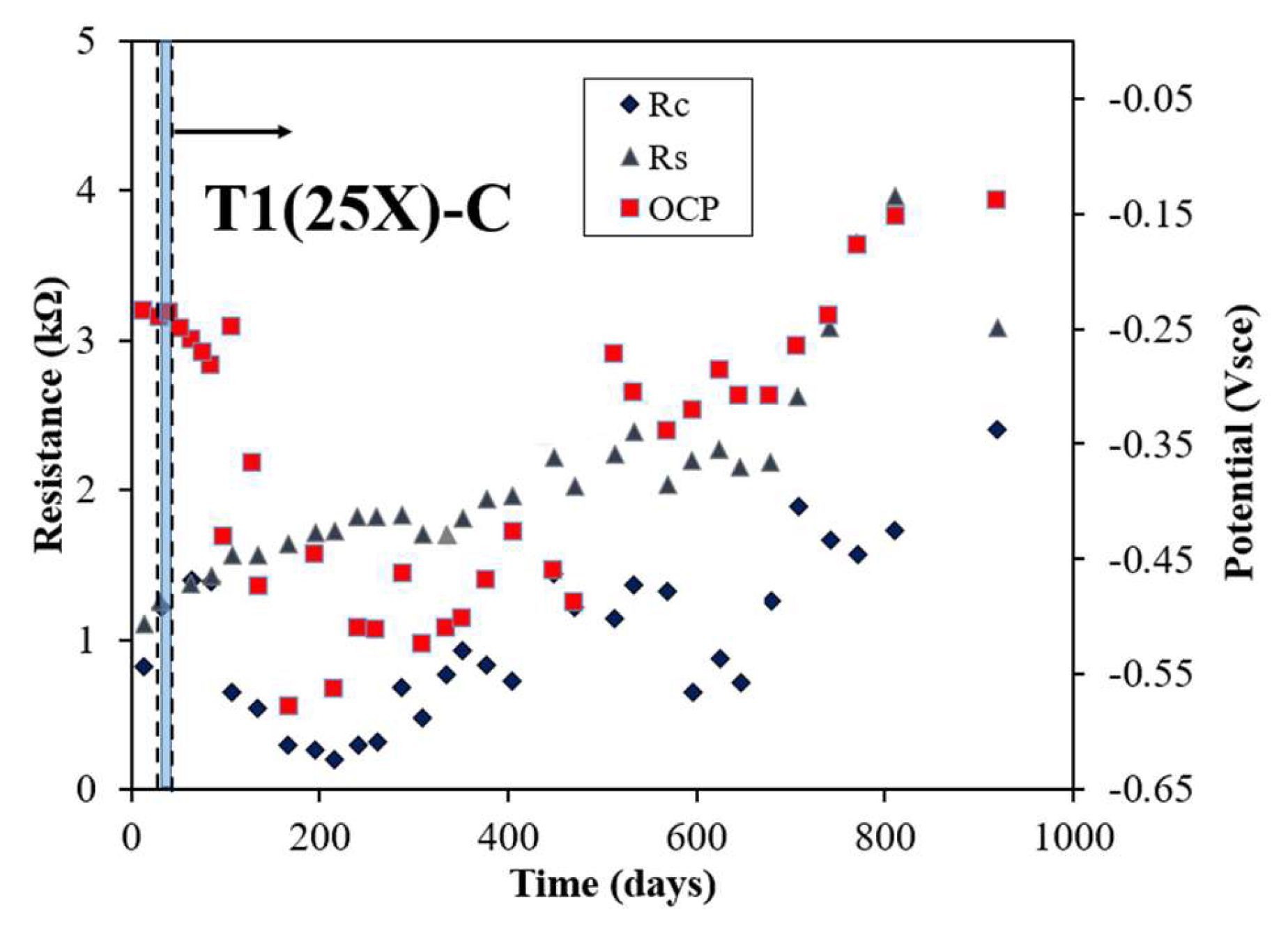

In the figures (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), "Day zero" marks the start of solution introduction into the reservoir, not the specimen's age. Corrosion propagation is shown to the right of the dashed line, with arrows indicating the post-electromigration phase. When two dashed lines appear, the interval between them represents the total electromigration exposure time, while the blue prisms highlight the "system on" period when the electric field was applied.

Figure 2 illustrates the evolution in rebar potential, Rs, and Rc, measured via the LPR/EIS technique, for three rebars (25X-A, 25X-B, and 25X-C) within the T1 sample, which employed a 5 cm reservoir length. All rebars exhibited negative potential values and relatively low Rc values, with significant changes observed within approximately 40 days during the electromigration phase. For 25X-A, the potential dropped sharply after electromigration ended, reaching -0.592 Vsce by day 288, before gradually shifting towards more positive values. During this period, Rs values steadily increased, while Rc values remained below 2 kΩ throughout the monitoring period. For 25X-B, the potential similarly declined after electromigration ceased, reaching -0.545 Vsce by day 195. Following this, the potential fluctuated until day 750, gradually trending more positive. The Rs values showed a consistent rise, while Rc values varied but mostly stayed below 1.5 kΩ. In the case of 25X-C, the potential significantly dropped to -0.579 Vsce by day 167 post-electromigration and gradually became more positive over time. The Rs values continued to rise, while Rc values exhibited fluctuations during the monitoring period. By day 534, the rebar potentials were measured at -0.581 Vsce for 25X-A, -0.499 Vsce for 25X-B, and -0.306 Vsce for 25X-C, highlighting distinct differences among the rebars. These findings align with similar observations reported in previous studies [

19,

23,

24,

25].

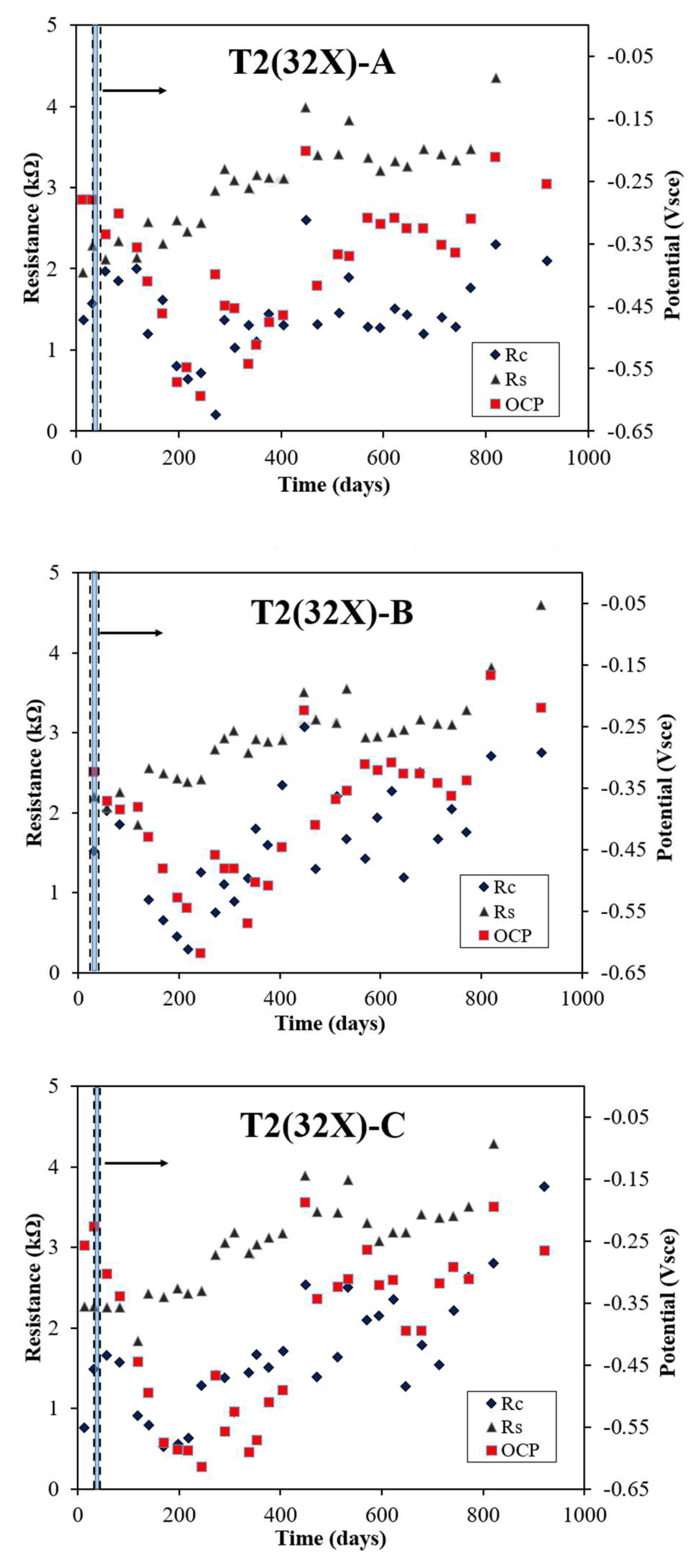

Figure 3 depicts the evolution in rebar potential, Rs, and Rc, measured through the LPR/EIS technique, for three rebars in the T2 sample (32X), identified as 32X-A, 32X-B, and 32X-C, with a 5 cm reservoir length. All rebars showed negative potential values and lower Rc values within approximately 12 days during the electromigration process. For 32X-A, the rebar potential dropped significantly after electromigration ended, reaching -0.594 Vsce by day 244, then fluctuated and gradually moved toward more positive values. The Rs values steadily increased, while Rc values varied throughout the monitoring period. Similarly, the rebar potential of 32X-B sharply decreased to -0.620 Vsce by day 244 after electromigration ceased, eventually trending more positive over time. Both Rs and Rc values fluctuated during the observation period. For 32X-C, the rebar potential also declined significantly to -0.619 Vsce by day 244, fluctuating before gradually becoming more positive. The Rs values showed a consistent upward trend, while Rc values exhibited fluctuations throughout the monitoring period. By day 513, the recorded rebar potentials were -0.367 Vsce for 32X-A, -0.369 Vsce for 32X-B, and -0.323 Vsce for 32X-C, highlighting variations across the rebars. These findings emphasize the distinct behaviors of rebar potential, Rs, and Rc values over time, with additional comparisons provided in references [

19,

26,

27] for other T1 and T2 specimens.

The variation in rebar (corrosion) potential observed in reinforced concrete samples can be attributed to the varying levels of corrosion activity in different areas of the material. Several factors contribute to these changes, including differences in the concrete mix, oxygen availability, moisture levels, and chloride concentrations. These elements create localized areas of corrosion, leading to fluctuations in the overall potential. Additionally, environmental conditions such as temperature and humidity significantly affect the electrochemical reactions occurring at the steel reinforcement, further influencing the corrosion potential. As these conditions change, they alter the rate of corrosion and modify the electrochemical behavior, causing shifts in rebar potential. Therefore, the fluctuations in rebar potential reflect the complex and dynamic nature of the corrosion process, shaped by the interaction of these environmental factors.

1.1. Evolution of Icorr with time

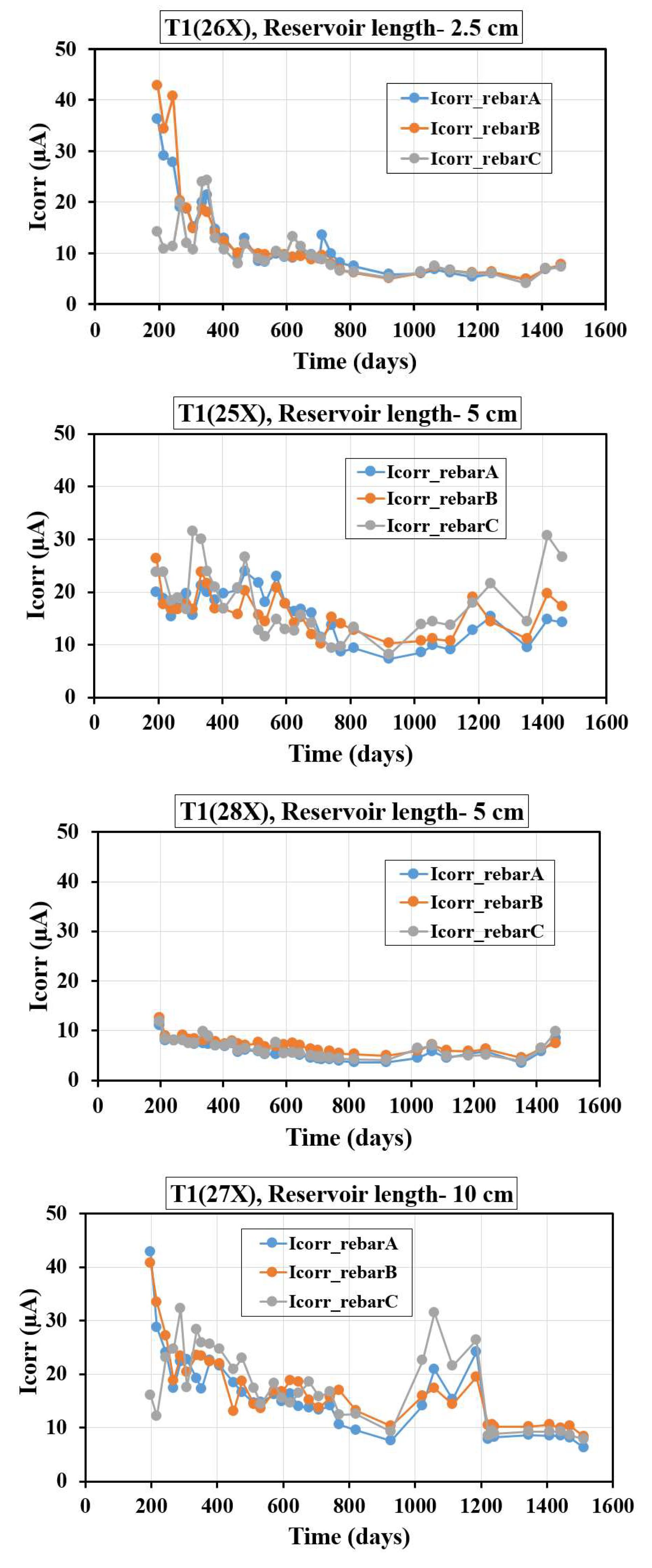

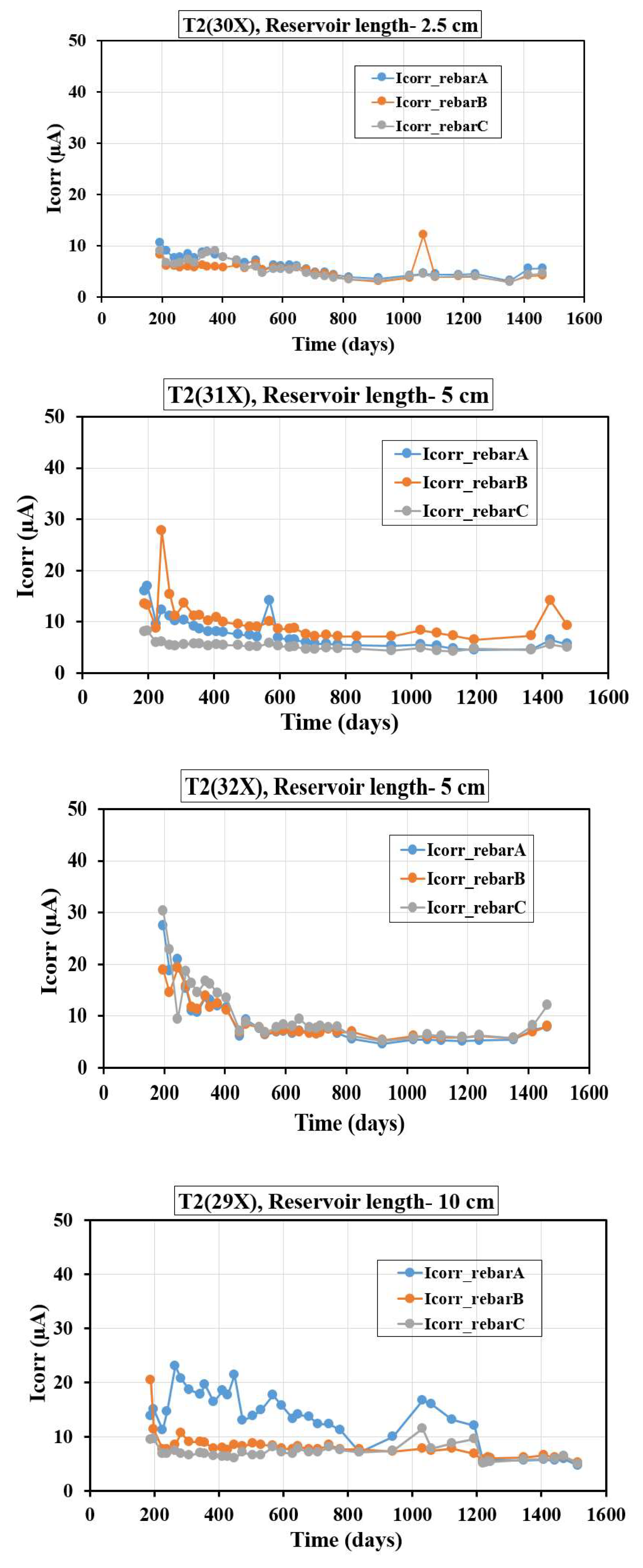

This section presents the temporal evolution of Icorr, measured via the GP technique, for specimens made from different concrete mixes and containing three rebars. It is important to highlight that in most of the plots shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, day zero represents the introduction of the solution into the reservoir, rather than the actual age of the specimens. Since the solution reservoirs were installed at different times, the number of days since the initial filling varies across samples. For the T1 and T2 specimens with three rebars, Icorr readings were taken from day 200 to day 1600, and the corresponding plots in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 were generated based on these readings using the GP method.

Figure 4 illustrates the variation of Icorr over time for T1 specimens with different reservoir lengths and three embedded rebars (A, B, and C). For the specimen with a 2.5 cm reservoir length (T1-26X), Icorr begins at a high level (around 40-50 µA), rapidly declines within the first 200 days, and stabilizes below 10 µA by 600 days. This indicates an initial phase of active corrosion likely due to aggressive chloride ingress, followed by the formation of protective layers and limited ion availability. In the case of a 5 cm reservoir length (T1-25X), Icorr starts at moderate levels (around 20-25 µA) with significant fluctuations during the first 600 days, stabilizing around 10-15 µA between 600 and 1400 days, and showing a late-phase increase (up to ~30 µA for rebar C) after 1400 days. The larger reservoir likely prolonged moisture and ion ingress, causing periodic spikes in corrosion activity and suggesting a localized breakdown of protective layers. Meanwhile, the specimen with a 5 cm reservoir length (T1-28X) demonstrates superior corrosion resistance, with Icorr starting low (around 5-10 µA) and remaining stable with minimal fluctuation, likely due to enhanced densification and reduced chloride diffusion achieved by the fly ash and slag. For the specimen with a 10 cm reservoir length (T1-27X), Icorr initially starts high (around 30–40 µA) during the first 200 days, reflecting active corrosion due to incomplete hydration. Between 200 and 1000 days, Icorr decreases significantly (around 10–20 µA) as the fly ash and slag improve the concrete's durability by reducing permeability and ion ingress. After 1000 days, a slight increase (around 10–30 µA) indicates possible re-initiation of corrosion due to chloride accumulation. When comparing all cases, smaller reservoirs (2.5 cm) exhibit rapid corrosion initiation due to aggressive ion ingress in the early stages. However, the limited size of the reservoir restricts the continuous supply of chlorides and moisture, resulting in lower long-term corrosion rates as the system stabilizes. In contrast, larger reservoirs (10 cm) provide a sustained pathway for chloride and moisture ingress, leading to prolonged corrosion activity over time, as reflected by higher long-term corrosion rates and periodic spikes in the Icorr values. Among the specimens, T1-28X specimen demonstrates significantly better performance compared to T1-25X specimen. The consistently lower Icorr values observed in T1-28X highlights the superior corrosion resistance achieved through the optimized material composition, specifically the use of fly ash and slag, which improve the concrete's microstructure by reducing porosity and permeability. Additionally, effective curing conditions contribute to enhanced densification and the formation of robust passive layers on the steel rebars.

Figure 5 presents the evolution of Icorr over time for T2 specimens with varying reservoir lengths and three embedded rebars (A, B, and C). For T2(30X) specimens with a 2.5 cm reservoir length, Icorr begins low (around 10 µA) during the early phase (0–200 days), stabilizing below 10 µA after 200 days with minimal fluctuations, except for a spike (around 15 µA) around 1000–1200 days in rebar B, likely due to localized chloride ingress or passivation disruption. The smaller reservoir restricts ion ingress, maintaining low corrosion rates. For T2(31X) specimens with a 5 cm reservoir length, Icorr peaks higher (around 20–30 µA) during the first 250 days, indicating greater ion availability. It decreases to around 5–10 µA by 600 days, stabilizing with occasional late-phase spikes (around 15 µA for rebar B at 1430 days), reflecting prolonged ion ingress. For T2(32X) specimens with a 5 cm reservoir length, the Icorr initially peaks at 30–33 µA during the first 200 days due to higher moisture and chloride availability. It then decreases to around 10 µA by 200–600 days as the hydration of fly ash and silica fume reduces permeability and ion ingress. Beyond 600 days, Icorr stabilizes at 5–10 µA, indicating a passive state with minimal corrosion activity, apart from occasional late-phase spikes due to localized disruptions. For T2(29X) specimens with a 10 cm reservoir length, during the initial phase (0–200 days), all rebars show low Icorr values (<15 µA), followed by a significant rise for rebar A (peaking at 20–25 µA) between 200–600 days, indicating increased environmental susceptibility. The rebars B and C exhibit smaller peaks and the Icorr values were mostly less than 10 µA. After 600 days, fluctuations in rebar A’s Icorr suggest wet-dry cycles, while rebars B and C stabilize with moderate corrosion activity. Beyond 1200 days, all rebars stabilize below 10 µA, possibly due to protective layer formation or reduced availability of corrosive agents. The reservoir length affects Icorr values by controlling ion availability. The smaller reservoirs (2.5 cm, T2-30X) restrict ion ingress, maintaining low Icorr values with minimal fluctuations. The medium reservoirs (5 cm, T2-31X and T2-32X) show higher initial Icorr peaks due to greater ion availability but stabilize at around 5–10 µA after 600 days as concrete densifies. The larger reservoirs (10 cm, T2-29X) exhibit delayed yet significant Icorr increases, particularly for rebar A, due to prolonged exposure. As the time passed, all specimens stabilize, demonstrating the protective effects of fly ash and silica fume. Therefore, smaller reservoirs limit long-term corrosion by restricting ion ingress, while larger reservoirs sustain higher initial and long-term corrosion activity. The supplementary cementitious materials like fly ash and silica fume improve durability by reducing permeability and enhancing passivation, but larger reservoirs emphasize the need for additional protective measures to manage long-term corrosion risks. A comparable findings regarding Icorr values for T1 and T2 samples were documented in several studies [

19,

28,

29,

30]. These studies consistently highlighted similar trends in corrosion activity, where the Icorr values aligned closely with those observed in the current investigation. The reported data not only corroborate the present results but also reinforce the influence of various experimental conditions and mix compositions on the corrosion performance of the samples. This consistency across studies suggests a robust relationship between the experimental parameters and the measured Icorr values for both T1 and T2 specimens.

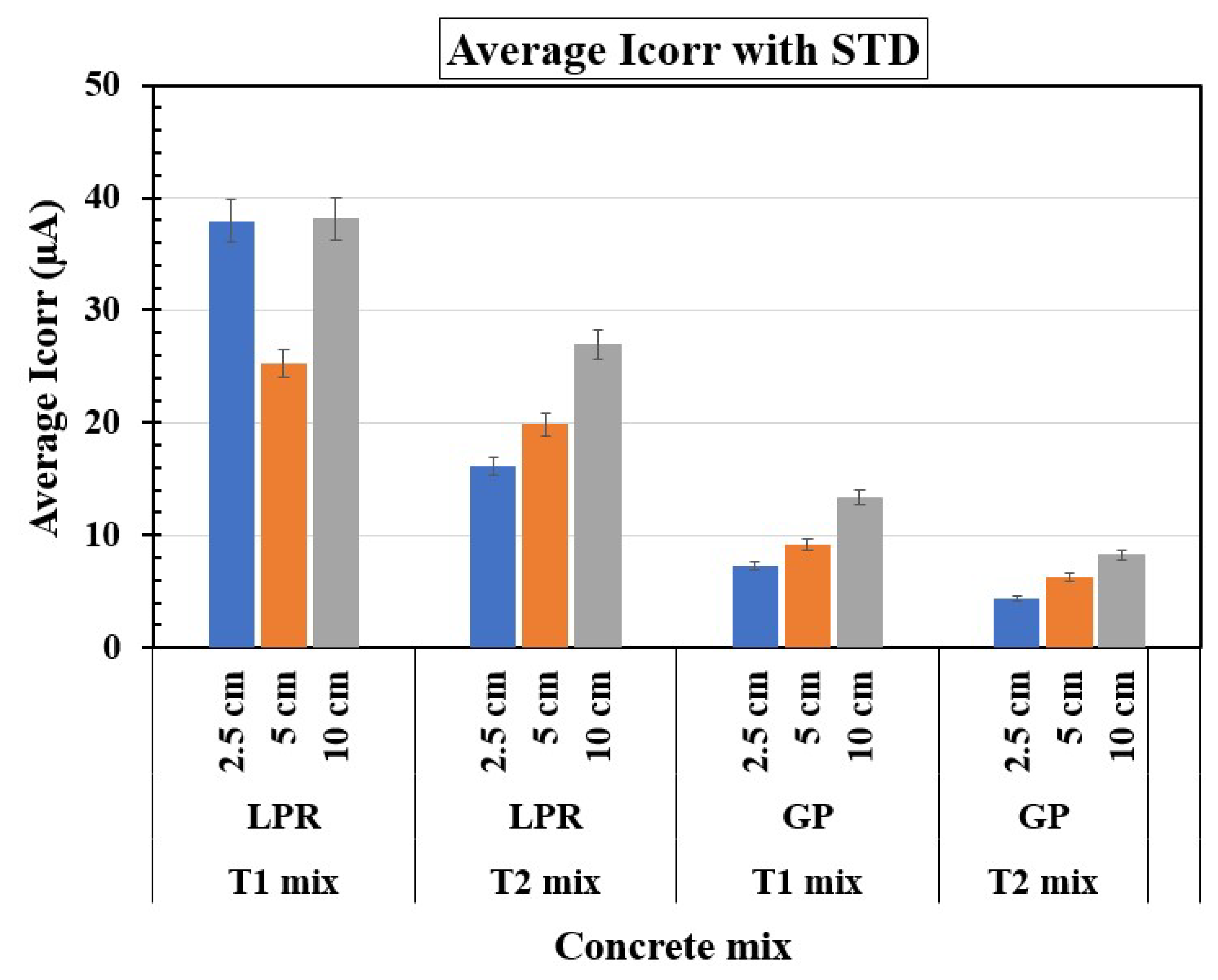

Table 3 presents the average Icorr values and their corresponding standard deviation (STD) values, derived from the last 15 sets of readings obtained through the LPR method for T1 and T2 concrete mixes. It also showcases the average Icorr and STD values across three rebar specimens (A, B, and C) at varying reservoir lengths of 2.5 cm, 5 cm, and 10 cm. This data underscores the significant influence of material composition and exposure conditions on the corrosion behavior of reinforced concrete mixes. The T1 specimens consistently exhibits higher Icorr values and greater STDs across all reservoir lengths, indicating more severe corrosion activity and greater variability in corrosion behavior compared to T2 specimens. This disparity is attributed to the distinct effects of the SCMs on the concrete microstructure. In T2 specimens, the inclusion of silica fume significantly refines the microstructure by reducing pore sizes and enhancing density, resulting in improved resistance to chloride ingress and reduced corrosion rates. In contrast, T1 specimen, containing fly ash and slag, experiences slower microstructural densification due to the delayed reactivity of slag, which prolongs the period of vulnerability to corrosion. The reservoir length further influences Icorr and STD values, highlighting the role of environmental factors in corrosion dynamics. At shorter reservoir lengths, restricted ionic mobility leads to intensified localized corrosion, as evidenced by higher Icorr values and greater variability. The longer reservoir lengths, however, provide a more extensive diffusion path, promoting uniform ion distribution and consequently reducing both corrosion intensity and variability. Despite this trend, T2 specimen demonstrates superior performance at all reservoir lengths, maintaining lower Icorr values and smaller STDs, underscoring the ability of silica fume to mitigate corrosion effectively, even under conditions of restricted ion mobility. These findings reinforce the importance of selecting appropriate SCMs, such as silica fume, to enhance the durability of reinforced concrete structures. Additionally, they underscore the significance of optimizing reservoir design to minimize corrosion rates and variability, ultimately contributing to the construction of long-lasting and reliable infrastructure.

Table 4 highlights the average Icorr values along with the STD values, which were calculated from the last 15 sets of readings obtained using the GP method for T1 and T2 concrete mixes.

Table 3 also presents average Icorr and STD values across three rebar specimens (A, B, and C) at varying reservoir lengths (2.5 cm, 5 cm, and 10 cm), demonstrating how the combination of material composition and exposure conditions influences corrosion behavior. The influence of reservoir length is evident in both T1 and T2 samples. As the reservoir length increases from 2.5 cm to 10 cm, there is a consistent rise in Icorr values for both sets of samples, indicating higher corrosion activity due to increased chloride and moisture ingress. However, T2 samples consistently exhibit lower Icorr values compared to T1 samples, especially at 5 cm and 10 cm, suggesting that the incorporation of silica fume in T2 sample enhances corrosion resistance by reducing permeability and improving the microstructure of the concrete. The STD values also highlight the stability of corrosion behavior in T2 samples, with lower variability compared to T1 samples at all reservoir lengths. The role of SCMs is critical in controlling corrosion rates. The T1 samples, which incorporates fly ash and slag, exhibits higher Icorr and STD values compared to T2 samples, which combines fly ash and silica fume. The combination of fly ash and slag improves durability and reduces permeability but does not offer the same level of protection as silica fume, which significantly enhances the concrete matrix’s density and reduces permeability. Silica fume's contribution results in more stable corrosion behavior across different exposure conditions. Therefore, the findings underline the importance of selecting appropriate SCMs, such as silica fume, and optimizing environmental exposure, such as reservoir length, to mitigate corrosion in reinforced concrete structures effectively. Moreover, comparisons of selected rebars between T1 and T2 groups suggest that reservoir length plays a crucial role in determining corrosion behavior, with longer reservoir lengths correlating with higher average Icorr values and greater variability. The average Icorr values for FA samples (containing 20% fly ash as a cement replacement) varied between 39.9 and 91.0 µA, as reported by Balasubramanian [

31]. These samples were installed vertically and subjected to electromigration techniques to expedite chloride ion transport [

31]. In contrast, the present study positioned the samples horizontally, with chloride ponds created directly above the embedded rebar within the specimens. Kayali and Zhu documented Icorr values ranging from 9.7 to 25.3 µA for T2 specimens [

32]. Additionally, for concrete mixes incorporating fly ash as a partial cement replacement, Otieno et al. reported an average Icorr value of 49.9 µA [

3], while O'Reilly et al. observed an average Icorr value of 38.5 µA [

33].

Figure 6 illustrates the variation in average Icorr with reservoir length for T1 and T2 concrete mixes, comparing LPR and GP measurement methods. Across both methods, the shorter reservoir lengths (2.5 cm) yield the highest Icorr values for both mixes, indicating more intense corrosion activity, with T1 specimens consistently showing higher values than T2 specimens. In LPR measurements, T1 specimen exhibits significantly higher Icorr (around 40 μA) at 2.5 cm compared to T2 specimen, which demonstrates a comparatively lower Icorr values, reflecting better resistance to corrosion. At medium (5 cm) and longer reservoir lengths (10 cm), Icorr values increase for both mixes, though T1 specimen still shows consistently higher corrosion activity than T2 specimens. The GP measurements exhibit a similar trend but generally record lower Icorr values than LPR measurements, particularly for T2 specimens, emphasizing T2 specimen superior performance in mitigating corrosion. The results highlight that T2 specimens (containing silica fume) provides enhanced durability and reduced corrosion rates across all reservoir lengths, and GP measurements appear to be more conservative than LPR measurements in quantifying corrosion.

The variations in Icorr values observed in T1 and T2 specimens highlight the combined impact of reservoir length, material composition, curing conditions, and environmental exposure on corrosion behavior. The shorter reservoir lengths (2.5 cm) restricted chloride and moisture ingress, resulting in lower Icorr values and reduced corrosion activity. Conversely, longer reservoirs (10 cm) enabled sustained ionic ingress, leading to higher Icorr values over time due to enhanced exposure to corrosive agents. The incorporation of SCMs played a crucial role in enhancing durability, with silica fume in T2 specimens outperforming fly ash and slag in T1 specimens. Silica fume refined the microstructure by reducing pore size and permeability, resulting in lower Icorr values and improved corrosion resistance. In contrast, the delayed reactivity of slag in T1 specimens prolonged the vulnerability to chloride penetration, leading to higher Icorr values and greater variability. The curing conditions further influenced the corrosion performance by promoting the development of a denser, more protective concrete matrix, reducing the susceptibility of the reinforcement to corrosion. The environmental conditions, particularly wet-dry cycles in specimens with larger reservoirs, caused periodic spikes in Icorr values due to fluctuating moisture levels. Over time, however, these values tended to stabilize as protective layers formed on the reinforcement surface, though localized disruptions occasionally occurred due to environmental or structural factors.

A comparative analysis of Icorr and STD values from LPR and GP measurements reinforced these findings. The LPR measurements demonstrated higher sensitivity to localized corrosion, with T1 specimens exhibiting consistently higher Icorr values and greater STDs across all reservoir lengths compared to T2 specimens. This confirmed the superior performance of silica fume in mitigating corrosion and stabilizing the corrosion behavior under various exposure conditions. The GP measurements, although less sensitive to localized corrosion, followed similar trends, with T2 specimens consistently showing lower Icorr values and STDs. Therefore, these observations underline the importance of selecting SCMs like silica fume, optimizing reservoir design, and managing environmental exposures to effectively control corrosion rates. While LPR offers detailed insights into localized corrosion dynamics, GP provides a rapid, simplified assessment suitable for routine monitoring. These complementary methods emphasize the need for a holistic approach to designing durable reinforced concrete structures capable of withstanding corrosive environments, ultimately extending their service life and ensuring long-term performance.

1.1. Icorr vs. Rs

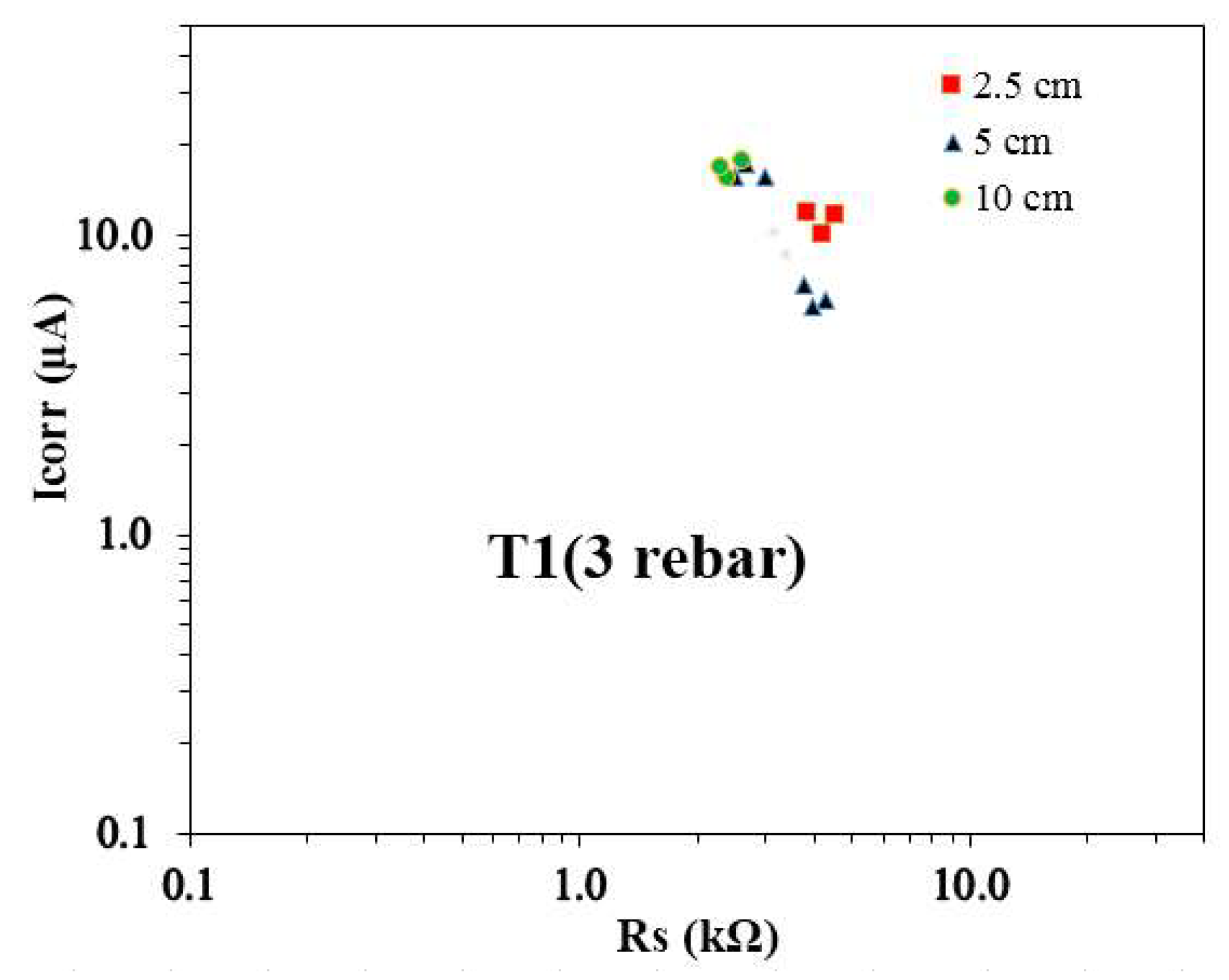

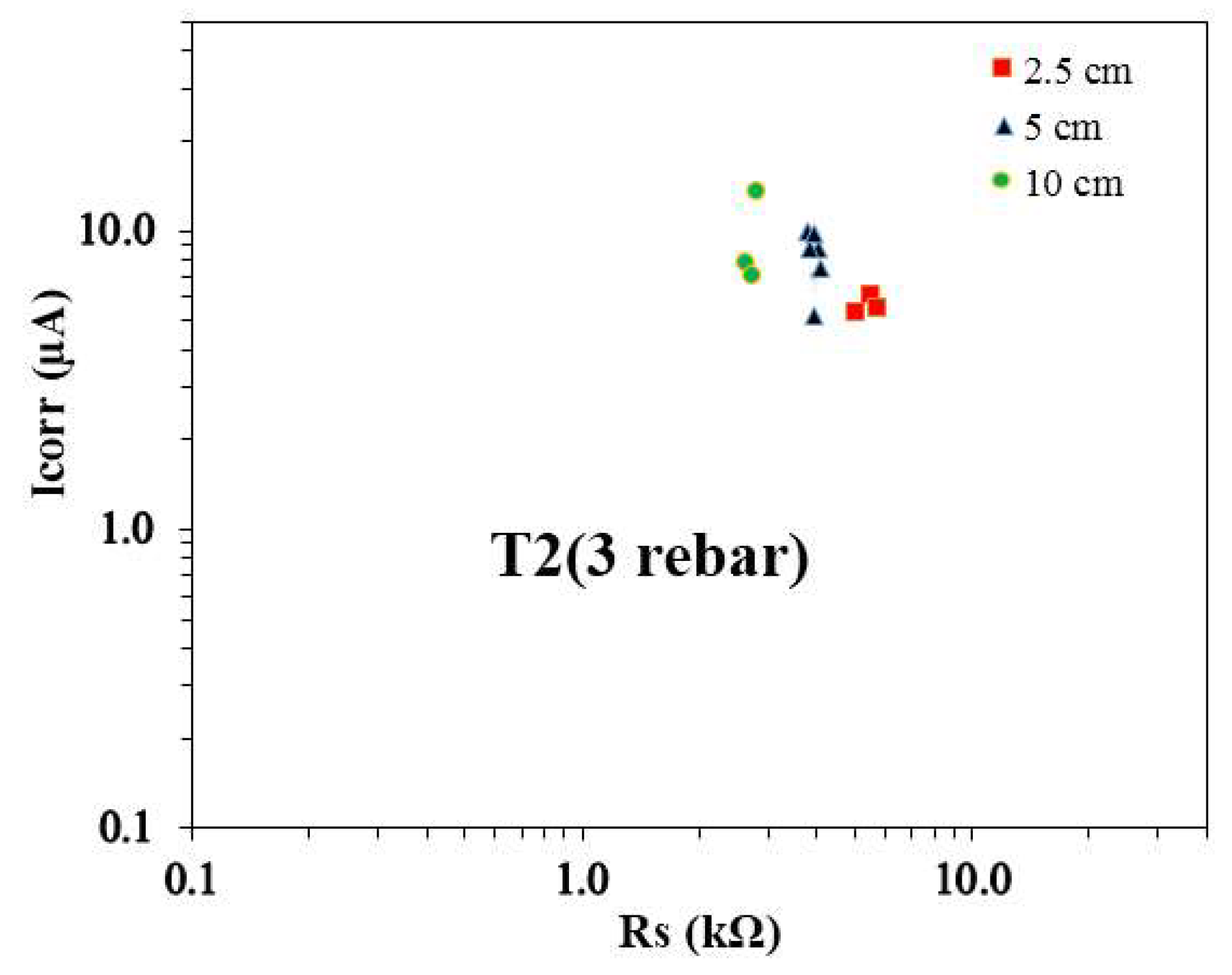

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present the average Icorr vs. average Rs plots derived from GP readings for T1 and T2 concrete mixes, each reinforced with three rebars. The plotted averages represent data collected per rebar over the monitoring period spanning from day 200 to day 1600.

Figure 7 illustrates the relationship between the average Icorr and the average Rs for T1 specimens with three embedded rebars, categorized by reservoir size. The data reveals that rebars in samples with a 5 cm reservoir size exhibited higher Rs values compared to those in other reservoir sizes. In contrast, rebars in the 10 cm reservoir size consistently showed lower Rs values. It is interesting to note that despite the larger Rs values associated with the 5 cm reservoir, the Icorr values for rebars under 5 cm and 10 cm reservoirs were often comparable. This suggests that the active corroding areas for these reservoir sizes may be of similar scale. Notably, the Icorr values for rebars under the 10 cm reservoir size tended to be higher, indicating a greater corrosion activity in these samples. Additionally, the Icorr vs. Rs pairs for rebars in 2.5 cm and 10 cm reservoirs were closely aligned, while the data for the 5 cm reservoir showed a more scattered distribution in both Icorr and Rs values. This spread highlights variability in the corrosion behavior of rebars under the 5 cm reservoir size, potentially influenced by localized factors such as moisture or chloride ingress. Similar findings have been reported in previous studies [19, 28], highlighting consistent trends and supporting the observations made in this research.

Figure 8 presents the relationship between the average Icorr and the average Rs for T2 specimens reinforced with three rebars, differentiated by reservoir size. The data indicates that rebars in the 2.5 cm reservoir size exhibited the highest Rs values compared to those in other reservoir sizes, while the 10 cm reservoir samples consistently showed the lowest Rs values. It is noted that the Icorr values for rebars under the 2.5 cm reservoir size were found to be similar to those observed in the 5 cm reservoir samples, and the Icorr values for the 5 cm reservoir samples closely aligned with those in the 10 cm reservoir samples. This suggests that the size of the actively corroding area under different reservoir conditions may be comparable, as the Icorr shows similar trends across these reservoir sizes. Another noteworthy observation is the distribution of the Icorr vs. Rs data points. For the 2.5 cm reservoir size, the values are tightly clustered, indicating more uniform corrosion behavior. In contrast, the data for the 5 cm and 10 cm reservoir samples exhibit greater variability, with a wider spread in both Icorr and Rs values. This variability could reflect differences in localized environmental factors, such as moisture ingress or chloride penetration, influencing the corrosion process. Previous studies [19, 28] have reported similar findings, demonstrating consistent trends and further reinforcing the observations made in this research.

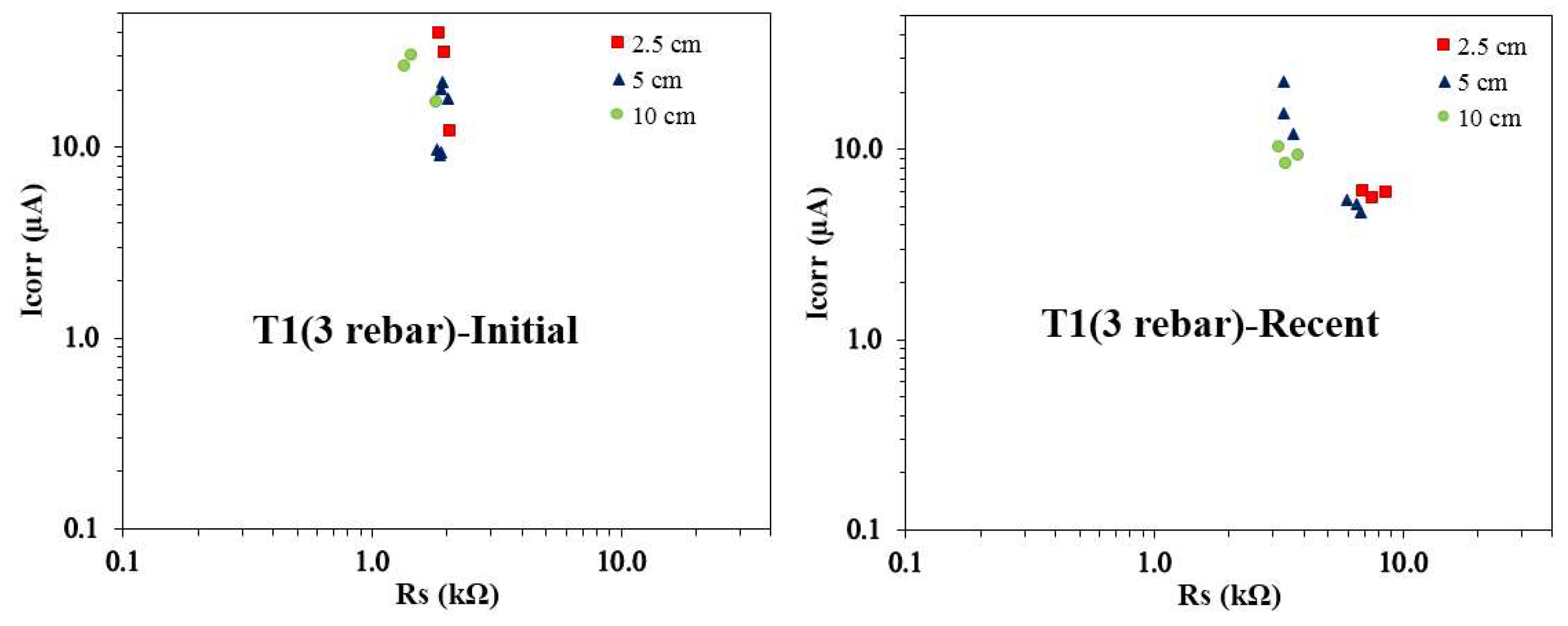

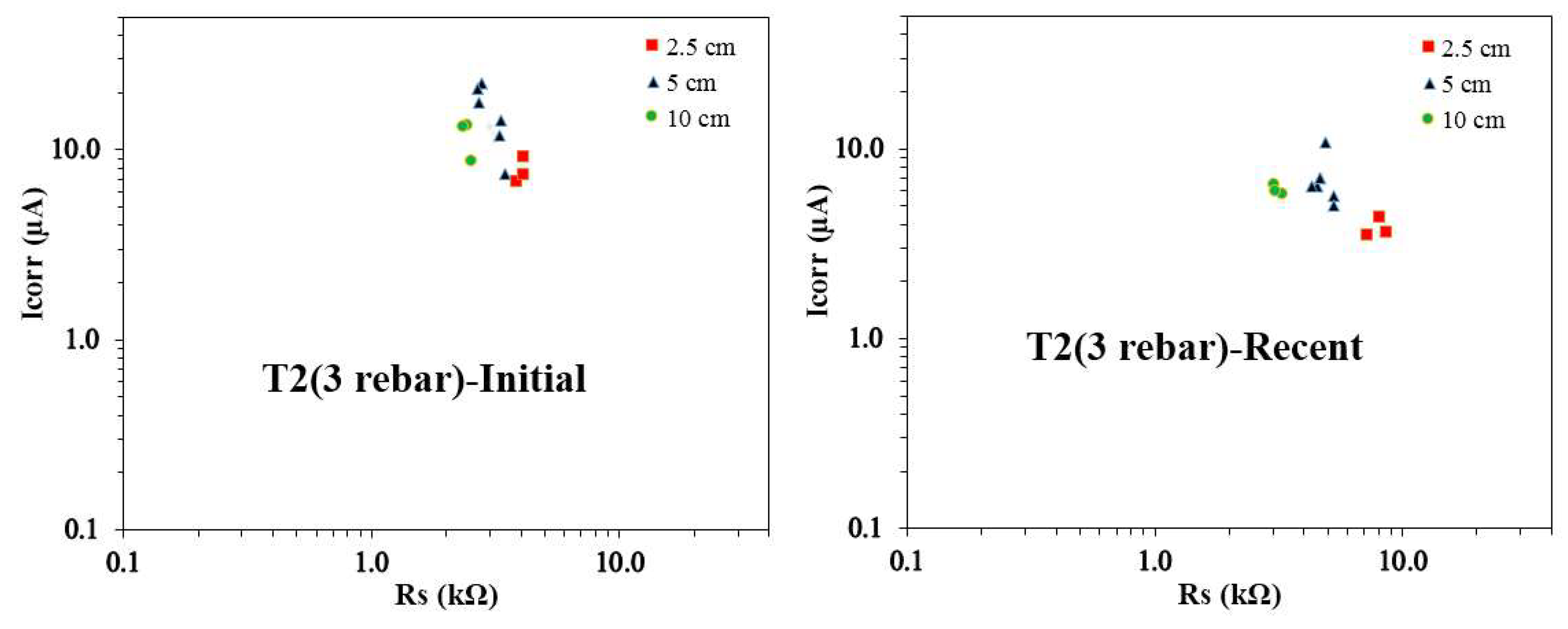

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 present the Icorr vs. Rs plots obtained from GP measurements for T1 and T2 concrete mixes, each incorporating three rebars. The plots on the left illustrate the initial Icorr vs. Rs values, based on the first three measurement sets taken shortly after GP monitoring commenced. In contrast, the plots on the right display the most recent Icorr vs. Rs values, derived from the last two measurement sets. This comparison highlights the progression of rebar corrosion behavior over time, revealing how the relationship between Icorr and Rs changes as the concrete specimens mature and are exposed to varying environmental conditions.

Figure 9 displays the Icorr vs. Rs relationship for T1 concrete specimens with three rebars, highlighting differences between initial and recent measurements across various reservoir sizes. A noticeable trend is that recent Rs values are consistently higher than the initial ones across all reservoir sizes. Among these, the 10 cm reservoir samples exhibit the smallest Rs values for both initial and recent measurements. It is interesting to note that the initial Icorr values for rebars under the 5 cm and 10 cm reservoirs are often similar, while the recent Icorr values align more closely for rebars under the 2.5 cm and 5 cm reservoirs. This similarity in Icorr suggests that the size of the actively corroding area might not vary significantly between these reservoir conditions. Another notable observation is that initial Icorr values are highest for the 2.5 cm reservoir samples, while the recent Icorr values peak for the 5 cm reservoir samples, reflecting a shift in corrosion dynamics over time. The recent Icorr vs. Rs data for the 2.5 cm reservoir samples show a tight clustering, indicating more consistent corrosion behavior. In contrast, the 5 cm and 10 cm reservoir samples display a wider spread in Icorr values, while their Rs values remain relatively uniform. This variability points to differences in the progression and extent of corrosion activity influenced by the reservoir size.

Figure 10 presents the Icorr vs. Rs plots for T2 concrete samples with three rebars, revealing notable trends in the corrosion behavior across various reservoir sizes. It is observed that the recent Rs values are consistently higher than the initial Rs values for all reservoir sizes. However, the 10 cm reservoir samples exhibit the smallest Rs values, both initially and recently. The initial Icorr values for rebars in the 2.5 cm and 5 cm reservoir sizes, as well as the 5 cm and 10 cm reservoir sizes, are often quite similar. Conversely, the recent Icorr values for rebars under 2.5 cm, 5 cm, and 10 cm reservoirs show comparable trends across different pairs, suggesting that the extent of the corroding area may be roughly similar across these reservoir sizes. The initial Icorr values are observed to be higher for the 5 cm reservoir samples, with the most recent Icorr values also reaching their peak for the same reservoir size. This suggests a progression in corrosion activity over time, with sustained or evolving conditions favoring higher corrosion rates in these samples. A key observation is that the recent Icorr vs. Rs pairs for the 2.5 cm and 10 cm reservoir samples are closely clustered, reflecting more uniform corrosion behavior. In contrast, for the 5 cm reservoir samples, while the Icorr values are more spread out, the Rs values remain relatively consistent, signaling a less variable resistance to corrosion despite changes in corrosion current.

The Icorr vs. Rs plots for T1 and T2 concrete mixes reveal evolving corrosion behavior influenced by reservoir size and time. The Rs values consistently increase over time for all reservoir sizes, reflecting enhanced resistivity as concrete matures. The 10 cm reservoir samples consistently exhibit the lowest Rs values, indicating higher ionic mobility. The initial Icorr values peak for the 2.5 cm reservoir in T1 samples and the 5 cm reservoir in T2 samples, while recent Icorr values reach their maximum for the 5 cm reservoir in both mixes, indicating a shift in corrosion activity. The tight clustering of Icorr vs. Rs pairs in the 2.5 cm and 10 cm reservoirs suggests uniform corrosion behavior, whereas variability in the 5 cm samples reflects heterogeneous corrosion progression. These variations highlight the dynamic interplay between material properties, environmental conditions, and reservoir size in influencing corrosion trends.

1.1. Theoretical (Faradaic) calculation of mass loss

In this study, a theoretical mass loss approach was employed, as no visible cracks were observed in any of the samples. The LPR and GP method was periodically conducted to measure Rc values, which were then used to estimate the corrosion current. The corrosion current for each time interval was calculated as the average of two consecutive Rc values. This average current was multiplied by the duration of the interval to determine the total charge for that period, and the cumulative charge for each rebar was obtained using Equation (1). Using Faraday's law, the apparent mass loss was subsequently calculated, as described in Equation (2).

where

C is in coulombs and

t is in seconds.

The mass loss calculated using Faraday's law is expressed as-

where Atomic Mass is 55.85g (for Fe), n is 2 (# of electrons), and

F is 96,500 C (Faraday’s constant).

Table 5 and

Table 6 highlight the estimated mass loss values obtained from the LPR and GP method for T1 and T2 samples with three rebars. The mass loss was determined based on measurements collected over a period of approximately 1600 days using both the LPR and GP methods.

The estimated mass loss values obtained from LPR readings for T1 and T2 concrete mixes, as presented in

Table 5, are influenced by the reservoir lengths (2.5 cm, 5 cm, and 10 cm), the type of SCMs used, and the three rebars tested (A, B, and C). The shorter reservoir lengths, such as 2.5 cm, show higher mass loss for both T1 and T2 mixes, likely due to the localized concentration of corrosive agents. For T1 specimens, the highest mass loss occurs at 2.5 cm (26X) with Rebar B (1.423 g), while T2 specimen also experiences its highest mass loss at this length (30X), particularly for Rebar A (1.023 g). The medium reservoir lengths (5 cm) exhibit varied results; T1 (28X) specimen shows much lower mass loss compared to other reservoir lengths, while T2 (31X and 32X) specimens demonstrate reduced and consistent mass loss values, highlighting improved protection. At longer reservoir lengths (10 cm), both T1 (27X) and T2 (29X) specimens display moderate and relatively lower mass loss values, suggesting that longer reservoirs dilute the aggressiveness of the corrosive agents. In terms of SCM influence, T1 specimens, incorporating fly ash and slag, shows greater variability in mass loss values, with better resistance noted in certain cases like 5 cm reservoir length (28X). The T2 specimens, containing fly ash and silica fume, generally exhibit superior corrosion resistance, with lower mass loss values across most scenarios, likely due to silica fume’s ability to enhance concrete density and reduce permeability. Therefore, T2 specimens outperform T1 specimens in mitigating mass loss values, though shorter reservoir lengths exacerbate localized corrosion in both mixes. The variability among individual rebars further emphasizes the impact of local environmental conditions on corrosion behavior.

Table 6 offers a comprehensive comparison of the mass loss values (in grams) obtained from GP readings for T1 and T2 concrete mixes, each containing three rebar specimens (A, B, and C), and subjected to varying reservoir lengths (2.5 cm, 5 cm, and 10 cm). These mass loss values serve as an indicator of corrosion-induced degradation at the rebar-concrete interface.

Table 4 provides insight into how both the length of exposure (reservoir length) and the type of SCMs used affect the extent of corrosion, as reflected by the mass loss values. The data clearly demonstrates that mass loss increases with longer reservoir lengths, indicating that extended exposure to chloride and moisture leads to more substantial corrosion in both T1 and T2 samples. For example, at a 10 cm reservoir length, T1 specimens exhibit mass losses ranging from 0.458 g to 0.535 g, significantly higher than the 0.260 g to 0.303 g range observed at the 2.5 cm length. Similarly, T2 specimens show increased mass loss at 10 cm (0.229 g to 0.394 g) compared to the shorter 2.5 cm length (0.148 g to 0.165 g). This trend, with longer reservoir lengths leading to greater corrosion activity, is consistent across all samples and supports the observation that prolonged exposure increases the penetration of corrosive agents into the concrete matrix, thus enhancing corrosion rates. When comparing the two mixes, T2 consistently shows lower mass loss values across all reservoir lengths, demonstrating superior corrosion resistance. For example, at the 10 cm reservoir length, T2 specimens mass losses range from 0.229 g to 0.394 g, while T1 shows higher mass losses between 0.458 g and 0.535 g. This superior performance of T2 is attributed to the inclusion of silica fume, a highly reactive pozzolan that improves the density and impermeability of the concrete matrix. Silica fume’s ability to reduce permeability prevents the deeper penetration of chlorides and moisture, effectively reducing corrosion at the rebar interface. In contrast, while the fly ash and slag in T1 samples enhance the durability of the concrete, they are less effective in minimizing corrosion compared to silica fume, which further highlights the significant impact of material selection on corrosion resistance in reinforced concrete.

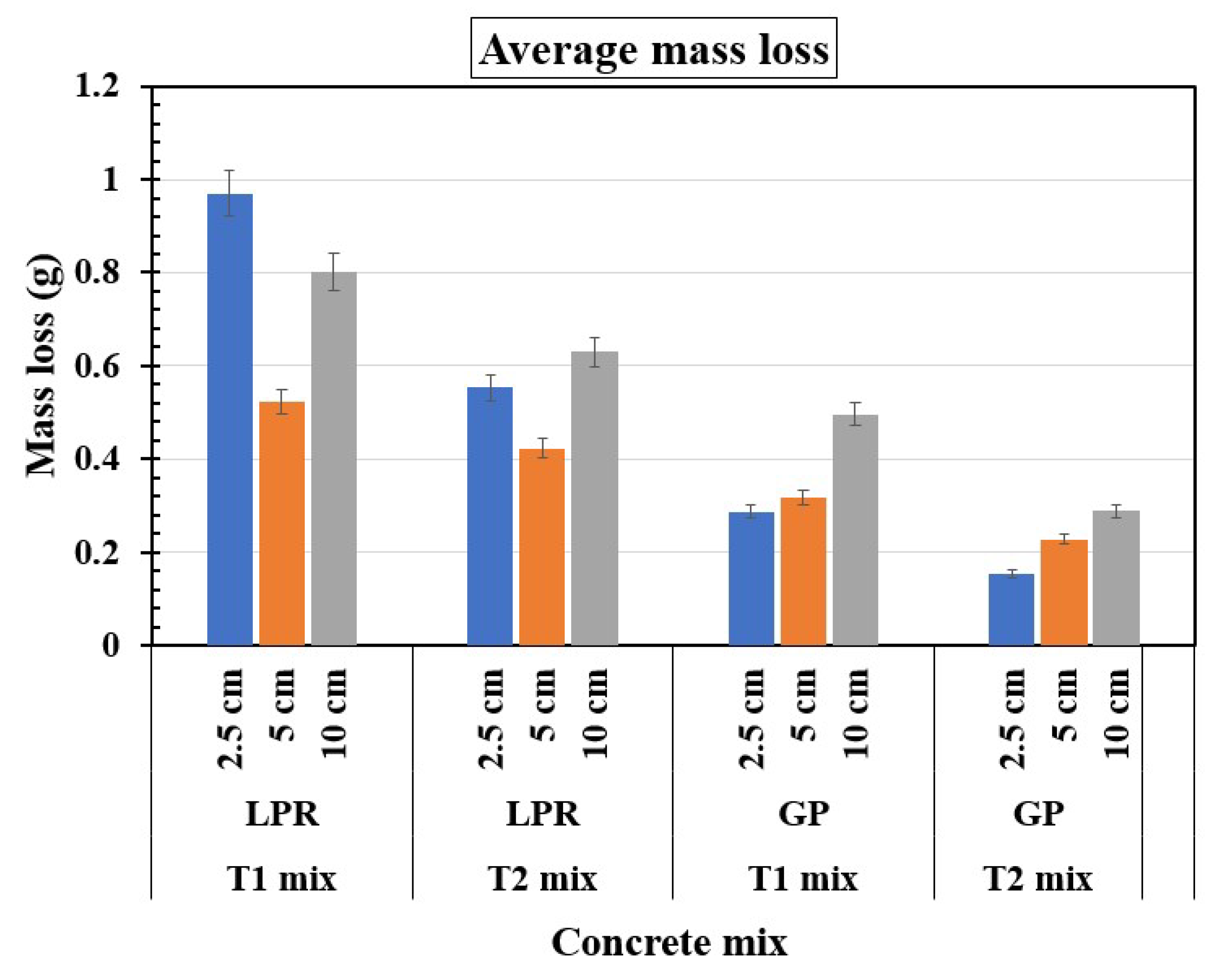

The mass loss trends in

Figure 11 for T1 and T2 concrete mixes obtained from LPR and GP measurements show distinct variations across reservoir lengths. In both methods, shorter reservoir lengths (2.5 cm) consistently exhibit the highest mass loss for both mixes, with T1 specimens showing greater values compared to T2 specimens, particularly under LPR measurements. At medium reservoir lengths (5 cm), the mass loss significantly decreases, with T2 specimens outperforming T1 specimens in both methods, highlighting the enhanced resistance provided by silica fume in T2 specimens. For longer reservoir lengths (10 cm), the mass loss further reduces for both mixes, with GP measurements indicating slightly lower values than LPR measurements, especially for T2 specimens, likely due to the reduced impact of localized corrosive agents. Therefore, T2 specimens exhibit better performance across all reservoir lengths and methods, while the GP measurements generally show more conservative mass loss values compared to LPR measurements, emphasizing their potential differences in sensitivity to corrosion.

Torres-Acosta's study on concrete beams and cylindrical specimens with chloride-contaminated mixes exposed to 75% RH and a 100 μA/cm² impressed current found mass loss ranging from 0.3–14.4 g (beams) and 0.7–5.1 g (cylinders) via forensic analysis, with similar Faradaic values (0.3–12.5 g for beams; 0.6–5.8 g for cylinders) [

34]. Corrosion-induced cracks were observed in all specimens, contrasting with the current study, where higher moisture levels prevented cracking despite some external rebar corrosion. Balasubramanian's research on reinforced concrete pipes prepared with either fly ash or Portland cement, under 95% RH and electromigration-induced corrosion, showed mass loss of 2.0–10.3 g (fly ash) and 0.6–3.2 g (Portland cement) by forensic analysis, with slightly higher Faradaic values [

31]. The fly ash specimens in vertical exposure showed 0.6–1.2 g mass loss (forensic) and 2.0–5.9 g (Faradaic), while horizontal exposure reduced these to 0.1–0.3 g and 1.9–2.0 g, respectively [

31]. No cracks were observed in Balasubramanian’s study, likely due to high moisture enabling corrosion products to diffuse into the concrete, reducing localized stresses [

17,

18,

19,

30].